Submitted:

04 November 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC: Primary: 26A15; Secondary: 26-01; 26-02; 54C05; 26A30; 97I40

1. Introduction

1.1. Historical Background

1.2. Taxonomy

- Function family (what is f?). Linear/affine; power and root (with domain caveats); polynomials; rational (poles vs. removable points distinguished); exponential and logarithmic; trigonometric and inverse trigonometric; hyperbolic and inverse hyperbolic; absolute value and ; piecewise/defined-by-cases; and selected “pathological” exemplars (Thomae, Weierstrass, Cantor function) where local continuity is instructive.

- Point type (where is continuity checked?). Interior points; boundary points of the domain (one-sided neighborhoods); removable singularities (limit exists and can be defined); and, for contrast, essential/jump points when documenting discontinuity.

- Proof structure (how do we construct ?). The scratch-work ⇒ formal-proof pipeline; backwards–forwards organization; factor–bound–squeeze schemes (e.g., factor , bound a cofactor by C, set ); squeeze and triangle-inequality templates; and contradiction patterns for discontinuity.

- Quantitative strength of continuity. Pointwise continuity (); uniform continuity on a set (); Lipschitz/Hölder cases (explicit such as ); and modulus of continuity with .

- Bounding toolkits (reusable inequalities). Algebraic: , ; power/Bernoulli-type bounds for ; trigonometric bounds , ; elementary exponential/logarithmic bounds; rational bounds via denominator lower bounds on punctured neighborhoods.

- Dependence of on parameters. (i) on a set (uniform continuity); (ii) (continuity at only); (iii) parameterized families : continuity in x at fixed vs. joint continuity in .

- Topological reformulations.–⟺ preimage of open sets is open; sequential characterization (). Recorded for completeness; the atlas emphasizes constructive .

- Role of the function space . Continuity-preserving operators: finite sums/products/scalar multiples/quotients (away from zeros), composition, , absolute value; compact-set principles (e.g., uniform limits preserve continuity); and metrics/topologies on (pointwise vs. uniform) to situate when a single exists. General theorems/schemata are stated here and instantiated by the examples.

- Piecewise construction and junction analysis. (a) Continuity on each piece, (b) existence of one-sided limits at breakpoints, and (c) agreement with the function value.

- Discontinuity taxonomy (for contrast). Removable, jump, and essential discontinuities, including oscillatory counterexamples, to delineate the scope of the methods.

1.3. Motivation and Scope

Audience and Objectives

Benefits for Students

- Direct method first. Each argument begins with the – definition, revealing where the core difficulty arises and how to neutralize it.

- Minimal prerequisites. Proofs rely on basic algebra and a concise catalogue of equalities and inequalities.

- Reusable schemata. Standard proof schemes and patterns (e.g., factor-and-bound, local uniform bounds on cofactors, and “” closures) are made explicit and portable across examples.

- Confidence building. Worked examples progress in difficulty, helping students transition from imitation of templates to independent problem solving.

- Centralized reference. Results that are typically scattered across chapters and sources are presented in one place for quick comparison and review.

Benefits for Instructors

- Classroom-ready exemplars. Short, fully rigorous proofs suitable for board work or slides, with clearly marked bounding steps.

- Varied demonstrations. Multiple routes to a result (algebraic techniques, alternative equalities, alternative inequalities, or different local bounds) support adaptive instruction.

- Assessment alignment. The proofs decompose naturally into graded checkpoints (e.g., problem framing, bounding choice, construction, and quantifier closure).

- Curricular integration. Side-by-side treatments under different methods and perspectives (e.g., pointwise vs. uniform) make abstract distinctions concrete.

- Economy of time. Concise arguments minimize in-class derivation length without sacrificing logical completeness.

Benefits for Independent Learners

- Self-paced progression. Topics are sequenced from elementary to advanced, with clearly marked prerequisites and optional extensions.

- Diagnostic checkpoints. Each proof highlights the key steps and decision points (e.g., choice of cofactor g, selection of bounds, calibration of C) to encourage metacognitive practice.

- Template portability. Reusable schemata (e.g., factor-and-bound, local bounding, closure) are summarized for adaptation to new functions.

- Minimal toolkit. Only basic algebra and a compact list of equalities and inequalities are assumed, lowering the barrier to independent entry.

- Cross-Scheme insight. Parallel treatments under different proof schemes and methods promote conceptual transfer beyond single-problem techniques.

Benefits for Mathematicians

- Technique extraction. The proofs isolate recurring schemes, steps and bounding moves that may generalize to broader and more abstract classes in and related spaces.

- Metric sensitivity. Side-by-side comparisons under distinct methods and perspectives highlight where continuity is stable and where it fails, suggesting avenues for characterization results.

- Problem generation. Tight bounds, extremal examples, and borderline cases naturally motivate conjectures recorded in the open-problems section.

Pedagogical Benefits

Research Component and Open Problems

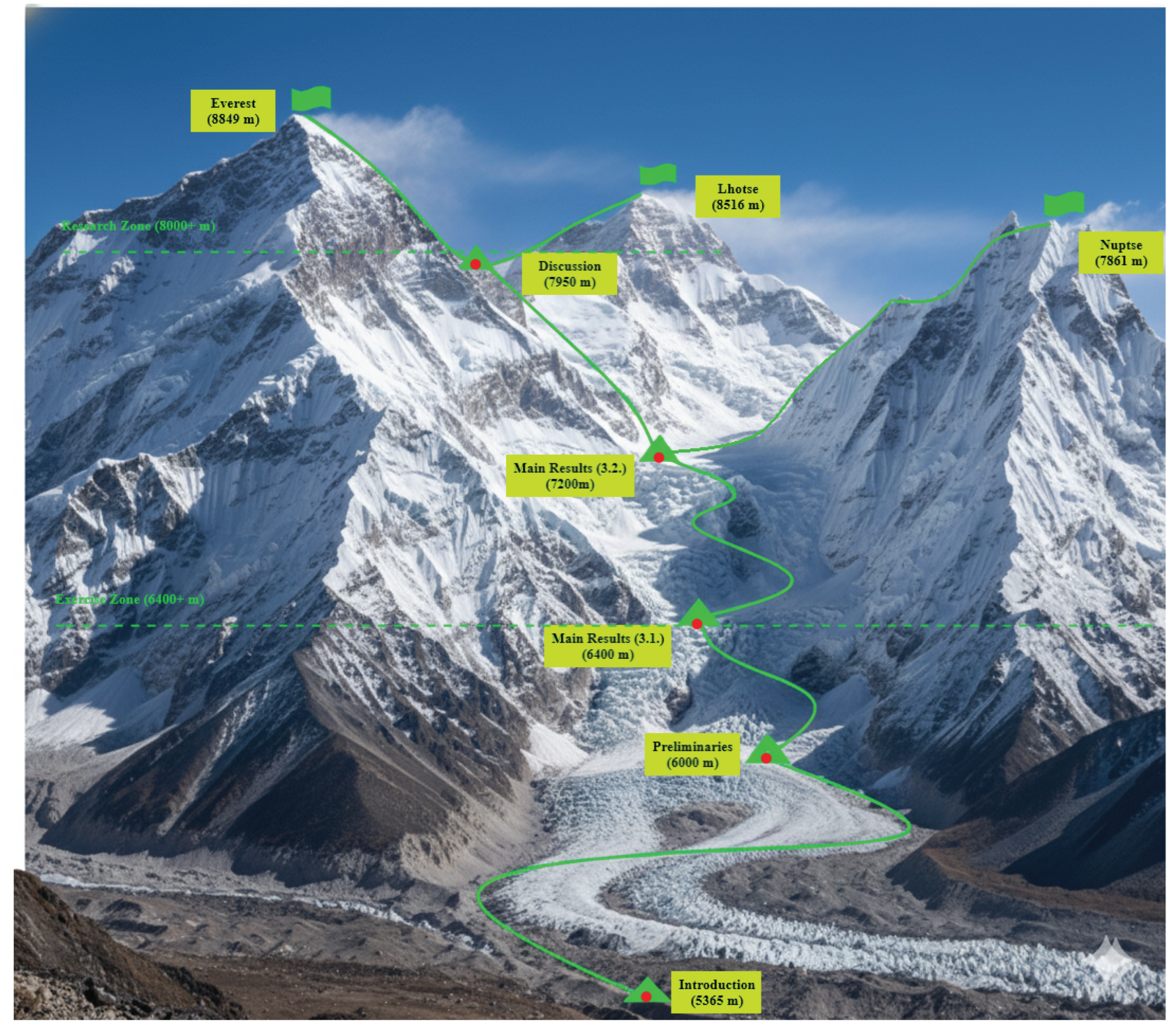

1.4. Outline of the Paper

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Foundations

2.1.1. Definitions

- Type I Dirichlet function: and .

- Type II Dirichlet function:(for some ) and .

- Type III Dirichlet function: and .

- Type IV Dirichlet function: and .

2.1.2. Proof Workflow and Schemes

- Given an , find a .

- Start with the inequality and work backward to find a relationship between and ϵ.

- Show that choosing δ based on this relationship guarantees the original inequality holds.

2.2. Auxiliary Equalities and Inequalities

2.2.1. Auxiliary Equalities

- General Product Decomposition (GPD).For any integer and elements ,

- Difference of Powers Factorization (DPF).For any and integer ,

- Max/min Recursive.For any

- Max/min via absolute value.For any

- Trigonometric subtraction (sum–to–product).For any

- Hyperbolic subtraction properties.For any

2.2.2. Auxiliary Inequalities

- Generalized triangle inequality.

- Two–Sided Bernoulli Power Bounds(TSBPB).For any and ,

- Reverse triangle inequality.For any

- Symmetric-anti Symmetric inequality.For any and

- Chord–arc bound for sine.For any

- Distance reverse triangle inequality .For any

3. Main Results

3.1. Stability of Continuity Under Algebraic Operations

- (a)

- the Arithmetic Mean:

- (b)

- the Geometric Mean:

- (c)

- the Harmonic Mean:

- (a)

- A modification of above proof for the maximum function can be applied for the epsilon-delta continuity proof of minimum function .

- (b)

- A modification of above counterexample for the maximum function can be applied for the associated counterexample of minimum function .

3.2. Atlas of Epsilon-Delta Continuity Proofs

3.2.1. Algebraics

- (a)

- the basic form polynomials (constant, linear, quadratic, cubic),

- (b)

- special families of orthogonal polynomials (Legendre, Chebyshev, Hermite, Laguerre, Bernoulli, Euler),

- (c)

- the Cyclotomic polynomials,

- (d)

- the Minimal polynomials,

- (e)

- the Smoothstep function (),

- (f)

- the base Logistic map ().

- (a)

- the integer powers (e.g., )

- (b)

- the rational powers (e.g., )

- (a)

- (b)

- (c)

- (d)

- (a)

- the Möbius (linear fractional) functions (),

- (b)

- the Quadratic-over-linear rationals,

- (c)

- the Cubic-over-quadratic rationals,

- (d)

- the Runge function (),

- (e)

- the Hill function ().

3.2.2. Exponential & Logarithmic Family

- (a)

- the bump function (),

- (b)

- the standard normal density (),

- (c)

- the Softplus function (),

- (d)

- the standard logistic function (),

- (e)

- the logit map ().

3.2.3. Trigonometrics

-

Accordingly, it is sufficient to take:

-

Let and fix By equation () and inequality (30) it follows that:Accordingly, it is sufficient to take:

-

Let and fix First, using equality () and inequality (30) it follows that:Second, set Since is continuous at by equation (93) there is such that for all with we have As before, an application of reverse triangle inequality (28) yields This latest inequality implies or equivalently:Finally, is given by:

-

Let and fix First, using equality () and inequality (30) it follows that:

-

Let and fix First, using equality () and inequality (30) it follows that:

-

Let and fix First, using equality () and inequality (30) it follows that:

- (a)

- the Haversine function ().

3.2.4. Inverse-Trigonometrics

-

Let and fix Then, for all by a series of algebraic operations we have:Now, using Symmetric-anti Symmetric inequality (29) it is sufficient to consider:

-

Let and fix Then, for all by a series of algebraic operations we have:Now, using Symmetric-anti Symmetric inequality (29) it is sufficient to consider:

- Let and fix Then, by similar proof to the case of with sin replaced by tan, and arcsin replaced by arctan, respectively, we have:

- Let and fix Then, by similar proof to the case of with cos replaced by cot, and arccos replaced by arccot, respectively, we have:

- Let and fix Then, by similar proof to the case of with sin replaced by sec, and arcsin replaced by arcsec, respectively, we have:

- Let and fix Then, by similar proof to the case of with cos replaced by csc, and arccos replaced by arccsc, respectively, we have:

- (a)

- (b)

- (c)

- (d)

- (e)

- (f)

3.2.5. Hyperbolics

-

Let and fix We accomplish the proof in few steps:Step 1. (Upper Bound Representation). By definition:Step 2. (Neighborhood Approximations). Given Define and By continuity of at the point and, at the point there are and respectively, such that for all whenever we have , and, whenever we have , respectively. Equivalently:Step 3. (The delta Assessment). Let Then, combining inequalities (112)-() we have:Finally, the formula of via two times application of equation (69) for and , respectively, is given by:

- Let and fix Then, given that a similar proof for above presented proof for the case of applies. Hence:

-

Let and fix By definition, and equalities (23), () and lower bound of 1 for the function it follows that:Now, it is sufficient to take:Then, by (118) we have:

-

Let and fix By definition, and lower bound of 1 for the function it follows that:So any that makes also makes . In this way the continuity of sech at is “dominated’’ by (indeed, follows from) the continuity of cosh at . Hence, it is sufficient to take:

-

Let and fix We accomplish the proof in few steps:Step 1.(Upper Bound Representation). By definition and equalities (23), ():Step 2.(Neighborhood Approximation). Set Since is continuous at , by equation (116) there is such that for all with we have As before, an application of reveres triangle inequality (28) yields This latest inequality implies or equivalently:Step 3. (The delta Assessment). Combining the equality (123) and inequality (124), and considering for all with we have:Finally, is given by:

-

Let and fix The proof is essentially similar to he previous proof with some minor modifications as follows. First, the equation (123) is replaced by:Second, for the same and inequality (124) holds. Third, considering for all with we have:Finally, is given by:

3.2.6. Inverses-Hyperbolics

- (a)

- (b)

- (c)

- (d)

- (e)

- (f)

3.2.7. Elementary Piecewise functions

-

Let and fix Using Reverse triangle inequality (28) we have:Accordingly, by (136) it is sufficient to set:

-

Accordingly, by (138) it is sufficient to set:

-

Let fix Then, using equality ( ) and inequality (28) and similar to the process above, we have:Accordingly, by (140) it is sufficient to set:

-

Accordingly, by (142) it is sufficient to set:

-

Let fix Set Then:Next, from inequality (144), it follows that if then , and, if then Hence, in both cases or equivalently: Consequently, it is sufficient to set:

-

Let fix Set Then:Next, from inequality (146), it follows that or equivalently Consequently, it is sufficient to set:

-

Let fix Set Then:Next, from inequality (148), it follows that or equivalently Consequently, it is sufficient to set:

-

Let fix Using triangle inequality we have:Next, for all whenever we have and whenever we have respectively. Hence, it is sufficient to take to ensure the right hand side of inequality (150) is less than Finally:

- (a)

- the Rectified Linear Unit function (),

- (b)

- (c)

- ),

- (d)

- ),

- (e)

- (f)

- (g)

- the Heaviside function: (),

- (h)

- the Indicator function: (),

- (i)

- the Sawtooth norm: (),

- (j)

- the Tent map: (,

- (k)

- the Sawtooth wave function: ( ),

- (l)

- ,

- (m)

- ,

- (n)

- the Rect(boxcar) kernel: (,

- (o)

- ).

3.2.8. Pathologic Functions

-

Let and fix First, when it is sufficient to consider Second, assume We accomplish the proof in few steps.Step 1.(Upper Bound Representation). Using inequality (30) it follows that:Step 2. (Neighborhood Approximation). Set and By continuity of the functions and at point respectively, there are and such that for all whenever we have and whenever we have respectively. Equivalently:Step 3. (The delta Assessment). Let . Then, combining inequalities (152)-() we have:Finally, the formulae of via two times application of equation (55) for and respectively is given by:

-

Let and fix Then, using inequality (30) it follows that:Hence, by an application of equation (55) for it is sufficient to consider:

- Exact prefix match: If , then:

-

Adjacent prefix (first difference at position n): If the first index where differ is n (so the first digits agree), then:(Worst case: one side contributes a “first-1 spike” plus a tail .)

- in the same level-n cylinder (first n digits agree), or

- in adjacent level-n cylinders (first digits agree and they differ at digit n).

- Exact prefix match: If , then:

-

Adjacent prefix (first difference at position n): If the first index where differ is n (so the first digits agree), then:( Key point: intervals donotpile up; for each x only the first deletion level contributes, which is why the bounds are exactly and .)

- in the same level-n cylinder (first n digits agree), or

- in adjacent level-n cylinders (first digits agree and they differ at digit n).

- (a)

- f is type I Dirichlet function whenever

- (b)

- f is type II Dirichlet function whenever (for some ),

- (c)

- f is type III Dirichlet function whenever

- (d)

- f is type IV Dirichlet function whenever

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary and Contributions

4.2. Common Pitfalls

- Treating scratch work as a finished proof. Scratch work often contains tentative guesses—chains of equalities and inequalities relating and —some of which are unsuitable or too advanced for the final argument. For example, for one might invoke the Mean Value Theorem (MVT) to deduce . At the level considered here, however, the MVT is beyond the intended toolkit (which is limited to elementary algebraic identities, inequalities, and basic series facts). Our Appendix provides classroom aids designed to reinforce the structure of a complete and correct written proof.

- Treating as a unique function of . By definition, depends on the prescribed , but it need not be unique: any smaller also suffices. Moreover, continuity at a point typically yields , reflecting dependence on both the tolerance and the base point.

- Ignoring the function’s domain. The definition requires x and to lie in the domain . This is often overlooked. A practical remedy—adopted in this paper—is to extend f to when convenient, while explicitly formulating pointwise continuity with respect to the points in the original domain .

- Algebraic slips. Errors in algebraic manipulation (equalities or inequalities) can invalidate the inferred relationship between and . A final pass checking each logical implication in the chain of estimates is essential.

- Assuming a unique proof. The definition of continuity neither requires nor favors a single method. Our presentation provides one admissible construction among many. Alternative approaches can yield different, equally valid ’s. For instance, for one may start from the auxiliary identity:which leads to a distinct but legitimate – development.

4.3. Future Work and Open Research Problems

4.3.1. Point Continuity

- What is the necessary condition for f and such that ?

- What is the sufficient condition for f and such that ?

- Is there a necessary and sufficient condition for f and such that ?

4.3.2. Uniform Continuity

- What is the necessary condition for f such that ?

- What is the sufficient condition for f such that ?

- Is there a necessary and sufficient condition for f such that ?

Conclusion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

Appendix A. Classroom Aids: ϵ-δ Continuity Toolkit

Appendix A.1. Worksheet (Fully Worked Example: f(x)=x π :π=3.14159…)

Domain and goal.

Step 1 (Algebraic bound via TSBPB).

Step 2 (ϵ-δ planning).

Step 3 (Candidate δ).

Step 4 (Verification).

Appendix A.2. Analytic Rubric (Short Form; 10 Points)

| Criterion | Exceeds / Meets / Not Yet (pts) |

| Problem framing (2pts) | Correct domain identified; precise target for at . Exceeds (2pts): domain stated and goal restated; Meets (1pts): generally correct; NY (0pts): missing/misstated. |

| Bounding strategy (3pts) | Invokes TSBPB (case ) to obtain and justifies a local bound . Exceeds (3pts): fully justified; Meets (2pts): idea present with minor gaps; NY (0–1pts): incorrect or unjustified. |

| construction (3pts) | Gives explicit with . Exceeds (3pts): correct, boxed, and motivated; Meets (2pts): correct but thinly justified; NY (0–1pts): incorrect/implicit. |

| Quantifiers & closure (2pts) | Final implication verified and quantifiers audited. Exceeds (2pts): explicit audit; Meets (1pts): verification present; NY (0pts): omitted. |

Appendix A.3. Concept Questions (Peer Instruction/Clickers)

Q1 (Bounding the cofactor for x π ).

- (a)

- Assume , then , hence

- (b)

- Assume , then .

- (c)

- ; no auxiliary bound is needed.

- (d)

- Replace TSBPB by for all .

Q2 (Selecting δ).

- (a)

- (b)

- (c)

- (d)

Q3 (Quantifier sensitivity).

- (a)

- for all ).

- (b)

- ).

- (c)

- ).

- (d)

- such that the implication holds for all .

References

- Sinkiewicz, G. I. (2016). On History of Epsilontics. Antiquitates Mathematicae, 10(1), 183–204. [CrossRef]

- Grabiner, J. V. (1983). Who Gave You the Epsilon? Cauchy and the Origins of Rigorous Calculus. The American Mathematical Monthly, 90(3), 185–194. [CrossRef]

- Felscher, W. (2000). Bolzano, Cauchy, Epsilon, Delta. The American Mathematical Monthly, 107(9), 844–862. [CrossRef]

- Burton, D. M. (1997). The History of Mathematics: An Introduction (3rd ed.). New York, USA: McGraw–Hill. ISBN: 978-0-07-009465-9.

- Hardy, G. H. (1921). A Course of Pure Mathematics (3rd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN: 0521720559.

- Pugh, C. C. (2015). Real Mathematical Analysis (3rd ed.). Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. ISBN: 978-3-319-17770-0.

- Bartle, R. G., & Sherbert, D. R. (2011). Introduction to Real Analysis (4th ed.). Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN: 978-0-471-43331-6.

- Silverman, R. A. (1985). Calculus with Analytic Geometry. New Jersey, USA: Prentice-Hall, Inc. ISBN: 0-13-111634-7.

- Lin, S.-Y. T., & Lin, Y.-F. (1981). Set Theory with Applications (2nd ed.). Tampa, FL, USA: Mariner Publishing Company. ISBN: 964-01-0462-0.

- Hardy, G. H., Littlewood, J. E., & Pólya, G. (1952). Inequalities (2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN: 0521052068.

- Mossaheb, G. H. (1999). Analize Riazi: Teoriye A’dade Haghighi [Mathematical Analysis: Theory of Real Numbers] (Vol. 1). Tehran, Iran: Amirkabir Publication. ISBN: 964-00-0630-0. (In Persian).

- Abbott, S. (2015). Understanding Analysis (2nd ed.). Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics. New York, USA: Springer. ISBN: 978-1-4939-2711-1.

- Tao, T. (2016). Analysis I (3rd ed.). Texts and Readings in Mathematics. New Delhi/Singapore: Hindustan Book Agency / Springer, India. ISBN: 978-93-80250-64-9.

- Botelho, F. S. (2018). Real Analysis and Applications. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. ISBN: 978-3-319-78630-8.

- Loeb, P. A. (2016). Real Analysis. Switzerland: Birkhäuser / Springer International Publishing. ISBN: 978-3-319-30742-8.

- Knopp, K. (1996). Algebraic Functions. In Theory of Functions, Parts I and II (pp. 119–134). New York: Dover Publications.

- Bronstein, M. , Corless, R. M., Davenport, J. H., & Jeffrey, D. J. (2008). Algebraic properties of the Lambert W function from a result of Rosenlicht and of Liouville. Integral Transforms and Special Functions 19(10), 709–712. [CrossRef]

- Frigg, R. , & Werndl, C. (2011). Entropy – A Guide for the Perplexed. In C. Beisbart & S. Hartmann (Eds.), Probabilities in Physics (pp. 115–142). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Hooshmand, M. H. (2006). Ultrapower and ultraexponential functions. Integral Transforms and Special Functions, 17(8), 549–558. [CrossRef]

- Harris, F. E. (2014). Probability and Statistics. In F. E. Harris (Ed.), Mathematics for Physical Science and Engineering (pp. 663–709). Academic Press. ISBN: 9780128010006. [CrossRef]

- Verhulst, P.-F. (1838). Notice sur la loi que la population poursuit dans son accroissement. Correspondance Mathématique et Physique, 10, 113–121. (French; PDF, retrieved October 26, 2025).

- Oldham, K. B., Myland, J., & Spanier, J. (2009). An Atlas of Functions: withEquator, the Atlas Function Calculator (2nd ed.). New York, NY, USA: Springer. Hardcover ISBN: 978-0-387-48806-6.

- Knuth, D. E. (1997). The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 1: Fundamental Algorithms (3rd ed.). Reading, MA: Addison–Wesley Longman. ISBN: 0-201-89683-4.

- Graham, R. L., Knuth, D. E., & Patashnik, O. (1989). Concrete Mathematics: A Foundation for Computer Science. Reading, MA: Addison–Wesley Publishing Company. xiii+625 pp. ISBN: 0-201-14236-8.

- Ponce-Campuzano, J. C., & Maldonado-Aguilar, M. Á. (2015). Vito Volterra’s construction of a nonconstant function with a bounded, non-Riemann integrable derivative. BSHM Bulletin: Journal of the British Society for the History of Mathematics, 30(2), 143–152. [CrossRef]

- Soltanifar, M. Some Results on the Variation of Composite Function of Functions of Bounded Variation. American Journal of Undergraduate Research, 6(4). [CrossRef]

- Dovgoshey, O. , Martio, O., Ryazanov, V., & Vuorinen, M. (2006). The Cantor function. Expositiones Mathematicae 24(1), 1–37. [CrossRef]

- Beanland, K. (2009). Modifications of Thomae’s function and differentiability. The American Mathematical Monthly, 116(6), 531–535. [CrossRef]

- Weisstein, E. W. (2025). Weierstrass Function. From MathWorld—A Wolfram Resource. https://mathworld.wolfram.com/WeierstrassFunction.html. Accessed: 2025-10-26.

- Hata, M. , & Yamaguti, M. (1984). The Takagi function and its generalization. Japan Journal of Applied Mathematics 1, 183–199. [CrossRef]

- Weierstrass, K. (1895). Über continuirliche Functionen eines reellen Arguments, die für keinen Werth des letzteren einen bestimmten Differentialquotienten besitzen. In Mathematische Werke von Karl Weierstrass (Vol. 2, pp. 71–74). Berlin: Mayer & Müller. (German; English trans.: On continuous functions of a real argument which possess a definite derivative for no value of the argument.

- Lejeune Dirichlet, P. G. (1829). Sur la convergence des séries trigonométriques qui servent à représenter une fonction arbitraire entre des limites données. Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik, 4, 157–169. (French).

- Soltanifar, M. (2023). A Classification of Elements of Function Space F(R,R). Mathematics, 11(17), Article 3715. [CrossRef]

- Hernández, C. A. (2015). Epsilon–delta proofs and uniform continuity. Lecturas Matemáticas, 36(1), 23–32.

- Hernández Melo, C. A., & Hernández, F. D. de M. (2019). Uniform Continuity: Another Way to Approach This Concept in the Classroom. The College Mathematics Journal, 50(1), 54–57. [CrossRef]

- Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M. C., & Norman, M. K. (2010). How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching. Jossey-Bass.

- Chi, M. T. H. , & Wylie, R. (2014). The ICAP framework: Linking cognitive engagement to active learning outcomes. Educational Psychologist, 49, 219–243. [CrossRef]

- Mazur, E. (1997). Peer Instruction: A User’s Manual. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Freeman, S. , Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111(23), 8410–8415. [CrossRef]

- Deslauriers, L. , McCarty, L. S., Miller, K., Callaghan, K., & Kestin, G. (2019). Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to active learning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116(39), 19251–19257. [CrossRef]

| # | Cluster | Sample |

|---|---|---|

| –Function () | ||

| 1 | Algebraics | |

| 1-1 | —Polynomials | |

| 1-2 | —Powers | |

| 1-3 | —General Rationals | |

| 2 | Exponential and Logarithmic | |

| 2-1 | —Logarithm | |

| 2-2 | —Exponential | |

| 2-3 | —Inverse Lambert | |

| 2-4 | —Neg. Entropy Potential | |

| 2-5 | —Tetration | |

| 2-6 | —Normal density | |

| 2-7 | —Logistic | |

| 3 | Trigonometric | |

| 3-1 | —Trig 1 | |

| 3-2 | —Trig 2 | |

| 3-3 | —Trig 3 | |

| 3-4 | —Trig 4 | |

| 3-5 | —Trig 5 | |

| 3-6 | —Trig 6 | |

| 4 | Inverse-Trigonometric | |

| 4-1 | —Inv-Trig 1 | |

| 4-2 | —Inv-Trig 2 | |

| 4-3 | —Inv-Trig 3 | |

| 4-4 | —Inv-Trig 4 | |

| 4-5 | —Inv-Trig 5 | |

| 4-6 | —Inv-Trig 6 | |

| 5 | Hyperbolic | |

| 5-1 | —Hyperb 1 | |

| 5-2 | —Hyperb 2 | |

| 5-3 | —Hyperb 3 | |

| 5-4 | —Hyperb 4 | |

| 5-5 | —Hyperb 5 | |

| 5-6 | —Hyperb 6 | |

| 6 | Inverse-Hyperbolic | |

| 6-1 | —Inv-Hyperb 1 | |

| 6-2 | —Inv-Hyperb 2 | |

| 6-3 | —Inv-Hyperb 3 | |

| 6-4 | —Inv-Hyperb 4 | |

| 6-5 | —Inv-Hyperb 5 | |

| 6-6 | —Inv-Hyperb 6 | |

| 7 | Elementary Piecewise | |

| 7-1 | —Absolute value | |

| 7-2 | —Lower clipping | |

| 7-3 | —Upper clipping | |

| 7-4 | —Clamp clip | |

| 7-5 | —Signum | |

| 7-6 | —Floor | |

| 7-7 | —Ceiling | |

| 7-8 | —Fractional | |

| 8 | Pathological | |

| 8-1 | —Standard Volterra’s | |

| 8-2 | —Damped topologist’s sine | |

| 8-3 | —Topologist’s sine | |

| 8-4 | —Cantor | |

| 8-5 | —Thomae | |

| 8-6 | —Riemann | |

| 8-7 | —Takagi | |

| 8-8 | —Weierstrass | |

| 8-9 | —Type I Dirichlet | |

| DNE | ||

| 8-10 | —Type II Dirichlet | |

| 8-11 | —Type III Dirichlet | |

| 8-12 | —Type IV Dirichlet | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).