Submitted:

02 November 2025

Posted:

03 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

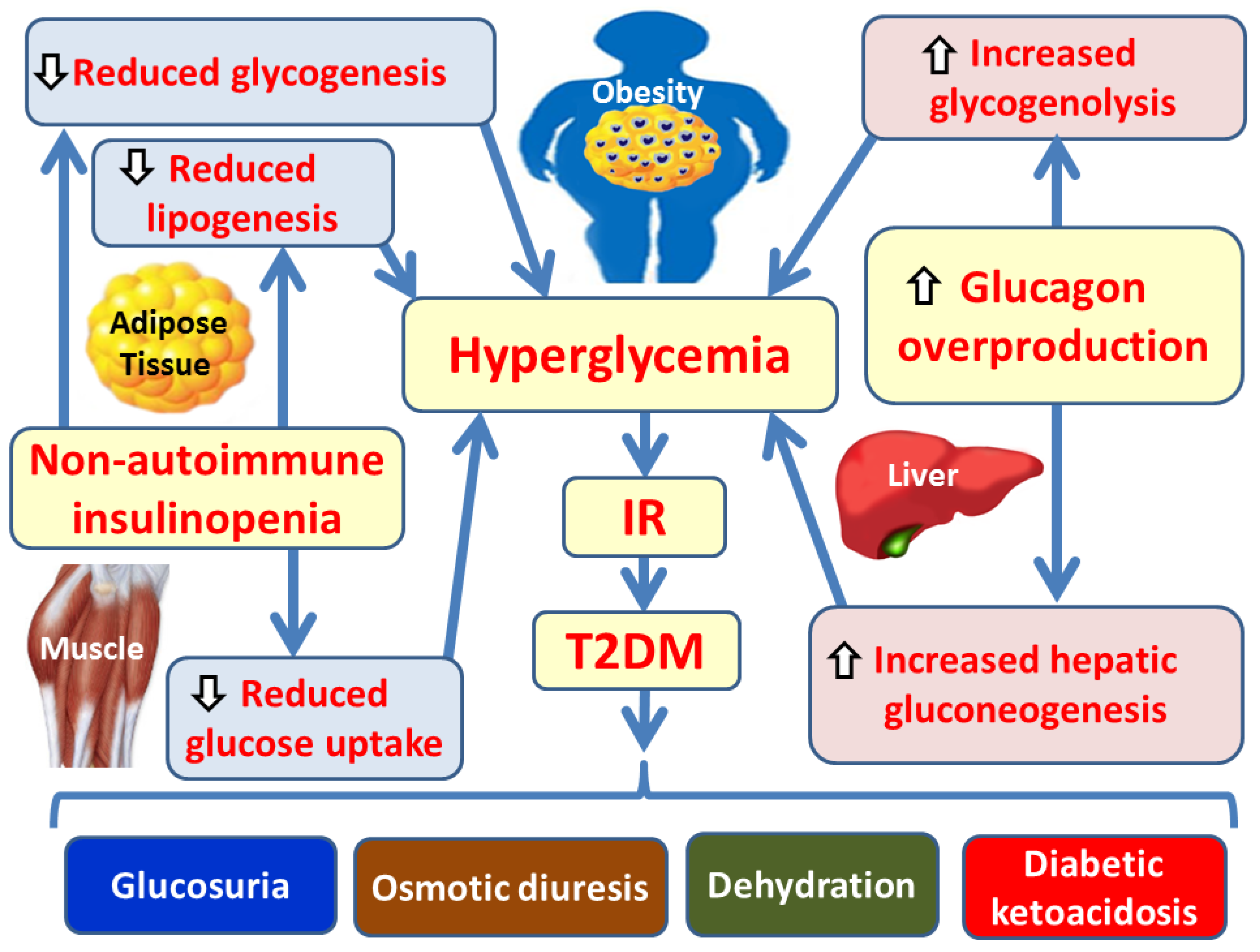

2. Pathophysiology of Obesity-Induced Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

2.1. Insulin Signaling Pathways, IR, and the Pathogenesis of T2DM

2.2. Obesity, Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation, OS and the Pathogenesis of T2DM

2.3. The NF-κB Signaling Pathway in the Pathogenesis of T2DM and Its Complications

2.4. The JAK/STAT Signaling Pathway in the Pathogenesis of T2DM and Its Complications

3. Pathophysiology of T2DM Complications

3.1. Pathophysiological Mechanisms Underlying Diabetic Ketoacidosis

3.2. Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Osmotic Diuresis and Muscle Mass Reduction in T2DM

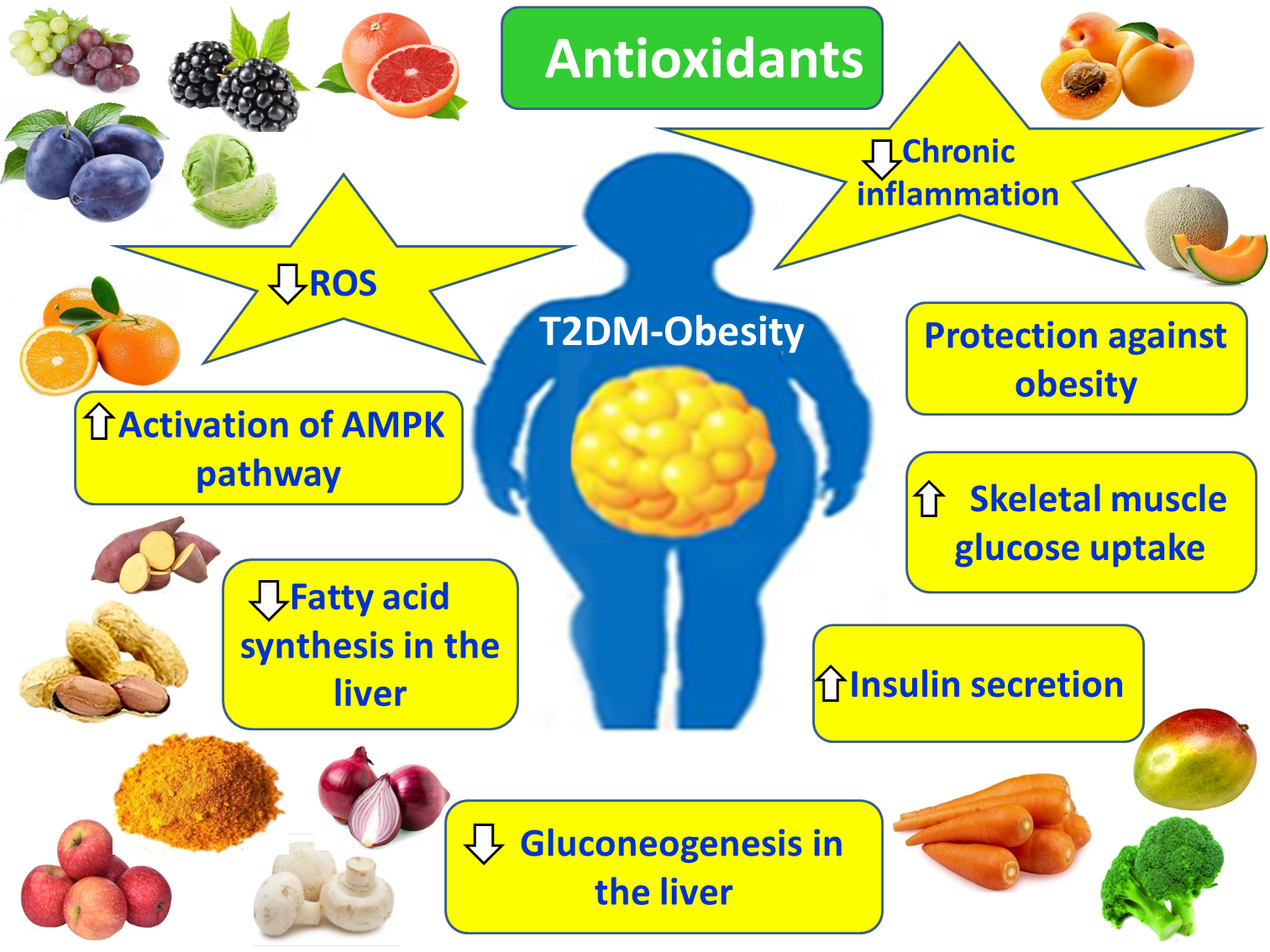

4. Antioxidants in T2DM and the Amelioration of Obesity-Associated T2DM

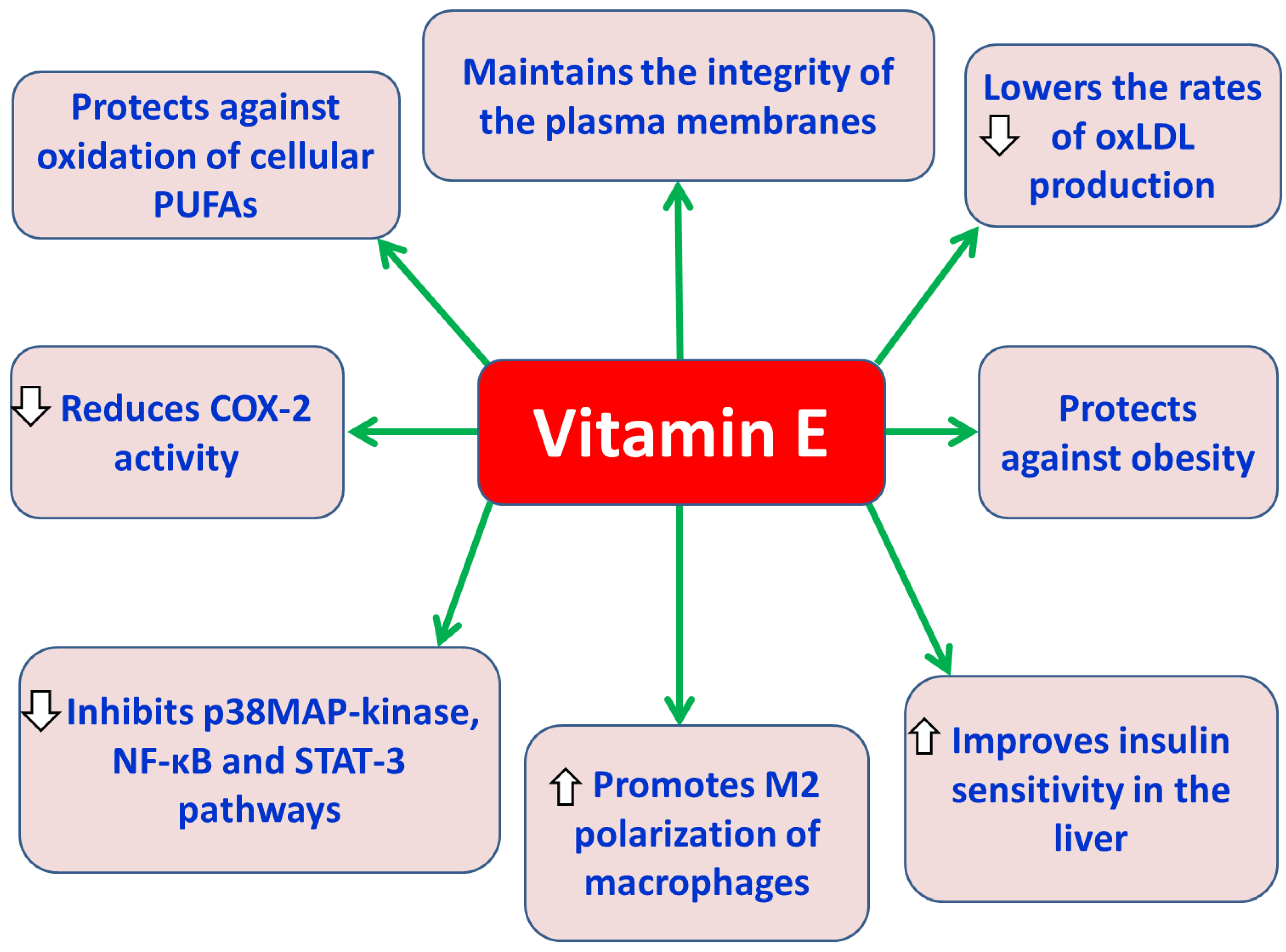

4.1. Vitamin E

4.2. Vitamin C

4.3. N-Acetylcysteine (NAC)

4.4. Zinc

4.5. Alpha-Lipoic Acid

4.6. L-Carnitine

4.7. Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10)

4.8. Superoxide Dismutases (SODs)

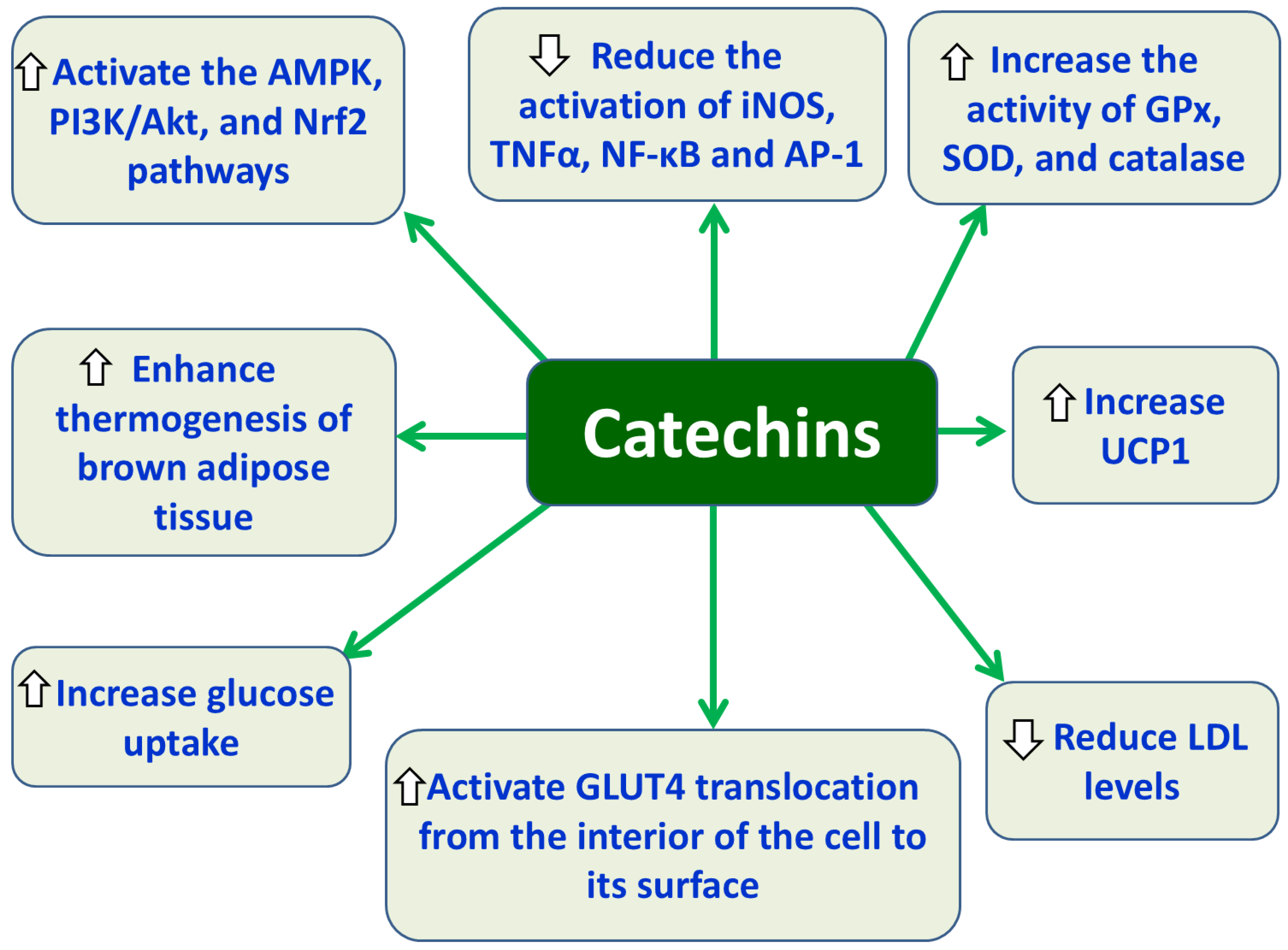

4.9. Catechins

4.10. Quercetin

4.11. Curcumin

4.12. Resveratrol (RSV)

4.13. Lycopene

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author’s Contributions

Funding

Conflict of Interest

References

- Karamanou, M.; Protogerou, A.; Tsoukalas, G.; Androutsos, G.; Poulakou-Rebelakou, E. Milestones in the history of diabetes mellitus: The main contributors. World J. Diabetes 2016, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priya, G.; Kalra, S.; Dasgupta, A.; Grewal, E. Diabetes Insipidus: A Pragmatic Approach to Management. Cureus 2021, 13, e12498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punthakee, Z.; Goldenberg, R.; Katz, P. 2018 Clinical Practice Guidelines Definition, Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes, Prediabetes and Metabolic Syndrome Diabetes Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee. Can. J. Diabetes 2018, 42, S10–S15. https://www.diabetes.ca/health-care-providers/clinical-practice-guidelines/chapter-3#panel-tab_FullText. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solis-Herrera, C.; Triplitt, C.; Reasner, C.; DeFronzo, R.A.; Cersosimo, E. Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Endotext [Internet]. Feingold, K.R., Ahmed, S.F., Anawalt, B., Eds.; MDText.com, Inc: South Dartmouth (MA), 2018; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279119/.

- Yudkin, J.S. “Prediabetes”: Are There Problems With This Label? Yes, the Label Creates Further Problems! Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 1468–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Xie, Q.; Pan, X.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, X.; Peng, G.; et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in adults: pathogenesis, prevention and therapy. Signal Transduct. Targeted. Ther. 2024, 9, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyave, F.; Montaño, D.; Lizcano, F. Diabetes Mellitus Is a Chronic Disease that Can Benefit from Therapy with Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilworth, L.; Facey, A.; Omoruyi, F. Diabetes Mellitus and Its Metabolic Complications: The Role of Adipose Tissues. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodosis-Nobelos, P.; Rekka, E.A. The Antioxidant Potential of Vitamins and Their Implication in Metabolic Abnormalities. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caturano, A.; Rocco, M.; Tagliaferri, G.; Piacevole, A.; Nilo, D.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Iadicicco, I.; Donnarumma, M.; Galiero, R.; Acierno, C.; et al. Oxidative Stress and Cardiovascular Complications in Type 2 Diabetes: From Pathophysiology to Lifestyle Modifications. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knudsen, J.G.; Hamilton, A.; Ramracheya, R.; Tarasov, A.I.; Brereton, M.; Haythorne, E.; et al. Dysregulation of Glucagon Secretion by Hyperglycemia-Induced Sodium-Dependent Reduction of ATP Production. Cell Metab. 2019, 29, 430–442.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hædersdal, S.; Lund, A.; Knop, F.K.; Vilsbøll, T. The Role of Glucagon in the Pathophysiology and Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2018, 93, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouri, M.; Badireddy, M. Hyperglycemia. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2023; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK4309.

- Gosmanov, A.R.; Gosmanova, E.O.; Kitabchi, A.E. Hyperglycemic Crises: Diabetic Ketoacidosis and Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar State. Endotext [Internet]. Feingold, K.R., Ahmed, S.F., Anawalt, B., et al., Eds.; MD Text.com, Inc: South Dartmouth (MA), 2021; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279052/.

- Varra, F.-N.; Varras, M.; Varra, V.-K.; Theodosis-Nobelos, P. Molecular and pathophysiological relationship between obesity and chronic inflammation in the manifestation of metabolic dysfunctions and their inflammation-mediating treatment options (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2024, 29, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L. Alterations of gut microbiota by overnutrition impact gluconeogenic gene expression and insulin signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poitout, V.; Robertson, R.P. Glucolipotoxicity: fuel excess and β-cell dysfunction. Endocr. Rev. 2008, 29, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, G.C.; Bonner-Weir, S. Five stages of evolving beta-cell dysfunction during progression to diabetes. Diabetes 2004, 53, S16–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Gong, M.; Wu, N. Research progress on the relationship between free fatty acid profile and type 2 diabetes complicated by coronary heart disease. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2024, 15, 1503704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altalhi, R.; Pechlivani, N.; Ajjan, R.A. PAI-1 in Diabetes: Pathophysiology and Role as a Therapeutic Target. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guria, S.; Hoory, A.; Das, S.; Chattopadhyay, D.; Mukherjee, S. Adipose tissue macrophages and their role in obesity-associated insulin resistance: an overview of the complex dynamics at play. Biosci. Rep. 2023, 43, BSR20220200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.; Kono, T.; Evans-Molina, C. The role of peroxisome proliferatoractivated receptor γ in pancreatic β cell function and survival: therapeutic implications for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2010, 12, 1036–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadi, M.; Aziz, S.G.-G.; Nade, R. The effect of tropisetron on oxidative stress, SIRT1, FOXO3a, and claudin-1 in the renal tissue of STZ-induced diabetic rats. Cell Stress Chaperones 2021, 26, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, C.; Fu, Y.; Xie, L.; Kong, Y.; Yang, X. Inflammation, Apoptosis, and Fibrosis in Diabetic Nephropathy: Molecular Crosstalk in Proximal Tubular Epithelial Cells and Therapeutic Implications. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Q.; Yang, C. Oxidative stress and diabetic retinopathy: molecular mechanisms, pathogenetic role and therapeutic implications. Redox Biol. 2020, 37, 101799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingueti, C.P.; Dusse, M.S.; Carvalho, M.G.; de Sousa, L.P.; Gomes, K.B.; Fernandes, A.P. Diabetes mellitus: The linkage between oxidative stress, inflammation, hypercoagulability and vascular complications. J. Diabetes Complications 2016, 30, 738–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Wu, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Yan, Y.; Zhu, M.; et al. Oxidative stress induced by NOX2 contributes to neuropathic pain via plasma membrane translocation of PKCε in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J. Neuroinflammation 2021, 18, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Zhang, Y.-H.; Wang, C.-Y.; Yu, Y.; Li, Y.-Z.; Cui, W.; et al. MicroRNA-7a-5p ameliorates diabetic peripheral neuropathy by regulating VDAC1/JNK/c-JUN pathway. Diabet. Med. 2023, 40, e14890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, S.A.; Massry, M.E.I.; Hichor, M.; Haddad, M.; Grenier, J.; Dia, B.; et al. Targeting the NADPH oxidase-4 and liver X receptor pathway preserves Schwann cell integrity in diabetic mice. Diabetes 2020, 69, 448–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villalobos-Labra, R.; Subiabre, M.; Toledo, F.; Pardo, F.; Sobrevia, L. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and development of insulin resistance in adipose, skeletal, liver, and foetoplacental tissue in diabesity. Mol. Asp. Med. 2019, 66, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Peng, J.; Han, G.-H.; Ding, X.; Wei, S.; Gao, G.; et al. Role of macrophages in peripheral nerve injury and repair. Neural Regen. Res. 2019, 14, 1335–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Wu, N.; Zhao, D. Function of NLRP3 in the Pathogenesis and Development of Diabetic Nephropathy. Med. Sci. Monit. 2017, 23, 3878–3884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matoba, K.; Takeda, Y.; Nagai, Y.; Kawanami, D.; Utsunomiya, K.; Nishimura, R. Unraveling the role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of diabetic kidney disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3393–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, M.L.; Ho, F.M.; Yang, R.S.; Chao, K.F.; Lin, W.W.; Lin-Shiau, S.Y.; Liu, S.-H. High glucose induces human endothelial cell apoptosis through a phosphoinositide 3-kinase-regulated cyclooxygenase-2 pathway. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2005, 25, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-Y.; Yiang, G.-T.; Lai, T.-T.; Li, C.-J. The oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction during the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2018, 2018, 3420187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaurasia, S.S.; Lin, R.R.; Parikh, B.H.; Wey, Y.S.; Tun, B.B.; Wong, T.Y.; et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome may contribute to pathologic neovascularization in the advanced stages of diabetic retinopathy. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Zhao, H.; Song, H. Shared signaling pathways and targeted therapy by natural bioactive compounds for obesity and type 2 diabetes. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 64, 5039–5056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bako, H.Y.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Isah, M.S.; Ibrahim, S. Inhibition of JAK-STAT and NF-κB signalling systems could be a novel therapeutic target against insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Life Sci. 2019, 239, 117045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Nair, V.; Saha, J.; Atkins, K.B.; Hodgin, J.B.; et al. Podocyte-specific JAK2 overexpression worsens diabetic kidney disease in mice. Kidney Int 2017, 92, 909–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Han, Y.; Zhao, F.; Zhao, Z.; Tian, J.; Jia, K. Nobiletin suppresses high-glucose-induced inflammation and ECM accumulation in human mesangial cells through STAT3/NF-κB pathway. J. Cell Biochem. 2019, 120, 3467–3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.G.; Luckett-Chastain, L.R.; Calhoun, K.N.; Frempah, B.; Bastian, A.; Gallucci, R.M. Interleukin 6 function in the skin and isolated keratinocytes is modulated by hyperglycemia. J. Immunol. Res. 2019, 2019, 5087847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawaya, A.P.; Stone, R.C.; Brooks, S.R.; Pastar, I.; Jozic, I.; Hasneen, K.; et al. Deregulated immune cell recruitment orchestrated by FOXM1 impairs human diabetic wound healing. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, R.; Singhal, M.; Jialal, I. Type 2 Diabetes. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513253/.

- Liakopoulos, V.; Franzén, S.; Svensson, A.M.; Miftaraj, M.; Ottosson, J.; Näslund, I.; Gudbjörnsdottir, S.; Eliasson, B. Pros and cons of gastric bypass surgery in individuals with obesity and type 2 diabetes: nationwide, matched, observational cohort study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e023882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patoulias, D.; Papadopoulos, C.; Stavropoulos, K.; Zografou, I.; Doumas, M.; Karagiannis, A. Prognostic value of arterial stiffness measurements in cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and its complications: The potential role of sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors. J. Clin. Hypertens. (Greenwich) 2020, 22, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poznyak, A.; Grechko, A.V.; Poggio, P.; Myasoedova, V.A.; Alfieri, V.; Orekhov, A.N. The Diabetes Mellitus–Atherosclerosis Connection: The Role of Lipid and Glucose Metabolism and Chronic Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushner, A.; West, W.P.; Suheb, M.Z.K.; Pillarisetty, L.S. Virchow Triad. StatPearls [Internet].Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2024. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539697/.

- Chiu, J.-J.; Chien, S. Effects of Disturbed Flow on Vascular Endothelium: Pathophysiological Basis and Clinical Perspectives. Physiol. Rev. 2011, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yachmaneni, A. Jr.; Jajoo, S.; Mahakalkar, C.; Kshirsagar, S.; Dhole, S. A Comprehensive Review of the Vascular Consequences of Diabetes in the Lower Extremities: Current Approaches to Management and Evaluation of Clinical Outcomes. Cureus 2023, 15, e47525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodman, M.A.; Dreyer, M.A.; Varacallo, M.A. Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2024. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK442009/.

- Akkus, G.; Sert, M. Diabetic foot ulcers: A devastating complication of diabetes mellitus continues non-stop in spite of new medical treatment modalities. World J. Diabetes 2022, 13, 1106–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, K.; Anno, T.; Kimura, Y.; Kawasaki, F.; Kaku, K.; Tomoda, K.; Kaneto, H. Pathology of Ketoacidosis in Emergency of Diabetic Ketoacidosis and Alcoholic Ketoacidosis: A Retrospective Study. J. Diabetes Res. 2024, 2024, 8889415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talley, J.T.; Mohiuddin, S.S. Biochemistry, Fatty Acid Oxidation StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2023. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556002/.

- Kolb, H.; Kempf, K.; Röhling, M.; Lenzen-Schulte, M.; Schloot, N.C.; Martin, S. Ketone bodies: from enemy to friend and guardian angel. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizzo, J.M.; Goyal, A.; Gupta, V. Adult Diabetic Ketoacidosis. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2023. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560723/.

- Ghimire, P.; Dhamoon, A.S. Ketoacidosis. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2023. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534848/.

- Self, W.H.; Evans, C.S.; Jenkins, C.A.; Brown, R.M.; Casey, J.D.; Collins, S.P. Clinical Effects of Balanced Crystalloids vs Saline in Adults With Diabetic Ketoacidosis: A Subgroup Analysis of Cluster Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2024596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, B.F.; Clegg, D.J. Electrolyte and Acid–Base Disturbances in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 548–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, P.H.I.; Mohebbi, N. Kidney metabolism and acid–base control: back to the basics. Pflugers Arch. 2022, 474, 919–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Hashmi, M.F.; Aggarwal, S. Hyperchloremic Acidosis. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2023. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482340/.

- Elendu, C.; David, J.A.; Udoyen, A.-O.; Egbunu, E.O.; Ogbuiyi-Chima, I.C.; Unakalamba, L.O.; et al. Comprehensive review of diabetic ketoacidosis: an update. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2023, 85, 2802–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liman, M.N.P.; Jialal, I. Physiology, Glycosuria. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2023. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557441/.

- Hieshima, K.; Sugiyama, S.; Yoshida, A.; Kurinami, N.; Suzuki, T.; Ijima, H.; et al. Elevation of the renal threshold for glucose is associated with insulin resistance and higher glycated hemoglobin levels. J. Diabetes Investig. 2020, 11, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hans, F. Polyuria and Diabetes: Understanding the Connection and Implications. Afr. J. Diabetes Med. 2024, 32, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Vallon, V. Glucose transporters in the kidney in health and disease. Pflugers Arch 2020, 472, 1345–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubbi, S.; Hannah-Shmouni, F.; Koch, C.A.; Joseph, G.; Verbalis, J.G. Diagnostic Testing for Diabetes Insipidus. Endotext [Internet]; Feingold, K.R., Ahmed, S.F., Anawalt, B., et al., Eds.; MDText.com, Inc: South Dartmouth (MA), 2022; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537591/.

- Wendt, A.; Eliasson, L. Pancreatic alpha cells and glucagon secretion: Novel functions and targets in glucose homeostasis. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2022, 63, 102199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RR; Corriere, M.; Ferrucci, L. Age-related and disease-related muscle loss: the effect of diabetes, obesity, and other diseases. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014, 2, 819–829. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, K.; Qi, G.; Liu, H.; Wang, W.; et al. Diabetic Muscular Atrophy: Molecular Mechanisms and Promising Therapies. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 917113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaffarin, A.S.; Ng, S.-F.; Ng, M.H.; Hassan, H.; Alias, E. Pharmacology and pharmacokinetics of vitamin E: Nanoformulations to enhance bioavailability. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2020, 15, 9961–9974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szewczyk, K.; Chojnacka, A.; Górnicka, M. Tocopherols and tocotrienols – bioactive dietary compounds. What is certain, what is doubt? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, S.; Omage, S.O.; Börmel, L.; Kluge, S.; Schubert, M.; Wallert, M.; Lorkowski, S. Vitamin E and metabolic health: relevance of interactions with other micronutrients. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccioni, G.; Bucciarelli, T.; Mancini, B.; Corradi, F.; Di Ilio, C.; Mattei, P.A.; D’Orazio, N. Antioxidant vitamin suppementation in cardiovascular diseases. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2007, 37, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Theodosis-Nobelos, P.; Papagiouvannis, G.; Rekka, E.A. A Review on Vitamin E Natural Analogues and on the Design of Synthetic Vitamin E Derivatives as Cytoprotective Agents. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2021, 21, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galmes, S.; Serra, F.; Paou, A. Vitamin E metabolic effects and genetic variants: A challenge for precision nutrition in obesity and associated disturbances. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, E.D.; Meydani, S.N.; Wu, D. Regulatory role of vitamin E in the immune system and inflammation. IUBMB Life 2019, 71, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohoe, F.; Wilkinson, M.; Baxter, E.; Brennan, D.J. Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and obesity-related cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q. Natural forms of vitamin E: metabolism, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities and the role in disease prevention and therapy. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 72, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanchi, M.M.; Shanmugam, M.K.; Rane, G.; Sethi, G.; Kumar, A.P. Tocotrienols: the unsaturated sidekick shifting new paradigms in vitamin E therapeutics. Drug Discov. Today 2017, 22, 1765–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, S.K.; Chin, K.-Y.; Suhaimi, F.H.; Ahmad, F.; Ima-Nirwana, S. Vitamin E as a potential interventional treatment for metabolic syndrome: evidence from animal and human studies. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcalá, M.; Sanchez-Vera, I.; Sevillano, J.; Herrero, L.; Serra, D.; Ramos, M.P.; Viana, M. Vitamin E reduces adipose tissue fibrosis, inflammation, and oxidative stress and improves metabolic profile in obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015, 23, 1598–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budin, S.B.; Othman, F.; Louis, S.R.; Bakar, M.A.; Das, S.; Mohamed, J. The effects of palm oil tocotrienol-rich fraction supplementation on biochemical parameters, oxidative stress and the vascular wall of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Clinics 2009, 64, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Kang, I.; Fang, X.; Wang, W.; Lee, M.A.; Hollins, R.R.; Marshall, M.R.; Chung, S. Gamma-tocotrienol attenuates high-fat diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance by inhibiting adipose inflammation and M1 macrophage recruitment. Int J Obes (Lond) 2015, 39, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tun, S.; Spainhower, C.J.; Cottrill, C.L.; Lakhani, H.V.; Pillai, S.S.; Dilip, A.; Chaudhry, H.; Shapiro, J.I.; Sodhi, K. Therapeutic Efficacy of Antioxidants in Ameliorating Obesity Phenotype and Associated Comorbidities. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.; Jamil, R.J.; Attia, J.F. Vitamin C (ascorbic acid). In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499877/.

- Rafighi, Z.; Shiva, A.; Arab, S.; Mohd, Y.R. Association of dietary vitamin C and E intake and antioxidant enzymes in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2013, 5, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naziroğlu, M.; Simşek, M.; Simşek, H.; Aydilek, N.; Ozcan, Z.; Atilgan, R. The effects of hormone replace therapy combined with vitamins C and E on antioxidants levels and lipid profiles in postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes. Clin Chim Acta 2004, 344, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, A.H.; Wareham, N.J.; Binham, S.A.; Khaw, K.T.; Luben, R.; Welch, A.; et al. Plasma vitamin C level, fruit and vegetabel consumption, and the risk of new-onset type 2 diabetes mellitus: the European prospective investigation of cancer – Norfolk prospective study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008, 168, 1493–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerini, M.; Gondrò, G.; Friuli, V.; Maggi, L.; Perugini, P. N-acetylcystein (NAC) and its role in clinical practice management of cystic fibrosis (CF): a review. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2022, 15, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Ju, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wang, T. N-acetylcysteine improves oxidative stress and inflammatory response in patients with community acquired pneumonia: a randomized controlled trial. Medicina (Baltimore) 2018, 97, e13087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y.; Liu, H.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Tay, F.R. Biological activities and potential oral applications of N-acetylcystein: Progress and prospects. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 2835787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarty, M.F.; O’Keefe, J.H.; DiNicolantonio, J.J. Dietary Glycine Is Rate-Limiting for Glutathione Synthesis and May Have Broad Potential for Health Protection. Ochsner J. 2018, 18, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, B.; Vicenzi, M.; Garrel, C.; Denis, F.M. Effects of N-acetylcysteine, oral glutathione (GSH) and a novel sublingual form of GSH on oxidative stress markers: A comparative crossover study. Redox Biol. 2015, 6, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Hazra, A.; Paul, P.; Saha, B.; Roy, S.; Bhowmick, P.; Bhowmick, M. Formulation and evaluation of n-acetyl cysteine loaded bi-polymeric physically crosslinked hydrogel with antibacterial and antioxidant activity for diabetic wound dressing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 135418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dludla, P.V.; Mazibuko-Mbeje, S.E.; Nyambuya, T.M.; Mxinwa, V.; Tiano, L.; Marcheggiani, F.; et al. The beneficial effects of N-acetyl cystein (NAC) against obesity associated complications: A systematic review of pre-clinical studies. Pharmacol. Res. 2019, 146, 104332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismael, M.A.; Talbot, S.; Carbonneau, C.L.; Beauséjour, C.M.; Couture, R. Blockade of sensory abnormalities and kinin B1 receptor expression by N-Acetyl-L-Cystein and ramipril in a rat model of insulin resistance. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 589, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Mao, X.; Li, H.; Qiao, S.; Xu, A.; Wang, J.; et al. N-Acetylcysteine and allopurinol up-regulated the Jak/STAT3 and PI3K/Akt pathways via adiponectin and attenuated myocardial postischemic injury in diabetes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 63, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadota, Y.; Toriuchi, Y.; Aki, Y.; Mizuno, Y.; Kawakami, T.; Nakaya, T.; et al. Metallothioneins regulate the adipoogenic defferentation of 3T3-L1 cells via the insulin signaling pathway. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0176079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Song, P.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y. Clinical efficacy of acetylcysteine combined with tetrandrine tablets in the treatment of silicosis and the effect on serum IL-6 and TNF-alpha. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019, 18, 3383–3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, W.; Shu, H.; Wen, Z.; Liu, J.; Jin, Z.; Shi, Z.; et al. N-acetyl cysteine ameliorates high-fat diet-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and intracellular triglyceride accumulation by preserving mitochondral function. Front Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 636204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korou, L.M.; Agrogiannis, G.; Koros, C.; Kitraki, E.; Vlachos, I.S.; Tzanetakou, I.; et al. Impact of N-acetylcysteine and sesame oil on lipid metabolism and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis homeostasis in middle-aged hypercholesterolemic mice. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 6806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masselli, E.; Pozzi, G.; Vaccarezza, M.; Mirandola, P.; Galli, D.; Vitale, M.; et al. ROS in platelet biology: functional aspects and methodological insights. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 2, 4866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, R.J.; Sontakke, T.; Biradar, A.; Nalage, D. Zinc: an essential trace element for human health and beyond. Food Health 2023, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, E.B.; Gildergorin, G. Zinc status affects glucose homeostasis and insulin secretion in patients with thalassemia. Nutrients 2015, 7, 4296–4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruttkay-Nedecky, B.; Nejdl, L.; Gumulec, J.; Zitka, O.; Masarik, M.; Eckschlager, T.; et al. The role of metallothionein in oxidative stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 6044–6066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, I.G.; Moran, J.F.; Becana, M.; Montoya, G. The crystal structure of an eukaryotic iron superoxide dismutase suggests intersubunit cooperation during catalysis. Protein Sci. 2005, 14, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- do Nascimento Marreiro, D.; Clímaco Cruz, K.J.; Silva Morais, J.B.; Batista Beserra, J.; Soares Severo, J.; de Oliveira, A.R.S. Zinc and oxidative stress: current mechanisms. Antioxidants (Basel) 2017, 6, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Maret, W. Zinc in cellular regulation: The nature and significance of “zinc signals”. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukunaka, A.; Fujitani, Y. Role of zinc homeostasis in the pathogenesis of diabetes and obesity. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, I.C.; Mititelu-Tartau, L.; Popa, E.G.; Poroch, M.; Poroch, V.; Pelin, A.M.; et al. Zinc chloride endances the antioxidant status, improving the functional and structural organic disturbances in streptozotocin-induced diabetes in rats. Medicina 2022, 58, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Yin, G.; Li, Q.Q.; Zeng, Q.; Duan, J. Diabetes mellitus causes male reproductive dysfunction: a review of the evidence and mechanisms. In vivo 2021, 35, 2503–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, W.; Zheng, W.; Fang, X.; Chen, L.; Rink, L.; et al. Zinc supplementation improves glycemic control for diabetes prevention and management: a systemic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 110, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, M.; Samman, S. Zinc and regulation of inflammatory cytokines: implications for cardiometabolic disease. Nutrients 2012, 4, 676–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, A.; Jiang, W.; Wang, X.; Shahid, S.; Saba, N.; Ahmad, M.; et al. Mechanistic impact of zinc deficiency in human development. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 717064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younus, H. Therapeutic potentials of superoxide dismutase. Int. J. Health Sci. (Qassim) 2018, 12, 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- Dajnowicz-Brzezik, P.; Żebrowska, E.; Maciejczyk, M.; Zalewska, A.; Chabowski, A. α -lipoic acid supplementation reduces oxidative stress and inflammation in red skeletal muscle of insulin-resistant rats. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2025, 742, 151107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdali, D.; Samson, S.; Grover, A.K. How effective are antioxidant supplements in obesity and diabetes? Med. Princ. Pract. 2015, 24, 201–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Yilmaz, Y.B.; Antika, G.; Tumer, T.B.; Mahomoodally, M.F.; Lobine, D.; et al. Insights on the use of α-lipoic acid for therapeutic purposes. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Superti, F.; Russo, R. Alpha-Lipoic Acid: Biological Mechanisms and Health Benefits. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahid, A.; Nasir, K.; Bhatia, M. Therapeutic Potential of Alpha-Lipoic Acid: Unraveling Its Role in Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Conditions. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amrousy, D.E.; El-Afify, D. Effects of alpha lipoic acid as a supplement in obese children and adolescents. Cytokine 2020, 130, 155084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansar, H.; Mazloom, Z.; Kazemi, F.; Hejazi, N. Effect of α-lipoic acid on blood glucose, insulin resistance and glutathione peroxidase of type 2 diabetic patients. Saudi Med. J. 2011, 32, 584–588. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Han, P.; Wu, N.; He, B.; Lu, Y.; Li, S.; et al. Amelioration of lipid abnormalities by α-lipoic acid through antioxidative and anti-inflammatory effects. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011, 19, 1647–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, E.H.; Lee, W.J.; Lee, S.A.; Kim, E.H.; Cho, E.H.; Jeong, E.J.; et al. Effects of α-lipoic acid on body weight in obese subjects. Am J. Med. 2011, 124, 85–88. [Google Scholar]

- Capece, U.; Moffa, S.; Improta, I.; Di Giuseppe, G.; Nista, E.C.; Cefalo, C.M.A.; et al. Alpha-lipoic acid and glucose metabolism: a comprehensive update on biochemical and therapeutic features. Nutrients 2023, 15, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haghighatdoost, F.; Gholami, A.; Hariri, M. Alpha-lipoic acid effect on leptin and adiponectin concentrations: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 76, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pershadsingh, H.A. Alpha-lipoic acid: physiologic mechanisms and indications for the treatment of metabolic syndrome. Expert. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2007, 16, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, Y.S. Effects of L-carnitine on obesity, diabetes, and as an ergogenic aid. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 17, 306–308. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Zhao, H. Role of carnitine in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and other related diseases: an update. Front Med. (Lausanne) 2021, 8, 689042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durazzo, A.; Lucarini, M.; Nazhand, A.; Bouto, S.B.; Silva, A.M.; et al. The nutraceutical value of carnitine and its use in dietary supplements. Molecules 2020, 25, 2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fathizadeh, H.; Milajerdi, A.; Reiner, Ž.; Amirani, E.; Asemi, Z.; Mansournia, M.A.; et al. The effects of L-carnitine supplementation on indicators of inflammation and oxidative stress: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2020, 19, 1879–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askarpour, M.; Hadi, A.; Miraghajani, M.; Symonds, M.E.; Sheikhi, A.; Ghaedi, E. Beneficial effects of l-carnitine supplementation for weight management in overweight and obese adults: An updated systemic review and dose-response meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 151, 104554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karalis, D.T.; Karalis, T.; Karalis, S.; Kleisiari, A.S. L-Carnitine as a Diet Supplement in Patients With Type II Diabetes. Cureus 2020, 12, e7982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zozina, V.I.; Covantev, S.; Goroshko, O.A.; Krasnykh, L.M.; Kukes, V.G. Coenzyme Q10 in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases: current state and the problem. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2018, 14, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantle, D.; Dybring, A. Bioavailability of coenzyme Q10: An overview of the absorption process and subsequent metabolism. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantle, D.; Heaton, R.A.; Hargreaves, I.P. Coenzyme Q10 and immune function: an overview. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rochette, L.; Zeller, M.; Cottin, Y.; Vergely, C. Diabetes, oxidative stress and thera- peutic strategies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2014, 1840, 2709–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, A.; Rahman, M. Mitochondrial dysfunction in obesity: potential benefit and mechanism of co-enzyme Q10 supplementation in metabolic syndrome. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2014, 13, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casagrande, D.; Waid, P.H. Jordão AAJr Mechanisms of action effects of the administration of Coenzyme Q10 on metabolic syndrome. J. Nutr. Intermed. Metab. 2018, 13, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Failla, M.L.; Chitchumroonchokchai, C.; Aoki, F. Increased bioavailability of ubiquinol compared to that of ubiquinone is due to more efficient micellarization during digestion and greater GSH-dependent uptake and basolateral secretion by Caco-2 cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 7174–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.; Bradford, J. Should I take coenzyme Q10 with a statin? JAAPA 2007, 19, 61–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifuentes-Franco, S.; Sánchez-Macías, D.C.; Carrilo-Ibarra, S.; Rivera-Valdés, J.J.; Zuñiga, L.Y.; Sánchez-López, V.A. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation on Infectious Diseases. Healthcare (Basel) 2022, 10, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vona, R.; Pallotta, L.; Cappelletti, M.; Severi, C.; Matarrese, P. The Impact of Oxidative Stress in Human Pathology: Focus on Gastrointestinal Disorders. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, M.P. Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation in Reducing Inflammation: An Umbrella Review. J. Chiropr. Med. 2022, 22, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantle, D.; Kozhevnikova, S.; Larsen, S. Coenzyme Q10 and Obesity: An Overview. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; El-Sehrawy, A.A.M.A.; Shankar, A.; Mohammed, J.S.; Hjazi, A.; et al. Effects of Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation on Metabolic Indicators in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Ther. 47, 235–243. [CrossRef]

- Gholami, M.; Khosrowbeygi, A. Review on the mechanisms of the effects of coenzyme Q10 supplementation on serum levels of leptin and adiponectin. Rom. J. Diabetes Nutr. Metab. Dis. 2023, 30, 124–131. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, X.; Dong, X.; Hu, Y.; Xu, F.; Hu, C.; Shu, C. Coenzyme Q10 Stimulate Reproductive Vatality. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2023, 17, 2623–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardekani, A.; Tabrizi, R.; Maleki, E.; Lankarani, K.B.; Heydari, S.T.; Moradinazar, M.; et al. Effects of coenzyme Q10 supplementation on lipid profiles and liver enzymes of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 2580–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, K.L.; Chen, L.H.; Chiou, S.H.; Chiou, G.Y.; Chen, Y.C.; Chou, H.Y.; et al. Conzyme Q10 suppresses oxLDL-induced endothelial oxidative injuries by the modulation of LOX-1-mediated ROS generation via the AMPK/PKC/NADPH oxidase signaling pathway. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2011, 55, S227–S240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukai, T.; Ushio-Kukai, M. Superoxide dismutase: role in redox signaling, vascular function, and diseases. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 15, 1583–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiningham, K.K.; XU, Y.; Daosukho, C.; Popova, B.; Clair, D.K.S. Nuclear factor κB-dependent mechanisms coordinate the synergistic effect of PMA and cytokines on the induction of superoxide dismutase 2. Biochem. J. 2001, 353, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tun, S.; Spainhower, C.J.; Cottrill, C.L.; Lakhani, H.V.; Pillai, S.S.; Dilip, A.; et al. Therapeutic Efficacy of Antioxidants in Ameliorating Obesity Phenotype and Associated Comorbidities. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuni, Y.; Cook, J. A.; Choudhuri, R.; Degraff, W.; Sowers, A. L.; Krishna, M.C.; et al. Inhibition of adipogenesis by Tempol in 3T3-L1 cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 49, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, R.; Gao, M.; Qu, S.; Liu, D. Overexpression of superoxide dismutase 3 gene blocks high-fat diet-induced obesity, fatty liver and insulin resistance. Gene Ther. 2014, 21, 840–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perriotte-Olson, C.; Adi, N.; Manickam, D.S.; Westwood, R.A.; Desouza, C.V.; Natarajan, G.; et al. Nanoformulated copper/zinc superoxide dismutase reduces adipose inflammation in obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2016, 24, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 156 Coudriet, G.M.; Delmastro-Greenwood, M.M.; Previte, D.M.; Marré, M.L.; O’Connor, E.C.; Novak, E.A.; et al. Treatment with a Catalytic Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) Mimetic Improves Liver Steatosis, Insulin Sensitivity, and Inflammation in Obesity-Induced Type 2 Diabetes. Antioxidants (Basel) 2017, 6, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Torres, I.; Gastrejón-Téllez, V.; Soto, M.E.; Rudio-Ruiz, M.E.; Manzano-Pech, L.; Guarner-Lans, V. Oxidative stress, plant natural antioxidants, and obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.M.; Heo, H.J. The roles of catechins in regulation of systemic inflammation. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 31, 957–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Zhou, S.; Wu, J.; Liu, L.; Song, Y.; Li, T.; et al. NRF2 plays a critical role in both self and EGCG protection against diabetic testicular damage. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2017, 2017, 3172692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Wu, D.; Tan, X.; Zhong, M.; Xing, J.; Li, W.; Li, D.; Cao, F. The role of catechins in regulating diabetes: an update review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiherer, A.; Mündlein, A.; Drexel, H. Phytochemicals and their impact on adipose tissue inflammation and diabetes. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2013, 58, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potenza, M.A.; Marasciulo, F.L.; Tarquinio, M.; Tiravanti, E.; Colantuono, G.; Federici, A.; et al. EGCG, a green tea polyphenol, improves endothelial function and insulin sensitivity, reduces blood pressure, and protects against myocardial I/R injury in SHR. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 292, 1378–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onakpoya, I.; Spencer, E.; Heneghan, C.; Tompson, M. The effect of green tea on blood pressure and lipid profile: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2014, 24, 823–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, P.; Choudhury, S.T.; Seidel, V.; Rahman, A.B.; Aziz, M.A.; Richi, A.E.; et al. Therapeutic potential of quercetin in the management of type-2 diabetes mellitus. Life (Basel) 2022, 12, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepika, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Maurya, P.K. Health Benefits of Quercetin in Age-Related Diseases. Molecules 2022, 27, 2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakyriakopoulou, P.; Veldakis, N.; Khattab, E.; Valsami, G.; Korakianitis, I.; Kadoglou, N.P.E. Potential pharmaceutical applications of quercetin in cardiovascular diseases. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomou, Ε.-Μ.; Papakyriakopoulou, P.; Saitani, E.-M.; Valsami, G.; Pippa, N.; Skaltsa, H. Recent Advances in Nanoformulations for Quercetin Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.K.; Kang, H.S. Anti-diabetic effect of cotreatment with quercetin and resveratrol in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Biomol. Ther. 2018, 26, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseini, A.; Razavi, B.M.; Banch, M.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Quercetin and metabolic syndrome: a review. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 5352–5364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Weng, X.; Bao, X.; Bai, X.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, S.; et al. A novel anti-atherosclerotic mechanism of quercetin: competitive binding to KEAP1 via Arg483 to inhibit macrophage pyroptosis. Redox Biol. 2022, 57, 102511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubczyk, K.; Kruzga, A.; Katarzyna, J.; Skonieczna-Zydecka, K. Antioxidant potential of curcumin – a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Andrea, G. Quercetin: a flavonol with multifaceted therapeutic applications? Fitoterapia 2015, 106, 256–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 173 Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; He, J.; Zhao, Y. Quercetin Regulates Lipid Metabolism and Fat Accumulation by Regulating Inflammatory Responses and Glycometabolism Pathways: A Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiano, F.; Giannotti, L.; Gnoni, G.V.; Siculella, L.; Gnoni, A. Quercetin inhibition of SREBPs and ChREBP expression results in reduced cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis in C6 glioma cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2019, 117, 105618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Li, Q.; Li, K.; Zhu, L.; Lin, X.; Lin, X.; et al. Quercetin improves glucose and lipid metabolism of diabetic rats: involvement of Akt signaling and SIRT1. J. Diabetes Res. 2017, 2017, 3417306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, H.M.; Nachar, A.; Thong, F.; Sweeney, G.; Haddad, P.S. The molecular basis of the antidiabetic action of quercetin in cultured skeletal muscle cells and hepatocytes. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2015, 11, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhanya, R.; Kartha, C.C. Quercetin improves oxidative stress-induced pancreatic beta cell alterations via MTOR-signaling. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2021, 476, 3879–3887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazloom, Z.; Abdollahzadeh, S.M.; Dabbaghmanesh, M.-H.; Rezaianzadeh, A. The effect of quercetin supplementation on oxidative stress, glycemic control, lipid profile and insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial. J. Heal. Sci. Surveill. Syst. 2014, 2, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ostadmohammadi, V.; Milajerdi, A.; Ayati, E.; Kolahdooz, F.; Asemi, Z. Effects of quercetin supplementation on glycemic control among patients with metabolic syndrome and related disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 1330–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, G.-J.; Li, Y.; Cao, Q.-H.; Wu, H.-X.; Tang, X.-Y.; Gao, X.-H.; et al. In vitro and in vivo evidence that quercetin protects against diabetes and its complications: A systematic review of the literature. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 109, 1085–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, G.-R.; Liu, S.; Yang, H.-W.; Chen, X.-L. Quercetin protects against diabetic retinopathy in rats by inducing heme oxygenase-1 expression. Neural Regen. Res. 2020, 16, 1344–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Chen, J.; Zheng, Q.; Chen, W.; Wang, Y.; Xu, X. Pioglitazone, Extract of Compound Danshen Dripping Pill, and Quercetin Ameliorate Diabetic Nephropathy in Diabetic Rats. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2013, 36, 422–427. [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa, N.H.; Siti, H.N.; Kamisah, Y. Role of Quercetin in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Plants 2025, 14, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahedi, M.; Ghiasvand, R.; Feizi, A.; Asgari, G.; Darvish, L. Does Quercetin Improve Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Inflammatory Biomarkers inWomen with Type 2 Diabetes: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 4, 777–785. [Google Scholar]

- Fatima, M.T.; Bhat, A.A.; Nisar, S.; Fakhro, K.A.; Akil, A.S.A.-S. The role of dietary antioxidants in type 2 diabetes and neurodegenerative disorders: An assessment of the benefit profile. Heliyon 2022, 9, e12698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Miao, X.; Yang, F.-J.; Cao, J.-F.; Liu, X.; Fu, J.-L.; Su, G.-F. Therapeutic potential of curcumin in diabetic retinopathy (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2021, 47, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Y.; Khan, H.; Alotaibi, G.; Khan, F.; Alam, W.; Aschner, M.; et al. How curcumin targets inflammatory mediators in diabetes: therapeutic insights and possible solutions. Molecules 2022, 27, 4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, B.B. Targeting inflammation-induced obesity and metabolic diseases by curcumin and other nutraceuticals Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2010, 30, 173–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahza, M.J.; Ghalandari, H.; Mohammad, H.G.; Amini, M.R.; Askarpour, M. Effects of curcumin/turmeric supplementation on lipid profile: A GRADE-assessed systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Complement Ther. Med. 2023, 75, 102955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lone, J.; Choi, J.H.; Kim, S.W.; Yun, J.W. Curcumin induces brown fat-like phenotype in 3T3-L1 and primary white adipocytes. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 27, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.L.; Li, Y.; Wen, Y.; Chen, Y.F.; Na, L.X.; Li, S.T.; et al. Curcumin, a potential inhibitor of up-regulation of TNF-alpha and IL-6 induced by palmitate in 3t3-L1 adipocytes through NF-kappaB and JNK pathway. BioMed Environ. Sci. 2009, 22, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivari, F.; Mingione, A.; Brasacchio, C.; Soldati, L. Curcumin and type 2 diabetes mellitus: prevention and treatment. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahi, Y.; Khalili, N.; Sahebi, E.; Namazi, S.; Karimian, M.S.; Majeed, M.; et al. Antioxidant effects of curcuminoids in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Inflammopharmacology 2017, 25, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marton, L.T.; Pescinini-E-Salzedas, L.M.; Camargo, M.E.C.; Barbalho, S.M.; Dos Santos Haber, J.F.; Sinatora, R.V.; et al. The effects of curcumin on diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 66948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koushki, M.; Amiri-Dashatan, N.; Ahmadi, N.; Abbaszadeh, H.-A.; Rezaei-Tavirani, M. Resveratrol: A miraculous natural compound for diseases treatment. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 6, 2473–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiniak, S.; Aebisher, D.; Bartusik-Aebisher, D. Health benefits of resveratrol administration. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2019, 66, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schugar, R.C.; Shih, D.M.; Warrier, M.; Helsley, R.N.; Burrows, A.; Ferguson, D.; et al. The TMAO-Producing Enzyme Flavin-Containing Monooxygenase 3 Regulates Obesity and the Beiging of White Adipose Tissue. Cell Rep. 2017, 19, 2451–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 198 Springer, M.; Moco, S. Resveratrol and Its Human Metabolites. Effects on Metabolic Health and Obesity. Nutrients 2019, 11, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suarez, V.J.; Beltran-Velasco, A.I.; Redondo-Florez, L.; Martin-Rodriguez, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Global Impacts of Western Diet and Its Effects on Metabolism and Health: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren Z-q Zgeng S-y Sun, Z.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yi, P.; et al. Resveratrol: Molecular Mechanisms, Health Benefits, and Potential Adverse Effects. MedComm. (2020) 2025, 6, e70252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, D.S.; Skolnick, A.H.; Kirtane, A.J.; Murphy, S.A.; Barron, H.V.; Giugliano, R.P.; et al. U-Shaped Relationship of Blood Glucose with Adverse Outcomes among Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2005, 46, 178–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhaleem, I.A.; Brakat, A.M.; Adayel, H.M.; Asla, M.M.; Rizk, M.A.; Aboalfetoh, A.Y. The Effects of Resveratrol on Glycemic Control and Cardiometabolic Parameters in Patients with T2DM: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Med. Clin. 2022, 158, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeraattalab-Motlagh, S.; Jayedi, A.; Shab-Bidar, S. The Effects of Resveratrol Supplementation in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome, and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 114, 1675–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leh, H.E.; Lee, L.K. Lycopene: A Potent Antioxidant for the Amelioration of Type II Diabetes Mellitus. Molecules 2022, 27, 2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, I.; Khare, N.; Rai, A. Carotenoids: Sources, Bioavailability and Their Role in Human Nutrition [Internet]. Physiology. IntechOpen 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Dobhal, A.; Kaur, R.; Rawat, M.; Bhati, D.; Wilson, I. Enhancing lycopene stability and extraction: Sustainable techniques and role of nanotechnology. J Food Compos Anal. 2025, 148, 108192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, K.K.D.; Araújo, G.R.; Martins, T.L.; Bandeira, A.C.B.; de Paula Costa, G.; Talvani, A.; et al. The antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of lycopene in mice lungs exposed to cigarette smoke. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2017, 48, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafras, M.; Sabaragamuwa, R.; Suwair, M. Role of dietary antioxidants in diabetes: An overview. Food Chemistry Advances 2024, 4, 100666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafail, T.; Ain, H.B.U.; Noreen, S.; Ikram, A.; Arshad, M.T.; Abdullahi, M.A. Nutritional Benefits of Lycopene and Beta-Carotene: A Comprehensive Overview. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024 12, 8715–8741. [CrossRef]

- Abir, M.H.; Mahamud, A.G.M.S.U.; Tonny, S.H.; Anu, M.S.; Hossain, K.H.S.; et al. Pharmacological potentials of lycopene against aging and aging-related disorders: A review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 5701–5735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaköy, Z.; Cadirci, E.; Dincer, B. A New Target in Inflammatory Diseases: Lycopene. Eurasian J. Med. 2022, 54, S23–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Ni, Y.; Nagata, N.; Zhuge, F.; Xu, L.; Nagashimada, M.; et al. Lycopene alleviates obesity-induced Inflammation and insulin resistance by regulating M1/M2 status of macrophages. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2019, 63, 1900602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.P.; Khare, P.; Zhu, J.; Kondepudi, K.K.; Singh, J.; Baboota, R.K.; et al. A novel cobiotic-based preventive approach against high-fat diet-induced adiposity, nonalcoholic fatty liver and gut derangement in mice. Int. J. Obes. 2016, 40, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenni, S.; Hammou, H.; Astier, J.; Bonnet, L.; Karkeni, E.; Couturier, C.; et al. Lycopene and tomato powder supplementation similarly inhibit high-fat diet induced obesity, inflammatory response, and associated metabolic disorders. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1601083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Suo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zou, Q.; Tan, X.; Yuan, T.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X. Lycopene supplementation attenuates western diet-induced body weight gain through increasing the expressions of thermogenic/mitochondrial functional genes and improving insulin resistance in the adipose tissue of obese mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2019, 69, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrahim, T.; Alonazi, M.A. Lycopene corrects metabolic syndrome and liver injury induced by high fat diet in obese rats through antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antifibrotic pathways. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 141, 111831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Ghorat, F.; Ul-Haq, I.; Ur-Rehman, H.; Aslam, F.; Heydari, M.; et al. Lycopene as a natural antioxidant used to prevent human health disorders. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, K.; Agrawal, B. Effect of long term supplementation of tomatoes (cooked) on levels of antioxidant enzymes, lipid peroxidation rate, lipid profile and glycated haemoglobin in Type 2 diabetes mellitus. W. Indian Med. J. 2006, 55, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shidfar, F.; Froghifar, N.; Vafa, M.; Rajab, A.; Hosseini, S.; Shidfar, S.; Gohari, M. The effects of tomato consumption on serum glucose, apolipoprotein B, apolipoprotein A-I, homocysteine and blood pressure in type 2 diabetic patients. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2011, 62, 289–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Bal, B.S.; Chopra, S.; Singh, S.; Malhotra, N. Ameliorative effect of lycopene on lipid peroxidation and certain antioxidant enzymes in diabetic patients. J. Diabetes Metab. 2012, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y. Beneficial effect of lycopene on anti-diabetic nephropathy through diminishing inflammatory response and oxidative stress. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 1150–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozmen, O.; Topsakal, S.; Haligur, M.; Aydogan, A.; Dincoglu, D. Effects of caffeine and lycopene in experimentally induced diabetes mellitus. Pancreas 2016, 45, 579–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Jiang, Z. Effects of lycopene on metabolism of glycolipid in type 2 diabetic rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 109, 2070–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Q.; Zhong, C.; Zhou, X.; Chen, R.; Xiong, T.; Hong, M.; et al. The association between intake of dietary lycopene and other carotenoids and gestational diabetes mellitus risk during mid-trimester: a cross-sectional study. Br. J. Nutr. 2019, 121, 1405–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).