1. Introduction

Tomato (

Solanum lycopersicum L.) is one of the most important vegetable crops globally and is a key component of diets in the Middle East and North Africa. The value of the tomato market in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) was estimated at USD 182.63 million in 2025 and is projected to grow to USD 228.68 million by 2030, reflecting a compound annual growth rate of 4.6%. UAE tomato market is heavily dependent on imports, which supplied 76.7% of the total consumption volume in 2024 [

1].

In the region, tomato is widely cultivated in both open fields and controlled environments; however, production is severely constrained by extreme temperatures, limited arable land, and acute freshwater scarcity. Open-field tomato yield in the region ranged 4 to 5 kg/m2 with low water productivity between 3 to 6 kg/m3 of water [

2]. Meanwhile, the average yield in a low-medium tech cooled hydroponic greenhouses manage by the growers reported varies from 9-17 kg/m2 [

3,

4,

5,

6] in the region. While the range could be due to different crop varieties and production management, plant density also varies. Published hydroponic trials in modest-technology soilless systems report ~2–5 kg/plant (NFT/DFT/perlite) with occasional higher outputs under substrate-bag plastic houses. As a result its safe to adopt average 3.5 kg/plant as a conservative single-crop range for low/medium-tech hydroponics in hyper-arid regions [

7,

8,

9].

However, in cooled greenhouse the limiting factor is still water. Study in the region report water productivity of cooled hydroponics greenhouses as low as 8-9 kg/m3 which most consume by cooling system (pad and fan) [

10].

As a result, production has largely shifted to cooled greenhouses and hydroponic systems. While hydroponics significantly reduces irrigation water consumption, cooled greenhouses impose new limitations: evaporative cooling systems can consume three to four times more water than is actually used for plant growth, and the cooling demand requires large amounts of electricity. [

10,

11]. These factors increase production costs and reduce system efficiency during the hot summer months, when high humidity and elevated temperatures further limit cooling effectiveness.

Studies from the GCC region report that cooling costs account for a disproportionately high share of production expenses, leading to high overall production costs and a loss of competitiveness of locally grown tomatoes compared to cheaper imports. Under such market and resource pressures, many growers prefer to suspend tomato production during June and July, when inputs are highest and profit margins lowest. [

12,

13]. This not only raises production costs but also contributes to a high carbon footprint, limiting the long-term sustainability of the system.

To address these challenges, the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) has developed an integrated five-technology package designed to optimize crop production in arid regions. The system combines:

Insect-proof net houses that provide natural ventilation and reduce pest pressure, minimizing the need for chemical control and energy-intensive cooling.

Closed hydroponic systems that recycle nutrient solutions, reducing water and fertilizer losses.

Root Zone Cooling (RZC) technology that maintains optimal root temperatures and enhances plant physiological performance under high ambient heat.

Cost-effective solar-powered systems — a 100% off-grid setup for irrigation and an AC/DC hybrid solar energy system for root zone cooling — ensuring reliable, renewable power with minimal operational costs.

Ultra-Low Energy Drippers (ULED) that deliver precise irrigation at extremely low pressure, maximizing water-use efficiency.

Together, these integrated technologies form a sustainable production model that enables crop cultivation for 7–8 months of the year under the region’s harsh conditions, achieving substantial improvements in both water and energy efficiency while maintaining high crop productivity [

10,

14].

Another major constraint for sustainable crop production in the UAE is water quality. Desalination remains the primary source of irrigation water, yet conventional desalination plants are costly and energy intensive [

15].

Small solar RO units providing suitable water quality with low cost, rapid deployment, and resilience [

16,

17]. They are especially valuable for hydroponic systems, which require little but high-quality water. Centralized RO plants meet large demands but have high energy, brine, and emission impacts [

16,

17]; solar integration adds cost and complexity[

18]. Advanced treatments raise expenses. Small units are flexible, sustainable, and site-specific, while large systems serve urban demand; choice depends on local context [

19].

In this study, a low-cost reverse osmosis (RO) desalination unit was upgraded to operate with a hybrid solar energy system and tested as part of the production setup. The system provided irrigation water of suitable quality for hydroponics while reducing dependence on conventional energy sources and lowering overall consumption.

Despite advances in system design, varietal response remains a critical factor in optimizing yield and water use efficiency (WUE) under these novel production conditions. Tomato varieties differ significantly in their tolerance to heat, salinity, and closed-loop hydroponic conditions. Comparative evaluation of varieties under integrated solar-powered hydroponics, root zone cooling, and desalination systems is therefore essential to identify cultivars most suitable for arid-zone controlled environments.

This study in Al Dhaid, UAE, evaluated six tomato varieties under an integrated system combining a five-technology package and a cost-effective solar-powered RO desalination unit. It aimed to assess varietal differences in yield and water use efficiency (WUE) under solar-powered closed hydroponic conditions. It was hypothesized that tomato varieties differ in adaptability, yield, and WUE under heat, salinity, and recirculating nutrient conditions, and that the low-cost solar-powered RO unit would provide sufficient water quality and quantity throughout the production period. Findings will guide the development of sustainable, resource-efficient horticultural systems for arid regions.

2. Materials and Methods

The experiment was conducted at the Ministry of Climate Change and Environment research station in Al Dhaid, United Arab Emirates (25°17′N, 55°52′E), a hyper-arid region characterized by high solar radiation, limited rainfall (<100 mm annually), and summer temperatures exceeding 45 °C. The trial was implemented during the mild winter season (October–May), which represents the typical production window for vegetable crops under net-house systems in the region.

The study was carried out in a solar-powered closed hydroponic system established inside an insect-proof net house. The production system integrated several innovative technologies:

Net house: A steel-frame structure covered with insect-proof netting to reduce pest infestation and facilitate natural ventilation.

Hydroponic system: Closed soilless cultivation using perlite substrate in polystyrene pots. Nutrient solution was delivered through drip irrigation with ultra-low-pressure emitters, and drainage water was fully recirculated.

Root zone cooling: A hybrid AC/DC cooling unit was connected to the nutrient solution tanks to maintain the root zone temperature between 22–24 °C during hot hours of the day. Cooling was powered primarily by solar energy, with automatic switching to grid power when solar availability was insufficient.

A medium-capacity reverse osmosis (RO) system with a nominal production capacity of 400 gallons per day (GPD) - equivalent to 1514 Litter per day -was developed in collaboration with a local factory. The unit was equipped with two parallel thin-film composite membranes (200 GPD each) designed for high total dissolved solids (TDS) feed water. Pre-treatment included:

A 25 × 4.5-inch yarn sediment cartridge fitted in a 20-inch housing with 1-inch brass connection

A 10-inch polyphosphate filter to inhibit scaling and extend membrane life.

A multistage filtration includes 10 inch Yarn sediment, powder carbon and block carbon

This multi-stage configuration ensured the removal of particulate matter, reduction of hardness-related scaling, and effective rejection of dissolved salts and contaminants by the RO membranes. The treated water was subsequently used in all fertigation and experimental irrigation treatments. The well water pumped to a tank which fed the RO unit with a 0.5hp pump. The pump and RO unit stop/start controlled by a floating swich inside the irrigation tank.

A battery-less hybrid PV-grid system was deployed using a 1.4 kW hybrid inverter with integrated MPPT and solar-priority control. The PV array (1.5 kWp) was sized to offset the continuous ~650 W process load of the RO unit, which included two 24 V DC pumps and a 0.5 Hp AC pump. The inverter blended PV with grid input in real time, with PV prioritized and the grid automatically supplying any shortfall.

A similar hybrid configuration was also employed to operate a 1.5-ton air-conditioning unit for root zone cooling (RZC) in controlled-environment agriculture, demonstrating the scalability of this design from moderate loads such as RO systems to more energy-intensive applications. Standard DC/AC over-current protection, surge protection, isolation, and earthing were implemented to ensure safe and reliable operation.

The irrigation system powered by a 100% off-grid solar system. The system consisted of a 450W pump runs with a two 55Amh batteries and solar array with 450W panels.

Six commercial tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) varieties commonly used in the Arabian Peninsula were tested. Seeds were germinated in rockwool cubes and transplanted into perlite bags at a density of 2.5 plants/m². Standard training (single stem) and pruning practices were followed throughout the cropping period.

The experiment was laid out in a randomized complete block design (RCBD) with four replications. Each block contained all six tomato varieties (V1–V6), arranged in a randomized but spatially balanced sequence to minimize positional bias within the net house. Each replication consisted of a plot of 50 plants per variety, arranged in double rows with 1.6 m spacing between rows and 0.25 m between plants within rows.

Table 1.

Study layout inside the net house-RCBD with 4 replications.

Table 1.

Study layout inside the net house-RCBD with 4 replications.

| B1 |

V6 |

V5 |

V4 |

V3 |

V2 |

V1 |

| B2 |

V1 |

V6 |

V5 |

V4 |

V3 |

V2 |

| B3 |

V2 |

V1 |

V6 |

V5 |

V4 |

V3 |

| B4 |

V3 |

V2 |

V1 |

V6 |

V5 |

V4 |

Nutrient solution was prepared from stock solutions containing calcium nitrate (Ca(NO₃)₂), magnesium sulfate (MgSO₄·7H₂O), and NPK (12-12-36 + TE). Trace elements were supplied using a commercial micronutrient mix. The electrical conductivity (EC) of the irrigation solution was maintained according to crop growth stage:

Seedling stage: 1.5 dS/m

Vegetative stage: 2.0 dS/m

Flowering stage: 2.3 dS/m

Fruiting stage: 2.5–3.5 dS/m

The pH of the solution was adjusted to 5.8–6.0 using nitric acid. Irrigation scheduling was based on crop evapotranspiration, with automatic control through a fertigation unit. Drainage water was recirculated after monitoring and adjustment of EC and pH. Data Collection includes the following:

Yield: Fruits were harvested, weighed, and expressed as kg/plot, kg/plant and kg/m² of harvested area. Marketable yield (free of cracks, blossom end rot, or pest damage) and total yield were recorded separately.

Water use: Total irrigation volume in net-house was recorded using flow meters. To calculate water use efficacy, this figure divided by number of plots.

Water use efficiency (WUE): Calculated as the ratio of total marketable yield (kg) to total irrigation water applied (m³).

3. Results

The solar-powered RO unit was tested twice, one month apart, to assess desalination efficiency and stability under continuous arid-field operation. Results confirmed consistent performance, producing irrigation-grade water for hydroponics. The RO system reduced dissolved salts and ions by 75–82%, maintaining high water quality (

Table 2).

TDS decreased from 632.4 → 130.2 ppm initially and to 136.8 ppm a month later, showing <2% variation. Minor changes in sodium, chloride, and EC reflected feedwater or temperature fluctuations, not membrane decline. Highest removals were for Ca²⁺ (82%), Na⁺ (80%), Cl⁻ (79%), and SO₄²⁻ (78%), with lower efficiency for K⁺ (55%), typical of monovalent ions.

The RO unit operated at approximately 50% recovery, producing permeate equal to about half of the inlet flow and generating a brine stream of comparable volume. In this trial, the concentrate (brine) was collected in an open-top reservoir for evaporation, thereby avoiding discharge to soils or drains.

The low-cost solar-powered RO system operated stably and efficiently, delivering consistent, high-quality irrigation water throughout the tomato production season while reducing dependence on freshwater sources.

3.1. RO water and low PH of irrigation water

Toward the end of the growing season, a noticeable decline in the pH of the irrigation solution was observed, reaching values close to 4.0 after one week of system flushing. This condition was traced to the characteristics of the RO-treated water rather than to system malfunction. The reverse osmosis process removed most of the bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻) ions—approximately 80% reduction according to the analysis—thereby eliminating the natural buffering capacity of the water. With little to no alkalinity remaining, even minor inputs of dissolved carbon dioxide, root respiration, or organic acid formation within the closed hydroponic loop led to rapid acidification [

26]. In recirculating systems, the gradual loss of bicarbonate buffering capacity results in increased chemical instability and vulnerability to acidification [

27]. As plant and microbial respiration peak under high ambient heat, the release of CO₂ and organic acids further drives pH reduction, particularly when the solution has near-zero alkalinity typical of RO-treated water [

28]. In addition, nitrification processes within the rhizosphere and microbial biofilms contribute to proton accumulation, compounding acidification under low-buffer conditions [

29]. These concurrent chemical and biological factors collectively explain the sharp end-of-season pH decline. To stabilize pH, two practical measures are recommended: (1) blending approximately 10-20% of untreated well water with RO permeate to restore moderate alkalinity, and (2) adding a controlled dose of potassium bicarbonate (KHCO₃) to the irrigation tank to raise alkalinity to about 40–60 mg/L as CaCO₃ [

30]. After the low pH was observed in April, the nutrient tank was refilled with municipal freshwater, while the solar-powered RO unit continued supplying water to replace daily system losses. This is in addition of flushing and cleaning the system each two weeks. This combination helped re-establish alkalinity and stabilize water quality under high ambient temperatures toward the end of the production cycle.

3.2. Tomato Yield

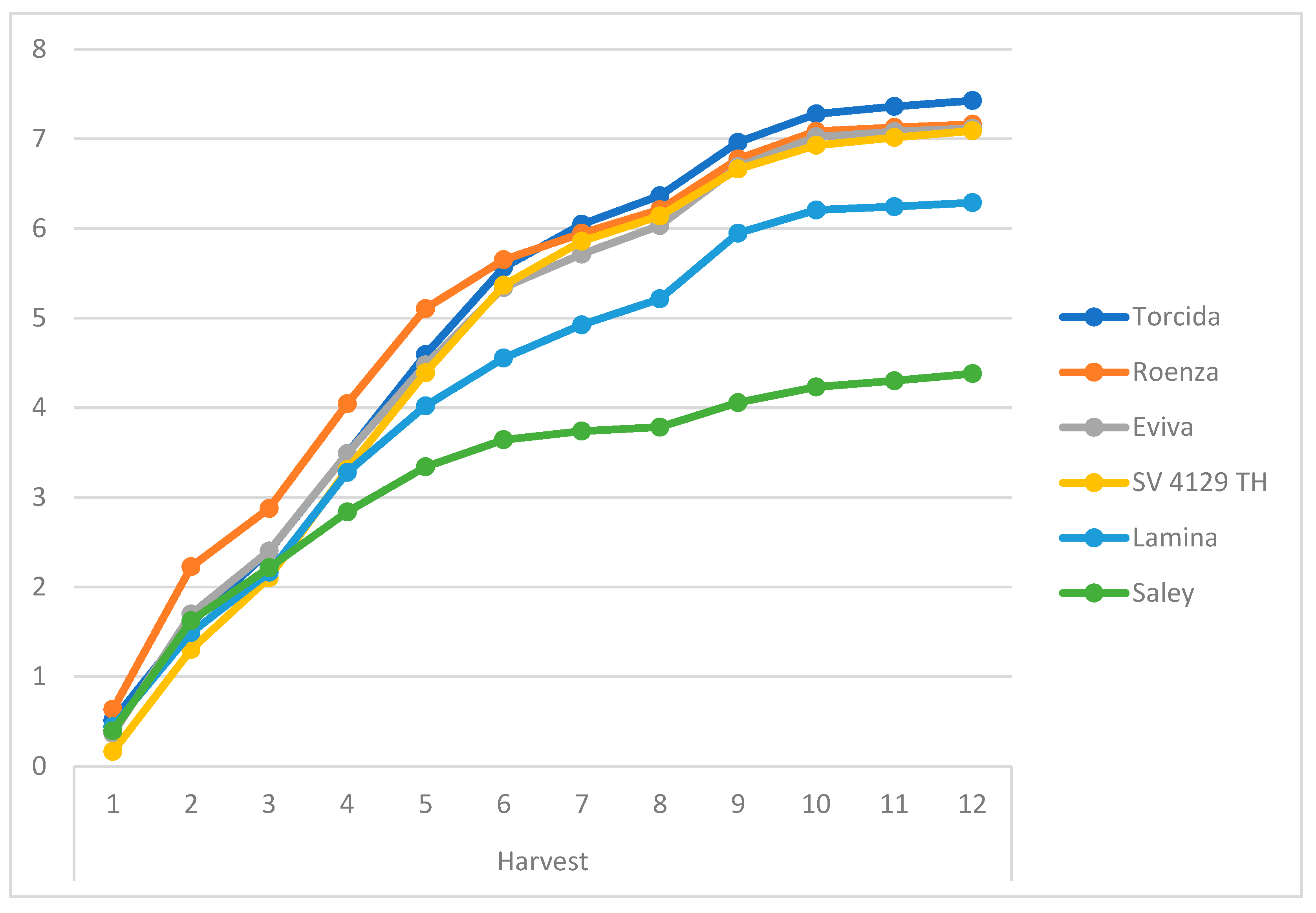

The experiment planed on 12 November 2024, the first harvest was on 2nd March 2015, and the 12th and last harvest was on 28 April 2025. Analysis of variance for yield per harvest area (

Table 3) showed that variety, harvest, and their interaction (Variety × Harvest) had highly significant effects (p < 0.001) on tomato yield.

Replication effects were not significant, confirming consistent growing conditions across the net house. The overall coefficient of variation (23%) indicated acceptable experimental precision for multi-harvest hydroponic yield measurements. The significant interaction term demonstrates that varietal performance varied across harvests, reflecting genotypic differences in yield persistence and response to changing environmental conditions over the production period.

Mean yields across all harvests are presented in

Table 4. Significant differences were observed among the six tomato varieties grown under the solar-powered closed hydroponic system. Torcida, Roenza, Eviva, and SV4129TH formed the top-yielding group, producing between 0.619–0.591kg/m²/harvest. Lamina yielded moderately 0.524 kg/m2/harvest, while Saley was the lowest performer 0.365 kg/m2/harvest. The low standard error (± 0.018 kg m⁻²) and LSD (0.051 kg m⁻²) confirm the consistency of varietal differences across replications. Overall, Torcida exhibited the highest mean yield and stable fruiting, indicating strong adaptability to the recirculating hydroponic environment.

Figure 1illustrates the cumulative yield of six tomato varieties across twelve harvests under. Cumulative yield increased rapidly up to the fifth harvest and then gradually levelled off toward the end of the cycle. Torcida, SV 4129 TH, Roenza, and Eviva achieved the highest final yields (above 7 kg/m²), while Lamina and Saley showed lower and earlier yield plateaus.

3.3. Percentage of Marketable Fruits

The percentage of marketable fruits differed significantly among tomato varieties (F₍5,49.49₎ = 24.28, p < 0.001). Torcida recorded the highest mean marketability (66.3 ± 1.76%), followed by Eviva , SV 4129 TH, Roenza, and Lamina, which formed an intermediate statistical group. Saley had the lowest marketable proportion (41.2 ± 1.76%) and was significantly inferior to all other varieties (p < 0.001, Sidak adjustment) (

Table 5). These results indicate that Torcida maintained superior fruit quality under the solar-powered closed hydroponic system, whereas Saley suffered from the greatest losses of unmarketable fruits.

Harvest timing also had a pronounced effect on marketable percentage (F₍11,101.49₎ = 128.02, p < 0.001). The proportion of marketable fruits declined markedly as the season progressed:

Early harvests (H1–H3): consistently high marketability (> 85–90%), reflecting optimal fruit quality.

Mid-season harvests (H4–H7): moderate decline to about 60–70%, coinciding with reduced plant vigor and increasing fruit defects.

Late harvests (H8–H12): sharp reduction to 15–30% due to fruit cracking, blossom-end rot, pest damage, and physiological aging.

This consistent downward trend demonstrates that, despite controlled environmental conditions and root-zone cooling, fruit quality and marketability were strongly affected by plant age and cumulative stress over time.

3.4. Tomato Water and Fertilizer use efficiency:

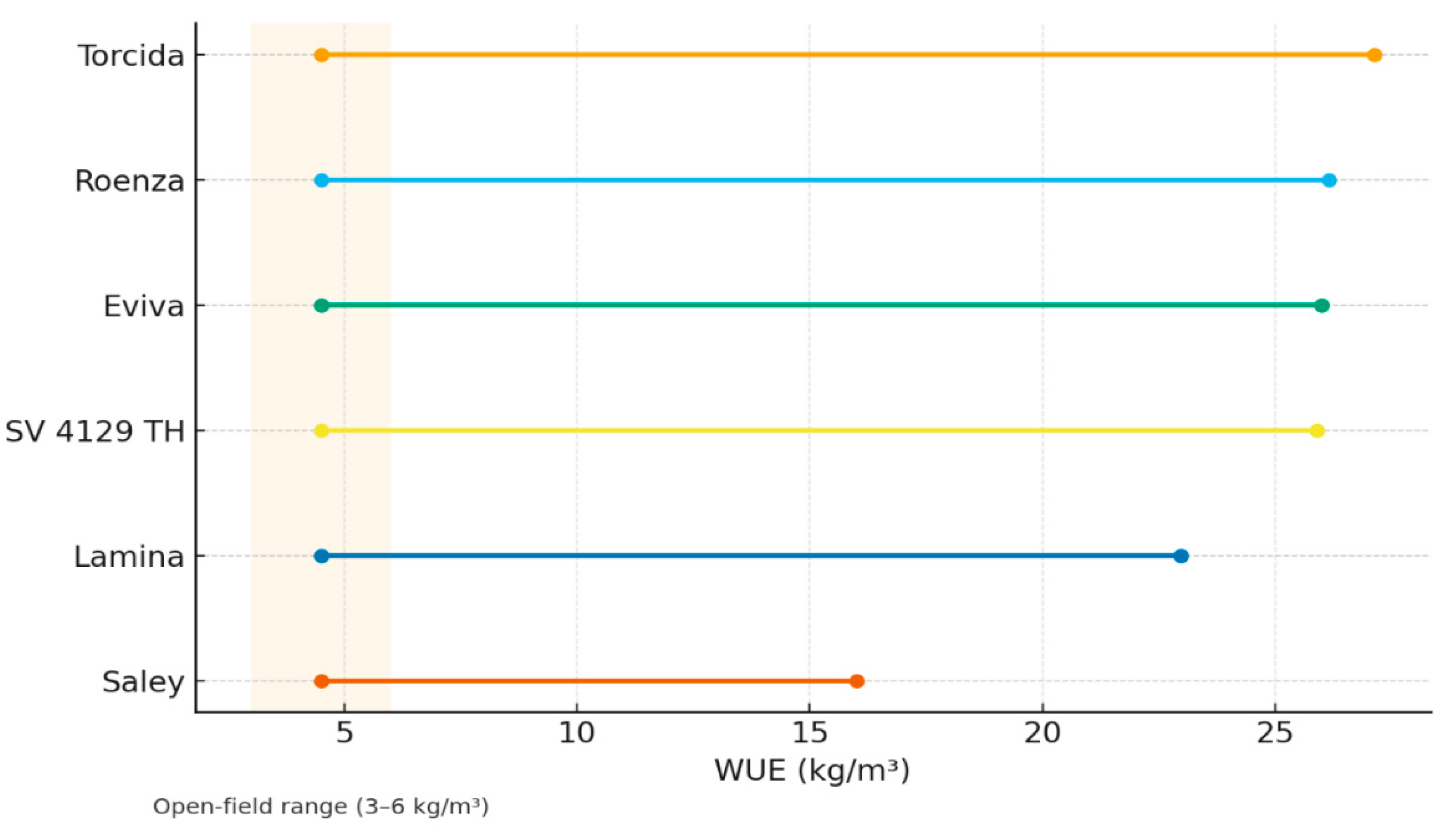

The total water consumed during production period was 63m3. Mean WUE varied significantly among tomato varieties (F(5,15)=25.59, p<0.001). The highest efficiency was recorded in Torcida (27.1 kg/m³), followed closely by Roenza, Eviva, and SV 4129 TH (25.9–26.2 kg/m³). Lamina showed moderate performance (23.0 kg/m³), while Saley had the lowest WUE (16.0 kg/m³) (

Table 6). Tukey’s HSD test grouped the varieties into three overlapping subsets: Torcida formed the top tier, Lamina the intermediate, and Saley the lowest, whereas Roenza, Eviva, and SV 4129 TH did not differ significantly from either of the upper two groups.

Throughout the tomato production season, the entire net house consumed a total of 26.25 kg of calcium nitrate, 27.4 kg of NPK (12-12-36), and 13 kg of magnesium sulphate. These fertilizers were prepared in concentrated stock solutions and injected automatically through the fertigation system, ensuring uniform nutrient distribution. The total quantities were evenly divided among all plots -67.31 kg/plot/season or 2.8kg/plot/season- providing consistent nutrient supply across treatments and maintaining balanced fertigation throughout the cropping period.

Table 7 shows significant varietal differences in fertilizer use efficiency. Torcida achieved the highest FUE, followed by Roenza, Eviva, and SV 4129, while Lamina and Saley recorded lower efficiencies.

3.5. Estimated cost of irrigation water using RO

Including the annual share of the farm well and pump energy (500 AED ≈ 136 US

$), the total yearly cost of the solar-powered RO system reached 595 US

$ after accounting for all capital and maintenance expenses including cost of brakish water at 1.1 AED/m3 [

31](

Table 7). With a production capacity of 1,550 L/day (≈ 565.75 m³/year), the updated cost of desalinated water was 1.05 US

$/m³.

Table 8.

Estimated Cost of RO-Treated Water Production.

Table 8.

Estimated Cost of RO-Treated Water Production.

| Item |

Total Cost (US$) |

Lifespan (Years) |

Annualized Cost (US$/Year) |

| RO Unit |

490 |

10 |

49 |

| 0.5 HP Pump |

120 |

5 |

24 |

| Solar Power System |

730 |

5 |

146 |

| RO Maintenance |

70 |

1 |

70 |

| Well & Pump Energy Share |

- |

- |

136 |

| Cost of Brackish Water |

- |

- |

170 |

| Total Annual Cost |

|

|

595 |

| RO Capacity |

|

|

1,550 L/day= 565.75 m³ /year |

| Cost of RO Water |

|

|

1.05 US$/m³ |

Based on the October 2025 tariff for commercial and industrial consumers in the UAE, the total water cost—including fuel surcharge (1.1 D/m³) and 5% VAT—ranged from 9.3 to 11.8 D/m³ (≈ 2.52–3.20 US

$/m³), depending on consumption level [

32]. In comparison, the solar-powered RO system produced irrigation-grade water at only 1.05 US

$/m³, demonstrating a 58% - 68% reduce in cost per m3 which providing more cost-effective and sustainable solution for controlled-environment agriculture.

4. Discussion

Both study hypotheses were supported. Tomato varieties exhibited statistically significant differences in adaptability, yield, and water-use efficiency (WUE) under the integrated solar-powered closed hydroponic system. The effects of Variety and Variety × Harvest were highly significant (p < 0.001), confirming a strong genotypic influence on performance. Among the cultivars, Torcida consistently achieved the highest mean per-harvest yield (0.619 kg/m²/ harvest) and WUE (27.1 kg/m³), followed by Roenza, Eviva, and SV4129 TH, which formed a statistically similar second tier; Lamina was intermediate, and Saley recorded the lowest performance. These findings are consistent with previous studies demonstrating that cultivar genetics and adaptability to hydroponic environments influence yield and water efficiency [

33,

34,

35,

36]. Such genotype-specific responses highlight the importance of selecting cultivars suited to closed systems in arid environments where water conservation is essential.

The solar-powered reverse osmosis (RO) unit operated reliably throughout the production period, maintaining ~75–82% ion reduction and stable permeate TDS (≈130–137 mg/L) across two verification points one month apart, indicating consistent desalination performance under field conditions. Stable water quality was critical for maintaining nutrient balance and plant growth within the closed system. These findings align with reports that RO-based water management systems improve irrigation quality and reduce operational costs [

35,

37]. In this study, the solar-assisted RO produced irrigation water at approximately 1.05 US

$/m³, which is substantially lower than the prevailing utility tariffs (2.52–3.20 US

$/m³), demonstrating the economic feasibility of decentralized desalination for controlled-environment agriculture.

Compared with regional open-field benchmarks (4–5 kg/m² yield; 3–6 kg/m³ WUE), the integrated system achieved clear performance gains: leading cultivars exceeded 7 kg/m² cumulative yield, and WUE reached ~26–27 kg/m³. Similar improvements have been reported in closed hydroponic systems, where controlled environments enhance resource-use efficiency and yield stability [

38,

39,

40]. Compared to the typical cooled hydroponic greenhouse in the region with 3.5 kg/plant yield and 8 kg/m³ water productivity, the integrated solar-powered closed hydroponic–RO system achieved comparable yield performance while using water up to three times more efficiently and significantly reducing dependence on grid electricity and conventional cooling systems.

The combination of insect-proof netting (reduced pest pressure and improved ventilation), closed hydroponics (minimal drainage losses), ultra-low-energy drip irrigation (precise nutrient delivery), and root-zone cooling (temperature regulation during high-heat hours) collectively contributed to yield stability and improved WUE across twelve harvests [

10].

The observed variation in marketable fruit percentage among tomato genotypes and harvest times is consistent with literature linking cultivar traits and physiological disorders to fruit quality. The superior performance of Torcida (66.3 %) versus the poor showing of Saley (41.2 %) underscores inherent genetic differences in tolerance to stress, nutrient transport, and tissue integrity. Likewise, the steep decline in marketability from early (85–90 %) to late harvests (15–30 %) reflects cumulative physiological deterioration, which is well documented: fruit cracking, blossom-end rot (BER), and other defects increase with plant age, imbalanced calcium distribution, and environmental stress (e.g. heat, moisture fluctuation) [

41,

42]. With plant aging, nutrient uptake efficiency—especially of calcium, magnesium, and boron—declines, reducing fruit structural integrity and increasing cracking and blossom-end rot [

43]. This age-related nutrient limitation, combined with cumulative stress, leads to lower fruit quality and marketability.

Similar patterns have been reported in cooled greenhouses of arid regions, where fruit quality declines with plant age despite temperature control. Studies indicate that increased vapor pressure due to greenhouse warming, along with cumulative physiological stress, exacerbates fruit cracking and blossom-end rot under cooling systems [

44,

45].

Figure 2.

Water-use efficiency (WUE) of six tomato varieties under solar-powered hydroponics versus open-field range (3–6 kg/m³). All varieties showed major gains; Torcida reached the highest (~27 kg/m³).

Figure 2.

Water-use efficiency (WUE) of six tomato varieties under solar-powered hydroponics versus open-field range (3–6 kg/m³). All varieties showed major gains; Torcida reached the highest (~27 kg/m³).

A notable operational observation was late-season acidification (solution pH ≈ 4.0 after flushing), resulting from near-zero alkalinity in RO permeate due to ≈80% HCO₃⁻ removal. The absence of buffering capacity made the system sensitive to CO₂ dissolution, organic acid accumulation, and nitrification-related proton release. This issue is controllable through blending approximately 10% untreated well water with permeate or adding potassium bicarbonate to maintain alkalinity at 40–60 mg/L CaCO₃, thereby stabilizing pH within the optimal 5.8–6.2 range. Previous studies emphasize that alkalinity management improves nutrient availability and prevents nutrient imbalances [

36,

46,

47]. Regular monitoring of EC, pH, and alkalinity should therefore be incorporated into routine operation protocols.

The RO unit operated at approximately 50% recovery, producing permeate equal to half of the inlet flow and generating a brine stream of comparable volume. The brine was collected in an open-top evaporation reservoir, preventing discharge to soil or drainage systems. Future evaluations should document annual brine production, evaporation rates, and salt residue handling to ensure environmental compliance and to strengthen the sustainability assessment of the system.

Based on performance, Torcida is recommended as the most suitable cultivar under the tested conditions, with Roenza, Eviva, and SV4129 TH as potential alternatives depending on seed availability and cost. The correlation among WUE, yield, and fertilizer-use efficiency (FUE) suggests that once fertigation uniformity is ensured, physiological traits such as canopy architecture and fruit-load distribution primarily determine efficiency. Additional improvements are expected from growth-stage-specific EC adjustments and targeted K⁺/micronutrient management during peak fruiting, given the low RO rejection of K⁺ and its critical role in fruit quality.

In summary, this study demonstrates that solar-powered closed hydroponic systems can significantly enhance tomato yield and water productivity while lowering water supply costs through low-energy desalination. Cultivar-specific optimization—particularly the use of Torcida—and precise nutrient and pH control can make such systems a technically and economically viable model for sustainable tomato production in arid regions [

38,

48,

49].

5. Conclusions

The integrated solar-powered RO–hydroponic net house proved efficient, reliable, and high-performing for tomato production in arid conditions. Torcida recorded the highest yield (0.619 kg /m²/harvest), water-use efficiency (27.1 kg/m³), and marketable fruit percentage (66.3%), demonstrating strong adaptability and superior fruit quality under closed hydroponic conditions. The RO unit operated stably with 75–82% salt removal, producing irrigation water at only 1.05 US$/m³—about 60% cheaper than utility rates. Compared with open-field benchmarks, yield and WUE improved nearly tenfold. Minor late-season pH decline from low alkalinity in RO water was easily corrected by blending ~20% fresh municipality water. Overall, the integrated system provides a practical, low-cost, and scalable model for sustainable, high-quality vegetable production in hyper-arid regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Arash Nejatian and Abdul Aziz Niane; methodology, Arash Nejatian, Abdul Aziz Niane, and Mohhamed Makkawi; validation and formal analysis, Khaled Al-Sham'aa; data curation, Shamma Abdulla Rahma Al Shamsi, Tahra Saeed Ali Mohamed Al Naqbi, Haliema Yousif Hassan Ibrahim, Jassem Essa Juma, Mohhamed Makkawi, Arash Nejatian, and Abdul Aziz Niane; writing—original draft preparation, Arash Nejatian and Abdul Aziz Niane; writing—review and editing, Arash Nejatian, Abdul Aziz Niane, Mohhamed Makkawi, and Khaled Al-Sham'aa. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research activities were conducted by ICARDA’s Arabian Peninsula Regional Program (APRP), with generous financial support from the Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development (AFESD), the Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development (KFAED), and the GCC the General Secretariat of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). The authors gratefully acknowledge the valuable contributions of these donors to the success of the project.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Due to institutional data management policies and ongoing related experiments, the full dataset is not publicly archived. Summary data supporting the findings of this study are included within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the close collaboration and support provided by the Ministry of Climate Change and Environment (MOCCAE) of the United Arab Emirates, which also hosts ICARDA’s Arabian Peninsula Regional Program (APRP) office in Ajman.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Mordor Intelligence. UAE Tomato Market Size & Share Analysis - Growth Trends and Forecast (2025 - 2030) [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 26]. Available from: source: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/uae-tomato-market.

- ICARDA. The Agricultural Sector in Qatar: Challenges and Opportunities [Internet]. Aleppo: ICARDA; 2010. 452 p. Available from: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11766/67649.

- Mostafa AT. POTENTIAL OF PROTECTED AGRICULTURE AND HYDROPONICS FOR IMPROVING THE PRODUCTIVITY AND QUALITY OF HIGH-VALUE CASH CROPS IN QATAR. In: The Agricultural Sector in Qatar: Challenges and Opportunities [Internet]. ICARDA; 2010. p. 452. Available from: https://mel.cgiar.org/reporting/downloadmelspace/hash/1763f4d185bb28e077fb3b5ae1ec55a2/v/168aaaea10fa729362785492ffa2f6d4.

- Al-Khateeb SA, Zeineldin FI, Elmulthum NA, Al-Barrak KM, Sattar MN, Mohammad TA, et al. Assessment of Water Productivity and Economic Viability of Greenhouse-Grown Tomatoes under Soilless and Soil-Based Cultivations. Water [Internet]. 2024 Mar 28;16(7):987. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4441/16/7/987. [CrossRef]

- Albaho MS, Al-Mazidi K. EVALUATION OF SELECTED TOMATO CULTIVARS IN SOILLESS CULTURE IN KUWAIT. Acta Hortic [Internet]. 2005 Oct;(691):113–6. Available from: https://www.actahort.org/books/691/691_11.htm. [CrossRef]

- ICARDA. ICARDA-APRP Annual Report 2011-2012. Awadeh F, Nejatian A, editors. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ortega WM, Martínez V, Nieves M, Simón I, Lidón V, Fernandez-Zapata JC, et al. Agricultural and Physiological Responses of Tomato Plants Grown in Different Soilless Culture Systems with Saline Water under Greenhouse Conditions. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2019 May 1;9(1):6733. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-42805-7.

- Sánchez-del Castillo F, Moreno-Pérez E del C, Pineda-Pineda J, Aragón-Ramírez LA. Nutrient dynamics and yield of tomato with different fertilizer sources and nutrient solution concentrations. Rev Chapingo Ser Hortic [Internet]. 2025;31. Available from: https://revistas.chapingo.mx/horticultura/?section=articles&subsec=issues&numero=315&articulo=2837.

- Cardoso FB, Martinez HEP, Silva DJH da, Milagres C do C, Barbosa JG. Yield and quality of tomato grown in a hydroponic system, with different planting densities and number of bunches per plant. Pesqui Agropecuária Trop. 2018;48(4):340–9.

- Nejatian A, Niane AA, Nangia V, Al Ahmadi AH, Naqbi TSAM, Ibrahim HYH, et al. Enhancing Controlled Environment Agriculture in Desert Ecosystems with AC/DC Hybrid Solar Technology. Int J Energy Prod Manag [Internet]. 2023 Jun 16;8(2):107–13. Available from: https://iieta.org/journals/ijepm/paper/10.18280/ijepm.080207. [CrossRef]

- A.T. M, Al-Shankiti A, Nejatian A. Potential of protected agriculture to enhance water and food security in the Arabian Peninsula. In: El-Beltagy A, Saxena MC, editors. Meeting the challenge of sustainable development in drylands under changing climate - moving from global to local, Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Development of Drylands [Internet]. International Dryland Development Commission (IDDC); 2010. p. 377–83. Available from: https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/20163289046.

- Fatnassi H, Zaaboul R, Elbattay A, Molina-Aiz FD, Valera DL. Protected agriculture systems in the UAE: challenges and opportunities. Acta Hortic [Internet]. 2023 Oct;(1377):495–502. Available from: https://www.actahort.org/books/1377/1377_60.htm. [CrossRef]

- Hirich A, Choukr-Allah R. Water and Energy Use Efficiency of Greenhouse and Net house Under Desert Conditions of UAE: Agronomic and Economic Analysis. In 2017. p. 481–99. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-51856-5_28.

- Nejatian A, Rawahy M Al, Niane AA, Ahmadi AH Al, Nangia V, Dhehibi B. Renewable Energy and Net House Integration for Sustainable Cucumber Crop Production in the Arabian Peninsula: Extending Growing Seasons and Reducing Resource Use. J Sustain Res [Internet]. 2024;6(3):e240038. Available from: https://sustainability.hapres.com/htmls/JSR_1612_Detail.html. [CrossRef]

- Ahamad T, Parvez M, Lal S, Khan O, Yahya Z, Saeed Azad A. Assessing Water Desalination in the United Arab Emirates: An Overview. In: 2023 10th IEEE Uttar Pradesh Section International Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Computer Engineering (UPCON) [Internet]. IEEE; 2023. p. 1373–7. Available from: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10434292/.

- Bdour M, Dalala Z, Al-Addous M, Kharabsheh AAA, Al-Khzouz H. Mapping RO-Water Desalination System Powered by Standalone PV System for the Optimum Pressure and Energy Saving. Appl Sci. 2020;10(6):2161. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed FE, Hashaikeh R, Hilal N. Solar Powered Desalination – Technology, Energy and Future Outlook. Desalination. 2019;453:54–76. [CrossRef]

- Alsarayreh AA, Al-Obaidi MA, Ruiz-García A, Patel R, Mujtaba IM. Thermodynamic Limitations and Exergy Analysis of Brackish Water Reverse Osmosis Desalination Process. Membranes (Basel). 2021;12(1):11. [CrossRef]

- Raninga M, Mudgal A, Patel V, Patel J. Advanced Exergy Analysis of Cascade Rankine Cycle-Driven Reverse Osmosis System. Energy Technol. 2024;12(3). [CrossRef]

- Mattson N. Fertilizer and water quality management for hydroponic crops [Internet]. 2022. Available from: https://hos.ifas.ufl.edu/media/hosifasufledu/documents/pdf/in-service-training/ist31188/IST31188---8.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Singh H, Bruce D. Electrical Conductivity and pH Guide for Hydroponics [Internet]. 2016. Available from: https://extension.okstate.edu/fact-sheets/print-publications/hla/electrical-conductivity-and-ph-guide-for-hydroponics-hla-6722.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Saskatchewan. Water Quality in Greenhouses [Internet]. 2024. Available from: https://www.saskatchewan.ca/business/agriculture-natural-resources-and-industry/agribusiness-farmers-and-ranchers/crops-and-irrigation/horticultural-crops/greenhouses/water-quality-in-greenhouses?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- University of Georgia. Testing the Water [Internet]. Horticulture Physiology. 2012. Available from: https://hortphys.uga.edu/research/fertilization-in-greenhouses-an-introduction/testing-the-water/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Sánchez E, Di Gioia F, Ford T, Berghage R, Flax N. Hydroponics Systems: Nutrient Solution Programs and Recipes [Internet]. PennState Extension. 2024. Available from: https://extension.psu.edu/hydroponics-systems-nutrient-solution-programs-and-recipes.

- Robbins JA. Irrigation Water for Grenhouses and Nurseries [Internet]. 2018. Available from: https://www.uaex.uada.edu/publications/pdf/FSA-6061.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Doreen. How Do I Treat My Water Source? [Internet]. Plant-prod: High Productivity Plant Nutrition. 2022. Available from: https://www.plantprod.com/news/water-quality/.

- Sambo P, Nicoletto C, Giro A, Pii Y, Valentinuzzi F, Mimmo T, et al. Hydroponic Solutions for Soilless Production Systems: Issues and Opportunities in a Smart Agriculture Perspective. Front Plant Sci [Internet]. 2019 Jul 24;10. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2019.00923/full.

- Wang S, Kleiner Y, Clark SM, Raghavan V, Tartakovsky B. Review of current hydroponic food production practices and the potential role of bioelectrochemical systems. Rev Environ Sci Bio/Technology [Internet]. 2024 Sep 28;23(3):897–921. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11157-024-09699-y. [CrossRef]

- Pelayo Lind O, Hultberg M, Bergstrand K-J, Larsson-Jönsson H, Caspersen S, Asp H. Biogas Digestate in Vegetable Hydroponic Production: pH Dynamics and pH Management by Controlled Nitrification. Waste and Biomass Valorization [Internet]. 2021 Jan 13;12(1):123–33. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s12649-020-00965-y. [CrossRef]

- Zhang M, Wang W, Zhong L, Ji F, He D. Bicarbonate used as a buffer for controling nutrient solution pH value during the growth of hydroponic lettuce. Int J Agric Biol Eng [Internet]. 2024;17(3):59–67. Available from: http://www.ijabe.org/index.php/ijabe/article/view/8692.

- Ten facts about water desalination [Internet]. The Spanish Association of Desalination and Reuse. 2024. Available from: https://smartwatermagazine.com/news/smart-water-magazine/ten-facts-about-water-desalination?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Dubai Electricity & Water Authority (DEWA). Slab Tariff [Internet]. 2025. Available from: https://www.dewa.gov.ae/en/consumer/billing/slab-tariff.

- Conti V, Mareri L, Faleri C, Nepi M, Romi M, Cai G, et al. Drought Stress Affects the Response of Italian Local Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum L.) Varieties in a Genotype-Dependent Manner. Plants. 2019;8(9):336. [CrossRef]

- Tesfay T, Berhane A, Gebremariam M. Optimizing Irrigation Water and Nitrogen Fertilizer Levels for Tomato Production. Open Agric J. 2019;13(1):198–206.

- Casals J, Martí M, Rull A, Pons C. Sustainable Transfer of Tomato Landraces to Modern Cropping Systems: The Effects of Environmental Conditions and Management Practices on Long-Shelf-Life Tomatoes. Agronomy. 2021;11(3):533. [CrossRef]

- Ntanasi T, Karavidas I, Zioviris G, Ziogas I, Karaolani M, Fortis D, et al. Assessment of Growth, Yield, and Nutrient Uptake of Mediterranean Tomato Landraces in Response to Salinity Stress. Plants. 2023;12(20):3551. [CrossRef]

- Kuncoro CBD, Asyikin MBZ, Amaris A. Development of an Automation System for Nutrient Film Technique Hydroponic Environment. 2021;

- Ficiciyan A, Loos J, Tscharntke T. Similar Yield Benefits of Hybrid, Conventional, and Organic Tomato and Sweet Pepper Varieties Under Well-Watered and Drought-Stressed Conditions. Front Sustain Food Syst. 2021;5.

- Ercolano MR, Donato AD, Sanseverino W, Barbella MM, Natale AD, Frusciante L. Complex Migration History Is Revealed by Genetic Diversity of Tomato Samples Collected in Italy During the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. Hortic Res. 2020;7(1).

- Galmés J, Ochogavía JM, Gago J, Roldán EJ, Cifré J, Conesa MÀ. Leaf Responses to Drought Stress in Mediterranean Accessions of <i>Solanum Lycopersicum</I>: Anatomical Adaptations in Relation to Gas Exchange Parameters. Plant Cell Environ. 2012;36(5):920–35. [CrossRef]

- Liebisch F, Max JFJ, Heine G, Horst WJ. Blossom-end rot and fruit cracking of tomato grown in net-covered greenhouses in Central Thailand can partly be corrected by calcium and boron sprays. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci [Internet]. 2009 Feb 11;172(1):140–50. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jpln.200800180. [CrossRef]

- Vinh TD, Yoshida Y, Ooyama M, Goto T, Yasuba K, Tanaka Y. Comparative Analysis on Blossom-end Rot Incidence in Two Tomato Cultivars in Relation to Calcium Nutrition and Fruit Growth. Hortic J [Internet]. 2018;87(1):97–105. Available from: https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/hortj/87/1/87_OKD-114/_article. [CrossRef]

- Adams P, Ho LC. UPTAKE AND DISTRIBUTION OFNUTRIENTS IN RELATION TO TOMATO FRUIT QUALITY. Acta Hortic [Internet]. 1995 Nov;(412):374–87. Available from: https://www.actahort.org/books/412/412_45.htm. [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Teruel MÁ, Molina-Aiz FD, López-Martínez A, Marín-Membrive P, Peña-Fernández A, Valera-Martínez DL. The Influence of Different Cooling Systems on the Microclimate, Photosynthetic Activity and Yield of a Tomato Crops (Lycopersicum esculentum Mill.) in Mediterranean Greenhouses. Janick J, editor. Agronomy [Internet]. 2022 Feb 19;12(2):524. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4395/12/2/524. [CrossRef]

- Dorais M, Demers D, Papadopoulos AP, Van Ieperen W. Greenhouse Tomato Fruit Cuticle Cracking. In: Horticultural Reviews [Internet]. Wiley; 2003. p. 163–84. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9780470650837.ch5. [CrossRef]

- Singh H, Dunn BL, Payton ME, Brandenberger L. Selection of Fertilizer and Cultivar of Sweet Pepper and Eggplant for Hydroponic Production. Agronomy. 2019;9(8):433. [CrossRef]

- Madar ÁK, Rubóczki T, Hájos MT. Lettuce Production in Aquaponic and Hydroponic Systems. Acta Univ Sapientiae Agric Environ. 2019;11(1):51–9.

- Boziné-Pullai K, Csambalik L, Drexler D, Reiter D, Tóth F, Bogdányi FT, et al. Tomato Landraces Are Competitive With Commercial Varieties in Terms of Tolerance to Plant Pathogens—A Case Study of Hungarian Gene Bank Accessions on Organic Farms. Diversity. 2021;13(5):195. [CrossRef]

- Rajeev AC, Raju R, Pan A. Temporal Transcriptome and WGCNA Analysis Unveils Divergent Drought Response Strategies in Wild and Cultivated Solanum Varieties. Front Plant Sci. 2025;16. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).