Submitted:

31 October 2025

Posted:

31 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

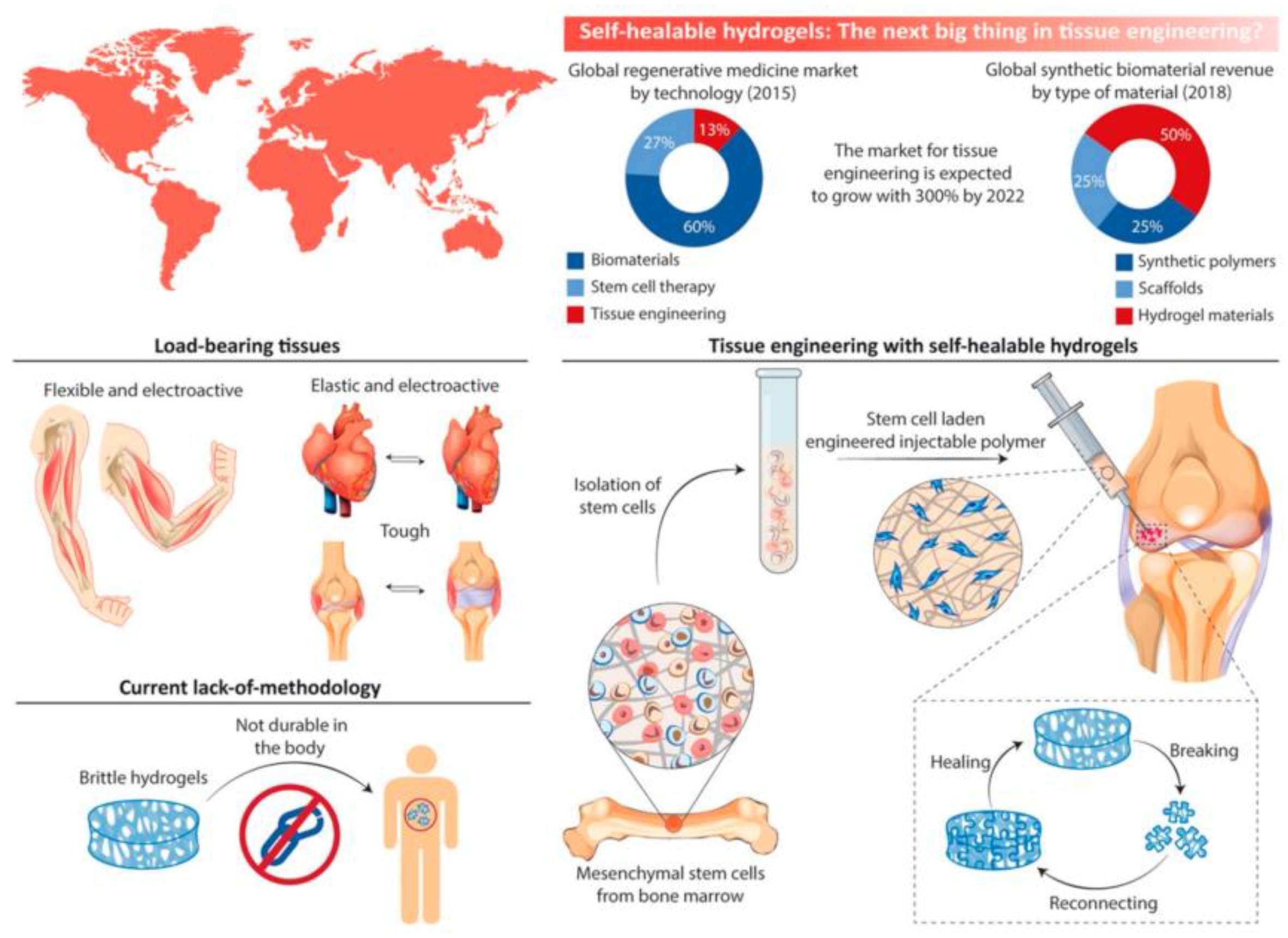

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Study Area Description

2.2. Experimental Design and Control Setup

2.3. Measurement Methods and Quality Control

2.4. Data Processing and Model Equations

3. Results and Discussion

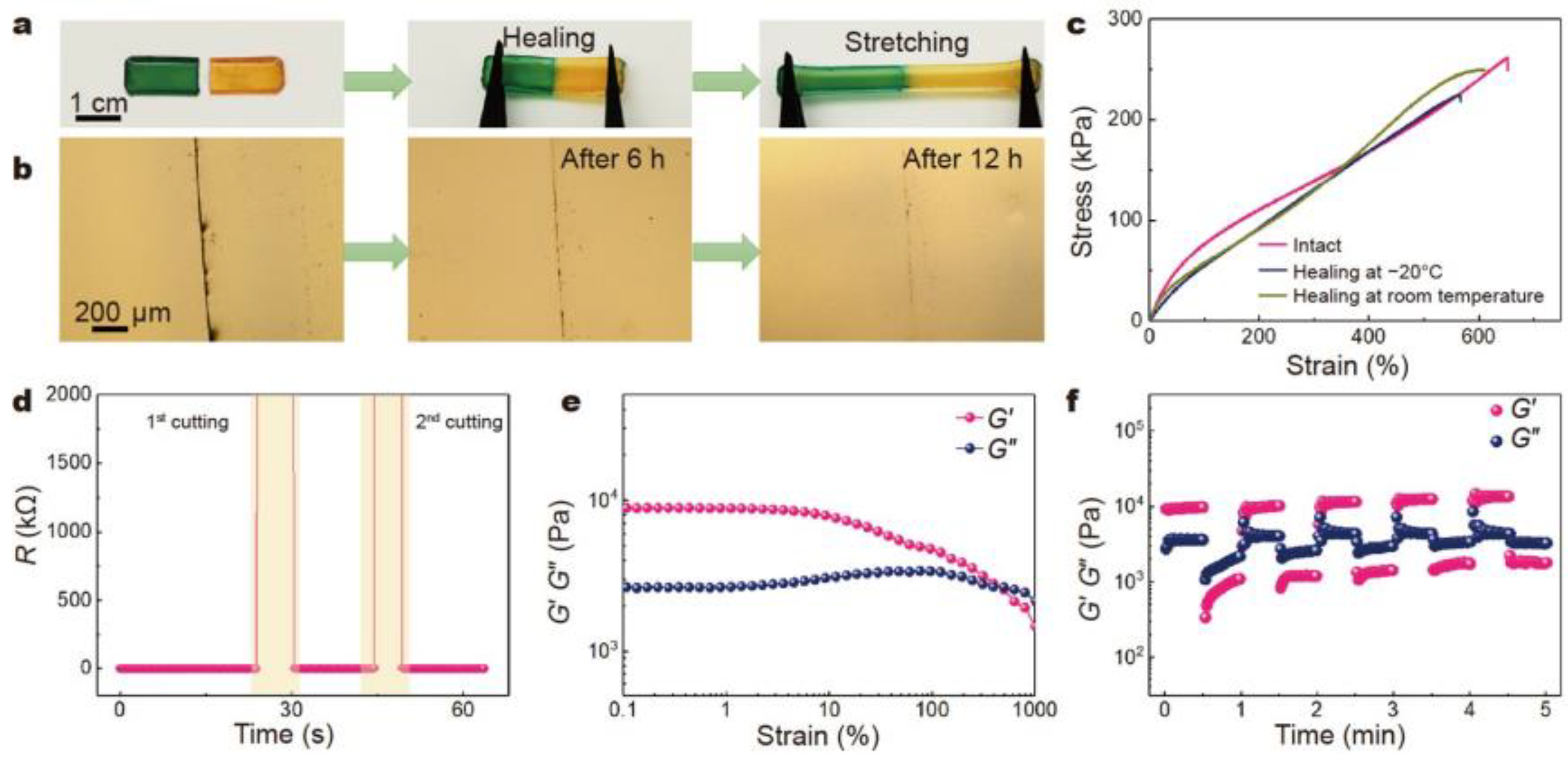

3.1. Touch Sensitivity Recovery Performance

3.2. Signal Stability and Electrical Noise After Healing

3.3. Durability Over Repeated Damage Cycles

3.4. Comparison with Existing Research and Application Implications

4. Conclusion

References

- Remy, C., Bates, O., Dix, A., Thomas, V., Hazas, M., Friday, A., & Huang, E. M. (2018, April). Evaluation beyond usability: Validating sustainable HCI research. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1-14).

- Wu, C., Chen, H., Zhu, J., & Yao, Y. (2025). Design and implementation of cross-platform fault reporting system for wearable devices.

- Stephanidis, C., & Salvendy, G. (Eds.). (2024). Designing for usability, inclusion and sustainability in human-computer interaction. CRC Press.

- Sharpe, R. G., Goodall, P. A., Neal, A. D., Conway, P. P., & West, A. A. (2018). Cyber-Physical Systems in the re-use, refurbishment and recycling of used Electrical and Electronic Equipment. Journal of cleaner production, 170, 351-361. [CrossRef]

- Tinga, T., & Loendersloot, R. (2019). Physical model-based prognostics and health monitoring to enable predictive maintenance. In Predictive maintenance in dynamic systems: Advanced methods, decision support tools and real-world applications (pp. 313-353). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Periyasamy, T., Asrafali, S. P., & Lee, J. (2025). Hydrogels for Translucent Wearable Electronics: Innovations in Materials, Integration, and Applications. Gels, 11(5), 372. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., Agate, S., Salem, K. S., Lucia, L., & Pal, L. (2020). Hydrogel-based sensor networks: Compositions, properties, and applications—A review. ACS Applied Bio Materials, 4(1), 140-162. [CrossRef]

- Li, S., Zhou, X., Dong, Y., & Li, J. (2020). Flexible self-repairing materials for wearable sensing applications: elastomers and hydrogels. Macromolecular Rapid Communications, 41(23), 2000444. [CrossRef]

- Narumi, K., Qin, F., Liu, S., Cheng, H. Y., Gu, J., Kawahara, Y., ... & Yao, L. (2019, October). Self-healing UI: Mechanically and electrically self-healing materials for sensing and actuation interfaces. In Proceedings of the 32nd Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (pp. 293-306).

- Hu, W. (2025, September). Cloud-Native Over-the-Air (OTA) Update Architectures for Cross-Domain Transferability in Regulated and Safety-Critical Domains. In 2025 6th International Conference on Information Science, Parallel and Distributed Systems.

- Wang, C., Smieszek, N., & Chakrapani, V. (2021). Unusually high electron affinity enables the high oxidizing power of layered birnessite. Chemistry of Materials, 33(19), 7805-7817. [CrossRef]

- Stuart-Smith, R., Studebaker, R., Yuan, M., Houser, N., & Liao, J. (2022). Viscera/L: Speculations on an Embodied, Additive and Subtractive Manufactured Architecture. Traits of Postdigital Neobaroque: Pre-Proceedings (PDNB), edited by Marjan Colletti and Laura Winterberg. Innsbruck: Universitat Innsbruck.

- Sun, X., Wei, D., Liu, C., & Wang, T. (2025). Multifunctional Model for Traffic Flow Prediction Congestion Control in Highway Systems. Authorea Preprints.

- Kim, S. H., Kim, Y., Choi, H., Park, J., Song, J. H., Baac, H. W., ... & Son, D. (2021). Mechanically and electrically durable, stretchable electronic textiles for robust wearable electronics. RSC advances, 11(36), 22327-22333. [CrossRef]

- Chen, F., Li, S., Liang, H., Xu, P., & Yue, L. (2025). Optimization Study of Thermal Management of Domestic SiC Power Semiconductor Based on Improved Genetic Algorithm.

- Zhu, W., & Yang, J. (2025). Causal Assessment of Cross-Border Project Risk Governance and Financial Compliance: A Hierarchical Panel and Survival Analysis Approach Based on H Company's Overseas Projects.

- Wu, C., Zhu, J., & Yao, Y. (2025). Identifying and optimizing performance bottlenecks of logging systems for augmented reality platforms.

- Zarepour, A., Ahmadi, S., Rabiee, N., Zarrabi, A., & Iravani, S. (2023). Self-healing MXene-and graphene-based composites: properties and applications. Nano-micro letters, 15(1), 100. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).