Submitted:

31 October 2025

Posted:

31 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

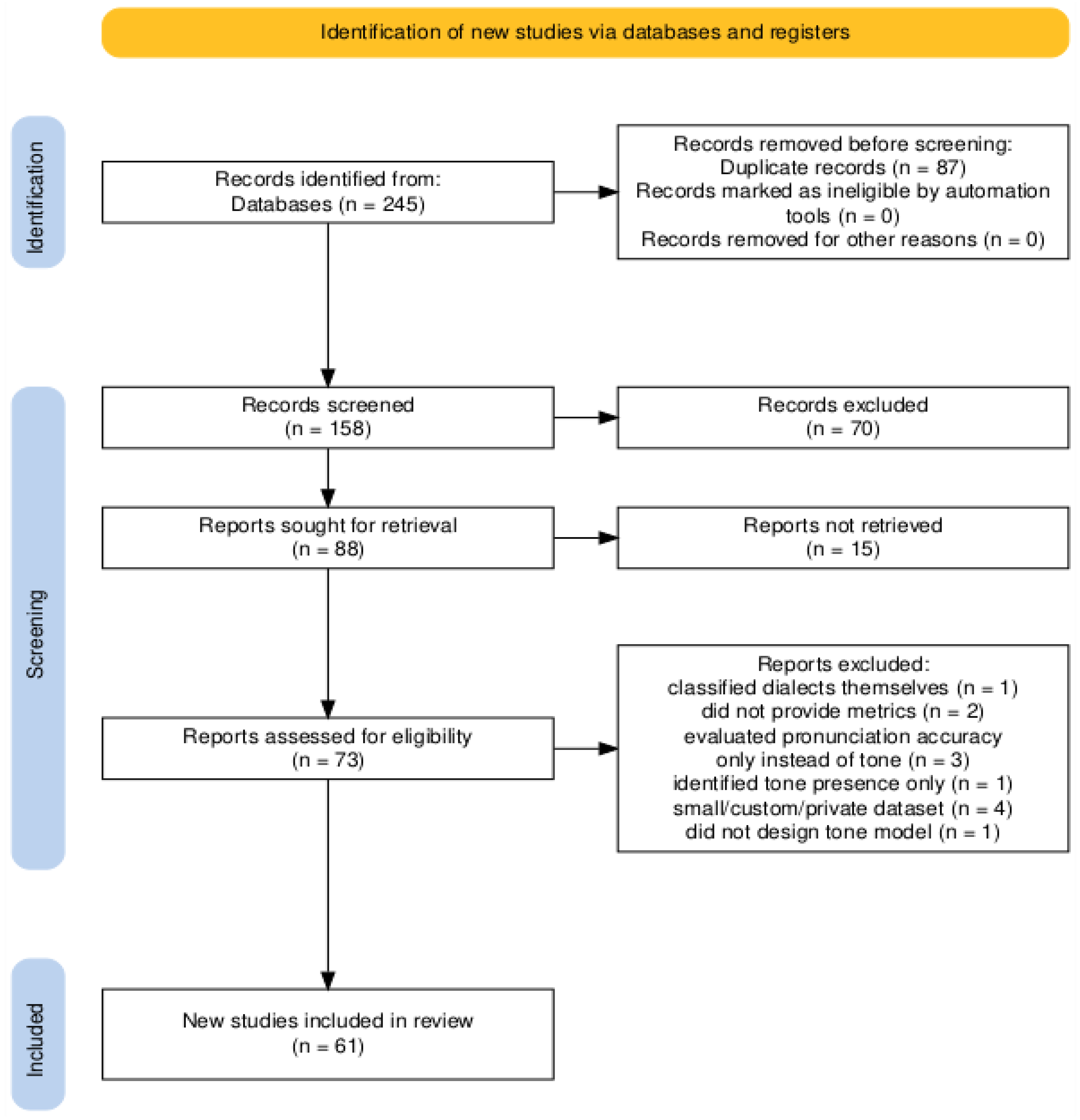

Purpose: Machine learning (ML) is increasingly applied in natural language processing, speech evaluation, and computer-assisted language learning (CALL). This systematic review synthesizes ML approaches to Mandarin tone recognition to assess best-performing models and discuss challenges and opportunities for translational and clinical applications. Method: Following PRISMA guidelines, we searched five databases (IEEE Xplore, PubMed, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus) and analyzed 61 articles for model architecture, input features, datasets, evaluation, and validation metrics. Results: Deep learning models outperform traditional approaches in Mandarin tone classification (mean accuracy 88.8% vs. 83.1%). Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) achieve up to 99.16% accuracy for isolated syllables, while Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) and attention-based models improve continuous speech recognition by capturing temporal dependencies with 7.03% error rate. Performance is affected by Tone 3 variability, neutral tones, and challenging conditions like background noise and disordered speech. Emerging areas of application include CALL and brain-computer interfaces with growing emphasis on robustness and inclusivity. Conclusion: While deep learning models represents the state of the art, several gaps limit practical deployment, including the lack of diverse datasets, weak prosody and dialect modeling, and insufficient validation rigor. Multimodal special-purpose corpora are needed to develop efficient lightweight models to improve real-time assessment and feedback for user-centered applications with strong pedagogical and clinical impact.

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Search Strategy

- a)

- The study must focus on applying or improving machine learning techniques for Mandarin tone classification, including work on accented Mandarin due to dialect influence, L2 learner accents, dialectal tone identification to support Mandarin recognition, or clinical applications. The training and test materials could be mono-syllabic, multi-syllabic, or continuous speech.

- b)

- The study must be published in peer-reviewed journals or conference proceedings. Reviews were not included.

- c)

- The study must report empirical results or datasets and provide performance or evaluation metrics to allow for comparative analysis.

- d)

- The study must use a sufficiently large dataset appropriate for the classification task or otherwise provide justification.

- e)

- The article must be written in English, publicly accessible, and published before March 2025.

Quality Assessment

Data Extraction

Results

Overview of Model Distribution

Model Performance and Characteristics

Types of Input Features

Model Validation and Performance Metrics

Training and Testing Datasets

Discussion

Handling Isolated Words vs. Connected Speech

Cross-Validation Strategies

Main Challenges and Opportunities

Practical Recommendations for Model Development and Deployment

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cao, M., Pavlik, P. I., & Bidelman, G. M. (2024). Enhancing lexical tone learning for second language speakers: Effects of acoustic properties in Mandarin tone perception. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1403816. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y., Deng, Y., Zhang, H., Huang, T., & Xu, B. (2000). Decision tree based Mandarin tone model and its application to speech recognition. 2000 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing. Proceedings (Cat. No.00ch37100), 3, 1759–1762 vol.3. [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.-S., Lee, C.-Y., Wang, X., Young, S.-T., Li, C.-H., & Chu, W.-C. (2023). Emotional tones of voice affect the acoustics and perception of Mandarin tones. PLOS One, 18(4), e0283635. [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.-C., Sun, S.-W., & Chen, S.-H. (1990). Mandarin tone recognition by multi-layer perceptron. International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, 517–520 vol.1. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C., Bunescu, R., Xu, L., & Liu, C. (2016a). Mandarin tone recognition based on unsupervised feature learning from spectrograms. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 140(4_Supplement), 3394–3394. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C., Bunescu, R., Xu, L., & Liu, C. (2016b). Tone classification in Mandarin Chinese using convolutional neural networks. Interspeech 2016, 2150–2154. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M., Yang, Z., & Liu, W. (2014). Deep neural networks for Mandarin tone recognition. 2014 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), 1154–1158. [CrossRef]

- Chen, N. F., Tong, R., Wee, D., Lee, P., Ma, B., & Li, H. (2015). iCALL corpus: Mandarin Chinese spoken by non-native speakers of european descent. Interspeech 2015, 324–328. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., Li, B., He, Y., Chen, S., Yang, Y., & Zhou, F. (2022). The effects of perceptual training on speech production of Mandarin sandhi tones by tonal and non-tonal speakers. Speech Communication, 139, 10–21. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-H., & Wang, Y.-R. (1995). Tone recognition of continuous Mandarin speech based on neural networks. IEEE Transactions on Speech and Audio Processing, 3(2), 146–150. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., & Sidtis, D. (2024). Contrastive stress in persons with parkinson’s disease who speak Mandarin: Task effect in production and preserved perception. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 69, 101173. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., & Xu, Y. (2021). Parallel recognition of Mandarin tones and focus from continuous F0. 1st International Conference on Tone and Intonation (TAI), 171–175. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B., Liao, K., Xiang, Y., Zou, Y., Zhang, X., & Zhang, Y. (2025). Development and validation of an AI-enhanced multimodal training program: Evidence from non-native Mandarin tone learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 0(0), 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J., Yi, K., & Li, B. (2000). Mandarin tone recognition based on wavelet transform and hidden markov modeling. Journal of Electronics (China), 17(1), 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.-W., & Lee, L. (2008). Improved large vocabulary Mandarin speech recognition by selectively using tone information with a two-stage prosodic model. Interspeech 2008, 1137–1140. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M., Cheng, X., & Zhao, L. (2003). HMM based recognition of Chinese tones in continuous speech. International Conference on Neural Networks and Signal Processing, 2003. Proceedings of the 2003, 2, 916-919 Vol.2. [CrossRef]

- Ding, H., Zhang, J., Zhang, H., Chen, F., & Zhang, Y. (2025). Multimodal training using pitch gestures improves Mandarin tone recognition in noise for children with cochlear implants. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 158(4), 2995–3005. [CrossRef]

- Ding, H., & Zhang, Y. (2023). Speech prosody in mental disorders. Annual Review of Linguistics, 9, 335–355. [CrossRef]

- Duanmu, S. (2007). The phonology of standard Chinese. Oxford University PressOxford. [CrossRef]

- Farran, B. M., & Morett, L. M. (2024). Multimodal cues in L2 lexical tone acquisition: Current research and future directions. Frontiers in Education, 9, 1410795. [CrossRef]

- Feng, G., Gan, Z., Llanos, F., Meng, D., Wang, S., Wong, P. C. M., & Chandrasekaran, B. (2021). A distributed dynamic brain network mediates linguistic tone representation and categorization. NeuroImage, 224, 117410. [CrossRef]

- Fon, J., & Chuang, Y.-Y. (2024). When a rise is not only a rise: An acoustic analysis of the impressionistic distinction between northern and central taiwan Mandarin using tone 1 as an example. Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 54(2), 738–769. [CrossRef]

- Gandour, J., Petty, S. H., & Dardarananda, R. (1988). Perception and production of tone in aphasia. Brain and Language, 35(2), 201–240. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q., Sun, S., & Yang, Y. (2019). ToneNet: A CNN model of tone classification of Mandarin Chinese. Interspeech 2019, 3367–3371. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y., Zhang, X., Xu, Y., Zhang, J., & Birkholz, P. (2020). An investigation of the target approximation model for tone modeling and recognition in continuous Mandarin speech. Interspeech 2020, 1913–1917. [CrossRef]

- Garg, S., Hamarneh, G., Jongman, A., Sereno, J. A., & Wang, Y. (2019). Computer-vision analysis reveals facial movements made during Mandarin tone production align with pitch trajectories. Speech Communication, 113, 47–62. [CrossRef]

- Garg, S., Hamarneh, G., Jongman, A., Sereno, J., & Wang, Y. (2018). Joint gender-, tone-, vowel- classification via novel hierarchical classification for annotation of monosyllabic Mandarin word tokens. 2018 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 5744–5748. [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N. R., Page, M. J., Pritchard, C. C., & McGuinness, L. A. (2022). PRISMA2020: An R package and shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and open synthesis. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 18(2), e1230. [CrossRef]

- Hirose, K., & Zhang, J. (1999). Tone recognition of Chinese continuous speech using tone critical segments. 6th European Conference on Speech Communication and Technology, 879–882. [CrossRef]

- Hong, T., Wang, J., Zhang, L., Zhang, Y., Shu, H., & Li, P. (2019). Age-sensitive associations of segmental and suprasegmental perception with sentence-level language skills in Mandarin-speaking children with cochlear implants. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 93, 103453. [CrossRef]

- Hu, H., Zahorian, S. A., Guzewich, P., & Wu, J. (2014). Acoustic features for robust classification of Mandarin tones. Interspeech 2014, 1352–1356. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X., Lu, X., & Hori, C. (2014). Mandarin speech recognition using convolution neural network with augmented tone features. The 9th International Symposium on Chinese Spoken Language Processing, 15–18. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X., Saiko, M., & Hori, C. (2014). Incorporating tone features to convolutional neural network to improve Mandarin/thai speech recognition. Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference (APSIPA), 2014 Asia-Pacific, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Huang, C., Zhang, F., Soong, F. K., & Chu, M. (2008). Mispronunciation detection for Mandarin Chinese. Interspeech 2008, 2655–2658. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. C.-H., & Seide, F. (2000). Pitch tracking and tone features for Mandarin speech recognition. 2000 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing. Proceedings (Cat. No.00ch37100), 3, 1523–1526 vol.3. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H., Wang, K., Hu, Y., & Li, S. (2021). Encoder-decoder based pitch tracking and joint model training for Mandarin tone classification. ICASSP 2021 - 2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 6943–6947. [CrossRef]

- Hussein, H., Mixdorff, H., & Hoffmann, R. (2012). Real-time tone recognition in a computer-assisted language learning system for german learners of Mandarin. In R. Mamidi & K. Prahallad (Eds.), Proceedings of the Workshop on Speech and Language Processing Tools in Education (pp. 37–42). The COLING 2012 Organizing Committee. https://aclanthology.org/W12-5805/.

- Johnson, M., Lapkin, S., Long, V., Sanchez, P., Suominen, H., Basilakis, J., & Dawson, L. (2014). A systematic review of speech recognition technology in health care. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 14(1), 94. [CrossRef]

- Koser, N., Oakden, C., & Jardine, A. (2018). Tone association and output locality in non-linear structures. Proceedings of the Annual Meetings on Phonology. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-Y., Tao, L., & Bond, Z. S. (2010). Identification of multi-speaker Mandarin tones in noise by native and non-native listeners. Speech Communication, 52(11), 900–910. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-C., Yeh, S.-C., Chang, J.-W., & Chen, Z.-Y. (2022). Research on Chinese speech emotion recognition based on deep neural network and acoustic features. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland), 22(13), 4744. [CrossRef]

- Lei, X., Hwang, M.-Y., & Ostendorf, M. (2005). Incorporating tone-related MLP posteriors in the feature representation for Mandarin ASR. Interspeech 2005, 2981–2984. [CrossRef]

- Lei, X., & Ostendorf, M. (2007). Word-level tone modeling for Mandarin speech recognition. 2007 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing - ICASSP ’07, 4, IV-665-IV–668. [CrossRef]

- Leung, K. K. W., Lu, Y.-A., & Wang, Y. (2025). Examining speech perception–production relationships through tone perception and production learning among indonesian learners of Mandarin. Brain Sciences, 15(7), 671. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., Mai, Q., Wang, M., & Ma, M. (2024). Chinese dialect speech recognition: A comprehensive survey. Artificial Intelligence Review, 57(2), 25. [CrossRef]

- Li, W., Chen, N. F., Siniscalchi, S. M., & Lee, C.-H. (2018). Improving Mandarin tone mispronunciation detection for non-native learners with soft-target tone labels and BLSTM-based deep models. 2018 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 6249–6253. [CrossRef]

- Li, W., Siniscalchi, S. M., Chen, N. F., & Lee, C.-H. (2016). Using tone-based extended recognition network to detect non-native Mandarin tone mispronunciations. 2016 Asia-Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference (APSIPA), 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.-H., Chiang, C.-Y., & Liu, T.-H. (2023). Tone labeling by deep learning-based tone recognizer for Mandarin speech. 2023 Asia Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference (APSIPA ASC), 873–880. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J., Li, W., Gao, Y., Xie, Y., Chen, N. F., Siniscalchi, S. M., Zhang, J., & Lee, C.-H. (2018). Improving Mandarin tone recognition based on DNN by combining acoustic and articulatory features using extended recognition networks. Journal of Signal Processing Systems, 90(7), 1077–1087. [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.-Y. (2004). Tone variation modeling for fluent Mandarin tone recognition based on clustering. 2004 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, 1, I–933. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-T., & Lai, Y.-H. (2024). Phonological processing in Chinese word repetition: Dementia effect and age effect. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 38(10), 970–986. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., & Tao, J. (2013). Mandarin tone recognition considering context information. 2013 IEEE International Conference on Signal Processing, Communication and Computing (ICSPCC 2013), 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., He, X., Mo, F., & Yu, T. (1999). Study on tone classification of Chinese continuous speech in speech recognition system. 6th European Conference on Speech Communication and Technology, 891–894. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., & Yu, T. (2000). New tone recognition methods for Chinese continuous speech. 6th International Conference on Spoken Language Processing (ICSLP 2000), vols. 1, 377-380–0. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., & Chen, Y. (2020). The roles of segment and tone in Bi-dialectal auditory word recognition. Speech Prosody 2020, 640–644. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q., Wang, J., Wang, M., Jiang, P., Yang, X., & Xu, J. (2013). A pitch smoothing method for Mandarin tone recognition. International Journal of Signal Processing, Image Processing and Pattern Recognition, 6(4), 245–254.

- Liu, S., & Samuel, A. G. (2004). Perception of Mandarin lexical tones when F0 information is neutralized. Language and Speech, 47(Pt 2), 109–138. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Shao, J., Zhang, P., Zhao, Q., Yan, Y., & Feng, J. (2007). Real context model for tone recognition in Mandarin conversational telephone speech. Third International Conference on Natural Computation (ICNC 2007), 2, 696–699. [CrossRef]

- Luo, X., & Fu, Q.-J. (2004). Enhancing Chinese tone recognition by manipulating amplitude envelope: Implications for cochlear implants. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 116(6), 3659–3667. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q., Zheng, N., & Li, X. (2016). Mandarin speech-in-noise and tone recognition using vocoder simulations of the temporal limits encoder for cochlear implants. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 139(1), 301–310. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q., Zheng, N., & Li, X. (2017). Loudness contour can influence Mandarin tone recognition: Vocoder simulation and cochlear implants. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, 25(6), 641–649. [CrossRef]

- Mou, Z., Ye, W., Chang, C.-C., & Mao, Y. (2020). The application analysis of neural network techniques on lexical tone rehabilitation of Mandarin-speaking patients with post-stroke dysarthria. IEEE Access, 8, 90709–90717. [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, n71. [CrossRef]

- Pelzl, E., Lau, E. F., Guo, T., & DeKeyser, R. (2021). Even in the best-case scenario l2 learners have persistent difficulty perceiving and utilizing tones in Mandarin: Findings from behavioral and event-related potentials experiments. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 43(2), 268–296. [CrossRef]

- Peng, L., Dai, W., Ke, D., & Zhang, J. (2021). Multi-scale model for Mandarin tone recognition. 2021 12th International Symposium on Chinese Spoken Language Processing (ISCSLP), 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Ryant, N., Yuan, J., & Liberman, M. (2014). Mandarin tone classification without pitch tracking. 2014 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 4868–4872. [CrossRef]

- Schenck, K., & Beguš, G. (2025). Unsupervised learning and representation of Mandarin tonal categories by a generative CNN (No. arXiv:2509.17859). arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Shen, G., Watkins, M., Alishahi, A., Bisazza, A., & Chrupała, G. (2024). Encoding of lexical tone in self-supervised models of spoken language. Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers), 4250–4261. [CrossRef]

- Shour, A. R., Anguzu, R., & Onitilo, A. A. (2025). Speech recognition technology and documentation efficiency. JAMA Network Open, 8(3), e251526. [CrossRef]

- Song, W., & Deng, I. (2025). A hybrid architecture combining CNN, LSTM, and attention mechanisms for automatic speech recognition. 2025 11th International Conference on Computing and Artificial Intelligence (ICCAI), 285–292. [CrossRef]

- Su, W., & Miao, Z. (2006). Speech and tone recognition for a Mandarin e-learning system. TENCON 2006 - 2006 IEEE Region 10 Conference, 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Surendran, D., Levow, G.-A., & Xu, Y. (2005). Tone recognition in Mandarin using focus. Interspeech 2005, 3301–3304. [CrossRef]

- Tang, J., & Li, M. (2021). End-to-end Mandarin tone classification with short term context information. 2021 Asia-Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference (APSIPA ASC), 878–883. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9689521.

- Tang, L., & Yin, J. (2006). Mandarin tone recognition based on pre-classification. 2006 6th World Congress on Intelligent Control and Automation, 2, 9468–9472. [CrossRef]

- Tang, P., Xu Rattanasone, N., Yuen, I., & Demuth, K. (2017). Acoustic realization of Mandarin neutral tone and tone sandhi in infant-directed speech and lombard speech. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 142(5), 2823–2835. [CrossRef]

- Tong, R., Chen, N. F., Ma, B., & Li, H. (2015). Goodness of tone (GOT) for non-native Mandarin tone recognition. Interspeech 2015, 801–805. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., & Seneff, S. (1998). A study of tones and tempo in continuous Mandarin digit strings and their application in telephone quality speech recognition. 5th International Conference on Spoken Language Processing (ICSLP 1998), paper 535-0. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Shu, H., Zhang, L., Liu, Z., & Zhang, Y. (2013). The roles of fundamental frequency contours and sentence context in Mandarin Chinese speech intelligibility. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 134(1), EL91–EL97. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Tang, Z., Zhao, Y., & Ji, S. (2009). Tone recognition of continuous Mandarin speech based on binary-class SVMs. 2009 First International Conference on Information Science and Engineering, 710–713. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Li, M., Li, H., Pun, S. H., & Chen, F. (2023). Cross-subject classification of spoken Mandarin vowels and tones with EEG signals: A study of end-to-end CNN with fine-tuning. 2023 Asia Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference (APSIPA ASC), 535–539. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., & Xu, L. (2020). Mandarin tone perception in multiple-talker babbles and speech-shaped noise. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 147(4), EL307–EL313. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-D., Hirose, K., Zhang, J.-S., & Minematsu, N. (2008). Tone recognition of continuous Mandarin speech based on tone nucleus model and neural network. IEICE Transactions on Information and Systems, E91.D(6), 1748–1755. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. R., & Chen, S. H. (1994). Tone recognition of continuous Mandarin speech assisted with prosodic information. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 96(5 Pt 1), 2637–2645. [CrossRef]

- Wei, S., Wang, H.-K., Liu, Q.-S., & Wang, R.-H. (2007). CDF-matching for automatic tone error detection in Mandarin CALL system. 2007 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing - ICASSP ’07, 4, IV-205-IV–208. [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.-F., & Siu, M.-H. (2002). Integration of tone related feature for Chinese speech recognition. 6th International Conference on Signal Processing, 2002., 1, 476–479 vol.1. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J., Zahorian, S. A., & Hu, H. (2013). Tone recognition for continuous accented Mandarin Chinese. 2013 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, 7180–7183. [CrossRef]

- Xi, J., Xu, H., Zhu, Y., Zhang, L., Shu, H., & Zhang, Y. (2021). Categorical perception of Chinese lexical tones by late second language learners with high proficiency: Behavioral and electrophysiological measures. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 64(12), 4695–4704. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C., & Liu, J. (2024). The perception of emotional prosody in Mandarin Chinese words and sentences. Second Language Research, 2676583241286748. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L., Chen, X., Zhou, N., Li, Y., Zhao, X., & Han, D. (2007). Recognition of lexical tone production of children with an artificial neural network. Acta Oto-Laryngologica, 127(4), 365–369. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y. (2019). Prosody, tone, and intonation. In W. F. Katz & P. F. Assmann (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Phonetics (pp. 314–356). Routledge.

- Yan, J., Meng, Q., Tian, L., Wang, X., Liu, J., Li, M., Zeng, M., & Xu, H. (2023). A Mandarin tone recognition algorithm based on random forest and feature fusion. Mathematics, 11(8), 1879. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L., Xie, Y., & Zhang, J. (2018a). Applying deep bidirectional long short-term memory to Mandarin tone recognition. 2018 14th IEEE International Conference on Signal Processing (ICSP), 1124–1127. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L., Xie, Y., & Zhang, J. (2018b). Improving Mandarin tone recognition using convolutional bidirectional long short-term memory with attention. Interspeech 2018, 352–356. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.-J., Lee, J.-C., Chang, Y.-C., & Wang, H.-C. (1988). Hidden markov model for Mandarin lexical tone recognition. IEEE Transactions on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, 36(7), 988–992. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Liu, X., & Shao, Y. (2022). Chinese dialect tone’s recognition using gated spiking neural P systems. Journal of Membrane Computing, 4(4), 284–292. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Ma, W., Ding, H., Peng, G., & Zhang, Y. (2022). Phonological awareness and working memory in Mandarin-speaking preschool-aged children with cochlear implants. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 65(11), 4485–4497. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Ma, W., Ding, H., & Zhang, Y. (2023). Sustainable benefits of high variability phonetic training in Mandarin-speaking kindergarteners with cochlear implants: Evidence from categorical perception of lexical tones. Ear and Hearing, 44(5), 990–1006. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Shao, Y., Yu, X., & Jin, Y. (2021). The method based on spectrogram’s image classification for Chinese dialect’s tone recognition. 2021 IEEE 4th International Conference on Computer and Communication Engineering Technology (CCET), 75–78. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. (2010). Issues in the analysis of Chinese tone. Language and Linguistics Compass, 4(12), 1137–1153. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., & Hirose, K. (2004). Tone nucleus modeling for Chinese lexical tone recognition. Speech Communication, 42(3), 447–466. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., & Liu, J. (2011). Tone sandhi and tonal coarticulation in tianjin Chinese. Phonetica, 68(3), 161–191. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-S., & Hirose, K. (2000). Anchoring hypothesis and its application to tone recognition of Chinese continuous speech. 2000 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing. Proceedings (Cat. No.00ch37100), 3, 1419–1422 vol.3. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-S., & Kawanami, H. (1999). Modeling carryover and anticipation effects for Chinese tone recognition. 6th European Conference on Speech Communication and Technology, 747–750. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M., Tang, E., Ding, H., & Zhang, Y. (2024). Artificial intelligence and the future of communication sciences and disorders: A bibliometric and visualization analysis. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 67(11), 4369–4390. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P., Huang, Y., Yang, C., & Jiang, W. (2023). Estimate the noise effect on automatic speech recognition accuracy for Mandarin by an approach associating articulation index. Applied Acoustics, 203, 109217. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Li, H., & Chen, F. (2020). EEG-based classification of imaginary Mandarin tones. 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), 3889–3892. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J., Tian, Y., Shi, Y., Huang, C., & Chang, E. (2004). Tone articulation modeling for Mandarin spontaneous speech recognition. 2004 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, 1, I–997. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N., & Xu, L. (2008). Development and evaluation of methods for assessing tone production skills in Mandarin-speaking children with cochlear implants. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 123(3), 1653–1664. [CrossRef]

| Study (Author, Year) | Traditional Model Architecture | Recognition Task | Average Four-Tone Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cao et al., 2000 | Decision Tree + HMM | Continuous (speech recognition) | 70.1 |

| Chang et al., 1990 | Shallow MLP | Isolated | 93.8 |

| Chen & Wang, 1995 | Shallow MLP and basic RNN | Continuous | 86.72 |

| Cheng et al., 2003 | HMM | Continuous | 81.8 |

| Cheng et al., 2020 | Wavelet transform + HMM | Isolated | 94.17 |

| Garg et al., 2018 | Hierarchical SVMs | Isolated | 97.93 |

| Hirose & Zhang, 1999 | HMM | Continuous | 82.5 |

| Hirose & Zhang, 2000 | HMM | Continuous | 85.5 |

| Jian & Tiecheng, 2000 | GMTM | Continuous | 60.0 |

| Lin, 2004 | HMM + clustering | Broadcast news with noise, continuous | 85.0 |

| Liu & Tao, 2013 | Fuzzy Algorithm | Continuous | 89.5 |

| Liu et al., 1999 | GMTM | Continuous | 61 |

| Liu et al., 2007 | GMM | Conversational telephone speech, continuous | 42.8 |

| Liu et al., 2013 | SVM + pitch smoothing | Isolated | 97.62 |

| Mou et al., 2020 | ANN | Isolated, clinical (post-stroke dysarthria) | 63.35 |

| Wang et al., 1994 | SRNN + MLP | Continuous | 93.1 |

| Wang et al., 2008 | MLP + tone nucleus modeling | Continuous | 80.9 |

| Wang et al., 2009 | SVM | Continuous | 93.52 |

| Xu et al., 2006 | ANN (cochlear) | Isolated, clinical children | 90.0 |

| Yan et al., 2023 | Random Forest with Feature Fusion | Isolated (+low data) | 95.0 |

| Yang et al., 2002 | HMM | Isolated | 96.53 |

| Zhang & Hirose, 2004 | HMM + tone nucleus modeling | Continuous | 83.1 |

| Zhang & Kawanami, 1999 | HMM | Continuous | 86.4 |

| Study (Author, Year) | Deep Learning Model Architecture | Recognition Task | Average Four-Tone Accuracy (%)* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gao et al., 2019 | CNN (ToneNet) | Isolated | 99.16 |

| Chen at al., 2016 | CNN + dAE | Isolated (children) | 95.53 |

| Yang et al., 2018a | CNN-DBLSTM-RNN | Continuous | 92.97 |

| Lin et al., 2018 | DNN | Continuous | 91.25 |

| Peng et al., 2021 | CNN-BiGRU | Continuous | 89.49 |

| Chen et al., 2014 | Deep Maxout Network | Continuous | 78.21 |

| Yang et al., 2018b | CNN-BLSTM-RNN + Attention | Continuous | 91.55 |

| Tang & Li., 2021 | End-to-end Res-NN | Continuous | 92.6 |

| Gao et al., 2020 | BLSTM + Target Approx. Model | Continuous | 87.56 |

| Huang et al., 2021 | Encoder-Decoder, DNN-bi-RNN with gating | Continuous | 87.60 |

| Hu et al., 2014 | CNN | Broadcast/conversational, continuous | 95.7 |

| Li et al., 2023 | Transformer, tone relabeling | Continuous | 87.2 |

| Ryant et al., 2014 | DNN (no pitch features) | Broadcast news, continuous | 84.44 |

| Wu et al., 2013 | NN (accented) | Continuous accented (Shanghai accent) | 70.2 |

| *Wang et al., 2023 | CNN (using EEG) | Neurotypical spoken tones, EEG imagery-based classification | 51.70 |

| Recognition Task | Resource Constraints | Recommended Approach | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolated monosyllables | High data availability with high computing resources | CNN with low-frequency mel-spectrogram input Ex: ToneNet |

Maximizes accuracy (>99%) by focusing on tone-relevant spectral regions; robust to noise |

| Isolated monosyllables | Low data for training, limited computing resources/mobile applications | Random Forest with feature fusion | Achieves >95% accuracy on tiny datasets (<600 syllables), real-time inference (<0.003s), ideal for mobile CALL apps |

| Continuous read speech | High data availability with high computing resources | CNN-BLSTM with attention | Captures bidirectional coarticulation and sandhi; lowest reported TER (7.03%) |

| Continuous spontaneous/conversational speech | High data availability with high computing resources | Multi-scale CNN-BiGRU with prosodic features | Handles variable tempo, intonation, and phrase-level effects; improves robustness in real-world settings |

| L2 learner or clinical speech, usually monosyllable | Limited data availability | BLSTM with soft-target tone labels, probabilistic approaches | Models ambiguous, non-canonical productions more effectively than hard classification; reduces EER to 5.13% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).