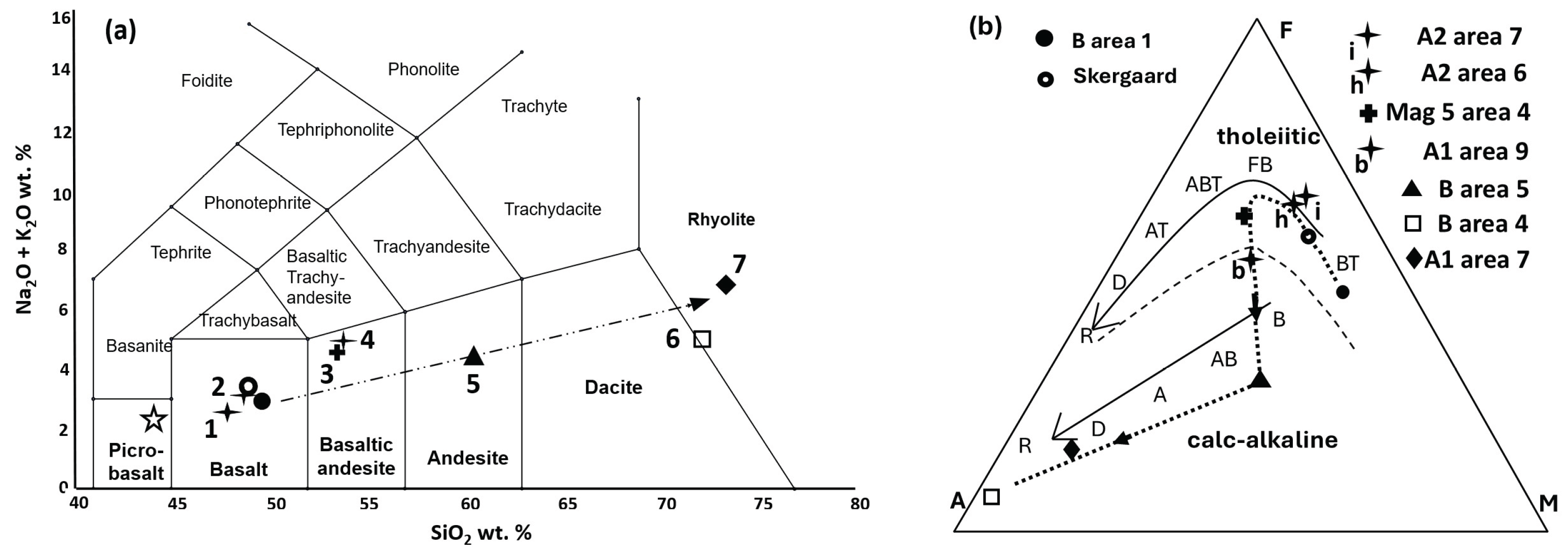

3.1.1. Sample A2 Area 7

a) Host alloy and ferrobasalt silicate glass (SiO2 47.43 wt. %).

This host nugget is rounded (

Figure 2a) but distinctly deformed (flattened) and reaches ~987 µm long and ~370 µm across. The prominent rounded silicate glass inclusion (~191 µm long and ~146 µm across) also is flattened; with adjacent, elongate triangular strain shadows, possibly parallel to a foliation direction.

Analysis 277 (Barron et al. [

1] Tables 1A and 1B; and

Table 1 below) indicates host

native platinum (Pt

2.95Rh

0.09Pd

0.06 Ir

0.01Os

0.01)

3.12(Fe

0.80Cu

0.07Ni

0.01)

0.88 with the following minor elements in decreasing order of abundance Rh, Cu, Pd, Ir, Os and Ni.

A distinct ‘corona’ is defined by an arc of small (~1–5 µm) inclusions with Cu-PGE sulfide parageneses located near the nugget margin and distant from their host basaltic glass inclusion (

Figure 2a). These inclusions have irregular shapes and also show elongate narrow strain shadows in

Figure 2b.

Analysis 176 (Barron et al. [

1] Table 2E) indicates coexisting (host) silicate glass in this inclusion is ferrobasalt with SiO

2 47.43, FeO 17.62, MgO 6.13 (wt. %) and minor H

2O ~0.31. This glass is the least siliceous of the present samples.

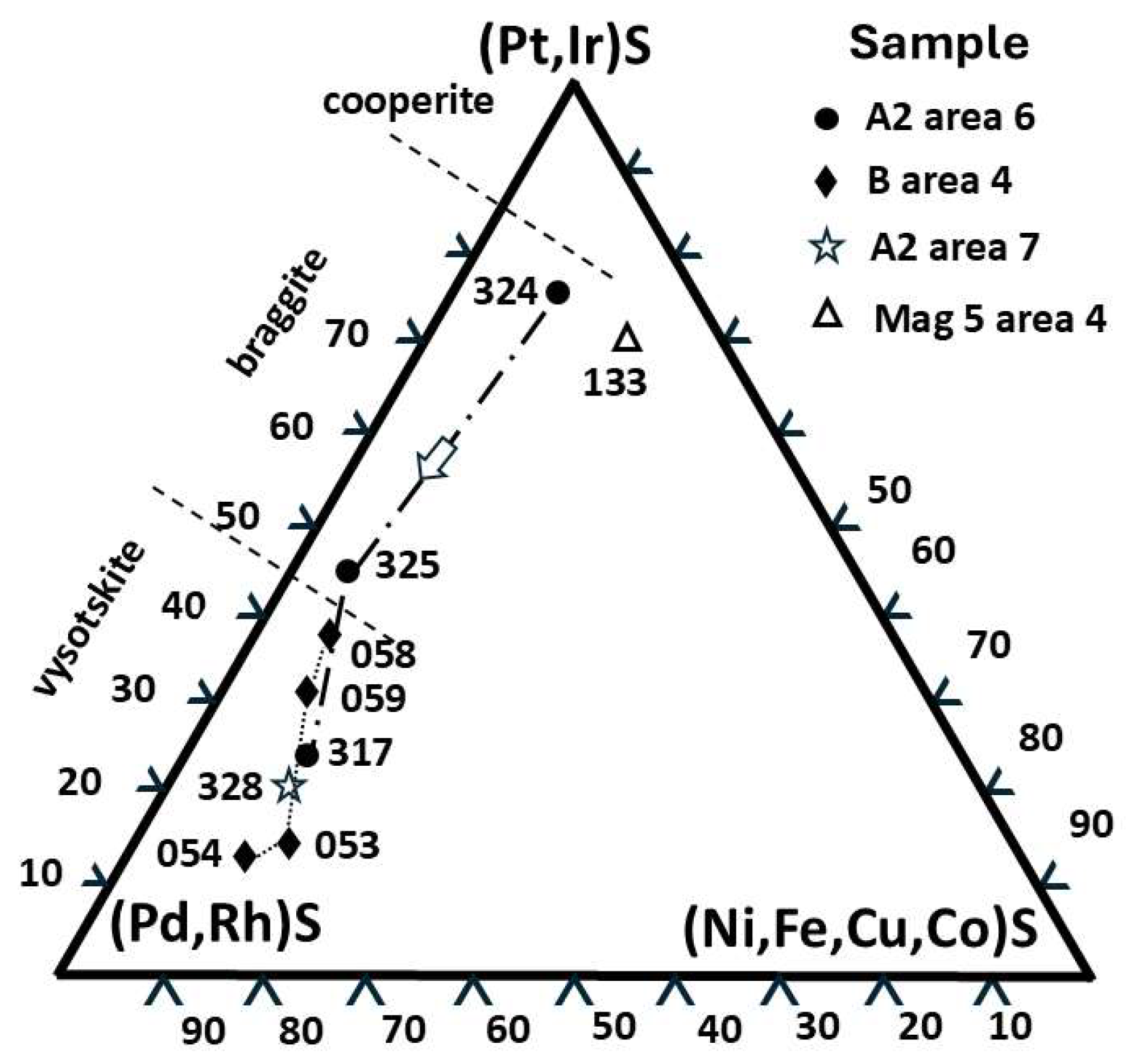

b) PGM sulfide paragenesis.

Cuprorhodsite–(malanite) (

Figure 2b) is a small (~2.5 µm) subhedral crystal set in a strain shadow microstructure. A

nalysis 327 (

Table 1) indicates (Cu

0.85Fe

0.12Ni

0.03)

1.00(Rh

1.26Pt

0.62Pd

0.05Ru

0.05Ir

0.03Os

0.01)

1.96S

3.96. The strain shadow host mineral is too small for accurate analysis.

Vysotskite occurs as a subhedral crystal in a separate inclusion (

Figure 2c).

Analysis (328) (

Table 1) indicates the following Pd-rich vysotskite formula (Pd

0.64Pt

0.20Cu

0.04Fe

0.04Ni

0.03)

0.91S

1.04 (cf. Cabri and McDonald [

19] their Figure 1). A fibrous irregular matrix fraction is too small for analysis.

3.1.2. Sample A2 Area 6

a) Host alloy and ferrobasalt silicate glass (SiO2 47.83 wt. %).

This host Pt-Fe nugget (~0.7 mm diameter) is rounded with a partly broken margin (

Figure 3a,b).

Analysis 276 (Barron

et al. [

1] Tables 1A and 1B and

Table 2 below) is isoferroplatinum (Pt

2.95Rh

0.08Pd

0.05 Ir

0.01)

3.09(Fe

0.74Cu

0.17)

0.91 with minor Cu, Rh and Pd.

Seven inclusions are present, four of which are considered here (

Figure 3a,b). The largest is a rounded silicate glass inclusion (~28 µm diameter) with a small vesicle (possible gas cavity) about 7 µm across, located near the margin. The silicate glass has a narrow but irregular partial rim of exsolved PGM with Cu-sulfides, the boundary of which against the host nugget is exceptional. It shows well preserved quench textures of cuspate crests and related small ‘droplets’ within the host Pt-Fe alloy. A similar very narrow rim of exsolved Cu-PGM occurs around a smaller silicate glass inclusion not considered here. Three smaller, rounded inclusions are Cu-PGM parageneses like that of the exsolved PGM sulfide rim of the largest silicate glass inclusion (above). They show similar, well preserved, irregular boundaries against the host nugget.

Analysis 172 of the silicate glass (Barron

et al. [

1] Table 2E) indicates ferrobasalt with SiO

2 47.83, FeO 15.68, MgO 5.52 and minor H

2O ~1.17 (wt. %).

b) PGM and Cu-sulfide paragenesis.

S

ulfide parageneses and their textural features are similar in each of five melt inclusions (

Figure 3). Small subhedral crystals are braggite and cuprorhodsite, while zoned braggite occurs as subhedral to anhedral patches (up to 13 µm long). Bornite contains up to ~20% of

PGE monosulfide as exsolved crystallites (see below). Some of the latter are subhedral (up to ~3.0 µm grain size) and many are skeletal, branching and crystallographically controlled (reaching ~5 µm long). Bornite also hosts subordinate irregular patches of chalcopyrite (yellow,

Figure 3a).

Braggite occurs as subhedral white crystals (

Figure 3f).

Analysis 8(324)

Table 2 gives Pt 35.21

Pd 5.56 with 4.17 at. % minor elements (Cu, Fe, Rh, Ni and Os) and slightly high S. A second

braggite analysis 9(325) (

Table 2,

Figure 3c) gives Pt 19.64,

Pd 19.55 (at. %) and minor PGE 6.19 (at. %) (cf.

Figure 1, Cabri and McDonald [

19]). This analysis is for an anhedral interstitial grain with marginal zoning. It occurs within the narrow rim of PGM sulfide parageneses adjacent to the largest silicate glass inclusion (

Figure 3c).

A third, semiquantitative [

20] analysis (317) is for an irregular, narrow (~3 µm across) zoned grain (

Figure 3d) indicating

Pd reaches 30.76 and Pt is 11.41 at. % (+ ~6.50 at. % PGE minor elements, and Se also is present). The formula for this composition (Fe

0.02Ni

0.05Cu

0.05Pd

0.59Pt

0.22S

1.00) defines

vysotskite (cf. Cabri and McDonald [

19]

Figure 1).

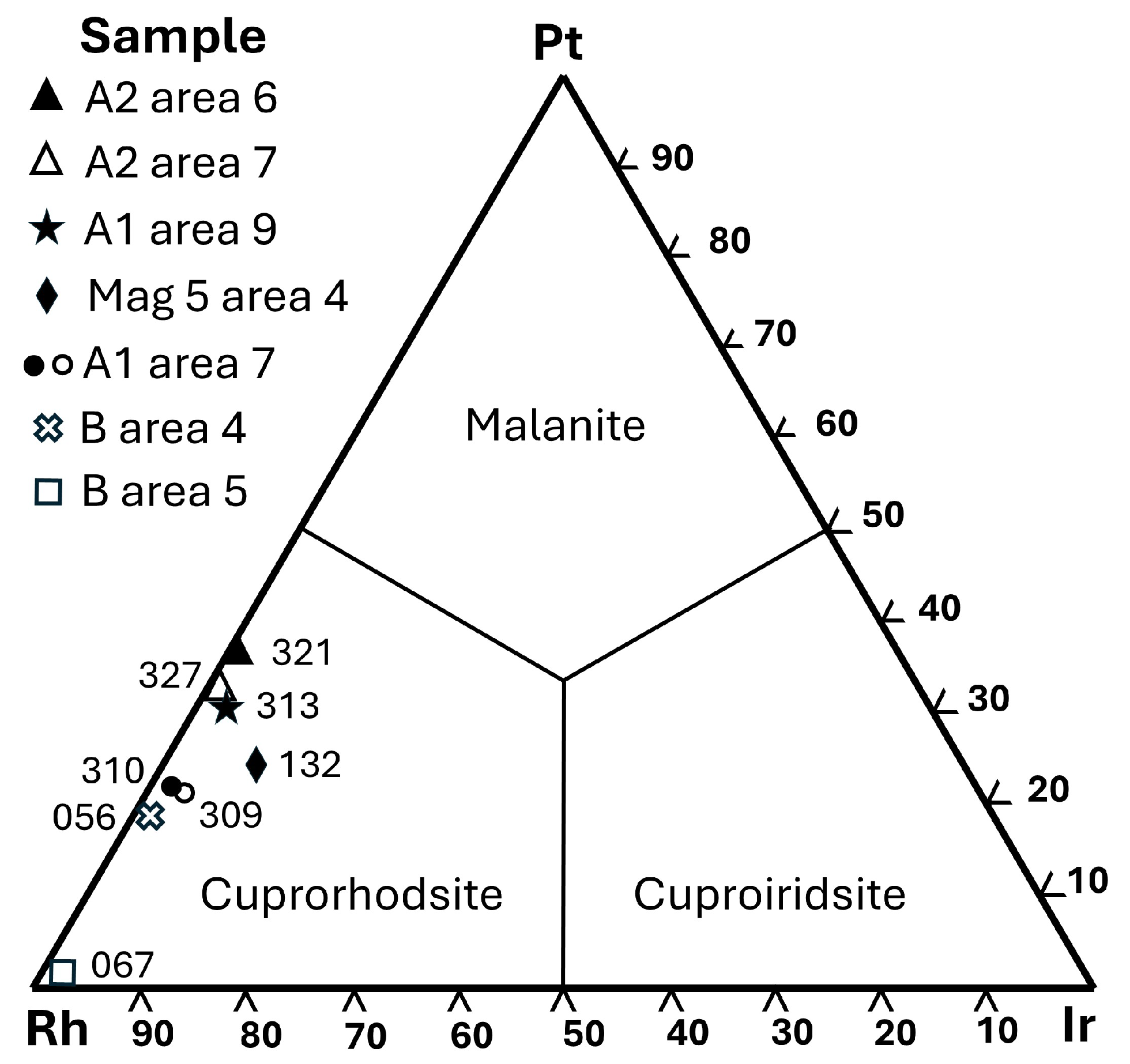

Cuprorhodsite–(malanite) occurs as mid-grey subhedral crystals (

Figure 3e) set in bornite.

Analysis 4(321),

Table 2, gives the following formula Cu

0.95(Rh

1.08Pt

0.63Fe

0.19Ir

0.02Co

0.02Ni

0.01Ru

0.01)

1.95(S

3.99Se

0.01)

4.00 with Rh 15.64 at. % and Pt(+Ir) 9.39

. Bornite and

chalcopyrite are confirmed as anhedral interstitial minerals. Semiquantitative [

20] analyses 318 and 323 (

Figure 3d,f) are bornite. Analysis 322 (

Figure 3e) is chalcopyrite. Respective formulae are Cu

4.69Fe

0.90S

3.99Se

0.01 for bornite and Cu

1.00Fe

0.90S

2.00 for chalcopyrite.

A

monosulfide mineral occurs as irregular and skeletal shaped exsolutions set in host bornite [

Figure 3(c, e)]. WDS

analysis (320) (

Table 2) of the latter [a small (< 3 µm) grain] gives a slightly low total, thus is semiquantitative cf. Nesterenko et al. [

20]. However, a distinctive formula indicates the Cu-rich, Ni-poor

PGE monosulfide mineral (Cu

0.55Fe

0.11)

∑0.66(Rh

0.19Pt

0.13Ir

0.01)

∑0.33S

1.00 with dominant Cu(+Fe), subordinate PGE and minor detectable Co, Ru and Ni (cf. Tolstykh & Krivenko [

21]).

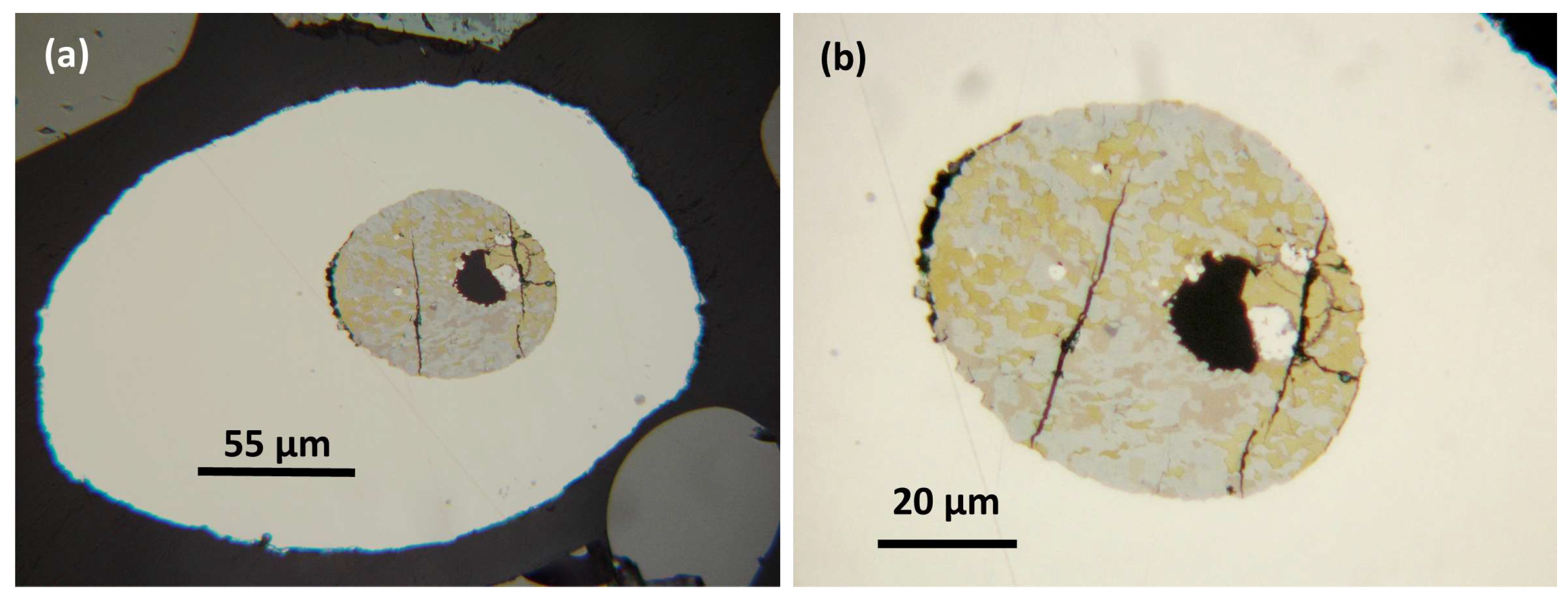

3.1.3. Sample Mag 5 Area 4

a) Host alloy and basaltic andesite silicate glass (SiO2 52.30 wt. %).

The

host nugget for this sample is oval shaped (~0.22 mm long dimension) and hosts a composite rounded inclusion (~0.09 mm diameter) located near one margin (

Figure 4a).

Analysis 129 (Tables 1A and 1B of Barron

et al. [

1] and

Table 4, below) indicates isoferroplatinum (Pt

2.89Ir

0.06Pd

0.02Os

0.01)

2.98(Fe

0.88Cu

0.06Rh

0.08)

1.02 with minor Rh, Cu, Pd, Os and S. The inclusion comprises a remarkable PGM paragenesis coexisting with a small rounded to partly irregular ‘pool’ of exsolved silicate glass partly infilled with late Pt-Fe alloy and subhedral chalcopyrite (

Figure 4a,b).

The small ‘pool’ of host silicate glass shows a minutely scalloped boundary with the variably thick rim of exsolved PGM. The boundary of the latter against the host nugget is partly rounded and partly finely scalloped. A small void along part of the curved margin of the inclusion suggests minor compressional deformation (possibly in the alluvial pile) accompanied by distinct parallel brittle fractures in the PGM paragenesis.

Analysis of the silicate glass inclusion indicates tholeiitic

basaltic andesite with SiO

2 52.30, FeO 12.96 and H

2O ~0.45 wt. % (average of analyses Sp24 and Sp25, Barron

et al. [

1] Table 2C). Silicate glass accounts for ~ 5.7% of the total composite inclusion.

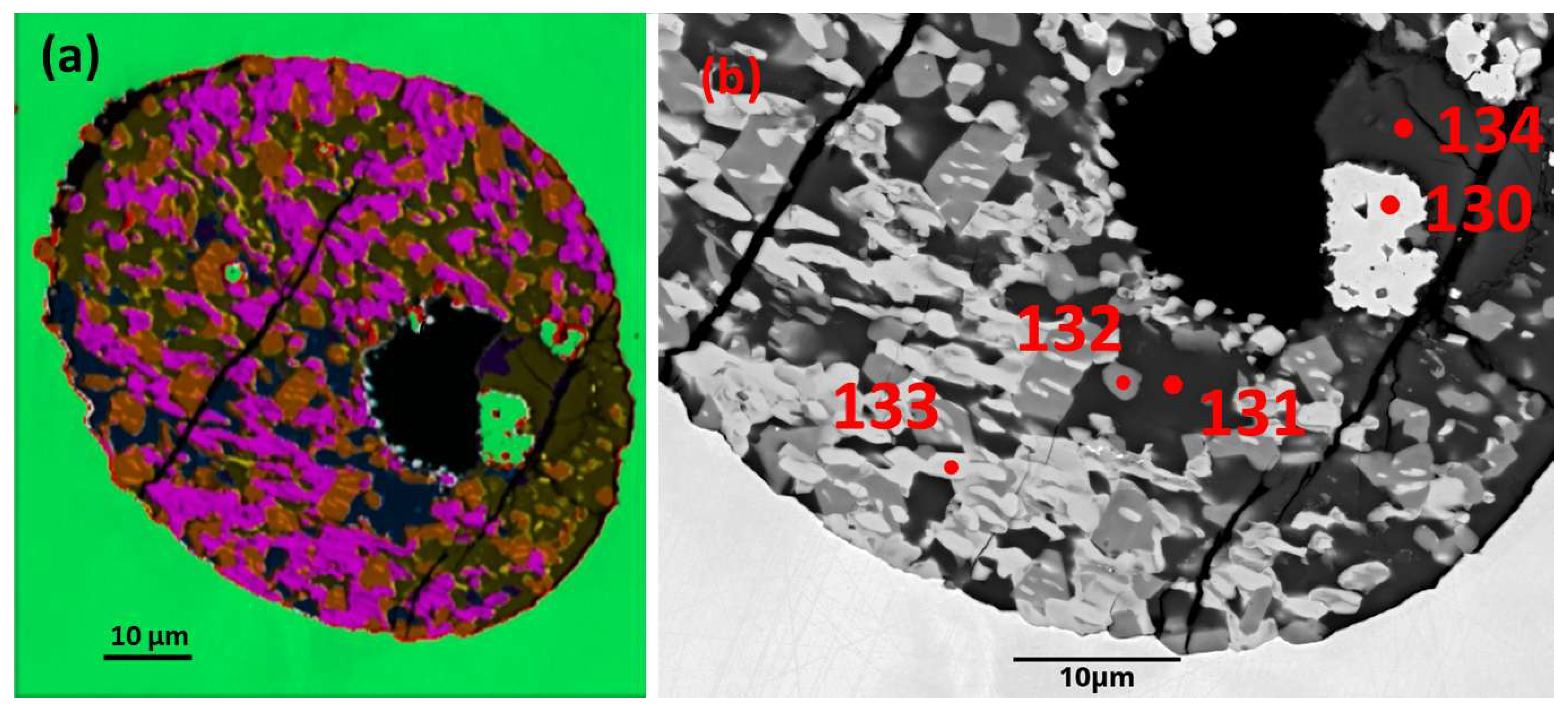

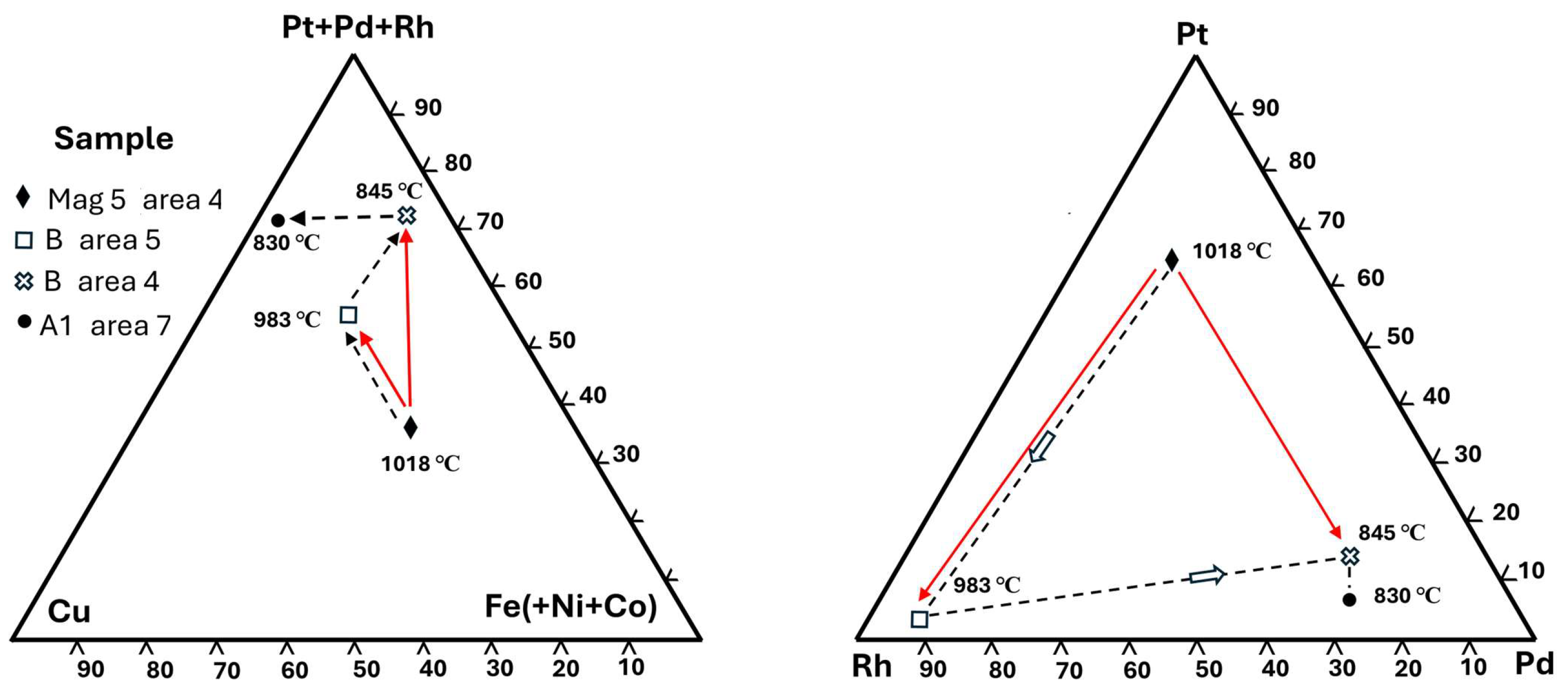

b) PGM sulfide paragenesis.

Phase mapping, based on EDS analysis of this inclusion (

Figure 5a), gives an approximate fraction % based on relative pixel counts for each phase. There are five significant minerals detected, and their approximate fraction % (minus 5.7% silicate glass) is as follows: Green is Pt-Fe alloy 3.18; PtSRhFe (composite cuprorhodsite + alloy = monosulfide) 24.92; PtSPd (braggite) 30.22; SCuFePt (chalcopyrite) 33.40; and FeS (pyrrhotite) 8.27. A minor mineral (analysis FeSCu) also is detected.

An approximate calculated bulk chemistry (Fe>Cu>Pt>>>Pd>Rh>>Ir>Ni>Co>Os at. %) based on EDS

element mapping of the PGM paragenesis is given in

Table 3.

A

composite monosulfide mineral PtSRhFe identified by phase mapping (

Table 4) is tan with orange exsolutions (

Figure 5a). It comprises small (from ~2µm up to ~8 µm long and ~3-4 µm across) subprismatic to equant crystals that are evenly disseminated throughout. This mineral accounts for ~23.5% of the inclusion area in the plane of the present section (see above). In some domains the crystals are sub-parallel but elsewhere are unoriented. Thin exsolved lenses are subparallel and crystallographically controlled in many larger crystals but some smaller crystals (minus alloy lenses) are homogeneous in the present section (

Figure 5a,b).

Table 4.

Analyses, sample Mag 5 area 4. Composite monosulfide mineral and cuprorhodsite lacking alloy exsolutions. Calculation of exsolved tetraferroplatinum exsolutions.

Table 4.

Analyses, sample Mag 5 area 4. Composite monosulfide mineral and cuprorhodsite lacking alloy exsolutions. Calculation of exsolved tetraferroplatinum exsolutions.

| 3PtSRhFeΔ

|

S |

Se |

Fe |

Co |

Ni |

Cu |

Ru |

Rh |

Pd |

Os |

Ir |

Pt |

Total |

| wt. % Ms |

26.85 |

|

10.90 |

0.24 |

0.15 |

8.27 |

|

12.60 |

2.86 |

0.84 |

3.13 |

34.18 |

100.00 |

| at. % ~Ms |

55.30 |

|

12.89 |

0.26 |

0.17 |

8.59 |

|

8.09 |

1.77 |

0.29 |

1.07 |

11.57 |

100.00 |

| apfu ~Ms |

1.00 |

|

0.23 |

0.01 |

|

0.16 |

|

0.15 |

0.04 |

0.01 |

0.02 |

0.21 |

0.83 |

| 3(132)^ |

S |

Se |

Fe |

Co |

|

Cu |

Ru |

Rh |

Pd |

Os |

Ir |

Pt |

Total |

| wt. % Crh |

29.19 |

0.03 |

5.58 |

0.29 |

|

11.39 |

0.24 |

26.48 |

|

1.84 |

6.73 |

17.78 |

99.55 |

| at. % Crh |

57.25 |

0.02 |

6.28 |

0.31 |

|

11.27 |

0.15 |

16.18 |

|

0.61 |

2.20 |

5.73 |

100.00 |

| apfu Crh |

4.02 |

|

0.44 |

0.02 |

|

0.79 |

0.01 |

1.14 |

|

0.04 |

0.15 |

0.40 |

Me 2.99 |

| Alloy* |

|

|

6.61 |

|

|

|

|

|

1.77 |

|

|

5.84 |

14.22 |

| ~ Tfpt at. % |

|

|

46.48 |

|

|

|

|

|

12.44 |

|

|

41.07 |

100.00 |

|

ΔPhase map EDS 3PtSRhFe (minus minor O, includes alloy lenses). ^WDS 3(132). Ms=monosulfide. Crh=cuprorhodsite–(malanite). Tfpt=tetraferroplatinum. *Calculated exsolved alloy (Fe, Pd, Pt), PtSRhFe minus Fe, Pd, Pt of Crh 3(132). |

The

lenses in the PtSRhFe host mineral, EDS phase map analysis (

Figure 5a) are too fine grained for accurate EMPA. However, as a composite PGM, both lenses and their host mineral are analysed together (analysis 3PtSRhFe,

Table 4, normalised minus minor O). This composite mineral analysis,

including the host mineral and narrow lenses, gives a Me (metal) deficient formula indicating the monosulfide mineral (Fe

0.23Pt

0.21Cu

0.16Rh

0.15Pd

0.04Ir

0.02Os

0.01Co

0.01)

0.83S

1.00. However, the WDS analysis 3(132) (

Table 4 and

Table 5;

Figure 5b) of the host mineral lacking exsolutions is

Fe, Pt, Pd poor cuprorhodsite

–(malanite) with formula (Cu

0.79Fe

2+0.19Co

0.02)

1.00(Rh

1.14Pt

0.40Fe

3+0.25Ir

0.15Os

0.04)

1.98S

4.02. This suggests that a composite monosulfide precursor mineral has

exsolved Fe-Pt-(Pd) alloy lenses in Fe, Pt, Pd poor cuprorhodsite. An approximate calculated composition for the exsolved alloy lenses is ~ Fe 46.48, Pt 41.07, and Pd 12.44 at. % (

Table 4) indicating Pd-bearing

tetraferroplatinum with a composition near PtFe

cf. Cabri et al.; Jung

et al. [

22,

23].

Pt-Fe alloy, green (

Figure 5a), accounts for only ~3.0% of the inclusion area and occurs as anhedral patches with variable grain size (up to ~5 µm across).

Analysis 1(130)

Table 5 and

Figure 5(b) shows that this alloy also is isoferroplatinum, distinct from host isoferroplatinum, with unusually high concentration of minor elements (8.35 at. %); Cu (2.91 at. %), Pd (2.65 at. %), Au (1.82 at. %), Rh, Ag and Os (in order of abundance).

Braggite, pink in

Figure 5a, accounts for ~ 28.5% of the inclusion area and forms elongate (possibly deformed) anhedral patches enclosing subhedral prisms of the composite monosulfide mineral with alloy exsolutions (above).

Analysis 4(133) (

Figure 5b,

Table 5) shows that this mineral, with Pt 69.80 wt.% and Pd 4.50 wt. %, contains significant (6.62 at. %) minor elements (Cu, Rh, Ni, Ir, Os, Co, Ir).

Chalcopyrite, yellow in

Figure 5a, accounts for ~31.5% of the inclusion area. It is a prominent anhedral, interstitial mineral in three quadrants of the thick rim of PGM sulfides and forms an unevenly distributed mineral throughout the fourth quadrant where it is intergrown with pyrrhotite (below). A

semiquantative analysis 5(134) (

Figure 5b) confirms chalcopyrite Cu

0.50Fe

0.50S

1.02 with minor detectable <0.02 at. % elements Se, Pt, Zn and Ca.

Pyrrhotite, blue in

Figure 5a, accounts for ~7.8% of the inclusion area. It is also anhedral and interstitial, intergrown with minor patchy chalcopyrite.

Analysis 2(131) (

Table 5) shows that seven minor elements are detected Pt 0.71 wt. % and < 0.22 wt. % each of Cu, Rh, Ni, Ca, Pd and Co (in decreasing order of abundance).

Isocubanite, identified by phase mapping (

Figure 5a) accounts for only ~1.1% of the inclusion area. It occurs as irregular, narrow interstitial patches up to ~5.8 µm long but < 3 µm across, so the crystals are too narrow for accurate EPMA. An EDS analysis (8FeSCu

Table 5) indicates isocubanite (Fe

0.66Cu

0.32Ni

0.02)

1.00S

0.98 first defined by Caye et al. [

24].

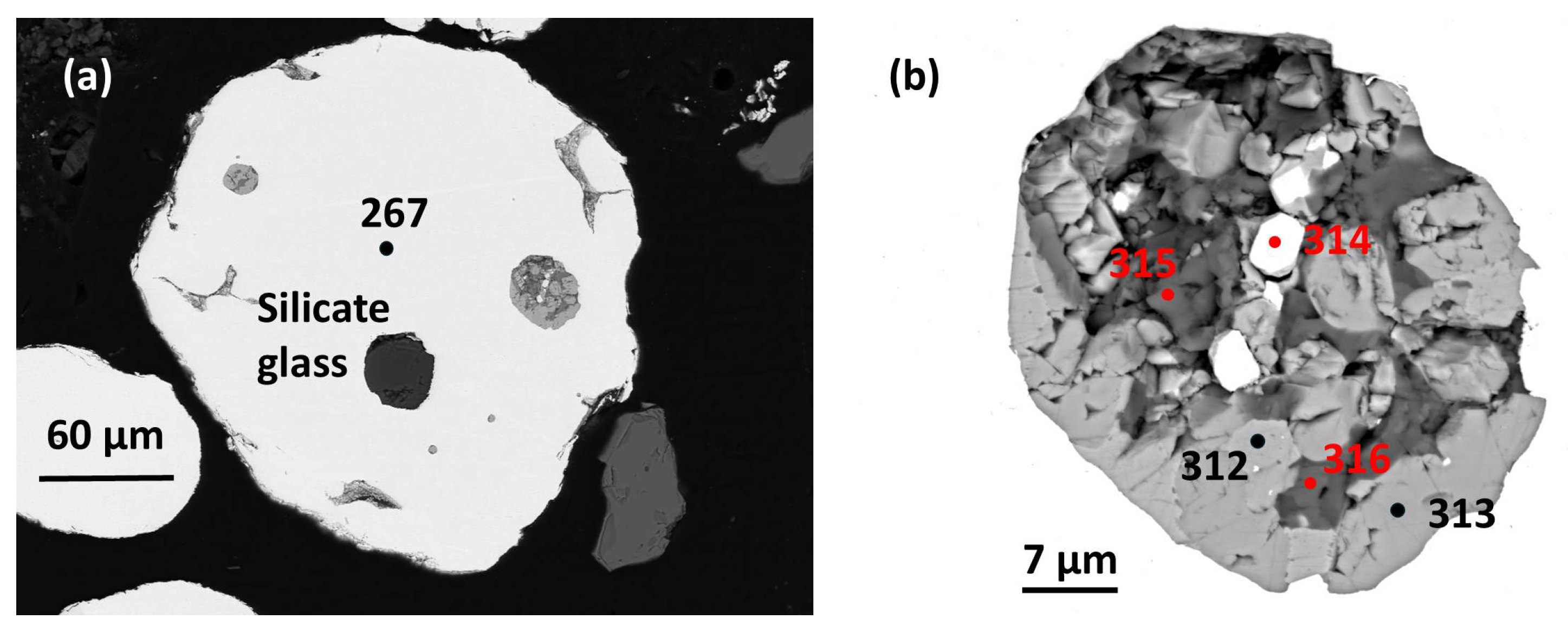

3.1.4. Sample A1 Area 9

a) Host alloy and basaltic andesite silicate glass (SiO2 52.75 wt. %).

The

host nugget for this sample is ~0.29 mm across. It is rounded and but is partly chipped and broken (

Figure 6a).

Analysis (267) (Barron

et al. [

1] Tables 1A and 1B and

Table 6, below) indicates isoferroplatinum (Pt

2.89Ir

0.04Pd

0.02Rh

0.02Os

0.01Ru

0.01)

2.99(Fe

0.88Cu

0.06Rh

0.06)

1.00 with minor Rh, Cu, Ir, Pd, Os and Ru.

Three inclusions are present (

Figure 6a). The first inclusion is slightly fractured, homogeneous silicate glass (~42.9 µm across) lacking coexisting exsolved PGMs. Two separate inclusions (~75-90 µm across and ~20 µm across respectively) have subrounded shapes with somewhat irregular margins and comprise melt inclusions with similar Cu-PGM sulfide parageneses. Three separate Cu-PGM sulfide ‘droplet’ shaped inclusions are minute (< 4 µm across).

Analysis 154 of the largest of two silicate glass inclusions indicates alkali-enriched basaltic andesite with SiO

2 52.75, FeO 10.54 and H

2O ~1.71 (wt. %) Barron

et al. [

1] Table 2E.

b) Cu-PGM sulfide paragenesis.

The texture of the largest PGM-bearing sulfide inclusion shows that subhedral crystals (up to ~ 10 µm) are set in anhedral interstitial minerals (

Figure 6b).

Pt-Fe alloy forms irregularly disseminated, sparse, small (up to ~6 µm) subhedral crystals, but this mineral is absent in the smaller inclusion in the plane of the present section.

Analysis 4(314) (

Table 6) indicates isoferroplatinum (Pt

2.75Pd

0.08Rh

0.05Os

0.01Cu

0.12Ni

0.01)

3.02Fe

0.99, with significantly high minor Pd, Cu, Fe and Ni and low concentrations of Rh and detectable S. This is distinct from the host alloy, analysis 1(267).

Cupororhodsite–(malanite) also forms subhedral crystals (some reaching >7 µm grain size) and accounts for ~40% of the inclusion area (

Figure 6b).

Analysis 3(313) (

Table 6) gives the following formula (Cu

0.69Fe

0.25Ni

0.06)

1.00(Rh

1.18Pt

0.54Ir

0.06Os

0.01Ru

0.01)

1.80S

4.00. This analysis is distinctly Me-deficient and contains an unusually high number (9) of detectable metal elements.

Vasilite (~20% of the inclusion area) forms anhedral to subhedral crystals (up to ~6 µm) interstitial to cupororhodsite–(malanite) above (

Figure 6b).

Analysis 2(312) (

Table 6) gives a slightly Me-deficient formula (Pd

11.77Cu

3.03Fe

0.11Ni

0.03Pt

0.02Rh

0.02)

14.99(S

6.97Se

0.02Te

0.01)

6.99.

Chalcopyrite is anhedral forming irregular interstitial patches (up to ~7 µm across). It accounts for ~ 20% of the relevant section area (

Figure 6b).

Analysis 5(315) (

Table 6) indicates 0.45 at. % PGE (Rh, Pt, Pd and Ir) and the calculated formula (Cu

0.89Fe

0.88Zn

0.02Pt

0.01Rh

0.01)

1.81S

2.00 suggests it is Me-deficient.

Pentlandite forms sparse anhedral patches intergrown with interstitial chalcopyrite (

Figure 6b).

Analysis 6(316) indicates the formula (Fe

4.37Ni

2.64Pd

0.61Cu

0.48Rh

0.23Co

0.06Zn

0.02Pt

0.01)

8.42S

8.00 [(Me)

9-xS

8, x=0.58]. It incorporates significant minor elements particularly Pd, Cu, and Rh.

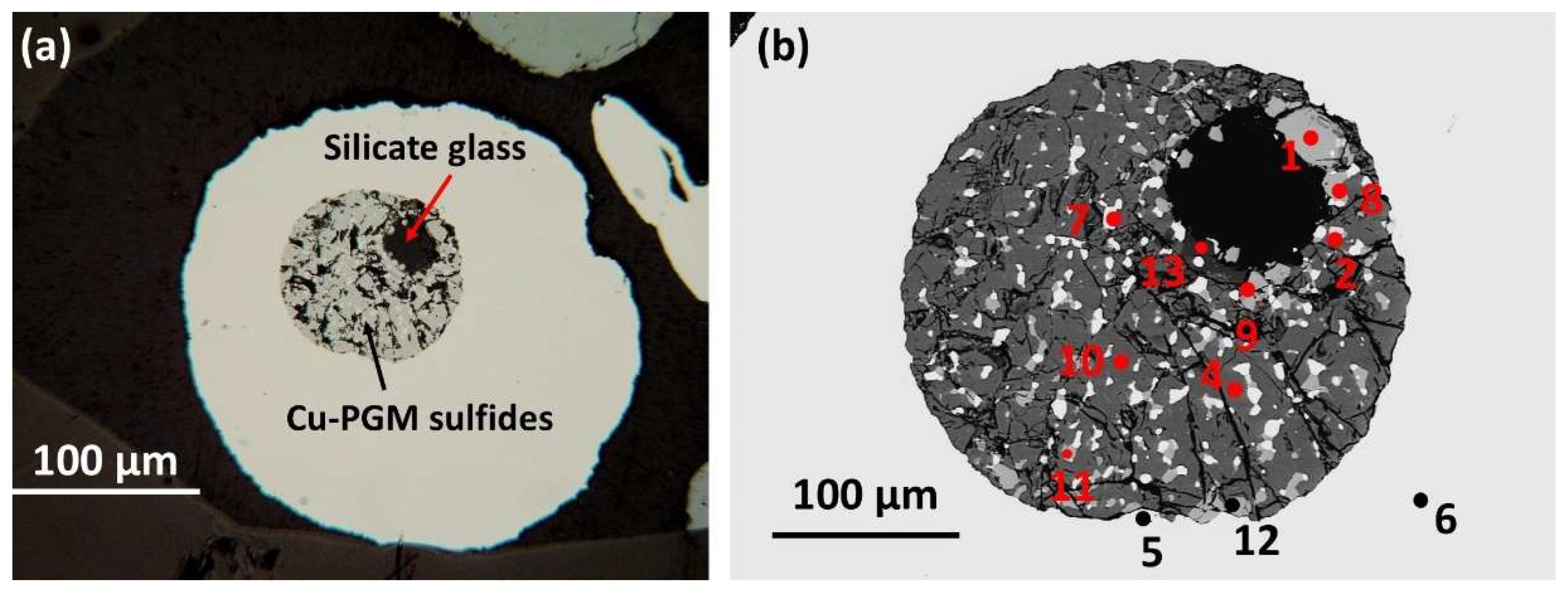

3.1.5. Sample B Area 5

a) Host alloy and andesite silicate glass (SiO2 59.89 wt. %).

The rounded

host nugget for this sample reaches ~0.4 mm across. It is isoferroplatinum (Pt

2.88Pd

0.01Rh

0.08Os

0.01Ir

0.02)

3.00(Fe

0.95Cu

0.05S

0.01)

1.01 with minor Rh, Cu, Pd, Ir, Os, Ni analysis 061, (Barron

et al. [

1] Tables 1A and 1B and

Table 8 below). A prominent round composite inclusion ~175 µm (~0.18 mm) across is not centrally located in the host nugget. It comprises a dominant rim of PGM enclosing a small rounded ‘pool’ (~ 50 µm across) of quenched silicate glass located near one margin of the PGM paragenesis (

Figure 7a,b).

Analysis of the silicate glass in this composite inclusion indicates

andesite with SiO

2 59.89, FeO 3.25 and H

2O ~1.06 (wt. %) (average of analyses Sp38, Sp39 and Sp40 (Barron

et al. [

1] Table 2D).

b) PGM sulfide paragenesis.

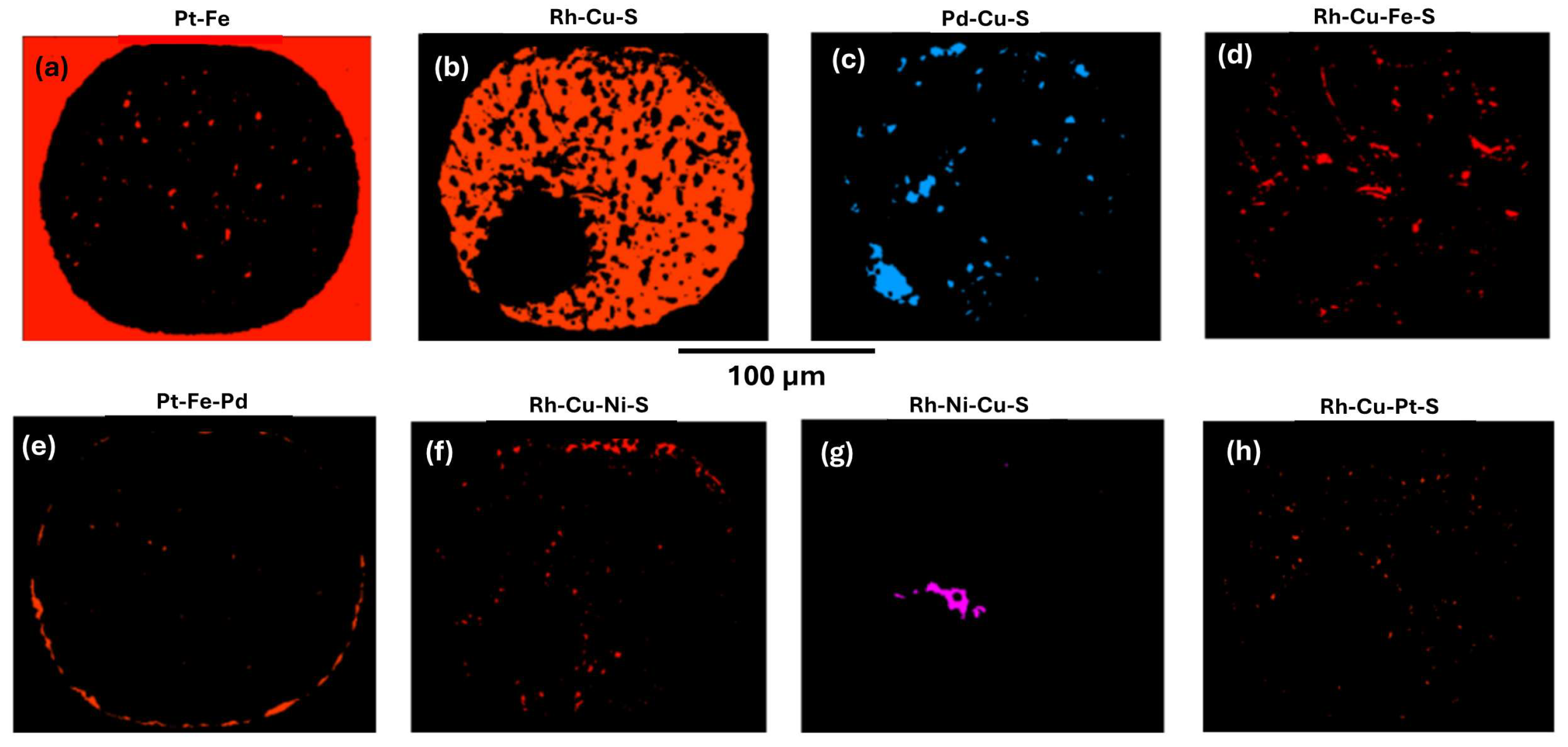

Phase mapping of the inclusion using EDS analyses and relative pixel counts for each phase indicates silicate glass is 6.72 fraction %. Eight minerals are identified in the PGM paragenesis (

Figure 8) and the normalised fraction % for each is as follows (fraction % is minus unassigned pixels); Pt-Fe alloy 4.98; Rh-Cu-S cuprorhodsite 80.25; Pd-Cu-S vasilite 4.98; Rh-Cu-Fe-S thiospinel 3.98; Pt-Fe-Pd alloy 2.59; Rh-Cu-Ni-S thiospinel 2.00; Rh-Ni-Cu-S thiospinel 1.00; Pd-Te keithconnite 0.20; and hematite 0.20.

An approximate calculated bulk chemistry based on EDS

element mapping of the PGM paragenesis is given in

Table 7. Order of major elements present is as follows Rh>>Cu>Fe>>Pd>Ni.

Table 7.

Sample B area 5 Calculated bulk chemistry droplet wt. % (minus silicates).

Table 7.

Sample B area 5 Calculated bulk chemistry droplet wt. % (minus silicates).

| S |

Fe |

Co |

Ni |

Cu |

Se |

Rh |

Pd |

Te |

Pt |

Total |

| wt. % |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 29.22 |

8.55 |

0.02 |

1.09 |

11.70 |

0.17 |

43.10 |

3.83 |

0.04 |

2.29 |

100.00 |

| at. % |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 52.48 |

8.82 |

0.02 |

1.07 |

10.60 |

0.12 |

24.12 |

2.07 |

0.02 |

0.68 |

100.00 |

| Me 47.52: S(+Se+Te) 52.62 = 0.90 at. % ~ S-saturated |

Table 8.

WDS analyses. Sample B Area 5.

Table 8.

WDS analyses. Sample B Area 5.

| wt. % |

S |

Fe |

Ni |

Cu |

Se |

Rh |

Pd |

Te |

Os |

Ir |

Pt |

Total |

| 6(061)◊Ifp Host |

0.04 |

8.31 |

0.03 |

0.50 |

|

1.22 |

0.17 |

|

0.18 |

0.64 |

88.29 |

99.40 |

| 1(063) PdCu Vs |

13.53 |

0.12 |

0.04 |

13.60 |

0.09 |

0.06 |

72.56 |

|

|

|

0.52 |

100.53 |

| 2(064)* PdTe Kei |

0.12 |

0.21 |

0.04 |

0.43 |

|

0.09 |

70.97 |

29.31 |

0.11 |

|

|

102.26 |

| 4-2(067)□ Crh |

33.07 |

5.96 |

0.26 |

8.54 |

0.19 |

51.12 |

|

|

|

1.17 |

1.68 |

102.01 |

| 5-2(069)† Ifp Rim |

0.04 |

9.75 |

0.27 |

1.36 |

|

0.65 |

11.24 |

|

0.13 |

|

75.94 |

99.54 |

| 7(070) PtFe Incl. |

0.08 |

9.17 |

0.10 |

1.27 |

|

2.87 |

2.57 |

|

0.14 |

|

84.68 |

100.88 |

| 9(071) PdCu Vs |

13.66 |

0.22 |

0.35 |

13.53 |

0.21 |

|

73.33 |

0.10 |

|

|

0.45 |

101.84 |

| 13^ Ms |

27.05 |

12.40 |

11.00 |

5.74 |

|

20.60 |

|

|

0.12 |

7.89 |

12.79 |

101.07 |

|

◊Co 0.02; *Sn 0.11, Sb 0.06, Pb, 0.45, Bi 0.87, Ag 0.10. □Co 0.02, † Au 0.16. ^As 0.1,Ru 0.07. |

| at. % |

S |

Fe |

Ni |

Cu |

Se |

Rh |

Pd |

Te |

Os |

Ir |

Pt |

Total |

| 6(061)◊ Ifp host |

0.18 |

23.65 |

0.07 |

1.24 |

|

1.89 |

0.26 |

|

0.15 |

0.53 |

71.96 |

100.00 |

| 1(063) PdCu Vs |

31.83 |

0.17 |

0.06 |

16.15 |

0.09 |

0.04 |

51.46 |

|

|

|

0.20 |

100.00 |

| 2(064)** Kei |

0.42 |

0.40 |

0.08 |

0.73 |

|

0.10 |

72.35 |

24.91 |

0.06 |

|

|

100.00 |

| 4-2(067) □ Crh |

57.55 |

5.94 |

0.26 |

7.51 |

0.14 |

27.67 |

|

|

|

0.33 |

0.59 |

100.00 |

| 5-2(069)††Ifp Rim |

0.19 |

24.78 |

0.66 |

3.03 |

|

0.90 |

14.99 |

|

0.10 |

|

55.23 |

100.00 |

| 7(070) Ifp Incl |

0.39 |

24.31 |

0.24 |

2.97 |

|

4.13 |

3.57 |

|

0.11 |

|

64.28 |

100.00 |

| 9(071) PdCu Vs |

31.71 |

0.29 |

0.44 |

15.84 |

0.20 |

|

51.29 |

0.06 |

|

|

0.17 |

100.00 |

| 13^ Ms |

51.05 |

13.43 |

11.34 |

5.46 |

|

12.11 |

|

|

0.04 |

2.48 |

3.97 |

100.00 |

|

◊Co 0.06. **Sn0.10, Sb0.06, Pb 0.23, Bi 0.45, Ag 0.11. □Co 0.02; †† Au 0.12. ^As 0.08, Ru 0.04. |

| apfu |

S |

Fe |

Ni |

Cu |

Se |

Rh |

Pd |

Te |

Os |

Ir |

Pt |

∑Me |

| 6(061) Ifp host |

0.01 |

0.95 |

|

0.05 |

|

0.08 |

0.01 |

|

0.01 |

0.02 |

2.88 |

4.01 |

| 1(063) PdCu ~Vs |

7.47 |

0.04 |

0.01 |

3.79 |

0.02 |

0.01 |

12.09 |

|

|

|

0.05 |

15.99 |

| 2(064)*** Kei |

0.11 |

|

0.02 |

0.20 |

|

0.03 |

19.60 |

6.75 |

0.02 |

|

|

19.93 |

| 4-2(067) Crh |

4.02 |

0.42 |

0.02 |

0.52 |

0.01 |

1.94 |

|

|

|

0.02 |

0.03 |

2.98 |

| 5-2(069)†††Ifp Rim |

|

1.00 |

0.03 |

0.12 |

|

0.04 |

0.60 |

|

|

|

2.21 |

4.00 |

| 7(070) Ifp Incl |

|

0.98 |

|

0.12 |

|

0.16 |

0.16 |

|

|

|

2.56 |

3.98 |

| 9(071) PdCu ~Vs |

7.44 |

0.07 |

0.10 |

3.72 |

0.05 |

|

12.03 |

0.01 |

|

|

0.04 |

16.01 |

| 13 Ms |

1.00 |

0.26 |

0.22 |

0.11 |

|

0.23 |

|

|

|

0.05 |

0.08 |

0.95 |

| ***Pb 0.06, Sn 0.03, Sb 0.02, Bi 0.12, Ag 0.03; †††Au 0.01. Ifp=isoferroplatinum; Crh=cuprorhodsite; Kei=keithconnite; Vs=vasilite; Ms=monosulfide mineral. Italics, semi-quantative analysis, small grain size cf. Nesterenko [20]. |

Cuprorhodsite (

Figure 7 and Rh-Cu-S in

Figure 8b) is the dominant mineral (80.25 fraction %) in this inclusion. It forms a spongy framework of skeletal to subhedral and elongate prisms showing partial radial structure away from the silicate ‘pool’. Some curved narrow cuprorhodsite crystals are intergrown with ~20 fraction % of all other finer grained patchy minerals.

Analysis 4-2(067)

Table 8 indicates (Cu

0.52Fe

0.42Ni

0.02)

0.96(Rh

1.94Ir

0.02Pt

0.03)

1.99(S

4.02Se

0.01)

4.03 and phase-mapped analysis 3(22)

Table 9 also indicates cuprorhodsite (Cu

0.56Fe

0.44)

1.02(Rh

1.91Ni

0.03Fe

0.02)

1.96(S

3.99Se

0.01).

Three additional Rh-thiospinel minerals (notably Pt deficient), are identified by chemical differences of element abundances in phase maps (using pixel counts) as follows:

(1) Rh-Cu-Fe-S thiospinel [red in

Figure 8d, analysis 14(33)

Table 9] fills some sub-parallel and curved grain boundaries and also marks the silicate/PGM boundary. It has an Fe-enriched composition (Cu

0.73Fe

0.27Ni

0.05)

1.05(Rh

1.76Fe

0.29)

2.05S

3.99. In this analysis after Rh (24.83 at. %), Cu and Fe have the highest concentrations (Cu 10.33 and Fe 7.83 at. %) while Ni (0.76 at. %) is a minor metal element. Thus this minor thiospinel is

ferrorhodsite cf. Cabri

et. al. [

19]. In

Figure 8d this mineral is fine grained with a patchy distribution and also defines some sub-parallel curving brittle fractures.

(2) Rh-Cu-Ni-S thiospinel is red in

Figure 8f, and

analysis 7(26)

Table 9 indicates it is

cuprorhodsite–(polydymite), (Cu

0.60Ni

0.17Fe

0.13)

0.90(Rh

1.86Ni

0.14)

2.00S

4.00. This mineral occurs along part of the rounded inclusion boundary with host Pt-Fe alloy. It also forms small blebs and partly defines minor fractures along the silicate glass boundary with the PGM sulfide fraction.

(3) Rh-Ni-Cu-S thiospinel is a well defined small anhedral pink mineral in

Figure 8g. It forms an irregular aggregate (~23 µm long) in the PGM paragenesis adjacent to the rounded silicate glass fraction.

Analysis 10(29)

Table 9 indicates

polydymite–(cuprorhodsite) (Cu

0.44Fe

0.30Ni

2+0.26)

1.00(Rh

1.40Ni

3+0.56)

1.96S

4.00 with significantly higher concentration of Ni than (2) above.

Vasilite [Pd-Cu-S

Figure 8c] also occurs as fine grained patches, but has an uneven distribution.

Analysis 1 (063) (

Table 8) indicates (Pd

12.09Cu

3.80Pt

0.05Fe

0.04Ni

0.01Rh

0.01)

16.00(S

7.48Se

0.02)

7.50.

The minor

monosulfide mineral (red specks in Rh-Cu-Pt-S

Figure 8h) occurs as small grains crystallised along mineral boundaries and fractures.

Analysis 11(30)

Table 9 indicates (Rh

0.42Pt

0.18Fe

0.16Cu

0.13Ni

0.02)

0.91S

1.00. The latter is Me-deficient.

Keithconnite and

hematite each account for only 0.2 fraction % of the PGM paragenesis. Keithconnite forms minor, very small anhedral patches similar to vasilite.

Analysis 2(064) (

Table 8) indicates keithconnite with formula (Pd

19.44Cu

0.20Fe

0.11Pb

0.06Rh

0.03Ag

0.03Os

0.02Ni

0.02)

19.94(Te

6.72S

0.11Bi

0.12Sb

0.02)

6.97. This has a remarkably high Me:S=2.86. Hematite occurs as wispy grains marking the boundary between the silicate and PGM fractions.

Analysis 16(35)

Table 9 indicates (Fe

1.95Ni

0.02Al

0.02Si

0.03)

2.02O

3.00S

0.03.

Minor

Pt-Fe alloy is approximately evenly distributed as fine grained (< ~5 µm across) anhedral patches (white in

Figure 7a,b and red Pt-Fe in

Figure 8a). A

nalysis 7(070)

Table 8 indicates isoferroplatinum (Pt

2.56Pd

0.16Rh

0.16)

2.98(Fe

0.96Cu

0.12)

1.08 with significant Pd 3.57 Rh 4.13 and Cu 2.97 (at. %) with detectable Ni. A second minor

Pt-Fe-Pd alloy (also red in

Figure 8e) forms a wisy discontinuous boundary with the host nugget.

Analysis 6(25) (

Table 9) indicates Pd- (and Cu) enriched isoferroplatinum [(Pt

2.24Pd

0.58Cu

0.14)

2.96Fe

1.04]

4.00.

3.1.6. Sample B Area 4

a) Host alloy and porphyritic dacitic/rhyolitic groundmass silicate glass (SiO2 70.67 wt. %).

The

host nugget for this sample is round (~0.48 mm diameter) but slightly irregular (

Figure 9).

Analysis 051 (Tables 1A and 1B of Barron

et al. [

1] and

Table 11 below). indicates isoferroplatinum (Pt

2.90Pd

0.04Ir

0.02Os

0.01)

3.05(Fe

0.88Rh

0.08Cu

0.05Ni

0.01S

0.01)

1.03 with FeO 22.09 (at. %) and minor Rh, Cu, Pd and Ir. It hosts a remarkable composite inclusion up to ~120 µm across with an unusual irregular, distinctly wavy outline (

Figure 9). The inclusion is located almost centrally in the host nugget. The central silicate fraction (~65 µm across) is rounded, except for an inward bulge. This fraction is

micro-porphyritic with subhedral amphibole and diopsidic clinopyroxene micro-phenocrysts set in chilled silicate glass of

dacite/rhyolite composition [

1].

Figure 9.

Sample B area 4. (

a) Platinum nugget with irregular (deflated) rim of PGM inclusion paragenesis exsolved from central silicate host with mafic phenocrysts and

dacite-rhyolite groundmass (black). Reflected light. (

b) WDS analysis points (

Table 10); 1, 2 vasilite; 3 cuprorhodsite; 5 vysotskite (1); 6 Rh-Pt-Cu-S cuprorhodsite; 7 vysotskite (1); 8 Pd-isoferroplatinum; 9 Pt-Fe alloy (EDS analysis); 10 vysotskite (2); 11 vysotskite (2).

Figure 9.

Sample B area 4. (

a) Platinum nugget with irregular (deflated) rim of PGM inclusion paragenesis exsolved from central silicate host with mafic phenocrysts and

dacite-rhyolite groundmass (black). Reflected light. (

b) WDS analysis points (

Table 10); 1, 2 vasilite; 3 cuprorhodsite; 5 vysotskite (1); 6 Rh-Pt-Cu-S cuprorhodsite; 7 vysotskite (1); 8 Pd-isoferroplatinum; 9 Pt-Fe alloy (EDS analysis); 10 vysotskite (2); 11 vysotskite (2).

Table 10.

Sample B area 4 Calculated bulk chemistry PGM (minus silicates).

Table 10.

Sample B area 4 Calculated bulk chemistry PGM (minus silicates).

| S |

Fe |

Ni |

Cu |

Rh |

Pd |

Os |

Ir |

Pt |

Te |

As |

Total |

| wt. % |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 18.10 |

7.04 |

1.90 |

3.48 |

12.20 |

37.50 |

0.07 |

0.72 |

14.42 |

4.54 |

0.04 |

100.00 |

| at. % |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 41.42 |

9.25 |

2.37 |

4.02 |

8.70 |

25.86 |

0.03 |

0.27 |

5.42 |

2.61 |

0.04 |

100.00 |

| Me:S (+ ligands) = 55.92:44.07 = 1.27 at. %. S-undersaturated. |

Table 11.

WDS analyses sample B area 4.

Table 11.

WDS analyses sample B area 4.

| wt. % |

S |

Se |

Fe |

Ni |

Cu |

Rh |

Pd |

Ag |

Os |

Ir |

Pt |

Total |

| (051)□ Ifp host |

0.04 |

|

7.72 |

0.05 |

0.47 |

1.32 |

0.65 |

|

0.22 |

0.62 |

88.55 |

99.77 |

| 1(052)† Vs |

13.45 |

0.14 |

0.06 |

0.03 |

12.70 |

0.08 |

74.29 |

0.17 |

|

|

0.31 |

101.39 |

| 2(055) Vs |

13.49 |

0.06 |

0.13 |

0.04 |

12.67 |

|

74.26 |

0.08 |

|

|

0.51 |

101.23 |

| 3(056)* Crh |

31.22 |

|

2.38 |

0.75 |

10.83 |

37.47 |

0.06 |

|

0.15 |

3.08 |

16.15 |

102.17 |

| 5(058) Vys (1) |

21.34 |

|

0.10 |

2.10 |

0.12 |

0.23 |

31.91 |

|

|

|

44.82 |

100.61 |

| 7(059) Vys (1) |

22.54 |

|

0.05 |

3.10 |

|

0.15 |

38.51 |

0.07 |

|

|

36.78 |

101.20 |

| 8(060)◊ Ifp |

0.07 |

|

9.14 |

0.35 |

0.62 |

0.43 |

6.77 |

|

0.10 |

|

83.25 |

100.83 |

| 10(053)^ Vys (2) |

23.96 |

0.32 |

0.11 |

4.17 |

0.09 |

0.07 |

52.77 |

|

|

|

19.54 |

101.07 |

| 11(054) Vys (2) |

23.92 |

0.27 |

0.08 |

4.14 |

|

0.08 |

55.25 |

|

|

|

17.40 |

101.13 |

|

□Pb 0.14; †Te 0.06, Bi 0.09; *Co 0.08; ◊Ru 0.10; ^Te 0.05. |

|

|

| at. % |

S |

Se |

Fe |

Ni |

Cu |

Rh |

Pd |

Ag |

Os |

Ir |

Pt |

Total |

| (051) Ifp host |

0.21 |

|

22.09 |

0.15 |

1.18 |

2.05 |

0.98 |

|

0.19 |

0.51 |

72.56 |

100.00 |

| 1(052) †† ~Vs |

31.65 |

0.14 |

0.08 |

0.04 |

15.07 |

0.06 |

52.66 |

0.12 |

|

|

0.12 |

100.00 |

| 2(055) ~Vs |

31.75 |

0.06 |

0.17 |

0.05 |

15.04 |

|

52.67 |

0.05 |

|

|

0.20 |

100.00 |

| 3(056)** Crh |

58.47 |

|

2.56 |

0.77 |

10.23 |

21.87 |

0.04 |

|

0.05 |

0.96 |

4.97 |

100.00 |

| 5(058) Vys (1) |

53.81 |

|

0.14 |

2.89 |

0.15 |

0.18 |

24.15 |

|

|

|

18.58 |

100.00 |

| 7(059) Vys (1) |

53.69 |

|

0.07 |

4.04 |

|

0.11 |

27.65 |

0.05 |

|

|

14.40 |

100.00 |

| 8(060)◊ Ifp |

0.32 |

|

24.15 |

0.88 |

1.45 |

0.62 |

9.38 |

|

0.08 |

|

62.98 |

100.00 |

| 10(053) ^^Vys (2) |

52.52 |

0.28 |

0.14 |

4.99 |

0.10 |

0.05 |

34.86 |

|

|

|

7.04 |

100.00 |

| 11(054) Vys (2) |

52.15 |

0.24 |

0.10 |

4.93 |

|

0.05 |

36.30 |

|

|

|

6.23 |

100.00 |

|

□Pb 0.11; ††Te 0.04, Bi 0.03; **Co 0.08; ◊Ru 0.14; ^^Te 0.03. |

|

|

|

| apfu |

S |

Se |

Fe |

Ni |

Cu |

Rh |

Pd |

Ag |

Os |

Ir |

Pt |

Me |

| (051) Ifp host |

0.01 |

|

0.88 |

0.01 |

0.05 |

0.08 |

0.04 |

|

0.01 |

0.02 |

2.90 |

4.00 |

| 1(052)††† Vs |

6.97 |

0.03 |

0.02 |

0.01 |

3.32 |

0.01 |

11.60 |

0.03 |

|

|

0.03 |

15.03 |

| 2(055) Vs |

6.99 |

0.01 |

0.04 |

0.01 |

3.31 |

|

11.60 |

0.01 |

|

|

0.05 |

15.02 |

| 3(056)*** Crh |

4.00 |

|

0.18 |

0.05 |

0.70 |

1.50 |

|

|

|

0.07 |

0.34 |

2.85 |

| 5(058) Vys (1) |

1.00 |

|

|

0.06 |

|

|

0.40 |

|

|

|

0.31 |

0.77 |

| 7(059) Vys (1) |

1.00 |

|

|

0.08 |

|

|

0.52 |

|

|

|

0.27 |

0.87 |

| 8(060)◊ Ifp |

|

|

0.97 |

0.04 |

0.06 |

0.03 |

0.38 |

|

|

|

2.52 |

4.02 |

| 10(053) Vys (2) |

0.99 |

0.01 |

|

0.09 |

|

|

0.66 |

|

|

|

0.13 |

0.90 |

| 11(054) Vys (2) |

1.00 |

|

|

0.09 |

|

|

0.67 |

|

|

|

0.12 |

0.88 |

|

†††Te 0.01; ***Co 0.01; ◊Ru 0.01. Crh=cuprorhodsite; Ifp= isoferroplatinum; Vs=vasilite Vys=vysotskite. |

Analysis of the groundmass silicate glass indicates

dacite-rhyolite with SiO

2 70.67, very low FeO 0.24, and H

2O ~2.17 (wt. %), average of analyses (004) and (005),

Table 3 of Barron et al. [

1].

b) PGM sulfide paragenesis.

The

PGM paragenesis forms a ‘rim’ of variable thickness (about ~5 µm up to ~50 µm) around the almost centrally located silicate ‘pool’,

Figure 9(a, b). This assemblage comprises an irregularly intergrown aggregate of anhedral grains > 60 µm across.

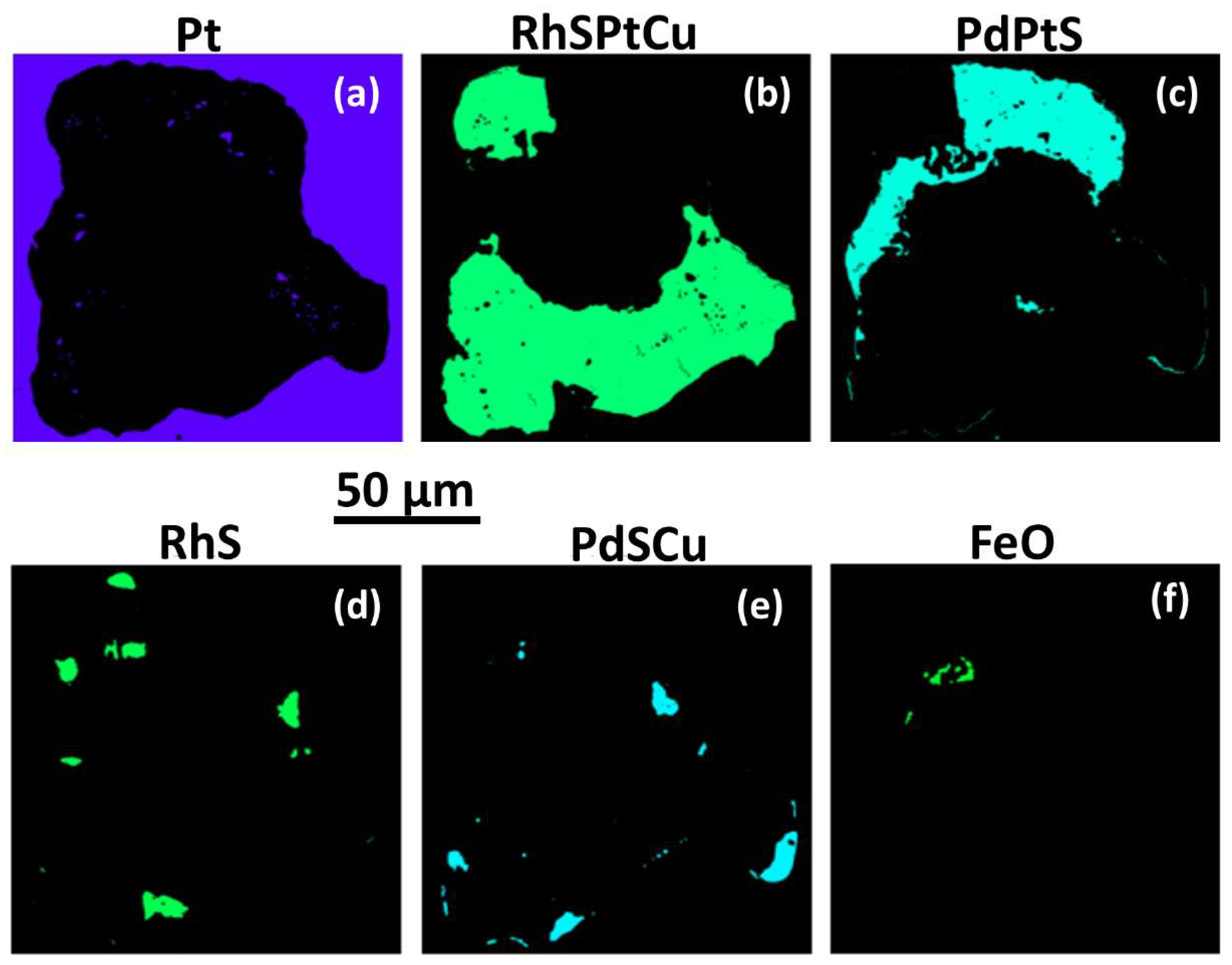

Phase mapping (

Figure 10) gives an approximate fraction % for each mineral present (based on relative pixel counts using EDS analysis and BSE imaging minus unassigned pixels). The PGM fraction accounts for 77.8 fraction % of the inclusion, while the exsolved silicate fraction is 22.2 fraction % of the inclusion area. An approximate

normalised modal mineralogy for the PGM fraction is as follows (fraction %) (a) Pt-Fe alloy ~1.5; (b) cuprorhodsite 65.3; (c) braggite (and subordinate Ni-vysotskite) 25.6; (d) bowieite 3.6; (e) vasilite 3.6; and UM (unnamed mineral) 0.42. PdTeSRh, is a sulfide-telluride analogue of palladoarsenide (Pd

2As).

An approximate calculated bulk chemistry (

Table 10) is based on EDS

element mapping of the PGM paragenesis.

Pt-Fe alloy forms small clusters of purple grains (Pt,

Figure 10a) in the PGM sulfide paragenesis fraction. Pt-Fe alloy set in cuprorhodsite (

Figure 9b) is Rh-enriched isoferroplatinum (Pt

2.94Rh

0.06)

3.00(Fe

0.85Rh

0.16)

1.01 (EDS analysis 9Ifp,

Table 11). In contrast, Pt-Fe alloy set in vysotskite is Pd rich isoferroplatinum (Pt

2.52Pd

0.38Rh

0.03Ru

0.01)

2.94 (Fe

0.97Cu

0.06Ni

0.04)

1.07 analysis 8(060),

Table 11,

Figure 9(c).

Cuprorhodsite (Rh-Cu-Fe-S, green in

Figure 10b) is the dominant mineral in this inclusion and occurs as two anhedral domains; the largest is ~ 0.15 mm across.

Analysis 3(056)

Table 11 indicates cuprorhodsite–(malanite) (Cu

0.72Fe

0.18Ni

0.05Co

0.01)

0.96(Rh

1.53Ir

0.07Pt

0.35)

1.92S

4.00 (Me-deficient).

Vysotskite (1) (Vys, turquoise in

Figure 10c) occurs as irregular large patches that are pale grey in

Figure 9b.

Analysis 5(058)

Table 11 gives Pd 24.15 and Pt 18.58 with 3.36 (at. %) minor elements (Cu, Fe, Rh, Ni and Os). It has slightly high S. Analysis 5(059) is similar. Minor

vysotskite (2) is slightly darker grey in

Figure 10. Analyses 10(053) and 11(054)

Table 11, are more Pd- and Ni-enriched with lower Pt.

Bowieite (RhS, green in

Figure 10d) occurs as irregular small patches, at margins of cuprorhodsite.

EDS a

nalysis 5RhS (

Table 12) gives the following empirical formula (Rh

1.73Pd

0.13Ir

0.05Pt

0.04Os

0.01Cu

0.05Ni

0.02Fe

0.02)

2.05S

3.00.

Vasilite (PdSCu in

Figure 10e) forms sparse anhedral patches along margins of the irregular inclusion. The average of three analyses [1(052), 2(055) and 9(053)

Table 11] give similar formulae.

Analysis 2(055) gives (Pd

11.60Cu

3.31Pt

0.05 Ag

0.01Fe

0.04Ni

0.01)

15.02(S

6.99Se

0.01)

7.00. This is slightly Me-deficient and Me:S=~2.15.

Hematite (FeO in

Figure 10f) occurs as a small (10 µm) cluster of anhedral grains as inclusions in vysotskite (2).

EDS analysis 17FeO (

Table 12) is ~Fe

2O

3.

An UM

(unnamed mineral) (PdTe) occurs as eight very small (up to ~3 µm) grains located mainly along the boundary of the PGM sulfide fraction with the silicate fraction.

EDS analysis 18PdTe (

Table 12) indicates (Pd

1.79Pt

0.11Ni

0.07Cu

0.03)

2.00(S

0.56Te

0.48As

0.01)

1.05. It is a Pd-dominant sulfide-telluride analogue of palladoarsenide (Pd

2As) and possibly naldrettite (Pd

2Sb).

The PGM paragenesis in this inclusion is dominated by cuprorhodsite with significant intergrown irregular patches of vysotskite (1) and subordinate vysotskite (> Ni) (2), minor bowieite, and minor vasilite. Pt-Fe alloy is unevenly distributed as fine grained (< ~5 µm across) anhedral (exsolved) patches in both cuprorhodsite and vysotskite (1) but is lacking from vysotskite (2) (

Figure 9b and

Figure 10a). ‘Sprays’ of Pt-Fe alloy inclusions define exsolutions in cuprorhodsite in

Figure 9b. Pt-Fe-Pd alloy also forms a wisy discontinuous boundary with the host nugget. Vasilite occurs as similar fine grained patches, but has an uneven distribution.

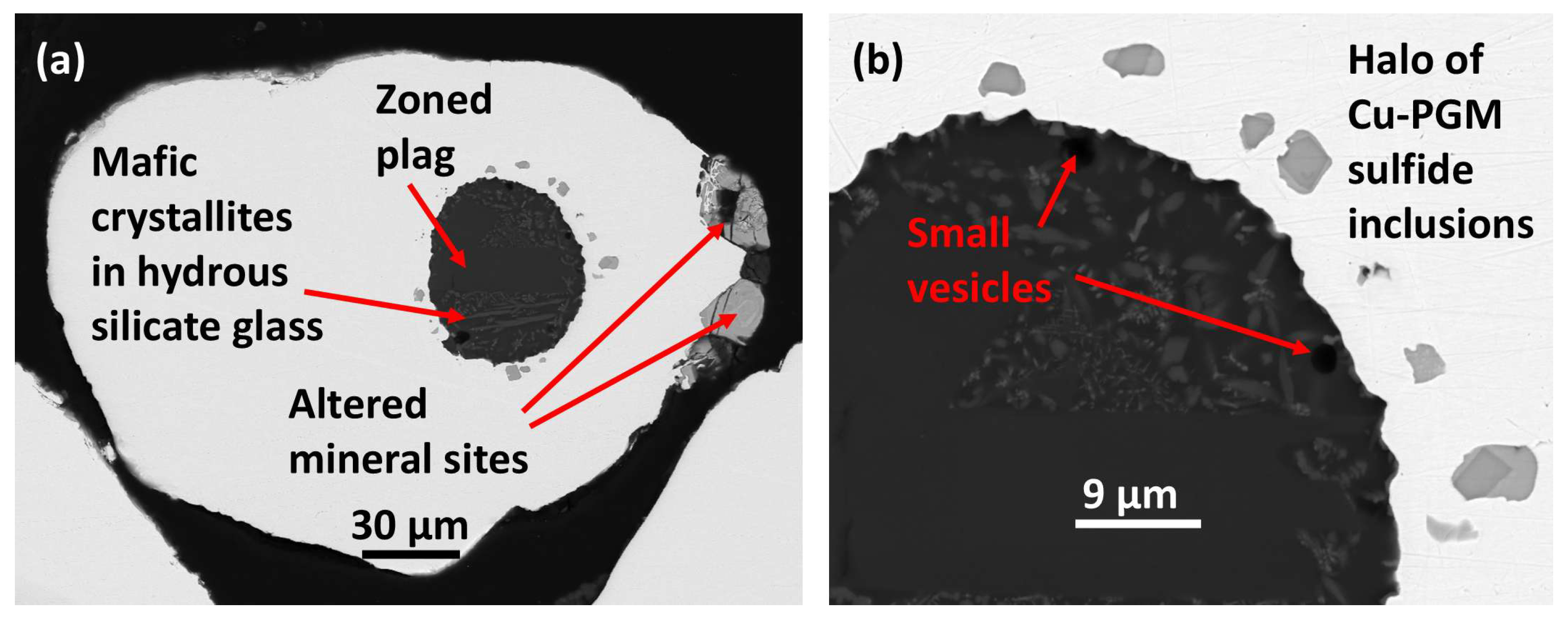

3.1.7. Sample A1 Area 7

a) Host alloy and porphyritic rhyolitic groundmass silicate glass (SiO2 70.31 wt. %).

The small (~0.26 mm across)

host nugget is partly rounded with some subhedral-shaped indents filled with alteration products suggesting previous coexisting crystal sites (

Figure 11a).

Analysis 1(264) (Tables 1A and 1B of Barron et al. [

1] and

Table 13 below) indicates Pd and Rh-enriched

native platinum (Pt

2.83Pd

0.12Rh

0.12Ir

0.10Os

0.02Ru

0.01Fe

0.68 Cu

0.13)

4.01.

An exceptional oval shaped

silicate inclusion (about 65 µm across) with a finely scalloped margin is located towards one side of the host alloy. Plagioclase prisms, skeletal mafic-(possibly amphibole) microlites and minor wispy oxides are set in chilled silicate glass with SiO

2 70.31 and significant H

2O ~ 4.23 wt. % (Barron et al. [

1] analyses 145 and 147,

Table 4). Significant quench textures are small, gas/volatile vesicles at the silicate droplet margin, near to ejection into host alloy. A prismatic plagioclase phenocryst is normally compositionally zoned, with a calcic core of bytownite suggesting a picrobasaltic or picritic primitive parent melt and sustained fractionation [

1].

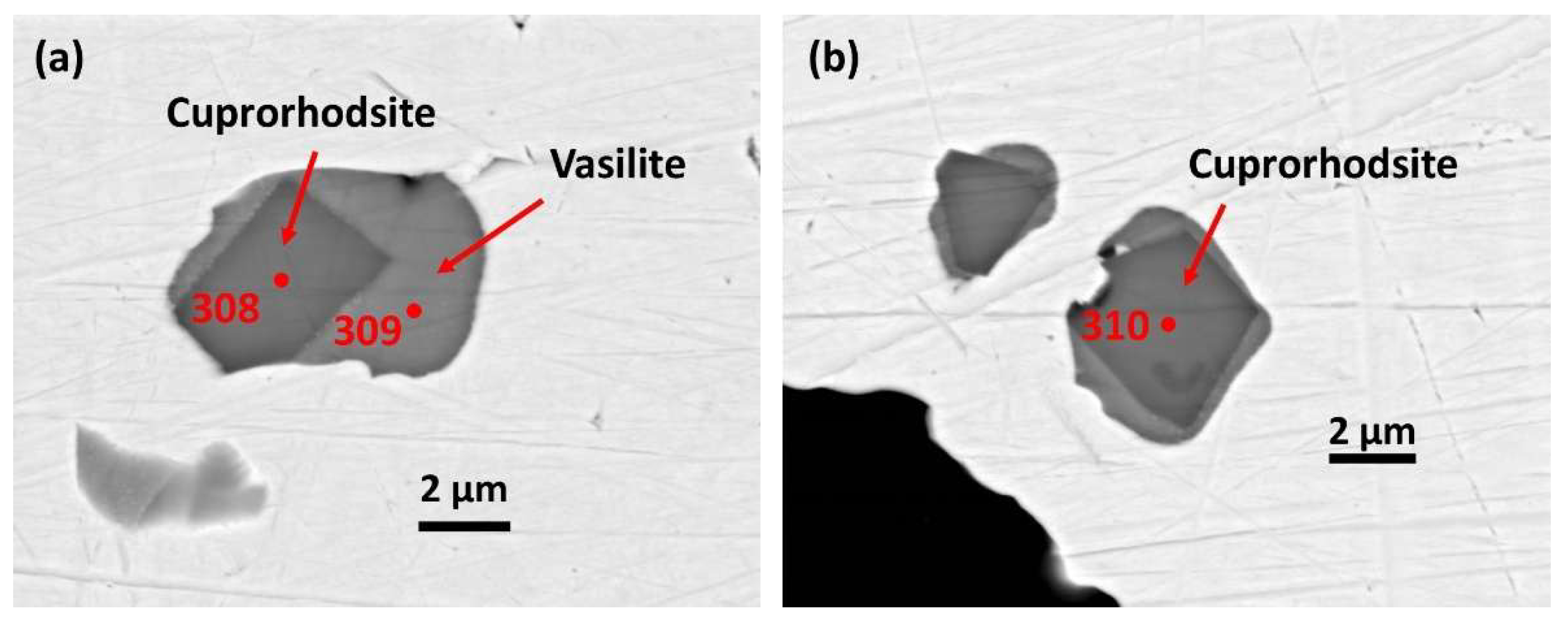

b) PGM sulfide paragenesis.

The PGM sulfide paragenesis comprises 18 small inclusions (mainly < 7 µm across) forming a ‘halo’ within the host Pt-Fe alloy adjacent to the silicate inclusion; up to ~14 µm from the scalloped silicate inclusion margin,

Figure 11b. They are not in contact with the silicate fraction (

Figure 11a). Each PGM paragenesis is simple, comprising a euhedral crystal of cuprorhodsite set in vasilite (

Figure 12a,b).

Cuprorhodsite crystals reach ~4.5 µm long and ~2.7 µm across.

Analysis 2(308) Rh-Pt-Cu-S (

Table 13) gives the following formula (Cu

0.80Fe

0.08Ni

0.03)

0.91(Rh

1.42Pt

0.39Ir

0.09Ru

0.01Os

0.01)

1.92S

4.00 (Me-deficient, Me:S=0.71) indicating cuprorhodsite-(malanite) with minor Fe and Ni.

Analysis 4(310) in a separate inclusion gives the similar formula (Cu

0.80Fe

0.08Ni

0.03)

0.91(Rh

1.40Pt

0.39Ir

0.08Ru

0.01Os

0.01)

1.89S

4.00 (also Me-deficient Me:S=0.70).

Vasilite is anhedral and forms a matrix for the cuprorhodsite crystals in each inclusion above.

Analysis 3(309) Pd-Cu-S (

Table 13) indicates (Pd

11.25Rh

0.13Pt

0.12Ag

0.05Cu

3.82Fe

0.05Ni

0.01)

15.42(S

6.96As

0.03Se

0.01)

7.00 (Me:S=2.20), with significant Rh and Pt. Additional ligands are detectable As and Se.

We calculate the approximate inclusion bulk chemistry (

Table 14) for the Cu-PGM sulfide fraction in the present sample using the simple ore mineralogy of cuprorhodsite and almost equally abundant vasilite (

Figure 12a). Order of major elements present is as follows Rh >>Cu>Fe>>Pd>Ni.