1. Introduction

The history of vaccinology, from Edward Jenner’s pioneering work with cowpox in 1796 to the widespread application of Louis Pasteur’s principles of attenuation and inactivation, has been a narrative of monumental public health triumphs largely driven by empirical observation and serendipitous discovery [

1,

2]. This classical era, which yielded vaccines against scourges like smallpox, polio, and measles, relied on a “isolate, inactivate, inject” paradigm that, while effective for many pathogens, proved insufficient against more complex or non-culturable agents [

3]. The latter half of the 20th century witnessed the dawn of a new age, where the advent of molecular biology and recombinant DNA technology began to shift the field from a reactive, empirical science towards a proactive discipline of rational design [

4]. This transition signaled a departure from using whole organisms or their crude extracts towards leveraging precisely defined molecular components, a move that promised enhanced safety and manufacturing consistency. The true acceleration into the modern era, however, was catalyzed by the confluence of genomics and high-performance computing [

Error! Reference source not found.], giving rise to a powerful predictive engine for vaccine discovery. This revolution, termed “Reverse Vaccinology” by Rappuoli [

Error! Reference source not found.], fundamentally inverted the traditional discovery workflow. Instead of beginning with the pathogen in a culture dish, researchers could now start with its complete genome sequence in silico, using computational algorithms to mine the entire proteome and predict a comprehensive repertoire of potential protein antigens [

7]. This genomics-driven approach dramatically expanded the pool of vaccine candidates far beyond the handful of abundant proteins accessible through biochemical methods, enabling the identification of novel antigens that were previously invisible to conventional screening[

Error! Reference source not found.,

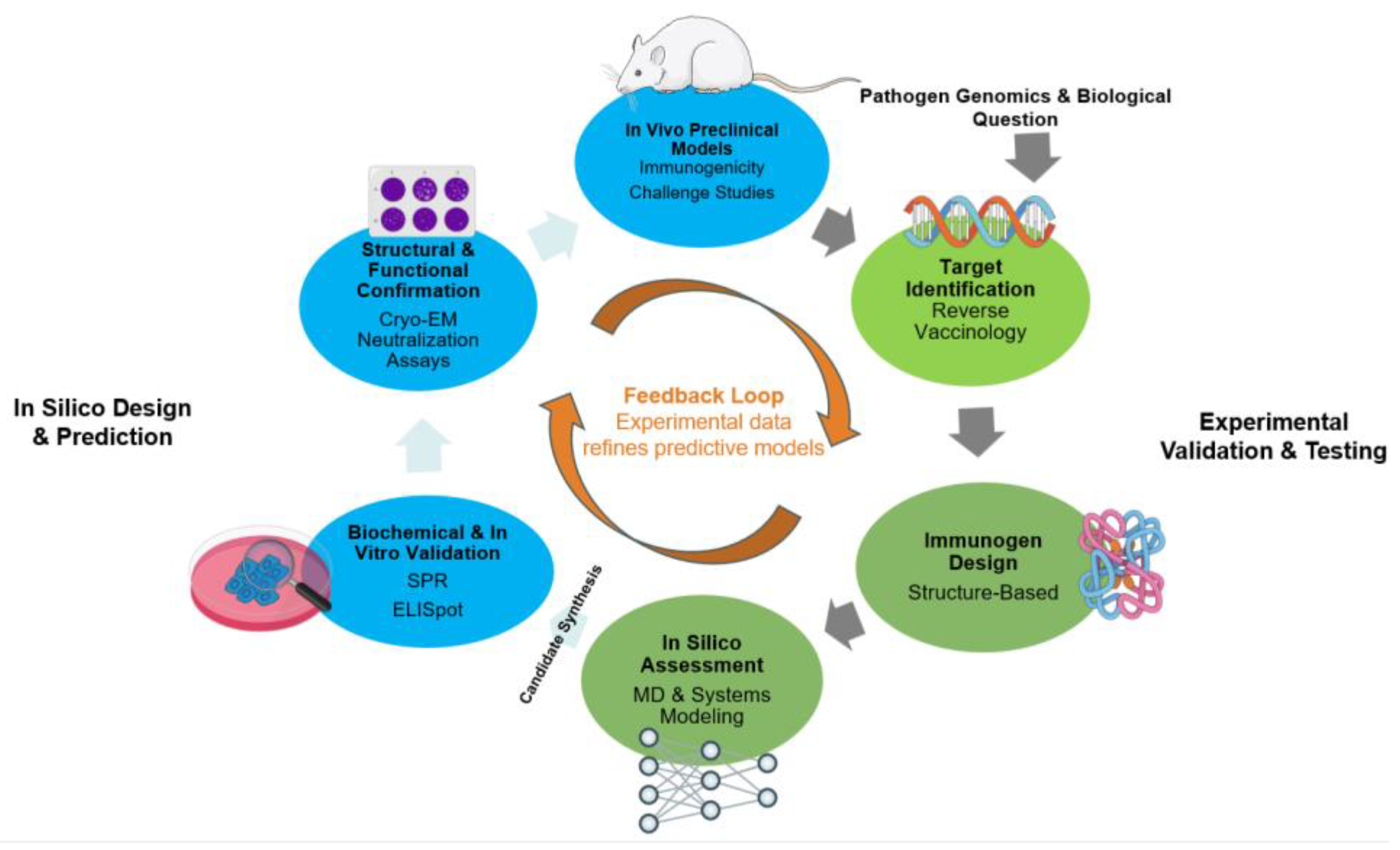

Error! Reference source not found.]. While these in silico tools provide unprecedented speed and scale, their predictions remain fundamentally theoretical hypotheses. The ultimate arbiter of a candidate’s worth is its performance in a biological system. Consequently, the cornerstone of modern, accelerated vaccine development is the synergistic and iterative cycle between computational prediction and rigorous experimental validation [

Error! Reference source not found.,11]. This is not a linear path from a computer model to a clinical trial, but a dynamic feedback loop where bioinformatic predictions guide targeted experiments, and the resulting experimental data—whether from high-resolution structural biology, high-throughput T-cell assays, or deep immunopeptidomic analysis—is fed back to refine, retrain, and improve the predictive power of the next generation of computational models [

Error! Reference source not found.-14].

This review will explore the intricate relationship between computational prediction and experimental validation that defines contemporary vaccinology. First, we will survey the diverse in silico toolbox used to design vaccine candidates, from immunoinformatics for epitope discovery and structure-based engineering of stable immunogens to systems-level modeling of the immune response. Next, we will detail “the experimental gauntlet”—the array of in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo methods employed to rigorously test, verify, and validate these computational hypotheses. Subsequently, we will present a series of prominent case studies—including the development of vaccines for Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV), COVID-19, personalized cancer, and HIV—that powerfully illustrate this integrated pipeline in action. Finally, we will discuss the current challenges and limitations of this paradigm and look toward the future, where emerging technologies like generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) and immune “digital twins” promise to further blur the lines between prediction and reality, heralding an era of truly personalized and precision vaccinology [Error! Reference source not found.-18].

Figure 1.

The Synergistic and Iterative Cycle of Modern Vaccine Development.

Figure 1.

The Synergistic and Iterative Cycle of Modern Vaccine Development.

2. The Computational Toolbox: Designing Vaccine Candidates In Silico

The initial phase of modern vaccine development unfolds not in a wet laboratory but on a digital drawing board, where a sophisticated suite of computational tools is employed to prospectively design and de-risk vaccine candidates. This in silico stage leverages vast biological datasets and advanced algorithms to rationally identify antigenic targets, engineer optimized immunogens, and simulate their behavior, thereby dramatically narrowing the field of candidates that require expensive and time-consuming experimental validation [Error! Reference source not found.]. These computational strategies can be broadly categorized by their primary objective, ranging from the discovery of entire antigens to the atomic-level engineering of specific epitopes and the systems-level prediction of the ensuing immune response.

2.1. Identifying the Target: Reverse Vaccinology and Immunoinformatics

2.1.1. Genome-Based Antigen Discovery and Prioritization

The advent of high-throughput genome sequencing catalyzed the “Reverse Vaccinology” paradigm, a strategy that begins with the digital representation of a pathogen to predict its entire antigenic repertoire [

20]. This approach proved its transformative power in the development of a vaccine against serogroup B meningococcus (MenB), a pathogen for which traditional methods had failed for decades. By computationally mining the MenB genome, researchers identified hundreds of novel protein candidates in silico, which were then systematically screened experimentally, leading to a licensed multicomponent vaccine [22,

Error! Reference source not found.].This process circumvents the major limitations of classical vaccinology, namely the need to cultivate the pathogen and the bias towards abundant but not necessarily protective proteins. Computational pipelines now routinely screen pathogen genomes to prioritize potential antigens based on predicted characteristics such as subcellular localization (secreted or surface-exposed proteins being prime candidates), sequence homology to known virulence factors, and the absence of homology to human proteins to minimize the risk of autoimmunity [

Error! Reference source not found.-

Error! Reference source not found.0].

2.1.2. Predicting Immunogenic Epitopes: T-Cell and B-Cell Targets

Once potential antigen proteins are identified, immunoinformatics tools are employed to dissect them into their constituent epitopes—the minimal fragments recognized by T-cells and B-cells. The prediction of peptide binding to Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) molecules, the most selective step in the antigen presentation pathway, is the most mature area of immunoinformatics. Machine learning-based tools like NetMHCpan have achieved remarkable accuracy in predicting peptide-MHC class I and class II binding, primarily by training on massive datasets of experimentally measured binding affinities and, more recently, on mass spectrometry-eluted ligands [

Error! Reference source not found.,

Error! Reference source not found.]. These T-cell epitope predictions are foundational for designing peptide-based vaccines, particularly for personalized cancer therapies where tumor-specific neoantigens are the primary targets [

28].

In contrast, the prediction of B-cell epitopes, which are recognized by antibodies, remains a more significant challenge. While linear B-cell epitopes can be predicted from sequence, most antibody recognition sites are conformational (discontinuous), involving disparate residues brought together by the protein’s three-dimensional fold. Although methods like BepiPred-2.0 and Epitope3D, which incorporate predicted or actual structural information, have shown improved performance over purely sequence-based tools, their overall predictive power is still modest, underscoring an area in active development [Error! Reference source not found.-Error! Reference source not found.]. Serving as the bedrock for all these predictive endeavors are comprehensive databases like the Immune Epitope Database (IEDB), which curate and publicly disseminate millions of experimentally characterized epitopes, providing the essential “ground-truth” data required to train, benchmark, and validate computational tools [32-34].

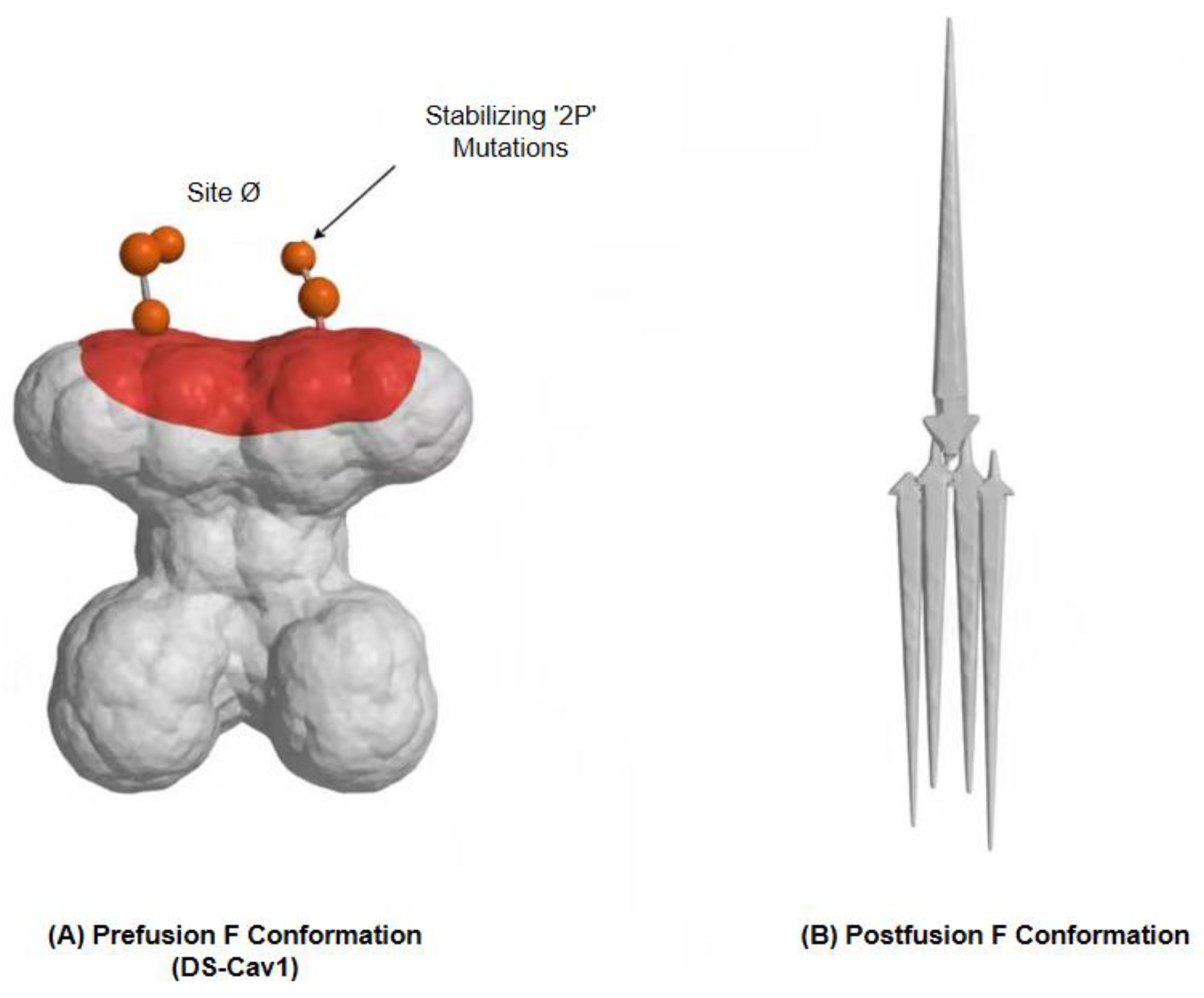

2.2. Engineering the Immunogen: Structure-Based Antigen Design

A fundamental challenge in vaccinology is that the most desirable antigenic targets are often structurally fragile. This is particularly true for the class I viral fusion glycoproteins that mediate entry for viruses like RSV, HIV, and coronaviruses. These proteins exist in a transient, high-energy “prefusion” conformation that displays the most potent neutralizing antibody epitopes, before collapsing into a highly stable, immunologically inferior “postfusion” state [Error! Reference source not found.]. An immunogen that prematurely adopts this postfusion form is effectively a decoy, failing to elicit the most powerful protective responses. The solution to this problem lies in structural vaccinology—the use of high-resolution atomic information to engineer more stable and effective antigens [Error! Reference source not found.].

For decades, the primary bottleneck in this field was the laborious and uncertain process of determining protein structures experimentally. A pivotal moment, however, arrived with the development of artificial intelligence systems capable of predicting protein structures with astounding accuracy directly from their amino acid sequence. The introduction of DeepMind’s AlphaFold and the Baker laboratory’s RoseTTAFold heralded a new epoch in structural biology [

35,

36]. These deep learning models, having been trained on the entire corpus of experimentally determined structures, can now generate atomically-accurate models for the vast majority of the proteome, as demonstrated by the public release of the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database [

37,

38]. This breakthrough effectively bridged the gap between genomic sequence and functional structure, providing an almost instantaneous structural blueprint for nearly any potential antigen.

This newfound capability enables the rational engineering of immunogens with unprecedented precision. The development of a successful RSV vaccine provides a landmark example. By analyzing the crystal structure of the RSV F protein in its prefusion state, McLellan and colleagues computationally identified key regions of instability. They hypothesized that introducing specific proline mutations could rigidify the protein’s backbone, effectively “locking” it in the desired prefusion conformation [

39]. This computational prediction was spectacularly validated through experimentation: the resulting stabilized immunogen, known as DS-Cav1, was not only stable but also elicited neutralizing antibody titers in animal models that were an order of magnitude higher than those induced by the postfusion protein. This “2P” stabilization strategy proved to be a generalizable principle, and its rapid application to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein by the same research groups was instrumental in the accelerated development of virtually all leading COVID-19 vaccines [

40,

41].

Beyond stabilizing individual antigens, structural information empowers the computational modeling of the critical interactions that underpin immunity. With accurate models for both antibody and antigen, information-driven docking programs like HADDOCK3 can be used to predict the three-dimensional architecture of their complexes [Error! Reference source not found.,Error! Reference source not found.]. Recent work by Giulini et al. (2023) has shown that combining AI-predicted antibody structures with such docking protocols significantly improves the success rate of modeling these interactions [Error! Reference source not found.]. This is complemented by AI-augmented, physics-based docking approaches that further refine binding predictions. While challenges in accurately predicting binding interfaces persist, especially for flexible molecules [Error! Reference source not found.], these tools provide invaluable hypotheses about the molecular basis of neutralization, guiding the design of novel immunogens intended to elicit specific, desirable antibody classes.

Figure 2.

Structure-Based Design of a Stabilized Prefusion RSV F Glycoprotein.

Figure 2.

Structure-Based Design of a Stabilized Prefusion RSV F Glycoprotein.

2.3. Assessing the Dynamics: The Role of Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations

Whereas structure prediction provides a static snapshot of an antigen, Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations furnish a “molecular movie,” revealing the dynamic behavior of biomolecules in motion [Error! Reference source not found.]. First applied to a protein in 1977, MD has evolved into an essential computational tool by calculating the forces between atoms to simulate their movements over nanosecond to microsecond timescales [Error! Reference source not found.]. As elegantly summarized by Hollingsworth and Dror (2018), MD simulations serve as a computational microscope, offering insights into protein flexibility, conformational changes, and the stability of molecular interactions that are often inaccessible to direct experimental observation [Error! Reference source not found.,51].

In the context of vaccine design, MD simulations provide a crucial intermediate step of computational validation. For instance, after immunoinformatic tools predict a set of promising T-cell epitopes, MD can be employed to simulate the behavior of these peptides when bound to their respective MHC molecules. Baruah and Bose (2020), in their work on 2019-nCoV, used this exact approach. Their simulations confirmed that the computationally identified epitopes formed stable, long-lasting hydrogen bond networks within the MHC binding groove, providing strong theoretical evidence that the complex would be stable enough to be effectively presented to T-cells [

52]. This application demonstrates how one layer of computational prediction (epitope binding) can be strengthened and filtered by another (dynamic stability) before committing to costly peptide synthesis and cellular assays.

2.4. Modeling the Response: Systems Vaccinology and Immune Simulation

Moving from the molecular to the systems level, a distinct class of computational models aims to predict the behavior not of a single protein, but of the entire immune system or even a whole population in response to vaccination. “Systems Vaccinology” represents a data-driven paradigm that integrates high-dimensional “-omics” data (e.g., transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) from vaccinated individuals to build predictive models of vaccine immunogenicity and efficacy [Error! Reference source not found.]. Pioneering studies by Pulendran and colleagues demonstrated that by analyzing early gene expression signatures in the blood of individuals vaccinated against Yellow Fever or seasonal influenza, it was possible to identify transcriptional modules that could predict, with remarkable accuracy, the magnitude of the protective antibody response that would develop weeks later [Error! Reference source not found.,Error! Reference source not found.]. This approach transforms vaccine evaluation from a retrospective exercise into a predictive science, offering early biomarkers of success or failure.

The ultimate ambition of this holistic modeling is the creation of “Immune Digital Twins”—dynamic, personalized computational models of an individual’s immune system [Error! Reference source not found.,Error! Reference source not found.]. Such a model, calibrated with patient-specific data, could hypothetically be used for “in silico” clinical trials, allowing researchers to test and optimize different vaccine antigens, adjuvants, or dosing schedules in a virtual environment before any physical administration, thus personalizing vaccination strategies for maximum benefit. On a broader scale, mathematical and agent-based models are used to simulate the dynamics of infectious disease spread within entire populations. These models can predict the impact of different vaccination coverage levels and prioritization strategies (e.g., targeting high-risk groups vs. uniform distribution), providing quantitative evidence to guide critical public health policy decisions during epidemics and pandemics [Error! Reference source not found.,Error! Reference source not found.].

Table 1 summarizes the main computational strategies employed in the design and preliminary assessment of vaccine candidates, highlighting their objectives and the key methodologies that generate the predictions requiring experimental validation.

3. The Experimental Gauntlet: Validating Predictions from Bench to Preclinical Models

Once a vaccine candidate has been conceived ‘in silico’, it must exit the digital realm and enter the “experimental gauntlet”—a multi-tiered process of rigorous testing designed to confirm its predicted properties and establish its biological relevance. This journey from theoretical concept to tangible immunogen is a validation cascade, where each successive stage provides a higher level of evidence, systematically filtering out flawed designs and building confidence in the most promising candidates. The first challenge in this cascade is to validate the most fundamental predictions: the identity and immunogenicity of the target epitopes themselves.

3.1. Validating Predicted Epitopes and Antigenicity

The initial step in validating a computationally predicted T-cell or B-cell epitope is often a direct biochemical test of the predicted interaction. For T-cell epitopes, this involves synthesizing the predicted peptide and measuring its binding affinity to the specific, purified MHC molecule for which it was predicted. Techniques such as fluorescence polarization or surface plasmon resonance can provide quantitative data (e.g., Kd values) that directly confirm or refute the core prediction of the bioinformatic algorithm—its capacity to engage the MHC molecule. While a positive result is encouraging, demonstrating binding is a necessary but insufficient condition for immunogenicity, as it does not account for antigen processing or T-cell receptor recognition.

A more definitive measure of an epitope’s potential is its ability to elicit a functional cellular response. This is assessed through a variety of in vitro T-cell assays using immune cells from previously exposed or vaccinated individuals. The Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Spot (ELISpot) assay is a widely used method to quantify the number of T-cells that secrete a specific cytokine, typically Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), upon stimulation with the predicted peptide [

58]. A significant increase in spot-forming cells compared to a control indicates the presence of a responsive T-cell population. A more granular view is provided by Intracellular Cytokine Staining (ICS) coupled with multi-color flow cytometry. This powerful technique not only confirms a response but also characterizes it, distinguishing between CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell activity and assessing their polyfunctionality—the simultaneous production of multiple effector molecules like IFN-γ, Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α), and Interleukin-2 (IL-2), which is often correlated with a more potent anti-viral response [59, 60]. Furthermore, peptide-MHC multimers (e.g., tetramers) can be used to directly stain and enumerate epitope-specific T-cells, providing a direct quantification of the size of the responding T-cell pool.

The ultimate validation for epitope presentation, however, comes from the direct and unbiased identification of peptides naturally processed and presented by cells. This “ground truth” is established through mass spectrometry (MS)-based immunopeptidomics. In this approach, MHC-peptide complexes are isolated from cells or tissues, and the bound peptides are eluted and sequenced by high-resolution mass spectrometry [

61]. This technique bypasses prediction entirely, providing a definitive list of the peptides that the cellular machinery has successfully processed and loaded onto MHC molecules for T-cell surveillance. Seminal work by Bassani-Sternberg et al. (2016) using this method on melanoma tumors provided a striking reality check for computational predictions: they found that the neoepitopes actually presented on the tumor surface were often not the top-ranked candidates from in silico algorithms, whereas the MS-identified peptides had a high rate of immunogenicity [

61,

63]. The development of sensitive, semi-automated workflows for this process has further enhanced its utility as a high-throughput validation tool for confirming the presentation of computationally prioritized neoantigens or viral epitopes [

64]. By confirming which peptides are genuinely part of the cellular “immunopeptidome”, this technology provides the most robust filter for refining epitope-based vaccine designs.

3.2. Confirming the Structure and Function of Designed Immunogens

For vaccine candidates born from rational, structure-based design, moving from a computer model to a purified protein is only the first step. It is paramount to experimentally verify that the engineered immunogen has folded into its intended three-dimensional conformation and that it functions as predicted. This validation process proceeds through a hierarchy of questions, moving from atomic-level structural confirmation to biophysical interaction analysis and, ultimately, to the assessment of functional immunogenicity.

The first critical test is to provide atomic-level proof that the computational design has been successfully realized in the physical molecule. This is the domain of high-resolution structural biology. Techniques such as Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) and X-ray Crystallography are the gold standards for this purpose. The rapid determination of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein structure by Wrapp et al. (2020) using Cryo-EM provided definitive visual confirmation that the computationally designed “2P” proline mutations successfully stabilized the protein in its desired prefusion state, a finding that underpinned its use in nearly all first-generation COVID-19 vaccines [

64]. Similarly, Cryo-EM studies can also overturn long-held assumptions and reveal unexpected molecular architectures, as demonstrated by the work of Shi et al. (2023), which resolved the structure of the postfusion spike in a membrane environment and redefined the location of the true fusion peptide [

64]. These structural snapshots are the ultimate validation of a protein’s physical integrity, confirming that engineered disulfide bonds have formed correctly and that the overall fold faithfully presents the target epitopes.

Beyond confirming the static structure, it is imperative to quantify the dynamics of the immunogen’s interaction with its biological targets, such as host cell receptors or specific antibodies. Real-time, label-free biophysical methods like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) and Biolayer Interferometry (BLI) are essential tools for this characterization [66-68]. These techniques measure the association and dissociation rates of molecular binding events, providing a precise equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) that quantifies binding affinity. This allows researchers to experimentally validate, for example, whether a stabilizing mutation has inadvertently disrupted a critical receptor-binding site or, conversely, has successfully preserved the conformation of a key neutralizing antibody epitope.

Ultimately, the most crucial validation for a potential vaccine antigen is its ability to elicit a functional immune response in a biological system. For humoral immunity, the initial assessment is typically an Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA), a high-throughput method that measures the total concentration, or titer, of antigen-specific antibodies in the serum of an immunized subject [

69]. However, the mere presence of binding antibodies does not guarantee protection. The definitive test of antibody function is the neutralization assay, which measures the capacity of elicited sera to prevent a virus from infecting host cells in vitro. This can be performed using the classic, labor-intensive Plaque Reduction Neutralization Test (PRNT) or, more commonly now, with safer and more scalable methods like pseudovirus neutralization assays (PNA) or automated, high-throughput live-virus neutralization platforms [

70]. The data from these assays are paramount, as they not only confirm the functional success of an immunogen but are also used to establish crucial correlates of protection, as demonstrated by Gilbert et al. (2024), whose work in a major COVID-19 vaccine trial formally linked specific neutralizing antibody titers to protection against severe disease [

71].

3.3. Testing Predicted Mechanisms and Pathways

Beyond validating the antigen itself, a critical function of the experimental gauntlet is to test the mechanistic hypotheses generated by more sophisticated computational models. Systems vaccinology and other simulation approaches often predict not just an outcome, such as antibody production, but the entire molecular cascade that leads to it—a specific chain of protein-protein interactions (PPIs), signaling events, and downstream changes in gene expression. Confirming these predicted pathways is essential for building a deep, causal understanding of a vaccine’s mechanism of action and for refining the models that guide future designs. Wang et al. (2024) provide a comprehensive guide to the experimental workflows required for this mechanistic validation [

72].

A primary step in this process is to confirm the predicted physical interactions between key signaling molecules. If a model hypothesizes that a vaccine adjuvant triggers its effect by causing protein A to bind to protein B, this interaction must be experimentally verified. The classic technique for this purpose is Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) [

73,

74]. In this method, an antibody specific to protein A is used to “pull down” protein A from a cell lysate; if protein B is found to be present in the immunoprecipitated complex (typically detected by Western Blot), it provides strong evidence of a direct or indirect physical association. For studying interactions within the dynamic context of a living cell, more advanced techniques like Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) are employed [

75,

76]. FRET works by detecting the transfer of energy between two fluorescently tagged proteins when they are in very close proximity (typically less than 10 nanometers), providing real-time spatial and temporal evidence of their interaction ‘in situ’.

Furthermore, to validate the predicted cascades, it is necessary to confirm their downstream consequences on gene and protein expression. If a model predicts that a particular signaling pathway will culminate in the upregulation of specific immune-related genes, this must be verified at both the transcript and protein levels. At the transcript level, quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) provides a highly sensitive and specific method to measure changes in the mRNA levels of a targeted set of genes, such as those encoding key cytokines or chemokines. For a global, unbiased assessment of the entire transcriptional landscape, RNA-Sequencing (RNA-Seq) is the method of choice, capable of confirming the predicted expression changes across thousands of genes simultaneously [77-80].

Crucially, an increase in mRNA does not always translate to an increase in functional protein. Therefore, protein-level validation is an indispensable final step. Western Blotting is the standard technique used to detect and quantify the level of a specific protein within cells, confirming that the transcriptional changes have resulted in altered protein synthesis. Complementing this, an ELISA can be used to measure the concentration of secreted proteins, such as cytokines (e.g., IFN-γ, IL-12) or chemokines, in the culture medium or serum, providing a direct measure of the cellular functional output and validating predictions about the immune microenvironment [81-84]. Together, these methods allow researchers to systematically dissect and confirm the molecular wiring that underpins a vaccine’s efficacy.

3.4. The ‘In Vivo’ Reality Check: Validation in Animal Models

The crucible of preclinical validation is the in vivo animal model. After an immunogen has passed the rigors of in vitro and ex vivo testing—proving it can bind its targets, stimulate cells, and maintain its structural integrity—it must finally demonstrate its worth within the complex, integrated milieu of a living organism. This stage moves the validation from possibility to protective reality, answering the ultimate questions: Is the vaccine candidate safe, and does it protect against disease?

The definitive test of a vaccine’s efficacy is the challenge study. In this experimental design, animals are first immunized with the vaccine candidate and then, after an appropriate interval for an immune response to develop, are deliberately exposed to the live, virulent pathogen. Protection is assessed through several key metrics: survival rates, reduction in clinical signs of disease (such as weight loss or fever), and, most quantitatively, a significant reduction in pathogen load in target tissues (e.g., viral titers in the lungs or bacterial counts in the spleen) as compared to a placebo or control group. For example, Hsieh et al. (2024) validated their computationally designed, prefusion-stabilized SARS-CoV-2 S2 subunit by showing it provided significant protection against mortality and reduced lung viral titers in mice after a lethal challenge with a mouse-adapted virus [

85,

86]. This outcome provides incontrovertible evidence that the engineered antigen can induce a truly protective immune state. Concurrently, these models are critical for safety validation. In the development of a novel mRNA vaccine for RSV, Shaw et al. (2025) utilized the cotton rat model not only to confirm potent protection but, crucially, to demonstrate the complete absence of vaccine-associated enhanced respiratory disease (ERD)—a historical safety failure that had plagued the field for decades [

87].

The choice of animal model is not trivial, as the predictive value of the in vivo validation is directly proportional to the model’s fidelity to human immunology. While standard mouse models are invaluable for initial screening, more sophisticated systems are often required. Non-human primates (NHPs), such as rhesus macaques, possess immune systems that more closely resemble those of humans and are frequently used as the final preclinical checkpoint before advancing a candidate to human trials. An even greater level of relevance for human-specific candidates is achieved through the use of humanized mice. Charneau et al. (2022), for instance, employed mice genetically engineered to express human HLA molecules to directly test the immunogenicity of predicted human neoantigens [

88]. Because these models can mount a T-cell response restricted by the same MHC molecules found in the human population, they provide a far more accurate and relevant platform for validating epitopes designed specifically for human use, a task that is impossible in conventional animal models. This careful selection and use of relevant in vivo models represents the final, essential step in a rigorous preclinical validation pipeline.

4. Case Studies: The In Silico to In Vivo Pipeline in Action

The theoretical power of the integrated computational-experimental pipeline is best illustrated through its application to real-world challenges. The development of vaccines against several of the most formidable pathogens of our time provides compelling case studies where this synergy has not only accelerated discovery but has enabled breakthroughs that were previously unattainable. These examples demonstrate the full arc of the process, from initial in silico prediction to definitive in vivo validation.

4.1. A Landmark Success: Structure-Based Design of the Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) Prefusion F Vaccine

For over half a century, the quest for a safe and effective RSV vaccine was paralyzed. The field was haunted by the memory of a disastrous 1960s clinical trial in which a formalin-inactivated whole-virus vaccine not only failed to protect children but led to vaccine-associated enhanced respiratory disease (ERD) upon subsequent natural infection, resulting in increased hospitalizations and two deaths. A central reason for this failure, understood only decades later, was that the viral fusion (F) glycoprotein—the primary antigenic target—was stabilized in its immunologically inert postfusion conformation [

89].

The breakthrough came not from traditional virology but from the intersection of human immunology and structural biology. Researchers isolated exceptionally potent neutralizing monoclonal antibodies from the memory B-cells of adult donors and then used X-ray crystallography to solve the atomic structure of these antibodies in complex with the F protein. This revealed a critical secret: the most powerful protective antibodies, some over 100 times more potent than the prophylactic antibody palivizumab, exclusively recognized epitopes on the metastable, prefusion (pre-F) conformation of the F protein [89-91]. This structurally-defined insight provided a clear, rational target for vaccine design: an immunogen that could stably present the pre-F conformation.

Armed with this atomic blueprint, a team led by McLellan and Graham at the National Institutes of Health embarked on a structure-guided computational design campaign [

20]. They used protein engineering software to predict specific mutations that would “lock” the F protein trimer in its desired pre-F state. Their primary in silico hypotheses involved introducing a stabilizing disulfide bond between key protomers and filling a hydrophobic cavity in the core of the protein to prevent the conformational collapse. The resulting computationally-designed candidate was named DS-Cav1.

The experimental validation that followed was both systematic and definitive. First, the DS-Cav1 protein was expressed and purified, and biophysical analysis confirmed its dramatically enhanced thermostability. Crucially, it bound with high affinity to pre-F-specific neutralizing antibodies, providing the first experimental proof that the computational design had successfully preserved the target epitopes. Next, the team solved the crystal structure of the DS-Cav1 protein itself, which provided unambiguous, atomic-level confirmation that it had folded into the exact pre-F conformation as predicted [

93,

94]. The final and most important preclinical validation came from in vivo studies. Immunization of mice and, subsequently, non-human primates with the DS-Cav1 immunogen elicited neutralizing antibody titers that were an order of magnitude higher than those induced by the postfusion form, proving its superior immunogenicity. This foundational work, moving seamlessly from computational hypothesis to experimental proof, directly paved the way for multiple successful RSV vaccines, including a refined version from Pfizer (RSVpreF) that demonstrated high efficacy in pivotal Phase 3 clinical trials, finally solving a 60-year-old public health challenge [96-97].

4.2. A Global Triumph: Accelerated Development of COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines

The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 in late 2019 triggered a global health crisis that demanded a vaccine at an unprecedented speed. The subsequent development of highly effective mRNA vaccines in under a year stands as perhaps the most dramatic and impactful validation of the integrated computational-experimental pipeline. This historic achievement was possible not because the science started from zero, but because the rational design principles validated during the long quest for an RSV vaccine provided a ready-made playbook that could be deployed instantly [

98].

The critical computational hypothesis was already established from prior work on other coronaviruses like MERS-CoV: a spike (S) protein stabilized in its prefusion conformation would be the optimal immunogen. Within days of the public release of the SARS-CoV-2 genome sequence on January 10, 2020, research groups were able to transfer this validated principle. They computationally identified the homologous region in the new virus’s S protein and applied the same “2P” (two-proline) stabilizing mutations that had proven effective for MERS-CoV. This in silico design was immediately translated into an experimental candidate [99-103].

The first crucial experimental validation came with breathtaking speed. By mid-February 2020, the team of Wrapp et al. published the high-resolution Cryo-EM structure of this S-2P protein [

104,

105]. The structure provided definitive experimental proof that the computationally transferred design worked as intended, locking the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein into the desired prefusion conformation and preserving the key epitopes on its receptor-binding domain (RBD). This rapid structural confirmation gave vaccine developers, particularly those using nimble mRNA platforms like Moderna and BioNTech/Pfizer, the confidence to proceed with clinical-scale manufacturing “at risk,” even before animal trial data were complete. This single validation step shaved months, if not years, off the traditional development timeline.

Even as the first vaccine candidates were being manufactured, the iterative design-build-test cycle continued in parallel. Hsieh et al. (2020) conducted a large-scale computational screening of 100 additional rationally designed mutations, leading to the creation of “HexaPro,” a version of the spike protein with six proline substitutions that was experimentally validated to be even more stable and express at nearly tenfold higher levels than S-2P, providing a superior second-generation antigen for subunit vaccines and diagnostics [

106,

107].

The ultimate validation, however, was the performance of the S-2P antigen in humans. Delivered via mRNA, the vaccine construct was shown in massive Phase 3 clinical trials to be over 90% effective in preventing symptomatic disease. Subsequent deep immunological profiling of vaccinated individuals provided the mechanistic validation, confirming that the vaccine elicited not only exceptionally high titers of durable neutralizing antibodies but also robust, poly-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses [109-110111]. These T-cells were found to target conserved epitopes across the spike protein, providing a critical second layer of defense against emerging variants. The COVID-19 vaccine story is thus the ultimate testament to the power of this paradigm, where years of investment in foundational computational and structural biology enabled a response of historic speed and success.

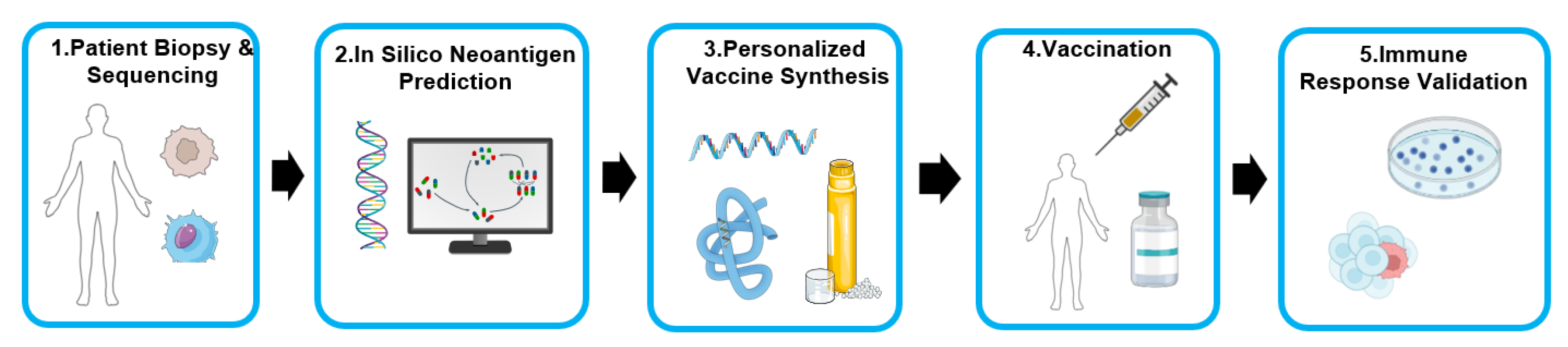

4.3. The Frontier of Personalization: Neoantigen Discovery for Cancer Immunotherapy

The integrated computational-experimental pipeline finds its most personalized application in the development of bespoke cancer vaccines, a strategy centered on targeting the tumor’s unique mutational landscape. Every tumor accumulates a set of somatic mutations, some of which create novel protein sequences known as neoantigens. Because these are absent from normal tissues, they are recognized as foreign by the immune system and represent ideal, highly specific targets for immunotherapy. The challenge lies in sifting through a patient’s entire “mutanome” to identify the handful of neoantigens that are actually processed, presented by the tumor’s HLA molecules, and capable of eliciting a potent T-cell response. This process perfectly encapsulates the in silico to in vivo workflow.

The process begins with the patient. A biopsy of the tumor and a sample of normal tissue are subjected to high-throughput whole-exome and RNA sequencing. This generates a comprehensive digital blueprint of all expressed, non-synonymous mutations unique to that patient’s cancer. This raw genomic data, however, represents a vast search space, often containing hundreds of potential neoantigens. The first critical filtering step is purely computational. Immunoinformatics algorithms are used to predict, for each mutation, the binding affinity of the resulting neo-peptide to the patient’s specific HLA class I and class II alleles. This in silico analysis winnows the extensive list down to a manageable set of top-ranked candidates, typically 10 to 20 peptides predicted to be the most likely to be presented and recognized. An early preclinical validation of this integrated genomics-proteomics-computation workflow by Yadav et al. (2014) demonstrated its power, successfully using it to identify therapeutically effective neo-epitopes in murine tumor models [

111].

The computationally-prioritized neoantigen sequences are then manufactured into a personalized vaccine. Landmark first-in-human clinical trials have validated two primary platforms for this: synthetic long peptides, administered with an adjuvant like poly-ICLC [

112], and messenger RNA (mRNA), where a single RNA molecule is engineered to encode multiple neo-epitopes [

113]. This step translates the purely digital information into a physical therapeutic agent tailored to the individual.

The ultimate validation occurs within the patient. Following vaccination, the central hypothesis is tested: did the computationally predicted neoantigens induce a tangible and specific T-cell response? This is answered through ‘ex vivo’ T-cell assays on the patient’s peripheral blood. The groundbreaking trials by Ott et al. (2017) and Sahin et al. (2017) provided resounding experimental proof of this principle. In both studies, vaccination was shown to be safe and highly immunogenic, inducing robust and polyfunctional CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses against a significant fraction of the predicted neoantigens. Sahin et al. reported that every patient developed T-cell responses, with immunity detected against 60% of the selected neo-epitopes, while Ott et al. observed T-cell reactivity to the majority of their peptide pools [114-118]. These vaccine-induced T-cells were shown to be highly specific for the mutated peptide over its wild-type counterpart. Clinically, these responses translated into tangible benefit, with many patients remaining disease-free and, in some cases, achieving complete tumor regression when the vaccine was combined with checkpoint blockade therapy. These studies serve as definitive proof-of-concept, demonstrating that the full pipeline—from genomic sequencing and computational prediction to vaccine synthesis and clinical validation—can successfully translate a patient’s unique tumor data into a potent, personalized, and life-saving immunotherapy.

Figure 3.

Workflow for Personalized Neoantigen Cancer Vaccine Development.

Figure 3.

Workflow for Personalized Neoantigen Cancer Vaccine Development.

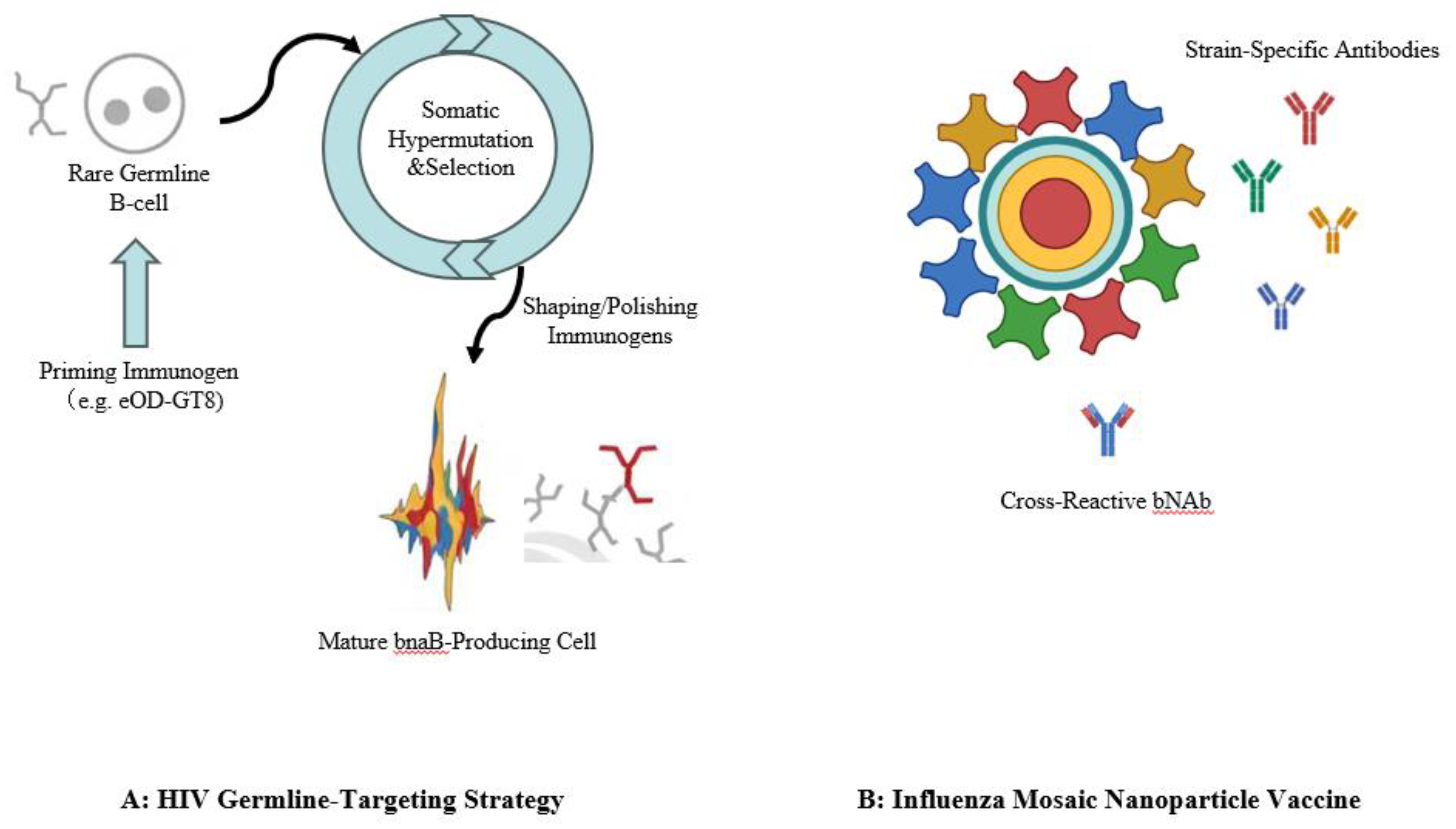

4.4. Tackling a Grand Challenge: Iterative Design of Germline-Targeting HIV Immunogens

The immense challenge posed by the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), with its unprecedented genetic diversity and glycan-shielded envelope protein (Env), has thwarted conventional vaccine development for four decades [

119]. The modest success of any trial has highlighted the need for an exceptionally sophisticated approach, one capable of eliciting rare and powerful broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs). This necessity has given rise to the most ambitious application of the computational-experimental pipeline to date: the strategy of germline-targeting.

This audacious strategy moves beyond designing a single immunogen and instead aims to computationally choreograph the entire process of B-cell affinity maturation. The journey begins by identifying a class of potent bNAbs from infected individuals and computationally inferring the sequence of their “unmutated common ancestor” (UCA)—the naive B-cell receptor that initiated the response. The central paradox is that these germline precursors often do not bind to the mature, native HIV Env protein, meaning they are never activated by natural infection or conventional vaccines. The first step, therefore, is to computationally design a novel “priming” immunogen specifically engineered to “catch” and activate these exceedingly rare precursor B-cells .

The design of the eOD-GT8 60-mer immunogen is a masterclass in this process. Researchers used structure-based computational protein design to re-engineer a fragment of the HIV Env protein, optimizing it to bind with sufficient affinity to the germline precursors of the VRC01-class of bNAbs. This computationally designed immunogen, displayed multivalently on a self-assembling nanoparticle scaffold to enhance B-cell signaling, was then advanced into a first-in-human clinical trial (IAVI G001) for its definitive experimental validation [

120].

The results, as reported by Cohen et al. (2023), were a landmark success[

121]. The vaccine was found to be safe and, crucially, achieved its primary molecular goal: it successfully activated the target B-cell precursors and induced the desired memory B-cell response in 97% of vaccine recipients. This provided the first-ever human proof-of-concept that a computationally designed immunogen can specifically engage and expand a pre-defined, rare B-cell population. The study also validated the induction of robust, publicly targeted helper T-cell responses, which are essential for driving the B-cell maturation process .

This successful priming, however, is only the beginning of a longer, pre-planned immunization journey. The germline-targeting strategy necessitates a sequence of “shaping” and “polishing” immunogens, each also being computationally designed and structurally characterized. These subsequent boosters will be subtly different from the priming immunogen, designed to select for B-cells that acquire specific somatic mutations, thereby incrementally guiding the antibody response along a precise evolutionary pathway toward the breadth and potency required to neutralize the vast diversity of circulating HIV strains. The HIV vaccine effort thus represents the pinnacle of the iterative computational-experimental cycle—a long-term project to rationally design and experimentally validate not just a single product, but an entire immunological process [122-126].

4.5. Broadly Protective Vaccines: Computationally Guided Design of Nanoparticle Vaccines for Influenza

The annual cycle of reformulating seasonal influenza vaccines to match circulating strains is a stark reminder of the limitations of traditional vaccine approaches against rapidly evolving pathogens. The quest for a “universal” influenza vaccine that provides broad and durable protection against diverse strains has therefore become a major public health goal. Here again, the integrated computational-experimental pipeline is at the forefront, primarily through the rational design of nanoparticle-based immunogens that aim to redirect the immune response toward conserved viral epitopes.

One major school of thought, mirroring the strategy for RSV and HIV, focuses on targeting the highly conserved but immunologically subdominant hemagglutinin (HA) stem domain. The computational hypothesis is that by removing the variable, immunodominant HA head, an engineered “headless” HA stem immunogen can focus the B-cell response on this vulnerable site, which is the target of many known bNAbs. Corbett et al. (2019), for instance, used computational protein design to stabilize headless HA stem trimers from group 2 influenza viruses and genetically fused them to self-assembling ferritin nanoparticles [

127]. The experimental validation for this design was elegant and precise. By creating engineered B-cell lines expressing the computationally inferred germline ancestors of human bNAbs, they demonstrated in vitro that their nanoparticle immunogens could specifically bind to and activate the correct rare B-cell precursors required to initiate a broadly protective immune response. This provided direct experimental evidence that the computationally designed antigen could engage the desired cellular starting material.

A complementary, yet distinct, strategy aims not to hide the head but to diversify it. In this approach, computational design is used to engineer “mosaic” nanoparticles that co-display HA proteins from multiple, antigenically distinct influenza strains on the surface of a single nanoparticle scaffold. The guiding hypothesis is that this multivalent, diverse presentation prevents any single HA from eliciting an immunodominant strain-specific response, thereby promoting the expansion of cross-reactive B-cells that recognize conserved epitopes. This concept was powerfully validated in preclinical studies by Boyoglu-Barnum et al. (2021) [128-131]. Their quadrivalent mosaic nanoparticle vaccine was tested in mice and ferrets and compared directly to a licensed commercial quadrivalent influenza vaccine (QIV). The results were striking: while both vaccines induced strong immunity to the vaccine-matched strains, the mosaic nanoparticle vaccine provided significantly broader protection. It elicited higher levels of cross-reactive antibodies and, most importantly, conferred near-complete protection against lethal challenge with mismatched and even heterosubtypic pandemic-potential viruses like H5N1 and H7N9, against which the commercial vaccine offered little to no protection.

Together, these parallel efforts in influenza research showcase the versatility of the computational-experimental pipeline. Whether by focusing the immune response on a single conserved domain or by broadening it through diverse antigen presentation, computationally-guided nanoparticle design has been experimentally validated as a powerful and promising platform for finally breaking the cycle of seasonal influenza and developing truly broadly protective vaccines.

Figure 4.

Advanced Immunogen Design Strategies for Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies.

Figure 4.

Advanced Immunogen Design Strategies for Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies.

5. Challenges, Future Directions, and Conclusion

Despite the remarkable successes that have reshaped the landscape of vaccine development, the integrated computational-experimental paradigm is not without its challenges. The path from a digital sequence to a protective immune response in a diverse human population is complex, and significant hurdles remain. For the field to continue its rapid pace of innovation, it is critical to acknowledge and address the gaps that still exist in prediction, translation, and the foundational data infrastructure that supports all research.

5.1. Current Hurdles and Limitations

5.1.1. The Prediction Gap: From Binding to True Immunogenicity

A persistent challenge lies in the gap between what is computationally easy to predict and what is immunologically relevant. Most T-cell epitope prediction algorithms, for instance, are highly optimized to predict peptide-MHC binding affinity. While this is a necessary first step, it is not sufficient for immunogenicity, which also depends on antigen processing, T-cell receptor recognition, and the broader immunoregulatory context. This is particularly true for CD4+ T-cell epitopes, whose longer, more variable peptide lengths and complex processing pathways make them significantly harder to predict than their CD8+ counterparts [

131,

137]. Even greater difficulties plague the prediction of B-cell epitopes. The vast majority of antibody recognition sites are conformational, yet most widely used tools rely on linear sequence analysis. While structure-based predictors like epitope3D have shown improved performance, the accurate ‘de novo’ prediction of conformational B-cell epitopes remains a largely unsolved problem in computational immunology [

138].

5.1.2. The Translational Gap: From Animal Models to Human Immunity

A second major hurdle is the translational gap between preclinical animal models and human clinical outcomes. While essential for initial efficacy and safety validation, animal models—even non-human primates—do not perfectly recapitulate the human immune system. Fundamental differences in HLA/MHC diversity, the frequency and function of immune cell subsets, and the expression of innate immune receptors mean that a vaccine candidate that performs flawlessly in a mouse or macaque may elicit a suboptimal response or fail entirely in human trials. This discrepancy highlights the risk of over-reliance on preclinical data and underscores the urgent need for more predictive humanized models and in vitro human-cell-based systems to better bridge the gap between bench and bedside.

5.1.3. The Data Gap: Building on a Foundation of Sand

Finally, the very foundation of the computational pipeline—data—faces systemic challenges. The predictive power of any machine learning model is fundamentally limited by the quality and quantity of the data it is trained on. The field of immunology suffers from a proliferation of heterogeneous datasets with varying standards, formats, and levels of annotation, hindering the development of robust, generalizable models. Furthermore, a lack of standardized model-sharing practices often makes it difficult or impossible for researchers to reproduce, validate, or build upon published computational work, contributing to a “reproducibility crisis” [

134]. A growing consensus within the community calls for a stronger commitment to the FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) data principles and the development of common platforms and standards, ensuring that the foundational data and models upon which the next generation of predictions will be built are solid and reliable [

135].

5.2. The Next Frontier: Emerging Technologies and Concepts

Confronting these challenges is actively driving the next wave of innovation, with several emerging technologies and concepts poised to redefine the boundaries of computational vaccinology. These frontiers promise not just to patch the gaps in the current pipeline but to create entirely new capabilities for designing and validating vaccines with unprecedented precision and speed.

The horizon of immunogen design is being reshaped by the transition from predictive to generative AI. While tools like AlphaFold excel at predicting the structure of existing proteins, new deep learning frameworks are being developed to design completely novel proteins (de novo) with precisely specified functions. Geometric deep learning models can now generate hyperstable protein backbones capable of presenting specific epitopes or even design functional enzymes from scratch, a capability confirmed through experimental validation [

137]. This opens the door to creating bespoke immunogens with ideal stability and antigenicity profiles. This rational design extends beyond the antigen itself to the discovery of novel molecular adjuvants, where virtual screening and computational chemistry can identify small molecules that target specific immune pathways, such as the inhibition of regulatory T-cells, to enhance vaccine potency [

138].

Perhaps the most ambitious goal is the realization of the “Immune Digital Twin”—a dynamic, high-fidelity computational model of an individual’s entire immune system [

138]. By integrating a person’s genomic data, immune history, and real-time physiological state, such a model could serve as a virtual avatar for personalized medical testing. This would enable in silico clinical trials, where the safety and efficacy of multiple vaccine candidates and dosing strategies could be simulated for a specific individual before a single physical dose is administered, revolutionizing clinical trial design and ushering in an era of precision preventative medicine [

139].

The fuel for these advanced AI models and digital twins will come from ever-deeper and more comprehensive immune profiling. The next evolution of systems vaccinology is moving beyond transcriptomics to integrate multi-omics data, including proteomics, metabolomics, and high-dimensional single-cell analyses from techniques like mass cytometry (CyTOF). By capturing a more holistic snapshot of the cellular and molecular response to vaccination, researchers can uncover more subtle and powerful predictive signatures. The recent discovery of a platelet-related transcriptional signature that predicts the durability of antibody responses across multiple different vaccines is a powerful example of how deeper, multi-modal data can lead to novel mechanistic insights and universally applicable biomarkers [

140,

141].

Ultimately, these disparate technological threads are weaving together toward the overarching vision of truly personalized vaccinology. In this future paradigm, a patient’s unique genomic data and immune profile could be used to inform their digital twin. Generative AI could then design a bespoke vaccine—a custom immunogen and adjuvant combination optimized for that individual’s specific HLA type, pre-existing immunity, and potential risk factors. This strategy would be tested and refined in silico before being rapidly manufactured, likely via an mRNA platform. This represents the full realization of the computational-experimental cycle, transforming vaccination from a one-size-fits-all public health tool into a precise, personalized medical intervention.

6. Conclusion

The discipline of vaccinology has irrevocably transitioned from its empirical roots into a new era of rational, predictive science. The central thesis of this review is that this transformation has been powered by the establishment of a synergistic and iterative cycle between in silico prediction and rigorous experimental validation. The journey from a digital sequence to a protective serum is no longer a path of serendipity but a structured, multi-stage pipeline. Computational tools, ranging from immunoinformatics for epitope discovery to artificial intelligence for de novo structural design, now provide the blueprints for novel immunogens with unprecedented precision. Yet, these predictions are only as valuable as their empirical confirmation. The experimental gauntlet—spanning biochemical assays, functional cellular analyses, and definitive in vivo challenge studies—serves as the indispensable arbiter of truth, grounding computational hypotheses in biological reality. The landmark successes in developing vaccines for previously intractable targets like RSV and the historic speed at which effective COVID-19 vaccines were created are not isolated triumphs but definitive proof of this paradigm’s power. As computational capabilities continue to expand and our understanding of the human immune system deepens, this virtuous cycle—where data informs models, models generate predictions, and experiments validate those predictions to generate new data—will only accelerate. This fusion has fundamentally reshaped vaccinology into a more precise, rational, and rapid discipline, one that is now better poised than ever to meet the global health challenges of the future.

Author Contributions

Y.Z.(Yu Zhang)was responsible for the manuscript writing and data collection. Y.P. and Q.H. were responsible for funding acquisition and conceptualization. D.T., Y.D., T.C. and Y.Z. (Yuan Zhang) made significant contributions to the conception of the article and data analysis. D.T., Y.D., T.C. and Y.Z. (Yuan Zhang) checked and revised the article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This review was supported by the State Key Laboratory of Drug Regulatory Sciences (standardized construction and application of tumor organoids, 2025SKLDRS0347; research on key technologies and methods for evaluating the nonclinical efficacy of polylactic acid macroporous microsphere long-acting vaccines, 2025SKLDRS0351).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Raja, N.; Ashwinth Jothy, A. Edward Jenner’s Discovery of Vaccination: Impact and Legacy. Cureus 2024, 16, e68993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotkin, S. History of vaccination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014, 111, 12283–12287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gregorio, E.; Rappuoli, R. From empiricism to rational design: A personal perspective of the evolution of vaccine development. Nature Reviews Immunology 2012, 12, 745–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facciolà, A.; Visalli, G. Past and Future of Vaccinations: From Jenner to Nanovaccinology. Vaccines 2023, 11, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flower, D.R.; Macdonald, I.K.; Ramakrishnan, K.; Davies, M.N.; Doytchinova, I.A. Computer aided selection of candidate vaccine antigens. Immunome Research 2010, 6 (Suppl 2), S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappuoli, R. Reverse vaccinology. Curr Opin Microbiol 2000, 3, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanampalliwar, A.M. Reverse Vaccinology and Its Applications. Methods Mol Biol 2020, 2131, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Moriel, D.G.; Scarselli, M.; Serino, L.; Mora, M.; Rappuoli, R.; Masignani, V. Genome-based vaccine development: A short cut for the future. Hum Vaccin 2008, 4, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serruto, D.; Serino, L.; Masignani, V.; Pizza, M. Genome-based approaches to develop vaccines against bacterial pathogens. Vaccine 2009, 27, 3245–3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunita; Sajid, A. ; Singh, Y.; Shukla, P. Computational tools for modern vaccine development. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2020, 16, 723–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarvmeili, J.; Baghban Kohnehrouz, B.; Gholizadeh, A.; Shanehbandi, D.; Ofoghi, H. Immunoinformatics design of a structural proteins driven multi-epitope candidate vaccine against different SARS-CoV-2 variants based on fynomer. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 10297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzamani, K.; Saeidi, A.A.; Hosseinzadeh, H.R.; et al. Vaccine design and delivery approaches for COVID-19. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 100, 108086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, H.; Jakhar, R.; Sehrawat, N. Designing spike protein (S-protein) based multi-epitope peptide vaccine against SARS COVID-19 by immunoinformatics. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liljeroos, L.; Malito, E.; Ferlenghi, I.; Bottomley, M.J. Structural and computational biology in the design of immunogenic vaccine antigens. J. Immunol. Res. 2015, 156241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, B.F.; Gilbert, P.B.; McElrath, M.J.; Zolla-Pazner, S.; Tomaras, G.D.; Alam, S.M.; Evans, D.T.; Montefiori, D.C.; Karnasuta, C.; Sutthent, R.; Liao, H.X.; DeVico, A.L.; Lewis, G.K.; Williams, C.; Pinter, A.; Fong, Y.; Janes, H.; DeCamp, A.; Huang, Y.; Rao, M.; Billings, E.; Karasavvas, N.; Robb, M.L.; Ngauy, V.; de Souza, M.S.; Paris, R.; Ferrari, G.; Bailer, R.T.; Soderberg, K.A.; Andrews, C.; Berman, P.W.; Frahm, N.; De Rosa, S.C.; Alpert, M.D.; Yates, N.L.; Shen, X.; Koup, R.A.; Pitisuttithum, P.; Kaewkungwal, J.; Nitayaphan, S.; Rerks-Ngarm, S.; Michael, N.L.; Kim, J.H. Immune-correlates analysis of an HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trial. N Engl J Med 2012, 366, 1275–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahin, U.; Derhovanessian, E.; Miller, M.; Kloke, B.-P.; Simon, P.; Löwer, M.; Bukur, V.; Tadmor, A.D.; Luxemburger, U.; Schrörs, B.; Omokoko, T.; Vormehr, M.; Albrecht, C.; Paruzynski, A.; Kuhn, A.N.; Buck, J.; Heesch, S.; Schreeb, K.H.; Müller, F.; Ortseifer, I.; Vogler, I.; Godehardt, E.; Attig, S.; Rae, R.; Breitkreuz, A.; Tolliver, C.; Suchan, M.; Martic, G.; Hohberger, A.; Sorn, P.; Diekmann, J.; Ciesla, J.; Waksmann, O.; Brück, A.-K.; Witt, M.; Zillgen, M.; Rothermel, A.; Kasemann, B.; Langer, D.; Bolte, S.; Diken, M.; Kreiter, S.; Nemecek, R.; Gebhardt, C.; Grabbe, S.; Höller, C.; Utikal, J.; Huber, C.; Loquai, C.; Türeci, Ö. Personalized RNA mutanome vaccines mobilize poly-specific therapeutic immunity against cancer. Nature 2017, 547, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Lin, A.; Xu, C.C.; Li, Z.; Liu, K.B.; Liu, B.X.; Ma, X.P.; Zhao, F.F.; Jiang, H.L.; Chen, C.X.; Shen, H.F.; Li, H.W.; Mathews, D.H.; Zhang, Y.J.; Huang, L. Algorithm for optimized mRNA design improves stability and immunogenicity. Nature 2023, 621, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niarakis, A.; Laubenbacher, R.; An, G.; et al. Immune digital twins for complex human pathologies: Applications, limitations, and challenges. npj Syst Biol Appl 2024, 10, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria-Guerra, R.E.; Nieto-Gomez, R.; Govea-Alonso, D.O.; Rosales-Mendoza, S. An overview of bioinformatics tools for epitope prediction: Implications on vaccine development. J Biomed Inform. 2015, 53, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sette, A.; Rappuoli, R. Reverse vaccinology: Developing vaccines in the era of genomics. Immunity 2010, 33, 530–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masignani, V.; Pizza, M.; Moxon, E.R. The Development of a Vaccine Against Meningococcus B Using Reverse Vaccinology. Front Immunol. 2019, 10, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serruto, D.; Bottomley, M.J.; Ram, S.; Giuliani, M.M.; Rappuoli, R. The new multicomponent vaccine against meningococcal serogroup B, 4CMenB: Immunological, functional and structural characterization of the antigens. Vaccine 2012, 30 (Suppl 2), B87–B97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skerritt, J.H. Considerations for mRNA Product Development, Regulation and Deployment Across the Lifecycle. Vaccines 2025, 13, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, E.; Wong, M.U.; Huffman, A.; He, Y. COVID-19 coronavirus vaccine design using reverse vaccinology and machine learning. Front Immunol. 2020, 11, 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skerritt, J.H.; Tucek-Szabo, C.; Sutton, B.; Nolan, T. The Platform Technology Approach to mRNA Product Development and Regulation. Vaccines 2024, 12, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.; Agrahari, V. Emerging trends and translational challenges in drug and vaccine delivery. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynisson, B.; Alvarez, B.; Paul, S.; Peters, B.; Nielsen, M. NetMHCpan-4.1 and NetMHCIIpan-4.0: Improved predictions of MHC antigen presentation by concurrent motif deconvolution and integration of MS MHC eluted ligand data. Nucleic Acids Research 2020, 48, W449–W454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Porubsky, V.; Carothers, J.; Sauro, H.M. Standards, dissemination, and best practices in systems biology. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2023, 81, 102922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jespersen, M.C.; Peters, B.; Nielsen, M.; Marcatili, P. BepiPred-2.0: Improving sequence-based B-cell epitope prediction using conformational epitopes. Nucleic Acids Research 2017, 45, W24–W29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, A.S.; Moise, L.; Mc Murry, J.A.; Wambre, E.; Van Overtvelt, L.; Moingeon, P.; Scott, D.W.; Martin, W. Activation of natural regulatory T cells by IgG Fc–derived peptide “Tregitopes”. Blood 2008, 112, 3303–3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.M. da; Myung, Y.C.; Ascher, D.B.; Pires, D.E.V. Epitope3D: A machine learning method for conformational B-cell epitope prediction. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2021, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vita, R.; Mahajan, S.; Overton, J.A.; Dhanda, S.K.; Martini, S.; Cantrell, J.R.; Wheeler, D.K.; Sette, A.; Peters, B. The Immune Epitope Database (IEDB): 2018 update. Nucleic Acids Research 2019, 47, D339–D343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleri, W.; Paul, S.; Dhanda, S.K.; Mahajan, S.; Xu, X.; Peters, B.; Sette, A. The immune epitope database and analysis resource in epitope discovery and synthetic vaccine design. Frontiers in Immunology 2017, 8, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, P.; Kim, Y.; Haste-Andersen, P.; Beaver, J.; Bourne, P.E.; Bui, H.H.; Buus, S.; Frankild, S.; Greenbaum, J.; Lund, O.; Lundegaard, C.; Nielsen, M.; Ponomarenko, J.; Sette, A.; Zhu, Z.; Peters, B. Immune epitope database analysis resource (IEDB-AR). Nucleic Acids Research 2008, 36, W513–W518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakib, A.; Sami, S.A.; Mimi, N.J.; Chowdhury, M.M.; Eva, T.A.; Nainu, F.; Paul, A.; Shahriar, A.; Tareq, A.M.; Emon, N.U.; Chakraborty, S.; Shil, S.; Mily, S.J.; Ben Hadda, T.; Almalki, F.A.; Bin Emran, T. Immunoinformatics-guided design of an epitope-based vaccine against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 spike glycoprotein. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2020, 124, 103967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, M.; Di Maio, F.; Anishchenko, I.; Dauparas, J.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Lee, G.R.; Wang, J.; Cong, Q.; Kinch, L.N.; Schaeffer, R.D.; Millán, C.; Park, H.; Adams, C.; Glassman, C.R.; De Giovanni, A.; Pereira, J.H.; Rodrigues, A.V.; van Dijk, A.A.; Ebrecht, A.C. . Baker, D. Accurate prediction of protein structures and interactions using a three-track neural network. Science 2021, 373, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; Bridgland, A.; Meyer, C.; Kohl, S.A.A.; Ballard, A.J.; Cowie, A.; Romera-Paredes, B.; Nikolov, S.; Jain, R.; Adler, J. . Hassabis, D. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with Alpha Fold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varadi, M.; Anyango, S.; Deshpande, M.; Nair, S.; Natassia, C.; Yordanova, G.; Yuan, D.; Stroe, O.; Wood, G.; Laydon, A.; Žídek, A.; Green, T.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Petersen, S.; Jumper, J.; Clancy, E.; Green, R.; Vora, A.; Lutfi, M. ;... Velankar, S. AlphaFold Protein Structure Database: Massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models. Nucleic Acids Research 2022, 50, D439–D444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLellan, J.S.; Chen, M.; Joyce, M.G.; Sastry, M.; Stewart-Jones, G.B.E.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Chen, L.; Srivatsan, S.; Zheng, A.; Zhou, T.; Graepel, K.W.; Kumar, A.; Moin, S.; Boyington, J.C.; Chuang, G.Y.; Soto, C.; Baxa, U.; Bakker, A.Q. . Kwong, P.D. Structure-based design of a fusion glycoprotein vaccine for respiratory syncytial virus. Science 2013, 342, 1192–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, C.L.; Goldsmith, J.A.; Schaub, J.M.; Di Venere, A.M.; Kuo, H.C.; Javanmardi, K.; Le, K.C.; Wrapp, D.; Lee, A.G.; Liu, Y.; Chou, C.W.; Byrne, P.O.; Hjorth, C.K.; Johnson, N.V.; Ludes-Meyers, J.; Nguyen, A.W.; Park, J.; Wang, N.; Amengor, D.; Lavinder, J.J.; Ippolito, G.C.; Maynard, J.A.; Finkelstein, I.J.; & McLellan, J.S.; McLellan, J. S. Structure-based design of prefusion-stabilized SARS-CoV-2 spikes. Science 2020, 369, 1501–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.L.; Leist, S.R.; Miller, E.H.; Zhou, L.; Powers, J.M.; Tse, A.L.; Wang, A.; West, A.; Zweigart, M.R.; Schisler, J.C.; Jangra, R.K.; Chandran, K.; Baric, R.S.; McLellan, J.S. Prefusion-stabilized SARS-CoV-2 S2-only antigen provides protection against SARS-CoV-2 challenge. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saponaro, A.; Maione, V.; Bonvin, A.M.J.J.; Cantini, F. Understanding Docking Complexes of Macromolecules Using HADDOCK: The Synergy between Experimental Data and Computations. Bio Protoc. 2020, 10, e3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez, C.; Boelens, R.; Bonvin, A.M. HADDOCK: A protein-protein docking approach based on biochemical or biophysical information. J Am Chem Soc 2003, 125, 1731–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giulini, M.; Reys, V.; Teixeira, J.M.C.; Jiménez-García, B.; Honorato, R.V.; Kravchenko, A.; Xu, X.; Versini, R.; Engel, A.; Verhoeven, S.; Bonvin, A.M.J.J. HADDOCK3: A Modular and Versatile Platform for Integrative Modeling of Biomolecular Complexes. J Chem Inf Model 2025, 65, 7315–7324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudreault, F.; Sulea, T.; Corbeil, C.R. AI-augmented physics-based docking for antibody-antigen complex prediction. Bioinformatics 2025, 41, btaf129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatahi, G.; Abdollahi, M.; Nashtahosseini, Z.; Minoo, S.; Mostafavi, M.; Saeidi, K. Designing of an efficient DC-inducing multi-epitope vaccine against Epstein Barr virus targeting the GP350 using immunoinformatics and molecular dynamic simulation. Biochemistry and Biophysics Reports 2025, 42, 101966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedotti, M.; Simonelli, L.; Livoti, E.; Varani, L. Computational docking of antibody-antigen complexes, opportunities and pitfalls illustrated by influenza hemagglutinin. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2011, 12, 226–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karplus, M.; McCammon, J.A. Molecular dynamics simulations of biomolecules. Nature Structural Biology 2002, 9, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollingsworth, S.A.; Dror, R.O. Molecular dynamics simulation for all. Neuron 2018, 99, 1129–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baruah, V.; Bose, S. Immunoinformatics aided identification of T cell and B cell-epitopes in the surface glycoprotein of 2019 n Co V. Journal of Medical Virology 2020, 92, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortese, M.; Hagan, T.; Rouphael, N.; Wu, S.-Y.; Xie, X.; Kazmin, D.; Wimmers, F.; Gupta, S.; van der Most, R.; Coccia, M.; Aranuchalam, P.S.; Nakaya, H.I.; Wang, Y.; Coyle, E.; Horiuchi, S.; Wu, H.; Bower, M.; Mehta, A.; Gunthel, C. . Pulendran, B. System vaccinology analysis of predictors and mechanisms of antibody response durability to multiple vaccines in humans. Nature Immunology 2025, 26, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakaya, H.I.; Wrammert, J.; Lee, E.K.; Racioppi, L.; Marie-Kunze, S.; Haining, W.N.; Means, A.R.; Kasturi, S.P.; Khan, N.; Li, G.M.; McCausland, M.; Kanchan, V.; Kokko, K.E.; Li, S.; Elbein, R.; Mehta, A.K.; Aderem, A.; Subbarao, K.; Ahmed, R.; Pulendran, B. Systems biology of seasonal influenza vaccination in humans. Nature Immunology 2011, 12, 786–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querec, T.D.; Akondy, R.S.; Lee, E.K.; Cao, W.; Nakaya, H.I.; Teuwen, D.; Pirani, A.; Gernert, K.; Deng, J.; Marzolf, B.; Kennedy, K.; Wu, H.; Bennouna, S.; Oluoch, H.; Miller, J.; Vencio, R.Z.; Mulligan, M.; Aderem, A.; Ahmed, R.; Pulendran, B. Systems biology approach predicts immunogenicity of the yellow fever vaccine in humans. Nature Immunology 2009, 10, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laubenbacher, R.; Niarakis, A.; Helikar, T.; An, G.; Shapiro, B.; Malik-Sheriff, R.S.; Sego, T.J.; Knapp, A.; Macklin, P.; Glazier, J.A. Building digital twins of the human immune system: Toward a roadmap. npj Digital Medicine 2022, 5, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viceconti, M.; Henney, A.; Morley-Fletcher, E. In silico clinical trials: How computer simulation will transform the biomedical industry. International Journal of Clinical Trials 2016, 3, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Song, J.; Zhang, H.; Wei, Z.; Wei, D.; Yang, G.; Demongeot, J.; Zeng, Q. A mathematical model simulating the adaptive immune response in various vaccines and vaccination strategies. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 18507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piffari, C.; Lagorio, A.; Pinto, R. Agent-based simulation for vaccination networks design and analysis: Preliminary gaps. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 2902–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federico, L.; Malone, B.; Tennøe, S.; Chaban, V.; Osen, J.R.; Gainullin, M.; Smorodina, E.; Kared, H.; Akbar, R.; Greiff, V.; Stratford, R.; Clancy, T.; Munthe, L.A. Experimental validation of immunogenic SARS-CoV-2 T cell epitopes identified by artificial intelligence. Frontiers in Immunology 2023, 14, 1265044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Hu, A.K.; Presnell, S.R.; Ford, E.S.; Koelle, D.M.; Kwok, W.W. Longitudinal single cell profiling of epitope-specific memory CD4+ T cell responses to recombinant zoster vaccine. Nature Communications 2025, 16, 6038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grifoni, A.; Weiskopf, D.; Ramirez, S.I.; Mateus, J.; Dan, J.M.; Moderbacher, C.R.; Rawlings, S.A.; Sutherland, A.; Premkumar, L.; Jadi, R.S.; Marrama, D.; de Silva, A.M.; Frazier, A.; Carlin, A.F.; Greenbaum, J.A.; Peters, B.; Krammer, F.; Smith, D.M.; Crotty, S.; Sette, A. Targets of T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus in humans with COVID-19 disease and unexposed individuals. Cell 2020, 181, 1489–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassani-Sternberg, M.; Braunlein, E.; Klar, R.; Engleitner, T.; Sinitcyn, P.; Audehm, S.; Straub, M.; Weber, J.; Slotta-Huspenina, J.; Specht, K.; Martignoni, M.E.; Werner, A.; Hein, R.; Busch, D.H.; Peschel, C.; Rad, R.; Cox, J.; Mann, M.; Krackhardt, A.M. Direct identification of clinically relevant neoepitopes presented on native human melanoma tissue by mass spectrometry. Nature Communications 2016, 7, 13404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, S.B.; Rose, C.M.; Darwish, M.; Bouziat, R.; Delamarre, L.; Blanchette, C.; Lill, J.R. Sensitive and quantitative detection of MHC-I displayed neoepitopes using a semiautomated workflow and TOMAHAQ mass spectrometry. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 2021, 20, 100108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purcell, A.W.; Ramarathinam, S.H.; Ternette, N. Mass spectrometry based identification of MHC-bound peptides for immunopeptidomics. Nature Protocols 2019, 14, 603–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrapp, D.; Wang, N.; Corbett, K.S.; Goldsmith, J.A.; Hsieh, C.L.; Abiona, O.; Graham, B.S.; McLellan, J.S. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science 2020, 367, 1260–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Cai, Y.; Zhu, H.; Peng, H.; Voyer, J.; Rits-Volloch, S.; Cao, H.; Mayer, M.L.; Song, K.; Xu, C.; Lu, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, B. Cryo-EM structure of SARS-CoV-2 postfusion spike in membrane. Nature 2023, 619, 838–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]