Submitted:

31 October 2025

Posted:

31 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- We propose a MIENet to estimate target state and motion patterns from non-Gaussian observation noise. The multi-domain information of target trajectories can be well incorporated, thus helping to infer the latent state of targets.

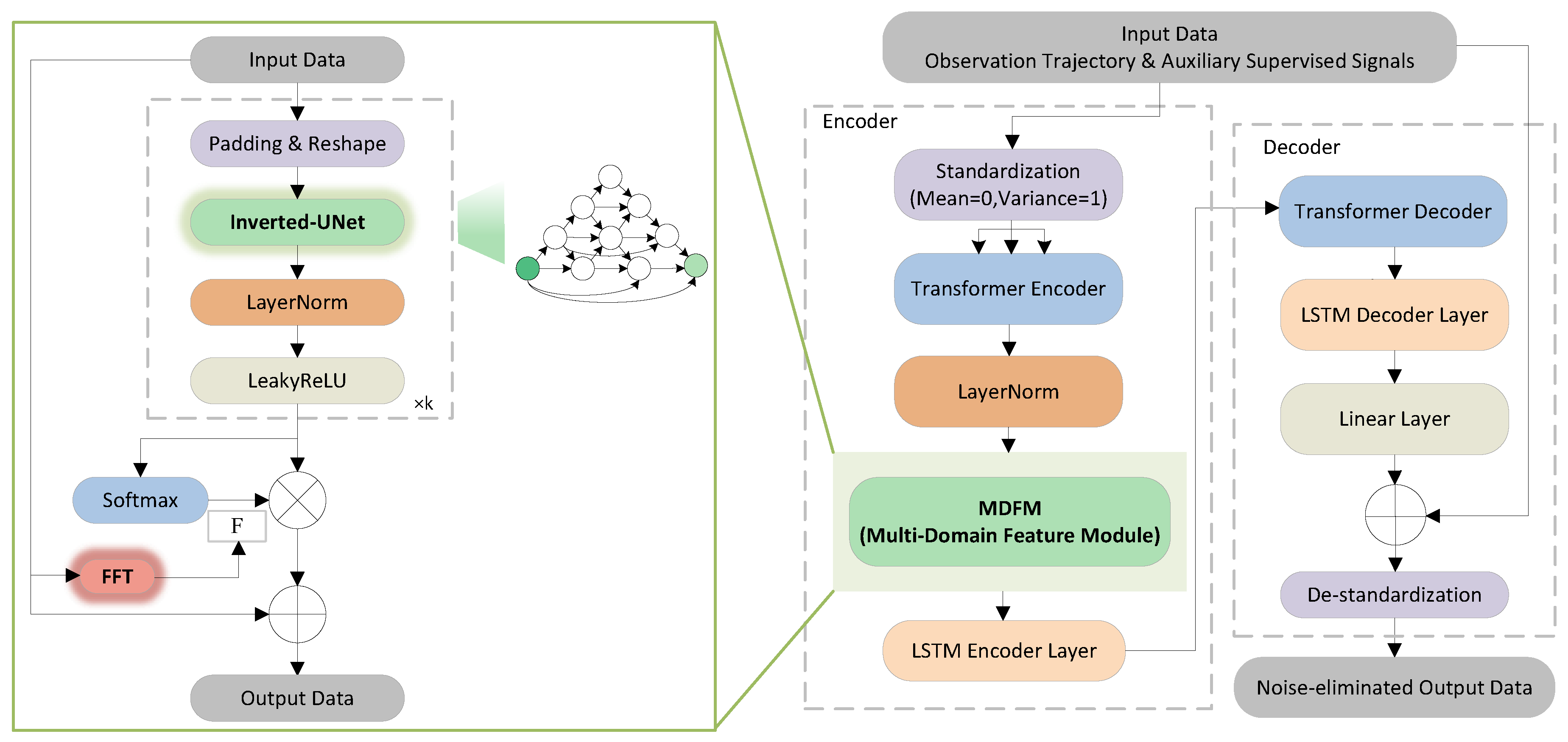

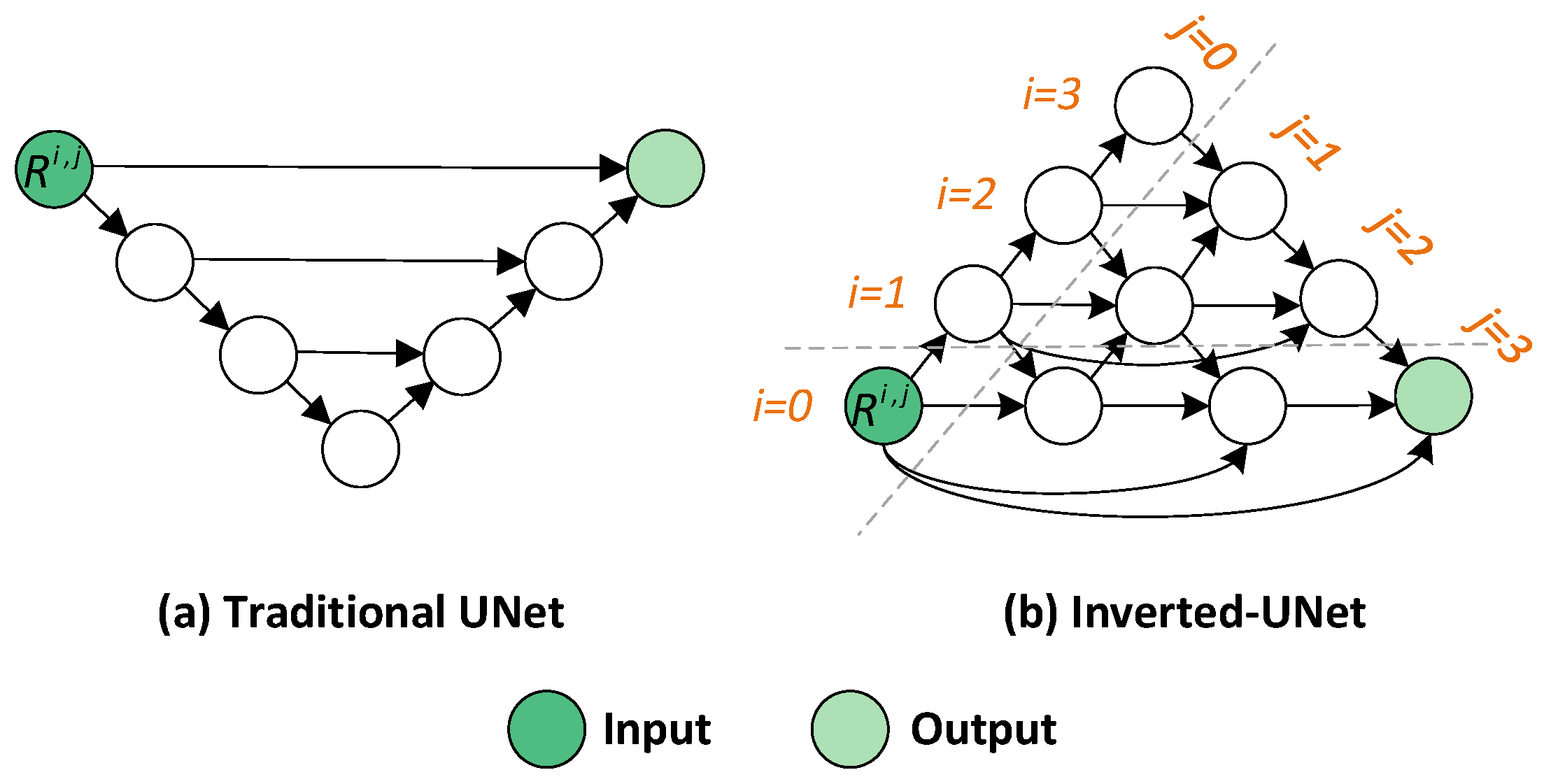

- We design a FDM to handle noise with varying intensities and distributions. It employs a novel Inverted-UNet and FFT-based weighting to integrate temporal, spatial, and frequency-domain features within an encoder–decoder framework.

- We develop a PEM to estimate target motion patterns by fusing local and global spatial–temporal features. Considering that the state transition matrix () characterizes motion dynamics and enables trajectory inference, we further introduce a physically constrained loss function (PCLoss) to help PEM estimate the key turn rate parameter () in .

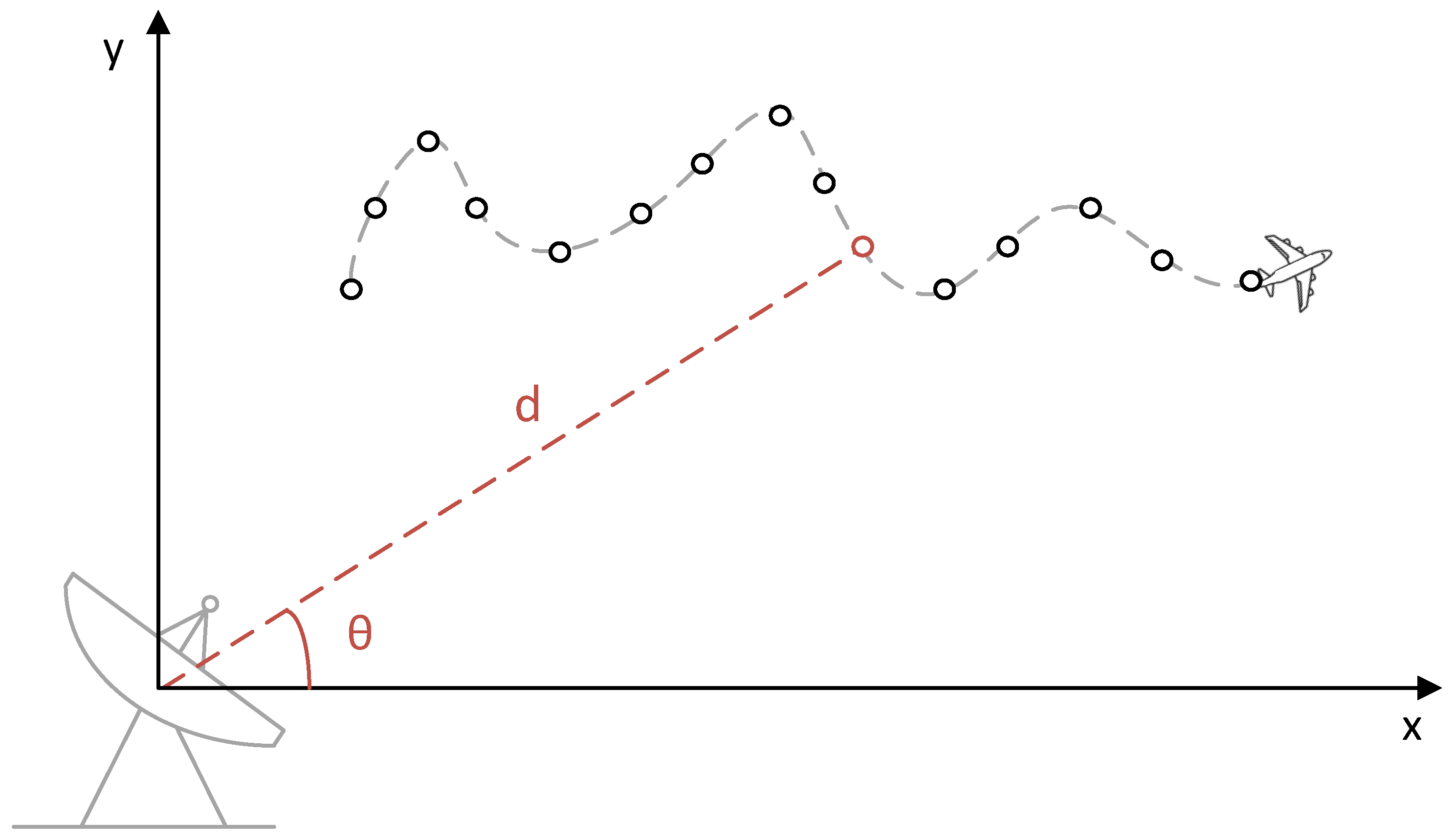

2. Problem Formulation

2.1. State Equation

2.2. Observation Equation

2.3. Problem Addressed in This Work

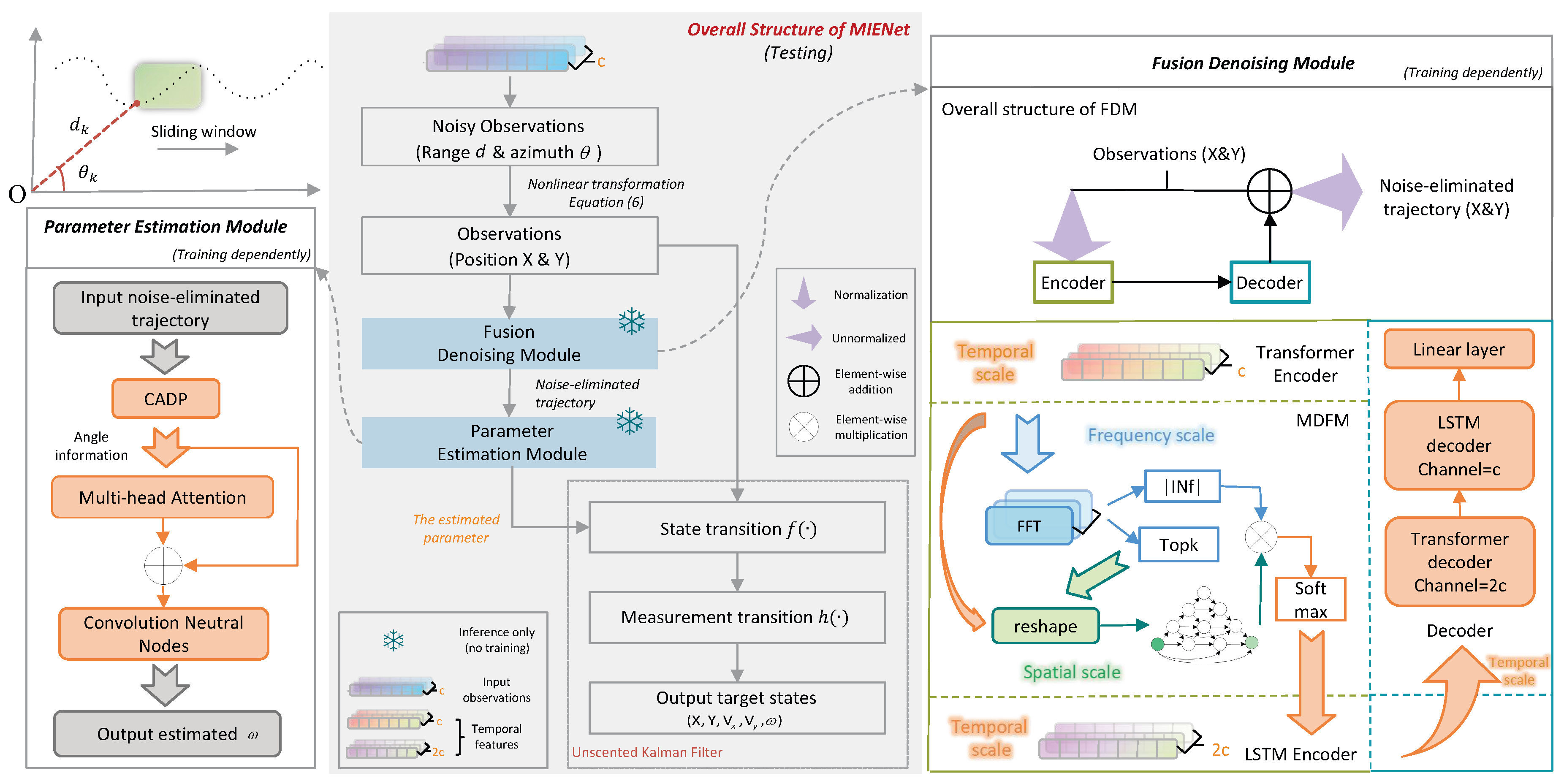

3. Multi-Domain Intelligent State Estimation Network

3.1. Overall Architecture

| Algorithm 1 MIENet tracking process |

|

3.2. Fusion Denoising Model

3.2.1. Motivation

3.2.2. The Overall Structure of FDM

3.2.3. The Multi-Domain Feature Module

- (1)

- The Inverted-UNet

- (2)

- FFT-Based Weighting

3.3. Parameter Estimation Model

3.3.1. Motivation

3.3.2. The Overall Structure of PEM

3.3.3. Physics-Constrained Loss Function

4. Experiments

4.1. Implementation Details

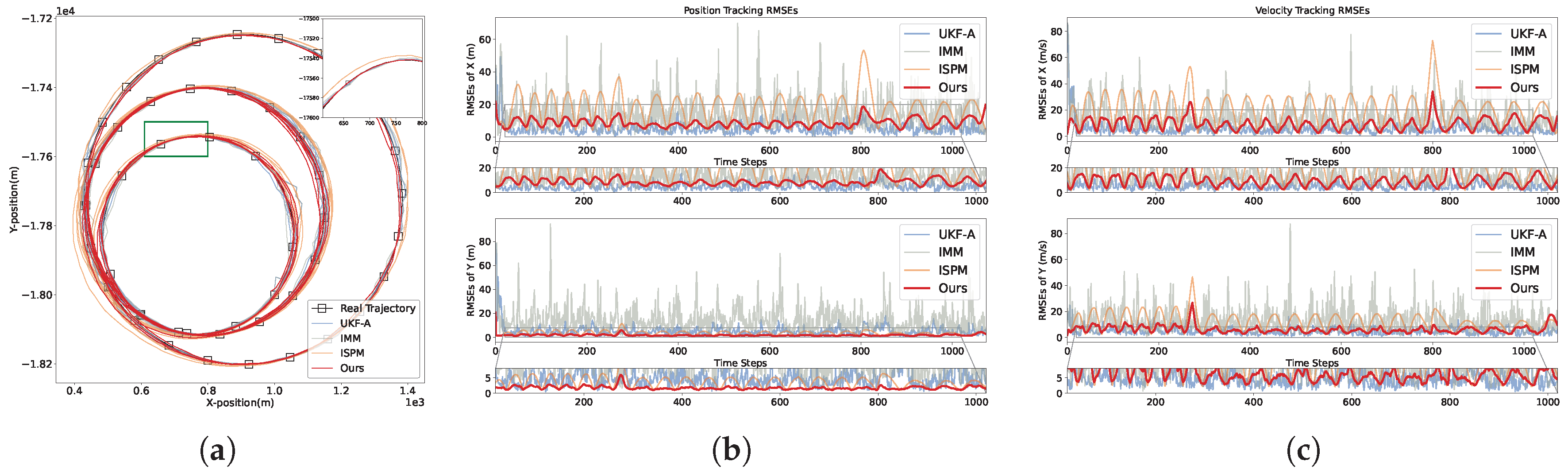

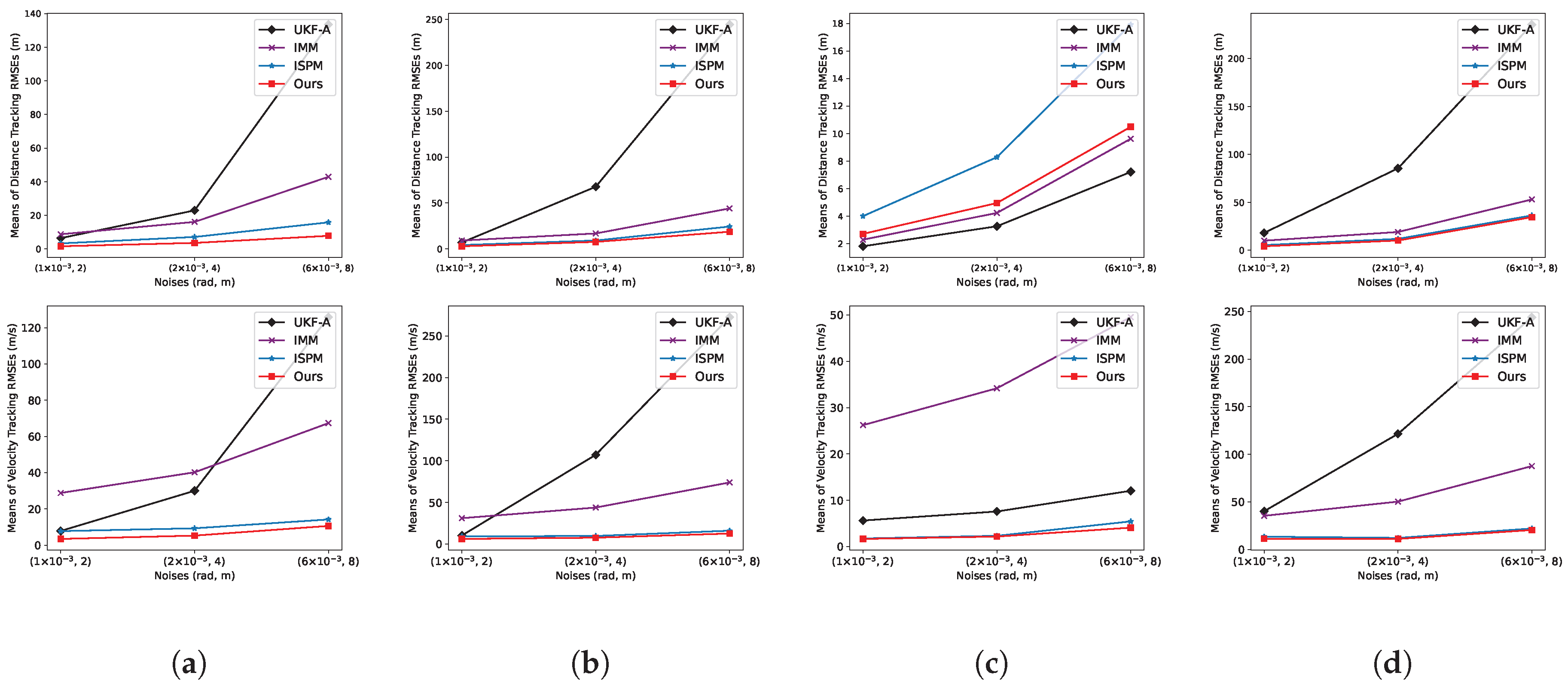

4.2. Comparison to the State-of-the-Art (SOTA)

4.2.1. Quantitative Results

- (1)

- The LAST Dataset

- (2)

- The SV248S Dataset

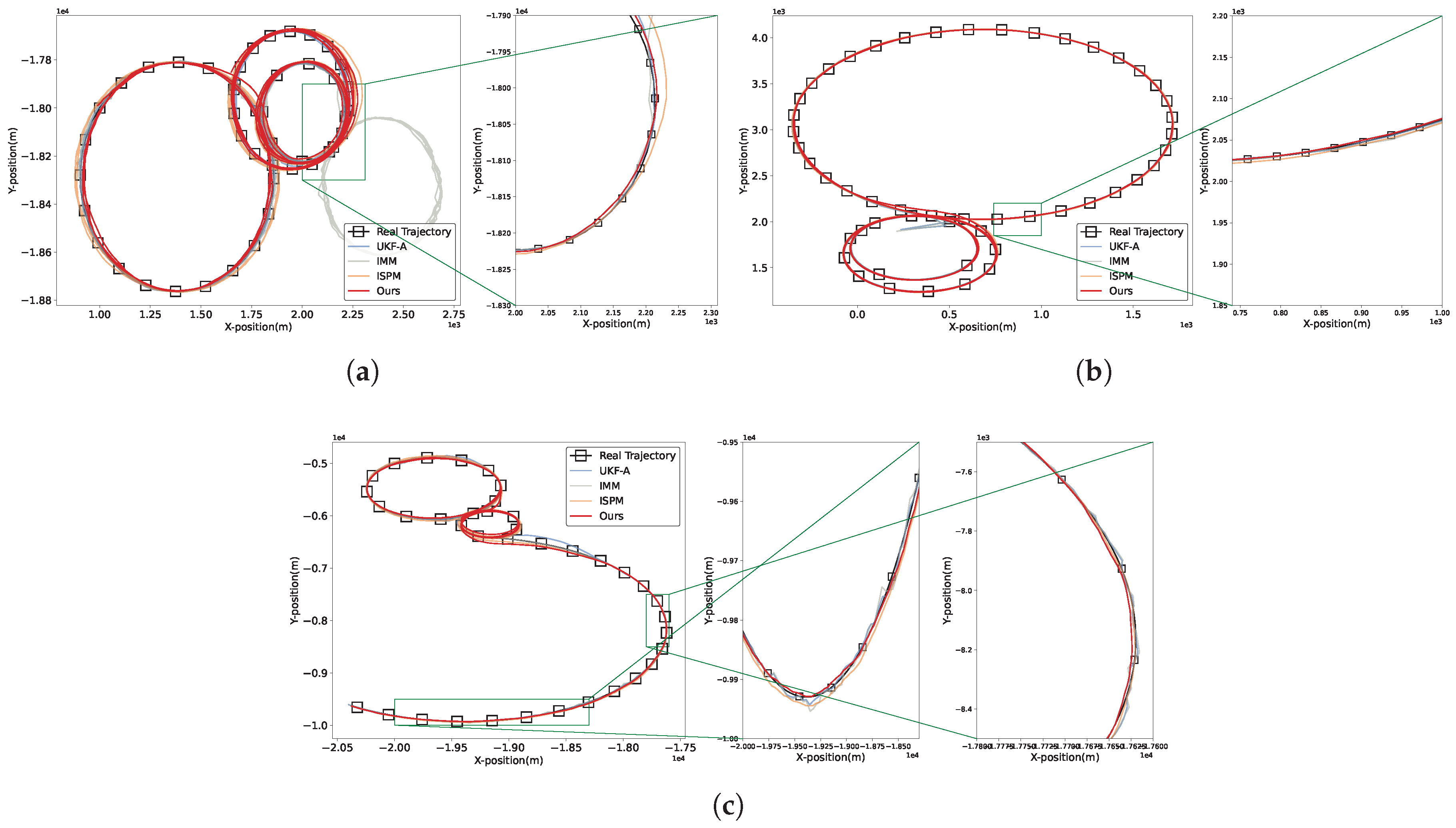

4.2.2. Qualitative Results

- (1)

- The LAST Dataset

- (2)

- The SV248S Dataset

4.3. Ablation Study

4.3.1. Ablation Study on the Magnitude and Distribution of Noise

4.3.2. Ablation Study on MDFM

- FDM w/o MDFM: As shown in Table 8, the original FDM achieves a 61.2% reduction in RMSE, while removing the MDFM module decreases the reduction to 48.3%. The results are averaged over three noise intensity levels. This performance gap demonstrates that the Inverted-UNet is essential for denoising, as it extracts and fuses spatial-domain features more effectively from noisy observations.

- MIENet w/o MDFM: As shown in Table 9, our MIENet achieves position and velocity RMSEs of 7.78m and 10.64m/s, respectively. In ablation 1, removing the MDFM module increases RMSEs to 15.83m and 29.61m/s. That is because, FDM, as a component of MIENet, effectively suppresses noise and thereby contributes to its tracking performance.

4.3.3. Ablation Study on Multi-head Attention

4.3.4. Ablation Study on Loss Function Design

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, Z.; Zhu, E.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, P.; Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Predictive Autonomy for UAV Remote Sensing: A Survey of Video Prediction. Remote Sensing 2025, 17, 3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraternali, P.; Morandini, L.; Motta, R. Enhancing Search and Rescue Missions with UAV Thermal Video Tracking. Remote Sensing 2025, 17, 3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, D.; Ding, B.; Tong, X.; Sun, B.; Sun, X.; Guo, R.; Su, S. FSTC-DiMP: Advanced Feature Processing and Spatio-Temporal Consistency for Anti-UAV Tracking. Remote Sensing 2025, 17, 2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Tang, D.; Zhou, H.; Xiang, X. Moving Target Geolocation and Trajectory Prediction Using a Fixed-Wing UAV in Cluttered Environments. Remote Sensing 2025, 17, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, G.; Li, Z.; Ding, K. Visual detection and association tracking of dim small ship targets from optical image sequences of geostationary satellite using multispectral radiation characteristics. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Sun, H.; Wang, T. IAASNet: Ill-Posed-Aware Aggregated Stereo Matching Network for Cross-Orbit Optical Satellite Images. Remote Sensing 2025, 17, 3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Fu, G.; Yang, X.; Cao, X.; Niu, S.; Meng, Z. Two-Stage Spatio-Temporal Feature Correlation Network for Infrared Ground Target Tracking. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2024, 62, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; He, W.; Deng, L.; Wu, Y.; Xie, H.; Dai, J. Trajectory tracking and load monitoring for moving vehicles on bridge based on axle position and dual camera vision. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 4868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Chen, P.; Xu, G.; Sun, H.; Li, L.; Yu, G. Adaptive Path-Tracking Controller Embedded With Reinforcement Learning and Preview Model for Autonomous Driving. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2025, 74, 3736–3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, L.; Yu, Z. Towards Robust Visual Object Tracking for UAV With Multiple Response Incongruity Aberrance Repression Regularization. IEEE Signal Processing Letters 2024, 31, 2005–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Xu, M. DeepMTT: A deep learning maneuvering target-tracking algorithm based on bidirectional LSTM network. Information Fusion 2020, 53, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yan, J.; Wan, D.; Li, X.; Al-Rubaye, S.; Al-Dulaimi, A.; Quan, Z. Digital Twins Based Intelligent State Prediction Method for Maneuvering-Target Tracking. IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications 2023, 41, 3589–3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, X.P.; He, Y. A deep learning model based on transformer structure for radar tracking of maneuvering targets. Information Fusion 2024, 103, 102120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.R.; Jilkov, V.P. Survey of maneuvering target tracking. Part I. Dynamic models. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems 2003, 39, 1333–1364. [Google Scholar]

- Kalman, R.E. A new approach to linear filtering and prediction problems. 1960, 82, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, E.; Otero, D.; D’Attellis, C.E. Maneuvering target tracking using extended kalman filter. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems 1991, 27, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julier, S.; Uhlmann, J.; Durrant-Whyte, H.F. A new method for the nonlinear transformation of means and covariances in filters and estimators. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control 2000, 45, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, F.; Gunnarsson, F.; Bergman, N.; Forssell, U.; Jansson, J.; Karlsson, R.; Nordlund, P.J. Particle filters for positioning, navigation, and tracking. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2002, 50, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, H.A.; Bar-Shalom, Y. The interacting multiple model algorithm for systems with markovian switching coefficients. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control 1988, 33, 780–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, H.; Zhao, W.; Wang, J. Interacting multiple model tracking algorithm fusing input estimation and best linear unbiased estimation filter. IET Radar Sonar and Navigation 2017, 11, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yuan, B.; Miao, Z.; Wu, W. From GMM to HGMM: An approach in moving object detection. Computing and Informatics 2004, 23, 215–237. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Zang, C.; Wang, X.; Xiang, Y.; Cui, G. Data-Driven Intelligent Multi-Frame Joint Tracking Method for Maneuvering Targets in Clutter Environments. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, Y.; Masouros, C.; You, X.; Ottersten, B. Hybrid Data-Induced Kalman Filtering Approach and Application in Beam Prediction and Tracking. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2024, 72, 1412–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Z.; Liu, K.; Chen, B. Converted state equation kalman filter for nonlinear maneuvering target tracking. Signal Processing 2022, 202, 108741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Davies, M.E.; Proudler, I.K.; Hopgood, J.R. Adaptive kernel kalman filter based belief propagation algorithm for maneuvering multi-target tracking. IEEE Signal Processing Letters 2022, 29, 1452–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Mishra, K.V.; Chattopadhyay, A. Inverse Unscented Kalman Filter. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2024, 72, 2692–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, H.; Hu, J.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, Q. Variational nonlinear kalman filtering with unknown process noise covariance. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems 2023, 59, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, Z.; Luo, X.; Zhou, Z. Trajectory optimization of target motion based on interactive multiple model and covariance kalman filter. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Geoscience and Remote Sensing Mapping (GRSM), 2023. [CrossRef]

- Deepika, N.; Rajalakshmi, B.; Nijhawan, G.; Rana, A.; Yadav, D.K.; Jabbar, K.A. Signal processing for advanced driver assistance systems in autonomous vehicles. In Proceedings of the IEEE Uttar Pradesh Section International Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Computer Engineering (UPCON), 2023. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Rice, M.; Rice, F.; Wu, X. An expectation-maximization-based estimation algorithm for AOA target tracking with non-Gaussian measurement noises. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2022, 72, 498–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; He, J.; Wang, G.; Peng, B. A Maritime Multi-target Tracking Method with Non-Gaussian Measurement Noises based on Joint Probabilistic Data Association. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; He, J.; Peng, B.; Wang, G. Generalized interacting multiple model Kalman filtering algorithm for maneuvering target tracking under non-Gaussian noises. ISA transactions 2024, 155, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Wu, Z. Maximum correntropy quadrature Kalman filter based interacting multiple model approach for maneuvering target tracking. Signal, Image and Video Processing 2025, 19, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Sun, L.; Wen, T.; Hei, X.; Qian, F. Adaptive transition probability matrix-based parallel IMM algorithm. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics: Systems 2019, 51, 2980–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Wang, S.; Qiu, M. Maneuvering target tracking based on LSTM for radar application. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Software Engineering and Artificial Intelligence (SEAI). IEEE, 2023, pp. 235–239. [CrossRef]

- Medsker, L.R.; Jain, L.; et al. Recurrent neural networks. Design and applications 2001, 5, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, A.; Schmidhuber, J. Framewise phoneme classification with bidirectional LSTM and other neural network architectures. Neural networks 2005, 18, 602–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawakami, K. Supervised sequence labelling with recurrent neural networks. PhD thesis, Ph. D. thesis, 2008.

- Zhang, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, X.P.; He, Y. Transformer-based tracking network for maneuvering targets. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2023-2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Su, H.; Li, Z.; Jia, C.; Yang, R. Self-attention-based Transformer for nonlinear maneuvering target tracking. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2023, 61, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Sun, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X. Physics-Informed Data-Driven Autoregressive Nonlinear Filter. IEEE Signal Processing Letters 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revach, G.; Shlezinger, N.; Ni, X.; Escoriza, A.L.; Van Sloun, R.J.; Eldar, Y.C. KalmanNet: Neural network aided Kalman filtering for partially known dynamics. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2022, 70, 1532–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, G.; Park, J.; Shlezinger, N.; Eldar, Y.C.; Lee, N. Split-KalmanNet: A robust model-based deep learning approach for state estimation. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2023, 72, 12326–12331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchnik, I.; Revach, G.; Steger, D.; Van Sloun, R.J.; Routtenberg, T.; Shlezinger, N. Latent-KalmanNet: Learned Kalman filtering for tracking from high-dimensional signals. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2024, 72, 352–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, M.; Shafieezadeh, A. Cholesky-KalmanNet: Model-Based Deep Learning With Positive Definite Error Covariance Structure. IEEE Signal Processing Letters 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Lu, K.; Sun, C. Deep Learning Aided State Estimation for Guarded Semi-Markov Switching Systems With Soft Constraints. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2023, 71, 3100–3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, R.; Lan, J.; Cao, X. Nonlinear Estimation Using Multiple Conversions With Optimized Extension for Target Tracking. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2023, 71, 4457–4470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortada, H.; Falcon, C.; Kahil, Y.; Clavaud, M.; Michel, J.P. Recursive KalmanNet: Deep Learning-Augmented Kalman Filtering for State Estimation with Consistent Uncertainty Quantification. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.11639 2025. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, Y. Normalizing Flow-Based Differentiable Particle Filters. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Ma, J.; Kouw, W.M. Multiple Variational Kalman-GRU for Ship Trajectory Prediction With Uncertainty. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Li, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Yu, X.; Guo, L. KFDNNs-Based Intelligent INS/PS Integrated Navigation Method Without Statistical Knowledge. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y. AKansformer: Axial Kansformer–Based UUV Noncooperative Target Tracking Approach. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Chen, J.; Yu, G.; Zhai, Z.; Han, P. KalmanFormer: using transformer to model the Kalman Gain in Kalman Filters. Frontiers in Neurorobotics 2025, 18, 1460255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zheng, Y.; Lin, D.; Cai, P.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, S. MAML-KalmanNet: A neural network-assisted Kalman filter based on model-agnostic meta-learning. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuri, I.; Shlezinger, N. Learning Flock: Enhancing Sets of Particles for Multi Sub-State Particle Filtering with Neural Augmentation. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Xiong, W.; Cui, Y. An adaptive interactive multiple-model algorithm based on end-to-end learning. Chinese Journal of Electronics 2023, 32, 1120–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jiao, L.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, R.; Song, X.; Tian, C.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, F.; Yang, S.; et al. Deep learning-based object tracking in satellite videos: A comprehensive survey with a new dataset. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Magazine 2022, 10, 181–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.M.; Liu, T.J.; Liu, K.H. SUNet: Swin transformer UNet for image denoising. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS). IEEE, 2022, pp. 2333–2337. [CrossRef]

- Vafa, K.; Chang, P.G.; Rambachan, A.; Mullainathan, S. What has a foundation model found? using inductive bias to probe for world models. International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2025. [CrossRef]

- Holleman, E.C. Flight investigation of the roll requirements for transport airplanes in cruising flight. Technical report, 1970.

- Zhang, X.; Rong, R. Indoor Target Tracking Based on Maximum Likelihood Estimation and Kalman Filtering. Mobile Communications 2021, pp. 86–90. Mobile Communications.

- Chen, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Tang, Y.; He, J.; Han, T. STAR: A Unified Spatiotemporal Fusion Framework for Satellite Video Object Tracking. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Contents | Ranges |

|---|---|

| Initial distance from radar | [1 km, 10 km] |

| Initial velocity of targets | [100, 200m/s] |

| Initial distance azimuth | [-180°, 180°] |

| Initial velocity azimuth | [-180°, 180°] |

| Maneuvering turn rate | [-90°/s, 90°/s] |

| Variance of accelerated velocity noise | 10(m/s)2 |

| Trajectories | Initial state | The first part | The second Part | The third part |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [1000m, -18000m, 150m/s, 200m/s] | 27.4s, =50°/s | 52.6s, =40°/s | 27.4s, =30°/s |

| 2 | [1000m, -18000m, 150m/s, 200m/s] | 40s, =-30°/s | 27.4s, =70°/s | 40s, =50°/s |

| 3 | [500m, 2000m, -300m/s, 200m/s] | 25s, =60°/s | 42.4s, =50°/s | 40s, =-20°/s |

| 4 | [-20000m, -5000m, 250m/s, 180m/s] | 30s, =-30°/s | 17.4s, =70°/s | 20.9s, =-10°/s |

| Trajectories p(m) / v(m/s) |

Noise standard deviation (azimuth, range) |

UKF-A [61] | IMM [19] | ISPM [12] | MIENet (ours) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (1×rad, 2m) | Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 |

6.667/11.38 6.329/7.463 6.457/7.963 |

9.193/32.57 8.689/28.72 8.366/25.87 |

3.770/7.920 3.370/8.030 2.490/7.040 |

1.800/4.170 1.500/3.100 1.350/3.100 |

| All | 6.420/7.860 | 8.720/28.84 | 3.280/7.770 | 1.580/3.470 | ||

| (2×rad, 4m) | Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 |

39.73/64.94 13.23/13.67 10.86/10.17 |

17.01/47.30 15.92/39.23 15.52/36.66 |

7.950/9.570 7.360/9.630 5.500/8.410 |

4.650/6.150 2.650/4.380 3.310/4.870 |

|

| All | 22.90/30.05 | 16.07/40.23 | 7.110/9.330 | 3.570/5.300 | ||

| (6×rad, 8m) | Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 |

139.2/208.9 136.4/124.3 132.7/109.7 |

62.80/147.8 41.62/63.69 40.46/60.04 |

17.80/13.59 15.88/14.67 13.26/13.83 |

9.170/10.15 7.250/12.20 4.520/8.590 |

|

| All | 133.5/125.8 | 42.90/67.37 | 15.80/14.21 | 7.780/10.64 | ||

| 2 | (1×rad, 2m) | Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 |

6.854/8.294 10.10/26.66 6.494/8.489 |

9.481/33.15 8.692/29.30 9.013/30.38 |

2.640/7.170 5.560/12.70 4.350/8.570 |

1.790/4.930 3.340/9.200 3.870/7.260 |

| All | 6.920/10.36 | 9.090/31.10 | 4.170/9.290 | 2.840/6.190 | ||

| (2×rad, 4m) | Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 |

12.04/12.22 94.06/172.2 83.27/118.6 |

17.95/45.88 15.82/44.09 16.33/42.03 |

5.600/8.870 11.74/10.53 9.970/10.07 |

3.440/6.190 10.06/9.740 11.53/10.58 |

|

| All | 67.66/107.1 | 16.78/43.87 | 9.110/9.750 | 7.600/7.690 | ||

| (6×rad, 8m) | Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 |

121.2/127.0 223.4/293.5 275.9/301.5 |

54.83/96.77 39.80/76.48 41.08/67.76 |

11.62/11.72 28.47/17.84 35.27/20.49 |

6.540/7.930 17.26/15.48 32.28/17.27 |

|

| All | 244.4/272.4 | 44.05/73.98 | 24.30/16.07 | 18.65/12.64 | ||

| 3 | (1×rad, 2m) | Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 |

1.651/5.706 1.561/5.125 2.214/6.587 |

2.106/24.70 2.010/25.08 2.723/28.50 |

5.030/1.810 4.590/1.650 2.320/1.870 |

3.300/1.920 2.590/1.550 3.120/1.760 |

| All | 1.810/5.640 | 2.290/26.23 | 4.000/1.770 | 2.710/1.670 | ||

| (2×rad, 4m) | Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 |

2.953/8.071 2.758/6.747 4.097/9.735 |

3.882/32.96 3.730/32.38 5.018/36.97 |

10.31/2.440 9.540/2.150 4.760/2.470 |

6.400/2.670 5.690/2.270 4.090/1.770 |

|

| All | 3.260/7.590 | 4.230/34.19 | 8.280/2.340 | 4.950/2.180 | ||

| (6×rad, 8m) | Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 |

6.277/14.22 5.747/10.03 9.921/18.34 |

8.626/50.51 8.169/46.74 11.79/52.27 |

22.15/5.630 21.03/3.200 9.160/7.020 |

14.98/5.070 10.43/4.040 8.120/3.980 |

|

| All | 7.210/12.06 | 9.620/49.53 | 17.92/5.450 | 10.49/4.100 | ||

| 4 | (1×rad, 2m) | Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 |

8.420/16.20 15.38/43.98 42.29/77.72 |

10.47/39.53 9.549/33.30 9.838/31.73 |

3.530/9.050 8.440/19.11 4.650/13.54 |

3.650/9.910 6.380/17.36 1.300/3.490 |

| All | 18.13/40.22 | 10.01/35.40 | 5.430/13.49 | 4.180/11.38 | ||

| (2×rad, 4m) | Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 |

28.23/43.75 99.56/175.2 114.5/124.9 |

20.41/55.48 17.93/50.32 18.37/44.73 |

7.150/11.13 18.42/13.35 10.81/12.76 |

8.440/6.140 16.01/18.94 2.370/6.230 |

|

| All | 85.48/121.5 | 19.06/50.31 | 11.89/12.21 | 10.16/11.14 | ||

| (6×rad, 8m) | Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 |

159.9/195.7 301.7/361.7 207.8/114.6 |

72.75/154.2 43.35/85.78 49.05/72.03 |

25.64/14.89 53.94/31.10 34.12/23.23 |

24.62/9.770 57.04/33.48 12.61/16.75 |

|

| All | 235.5/244.0 | 53.04/87.63 | 36.33/22.10 | 34.57/20.50 |

| Category-Wise Evaluations | Difficulty-Wise Evaluations | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | L-Vehicle | Airplane | Ship | Simple | Normal | Hard | ||||||||

| Trackers | PR | SR | PR | SR | PR | SR | PR | SR | PR | SR | PR | SR | PR | SR |

| STAR [62] | 0.7542 | 0.4911 | 0.8739 | 0.6555 | 0.8399 | 0.7517 | 1.0000 | 0.7562 | 0.8800 | 0.6228 | 0.7138 | 0.4653 | 0.6652 | 0.4177 |

| Ours | 0.7550 | 0.4944 | 0.8744 | 0.6598 | 0.8399 | 0.7530 | 1.0000 | 0.7611 | 0.8816 | 0.6278 | 0.7138 | 0.4675 | 0.6760 | 0.4440 |

| Trackers | STO | LTO | DS | IV | BCH | SM | ND | CO | BCL | IPR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAR [62] | 0.676/0.444 | 0.472/0.301 | 0.731/0.489 | 0.692/0.446 | 0.796/0.534 | 0.700/ 0.462 | 0.752/0.489 | 0.700/0.444 | 0.730/0.458 | 0.697/0.464 |

| Ours | 0.676/ 0.447 | 0.473/0.302 | 0.731/0.492 | 0.693/0.449 | 0.797/0.538 | 0.700/0.461 | 0.753/ 0.490 | 0.700/ 0.447 | 0.730/ 0.460 | 0.697/ 0.466 |

| Methods RMSE(m) |

Gaussian-injected Noise (rad, m) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| (2, 4) | (8, 10) | (11,13) | |

| Original Observation | 35.310 | 140.94 | 193.77 |

| Butterworth Filter | 28.000 | 112.09 | 153.65 |

| ISPM-NEN [12] | 17.359 | 61.978 | 84.804 |

| FDM (ours) |

13.593 (↓61.5%) |

43.690 (↓69.0%) |

61.135 (↓68.4%) |

| Methods RMSE(m) |

Uniform-injected Noise (rad, m) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| (12, 21.3) | (40.3, 56.3) | (75, 133.3) | |

| Original Observation | 61.536 | 112.78 | 153.84 |

| Butterworth Filter | 47.836 | 87.673 | 119.59 |

| ISPM-NEN [12] | 28.994 | 52.348 | 71.290 |

| FDM (ours) |

23.295 (↓62.1%) |

40.333 (↓64.2%) |

54.277 (↓64.7%) |

| Methods RMSE(m) |

Noise | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (2 × rad, 4m) | (8 × rad, 10m) | (11 × rad, 13m) | |||

| FDM w/o MDFM |

pos(m) | Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 |

15.53 16.34 15.69 |

49.34 42.67 44.04 |

74.20 58.67 62.43 |

| All | 15.97 (↓36.3%) |

44.81 (↓55.2%) |

63.91 (↓53.5%) |

||

| Ours | pos(m) | Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 |

11.63 10.25 9.96 |

39.28 33.58 38.76 |

55.11 46.97 57.77 |

| All | 10.55 (↓57.9%) |

36.45 (↓63.5%) |

52.02 (↓62.1%) |

||

| Tracking variations |

MDFM | MHN | PCLoss | Distance (m) / Velocity (m/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ablation 1 | ✓ | ✓ | 15.83 / 29.61 | |

| Ablation 2 | ✓ | ✓ | 16.90 / 14.07 | |

| Ablation 3 | ✓ | ✓ | 9.900 / 13.55 | |

| Ours | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 7.780 / 10.64 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).