Submitted:

28 October 2025

Posted:

29 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

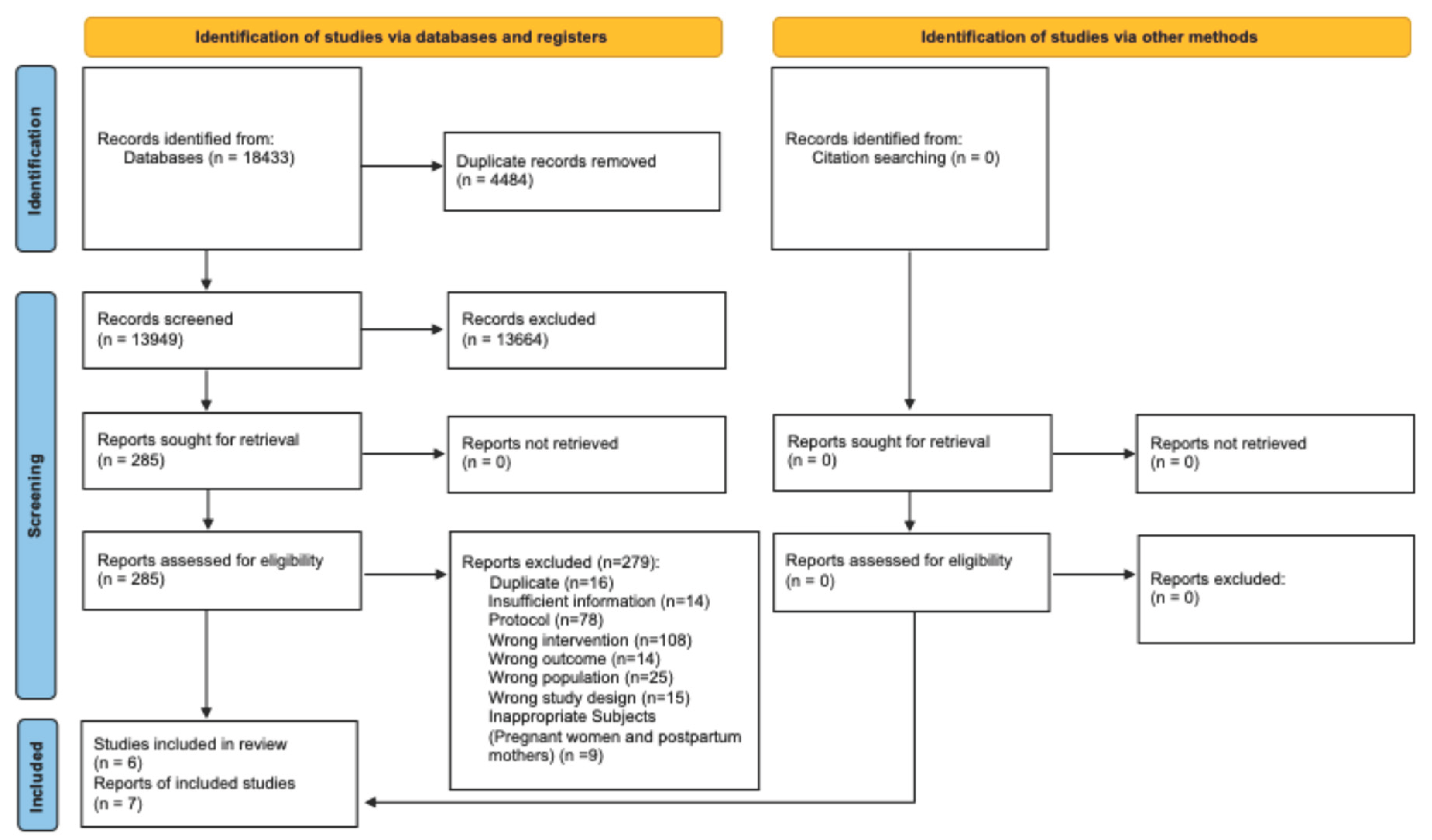

Background/Objectives: There is increased advocacy for the potential for digital applications (Apps) and the Internet of Things (IoT) to improve women’s health. We conducted a systematic review to assess and synthesize the role of Apps and the IoT in improving the health of non-pregnant women. Methods: Six databases were searched from inception to February 13, 2023. We included randomised controlled trials that assessed the effects of various Apps and the IoT with regard to improving the health of non-pregnant women in high-income countries. Our primary outcomes were health status and well-being or quality of life, and we assessed behaviour change as the secondary outcome. Screening, data extraction, and quality assessment were performed in duplicate. Study quality was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 tool. Narrative methods were used to synthesise study outcomes. Results: The search retrieved 18,433 publications and seven publications from six studies met the inclusion criteria. Participants included overweight or obese women, postmenopausal women, or women with stage I-III breast cancer. Intervention types varied across included studies but broadly included wearable or sensor-based personal health tracking digital technologies. The most commonly assessed intervention effect was on behaviour change outcomes related to promoting physical activity. Interventions administered yielded positive effects on health outcomes and well-being or quality of life in one study each, while three of the four studies that assessed behaviour change reported significant positive effects. Most included studies had methodological concerns, while study designs and methodologies lacked comparability. Conclusions: Based on our findings, the use of Apps and the IoT may be promising for facilitating behaviour change to promote physical activity. More evidence is needed to assess the effectiveness of the IoT for improving health status, well-being and quality of life among non-pregnant women.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Apps | Digital applications |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| HIC | High-income countries |

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| CINAHL | Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature |

| PICOS | Population, intervention, comparison, outcome, and study design |

| RCT | Randomised controlled trials |

| US | United States |

| GDM | Gestational diabetes mellitus |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CI | Confidence interval |

References

- Bustreo, F.; Knaul, F.M.; Bhadelia, A.; Beard, J.; Carvalho, I.A.d. Women’s health beyond reproduction: meeting the challenges. Bull World Health Organ 2012, 90, 478–478A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Lancet. A broader vision for women’s health. Lancet 2023, 402, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aktar, S.F.; Upama, P.B.; Ahamed, S.I. Leveraging Technology to Address Women’s Health Challenges: A Comprehensive Survey. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 48th Annual Computers, Software, and Applications Conference (COMPSAC); 2024; pp. 941–949. [Google Scholar]

- Pinho-Gomes, A.-C.; Peters, S.A.; Woodward, M. Gender equality related to gender differences in life expectancy across the globe gender equality and life expectancy. PLOS Glob Public Health 2023, 3, e0001214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crimmins, E.M.; Shim, H.; Zhang, Y.S.; Kim, J.K. Differences between Men and Women in Mortality and the Health Dimensions of the Morbidity Process. Clin Chem 2019, 65, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A.J.; Gupta, S.R.; Moustafa, A.F.; Chao, A.M. Sex/Gender Differences in Obesity Prevalence, Comorbidities, and Treatment. Curr Obes Rep 2021, 10, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Chen, Z.; Sun, A.; Deng, X. Gender differences in cardiovascular disease. Med Nov Technol Devices 2019, 4, 100025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertakis, K.D.; Azari, R.; Helms, L.J.; Callahan, E.J.; Robbins, J.A. Gender differences in the utilization of health care services. J Fam Pract 2000, 49, 147–152. [Google Scholar]

- Lacasse, A.; Nguena Nguefack, H.L.; Page, M.G.; Choinière, M.; Samb, O.M.; Katz, J.; Ménard, N.; Vissandjée, B.; Zerriouh, M. Sex and gender differences in healthcare utilisation trajectories: a cohort study among Quebec workers living with chronic pain. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e070509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo-Sendino, Á.; Guallar-Castillón, P.; Banegas, J.R.; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F. Gender differences in the utilization of health-care services among the older adult population of Spain. BMC Public Health 2006, 6, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, V.; Partha, G.; Karmakar, M. Gender differences in utilization of preventive care services in the United States. J Womens Health 2012, 21, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regitz-Zagrosek, V. Sex and gender differences in health. Science & Society Series on Sex and Science. EMBO Rep 2012, 13, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehran, R.; Vogel, B.; Ortega, R.; Cooney, R.; Horton, R. The Lancet Commission on women and cardiovascular disease: time for a shift in women’s health. Lancet 2019, 393, 967–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redfors, B.; Angerås, O.; Råmunddal, T.; Petursson, P.; Haraldsson, I.; Dworeck, C.; Odenstedt, J.; Ioaness, D.; Ravn-Fischer, A.; Wellin, P.; et al. Trends in Gender Differences in Cardiac Care and Outcome After Acute Myocardial Infarction in Western Sweden: A Report From the Swedish Web System for Enhancement of Evidence-Based Care in Heart Disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies (SWEDEHEART). J Am Heart Assoc 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwardhan, V.; Gil, G.F.; Arrieta, A.; Cagney, J.; DeGraw, E.; Herbert, M.E.; Khalil, M.; Mullany, E.C.; O’Connell, E.M.; Spencer, C.N.; et al. Differences across the lifespan between females and males in the top 20 causes of disease burden globally: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Public Health 2024, 9, e282–e294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiljevic-Pokrajcic, Z.; Krljanac, G.; Lasica, R.; Zdravkovic, M.; Stankovic, S.; Mitrovic, P.; Vukcevic, V.; Asanin, M. Gender Disparities on Access to Care and Coronary Disease Management. Curr Pharm Des 2021, 27, 3210–3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daher, M.; Al Rifai, M.; Kherallah, R.Y.; Rodriguez, F.; Mahtta, D.; Michos, E.D.; Khan, S.U.; Petersen, L.A.; Virani, S.S. Gender disparities in difficulty accessing healthcare and cost-related medication non-adherence: The CDC behavioral risk factor surveillance system (BRFSS) survey. Prev Med 2021, 153, 106779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, J.A.; Bianchi, D.W.; Hodes, R.; Schwetz, T.A.; Bertagnolli, M. Recent Developments in Women’s Health Research at the US National Institutes of Health. JAMA 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, A.; Womersley, K.; Strachan, S.; Hirst, J.; Norton, R. Women’s health needs beyond sexual, reproductive, and maternal health are missing from the government’s 2024 priorities. BMJ 2024, 384, q679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global strategy on digital health 2020-2025; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, J.T.; Campbell, K.L.; Gong, E.; Scuffham, P. The Internet of Things: Impact and implications for health care delivery. J Med Internet Res 2020, 22, e20135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoldemir, T. Internet Of Things and women’s health. Climacteric 2020, 23, 423–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Yang, W.; Grange, J.M.L.; Wang, P.; Huang, W.; Ye, Z. Smart healthcare: making medical care more intelligent. Global Health Journal 2019, 3, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, J.; Routray, S.; Ahmad, S.; Waris, M.M. [Retracted] Internet of Medical Things (IoMT)-Based Smart Healthcare System: Trends and Progress. Comput Intell Neurosci 2022, 2022, 7218113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.J.; Kang, S.J.; Choi, G.E. Technology-based self-management interventions for women with breast cancer: a systematic review. Korean J Women Health Nurs 2023, 29, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Huang, T. Effects of Early Nursing Monitoring on Pregnancy Outcomes of Pregnant Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus under Internet of Things. Comput Math Methods Med 2022, 2022, 8535714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recio-Rodríguez, J.I.; Rodriguez-Sanchez, E.; Martin-Cantera, C.; Martinez-Vizcaino, V.; Arietaleanizbeaskoa, M.S.; Gonzalez-Viejo, N.; Menendez-Suarez, M.; Gómez-Marcos, M.A.; Garcia-Ortiz, L.; on behalf of the, E.I.g. Combined use of a healthy lifestyle smartphone application and usual primary care counseling to improve arterial stiffness, blood pressure and wave reflections: a Randomized Controlled Trial (EVIDENT II Study). Hypertens Res 2019, 42, 852–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, K.; Nojiri, T.; Kawashima, M.; Hanai, A.; Ayaki, M.; Tsubota, K.; on behalf of the, T.R.F.J.S.G. Possible favorable lifestyle changes owing to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic among middle-aged Japanese women: An ancillary survey of the TRF-Japan study using the original “Taberhythm” smartphone app. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0248935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, H.L.; Quiroz, J.C.; Kocaballi, A.B.; Fat, S.C.M.; Dao, K.P.; Gehringer, H.; Chow, C.K.; Laranjo, L. Personalized mobile technologies for lifestyle behavior change: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Prev Med 2021, 148, 106532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, E.; Yamaji, N.; Sasayama, K.; Rahman, M.O.; da Silva Lopes, K.; Mamahit, C.G.; Ninohei, M.; Tun, P.P.; Shoki, R.; Suzuki, D.; et al. Effectiveness of the Internet of Things for Improving Pregnancy and Postpartum Women’s Health in High-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Healthcare (Basel) 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Mao, A.; Zeng, Z. Sensor-Based Smart Clothing for Women’s Menopause Transition Monitoring. Sensors 2020, 20, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, M.; Mito, A.; Waguri, M.; Sato, Y.; Abe, E.; Shimada, M.; Fukuda, S.; Sasaki, Y.; Fujikawa, K.; Sugiyama, T.; et al. Protocol for an interventional study to reduce postpartum weight retention in obese mothers using the internet of things and a mobile application: a randomized controlled trial (SpringMom). BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, R.A.; Callisaya, M.L.; Duque, G.; Ebeling, P.R.; Scott, D. Assistive technologies to overcome sarcopenia in ageing. Maturitas 2018, 112, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, L.M.; Piran, M.J.; Han, D.; Min, K.; Moon, H. A Survey on Internet of Things and Cloud Computing for Healthcare. Electronics 2019, 8, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaji, N.; Nitamizu, A.; Nishimura, E.; Suzuki, D.; Sasayama, K.; Rahman, M.O.; Saito, E.; Yoneoka, D.; Ota, E. Effectiveness of the Internet of Things for Improving Working-Aged Women’s Health in High-Income Countries: Protocol for a Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. JMIR Res Protoc 2023, 12, e45178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Sterne, J.A. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial; The Cochrane Collaboration: London, 2024; pp. 205–228. [Google Scholar]

- Cadmus-Bertram, L.A.; Marcus, B.H.; Patterson, R.E.; Parker, B.A.; Morey, B.L. Randomized trial of a Fitbit-based physical activity intervention for women. Am J Prev Med 2015, 49, 414–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, R.P.; Todd, M.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Vega-López, S.; Adams, M.A.; Hollingshead, K.; Hooker, S.P.; Gaesser, G.A.; Keller, C. Smart Walk: A Culturally Tailored Smartphone-Delivered Physical Activity Intervention for Cardiometabolic Risk Reduction among African American Women. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reutrakul, S.; Martyn-Nemeth, P.; Quinn, L.; Rydzon, B.; Priyadarshini, M.; Danielson, K.K.; Baron, K.G.; Duffecy, J. Effects of Sleep-Extend on glucose metabolism in women with a history of gestational diabetes: a pilot randomized trial. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2022, 8, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.W.; Sherburn, M.; Rane, A.; Boniface, R.; Smith, D.; O’Hazy, J. A prospective multicentre randomised controlled trial comparing unassisted pelvic floor exercises with PeriCoach System-assisted pelvic floor exercises in the management of female stress urinary incontinence. In Proceedings of the BJU INTERNATIONAL; 2016; pp. 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, B.M.; Nguyen, N.H.; Moore, M.M.; Reeves, M.M.; Rosenberg, D.E.; Boyle, T.; Vallance, J.K.; Milton, S.; Friedenreich, C.M.; English, D.R. A randomized controlled trial of a wearable technology-based intervention for increasing moderate to vigorous physical activity and reducing sedentary behavior in breast cancer survivors: The ACTIVATE Trial. Cancer 2019, 125, 2846–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallance, J.K.; Nguyen, N.H.; Moore, M.M.; Reeves, M.M.; Rosenberg, D.E.; Boyle, T.; Milton, S.; Friedenreich, C.M.; English, D.R.; Lynch, B.M. Effects of the ACTIVity and TEchnology (ACTIVATE) intervention on health-related quality of life and fatigue outcomes in breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2020, 29, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNeil, J.; Brenner, D.R.; Stone, C.R.; O’Reilly, R.; Ruan, Y.; Vallance, J.K.; Courneya, K.S.; Thorpe, K.E.; Klein, D.J.; Friedenreich, C.M. Activity Tracker to Prescribe Various Exercise Intensities in Breast Cancer Survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2019, 51, 930–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Meglio, A.; Havas, J.; Gbenou, A.S.; Martin, E.; El-Mouhebb, M.; Pistilli, B.; Menvielle, G.; Dumas, A.; Everhard, S.; Martin, A.-L. Dynamics of long-term patient-reported quality of life and health behaviors after adjuvant breast cancer chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2022, 40, 3190–3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Jo, H.-Y. Factors Associated with Poor Quality of Life in Breast Cancer Survivors: A 3-Year Follow-Up Study. Cancers 2023, 15, 5809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.M.; Cadmus-Bertram, L.; Rosenberg, D.; Buman, M.P.; Lynch, B.M. Wearable Technology and Physical Activity in Chronic Disease: Opportunities and Challenges. Am J Prev Med 2018, 54, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derbyshire, E.; Dancey, D. Smartphone Medical Applications for Women’s Health: What Is the Evidence-Base and Feedback? Int J Telemed Appl 2013, 2013, 782074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.-S.; Tsao, L.-I.; Liu, C.-Y.; Lee, C.-L. Effectiveness of Telephone-Based Counseling for Improving the Quality of Life Among Middle-Aged Women. Health Care Women Int 2014, 35, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.S.; Asch, D.A.; Volpp, K.G. Wearable Devices as Facilitators, Not Drivers, of Health Behavior Change. JAMA 2015, 313, 459–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Population (P) | Non-pregnant working-aged women Women living in high-income countries |

Studies including men only Studies including male and female population where outcome data is not separated by gender Studies of mixed population with <80% female participants |

| Intervention (I) | IoT interventions including applications, smartphones and wearable devices used to improve women’s health | IoT interventions targeting pregnancy and postpartum period only |

| Comparison (C) | Standard care No intervention Other interventions not utilising IoT |

NA |

| Outcome (O) |

Primary outcomes Health status including number of cases diagnosed or treated Well-being Quality of life Secondary outcome Lifestyle and behavioural changes |

Outcomes during pregnancy and postpartum period only |

| Study design (S) | Individual randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and cluster-RCTs Studies reported in English language Studies conducted in high-income settings |

Review articles Qualitative studies Observational studies including cross-sectional studies, case studies Commentaries, editorials, expert opinions, and letters |

| Study ID (country) | Study period | Research aim | Study design, sample size | Participant | Intervention(s) | Duration | Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lynch, et al. [43] Vallance, et al. [44] (Australia) |

July 2016 – July 2017 | To examine the efficacy of a wearable-based intervention to increase moderate to vigorous PA and reduce sedentary behaviours in breast cancer survivors | Two-arm individual RCT N=83 (Intervention=43; Control=40) |

Inactive postmenopausal women diagnosed with stage I-III breast cancer who had completed primary treatment Mean age: 61.6±6.4 |

Wearable technology activity monitor (Garmin Viofit 2) Behavioural feedback and goal-setting session Telephone-delivered behavioural counselling |

12 weeks; follow-up 12 weeks later | Delayed intervention |

| Cadmus-Bertram, et al. [39] (USA) |

2013 – 2014 | To evaluate the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of integrating the Fitbit tracker and website into a PA intervention for postmenopausal women | Two-arm individual RCT N=51 (Intervention 25; Control 26) |

Participants were overweight postmenopausal women performing 60 minutes/week of MVPA Mean age: 60.0±7.1 |

A low-touch, Fitbit-based PA intervention focused on self-monitoring/self-regulation skills | 16 weeks; follow-up 4 weeks later | Provision of a basic step-counting pedometer |

| Edwards, et al. [42] (Australia) |

Not described | To evaluate the efficacy of the PeriCoach System a novel sensor device with Web Portal and Smartphone app software designed to assist in the performance of and compliance with PFME | Two-arm individual RCT N=22 (Number of people in each group not reported) |

Females aged ≥ 18 years with stress, or mixed with predominantly stress, urinary incontinence Mean age: 42.5 |

PeriCoach System and PFME | 20 weeks | PFME |

| McNeil, et al. [45] (Canada) |

February 2017 – April 2018 | To prescribe different PA intensities using activity trackers to increase PA, reduce sedentary time, and improve health outcomes among breast cancer survivors | Single centre three armed RCT N=45 (Interventions 15, 15; Control 15) |

Women 18 years or older who have been diagnosed with stage I-IIIc breast cancer and have completed adjuvant treatment Mean age: 60.0±9.0 |

Lower or higher-intensity PA. A wrist-worn Polar A360® device to record HR/PA intensity and PA duration throughout the intervention | 12 weeks; follow-up 12 weeks later | No intervention |

| Joseph, et al. [40] (USA) |

January 2019 – August 2019 |

To examine the feasibility and acceptability of a culturally tailored, Social Cognitive Theory-based smartphone-delivered intervention designed to increase PA and reduce cardio metabolic disease risk | Two-arm individual RCT N=60 (Intervention 30; Control 30) |

Insufficiently active African American women with obesity aged 24–49 years Mean age: 38.4±6.9 |

Smart Walk smartphone-delivered PA intervention. The Smart Walk app included four key features: Personal profile pages Culturally tailored video & text-based PA promotion module Online discussion board forums PA self-monitoring feature that integrated with Fitbit activity monitors |

4 months; follow-up 4 months later | Surface-level, culturally tailored health promotion intervention without PA tracking tool, using the same smartphone application platform as the intervention group |

| Reutrakul, et al. [41] (USA) | February 2019 – July 2021 | To explore the effects of Sleep-Extend, compared to healthy living control, on sleep and glucose metabolism in women with a history of GDM and insufficient sleep | Two-arm individual RCT N=15 (intervention 9; control 6) |

Premenopausal women aged 18–45 years with a history of GDM Mean age=38.7 - 42.0 |

Fitbit wearable sleep tracker, with data accessible to the coach for guidance Fitbit smartphone application offering interactive feedback and tools Weekly didactic content via email on topics such as healthy sleep education Weekly brief telephone coaching sessions for reinforcement of didactic content, feedback based on sleep tracker data, progress review, barrier troubleshooting, and goal setting for the following week |

6 weeks | Weekly health education emails and brief weekly telephone contact with the coach |

| Study ID | Intervention | Intervention effect between groups | Primary outcomes | Secondary outcomes | Study quality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health status | Well-being or quality of life | Behaviour change | ||||

| Lynch, et al. [43] Vallance, et al. [44] |

Wearable technology activity monitor coupled with a behavioural feedback and goal-setting session and telephone-delivered behavioural counselling | Significant positive effect | Sasaki MVPA (≥2690 cpm, triaxial) | High risk of bias |

||

| Sasaki MVPA bouts (≥2690 cpm, triaxial) | ||||||

| Freedson MVPA (≥1952 cpm, uniaxial) | ||||||

| Freedson MVPA bouts (≥1952 cpm, uniaxial) | ||||||

| Matthews MVPA bouts (≥760 cpm, uniaxial) | ||||||

| Sitting time, min/d | ||||||

| Sitting time bouts, min/d | ||||||

| No significant difference | Matthews MVPA (≥760 cpm, uniaxial) | |||||

| Standing time | ||||||

| No. of sit-to-stand transitions | ||||||

| No. of steps | ||||||

| Significant positive effect | FACIT-Fatigue score (0-52) | |||||

| No significant difference | FACT-B HRQoL Breast cancer sub-scale (0-40) | |||||

| FACT-B HRQoL trial outcome index (0-96) | ||||||

| FACT-B HRQoL General (0-108) | ||||||

| FACT-B HRQoL total (0-148) | ||||||

| Cadmus-Bertram, et al. [39] | Fitbit-based PA intervention focused on self-monitoring / self-regulation skills | No significant difference | Minutes/week moderate to vigorous intensity PA (total) | Some concerns |

||

| Minutes/week moderate to vigorous intensity PA (in bouts) | ||||||

| Minutes/week light intensity PA | ||||||

| Average steps/day | ||||||

| Edwards, et al. [42] | Sensor device | Incontinence Quality-of-Life | High risk of bias | |||

| McNeil, et al. [45] | Wrist-worn Polar A360® device to record HR/PA intensity and PA duration throughout prescribed 300 min/week of lower-intensity PA or 150 min/week of higher-intensity PA |

Significant positive effect | Cardiorespiratory fitness VO2max | Moderate-vigorous intensity PA time (min/day) | Some concerns |

|

| Sedentary time (min/day) | ||||||

| No significant difference | BMI (kg/m2) | Total PA time (min/day) | ||||

| Light-intensity activity time (min/day) | ||||||

| Sleep time (min/day) | ||||||

| Joseph, et al. [40] | Smart Walk smartphone app-delivered PA intervention - Fitbit Inspire HR activity monitor | Significant positive effect | Self-reported MVPA (min/week) |

Low risk of bias | ||

| No significant difference | Systolic Blood Pressure (mmHG) | Accelerometer-measured MVPA (min/day) - 1-minute bouts | ||||

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mmHG) | Accelerometer-measured MVPA (min/day) - 10 min bouts | |||||

| Reutrakul, et al. [41] | Fitbit wearable sleep tracker | Significant positive effect | Promis fatigue T-score | IPAQ (MET- minutes/week) | High risk of bias |

|

| No significant difference | Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | PSQI | Sleep duration (minutes) | |||

| 2hr glucose (mg/dL) | GAD-7 score | Sleep efficiency (%) | ||||

| Weight change (kg) | CES-D | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).