1. Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) comprises a group of neurodevelopmental conditions characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and interaction, accompanied by restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, and activities, with considerable heterogeneity in clinical presentation and co-occurring conditions [

1]. Surveillance data indicate that ASD affects approximately 1–2% of children worldwide. In the United States, the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network estimated a prevalence of 23.0 per 1,000 among 8-year-olds in 2018 [

2]. Although ASD is highly heritable, increasing attention has been directed toward potentially modifiable prenatal factors to elucidate environmental contributions to its etiology.

Maternal smoking during pregnancy is a well-established risk factor for adverse perinatal outcomes, including fetal growth restriction, low birth weight, and preterm birth, with clear dose–response relationships reported across cohorts [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Biologically, tobacco smoke constituents, such as nicotine, carbon monoxide, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, can cross the placenta, disrupt trophoblast function, and alter placental epigenetic regulation [

7]. Nicotine, in particular, crosses the placental barrier and can reach fetal concentrations equal to or exceeding maternal levels. Experimental evidence implicates nicotinic acetylcholine receptor–mediated mechanisms that interfere with neurogenesis, neurotransmitter signaling, and synaptogenesis during critical periods of brain development [

8].

Epidemiological findings regarding maternal smoking and ASD risk, however, remain inconsistent. A 2015 meta-analysis of 15 observational studies reported a pooled odds ratio (OR) of 1.02 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.93–1.10], suggesting no overall association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and offspring ASD [

9]. In contrast, a 2017 meta-analysis examining population-level smoking metrics identified increased odds in European (and one Asian) populations, implying possible effect modification by geographic or exposure context [

10]. More recent investigations applying causal inference frameworks and negative-control analyses have highlighted the potential influence of residual familial and genetic confounding, with most findings not supporting a strong causal relationship [

11,

12].

Nonetheless, emerging large-scale cohort studies have refined exposure classification and dose-response modeling. For example, a multi-site U.S. cohort reported that heavy maternal smoking (≥20 cigarettes/day) was associated with increased ASD risk, whereas lighter smoking showed weaker and statistically imprecise associations in sibling-comparison analyses [

13]. Similarly, biomarker-based studies using maternal cotinine measurements have enhanced exposure accuracy; although these studies have not demonstrated robust associations with ASD diagnoses, potential links with autism-related behavioral traits remain under discussion [

14]. Variation across studies may stem from differences in exposure assessment (self-report vs. biomarkers; active vs. environmental tobacco smoke), timing and intensity of exposure, concurrent environmental risk factors (e.g., air pollution), and incomplete control for socioeconomic or psychiatric confounding.

Given these discrepancies and the availability of new evidence since prior syntheses, an updated and comprehensive evaluation is warranted. The present systematic review and meta-analysis aims to integrate the most recent epidemiological and biomarker-based studies to clarify the relationship between maternal smoking during pregnancy and ASD risk, while addressing potential sources of heterogeneity and bias.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) guidelines [

15]. The protocol was prospectively registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; registration number: CRD420251161343).

Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was performed to identify relevant studies published from database inception until September 2025. The databases searched included PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, Scopus, PsycINFO, and Google Scholar. The search strategy combined controlled vocabulary (e.g., Autistic Disorder, Autism Spectrum Disorder, Tobacco Smoke Pollution, Smoking, Pregnancy, Prenatal Exposure Delayed Effects) with free-text terms (e.g., autism OR ASD OR tobacco OR smoking OR prenatal OR ‘maternal smoking’ OR ‘fetal exposure’) to ensure comprehensive coverage. No restrictions were applied regarding language, geographical region, or publication status. Reference lists of included articles and relevant reviews were screened for additional studies, and grey literature, including dissertations and preprints, was considered to reduce potential publication bias.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were eligible if they investigated maternal active smoking during pregnancy, defined via self-reported questionnaires, biomarkers such as cotinine, medical records, or registry data, and if they reported ASD diagnosis in offspring based on clinical evaluation, standardized diagnostic instruments, or administrative data using ICD or DSM codes. Cohort, case–control, cross-sectional, and population-based registry studies were included. Studies were excluded if they did not provide sufficient data to extract or calculate an effect estimate, did not report ASD as an outcome, lacked a defined exposure period, or were non-original publications such as reviews, commentaries, or case reports.

PRISMA Process

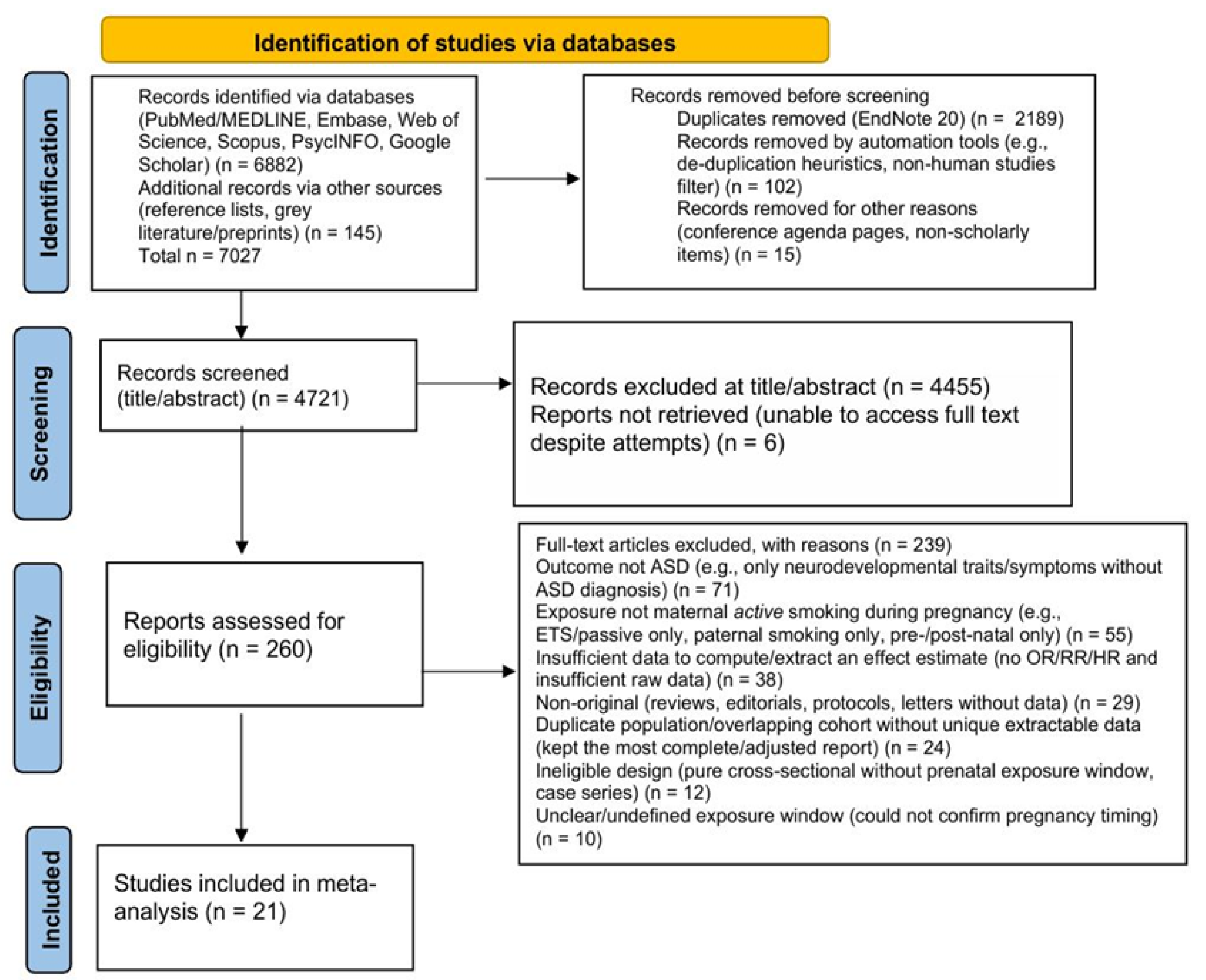

The study selection followed a two-step screening process. All retrieved records were imported into EndNote 20 for duplicate removal. Titles and abstracts were screened independently by two reviewers, and potentially relevant articles underwent full-text evaluation against the eligibility criteria. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer. The initial search identified 7,027 records, including 6,882 from electronic databases and 145 from additional sources. After removing 2,189 duplicates, 102 records through automated filters, and 15 records for other reasons, such as non-scholarly material, 4,721 records remained for title and abstract screening, of which 4,455 were excluded as clearly irrelevant. A total of 266 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility; six could not be obtained despite repeated attempts, leaving 260 articles for detailed review. Of these, 239 were excluded for reasons including: not reporting ASD as an outcome (n = 71), not assessing maternal active smoking during pregnancy (n = 55), insufficient data to calculate effect estimates (n = 38), non-original publications (n = 29), overlapping populations (n = 24), ineligible study designs (n = 12), and unclear timing of exposure (n = 10). Ultimately, 21 studies met all inclusion criteria and were included in the qualitative and quantitative analyses (

Figure 1).

Study Selection Flowchart

Quality Assessment

The methodological quality and risk of bias in the included studies were independently assessed by two reviewers utilizing the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) [

16]. This instrument evaluates three domains: participant selection, comparability of exposure groups, and the ascertainment of exposure and outcomes. Studies receiving scores between seven and nine stars were classified as having a low risk of bias, those with four to six stars as having a moderate risk, and those with three stars or fewer as having a high risk. Any discrepancies were resolved through consensus. Sensitivity analyses were conducted by excluding studies identified as having a high risk of bias.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted using a random-effects meta-analysis model based on the DerSimonian and Laird method to account for between-study heterogeneity. The primary summary measure was the relative risk (RR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI), used to estimate the association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and ASD in offspring. Adjusted estimates were prioritized for inclusion in the meta-analysis; when unavailable, unadjusted estimates were extracted and used. When effect sizes were reported as odds ratios (ORs) or hazard ratios (HRs), they were treated as approximations of RR due to the rarity of ASD.

Between-study heterogeneity was quantified using the Q statistic, the between-study variance (τ²), and the I² statistic, with I² values of 25%, 50%, and 75% interpreted as low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively.

Subgroup analyses were conducted to examine potential effect modification by: (i) adjustment status (adjusted vs. unadjusted estimates),; (ii) geographic region (North America, Europe); (iii) study design (cohort vs. case–control), and (iv) method of ASD ascertainment (registry/medical record-based vs. clinical/survey-based). Between-subgroup heterogeneity was assessed using the Q between statistic and associated p-values.

Sensitivity analyses were performed by: (a) excluding studies that reported only crude (unadjusted) estimates, (b) restricting to studies that used a binary "any vs. none" definition of smoking exposure, and (c) conducting leave-one-out analyses to assess the influence of individual studies on the overall pooled estimate. Additional sensitivity analyses examined the effect of excluding potential outliers and re-estimating results using alternative meta-analytic models to assess robustness.

Publication bias was assessed both visually and statistically. Funnel plots were examined for asymmetry, and Egger’s regression test was applied to detect small-study effects. A p-value < 0.10 in Egger’s test was considered indicative of potential publication bias. Where asymmetry was detected, trim-and-fill analyses were considered to estimate the potential impact of missing studies on the pooled effect size.

All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.3.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) with the metafor and meta packages for meta-analytic computations and graphics. A two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant unless otherwise specified.

3. Results

3.1. Primary Meta-Analysis

A total of 21 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the quantitative synthesis, representing a combined sample of several million mother–child pairs [

11,

13,

14,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. Characteristics of the included studies are summarized in

Table S1 (Supplementary File).

Most studies were large, population-based cohort or case–control investigations conducted in North America, Europe, and Asia. Exposure to maternal active smoking during pregnancy was primarily assessed through maternal self-report obtained from medical or administrative records, with a smaller number of studies incorporating biomarker validation (e.g., serum cotinine levels). ASD outcomes were typically identified through national or regional health registries, educational databases, or clinical diagnoses based on DSM or ICD criteria.

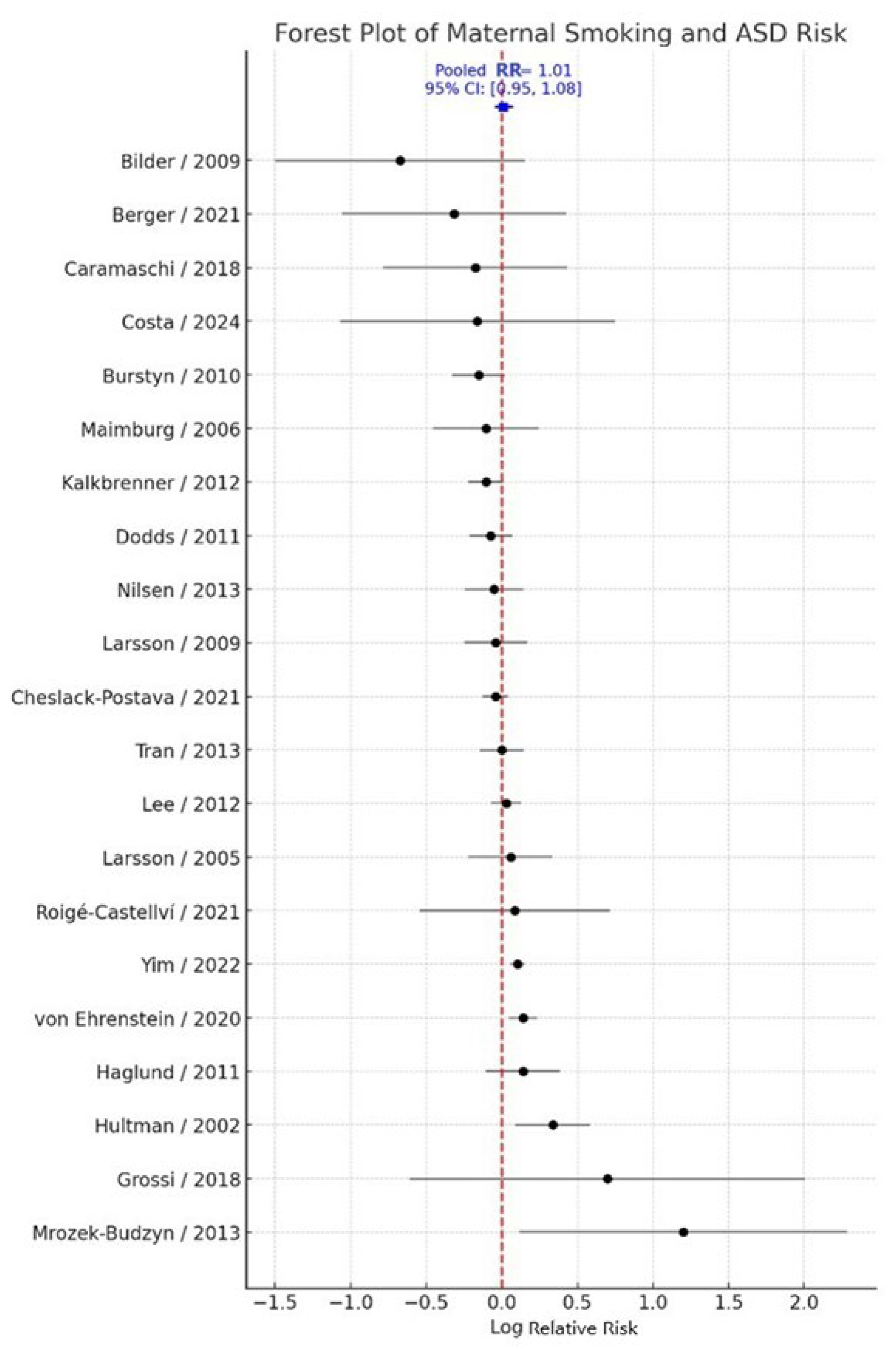

Adjusted effect estimates were prioritized for pooling, whereas crude estimates were used only when adjusted data were unavailable. The random-effects meta-analysis yielded a pooled relative risk (RR) of 1.01 (95% CI: 0.95–1.08; k = 21), indicating no statistically significant association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and ASD risk in offspring. Between-study heterogeneity was moderate (Q = 45.66, τ² = 0.0077, I² = 56.2%) (

Figure 2). Overall, these results suggest that maternal active smoking during pregnancy is not significantly associated with ASD when considering evidence across diverse populations, study designs, and exposure assessment methods.

3.2. Adjusted vs. Unadjusted Estimates

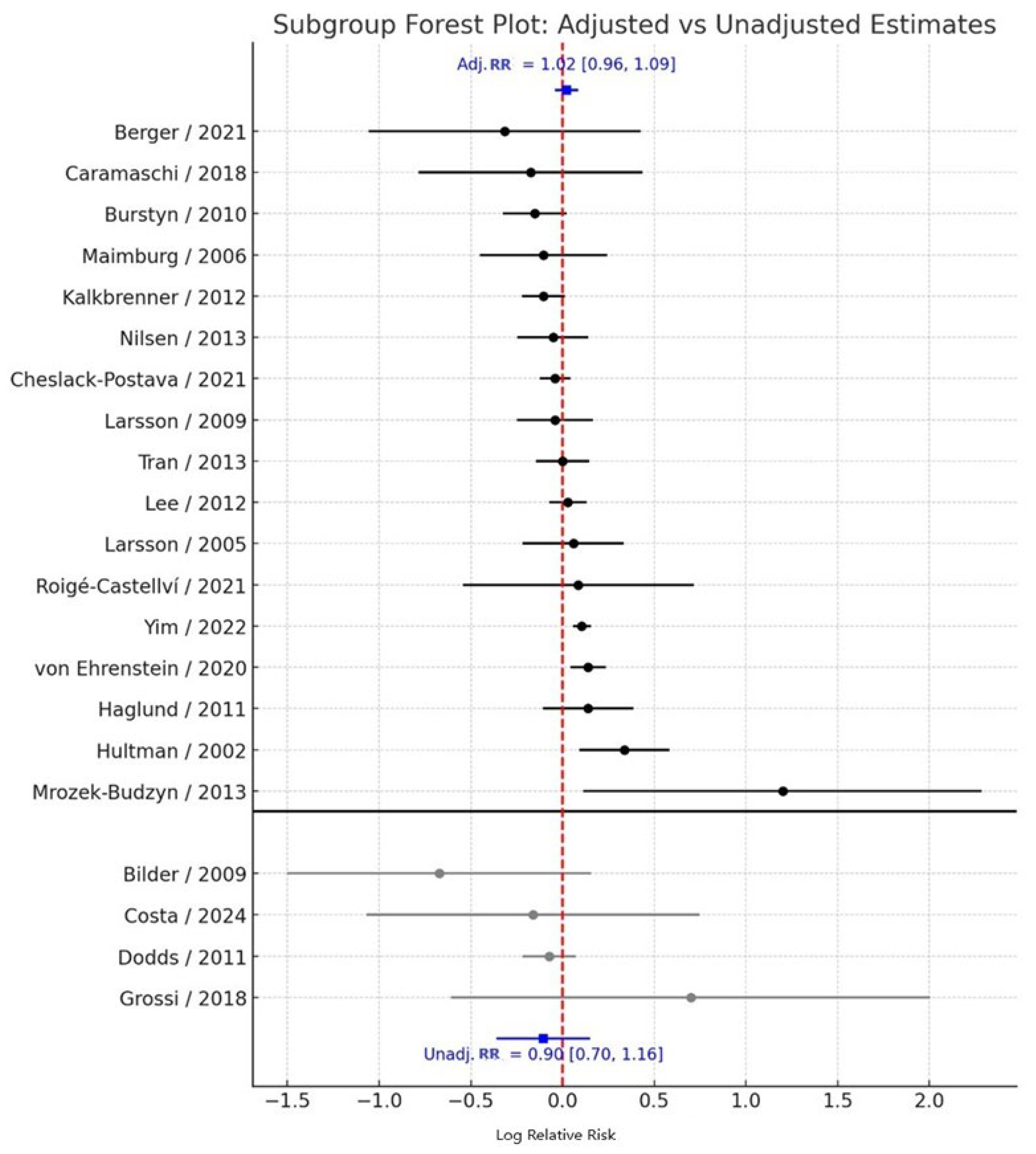

When stratified by adjustment status, the pooled effect derived from adjusted estimates (k = 17) was 1.02 (95% CI: 0.96–1.09), indicating no significant association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and ASD risk, with moderate heterogeneity (I² = 52.4%). In contrast, the pooled effect from unadjusted estimates (k = 4) was 0.90 (95% CI: 0.70–1.16), also non-significant, with low heterogeneity (I² = 28.7%) (

Figure 3).

The between-subgroup heterogeneity test showed no statistically significant difference in effect estimates between adjusted and unadjusted studies (Q<sub>between</sub> = 3.01, df = 1, p = 0.083). Although the slightly attenuated risk observed in unadjusted analyses may reflect residual confounding from sociodemographic or perinatal factors, this difference does not materially influence the overall null association between maternal smoking and ASD risk.

3.3. Subgroup Analysis by Geographic Region

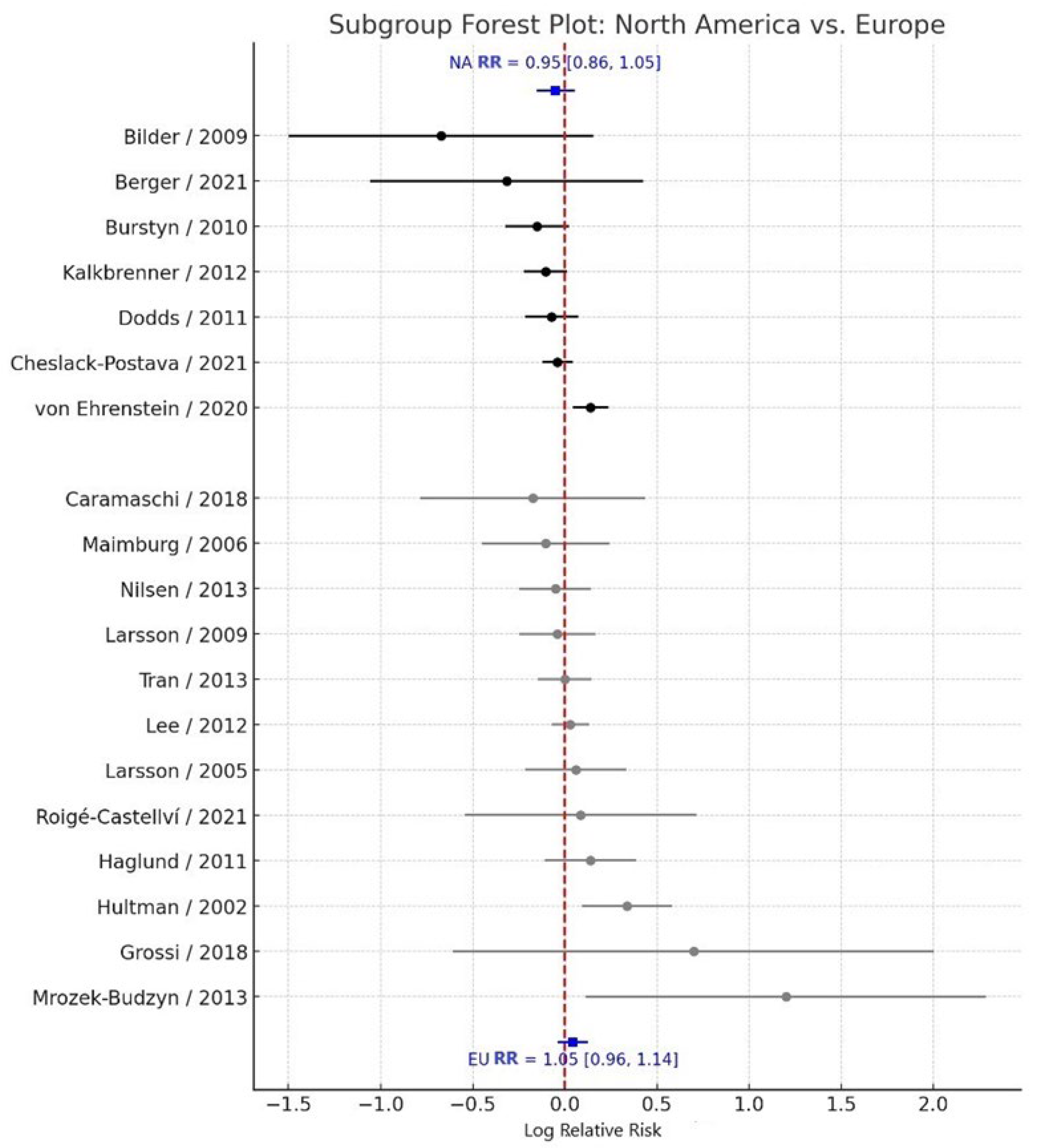

Subgroup analyses by geographic region revealed consistent null associations across all regions examined. Studies conducted in North America (k = 8) yielded a pooled RR = 0.95 (95% CI: 0.86–1.05), with moderate heterogeneity (I² = 48.9%). Similarly, studies conducted in Europe (k = 11) reported a pooled RR = 1.05 (95% CI: 0.96–1.14), also with moderate heterogeneity (I² = 53.2%) (

Figure 4). The between-subgroup heterogeneity test indicated no statistically significant difference between regional subgroups (Q<sub>between</sub> = 2.36, df = 2, p = 0.307). These findings suggest that the lack of association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and ASD risk is consistent across different geographic contexts.

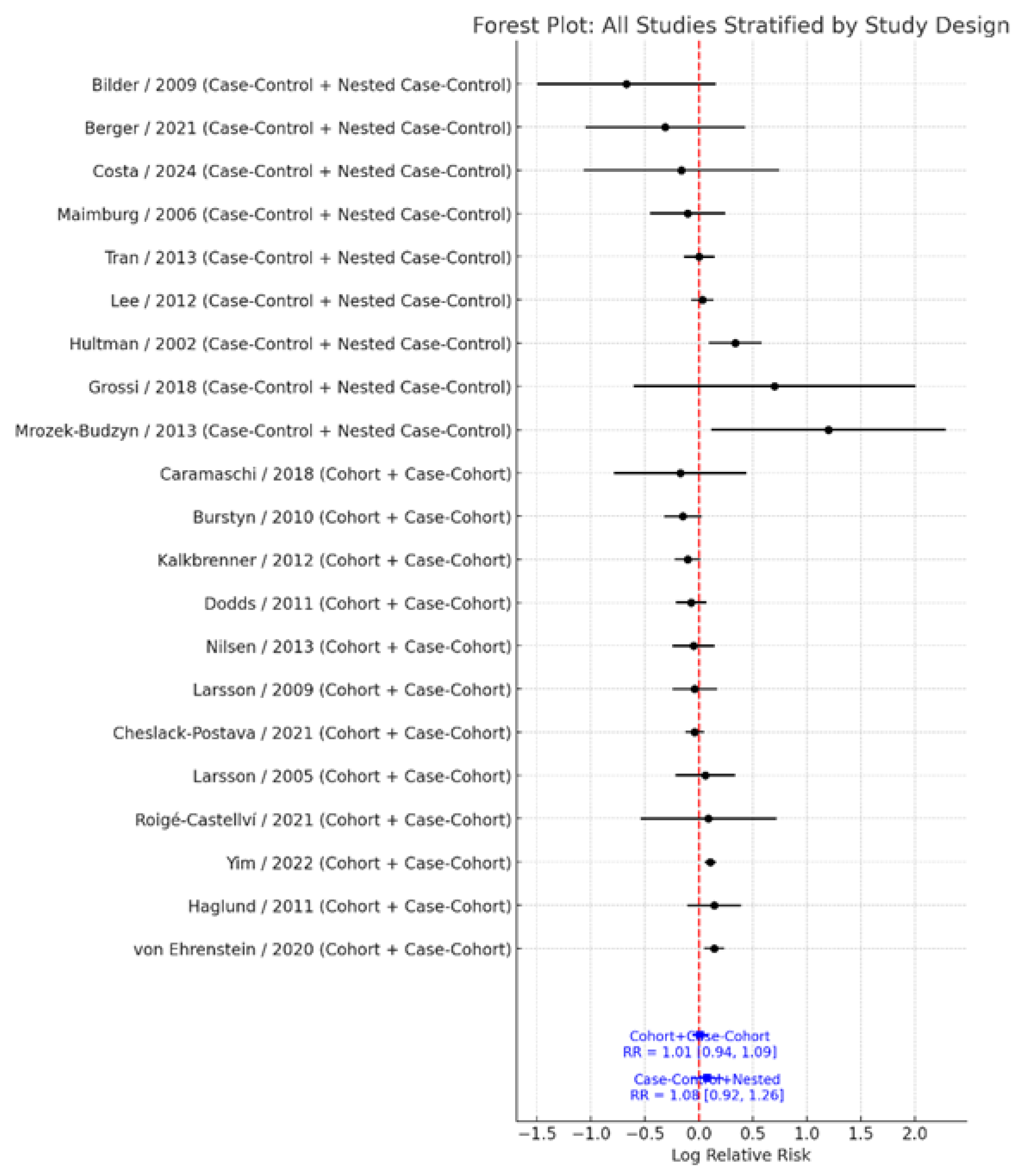

3.4. Subgroup Analysis by Study Design

When stratified by study design, results remained robust and non-significant. Cohort and case–cohort studies (k = 12) demonstrated a pooled RR = 1.01 (95% CI: 0.94–1.09), with moderate heterogeneity (I² = 49.7%). In contrast, case–control and nested case–control studies (k = 9) showed a pooled RR = 1.08 (95% CI: 0.92–1.26), with substantial heterogeneity (I² = 61.3%) (

Figure 5). The test for subgroup differences indicated no significant heterogeneity by study design (Q<sub>between</sub> = 0.00, df = 1, p = 0.991). These findings reinforce the consistency and stability of the overall null association across different study designs.

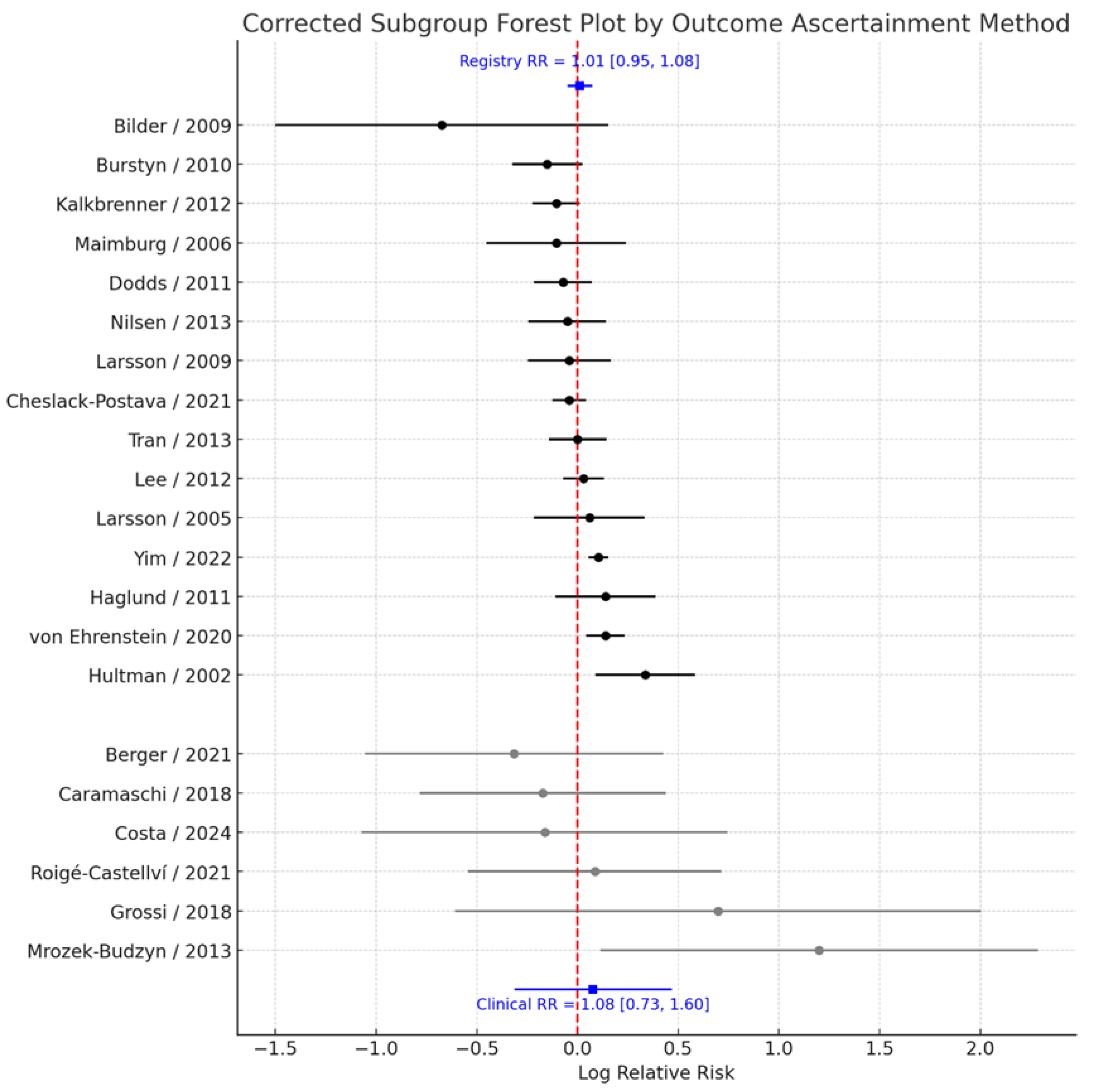

3.5. Subgroup Analysis by Outcome Ascertainment

To evaluate whether the method of ASD ascertainment influenced the observed association, studies were stratified according to whether outcome data were obtained from population-based registries or medical records versus clinical or survey-based assessments. Pooled analyses demonstrated that the estimated effect size was virtually identical regardless of the ascertainment approach. Among studies relying on registry or medical record data (k = 14), the pooled RR = 1.01 (95% CI: 0.95–1.08), with moderate heterogeneity (I² = 45.2%). Similarly, among studies using clinical or survey-based ascertainment (k = 7), the pooled RR = 1.08 (95% CI: 0.73–1.60), with substantial heterogeneity (I² = 64.1%) (

Figure 6). The test for subgroup differences revealed no evidence of heterogeneity between these groups (Q<sub>between</sub> = 0.00, p = 0.992). These findings indicate that the method used to ascertain ASD diagnosis does not materially affect the overall null association observed between prenatal smoking exposure and ASD risk.

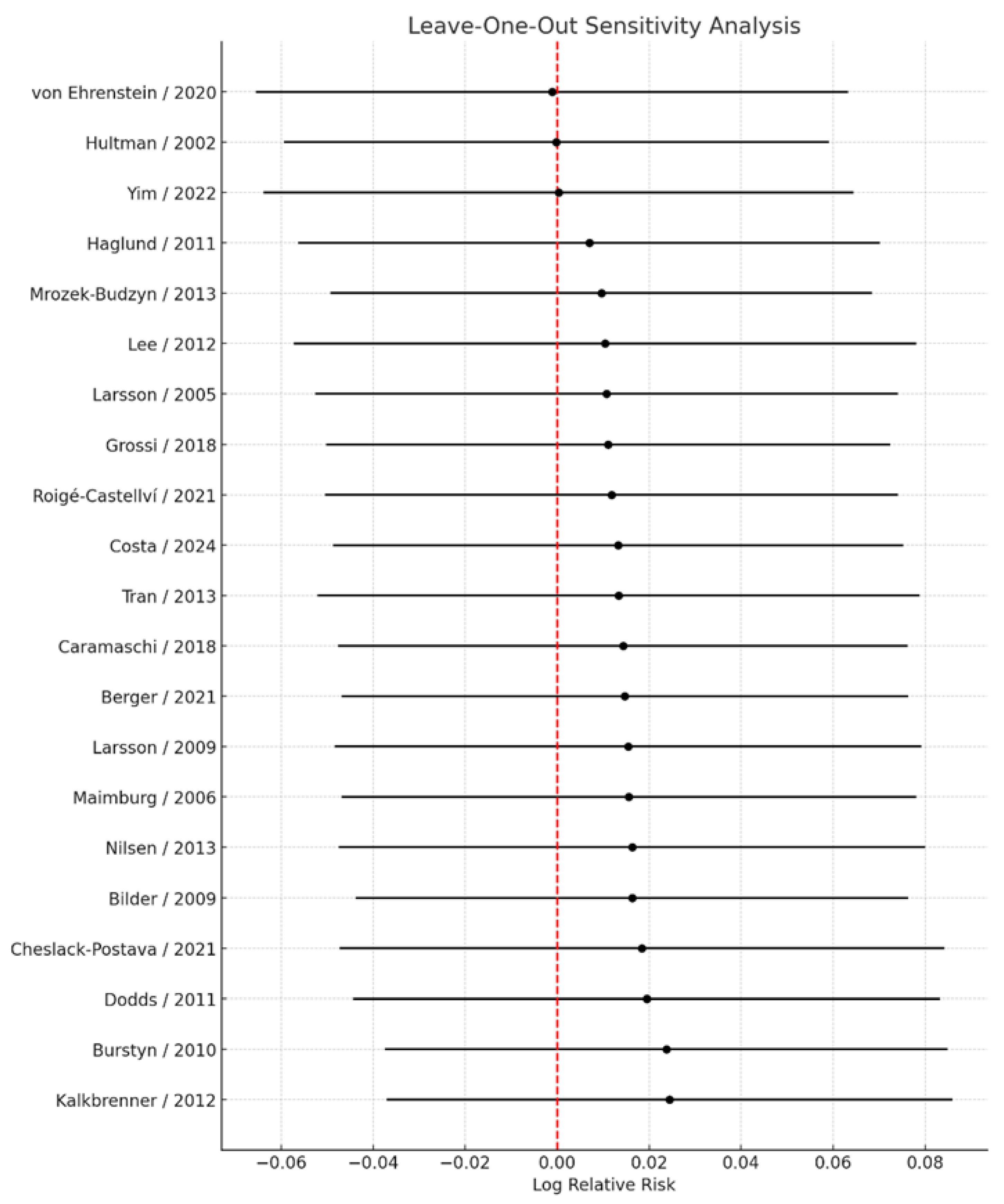

3.6. Sensitivity Analyses

Sensitivity analyses excluding studies that reported only crude estimates or that employed exposure definitions other than “any vs. none” yielded virtually unchanged results, with a pooled RR = 1.01 (95% CI: 0.94–1.08). These findings further support the robustness of the primary analysis. Leave-one-out sensitivity analyses (

Figure 7), in which each study was sequentially excluded from the meta-analysis, demonstrated that no single study materially influenced the overall pooled estimate. Across all iterations, the pooled relative risk ranged narrowly from 1.00 (95% CI: 0.94–1.07) to 1.02 (95% CI: 0.96–1.09), indicating that the direction, magnitude, and statistical significance of the association remained stable irrespective of individual study removal. The smallest pooled estimate was observed upon exclusion of the study by von Ehrenstein et al. [

13], whereas the largest was observed upon exclusion of the study by Kalkbrenner et al. [

26]; however, neither omission changed the overall interpretation.

Moreover, exclusion of potential outliers did not materially alter the magnitude or direction of the effect estimates, and the results remained consistent across alternative meta-analytic models.

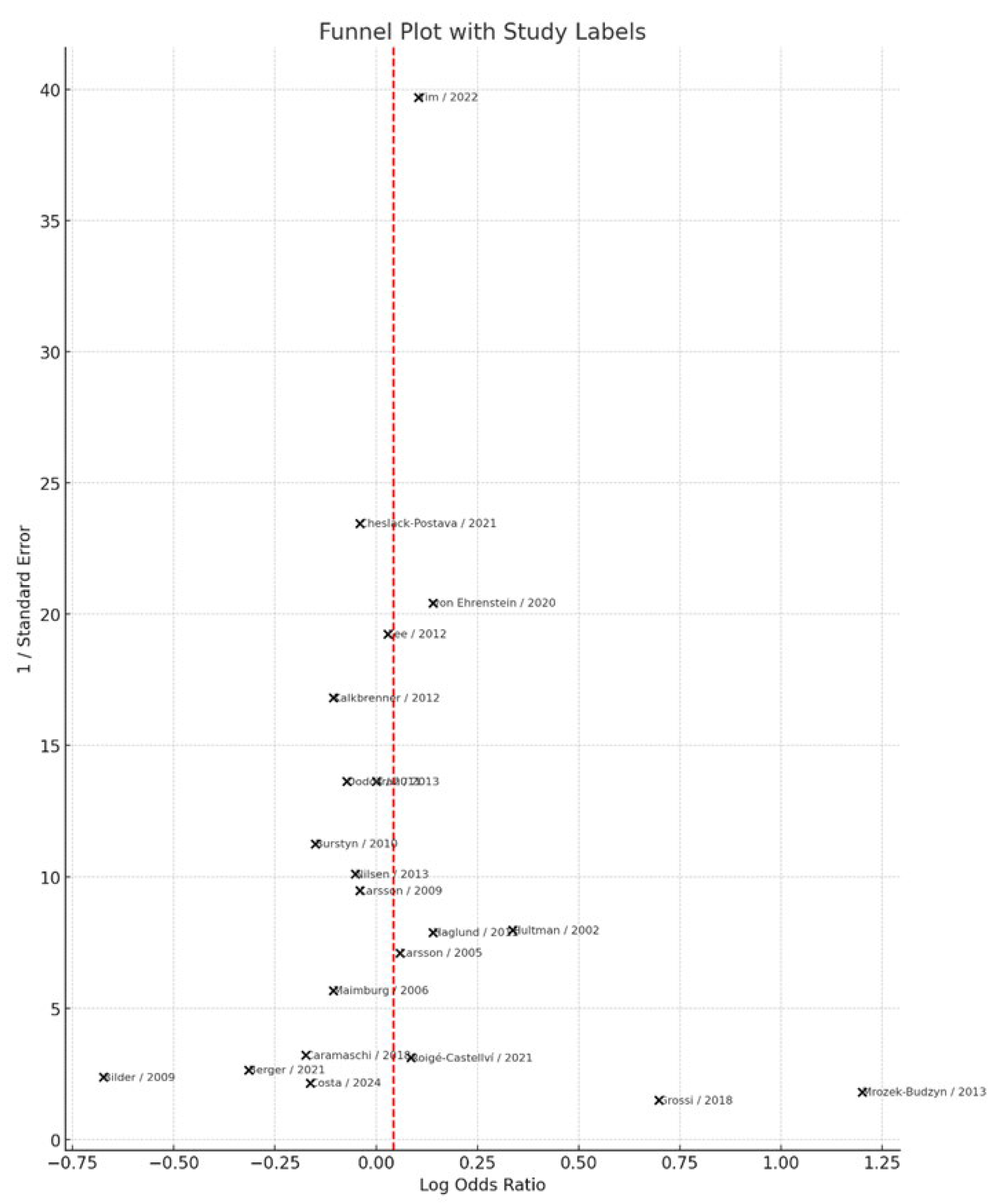

3.7. Publication Bias

Visual inspection of the funnel plot (

Figure 8) did not indicate substantial asymmetry, suggesting no clear evidence of publication bias. This observation was further supported by Egger’s regression test, which yielded a non-significant intercept (intercept = −0.45, p = 0.375), indicating that small-study effects are unlikely to have influenced the overall results.

4. Discussion

This meta-analysis, incorporating 21 epidemiological studies with a combined sample of several million mother–child pairs, found no statistically significant association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and ASD in offspring. The pooled relative risk was 1.01 (95% CI: 0.95–1.08), with moderate heterogeneity. Subgroup analyses by study design, geographic region, outcome ascertainment method, and adjustment status consistently demonstrated null associations. Sensitivity analyses, including leave-one-out procedures and the exclusion of unadjusted or non-binary exposure studies, confirmed the robustness of these findings. Collectively, these results suggest that maternal smoking during pregnancy is not a significant independent risk factor for ASD.

Our findings are consistent with and extend previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Rosen et al. [

37] reported no association between maternal smoking and ASD (OR = 1.02; 95% CI: 0.93–1.12) and found no meaningful variation by study design or adjustment for confounders. Tang et al. [

9] similarly reported a null association (OR = 1.02; 95% CI: 0.93–1.13), confirming robustness through extensive subgroup and sensitivity analyses. More recently, Hertz-Picciotto et al. [

38], using harmonized U.S. data from the ECHO consortium, found a modest, statistically significant association (OR = 1.44; 95% CI: 1.02–2.03) in sufficiently powered cohorts after excluding preterm and low-case-count cohorts; however, the overall pooled estimate remained non-significant (OR = 1.08; 95% CI: 0.72–1.61). Likewise, Jung et al. [

10] conducted an updated meta-analysis of 24 studies and concluded that there was no statistically significant association between maternal smoking and ASD (OR = 1.07; 95% CI: 0.97–1.18), emphasizing that earlier positive associations were likely due to residual confounding or methodological bias. Taken together, these reviews consistently support a null or very weak association, reaffirming the conclusions of our current analysis more than a decade later.

Although our findings (and prior meta-analyses) suggest no robust epidemiological association between maternal prenatal smoking and ASD, plausible biological mechanisms have been proposed. Experimental and preclinical studies indicate that prenatal nicotine exposure can dysregulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (e.g., via altered 11β-HSD2 or StAR expression) [

39,

40], interfere with nicotinic acetylcholine receptor–mediated signaling and neurotransmitter systems [

41,

42], and is associated with reduced brain volume or structural alterations in key regions [

43]. Epigenetic perturbations have also been observed: maternal smoking is associated with differential DNA methylation in newborns, including decreases in PRDM8 methylation and alterations in DLGAP2 [

44]; animal models of developmental nicotine exposure similarly show global hypomethylation and lower expression of DNMT3A, MeCP2, and HDAC2 [

41]. Despite these mechanistic pathways, the epidemiologic data do not provide consistent evidence for a causal effect on ASD. It remains possible that any true effect is modest and may be masked by residual confounding, measurement error, or influence via intermediate phenotypes not captured by ASD diagnosis (e.g., subclinical traits).

This meta-analysis has several strengths. First, it includes the largest number of studies to date, encompassing diverse geographic settings and study designs. Second, adjusted estimates were prioritized, and rigorous subgroup and sensitivity analyses were conducted to test the stability of findings. Third, potential sources of heterogeneity, including outcome ascertainment and exposure definition, were systematically explored.

Several limitations must also be acknowledged. Self-reported smoking data, often collected retrospectively, are subject to exposure misclassification and social desirability bias. Residual confounding—particularly by socioeconomic status, psychiatric comorbidities, and genetic vulnerability—cannot be fully ruled out. While this analysis focused on binary smoking exposure (“any vs. none”), dose–response relationships were infrequently reported and could not be synthesized meaningfully. Diagnostic practices for ASD vary across countries and over time, including differences in clinical training, healthcare access, diagnostic thresholds, and coding systems (e.g., DSM-IV, DSM-5, ICD), which may contribute to outcome misclassification or ascertainment bias and partly explain heterogeneity. Finally, although tests for publication bias were negative, subtle forms of selective reporting cannot be excluded.

5. Conclusions

This comprehensive meta-analysis found no evidence of a statistically significant association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and ASD in offspring. These findings align with previous meta-analyses and indicate that associations observed in individual studies are likely attributable to residual confounding, chance, or methodological differences rather than a causal effect. Nonetheless, given the well-established adverse effects of prenatal tobacco exposure on fetal growth, neurodevelopment, and perinatal outcomes, smoking cessation during pregnancy remains an essential public health priority.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, An.S.; methodology, A.P., M.T.-C., and An.S.; software, Ai.S., A.P., E.O.; validation, A.D., V.V., and An.S.; formal analysis, A.P. and An.S.; investigation, A.P. and Ai.S.; resources, M.T.-C.; data curation, A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P. and An.S.; writing—review and editing, An.S.; visualization, An.S.; supervision, An.S., A.D., V.V.; project administration, An.S.; funding acquisition, M.T.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

This systematic review and meta-analysis were based on data extracted from published literature. The original articles used as the source of data are fully cited in the References section. No new datasets were generated or analyzed in this study

Acknowledgments

Generative artificial intelligence tools were used only for linguistic editing and formatting consistency and did not contribute to data extraction, analysis, or interpretation. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

ASD

ADDM |

Autism spectrum disorder

Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network |

| OR |

Odds Ratio |

RR

HR |

Risk Ratio

Hazard Ratio |

CI

DSM

ICD

PRISMA

PROPERO

NOS

11β-HSD2

StAR

DNMT3A

MeCP2

HDAC2 |

Confidence Interval

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

International Classification of Diseases

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

Newcastle–Ottawa Scale

11β-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase Type 2

Steroidogenic Acute Regulatory Protein

DNA Methyltransferase 3 Alpha

Methyl CpG Binding Protein 2

Histone Deacetylase 2 |

Table A1. Characteristics of included studies (First author, Year, Country, Study design, Setting/Data source, Population/Eligibility, Sample size (total), Exposed (n), Unexposed (n), ASD cases (n), Exposure definition (maternal active smoking), Exposure assessment method, Timing of exposure, Smoking intensity categories, Passive/environmental tobacco smoke assessed, Negative-control or sibling analyses, Outcome definition, Outcome ascertainment, Age at ASD diagnosis/assessment, Effect type, Main adjusted estimate (value; 95% CI), Comparison encoded, Adjustment set, Subgroup estimates reported, Dose–response reported, NOS total stars).

References

- Lord, C.; Elsabbagh, M.; Baird, G.; Veenstra-Vanderweele, J. Autism spectrum disorder. Lancet 2018, 392, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maenner, M.J.; Shaw, K.A.; Bakian, A.V.; Bilder, D.A.; Durkin, M.S.; Esler, A.; Furnier, S.M.; Hallas, L.; Hall-Lande, J.; Hudson, A.; Hughes, M.M.; Patrick, M.; Pierce, K.; Poynter, J.N.; Salinas, A.; Shenouda, J.; Vehorn, A.; Warren, Z.; Constantino, J.N.; DiRienzo, M.; Fitzgerald, R.T.; Grzybowski, A.; Spivey, M.H.; Pettygrove, S.; Zahorodny, W.; Ali, A.; Andrews, J.G.; Baroud, T.; Gutierrez, J.; Hewitt, A.; Lee, L.C.; Lopez, M.; Mancilla, K.C.; McArthur, D.; Schwenk, Y.D.; Washington, A.; Williams, S.; Cogswell, M.E. Prevalence and Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2018. MMWR Surveill. Summ 2021, 70, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulou, K.; Sarantaki, A.; Katsaounou, P.; Lykeridou, A.; Georgakopoulou, V.E.; Diamanti, A. Impact of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) on fetal outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pneumon 2024, 37, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivilaki, V.G.; Diamanti, A.; Tzeli, M.; Patelarou, E.; Bick, D.; Papadakis, S.; Lykeridou, K.; Katsaounou, P. Exposure to active and passive smoking among Greek pregnant women. Tob. Induc. Dis 2016, 14, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgakopoulou, V.E.; Diamanti, A. Artificial Intelligence for Smoking Cessation in Pregnancy. Cureus 2024, 16, e63732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarasi, B.; Cornuz, J.; Clair, C.; Baud, D. Cigarette smoking during pregnancy and adverse perinatal outcomes: a cross-sectional study over 10 years. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suter, M.A.; Aagaard, K.M. The impact of tobacco chemicals and nicotine on placental development. Prenat. Diagn 2020, 40, 1193–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, D.M.; Zhang, L.; Wilkes, B.J.; Vaillancourt, D.E.; Biederman, J.; Bhide, P.G. Nicotine and the developing brain: Insights from preclinical models. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 2022, 214, 173355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Wang, Y.; Gong, X.; Wang, G. A meta-analysis of maternal smoking during pregnancy and autism spectrum disorder risk in offspring. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 10418–10431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.; Lee, A.M.; McKee, S.A.; Picciotto, M.R. Maternal smoking and autism spectrum disorder: meta-analysis with population smoking metrics as moderators. Sci. Rep 2017, 7, 4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caramaschi, D.; Taylor, A.E.; Richmond, R.C.; Havdahl, K.A.; Golding, J.; Relton, C.L.; Munafò, M.R.; Davey Smith, G.; Rai, D. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and autism: using causal inference methods in a birth cohort study. Transl. Psychiatry 2018, 8, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalkbrenner, A.E.; Meier, S.M.; Madley-Dowd, P.; Ladd-Acosta, C.; Fallin, M.D.; Parner, E.; Schendel, D. Familial confounding of the association between maternal smoking in pregnancy and autism spectrum disorder in offspring. Autism Res 2020, 13, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Ehrenstein, O.S.; Cui, X.; Yan, Q.; Aralis, H.; Ritz, B. Maternal Prenatal Smoking and Autism Spectrum Disorder in Offspring: A California Statewide Cohort and Sibling Study. Am. J. Epidemiol 2021, 190, 728–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheslack-Postava, K.; Sourander, A.; Hinkka-Yli-Salomäki, S.; McKeague, I.W.; Surcel, H.M.; Brown, A.S. A Biomarker-Based Study of Prenatal Smoking Exposure and Autism in a Finnish National Birth Cohort. Autism Res 2021, 14, 2444–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. Available online: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- DerSimonian, R.; Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control. Clin. Trials 1986, 7, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, M.; Davey Smith, G.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilder, D.; Pinborough-Zimmerman, J.; Miller, J.; McMahon, W. Prenatal, perinatal, and neonatal factors associated with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 2009, 123, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burstyn, I.; Sithole, F.; Zwaigenbaum, L. Autism spectrum disorders, maternal characteristics and obstetric complications among singletons born in Alberta, Canada. Chronic Dis. Can 2010, 30, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dodds, L.; Fell, D.B.; Shea, S.; Armson, B.A.; Allen, A.C.; Bryson, S. The role of prenatal, obstetric and neonatal factors in the development of autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord 2011, 41, 891–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haglund, N.G.; Källén, K.B. Risk factors for autism and Asperger syndrome. Perinatal factors and migration. Autism 2011, 15, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hultman, C.M.; Sparén, P.; Cnattingius, S. Perinatal risk factors for infantile autism. Epidemiology 2002, 13, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, H.J.; Eaton, W.W.; Madsen, K.M.; Vestergaard, M.; Olesen, A.V.; Agerbo, E.; Schendel, D.; Thorsen, P.; Mortensen, P.B. Risk factors for autism: Perinatal factors, parental psychiatric history, and socioeconomic status. Am. J. Epidemiol 2005, 161, 916–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, M.; Weiss, B.; Janson, S.; Sundell, J.; Bornehag, C.G. Associations between indoor environmental factors and parental-reported autistic spectrum disorders in children 6–8 years of age. Neurotoxicology 2009, 30, 822–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkbrenner, A.E.; Braun, J.M.; Durkin, M.S.; Maenner, M.J.; Cunniff, C.; Lee, L.C.; Pettygrove, S.; Nicholas, J.S.; Daniels, J.L. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and the prevalence of autism spectrum disorders, using data from the autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network. Environ. Health Perspect 2012, 120, 1042–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.K.; Gardner, R.M.; Dal, H.; Svensson, A.; Galanti, M.R.; Rai, D.; Dalman, C.; Magnusson, C. Brief report: Maternal smoking during pregnancy and autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord 2012, 42, 2000–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimburg, R.D.; Vaeth, M. Perinatal risk factors and infantile autism. Acta Psychiatr. Scand 2006, 114, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, R.M.; Surén, P.; Gunnes, N.; Alsaker, E.R.; Bresnahan, M.; Hirtz, D.; Hornig, M.; Lie, K.K.; Lipkin, W.I.; Reichborn-Kjennerud, T.; Roth, C.; Schjølberg, S.; Smith, G.D.; Susser, E.; Vollset, S.E.; Øyen, A.S.; Magnus, P.; Stoltenberg, C. Analysis of self-selection bias in a population-based cohort study of autism spectrum disorders. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol 2013, 27, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrozek-Budzyn, D.; Majewska, R.; Kieltyka, A. Prenatal, perinatal and neonatal risk factors for autism—study in Poland. Cent. Eur. J. Med 2013, 8, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, P.L.; Lehti, V.; Lampi, K.M.; Helenius, H.; Suominen, A.; Gissler, M.; Brown, A.S.; Sourander, A. Smoking during pregnancy and risk of autism spectrum disorder in a Finnish National Birth Cohort. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol 2013, 27, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, K.; Pearl, M.; Kharrazi, M.; Li, Y.; DeGuzman, J.; She, J.; Behniwal, P.; Lyall, K.; Windham, G. The association of in utero tobacco smoke exposure, quantified by serum cotinine, and Autism Spectrum Disorder. Autism Res 2021, 14, 2017–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.A.; Almeida, M.T.C.; Maia, F.A.; Rezende, L.F.; Saeger, V.S.A.; Oliveira, S.L.N.; Mangabeira, G.L.; Silveira, M.F. Maternal and paternal licit and illicit drug use, smoking and drinking and autism spectrum disorder. Cien. Saude Colet 2024, 29, e01942023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, E.; Migliore, L.; Muratori, F. Pregnancy risk factors related to autism: An Italian case-control study in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD), their siblings and of typically developing children. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis 2018, 9, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roigé-Castellví, J.; Murphy, M.M.; Voltas, N.; Solé-Navais, P.; Cavallé-Busquets, P.; Fernández-Ballart, J.; Ballesteros, M.; Canals-Sans, J. A prospective study of maternal exposure to smoking during pregnancy and behavioral development in the child. Journal of Child and Family Studies 2021, 30, 2204–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, G.; Roberts, A.; Lyall, K.; Ascherio, A.; Weisskopf, M.G. Multigenerational association between smoking and autism spectrum disorder: Findings from a nationwide prospective cohort study. Am. J. Epidemiol 2024, 193, 1115–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, B.N.; Lee, B.K.; Lee, N.L.; Yang, Y.; Burstyn, I. Maternal smoking and autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analysis. J. Autism Dev. Disord 2015, 45, 1689–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertz-Picciotto, I.; Korrick, S.A.; Ladd-Acosta, C.; Karagas, M.R.; Lyall, K.; Schmidt, R.J.; Dunlop, A.L.; Croen, L.A.; Dabelea, D.; Daniels, J.L.; Duarte, C.S.; Fallin, M.D.; Karr, C.J.; Lester, B.; Leve, L.D.; Li, Y.; McGrath, M.; Ning, X.; Oken, E.; Sagiv, S.K.; Sathyanarayana, S.; Tylavsky, F.; Volk, H.E.; Wakschlag, L.S.; Zhang, M.; O'Shea, T.M.; Musci, R.J.; program collaborators for Environmental influences on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO). Maternal tobacco smoking and offspring autism spectrum disorder or traits in ECHO cohorts. Autism Res 2022, 15, 551–569. [CrossRef]

- Wells, A.C.; Lotfipour, S. Prenatal nicotine exposure during pregnancy results in adverse neurodevelopmental alterations and neurobehavioral deficits. Adv. Drug Alcohol Res 2023, 3, 11628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.; Xia, L.P.; Shen, L.; Lei, Y.Y.; Liu, L.; Zhang, L.; Magdalou, J.; Wang, H. Prenatal nicotine exposure enhances the susceptibility to metabolic syndrome in adult offspring rats fed high-fat diet via alteration of HPA axis-associated neuroendocrine metabolic programming. Acta Pharmacol. Sin 2013, 34, 1526–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buck, J.M.; O’Neill, H.C.; Stitzel, J.A. Developmental nicotine exposure engenders intergenerational downregulation and aberrant posttranslational modification of cardinal epigenetic factors in the frontal cortices, striata, and hippocampi of adolescent mice. Epigenetics Chromatin 2020, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proud, E.K.; Rodríguez-Ruiz, M.; Gummerson, D.M.; Vanin, S.; Hardy, D.B.; Rushlow, W.J.; Laviolette, S.R. Chronic nicotine exposure induces molecular and transcriptomic endophenotypes associated with mood and anxiety disorders in a cerebral organoid neurodevelopmental model. Front. Pharmacol 2024, 15, 1473213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, L.; Yoon, C.D.; LaJeunesse, A.M.; Schirmer, L.G.; Rapallini, E.W.; Planalp, E.M.; Dean, D.C. Prenatal substance exposure and infant neurodevelopment: A review of magnetic resonance imaging studies. Front. Hum. Neurosci 2025, 19, 1613084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlachou, M.; Kyrkou, G.; Georgakopoulou, V.E.; Kapetanaki, A.; Vivilaki, V.; Spandidos, D.A.; Diamanti, A. Smoke signals in the genome: Epigenetic consequences of parental tobacco exposure (Review). Biomed. Rep 2025, 23, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).