Submitted:

31 October 2025

Posted:

03 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

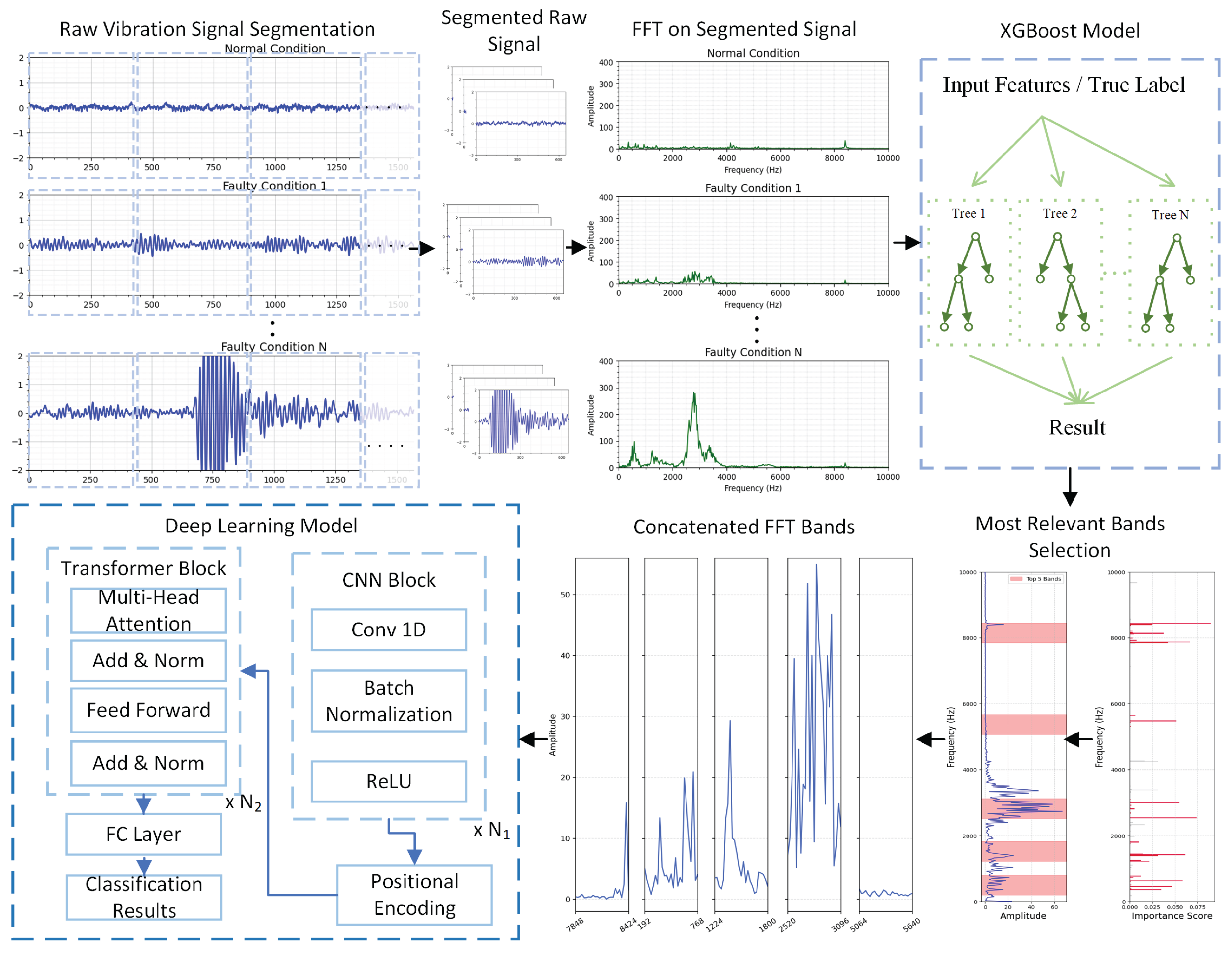

2. Methodology

2.1. Raw Signal Segmentation and Preprocessing

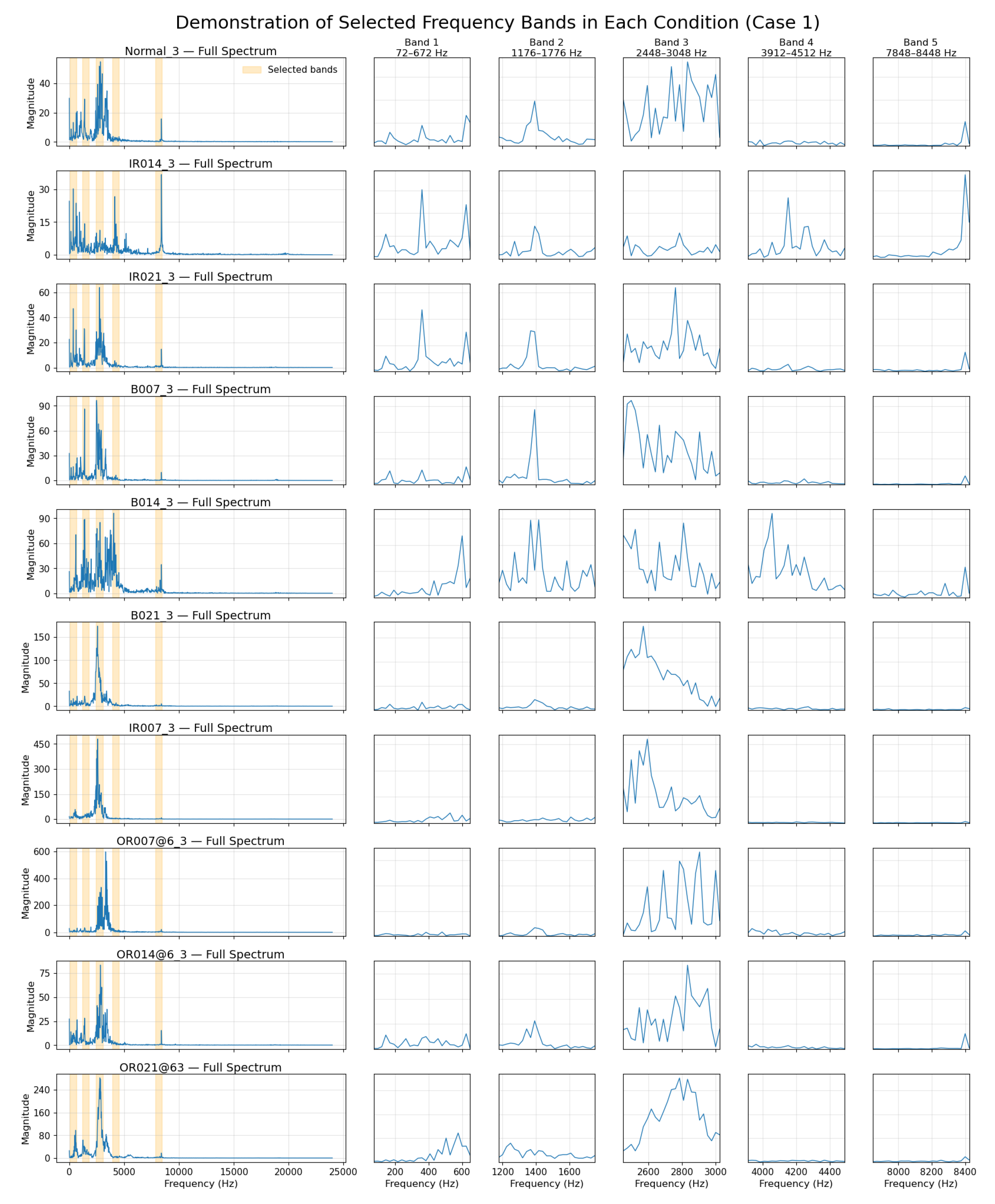

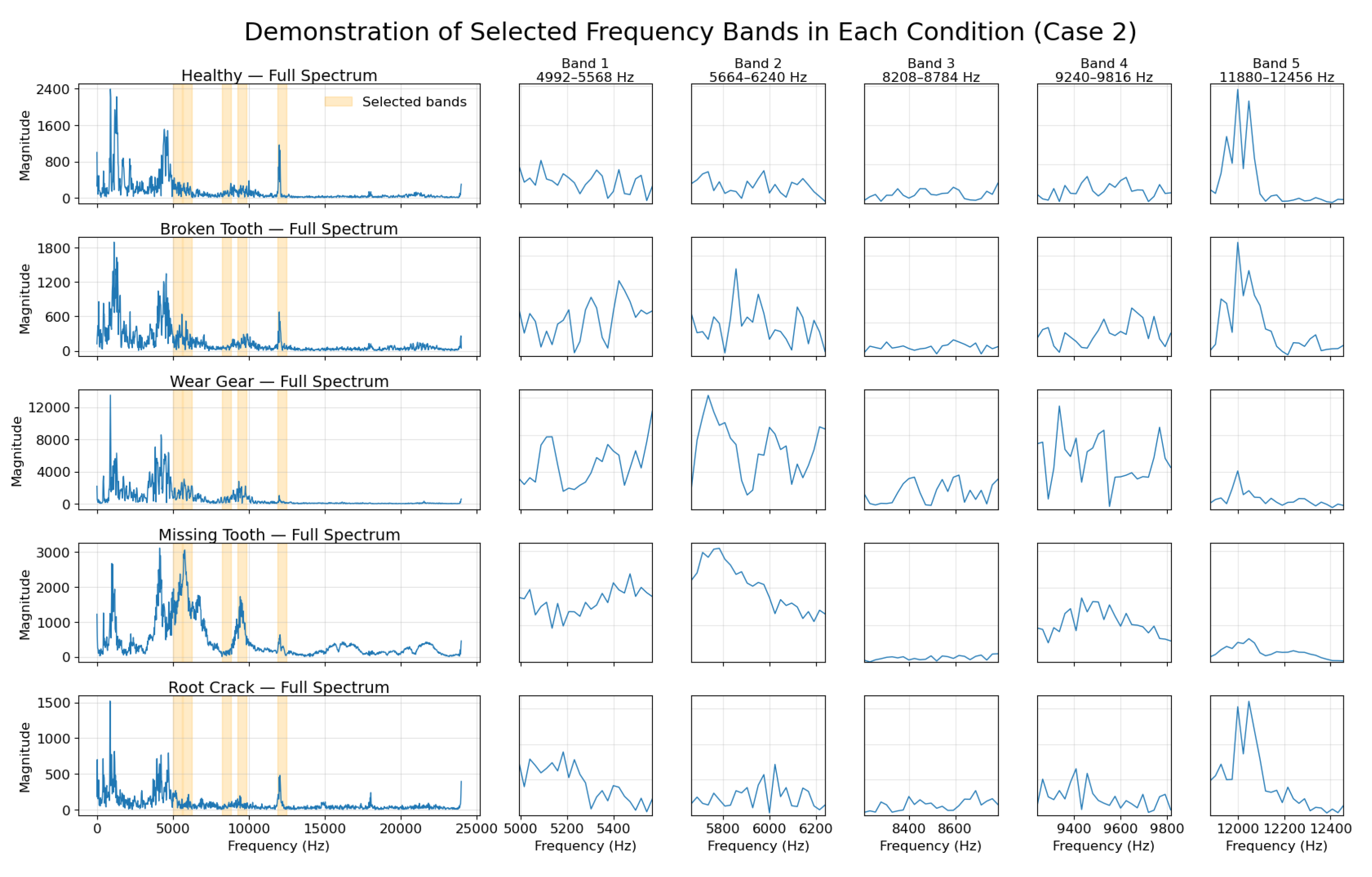

2.2. XGBoost-Assisted Frequency Band Selection

2.3. Deep Learning Architecture

3. Open-Access Dataset

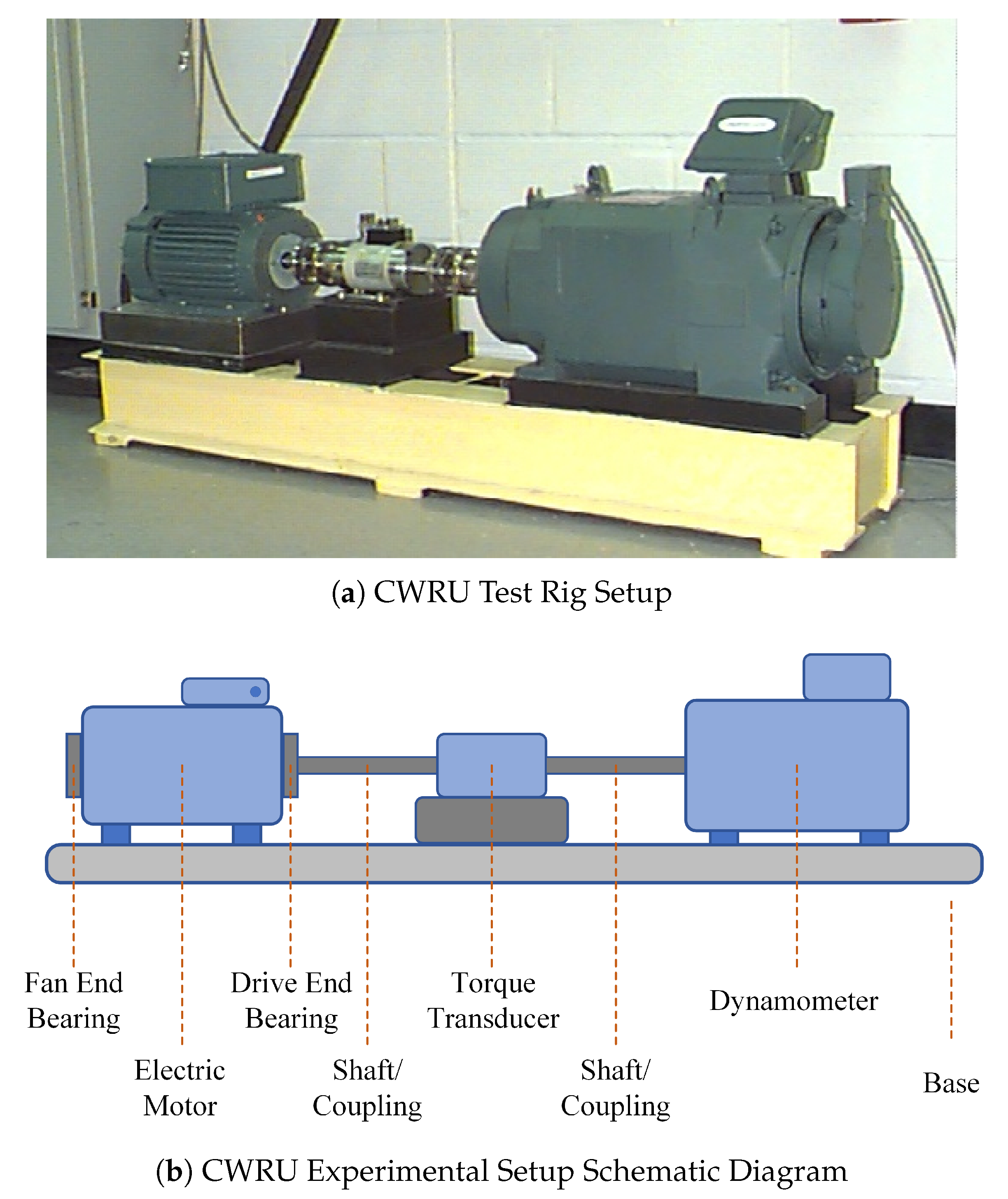

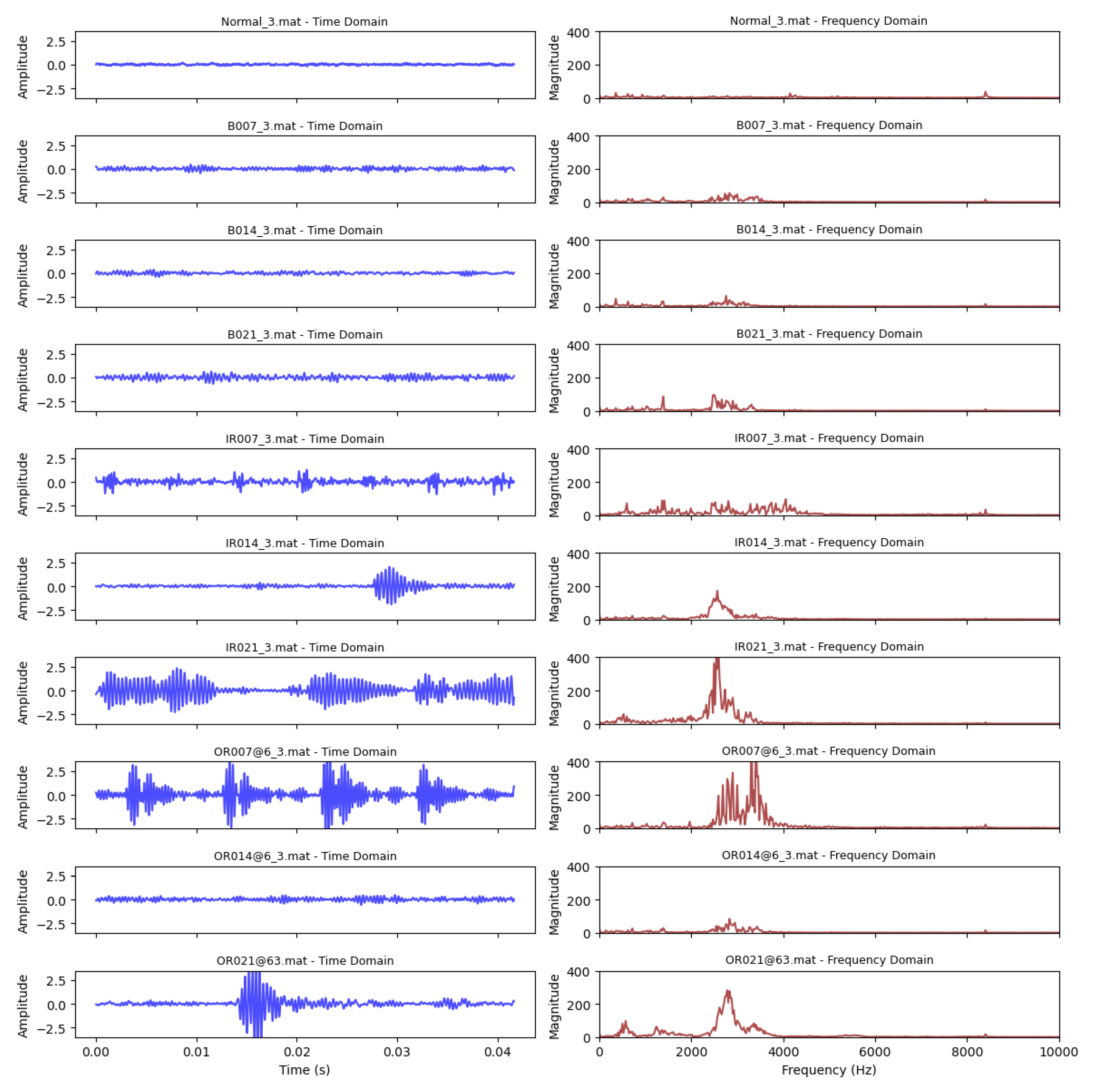

3.1. CWRU Bearing Dataset

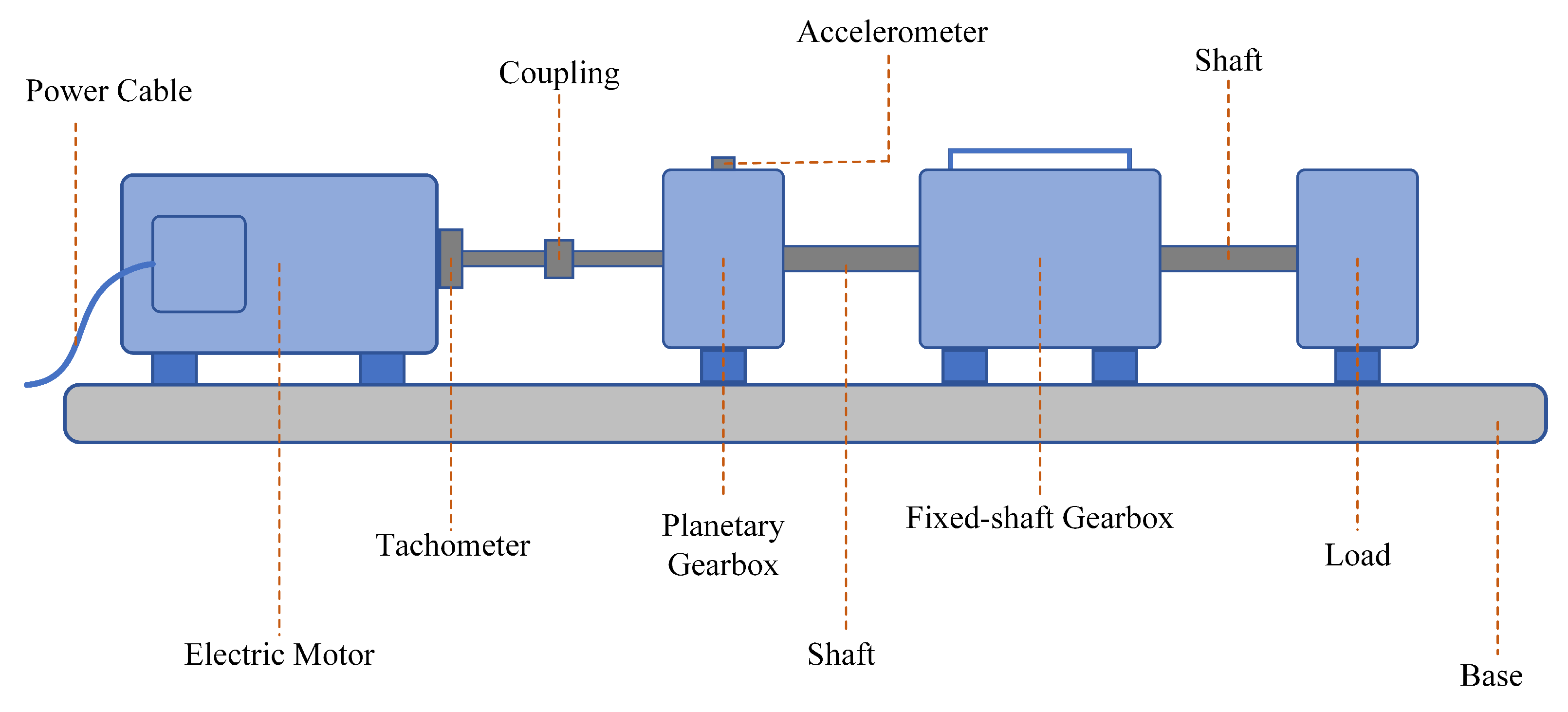

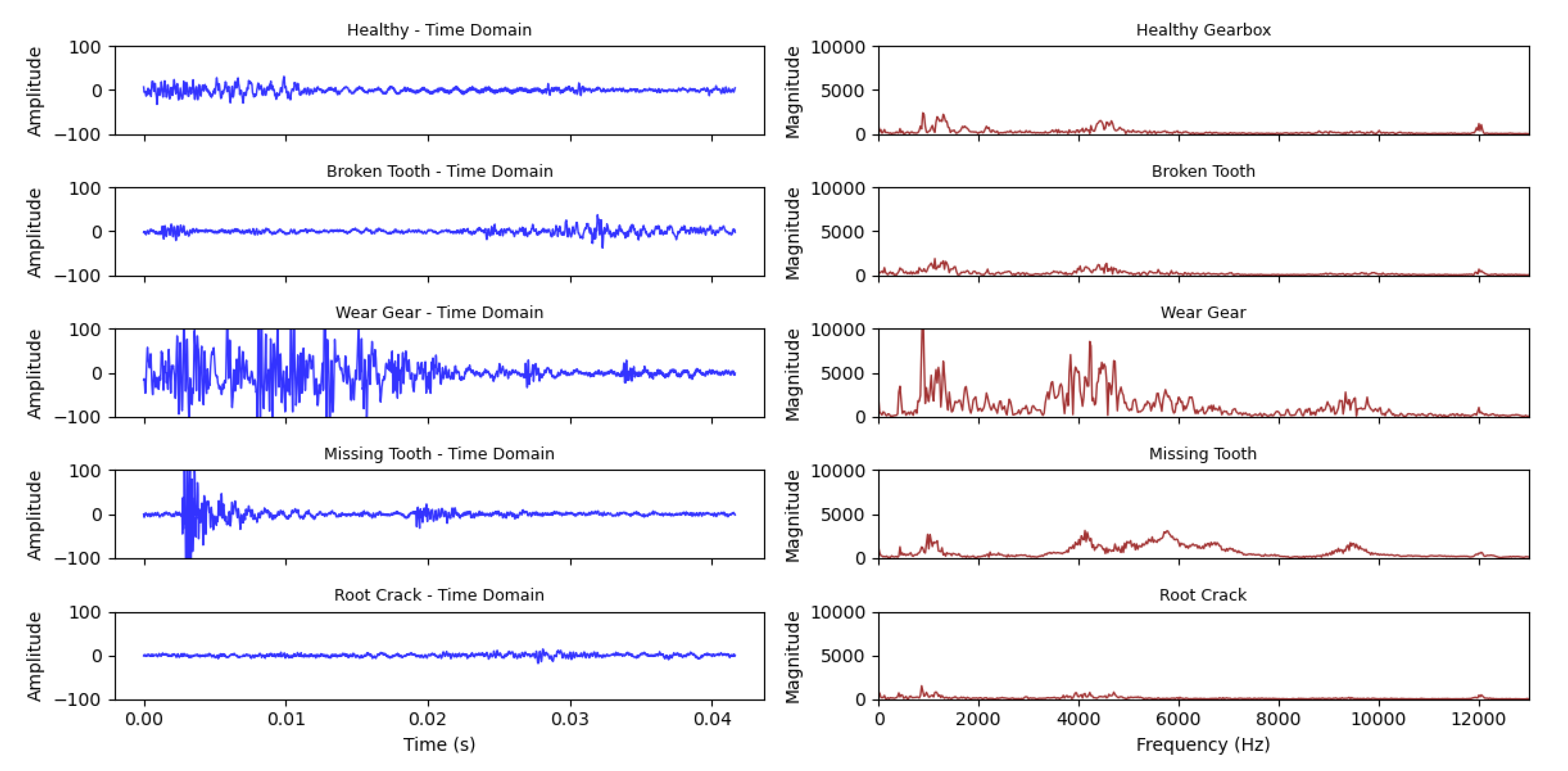

3.2. BJTU Planetary Gearbox Dataset

4. Results and Discussions

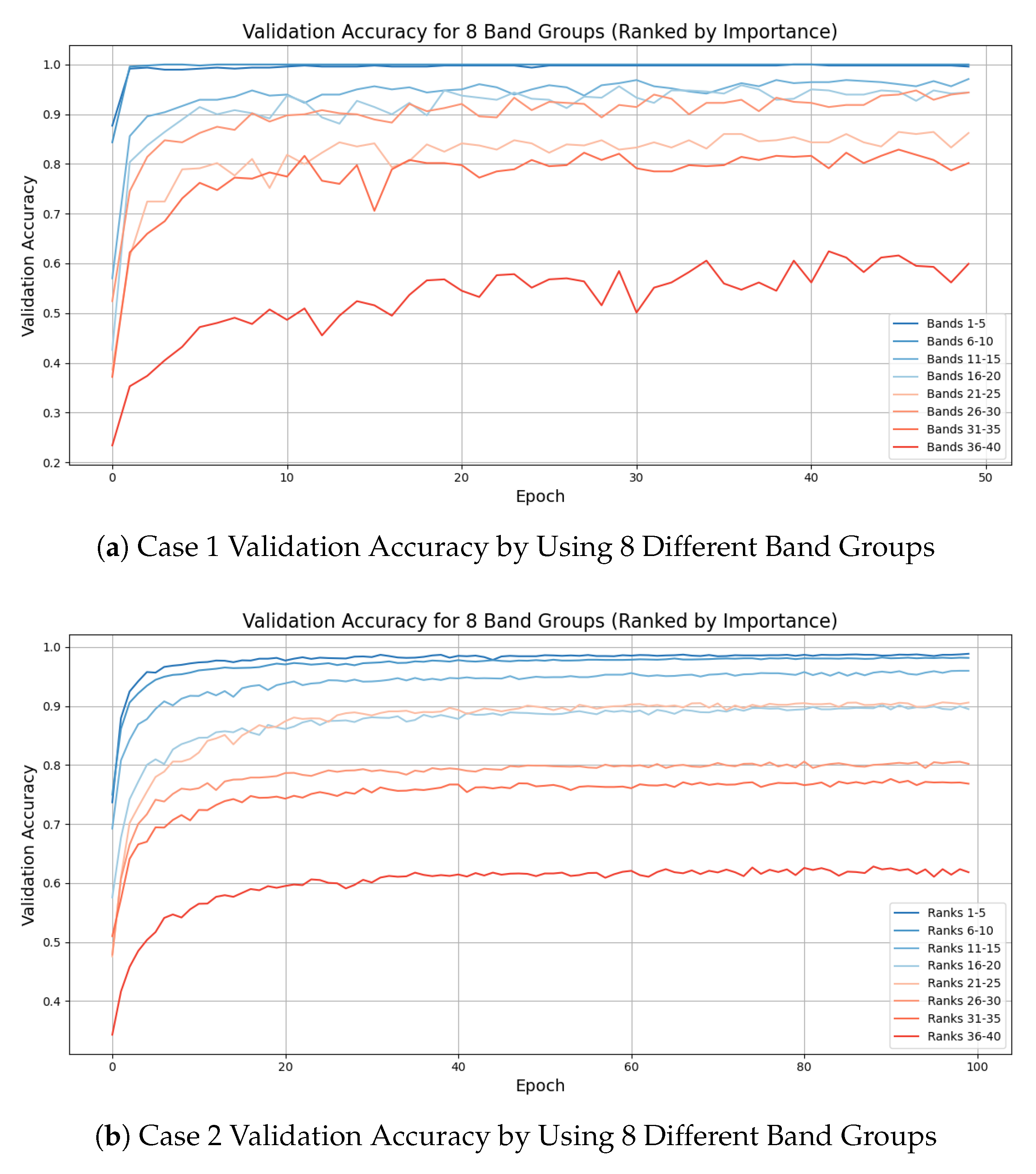

4.1. Training Results

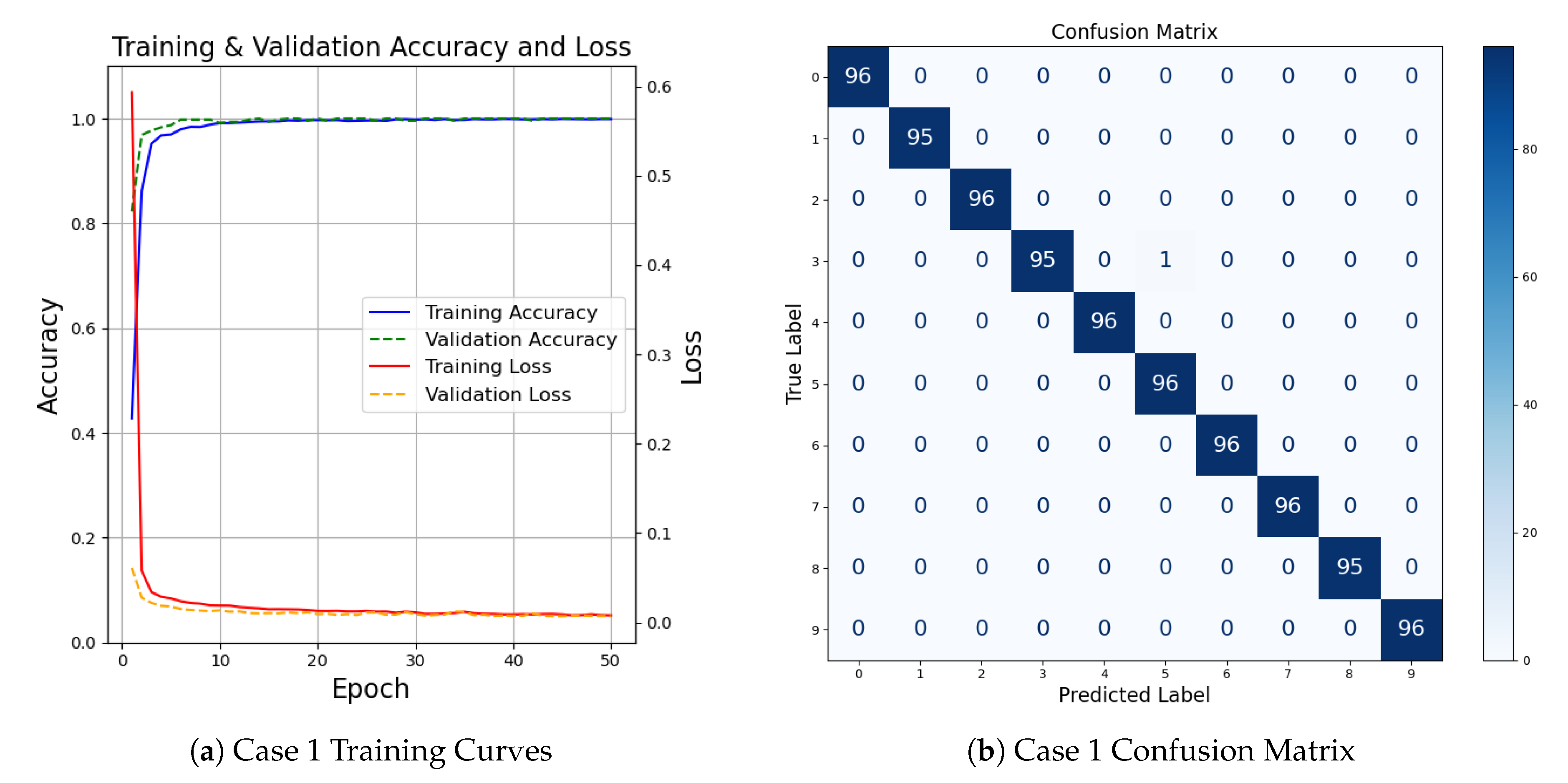

4.1.1. CWRU Bearing Dataset

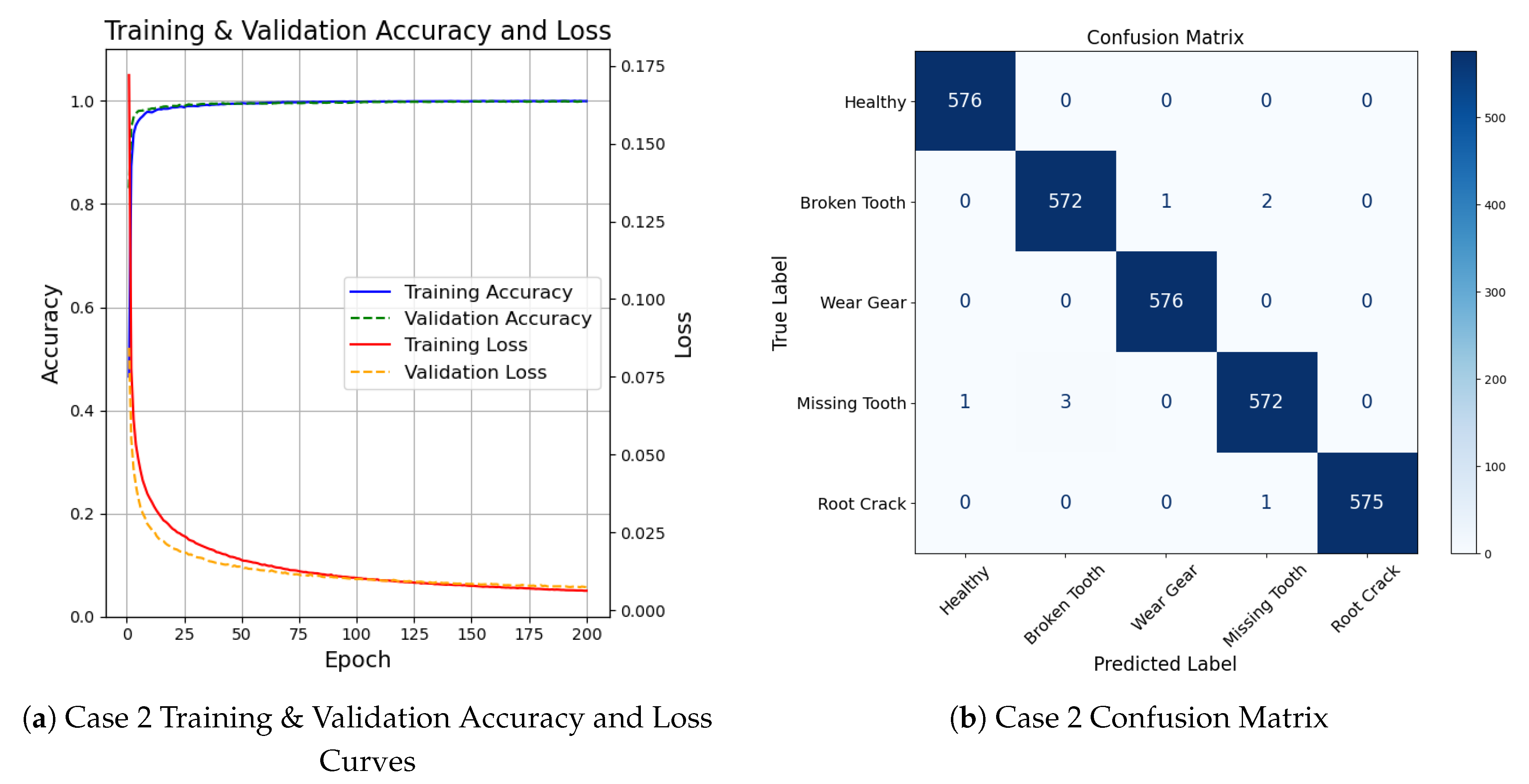

4.1.2. BJTU Wind Turbine Planetary Gearbox Dataset

4.2. Performance Analysis

5. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kong, K.; Dyer, K.; Payne, C.; Hamerton, I.; Weaver, P.M. Progress and Trends in Damage Detection Methods, Maintenance, and Data-driven Monitoring of Wind Turbine Blades – A Review. Renewable Energy Focus 2023, 44, 390 – 412. Cited by: 96; All Open Access, Hybrid Gold Open Access, . [CrossRef]

- Dibaj, A.; Gao, Z.; Nejad, A.R. Fault detection of offshore wind turbine drivetrains in different environmental conditions through optimal selection of vibration measurements. Renewable Energy 2023, 203, 161–176. [CrossRef]

- Badihi, H.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, B.; Pillay, P.; Rakheja, S. A Comprehensive Review on Signal-Based and Model-Based Condition Monitoring of Wind Turbines: Fault Diagnosis and Lifetime Prognosis. Proceedings of the IEEE 2022, 110, 754 – 806. Cited by: 158; All Open Access, Hybrid Gold Open Access, . [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Su, N.; Qin, B.; Sun, G.; Jing, X.; Hu, S.; Cai, Y.; Zhou, L. Fault Diagnosis for Rotating Machinery Based on Dimensionless Indices: Current Status, Development, Technologies, and Future Directions. Electronics 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Tuirán, R.; Águila, H.; Jou, E.; Escaler, X.; Mebarki, T. Fault Diagnosis in a 2 MW Wind Turbine Drive Train by Vibration Analysis: A Case Study. Machines 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Xu, H.; Zhang, D.; Qian, P. Overview of Condition Monitoring Technology for Variable-Speed Offshore Wind Turbines. Energies 2025, 18. [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Chen, Y.; Deng, X.; Lin, X.; Han, Y.; Zheng, J. Denoising method of machine tool vibration signal based on variational mode decomposition and Whale-Tabu optimization algorithm. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 1505. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Hai, Z.; Chen, X.; Chen, F.; Xiao, W.; Xiao, N.; Fu, W.; Liu, Q.; Tian, Z.; Li, G. A time-varying instantaneous frequency fault features extraction method of rolling bearing under variable speed. Journal of Sound and Vibration 2023, 560, 117785. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yan, X.; Feng, K.; Sheng, X.; Sun, B.; Liu, Z. Attention-based multiscale denoising residual convolutional neural networks for fault diagnosis of rotating machinery. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2022, 226, 108714. [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Gonzalez, M.; Diaz, V.G.; Lopez Perez, B.; Cristina Pelayo G-Bustelo, B.; Anzola, J.P. Bearing Fault Diagnosis With Envelope Analysis and Machine Learning Approaches Using CWRU Dataset. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 57796 – 57805. Cited by: 38; All Open Access, Gold Open Access, . [CrossRef]

- Blockeel, H.; Devos, L.; Frénay, B.; Nanfack, G.; Nijssen, S. Decision trees: from efficient prediction to responsible AI, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, I.; Dertimanis, V.; Mylonas, C.; Tatsis, K.; Chatzi, E.; Dervilis, N.; Worden, K.; Maguire, A. Fault Diagnosis of Wind Turbine Structures Using Decision Tree Learning Algorithms with Big Data. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Damage Assessment of Structures (DAMAS 2017), 06 2018, pp. 3053–3061. [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, P.; Brzychczy, E.; Zimroz, R. Decision Tree-Based Classification for Planetary Gearboxes’ Condition Monitoring with the Use of Vibration Data in Multidimensional Symptom Space. Sensors 2020, 20. [CrossRef]

- Shubita, R.R.; Alsadeh, A.S.; Khater, I.M. Fault Detection in Rotating Machinery Based on Sound Signal Using Edge Machine Learning. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 6665 – 6672. Cited by: 26; All Open Access, Gold Open Access, . [CrossRef]

- Alhams, A.; Abdelhadi, A.; Badri, Y.; Sassi, S.; Renno, J. Enhanced Bearing Fault Diagnosis Through Trees Ensemble Method and Feature Importance Analysis. Journal of Vibration Engineering & Technologies 2024, 12, 109–125. [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, K.; Holte, R. Decision Tree Instability and Active Learning. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning: ECML 2007; Kok, J.N.; Koronacki, J.; Mantaras, R.L.d.; Matwin, S.; Mladenič, D.; Skowron, A., Eds., Berlin, Heidelberg, 2007; pp. 128–139.

- Choudakkanavar, G.; Mangai, J.A.; Bansal, M. MFCC based ensemble learning method for multiple fault diagnosis of roller bearing. International Journal of Information Technology 2022, 14, 2741–2751. [CrossRef]

- Hemalatha, S.; Kavitha, T.; Anand, P. Effectiveness of Classification Techniques for Fault Bearing Prediction. In Proceedings of the 2022 6th International Conference on Electronics, Communication and Aerospace Technology, 2022, pp. 8–13. [CrossRef]

- Souza, V.F.; Cicalese, F.; Laber, E.S.; Molinaro, M. Decision trees with short explainable rules. Theoretical Computer Science 2025, 1047, 115344. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Nguyen, T.H.; Do, D.T.B.; Pham, T.H.; Liang, J.W.; Nguyen, P.D. Efficient and Explainable Bearing Condition Monitoring with Decision Tree-Based Feature Learning. Machines 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Rodríguez-Andina, J.J.; Luo, H. High-Performance Fault Classification Based on Feature Importance Ranking-XgBoost Approach with Feature Selection of Redundant Sensor Data. Current Chinese Science 2022, 2, 243–251. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Fan, Y.; Tan, J.; Li, Z.; Yang, P.; Wang, H.; Duan, W. Tool wear prediction based on XGBoost feature selection combined with PSO-BP network. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 3096. [CrossRef]

- Tama, B.A.; Vania, M.; Lee, S.; Lim, S. Recent advances in the application of deep learning for fault diagnosis of rotating machinery using vibration signals. Artificial Intelligence Review 2023, 56, 4667–4709. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Rao, M.; Qin, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ji, Y. Explicit speed-integrated LSTM network for non-stationary gearbox vibration representation and fault detection under varying speed conditions. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2025, 254, 110596. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Dong, E.; Cheng, Z.; Liu, Z.; Jia, X. Transformer-based intelligent fault diagnosis methods of mechanical equipment: A survey. Open Physics 2024, 22, 20240015. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Lei, Y.; Qi, G.; Chai, Y.; Mazur, N.; An, Y.; Huang, X. A review of the application of deep learning in intelligent fault diagnosis of rotating machinery. Measurement: Journal of the International Measurement Confederation 2023, 206. Cited by: 358, . [CrossRef]

- Alam, T.E.; Ahsan, M.M.; Raman, S. Multimodal bearing fault classification under variable conditions: A 1D CNN with transfer learning. Machine Learning with Applications 2025, 21, 100682. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wei, H.L.; Ding, J. An effective zero-shot learning approach for intelligent fault detection using 1D CNN. Applied Intelligence 2023, 53, 16041–16058. [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Yao, L.; Duan, D.; Yang, J.; Wu, W.; Zhao, C.; Zheng, C.; Gao, X. Intelligent condition monitoring with CNN and signal enhancement for undersampled signals. ISA Transactions 2024, 149, 124–136. [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2017, Vol. 2017-December, p. 5999 – 6009. Cited by: 88052.

- Kim, S.; Seo, Y.H.; Park, J. Transformer-based novel framework for remaining useful life prediction of lubricant in operational rolling bearings. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2024, 251, 110377. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Jia, M.; Miao, Q.; Cao, Y. A novel time–frequency Transformer based on self–attention mechanism and its application in fault diagnosis of rolling bearings. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2022, 168, 108616. [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zhang, F.; Li, Z.; Wang, Q.; Li, C.; Lai, P.; Li, T.; Teng, F.; Jin, Z. MT-ConvFormer: A Multitask Bearing Fault Diagnosis Method Using a Combination of CNN and Transformer. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2024, PP, 1–1. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Liang, L.; Zhu, J.; Zou, W.; Mao, L. Rotating Machinery Fault Diagnosis Under Multiple Working Conditions via a Time-Series Transformer Enhanced by Convolutional Neural Network. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2023, 72, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.F.; Alam, M.S.B.; Hassan, M.; Rozbu, M.R.; Ishtiak, T.; Rafa, N.; Mofijur, M.; Ali, A.B.M.S.; Gandomi, A.H. Deep learning modelling techniques: current progress, applications, advantages, and challenges. Artificial Intelligence Review 2023, 56, 13521–13617. [CrossRef]

- Saeed, A.; Khan, M.A.; Akram, U.; Obidallah, W.J.; Jawed, S.; Ahmad, A. Deep learning based approaches for intelligent industrial machinery health management and fault diagnosis in resource-constrained environments. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 1114. [CrossRef]

- Brigham, E.O.; Morrow, R.E. The fast Fourier transform. IEEE Spectrum 1967, 4, 63–70. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, New York, NY, USA, 2016; KDD ’16, p. 785–794. [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-Based Learning Applied to Document Recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.u.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All you Need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Guyon, I.; Luxburg, U.V.; Bengio, S.; Wallach, H.; Fergus, R.; Vishwanathan, S.; Garnett, R., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2017, Vol. 30.

- Case Western Reserve University Bearing Data Center. Bearing Data Center Website. https://engineering.case.edu/bearingdatacenter. Accessed: 2025-06-29.

- Liu, D.; Cui, L.; Cheng, W. A review on deep learning in planetary gearbox health state recognition: Methods, applications, and dataset publication. Measurement Science and Technology 2023, 35. [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z.; Ma, J.; Li, T. Diagnosisformer: An efficient rolling bearing fault diagnosis method based on improved Transformer. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2023, 124, 106507. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Jiang, Y.; Cheng, C.; Wang, S. An improved fault diagnosis method for rolling bearings based on wavelet packet decomposition and network parameter optimization. Measurement Science and Technology 2023, 35, 025004. [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Peng, Y.; Lu, H.; Chang, X.; Chen, G. A novel fault diagnosis method of rotating machinery via VMD, CWT and improved CNN. Measurement 2022, 200, 111635. [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Li, X.; Yu, J.; Wang, T.; Yun, Q. A bearing fault diagnosis model with enhanced feature extraction based on the Kolmogorov–Arnold representation Theorem and an attention mechanism. Applied Acoustics 2025, 240, 110903. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, B.; Gao, D. Bearing fault diagnosis base on multi-scale CNN and LSTM model. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing 2021, 32, 971–987. [CrossRef]

| Index | File Name | Fault Type | Fault Size (mil) | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Normal_3.mat | Normal | – | – |

| 1 | B007_3.mat | Ball Fault | 7 | – |

| 2 | B014_3.mat | Ball Fault | 14 | – |

| 3 | B021_3.mat | Ball Fault | 21 | – |

| 4 | IR007_3.mat | Inner Race | 7 | – |

| 5 | IR014_3.mat | Inner Race | 14 | – |

| 6 | IR021_3.mat | Inner Race | 21 | – |

| 7 | OR007@6_3.mat | Outer Race | 7 | 6:00 |

| 8 | OR014@6_3.mat | Outer Race | 14 | 6:00 |

| 9 | OR021@6_3.mat | Outer Race | 21 | 6:00 |

| Index | Condition | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Healthy | No damage on the sun gear |

| 1 | Broken Tooth | Partial removal (about one-third) of a sun gear tooth |

| 2 | Wear Gear | Gear tooth surface worn |

| 3 | Missing Tooth | Complete tooth removal |

| 4 | Root Crack | Crack introduced at the root of a sun gear tooth |

| Band Rank | Frequency Range | Importance Scores |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7848–8448 Hz | 415.6893 |

| 2 | 2448–3048 Hz | 373.6769 |

| 3 | 1176–1776 Hz | 342.1831 |

| 4 | 72–672 Hz | 195.7419 |

| 5 | 3912–4512 Hz | 95.5129 |

| 6 | 3192–3792 Hz | 56.8888 |

| 7 | 1848–2448 Hz | 34.1304 |

| 8 | 5832–6432 Hz | 28.5478 |

| 9 | 9192–9792 Hz | 18.6156 |

| 10 | 7248–7848 Hz | 18.4222 |

| ... | ... | ... |

| Band Rank | Frequency Range | Importance Scores |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8184–8784 Hz | 624.7955 |

| 2 | 4992–5592 Hz | 506.2124 |

| 3 | 9240–9840 Hz | 236.5562 |

| 4 | 11808–12408 Hz | 181.2200 |

| 5 | 5664–6264 Hz | 129.3388 |

| 6 | 1608–2208 Hz | 96.6329 |

| 7 | 4392–4992 Hz | 57.2291 |

| 8 | 0–600 Hz | 43.8308 |

| 9 | 6288–6888 Hz | 38.6528 |

| 10 | 816–1416 Hz | 38.0441 |

| ... | ... | ... |

| Study / Reference | Feature Type | Classifier | Accuracy (%) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hou et al. [43] | Frequency Domain | Improved Transformer | 99.85 | Transformer with multi-feature parallel fusion. |

| Zhao et al. [44] | WPD & Energy Features | WPD-CSSOA-DBN | 98.24 | Signal processing technique with energy feature selection and deep belief network. |

| Gu et al. [45] | Image | CNN | 99.90 | Signal pre-processing with image-based CNN classification. |

| Jin et al. [46] | Time Domain | KACSEN | 99.27 | Enhanced feature extraction with SE attention mechanism. |

| Chen et al. [47] | Time Domain | MCNN-LSTM | 99.31 | End-to-end fault classification model. |

| Proposed Method | Selected Frequency Bands | CNN + Transformer | 99.90 | High accuracy with frequency-band-based feature selection and hybrid classification. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).