1. Introduction

Chemotherapy-induced alopecia (CIA) remains one of the most-distressing and visible adverse effects of anticancer therapy (Saraswat and Chopra, 2019; Wikramanayake et al., 2023; Kaufman et al., 2025). Among commonly-used chemotherapeutic agents, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), an antimetabolite widely employed in the management of solid tumours such as colorectal, breast, and head/neck cancers has been consistently-implicated in damaging rapidly-proliferating cells, including those in the hair follicle matrix (Ghafouri-Fard et al., 2021; Olofinnade et al., 2025). The resulting alopecia, though often reversible, can cause significant psychosocial distress, compromise self-image, reduce treatment adherence, and negatively-affect overall quality of life (Onaolapo et al., 2018a; Nozawa et al., 2023).

The pathophysiology of 5-FU–induced alopecia extends beyond direct cytotoxicity, as 5-FU disrupts DNA synthesis in follicular keratinocytes; inducing apoptosis, dystrophy, and premature entry into the catagen phase (Kang et al., 2025). In addition, several studies have reported that 5-FU generates reactive oxygen species (ROS), triggering oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and microvascular impairment within the follicular environment (Onaolapo et al., 2018b; Onaolapo et al., 2023; Öztürk et al., 2025). This oxidative milieu promotes inflammatory cytokine release and tissue injury, ultimately disturbing the balance between hair growth (anagen) and regression (catagen) phases. Therefore, therapeutic strategies capable of attenuating oxidative stress and inflammation while supporting follicular integrity and regeneration, may mitigate the severity of chemotherapy-induced alopecia.

Phenytoin, a hydantoin derivative primarily used as an anticonvulsant, has long been recognised for inducing hypertrichosis as a side-effect during chronic administration (Onaolapo et al., 2018a). This observation has spurred interest in its potential hair growth promoting properties. Mechanistic studies indicate that phenytoin stimulates fibroblast proliferation, collagen synthesis, angiogenesis, and epithelial repair—biological processes essential for follicular health and dermal recovery. Additionally, phenytoin exhibits notable anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities, reducing lipid peroxidation and suppressing proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 (Nazıroğlu and Yürekli, 2013). Although previous studies have evaluated topical phenytoin formulations for wound healing and tissue regeneration (Keppel Hesselink, 2018; Fattahi et al., 2022; Sheir et al., 2022), the systemic (oral) administration of phenytoin as a protective agent against chemotherapy-induced hair loss remains underexplored. However, oral delivery offers sustained systemic bioavailability and may enhance antioxidant and anti-inflammatory defense mechanisms throughout the hair follicle microenvironment.

In contrast, spironolactone, a potassium-sparing diuretic and androgen receptor antagonist, has gained attention for its ability to counteract androgen-related hair disorders such as female-pattern hair loss (Müller Ramos et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023). Its reported benefits in post-chemotherapy alopecia are thought to arise from antiandrogenic, anti-inflammatory, and collagen-stabilising effects that support follicular repair (James et al., 2022; Saleh et al., 2025). However, unlike phenytoin, spironolactone’s hair growth–promoting potential appears to be observable within a limited dose range, necessitating evaluation at a single dose that reflects optimal pharmacological efficacy while minimising the risk of systemic hormonal alterations (Burns et al., 2020; James et al., 2022; Aleissa, 2023; Müller Ramos et al., 2023).

In this study, we employed a rodent model of 5-FU–induced alopecia to evaluate and compare the protective effects of two oral doses of phenytoin chosen to assess both low- and high-dose response relationships, and a single optimal dose of spironolactone selected from literature-based efficacy and safety data (James et al, 2022). The dual-dose phenytoin design allows exploration of dose-dependent efficacy and toxicity thresholds, thereby providing a broader understanding of its possible therapeutic effect.

We hypothesise that both phenytoin and spironolactone will mitigate 5-FU–induced alopecia by attenuating oxidative stress and inflammatory injury, while enhancing collagen deposition/organisation, and follicular regeneration. This study therefore seeks to elucidate the comparative and potentially complementary protective mechanisms of these agents, contributing to the development of adjunctive strategies that preserve hair follicular health and improve patient well-being during chemotherapy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Drugs

Phenytoin (100 mg capsules, Dilantin®, Pfizer Inc, Nigeria), 5-fluorouracil (5 Flucel®, 250 mg/5 ml injection), Spironolactone (25 mg, Minoxytop, Life Health, Nigeria), Normal Saline.

2.2. Animal

Adult male Wistar rats (Empire Breeders, Ara, Osun State, Nigeria) were used in this study. Rats were housed in groups of six in metabolic cages in temperature-controlled quarters (22–25◦C) with 12 h of light daily (lights on at 7.00 a.m.). Rats were fed commercial rodent chow (Calories: 29% protein, 13% fat, 58% carbohydrate) and allowed access to feed and water ad-libitum. All procedures were in accordance with the approved institutional protocols and within the provisions for animal care and use prescribed in the scientific procedures on living animals, European Council Directive (EU2010/63).

2.3. Experimental Method

Forty rats weighing between 130 -150g each used for this study were randomly-assigned to five groups of eight rats each (n = 8). Animals assigned as group 1(normal control) were administered distilled water at 10 ml/kg daily, group 2 was the 5-Fluorouracil (5FU) control, while animals in groups 3, 4 and 5 were administered phenytoin (PHE) at 50 mg/kg/body weight, PHE at 100 mg/kg/ body weight and spironolactone (standard drug against male pattern baldness) at 20 mg/kg/bodyweight respectively. Single spironolactone dose was calculated from human effective dose of approximately 200 mg in a 70 kg human (Burns et al., 2020; Aleissa, 2023). To standardise hair cycle stages across all experimental groups, the flank skin was depilated to synchronously induce the anagen phase. This procedure ensured that pharmacological treatments commenced when all hair follicles were at an equivalent stage of active growth, rather than at varying stages of spontaneous anagen initiation (Onaolapo et al., 2018a; Wang et al., 2025). On post-depilation day 9 (anagen VI) and experimental day 1, animals in group 1 received a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) saline at 2 ml/kg while rats in groups 2, 3, 4 and 5 were administered i.p. 5-FU. Beginning from experimental day 2, animals were administered distilled water, phenytoin or spironolactone daily for 28 consecutive days. Feed intake and body weight were assessed daily and weekly respectively, while animals were also observed for changes in hair development. The flank area was photographed on days 0, 7, 14 and 21. At the end of the experimental period, rats were euthanised by cervical dislocation, blood was taken for estimation of Malondialdehyde (MDA), Total Antioxidant Capacity, Tumour necrosis factor-α, Interleukin-10 and interleukin-1β. Strands of newly-grown hair were collected from the depilated flank area for microscopic examination, while skin samples from the same region were excised and processed for histological analysis.

2.3.1. Induction of Anagen

Under isoflurane anaesthesia, rats in the telogen phase were induced to enter anagen through depilation of all telogen hair shafts. Depilation paste was applied to the flank region to ensure uniform removal of telogen hairs and synchronised initiation of follicular growth. This procedure triggers the immediate transition of telogen follicles into anagen stages I–VI, typically marked by progressive darkening and thickening of the skin within 5–6 days, maturation of anagen VI follicles by days 8–9, and the subsequent emergence of new hair shafts.

2.4. Assessment of Chemotherapy-Induced Hair Loss

Following a single intraperitoneal dose of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) on day 9, the flank skin of all rats was examined daily for up to 28 days to monitor hair regrowth, reflecting the transition of anagen follicles through catagen to telogen. Visible changes in hair growth and skin appearance were documented and photographed on days 7, 14, and 21. At study termination, all animals were euthanised; flank skin samples were collected for histological evaluation, and hair shafts were obtained for microscopic analysis.

2.5. Microscopic Evaluation of Hair Strands

Hair strands collected from the depilated flank area were examined microscopically to evaluate strand thickness, banding pattern, follicular diameter, and colour characteristics. Morphometric analyses were performed (Image J) using six hair strands from at least five animals per group. Bright-field images were calibrated with a digital micrometer to convert pixels to micrometres, and this scale was applied globally to all images. Colour intensity was quantified using the colour histogram tool, while the micrometer function was used to measure cortical and medullary widths.

2.6. Biochemical Assays

2.6.1. Lipid Peroxidation

Lipid peroxidation levels were evaluated by measuring malondialdehyde content assessed as levels of thiobarbituric acid reactive substance in the biological samples. Combination of free malondialdehyde and thiobarbituric acid reactive substance forms a coloured complex which can be measured spectrophotometrically as previously described (Onaolapo et al., 2017; Olofinnade et al., 2021). Concentration of which is expressed as pg/ml.

2.6.2. Antioxidant Status

Total antioxidant capacity was assayed using the Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity Assay method that assesses the ability of antioxidants within a given sample to react with oxidised products as previously described (Akinsehinwa et al., 2025, Ajao et al., 2025).

2.6.3. Tumour Necrosis Factor-α, Interleukin (IL) -10 and Interleukin 1β

Tumour necrosis factor -α, interleukin (IL)-10 and IL-1β levels were measured using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay techniques with commercially-available kits (Biovision Inc., Milpitas, CA, USA) as previously described (Olofinnade et al., 2021)

2.7. Histology

Following euthanasia, the depilated flank skin was excised and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for routine histological processing and haematoxylin and eosin staining. Longitudinal sections were examined for morphological changes in the skin and hair follicles to determine whether the macroscopic alterations corresponded with transitions in hair follicle cycling (Onaolapo et al., 2018a)

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Data was analysed using Chris Rorden’s ezANOVA for windows (version 0.98). We tested the hypothesis that repeated oral administration of phenytoin and spironolactone could significantly enhance hair regrowth in 5FU-treated rats; and alter oxidative stress parameters and inflammatory cytokines. One-factor ANOVA (between-subject factor) was used to analyse their effects on body weight, antioxidant status, and hair shaft/follicle characteristics.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Phenytoin and Spironolactone on Body Weight

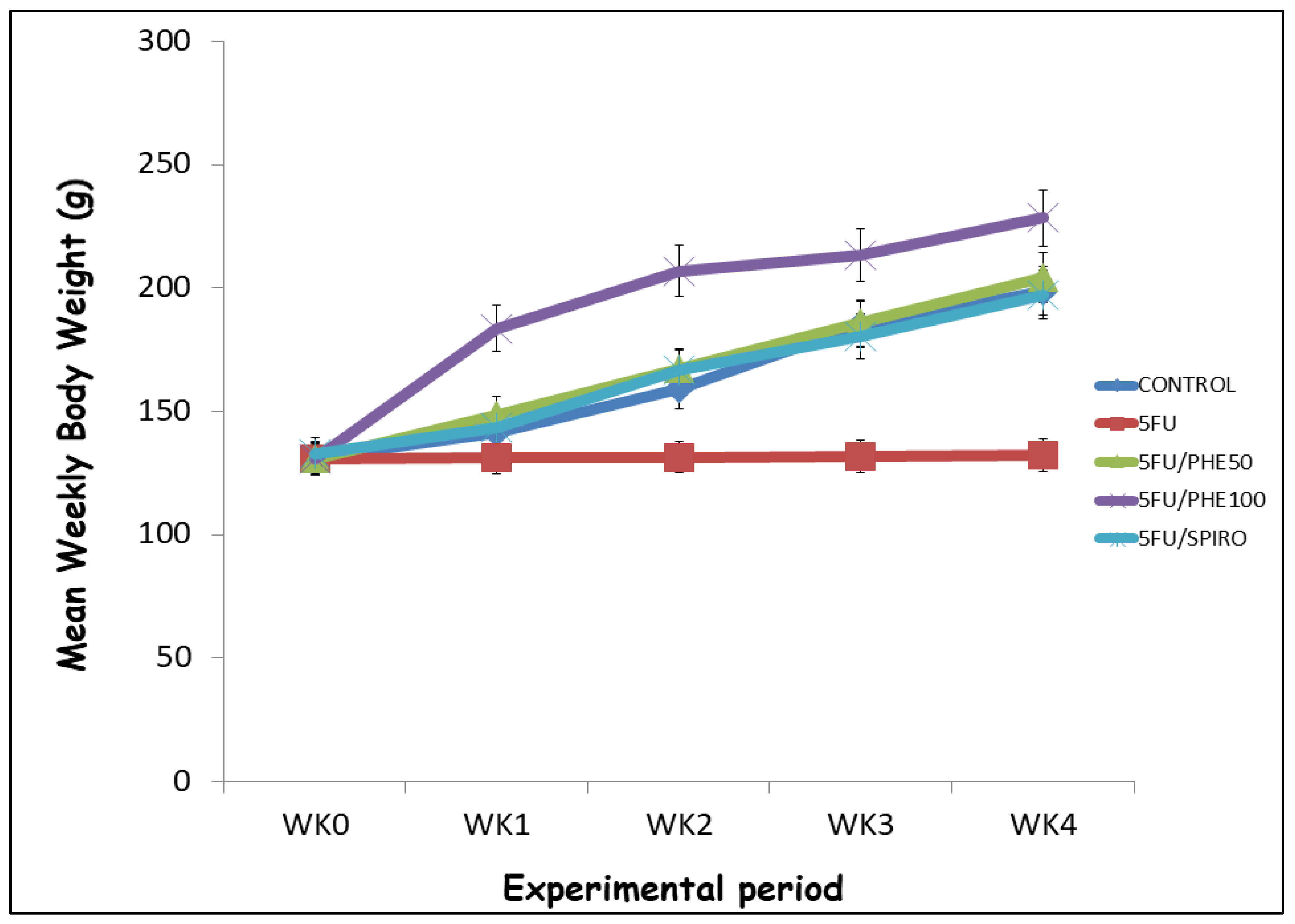

Figure 1 shows the mean body weight was monitored weekly over a 4-week experimental period in all groups: Control, 5-FU, 5-FU+Phenytoin (50 mg/kg), 5-FU+Phenytoin (100 mg/kg), and 5-FU+Spironolactone. At baseline (week 0), there were no significant differences in body weight among the groups (p > 0.05). Post hoc analysis (Tukey’s test) showed that 5-FU-treated rats exhibited a marked suppression of weight gain from week 1 through week 4 compared with the control group (p < 0.01). In contrast, administration of phenytoin or spironolactone significantly ameliorated this weight loss, with the 5FU/SPIRO and 5FU/PHE50 groups showing near-normal growth trajectories by week 4 (p < 0.05 vs. 5-FU). By the fourth week, mean body weights were approximately 2100 ± 5 g (Control), 130 ± 6 g (5-FU), 200 ± 7 g (5FU/PHE50), 240 ± 8 g (5FU/PHE100), and 180 ± 9 g (5FU/SPIRO).

3.2. Effect of Phenytoin and Spironolactone on Feed Intake

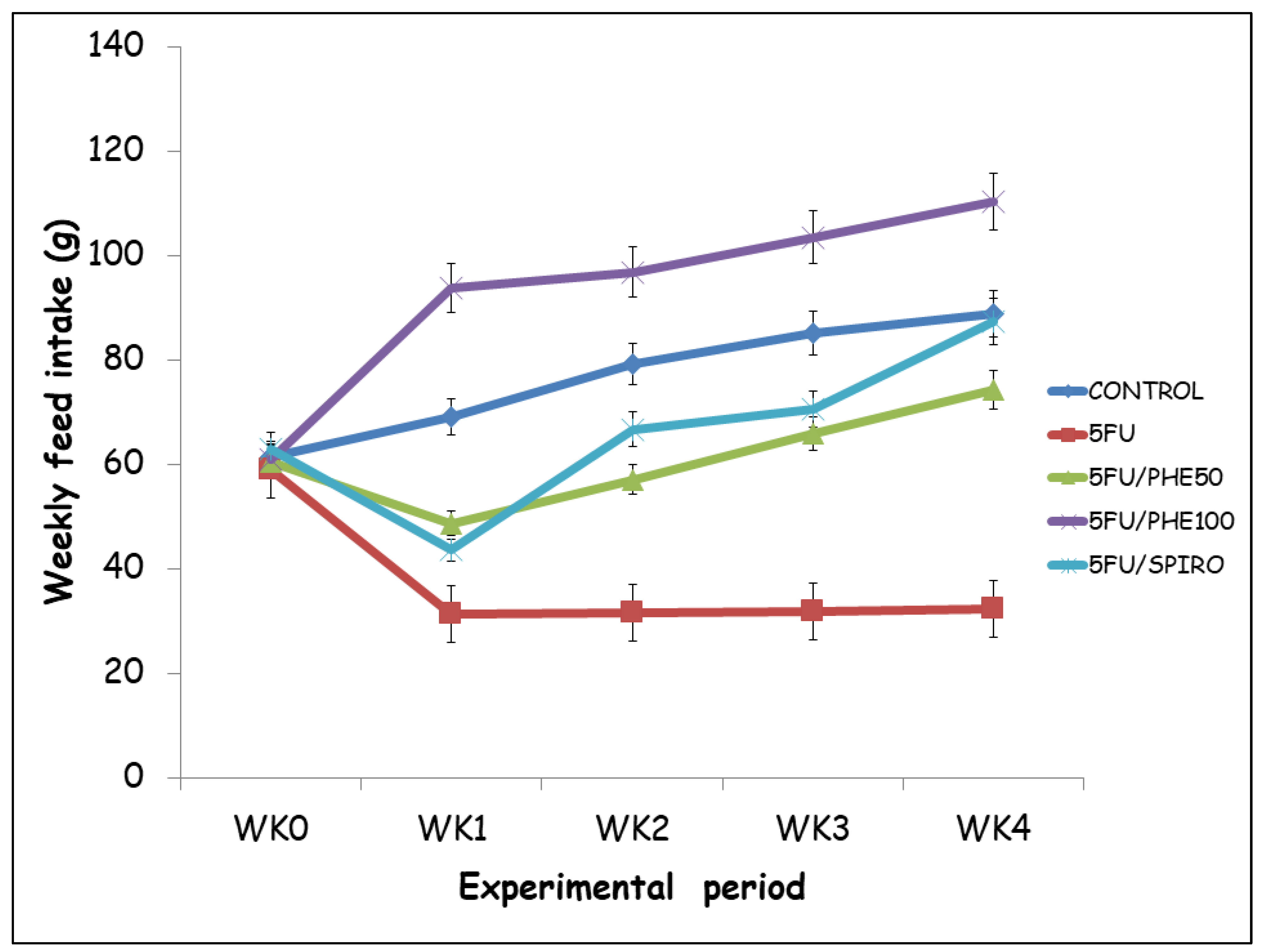

Figure 2 shows mean weekly feed intake (g) was monitored across the 4-week experimental period in all groups. At baseline (week 0), there were no significant differences in feed consumption among the groups (p > 0.05). However, following 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) administration, a marked decline in feed intake was observed from week 1 in the 5-FU-treated group compared with the control (p < 0.01). Post hoc analysis (Tukey’s test) revealed that administration of phenytoin (both 50 and 100 mg/kg) or spironolactone significantly improved feed intake compared with the 5-FU group from week 2 onwards (p < 0.05). Rats in the 5FU/PHE100 group showed marked increase in feed intake across all weeks compared to control or 5FU. By week 4, mean feed intake in the control, 5FU/PHE50, and 5FU/SPIRO groups approached vehicle control levels, while the 5-FU-only group maintained the lowest intake throughout the study. The 5FU/PHE 100 group showed the greatest recovery in feeding behaviour, followed closely by 5FU/SPIRO.

3.3. Effect of Phenytoin and Spironolactone on Hair Growth (Photographic Documentation)

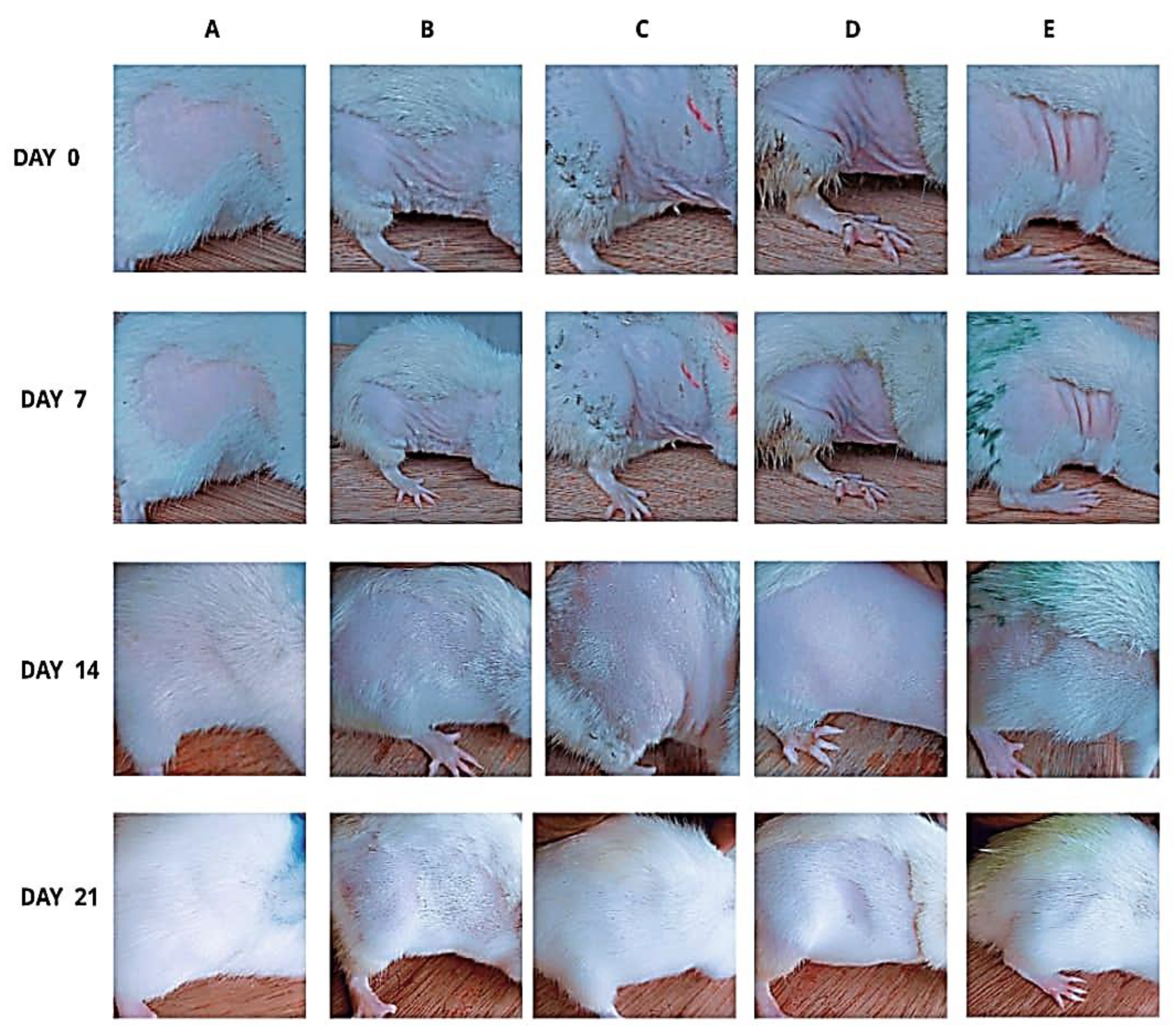

Figure 3 presents the gross morphological changes due to effect of phenytoin and spironolactone on 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)-induced alopecia and hair regrowth in Wistar rats. In rodents, hair growth follows a cranio-caudal pattern, making the extent of regrowth on depilated flank skin a useful visual indicator of follicular recovery and anagen progression. By experimental day 7 which was 16 days post-depilation, rats in the control group demonstrated rapid and uniform hair regrowth, with approximately 80% showing complete coverage of the depilated flank skin. In contrast, rats treated with 5-FU alone exhibited marked inhibition of hair regrowth, with only about 20% displaying sparse or patchy hair, indicating chemotherapy-induced alopecia. Rats administered phenytoin (5FU/PHE50 and 5FU/PHE100) showed evidence of hair thinning and delayed (but progressive) regrowth in approximately 47% and 48% of rats, respectively; and displayed partial hair coverage by experimental day 14. Notable is the fact that the rate and extent of regrowth in these groups were greater than those observed in the 5-FU-only group. Interestingly, the 5FU/SPIRO group exhibited faster and more-uniform regrowth compared with all 5-FU-treated groups. By day 14, approximately 55% of rats in this group showed visible hair coverage, indicating earlier follicular recovery. By day 21, complete hair regrowth was observed in 90% of control rats, while only 30% of 5-FU-only rats showed full coverage of the depilated region. In contrast, 60%, 62%, and 75% of rats in the 5FU/PHE50, 5FU/PHE100, and 5FU/SPIRO groups, respectively, exhibited near-complete or complete regrowth.

3.4. Effect of Phenytoin and Spironolactone on Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Parameters

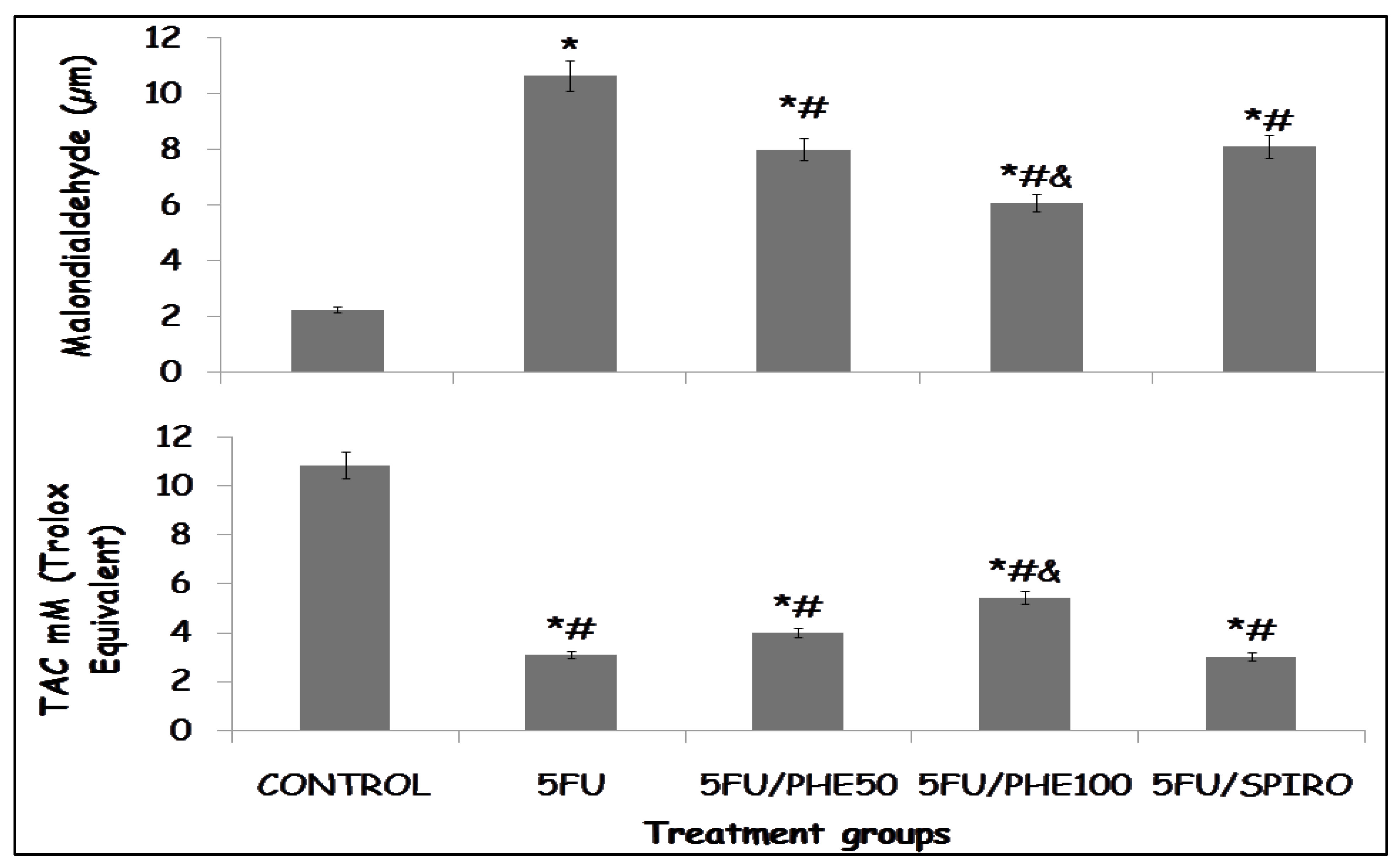

Figure 4 illustrates the effect of phenytoin and spironolactone on indices of oxidative stress in rats following 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) administration. The upper panel represents lipid peroxidation, expressed as malondialdehyde (MDA) concentration, while the lower panel shows total antioxidant capacity (TAC). A significant increase in MDA levels was observed in all 5-FU–treated groups compared to the control group (p < 0.01), indicating increased lipid peroxidation. The highest MDA concentration was seen in the 5-FU-only group, where it was significantly greater than in the 5FU/PHE50, 5FU/PHE100, and 5FU/SPIRO groups (p < 0.05). Co-administration of phenytoin or spironolactone resulted in a reduction in MDA levels relative to 5-FU alone, suggesting attenuation of 5-FU–induced oxidative damage.

Conversely, TAC was markedly reduced in the 5-FU-only group compared to the control (p < 0.01), consistent with increased oxidative stress. Treatment with phenytoin or spironolactone significantly improved TAC values (p < 0.05 vs. 5-FU), indicating restoration of antioxidant defense mechanisms. The 5FU/SPIRO group exhibited the greatest improvement, followed by 5FU/PHE100 and 5FU/PHE50, suggesting a dose-related or compound-specific enhancement of antioxidant status.

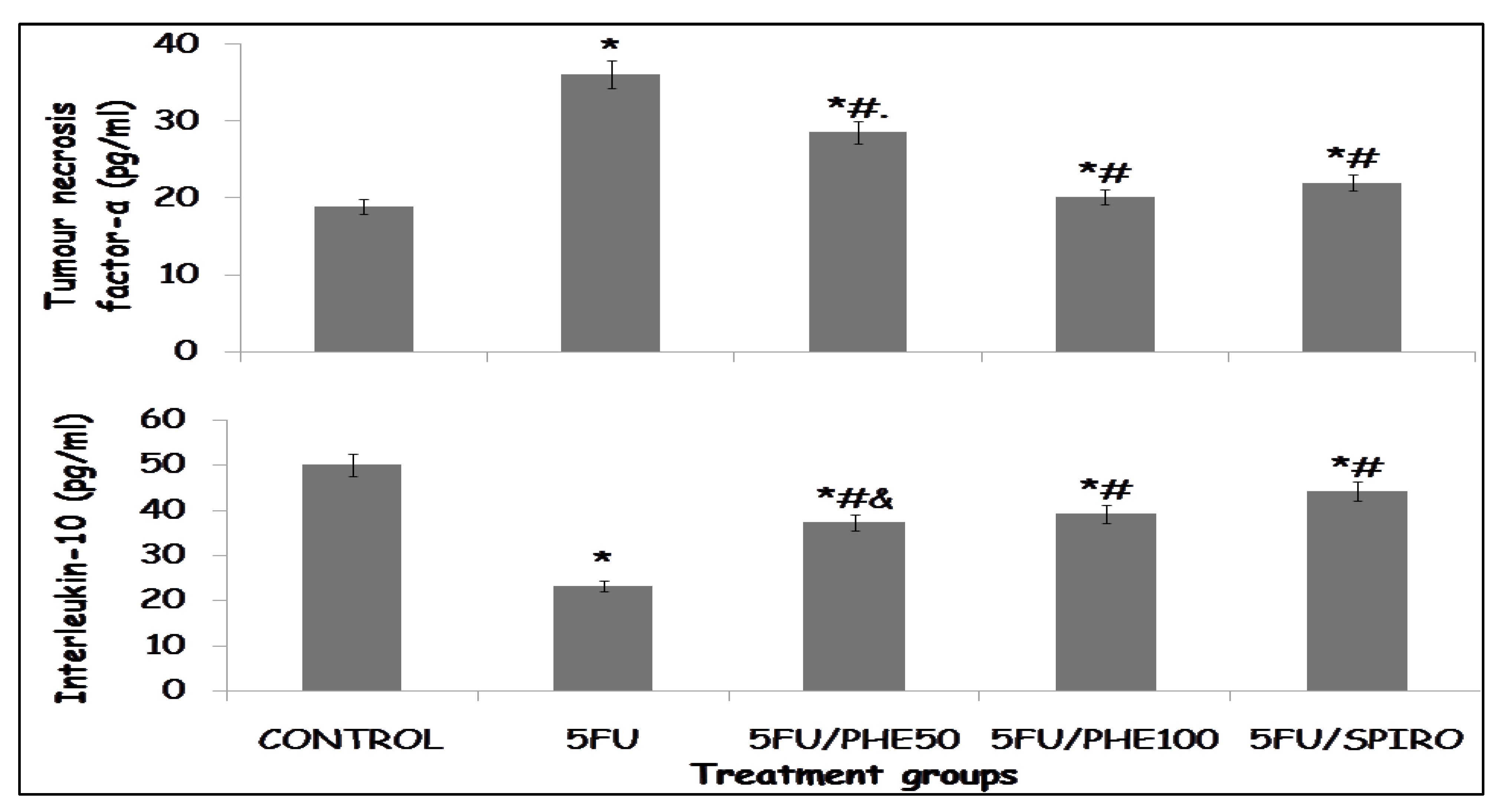

3.5. Effect of Phenytoin and Spironolactone on Inflammatory Cytokines

Figure 5a shows the effects of phenytoin and spironolactone on tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α. Upper panel) and interleukin-10 (IL-10, lower panel) in rats following 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) administration. A significant elevation in TNF-α levels was observed in the 5-FU-only group compared with the control group (p < 0.01), indicating heightened inflammatory activity. Administration of phenytoin (5FU/PHE50 and 5FU/PHE100) or spironolactone (5FU/SPIRO) significantly reduced TNF-α concentrations compared with 5-FU alone (p < 0.05), suggesting a suppressive effect on pro-inflammatory signaling.

Similarly, 5-FU administration led to a marked reduction in IL-10 levels relative to the control group (p < 0.01), consistent with impaired anti-inflammatory regulation. Treatment with phenytoin or spironolactone significantly restored IL-10 levels compared with 5-FU alone (p < 0.05), indicating reactivation of anti-inflammatory responses.

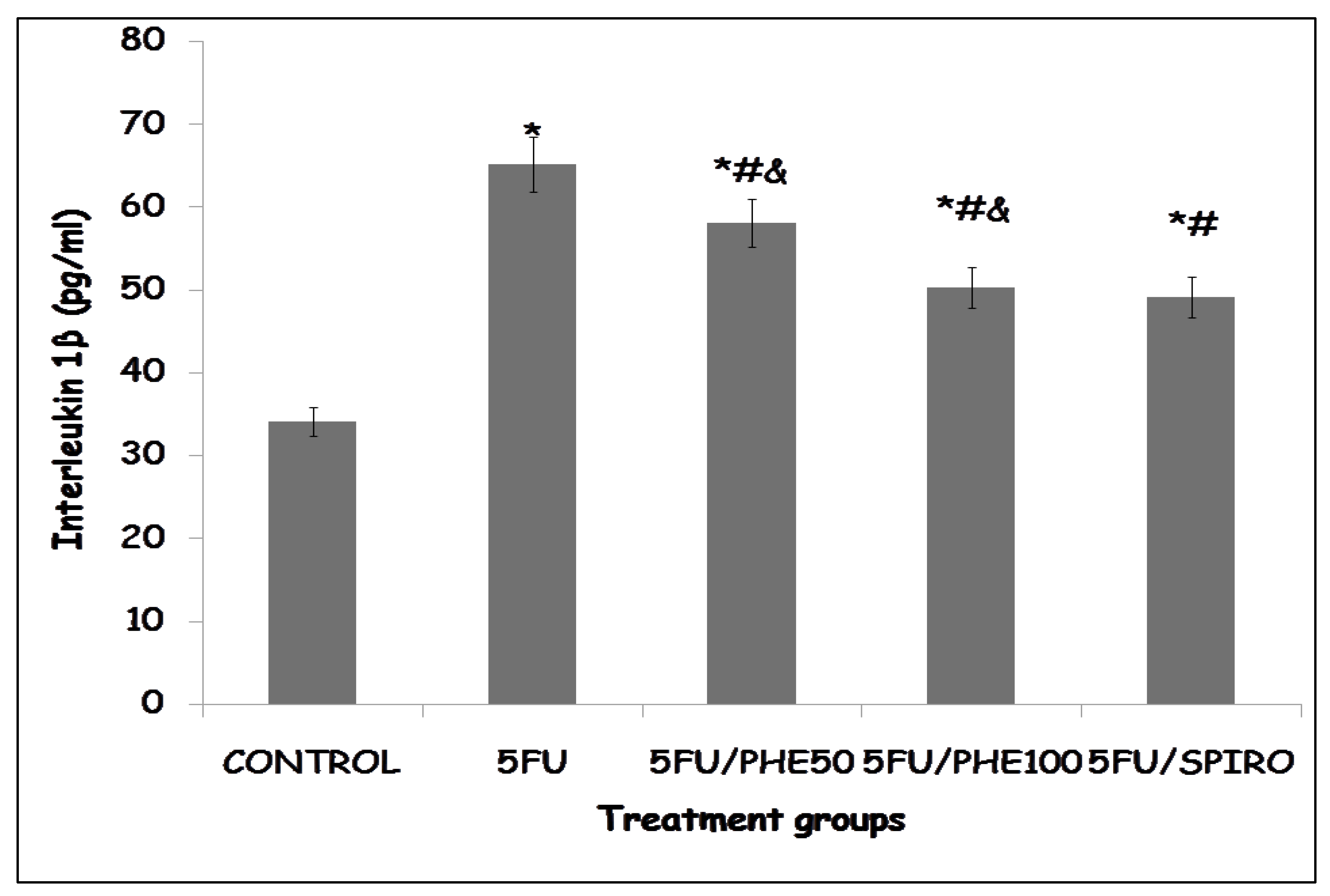

Figure 5b shows the effect of phenytoin and spironolactone on levels of interleukin I β. There was a significant elevation of IL-1β level in the 5-FU-only group compared with control (p < 0.01). This effect was attenuated in all treatment groups, with reductions in IL-1β concentration observed in the 5FU/PHE50, 5FU/PHE100, and 5FU/SPIRO groups (p < 0.05 vs. 5-FU).

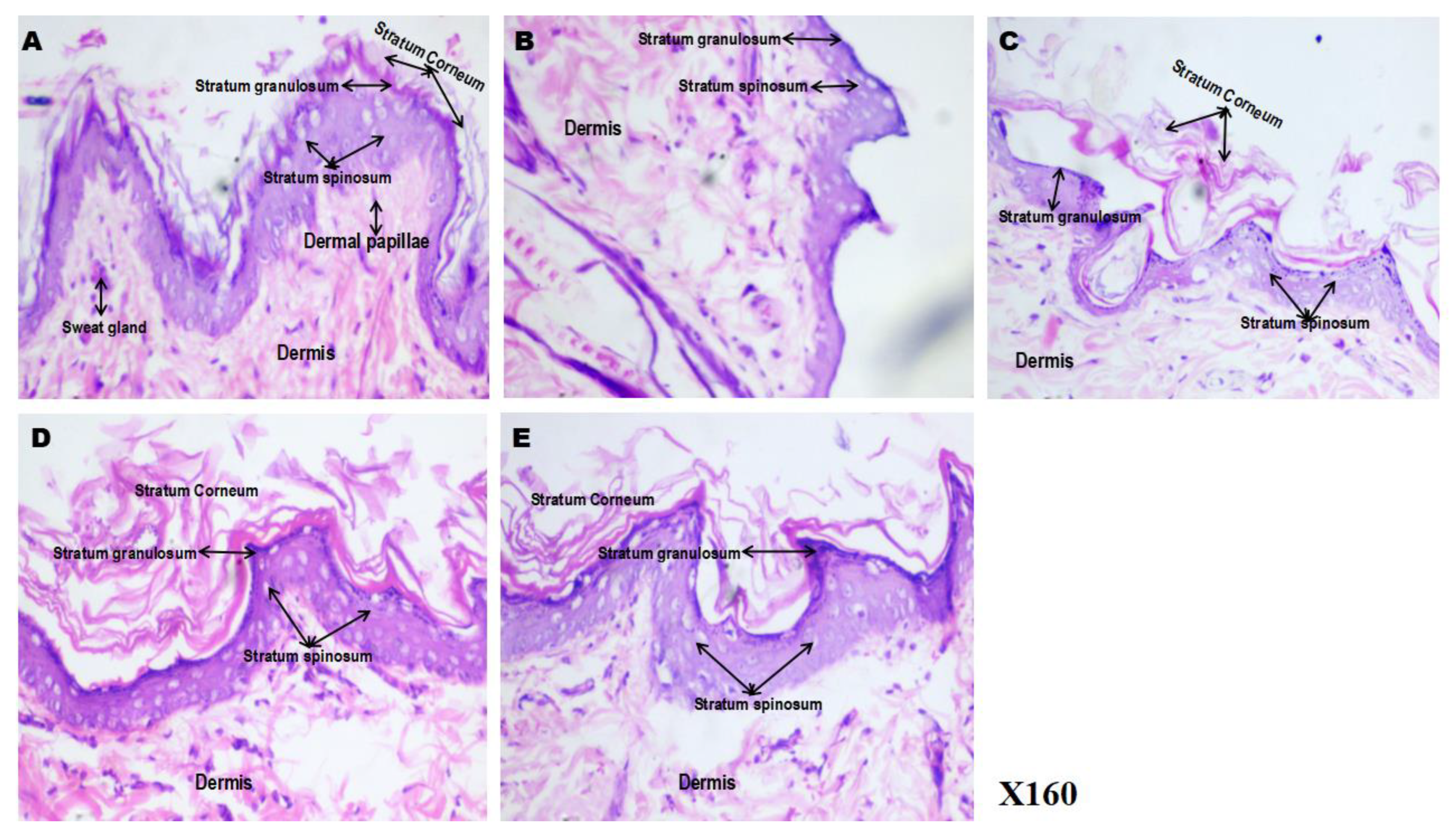

3.6. Effect of Phenytoin and Spironolactone on 5-Fluorouracil–Induced Histological Alterations in Rat Skin (Hematoxylin and Eosin Stain)

Figure 6(A-E) presents representative photomicrographs of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections of flank skin from control and -5FU treated groups, demonstrating the histoarchitectural changes induced by 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), and the modulatory effects of phenytoin and spironolactone. The control group (6A) exhibited well-preserved and clearly-defined skin architecture, characterised by an intact and compact stratum corneum, distinct stratum granulosum/stratum spinosum, prominent dermal papillae, sweat glands, and a well-organised dermis. In contrast, the 5-FU (6B) treated group showed marked degenerative alterations, including disintegration of the stratum corneum, loss of epidermal compactness, and disrupted dermal papillae, indicating significant cytotoxic and degenerative effects of 5-FU on the skin.

In the 5FU/PHE50 (6C) group, partial restoration of the epidermal layers was evident, with early regeneration of the stratum corneum, although the layers remained less compact than in controls. The 5FU/PHE100 (5D) group demonstrated notable recovery, showing a thickened and compact stratum corneum, well-defined epidermal strata, and reappearance of organized dermal papillae closely resembling the control morphology. These findings suggest a dose-dependent protective and restorative effect of phenytoin on 5-FU–induced skin injury. Similarly, the 5FU/SPIRO (6E) group showed improved epidermal organisation and regeneration of the stratum corneum relative to 5-FU alone, indicating a mild but distinct protective effect of spironolactone on skin histology.

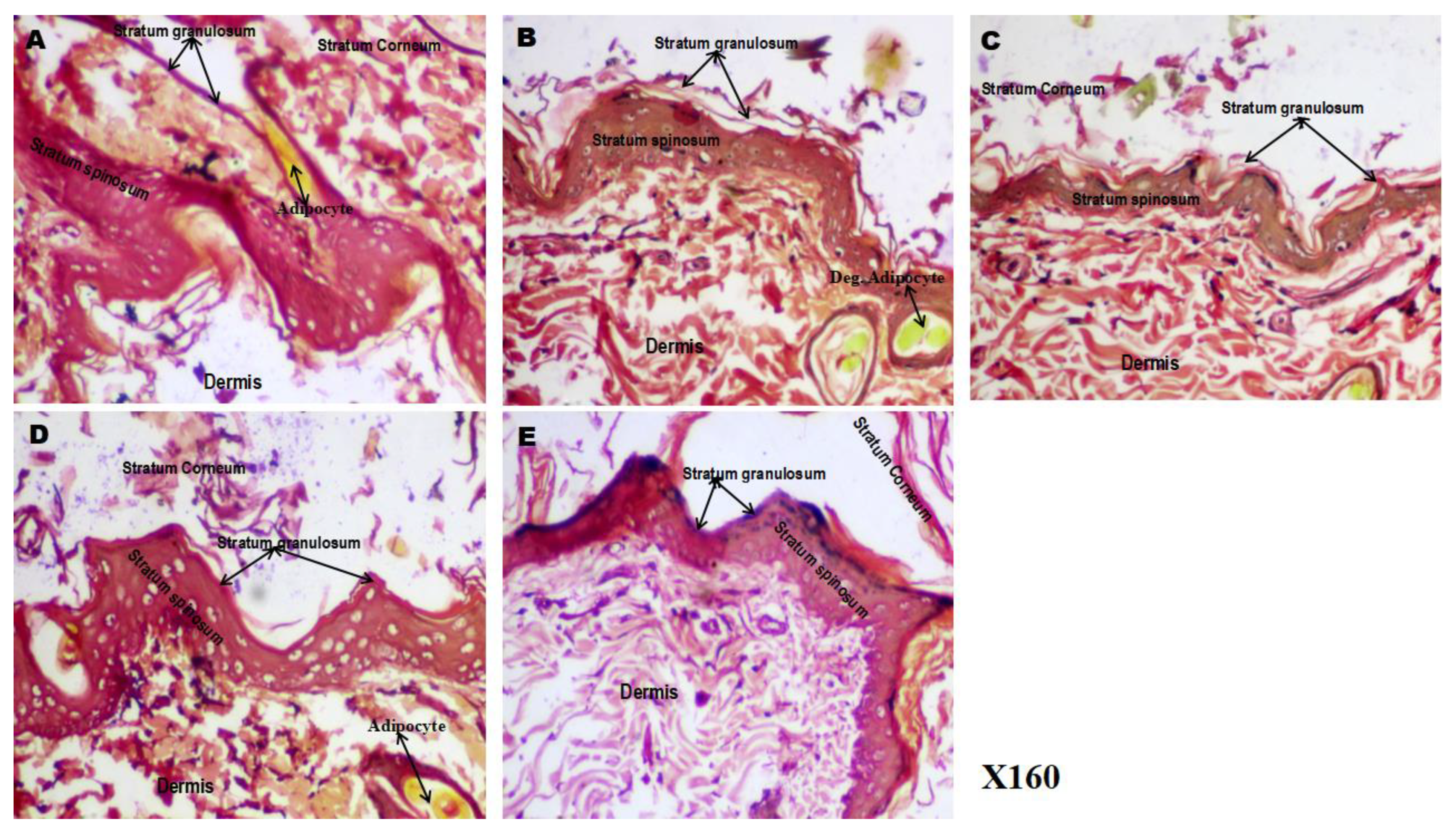

3.7. Effect of Phenytoin and Spironolactone on 5-Fluorouracil–Induced Alterations in Dermal Connective Tissue (Van Gieson’s Stain)

Figure 7 (A–E) presents representative photomicrographs of skin sections stained with Van Gieson’s stain, showing the distribution and integrity of collagen fibers (red) and adipocytes (yellow) in the control and treated groups. In the

control group (7A), skin sections revealed abundant, densely-packed collagen fibres interspersed with numerous adipocytes within the dermal layer, indicating normal connective tissue integrity. In contrast, the

5-FU-treated group (7B) exhibited a marked reduction in collagen fibre density and disorganisation of dermal connective tissue, along with decreased adipocyte content, reflecting the degenerative effects of 5-fluorouracil on the extracellular matrix and dermal structure.

The 5FU/PHE50 group (7C) showed faintly-regenerating collagen fibers with partial restoration of dermal organisation, suggesting early recovery of connective tissue architecture. In the 5FU/PHE100 group (7D), the collagen network appeared denser and more-compact, with the presence of well-defined adipocytes and connective tissue patterns resembling those of the control group, indicating a dose-dependent improvement in skin matrix restoration. Interestingly, the 5FU/SPIRO group (7E) demonstrated the most prominent regenerative response, characterised by abundant and distinctly-stained collagen fibres and adipocytes, comparable to the control group. This suggests that spironolactone produced a more substantial improvement in dermal connective tissue quality than phenytoin at either dose.

3.8. Effect of Phenytoin and Spironolactone on Hair Follicle Histology in 5-Fluorouracil-Treated Rats (Haematoxylin & Eosin Stain)

Figure 8 (A-E) shows representative photomicrographs illustrating the effect of phenytoin and spironolactone on the histology of hair follicles in 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)–treated rats. The

control group (8A) exhibited well-organised and prominent hair follicles with clearly-defined dermal papillae and well-differentiated dermal cells, reflecting normal follicular histoarchitecture. In contrast, the

5-FU group (8B) showed shortened, distorted hair follicles with poorly-differentiated dermal cells, suggesting a marked degenerative effect of 5-FU on follicular integrity (

p < 0.05 vs. control). Compared to the 5-FU group, the

5FU/PHE50 group (8C) demonstrated gradual follicular regeneration and elongation, indicative of partial restoration of follicular architecture and a mild protective effect of low-dose phenytoin. The

5FU/PHE100 group (8D) showed well-defined, elongated hair follicles with highly-differentiated dermal cells, comparable to those in the control group (

p < 0.05 vs. 5-FU). This suggests that higher-dose phenytoin provided a more pronounced restoration of hair follicle structure and improved dermal cell organisation. Similarly, the

5FU/SPIRO group (8E) exhibited the presence of distinct hair follicles, though dermal cell differentiation remained suboptimal compared to the 5FU/PHE100 group, suggesting a moderate restorative influence of spironolactone on follicular histology.

3.9. Effect of Phenytoin and Spironolactone on Hair Follicle Connective Tissue Histology (Von Gieson’s Stain)

Figure 9 illustrates the effect of phenytoin and spironolactone on the connective tissue components of hair follicles in 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)–treated rats, as shown by Von Gieson’s staining. The control group (9A) exhibited abundant and well-organised collagen fibers (appearing as red-stained regions) and numerous fat cells/adipocytes (yellow-stained areas), indicating normal connective tissue integrity within the dermis and around the hair papillae. In contrast, the 5-FU group (9B) showed a marked reduction in the density and quality of collagen fibres, along with a notable loss of adipocytes, suggesting chemotherapy-induced degeneration of the dermal connective tissue and extracellular matrix. Compared to the 5-FU group, the 5FU/PHE50 group (9C) displayed partial restoration of connective tissue integrity, with regenerating adipocytes visible around the dermal cells and hair papillae, indicating early repair activity. The 5FU/PHE100 group (9D) demonstrated more extensive regeneration, with clearly defined collagen fibers and abundant adipocytes, resembling the pattern observed in the control group. This reflects a dose-dependent protective and restorative effect of phenytoin on dermal connective tissue. The 5FU/SPIRO group (9E) also showed mild regeneration of collagen fibers and adipocytes compared to the 5-FU group, indicating a modest reparative effect of spironolactone on dermal structure.

3.10. Effect of Phenytoin and Spironolactone on 5-Fluorouracil–Induced Structural Alteration in the Hair Shaft

Figure 10 demonstrates the microstructural integrity of hair shafts from rats across experimental groups. Distinct hair shaft layers including the

external root sheath,

internal root sheath,

cortex, and

cuticle were visible. In the

control group (10A), the hair shafts exhibited well-organised layers with clearly-defined external and internal root sheaths, a dense cortex, and an intact cuticle. The structural arrangement indicates normal keratinization and shaft integrity. In contrast, the

5-FU group (10 B) showed a markedly-disrupted architecture. The hair shafts display irregular or fragmented cuticle layers and poorly-defined internal structures, consistent with

chemotherapy-induced dystrophy and

keratin damage. Compared to 5-FU, the

5FU/PHE50 group (10 C) exhibits partial recovery of the cortical and cuticular structures, though the cortex remained less compact and the sheath boundaries appeared faint, suggesting

moderate structural repair. The

5FU/PHE100 group (10 D) shows a more-organised shaft morphology, with distinct external and internal root sheaths, a dense cortex, and a continuous cuticle layer. This reflects

substantial restoration of hair shaft integrity, likely mediated by phenytoin’s stimulatory effects on keratinocyte activity and follicular repair. The

5FU/SPIRO group (10 E) displays mild improvement in the continuity of the cuticle, though less-pronounced than in the phenytoin-treated groups, suggesting

limited structural protection compared to higher-dose phenytoin.

3.11. Quantitative Morphometric Analysis of Hair Strands

Morphometric evaluation of hair shafts revealed distinct differences in structural parameters across experimental groups (

Table 1). Quantitative analysis showed that

5-fluorouracil (5-FU) administration significantly reduced mean hair shaft diameter, cortical width, and medullary width compared to the control group (

p < 0.05), reflecting marked structural degeneration and follicular atrophy. In contrast, co-administration of

phenytoin resulted in a dose-dependent improvement in hair strand morphology. The

5FU/PHE50 group exhibited partial restoration in mean shaft diameter and cortical compactness, while the

5FU/PHE100 group demonstrated values approaching those of the control, with a significant increase in shaft thickness and cortex-to-medulla ratio compared to the 5-FU group (

p < 0.05). Similarly, colour intensity analysis from Image J revealed that 5-FU–treated rats displayed a reduction in mean pixel density, indicative of diminished pigmentation and keratin content. Treatment with phenytoin (particularly at 100 mg/kg) markedly enhanced colour intensity, suggesting increased melanin deposition and improved follicular metabolism. The

5FU/SPIRO group also showed moderate improvement in shaft diameter and pigment density, though these changes were less-pronounced than those seen in the high-dose phenytoin group. Collectively, these morphometric findings confirmed that

phenytoin mitigated 5-FU–induced hair shaft degeneration by restoring follicular architecture, enhancing keratin organisation, and improving pigmentation; consistent with the microscopic evidence.

Discussion

In this study, a rodent model of chemotherapy-induced alopecia was employed to evaluate the potential mitigating effects of oral phenytoin or spironolactone on 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)–induced hair loss, oxidative stress, and systemic physiological changes. The results demonstrated that oral administration of phenytoin or spironolactone significantly attenuated 5-FU–induced body-weight loss, increased feed intake, reduced lipid peroxidation, improved hair follicle morphology, and enhanced hair regrowth rate compared with the 5-FU-treated group.

In this study, the administration of 5-FU was associated with reduced feed intake and weight loss that worsened with progression of study, which is consistent with the result of previous studies (Bakar et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2021; Olofinnade et al., 2025). This effect observed with 5-FU is also synonymous with the effects of other antineoplastic agents including cyclophosphamide and methotrexate (Onaolapo et al., 2018b, 2023; Olofinnade et al., 2024; Dosunmu et al., 2025). The changes in feed intake and body weight associated with the administration of 5-FU and other cancer chemotherapeutic agents reflect systemic toxicity and reduced appetite, most-likely arising from gastrointestinal irritation and metabolic disruption (Astuti et al., 2025). The administration of phenytoin or spironolactone was associated with the reversal of 5-FU induced decrease in feed intake and reduction in body weight. The attenuation of 5-FU–induced growth suppression observed in this study suggests that both phenytoin and spironolactone may mitigate the systemic toxicity associated with chemotherapy. These protective effects appear to involve mechanisms that reduce oxidative stress, support tissue recovery, and promote overall physiological stability; which were also observed in this study. Phenytoin or spironolactone’s ability to improve feed intake, weight gain, and general activity would indicate possible recovery of appetite and metabolic function. Evidence from this study would suggest that the restorative effects observed with phenytoin and spironolactone can be attributed to the anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and cytoprotective properties of both agents, which resulted in enhanced tissue repair and systemic resilience. However, existing literature has shown that phenytoin has restorative properties for wounds due to its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and cytoprotective effects, promoting tissue repair (Sheir et al., 2022; Sadiq et al., 2024), spironolactone on the other hand is a diuretic and hormone antagonist whose ability to restore hair growth has been attributed to its antiandrogen effects It is believed that while both can have positive effects on tissue repair, they possibly do so through different mechanism. Collectively, the findings suggest that phenytoin and spironolactone possess potential therapeutic value in ameliorating chemotherapy-induced side-effects such as growth suppression, and oxidative injury, thereby improving post-treatment recovery and quality of life.

In this study, administration of 5-FU resulted in visible chemotherapy-induced alopecia characterised by delayed and incomplete hair regrowth, while treatment with phenytoin or spironolactone significantly improved regrowth outcomes, with spironolactone showing the greatest protective and restorative effect. These findings suggest that both agents, particularly spironolactone, may mitigate 5-FU–induced follicular damage through mechanisms involving reduced oxidative stress, inflammation, and enhanced collagen synthesis. This supports previous reports of spironolactone ability to reverse chemotherapy induced alopecia (Saleh et al., 2025). Histological sections revealed dystrophic changes, including dermal papilla distortion, follicular shrinkage, and a marked reduction in the number of anagen-phase follicles. These findings are consistent with prior reports that 5-FU disrupts matrix keratinocyte proliferation, leading to premature catagen entry and telogen shedding (Rorex et al., 2019). Phenytoin administration significantly reversed these changes. Follicles in phenytoin-treated rats displayed restored anagen morphology, thicker hair shafts, and improved cortex and medulla integrity compared with the 5-FU-only group. The increased number of active follicles per field supports the notion that phenytoin promotes follicular regeneration. These results suggest that systemic exposure to phenytoin may recapitulate its known hypertrichotic side-effect through enhanced fibroblast proliferation, angiogenesis, and growth factor expression, similar to report of previous studies (Onaolapo et al., 2018a; Sugiarto et al., 2022). In this study spironolactone also mitigated 5-FU–induced follicular injury, although current evidence is limited, there have been suggestions that spironolactone could be a viable option in the management of persistent hair loss after cancer therapy (Saleh et al., 2025).

Chemotherapy-induced alopecia has been mechanistically linked to oxidative injury within follicular keratinocytes. In the present study, 5-FU administration caused a significant rise in plasma malondialdehyde (MDA) concentrations, confirming lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress. Phenytoin and spironolactone significantly reduced these levels, indicating a protective antioxidant effect. A similar pattern was observed in cytokine expression: 5-FU elevated pro-inflammatory markers TNF-α and IL-1β while reducing anti-inflammatory IL-10. Phenytoin markedly attenuated TNF-α and IL-1β levels, while restoring IL-10 to near-baseline values, suggesting modulation of cytokine balance. These findings agree with reports of phenytoin’s anti-inflammatory and membrane-stabilising actions in wound healing and neural tissue repair (Onaolapo et al., 2018a).

Conclusion

This study showed that phenytoin and spironolactone significantly reduced the toxic effects of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) in rats, improving body weight, feed intake, and hair regrowth, while lowering oxidative stress and inflammation. Both drugs restored normal hair follicle structure and promoted tissue recovery. Phenytoin’s effects were linked to its antioxidant and tissue-repair properties, whereas spironolactone’s benefits likely arose from its anti-inflammatory actions. Together, the findings indicate that these agents may serve as potential protective therapies against chemotherapy-induced hair loss and systemic toxicity, enhancing post-treatment recovery and overall well-being.

Availability of data and materials

Data generated during and analysed during the course of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Declaration of ethical approval

Ethical approval for the research was granted by the Ethical Committee of Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, LAUTECH

Competing interests

All authors of this paper declare that there is no conflict of interest related to the content of this manuscript.

References

- Aleissa, M. The Efficacy and Safety of Oral Spironolactone in the Treatment of Female Pattern Hair Loss: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cureus. 2023, 15, e43559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinsehinwa, A.F.; Samson, P.O.; Onaolapo, O.J.; Onaolapo, A.Y. Quercetin/Donepezil co-administration mitigates Aluminium chloride induced changes in open field novelty induced behaviours and cerebral cortex histomorphology in rats. Acta Bioscienctia 2025, 1, 01–07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajao, J.A.; Akinsehinwa, A.F.; Onaolapo, O.J.; Onaolapo, A.Y. Alcohol Extract of Muira Puama (Ptychopetalum Olacoides) ameliorates Aluminium Chloride-induced changes in Behaviour and Cerebral cortex Histomorphology in Wistar Rats. Acta Bioscienctia 2025, 1, 022–029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astuti, A.K.; Samsul Louisa, M.; Wimardhani, Y.S.; Yasmon, A.; Wuyung, P.E. Clinical and histopathological evaluation of 5-fluorouracil-induced oral mucositis in a rat model. Open Vet J. 2025, 15, 1958–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, A.; Ningrum, V.; Lee, S.-C.; Li, C.-T.; Hsieh, C.-W.; Wang, S.-H.; Tsai, M.-S. Therapeutic Effect of Cinnamomum osmophloeum Leaf Extract on Oral Mucositis Model Rats Induced by 5-Fluororacil via Influencing IL-1β and IL-6 Levels. Processes. 2021, 9, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, L.J.; De Souza, B.; Flynn, E.; Hagigeorges, D.; Senna, M.M. Spironolactone for treatment of female pattern hair loss. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020, 83, 276–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.J.; Chen, Y.L.; Ueng, S.H.; Hwang, T.L.; Kuo, L.M.; Hsieh, P.W. Neutrophil elastase inhibitor (MPH-966) improves intestinal mucosal damage and gut microbiota in a mouse model of 5-fluorouracil-induced intestinal mucositis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021, 134, 111152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosunmu DP, Ojo FO, Onaolapo AY, Onaolapo OJ Cholecalciferol Ameliorates Cyclophosphamide-induced Behavioural Toxicities in Wistar Rats bioRxiv 2025.09.11.675651. [CrossRef]

- Fattahi, N.; Abdolahi, A.; Vahabzadeh, Z.; Nikkhoo, B.; Manoochehri, F.; Goudarzzadeh, S.; Hassanzadeh, K.; Izadpanah, E.; Moloudi, M.R. Topical phenytoin administration accelerates the healing of acetic acid-induced colitis in rats: evaluation of transforming growth factor-beta, platelet-derived growth factor, and vascular endothelial growth factor. Inflammopharmacology. 2022, 30, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafouri-Fard, S.; Abak, A.; Tondro Anamag, F.; Shoorei, H.; Fattahi, F.; Javadinia, S.A.; Basiri, A.; Taheri, M. 5-Fluorouracil: A Narrative Review on the Role of Regulatory Mechanisms in Driving Resistance to This Chemotherapeutic Agent. Front Oncol. 2021, 11, 658636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, J.F.; Jamerson, T.A.; Aguh, C. Efficacy and safety profile of oral spironolactone use for androgenic alopecia: A systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022, 86, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.I.; Choi, Y.K.; Han, S.C.; Hyun, J.W.; Koh, Y.S.; Oh, J.; Boo, H.J.; Yoo, E.S.; Kang, H.K. 5-Fluorouracil induces hair loss by inhibiting β-catenin signaling and angiogenesis. Chem Biol Interact. 2025, 408, 111416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, L.; Valentic, L.; Moulton, H.; Rose, L.; Dulmage, B. Cancer-Related Alopecia Risk and Treatment. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2025, 26, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keppel Hesselink, J.M. Phenytoin repositioned in wound healing: clinical experience spanning 60 years. Drug Discov Today. 2018, 23, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller Ramos, P.; Melo, D.F.; Radwanski, H.; de Almeida, R.F.C.; Miot, H.A. Female-pattern hair loss: therapeutic update. An Bras Dermatol. 2023, 98, 506–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazıroğlu, M.; Yürekli, V.A. Effects of antiepileptic drugs on antioxidant and oxidant molecular pathways: focus on trace elements. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2013, 33, 589–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozawa, K.; Toma, S.; Shimizu, C. Distress and impacts on daily life from appearance changes due to cancer treatment: A survey of 1,034 patients in Japan. Glob Health Med. 2023, 5, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofinnade, A.T.; Ajao, J.A.; Akinsehinwa, A.F.; Onaolapo, O.J.; Onaolapo, A.Y. Human-dose equivalent 5-fluorouracil triggers a pathophysiological cascade of neuroinflammation, cortical remodeling, and behavioural disruption in Wistar rats. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofinnade, A.T.; Ajifolawe, O.B.; Onaolapo, O.J.; Onaolapo, A.Y. Dry-feed Added Quercetin Mitigates Cyclophosphamide-induced Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Gonadal Fibrosis in Adult Male Rats. Antiinflamm Antiallergy Agents Med Chem. 2025, 24, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofinnade, A.T.; Ajifolawe, O.B.; Onaolapo, O.J.; Onaolapo, A.Y. Dry-feed Added Quercetin Mitigates Cyclophosphamide-induced Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Gonadal Fibrosis in Adult Male Rats. Antiinflamm Antiallergy Agents Med Chem. 2025, 24, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofinnade, A.T.; Onaolapo, A.Y.; Okunola, O.B.; Onaolapo, O.J. Zinc Gluconate Supplementation Protects against Methotrexate-induced Neurotoxicity in Rats via Downregulation of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Neuron-specific Enolase Reactivity in Rats. Current Biotechnology 2024, 13, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofinnade, A.T.; Onaolapo, A.Y.; Onaolapo, O.J.; Olowe, O.A. The potential toxicity of food-added sodium benzoate in mice is concentration-dependent. Toxicol Res (Camb). 2021, 10, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olofinnade, A.T.; Ajao, J.A.; Akinsehinwa, A.F.; Onaolapo, O.J.; Onaolapo, A.Y. Human-dose equivalent 5-fluorouracil triggers a pathophysiological cascade of neuroinflammation, cortical remodeling, and behavioural disruption in Wistar rats bioRxiv 2025.09.15.676357. [CrossRef]

- Onaolapo, A.Y.; Abdusalam, S.Z.; Onaolapo, O.J. Silymarin attenuates aspartame-induced variation in mouse behaviour, cerebrocortical morphology and oxidative stress markers. Pathophysiology. 2017, 24, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onaolapo, A.Y.; Adebayo, A.A.; Onaolapo, O.J. Oral phenytoin protects against experimental cyclophosphamide-chemotherapy induced hair loss. Pathophysiology. 2018, 25, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onaolapo, A.Y.; Ojo, F.O.; Onaolapo, O.J. Biflavonoid quercetin protects against cyclophosphamide-induced organ toxicities via modulation of inflammatory cytokines, brain neurotransmitters, and astrocyte immunoreactivity. Food Chem Toxicol. 2023, 178, 113879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onaolapo, A.Y.; Ojo, F.O.; Onaolapo, O.J. Biflavonoid quercetin protects against cyclophosphamide-induced organ toxicities via modulation of inflammatory cytokines, brain neurotransmitters, and astrocyte immunoreactivity. Food Chem Toxicol. 2023, 178, 113879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onaolapo, A.Y.; Oladipo, B.P.; Onaolapo, O.J. Cyclophosphamide-induced male subfertility in mice: An assessment of the potential benefits of Maca supplement. Andrologia. 2018, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, Y.; Öztürk, M.; Dörtbudak, M.B.; Mariotti, F.; Magi, G.E.; Di Cerbo, A. Astaxanthin Mitigates 5-Fluorouracil-Induced Hepatotoxicity and Oxidative Stress in Male Rats. Nutrients. 2025, 17, 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, K.O.; Shivakumar, Y.M.; Burra, E.K.; Shahid, K.; Tamene, Y.T.; Mody, S.P.; Nath, T.S. Topical phenytoin improves wound healing with analgesic and antibacterial properties and minimal side effects: a systematic review. Wounds. 2024, 36, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, D.; Nassereddin, A.; Saleh, H.M.; et al. Anagen Effluvium. [Updated 2024 Apr 30]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482293.

- Saraswat, N.; Chopra, A.; Sood, A.; Kamboj, P.; Kumar, S. A Descriptive Study to Analyze Chemotherapy-Induced Hair Loss and its Psychosocial Impact in Adults: Our Experience from a Tertiary Care Hospital. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2019, 10, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheir, M.M.; Nasra, M.M.A.; Abdallah, O.Y. Phenytoin-loaded bioactive nanoparticles for the treatment of diabetic pressure ulcers: formulation and in vitro/in vivo evaluation. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2022, 12, 2936–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheir, M.M.; Nasra, M.M.A.; Abdallah, O.Y. Phenytoin-loaded bioactive nanoparticles for the treatment of diabetic pressure ulcers: formulation and in vitro/in vivo evaluation. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2022, 12, 2936–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.H.; Hou, R.; Hsieh, T.S.; Plikus, M.V.; Lin, S.J. Studying Hair Growth in Mice: Synchronization of Hair Follicle Growth by Depilation. Methods Mol Biol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Du, Y.; Bi, L.; Lin, X.; Zhao, M.; Fan, W. The Efficacy and Safety of Oral and Topical Spironolactone in Androgenetic Alopecia Treatment: A Systematic Review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2023, 16, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikramanayake, T.C.; Haberland, N.I.; Akhundlu, A.; Laboy Nieves, A.; Miteva, M. Prevention and Treatment of Chemotherapy-Induced Alopecia: What Is Available and What Is Coming? Curr Oncol. 2023, 30, 3609–3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Effect of Phenytoin (PHE) or Spironolactone (Spiro) on body weight in 5-FU treated rats. Each line represents Mean ± S.E.M. Number of rats per treatment group= 8. 5-FU: 5-Fluorouracil, PHE: Phenytoin, SPIRO: Spironolactone.

Figure 1.

Effect of Phenytoin (PHE) or Spironolactone (Spiro) on body weight in 5-FU treated rats. Each line represents Mean ± S.E.M. Number of rats per treatment group= 8. 5-FU: 5-Fluorouracil, PHE: Phenytoin, SPIRO: Spironolactone.

Figure 2.

Effect of Phenytoin (PHE) or Spironolactone (Spiro) on feed intake in 5-FU treated rats. Each line represents Mean ± S.E.M. Number of rats per treatment group= 8. 5-FU: 5-Fluorouracil, PHE: Phenytoin, SPIRO: Spironolactone.

Figure 2.

Effect of Phenytoin (PHE) or Spironolactone (Spiro) on feed intake in 5-FU treated rats. Each line represents Mean ± S.E.M. Number of rats per treatment group= 8. 5-FU: 5-Fluorouracil, PHE: Phenytoin, SPIRO: Spironolactone.

Figure 3.

Photographic documentation of the effect of phenytoin on chemotherapy-induced alopecia in rats. A –control, B – 5-Fluorouracil at 50 mg/kg, C- Phenytoin at 50 mg/kg, D- Phenytoin at 100 mg/kg, E- Spironolactone at 20 mg/kg. Photographs were taken on days 0 (connoting the day prior the commencement of administration), 7, 14 and 21 respectively. Number of animals per group - 8.

Figure 3.

Photographic documentation of the effect of phenytoin on chemotherapy-induced alopecia in rats. A –control, B – 5-Fluorouracil at 50 mg/kg, C- Phenytoin at 50 mg/kg, D- Phenytoin at 100 mg/kg, E- Spironolactone at 20 mg/kg. Photographs were taken on days 0 (connoting the day prior the commencement of administration), 7, 14 and 21 respectively. Number of animals per group - 8.

Figure 4.

Each bar represents Mean ± S.E.M., *p<0.05 significant difference from control, #p<0.05 significant difference from 5FU, &p<0.05 significant difference from Spironolactone. Number of rats per treatment group = 8. 5-FU: 5-Fluorouracil, PHE: Phenytoin, SPIRO: Spironolactone.

Figure 4.

Each bar represents Mean ± S.E.M., *p<0.05 significant difference from control, #p<0.05 significant difference from 5FU, &p<0.05 significant difference from Spironolactone. Number of rats per treatment group = 8. 5-FU: 5-Fluorouracil, PHE: Phenytoin, SPIRO: Spironolactone.

Figure 5.

a: Each bar represents Mean ± S.E.M., *p<0.05 significant difference from control, #p<0.05 significant difference from 5FU, &p<0.05 significant difference from Spironolactone. Number of rats per treatment group = 8. 5-FU: 5-Fluorouracil, PHE: Phenytoin, SPIRO: Spironolactone.

Figure 5.

a: Each bar represents Mean ± S.E.M., *p<0.05 significant difference from control, #p<0.05 significant difference from 5FU, &p<0.05 significant difference from Spironolactone. Number of rats per treatment group = 8. 5-FU: 5-Fluorouracil, PHE: Phenytoin, SPIRO: Spironolactone.

Figure 5.

b: Each bar represents Mean ± S.E.M., *p<0.05 significant difference from control, #p<0.05 significant difference from 5FU, &p<0.05 significant difference from Spironolactone. Number of rats per treatment group = 8. 5-FU: 5-Fluorouracil, PHE: Phenytoin, SPIRO: Spironolactone.

Figure 5.

b: Each bar represents Mean ± S.E.M., *p<0.05 significant difference from control, #p<0.05 significant difference from 5FU, &p<0.05 significant difference from Spironolactone. Number of rats per treatment group = 8. 5-FU: 5-Fluorouracil, PHE: Phenytoin, SPIRO: Spironolactone.

Figure 6.

A-E): Effect of phenytoin and spironolactone on 5-fluorouracil–induced histological alterations in rat skin (Hematoxylin and Eosin staining). A – control, B – 5-Fluorouracil at 50 mg/kg, C- Phenytoin at 50 mg/kg, D- Phenytoin at 100 mg/kg, E- Spironolactone at 20 mg/kg. It shows prominent features such as the stratum corneum, stratum granulosum, stratum spinosum, dermal papillae and the sweat glands. Number of animals per group-8.

Figure 6.

A-E): Effect of phenytoin and spironolactone on 5-fluorouracil–induced histological alterations in rat skin (Hematoxylin and Eosin staining). A – control, B – 5-Fluorouracil at 50 mg/kg, C- Phenytoin at 50 mg/kg, D- Phenytoin at 100 mg/kg, E- Spironolactone at 20 mg/kg. It shows prominent features such as the stratum corneum, stratum granulosum, stratum spinosum, dermal papillae and the sweat glands. Number of animals per group-8.

Figure 7.

A-E): Effect of phenytoin and spironolactone on 5-fluorouracil–induced alterations in dermal connective tissue (Van Gieson’s staining). A – control, B – 5-Fluorouracil at 50 mg/kg, C- Phenytoin at 50 mg/kg, D- Phenytoin at 100 mg/kg, E- Spironolactone at 20 mg/kg It shows differentiation between collagen (red) and other connective tissues such as fat cells (yellow). Number of animals per group-8.

Figure 7.

A-E): Effect of phenytoin and spironolactone on 5-fluorouracil–induced alterations in dermal connective tissue (Van Gieson’s staining). A – control, B – 5-Fluorouracil at 50 mg/kg, C- Phenytoin at 50 mg/kg, D- Phenytoin at 100 mg/kg, E- Spironolactone at 20 mg/kg It shows differentiation between collagen (red) and other connective tissues such as fat cells (yellow). Number of animals per group-8.

Figure 8.

(A-E): Effect of phenytoin and spironolactone on hair follicle histology in 5-fluorouracil-treated rats (Haematoxylin & Eosin staining). A – control, B – 5-Fluorouracil at 50 mg/kg, C- Phenytoin at 50 mg/kg, D- Phenytoin at 100 mg/kg, E- Spironolactone at 20 mg/kg. It shows prominent features such as the hair follicle, papillae, dermal cells. Number of animals per group-8.

Figure 8.

(A-E): Effect of phenytoin and spironolactone on hair follicle histology in 5-fluorouracil-treated rats (Haematoxylin & Eosin staining). A – control, B – 5-Fluorouracil at 50 mg/kg, C- Phenytoin at 50 mg/kg, D- Phenytoin at 100 mg/kg, E- Spironolactone at 20 mg/kg. It shows prominent features such as the hair follicle, papillae, dermal cells. Number of animals per group-8.

Figure 9.

(A-E): Effect of phenytoin and spironolactone on hair follicle connective tissue histology in 5-fluorouracil-treated rats (Von Gieson’s staining). A – control, B – 5-Fluorouracil at 50 mg/kg, C- Phenytoin at 50 mg/kg, D- Phenytoin at 100 mg/kg, E- Spironolactone at 20 mg/kg. It shows differentiation between collagen (red) and other connective tissues such as fat cells (yellow). Number of animals per group-8.

Figure 9.

(A-E): Effect of phenytoin and spironolactone on hair follicle connective tissue histology in 5-fluorouracil-treated rats (Von Gieson’s staining). A – control, B – 5-Fluorouracil at 50 mg/kg, C- Phenytoin at 50 mg/kg, D- Phenytoin at 100 mg/kg, E- Spironolactone at 20 mg/kg. It shows differentiation between collagen (red) and other connective tissues such as fat cells (yellow). Number of animals per group-8.

Figure 10.

Effect of phenytoin and spironolactone on 5-fluorouracil–induced structural alteration in the Hair shaft. A – control, B − 5-Fluororacil at 50 mg/kg, C - 5-Fluororacil at 50 mg/kg and Phenytoin at 50 mg/kg, D - 5-Fluororacil at 50 mg/kg and Phenytoin at 100 mg/kg, E - 5-Fluororacil at 50 mg/kg and Spironolactone at 20 mg/kg. Number of animals per group-8.

Figure 10.

Effect of phenytoin and spironolactone on 5-fluorouracil–induced structural alteration in the Hair shaft. A – control, B − 5-Fluororacil at 50 mg/kg, C - 5-Fluororacil at 50 mg/kg and Phenytoin at 50 mg/kg, D - 5-Fluororacil at 50 mg/kg and Phenytoin at 100 mg/kg, E - 5-Fluororacil at 50 mg/kg and Spironolactone at 20 mg/kg. Number of animals per group-8.

Table 1.

Morphometric Parameters of Hair Shafts in Different Experimental Groups.

Table 1.

Morphometric Parameters of Hair Shafts in Different Experimental Groups.

| Parameter |

Control |

5-FU |

5FU + Phenytoin 50 mg/kg |

5FU + Phenytoin 100 mg/kg |

5FU + Spironolactone |

| Mean Shaft Diameter (µm) |

70.2 ± 4.42 |

36.2 ± 3.40*

|

45.6 ± 4.20*#

|

65.4 ± 3.93*#

|

60.3 ± 3.96*#

|

| Cortical Width (µm) |

39.2 ± 2.10 |

18.5 ± 1.70*

|

28.6 ± 2.31*#

|

29.9 ± 2.01*#

|

26.1 ± 2.42*#

|

| Medullary Width (µm) |

22.1 ± 1.81 |

10.2 ± 1.12*

|

15.8 ± 1.52*#

|

22.3 ± 1.62*#

|

18.1 ± 1.25*#

|

| Cortex-to-Medulla Ratio |

1.8 ± 0.11 |

1.2 ± 0.10*

|

1.5 ± 0.12*#

|

1.8 ± 0.11*#

|

1.6 ± 0.11*#

|

| Mean Colour Intensity (A.U.) |

156.7 ± 5.31 |

90.4 ± 4.72* |

121.8 ± 3.43*#

|

142.6 ± 4.61*#

|

130.2 ± 4.81*#

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).