1. Introduction: The Academic Response to Energy Poverty Alleviation

Energy transition mandates equal access to affordable and sustainable energy. However, reliable energy access is hindered by geopolitical crises and persistent climate change, which result in high energy costs, especially in cases of strong reliance on traditional fuels and weak related policies. Energy equity disproportionately affects low-income households and marginalised communities by limiting their access to affordable, reliable, and sustainable energy, thereby exacerbating social and economic inequalities and hindering their overall quality of life and opportunities for development. This is also highlighted in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly in SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) and SDG 1 (No Poverty), as well as SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), which emphasises the need to reduce disparities within and among countries. Ensuring equitable access to clean and affordable energy plays a crucial role in alleviating poverty and addressing social and economic inequalities, especially for marginalised and vulnerable communities.

Energy poverty alleviation is a complex socio-economic issue that, over the last decade, has garnered vast attention both across Europe and the World. Overall, and despite some minor variations in the definition from country to country, energy poverty is commonly perceived as the inability of individuals or households to afford adequate heating during winter or cooling during summer. At the quest of measuring the extent and intensity of energy poverty as well as its implications, several indicators have been developed, with the most predominant being the 10% rule-indicator, which describes the state of a household as energy poor if it spends more than 10% of its annual income on energy bills [

1]. Nevertheless, energy poverty is a multifaceted problem, making its alleviation challenging to both comprehend and address. The inability to access or afford essential energy services, such as electricity, heating, and clean cooking facilities, has a significant impact on the quality of life, economic opportunities, and health of those affected. A notable initiative addressing this issue is the WELLBASED project, which developed and implemented urban interventions across six pilot sites with aim of mitigating energy poverty. The project’s objective was to promote the adoption of integrated programmes that address energy poverty, with a specific emphasis on health as a cross-cutting concern [

2].

Energy poverty is most prevalent in low-income households and rural areas of developing countries, energy poverty perpetuates cycles of poverty and inequality. For instance, households without electricity often rely on biomass for cooking and heating, such as wood or charcoal, which is initially an inefficient source. Moreover, and most importantly, heating only with biomass may cause respiratory problems that disproportionately affect women and children [

3]. However, it is worth noting that energy poverty affects a significant number of people across different income bands on a global scale. This can be proved by looking back at EU statistics [

4] of 2023, show that approximately 40 million Europeans across all Member States representing 9.3% of the Union population were unable to keep their home adequately warm in 2022. That is a sharp increase since 2021 when 6,9% of the population were in the same situation.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) reported that the number of people in sub-Saharan Africa without access to modern energy increased by 4% from 2019 to 2021. This percentage is quite high considering that approximately 1.1 billion people in rural areas lacked access to electricity. Additionally, the electrification rate is at a significantly low level of 45%, whereas the corresponding rate in Asian countries is 94% [

5,

6]. The World Health Organisation (WHO) also reports that approximately 58% of health facilities in the sub-Saharan region lack electricity [

7].

Considering the large extent of energy poverty to population as well as its implications, as it does not only affect the quality of life but also poses a significant barrier to reaching the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), it is understood that immediate actions for eliminating poverty, reducing inequalities and safeguarding access to sustainable and clean energy must be made. According to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), the targets related to the SDGs may remain unrealised unless global electrification rates are improved. Unfortunately, a negative forecast with high probabilities indicates that 660 million people worldwide will lack access to electricity by 2030, underscoring the need to implement strategies for addressing electricity inaccessibility [

8].

Addressing energy poverty requires a comprehensive and multidimensional approach, as several interrelated factors can be identified as its causes: insufficient household income, high energy prices, poor dwelling quality, a lack of efficient and clean energy supply, and limited integration of Renewable Energy Sources (RES) and related technologies. It is essential to design an energy-efficient habitat (or to rehabilitate it for this purpose), both to combat the cold and the heat (and thus limit the energy requirement for thermal comfort. Improving the quality of dwellings and expanding sustainable energy infrastructure to underserved areas is critical to avoid environmental degradation. On that note, investment in RES, such as solar, wind, and hydropower, offers a dual benefit of providing clean energy and reducing emissions of greenhouse gas and anthropogenic gases harmful to health and the environment most sustainably. The share of primary energy from renewable energy sources was only slightly over 3% in 2024 for the region of South Africa, compared to 14.5% globally [

9]. Additionally, approximately to 82.1% of the electricity is produced by coal in South Africa while the rest of the word is at 34.2% [

10]. Access to clean fuels or technologies, such as clean cookstoves, reduces exposure to indoor air pollutants, which is a leading cause of death in low-income households [

11]. Therefore, policymakers are tasked with implementing strategies that ensure energy is affordable for all, possibly through subsidies or financial assistance programs for low-income households. As access to a reliable electricity supply is vital for achieving social and economic growth, as highlighted in SDG 7, which calls for universal access to modern, sustainable, accessible, and affordable energy by 2030, is mandatory [

3].

Electricity is indispensable at the household level, as it powers the majority of daytime activities, including essential functions such as cooking and cooling, as well as secondary uses like radio, television, and other domestic appliances. During nighttime hours, electricity remains critical for providing lighting, ensuring household security, and enabling the continuation of routine activities such as studying or remote work. Improving access to energy helps alleviate energy poverty and constitutes a crucial method of addressing energy poverty through international policy interventions [

12]. The main challenge lies in the fact that electricity prices are significantly high and often unaffordable for low-income households.

As previously mentioned, traditional energy sources such as wood and charcoal, which are non-modern and often used in unsustainable ways, are commonly relied upon to meet basic needs like cooking. Hence, fossil fuel pollution is constantly increasing due to the use of charcoal, wood, or other local fuels that cause long-term chronic respiratory and other diseases that are responsible for 1.5 million deaths per year in both mothers and children [

13]. In some countries, people use animal manure, which causes deaths in numerous infants due to the utilisation of contaminated fuels and cooking technologies. Considering the above standard practices applied to cover basic needs, together with the non-existent supply of electricity, it raises the difficulty for sub-Saharan Africa to meet the SDG goals by 2030 [

14,

15].

Knowledge-based barriers are equally important when examining energy transition pathways and policies. Appropriate knowledge of energy production and related technologies can empower households to manage their energy demands more effectively, improve their consumption patterns, and, to some extent, alleviate the burden of energy poverty. Of course, as in all fields, international cooperation and support are necessary. They should be guided by international organisations and experts who can play a significant role in facilitating knowledge exchange and best practices. For example, community-based initiatives involving local populations in planning and implementing energy projects tend to be more successful, as they are tailored to specific needs and circumstances.

Additionally, the recent economic crises in Europe have further stressed the energy poverty landscape. The COVID-19 pandemic and the Ukrainian–Russian war led to a constant increase in inflation, causing energy product prices to intensify energy poverty. Power purchases have also been affected by both crises. As proved by the latest statistics, the countries with the largest share of the population unable to keep their homes sufficiently warm in 2020 were Bulgaria (27%), Lithuania (23%), Cyprus (21%), Portugal and Greece at 17% [

16,

17]. The study by Carfora et al. showed that the adverse effects of the pandemic will revert at significantly low rates, not before 2025, with considerable differences between various European countries widening the gap between countries with low levels of energy poverty and those with higher energy poverty [

18]. To address this emerging issue, the European Union (EU) has initiated several policy initiatives and published two recommendations, EU/2020/1563 and EU/2023/2407, to guide standard definitions and measurements in this direction [

19].

Universities are at the forefront of understanding and addressing energy poverty, as they possess the human capital necessary to identify, design, and implement targeted solutions and initiatives that have proven to be the most efficient way to alleviate energy poverty. Additionally, by analysing the broader social, economic, and environmental impacts of energy poverty, they provide policymakers with comprehensive feedback to improve existing policies and measures at the governance level. For instance, economists and environmental scientists may collaborate to develop policies that strike a balance between economic growth and environmental sustainability. Public health experts might collaborate with engineers to design energy solutions that minimise health risks. Social justice advocates can partner with political scientists to push for equitable energy policies. Higher Education Institutes (HEIs) also play a critical role in the field of technological innovation. Both engineering and technology departments within universities are designed to study and develop new energy-efficient technologies and renewable energy solutions, such as advanced insulation materials and smart home systems, as well as community-based renewable energy projects that can reduce dependence on fossil fuels and lower energy costs. By fostering partnerships with industry and government, universities can accelerate the deployment of these technologies in real-world settings.

The contribution of the academic community to the eradication of energy poverty is evident in the ongoing transformation of academic programs in HEIs. These programs are increasingly introducing courses that, either directly or indirectly, address energy poverty and promote related technological solutions.

As is well known, education plays a crucial role in the energy transition, which involves shifting from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources and improving energy efficiency. Appropriate and targeted knowledge fosters awareness, deepens understanding, and helps develop a skilled workforce for emerging jobs. Most importantly, advances in research and innovation enable both the improvement of existing energy solutions, such as wind energy turbines, and increased efficiency, while also facilitating related investments. To better understand the role of education in addressing energy poverty, this work presents a short review of studies in various regions. These studies explore how educational initiatives contribute to raising awareness. By examining data from regions where relevant and reliable information is available, the analysis aims to uncover common patterns and region-specific insights into how education can catalyse the reduction of energy poverty. This approach helps identify effective strategies and underscores the importance of implementing educational interventions.

The study emphasises the importance of developing targeted academic curricula that bridge the gap between research and real-world applications, thereby equipping graduates with the expertise to implement sustainable energy solutions. Thus, in the context of the emerging issue of energy poverty alleviation and how the scientific community responds to that, this work aims to identify the various academic programs that exist at the postgraduate level of European HEIs. This research was conducted within the framework of the EU-funded project “MSc in Energy Poverty Alleviation Technologies”. The analysis offers valuable insights into the current landscape of postgraduate education in sustainable energy, highlighting the importance of aligning academic offerings with the practical needs of the sector. Providing a detailed record of existing postgraduate academic programs in energy poverty is essential for several compelling reasons, as aforementioned: by pursuing a postgraduate program in this field, students can contribute to finding sustainable solutions to provide affordable and reliable energy to underserved communities, thereby improving the quality of life and supporting economic development. Postgraduate programs, in addition, often include policy analysis and development components, enabling students to understand the regulatory and legislative frameworks that can drive change. The demand for experts in addressing energy poverty is growing as governments, international agencies, and private sector companies recognise the importance of tackling this issue.

In summary, researching academic programs related to energy poverty is essential for creating relevant, comprehensive, and impactful educational pathways. It ensures that these programs are grounded in the latest knowledge, technologies, and best practices, preparing graduates to effectively address the multifaceted challenges of energy poverty on a global scale. Finally, this study aims to propose a potential curriculum based on the findings and insights derived from the collected research data.

2. Methodology

Universities serve as vital hubs for knowledge generation and capacity building. Postgraduate programs are designed to prepare students for academic careers, research, international development, and consultancy. In addition, Universities can play an active role in promoting awareness of energy issues by participating in educational outreach, public engagement initiatives, and community-based programs. The specialised knowledge and skills gained can make graduates highly competitive in these fields. Energy poverty is an evolving field with many unanswered questions and areas for further research. Pursuing a postgraduate degree provides the opportunity to contribute original research, advancing the understanding of energy poverty and developing innovative solutions. Academic programs often provide access to cutting-edge research facilities and opportunities for collaboration with leading experts.

In this section, the European postgraduate programs in the wider field of energy poverty are presented. These include interdisciplinary fields such as engineering, economics, environmental science, public health, legislative issues, and social justice, to comprehensively address the broader nexus of energy poverty attributes. Therefore, the search was designed to include concepts such as sustainable and renewable energy, energy efficiency and conversion, building design and efficiency, energy access issues, and equally fair policies. The spatial and socio-economic aspects of energy poverty are present in many programs that have dedicated modules, such as energy access and poverty, energy justice, policies, sustainability in energy provision and demand management, corporate sustainability strategies and governance, or the social aspect of adult education for sustainable development, power politics and society, sustainability and governance, inequality and inclusive growth, etc. Additionally, the coursework often includes the study of renewable energy sources, energy efficiency measures, and the socio-economic implications of energy policies. In that context, students learn to analyse and design policies that promote energy equity, such as subsidies for energy-efficient home retrofits, regulations mandating improved energy performance standards, and community-based initiatives to support energy-vulnerable populations.

Additionally, these programs often provide practical experience through internships, fieldwork, and collaborations with governmental and non-governmental organisations, enabling students to apply theoretical knowledge to real-world contexts. As Europe strives to meet its sustainability targets and enhance social welfare, addressing energy poverty becomes increasingly apparent. The European Union’s Green Deal, along with various national policies, underscores a commitment to achieving energy justice, reducing carbon emissions, and ensuring that all citizens have access to affordable, reliable, and sustainable energy. Consequently, the demand for professionals trained in the complexities of energy poverty is rising. Graduates of these master’s programs are well-positioned to contribute to policymaking, research, advocacy, and implementation of solutions that mitigate energy poverty and promote a more equitable energy landscape.

Searching for master’s programs in energy poverty entails a systematic and multi-dimensional methodological approach aimed at ensuring the most comprehensive and analytically rigorous identification of relevant academic offerings. The first stage involves profiling universities based on their research output, institutional commitments, and academic strengths in the intersecting domains of sustainability, social policy, and energy systems. Institutions with established research centres or affiliations in sustainability science and social energy transitions are prioritised, given their higher likelihood of offering specialised postgraduate training in energy poverty.

A critical component of the methodology is the curricular analysis, which involves evaluating course structures, module content, and learning outcomes. Particular attention is paid to the integration of interdisciplinary themes, including energy efficiency, renewable energy technologies, environmental justice, social equity, and policy modelling. This ensures the programs not only address the technical dimensions of energy systems but also the socio-political and economic frameworks essential for a comprehensive understanding of energy poverty. Geospatial orientation is another pivotal criterion; programs are assessed based on their regional or global focus. Some curricula are tailored to address context-specific drivers of energy poverty within European territories. In contrast, others adopt a comparative or global development lens, facilitating cross-regional policy learning and exchange.

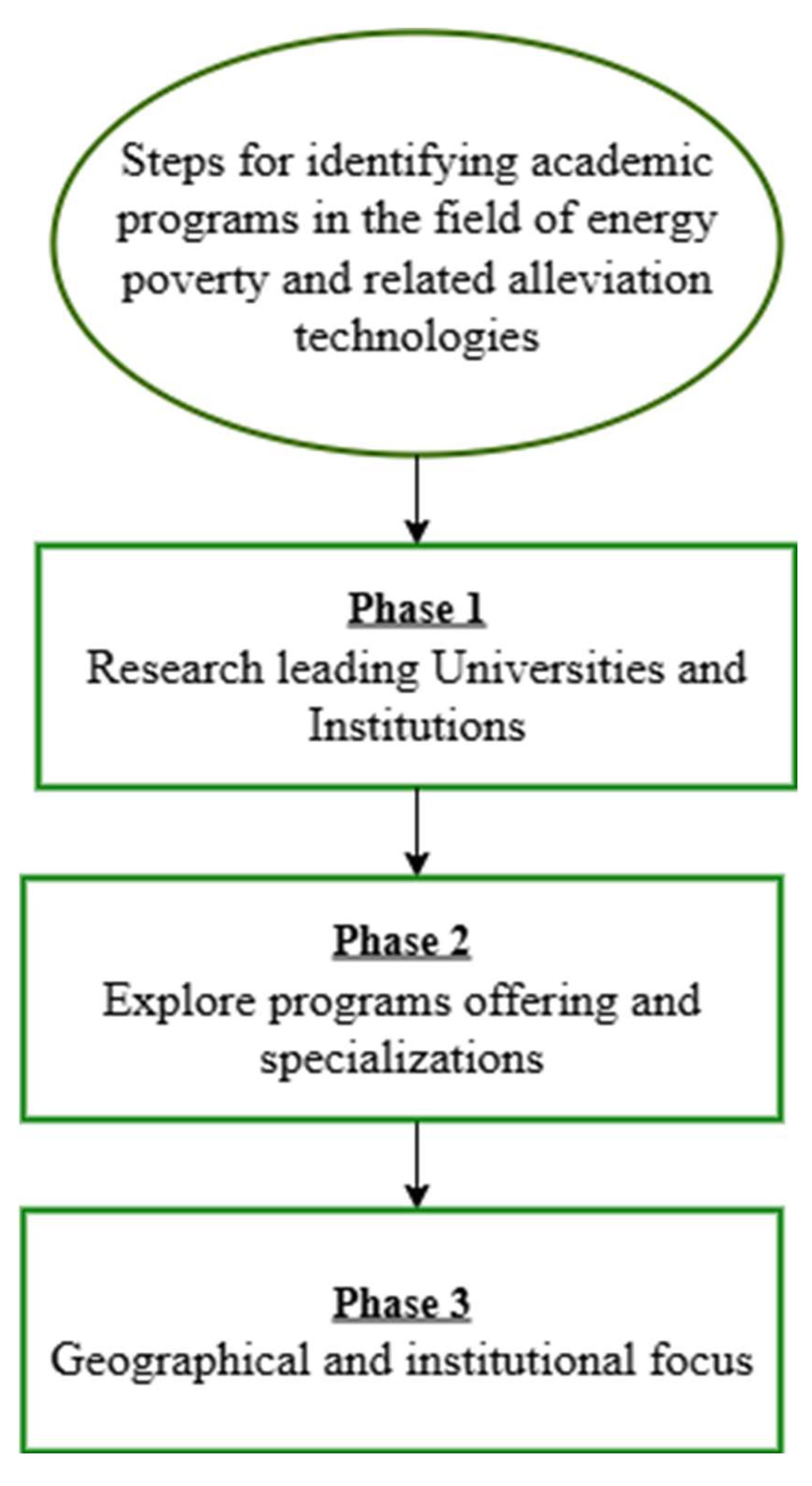

The methodology also incorporates a procedural review of institutional entry requirements. This includes an analysis of academic prerequisites, language competency thresholds, and critical admission timelines, ensuring that selected programs are accessible and aligned with candidate qualifications such as prior academic degrees, professional experience, language proficiency, and relevant technical or disciplinary backgrounds. As summarised in

Figure 1, these methodological steps collectively constitute a robust framework for identifying leading postgraduate programs focused on energy poverty within the European academic landscape. This structured approach enhances replicability and transparency by clearly documenting criteria and procedures for evaluating academic programs, ensuring that findings can be validated and compared across institutions.

As outlined previously, the initial and foundational phase (Phase 1) of this methodological framework involves identifying universities and research institutions that demonstrate notable strengths in energy studies, environmental science, social policy, and sustainability. This identification process is operationalised using reputable academic search engines and ranking databases, such as QS World University Rankings and Times Higher Education, alongside specialised educational platforms like Studyportals and MastersPortal. Institutions are filtered based on their track record in sustainability-focused research output, policy engagement, and interdisciplinary program offerings. The selection is further refined by reviewing institutional commitments to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly those targeting affordable and clean energy (SDG 7) and reduced inequalities (SDG 10). The outcome of this phase is a preliminary list of universities with high potential relevance to energy poverty studies.

In the second phase (Phase 2), a deep-dive content analysis is conducted by navigating official university websites, particularly departments or faculties that focus on energy, environmental governance, or social policy. Here, the focus shifts from institutional reputation to programmatic content. A key criterion is the existence of master’s programs that explicitly address energy poverty or encompass adjacent domains such as sustainable energy, energy policy, environmental justice, and development economics. The curriculum is systematically analysed to assess thematic comprehensiveness, including modules on renewable energy technologies, energy efficiency strategies, climate policy, equity and access, and socio-economic determinants of energy deprivation.

The final phase (Phase 3) involves a contextual refinement process, wherein programs are assessed for their geographic and thematic specificity in relation to energy poverty in Europe or globally. This includes reviewing regional case studies, community-based interventions, or programmatic foci that align with specific socio-political and climatic contexts. To ensure academic and practical relevance, final evaluations consider institutional research capacity, faculty expertise in energy poverty scholarship, and participation in international projects or networks (e.g., Horizon Europe, IEA, UNDP initiatives). The methodology concludes with a triangulated appraisal of institutional credibility, research infrastructure, and the strategic alignment of program objectives with the broader scientific and policy discourse on energy poverty.

3. Results on MSc Programmes in Europe

The research findings are interpreted and critically examined in this section. The degree to which energy poverty is incorporated as a thematic focus in postgraduate curricula varies significantly throughout Europe, as shown in

Figure 2, with pertinent programs dispersed unevenly across several nations. One important conclusion drawn from the mapping of these master’s programs is that the UK is a leader in the field. This is consistent with the fact that the UK was the first to conceptualise and formally introduce the term “energy poverty” into academic and policy discourse [

20,

21]. The next most notable nations after the UK are France, Greece, and Romania, all of which provide a sizable number of postgraduate programs that focus on this subject. These countries demonstrate a notable academic commitment to addressing energy poverty through education, reflecting both an institutional awareness and a policy-driven response to this multifaceted socio-economic challenge.

To support the mapping process, Studyportals Masters was selected as a reliable and comprehensive search engine for postgraduate education. The information provided includes course content, admission requirements, language of instruction, and university rankings. It also offers direct links to official university websites, application guidance, and student reviews. The retrieved data indicated a total of 26,795 postgraduate programs across Europe [

15].

From this extensive pool, a focused search identified 100 master’s programs that are related to the study and mitigation of energy poverty. However, it is worth noting that none of the identified postgraduate programs explicitly include the term “energy poverty” in their official titles. This observation suggests that, to the best of the author’s knowledge, there currently appears to be no dedicated master’s program exclusively focused on energy poverty and the associated technological, policy, and social dimensions. Instead, the concept is typically addressed indirectly, embedded within broader academic themes such as energy systems, renewable energy, sustainable development, or energy policy. These programs were selected based on their explicit coverage of topics such as sustainable energy, energy access, socioeconomic inequalities, and public policy.

The relatively small number of targeted programs, in comparison to the overall figure, highlights a significant academic gap and underscores the need for greater integration of energy poverty themes into postgraduate education across disciplines and countries. Particular emphasis was placed on broader engineering curricula with specialisations in Energy Technologies, Environmental Sciences, Engineering, Renewable Energy, and Sustainable Energy. Attention was also given to the social dimensions of these programs, particularly concerning energy poverty, through the examination of geographically and socially focused curricula.

Despite being acknowledged as a serious problem, energy poverty has not yet fully emerged as a stand-alone academic discipline at the master’s level in European higher education, according to this implicit integration. The subject is usually not treated as a primary, stand-alone focus, but rather is incorporated into interdisciplinary frameworks that address the shift to sustainable energy, equitable access, and wider socioeconomic impacts. However, energy poverty is a complex issue that affects society, policy, and technology. Developing thorough and practical solutions requires bridging the gap between the humanities and STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) disciplines. In that direction, France and the UK have made significant progress by establishing postgraduate programs that combine scientific and technical training with the social sciences and humanities, enabling their graduates to tackle energy poverty from both an engineering and socioeconomic perspective [

22].

In France, a notable example is the University of Pau’s Graduate School for Energy and Environmental Innovation (GREEN), which offers the multidisciplinary Master’s program ASSET (Applied Social Sciences in Energy and Environmental Transitions) [

23]. This program was developed as part of a national excellence project called “Investissements d’Avenir” (“Investments for the future” in English) to integrate social and “hard” sciences in sustainability education. The program’s mission makes the case for this kind of integration very evident: modern energy and climate issues are “extremely complex,” necessitating that academic fields “open up… to each other” to form practical solutions. As a result, the ASSET Master’s program emphasises the importance of social science knowledge in comprehending the formation of energy transitions by combining energy science with economics, geography, law, and sociology.

Interdisciplinary approaches that bridge the historical gap between STEM and the humanities in energy education are also important in the UK. According to a 2023 report by the Higher Education Policy Institute, “

the only way to solve the many challenges facing society” is to better connect STEM and humanities disciplines [

20]. The report cites the drive to net zero as an example that calls for a combination of technical and social perspectives. The MSc programs in energy and poverty offered by British universities reflect this philosophy. Peer-to-peer learning across disciplines is made possible, for example, by the University of Edinburgh’s MSc in Energy, Society, and Sustainability, which accepts students with backgrounds in both the social sciences and natural sciences. The curriculum strikes a balance between studying societal aspects of energy and low-carbon technology and policy content.

The reviewed master’s programs include a variety of courses that are thematically related to energy poverty, even if the term is not explicitly mentioned in the program title. Topics like sustainability principles, energy systems management, energy efficiency and conservation tactics, renewable energy and related technologies, and process optimisation are often covered in core modules. To address energy poverty from both an infrastructure and systems-level standpoint, these modules provide students with a strong foundation in the operational and technological aspects of contemporary energy systems.

Many programs include specific coursework that addresses the socio-economic and spatial aspects of energy poverty in addition to these technical elements. This encompasses demand-side management, sustainable energy supply, energy justice, policy design and evaluation, as well as modules on energy access and deprivation. In certain instances, corporate sustainability strategies, governance frameworks, and the political economy of energy transitions are among the more general topics discussed about energy poverty.

Core technical modules often encompass topics such as renewable energy and associated technologies, energy efficiency and conservation strategies, sustainability principles, energy systems management, and process optimisation. These modules provide students with a foundational understanding of the technological and operational aspects of modern energy systems, which are essential for addressing energy poverty from an infrastructural and systems-level perspective.

In addition to these technical components, many programs incorporate socio-economic and spatial dimensions of energy poverty through dedicated coursework. These include modules focused on energy access and deprivation, energy justice, policy design and evaluation, and sustainable energy provision and demand-side management. Other programs embed the topic within broader discussions of corporate sustainability strategies, governance frameworks, and the political economy of energy transitions. In some national contexts, such as France, these broader discussions—especially those related to humanities or “peripheral” topics—are often addressed through academic events, such as conferences, rather than through formal curriculum structures. However, since the enactment of the Climat et Résilience law in 2021 and the release of the Jouzel Report in 2022, the French higher education system has been explicitly mandated to “raise awareness and provide training in the challenges of the ecological transition and sustainable development.” This shift is gradually encouraging a more structured integration of sustainability and social dimensions into higher education programs.

Furthermore, interdisciplinary courses explore the social dimensions of sustainable development, including themes such as adult education for sustainability, power dynamics and societal structures, inclusive governance, inequality, and equitable economic growth.

Returning to the context of the United Kingdom, it becomes evident that the UK maintains a well-established tradition of integrating social policy, sustainability, and energy studies within its higher education and research institutions. This integration is strongly influenced by the country’s long-standing policy commitment to reducing energy poverty and advancing broader environmental and climate-related goals. Research and innovation are central to the UK’s academic approach, with universities actively contributing to national and international research initiatives focused on energy access, mitigating fuel poverty, and promoting a just energy transition. These efforts are supported by funding bodies such as UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), which prioritises interdisciplinary projects that address socio-technical energy challenges. This contextual reality underscores the importance of addressing energy poverty as a research and teaching priority within UK higher education, thereby fostering a generation of scholars and professionals equipped to tackle both domestic and global energy poverty challenges.

France, on the other hand, is focusing on environmental policy and leadership in social equity. French universities provide comprehensive programs that address the multifaceted nature of energy poverty. The nation’s progressive approach to sustainable development, as evident in policies such as the Energy Transition for Green Growth Act, supports the development of educational programs that integrate environmental sciences with social policy and economic analysis. The country’s commitment to the European Union’s energy goals and its national targets for reducing energy consumption and emissions creates a fertile ground for academic programs focused on innovative solutions to energy poverty.

Greece’s focus on energy poverty is shaped by its unique economic and energy context. The country has faced significant economic challenges, including austerity measures that have heightened the energy vulnerability of many households. The significantly high reliance on energy imports and fluctuating energy prices also exacerbate the issue. To this extent, the geographic position and climate also shape its academic focus, as addressing energy poverty is critical for mitigating climate impacts and promoting social welfare.

Romania’s inclusion highlights the Eastern European perspective on energy poverty, where significant economic disparities and challenges to energy infrastructure are prevalent. Romanian universities offer programs that emphasise both the technical and policy aspects of energy poverty, aiming to improve energy efficiency and access during economic transition. The country’s efforts to align with EU energy standards and address domestic energy needs drive the academic focus on this issue.

The prominence of master’s programs in energy poverty across these four countries underscores a shared European commitment to addressing energy poverty through education. Each nation’s approach is shaped by its socio-economic and environmental context: the UK’s integration of policy and technology, France’s blend of environmental and social policy, Greece’s focus on economic and energy challenges, and Romania’s emphasis on infrastructure and economic development. This diversity enriches the academic landscape, offering students varied perspectives and comprehensive training in tackling energy poverty. The alignment with broader EU goals, such as the Clean Energy for All Europeans package, further supports these programs, promoting collaborative and innovative solutions across the continent. These programs are crucial in advancing energy justice and sustainability in Europe by equipping graduates with the necessary skills and knowledge.

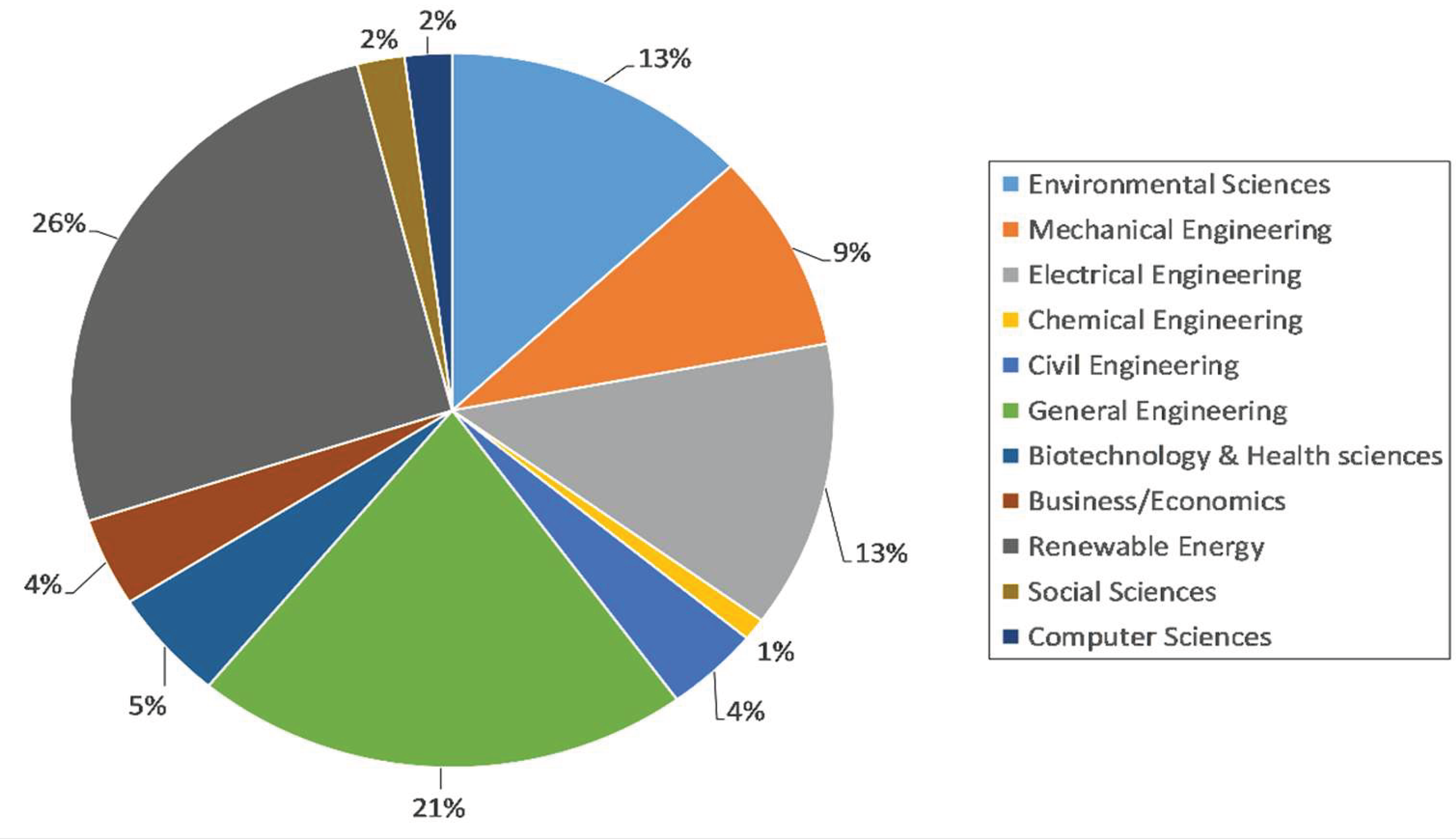

As illustrated in

Figure 3, the academic fields of renewable energy, engineering, and environmental sciences appear to exert the most significant influence on addressing energy poverty. These domains contribute essential theoretical frameworks, technical solutions, and policy insights necessary for developing sustainable and inclusive energy systems. The field of renewable energy, often considered a specialisation within mechanical engineering, is primarily concerned with harnessing natural resources such as solar, wind, hydro, and biomass to generate clean, reliable, and sustainable energy. The primary objective of this field is twofold: to advance research and innovation in emerging renewable energy technologies and to optimise the performance, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness of existing systems. In parallel, the field plays a strategic role in promoting the widespread adoption of renewable energy technologies through informed policy design, public engagement, and advocacy initiatives, which are essential for overcoming infrastructural, regulatory, and social barriers to implementation, especially in energy-poor regions.

Engineering, broadly defined, constitutes the second key domain contributing to energy poverty alleviation. This field integrates various sub-disciplines, including electrical, civil, mechanical, and systems engineering, to deliver holistic and practical solutions that span the entire energy value chain. These include the design of decentralised energy systems, smart grid infrastructure, efficient energy storage, and low-cost distribution networks tailored to underserved communities. A multidisciplinary engineering approach ensures that technological interventions are context-specific, scalable, and resilient, addressing the diverse needs and constraints of both urban and rural populations affected by energy poverty.

Environmental Sciences assesses the ecological impact of energy production and promotes sustainable practices. Emphasise the importance of renewable energy sources and efficient resource utilisation to mitigate environmental degradation. This field conducts environmental impact assessments for energy projects and promotes sustainable land and water use for energy generation. Electrical engineering focuses on generating, transmitting, and distributing electrical power. It is crucial in creating reliable and efficient energy supply systems, including smart grids and renewable energy technologies. Some essential tasks involve designing and implementing smart grid technologies to improve energy distribution. To this extent, it helps in the development of efficient electrical systems for RES integration. Also, they have a crucial role in enhancing battery storage and management systems. Mechanical engineering plays a significant role in creating energy-efficient systems while simultaneously seeking solutions to reduce costs. Next on the list are the sciences of biotechnology and health, which ensure that the applied energy solutions do not compromise the health of the people in the examined region and explore bioenergy options. This field analyses the health impacts of applied technologies, promoting safe and sustainable practices. A parallel activity of equal importance in this field is the development of bioenergy solutions, such as biofuels and biogas.

Civil engineering and business/economics stand out as two scientific disciplines that are equally involved in reducing energy poverty. The physical infrastructure required for energy systems, such as power plants, transmission lines, and distribution networks, is largely provided by civil engineering. It guarantees that these infrastructures are robust and able to withstand technical and environmental difficulties. However, the financial and policy frameworks that support energy affordability and accessibility are based on business and economics. To analyse market dynamics, create financial incentives, and develop policies that promote investment in sustainable energy infrastructure, this field is essential. The creation and use of economic models targeted at lowering the cost of energy for all societal segments constitutes a significant contribution.

In the field of energy poverty, computer science is a relatively new but growingly significant player. It makes intelligent and effective energy system management possible through data analytics, artificial intelligence (AI), and the Internet of Things (IoT). By optimising energy production, distribution, and consumption, these technologies raise the overall efficiency and dependability of the system. Predictive analytics, for example, aids in demand forecasting and enhances the responsiveness of applied energy systems.

Furthermore, addressing energy poverty is intrinsically linked to broader social injustices, particularly in developing nations. Therefore, it is essential to comprehend how energy policies affect society and what behavioural adjustments are necessary for their implementation. To create inclusive and efficient energy solutions, an interdisciplinary approach that bridges engineering, economics, computer science, and the social sciences is necessary.

Given the data above and the various ways that each scientific discipline has contributed to reducing energy poverty, a comparison of disciplines with complementary or overlapping roles is necessary. To achieve the common goal of fair and sustainable energy access, this analysis aims to illustrate how various disciplines conceptualise and address energy poverty. The first comparison centres on renewable energy and environmental sciences, two disciplines with closely related methods and approaches.

Environmental Sciences focuses on the ecological impacts and sustainability of energy solutions, while Renewable Energy explicitly targets the development of clean energy sources. Both fields are crucial for reducing environmental degradation and promoting sustainable practices, but Renewable Energy provides practical technologies for energy generation. Mechanical and electrical engineering are two fields that share a common standpoint. In more detail, mechanical engineering designs the physical systems and machinery for energy generation, whereas electrical engineering ensures the efficient transmission and distribution of electrical power. Both disciplines are essential for creating an efficient and reliable energy supply chain, but they address different stages of energy production and delivery.

A further comparison can be drawn between chemical engineering, biotechnology, and health sciences. Chemical engineering focuses on energy storage and conversion technologies, such as batteries and fuel cells, while biotechnology and health sciences examine the health impacts and develop bioenergy solutions. Chemical engineering provides the technological advancements necessary for efficient energy use, while biotechnology and health sciences ensure these technologies are safe and health-conscious.

Business and economics, as well as other fields, create the financial and policy frameworks to make energy solutions viable and affordable. At the same time, Social Sciences address the societal impacts and behavioural changes needed for adoption. Both fields are critical for successfully implementing energy solutions; however, business and economics focus on market and policy mechanisms, while the social sciences emphasise community engagement and social equity. Lastly, the field of engineering has a wide variety of specialities. For this purpose, a distinction is being made between general and specialised engineering fields. General engineering integrates multiple engineering disciplines to develop comprehensive solutions, whereas specialised fields such as mechanical, electrical, and civil engineering focus on specific aspects of the energy system. General engineering provides a holistic approach, ensuring that all energy system components work together efficiently, while specialised fields offer in-depth expertise in particular areas.

4. Discussion: The Role of Education on a Worldwide Scale

The current discussion section critically examines the systematic role of education in mitigating energy poverty and facilitating sustainable energy transitions. The aim is to present studies that highlight the role of education on a larger scale, supported by data from regions such as China, Portugal, and Africa, where energy poverty is being addressed through education. These regions are therefore focusing on educational strategies as part of their efforts to mitigate energy poverty. Investigating how energy poverty is addressed in these regions provides a unique and valuable comparative perspective. These three regions represent diverse socioeconomic contexts, which allows for a deeper understanding of how strategies to reduce energy poverty operate across different levels of development [

24,

25]. The analysis examines the impact of educational interventions on energy-related knowledge and behaviours. Particular attention is given to the heterogeneity of outcomes across different socio-economic and geographic contexts, thereby identifying patterns and limitations, and providing information regarding the scalability and effectiveness of education-based strategies within the energy policy framework.

4.1. China

In a study [

23], the relationship between education and energy poverty in China is explored by analysing data from 30 Chinese provinces from 2002 to 2021. The analysis reveals that high levels of education significantly contribute to reducing energy poverty, particularly in midwestern regions. Also, regarding the gender aspect, female education plays a slightly larger role than male education in alleviating energy poverty. The study highlights the impact of income and gender educational inequality on energy poverty alleviation, suggesting policies to enhance education and reduce gender inequality. It highlights the importance of integrating education policies into energy poverty alleviation strategies, thereby fostering a deeper understanding of the education-energy poverty nexus in developing economies.

In the same region, [

26] examines how China’s 1986 Compulsory Education Law affects energy poverty. Data from the China Family Panel Survey show that each additional year of education reduces energy poverty by 2.3%. The study highlights the importance of developing targeted academic curricula that bridge the gap between research and real-world applications, equipping graduates with the expertise to implement sustainable energy solutions. Expanding and refining postgraduate programs in this domain is crucial for developing skilled professionals who can drive impactful change in alleviating energy poverty. Moreover, given that women and rural inhabitants encounter elevated levels of energy poverty, targeted educational strategies and programs (i.e., encompassing adaptable educational pathways and vocational training) can enhance their earning capacity and contribute to achieving energy justice.

The study by [

25] examines the impact of energy poverty on educational inequality in China, with a focus on geographical and gender disparities. Findings show a significant reduction in energy poverty, particularly for women, and an inverted U-shaped relationship between energy poverty and gender inequality. Rural areas are most severely affected, with income inequality and education levels acting as transmission channels. The study suggests that policies should improve access to clean energy in underserved regions and integrate energy and education policies to promote social development.

4.2. Portugal

Castro et al. [

27] investigate energy poverty and thermal vulnerability among Portuguese higher education students, focusing on private rental housing across four regions in Portugal. Data from a survey of 848 students shows widespread discomfort in both winter and summer, with displaced students facing greater energy poverty due to precarious housing conditions. Regional disparities exist in the causes of energy poverty, but not in overall thermal discomfort levels. Alentejo students are particularly vulnerable to energy poverty due to poor building insulation and high energy costs. The study highlights the need for policy interventions in student housing, underscoring the importance of enhancing energy efficiency for student well-being.

4.3. Africa

In the study by Apergis et al. [

21], the impact of education on energy poverty is empirically assessed through the lens of human capital theory in 30 developing countries over a 15-year lifespan (2001-2016). GMM (Generalised Method of Moments) estimators were effectively used to address cross-sectional dependence and endogeneity. The study reveals that access to energy improves educational outcomes and literacy rates. Clean energy adoption also reduces barriers. Policymakers should integrate energy access programs with educational reforms to address energy poverty. Sustainable energy is crucial for human capital development and achieving SDG 7 and SDG 4.

In the work of Sule et al. [

28], the effects of energy poverty on education inequality and infant mortality are examined in 33 African countries. Empirical evidence from this study shows a significant relationship between energy poverty and these factors. Energy poverty is a major issue in Africa and is linked to higher child mortality rates and disparities in education. Poor households often prioritise energy needs over educational investments, leading to learning difficulties for children in energy-poor homes. To address this, policies should prioritise rural electrification and provide affordable access to energy. The authors conclude that government intervention is necessary for social equity and improving educational outcomes and child health.

Sy et al. [

29] presented a new approach to measuring energy poverty in Senegal, categorising it into four levels: extreme, moderate, transitional, and non-poor. It shows a decline in energy poverty from 2015 to 2019, with nearly half of the population experiencing moderate poverty. The study also emphasises the need for policymakers to prioritise access to modern energy services and to classify energy poverty to target interventions more effectively.

Makate [

30] investigates the education reform in Zimbabwe in 1980, revealing that it significantly reduced energy poverty by 8.56%. The reform increased schooling by 2.08 years, benefiting women and rural residents the most. Education also improved labour market outcomes, household wealth, and access to energy. The study highlights the importance of education in promoting gender equality and recommends that policymakers integrate educational policies into energy development strategies to achieve long-term reduction of energy poverty.

5. Conclusions

Tackling energy poverty in Europe is critical due to its far-reaching implications for public health, social equity, environmental sustainability, and economic resilience. Ensuring universal access to reliable and affordable energy services is not just a matter of infrastructure but a fundamental pillar of social justice. Energy is essential for maintaining a decent standard of living, and addressing energy poverty can bridge socio-economic disparities, enhance social inclusion, and alleviate pressure on social services. By fostering greater stability, these efforts contribute to a more cohesive and equitable society. From an environmental standpoint, combating energy poverty supports Europe’s ambitious climate goals, particularly under the European Green Deal’s objective of achieving climate neutrality by 2050. Improving household energy efficiency and integrating renewable energy sources reduce carbon footprints, lower greenhouse gas emissions, and decrease overall energy consumption. These advancements contribute to a more sustainable and resilient energy system while simultaneously addressing both environmental and social challenges.

Economically, reducing energy poverty stimulates growth and enhances financial stability. Lower energy costs translate into increased disposable income, which, in turn, drives consumer spending and economic growth. Investments in energy efficiency and renewable technologies not only reduce household energy expenses but also generate employment opportunities and foster innovation in the green economy. Additionally, shielding vulnerable populations from volatile energy prices strengthens economic resilience and mitigates the risks associated with market fluctuations. Beyond economic and environmental concerns, energy poverty has broader socio-political consequences. In regions where energy poverty is prevalent, dissatisfaction with political institutions often leads to social unrest, weakening democratic engagement. By addressing energy poverty, governments can enhance public trust, mitigate political instability, and foster a more prosperous and harmonious society.

Overall, the analysis indicates that while no master’s programs explicitly titled “energy poverty alleviation technologies” currently exist within the European higher education landscape, a significant number of relevant postgraduate offerings are available, particularly within the domains of engineering, environmental science, and energy studies. These programs often integrate critical themes, such as renewable energy technologies, energy efficiency, policy analysis, and social equity, core components necessary for addressing energy poverty. Among the surveyed institutions, the United Kingdom emerges as the leading contributor, accounting for 22 of the 100 identified programs. This leadership position reflects the UK’s historical and policy-driven commitment to combating energy poverty through both research and education.

Given the inherently multidisciplinary nature of energy poverty, which encompasses technical, socio-economic, political, and environmental dimensions, the development of sustainable and scalable solutions necessitates an integrated academic approach. Programs that combine insights from engineering, public policy, environmental sciences, social justice, and economics are best positioned to prepare graduates for the complex challenges associated with ensuring equitable energy access in both developed and developing contexts. The European academic community has made tangible progress in advancing awareness and knowledge of energy poverty through specialised postgraduate education. Nevertheless, the findings suggest that further expansion, formalisation, and curriculum refinement are needed to elevate these programs to a level where they can produce professionals with the holistic expertise and practical competencies required to enact meaningful change. Specifically, future academic offerings should aim to close the gap between theoretical research and real-world implementation by incorporating more applied components such as fieldwork, stakeholder engagement, and policy simulation exercises.

The countries contributing most significantly to the academic discourse on energy poverty, namely the United Kingdom, France, Greece, and Romania, serve as important regional case studies. Their contributions underscore the potential for national educational systems to play a pivotal role in shaping the energy transition agenda. This study underscores the critical need for postgraduate curricula that not only address the technical aspects of energy systems but also actively engage with the social and policy-related dimensions of energy justice. In conclusion, expanding and refining postgraduate programs focused on energy poverty is a vital step toward building a cadre of skilled professionals capable of designing and implementing integrated, equitable, and sustainable energy solutions across diverse global contexts.

Finally, this study aims to propose a potential curriculum based on the findings and insights derived from the collected research data. The proposed curriculum is directly informed by the results presented earlier in this work, ensuring that it reflects the key outcomes and evidence uncovered through the research. Based on the findings gathered from the analysis, a curriculum is proposed to address the educational needs identified across regional and thematic contexts. The curriculum synthesises key areas of knowledge and skills essential for supporting sustainable energy transitions. It includes foundational courses such as Introduction to Research Methodology and Fundamentals of Sustainable Energy, which establish a baseline understanding of energy systems and scientific inquiry. Building on this, specialised modules such as Energy Economics and Geopolitics, Capitalising on RES Investments in Local Markets, and Climate, Energy, and Justice explore the socio-political, financial, and ethical dimensions of the energy landscape. Technical competence is further enhanced through courses such as Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems and Energy Storage, Improvement of Buildings Energy Efficiency, Advanced Renewable Energy Technologies, and Sustainable Fuels and Transportation. The inclusion of Tackling Global-Local Challenges in Ethics ensures that students are equipped to navigate the moral and societal implications of energy decisions. The proposed curriculum not only supports interdisciplinary and practice-oriented learning but can also be considered a model for developing educational programs that aim to equip students with all the necessary skills.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge that part of the data used in this study originated from the FAIR: Finding a sustainable route to Academic excellence in Innovative Research project (

https://fair-msc-project.eu/fair-msc/), funded under the Erasmus KA2 Programme of the European Union (Project No. 2021-1-DK01-KA220-HED-000030127). The authors also acknowledge any administrative or technical support received.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| ASSET |

Applied Social Sciences in Energy and Environmental Transitions |

| EU |

European Union |

| GMM |

Generalized Method of Moments |

| HEIs |

Higher Education Institutes |

| IEA |

International Energy Agency |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| IRENA |

International Renewable Energy Association |

| SDG |

Sustainable Development Goals |

| STEM |

Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics |

| UKRI |

United Kingdom Research and Innovation |

| UNDP |

United Nations Development Programme |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Energy Statistics Pocketbook 2025. United Nations; 2025. [CrossRef]

- Van Grieken A, Stevens M, Costa-Ruiz B, Martínez JJ, Barbagelata M, Pilotto A, et al. Impact of the WELLBASED urban programs on health, well-being, and energy poverty. European Journal of Public Health 2024;34. [CrossRef]

- Byaro M, Mmbaga NF, Mafwolo G. Tackling energy poverty: Do clean fuels for cooking and access to electricity improve or worsen health outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa? World Development Sustainability 2024;4:100125. [CrossRef]

- Commission Recommendation (EU) 2023/2407on energy poverty n.d. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reco/2023/2407/oj/eng.

- World Energy Investment 2022.

- Byaro M, Mmbaga NF. What’s new in the drivers of electricity access in sub-Saharan Africa? Scientific African 2022;18:e01414. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World health statistics 2015. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

- IEA – International Energy Agency - IEA 2022. https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics.

- Share of primary energy consumption from renewable sources. Our World in Data 2024. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/renewable-share-energy?tab=table.

- Share of electricity production from coal. Our World in Data 2024. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/share-electricity-coal?tab=table).

- Household air pollution 2024. https://www.who.int.

- Murshed M, Ozturk I. Rethinking energy poverty reduction through improving electricity accessibility: A regional analysis on selected African nations. Energy 2023;267:126547. [CrossRef]

- Rasugu Ayub H, Jakanyango Ambusso W, Muriuki Manene F, Mongeri Nyaanga D. A Review of Cooking Systems and Energy Efficiencies. AJEE 2021;9:1. [CrossRef]

- Dogan E, Madaleno M, Inglesi-Lotz R, Taskin D. Race and energy poverty: Evidence from African-American households. Energy Economics 2022;108:105908. [CrossRef]

- Koomson I, Afoakwah C, Ampofo A. How does ethnic diversity affect energy poverty? Insights from South Africa. Energy Economics 2022;111:106079. [CrossRef]

- Carfora A, Scandurra G. Boosting green energy transition to tackle energy poverty in Europe. Energy Research & Social Science 2024;110:103451. [CrossRef]

- Soto GH, Martinez-Cobas X. Green energy policies and energy poverty in Europe: Assessing low carbon dependency and energy productivity. Energy Economics 2024;136:107677. [CrossRef]

- Carfora A, Scandurra G, Thomas A. Forecasting the COVID-19 effects on energy poverty across EU member states. Energy Policy 2022;161:112597. [CrossRef]

- Menyhért B. Energy poverty in the European Union. The art of kaleidoscopic measurement. Energy Policy 2024;190:114160. [CrossRef]

- Primc K, Dominko M, Slabe-Erker R. 30 years of energy and fuel poverty research: A retrospective analysis and future trends. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021;301:127003. [CrossRef]

- Janikowska O, Generowicz-Caba N, Kulczycka J. Energy Poverty Alleviation in the Era of Energy Transition—Case Study of Poland and Sweden. Energies 2024;17:5481. [CrossRef]

- Jiglau G, Bouzarovski S, Dubois U, Feenstra M, Gouveia JP, Grossmann K, et al. Looking back to look forward: Reflections from networked research on energy poverty. iScience 2023;26:106083. [CrossRef]

- GREEN Graduate Program - Master of Applied Social Sciences in Energy and Environmental Transitions (ASSET): Geography specialization 2025. https://formation.univ-pau.fr/en/.html.

- Apergis N, Polemis M, Soursou S-E. Energy poverty and education: Fresh evidence from a panel of developing countries. Energy Economics 2022;106:105430. [CrossRef]

- Moura P, Fonseca P, Cunha I, Morais N. Diagnosing Energy Poverty in Portugal through the Lens of a Social Survey. Energies 2024;17:4087. [CrossRef]

- Liang Y, Liu X, Yu S. Education and energy poverty: Evidence from China’s compulsory education law. Energy 2025;314:134135. [CrossRef]

- Castro CC, Gouveia JP. Chilling and sweltering at home: Surveying energy poverty and thermal vulnerability among Portuguese higher education students. Energy Research & Social Science 2025;119:103842. [CrossRef]

- Sule IK, Yusuf AM, Salihu M-K. Impact of energy poverty on education inequality and infant mortality in some selected African countries. Energy Nexus 2022;5:100034. [CrossRef]

- Sy SA, Mokaddem L. Measuring energy poverty in Senegal: A multifaceted approach. World Development Perspectives 2025;37:100664. [CrossRef]

- Makate M. Turning the page on energy poverty? Quasi-experimental evidence on education and energy poverty in Zimbabwe. Energy Economics 2024;137:107784. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).