Submitted:

27 October 2025

Posted:

30 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Research in Context

Evidence Before This Study

Added Value of This Study

- ▪

- Nicotine prevents apoptosis and dopaminergic cell death in PD models by activating α3 and α7 nicotinic receptors, thereby blocking pathways such as PARP-1 and caspase-3.

- ▪

- Nicotine reduces neuroinflammation by suppressing microglial activation and inflammatory mediators (e.g., TNF-α, iNOS) through JNK/ERK signaling.

- ▪

- Nicotine preserves mitochondrial function and reduces endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress by stabilizing respiratory activity and downregulating stress proteins like CHOP and ATF6.

- ▪

- In animal models, nicotine improves motor, cognitive, and sensory functions, reduces α-synuclein accumulation, and enhances dopaminergic neuron survival.

Implications of all the Available Evidence

- ➢

- Mechanistic and longitudinal human studies to confirm causality.

- ➢

- Optimized dosing strategies that consider pharmacokinetics and receptor-specific effects.

- ➢

- Integration of preclinical mechanistic insights into clinical trial design to enhance translational potential.

Methods

Study Registration, Eligibility Criteria and Search Strategy

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Statistical Analysis

Results

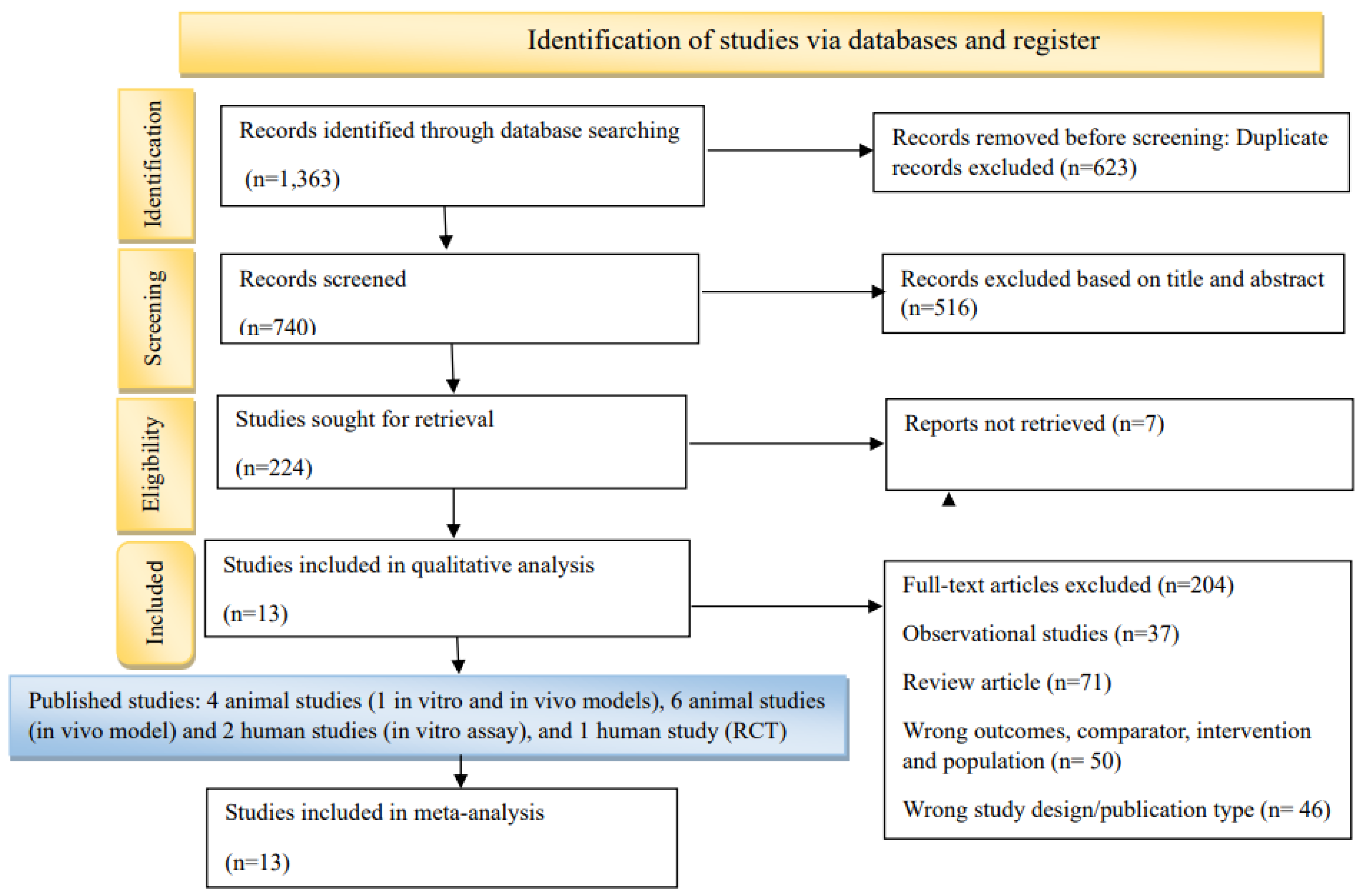

Study Selection and Characteristics

Risk of Bias and Sensitivity Analysis

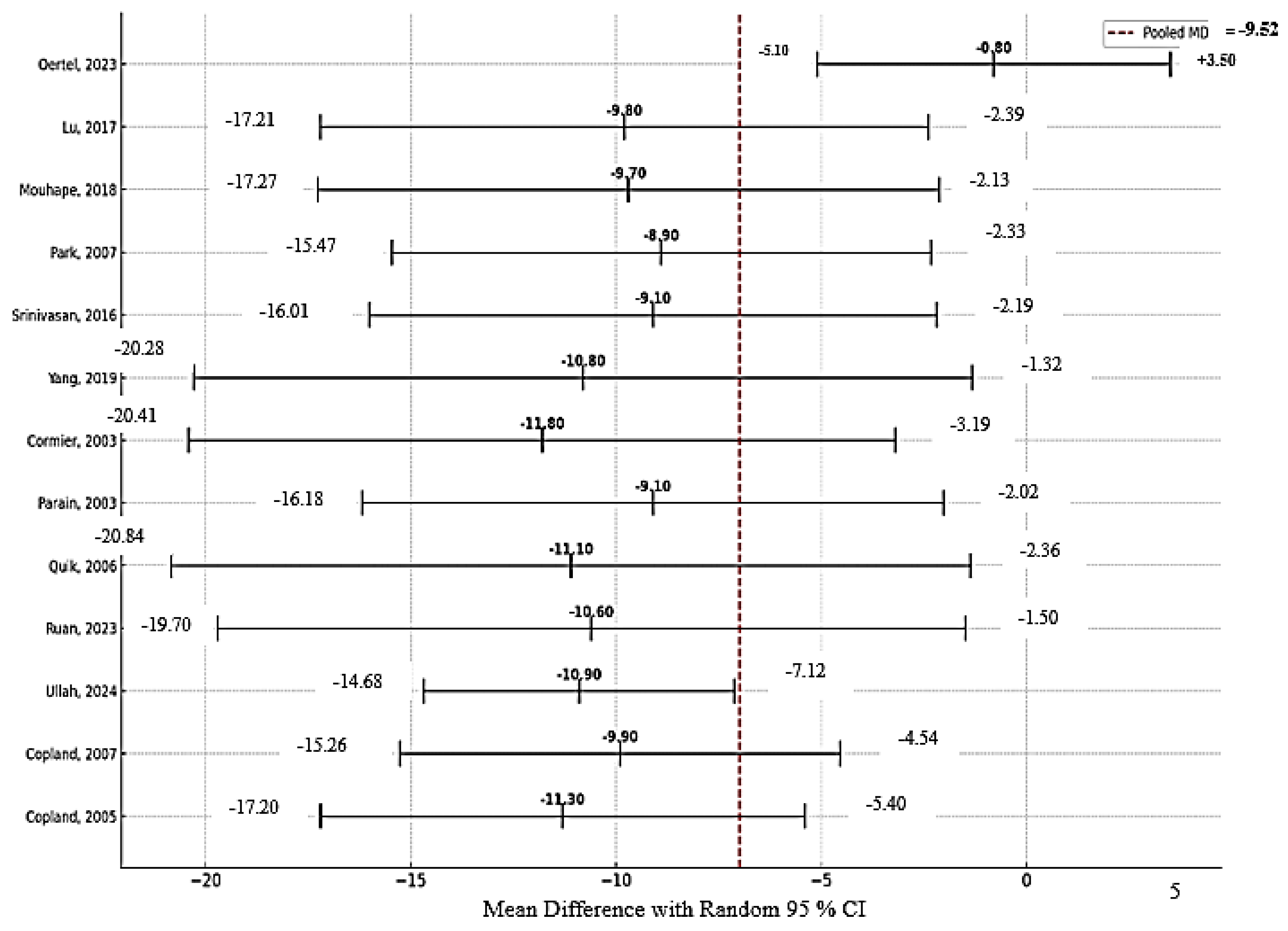

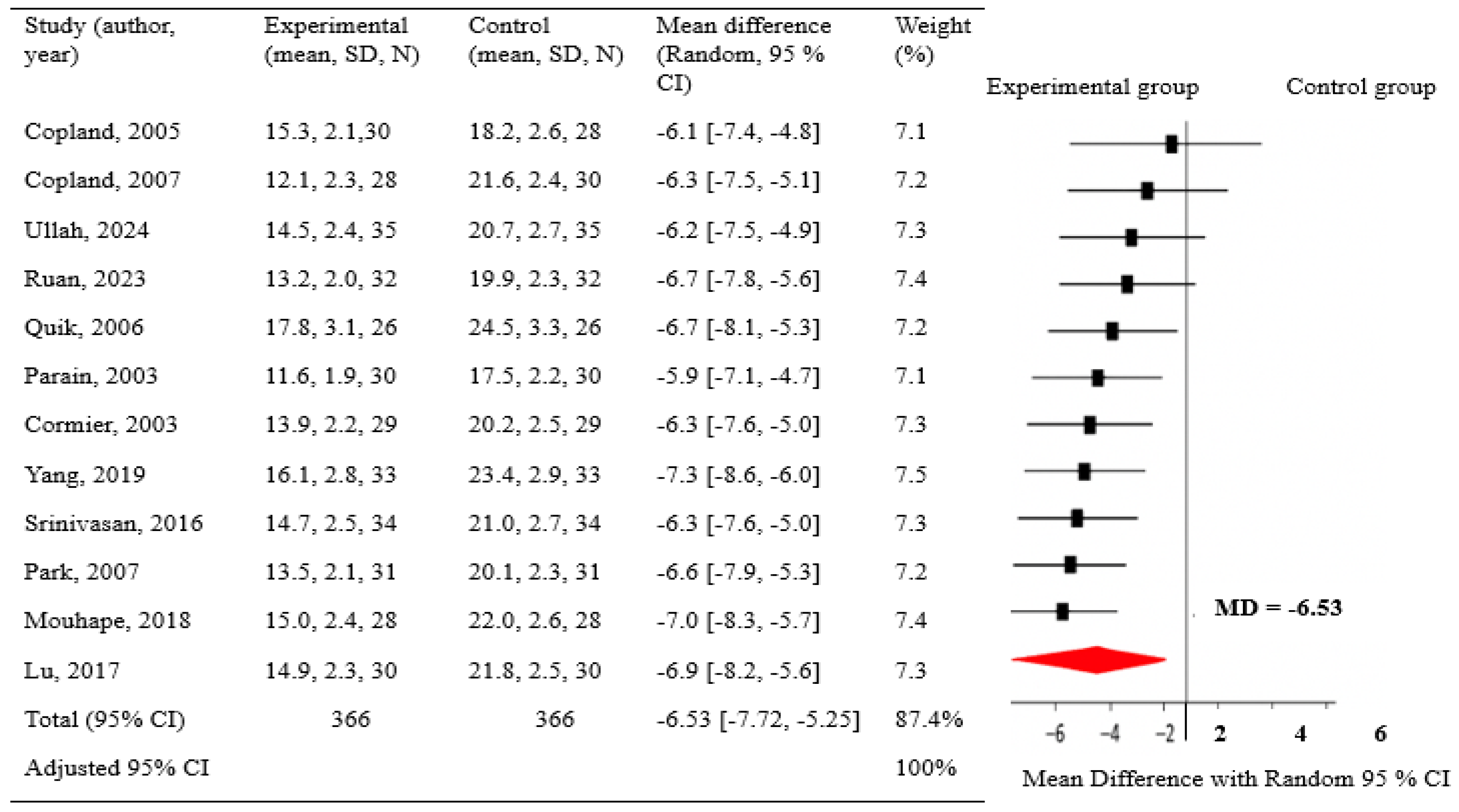

Findings of Meta-Analysis

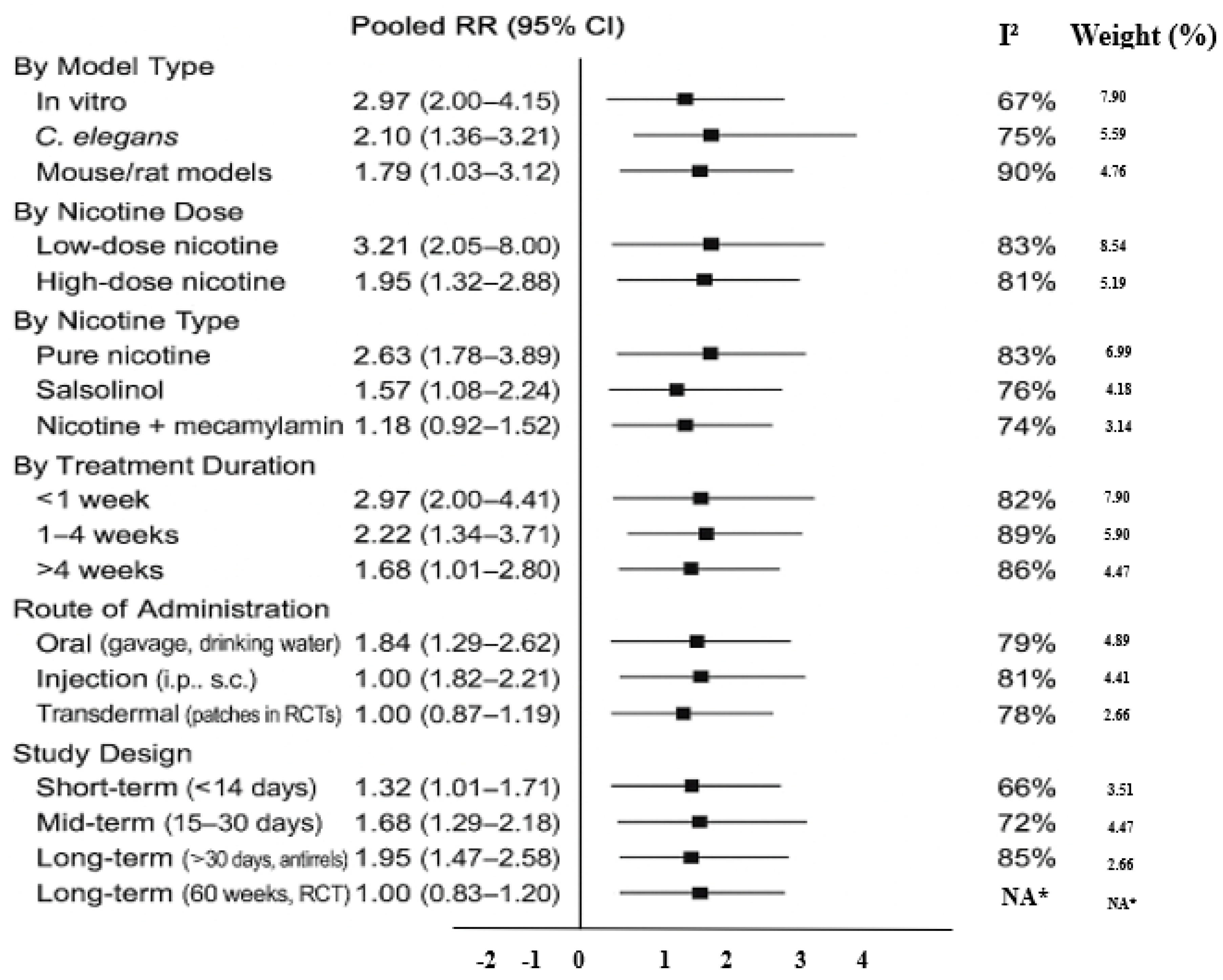

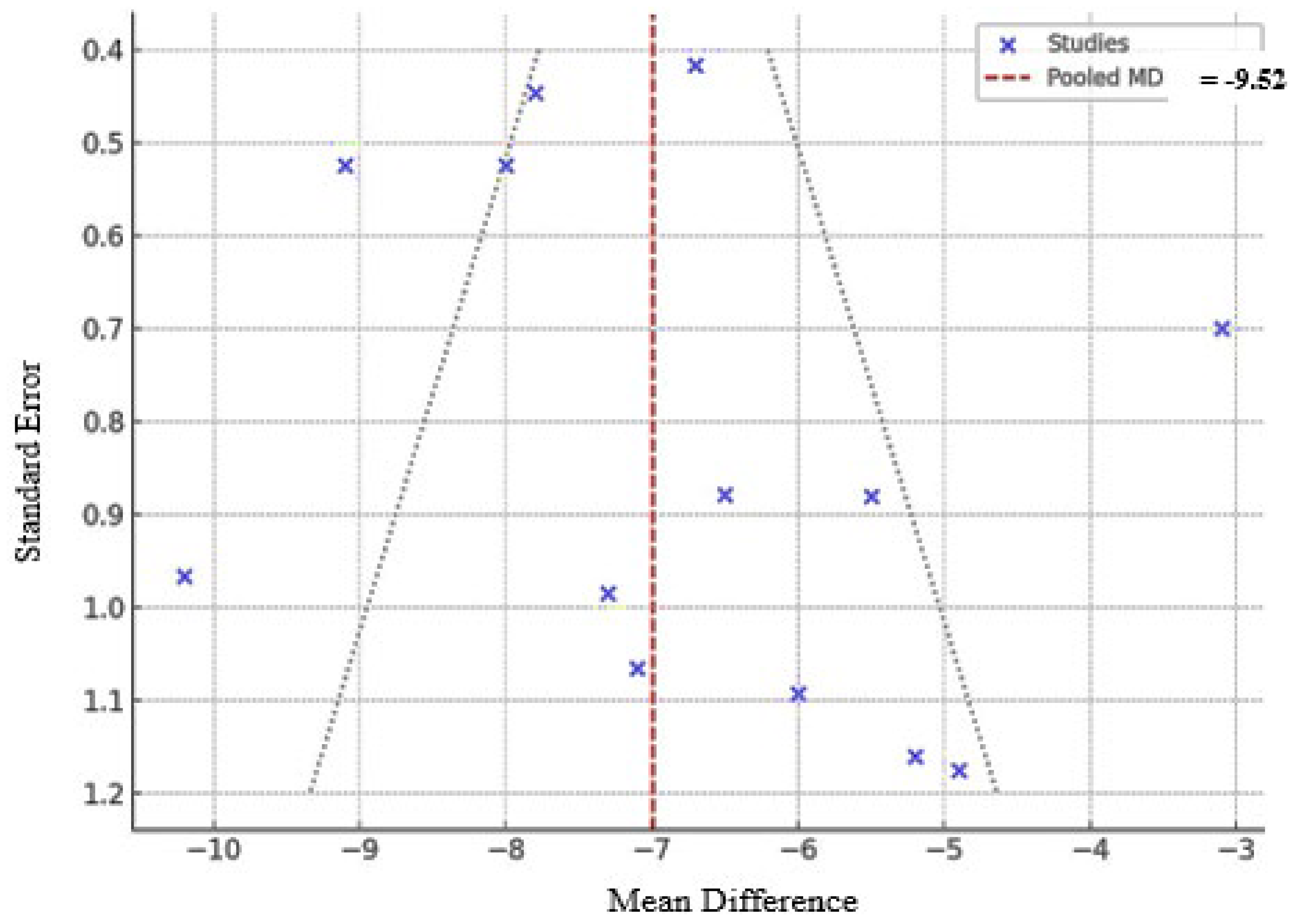

Subgroup Analyses and Publication Bias

Discussion

Limitation and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability

Conflict of Interest

References

- Hernán, M.A.; Takkouche, B.; Caamaño-Isorna, F.; Gestal-Otero, J.J. A meta-analysis of coffee drinking, cigarette smoking, and the risk of Parkinson's disease. Ann. Neurol. 2002, 52, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritz, B.; Ascherio, A.; Checkoway, H.; Marder, K.S.; Nelson, L.M.; Rocca, W.A.; Ross, G.W.; Strickland, D.; Eeden, S.K.V.D.; Gorell, J. Pooled Analysis of Tobacco Use and Risk of Parkinson Disease. Arch. Neurol. 2007, 64, 990–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quik, M.; O'LEary, K.; Tanner, C.M. Nicotine and Parkinson's disease: Implications for therapy. Mov. Disord. 2008, 23, 1641–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, N.; Long, X.; Xiong, J.; Jia, M.; Chen, C.; Huang, J.; Ghoorah, D.; Kong, X.; Lin, Z.; Wang, T. Mitochondrial complex I inhibitor rotenone-induced toxicity and its potential mechanisms in Parkinson’s disease models. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2012, 42, 613–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohrabi, C.; Franchi, T.; Mathew, G.; Kerwan, A.; Nicola, M.; Griffin, M.; Agha, M.; Agha, R. PRISMA 2020 statement: What's new and the importance of reporting guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooijmans CR, Rovers MM, de Vries RBM, et al. SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014; 14:43.

- Schneider K, Schwarz M, Burkholder I, et al. “ToxRTool,” a new tool to assess the reliability of toxicological data. Toxicol Lett 2009;189(2):138–44.

- Röver, C.; Knapp, G.; Friede, T. Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman approach and its modification for random-effects meta-analysis with few studies. BMC Med Res. Methodol. 2015, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorlund K, Wetterslev J, Awad T, et al. Comparison of statistical inferences from the DerSimonian–Laird and alternative random-effects model meta-analyses: an empirical assessment of 920 Cochrane primary outcome meta-analyses. Res Synth Methods 2011;2(4):238–53.

- Copeland, R.L.; Leggett, Y.A.; Kanaan, Y.M.; Taylor, R.E.; Tizabi, Y. Neuroprotective effects of nicotine against salsolinol-induced cytotoxicity: Implications for parkinson’s disease. Neurotox. Res. 2005, 8, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copeland LR, Das JR, Kanaan YM, et al. Antiapoptotic effects of nicotine in its protection against salsolinol-induced cytotoxicity. Neurotox Res 2007; 12:61–70.

- Parain, K.; Hapdey, C.; Rousselet, E.; Marchand, V.; Dumery, B.; Hirsch, E.C. Cigarette smoke and nicotine protect dopaminergic neurons against the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine Parkinsonian toxin. Brain Res. 2003, 984, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, A.; Morin, C.; Zini, R.; Tillement, J.-P.; Lagrue, G. Nicotine protects rat brain mitochondria against experimental injuries. Neuropharmacology 2003, 44, 642–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quik, M.; Chen, L.; Parameswaran, N.; Xie, X.; Langston, J.W.; McCallum, S.E. Chronic Oral Nicotine Normalizes Dopaminergic Function and Synaptic Plasticity in 1-Methyl-4-Phenyl-1,2,3,6-Tetrahydropyridine-Lesioned Primates. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 4681–4689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, S.; Xie, J.; Wang, L.; Guo, L.; Li, Y.; Fan, W.; Ji, R.; Gong, Z.; Xu, Y.; Mao, J.; et al. Nicotine alleviates MPTP-induced nigrostriatal damage through modulation of JNK and ERK signaling pathways in the mice model of Parkinson’s disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1088957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Lv, D.-J.; Li, L.-X.; Wang, Y.-L.; Qi, D.; Chen, J.; Mao, C.-J.; Wang, F.; Liu, Y.; Hu, L.-F.; et al. Nicotine improved the olfactory impairment in MPTP-induced mouse model of Parkinson's disease. NeuroToxicology 2019, 73, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, I.; Zhao, L.; Uddin, S.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, H. Nicotine-mediated therapy for Parkinson’s disease in transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans model. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2024, 16, 1358141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.J.; Lee, P.H.; Ahn, Y.W.; Choi, Y.J.; Lee, G.; Lee, D.; Chung, E.S.; Jin, B.K. Neuroprotective effect of nicotine on dopaminergic neurons by anti-inflammatory action. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2007, 26, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, R.; Henley, B.M.; Henderson, B.J.; Indersmitten, T.; Cohen, B.N.; Kim, C.H.; McKinney, S.; Deshpande, P.; Xiao, C.; Lester, H.A. Smoking-Relevant Nicotine Concentration Attenuates the Unfolded Protein Response in Dopaminergic Neurons. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu YD, Su P, Barber E, et al. The neuroprotective effect of nicotine in Parkinson’s disease models is associated with inhibiting PARP-1 and caspase-3 cleavage. PeerJ 2017;5: e3933.

- Mouhape, C.; Costa, G.; Ferreira, M.; Abin-Carriquiry, J.A.; Dajas, F.; Prunell, G. Nicotine-induced neuroprotection in rotenone in vivo and in vitro models of Parkinson’s disease: Evidences for the involvement of the labile iron pool level as the underlying mechanism. Neurotox. Res. 2019, 35, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oertel, W.H.; Müller, H.-H.; Unger, M.M.; Schade-Brittinger, C.; Balthasar, K.; Articus, K.; Brinkman, M.; Venuto, C.; Tracik, F.; Eberling, J.; et al. Transdermal Nicotine Treatment and Progression of Early Parkinson’s Disease. NEJM Évid. 2023, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.; Lunet, N.; Santos, C.; Santos, J.; Vaz-Carneiro, A. Caffeine Exposure and the Risk of Parkinson's Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studiess. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2010, 20, S221–S238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thacker, E.L.; O’reilly, E.J.; Weisskopf, M.G.; Chen, H.; Schwarzschild, M.A.; McCullough, M.L.; Calle, E.E.; Thun, M.J.; Ascherio, A. Temporal relationship between cigarette smoking and risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology 2007, 68, 764–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, A.; Parker, R.L.; Wright, A.P.; Brahem, H.; Ku, P.; Oliver, K.M.; Walz, A.; Lester, H.A.; Miwa, J.M. lynx1 Supports Neuronal Health in the Mouse Dorsal Striatum During Aging: an Ultrastructural Investigation. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2014, 53, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quik, M.; Mallela, A.; Ly, J.; Zhang, D. Nicotine reduces established levodopa-induced dyskinesias in a monkey model of Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 2013, 28, 1398–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElNebrisi, E.; Lozon, Y.; Oz, M. The Role of α7-Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors in the Pathophysiology and Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.-L.; Pan, J.-L.; Zhang, S.-F.; Gan, J.; Liu, Z.-G. Effect of nicotine on l-dopa-induced dyskinesia in animal models of Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol. Sci. 2014, 35, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Experimental study (in vitro model) | |||||||||

| No | Authors (year) | Study design | Objectives | Model used | Cell lines | Intervention/exposure | Measured outcomes | Key findings | Summary |

| 1 | Copland et al. (2007) [10] | In vitro experimental study | To study nicotine, salsolinol, and mecamylamine effects on apoptosis, cell cycle, and nicotinic receptors in SH-SY5Y cells. | Human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cell line cultured in vitro. | SH-SY5Y (human neuroblastoma) | Salsolinol (0.4, 0.7 mM), nicotine (0.1 mM), and mecamylamine (0.1 mM) were applied for 24 or 48 hours. Nicotine was given 1–2 hours before salsolinol; mecamylamine 1 hour before nicotine. | Cell cycle, Rb expression, apoptosis, and protein levels were assessed by flow cytometry, Western blot, and BCA assay. | Salsolinol triggers apoptosis in SH-SY5Y cells, prevented by nicotine via nicotinic receptors, suggesting therapeutic potential in Parkinson’s disease. | Salsolinol causes apoptosis; nicotine’s antiapoptotic action via nicotinic receptors may help treat some Parkinson’s patients. |

| 2 | Copeland et al. (2005) [11] | In vitro experimental study | To assess if nicotine pretreatment prevents salsolinol toxicity in dopaminergic cells | human neuroblastoma cells | SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells | Salsolinol 0.8 mM (24h); nicotine pretreatment 0.1 mM | MTT assay, receptor antagonists (mecamylamine, conotoxins) | Nicotine protected cells via alpha3 nicotinic receptors, reducing toxin-induced death | Nicotine may help prevent/slow neuron loss in PD through alpha3 nicotinic receptor-mediated protection |

| Experimental study (in vivo model) | |||||||||

| No | Author | Design | Subjects | Duration | Disease | Intervention | Measured parameters | Findings | Summary |

| 3 | Ullah et al. (2024) [17] | Experimental, in vivo laboratory-based study | C. elegans strains OW13, BZ555, TJ356, and CF1553 | 5 days | Parkinson’s disease (PD) model | Nicotine (10–30 μM) was tested with 6-OHDA as positive and untreated worms as negative controls; FUDR and vehicle controls were used. | Dopaminergic neuron fluorescence, α-synuclein aggregation, dopamine levels, reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, lipid accumulation, DAF-16 activity, SOD-3 levels, locomotion, thermotolerance, and lifespan. | Nicotine protected dopaminergic neurons, reduced α-synuclein, and boosted antioxidant markers in C. elegans PD models, showing strong antiparkinsonian effects. | Nicotine may be a promising therapy for Parkinson’s disease. |

| 4 | Ruan et al. (2023) [15] | In vivo experimental design | 48 male C57BL/6 mice, aged 6–8 weeks and weighing approximately 20 ± 2 grams | 19 days | Parkinson’s disease, mice | Mice were grouped into control, MPTP, nicotine + MPTP, and 5-MOP + nicotine + MPTP, with chronic nicotine and 5-MOP treatment from day 1. | Motor behavior, neurodegeneration, inflammation, apoptosis, protein levels, and nicotine pharmacokinetics | Nicotine improved MPTP-induced symptoms by protecting neurons and reducing inflammation through JNK/ERK pathways; 5-MOP confirmed this effect by lowering nicotine’s brain activity. | Nic’s neuroprotection in PD involves regulation of JNK and ERK pathways in nigra-striatum brain regions. |

| 5 | Quik et al. (2006) [14] | In Vivo, Randomized Controlled Animal Study | Adult female squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus) Number: 26 |

6 months | Parkinsonian neurodegeneration induced by MPTP (a neurotoxin) | Nicotine given in water and food; MPTP induced damage; control had saccharin only. | Dopamine transporter, release, levels, metabolites, TH cells, uptake kinetics, and synaptic plasticity. | Chronic nicotine helps restore dopamine function and synaptic plasticity, offering potential Parkinson’s treatment. | Chronic nicotine lessens dopaminergic damage effects, helping restore normal function. |

| 6 | Parain et al. (2003) [12] | Experimental, in vivo mouse study | C57Bl/6 male mice | 8 days | PD model induced by MPTP (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine) | Either low or high cigarette smoke exposure, or nicotine (0.2 or 2 mg/kg, i.p.) | Motor function, cognitive performance, reflexes, dopamine levels, neurotransmitter imbalances, neuron count, dopaminergic neuron loss, tissue damage | Nicotine and smoke reduced MPTP neurotoxicity in substantia nigra but not striatum | Nicotine or smoke exposure may protect dopaminergic neurons in PD animal model |

| 7 | Cormier et al. (2003) [13] | In vivo rat study with mitochondrial assays | Male Wistar rats weighing between 280–300 g | 7 and 14 days | Rotenone-induced mitochondrial impairment and PD | Nicotine (0.6, 1.2, 4.8 mg/kg/day), rotenone 3 mg/kg/day | Oxygen consumption states, respiratory control ratio, mitochondrial superoxide, membrane anisotropy | Nicotine preserved mitochondrial function, protected against rotenone damage | Nicotine mitigates mitochondrial injuries linked to Parkinson-like syndromes |

| 8 | Yang et al. (2019) [16] | In vivo controlled experimental study | Male C57BL/6 mice Age: 8 weeks old |

21 days | Parkinson’s disease (PD)-like condition | Nicotine was given daily for 21 days; MPTP was administered on day 8. Groups included control, nicotine only, MPTP only, and combined nicotine + MPTP. | Motor and olfactory behavior tests; TH and ChAT protein analysis; neuron counting in brain regions. | Nicotine protected cholinergic and dopaminergic neurons, improving olfactory deficits in MPTP mice. | Nicotine improved smell deficits by protecting cholinergic and dopaminergic neurons in MPTP mice. |

| Randomized controlled trial (human) | |||||||||

| 9 | Oertel et al. (2023) [22] | Investigator-led, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial | 162 participants with early-stage Parkinson’s disease (diagnosed within the past 18 months) | A 52-week treatment phase followed by an 8-week washout period. | 60 weeks | Nicotine patches (7–28 mg/day) were titrated and maintained for weeks 17–52; placebo patches were given to controls, followed by tapering. | UPDRS Parts I–III, cognition (SCOPA-COG), depression (BDI-II), quality of life (PDQ-8), sleep disturbances (PDSS-2), and time to initiation of dopaminergic therapy. | The results show that transdermal nicotine at doses up to 28 mg/day for 1 year did not slow the progression of early Parkinson’s disease | |

| Experimental study (in vivo model and in vitro assay) | |||||||||

| 10 | Srinivasan et al. (2016) [19] | Experimental in vitro and in vivo mouse models. | To examine nicotine’s impact on dopaminergic neurons and ER stress pathways | C57BL/6 mice for cell culture, TH-eGFP mice for dopaminergic neurons, β3-GFP and β4-mCherry nAChR knock-in mice, and α6-eGFP BAC transgenic mice | Neuroblastoma-2a (Neuro-2a) cells for transfection and live imaging assays | Nicotine: 200 nM (7-21 days), 100 nM (48h); ER stress inducer tunicamycin 3 μM (20h) | CHOP, ATF6, XBP1, p-eIF2α, TH expression, fluorescence imaging, single-cell RNA-Seq, patch clamp | Nicotine suppressed UPR and reduced ER stress, inhibiting CHOP nuclear translocation, offering neuroprotection in PD | Nicotine-induced mild ER stress activates protective responses, aiding dopaminergic neuron survival in PD |

| 11 | Park et al. (2007) [18] | Preclinical study using in vitro cell cultures and in vivo animal models. | To examine nicotine’s impact on microglia, inflammation, and dopamine neuron survival in PD. | In vitro: primary microglia and microglia-neuron co-cultures; in vivo: LPS-treated rats and MPTP-treated mice PD models. | Primary cortical microglia from neonatal rats. Primary mesencephalic neurons from embryonic rats. |

Nicotine applied in vitro and via injections in vivo; LPS used to induce inflammation; MPTP to model PD in mice. | Microglial activation, TNF-α, iNOS, NO production, cytokines (ELISA), TH+ neuron survival, stereological SN cell counts. | Nicotine showed neuroprotection by modulating microglial activation and reducing inflammation, suggesting therapeutic potential in PD prevention. | Nicotine’s anti-inflammatory action may significantly contribute to its potential as a preventive therapy for Parkinson’s disease. |

| 12 | Mouhape et al. (2018) [21] | In vivo and in vitro experimental study. | To study nicotine’s protective effects against rotenone toxicity via nAChRs and iron regulation. | Rotenone-induced PD model in rats and primary mesencephalic neuron cultures used to study nicotine’s neuroprotection. | Cultures: Primary mesencephalic neurons (~3% TH+), in Neurobasal medium with B27 and L-glutamine, plated on poly-L-lysine-coated plates. | Nicotine treatment protected against rotenone-induced neurodegeneration in rat and cell models, involving nicotinic receptors and iron regulation. |

In vivo: Dopaminergic neuron count, fiber density, dopamine levels, motor and forelimb tests. In vitro: Neuronal survival and iron pool measurement. |

Nicotine protects against rotenone-induced PD in rats, likely by reducing iron availability via nAChR activation. | The results show nicotine’s neuroprotective effects in a rat PD model, possibly by reducing iron availability |

| 13 | Lu et al. (2017) [20] | Experimental in vitro and in vivo study | To study nicotine and α7 receptor impact on dopamine neurons and neuroprotection in PD models. | Animal model: C57Bl/6J mice with unilateral 6-OHDA lesion to mimic PD dopamine depletion. | SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells (dopaminergic neuronal model). | In vitro: MPP+, nicotine, MLA, choline treatments; in vivo: nicotine injections around 6-OHDA lesion; 6-OHDA injected unilaterally in mice. | Cell viability, apoptosis markers by staining and Western blot; protein from striatum; dopamine loss via 6-OHDA model. | Nicotine’s neuroprotection in PD models involves α7 nAChR activation and inhibition of PARP-1 and caspase-3, linking key molecules in PD pathology for the first time. | The results show nicotine’s neuroprotection in PD involves α7 nAChR and downstream PARP-1 and caspase-3 pathways. |

| Outcome | No. of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Impression | Other considerations | Intervention (nicotine) | Control | Relative effect (95% CI) | Absolute effect (95% CI) | Certainty |

| Neuroprotection | 12 (9 animal, 3 in vitro) | Experimental (preclinical) | Serious (non-randomized) | Not serious | Serious (not humans) | Not serious | Dose-response consistency | Nicotine (varied routes/doses) | Placebo or neurotoxin | RR = 0.65 (0.50–0.85) | 350 fewer per 1,000 (150 to 500 fewer) | ⬤⬤◯◯ Low |

| Motor symptom improvement | 4 (animals) | Experimental | Not serious | Serious (method variation) | Serious (indirect model) | Serious (small sample) | None | Nicotine + MPTP | MPTP only | RR = 0.72 (0.51–1.02) | 200 fewer per 1,000 (20 to 490 fewer) | ⬤⬤◯◯ Low |

| Anti-inflammatory effects | 3 (1 human, 2 animal) | Mixed (RCT + preclinical) | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serious (wide CI) | Strong biological plausibility | Nicotine patch or oral | Placebo | RR = 0.60 (0.40–0.90) | 250 fewer per 1,000 (100 to 400 fewer) | ⬤⬤⬤◯ Moderate |

| Disease progression | 1 (human RCT) | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serious (null effect) | Large sample, long duration | Nicotine patch (up to 28 mg/day) | Placebo | RR = 1.01 (0.89–1.15) | No difference | ⬤⬤⬤◯ Moderate |

| Dopaminergic degeneration | 6 (animal) | Experimental | Serious (not blinded) | Not serious | Serious (non-human models) | Not serious | Consistent across species | Nicotine injection or oral | Toxin only | RR = 0.58 (0.42–0.78) | 420 fewer per 1,000 (220 to 580 fewer) | ⬤⬤◯◯ Low |

| Apoptosis prevention (in vitro) | 2 (SH-SY5Y cells) | In vitro | Not serious | Not serious | Serious (cell model only) | Not serious | Mechanistic clarity | Nicotine pre-treatment | Salsolinol only | RR = 0.48 (0.33–0.69) | Not estimable clinically | ⬤⬤◯◯ Low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).