1. Introduction

It is hard to think of anything more significant to the wellbeing of citizens and peace than economic growth. Sustained high growth rates may improve a country's overall standard of living and income. Physical capital formation has been heavily emphasized in neoclassical growth models like Solow's (1956). Rather than focusing just on macroeconomic factors, modern theories of economic development also include factors like innovation, technology, human capital, and institutions.

In the last 50 years, globalization, trade, and foreign direct investment have brought the world closer together at an unprecedented pace. As a result, the diffusion of technology has been made easier. As a proportion of global GDP, total world trade as a percentage of GDP increased from 26.54% in 1970 to 58.24% in 2019 (Our Data, Our World). However, the disparity in wealth between the developed and the poor is widening. In recent months, the number of people living in poverty has remained at a record high of almost 1.3 billion. A wide range of variation in development is experienced around the world.

This paper examines the relationship between digital remittances and political institutions and how institutions shape migration flows. This article builds on the literature on political economy, democratization, and international migration to theorize the political consequences of remittances; results show that remittance inflows alter citizens' preferences for redistribution and government spending.

Emigration and its derivative remittances impact the quality of institutions in the home country. While migrants lack the incentive to express their dismay, they voice their concerns once they leave their home country. Their contribution can strengthen democratic principles and norms. This paper investigates such a relationship and utilizes a dynamic panel analysis to measure the impact of emigration and remittances on institutions' quality as expressed by democracy and open market values. Openness to emigration and human capital has a positive impact on institutions. Additionally, there is an ambivalent relationship between brain drain (skilled migration) and institutions. The research also measures the marginal effect of skilled emigration on institutional quality.

The analysis adds to the discussion of how globalization affects political behavior in developing countries. Migration and remittances have been overlooked in studying the effects of globalization in developed countries (Pritchett, 2006; Kapur, 2010). The increase in income from remittances is distinct from the external sources of income such as government transfers, foreign aid, or natural resource revenue. Remittances are private and transnational transfers. The size of these remittances is mainly contingent on the economic fortunes of the migrant and the economic performance of the destination country. This paper aims to bring scholarly attention to the effects of migration and remittances on political life for households in developing countries.

Recent research has highlighted the significance of institutions for economic development (Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson, 2005; Rodrik, 2007). For instance, Rodrik et al. (2004) show that once institutions are controlled for, geographic measures have a weak direct impact on income, though they have a strong indirect influence through their bearing on the quality of institutions. This evaluation argues that an important and yet overlooked (in the growth literature) determinant of institutions is migration and its derivative remittances.

The first impact of migration on the home country’s institutions is that once people have exited their home countries, they can voice their feelings. Indeed, the remittances sent home can work to moderate economic and social pressure to reform. Once migrant workers are abroad, they can utilize lobbying to inspire or slow development efforts, challenging development assistance or promoting economic sanctions. For instance, the Cuban Americans showed how a diaspora can help maintain pressure on the US government to sustain an ongoing embargo on the Cuban government. While it is unclear whether this has intensified the radical or the moderate factions in Cuba, it seems the recent immigrants, who left Cuba more for economic than for political reasons, and the second generation of Cuban Americans, are more supportive of a dialogue with the Cuban government and a softening of economic sanctions; and indeed, the Obama administration was able in 2009 to relax restrictions on travel and remittances to Cuba.

The case of Croatia showed that the diaspora in the US supported separation from the former Yugoslavia and the transition to an open market economy. The pro-separation movement provided enormous financial support to Tudjman’s Croatian Democratic Union (CDU) party, and after the victory in the first post-communist elections in 1990, saw its effort rewarded by gaining 12 out of 120 seats in the national assembly for diaspora Croats. Since then, the Croatian diaspora in Europe and the US has remained very active, raising funds, organizing demonstrations, petitions, media campaigns, and other lobbying activities that proved valuable in obtaining official recognition of independence or in shaping European and American attitudes during the Yugoslavia war (Ragazzi 2009).

Migration is a self-selection process. This fact opens a second avenue for the impact of migration on institutions. Given that more educated individuals and the middle class in general have a higher level of political participation and contribute more to public policy debates, emigration is likely to harm the quality and development of domestic institutions as well as the process by which sound policies are developed and implemented. On the other hand, migration prospects influence individuals' decisions to invest more in education (e.g., Mountford, 1997; Beine, Docquier, and Rapoport, 2001) and to allocate talent between productive and unproductive activities (Mariani, 2007), thereby mitigating or reversing any negative impact on political institutions from brain drain.

Finally, migration exposes the motherland and culture to democratic principles and norms, whether directly through contact with returning immigrants and overseas families, or indirectly through broader flows. In addition to promoting trade and FDI inflows (Gould, 1994; Rauch and Trindade, 2002; Rauch and Casella, 2003; Iranzo and Peri, 2009), these networks have been found to promote technological transfers (Kerr, 2008; Agrawal et al., 2011). Fargues and Be, 2006; Spilimbergo, 2009 proved that only individuals who are educated in a democratic country can support their own democracy. While Spilimbergo's work does not specify the precise mechanisms by which such influence might manifest, he suggests several possibilities (such as access to foreign media, adoption of norms and values while abroad and subsequent diffusion at home, etc.) that can be generalized to other migration experiences.

Research on the political impacts of remittances has been growing in recent years. The literature can be summarized as a debate on whether remittances are a blessing or a curse for developing countries. The contrasting theories about remittances owe much of their development to Albert Hirschman's concepts of voice and exit (Hirschman, 1970, 1993). The optimistic point of view argues for the democratizing effects of remittances as they can enhance voice among citizens as the cost of political participation decreases. As a result, recipients will rely less on patronage and clientelism and instead make new local government demands. The pessimist's highlight that remittances will lead recipients to exit from the political arena, which will lead governments to behave more autocratically. Recipients would find little at stake in local politics and would prefer to disengage in politics.

This article interprets Hirschman's voice and the concept of withdrawal as engagement and disengagement, conceptualizing voice as one of the engagements with the government. Engagement with the government can range from voting, using public services, or demanding a more significant role for the government in the economy. The analysis considers the exit as a form of disengagement. Remittance recipients will exit through acts of political disengagement such as not voting or substituting government services with private alternatives in the market. The blessing and curse theories make assumptions as to how remittances will affect the political behavior of the recipients, hence remittances shape institutional quality.

2. Empirical Analysis

Most of the empirical analysis on the effects of migration on institutions employs cross section analysis, and there is a lack of time series and dynamic panel analysis. While some of the analyses are robust, they miss the appropriate baseline specification resulting from different political and cultural factors, which can provide relevant information about the quality of institutions. As Alesina et al. (2003) reported, many explanatory variables have been utilized as determinants of institutions, such as log GDP per capita, legal origin dummies, and religious variables. However, such variables are highly correlated, making all cross-country regressions very sensitive to econometric specifications. The issue that arises is that cross-correlation imposes a significant problem because the variables can be endogenous, specific to each country.

However, in a panel data analysis, it is possible to control for unobservable heterogeneity and therefore for all time-invariant variables affecting institutional quality. While this analysis uses an OLS model as a baseline to contrast with a random and fixed effect panel regression, the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) seems to be the most robust. The strength of a dynamic panel estimation is that it provides controls for unobserved variables that are country specific and whose omission can deliver bias results. The model employs the tested Arellano Bond (1991) technique for instrumental variables, which uses the first difference of explanatory variables, which are instrumented by their lagged values in levels. The instrumented technique might be troublesome if the variables are not informative; to address this, Bond et al. (2001) advocate using informative instruments in the model.

3. Data

The data set is a five-year panel constructed from global samples. The data representing democracy is collected from Freedom House data set polity IV. The Freedom House measures Political Right (PR) and Civil liberty (CL) as a proxy for democracy. The Freedom House Index ranges from 1 to 7, with the higher number signifying more freedom. A set of questions determines the final scores. Three subcategories are used for the political rights index: election procedures, political involvement, and government functioning. Freedom of speech and religion, freedom of association and organization, the rule of law and individual autonomy, and individual rights all come under the umbrella of civil freedoms. Each nation is given a score from 1 to 7 based on the total of its subcategory ratings.

4. Net Migration

Immigration's effects on the host country have received a lot of attention, however effects on the sending country have received less attention. According to the available evidence, emigration has a net beneficial impact on the sending nation. Emigration, for example, serves to reduce unemployment and raise the earnings of the remaining employees by reducing the labor pool in the sending nation. What's more, immigrants often send money back to their families, which improves their quality of life and boosts the economies of their home countries and trading partners. Although most immigrants are young adults and married, which can lead to devastating effects on their families back home. Several countries have pushed to restrict immigration because they feel it is detrimental to the economy. Net migration is also a part of a larger social process that is hard to precisely estimate. In the short run it provides exchange rate stability to many countries, pushing politicians to strongly favor it. However, there is no direct links between net migration and institutional quality. The migration data utilized by this paper was collected from the migration data portal, and net migration was collected from the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

5. Per Capita GDP

Per capita GDP can express how national wealth can impact the standard of living, but how it impacts the quality of institutions remains subjective. The study of national wealth extends back to at least 1776, when Adam Smith wrote his seminal work (Smith, 1776). Robert Solow (1956) made a seminal contribution by demonstrating that long-term economic development is restricted by the pace of technological advancement. Paul Romer (1986) suggested that knowledge may be an input in production with increasing returns to scale. The solution rests in how societies and markets are structured, and institutions are at the forefront of this. Douglas North describes institutions as "humanly created restrictions that affect human interaction." Under North's theory, institutional quality rises when executive authority is limited. Consequently, adequate, high-quality institutions are required to guarantee that challengers and incumbents enjoy equal legal protection. North argues that long-term economic success should be based on respect for individual rights, emphasizing the importance of investments in education, physical capital, and new technology.

The essential lesson is as straightforward as it is critical: investment is always a direct result of stable institutions. An investment is fueled by with the idea of reaping the benefits under certain circumstances. This could be the right to practice a profession for several years or operate a plant in which several physical investments have been made. Legal and political rights establish "inclusive institutions," institutions whose rights and protection cover everybody, regardless of position in society or origin. This contrasts with "extractive institutions," which exclusively function to extract resources from the people for the advantage of the governing class. Easterly (2013) considers excellent public services to be a necessary part of high-quality institutions; consider machines not functioning due to recurrent power outages caused by a lack of governmental investment in the upkeep of energy supply infrastructure. Data on per Capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was collected from the World Bank.

6. Remittances

Remittances may be instruments of insurance for the migrant’s family to hedge against capital market imperfections, unemployment, education, and investment, but it is a failure to miss the connection between remittances and institutions in the home country. The institutional framework can, in many cases, contradict the development process and can lead to ethical dilemmas such as promoting migration and remitting as a development instrument while disregarding the high cost and personal risks faced by migrants and their families. Failure to recognize the institutional environment may also result in the adoption of initiatives that are impractical, such as encouraging remittance beneficiaries to create microenterprises in stagnating local markets. Positively, focusing on the larger context helps to underscore the range of roles a development organization can play. These may include advocacy; improving working conditions and legal protection for migrants; easing migration restrictions; and facilitating access to formal financial institutions in receiving countries; as well as providing information, support, and a variety of services to migrants, potential migrants, and their families.

7. The Human Development Index

The Human Development Index (HDI) was created with the goal of drawing attention to the fact that when judging a nation's degree of development, people and the capabilities they possess should take priority over economic growth alone. The HDI may also be used to assess national policy choices, such as determining why two countries with the same GDP per capita have such disparities in human development. These disparities may lead to criticism of the government's policy objectives. The Human Development Index (HDI) is a synthesis of assessments of important human development qualities such as living a long and healthy life, having a high level of education, and having a comfortable standard of living.

The HDI measures the geometric mean of the normalized indices of all dimensions. The average number of years of schooling for those aged 25 and older, as well as the expected number of years of schooling for children who are currently of school age, are used to calculate the education dimension. Life expectancy at birth defines the health component. The gross national income per capita is the major indicator of choice for measuring the quality of life. The HDI uses the logarithm of income to show how the importance of money reduces as the gross national product (GNP) increases. The three HDI dimension indices' values are then combined into a composite index using geometric mean as the computation technique. The HDI oversimplifies what it means to be human, capturing just a percentage of its complexities. It makes no mention of inequality, poverty, human security, empowerment, or any of the other challenges that exist. The Human Development Index (HDI) offers a better proxy for some of the most pressing issues in human development, such as poverty, gender imbalance, and inequality, than other composite indexes.

This analysis uses UN portal data as a proxy for human capital, which refers to the knowledge and skills embodied via education, training, and experience. In terms of the creation of products and services, human capital is crucial. Human capital is comprised of several things, including knowledge, education, health, and working circumstances. It appears evident that, at a given level of technology, productivity will increase with an increase in human capital. When the level of technology is enhanced—that is, when the level of technology is improved by applying new ways of innovation—human capital grows as knowledge-based production ensues. Human capital may affect growth performance because it works as an input element in the production function (Mankiw, Romer, and Weil) (MRW, 1992). Human capital accumulation provides positive output because its members become more productive, and it contributes to endogenous growth (Lucas, 1988). In addition, the buildup of human capital stimulates higher innovation and increased R & D, which again contribute to endogenous development (Romer 1990). Human capital may also influence capital investment, creating a second-order impact on growth performance (Benhabib and Spiegel, 1994). Hence, human capital can be relevant at both the macroeconomic and microeconomic levels. The microeconomic evidence seems to vary significantly in favor of educational attainment as measured by the number of years spent in school. Recent estimates indicate that each extra year of education raises individuals' earnings by 6.5 percent. On a global scale, there are insufficient definitive investigations. Mankiw, Romer, and Weil (1992) and Barro et al. (1995) found a substantial positive relationship between cross-national variances in the initial endowment level and subsequent growth rate. Binhabib and Spiegel (1994) and Pritchett et al. (1996) found that education may have a signaling impact at the individual level, hence increasing productivity. These findings have stimulated research to analyze the function and influence of human capital. De la Fuente and Domenech (2000, 2001) developed new estimates that seek to account for vocational and technical training as well as the shift in the number of years connected with various levels of education, which seems to enhance the data set used by Barro-Lee, applying production growth by regressing human capital and labor force but, in this instance, evaluating human capital investment flow as opposed to human capital stock value. While the micro approach has leveraged the production function to explain market assessment at the macroeconomic level, the same method may be used to explain the appraisal of individual enterprises. The focus of market value research has been on technical knowledge and its effect on prospective performance; this is directly related to investments in education, training, and the development of skills that will be crucial for enhancing intangible assets.

8. Skilled Labor as a Percentage of the Total Population

The skill level of the local population is crucial. If migrants are predominantly unskilled and natives are predominantly skilled (as is increasingly the case in developed countries), there is no significant disagreement in the literature that native workers' wages and employment opportunities will increase due to the complementarity between natives and unskilled migrants and increased investment upon the arrival of migrants. The United Arab Emirates is an extreme example of natives and low-skilled migrants being "different" and complementary, with migrants constituting a very large portion of the population (in some cases, over 80 percent) and natives constituting a separate, Arabic-speaking, wealthy, and family-connected group that holds a limited number of strategic jobs. There is little direct competition between unskilled migrants and natives, and the latter greatly benefit from the former's cheaper services and the economic growth they bring. The primary point of disagreement is the influence on wages of low-skilled natives who compete with low-skilled immigrants and who, depending on definition, may account for a substantial fraction of the working population in Europe and the United States. Nonetheless, depending on their usage of these services, all local workers, whether skilled or unskilled, will benefit to varying degrees from the lower cost of non-traded services such as domestic help. The preceding discussion demonstrates that the theory that unskilled migration must lower the wages of unskilled natives is fundamentally based on two assumptions: that migrants and natives are substitutes; and that the investment and growth stimulus provided by increased migration is either too small or takes too long to have a significant impact on the wages of native unskilled workers. While the share of skilled labor may have a direct impact on economic outcomes in both the home and receiving nations, it is uncertain if it affects institutional characteristics in the home country.

Table 1.

List of Data for Institutional Regression Analysis.

Table 1.

List of Data for Institutional Regression Analysis.

| Variable |

Definition |

Source |

| Political Right |

The Political Rights index is based on a team of professional analysts and researchers analyzing nations using a ten-question checklist divided into three subcategories: Electoral Process (3 questions), Political Pluralism and Participation (4 questions), and Government Functioning (four questions) (3 questions). Each question is scored on a scale of 0 to 4, with 0 representing the fewest rights and 4 representing the greatest rights. The Political Rights Checklist may get a maximum of 40 points (or a total of up to 4 points for each of the 10 questions). There is also a discretionary political rights question that may deduct up to four points from a country's score. |

Freedom House |

| Civil Liberty |

The Civil Liberties index is based on a 15-question checklist divided into four subcategories: free expression and belief (4 questions), associational and organizational rights (3 questions), rule of law (4 questions), and personal autonomy and individual rights (4 questions) (4 questions). Each question is scored on a scale of 0 to 4, with 0 being the fewest freedoms and 4 representing the greatest liberties. The Civil Liberties checklist may get a maximum of 60 points (or a total of up to 4 points for each of the 15 questions). |

Freedom House |

| Remittances |

Workers' or migrant remittances occur when migrants return home a portion of their earnings in the form of cash or products to assist their family. They have grown quickly in recent years and are now the primary source of foreign revenue for many developing nations. |

World Bank |

| GDP per Capita |

GDP per capita sum of gross value added by all resident producers in the economy plus any product taxes (less subsidies) not included in the output, divided by mid-year population. |

World Bank |

| Skilled Labor as Percentage of the Total Population |

Percentage of the labor force ages 15 and older with intermediate or advanced education, as classified by the International Standard Classification of Education. |

United Nation Development Program |

| HD development Index |

The Human Development Index (HDI) is a summary evaluation of average achievement in important human development qualities such as living a long and healthy life, being informed, and having a decent quality of life. |

International Labor Organization |

9. Panel Analysis

The dynamic panel data approach is used in this research to explore the impact of remittance inflows on the quality of homeland institutions in high remittance-receiving developing nations between 2015 and 2020. The research draws on the literature on democracy and education (Acemoglu et al., 2005, Bobba and Coviello, 2007, Castello-Climent, 2008) and Spilimbergo's (2009) work on democracy and foreign education to examine the influence of remittances on institutional quality using dynamic-panel regressions. Remittances would serve as a surrogate for emigration in this research.

10. The Econometric Model

Institutions j;t = β0 Remittancesi;t5 + β1LGDPj; t5 + β 2Hi; t5 + β 3 Xi; t5 + ηj

+ αt + €I; T

where i is the country, t is the period. All independent variables are lagged five years.

The coefficients β reflects coefficient for remittances, log GDP and human capital.

The model controls for time fixed effects αt and country fixed effects ηj the strength of a panel data estimation is that it provides controls for unobserved variables that are country specific and whose omission can deliver a bias result in a cross-sectional model. The validity of moments condition is assessed by using the overidentifying constraints given by Sargan and Hansen and testing the null hypothesis that the error component is not second order or serially correlated. Furthermore, for all Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) instruments, the model uses the Hansen difference test to assess the validity of the extra moment conditions associated with the level equation.

The analysis starts from the most restricted FE and RE models. Comparing the test results between OLS and FE (fixed effect) estimates, as well as between OLS and RE (random effect) estimates allow for testing to determine if the country-pair specific heterogeneity is present or not. Breusch and Pagen Lagrangian multiplier test is used to test the RE estimate against that of OLS. The F-test is used to test the FE estimates against the one from OLS.

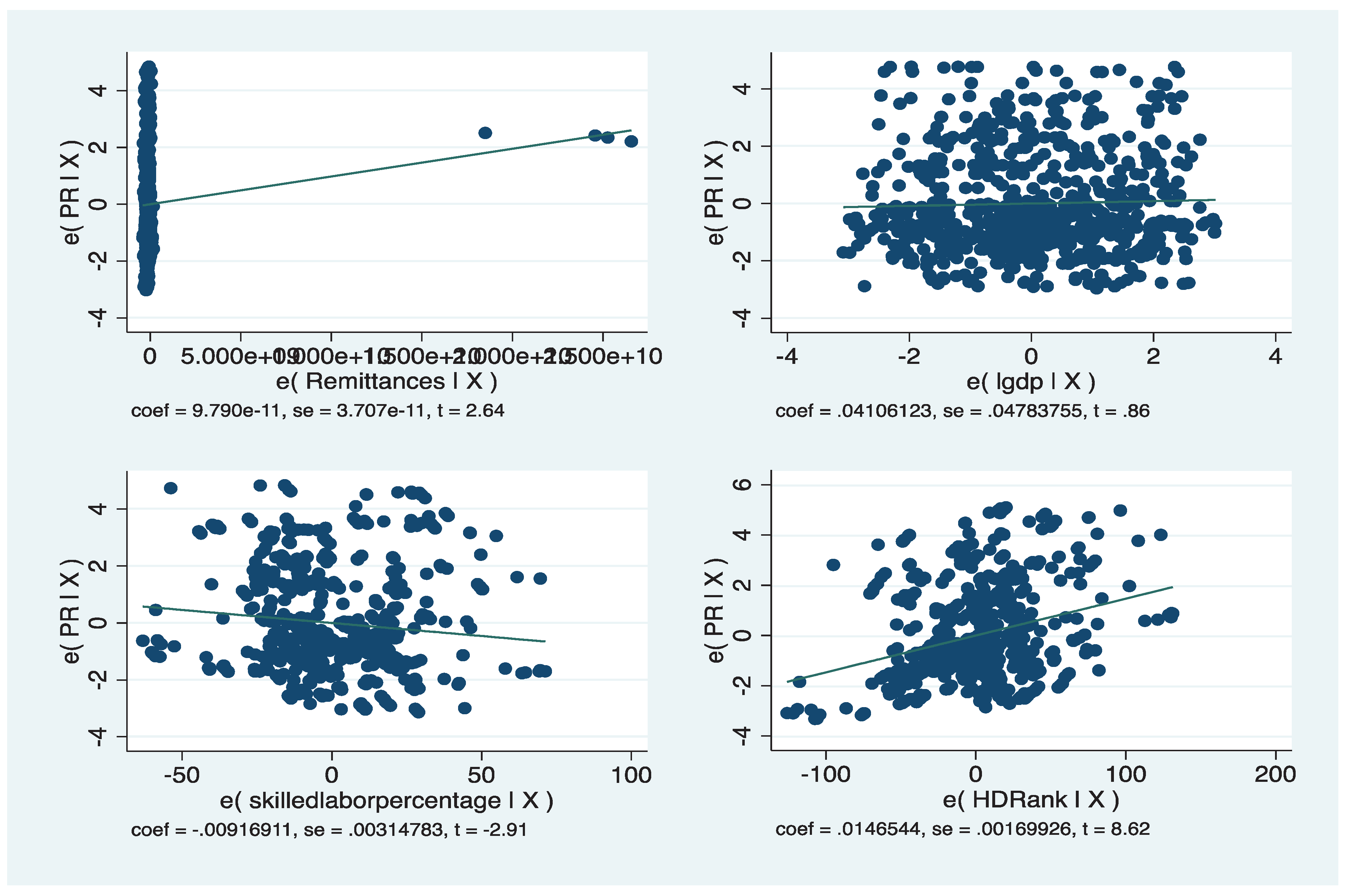

Figure 1.

Line Fitted Value for Regression Variables.

Figure 1.

Line Fitted Value for Regression Variables.

Table 2.

Regression Results for Political Right Model. Results for OLS. Fixed and Random Effect.

Table 2.

Regression Results for Political Right Model. Results for OLS. Fixed and Random Effect.

| |

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

| VARIABLES |

OLS |

Random Effect |

Fixed Effect |

| |

|

|

|

| Remittances |

9.790*** |

1.410*** |

1.610*** |

| |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

| Log GDP per Capita |

0.041 |

0.019 |

0.020 |

| |

(0.048) |

(0.033) |

(0.034) |

| Skilled Labor Percentage |

-0.009*** |

-0.009*** |

-0.009*** |

| |

(0.003) |

(0.003) |

(0.003) |

| HD Rank |

0.015*** |

0.014*** |

0.014*** |

| |

(0.002) |

(0.002) |

(0.002) |

| Constant |

2.012*** |

2.268*** |

2.263*** |

| |

(0.517) |

(0.428) |

(0.449) |

| |

|

|

|

| Observations |

720 |

720 |

720 |

| R-squared |

0.256 |

|

0.207 |

| Number of country id |

|

177 |

177 |

| Country Fe |

|

|

yes |

| Year Fee |

|

|

Yes |

Dependent variable is Political PR. ***, ** and * denote significance levels at 1%, 5% and 10% respectively. Robust standard errors are in parenthesis. For Models OLS, Random Effect, and Fixed Effect.

Table 3.

Regression Results for Political Right for GMM model.

Table 3.

Regression Results for Political Right for GMM model.

| |

(4) |

| VARIABLES |

GMM Model |

| |

|

| Remittances |

1.230*** |

| |

(0.000) |

| Log GDP Per Capita |

0.046 |

| |

(0.031) |

| Skilled Labor Percentage |

-0.010** |

| |

(0.005) |

| Human Capital |

0.016*** |

| |

(0.003) |

| Constant |

1.920*** |

| |

(0.542) |

| |

|

| Observations |

720 |

| Number of country id |

177 |

| ar1p |

0.162 |

| ar2p |

0.187 |

| Hansen p |

3.97e-07 |

| Sargan p |

0 |

Dependent variable is Political PR.*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1. Robust standard errors clustered by country in parentheses. One step system GMM estimator. The sample is an unbalanced sample comprising data at five-year interval between 2015 and 2020. AR(1) and AR(2) are the p-values of Arellano-Bond test for serial correlations. The values reported for the Hansen J test are the p-values for the null hypothesis of instrument validity. All the variables are treated as pre-determined. They are instrumented for using their own first to third lags in columns 3 and 6. They are instrumented for their own first differences to second lag. In addition to these instruments, the system GMM also uses as instruments for the level equations the explanatory variables in the first differences lagged one period.

Table 4.

Regression Results for Civil Liberty. Results for OLS. Fixed and Random Effect.

Table 4.

Regression Results for Civil Liberty. Results for OLS. Fixed and Random Effect.

| |

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

| VARIABLES |

OLS |

Random Effect |

Fixed Effect |

| |

|

|

|

| Remittances |

8.26*** |

1.03*** |

1.120*** |

| |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

| Log GDP per Capita |

0.001 |

0.003 |

0.007 |

| |

(0.040) |

(0.028) |

(0.029) |

| Skilled Labor Percentage |

-0.009*** |

-0.008*** |

-0.007*** |

| |

(0.003) |

(0.002) |

(0.003) |

| Human Capital |

0.014*** |

0.013*** |

0.013*** |

| |

(0.001) |

(0.001) |

(0.002) |

| Constant |

2.397*** |

2.372*** |

2.343*** |

| |

(0.432) |

(0.359) |

(0.377) |

| |

|

|

|

| Observations |

720 |

720 |

720 |

| R-squared |

0.314 |

|

0.223 |

| Number of country id |

|

177 |

177 |

| Country Fe |

|

|

yes |

| Year Fee |

|

|

Yes |

Table 5.

Regression Results for Civil Liberty GMM Model.

Table 5.

Regression Results for Civil Liberty GMM Model.

| |

(GMM) |

| VARIABLES |

CL |

| |

|

| Remittances |

9.360*** |

| |

(0.000) |

| Log GDP per Capita |

0.014 |

| |

(0.026) |

| Skilled Labor Percentage |

-0.009** |

| |

(0.004) |

| Human Capital |

0.014*** |

| |

(0.002) |

| Constant |

2.226*** |

| |

(0.474) |

| |

|

| Observations |

720 |

| Number of country id |

177 |

| ar1p |

0.885 |

| ar2p |

0.957 |

| Hansen p |

6.42e-06 |

| Sargan p |

0 |

Dependent variable is Civil Liberty

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1. Robust standard errors clustered by country in parentheses. One step system GMM estimator. The sample is an unbalanced sample comprising data at five-year interval between 2015 and 2020. AR(1) and AR(2) are the p-values of Arellano-Bond test for serial correlations. The values reported for the Hansen J test are the p-values for the null hypothesis of instrument validity. All the variables are treated as pre-determined. They are instrumented for using their own first to third lags in columns 3 and 6. They are instrumented for their own first differences to second lag. In addition to these instruments, the system GMM also uses as instruments for the level equations the explanatory variables in the first differences lagged one period.

11. Results and Conclusions

This article investigated the relationship between remittances and the quality of home-country institutions. The empirical results showed that remittances have a significant and positive marginal effect on the quality of homeland institutions. The dynamic panel model estimator, robust and unbiased, showed that a one percent increase in remittances enhances the quality of political institutions by 1.2 percentage points. Also, a one percent increase in remittances caused the civil liberty institutions to increase by 9.3 percent. Surprisingly, per capita income was not associated with increasing the quality of political rights or civil liberty. Moreover, skilled labor reported a significant but not positive relationship with the quality of home-country institutions. In contrast, this is a counter-intuitive result of the impact of income and skilled labor on institutions. Yet, it is consistent with the global observations that many countries were able to increase their education level, skilled labor, and income. However, they were unable to transfer such gains to the quality of their institutions. For instance, China, the Middle East, South America, and Eastern Europe suffer from this dichotomy. It was also clear from the regression results that human development had a positive and significant impact on the quality of home country institutions, but of a small magnitude. This implies that human development is an ongoing process that is incremental and accumulative. Remittances have a variety of effects on domestic institutions.

This section investigated the determinants before using dynamic-panel regressions to analyze the influence of remittances on institutions in the home country. The influx of remittances enhances institutional quality in the sending country. These results were consistent with both the OLS and panel regression models. It supported the hypothesis that there is also a positive and substantial influence on institutional quality when it comes to human capital. Furthermore, the study reveals that human capital has a positive influence on institutional quality (measured by the proportion of skilled workers in the workforce population). Because skilled labor simultaneously increases emigration and decreases average human capital, the issue arises as to whether certain nations might gain an institutional advantage via a brain drain as inflows of remittances return to the home country. The findings were favorably linked to remittances and human capital at home, showing that home nations do not suffer from brain drain if they have excellent institutions. According to the findings, the quality of institutions in the migrants’ home countries improved as a result of greater openness to migration (as shown by total remittances). Institutions permit “transmission" (Foucault 1982) which is represented in the migrant’s ability to enable diaspora engagement policies that are primarily centered on transnational communities, which are founded on a shared, state-centric national identity toward which policies may be directed (Gonzalez Gutierrez 1999). Remittances may help spread democratic principles and norms, even if the emigrants did not have the motivation to do so prior to leaving their home country.

Furthermore, success is dependent on the presence of comparable governmental structures inside the home-state system. The first criteria are difficult to achieve since diaspora networks comprise of various and diverse identities that resist uniformity. Symbolic new policies try to create a homogeneous national "diaspora" with strong devotion to the home-state. These efforts include a vast array of programs and activities with the objectives of boosting emigrants' feelings of belonging to a transnational community of co-nationals and raising the state's standing within this community. When seeking to interact with their various diasporas, nation-states typically make linguistic or symbolic gestures intended to reintegrate the diaspora into their national population. This begins the process of a discourse at the highest level that, on the one hand, glorifies immigrants as national heroes and bestows honors and praise upon them.

References

- Aggarwal, R.; Demirguc-Kunt, A.; Pería, M.S. M. Do remittances promote financial development? J. Dev. Econ. 2011, 96, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesina, A.; Devleeschauver, A.; Easterly, W.; Kurlat, S.; Wacziarg, R. Fractionalization. J. Econ. Growth 2003, 8, 155–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, R.J. Economic Growth in a Cross-Section of Nations. Q. J. Econ. 1991, 106, 407–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, Lucile; Mehdi Lahlou; Claire Escoffier; Pablo Pumares; and Paolo Ruspini (2002).

- Berriane, M.; Aderghal, M. The State of Research into International Migration from, to and through Morocco (Country Paper: Morocco). Prepared for the African Perspectives on Human Mobility program, financed by the MacArthur Foundation. 2008.

- Bhagwati, J. Borders Beyond Control. Foreign Aff. 2003, 82, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidwell, Robin. Morocco under Colonial Rule: French Administration of Tribal Areas 1912-1956. Cass: London, 1973.

- Conway, D.; Porter, R.; St Bernard, G. Diaspora Return of transnational Migrants to Trinidad and Tobago: The Additional Contributions of Social remittances. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2012, 34, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, Thad. Crude Democracy: Natural Resource Wealth and Political Regimes (Cambridge University Press: New York, 2008.

- Fargues, Philippe. Arab Migration to Europe: Trends and Policies. Int. Migr. Rev. 2004, 38, 1348–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fargues, Philippe, Jean-Pierre Cassarino, Abdelkader Latreche/ (2005) Mediterranean migration: an overview. In: Fargues 2005.

- Hirschman, A.O. Exit, voice, and the fate of the German Democratic Republic: An essay in conceptual history. World Politics 1993, 45, 173–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, Albert, O. Exit, voice, and loyalty: Responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states. Harvard University Press: 1970.

- ILO (2020). ILOSTAT database. Available online: https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/ (accessed on 21 July 2020).

- Lucas, R.E.B.; Stark, O. Motivations to remit: evidence from Botswana. J. Political Econ. 1985, 93, 901–918. [Google Scholar]

- North, D.C. Structure and Change in Economic History, W.W. Norton & Co, New York: 1981.

- Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y.; Smith, R.J. Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. J. Appl. Econom. 2001, 16, 289–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.; Shin, Y. An autoregressive distributed lag modelling approach to cointegration analysis. In S. Strom (Ed.), Econometrics and Economic Theory in the 20th Century: The Ragnar Frisch Centennial Symposium (chapter 11). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 1999.

- Ragazzi, F. The invention of the Croatian Diaspora: Unpacking the politics of Diaspora during the war in Yugoslavia, Center for Global Studies, George Mason University: 2009.

- Ragazzi, F. 'Diaspora' as a State Category: The Case of Croatia. In States and Emigrants, Trinity Term Seminar Series. Centre on Migration, Policy and Society, University of Oxford: 2006.

- Romer, P.M. Increasing Returns and Long-Run Growth. J. Political Econ. 1986, 94, 1002–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenau, J. Along the domestic-foreign frontier: Exploring governance in a turbulent world. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 1997.

- Smith, A. (1776), The Wealth of Nations: Books I – III, Penguin Classics, London, 1999.

- Solow, R.M. A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth. Q. J. Econ. 1956, 70, 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).