Submitted:

02 November 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

| κατὰ μὲν τὴν οὐσίαν καὶ τὸν λόγον τὸν τὸ τί ἦν εἶναι λέγοντα μεσότης ἐστὶν ἡ ἀρετή, κατὰ δὲ τὸ ἄριστον καὶ τὸ εὖ |

| ἀκρότης. (In terms of its essence and the definition of its nature, virtue is the mean, but in terms of excellence and rightness, [virtue is] |

| the extreme; Aristotle [1]) |

1. Introduction

2. Data

3. Methods

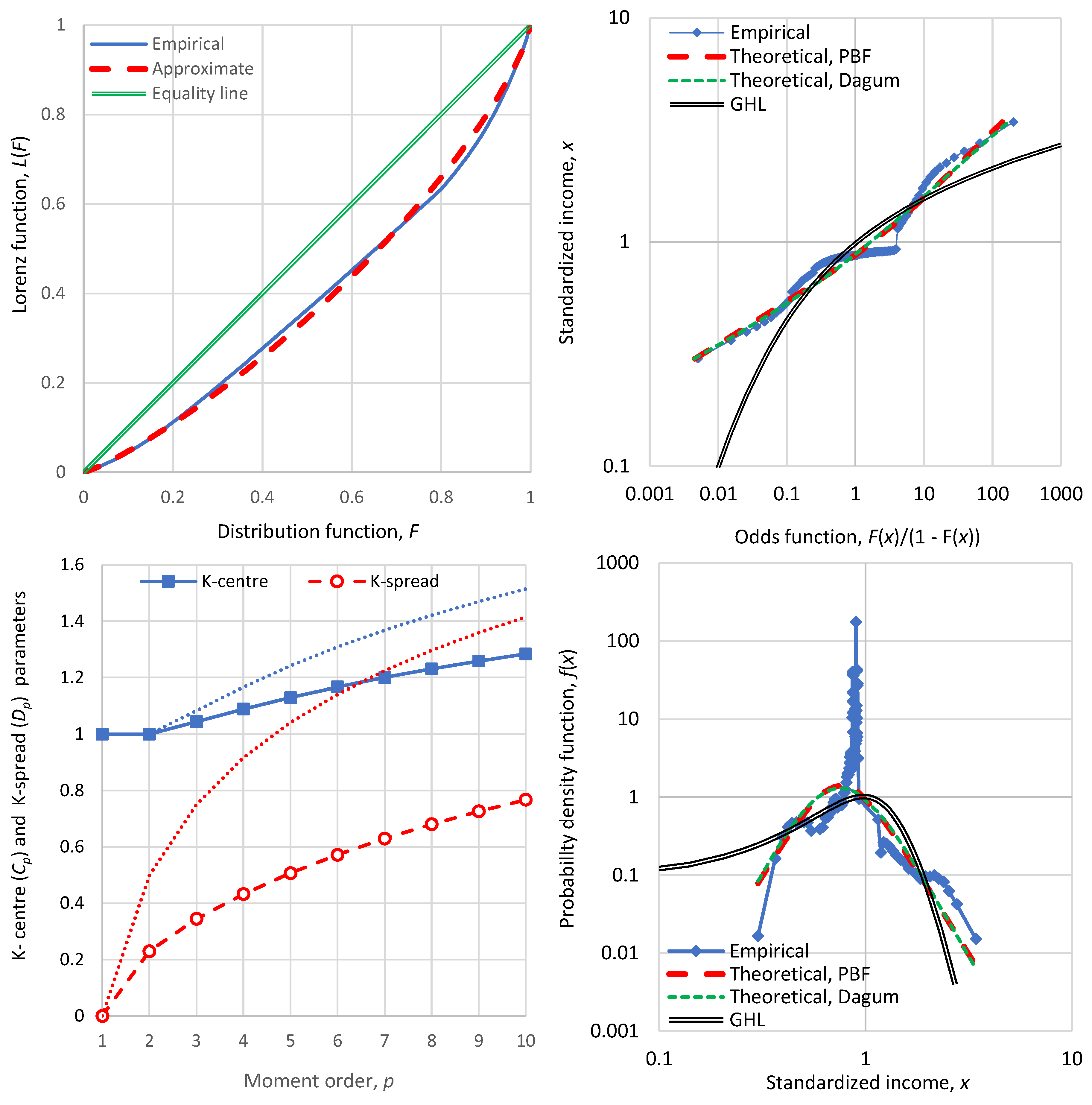

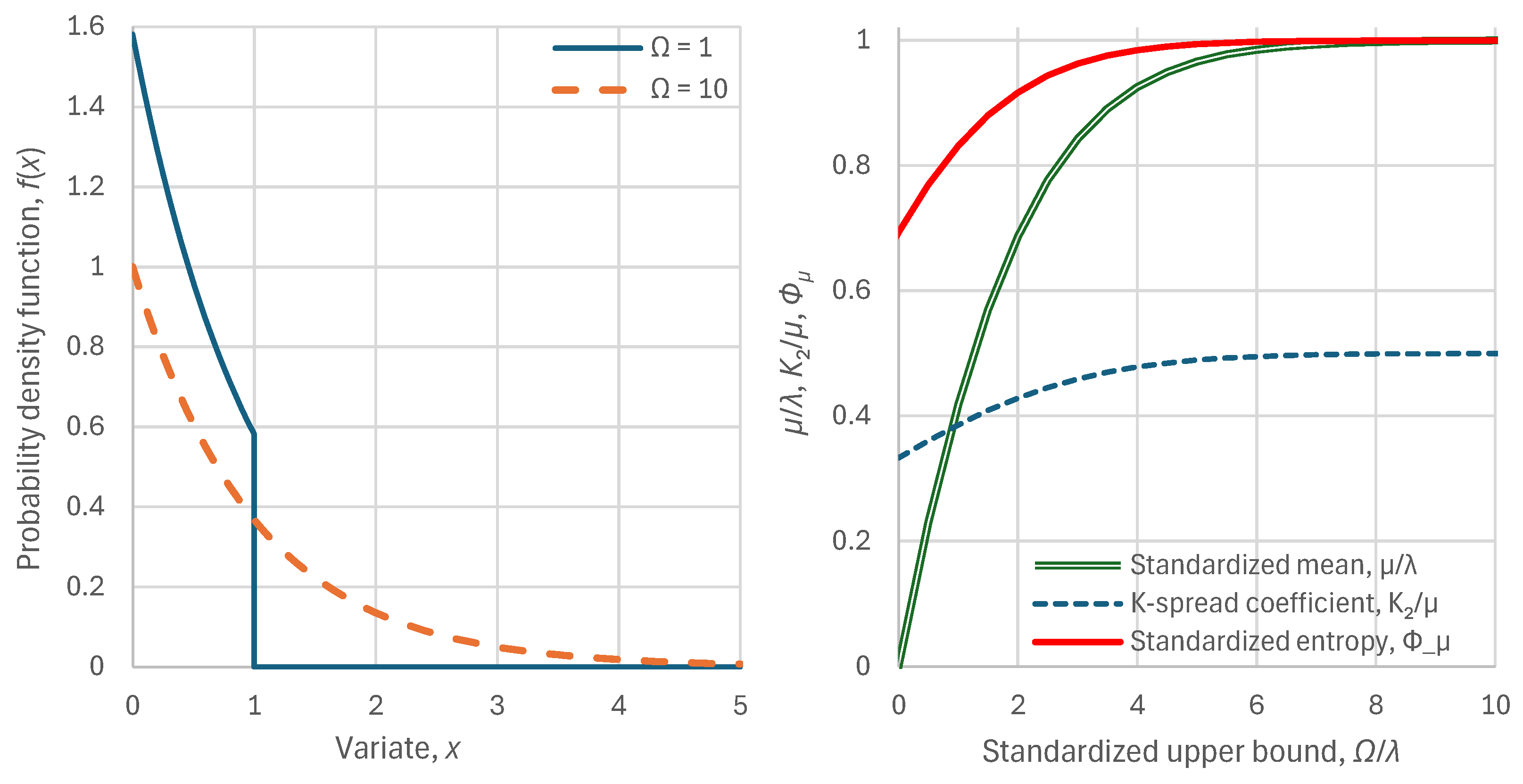

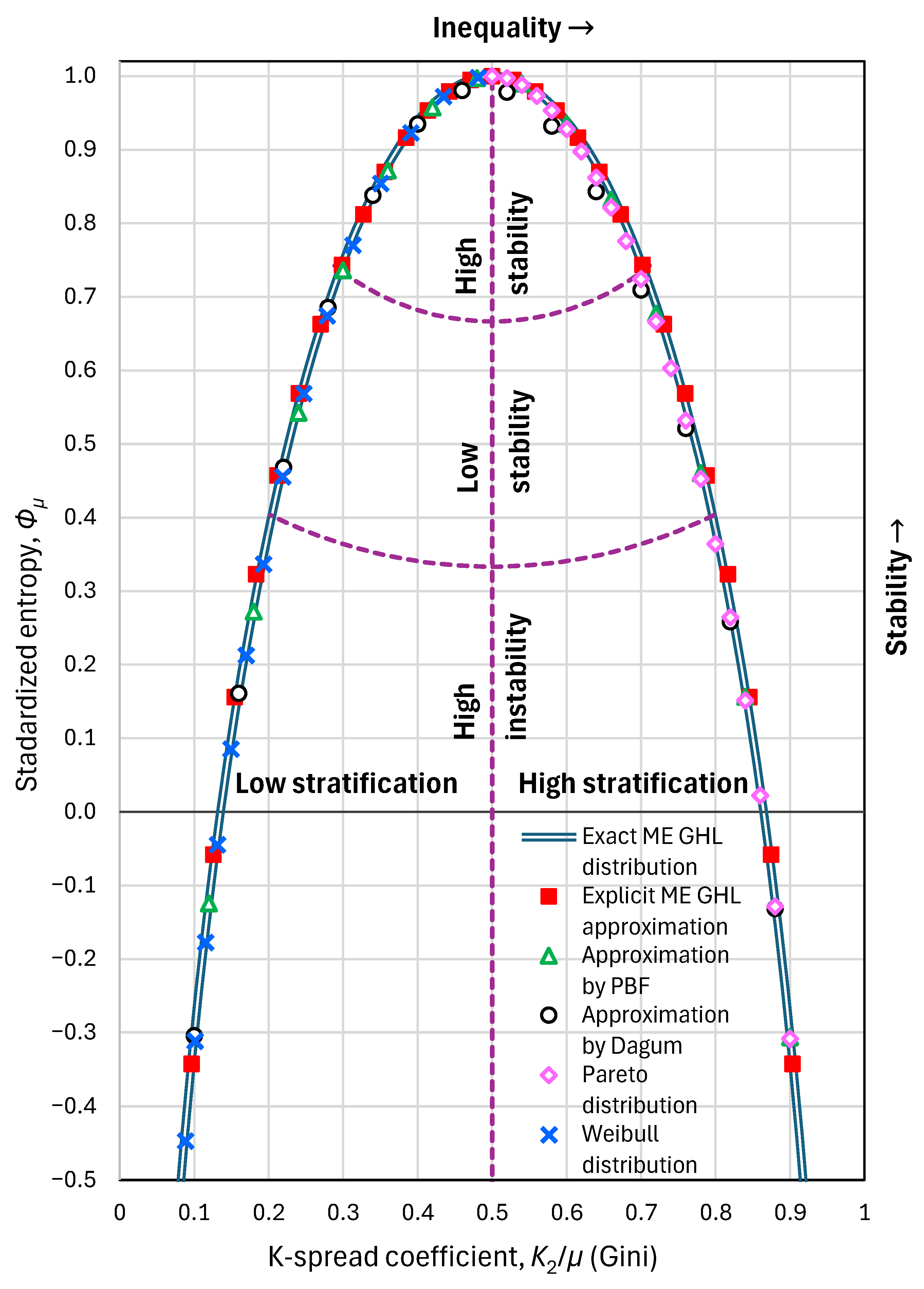

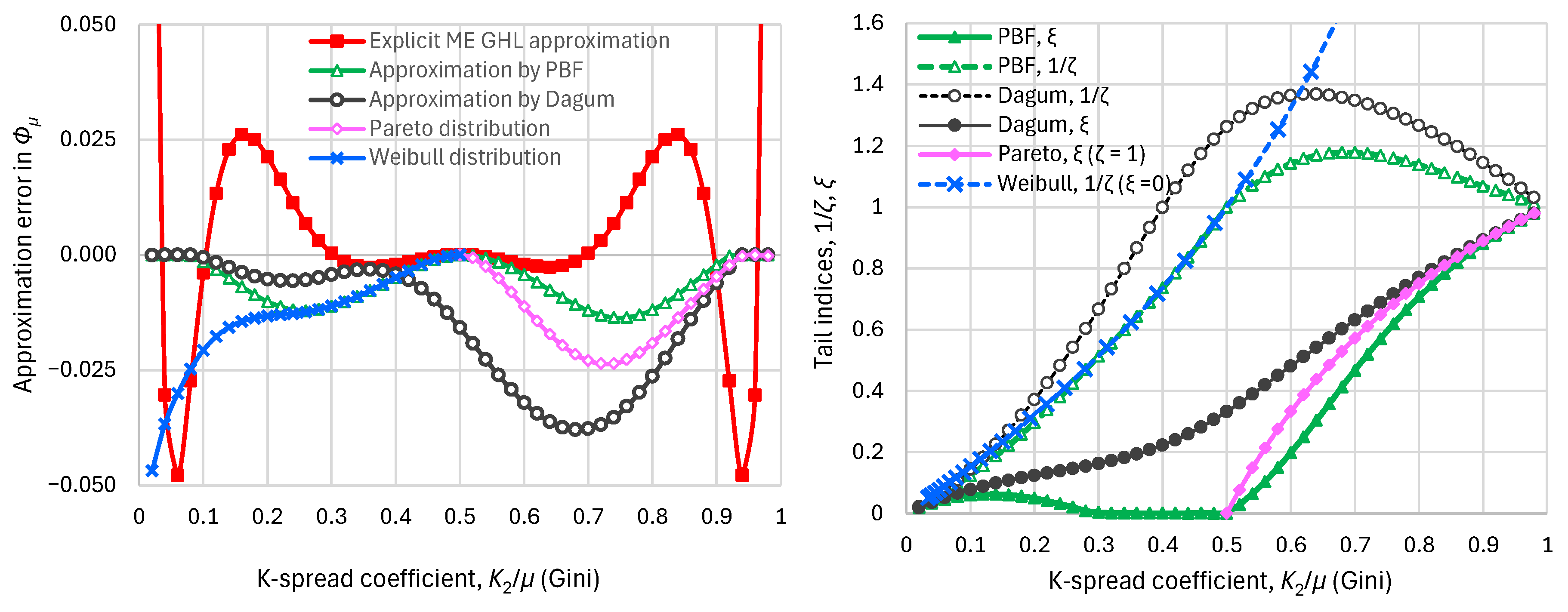

3.1. Basic Stochastic Tools

3.1.1. Distribution Function and Relative Concepts; Expectation and Moments

3.1.2. Entropy and Standardized Entropy

3.1.3. K-Moments

3.1.4. Specific Distribution Functions and Tail Indices

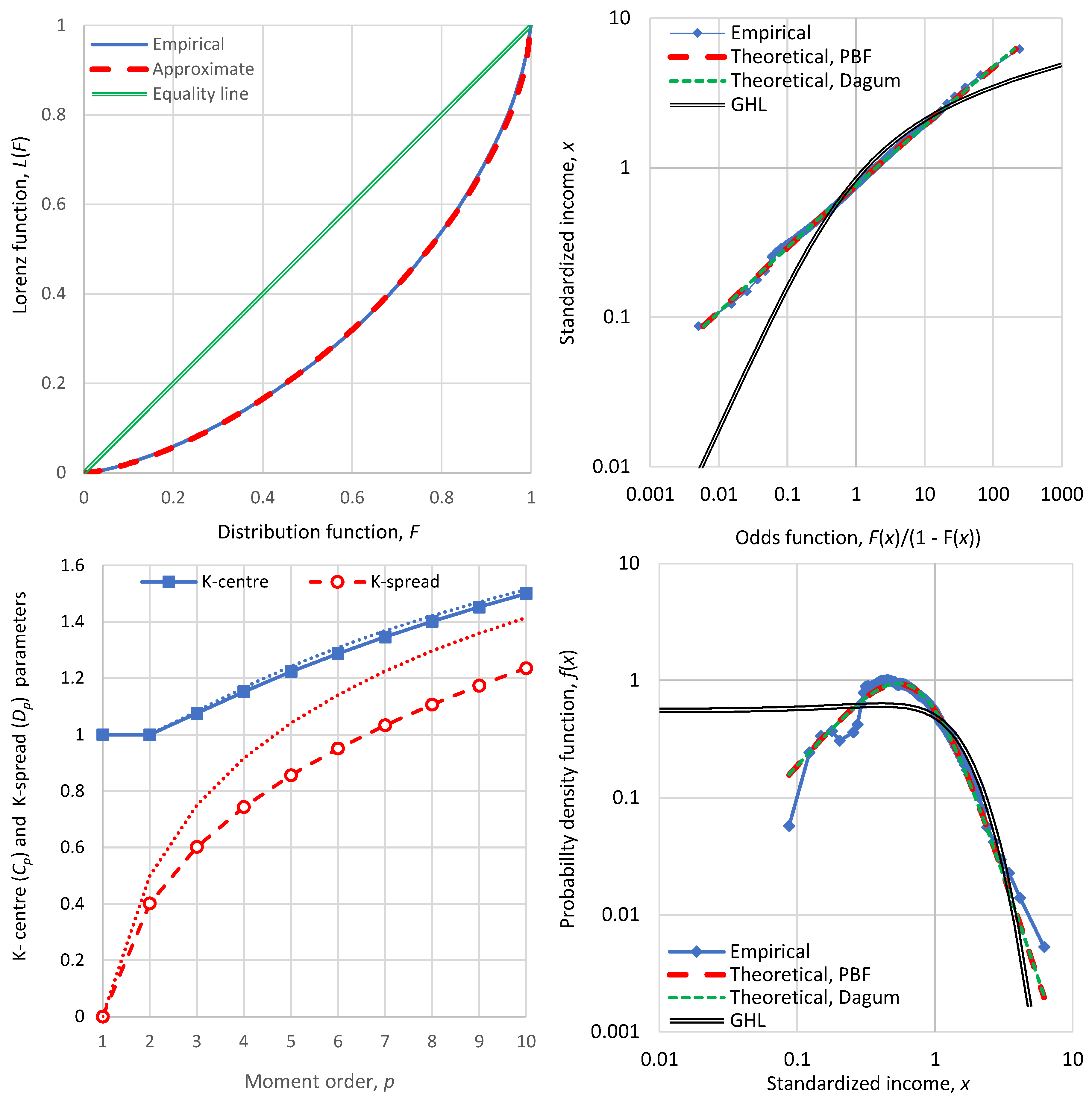

3.2. The Lorenz curve and the Gini Index

3.3. Maximum Entropy Distributions

4. Application

4.1. General Setting

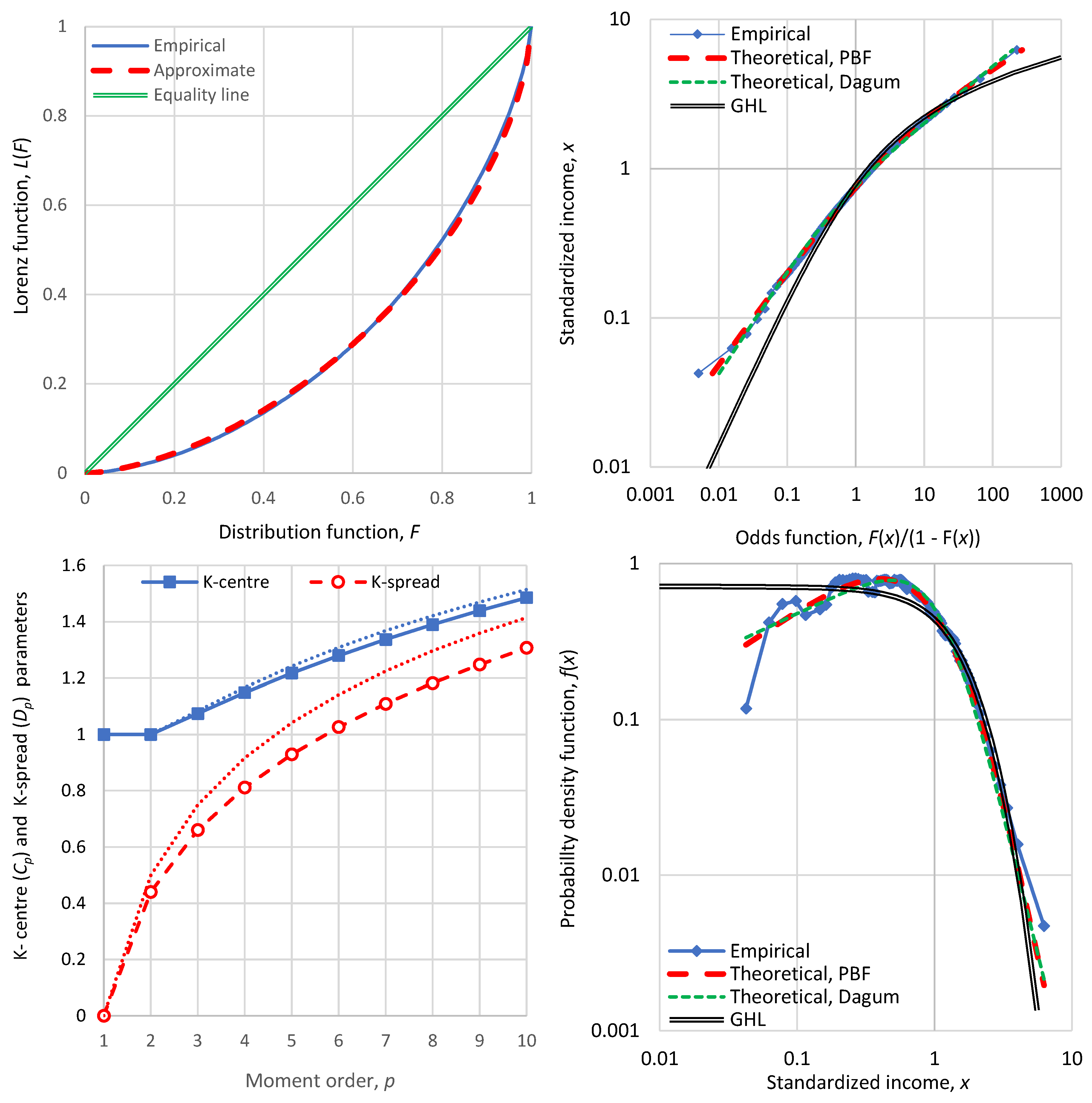

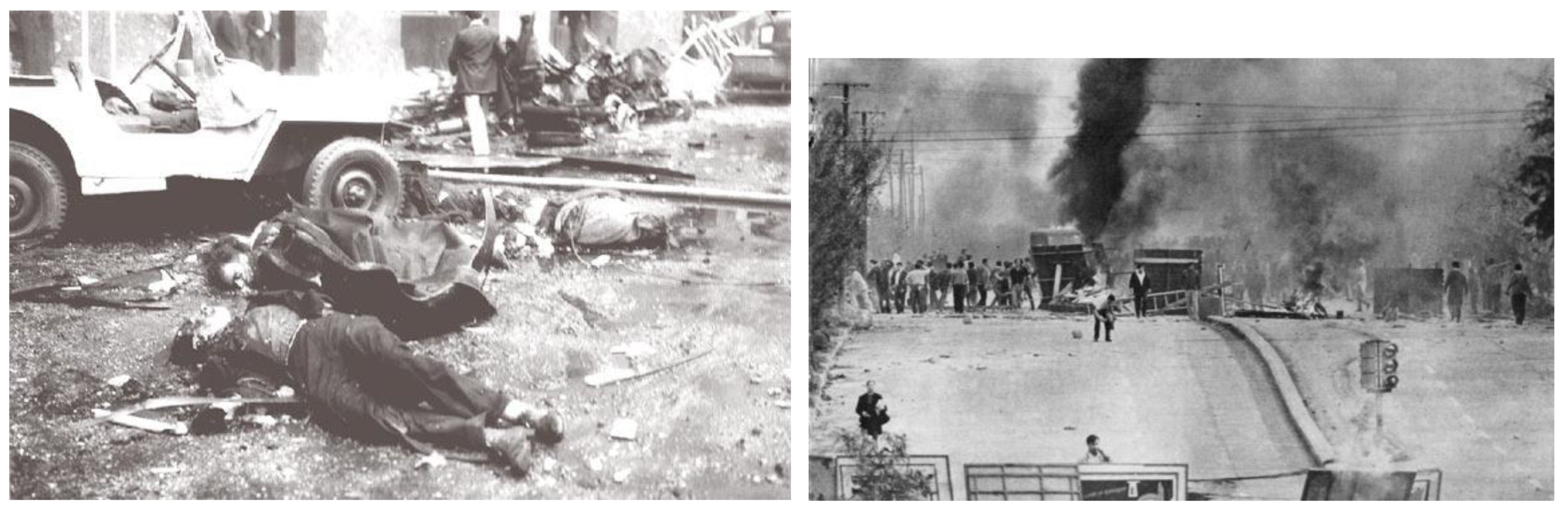

4.2. The Status of the Major Geopolitical Powers in 2022

4.3. A Brief Political History and the Evolution of Economic Indices in Specific Countries

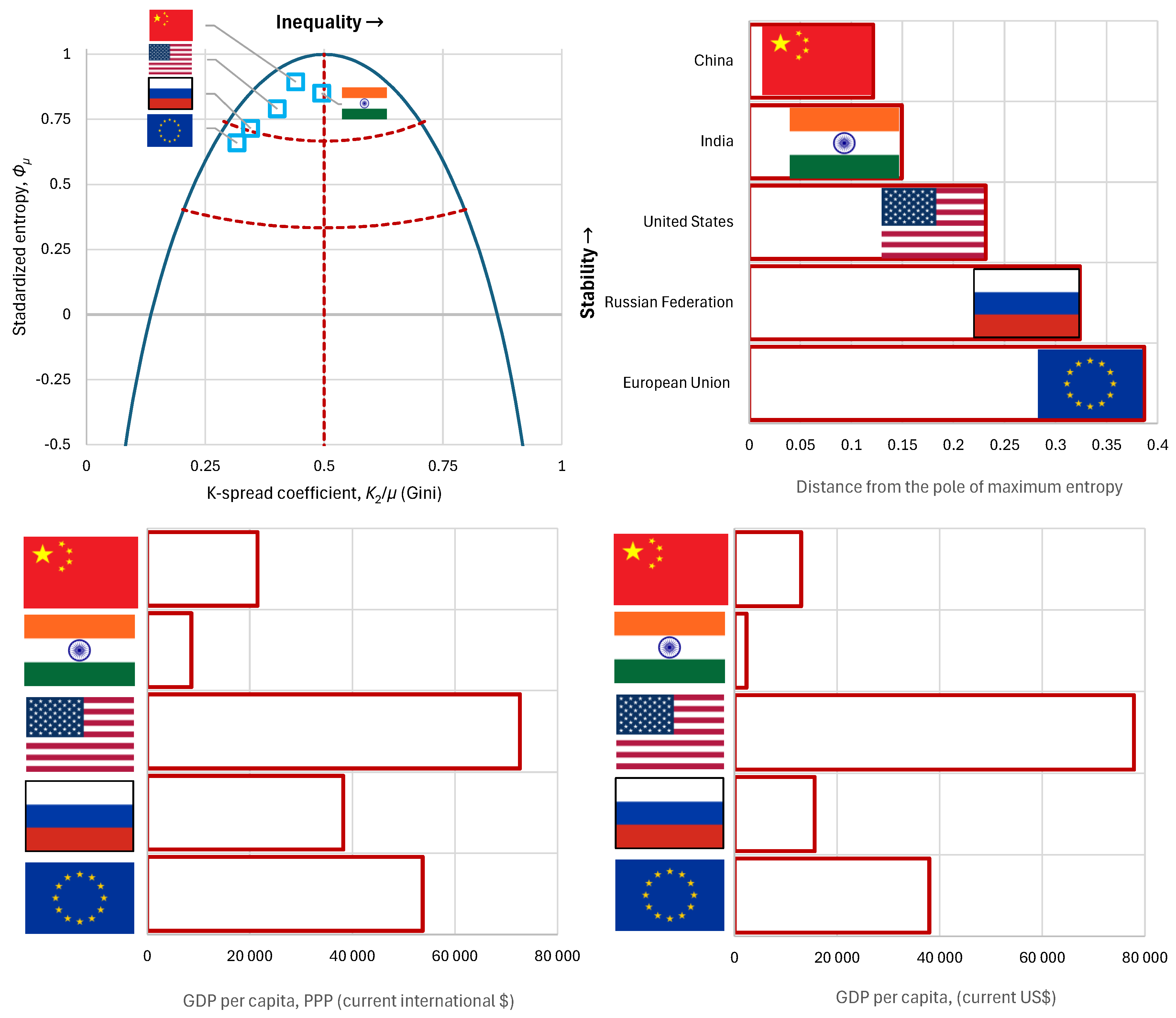

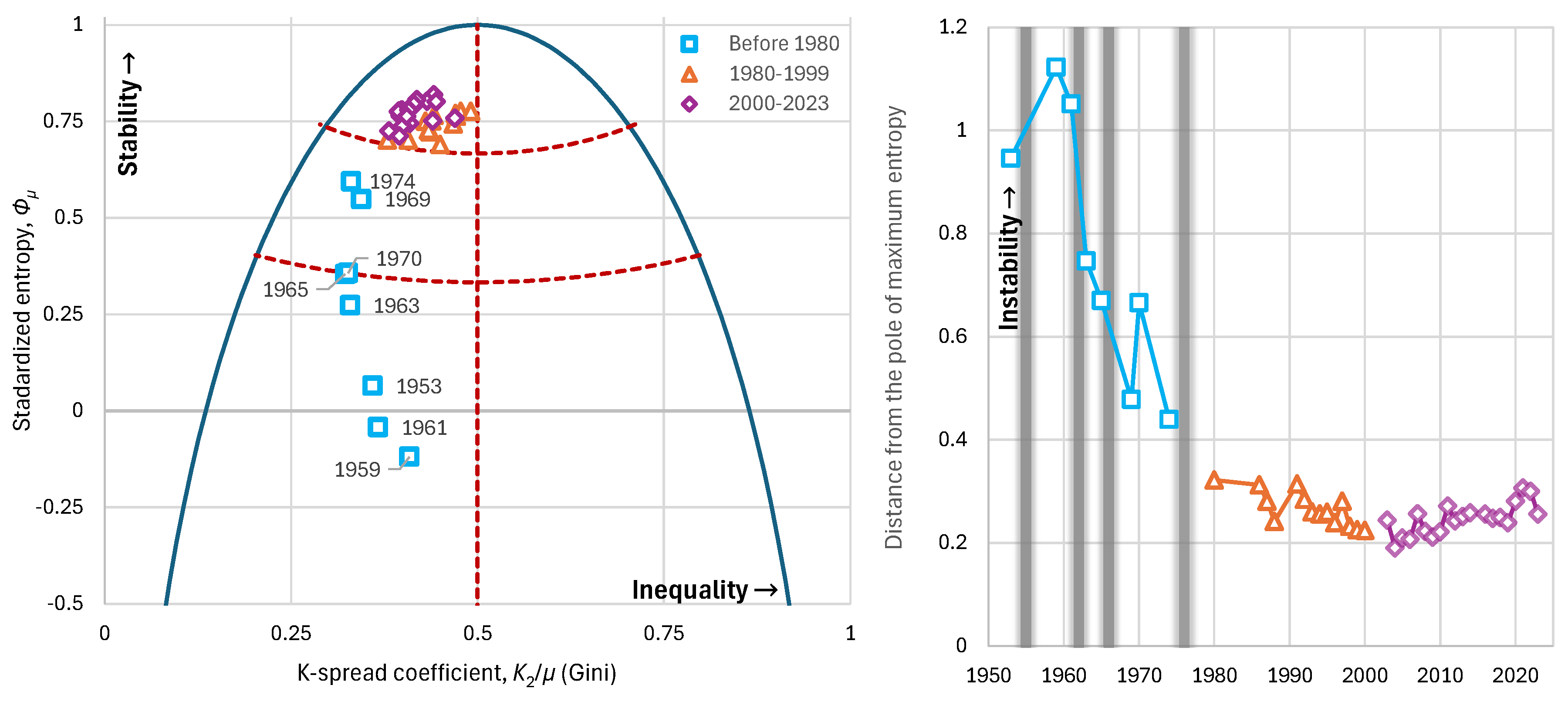

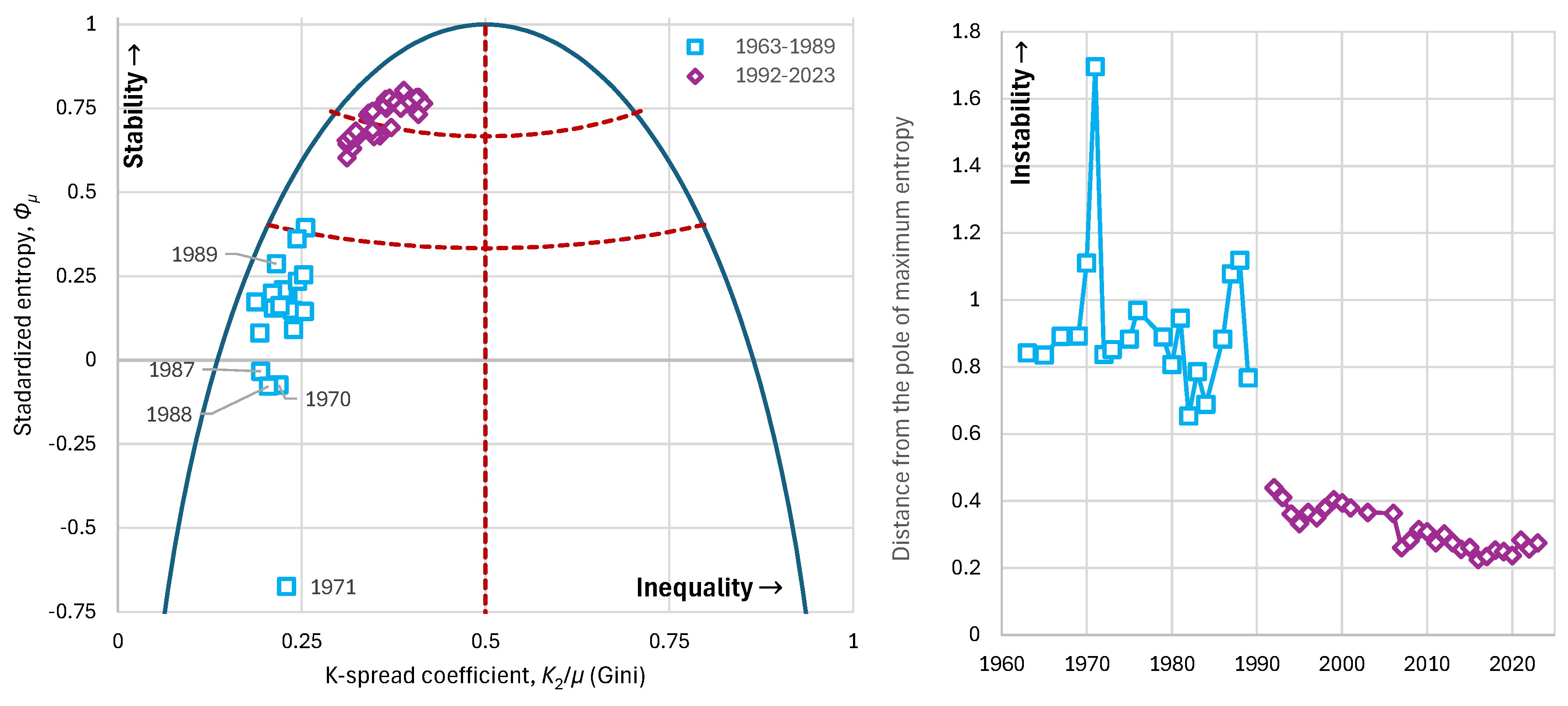

4.3.1. Argentina

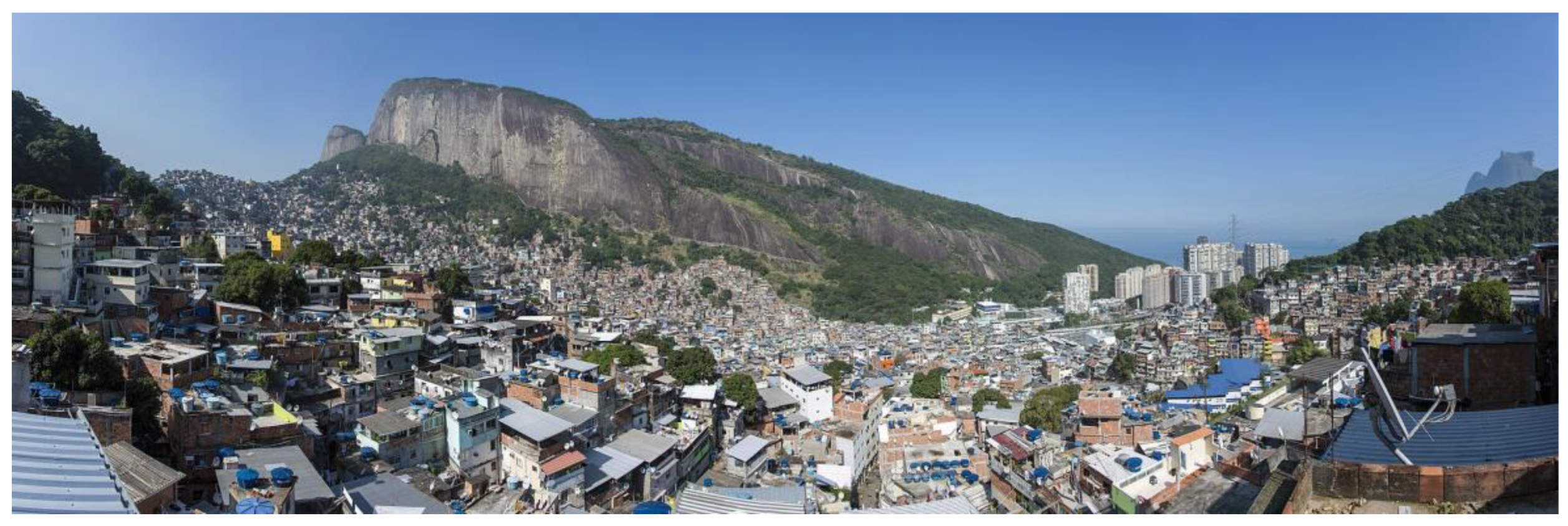

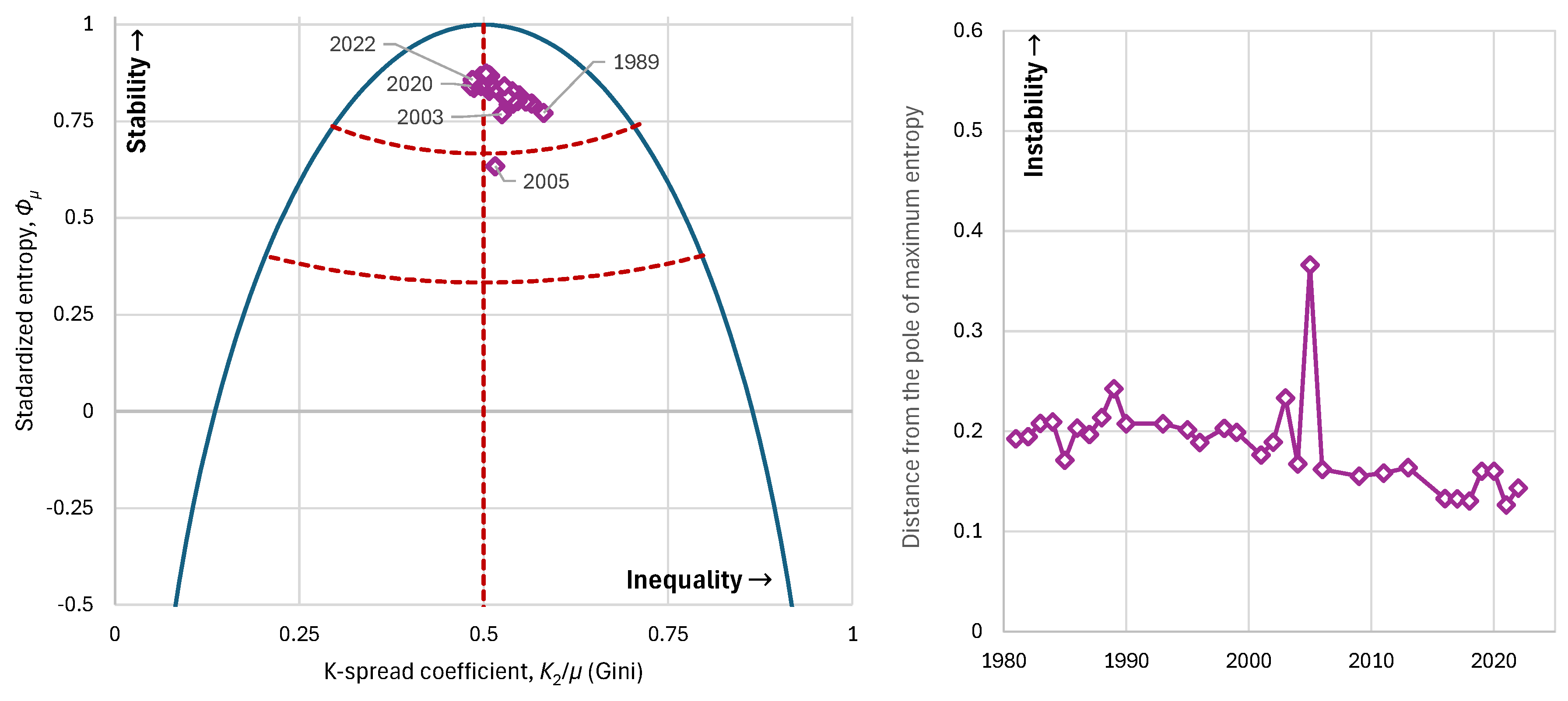

4.3.2. Brazil

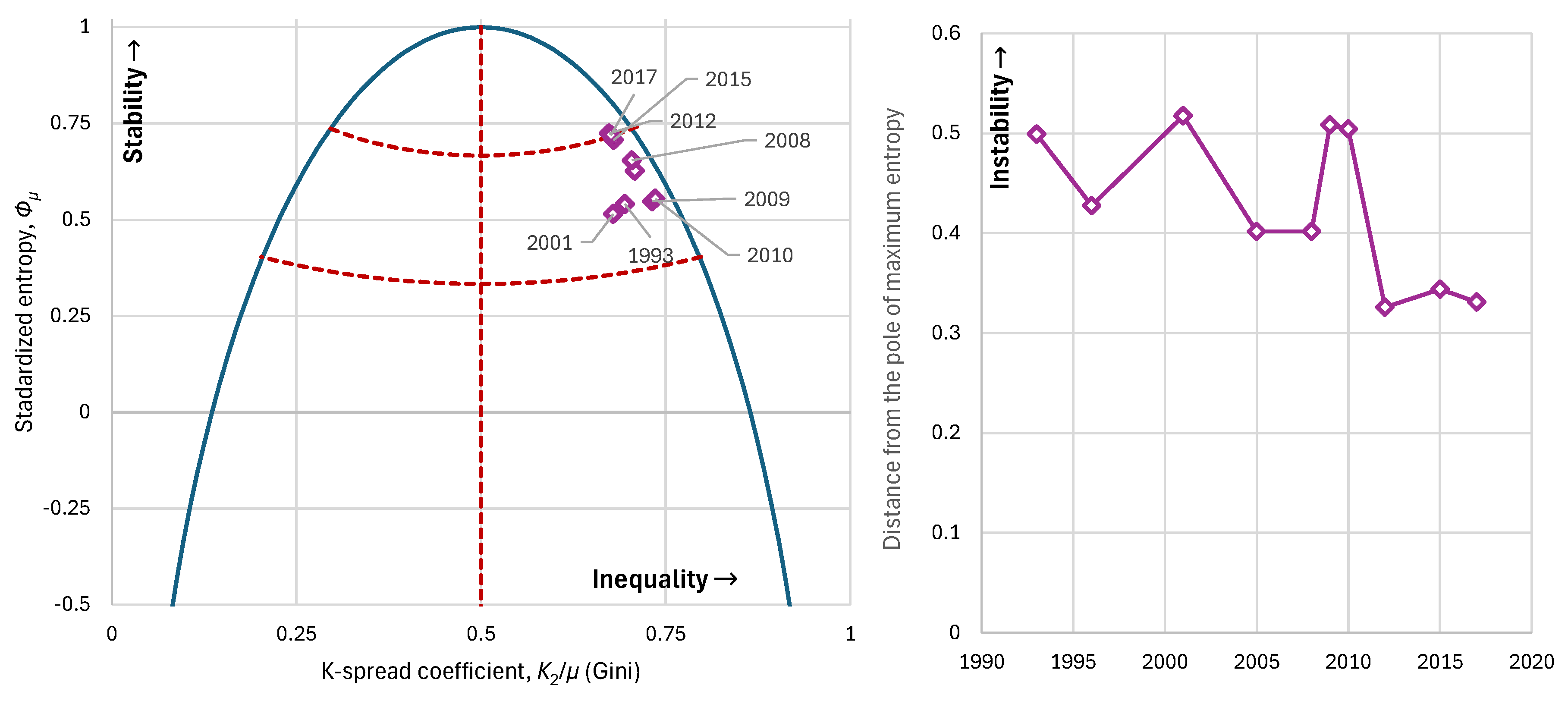

4.3.3. South Africa

4.3.4. Bulgaria

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GDP | Gross domestic product () per capita and () per capita |

| GDP-PPP | Gross domestic product based on purchasing power parity |

| GHL | Generalized half exponential (distribution) |

| LLD | Log-log derivative |

| ME | Maximum entropy |

| PBF | Pareto-Burr-Feller (distribution) |

| WIID | World Income Inequality Database |

Appendix A. Mathematical Derivations

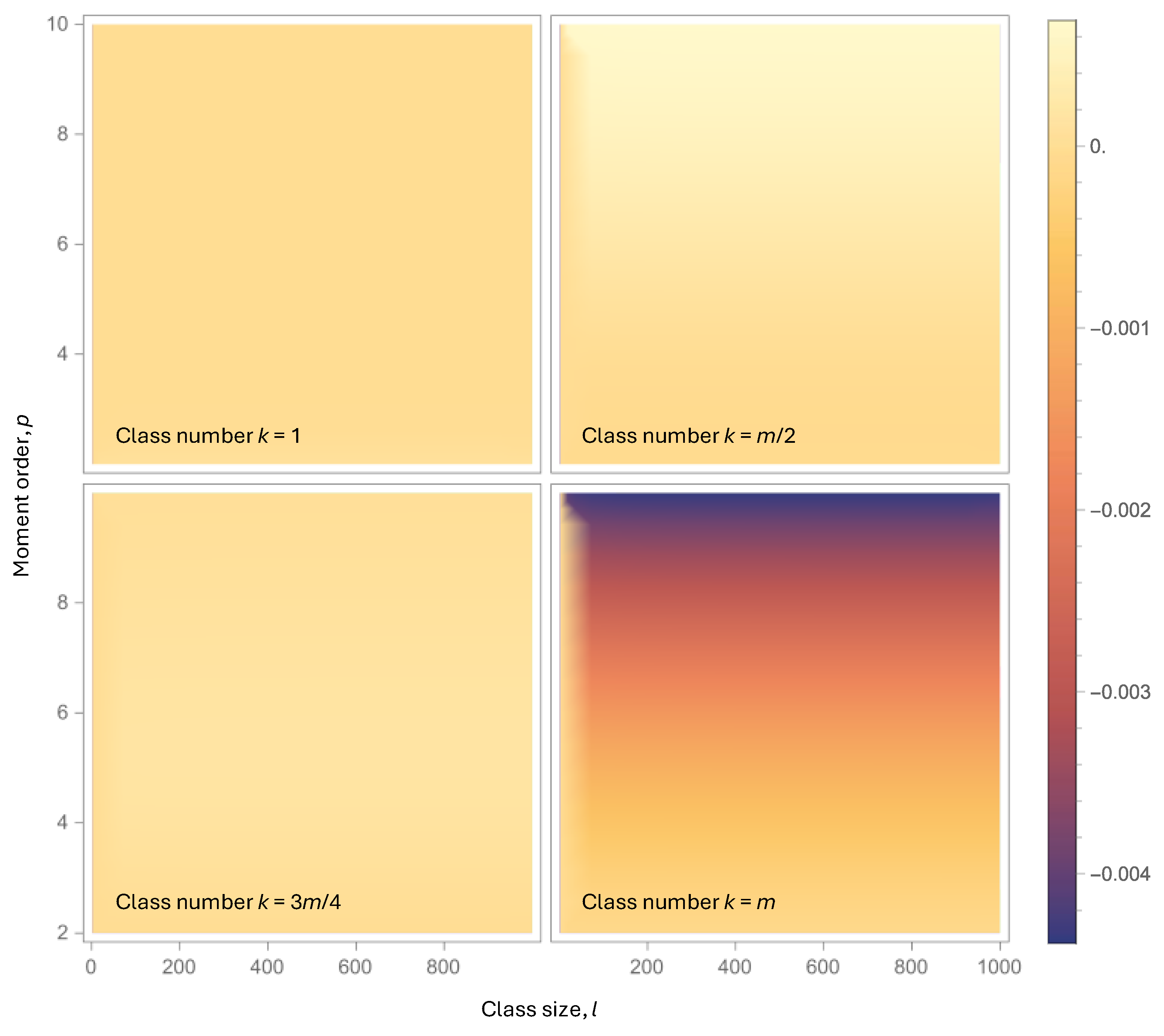

Appendix A.1. Estimation of K-Moments for Data That Are Grouped in Percentiles

Appendix A.2. Derivations about the Lorenz Curve and the Gini Index

| Case | is exact | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| General | |||

| Pareto | |||

| Pareto with shifted origin | |||

| Exponential with shifted origin | |||

| Exponential |

Appendix A.3. Maximum Entropy Distribution for Fixed Mean and Second K-Moment

Appendix A.4. Assignment of Distribution Function Values for the Observed Sample Values

Appendix A.5. Calculation of Empirical Entropy

References

- Aριστοτέλους, Hθικά Νικομάχεια (Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, 1107a.1). https://www.mikrosapoplous.gr/aristotle/nicom2b.htm.

- Koutsoyiannis, D.; Sargentis, G.-F. Entropy and wealth, Entropy 2021, 23 (10), 1356. [CrossRef]

- Jaynes, E.T. Information theory and statistical mechanics. Physical Review 1957, 106(4), 620-630. [CrossRef]

- UNU-WIDER, World Income Inequality Database (WIID) Companion dataset (wiidcountry), Version 29 April 2025. https://doi.org/10.35188/UNUWIDER/WIIDcomp-290425.

- World Income Inequality Database (WIID), WIID Companion User Guide, Available online: https://www.wider.unu.edu/sites/default/files/WIID/WIID-Companion-User-Guide-29April2025.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Shannon, C.E. The mathematical theory of communication. Bell System Technical Journal 1948, 27 (3), 379-423. [CrossRef]

- Jaynes, E.T., 2003. Probability Theory: The Logic of Science, Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, UK, 728 pp.

- Uffink, J. Can the maximum entropy principle be explained as a consistency requirement? Studies In History and Philosophy of Modern Physics 1995, 26 (3), 223-261. [CrossRef]

- Sargentis, G.-F.; Iliopoulou, T.; Dimitriadis, P.; Mamassis, N.; Koutsoyiannis, D. Stratification: An Entropic View of Society’s Structure. World 2021, 2, 153-174. [CrossRef]

- Koutsoyiannis, D. Stochastics of Hydroclimatic Extremes - A Cool Look at Risk, Edition 4, 400 pages, Kallipos, Athens, Greece, 2024, ISBN: 978-618-85370-0-2, 333 pp. https://www.itia.ntua.gr/2000/ (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Marx, K.; Engels, F. The German Ideology; International Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1970; Volume 1, Available online: https://archive.org/details/germanideology00marx/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- World Inequality Report 2022 - Executive Summary. Available online: https://wir2022.wid.world/executive-summary/.

- Global Inequalities – IMF. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2022/03/Global-inequalities-Stanley (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- 2022 Income Inequality Decreased for First Time Since 2007 – Census.gov, Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2023/09/income-inequality.html (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Income and Wealth Inequality in America, 1949-2016 – Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Available online: https://www.minneapolisfed.org/research/institute-working-papers/income-and-wealth-inequality-in-america-1949-2016 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Inequality in China: The Basics. Available online: https://www.csis.org/analysis/how-inequality-undermining-chinas-prosperity#h2-inequality-in-china-the-basics (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Xi Jinping: We must adhere to the people-centred development philosophy. Friends of Socialist China. Available online: https://socialistchina.org/2025/05/02/xi-jinping-we-must-adhere-to-the-people-centred-development-philosophy/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- India ranks 4th globally in income equality, shows World Bank data. Available online: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/india-ranks-4th-globally-in-income-equality-shows-world-bank-data/articleshow/122272852.cms (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- What is the state of inequality in India? - The Hindu. Available online: https://www.thehindu.com/business/Economy/what-is-the-state-of-inequality-in-india/article69805101.ece (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Living conditions in Europe - income distribution and income inequality – Eurostat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Living_conditions_in_Europe_-_income_distribution_and_income_inequality (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Russia Economic Report – World Bank. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/russia/publication/rer (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- GDP per capita (current US$) – China, India, United States, Russian Federation, European Union. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?end=2024&locations=CN-IN-US-RU-EU&start=1960&view=chart (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) – China, India, United States, Russian Federation, European Union. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD?end=2024&locations=CN-IN-US-RU-EU&start=1960&view=chart (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Lewis, D.K. The History of Argentina. Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2014.

- Argentina After World War II: From Peronism to Dictatorship. Available online: https://oercommons.org/courseware/lesson/88088/student-old/?task=2 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Little, W. Party and State in Peronist Argentina, 1945-1955. Hispanic American Historical Review 1973; 53 (4), 644–662. [CrossRef]

- Katie A. Dirty War Argentina [1976–1983]. Britannica. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/event/Dirty-War-Argentina (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Pion-Berlin, D. Argentina: The Journey from Military Intervention to Subordination. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Romero, L.A. A History of Argentina in the Twentieth Century: Updated and revised edition. Penn State Press, 2013.

- Spruk, R. The rise and fall of Argentina. Lat Am Econ Rev 2019, 28, 16. [CrossRef]

- Ferre JC. The Rise of Javier Milei and the Emergence of Authoritarian Liberalism in Argentina. Latin American Research Review, 2025, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Civilian casualties after the air attack and massacre on Plaza de Mayo, June 1955. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Revoluci%C3%B3n_Libertadora#/media/File:Plaza-Mayo-bombardeo-1955.JPG (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Cordobazo. General strike in protest against the political and economic decisions of the military dictatorship. Bulevar San Juan, Córdoba Capital. In that place was murdered that day, the SMATA worker Máximo Mena. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cordobazo#/media/File:Cordobazo.jpg (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Fernando Luiz L.; Koury A.P. In the beginning, there was land. Street Matters: A Critical History of Twentieth-Century Urban Policy in Brazil. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2022, pp. 19–36. [CrossRef]

- Carter M. Social Inequality, Agrarian Reform, and Democracy in Brazil. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5bbd787251f4d47ff1881d9b/t/5cdc38b4a4222fbfda5e7e86/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Fischer, B. (, June 25). Favelas and Politics in Brazil, 1890–1960. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Brazil profile – Timeline. BBC, 3 January 2019. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-19359111 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Panoramic view of Rio's Rocinha favela. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Favela#/media/File:1_rocinha_panorama_2014.jpg (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Library of Congress. Brazil-US Relations. Military Dictatorship (1964-1985). Available online: https://guides.loc.gov/brazil-us-relations/military-dictatorship (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Talarico A. Deeply Divided Brazil. Available online: https://www.beyondintractability.org/casestudy/deeply-divided-brazil (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Klein H.S.; Vidal Luna F. Brazil. An Economic and Social History from Early Man to the 21st Century. Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Michener G.; Pereira C. A Great Leap Forward for Democracy and the Rule of Law? Brazil’s Mensalão Trial. Journal of Latin American Studies 2016, 48(3):477-507. [CrossRef]

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “apartheid”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 17 Sep. 2025, Available online: https://www.britannica.com/topic/apartheid (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- South African History Online. (2016, May 6). A history of Apartheid in South Africa. South African History Online. Available online: https://sahistory.org.za/article/history-apartheid-south-africa (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Larson Z. South Africa: Twenty-Five Years Since Apartheid. Origins. Current Events in Historical Perspective. Available online: https://origins.osu.edu/article/south-africa-mandela-apartheid-ramaphosa-zuma-corruption (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Mandela, N. Long walk to freedom: The autobiography of Nelson Mandela. Hachette UK, 2008. Preview available online: https://books.google.gr/books?hl=en&lr=&id=jc41AQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Netshitenzhe, J. Inequality matters: South African trends and interventions. New Agenda: South African Journal of Social and Economic Policy 2014, 53. Available online: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/na/article/view/111806/101572 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Lawal S. South Africa: 30 years after apartheid, what has changed? Al Jazeera 27 Apr 2024. Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/4/27/south-africa-30-years-after-apartheid-what-has-changed (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Makgetla N. Inequality in South Africa: An overview. September 2020. Available online: https://tips.org.za/images/TIPS_Working_Paper_Inequality_in_South_Africa_An_Overview_September_2020.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- United Nations. Corruption & Economic Crime. Available online: https://dataunodc.un.org/dp-crime-corruption-offences (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- World Bank Group. International Homicides (per 100,000 people) – South Africa. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/VC.IHR.PSRC.P5?locations=ZA (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- United Nations. International homicide. Available online: https://dataunodc.un.org/dp-intentional-homicide-victims (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Global Organized Crime Index. Available online: https://ocindex.net/country/south_africa (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Bulgaria country profile. BBC. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-17202996 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- The History of Communism in Bulgaria. Available online: https://openendedsocialstudies.org/2018/01/11/the-history-of-communism-in-bulgaria/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Todorov A. The state of the right: Bulgaria. Fondation pour l’innovation politique (Fondapol). Available online: https://www.fondapol.org/en/study/the-state-of-the-right-bulgaria/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Zmigrodzki, M. Issues facing the transformation of the political system in Bulgaria, Global Economic Review 1992, 21 (1), 95-108. [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.J.; White, S. Referendums in Russia, the Former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. In: Qvortrup, M. (ed.) Referendums Around the World. Palgrave Macmillan, London2014. [CrossRef]

- Apartment block in district of Sveta Troitsa, Sofia, Bulgaria. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Apartment_block_in_district_of_Sveta_Troitsa,_Sofia,_Bulgaria.jpg (accessed on 1 November 2025).

| Exponential, |

|||||

| Bounded exponential, |

|

||||

| Logistic, |

|||||

| GHL, |

|

||||

| Pareto (), |

|

||||

| Weibull (), |

|||||

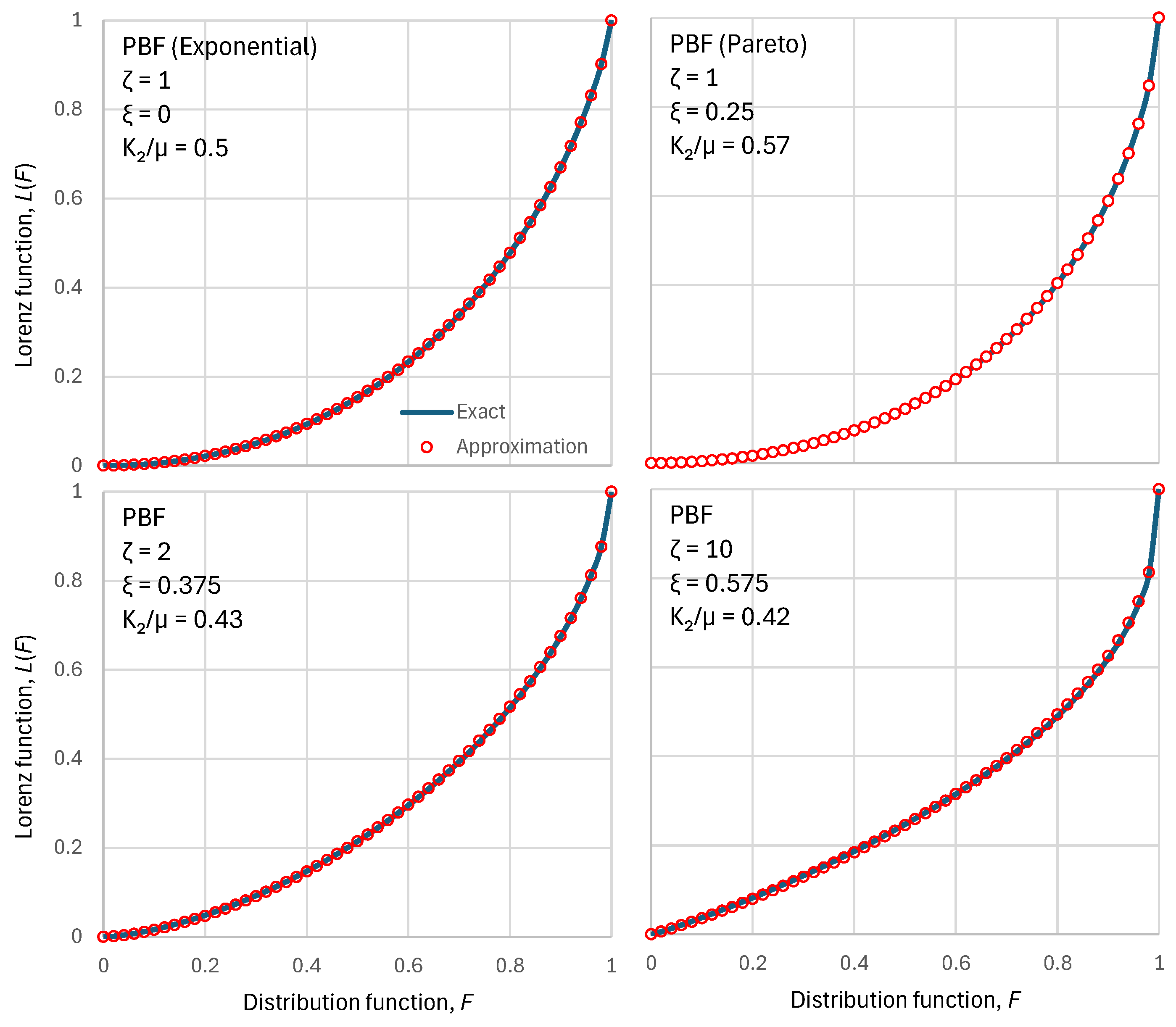

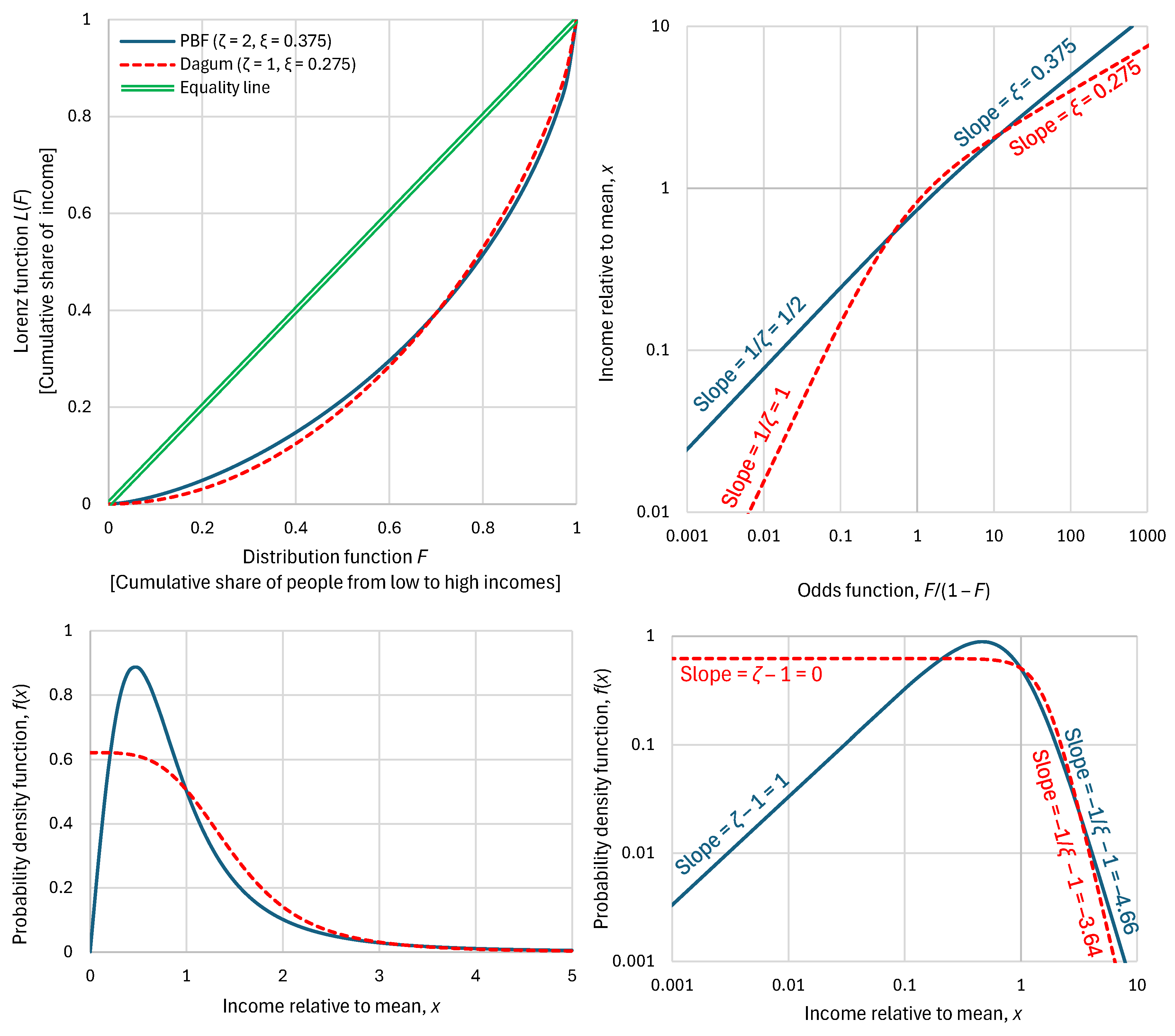

| PBF, |

As |

|

|||

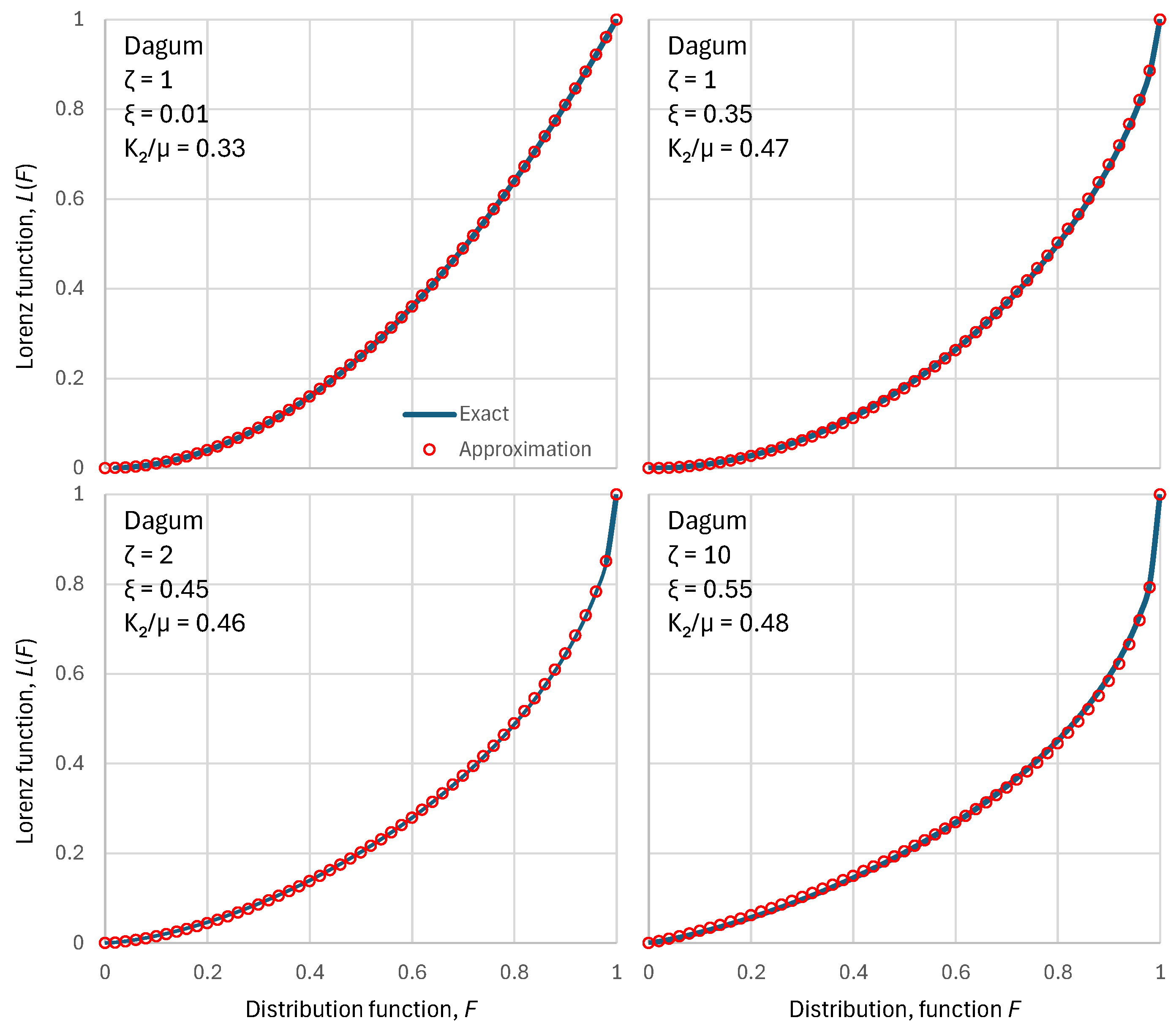

| Dagum, |

|

As |

|

| Country, year | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China, 2022 | 0.44 | 0.89 | 0.12 | 2.97 | 0.34 | 1.98 |

| India, 2022 | 0.49 | 0.89 | 0.15 | 3.13 | 0.50 | 1.02 |

| USA, 2022 | 0.40 | 0.79 | 0.23 | 3.08 | 0.41 | 2.31 |

| Russian Federation, 2022 | 0.35 | 0.72 | 0.32 | 2.97 | 0.31 | 3.48 |

| European Union, 2022 | 0.32 | 0.66 | 0.39 | 3.02 | 0.34 | 1.68 |

| Bulgaria, 1971 | 0.23 | – 0.67 | 1.69 | 3.34 | 0.20 | 5.84 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).