1. Introduction

Broadacre farming systems—especially large-scale, rainfed cropping systems, which account for nearly three-quarters of the world’s cropland extent [

1]—are under increasing pressure due to climate variability and resource stresses [

2,

3]. Rising temperatures, shifting rainfall patterns, and more frequent extreme weather events are already undermining crop yields and farm profits [

2,

4,

5]. For example, in Australia’s grain belt, climate change since 2000 has cut average broadacre farm profitability by about 22% [

6,

7]. Recent record-breaking droughts (e.g. the driest early-season period on record in 2024) across the south-west region of Western Australia delayed crop sowing and emergence, highlighting the vulnerability of current practices to climate extremes [

6]. Global studies likewise confirm that climate variability, especially heatwaves and drought, is a dominant driver of year-to-year yield fluctuations, accounting for roughly 20-49% of global crop yield variability [

2,

5,

8]. Concurrent hot-and-dry extremes have consistently negative impacts on major crops, and their occurrence is increasing. For example, the frequency of extreme hot/dry conditions during wheat seasons has risen several-fold in recent decades [

9]. These trends threaten the reliability of crop production, making resilience a critical goal for broadacre agriculture [

9,

10]. In this context, resilience is defined as the capacity of the agricultural system to withstand, recover from, and adapt after disturbances [

10]. Achieving resilience in broadacre cropping means maintaining productivity under variable climate and resource conditions and quickly rebounding from stress events. However, developing truly resilient farming systems is challenging because multiple stressors (such as drought, heat, pests and disease) often occur in combination [

6]. There is a need for improved monitoring and management strategies that can handle this complexity and safeguard yield stability and farm incomes under a changing climate.

Remote sensing (RS) technologies—encompassing spaceborne, airborne, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs/drones), and proximal sensors—have revolutionized crop monitoring by providing multi-scale, non-destructive observations throughout the growing season [

11]. These technologies are invaluable for tracking three key aspects of crop performance: productivity – yield (quantity and quality), phenology - development timing, and environmental stress. Modern RS platforms can continuously survey entire fields and regions, detecting plant traits and symptoms that are often invisible to the human eye [

12]. This enables an accurate, early, and spatially detailed view of crop status, supporting timely management interventions.

However, studies in the literature using RS for agriculture tend to focus on either yield estimation, phenology mapping, or stress detection and assessment, without combining these aspects into a unified framework for proactive resilience. This means we often gain deep insights into one component yet lack a holistic understanding of how to jointly optimize productivity, timing, and tolerance in cropping systems. In addition, a recent comprehensive review of optical remote sensing for crop stress noted that most studies relied on single-sensor data and single-indicator stress proxies, rather than exploiting multi-sensor, multi-factor synergies [

13]. In that review, most of the research designs were constrained by available sensors and tended to examine one stress factor at a time [

13]. The authors identified a clear path forward: integrating data across multiple sensors and spectral domains to monitor multiple stress responses simultaneously (a more holistic view) and assimilating those observations into crop models [

13]. This points to a gap in current research—the need for integration. Similarly, while yield prediction studies and phenology studies exist separately, combining phenological metrics with yield models has proven beneficial yet is not universally practiced. Few studies explicitly link shifts in crop phenology due to climate stress with consequent yield outcomes and stress mitigation strategies [

14].

In the context of resilience, this gap is even more pronounced. Resilience, by definition, spans multiple dimensions (stable yields, adaptive phenology, and stress resistance), but many investigations tackle these components independently. A farm-systems resilience review found that assessments often examine only a subset of performance metrics (e.g. economic yield or average productivity) and ignore others like temporal variability or environmental factors [

10]. Therefore, there is a recognized need for integrating crop productivity, phenology, and stress monitoring approaches into a single framework—especially using remote sensing—as a non-destructive and cost-effective enabler. Without such integration, we risk missing important interactions, such as how phenological shifts might buffer yield losses under drought, or how early stress detection might save a season if coupled with adaptive management [

3].

While most reviews on remote sensing applications have either summarized existing sensor platforms [

13] or explained how spectral bands correspond to vegetation physiology [

12], this review narrows the scope and instead synthesizes methodologies and recent advances in applying remote sensing to enhance resilience in broadacre cropping systems. Specifically, the review addresses three principal themes: 1) crop productivity monitoring (production and yield gaps estimation); 2) crop phenology monitoring and modeling (growth stages and development shifts); and 3) crop stress detection and assessment (abiotic and biotic stress). By integrating insights across these domains, this review highlights how RS technologies are evolving from monitoring tools toward comprehensive decision-support systems that can inform adaptive management and strengthen resilience under climate change. This paper is structured to first review thematic advances and limitations in RS applications, then examine integration trends and challenges toward resilience, and finally outline future directions.

2. Materials and Methods

To ensure comprehensive yet focused coverage of relevant research, a semi-structured literature search strategy was employed (

Table 1). Google Scholar served as the primary search engine, with the Web of Science and Scopus considered for cross-referencing, to capture studies spanning multi-disciplinary agriculture, including remote sensing, agronomy, and climate adaptation.

Keyword combinations were designed to align with the principal themes of this review. Searches were conducted using Boolean operators (AND, OR) with combinations such as: “remote sensing” AND [“crop produc*” OR “yield”], “remote sensing” AND “crop phenology”, [“remote sensing” OR “UAV”] AND “crop stress”, and “remote sensing” AND “resilience”.

This inclusive search approach aimed to accommodate terminology differences across disciplines and to capture studies addressing the intersection of remote sensing applications and agricultural resilience.

Following the initial search, studies were screened based on title and abstract review to identify potential relevance, with full-text assessments conducted where necessary.

The inclusion criteria focused on peer-reviewed journal articles reporting the application of remote sensing techniques to broadacre cropping systems, addressing at least one of the principal themes—crop productivity estimation, phenological monitoring, or environmental stress detection—and demonstrating clear agronomic relevance. Studies were excluded if they focused solely on non-cropping systems, were purely methodological without direct agricultural application, or were not peer-reviewed.

Following title and abstract screening, full-text evaluation, and the application of defined inclusion criteria, a final dataset of 66 peer-reviewed articles was assembled.

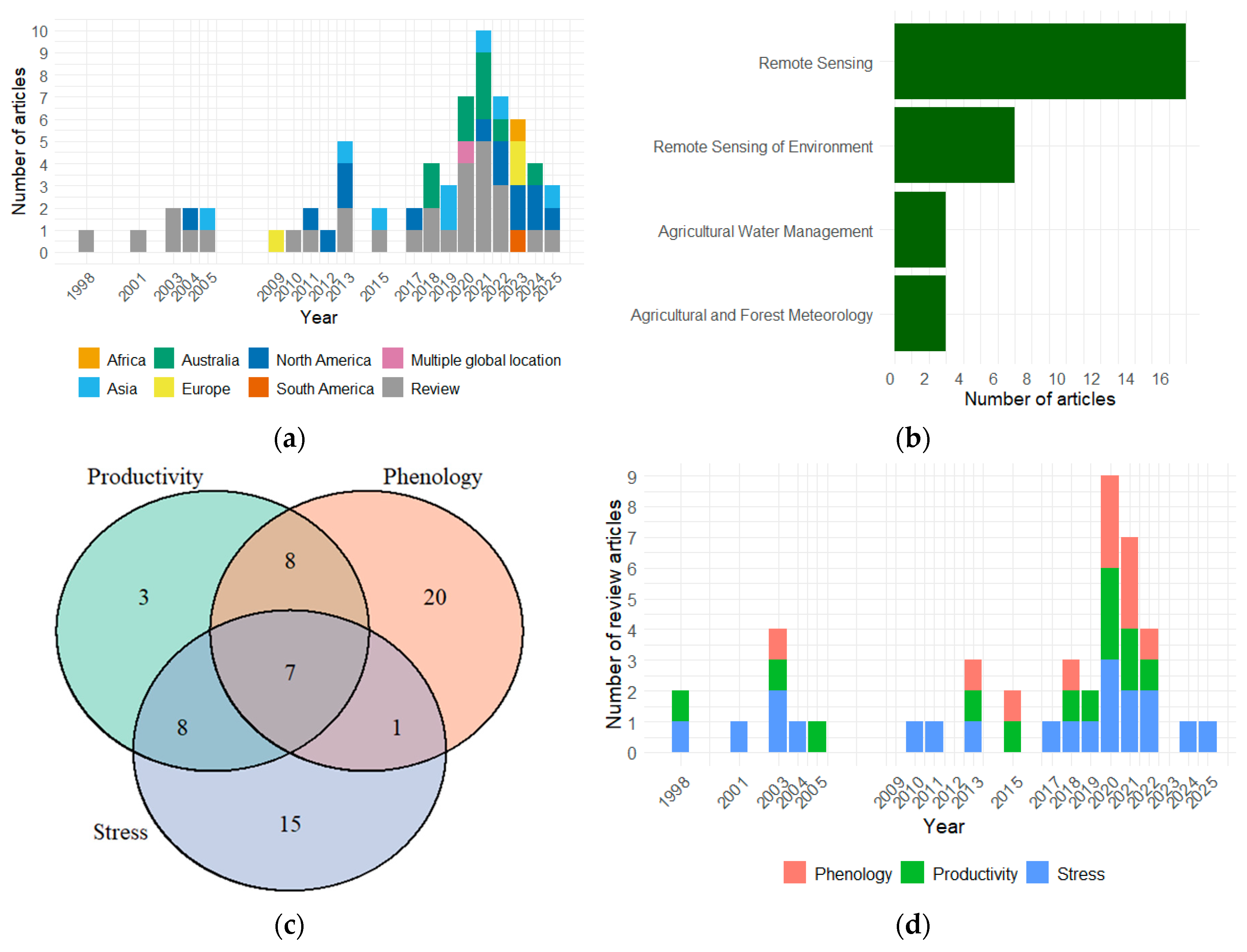

Figure 1 presents a bibliometric overview of these studies.

Figure 1a shows the count of articles by year and geographic focus, with review-type articles—those not tied to specific regions—displayed in gray. Geographically, the studies span a wide range of production zones, with notable contributions from the United States (e.g., Midwest), Australia (e.g., Wheatbelt), Asia (e.g., China and South Asia), and Europe (e.g., Danube River Basin and Italy). This global distribution enhances the applicability of the findings and underscores the need for integrated research approaches across regions and disciplines. The majority of publications appeared between 2018 and 2024, reflecting growing interest in applying remote sensing to crop monitoring. The selected articles span 22 journals, with

Remote Sensing, the

Remote Sensing of Environment,

Agricultural Water Management and

Agricultural and Forest Meteorology among the most represented (

Figure 1b). Thematic coverage shows an emphasis on productivity (n = 26), phenology (n = 36), and stress detection (n = 31), though few studies (n = 7) addressed all three simultaneously (

Figure 1c). A total of 28 review-type articles were included, many of which concentrated on single or double themes (

Figure 1d). In addition, four studies in the dataset did not fall neatly into the three principal themes of productivity, phenology, or stress, but instead focused on broader methodological innovations and cross-cutting applications of remote sensing in agriculture. The following sections synthesize key developments across each thematic focus area.

The list of selected articles is provided in the

Supplementary Materials. Bibliometric analyses were conducted in R [

15,

16] using the ‘

ggplot2’ [

17] and ‘

VennDiagram’ [

18] packages. ChatGPT (model GPT-4o) [

19] was used to assist with the initial structure of the manuscript and for grammar checking during later stages.

3. Thematic Review

This section reviews the development of remote sensing methods for 1) crop productivity monitoring, 2) crop phenology monitoring and modelling, and 3) crop stress detection and assessment, highlighting common methodologies, crop- or region- specific findings, and how these advances and remaining challenges to inform resilience-focused agricultural monitoring. A case study from the authors’ ongoing projects is provided to support the discussion.

3.1. Remote Sensing for Crop Productivity Monitoring

Over the past few decades, research has evolved from simple empirical relationships between satellite indices and yield towards integrated approaches that combine multi-spectral imagery, crop phenology, weather data, and modeling frameworks.

3.1.1. Foundational Developments in Remote Sensing for Crop Productivity

In the 1990s, precision agriculture concepts emerged, integrating remote sensing with GPS and GIS to map within-field variability and guide inputs [

20]. By the early 2000s, studies had established empirical yield models based on satellite-derived indices and thermal imagery [

21]. For example, reflectance-based vegetation indices (such as the NDVI) and thermal-based estimates of crop water use were identified as two distinct approaches for predicting yields and detecting stress [

21]. Concurrently, remote sensing was being incorporated into agricultural statistics for large-scale crop area and yield estimation, improving the design of survey sampling frames and accuracy of national yield forecasts [

22]. These foundational efforts confirmed that spectral measurements from aircraft or satellites can capture crop health and biomass signals correlated with final yields, setting the stage for more advanced techniques [

23].

3.1.2. Vegetation Indices and Phenological Metrics for Yield Estimation

A core method in the remote sensing of productivity is the use of vegetation indices (VIs) as proxies for crop health and yield. Decades of research show that metrics such as the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) [

24] or Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) [

25] correlate strongly with final yields in many crops, enabling pre-harvest yield forecasting [

26,

27]. In practice, simple models using seasonal NDVI or EVI metrics can capture a large fraction of yield variability (often with R

2 in the 0.6–0.7 range), although the most predictive index may depend on environmental context. For example, an EVI-based metric achieved an R

2 of approximately 0.67 for maize yield prediction in humid regions of the U.S., whereas a water-sensitive index (NDWI) performed better in semiarid areas (R

2 = 0.69) [

27].

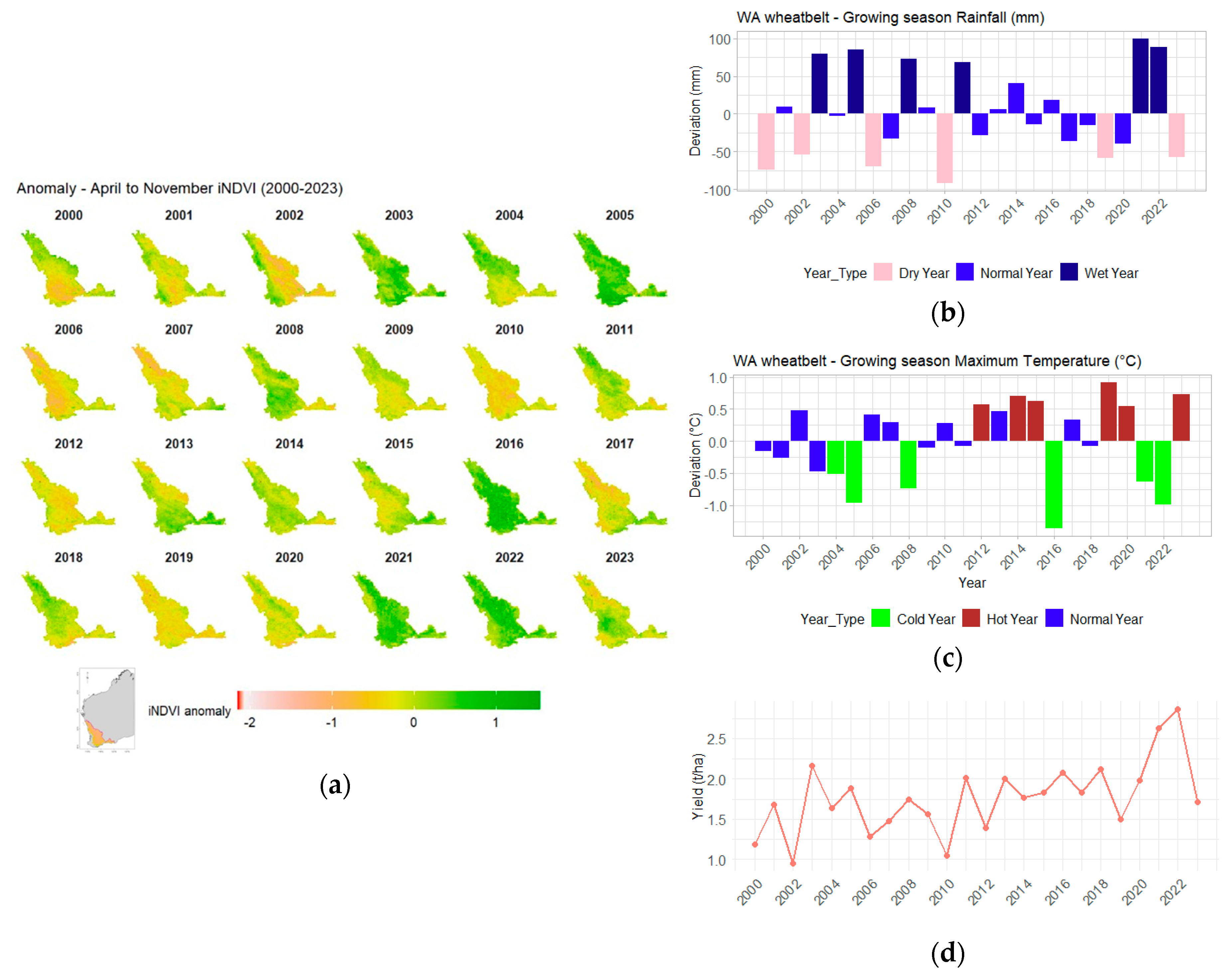

Figure 2 demonstrates the use of MODIS NDVI monthly composites (MOD13C2, ~500 m resolution) from 2000 to 2023 to track wheat productivity across the Western Australian (WA) rainfed wheatbelt (from the authors ongoing study). This multi-year integrated NDVI (iNDVI) record enables the retrospective assessment of landscape-scale yield variability, revealing the spatiotemporal patterns of crop productivity in response to poor seasons over two decades. Positive values in the iNDVI anomalies (green color) correspond to known high-yield years with favorable growing season rainfall and a mild range of temperatures, whereas negative iNDVI anomaly values (orange/red colors) denote severe drought seasons that depressed wheat yields (

Figure 2). Such alignment between the NDVI-based productivity maps and historical climate anomalies or statewide yield records highlights the value of remote sensing for capturing climate-driven yield fluctuations. A case study examined within-field variation in the WA wheatbelt using Landsat NDVI sequences and showed that seasonal NDVI time-series metrics can explain much of the inter-annual wheat yield variation (R

2 ~0.64) [

28]. Likewise, a further study successfully hindcasted past wheat yields for 44 WA paddocks using archival satellite data (R

2 ~0.68) [

29], underscoring the utility of retrospective remote-sensing analysis for agronomic insights.

However,

Figure 2 also illustrates key limitations of NDVI-based monitoring. First, the complete seasonal NDVI composite becomes available only after crop harvest, limiting its usefulness for in-season yield forecasting or early drought warning. In other words, detailed phenological curves and productivity metrics can only be confirmed post-season, an approach often termed retrospective or hindcasting, rather than being amenable to near-real-time prediction [

30]. A second limitation is the impact of cloud cover on optical NDVI observations. In some growing seasons, heavy or persistent cloud cover leads to data gaps or noisy composites; this cloud contamination disrupts the continuity of the NDVI time series, complicating year-to-year comparisons and trend analysis [

28]. Studies in the WA wheatbelt have noted that missing NDVI data due to clouds are “unavoidable” and must be handled carefully [

28]. Recent approaches attempt to mitigate this issue by gap-filling or blending data from multiple sensors—for instance, applying spatially weighted interpolation to fill Landsat NDVI gaps in WA croplands [

31].

3.1.3. Integrating Remote Sensing with Climate and Crop Models

While VIs alone capture general productivity trends, they often cannot fully account for factors such as weather extremes, soil conditions, and management practices that affect yield. To address this, researchers have increasingly integrated remote sensing data with climate information and process-based crop models. By combining these data sources, models can distinguish weather-driven yield fluctuations from the crop’s spectral signals. For example, one study used satellite thermal infrared imagery to infer root-zone soil moisture via an energy balance model and fed that output into a crop simulation model (DSSAT) for rain-fed maize fields [

32]. This integration of remotely sensed drought stress enabled accurate yield estimates in regions with sparse rain gauges by capturing moisture deficits that vegetation indices alone might miss [

32]. In another case, scientists in South Asia assimilated satellite observations into the DSSAT model to constrain the leaf area index (LAI) and biomass, greatly improving the representation of crop growth in data-sparse farming areas [

33]. Such approaches are especially valuable under compound climate extremes. In the Danube River Basin, a novel copula-based framework was used to analyze maize yield losses due to back-to-back drought years using a suite of remote sensing indices including the two-band enhanced vegetation index (EVI2), evaporative stress index (ESI), and relative soil water availability [

34]. That study underscored the disproportionate impact of consecutive droughts on productivity, especially in countries like Romania, Bulgaria, and Slovakia.

High-resolution remote sensing has likewise been employed to improve yield predictions under variable climate conditions. In northeastern Australia, for instance, assimilating Sentinel-2 data (eight different spectral indices) into a field-scale wheat model significantly enhanced yield prediction accuracy. Single spectral metrics alone explained over 70% of the yield variability (for example, a red-edge chlorophyll index achieved an R

2 of 0.76 with observed yields), and combining those indices with a modeled water stress factor increased the R

2 to about 0.91 in training (and ~0.93 upon independent validation) [

35].

Integration approaches are also being used to attribute yield losses to specific extreme weather events in near-real time. For instance, a recent study in South Australia paired high-frequency Sentinel-2 VI time series with concurrent weather data to detect and quantify crop damage from heatwaves and drought. The researchers developed a “crop damage index” (CDI) based on the deviations of observed greenness from expected phenological trends, which allowed the mapping of yield losses at sub-field resolution as the season progressed [

14]. The CDI showed a high correlation with actual yield outcomes (R2 ~0.83 for wheat and ~0.91 for barley), enabling the early identification of areas suffering weather-induced yield deficits [

14]. Overall, blending satellite observations with meteorological and agronomic data produces more robust yield estimates and diagnostic insights than any single data source on its own [

32,

36].

3.1.4. Precision Agriculture and Yield Gaps Estimation

Remote sensing technologies have become indispensable tools for advancing precision agriculture, particularly in large-scale broadacre systems where within-field variability can significantly influence productivity.

In Australia, long-term Landsat NDVI time series have been employed to characterize persistent yield zones across broadacre cropping landscapes [

28]. These records reveal stable patterns of productivity over time, allowing the identification of consistently low- or high-yielding patches. For example, integrating multi-season NDVI-based metrics achieved correlations of up to r = 0.8 with observed wheat yields (with RMSEs in the range of 0.5–0.6 t/ha) [

28]. This information enables growers to pinpoint underperforming areas and tailor management interventions, such as adjusting fertilizer or seeding rates, to address localized constraints. A large-scale application of this approach was recently demonstrated across 20 million hectares in WA’s wheatbelt, where satellite-derived crop rotation histories were combined with the agricultural production systems simulator (APSIM) crop modeling and machine learning to quantify the benefits of different rotations on wheat yield [

37]. The results challenge conventional assumptions from field trials and highlight how landscape-level management insights can be derived from remote sensing–model fusion.

In the context of increasing climatic uncertainty, one of the most critical applications of remote sensing is in evaluating yield gaps and monitoring resilience. Yield gaps—defined as the difference between actual and attainable yields under optimal conditions —are pervasive across both high- and low-input systems [

38,

39]. Satellite-derived VIs offer a scalable method for assessing these gaps across large spatial extents, especially where ground data are sparse [

39]. In smallholder systems, for example, the remote sensing of crop phenology has been proposed as a promising approach for identifying chronically underperforming fields by capturing intra-seasonal variability in crop development stages. However, spatial mismatches between satellite-derived phenology and the fine-scale yield variability in smallholder landscapes remain a key limitation [

40]. This underscores the need for higher-resolution data and data fusion techniques to enable the practical application of phenology-based yield gap detection at smallholder scales [

40].

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have enhanced the spatial resolution of crop monitoring, offering centimetre-level imagery on demand [

41,

42]. Equipped with multispectral or thermal sensors, UAVs can detect subtle early indicators of stress—ranging from nutrient deficiencies to pest and disease outbreaks—often before visual symptoms emerge [

41,

43]. This early detection capability supports targeted interventions, potentially reducing yield losses and minimizing input waste. While operational limitations remain, the utility of UAVs has been demonstrated in research contexts [

41]. Looking forward, emerging frameworks, described as “Agriculture 5.0” envision the integration of satellite and UAV data with internet of things (IoT) sensor networks, automated machinery, and AI-driven decision support systems that can provide growers with dynamic tools for adaptive management [

44,

45].

In regions vulnerable to food insecurity, such as South Asia, operational drought monitoring systems now incorporate remote sensing-based indices such as ESI and Vegetation Health Index (VHI), offering early indicators of drought onset and duration [

46]. These tools enable more proactive responses to agricultural stress and contribute to regional food security efforts.

3.2. Remote Sensing for Crop Phenology Monitoring and Modeling

Crop phenology—the timing of developmental stages such as emergence, flowering, and maturity—is a critical indicator of crop performance and adaptation. Accurate phenological information aids yield forecasting, crop management, and climate adaptation assessments. Remote sensing offers a practical means for monitoring phenology over large areas, complementing or replacing sparse ground observations. This section reviews recent advances in remote sensing–based methods for extracting, integrating, and evaluating crop phenology information for broadacre agriculture.

3.2.1. Crop Phenology Information from Remote Sensing

Early satellite-based attempts in the 2000s demonstrated that time-series VIs (like the NDVI) can be used to infer key phenological transition dates (e.g. planting or harvest) at regional scales [

47,

48]. In fact, the potential of remote sensing for tracking crop phenology in precision agriculture was already recognized in early reviews [

49]. Subsequent research has greatly improved the precision of phenology retrievals by refining algorithms, leveraging new sensors, and integrating ancillary data. Notably, numerous recent reviews highlighted the rapid advances in remote-sensing phenology and their importance for sustainable agricultural practices [

23,

42,

44,

45,

50]. The methods for extracting crop phenology information from remote sensing data include the following:

Threshold-based approaches—Simple rules (e.g., NDVI exceeding a fixed threshold value) to mark start or end of season [

47,

48]. These methods are straightforward but may require calibration and can be sensitive to noise.

Curve fitting and smoothing—Fitting functions (e.g., logistic, spline, or sigmoid models) to VI time-series to identify inflection points corresponding to phenological events [

51,

52]. For instance, double-sigmoid fits to Sentinel-2 NDVI have been used to detect crop green-up and senescence, aligning well with field observations [

51]. Similarly, wavelet transforms and harmonic analysis have been applied to MODIS time-series to smooth out noise and better capture seasonality [

52,

53].

Time-series derivatives—Computing the first or second derivative of smoothed VI curves to pinpoint the dates of rapid change. This technique was shown to improve the detection of sowing and harvest dates in soybean when compared across algorithms. It was stated that smoothing-based methods (e.g., TIMESAT, phenex) yielded lower timing errors than simple derivative or threshold methods [

54]. Open-source toolkits now facilitate such analyses: for example, the CropPhenology R package can calculate ~15 phenological metrics (such as the start of season and end of season) from NDVI time-series [

55].

Multi-sensor data fusion—Combining observations from multiple satellites to achieve high revisit frequency and all-weather monitoring. For example, blending optical and radar data has helped overcome cloud-related gaps: a recent framework fused Sentinel-1 SAR with Sentinel-2 optical imagery to track wheat phenology, improving agreement with ground camera (PhenoCam) observations of growth stages [

56]. Likewise, merging Landsat and Sentinel-2 in a harmonized time-series enables within-season phenology mapping rather than only post-season analysis [

30]. Additionally, Zhao, et al. [

56] demonstrated a deep learning approach to fuse Sentinel-1 and -2 time-series, which further improved the accuracy of detecting the crop season start and end by leveraging spatial–temporal features. Emerging data sources are also being explored. For instance, satellite solar-induced fluorescence (SIF) measurements combined with the NDVI have been used to monitor cropland photosynthetic phenology, capturing seasonal peaks and early stress signals in rainfed crops [

57]. One study in WA filled cloud gaps in Landsat NDVI sequences via spatial interpolation, reduced the reconstruction error by ~75% [

31].

High-resolution and proximal sensing—Utilizing fine-scale imagery and ground-based sensors to refine satellite phenology estimates. Near-surface digital cameras (PhenoCams) and drone imagery have been used to validate and calibrate satellite-derived phenology [

58]. For instance, PlanetScope cubesat data (3–5 m resolution) in combination with PhenoCam observations allowed the detection of crop canopy cover change and senescence with high temporal detail [

58]. Even low-cost tools like smartphone cameras have been tested: in India, plot-level wheat phenology (e.g., dates of canopy closure and heading) was captured using RGB images, offering an inexpensive alternative for smallholder farms [

59].

Machine learning and hybrid models—Advanced algorithms that learn phenological patterns from multi-source data. Recurrent neural networks (long short-term memory method) guided by crop growth model outputs have enabled near-real-time phenology estimates that assimilate weather, soil, and MODIS satellite data [

60]. These hybrid approaches can predict phenological stages on a daily basis, which is a leap beyond traditional end-of-season phenology metrics. Additionally, machine-learning models using remotely sensed pheno-metrics have been applied to related tasks like early yield forecasting. In one case, an XGBoost model using MODIS-derived phenology indicators could predict U.S. corn yields as early as the mid-season growth stage with only slight loss of accuracy compared to using detailed ground-observed stages [

61]. More broadly, the fusion of satellite observations, machine learning, and crop modeling is expected to further enhance phenology prediction and crop classification in operational farming systems [

62].

Remote sensing-based phenology monitoring has now been demonstrated across diverse cropping systems and regions (

Table 2). Studies have mapped crop calendars in complex smallholder landscapes [

40], identified cropping pattern shifts [

53], and tracked long-term phenology trends under climate variability [

63]. Notably, satellite phenology metrics have been used to diagnose yield gaps [

39] (also mentioned in section 3.1.4): for example, reviews concluded that aligning planting dates with optimal climate windows (as inferred from phenology maps) could help close yield gaps, though caution is needed in heterogeneous smallholder fields [

34,

40]. Similarly, phenological shifts detected via remote sensing offer insight into climate change impacts. In Australia, variations in NDVI green-up and senescence timing have been linked to temperature and rainfall anomalies, revealing stage-specific climate sensitivities of winter crops [

63]. In a similar framework, Duan, et al. [

14] showed that integrating satellite phenology with weather data can detect and attribute cereal yield losses to specific drought and heat events, illustrating how phenological deviations reflect the impact of climate extremes. This highlights phenology as a key resilience indicator—crops that maintain or adjust their development timing under stress tend to perform better.

3.2.2. Integrating Phenology with Crop Growth Models

Another important integration is of phenology information into crop growth models and decision support tools. By assimilating remote sensing-derived phenological dates or leaf area dynamics, crop models can be continually adjusted to real field conditions. For example, satellite-observed LAI and biomass were fed into the DSSAT crop model for maize, markedly improving the simulation of crop development and yield under drought stress [

33]. The fused model achieved high agreement with field measurements (LAI R

2 ~0.85 and biomass R

2 ~0.95), illustrating the value of using phenology-sensitive RS inputs to constrain model predictions [

33]. Such approaches enable early in-season yield forecasts and proactive management. Indeed, phenology-driven yield forecasting has progressed to the point that by mid-season, one can predict final yields with reasonable confidence if key growth milestones (e.g., flowering time) have been remotely sensed [

61]. Studies integrating satellite phenology metrics into yield models consistently report improved accuracy: for instance, adjusting NDVI time-series based on each pixel’s observed green-up date significantly enhanced corn yield predictions in the U.S. Corn Belt [

26]. Case studies in Australia [

28,

29] of using phenological patterns to explain historical yield anomalies have been discussed in section 3.1.2.

3.2.3. Challenges for Remote Phenology Monitoring

Despite these advances, challenges remain in remote phenology monitoring. Dense time-series data are required to pinpoint short growth stages, yet frequent cloud cover or coarse revisit intervals can obscure critical transitions [

51]. For example, using a 16-day satellite revisit interval instead of daily observations can introduce errors on the order of 10 days in detected phenology dates [

65]. As noted earlier, missing observations in optical datasets can be interpolated or supplemented with radar to avoid bias [

31]. Moreover, inconsistencies in defining phenological turning points (e.g., what NDVI level constitutes “onset of greenness”) can lead to inter-study variation [

66]. Double cropping is an added challenge [

54], as overlapping growth cycles complicate the separation of distinct phenological phases within a single season. Wu, et al. [

11] similarly emphasize that multi-cropping systems and fine-scale field heterogeneity still pose substantial uncertainties for the remote sensing of phenology, even as new sensor fusion techniques begin to mitigate these issues. Standardizing phenology definitions and validation with ground truth (phenology networks, cameras, and field observations) is essential for comparing results.

Nevertheless, the overall trajectory is positive—with multi-sensor networks (satellites, UAVs, and in situ sensors) and improved algorithms, remote sensing is providing ever more reliable crop phenology information. This lays a foundation for resilience-building strategies, because phenological adaptation (the ability to adjust timing) is a major mechanism by which crops avoid damage from heat or drought. In the next section, we turn to remote sensing of the stresses themselves, and how early warnings can be derived before phenological or yield impacts fully manifest.

3.3. Remote Sensing for Crop Stress Detection and Assessment

Crop stress, whether due to environmental extremes or biological factors, has been a major focus of agricultural remote sensing research. Early work recognized that multispectral imagery and thermal infrared measurements could reveal crop health issues like moisture deficits and pest outbreaks before yield losses occurred [

20]. Over the past two decades, a wide range of approaches have been developed to remotely assess crop stress at scales from individual plants (using drones or proximal sensors) to entire regions (via satellites) [

13,

49]. Notably, several comprehensive reviews highlight these advances in remote sensing for crop stress detection and assessment [

23,

39,

42]. The choice of technique and its effectiveness depend on the stress type and the spatio-temporal scale of analysis [

67]. Below, we review how remote sensing is being used for abiotic stress detection (focusing on drought and heat) and biotic stress detection (pests, diseases, and weeds), highlighting key examples, methods and results from refined studies.

3.3.1. Drought and Water Stress

Drought and water accessibility are among the stresses most detrimental to crop production [

46], especially in broadacre farming systems. Remote sensing has been extensively used to detect plant water stress [

68], including high-resolution UAV surveys for the early detection of water deficits [

69]. A common approach is to track VI anomalies and moisture-sensitive indices from optical satellite data [

46,

70]. For example, normalized difference indices derived from MODIS and Landsat (NDVI, NDWI, and NDMI) have been used to assess vegetation health and soil moisture status in croplands [

70]. Declines in NDVI-based metrics often signal emerging water stress (as shown in

Figure 2), and composite indices such as the Vegetation Condition Index (VCI) integrate the current NDVI with historical ranges to gauge drought severity [

70]. At regional scales, drought indices that combine satellite rainfall and land surface temperature (LST) can capture broad agricultural drought events [

71]. Ali, et al. [

71] characterized spatio-temporal drought patterns across South Asia (2001-2017) using the Temperature-Vegetation Dryness Index (TVDI) from MODIS thermal and vegetation data alongside a satellite-based Drought Severity Index (DSI). They found that these indices successfully mapped major drought episodes, with a modified water supply index performing best in certain seasons [

71]. Similarly, Shahzaman, et al. [

46] evaluated multiple MODIS-derived drought indices in South Asian croplands and identified the Evaporative Stress Index (ESI) as a particularly effective early indicator of agricultural drought [

46]. These remote indicators have become part of operational drought monitoring systems, providing early warning of crop water stress and impending yield losses [

43,

46].

At the field scale, high-resolution imagery allows more nuanced assessment of crop water status. Sentinel-2 satellites (10-20 m resolution) in particular have enhanced stress monitoring at farm scales [

72]. Beyond passive optical imagery, thermal infrared sensing is a powerful tool for detecting water stress via canopy temperature. Stressed plants under soil moisture deficits exhibit elevated leaf temperatures due to reduced evaporative cooling. Ground-based studies in irrigated maize fields showed that canopy temperature-derived indices closely track crop water status [

36]. Kullberg, et al. [

36] evaluated thermal infrared indices (e.g., Degrees Above Non-Stressed, DANS) using stationary IR thermometers in Colorado corn and found that they could reliably estimate crop evapotranspiration (ET) coefficients, enabling real-time irrigation scheduling [

36]. Gu, et al. [

73] used UAV thermal imagery to compute the CWSI—which compare canopy and air temperature—in cotton trials, distinguishing drought-tolerant cultivars by their lower canopy temperatures under stress [

73]. Such applications illustrate the value of remote sensing for plant breeding and management, identifying genotypes or field zones that withstand water stress.

Multi-sensor approaches and modeling can further improve drought assessment. Remotely sensed ET models combined with crop growth simulations have been used to infer root-zone moisture and yield impacts. Mishra, et al. [

32] developed a stress estimation tool that fuses satellite-derived ET (using the ALEXI thermal model) with DSSAT crop model to map soil moisture stress and predict yields (discussed in section 3.1.3) in North Alabama [

32]. Likewise, Zhao, et al. [

35] showed that assimilating multi-spectral Sentinel-2 indices into a wheat crop model improved field-scale yield prediction in Australia, implicitly capturing the effects of in-season water stress [

35]. Another novel strategy is to use statistical frameworks to link stress indicators with yield losses. Potopová, et al. [

74] combined multiple remote indices—including the two-band enhanced vegetation index (EVI2), the evaporative stress index (ESI from thermal/ET data), and relative soil water availability—in a copula modelling approach to quantify maize yield loss probabilities under drought in the Danube basin [

74]. By integrating these indicators, they could probabilistically estimate drought-induced yield reductions, offering a risk assessment tool for climate extremes [

74].

Table 3 summarizes case studies of remote sensing techniques used to detect water stress and drought impacts in crops.

Importantly, remote sensing can detect not only pure drought stress but also compound and related stresses. Salinity stress, for example, often co-occurs with water deficits and produces similar spectral symptoms (e.g., reduced canopy moisture and greenness). Using satellite indicators, Wen, et al. [

75] evaluated crop responses under combined salinity and drought stress in the U.S. Their analysis of Sentinel-2 derived biophysical variables (LAI, fractional cover, canopy water and chlorophyll content) revealed that crops experienced far greater impacts under combined salinity-drought stress than under either stress alone [

75]. Notably, leaf area declined earlier and more severely when both stresses were present, indicating a compounding effect [

75]. This highlights that remote sensing metrics can sensitively capture the exacerbated plant responses to multiple simultaneous stressors. In general, water-related stresses (drought and, salinity) tend to manifest clearly in remote measurements—plants under water stress exhibit lower reflectance in NIR and often higher thermal emission—making them relatively well-monitored via current satellites [21, 76]. Nonetheless, accurately estimating available soil moisture from space remains challenging. Research into microwave and thermal-infrared techniques for direct soil moisture retrieval continues [

77], as does research for the better integration of optical drought indices with hydrological models to improve crop stress forecasts.

3.3.2. Heat and Thermal Stress

Extreme heat events can stress crops independently of soil moisture, accelerating development, impairing pollination, and shortening grain fill. Detecting heat stress via remote sensing is less straightforward, as many spectral changes (leaf wilting and premature senescence) overlap with drought signals. A promising approach is to incorporate meteorological data (temperature records or thermal time) alongside vegetation indices to isolate heat impacts. Duan, et al. [

14] pre[21,76sented a novel yield-loss detection method using Sentinel-2 time series in South Australian cereal crops, where they introduced a thermal time (growing degree day) dimension to the vegetation index analysis [

14]. By comparing expected and observed EVI2 trajectories on a thermal time axis, they could attribute yield reductions to either moisture stress or heat stress anomalies.

Meanwhile, the use of thermal remote sensing in agriculture has predominantly targeted plant water status, given the tight coupling between heat and transpiration. Comprehensive reviews of thermal imaging applications in precision agriculture note that canopy temperature mapping is invaluable for early stress detection and irrigation management [

11,

78]. Khanal, et al. [

78], for example, surveyed current and potential uses of thermal sensors and highlighted their effectiveness in spotting water deficits before visible symptoms occur. As discussed above, thermal indices can serve as proxies for crop stress, but they generally signal a physiological response (stomatal closure) that could result from either drought or acute heat. One emerging indicator that responds to both water and heat stress is solar-induced fluorescence (SIF). SIF is an optical radiation (peaks near 685 nm and 740 nm) emitted by chlorophyll during photosynthesis: it tends to drop sharply when photosynthesis is inhibited by stress. A recent study reviewed UAV-based SIF sensing for crop water stress detection [

79], noting that fluorescence signals are highly sensitive to the onset of stress [

79]. Because heat and drought both constrain photosynthesis, SIF measurements (often combined with traditional reflectance indices) are being explored to flag heat-stressed crops that may still appear green but have reduced carbon uptake. Going forward, an integration of thermal imagery (for canopy temperature) with optical and fluorescence data could provide a more specific diagnosis of heat stress versus water stress in crops [

13]. This multi-sensor strategy is expected to improve the discrimination of stress causes—for instance, separating a heatwave’s impact from a soil moisture deficit—which is critical for guiding the appropriate management response.

3.3.3. Biotic Stress

Biotic stresses from pathogens, insect pests, and weeds also leave signatures that remote sensing can exploit. Stressed crops often exhibit localized discoloration, defoliation, or growth suppression that can be detected with high-resolution spectral imagery. Weed infestations were among the earliest targets of remote sensing in precision agriculture [

80]. In fact, Lamb and Brown [

80], over twenty years ago, demonstrated that mapping weed patches via aerial multispectral imagery could guide site-specific herbicide applications in Australian fields. Subsequent work expanded on weed detection algorithms: Thorp and Tian [

81] reviewed techniques for distinguishing weeds from crops using spectral and textural features, laying a foundation for automated weed mapping. Today, UAVs equipped with multispectral or hyperspectral cameras can generate detailed weed distribution maps at sub-meter resolution, enabling real-time intervention [

43].

Plant diseases and insect attacks can be more subtle, but they too induce physiological changes observable from above. Foliar diseases often reduce chlorophyll content in infected areas, causing spectral reflectance changes (e.g., higher red reflectance and lower NIR) similar to nutrient deficiencies [

13]. Pest damage (e.g., defoliation or sap sucking) can create patchy canopy thinning or premature senescence, again altering vegetation index values. Critically, these biotic stress signals might be confused with other stresses if only a single sensor is used. However, research shows that multi-temporal and multi-spectral observations can improve detection. For instance, UAV surveys have caught early-stage disease outbreaks by detecting abnormal temporal trends in crop greenness before widespread symptoms appear [

41]. Thermal imaging can also aid disease scouting: infected plants often have warmer canopies due to reduced transpiration, a phenomenon that a remote thermal camera can pick up in precision agriculture trials [

13]. Hunt Jr and Daughtry [

43] emphasize that UAVs add significant value here: by flying low and slow, they can capture fine-grained variability in crop temperature and color, helping to spot incipient pest or disease foci that satellites might overlook. In practice, this means that an integrated approach (combining optical, thermal, and perhaps even fluorescence sensors on UAVs) can provide an early warning of biotic stress. As an example of integration, Maes and Steppe [

41] outline how drone-based hyperspectral imaging, in combine with machine learning, has identified nutrient deficiencies and pathogen-infected plants in experimental settings. Overall, while biotic stress detection via remote sensing is inherently complex, the literature shows steady progress. Comprehensive frameworks now exist that catalog spectral disease markers and recommend sensor combinations for improved pest/disease monitoring [

13,

34]. These advances point toward an increasingly proactive use of remote sensing in crop protection.

Across the literature, remote sensing has proven to be a versatile means of assessing crop stress from the leaf to regional scale. Optical vegetation indices, thermal measurements, and even advanced fluorescence and radar techniques each capture different facets of plant stress responses [

13]. Still, a clear message from recent studies is that no single sensor or index can unravel the full complexity of stress physiology. Most practical scenarios involve multiple concurrent stressors—drought, heat, and biotic attacks overlapping—which can confound spectral signals [

13,

14]. This has spurred a shift toward multi-sensor data fusion and integrative analysis. As noted in a comprehensive review by Berger, et al. [

13], combining data across the visible, infrared, and thermal domains (and at multiple time points) greatly improves the ability to detect and differentiate stress factors. Likewise, multi-factor modeling approaches are emerging to attribute crop losses to specific stress events [

14] or to capture interactions (like salinity exacerbating drought) [

75].

However, challenges remain in scaling these methods from experimental studies to operational farm management [

11]. Limitations, such as data volume, processing complexity, and the need for ground calibration still hinder the wide adoption of real-time stress monitoring.

4. Toward Resilience-Based Remote Sensing Applications

Remote sensing enables spatially explicit yield estimation at scales ranging from paddocks to entire regions. Vegetation indices (e.g., NDVI and EVI) and phenology-adjusted metrics provide strong correlations with yield outcomes [

34,

39]. RS-derived productivity maps help to assess yield gaps and optimize input use. However, productivity estimates remain indirect, sensitive to confounding factors such as soil background and climate variability [

23]. While climate drivers are often well quantified, the spatial heterogeneity of soil properties—such as texture, organic matter, and fertility—also strongly influences remotely sensed productivity signals but remains underrepresented in most studies. Furthermore, the accuracy of productivity monitoring continues to be limited by the availability of timely, cloud-free imagery.

Phenological monitoring through time-series imagery captures growth transitions such as green-up, flowering, and senescence, critical for forecasting and management [

38,

62,

73]. Advances in curve fitting, multi-sensor fusion, and machine learning now deliver improved accuracy. However, coarse revisit intervals and cloud contamination introduce errors of ~7–15 days [

75,

82], limiting precise scheduling. Double-cropping systems further complicate interpretation [

54].

RS allows the early detection of abiotic stress (drought, salinity, and heat) and biotic pressures (diseases, pest, and weeds) before visible yield loss [

14,

23,

34]. Thermal and multispectral data are especially useful, and indices such as the Evaporative Stress Index (ESI) perform well operationally [

43]. Still, stress signals are often non-specific, making it difficult to distinguish overlapping causes without ancillary data [

36,

78]. Adoption is also constrained by limited validation datasets.

Crop productivity, phenology, and stress metrics are complementary facets of crop performance, and integrating them provides a more holistic view of resilience. Phenological anomalies often foreshadow yield impacts, and early stress detection enables interventions to safeguard yields. Recent literature suggests that combining these perspectives offers a more complete understanding of crop health and stability than analyzing each in isolation [

47]. With climate extremes becoming more frequent and drought-related yield losses increasingly documented [

5,

83], key integration approaches—multi-sensor/scale data fusion, RS-crop model data assimilation, and big data integration—are being developed to bridge the three themes, as summarized in

Table 4.

Multi-sensor/scale data fusion—One key integration pathway is multi-sensor/scale fusion, which merges observations from different platforms or spectral domains to overcome the limitations of a single data source. Different sensors capture unique aspects of crop condition, so fusing their data provides a more robust picture of the system. For example, combining Sentinel-1 radar (which penetrates clouds) with Sentinel-2 optical imagery (rich spectral information) enabled the accurate mapping of crop phenology even in persistently cloudy regions [

56]. Multi-sensor fusion improves temporal coverage and diagnostic power: studies show that blending visible, infrared, and microwave indicators enhances stress detection [

36]. The trade-off is the requirement for advanced fusion algorithms and the challenge of reconciling differing spatial and temporal resolutions, while UAV-based applications are further constrained by costs, logistical demands, regulatory restrictions, and limited scalability across regions [

42,

69].

RS-crop model data assimilation—Rather than treating remote sensing outputs as standalone products, a resilience approach feeds these data into crop growth models to continually adjust simulations to reality. Upon updating model parameters with observed indices (e.g., greenness or leaf area), the model’s predictions become more accurate and responsive to that season’s conditions. For instance, blending high-resolution Sentinel-2 imagery with a wheat model enhanced field-scale yield prediction in Australia compared to either input alone [

35]. At regional scales, integrating remote sensing with climate data and crop models has been used to assess yield gaps and test management scenarios [

37]. The key benefit of model-data assimilation is better prediction: it can provide early warning of potential yield losses and evaluate “what-if” strategies, aiding proactive management. On the downside, these approaches demand careful calibration and significant computing resources, because models must be tuned to local conditions and continuously supplied with quality weather and soil data.

Operational and big data integration— A resilience-based approach also demands that remote sensing insights be translated into actionable intelligence for farmers, agronomists, and policymakers. This is driving the development of operational decision-support systems that integrate multi-source data and deliver user-friendly outputs (such as drought alerts, yield forecasts, or advisories on sowing and irrigation). Under the scope of “Agriculture 5.0” concept [

44], RS is being linked with on-farm sensors and AI analytics to enable smart farming solutions [

86,

87]. For example, object-based image analysis has been used to integrate vegetation indices, textural metrics, and phenology for accurate crop identification and soil management assessments at the field scale [

84]. Similarly, advances in deep learning now allow robust extraction of field boundaries directly from satellite images, reducing the need for manual inputs [

85]. However, these systems are highly data-hungry, risk overfitting without sufficient training and validation datasets, and often require large, curated data streams that are not readily available across all regions. This raise concerns over scalability and generalizability, especially in data-poor farming systems.

In practice, emerging national programs have been established to integrate RS tools for crop monitoring. For example, the group on earth observations global agricultural monitoring (GEOGLAM) initiative (

https://www.cropmonitor.org/) fuse satellite indicators with ground reports to flag emerging crop failures; the Australian Plant Phenomics Network (APPN) (

https://www.plantphenomics.org.au/) integrates controlled-environment, field, and mobile phenotyping platforms across diverse cropping zones, providing data-driven phenotyping to accelerate the development of climate-resilient crops.

Looking ahead, advancing RS for resilience requires moving beyond monitoring individual crop performance themes toward integrated frameworks that define and quantify resilience itself. A key future direction is to develop integrated resilience metrics that remote sensing can quantify—for example, indices of yield stability or the speed of post-stress recovery. These metrics could also incorporate soil-related indicators such as top-soil moisture retention, salinity dynamics, and erosion risk, which strongly influence crop responses to climatic stress [

75] yet remain underrepresented in current remote sensing frameworks. By defining such metrics, we can directly measure how well management interventions or new technologies bolster crop resilience. Decades of satellite archives [

88] (e.g., the Landsat record) make it possible to compute these indicators by analyzing long-term patterns of productivity and recovery under varying conditions.

Another direction is integrating predictive capabilities with remote sensing. This includes coupling climate forecasts with current crop conditions to anticipate stresses before they fully develop, enabling truly proactive responses. For instance, seasonal rainfall forecasts combined with early-season vegetation health maps could identify fields/patches likely to suffer drought impact, allowing for targeted intervention. Initial demonstrations of deep learning in agriculture show that it can handle complex data integration tasks [

82,

84,

85], paving the way for more autonomous monitoring systems.

Continued advances in machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI) [

89] will greatly facilitate these efforts. Emerging AI-driven platforms promise to ingest multi-modal data (satellite, drone, ground sensors, and historical yields) and automatically flag risks or recommend optimal interventions. A critical challenge, however, is ensuring that these integrated tools are accessible and trusted by end-users [

59]. Many farmers still struggle to access or interpret raw satellite data, highlighting the need for user-friendly interfaces and the co-design of information services. Moreover, information must be delivered in a timely and reliable manner to be actionable. Developing intuitive farm dashboards, mobile apps, and training programs [

42] will be essential to boost adoption and realize the resilience benefits of these technologies.

5. Conclusions

This review synthesized the methodologies of remote sensing (RS) across three interconnected themes for broadacre agriculture: crop productivity, phenology, and environmental stress. Each domain has demonstrated substantial progress over the recent decade. Productivity monitoring through vegetation indices (VIs) and RS–model fusion provides increasingly robust estimates of yield and yield gaps. Phenology detection has advanced via refined time-series analysis and multi-sensor fusion, with clear relevance for climate adaptation strategies. Stress detection, particularly of drought and heat, now enables near-real-time attribution of yield losses, with early identification of anomalies such as moisture deficits or canopy temperature rises.

However, limitations remain within each theme: 1) Productivity estimates are often indirect, sensitive to soil background and climatic variability, and constrained by cloud-free optical imagery. 2) Phenology monitoring remains challenged by coarse revisit intervals, cloud-related gaps, inconsistent stage definitions, and overlapping cycles in multi-cropping systems. 3) Stress detection methods are hindered by the non-specificity of spectral responses, the difficulty of identifying overlapping stressors, and the limited availability of ground-truth data for validation. Collectively, these limitations reduce the reliability and generalizability of RS applications across diverse production systems.

Recent research also highlights a shift toward integration across themes. Multi-sensor and multi-scale fusion merges optical, thermal, and multispectral signals, improving temporal coverage for applications such as phenology mapping in cloudy regions or stress detection across environments. RS–crop model data assimilation strengthens predictive capacity by continually updating growth simulations with observed indices, improving yield forecasts and enabling scenario testing at multiple scales. Operational and big data frameworks extend these advances to decision-support systems. Yet integration introduces significant challenges: 1) fusion algorithms must reconcile spatial and temporal mismatches; 2) assimilation requires careful calibration and quality ancillary data; 3) UAVs applications remain costly and difficult to scale; and 4) AI platforms are prone to overfitting and reliant on large training datasets. These limitations underscore the need for rigorous validation and scalable design to ensure operational impact.

Looking ahead, advancing remote sensing for resilience entails moving beyond monitoring toward integrated frameworks that establish clear metrics —such as yield stability, post-stress recovery, and soil-related indicators—and deliver predictive, actionable tools for sustainable broadacre agriculture.

Supplementary Materials

A list of the selected articles, including their complete bibliographic information, reviewed in this study can be downloaded at: Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S. and H.T.; methodology, J.S., H.W., and H.T.; data curation, J.S., H.W., and H.T.; formal analysis, J.S.; visualization, J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.S.; writing—review and editing, J.S., H.W. and H.T.; project administration, H.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

A list of the selected articles, including their complete bibliographic information, reviewed in this study can be downloaded at:

https://www.mdpi.com/article/doi/s1. All datasets used in the case study presented in this paper are publicly accessible through their respective official data portals.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Karen Holmes (DPIRD) for her valuable feedback and constructive input, and Dr. David Ferris (DPIRD) for his thoughtful comments that helped improve the quality of this manuscript. The first author acknowledges funding support from the Western Australian Government’s climate action program. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (model GPT-4o) for the purposes of assisting with structuring the manuscript and grammar checking during later stages. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Biradar, Chandrashekhar M., Prasad S. Thenkabail, Praveen Noojipady, Yuanjie Li, Venkateswarlu Dheeravath, Hugh Turral, Manohar Velpuri, Murali K. Gumma, Obi Reddy P. Gangalakunta, Xueliang L. Cai, Xiangming Xiao, Mitchell A. Schull, Ranjith D. Alankara, Sarath Gunasinghe, and Sadir Mohideen. "A Global Map of Rainfed Cropland Areas (Gmrca) at the End of Last Millennium Using Remote Sensing." International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 11, no. 2 (2009): 114-29. [CrossRef]

- Ray, Deepak K., James S. Gerber, Graham K. MacDonald, and Paul C. West. "Climate Variation Explains a Third of Global Crop Yield Variability." Nature Communications 6, no. 1 (2015): 5989. [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, Lipy, Adam M. Komarek, Peter de Voil, and Daniel Rodriguez. "A Framework for the Assessment of Farm Diversification Options in Broadacre Agriculture." Agricultural Systems 210 (2023): 103724. [CrossRef]

- Salinger, M. James. "Climate Variability and Change: Past, Present and Future – an Overview." Climatic Change 70, no. 1 (2005): 9-29. [CrossRef]

- Vogel, Elisabeth, Markus G. Donat, Lisa V. Alexander, Malte Meinshausen, Deepak K. Ray, David Karoly, Nicolai Meinshausen, and Katja Frieler. "The Effects of Climate Extremes on Global Agricultural Yields." Environmental Research Letters 14, no. 5 (2019): 054010. [CrossRef]

- Rebetzke, GJ, AL Fletcher, T Green, J Bathgate, E Wang, K Porker, M Clifton, JA Kirkegaard, SM Rich, and AF van Herwaarden. "Breeding Systems Resilience for Reliable Crop Production with Changing Climates." Paper presented at the GRDC Update 2025, Perth 2025.

- Hughes, Neal, David Galeano, and Steve Hatfield-Dodds. "The Effects of Drought and Climate Variability on Australian Farms." Paper presented at the ABARES Insights, Canberra, Australia: ABARES 2019.

- Lobell, David B., and Christopher B. Field. "Global Scale Climate–Crop Yield Relationships and the Impacts of Recent Warming." Environmental Research Letters 2, no. 1 (2007): 014002. [CrossRef]

- Heino, Matias, Pekka Kinnunen, Weston Anderson, Deepak K. Ray, Michael J. Puma, Olli Varis, Stefan Siebert, and Matti Kummu. "Increased Probability of Hot and Dry Weather Extremes During the Growing Season Threatens Global Crop Yields." Scientific Reports 13, no. 1 (2023): 3583. [CrossRef]

- Pret, Valentin, Gatien N. Falconnier, François Affholder, Marc Corbeels, Regis Chikowo, and Katrien Descheemaeker. "Farm Resilience to Climatic Risk - a Review." Agronomy for Sustainable Development 45, no. 1 (2025): 10. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Bingfang, Miao Zhang, Hongwei Zeng, Fuyou Tian, Andries B Potgieter, Xingli Qin, Nana Yan, Sheng Chang, Yan Zhao, Qinghan Dong, Vijendra Boken, Dmitry Plotnikov, Huadong Guo, Fangming Wu, Hang Zhao, Bart Deronde, Laurent Tits, and Evgeny Loupian. "Challenges and Opportunities in Remote Sensing-Based Crop Monitoring: A Review." National Science Review 10, no. 4 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Galieni, Angelica, Nicola D'Ascenzo, Fabio Stagnari, Giancarlo Pagnani, Qingguo Xie, and Michele Pisante. "Past and Future of Plant Stress Detection: An Overview from Remote Sensing to Positron Emission Tomography." Frontiers in Plant Science Volume 11 - 2020 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Berger, Katja, Miriam Machwitz, Marlena Kycko, Shawn C. Kefauver, Shari Van Wittenberghe, Max Gerhards, Jochem Verrelst, Clement Atzberger, Christiaan van der Tol, Alexander Damm, Uwe Rascher, Ittai Herrmann, Veronica Sobejano Paz, Sven Fahrner, Roland Pieruschka, Egor Prikaziuk, Ma Luisa Buchaillot, Andrej Halabuk, Marco Celesti, Gerbrand Koren, Esra Tunc Gormus, Micol Rossini, Michael Foerster, Bastian Siegmann, Asmaa Abdelbaki, Giulia Tagliabue, Tobias Hank, Roshanak Darvishzadeh, Helge Aasen, Monica Garcia, Isabel Pôças, Subhajit Bandopadhyay, Mauro Sulis, Enrico Tomelleri, Offer Rozenstein, Lachezar Filchev, Gheorghe Stancile, and Martin Schlerf. "Multi-Sensor Spectral Synergies for Crop Stress Detection and Monitoring in the Optical Domain: A Review." Remote Sensing of Environment 280 (2022): 113198. [CrossRef]

- Duan, Keke, Anton Vrieling, Michael Schlund, Uday Bhaskar Nidumolu, Christina Ratcliff, Simon Collings, and Andrew Nelson. "Detection and Attribution of Cereal Yield Losses Using Sentinel-2 and Weather Data: A Case Study in South Australia." ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 213 (2024): 33-52. [CrossRef]

- Team, R Core. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria.: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2024. https://www.R-project.org/.

- Racine, Jeffrey S. "Rstudio: A Platform-Independent Ide for R and Sweave." JSTOR, 2012.

- Wickham, Hadley, Winston Chang, and Maintainer Hadley Wickham. "Package ‘ggplot2’." Create elegant data visualisations using the grammar of graphics 2, no. 1 (2016): 1-189.

- Chen, Hanbo. Venndiagram: Generate High-Resolution Venn and Euler Plots: R package version 1.7.3, 2022.

- OpenAI. "Chatgpt (Gpt-4o) [Large Language Model]." https://chat.openai.com/chat (accessed July 2025).

- Brisco, B., Brown R. J., Hirose T., McNairn H., and K. and Staenz. "Precision Agriculture and the Role of Remote Sensing: A Review." Canadian Journal of Remote Sensing 24, no. 3 (1998): 315-27. [CrossRef]

- Pinter Jr, Paul J, Jerry L Hatfield, James S Schepers, Edward M Barnes, M Susan Moran, Craig ST Daughtry, and Dan R Upchurch. "Remote Sensing for Crop Management." Photogrammetric Engineering & Remote Sensing 69, no. 6 (2003): 647-64. [CrossRef]

- Carfagna, Elisabetta, and F. Javier Gallego. "Using Remote Sensing for Agricultural Statistics." International Statistical Review 73, no. 3 (2005): 389-404. [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M., F. Jacob, and G. Duveiller. "Remote Sensing for Agricultural Applications: A Meta-Review." Remote Sensing of Environment 236 (2020): 111402. [CrossRef]

- Running, Steven W. "Estimating Terrestrial Primary Productivity by Combining Remote Sensing and Ecosystem Simulation." In Remote Sensing of Biosphere Functioning, edited by R. J. Hobbs and Harold A. Mooney, 65-86. New York, NY: Springer New York, 1990. [CrossRef]

- Bannari, A., D. Morin, F. Bonn, and A. R. Huete. "A Review of Vegetation Indices." Remote Sensing Reviews 13, no. 1-2 (1995): 95-120. [CrossRef]

- Ji, Zhonglin, Yaozhong Pan, Xiufang Zhu, Jinyun Wang, and Qiannan Li. "Prediction of Crop Yield Using Phenological Information Extracted from Remote Sensing Vegetation Index." Sensors 21, no. 4 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Bolton, Douglas K., and Mark A. Friedl. "Forecasting Crop Yield Using Remotely Sensed Vegetation Indices and Crop Phenology Metrics." Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 173 (2013): 74-84. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Jianxiu, and Fiona H. Evans. "The Potential of Landsat Ndvi Sequences to Explain Wheat Yield Variation in Fields in Western Australia." Remote Sensing 13, no. 11 (2021): 2202. [CrossRef]

- Evans, Fiona H., and Jianxiu Shen. "Long-Term Hindcasts of Wheat Yield in Fields Using Remotely Sensed Phenology, Climate Data and Machine Learning." Remote Sensing 13, no. 13 (2021): 2435. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Feng, and Xiaoyang Zhang. "Mapping Crop Phenology in near Real-Time Using Satellite Remote Sensing: Challenges and Opportunities." Journal of Remote Sensing 2021 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Evans, Fiona H., and Jianxiu Shen. "Spatially Weighted Estimation of Broadacre Crop Growth Improves Gap-Filling of Landsat Ndvi." Remote Sensing 13, no. 11 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Mishra, Vikalp, James F. Cruise, John R. Mecikalski, Christopher R. Hain, and Martha C. Anderson. "A Remote-Sensing Driven Tool for Estimating Crop Stress and Yields." Remote Sensing 5, no. 7 (2013): 3331-56. [CrossRef]

- Amin, Naz Ul, Fakhrul Islam, Muhammad Umar, Waqas Muhammad, Siddiq Ur Rahman, Abdel-Rhman Z. Gaafar, Tawaf Ali Shah, Musaab Dauelbait, and Mohammed Bourhia. "Evaluation of Crop Phenology Using Remote Sensing and Decision Support System for Agrotechnology Transfer." Scientific Reports 15, no. 1 (2025): 11582. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Sandeep, Ram Swaroop Meena, Seema Sheoran, Chetan Kumar Jangir, Manoj Kumar Jhariya, Arnab Banerjee, and Abhishek Raj. "Chapter 5 - Remote Sensing for Agriculture and Resource Management." In Natural Resources Conservation and Advances for Sustainability, edited by Manoj Kumar Jhariya, Ram Swaroop Meena, Arnab Banerjee and Surya Nandan Meena, 91-135: Elsevier, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Yan, Andries B Potgieter, Miao Zhang, Bingfang Wu, and Graeme L Hammer. "Predicting Wheat Yield at the Field Scale by Combining High-Resolution Sentinel-2 Satellite Imagery and Crop Modelling." Remote Sensing 12, no. 6 (2020): 1024. [CrossRef]

- Kullberg, Emily G., Kendall C. DeJonge, and José L. Chávez. "Evaluation of Thermal Remote Sensing Indices to Estimate Crop Evapotranspiration Coefficients." Agricultural Water Management 179 (2017): 64-73. [CrossRef]

- Lawes, Roger, Gonzalo Mata, Jonathan Richetti, Andrew Fletcher, and Chris Herrmann. "Using Remote Sensing, Process-Based Crop Models, and Machine Learning to Evaluate Crop Rotations across 20 Million Hectares in Western Australia." Agronomy for Sustainable Development 42, no. 6 (2022): 120. [CrossRef]

- Rong, Liang-bing, Kai-yuan Gong, Feng-ying Duan, Shao-kun Li, Ming Zhao, Jianqiang He, Wen-bin Zhou, and Qiang Yu. "Yield Gap and Resource Utilization Efficiency of Three Major Food Crops in the World – a Review." Journal of Integrative Agriculture 20, no. 2 (2021): 349-62. [CrossRef]

- Atzberger, Clement. "Advances in Remote Sensing of Agriculture: Context Description, Existing Operational Monitoring Systems and Major Information Needs." Remote Sensing 5, no. 8 (2013): 4124-24. [CrossRef]

- Duncan, John M., Jadunandan Dash, and Peter M. Atkinson. "The Potential of Satellite-Observed Crop Phenology to Enhance Yield Gap Assessments in Smallholder Landscapes." Frontiers in Environmental Science Volume 3 - 2015 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Maes, Wouter H., and Kathy Steppe. "Perspectives for Remote Sensing with Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in Precision Agriculture." Trends in Plant Science 24, no. 2 (2019): 152-64. [CrossRef]

- Khanal, Sami, Kushal KC, John P. Fulton, Scott Shearer, and Erdal Ozkan. "Remote Sensing in Agriculture—Accomplishments, Limitations, and Opportunities." Remote Sensing 12, no. 22 (2020): 3783. [CrossRef]

- Hunt Jr, E. Raymond, and Craig S. T. and Daughtry. "What Good Are Unmanned Aircraft Systems for Agricultural Remote Sensing and Precision Agriculture?" International Journal of Remote Sensing 39, no. 15-16 (2018): 5345-76. [CrossRef]

- Martos, Vanesa, Ali Ahmad, Pedro Cartujo, and Javier Ordoñez. "Ensuring Agricultural Sustainability through Remote Sensing in the Era of Agriculture 5.0." Applied Sciences 11, no. 13 (2021): 5911. [CrossRef]

- Sishodia, Rajendra P., Ram L. Ray, and Sudhir K. Singh. "Applications of Remote Sensing in Precision Agriculture: A Review." Remote Sensing 12, no. 19 (2020): 3136. [CrossRef]

- Shahzaman, Muhammad, Weijun Zhu, Muhammad Bilal, Birhanu A. Habtemicheal, Farhan Mustafa, Muhammad Arshad, Irfan Ullah, Shazia Ishfaq, and Rashid Iqbal. "Remote Sensing Indices for Spatial Monitoring of Agricultural Drought in South Asian Countries." Remote Sensing 13, no. 11 (2021). [CrossRef]

- You, Xingzhi, Jihua Meng, Miao Zhang, and Taifeng Dong. "Remote Sensing Based Detection of Crop Phenology for Agricultural Zones in China Using a New Threshold Method." Remote Sensing 5, no. 7 (2013): 3190-211. [CrossRef]

- Viña, Andrés, Anatoly A. Gitelson, Donald C. Rundquist, Galina Keydan, Bryan Leavitt, and James Schepers. "Monitoring Maize (Zea Mays L.) Phenology with Remote Sensing." Agronomy Journal 96, no. 4 (2004): 1139-47. [CrossRef]

- Seelan, Santhosh K., Soizik Laguette, Grant M. Casady, and George A. Seielstad. "Remote Sensing Applications for Precision Agriculture: A Learning Community Approach." Remote Sensing of Environment 88, no. 1 (2003): 157-69. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Yanbo, Zhong-xin Chen, Tao Yu, Xiang-zhi Huang, and Xing-fa Gu. "Agricultural Remote Sensing Big Data: Management and Applications." Journal of Integrative Agriculture 17, no. 9 (2018): 1915-31. [CrossRef]

- Gobin, Anne, Abdoul-Hamid M. Sallah, Yannick Curnel, Cindy Delvoye, Marie Weiss, Joost Wellens, Isabelle Piccard, Viviane Planchon, Bernard Tychon, Jean-Pierre Goffart, and Pierre Defourny. "Crop Phenology Modelling Using Proximal and Satellite Sensor Data." Remote Sensing 15, no. 8 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, Toshihiro, Masayuki Yokozawa, Hitoshi Toritani, Michio Shibayama, Naoki Ishitsuka, and Hiroyuki Ohno. "A Crop Phenology Detection Method Using Time-Series Modis Data." Remote Sensing of Environment 96, no. 3–4 (2005): 366-74. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yue, Zengxiang Zhang, Lijun Zuo, Xiao Wang, Xiaoli Zhao, and Feifei Sun. "Mapping Crop Distribution Patterns and Changes in China from 2000 to 2015 by Fusing Remote-Sensing, Statistics, and Knowledge-Based Crop Phenology." Remote Sensing 14, no. 8 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Rodigheri, Grazieli, Ieda D. Sanches, Jonathan Richetti, Rodrigo Y. Tsukahara, Roger Lawes, Hugo D. Bendini, and Marcos Adami. "Estimating Crop Sowing and Harvesting Dates Using Satellite Vegetation Index: A Comparative Analysis." Remote Sensing 15, no. 22 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Araya, Sofanit, Bertram Ostendorf, Gregory Lyle, and Megan Lewis. "Cropphenology: An R Package for Extracting Crop Phenology from Time Series Remotely Sensed Vegetation Index Imagery." Ecological Informatics 46 (2018): 45-56. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Wenzhi, Yang Qu, Liqiang Zhang, and Kaiyuan Li. "Spatial-Aware Sar-Optical Time-Series Deep Integration for Crop Phenology Tracking." Remote Sensing of Environment 276 (2022): 113046. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Jianxiu, Alfredo Huete, Xuanlong Ma, Ngoc Nguyen Tran, Joanna Joiner, Jason Beringer, Derek Eamus, and Qiang Yu. "Spatial Pattern and Seasonal Dynamics of the Photosynthesis Activity across Australian Rainfed Croplands." Ecological Indicators 108 (2020): 105669. [CrossRef]

- Diao, Chunyuan, and Geyang Li. "Near-Surface and High-Resolution Satellite Time Series for Detecting Crop Phenology." Remote Sensing 14, no. 9 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Hufkens, Koen, Eli K. Melaas, Michael L. Mann, Timothy Foster, Francisco Ceballos, Miguel Robles, and Berber Kramer. "Monitoring Crop Phenology Using a Smartphone Based near-Surface Remote Sensing Approach." Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 265 (2019): 327-37. [CrossRef]

- Worrall, George, Jasmeet Judge, Kenneth Boote, and Anand Rangarajan. "In-Season Crop Phenology Using Remote Sensing and Model-Guided Machine Learning." Agronomy Journal 115, no. 3 (2023): 1214-36. [CrossRef]

- Pei, Jie, Shaofeng Tan, Yaopeng Zou, Chunhua Liao, Yinan He, Jian Wang, Huabing Huang, Tianxing Wang, Haifeng Tian, Huajun Fang, Li Wang, and Jianxi Huang. "The Role of Phenology in Crop Yield Prediction: Comparison of Ground-Based Phenology and Remotely Sensed Phenology." Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 361 (2025): 110340. [CrossRef]

- Potgieter, Andries B, Yan Zhao, Pablo J Zarco-Tejada, Karine Chenu, Yifan Zhang, Kenton Porker, Ben Biddulph, Yash P Dang, Tim Neale, Fred Roosta, and Scott Chapman. "Evolution and Application of Digital Technologies to Predict Crop Type and Crop Phenology in Agriculture." in silico Plants 3, no. 1 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Shen, Jianxiu, Alfredo Huete, Ngoc Nguyen Tran, Rakhesh Devadas, Xuanlong Ma, Derek Eamus, and Qiang Yu. "Diverse Sensitivity of Winter Crops over the Growing Season to Climate and Land Surface Temperature across the Rainfed Cropland-Belt of Eastern Australia." Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 254 (2018): 99-110. [CrossRef]

- Boschetti, M., Stroppiana D., Brivio P. A., and S. and Bocchi. "Multi-Year Monitoring of Rice Crop Phenology through Time Series Analysis of Modis Images." International Journal of Remote Sensing 30, no. 18 (2009): 4643-62. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Hu, Zhengwei Yang, Liping Di, and Zhiyuan Pei. "Evaluation of Temporal Resolution Effect in Remote Sensing Based Crop Phenology Detection Studies." Paper presented at the Computer and Computing Technologies in Agriculture V, Berlin, Heidelberg 2012. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Zhuokun, Jingfeng Huang, Qingbo Zhou, Limin Wang, Yongxiang Cheng, Hankui Zhang, George Alan Blackburn, Jing Yan, and Jianhong Liu. "Mapping Crop Phenology Using Ndvi Time-Series Derived from Hj-1 a/B Data." International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 34 (2015): 188-97. [CrossRef]

- Eamus, Derek, Alfredo Huete, and Qiang Yu. Vegetation Dynamics: A Synthesis of Plant Ecophysiology, Remote Sensing and Modelling. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Ozdogan, Mutlu, Yang Yang, George Allez, and Chelsea Cervantes. "Remote Sensing of Irrigated Agriculture: Opportunities and Challenges." Remote Sensing 2, no. 9 (2010): 2274-304. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Harmandeep, Harjot Sidhu, and Arnab Bhowmik. "Remote Sensing Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles for Water Stress Detection: A Review Focusing on Specialty Crops." Drones 9, no. 4 (2025): 241. [CrossRef]

- Taiwo, Balogun Emmanuel, Abdulla Al Kafy, Ajeyomi Adedoyin Samuel, Zullyadini A. Rahaman, Ologun Emmanuel Ayowole, Mahir Shahrier, Bushra Monowar Duti, Muhammad Tauhidur Rahman, Olarewaju Timilehin Peter, and Olamiju Olayinka Abosede. "Monitoring and Predicting the Influences of Land Use/Land Cover Change on Cropland Characteristics and Drought Severity Using Remote Sensing Techniques." Environmental and Sustainability Indicators 18 (2023): 100248. [CrossRef]