1. Introduction

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) has emerged as a predominant therapeutic modality over the past few decades, establishing itself as the cornerstone intervention for managing sizable renal calculi [

1]. Its ascendancy to this position is primarily attributed to its high efficacy in extracting large and complex renal calculi [

2].

Despite the relatively elevated level of procedural safety, it is not devoid of complications, with hemorrhage being the most commonly encountered. Depending on the circumstances, hemorrhage may manifest intraoperatively or postoperatively (early or delayed) [

2]. The most prevalent causes of postoperative bleeding are arteriovenous fistula – AVF (a communication established between an injured high-flow artery and an injured low-flow vein) and pseudoaneurysm – PA (arterial blood leakage within the parenchyma resulting in a localized hematoma) [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Gross hematuria is almost invariably the most important clinical sign. Significant hemorrhage may manifest during the early postoperative phase (within 2–14 days following PCNL), while AVF formation typically presents as a delayed complication approximately 3-6 weeks after PCNL [

8].

The preferred technique for addressing such vascular complications is selective trans-arterial angioembolization, widely regarded as the gold standard [

4]. Nonetheless, in numerous instances, conservative management alone proves adequate for cessation of bleeding (embolization for severe post-PCNL hemorrhage is required in less than 2% of patients) [

2,

4]. Although angioembolization is the most efficient method to cease the bleeding, contraindications such as contrast hypersensitivity and renal insufficiency should not be ignored, and in these circumstances, it becomes crucial to explore novel methods for controlling and stopping hemorrhage, such as nephrostomy drainage and tamponade [

9].

A case-control study conducted from April 2015 to April 2018 determined that a history of diabetes and renal anomalies may serve as predictive factors for delayed post-PCNL hemorrhage [

2]. Tubeless PCNL (replacement of the standard postoperatively placed nephrostomy tube with an internal drainage that consists of a double-J stent or a ureteral catheter) significantly reduced the occurrence of severe postoperative hemorrhage [

10,

11]. A prospective observational study inferred that arterial hypertension, puncture site, and operative time have a noteworthy impact on estimated hemoglobin deficiency during PCNL [

12].

This case report aims to present the rare case of a patient who experienced delayed postoperative hemorrhage eight years following PCNL and angioembolization.

2. Case Report

A 42-year-old female was admitted to Prof. Dr. Th. Burghele Clinical Hospital, one of the high-volume urology centers in Bucharest, Romania, and also a certified Excellence Center for Uro-Lithiasis affiliated with the European Association of Urology, for macroscopic hematuria, which had its onset 3 hours before admission, and right flank pain, which altered her general condition. Generalized fatigue, palpitations, and dizziness completed the presentation symptoms that progressively developed in the last 48 hours.

In the patient’s medical history, there is a significant record of multiple surgical interventions for right renal lithiasis. Twelve years ago, an imaging examination revealed a calculus in the right ureteropelvic junction, for which Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy (ESWL) was performed. A second round of ESWL was carried out nine years ago. One year later, the patient was diagnosed with right renal lithiasis (approximately 20mm calculus located in the renal pelvis), leading to Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy (PCNL). Postoperatively, at 48 hours, the patient experienced intermittent macroscopic hematuria and suspicion of arteriovenous fistula at the level of the right kidney, prompting selective angioembolization with two coils. Between 2016 and 2024, the patient experienced no urological disorders, and beyond this period, she did not have any other known pathologies or surgical interventions in her medical history.

The physical examination revealed abdominal pain, more pronounced in the right flank, tenderness, and pallor. Upon admission, the body temperature was assessed to be within the normal range. The cardiovascular and respiratory assessment indicated the presence of tachycardia (110 beats/min.) without tachypnea (respiratory rate—15 breaths/min.). The measured blood pressure was 102/75 mmHg, with oxygen saturation recorded at 98%.

Complete blood tests were performed, and the results indicated mild leukocytosis (WBC: 12.5 x 10^9/L) and neutrophilia (NE#: 9.4 x 10^9/L) with normal hemoglobin levels (Hgb: 12.2 g/dL).

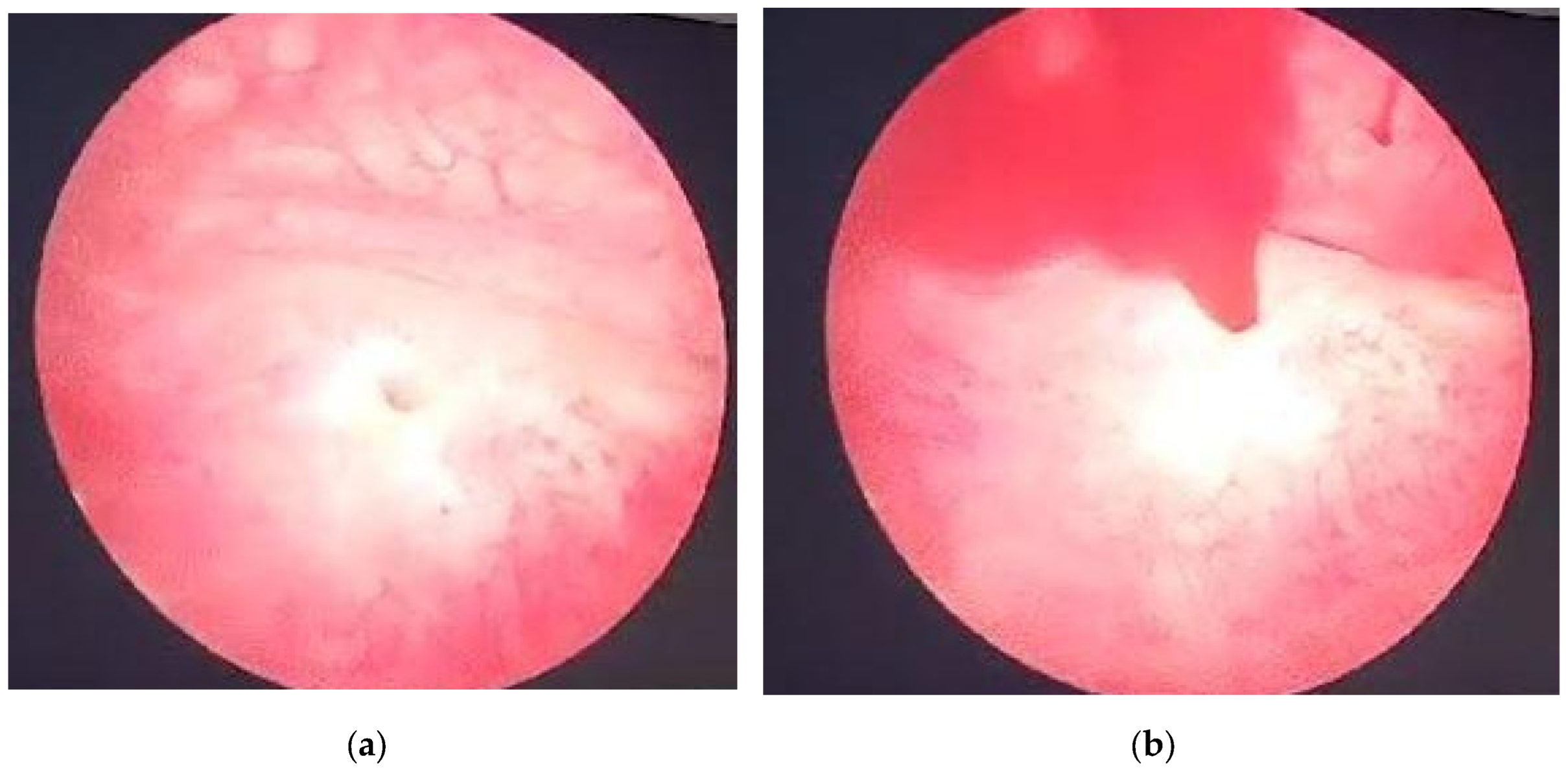

Right after the admission, a cystoscopic evaluation was made under spinal anesthesia, revealing no discernible source of bleeding within the bladder. Spontaneous sanguineous emission was observed at the right ureteral orifice site (

Figure 1). The antibiotic prophylactic therapy was started with Ceftamil 1 g according to local sensitivity data [

13].

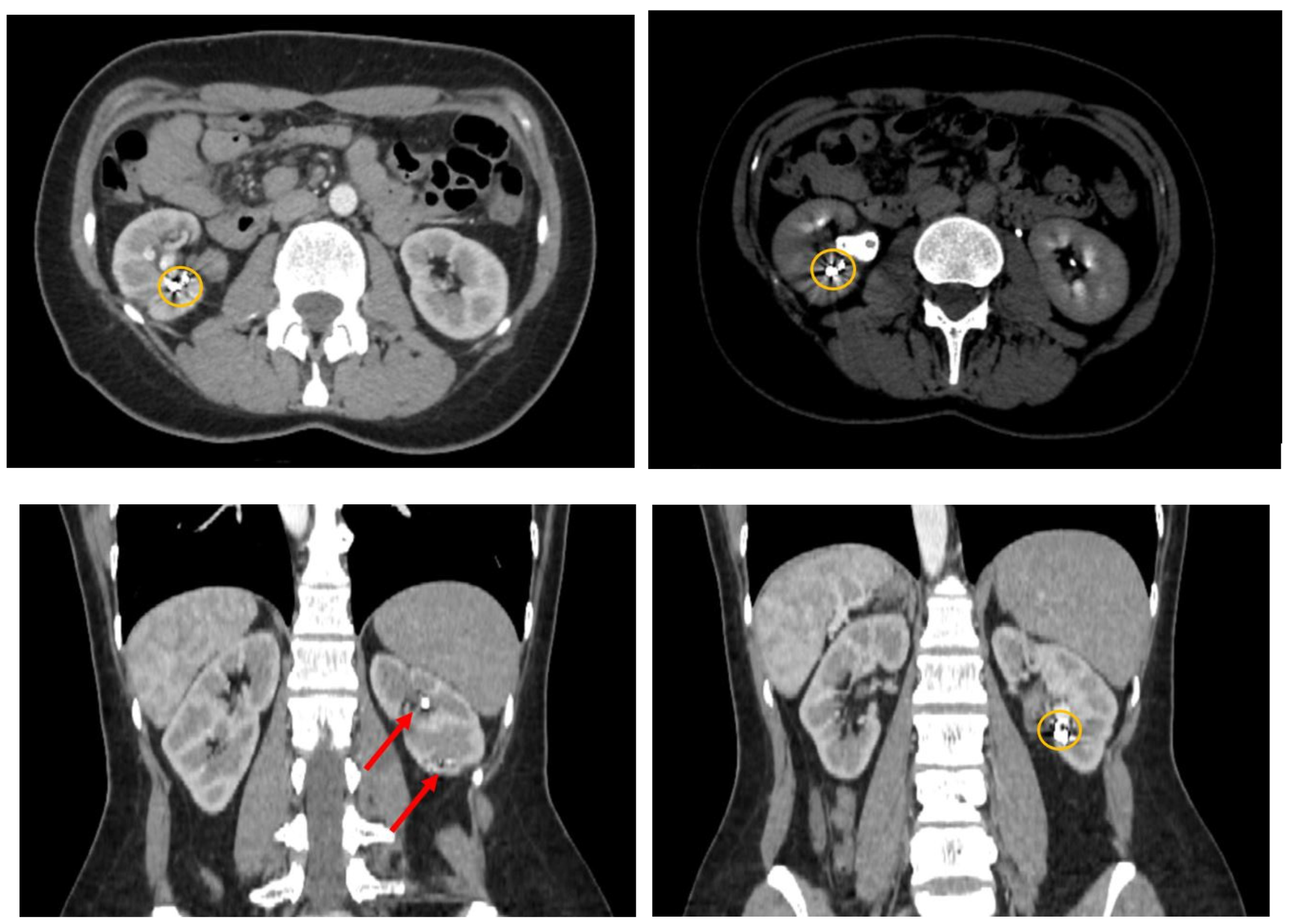

Following the cystoscopy, a contrast-enhanced computed tomography was performed to evaluate the abdomen and pelvic regions (

Figure 2). The CT report indicated multiple hematic accumulations at various stages of degradation, predominantly recent (with average native densities of approximately 60 Hounsfield Units), within the right renal collecting system, without evidence of dilation. At the lower pole level, multiple pseudoaneurysm-like images were observed. These lesions appeared within the renal sinus, approximately 10mm in maximum diameter, and in intimate contact with the lower and middle calyceal stems. A series of metallic structures was identified, described in the report as clips (most probably the coils used during the last angioembolization). A small number of unobstructive stone fragments were also identified, with distribution in all the calyces and a maximum diameter of 5 mm.

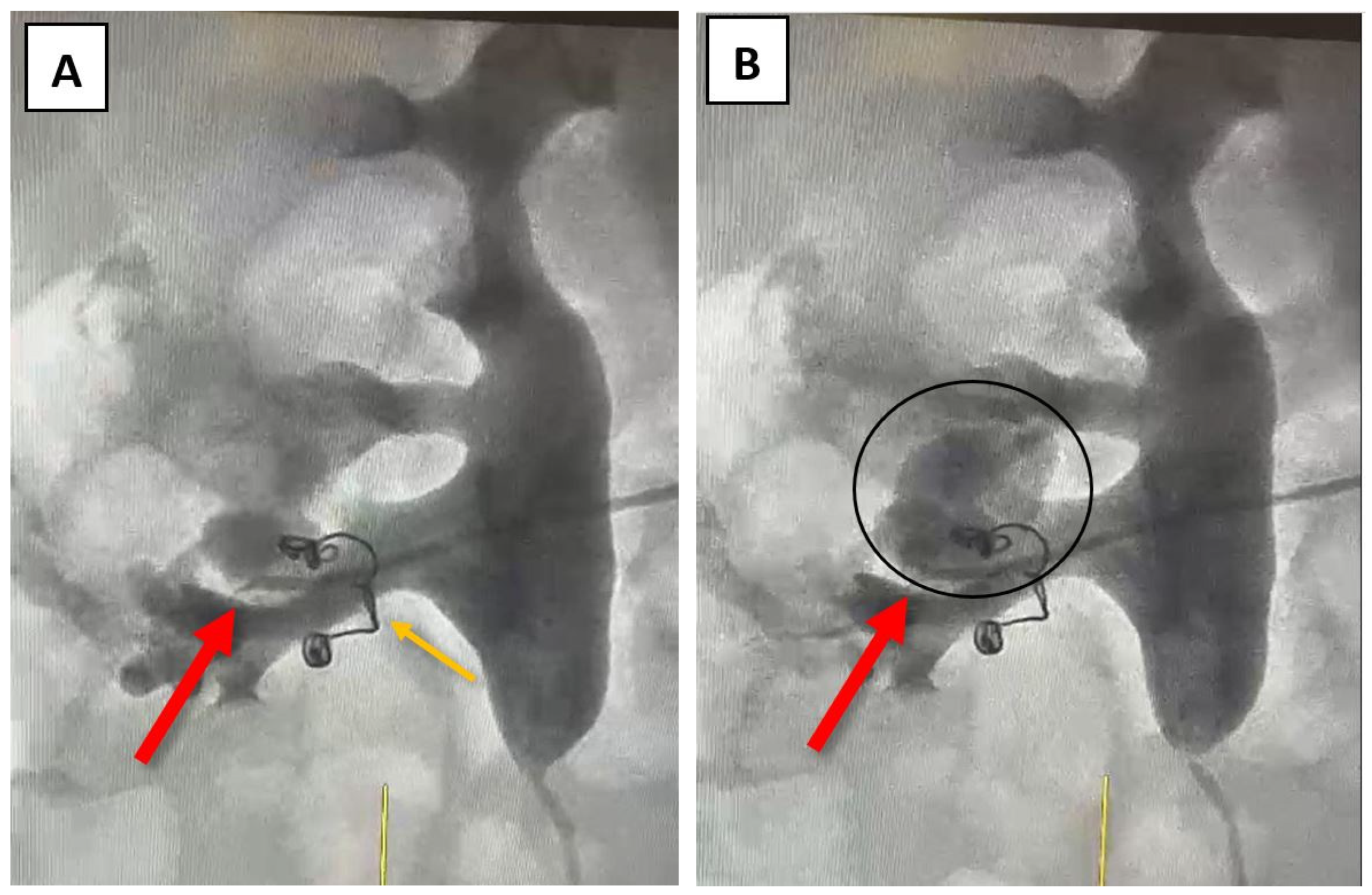

At this point, a possible fistula between an arterial vessel and the right renal pelvis was suspected, and further investigations, such as angiography, were recommended to facilitate further correlation of data. Angiography was performed through the right brachial vein using a Cobra 4F catheter. The source of bleeding was identified at the site of a small inferior renal arterial vessel after the selective administration of the contrast agent (

Figure 3A,B). The coils used during the last angioembolization (eight years ago) can be observed in

Figure 3.

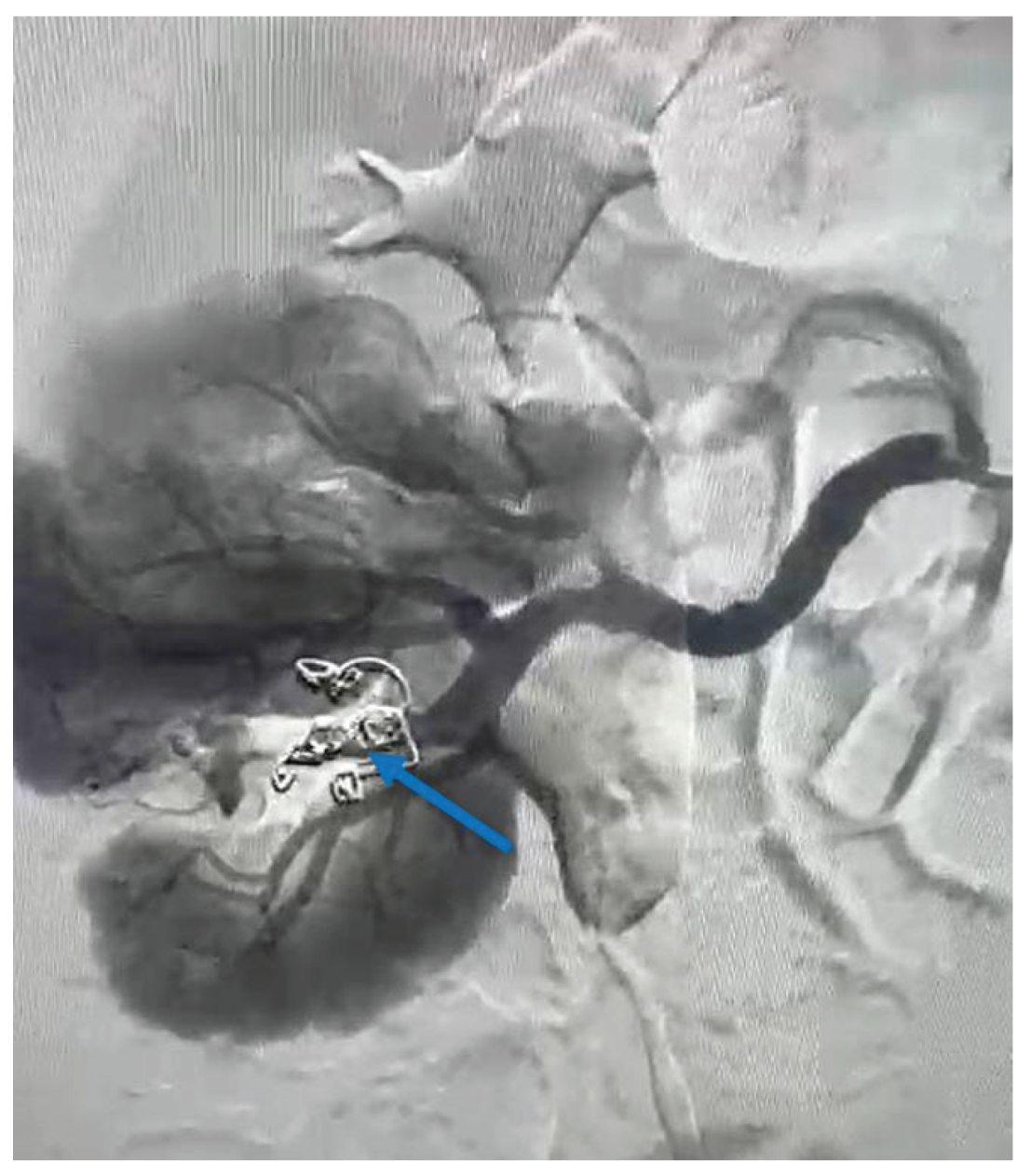

To control and cease the hemorrhage, a guidewire was introduced at the vessel’s site, and a selective embolization was carried out using two VortX Diamond© coils of 6/7.7mm each (

Figure 4). The procedure time of the angioembolization was 7 minutes and 50 seconds.

Twenty-four hours after the procedure, the patient presented an improved general condition and mild lumbar pain (2/10 on the visual analog scale) without hematuria or other physical signs of bleeding. Upon discharge, the patient presents with good general condition, afebrile, stable hemodynamics, normal skin and mucous membrane coloration, effortless micturition, and clear urine.

3. Discussion

Although numerous complications can arise following PCNL, renal hemorrhage remains the most common, with an incidence ranging from 11.2% to 17.5% [

8]. As mentioned before, the most common causes of major postsurgical bleeding are represented by vascular complications such as pseudoaneurysms, arteriovenous fistula, and segmental arterial injury [

3,

4]. However, angioembolization remains the gold standard in managing these particular situations, and the risk of complications such as nephrectomy is present [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Other situations in which these complications may occur are after renal biopsy, partial nephrectomy, or urological trauma [

4]. One additional adverse consequence associated with super-selective renal angioembolization is functional impairment; however, this effect was more pronounced among patients with solitary kidneys [

18]. The associated signs and symptoms, such as hematuria and lumbar pain, should be immediately recognized, and further investigations should be performed.

In the present case, the investigations were initiated with a complete blood count to assess the hemoglobin level and evaluate the severity of the anemia. We continued the investigations with cystoscopy to exclude any specific bleeding source within the bladder. Considering that the source of bleeding is located at the level of the upper urinary tract and considering the patient’s urologic history, we conducted a contrast-enhanced CT scan, which guided us regarding the location of the lesion. In terms of treatment, we decided that angioembolization is the best choice.

Since the second half of the last century, endovascular access has been the most popular option for managing haemorrhagic events in the urological field [

19,

20]. Angioembolization presents itself with the advantages of being minimally invasive, safe, suitable even for critical patients, and effective, especially as an emergency procedure, not only in cases of arteriovenous fistula following PCNL, but also in situations like preoperative infarction of renal tumors, treatment of angiomyolipomas, vascular malformations, medical renal disease, and complications following renal transplantation [

21,

22].

The renal haemorrhage can be controlled using various embolic agents, although some studies underline the higher effectiveness of coils in several clinical situations [

19,

20,

23,

24,

25,

26]. The main reasons discussed include the facile manipulation, lower rates and smaller areas of renal ischemia—therefore a lower degree of renal function impairment —and better tracking accuracy of the embolic agent after its detachment into the target vessel [

19]. As described and pictured earlier in

Figure 4, coils were also used in the present case as an embolic agent during the angioembolization.

The vascular access is usually achieved through the femoral artery, but the brachial or the axillary artery represents valid alternatives in case of occlusion of the femoral arteries [

23]. The caliber of the sheath should be 5 French or larger, depending on the complexity of the procedure. Various types of catheters can be used – Cobra-configured, RC-2-shaped, SOS-shaped, Levi (Lev-1), and Simmons-shaped catheters. The main argument for choosing one type over another consists of the anatomical particularities of the renal arteries and the associated pathologies involving the vessels [

23]. Microcatheters are extremely useful in the context of supraselective angioembolization.

In the setting of AVF, the success of the angioembolization is obtained with superselective catheters with coaxial systems and microcoils as the embolic agent. It is highly recommended not to use particles, given the high risk of pulmonary embolism due to passing through the communication between the artery and the vein. The technical goal is achieved when the fistula is completely obliterated at the cost of minimal renal function impairment [

23].

Lee et al. conducted a retrospective study on 62 patients who underwent renal artery embolization between January 2009 and December 2019 [

27]. In this study, it was pointed out that a large number of patients who undergo renal artery angioembolization may have underlying kidney disease or arterial hypertension. It was demonstrated that although no patient developed chronic kidney disease in the short term after the procedure, a noticeable decline in the estimated glomerular filtration rate was observed in the long term. The study concluded that, although supraselective angioembolization is most of the time a safe procedure, acute kidney injury still counts as a serious possible complication [

27].

Irani et al. conducted a case-control study in which several risk and predictive factors for delayed bleeding after percutaneous nephrolithotomy requiring angioembolization have been proposed and evaluated – history of diabetes, history of arterial hypertension, history of SWL, history of PCNL, history of open surgery, coagulation disorders and the presence of a renal anomaly – only history of diabetes and the presence of a renal anomaly were found to be statistically significant [

2]. According to El-Nahas et al., upper caliceal puncture, solitary kidney, staghorn stone, multiple punctures, and an inexperienced surgeon have all been identified as significant risk factors for severe bleeding [

28]. Loo et al. concluded that arterial hypertension, puncture site, and operative duration significantly impact estimated Hb deficiency during PCNL [

12]. Other factors that may predict a hemorrhagic event include stone burden, the degree of hydronephrosis, urinary tract infection, American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) grade, and operation time [

29,

30,

31]. Apart from the history of SWL, none of the factors mentioned above were present in our patient’s case.

Considering the patient’s medical history, which includes a previous selective angioembolization (SAE), our focus shifted toward identifying potential risk factors that may have contributed to or predicted the failure of the procedure. In a study that evaluated the predictive factors of SAE failure for moderate- to high-grade renal trauma, Baboudijian et al. found gross hematuria, hemodynamic instability, and urinary extravasation to be statistically significant [

32]. After the first SAE, our patient did not exhibit any of these factors. In a case report published by Seno et al., another set of risk factors was identified as significant in predicting initial super-selective renal arterial embolization failure; this set includes multiple percutaneous access sites, more than two bleeding sites on a renal angiogram, and the use of a gelatin sponge alone as embolic material [

3]. In our case, the patient presented with only one percutaneous access site during the initial angioembolization and a single bleeding site on the renal angiogram. During the angioembolization procedure, two coils were used (as depicted in

Figure 3 – indicated by the orange arrow). Thus, none of the aforementioned situations were present in our patient’s case.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of delayed bleeding occurring eight years after PCNL and angioembolization. This case is even rarer, considering the patient exhibited no urological signs or symptoms during the intervening years. The absence of any known risk or predictive factor may serve as a key element for further investigations into other scenarios that could potentially lead to vascular and hemorrhagic complications similar to those described in this case.

4. Conclusions

Although in most situations, post-PCNL bleeding can be controlled through conservative methods, angioembolization remains the first therapy of choice in complicated cases. Through the case presented in this article, we aim to draw attention to the fact that there is no temporal limit within which delayed post-angioembolization vascular complications and renal hemorrhage may occur. Therefore, systematic follow-up remains the best option for diagnosing and monitoring any potential complications that may arise after PCNL and after angioembolization, regardless of the presence or absence of known risk factors documented in the current literature.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A.D. and R.-C.P; investigation, R.A.D., R.I.P., A.L.O. and A.P.; resources, R.I.P, A.L.O., A.P. and V.J.; data curation, A.P. and V.J.; writing—original draft preparation, R.A.D., R.I.P., A.L.O. and A.P.; writing—review and editing, V.J. and R.-C.P.; supervision, R.-C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because our institution does not require Ethics Committee approval for individual case reports.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this paper (including publication of images), which fully authorized the authors to use her medical data for research purposes.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AVF |

Arteriovenous fistula |

| CT |

Computed tomography |

| ESWL |

Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy |

| PA |

Pseudoaneurysm |

| PCNL |

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy |

| SAE |

Selective angioembolization |

References

- Devos, B.; Vandeursen, H.; d’Archambeau, O.; Vergauwe, E. Renal pseudoaneurysm with associated arteriovenous fistula as a cause of delayed bleeding after percutaneous nephrolithotomy: a case report and current literature review. Case Rep Urol. 2023, 2023, 5103854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irani, D.; Haghpanah, A.; Rasekhi, A.; Kamran, H.; Rahmanian, M.; Hosseini, M.M.; Dejman, B.; Kiani, S. Predictive factors of delayed bleeding after percutaneous nephrolithotomy requiring angioembolization. BJUI Compass. 2023 5, 76–83. [CrossRef]

- Seno, D.H.; Siregar, M.A.R.; Afriansyah, A.; Arisutawan, I.P.K.; Leonardo, K. A rare case report of renal vein embolization after failed selective angioembolization to treat delayed complication of percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2024, 115, 109257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouralizadeh, A.; Rostaminejad, N.; Radpour, N.; Momeni, H.; Narouie, B.; Dadpour, M. Percutaneous re-surgical approach for delayed bleeding caused by pseudoaneurysm following percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Urol Case Rep. 2023, 50, 102551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, J.N.; Hatimota, P. Same-day angiography and embolization in delayed hematuria following percutaneous nephrolithotomy: an effective, safe, and time-saving approach. Res Rep Urol. 2019, 11, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulakis, V.; Ferakis, N.; Becht, E.; Deliveliotis, C.; Duex, M. Treatment of renal-vascular injury by transcatheter embolization: immediate and long-term effects on renal function. J Endourol. 2006, 20, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richstone, L.; Reggio, E.; Ost, M.C.; Seideman, C.; Fossett, L. K.; Okeke, Z.; Rastinehad, A.R.; Lobko, I.; Siegel, D.N.; Smith, A. D. First prize (tie): hemorrhage following percutaneous renal surgery: characterization of angiographic findings. J Endourol. 2008, 22, 1129–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, P.; Gupta, N.K.; Pal, D.K. Coexisting pseudoaneurysm and arteriovenous fistula following percutaneous nephrolithotomy: A brief case report. Ann Med Sci Res 2023, 2, 121–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouralizadeh, A.; Aslani, A.; Ghanaat, I.; Bonakdar Hashemi, M. Percutaneous endoscopic treatment of complicated delayed bleeding postpercutaneous nephrolithotomy: a novel suggestion. J Endourol Case Rep. 2020, 6, 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nouralizadeh, A.; Ziaee, S.A.; Hosseini Sharifi, S.H.; Basiri, A.; Tabibi, A.; Sharifiaghdas, F.; Zaki, H.; Nikkar, M.M.; Lashay, A.; Ahanian, A.; Soltani, M. H. Delayed postpercutaneous nephrolithotomy hemorrhage: prevalence, predictive factors and management. Scand J Urol. 2014, 48, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal MS, Agrawal M. Tubeless percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Indian J Urol. 2010, 26, 16–24. [CrossRef]

- Loo, U.P.; Yong, C.H.; Teh, G.C. Predictive factors for percutaneous nephrolithotomy bleeding risks. Asian J Urol. 2024, 11, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petca, R.C.; Popescu, R.I.; Mares, C.; Petca, A.; Mehedintu, C.; Sandu, I.; Maru, N. Antibiotic resistance profile of common uropathogens implicated in urinary tract infections in Romania. Farmacia 2019, 67, 994–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.W.; Fei, X.; Song, Y. Renal pelvis mucosal artery hemorrhage after percutaneous nephrolithotomy: a rare case report and literature review. BMC Urol 2022, 22, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantasdemir, M.; Adaletli, I.; Cebi, D.; Kantarci, F.; Selcuk, N.D.; Numan, F. Emergency endovascular embolization of traumatic intrarenal arterial pseudoaneurysms with N-butyl cyanoacrylate. Clin Radiol. 2003, 58, 560–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inci, K.; Cil, B.; Yazici, S.; Peynircioglu, B.; Tan, B.; Sahin, A.; et al. Renal artery pseudoaneurysm: complication of minimally invasive kidney surgery. J Endourol. 2010, 24, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollin, D.A.; Preminger, G.M. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy: complications and how to deal with them. Urolithiasis. 2018, 46, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Nahas, A.R.; Shokeir, A.A.; Mohsen, T.; Gad, H.; el-Assmy, A.M.; el-Diasty, T.; el-Kappany, H.A. Functional and morphological effects of postpercutaneous nephrolithotomy superselective renal angiographic embolization. Urology. 2008, 71, 408–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Reis, J.M.C.; Kudo, F.A.; Bastos, M.D.C.; Reale, H.B.; Aguiar, M.F.M.; Dos Santos, J.V.F. Superselective renal artery embolization for treatment of urological hemorrhage after partial nephrectomy in a solitary kidney. J Vasc Bras. 2020, 19, e20200005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withington, J.; Neves, J.B.; Barod, R. Surgical and minimally invasive therapies for the management of the small renal mass. Curr Urol Rep. 2017, 18, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Mao, Q.; Tan, F.; Shen, B. Superselective renal artery embolization in the treatment of renal hemorrhage. Epub 2013 Jun 4. Ir J Med Sci. 2014, 183, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonopoulos, I.M.; Yamaçake, K.G.R.; Tiseo, B.C.; Carnevale, F.C.; Zieck, E.Jr.; Nahas, W.C. Renal pseudoaneurysm after core-needle biopsy of renal allograft successfully managed with superselective embolization. Int Braz J Urol. 2016, 42, 165–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauk, S.; Zuckerman, D.A. Renal artery embolization. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2011, 28, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, T.; Roberts, M.J.; Navaratnam, A.; Chung, E.; Wood, S. Changing etiology and management patterns for spontaneous renal hemorrhage: a systematic review of contemporary series. Int Urol Nephrol. 2017, 49, 1897–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, K.; Gahide, G.; Soulez, G.; Giroux, M. F.; Oliva, V. L.; Perreault, P.; Bouchard, L.; Gilbert, P.; Therasse, E. Percutaneous embolization of iatrogenic arterial kidney injuries: safety, efficacy, and impact on blood pressure and renal function. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011, 22, 1562–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Wang, C.; Yang, M.; Tong, X.; Wang, J.; Guan, H.; Song, L.; Zou, Y. Management of iatrogenic renal arteriovenous fistula and renal arterial pseudoaneurysm by transarterial embolization: a single center analysis and outcomes. Medicine. 2017, 96, e8187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.N.; Yang, S.B.; Goo, D.E.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, W.H.; Hyun, D.; Heo, N.H. Impact of superselective renal artery embolization on renal function and blood pressure. J Belg Soc Radiol. 2020, 104, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Nahas, A.R.; Shokeir, A.A.; El-Assmy, A.M.; Mohsen, T.; Shoma, A.M.; Eraky, I.; El-Kenawy, M.R.; El-Kappany, H.A. Post-percutaneous nephrolithotomy extensive hemorrhage: a study of risk factors. J Urol. 2007, 177, 576–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganpule, A.P.; Shah, D.H.; Desai, M.R. Postpercutaneous nephrolithotomy bleeding: aetiology and management. Curr Opin Urol. 2014, 24, 189–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kukreja, R.; Desai, M.; Patel, S.; Bapat, S.; Desai, M. Factors affecting blood loss during percutaneous nephrolithotomy: prospective study. J Endourol 2004, 18, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Singh, K. J.; Suri, A.; Dubey, D.; Kumar, A.; Kapoor, R.; Mandhani, A.; Jain, S. Vascular complications after percutaneous nephrolithotomy: are there any predictive factors? Urology. 2005, 66, 38–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baboudjian, M.; Gondran-Tellier, B.; Panayotopoulos, P.; Hutin, M.; Olivier, J.; Ruggiero, M.; Dominique, I.; Millet, C.; Bergerat, S.; Freton, L.; Betari, R.; Matillon, X.; Chebbi, A.; Caes, T.; Patard, P.M.; Szabla, N.; Sabourin, L.; Dariane, C.; Lebacle, C.; Rizk, J., … TRAUMAFUF Collaborative Group (2022). Factors predictive of selective angioembolization failure for moderate- to high-grade renal trauma: a French multi-institutional study. Eur Urol Focus. 2022, 8, 253–258.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).