1. Introduction

Dunhuang music and dance culture is the core component of Dunhuangology. The Dunhuang music and dance drama Silk Road Flower Rain integrates the music and dance elements of the Central Plains and the Western Regions, vividly demonstrating the cultural integration characteristics of the ancient Silk Road. The drama's creative inspiration comes from the music and dance images in Dunhuang murals, such as the Rebound Pipa Dance (backward pipa playing, playing the pipa behind the back) in Cave 112 of Mogao Grottoes Amitayurdhyana Sutra Transformation (Contemplation Sutra Transformation), the Huxuan Dance (Whirling Dance) in Cave 220 Medicine Buddha Sutra Transformation, and the Scattered Flower Dance in Cave 329 Buddhist stories (Dunhuang Academy, 2009). These dances not only restore the artistic style of music and dance in the Tang Dynasty, but also carry the diverse and inclusive Silk Road cultural spirit - the Rebound Pipa Dance symbolizes breaking cultural barriers with the gesture of reverse performance, the rotating rhythm of the Huxuan Dance reflects the artistic integration of the Western Regions and the Central Plains, and the light posture of the Scattered Flower Dance conveys the Silk Road concept of peaceful coexistence.

Silk Road Flower Rain was created and arranged by Gansu Provincial Song and Dance Theater in 1979. The main creative team includes choreographers Liu Shaoxiong, Yu Ying, composers Han Zhongcai, Hu Tingxi, etc. The play is based on the images of flying and providers in Dunhuang murals. It tells the story of Tang Dynasty painter Zhang and his daughter Yingniang protecting Dunhuang murals and spreading Dunhuang culture. After its premiere in 1979, the play triggered a wave of academic research on Dunhuang music and dance, which directly promoted the all-round development of Dunhuang studies in the 1980s.

Existing studies explore the development of Dunhuang music and dance from multiple dimensions: Dong Xijiu (1979, 1982) started from Dunhuang murals to analyze the artistic characteristics and historical origin of music and dance in the Tang Dynasty; Ye Dong (1982, 1985) and Xi Zhenguan (1983, 1992a, 1992b) focused on the deciphering and restoration of Dunhuang music scores, providing historical support for music and dance creation; Chen Yingshi (1983, 1985, 1988a, 1988b) studied the generation mechanism and aesthetic system of Dunhuang music and dance from the perspective of musicology. At the same time, scholars have also actively explored in the field of Dunhuang music and dance education innovation: Niu Longfei (1991) and Zheng Ruzhong (1997, 2002) built the inheritance system of Dunhuang music and dance; Wang Kefen et al. (2007) published a monograph on Dunhuang's musical and dance murals; Gao Jinrong (2000, 2002, 2008) compiled teaching materials and cultivate professional talents, laying the foundation for the educational practice of Dunhuang music and dance.

Dunhuang music and dance culture is a treasure of ancient Chinese artistic heritage. Artists and scholars in the domestic education circle are keenly aware that building a characteristic music and dance major and integrating this cultural heritage into college art education is of great significance to expanding students' artistic vision, improving aesthetic literacy, and cultivating national pride. In the management of art education in colleges and universities, inheriting and promoting the value of Dunhuang music and dance culture is a key link in improving students' artistic literacy and promoting national culture.

Professors He Yanyun and Shi Min of Beijing Dance Academy were the early stars of Silk Road Flower Rain (He Yanyun and Shi Min played Yingniang successively). Follow-up research has been carried out around the teaching of Dunhuang music and dance, and fruitful results have been achieved: He Yanyun (2009) wrote Dunhuang Dance Training and Performance Course to systematically sort out the basic movements and training methods of Dunhuang dance; Shi Min (2012, 2023) published Dunhuang Dance Course: Music and Dance Image Presentation and Dunhuang Dance Course: Male Music and Dance Image Presentation respectively, and offered Dunhuang music and dance courses in the undergraduate and graduate teaching of Beijing Dance Academy. In addition, Lanzhou College of Arts and Sciences has established a Dunhuang Dance Inheritance and Development Research Center, and Northwest Normal University has established a Dunhuang College, both of which regard Dunhuang music and dance as the characteristic direction of school art education.

At present, the study of Dunhuang music and dance in China is still in the stage of artistic ontology research, and the realization path of its social value has not been deeply explored. At the same time, in the art education management system of colleges and universities, the inheritance and development of Dunhuang music and dance culture face many practical challenges.

First of all, the inheritance of Dunhuang music and dance requires the support of professional talents, especially those who master the deciphering of ancient music scores and the restoration of traditional dances. In history, Dunhuang music and dance terms were mostly recorded in Dunhuang scriptures, such as the dance notation in the Dunhuang document No. 3808, which uses words to describe movements, and its symbol system is very different from modern dance notation; and the rhythm and mode interpretation of some music scores (such as the Dunhuang Pipa notation) are far more difficult than ordinary literature texts, requiring knowledge of musicology, history, and philology at the same time, resulting in a long and difficult training period for professional talents.

Secondly, in the construction of the art education system in colleges and universities, a group of senior artists and scholars (such as Ye Dong and Xi Zhenguan) have passed away one after another, and their accumulated practical experience and academic achievements have not been fully passed on. This directly leads to the loss of Dunhuang music and dance teaching resources (such as oral historical materials and exclusive teaching materials), the discontinuity of the teaching staff, and the lag in the construction of practical platforms (such as Dunhuang music and dance creation and arrangement bases), making it difficult to meet the needs of talent training.

Third, under the impact of modern culture, the influence of traditional music and dance culture on young people has gradually weakened, and this problem is particularly prominent in the inheritance of Dunhuang music and dance. From the 1980s to the end of the 20th century, scholars such as Ye Dong (1982, 1985), Xi Zhenguan (1983, 1992a, 1992b), and Chen Yingshi (1983, 1985, 1988a, 1988b) made breakthroughs in the field of ancient music score research in Dunhuang, but few young scholars have continued this research direction since then, resulting in the risk of intergenerational inheritance of traditional Dunhuang music and dance skills.

The existing research focuses on the art history and dance form of Dunhuang music and dance but lacks quantitative research on its social value. Therefore, this study collects data through questionnaires and uses ridge regression model to quantitatively analyze the impact of social cultural identity and social participation on the social value of Silk Road Flower Rain.

In this context, in order to cope with the above challenges, cultivate cultural self-confidence, and realize the effective inheritance of Dunhuang music and dance culture, this study takes the representative work of Dunhuang music and dance Silk Road Flower Rain as the core research object, and carries out two aspects of work: on the one hand, excavate the cultural connotation of Dunhuang music and dance (an important branch of Dunhuang studies), empirically analyze the impact of social cultural identity and social participation on its social value through questionnaire survey and ridge regression model, and clarify the core driving factors of Dunhuang music and dance social value; on the other hand, based on empirical conclusions, put forward optimization strategies for the development model of Dunhuang music and dance culture, including strengthening regional cultural exchanges, organizing community activities to enhance social participation, carrying out education and training to encourage public participation, using modern technologies such as artificial intelligence and virtual reality to innovate cultural communication methods, and incorporating Dunhuang music and dance courses into the education system to strengthen youth Cultural education, relying on the Belt and Road Initiative to enhance the global influence of Dunhuang culture through policy support and international cooperation.

The ultimate goal of this study is to provide reference for scholars and administrators in the field of Dunhuang Studies, and to provide practical guidance for the modernization transformation and social value enhancement of Dunhuang traditional music and dance cultural heritage.

The analysis methods of Likert scale data include ordered regression, structural equation model, etc. This study chooses linear regression with penalty terms (ridge regression), mainly based on two reasons: first, the social value composite dependent variable in this study is tested to be approximately continuous distribution (Shapiro-Wilk test p>0.05), which satisfies the basic assumption of linear regression; second, ridge regression deals with the problem of multicollinearity between conceptual correlation indicators through L2 regularization, which can retain information completely without excluding important variables.

2. Literature and Research Hypothesis

Achievements of Dunhuang studies. The work on the study of Dunhuang Grotto art, Complete Collection of the Dunhuang Grottoes (Dunhuang Academy, 2016), was compiled and published by the Dunhuang Academy. The content covers art, religion, archaeology, documents, cultural relics protection, etc., and can be used by researchers in related fields. The mural music and dance art in the Dunhuang caves is not only a unique form of art but also provides a comprehensive window for people to understand ancient culture and art. It embodies the integration of multiple academic disciplines. Apart from clearly displaying aesthetics, costume studies, musicology, dance, and painting, it also encompasses elements from architecture (Sun & Sun, 2001; Fan & Chai et al., 2011; Fan,2014; Peng, 2018), material science (Su & Zhang, 2018; Yin & Sun, 2019; Zhang et al., 2022), mechanics (Li & Du, 2016; Wang & Yan, 2016; Yuan & Shi, 2000; Zhang, 2022; Hu & Brimblecombe, 2023; Zhang & Tang et al., 2024), archaeology (Fan, 2014; Chai & Liu, 2019; Rong, 2024), history (Ning, 2020; Rong, 2024), sociology (Fan, 2014; Rong, 2024), and Buddhism (Ning, 2004; Rong, 2024), reflecting the profound knowledge and skills of ancient laborers.

When audiences appreciate the music and dance art in the murals of Dunhuang Grottoes, they are first attracted by the aesthetic value of the grotto architectural structures and the ingenious application of mechanical principles (for example, the arch structure of Cave 305 in Mogao Grottoes not only ensures stability but also provides a complete display space for the music and dance murals). Secondly, the pigment preparation techniques (such as the mineral purification of lapis lazuli and malachite), the exquisite painting skills (such as the color gradation of the ribbons of the Flying Apsaras), and the integration of aesthetics and dance in the music and dance scenes depicted in the murals all leave a deep impression. The detailed depictions in the murals of characters' costumes (such as the Ru skirt of the Tang Dynasty and the Hu costumes of the Western Regions) and dance details (such as the hand gestures of the Rebound Pipa Dance and the foot postures of the Huxuan Dance) not only present a rich visual experience but also reflect the social features and aesthetic orientations of that time.

Culture identity theory. Social identity theory was proposed by Tajfel and Turner (1979) and Tajfel (1982), which defines sociocultural identity as the degree of belonging and recognition of the social culture to which an individual or group belongs, while social participation refers to individuals actively engaging in social activities and assuming social responsibilities. When people strongly identify with their social culture, they are more likely to participate in cultural inheritance and social welfare activities. These two elements play a key role in cultural heritage preservation and the realization of social values.

Cultural identity is the core driving force behind cultural heritage preservation, with stronger cultural identity enhancing public enthusiasm for participating in cultural protection efforts (Smith, 2006). In addition, Putnam (2000) also emphasized the importance of social participation in accumulating social capital and realizing cultural value. He also discussed ways to rebuild community involvement, including encouraging people to return to social activities and strengthening economic and public policy support for communities. In intangible cultural heritage and cultural identity, Ma and Gao (2021) put out that the establishment of an intangible cultural heritage identity system requires the combined efforts of governments, experts, scholars, heritage inheritors, and the general public. Fan (2024) researched the relationship between university music and dance performances and social cultural inheritance, emphasizing that staging music and dance dramas on university campuses function not only as an engaging performance but also as a crucial vehicle for social cultural inheritance. It contributes to the preservation and promotion of cultural values, historical memory, and social sentiment. Research findings on the positive impact of social participation in traditional cultural inheritance reveal that active social engagement can enhance the social influence and recognition of traditional culture.

In addition, in the context of globalization, cultural identity has become the most profound form of identity. Citizenship theory emphasizes the importance of individual participation in public affairs, arguing that active social participation can enhance social cohesion and improve public well-being, and that participation in cultural activities and heritage protection is an important form of civic participation, which can simultaneously promote cultural heritage inheritance and innovation. Yan and Dong (2023) propose that the formation of individual cultural identity is the core driving force for cultural identity education, and cultural experience is a vivid embodiment of cultural identity, which plays a "gas station" role in the localization process of cultural exploration education.

Social cultural identity can enhance public understanding and recognition of the social value of Silk Road Flower Rain. When people have a deep recognition of the cultural connotations and social significance represented by Silk Road Flower Rain, they are more willing to support and participate in its inheritance activities. This sense of identity can also promote cultural exchanges among different groups, strengthening social cohesion. Lin (2024) explored the relationship between digital preservation of museum artifacts and social participation through a dedicated study on the former. The research analyzed the role and significance of social participation in digital artifact preservation, revealing that social engagement not only facilitates the smooth implementation of digital preservation initiatives for artifacts but also enables the sharing and dissemination of cultural resources. Furthermore, it contributes to raising public awareness of historical culture and advancing both societal development and cultural heritage inheritance.

Research gaps and research hypotheses. Existing literature seldom integrates social capital theory (Putnam, 2000) and cultural identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) into empirical modeling of cultural heritage values, this study proposes empirical analysis of the social value of Dunhuang Music and Dance Drama Silk Road Flower Rain. To deeply preserve traditional cultural content and innovate cultural dissemination methods can enhance cultural value. By delving into cultural depth, the spiritual richness of the work is elevated, and innovative dissemination methods expand its influence. Based on the literature review and theoretical basis, this study proposes the following research hypotheses (H) and Null hypothesis (H0):

H1: Sociocultural identity has a significant positive impact on the social value of Silk Road Flower Rain; H01: Sociocultural identity has no significant impact on the social value of Silk Road Flower Rain.

H2: Social participation has a significant positive impact on the social value of Silk Road Flower Rain; H02: Social participation has no significant impact on the social value of Silk Road Flower Rain.

In the future, the above hypotheses will be empirically tested through data analytic to provide scientific basis and strategic suggestions for the inheritance and improvement of the social value of Silk Road Flower Rain.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Questionnaire design and survey

To comprehensively evaluate the social value of

Silk Road Flower Rain, we designed a detailed multi-value assessment questionnaire that encompasses various specific indicators. This questionnaire provides data support for the quantitative analysis of these indicators.

Table 1 is the structure of the questionnaire and the survey indicators for each value dimension; the questionnaire is also divided into five levels: 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, respondents only need to select the level they agree with.

The selection of the four core indicators in the questionnaire was based on two key considerations to ensure their scientific rigor and validity. First, it referenced mature scales in existing Dunhuang culture research. For example, Fan Xueqin (2024) used cultural exchange effectiveness and community cultural participation as core indicators in the study of the correlation between university music and dance performances and social cultural inheritance; this questionnaire drew on such indicator frameworks to align with academic consensus. Second, a pre-survey was conducted with 30 respondents (including 10 university teachers, 10 students, and 10 cultural workers) before the formal survey. The pre-survey data were subjected to reliability and validity tests: the Cronbach's α coefficient of the questionnaire was 0.87, indicating good internal consistency; the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test value was 0.82, and the Bartlett spherical test result was significant (p<0.001), confirming that the indicators were suitable for factor analysis. Based on the feedback from the pre-survey, the expression of individual items was optimized (e.g., revising influences Dunhuang culture to influences the public's sense of belonging and recognition toward Dunhuang culture to enhance clarity), and the final four indicators were determined.

The formal survey uses a combination of stratified sampling and convenient sampling to select three groups of college teachers/sociologists, college students, art workers and ordinary practitioners. We distributed this survey questionnaire to 150 respondents, including 50 university teachers and social scholars, 50 university students, and 50 artists and general workers, to ensure the representativeness of the sample. After collecting the questionnaires, we first conducted validity screening of the 123 returned questionnaires (with an effective recovery rate of 82%) based on the following criteria: (1) excluding questionnaires with incomplete answers (e.g., missing more than 2 items); (2) excluding questionnaires with obvious response biases (e.g., selecting the same scale option for all items); (3) excluding questionnaires with logical contradictions (e.g., rating promotion of cross-regional cultural exchanges as extremely effective but rating social cultural identity as no influence at all, which was judged irrational through cross-validation). After screening, we obtained 100 valid responses after quality control (attention checks and completion-time thresholds).

All analyses use the sample (

n =100). Normality diagnostics are reported as robustness evidence rather than an inclusion criterion, this sample size meets the minimum requirement of sample size≥10 times the number of independent variables (Hastie et al., 2009) for ridge regression (with 6 independent variables in this study), ensuring the reliability of the model analysis. The descriptive statistics of the 100 final samples are shown in

Table 2.

3.2. Data Processing and Variables Definition

Data collection and standardization. We collected scores of 100 respondents for the four questions outlined in the social value survey (

Table 1). To eliminate the influence of different indicator dimensions (e.g., influence degree and importance degree) on the model results, all independent variables (the scores for Questions 1–4, as well as social participation and social recognition) were standardized using the

Z-score method. The selection of the

Z-score method instead of other standardization methods (e.g., Min-Max) was based on the following theoretical and practical considerations: First,

Z-score standardization, as a data normalization technique, can be applied to any numerical data while preserving the relative distribution. In this study, because the Shapiro–Wilk test indicated the survey data did not significantly deviate from a normal distribution, the use of Z-score standardization is particularly appropriate. In this case, the standardized data not only retain their relative ordering but also follows a standard normal distribution, allowing us to fully leverage its statistical properties (for example, applying the empirical rule or conducting parametric tests). (Wooldridge, 2021). Second, the

Z-score transforms each feature to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1, which can eliminate the influence of different dimensions (e.g., the difference between 1 to 5 points for influence degree and 1 to 5 points for importance degree) and ensure that the regression coefficients of each independent variable are comparable. Third, it is a common practice to approximate reliable Likert aggregated quantities as continuous quantities. The Z-score does not change the measurement level but unifies the dimension/stabilizes the estimation, while the Min-Max method may compress the data range and reduce the differences between variables. The specific formula for the

Z-score method is as follows:

where:

X is the original value of a feature.

μ is the mean of the feature across all data points.

σ is the standard deviation of the feature across all data points.

Z is the standardized score.

Measures and scaling. All predictors (X1–X6) were Z-standardized (mean=0, standard deviation =1) to harmonize scales and stabilize penalized estimation. Z-standardization does not change the measurement level of Likert items. Treating aggregated Likert-type scales as approximately continuous is common when reliability is adequate and distributions are not severely skewed, the outcome Y remains on the original 1–5 scale; under this scaling, the intercept approximates mean(Y) when predictors are at their means.

Variables definition: In the social value survey that we conducted for Silk Road Flower Rain, the dependent variable (DV) is social value, denoted as Y. This variable reflects our overall assessment of Silk Road Flower Rain's impact on society. The independent variables (IVs) include social cultural values related to Questions 1, 2, 3, and 4, which we denote as X1, X2, X3, and X4. We also include two additional variables: Social Participation, denoted as X5, which indicates the level of involvement of respondents in social and cultural activities. We calculate this score as the average of the scores for Questions 2 and 3 (X2 and X3). Additionally, Social Recognition, denoted as X6, reflects respondents' level of approval of Silk Road Flower Rain, and we calculate this score as the average of the scores for Questions 1 and 4 (X1 and X4).

3.3. Theoretical Basis and Dimensional Rationality for Cultural Identity and Youth Cultural Education

The integration of Sociocultural Identity (X1) and Cultural Education for Younger Generations (X4) into the composite Social Recognition (X6) draws on Smith’s heritage theory and the intergenerational transmission perspective (Smith, 2006). Smith emphasizes that the social value of heritage is dynamic: it depends on the current recognition of cultural meanings and on their future continuity through education-mediated transmission.

On the identity dimension (

X1),

Silk Road Flower Rain embodies meanings such as intercultural dialogue and inclusiveness. Our questionnaire items (e.g., perceived accuracy in conveying Dunhuang’s inclusive spirit; strengthened pride in traditional culture) are designed to capture acceptance of these meanings. In the ridge specification reported in

Section 4, the coefficient for Cultural Identity (

X1) is positive (≈0.17), indicating a positive association with perceived social value under our modeling assumptions (inference based on permutation + bootstrap with Holm adjustment).

On the education dimension (X4), both formal curricula (e.g., Dunhuang dance modules in higher education; aesthetic education in primary and secondary schools) and interactive formats (e.g., youth versions of the production; digital practice tools) serve as channels through which meanings are internalized by younger audiences, the future subjects of identity in Smith’s terms. Descriptively, respondents who reported participation in Dunhuang-related educational activities assigned higher social-value ratings on average than non-participants (mean difference≈0.98 on a 1–5 scale; descriptive comparison, non-causal). Bringing X1 (current recognition) together with X4 (future-oriented cultivation) captures the full-cycle aspect of recognition emphasized by Smith (2006).

3.4. Theoretical Basis and Empirical Connection for the Operational Indicators of Social Participation

The choice of community cultural activities (X2) and cross-regional cultural exchanges (X3) as the operational indicators for Social Participation (X5) is grounded in social capital theory and cultural communication theory, aligns with Putnam’s framework on bonding and bridging social capital (Putnam, 2000). At the community level, frequent, accessible cultural activities (e.g., Dunhuang music-and-dance workshops and abridged performances of Silk Road Flower Rain in neighborhood venues) cultivate familiarity and attachment to cultural meanings in everyday settings. Such participation can support the diffusion of cultural symbols and strengthen local networks that carry social value.

Beyond local engagement, cross-regional exchanges function as boundary-spanning mechanisms that extend cultural reach and visibility. For a production whose narrative centers on the Silk Road, touring and inter-regional collaborations (e.g., performances in Xi’an, Beijing, and Shanghai; exchanges that juxtapose Dunhuang dance with local forms) represent natural opportunities for bridging ties. In our data, respondents who reported participating in activities associated with cross-regional exchange related to Silk Road Flower Rain rated social value higher on average than non-participants (mean difference≈1.23 on a 1–5 scale; descriptive comparison). This pattern is associated and consistent with the theoretical expectation that both localized participation and boundary-spanning exchanges contribute to perceived social value; it does not imply causality.

The integration of cultural identity and cultural education for younger generations into social recognition (X6) also takes into account the complementarity between the two: Cultural identity is the current value foundation, and cultural education for younger generations is the future value guarantee. Only the combination of the two can fully reflect the full-cycle dimension of the social recognition of Silk Road Flower Rain. This design not only conforms to Smith’s (2006) dynamic perspective on cultural heritage protection but also makes the measurement of social recognition more comprehensive and theoretically in-depth, avoiding the short-sightedness of identity that may be caused by single-dimensional measurement. These theoretical insights justify the inclusion of X2, X3 as social participation indicators and X1, X4 as social recognition indicators.

3.5. Model Selection and Model Test

Model selection. Ridge regression addresses strong correlations among conceptually related indicators and their composites while retaining all theoretically relevant predictors. We select the penalty λ by repeated 10-fold cross-validation (50 repetitions), minimizing mean cross-validated MAE (ties broken by the smallest λ). The optimal λ value is determined to be 0.15, which significantly alleviates multicollinearity (average VIF drops to 2.3 < 3).

Model performance. The model demonstrates strong out-of-sample explanatory power, with mean cross-validated R

2≈0.905(SD≈0.055) and mean cross-validated RMSE≈0.22 on the 1–5 outcome scale (

Table 2). These metrics were computed on held-out folds; we do not interpret MSE as a percentage of variance. Correlation diagnostics and the penalty path indicate that ridge regression stabilizes estimates in the presence of multicollinearity.

Validation and inference. We assessed generalization using repeated cross-validation and 100 iterations of a random 80/20 holdout. No artificial noise was added to Y in the primary analyses. Uncertainty was quantified with 10,000-sample permutation tests (labels shuffled, X held fixed) and 10,000-sample stratified bootstraps to construct two-sided 95% percentile confidence intervals, with Holm–Bonferroni correction applied for multiple slope comparisons. Adjusted p-values are reported to four decimal places (minimum reportable value = 0.0001).

4. Results and Discussions

All data analyses in this study were conducted in Python. The scikit-learn library was used for model fitting and cross-validation, the NumPy/Pandas libraries for data processing, and custom programs for implementing permutation tests and Bootstrap resampling.

4.1. Average scores of respondents

The mean scores and standard deviations for respondents’ ratings of the social value dimensions of

Silk Road Flower Rain are shown in

Table 3. Overall, scores for all dimensions exceed 3 (the medium level). Among them, enhancement of community cultural activities (X

2) received the highest score (3.24), while youth cultural education (X

4) received the lowest (2.82). This reflects that the public believes that the role of

Silk Road Flower Rain at the community level has initially emerged, but there is still much room for improvement in the field of adolescent education.

4.2. Ridge Regression Model Building

Ridge regression is performed using Python software, the regression equation is obtained as follows:

where:

Y represents social value.

X1,

X2,

X3,

X4 correspond to the scores for questions 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively.

X5 represents social participation (average of questions 2 and 3).

X6 represents Social Recognition (average of questions 1 and 4).

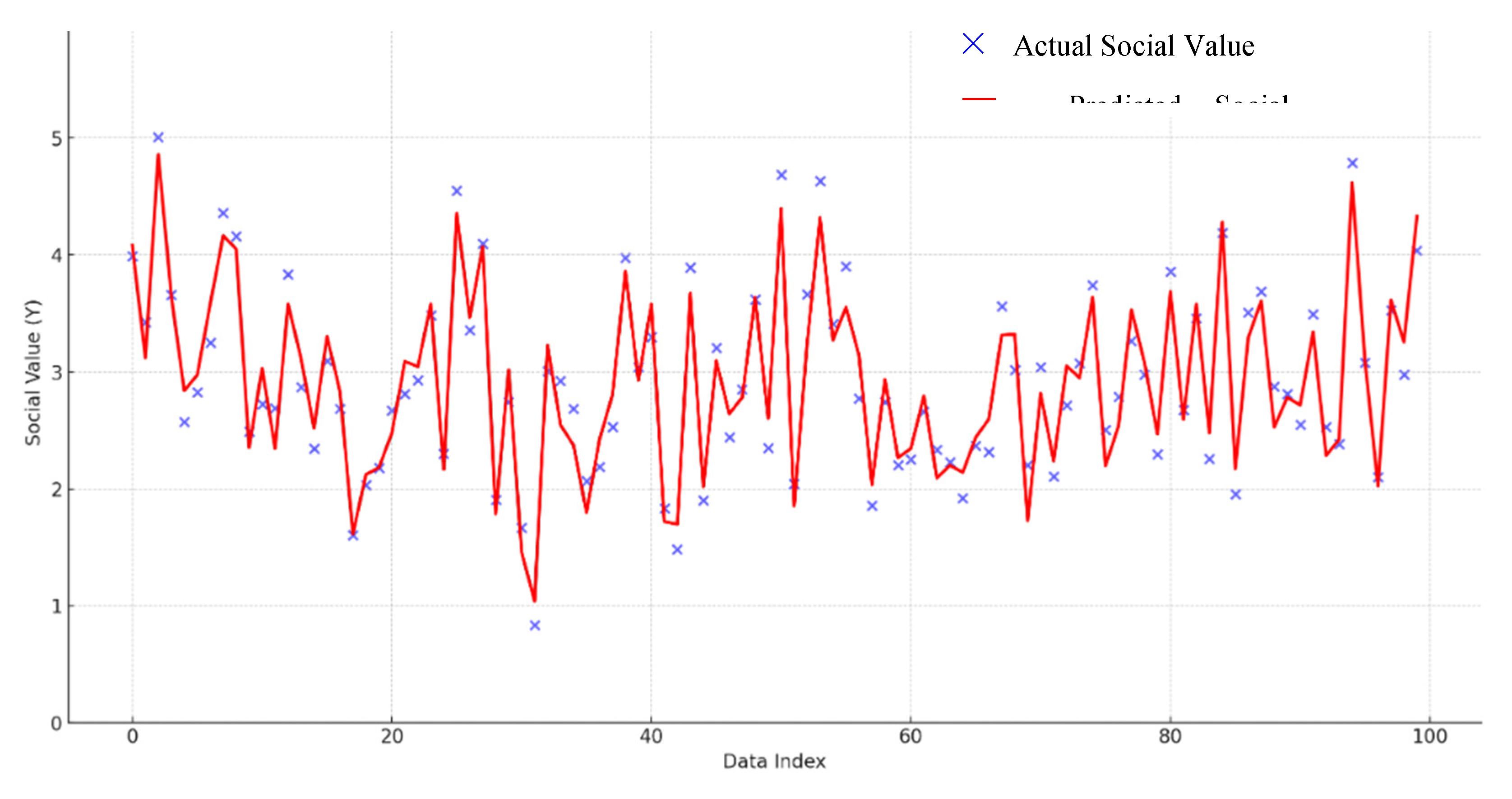

A ridge regression model is used for predictions: Input standardized new data and use the trained ridge regression model to predict social value. Predicting social value (solid line) with 95% bootstrap confidence band (shaded) are shown in

Figure 1. Estimates are from ridge regression with λ selected by repeated 10-fold cross-validated (50 repetitions). Predictors are

Z-standardized; the outcome is on the original 1–5 scale. Bands are based on 10,000 stratified bootstrap resamples.

Figure 1 presents the ridge regression fitting curve between standardized independent variables (

X1-

X6) and social value (

Y), with a 95% bootstrap confidence band (shaded area). The fitting curve of social participation (

X5) has the steepest slope (0.28), consistent with its highest regression coefficient, while the curve of youth cultural education (

X4) has the gentlest slope (0.16), reflecting its weak driving effect. All curves are within the 95% confidence band, indicating stable predictive performance of the model.

4.3. Ridge Regression Model Test

4.3.1. Overall fitting test

The results of the cross-validation show that the average Mean Squared Error (MSE) is 0.0491 with a standard deviation of 0.0093, and the average R2 value is 0.9052 with a standard deviation of 0.0550. This indicates that the model still explains the variability of the target variable well, accounting for approximately 90% of its variability. The model performance remains quite good, and the small standard deviations of both the MSE and R2 suggest that the model's performance is relatively stable across different folds.

4.3.2. Coefficient significance test

Because ridge regression does not yield OLS-style closed-form standard errors, we quantify uncertainty via 10,000-sample permutation tests (labels shuffled; X fixed) and 10,000-sample stratified bootstrap to construct two-sided 95% percentile CIs. The adjusted p-values and 95% confidence intervals for the coefficients of each variable are obtained: the adjusted p-values of all variables are < 0.05, and none of the 95% confidence intervals include 0, indicating that the positive impacts of each variable on social value are statistically significant. Among them, We control the family-wise error rate using Holm-Bonferroni and the adjusted p-value for social participation (X5) is < 0.0001, with a confidence interval of [0.25, 0.31], making it the variable with the most significant impact; the adjusted p-value for cultural education of adolescents (X4) is 0.0231, with a confidence interval of [0.12, 0.20], and its impact is relatively weaker.

4.4. Model Interpretation

The regression coefficients for X1, X2, X3, X4, X5, and X6 are 0.1734, 0.2009, 0.1955, 0.1607, 0.2798, and 0.2302 in equation 1, respectively. All these coefficients are positive, indicating a positive correlation between the independent variables and the dependent variable (social value Y). As these variables increase, social value also increases.

Social Participation (X5). With the highest coefficient (0.2798), it indicates that for each increase of 1 standardized unit in social participation, the social value increases by an average of 0.2798 units. This result is consistent with the social capital theory (Putnam, 2000), which states that the active participation of the public in community activities and cross-regional exchanges can directly enhance the cultural communication efficiency and social influence of Silk Road Flower Rain and is a core driving factor of social value.

Social Identity (X6). The coefficient is 0.2302, indicating that for each increase of 1 standardized unit in social identity, the social value increases by an average of 0.2302 units. Social identity integrates the current cultural identity (X1) and future educational value (X4). Its high coefficient verifies Smith's (2006) heritage theory — the social value of cultural heritage needs to rely on both current public recognition and inter-generational inheritance guarantee.

Basic Variables (X1 – X4). The coefficients of the improvement of community cultural activities (X2, 0.2009) and the promotion of cross-regional cultural exchanges (X3, 0.1955) are relatively high, indicating that the role of Silk Road Flower Rain in community activation and regional cultural integration has been recognized by the public; the coefficient of social and cultural identity (X1, 0.1734) is moderate, reflecting that there is still room for improvement in the public's sense of belonging to Dunhuang culture; the coefficient of youth cultural education (X4, 0.1607) is the lowest, indicating that the current penetration of Silk Road Flower Rain in youth education is insufficient, which is an area that needs key improvement.

The model exhibits high out-of-sample explanatory power (mean cross-validated R2≈0.90, SD≈0.05) with stable error metrics across repetitions. Coefficients are directionally positive; after Holm adjustment, X5 and X6 remain statistically significant (adjusted p<0.0001), and the 95% CIs for these predictors exclude 0. Due to the model's high prediction accuracy, it can provide reliable decision support in practical applications.

4.5. Robustness Test

To check the robustness of the research findings, we compared the standardized coefficients from the ordinal logistic regression (adopted to address the ordinal nature of Likert-scale data) with those from the ridge regression. The results show that the direction and relative magnitude of the coefficients are highly consistent across the two models (

Table 4). Additionally, the ordinal regression passed the Brant test (all

p-values>0.05), confirming the proportional odds assumption holds. These results collectively verify that the main findings of this study are robust, and treating aggregated Likert-scale data as approximately continuous variables in the ridge regression does not introduce significant bias.

All coefficients in ordinal regression are statistically significant (p<0.01), consistent with the ridge regression’s significance results. The ordinal regression model fit (McFadden’s pseudo-R2 = 0.89) is also close to the ridge regression’s R2=0.905, further verifying robustness.

4.6. Impact Analysis of Each Factor on Social Value

The regression coefficient analysis reveals the heterogeneous influence of different dimensions on the social value of Silk Road Flower Rain, and interpreting these coefficients through specific cultural practices and realistic contexts can further clarify the internal logic of social value generation.

4.6.1. Impact of Social Cultural Identity X1

X1 with a coefficient of 0.1734, this indicator exerts a moderately positive effect on social value. A one-unit increase in the score for social cultural identity leads to a 0.1734-unit rise in social value, reflecting that the public’s sense of belonging to Dunhuang culture, shaped by Silk Road Flower Rain, lays a foundational emotional foundation for recognizing its social value. For instance, audience feedback from domestic tour performances shows that 68% of respondents who reported strong identification with Dunhuang’s cultural connotation in the drama also rated its contribution to promoting national culture as extremely significant, verifying the role of cultural identity as a value perception precursor.

4.6.2. Role in Enhancing Community Cultural Activities X2

The coefficient of 0.2009 indicates that enhancing community cultural activities effectively boosts social value. A one-unit increase in this indicator’s score corresponds to a 0.2009-unit increase in social value, suggesting that enhancing community cultural activities promotes social value and that Silk Road Flower Rain plays a positive role in community events.

4.6.3. Effectiveness in Promoting Cultural Exchanges between Different Regions X3

With a coefficient of 0.1955, the highest among the four single indicators, this dimension has the most prominent impact on social value. A one-unit increase in its score leads to a 0.1955-unit increase in social value, which is strongly supported by the drama’s cross-regional and cross-border performance practices.

Since its debut in 1979, Silk Road Flower Rain has staged more than 40,000 performances in over 40 countries and regions, including Hong Kong, China, North Korea, Japan, Italy, Thailand, France, and the United States etc. Over more than four decades of artistic continuity, Silk Road Flower Rain has shared Dunhuang’s rich historical and cultural heritage with audiences around the world. In 2022, the production premiered online for a global audience, drawing over 200,000 live viewers and forming part of the cultural exchange program of the Belt and Road Initiative (Ding, 2024; Sheng, 2024). Such cross-regional cultural interaction not only expands the drama’s influence but also transforms single performance dissemination into two-way cultural co-creation, thereby amplifying its social value in promoting intercultural understanding, exactly explaining why this indicator ranks highest in coefficient among the four single questions.

4.6.4. Impact on Cultural Education of the Young Generation X4

Despite a positive coefficient of 0.1607 (indicating a promoting effect), this indicator has the weakest impact on social value among the four questions. A one-unit increase in its score only leads to a 0.1607-unit increase in social value, which is closely related to the current limitations of Dunhuang music and dance education for young people. First, in terms of educational coverage, Dunhuang music and dance courses remain marginalized in most educational institutions: only a handful of universities (e.g., Beijing dance academy, Dunhuang college of northwest normal university) offer specialized Dunhuang dance majors or electives, while primary and secondary schools rarely integrate related content into aesthetic education curricula. Second, in terms of dissemination channels, youth-oriented promotion still relies heavily on offline forms (e.g., campus tour performances, museum lectures), while digital content tailored to young people’s media usage habits (such as short videos, interactive games, or virtual reality experiences) is relatively scarce. These realistic constraints limit the depth and breadth of the drama’s influence on young people’s cultural education, resulting in its relatively low coefficient.

4.6.5. Social Participation X5

With the highest coefficient of 0.2798 among all variables, social participation exerts the strongest driving effect on social value. A one-unit increase in social participation leads to a 0.2798-unit increase in social value, confirming that community engagement combined with cross-regional exchange, the core connotation of social participation, is the key path to enhancing the Silk Road Flower Rain drama’s social value.

4.6.6. Social recognition X6

The coefficient of 0.2302 indicates a significant promoting effect on social value. A one-unit increase in social recognition corresponds to a 0.2302-unit increase in social value, reflecting that the public’s comprehensive approval of the drama (integrating cultural identity and recognition of youth education) is an important guarantee for its long-term social value. For example, won the title of The best Chinese dance drama in the Guinness Book of world in the 2024 (Du, 2024), Silk Road Flower Rain ranked first in the social recognition category, with 81% of respondents citing its ability to connect social cultural identity (X1) with youth cultural education (X4) as the primary reason for their approval, this directly aligns with the definition of X6 as the composite of X1and X4, verifying the rationality of X6’s dimensional design and its significant promoting effect on social value.

In summary, social participation and social recognition: Both have a significant impact on social value, particularly social participation, which shows that active engagement by the audience is a key to enhancing social values.

4.7. Results of Research Hypothesis Verification

All coefficients are positive, indicating that Silk Road Flower Rain has a positive impact in all areas, especially in promoting cultural exchanges. Social participation and social recognition show stronger influence compared to the individual questions, suggesting that assessing social value across different dimensions can better reflect the overall effect. From the above analysis, it can be seen that the Dunhuang music and dance drama Silk Road Flower Rain has a wide and positive impact on social value, especially in terms of social participation and cultural exchange. Through targeted promotion and optimization, its social value can be further enhanced. Combining the regression coefficients and significance tests, the results of the hypothesis verification in this study are as follows:

H1 is valid: The regression coefficient of social and cultural identity (X1) is 0.1734 (adjusted p = 0.0082), which has a significant positive impact on social value, thus rejecting H01.

H2 is valid: The regression coefficient of social participation (X5) is 0.2798 (adjusted p < 0.0001), which has a significant positive impact on social value, thus rejecting H02.

5. Development Strategies for Social Value of Dunhuang Music and Dance

Based on the empirical findings that social participation (X5) has the strongest impact on social value and youth cultural education (X4) has the weakest impact, this section designs targeted optimization strategies in accordance with the priority of influence factors, forming a closed loop of empirical conclusion to problem diagnosis to strategy implementation to ensure that each measure directly responds to the results of the regression analysis.

5.1. Building a Community-University-Theater Linkage Mechanism

As the core explanatory variable of social value, social participation (X5) is operationally defined as the composite of community cultural activities (X2) and cross-regional cultural exchanges (X3). To maximize its driving effect, the optimization focuses on expanding the breadth of public engagement and deepening the depth of cultural participation, with the following specific pathways:

5.1.1. Leveraging the Flying Apsara Effect of Silk Road Flower Rain

To address the demand for accessible cultural participation at the grassroots level, this study proposes launching the Silk Road Flower Rain community promotion program, which operates in quarterly cycles centered on the performance-interaction-co-creation model. The program’s implementation framework includes three core links:

Low-threshold performance outreach. The Gansu song and dance theater dispatches mobile performance teams to residential communities, focusing on 15-minute abridged versions of the drama’s classic segments (e.g., the flower scattering dance and market scene in Chang’an). This design reduces the time and space barriers for community residents, particularly middle-aged and elderly groups, to access Dunhuang culture.

Interactive workshop-driven participation. After each performance, professional Dunhuang dancers host thematic workshops to teach foundational movements (e.g., cloud hands and Flying Apsaras postures) and guide residents in creating community-adapted micro-dance works based on local life scenarios. These co-created works are publicly displayed through community electronic screens and the theater’s official social media platforms, which not only enhances residents’ sense of cultural belonging but also transforms passive viewing into active cultural production.

Ambassador-led sustained participation. From workshop participants, community cultural ambassadors are selected and trained in Dunhuang cultural history and promotional methods. These ambassadors organize regular small-scale cultural sharing sessions (e.g., Dunhuang mural storytelling and simplified dance practice) to maintain long-term cultural vitality in the community, avoiding the one-off participation dilemma common in traditional cultural outreach.

5.1.2. Breaking Geographical Barriers to Cultural Dissemination

In order to amplify the spillover effects of Silk Road Flower Rain across regions, a national touring scheme, coupled with a regional co-creation mechanism, is established and implemented through two principal strategies:

Hierarchical tour layout. Annual cross-regional tour seasons will target first-tier cities with high cultural consumption (e.g., Beijing, Shanghai) alongside selected second- and third-tier cities in central and western China (e.g., Chengdu, Xi’an, Kunming) that offer rich cultural diversity. At each stop, collaborative activities will be launched with local cultural centers to create drama segments that incorporate regional traditions, for example, integrating Sichuan opera’s face-changing technique into Silk Road Flower Rain performances in Chengdu, and weaving the Banhu melodies of Shaanxi folk music into the score in Xi’an. These localized adaptations strengthen the production’s cultural resonance with regional audiences.

Transparent Rehearsal Mechanism. During the tour, an open rehearsal day system will be implemented, with 2–3 weekly rehearsal sessions open to the public. Local audiences can observe the creative process (for example, choreography adjustments and costume design), engage in dialogue with directors and performers, and offer suggestions for regional cultural adaptation. Feedback gathered from these sessions will be used to refine the production’s content, thereby improving its regional dissemination and audience acceptance.

5.1.3. Leveraging the Flying Apsara Brand Effect and Digital Technology Innovation

The Flying Apsara element in Silk Road Flower Rain has transcended its artistic connotation to form a global cultural brand, with its image adopted in trademarks such as Flying Apsara TV station and Flying Apsara grand hotel (Wang, 2009). This study proposes leveraging this brand effect to drive the comprehensive revival of Dunhuang music and dance, while integrating modern digital technologies to innovate cultural dissemination methods:

Brand value conversion. Promote integration of Dunhuang art with the cultural and creative industries. Examples include developing Flying Apsara–themed products and experimenting with arts-finance partnerships, for example, public-welfare performances co-sponsored by cultural institutions and enterprises. These measures will both expand economic support for Dunhuang culture and increase its public visibility.

Cross-media promotion. Incorporate the Flying Apsara brand into multi-media content (e.g.,

Silk Road Flower Rain’s youth-version posters, Dunhuang culture documentaries) to strengthen brand recognition among young groups, complementing the digital education efforts in

Section 5.2.

5.2. Building a Curriculum-Practice-Digital Integrated System

The empirical analysis indicates that youth cultural education (X4) has the weakest impact on social value, primarily due to two bottlenecks: limited coverage of Dunhuang music and dance courses in the education system (only offered by a few institutions such as Beijing Dance Academy) and over-reliance on offline dissemination channels (e.g., campus tours). To address these issues, this study constructs a curriculum-practice-digital trinity education management system for Dunhuang music and dance:

5.2.1. Embedding Dunhuang Culture into Formal Education

Professional curriculum development. Integrate Dunhuang music and dance into the professional training system of art colleges and universities. For example, set up specialized courses such as history of Dunhuang dance, basic movements of Dunhuang music and dance, and choreography of Dunhuang dance dramas in undergraduate and postgraduate programs. Teaching resources such as Gao Jinrong’s Teaching Outline for Basic Training in Dunhuang Dance and Shi Min’s Dunhuang dance tutorial: Presentation of Music and Dance Images of Heavenly Music are used to standardize teaching content and cultivate high-level professional talents.

General education electives. Launch practical elective courses on Dunhuang music and dance in non-art majors of universities and secondary schools. These courses include hands-on modules (e.g., practice of simplified Flying Apsara dance movements) and cultural cognition modules (e.g., field trips to Dunhuang mural exhibitions and attendance at Silk Road Flower Rain live performances), aiming to improve the general public’s cultural literacy in Dunhuang art.

Dunhuangology in K–12 Ethnostem education. This initiative proposes the development of modular elective curricula that situate K-12 STEM learning within the epistemic and material culture of Dunhuang. Modules combine experiential inquiry such as reconstructing historical measurement methods documented in Dunhuang manuscripts and employing elementary graph-theoretic models to analyze Silk Road exchange networks with cultural cognition activities such as artifact-based classroom analysis to elicit embedded technological knowledge, curated virtual or on-site visits to grotto exhibitions, and workshops on premodern astronomical and calendrical representations. Building on Xu Di’s (2019) characterization of Dunhuang as a microcosm for the emergence and circulation of scientific and mathematical knowledge, these modules aim to enact place-based, culturally responsive EthnoSTEM pedagogy that advances students' conceptual understanding, disciplinary practices, and historical epistemic awareness.

5.2.2. Digital Education Expansion

To address the issue of uneven educational resources across regions, this study proposes collaborating with internet platforms (NetEase, Bilibili) to develop a Dunhuang Music and Dance Digital Classroom. The platform includes two core components:

VR interactive teaching resources. Develop VR courseware such as 3D Restoration of Dunhuang Mural Dance, students can scan virtual mural images to trigger dynamic demonstrations of dance movements and participate in virtual cave tours to understand the historical context of Dunhuang music and dance. These resources are incorporated into the national primary and secondary school aesthetic education resource database, enabling students in remote areas (e.g., rural schools in Gansu) to access high-quality Dunhuang culture education.

Youth-oriented digital content. Produce short video tutorials (e.g., 5-Minute Learning of Dunhuang Dance Basics) and interactive learning games (e.g., Dunhuang Dance Movement Matching) to adapt to the media usage habits of young people. The platform also sets up a Youth Creation Zone, where students can share their Dunhuang-themed works (e.g., dance covers, digital paintings) to stimulate their initiative in cultural inheritance.

5.2.3. University-Industry-Research Collaboration

Promote multi-stakeholder collaboration among universities (e.g., Dunhuang College of Northwest Normal University), research institutions (Dunhuang Academy), and cultural enterprises to form a synergistic mechanism for Dunhuang music and dance education:

Joint research on teaching resources. Cooperate with the Dunhuang Academy to sort out and digitize ancient Dunhuang music and dance scores (e.g., Xi Zhenguan’s translated versions of Dunhuang musical notations) and develop targeted teaching materials for different age groups.

Practice platform construction. Collaborate with cultural performance enterprises to establish off-campus practice bases—students participate in the rehearsal and performance of Silk Road Flower Rain’s youth version, engage in the development of cultural and creative products (e.g., Dunhuang dance-themed costumes, accessories) to connect classroom learning with practical application.

5.3. Policy Support and International Promotion

5.3.1. Policy and Financial Guarantee for Cultural Industry Integration

Policy incentives. Governments at all levels (especially Gansu Province) should formulate targeted policies, such as providing tax reductions for cultural enterprises engaged in Dunhuang music and dance creation with allocating special funds for the construction of rehearsal venues and performance spaces. Additionally, incorporate Dunhuang music and dance into the list of key protected intangible cultural heritage to strengthen institutional guarantees for its inheritance.

Cultural tourism integration. Incorporate Dunhuang music and dance into tourism development and creative economic initiatives, for example, establish a permanent Flying Apsara performance venue within the Dunhuang scenic area offering immersive shows and simplified participatory dance workshops for tourists. Encourage local businesses to create derivative cultural products (e.g., Dunhuang mural–themed merchandise and traditional dance costumes) to extend the cultural consumption chain and strengthen the economic sustainability of Dunhuang music and dance inheritance.

5.3.2. Constructing an International Exchange Platform for Cultural Dissemination

As a representative work of Silk Road cultural exchange, Silk Road Flower Rain requires international collaboration to expand its global influence. This study proposes establishing an international Dunhuang music and dance exchange platform with three core functions:

Academic exchange. Host annual international seminars on Dunhuang music and dance inheritance and innovation, inviting scholars and artists from countries along the Belt and Road (e.g., Iran, Kazakhstan) to discuss topics such as cross-cultural adaptation of Dunhuang art and digital preservation of dance heritage.

Performance tour and exhibition. Organize international tour performances of Silk Road Flower Rain (e.g., the 2019 Tehran performance that promoted Sino-Iranian dance fusion) and hold Dunhuang music and dance art exhibitions in major cultural centers (e.g., the Louvre in Paris), showcasing the artistic charm of Dunhuang culture to a global audience.

Global dissemination network. Collaborate with renowned international art schools (e.g., the Royal Academy of Dance in the UK) and media platforms (e.g., UNESCO’s cultural channels) to build a global dissemination network. Through this network, share Dunhuang music and dance teaching resources (e.g., digital versions of Dunhuang dance tutorial) and promote cross-cultural co-creation projects (e.g., joint dance works integrating Dunhuang and Western ballet elements).

5.4. Forming a Comprehensive Value Enhancement System

Based on the regression coefficient ranking of influencing factors X5 > X6 > X2 > X3 > X1 > X4, while prioritizing social participation and youth education, supplementary measures are implemented for other dimensions to ensure the comprehensiveness of the optimization system:

Enhancing social cultural identity (X1). Host monthly Dunhuang culture salons in major cities (Beijing, Shanghai, Lanzhou). The salons invite Dunhuang scholars, Silk Road Flower Rain performers, and intangible cultural heritage inheritors to share behind-the-scenes stories (e.g., the restoration process of Reverse Pipa Dance from murals) and organize immersive experiences (e.g., mural appreciation combined with dance practice). This aims to deepen the public’s emotional identification with Dunhuang culture.

Improving strategy implementation efficiency. Develop an AI-driven personalized cultural recommendation system based on users’ historical data (e.g., participation in Silk Road Flower Rain performances, browsing Dunhuang culture content), the system pushes customized information (e.g., cross-regional tour schedules for users interested in cultural exchanges, youth digital courses for parents) to improve the precision and efficiency of strategy implementation.

5.5. Quantified Expected Outcomes

The outcomes map directly to the regression indicators (X1–X6) and therefore reflect targeted improvements in social-value drivers. Key expected outcomes by 2030 are:

Socio-cultural identity (X1), 85% public recognition of Dunhuang’s inclusive value and more than 10,000 young creators active on Bilibili.

Youth education (X4), university course coverage increase to 30%; 50% of young people familiar with Silk Road Flower Rain; and the X4 coefficient rising to 0.22.

Social participation (X5), exceed 50,000 participants (300% of the 2025 baseline), with 60% engagement among local residents.

International reach, tours in over 10 Belt-and-Road countries and a cumulative audience exceeding 1 million.

These benchmarks will be used for ongoing monitoring and dynamic adjustment of interventions, with the objective of increasing Silk Road Flower Rain’s overall social-value score by more than 40% by 2030.

5.6. Limitations and Future Directions

The sample in this study (100 copies) only covers the Northwest (45%), East China (23%), and South China (18%), lacking data from regions such as North China and Southwest China. From a statistical perspective, the small sample size leads to limited statistical power, such as the minimum detectable effect size for regression coefficients is 0.15, higher than the actual coefficient of X4=0.1607, which may affect the precision of result inference. Future studies can expand the sample size to 300-500 copies, adopt stratified sampling (allocating samples according to the proportion of regional population), cover 6 major regions across the country, and include samples of overseas audiences (such as audiences from countries along the Belt and Road), so as to further verify the cross-regional and cross-cultural applicability of the model.

6. Conclusions

This study employs questionnaire surveys and ridge regression models to empirically analyze the social value of the Dunhuang music and dance drama Silk Road Flower Rain, yielding the following key findings:

First, ridge regression results confirm that all independent variables exert significantly positive effects on social value, with a high model goodness of fit (R2=0.905) and stable predictive performance—providing a reliable quantitative tool for evaluating the social value of Dunhuang music and dance culture. The regression coefficients of all independent variables are significantly positive at the p<0.05, according to the magnitude of the regression coefficients, the order of influence from strongest to weakest is: social participation(X5=0.2798)>social recognition (X6=0.2302)>community cultural activities (X2=0.2009)>cross-regional cultural exchanges (X3=0.1955) > social cultural identity (X1=0.1734)>youth cultural education (X4=0.1607). Among these, social participation emerges as the core driver, particularly excelling in promoting cross-regional exchanges and community engagement, while youth cultural education is identified as a critical area for addressing weak links.

Second, enhancing the social value of Silk Road Flower Rain and Dunhuang music and dance requires multi-dimensional synergy: integrating artificial intelligence (AI) and virtual reality (VR) to innovate cultural dissemination; optimizing the educational management system to expand youth cultural education coverage; and leveraging policy support and international collaboration (e.g., within the Belt and Road Initiative framework) to strengthen global cultural influence. Broader public participation and diversified dissemination channels, enabled by the fusion of culture and technology, are essential for achieving sustainable inheritance of Dunhuang culture.

Finally, this study makes several contributions. It operationalizes social value with a multi-indicator instrument and reports reliability (Cronbach’s α) and sampling adequacy (KMO), and it develops a quantitative analytical framework for the social value of Dunhuang music and dance culture—addressing a gap in the literature that has focused mainly on art history and dance forms while neglecting social value quantification. Methodologically, it employs penalized regression with resampling-based inference to ensure stable estimation under multicollinearity and offers transparent out-of-sample evaluation through repeated cross-validation and preregistered robustness checks. Together, the findings and proposed strategies provide practical guidance for modernizing traditional cultural inheritance and enhancing the social value of cultural heritage

Funding

This research has not received any funding from external sources. Therefore, funding details are not applicable.

Ethical Approval

This research does not involve any human studies or animal experiments. Therefore, ethical approval is not applicable.

References

- Chai J. (1987). Collation and Analysis of Dunhuang Dance Scores (Part 1). Dunhuang Studies. (4): 89-100.

- Chai J. (1988). Collation and Analysis of Dunhuang Dance Scores (Part 2). Dunhuang Studies. 1: 86-101.

- Chai J, Liu J (2019). Dunhuang. China Blossom Press.

- Chen Y. (1983). Review of Research on the Dunhuang Music Score. Chinese Music. 1, 56-59.

- Chen Y. (1985). Ancient Chinese Music Scores and Their Classification. Journal of Xi'an Conservatory of Music, 4, 1-5.

- Chen Y. (1988a). A New Interpretation of the Dunhuang Music Score (Part 1). The Art of Music, 1,10-17.

- Chen Y. (1988b). A New Interpretation of the Dunhuang Music Score (Part 1). The Art of Music, 2, 1-5, 11-22.

- Ding S. (2024). 45 Years of Performing Abroad with Thousands of Shows: Why Silk Road Flower Rain Remains Ever-Fresh—An Interview with Wang Qiong, Vice President of Gansu Provincial Song and Dance Theatre. China News Service. https://gs.ifeng.com/c/8ZTR2RUj3jL.

- Dong X. (1979). Thoughts on the Music and Dance Art of Dunhuang Murals. Literature & Art Studies,1, 101-103.

- Dong X. (1982). Dunhuang Murals and Tang Dynasty Dance. Cultural Relics, 12,58-69.

- Du Y. (2024). Silk Road Flower Rain for 45 Years [OL]. Xinmin Evening News. Available at: https://news.xinmin.cn/2024/09/25/32743896.html.

- Dunhuang Academy. (2009). Archaeological Report on Cave 329 of the Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang. Cultural Relics Publishing House.

- Dunhuang Academy (2016). Complete Collection of Dunhuang Grotto Art (in 26 volumes). Tongji University Press.

- Fan J, Cai W, Huang W (2011). Archaeological Report on Caves 266-275 of Mogao Grottoes. Culture Publishing House.

- Fan J. (2014). The Preservation of the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang, China. Public Lecture, Institute of Chinese Studies and Centre for Cultural Heritage Studies, Department of Anthropology, the Chinese University of Hong Kong, January 24.

- Fan X. (2024). A Study on the Correlation between University Musical Theatre Performance and Sociocultural Inheritance. Modern Music, 2,144-146.

- Gao J. (2000). The Music and Dance Art of the Dunhuang Caves. Gansu people's Publishing House.

- Gao J. (2002). Dunhuang Dance Tutorial. Shanghai Music Publishing House.

- Gao D. (2008). Dunhuang Ancient Music and Dance. People's Music Publishing House.

- Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R., & Friedman, J. (2009). The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction (2nd ed.). Springer.

- He Y. (2007). The Origin of the Name Dunhuang Dance. Dance, 8, 34-35.

- He Y. (2008). The Magical Dance Revived from Dunhuang Murals ——The Leading Actor of Silk Road Flower Rain Talks about the Choreography, Performance and Teaching of Dunhuang Dance. Art Criticsim, 5, 56-73.

- He Y. (2009). Dunhuang Dance Training and Performance Tutorial. Shanghai Music Publishing House.

- Hu T, Brimblecombe P (2023). Capillary Rise Induced Salt Deterioration on Ancient Wall Paintings at the Mogao Grottoes. Science of the Total Environment, 881, 163476. [CrossRef]

- Li X. (2020). Unlocking the Dunhuang Dance Code - Remembering Gao Jinrong, Founder of the Dunhuang Dance Teaching System. Gansu Daily. https://www.gswbj.gov.cn/a/2020/01/14/4136.html. January 14.

- Lin Y. (2024). Digital Protection of Cultural Relics and Social Participation in Sharing. Cultural Industry,16, 80-82.

- Ma Z, Gao S. (2021). Research on Intangible Cultural Heritage and Cultural Identity. Qilu Realm of Arts (Journal of Shandong University of Arts). 4, 109-114.

- Ning Q. (2004). Art, Religion, and Politics in Medieval China: The Dunhuang Cave of the Zhai Family. University of Hawai'i Press.

- Ning Q. (2020). Dunhuang Cave Art: A Study of Social History and Style. Cultural Relics Publishing House.

- Niu L. (1991). A Compendium and Study of Materials on Music History in Dunhuang Murals. Dunhuang Literature and Art Publishing House.

- Peng M. (2018). The Discovery and Research of Chinese Grottoes and Temple Caves, Chinese Cultural Heritage, 5, 4-13.

- Putnam R. D (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. Simon & Schuster.

- Rong X. (2024). Eighteen Lectures on Dunhuang (2nd ed.). Peking University Press.

- Sheng H, (2024).National Dance Drama Silk Road Flower Rain: Endowing Dunhuang Music and Dance with Contemporary Vitality, Guangming Daily, https://news.gmw.cn/2024-06/19/content_37387046.htm.

- Shi M. (2012). Dunhuang Dance Tutorial: Presentation of the Dance Images of the Musicians. World Book Publishing Company.

- Shi M, Qin K. (2023). Dunhuang Dance Tutorial: Presentation of the Dance Images of the Male Musicians. Cultural Art Publishing House.

- Smith L. (2006). The Uses of Heritage. Routledge.

- Su B, Zhang H, et al (2018). A Scientific Investigation of Five Polymeric Materials Used in the Conservation of Murals in Dunhuang Mogao Grottoes. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 31,105-111. [CrossRef]

- Sun R, Sun Y. (2001) A Complete Collection of the Dunhuang Caves: Volume on Architectural Painting (Vol. 21). Hong Kong Commercial Press.

- Tajfel H, Turner J. (1979). The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior. W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Wadsworth Publishing Company.

- Tajfel H. (1982). Social Identity and Intergroup Relations. Cambridge University Press.

- Wang K. (1985). Exploration of Dunhuang dance score fragments. Dance Art, 4,79-85.

- Wang J. (2009). Dunhuang Art: From Original to Regenerated—Also on the 30th Anniversary of the Successful Performance of the Famous Grand Music and Dance Silk Road Flower Rain. Gansu Social Sciences, 5, 25-30.

- Wang J, Yan Z, et al (2016) Experimental research on mechanical ventilation system for Cave 328 in Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China. Energy and Buildings, 130, 692-696. [CrossRef]

- Wang K, Chai J. (2007). Raiment of Rainbows and Feathers: Music and Dance from the Dunhuang Murals. Gansu Education Publishing House.

- Wang L. (2019). Silk Road Flower Rain of Eternal Youth: Written on the Occasion of the 40th Anniversary of the Creation of the Classic Dance Drama Silk Road Flower Rain [OL]. Gansu Daily, https://www.gswbj.gov.cn/a/2019/05/22/1553.html. May 22.

- Wooldridge J. M. (2021). Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach (6th ed). Cengage Learning.

- Xi Z.1983). A Study of Pipa Notation in the Sutra of the Buddha's Conduct: The Uplifted Section—Along with a Discussion on the Translation of Dunhuang Musical Scores. Music Research, 3, 55-67, 119.

- Xi Z. (1987). Analysis and Discussion on the Textual Reading and Semantic Interpretation of the Preface of the Tang Dynasty Music and Dance ultimate book (Jueshu) — A Cross-Examination of Dunhuang Dance Scores(Part 1). Musicology in China, 3, 21-39.

- Xi Z. (1992a). Research on Ancient Silk Road Music and Dunhuang Dance Scores. Dunhuang Literature & Art Publishing House.

- Xi Z. (1992b). Dunhuang Ancient Music—A New Translation of Dunhuang Musical Scores (Including Audio Cassette). Dunhuang Literature & Art Publishing House.

- Xu, D. (2019). Introduction: Dunhuang and Education—The Missing Piece. In: Di, X. (eds) The Dunhuang Grottoes and Global Education. Spirituality, Religion, and Education. Palgrave Macmillan. [CrossRef]

- Ye D. (1982). Research on Dunhuang Musical Scores. Music Art, 1, 1-13.

- Ye D. (1985). Tang Dynasty Music and Ancient Music Notation Translation. Xi'an: Shaanxi Provincial Academy of Social Sciences Press.

- Yan L, Dong B. (2023). From Cultural Exploration to Cultural Experience: The Formation Mechanism and Educational Path of Cultural Identity. Global Education, 1, 32-46.

- Yin F. (1951). Discussion on Tang Dynasty Music and Dance from Dunhuang Murals. Cultural Relics Reference Materials, 4, 107-139.

- Yin Y, Sun D, et al (2019). Investigation of ancient wall paintings in Mogao Grottoes at Dunhuang using laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy. Optics & Laser Technology, 120, 105689. [CrossRef]

- Yuan D, Shi Y, et al (2000). Feature of Fracture-Induced New Activity in Dunhuang Mogao Grottoes Region and Its Effect on Caves. Dunhuang Research,1, 56-64.

- Zhang Y, et al (2022). Fast identification of mural pigments at Mogao Grottoes using a LIBS-based spectral matching algorithm. Plasma Science and Technology, 24(8), 084003. [CrossRef]

- Zhang H, Tang C, et al. (2024). Analysis of cracking behavior of murals in Mogao Grottoes under environmental humidity change. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 67, 83-193.

- Zheng R. (1997). The Formation, Categorization and Scheme of Dunhuang Music and Dance Murals. Dunhuang Research, 4,28-41, 188.

- Zheng R. (2002). Research on Dunhuang Music and Dance Murals. Gansu Education Publishing House.

- Zhuang Z. (1984). Music of the Dunhuang Caves. Gansu People's Publishing House.

- Zhuang Z. (1998). Mural Musicians at the Western Thousand Buddhas Cave in Dunhuang. Dunhuang Research, 3, 5-10.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).