Submitted:

28 October 2025

Posted:

29 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

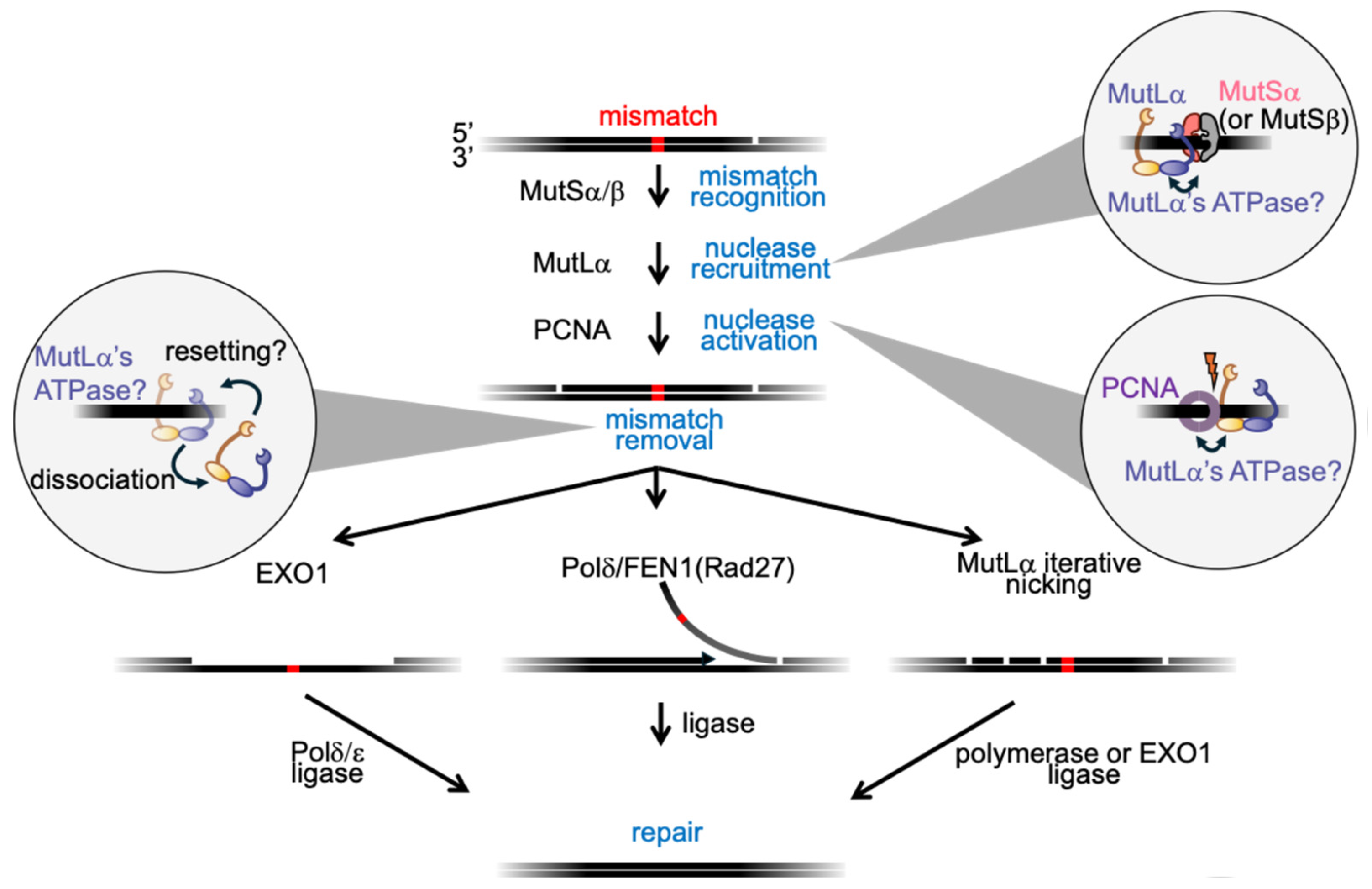

1. Enigmatic Features of MutL Homolog ATPase Activity

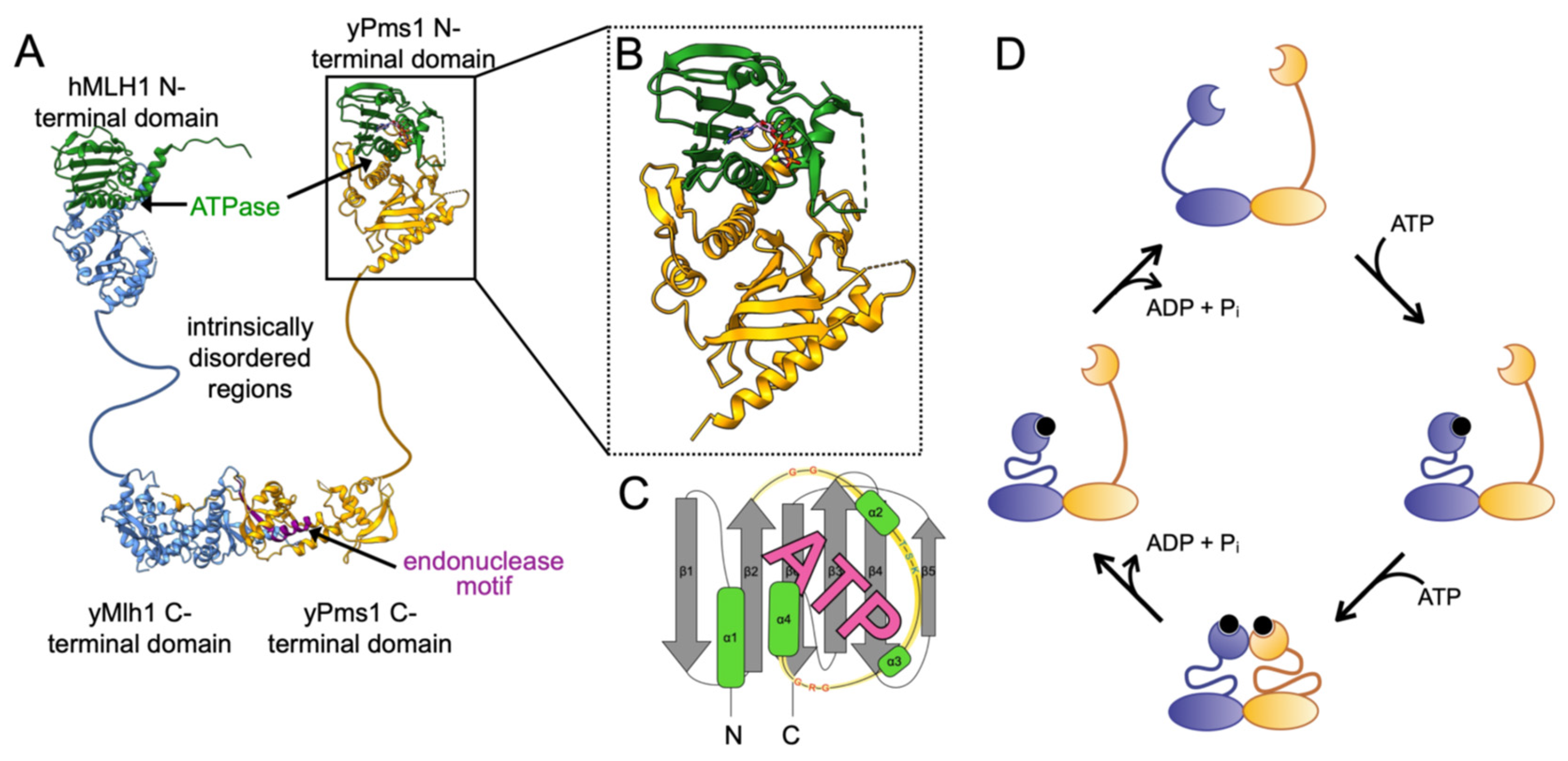

1.1. MutL Homolog Architecture and ATPase-Driven Conformational Changes

1.2. Higher-Order MutL Assemblies and Partner Interactions

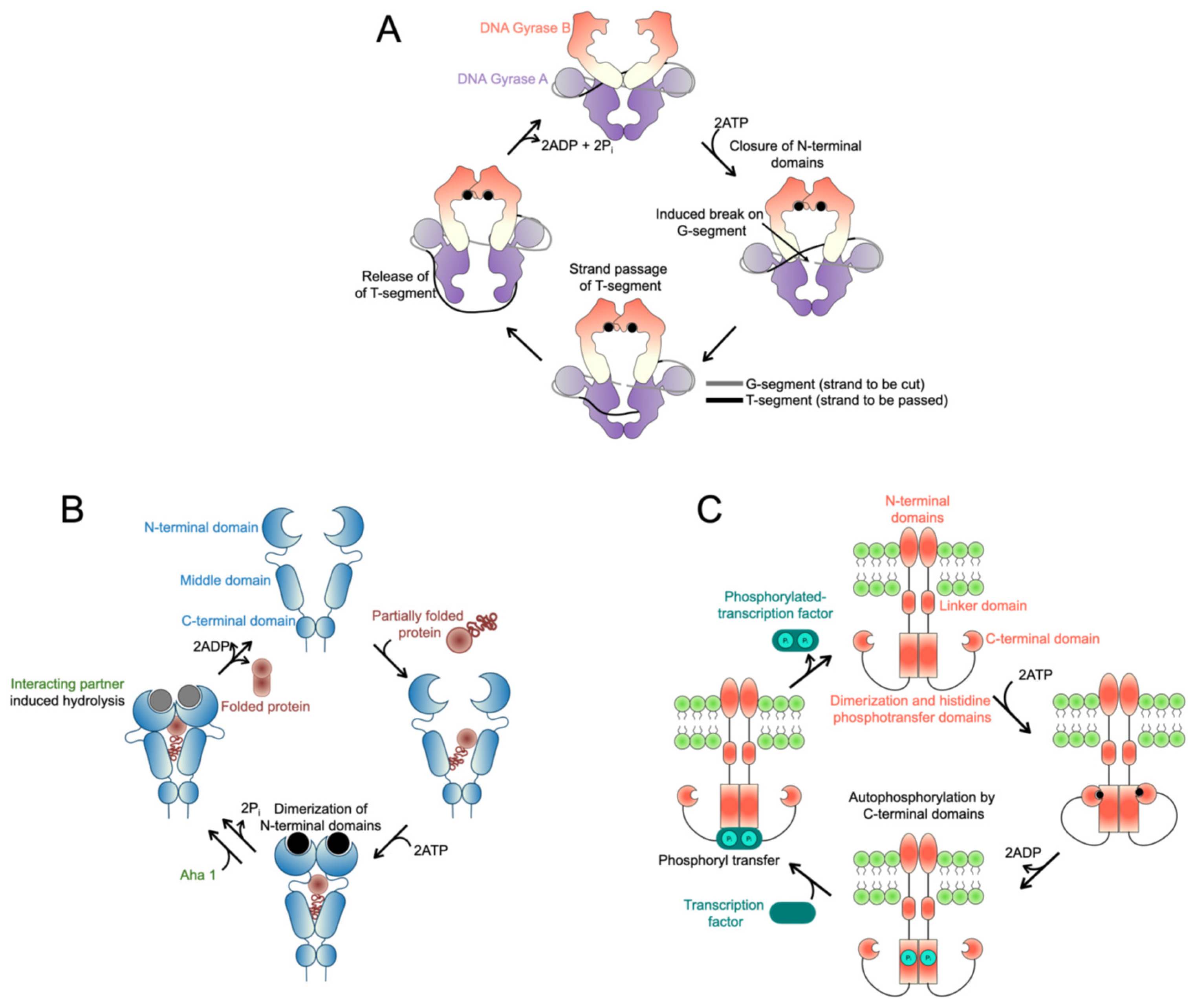

2. ATP Hydrolysis and the GHKL ATPase Paradigm

3. Mechanistic Insights from Other GHKL Family Members

3.1. DNA Gyrase B

3.2. Heat Shock Protein 90

3.3. Histidine Kinases

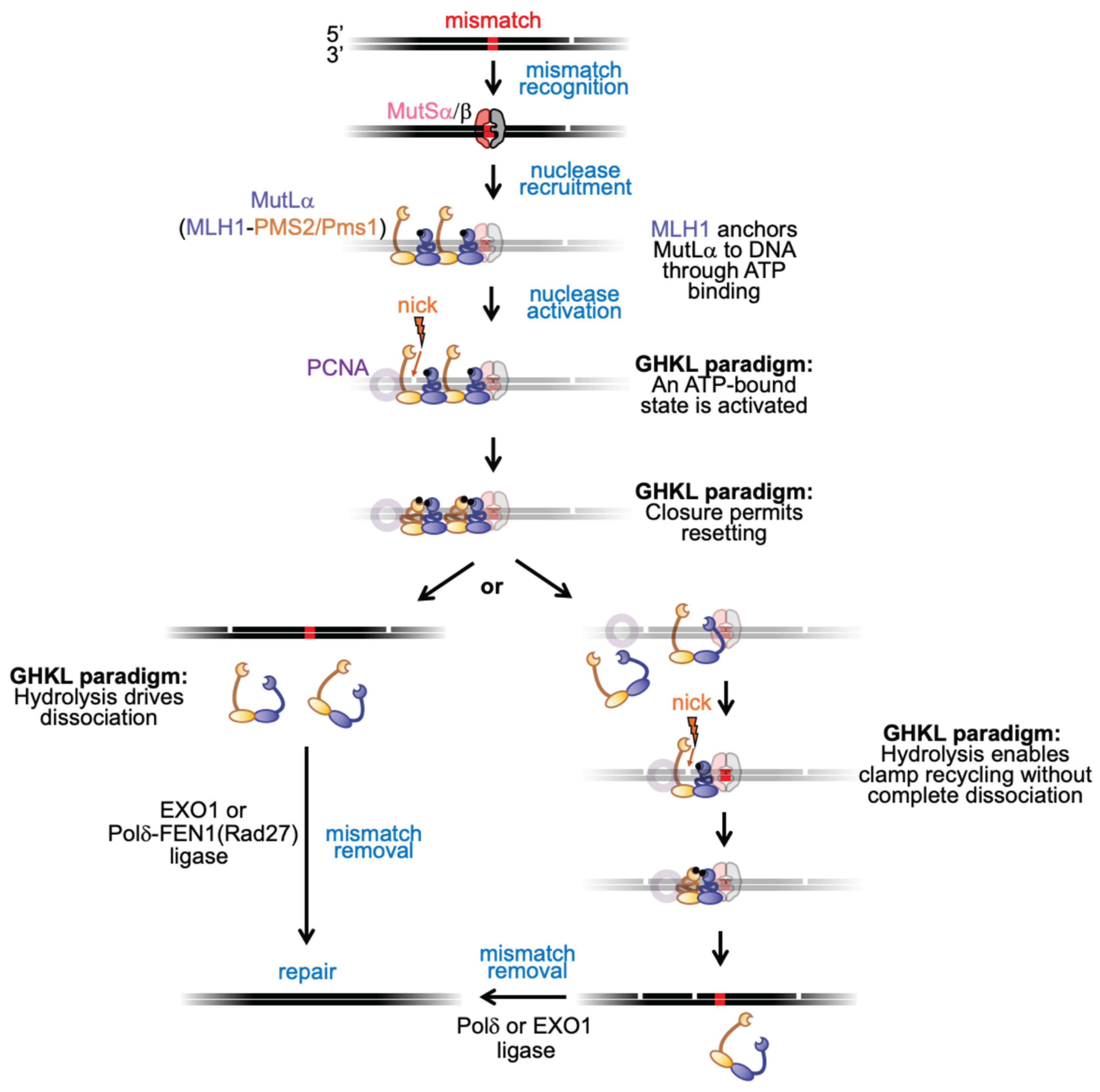

4. MutLα in MMR: Old Puzzles, New Views

5. Broader Implications and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lahue, R.S.; Modrich, P.; Au, K.G. DNA Mismatch Correction in a Defined System. Science 1989, 245, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarné, A.; Ramon-Maiques, S.; Wolff, E.M.; Ghirlando, R.; Hu, X.; Miller, J.H.; Yang, W. Structure of the MutL C-Terminal Domain: A Model of Intact MutL and Its Roles in Mismatch Repair. EMBO J. 2004, 23, 4134–4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acharya, S.; Foster, P.L.; Brooks, P.; Fishel, R. The Coordinated Functions of the E. Coli MutS and MutL Proteins in Mismatch Repair. Mol. Cell 2003, 12, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomer, G.; Buermeyer, A.B.; Nguyen, M.M.; Liskay, R.M. Contribution of Human Mlh1 and Pms2 ATPase Activities to DNA Mismatch Repair*. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 21801–21809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, M.C.; Shcherbakova, P.V.; Kunkel, T.A. Differential ATP Binding and Intrinsic ATP Hydrolysis by Amino-Terminal Domains of the Yeast Mlh1 and Pms1 Proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 3673–3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, P.T.; Liskay, R.M. Functional Studies on the Candidate ATPase Domains of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae MutLα. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000, 20, 6390–6398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junop, M.S.; Yang, W.; Funchain, P.; Clendenin, W.; Miller, J.H. In Vitro and in Vivo Studies of MutS, MutL and MutH Mutants: Correlation of Mismatch Repair and DNA Recombination. DNA Repair 2003, 2, 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronshtam, A.; Marinus, M.G. Dominant Negative Mutator Mutations in the mutL Gene of Escherichia Coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996, 24, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.R.; Erdeniz, N.; Nguyen, M.; Dudley, S.; Liskay, R.M. Conservation of Functional Asymmetry in the Mammalian MutLα ATPase. DNA Repair 2010, 9, 1209–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunkel, T.A.; Erie, D.A. Eukaryotic Mismatch Repair in Relation to DNA Replication. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2015, 49, 291–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, C.D. Strand Discrimination in DNA Mismatch Repair. DNA Repair 2021, 105, 103161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sriramachandran, A.M.; Petrosino, G.; Méndez-Lago, M.; Schäfer, A.J.; Batista-Nascimento, L.S.; Zilio, N.; Ulrich, H.D. Genome-Wide Nucleotide-Resolution Mapping of DNA Replication Patterns, Single-Strand Breaks, and Lesions by GLOE-Seq. Mol. Cell 2020, 78, 975–985.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadyrov, F.A.; Dzantiev, L.; Constantin, N.; Modrich, P. Endonucleolytic Function of MutLα in Human Mismatch Repair. Cell 2006, 126, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadyrov, F.A.; Holmes, S.F.; Arana, M.E.; Lukianova, O.A.; O’Donnell, M.; Kunkel, T.A.; Modrich, P. Saccharomyces Cerevisiae MutLalpha Is a Mismatch Repair Endonuclease. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 37181–37190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluciennik, A.; Dzantiev, L.; Iyer, R.R.; Constantin, N.; Kadyrov, F.A.; Modrich, P. PCNA Function in the Activation and Strand Direction of MutLα Endonuclease in Mismatch Repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010, 107, 16066–16071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgers, P.M.J.; Kunkel, T.A. Eukaryotic DNA Replication Fork. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86, 417–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.S.; Kunkel, T.A. Ribonucleotides in DNA: Origins, Repair and Consequences. DNA Repair 2014, 19, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, P.; Yamane, K. DNA Mismatch Repair: Molecular Mechanism, Cancer, and Ageing. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2008, 129, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modrich, P. Mechanisms in E. Coli and Human Mismatch Repair (Nobel Lecture). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 8490–8501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modrich, P. Mechanisms and Biological Effects of Mismatch Repair. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1991, 25, 229–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, C.D. Evolution of the Methyl Directed Mismatch Repair System in Escherichia Coli. DNA Repair 2016, 38, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goellner, E.M.; Putnam, C.D.; Kolodner, R.D. Exonuclease 1-Dependent and Independent Mismatch Repair. DNA Repair 2015, 32, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, N.; Kolodner, R.D. Reconstitution of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae DNA Polymerase ε-Dependent Mismatch Repair with Purified Proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017, 114, 3607–3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillon, M.C.; Lorenowicz, J.J.; Uckelmann, M.; Klocko, A.D.; Mitchell, R.R.; Chung, Y.S.; Modrich, P.; Walker, G.C.; Simmons, L.A.; Friedhoff, P.; et al. Structure of the Endonuclease Domain of MutL: Unlicensed to Cut. Mol. Cell 2010, 39, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Furman, C.M.; Manhart, C.M.; Alani, E.; Finkelstein, I.J. Intrinsically Disordered Regions Regulate Both Catalytic and Non-Catalytic Activities of the MutLα Mismatch Repair Complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 1823–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piscitelli, J.M.; Witte, S.J.; Sakinejad, Y.S.; Manhart, C.M. Mlh1-Pms1 ATPase Activity Is Regulated Distinctly by Self-Generated Nicks and Strand Discrimination Signals in Mismatch Repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, gkae1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, R.; Inouye, M. GHKL, an Emergent ATPase/Kinase Superfamily. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000, 25, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergerat, A.; de Massy, B.; Gadelle, D.; Varoutas, P.-C.; Nicolas, A.; Forterre, P. An Atypical Topoisomerase II from Archaea with Implications for Meiotic Recombination. Nature 1997, 386, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivatsan, A.; Bowen, N.; Kolodner, R.D. Mispair-Specific Recruitment of the Mlh1-Pms1 Complex Identifies Repair Substrates of the Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Msh2-Msh3 Complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 9352–9364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Räschle, M.; Marra, G.; Nyström-Lahti, M.; Schär, P.; Jiricny, J. Identification of hMutLβ, a Heterodimer of hMLH1 and hPMS1. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 32368–32375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.M.; Modrich, P. Restoration of Mismatch Repair to Nuclear Extracts of H6 Colorectal Tumor Cells by a Heterodimer of Human MutL Homologs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1995, 92, 1950–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannafino, G.; Alani, E. Coordinated and Independent Roles for MLH Subunits in DNA Repair. Cells 2021, 10, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.-F.; Kleckner, N.; Hunter, N. Functional Specificity of MutL Homologs in Yeast: Evidence for Three Mlh1-Based Heterocomplexes with Distinct Roles during Meiosis in Recombination and Mismatch Correction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1999, 96, 13914–13919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotz, G.; Raedle, J.; Brieger, A.; Trojan, J.; Zeuzem, S. hMutSα Forms an ATP-Dependent Complex with hMutLα and hMutLβ on DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furman, C.; Elbashir, R.; Alani, E. Expanded Roles for the MutL Family of DNA Mismatch Repair Proteins. Yeast Chichester Engl. 2021, 38, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosinski, J.; Steindorf, I.; Bujnicki, J.M.; Giron-Monzon, L.; Friedhoff, P. Analysis of the Quaternary Structure of the MutL C-Terminal Domain. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 351, 895–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosinski, J.; Hinrichsen, I.; Bujnicki, J.M.; Friedhoff, P.; Plotz, G. Identification of Lynch Syndrome Mutations in the MLH1–PMS2 Interface That Disturb Dimerization and Mismatch Repair. Hum. Mutat. 2010, 31, 975–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueneau, E.; Dherin, C.; Legrand, P.; Tellier-Lebegue, C.; Gilquin, B.; Bonnesoeur, P.; Londino, F.; Quemener, C.; Le Du, M.-H.; Márquez, J.A.; et al. Structure of the MutLα C-Terminal Domain Reveals How Mlh1 Contributes to Pms1 Endonuclease Site. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013, 20, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ban, C.; Yang, W. Crystal Structure and ATPase Activity of MutL: Implications for DNA Repair and Mutagenesis. Cell 1998, 95, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, C.; Junop, M.; Yang, W. Transformation of MutL by ATP Binding and Hydrolysis: A Switch in DNA Mismatch Repair. Cell 1999, 97, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arana, M.E.; Holmes, S.F.; Fortune, J.M.; Moon, A.F.; Pedersen, L.C.; Kunkel, T.A. Functional Residues on the Surface of the N-Terminal Domain of Yeast Pms1. DNA Repair 2010, 9, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zeng, H.; Lam, R.; Tempel, W.; Kerr, I.D.; Min, J. Structure of the Human MLH1 N-Terminus: Implications for Predisposition to Lynch Syndrome. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Commun. 2015, 71, 981–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spampinato, C.; Modrich, P. The MutL ATPase Is Required for Mismatch Repair. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 9863–9869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Machius, M.; Yang, W. Monovalent Cation Dependence and Preference of GHKL ATPases and Kinases. FEBS Lett. 2003, 544, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacho, E.J.; Kadyrov, F.A.; Modrich, P.; Kunkel, T.A.; Erie, D.A. Direct Visualization of Asymmetric Adenine Nucleotide-Induced Conformational Changes in MutLα. Mol. Cell 2008, 29, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePristo, M.A.; de Bakker, P.I.W.; Blundell, T.L. Heterogeneity and Inaccuracy in Protein Structures Solved by X-Ray Crystallography. Structure 2004, 12, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukui, K.; Nishida, M.; Nakagawa, N.; Masui, R.; Kuramitsu, S. Bound Nucleotide Controls the Endonuclease Activity of Mismatch Repair Enzyme MutL. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 12136–12145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Räschle, M.; Dufner, P.; Marra, G.; Jiricny, J. Mutations within the hMLH1 and hPMS2 Subunits of the Human MutLα Mismatch Repair Factor Affect Its ATPase Activity, but Not Its Ability to Interact with hMutSα. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 21810–21820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niedziela-Majka, A.; Maluf, N.K.; Antony, E.; Lohman, T.M. Self-Assembly of Escherichia Coli MutL and Its Complexes with DNA. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 7868–7880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.-W.; Han, X.-P.; Han, C.; London, J.; Fishel, R.; Liu, J. MutS Functions as a Clamp Loader by Positioning MutL on the DNA during Mismatch Repair. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedziela-Majka, A.; Maluf, N.K.; Antony, E.; Lohman, T.M. Self-Assembly of Escherichia Coli MutL and Its Complexes with DNA. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 7868–7880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claeys Bouuaert, C.; Keeney, S. Distinct DNA-Binding Surfaces in the ATPase and Linker Domains of MutLγ Determine Its Substrate Specificities and Exert Separable Functions in Meiotic Recombination and Mismatch Repair. PLoS Genet. 2017, 13, e1006722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plys, A.J.; Rogacheva, M.V.; Greene, E.C.; Alani, E. The Unstructured Linker Arms of Mlh1–Pms1 Are Important for Interactions with DNA during Mismatch Repair. J. Mol. Biol. 2012, 422, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, C.M.; Wang, T.-Y.; Zhao, Q.; Yugandhar, K.; Yu, H.; Alani, E. Handcuffing Intrinsically Disordered Regions in Mlh1–Pms1 Disrupts Mismatch Repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 9327–9341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilley, M.; Welsh, K.M.; Su, S.S.; Modrich, P. Isolation and Characterization of the Escherichia Coli mutL Gene Product. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 1000–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drotschmann, K.; Aronshtam, A.; Fritz, H.J.; Marinus, M.G. The Escherichia Coli MutL Protein Stimulates Binding of Vsr and MutS to Heteroduplex DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998, 26, 948–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bende, S.M.; Grafström, R.H. The DNA Binding Properties of the MutL Protein Isolated from Escherichia Coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991, 19, 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.C.; Wang, H.; Erie, D.A.; Kunkel, T.A. High Affinity Cooperative DNA Binding by the Yeast Mlh1-Pms1 Heterodimer1. J. Mol. Biol. 2001, 312, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega, J.; Lee, G.S.; Gu, L.; Yang, W.; Li, G.-M. Mispair-Bound Human MutS–MutL Complex Triggers DNA Incisions and Activates Mismatch Repair. Cell Res. 2021, 31, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, S.J.; Rosa, I.M.; Collingwood, B.W.; Piscitelli, J.M.; Manhart, C.M. The Mismatch Repair Endonuclease MutLα Tethers Duplex Regions of DNA Together and Relieves DNA Torsional Tension. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, 2725–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manhart, C.M.; Ni, X.; White, M.A.; Ortega, J.; Surtees, J.A.; Alani, E. The Mismatch Repair and Meiotic Recombination Endonuclease Mlh1-Mlh3 Is Activated by Polymer Formation and Can Cleave DNA Substrates in Trans. PLOS Biol. 2017, 15, e2001164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, K.C.; Wilkins, H.; Hao, P.; Li, Z.M.; Wang, B.; Burke, D.; Wu, D.; Smith, A.E.; Spaller, L.; Du, C.; et al. Dynamic Human MutSα–MutLα Complexes Compact Mismatched DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 16302–16312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, M.C.; Shcherbakova, P.V.; Fortune, J.M.; Borchers, C.H.; Dial, J.M.; Tomer, K.B.; Kunkel, T.A. DNA Binding by Yeast Mlh1 and Pms1: Implications for DNA Mismatch Repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 2025–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schofield, M.J.; Nayak, S.; Scott, T.H.; Du, C.; Hsieh, P. Interaction of Escherichia Coli MutS and MutL at a DNA Mismatch. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 28291–28299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.D.; Alani, E. Analysis of Interactions Between Mismatch Repair Initiation Factors and the Replication Processivity Factor PCNA. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 355, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Hong, Y.; McCulloch, S.; Watanabe, H.; Li, G.-M. ATP-Dependent Interaction of Human Mismatch Repair Proteins and Dual Role of PCNA in Mismatch Repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998, 26, 1173–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prolla, T.A.; Pang, Q.; Alani, E.; Kolodner, R.D.; Liskay, R.M. MLH1, PMS1, and MSH2 Interactions During the Initiation of DNA Mismatch Repair in Yeast. Science 1994, 265, 1091–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotz, G.; Welsch, C.; Giron-Monzon, L.; Friedhoff, P.; Albrecht, M.; Piiper, A.; Biondi, R.M.; Lengauer, T.; Zeuzem, S.; Raedle, J. Mutations in the MutSalpha Interaction Interface of MLH1 Can Abolish DNA Mismatch Repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, 6574–6586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selmane, T.; Schofield, M.J.; Nayak, S.; Du, C.; Hsieh, P. Formation of a DNA Mismatch Repair Complex Mediated by ATP. J. Mol. Biol. 2003, 334, 949–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, J.; Tran, P.T.; Joshi, A.; Liskay, R.M.; Alani, E. MSH-MLH Complexes Formed at a DNA Mismatch Are Disrupted by the PCNA Sliding Clamp1. J. Mol. Biol. 2001, 306, 957–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genschel, J.; Kadyrova, L.Y.; Iyer, R.R.; Dahal, B.K.; Kadyrov, F.A.; Modrich, P. Interaction of Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen with PMS2 Is Required for MutLα Activation and Function in Mismatch Repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017, 114, 4930–4935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillon, M.C.; Miller, J.H.; Guarné, A. The Endonuclease Domain of MutL Interacts with the β Sliding Clamp. DNA Repair 2011, 10, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almawi, A.W.; Scotland, M.K.; Randall, J.R.; Liu, L.; Martin, H.K.; Sacre, L.; Shen, Y.; Pillon, M.C.; Simmons, L.A.; Sutton, M.D.; et al. Binding of the Regulatory Domain of MutL to the Sliding β-Clamp Is Species Specific. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 4831–4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajakumari, K.; Aravind, K.; Balamugundhan, M.; Jagadeesan, M.; Somasundaram, A.; Brindha Devi, P.; Ramasamy, P. Comprehensive Review of DNA Gyrase as Enzymatic Target for Drug Discovery and Development. Eur. J. Med. Chem. Rep. 2024, 12, 100233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanden Broeck, A.; Lotz, C.; Ortiz, J.; Lamour, V. Cryo-EM Structure of the Complete E. Coli DNA Gyrase Nucleoprotein Complex. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, S.; Chen, C.; Ge, H.; Xie, X.S. Mechanism of Transcriptional Bursting in Bacteria. Cell 2014, 158, 314–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.Y.; Shyy, S.H.; Wang, J.C.; Liu, L.F. Transcription Generates Positively and Negatively Supercoiled Domains in the Template. Cell 1988, 53, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, P.O.; Cozzarelli, N.R. A Sign Inversion Mechanism for Enzymatic Supercoiling of DNA. Science 1979, 206, 1081–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelljes, J.T.; Weidlich, D.; Gubaev, A.; Klostermeier, D. Gyrase Containing a Single C-Terminal Domain Catalyzes Negative Supercoiling of DNA by Decreasing the Linking Number in Steps of Two. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 6773–6784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, S.; Gubaev, A.; Klostermeier, D. Binding and Hydrolysis of a Single ATP Is Sufficient for N-Gate Closure and DNA Supercoiling by Gyrase. J. Mol. Biol. 2017, 429, 3717–3729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brino, L.; Urzhumtsev, A.; Mousli, M.; Bronner, C.; Mitschler, A.; Oudet, P.; Moras, D. Dimerization of Escherichia Coli DNA-Gyrase B Provides a Structural Mechanism for Activating the ATPase Catalytic Center. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 9468–9475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Mitchenall, L.A.; Maxwell, A.; Deng, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, D.-C.; Zhang, X.-E.; et al. The Dimer State of GyrB Is an Active Form: Implications for the Initial Complex Assembly and Processive Strand Passage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 8488–8502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witz, G.; Stasiak, A. DNA Supercoiling and Its Role in DNA Decatenation and Unknotting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 2119–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampranis, S.C.; Maxwell, A. Conversion of DNA Gyrase into a Conventional Type II Topoisomerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1996, 93, 14416–14421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gubaev, A.; Klostermeier, D. DNA-Induced Narrowing of the Gyrase N-Gate Coordinates T-Segment Capture and Strand Passage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011, 108, 14085–14090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germe, T.R.; Bush, N.G.; Baskerville, V.M.; Saman, D.; Benesch, J.L.; Maxwell, A. Rapid, DNA-Induced Interface Swapping by DNA Gyrase. eLife 12. [CrossRef]

- Gross, C.H.; Parsons, J.D.; Grossman, T.H.; Charifson, P.S.; Bellon, S.; Jernee, J.; Dwyer, M.; Chambers, S.P.; Markland, W.; Botfield, M.; et al. Active-Site Residues of Escherichia Coli DNA Gyrase Required in Coupling ATP Hydrolysis to DNA Supercoiling and Amino Acid Substitutions Leading to Novobiocin Resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 1037–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kampranis, S.C.; Maxwell, A. Conformational Changes in DNA Gyrase Revealed by Limited Proteolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 22606–22614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, A.; Parente, A.C.; Bryant, Z. Structural Dynamics and Mechanochemical Coupling in DNA Gyrase. J. Mol. Biol. 2016, 428, 1833–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, J. Topoisomerase II: A Fitted Mechanism for the Chromatin Landscape. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.M.; Gamblin, S.J.; Harrison, S.C.; Wang, J.C. Structure and Mechanism of DNA Topoisomerase II. Nature 1996, 379, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, J.; Wang, J.C. The Capture of a DNA Double Helix by an ATP-Dependent Protein Clamp: A Key Step in DNA Transport by Type II DNA Topoisomerases. Cell 1992, 71, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, S.; Tu, C.-H.; Bourne, C.R. Friend or Foe: Protein Inhibitors of DNA Gyrase. Biology 2024, 13, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albakova, Z. HSP90 Multi-Functionality in Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genest, O.; Wickner, S.; Doyle, S.M. Hsp90 and Hsp70 Chaperones: Collaborators in Protein Remodeling. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 2109–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahsan, R.; Kifayat, S.; Pooniya, K.K.; Kularia, S.; Adimalla, B.S.; Sanapalli, B.K.R.; Sanapalli, V.; Sigalapalli, D.K. Bacterial Histidine Kinase and the Development of Its Inhibitors in the 21st Century. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Yu, C.; Wu, H.; Li, G.; Li, C.; Hong, W.; Yang, X.; Wang, H.; You, X. Recent Advances in Histidine Kinase-Targeted Antimicrobial Agents. Front. Chem. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, A.; Gellert, M. The DNA Dependence of the ATPase Activity of DNA Gyrase. J. Biol. Chem. 1984, 259, 14472–14480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collingwood, B.W.; Bhalkar, A.N.; Manhart, C.M. The Mismatch Repair Factor Mlh1-Pms1 Uses ATP to Compact and Remodel DNA. bioRxiv, 6333; .81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.C.; Moarefi, I.; Hartl, F.U. Hsp90. J. Cell Biol. 2001, 154, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, Y.; Chen, X.; Niu, T.; Chatterjee, A.; He, P.; Hou, G. Heat Shock Protein 90: Biological Functions, Diseases, and Therapeutic Targets. MedComm 2024, 5, e470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritossa, F. A New Puffing Pattern Induced by Temperature Shock and DNP in Drosophila. Experientia 1962, 18, 571–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiech, H.; Buchner, J.; Zimmermann, R.; Jakob, U. Hsp90 Chaperones Protein Folding in Vitro. Nature 1992, 358, 169–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamoto, J.; Mikami, I.; Tominaga, Y.; Kuchenbecker, K.M.; Lin, Y.-C.; Bravo, D.T.; Clement, G.; Yagui-Beltran, A.; Ray, M.R.; Koizumi, K.; et al. Inhibition of Hsp90 Leads to Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis in Human Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. J. Thorac. Oncol. Off. Publ. Int. Assoc. Study Lung Cancer 2008, 3, 1089–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolhe, J.A.; Babu, N.L.; Freeman, B.C. The Hsp90 Molecular Chaperone Governs Client Proteins by Targeting Intrinsically Disordered Regions. Mol. Cell 2023, 83, 2035–2044.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, A.; Dahiya, V.; Delhommel, F.; Freiburger, L.; Stehle, R.; Asami, S.; Rutz, D.; Blair, L.; Buchner, J.; Sattler, M. Client Binding Shifts the Populations of Dynamic Hsp90 Conformations through an Allosteric Network. Sci. Adv. 7. [CrossRef]

- Chiosis, G.; Digwal, C.S.; Trepel, J.B.; Neckers, L. Structural and Functional Complexity of HSP90 in Cellular Homeostasis and Disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 24, 797–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Buchner, J. Structure, Function and Regulation of the Hsp90 Machinery. Biomed. J. 2013, 36, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Southworth, D.R.; Agard, D.A. Client-Loading Conformation of the Hsp90 Molecular Chaperone Revealed in the Cryo-EM Structure of the Human Hsp90:Hop Complex. Mol. Cell 2011, 42, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.M.U.; Roe, S.M.; Vaughan, C.K.; Meyer, P.; Panaretou, B.; Piper, P.W.; Prodromou, C.; Pearl, L.H. Crystal Structure of an Hsp90–Nucleotide–P23/Sba1 Closed Chaperone Complex. Nature 2006, 440, 1013–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiau, A.K.; Harris, S.F.; Southworth, D.R.; Agard, D.A. Structural Analysis of E. Coli Hsp90 Reveals Dramatic Nucleotide-Dependent Conformational Rearrangements. Cell 2006, 127, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiosis, G.; Digwal, C.S.; Trepel, J.B.; Neckers, L. Structural and Functional Complexity of HSP90 in Cellular Homeostasis and Disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 24, 797–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prodromou, C.; Panaretou, B.; Chohan, S.; Siligardi, G.; O’Brien, R.; Ladbury, J.E.; Roe, S.M.; Piper, P.W.; Pearl, L.H. The ATPase Cycle of Hsp90 Drives a Molecular ‘Clamp’ via Transient Dimerization of the N-Terminal Domains. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 4383–4392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prodromou, C. The ‘Active Life’ of Hsp90 Complexes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Mol. Cell Res. 2012, 1823, 614–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reidy, M.; Masison, D.C. ATP Plays a Structural Role in Hsp90 Function. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuehlke, A.; Johnson, J.L. Hsp90 and Co-Chaperones Twist the Functions of Diverse Client Proteins. Biopolymers 2010, 93, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannoulis, A.; Feintuch, A.; Barak, Y.; Mazal, H.; Albeck, S.; Unger, T.; Yang, F.; Su, X.-C.; Goldfarb, D. Two Closed ATP- and ADP-Dependent Conformations in Yeast Hsp90 Chaperone Detected by Mn(II) EPR Spectroscopic Techniques. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reidy, M.; Garzillo, K.; Masison, D.C. Nucleotide Exchange Is Sufficient for Hsp90 Functions in Vivo. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siligardi, G.; Hu, B.; Panaretou, B.; Piper, P.W.; Pearl, L.H.; Prodromou, C. Co-Chaperone Regulation of Conformational Switching in the Hsp90 ATPase Cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 51989–51998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, J.K.; Hutt, D.M.; Tait, B.; Guy, N.C.; Sivils, J.C.; Ortiz, N.R.; Payan, A.N.; Komaragiri, S.K.; Owens, J.J.; Culbertson, D.; et al. Management of Hsp90-Dependent Protein Folding by Small Molecules Targeting the Aha1 Co-Chaperone. Cell Chem. Biol. 2020, 27, 292–305.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolmarans, A.; Lee, B.; Spyracopoulos, L.; LaPointe, P. The Mechanism of Hsp90 ATPase Stimulation by Aha1. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oroz, J.; Blair, L.J.; Zweckstetter, M. Dynamic Aha1 Co--chaperone Binding to Human Hsp90. Protein Sci. Publ. Protein Soc. 2019, 28, 1545–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, L.E.; Zhulin, I.B. The MiST2 Database: A Comprehensive Genomics Resource on Microbial Signal Transduction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, D401–D407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marina, A.; Waldburger, C.D.; Hendrickson, W.A. Structure of the Entire Cytoplasmic Portion of a Sensor Histidine-Kinase Protein. EMBO J. 2005, 24, 4247–4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhate, M.P.; Molnar, K.S.; Goulian, M.; DeGrado, W.F. Signal Transduction in Histidine Kinases: Insights from New Structures. Structure 2015, 23, 981–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, E.B.; Siegal-Gaskins, D.; Rawling, D.C.; Fiebig, A.; Crosson, S. A Photosensory Two-Component System Regulates Bacterial Cell Attachment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007, 104, 18241–18246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolotti, A.; Vazquez, D.B.; Almada, J.C.; Inda, M.E.; Drusin, S.I.; Villalba, J.M.; Moreno, D.M.; Ruysschaert, J.M.; Cybulski, L.E. A Transmembrane Histidine Kinase Functions as a pH Sensor. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, W.; Hao, B.; Mansy, S.S.; Gonzalez, G.; Gilles-Gonzalez, M.A.; Chan, M.K. Structure of a Biological Oxygen Sensor: A New Mechanism for Heme-Driven Signal Transduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998, 95, 15177–15182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez Chavez, R.; Alvarez, A.F.; Romeo, T.; Georgellis, D. The Physiological Stimulus for the BarA Sensor Kinase. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 2009–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez, A.F.; Georgellis, D. The Role of Sensory Kinase Proteins in Two-Component Signal Transduction. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2022, 50, 1859–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansari, M.; Idiris, F.; Szurmant, H.; Kubař, T.; Schug, A. Mechanism of Activation and Autophosphorylation of a Histidine Kinase. Commun. Chem. 2024, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casino, P.; Miguel-Romero, L.; Marina, A. Visualizing Autophosphorylation in Histidine Kinases. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szurmant, H.; White, R.A.; Hoch, J.A. Sensor Complexes Regulating Two-Component Signal Transduction. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2007, 17, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapf, J.; Sen, U.; Madhusudan; Hoch, J. A.; Varughese, K.I. A Transient Interaction between Two Phosphorelay Proteins Trapped in a Crystal Lattice Reveals the Mechanism of Molecular Recognition and Phosphotransfer in Signal Transduction. Structure 2000, 8, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casino, P.; Rubio, V.; Marina, A. Structural Insight into Partner Specificity and Phosphoryl Transfer in Two-Component Signal Transduction. Cell 2009, 139, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnowska, M.; Yan, J.; Sivalingam, G.N.; Cryar, A.; Gor, J.; Thalassinos, K.; Djordjevic, S. Autophosphorylation Activity of a Soluble Hexameric Histidine Kinase Correlates with the Shift in Protein Conformational Equilibrium. Chem. Biol. 2013, 20, 1411–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikiy, I.; Edupuganti, U.R.; Abzalimov, R.R.; Borbat, P.P.; Srivastava, M.; Freed, J.H.; Gardner, K.H. Insights into Histidine Kinase Activation Mechanisms from the Monomeric Blue Light Sensor EL346. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019, 116, 4963–4972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groothuizen, F.S.; Winkler, I.; Cristóvão, M.; Fish, A.; Winterwerp, H.H.; Reumer, A.; Marx, A.D.; Hermans, N.; Nicholls, R.A.; Murshudov, G.N.; et al. MutS/MutL Crystal Structure Reveals That the MutS Sliding Clamp Loads MutL onto DNA. eLife 2015, 4, e06744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendillo, M.L.; Hargreaves, V.V.; Jamison, J.W.; Mo, A.O.; Li, S.; Putnam, C.D.; Woods, V.L.; Kolodner, R.D. A Conserved MutS Homolog Connector Domain Interface Interacts with MutL Homologs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009, 106, 22223–22228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plotz, G.; Raedle, J.; Brieger, A.; Trojan, J.; Zeuzem, S. N-Terminus of hMLH1 Confers Interaction of hMutLalpha and hMutLbeta with hMutSalpha. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 3217–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, J.; Plys, A.J.; Visnapuu, M.-L.; Alani, E.; Greene, E.C. Visualizing One-Dimensional Diffusion of Eukaryotic DNA Repair Factors along a Chromatin Lattice. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010, 17, 932–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, J.; Wang, F.; Redding, S.; Plys, A.J.; Fazio, T.; Wind, S.; Alani, E.E.; Greene, E.C. Single-Molecule Imaging Reveals Target-Search Mechanisms during DNA Mismatch Repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, E3074–E3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, P.; LeBlanc, S.J.; Case, B.C.; Elston, T.C.; Hingorani, M.M.; Erie, D.A.; Weninger, K.R. Recurrent Mismatch Binding by MutS Mobile Clamps on DNA Localizes Repair Complexes Nearby. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 17775–17784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, R.; Sakato, M.; Sacho, E.J.; Wilkins, H.; Zhang, X.; Modrich, P.; Hingorani, M.M.; Erie, D.A.; Weninger, K.R. MutL Traps MutS at a DNA Mismatch. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015, 112, 10914–10919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hanne, J.; Britton, B.M.; Bennett, J.; Kim, D.; Lee, J.-B.; Fishel, R. Cascading MutS and MutL Sliding Clamps Control DNA Diffusion to Activate Mismatch Repair. Nature 2016, 539, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Lu, C.; Jin, Q.; Lu, H.; Chen, X.; Tian, L.; Zhang, Y.; Ortega, J.; Zhang, J.; Siteni, S.; et al. MLH1 Deficiency-Triggered DNA Hyperexcision by Exonuclease 1 Activates the cGAS-STING Pathway. Cancer Cell 2021, 39, 109–121.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsellini, A.; Lebbink, J.H.G.; Lamers, M.H. MutL Binds to 3’ Resected DNA Ends and Blocks DNA Polymerase Access. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 6224–6234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadyrov, F.A.; Genschel, J.; Fang, Y.; Penland, E.; Edelmann, W.; Modrich, P. A Possible Mechanism for Exonuclease 1-Independent Eukaryotic Mismatch Repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009, 106, 8495–8500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadyrova, L.Y.; Gujar, V.; Burdett, V.; Modrich, P.L.; Kadyrov, F.A. Human MutLγ, the MLH1–MLH3 Heterodimer, Is an Endonuclease That Promotes DNA Expansion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 3535–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogacheva, M.V.; Manhart, C.M.; Chen, C.; Guarne, A.; Surtees, J.; Alani, E. Mlh1-Mlh3, a Meiotic Crossover and DNA Mismatch Repair Factor, Is a Msh2-Msh3-Stimulated Endonuclease. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 5664–5673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores-Rozas, H.; Kolodner, R.D. The Saccharomyces Cerevisiae MLH3 Gene Functions in MSH3-Dependent Suppression of Frameshift Mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998, 95, 12404–12409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duroc, Y.; Kumar, R.; Ranjha, L.; Adam, C.; Guérois, R.; Md Muntaz, K.; Marsolier-Kergoat, M.-C.; Dingli, F.; Laureau, R.; Loew, D.; et al. Concerted Action of the MutLβ Heterodimer and Mer3 Helicase Regulates the Global Extent of Meiotic Gene Conversion. eLife 2017, 6, e21900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.S.; Hombauer, H.; Srivatsan, A.; Bowen, N.; Gries, K.; Desai, A.; Putnam, C.D.; Kolodner, R.D. Mlh2 Is an Accessory Factor for DNA Mismatch Repair in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. PLOS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harfe, B.D.; Minesinger, B.K.; Jinks-Robertson, S. Discrete in Vivo Roles for the MutL Homologs Mlh2p and Mlh3p in the Removal of Frameshift Intermediates in Budding Yeast. Curr. Biol. CB 2000, 10, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, E.M.; Baslé, A.; Cowell, I.G.; van den Berg, B.; Blower, T.R.; Austin, C.A. A Comprehensive Structural Analysis of the ATPase Domain of Human DNA Topoisomerase II Beta Bound to AMPPNP, ADP, and the Bisdioxopiperazine, ICRF193. Struct. England1993 2022, 30, 1129–1145.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yen, L.; Pastor, W.A.; Johnston, J.B.; Du, J.; Shew, C.J.; Liu, W.; Ho, J.; Stender, B.; Clark, A.T.; et al. Mouse MORC3 Is a GHKL ATPase That Localizes to H3K4me3 Marked Chromatin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016, 113, E5108–E5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douse, C.H.; Bloor, S.; Liu, Y.; Shamin, M.; Tchasovnikarova, I.A.; Timms, R.T.; Lehner, P.J.; Modis, Y. Neuropathic MORC2 Mutations Perturb GHKL ATPase Dimerization Dynamics and Epigenetic Silencing by Multiple Structural Mechanisms. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, T.; Nore, A.; Brun, C.; Maffre, C.; Crimi, B.; Guichard, V.; Bourbon, H.-M.; de Massy, B. The TopoVIB-Like Protein Family Is Required for Meiotic DNA Double-Strand Break Formation. Science 2016, 351, 943–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurzau, A.D.; Blewitt, M.E.; Czabotar, P.E.; Murphy, J.M.; Birkinshaw, R.W. Relating SMCHD1 Structure to Its Function in Epigenetic Silencing. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2020, 48, 1751–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, L.C.; Inoue, K.; Kim, S.; Perera, L.; Shaw, N.D. A Ubiquitin-like Domain Is Required for Stabilizing the N-Terminal ATPase Module of Human SMCHD1. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Dobson, R.C.J.; Lucet, I.S.; Young, S.N.; Pearce, F.G.; Blewitt, M.E.; Murphy, J.M. The Epigenetic Regulator Smchd1 Contains a Functional GHKL-Type ATPase Domain. Biochem. J. 2016, 473, 1733–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, K.D.; Berger, J.M. Structure of the Topoisomerase VI--B Subunit: Implications for Type II Topoisomerase Mechanism and Evolution. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ménade, M.; Kozlov, G.; Trempe, J.-F.; Pande, H.; Shenker, S.; Wickremasinghe, S.; Li, X.; Hojjat, H.; Dicaire, M.-J.; Brais, B.; et al. Structures of Ubiquitin-like (Ubl) and Hsp90-like Domains of Sacsin Provide Insight into Pathological Mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 12832–12842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).