Submitted:

28 October 2025

Posted:

28 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines

2.2. Establishment of Stable Transfectants

2.3. Development of Hybridomas

2.4. Flow Cytometry

2.5. Determination of Dissociation Constant Values Using Flow Cytometry

2.6. Western Blotting

2.7. Immunohistochemistry Using Cell Blocks

2.8. Immunohistochemistry Using Tissue Arrays

3. Results

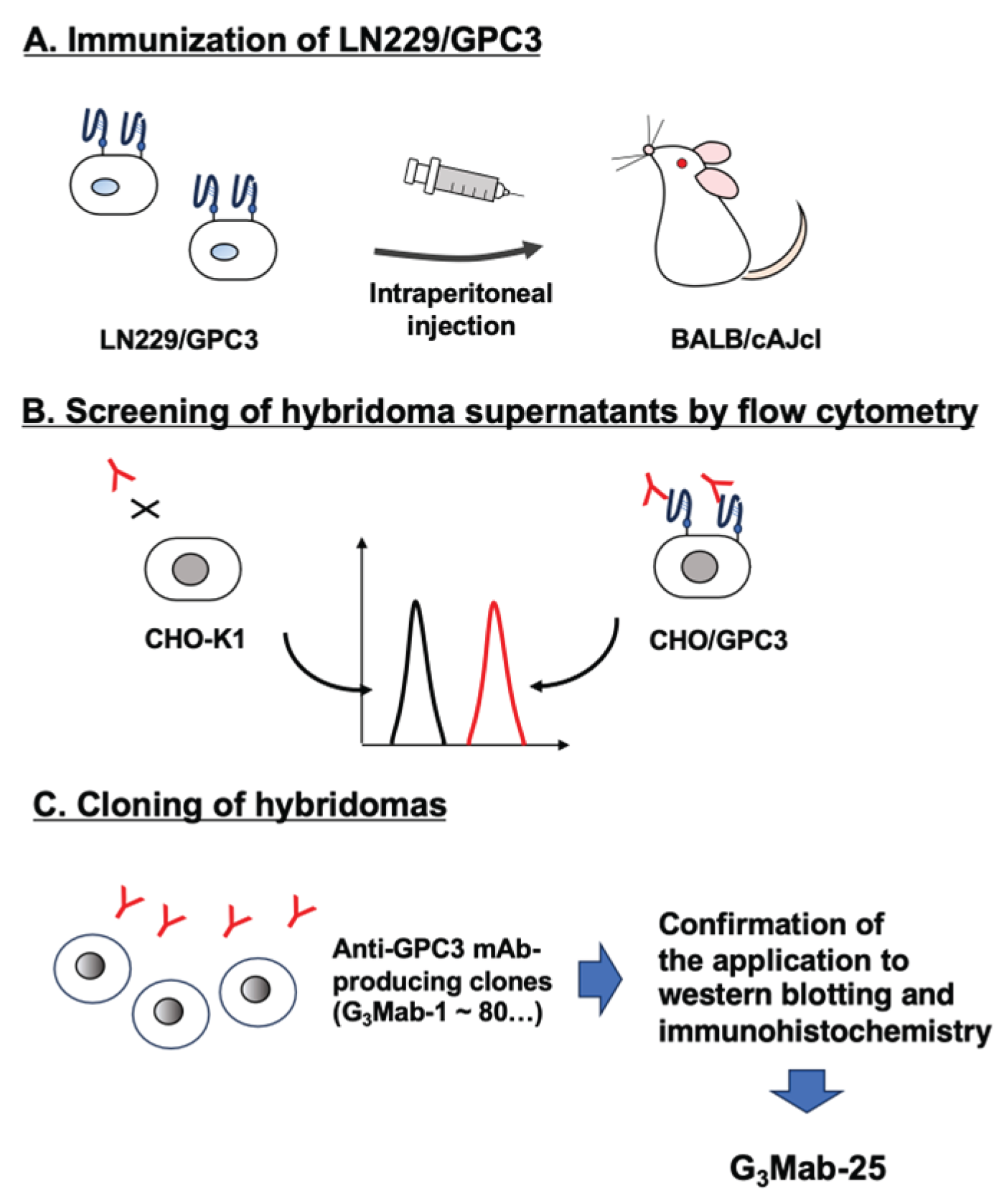

3.1. Development of Anti-GPC3 mAbs

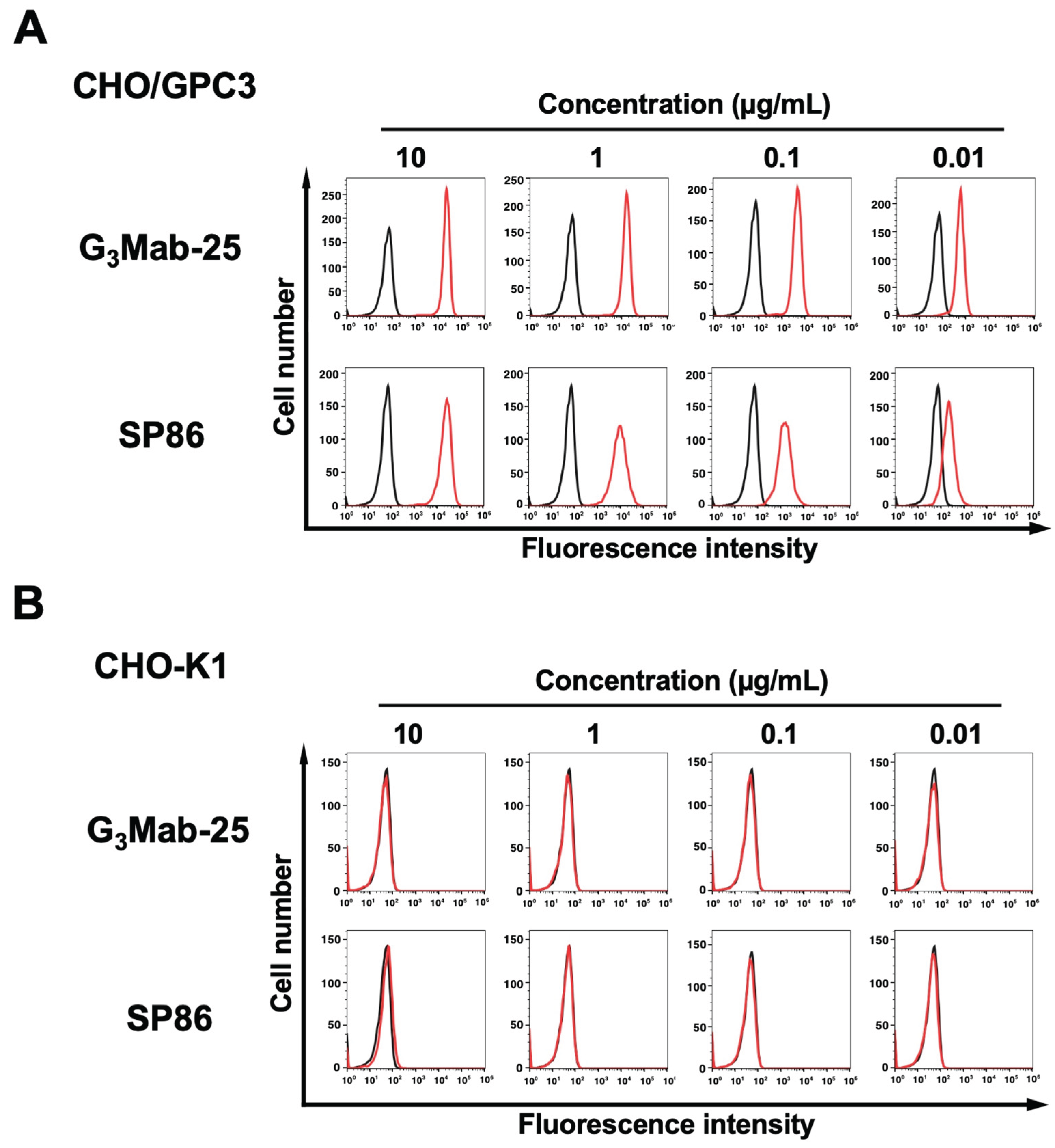

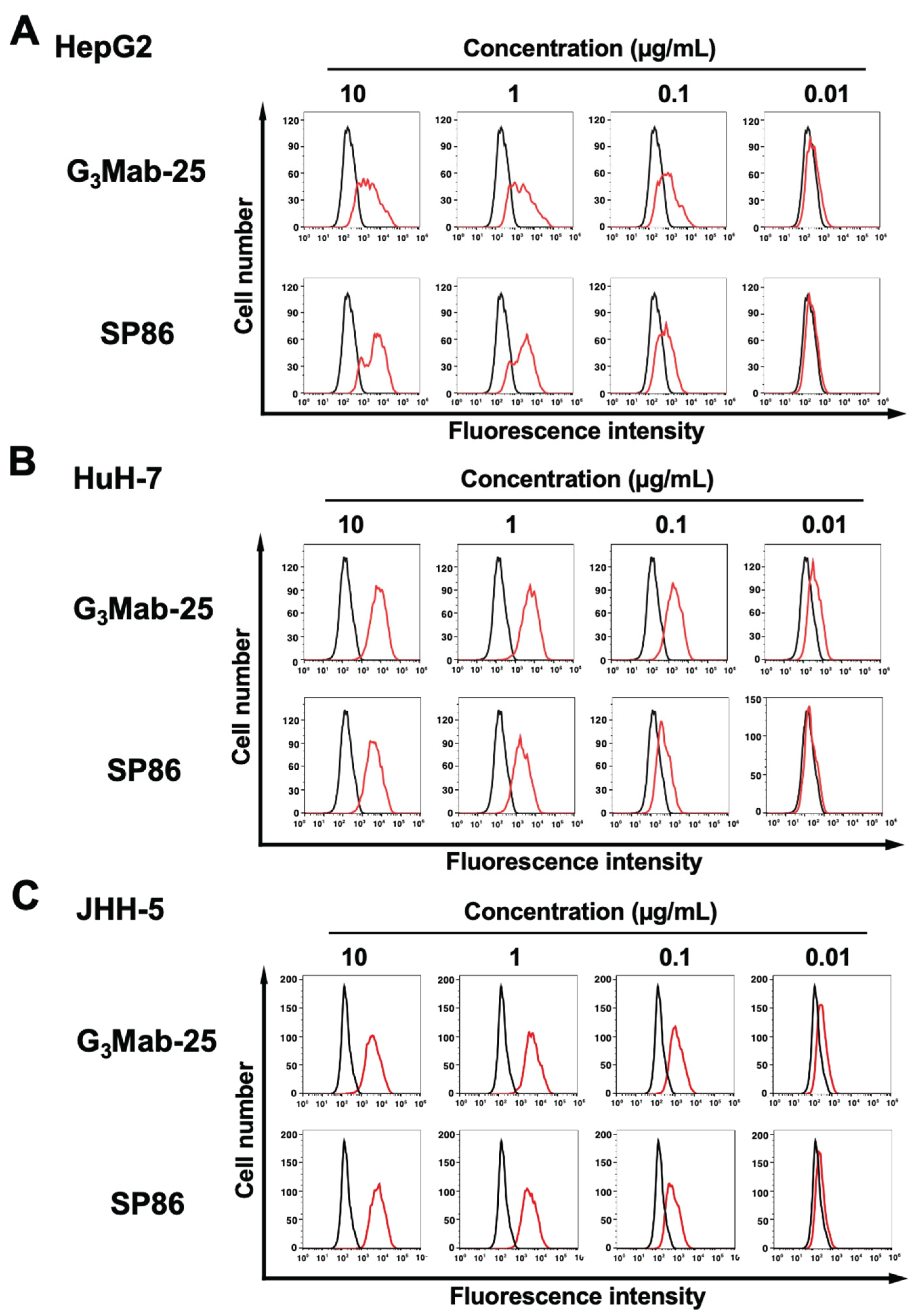

3.2. Flow Cytometry Using Anti-GPC3 mAbs

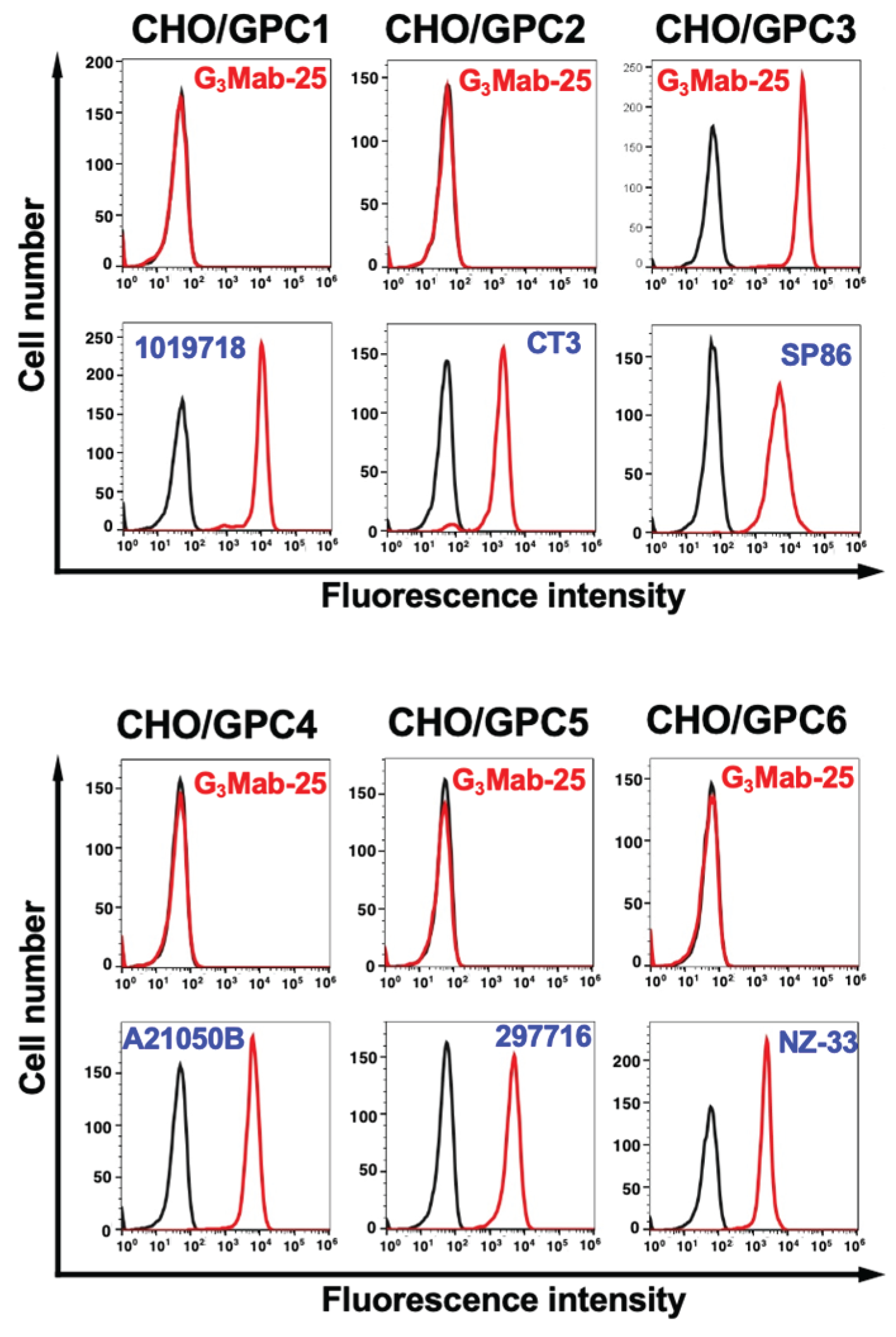

3.3. Specificity of G3Mab-25 Against GPC Family Members

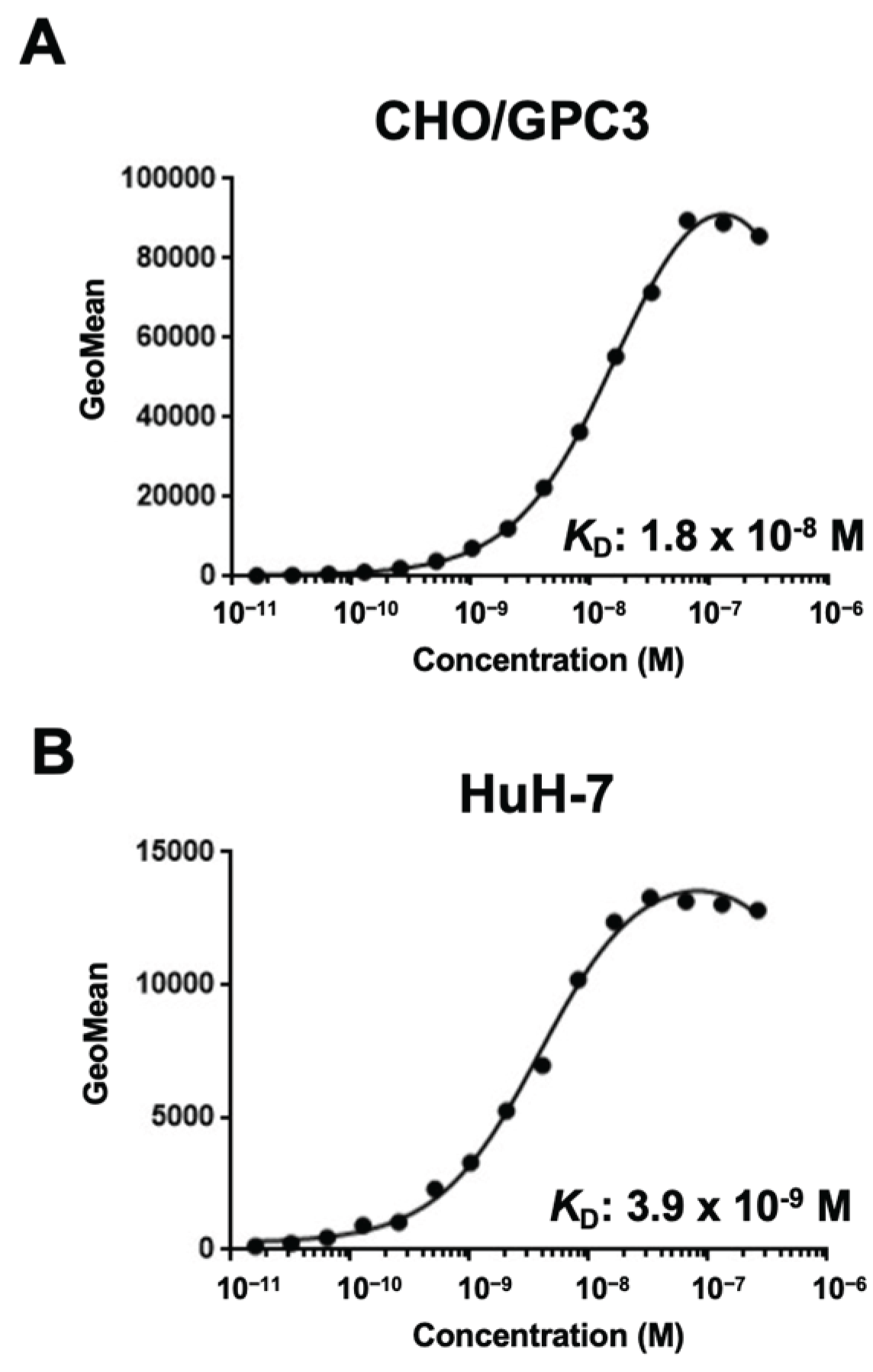

3.4. Determination of KD Values of G3Mab-25 by Flow Cytometry

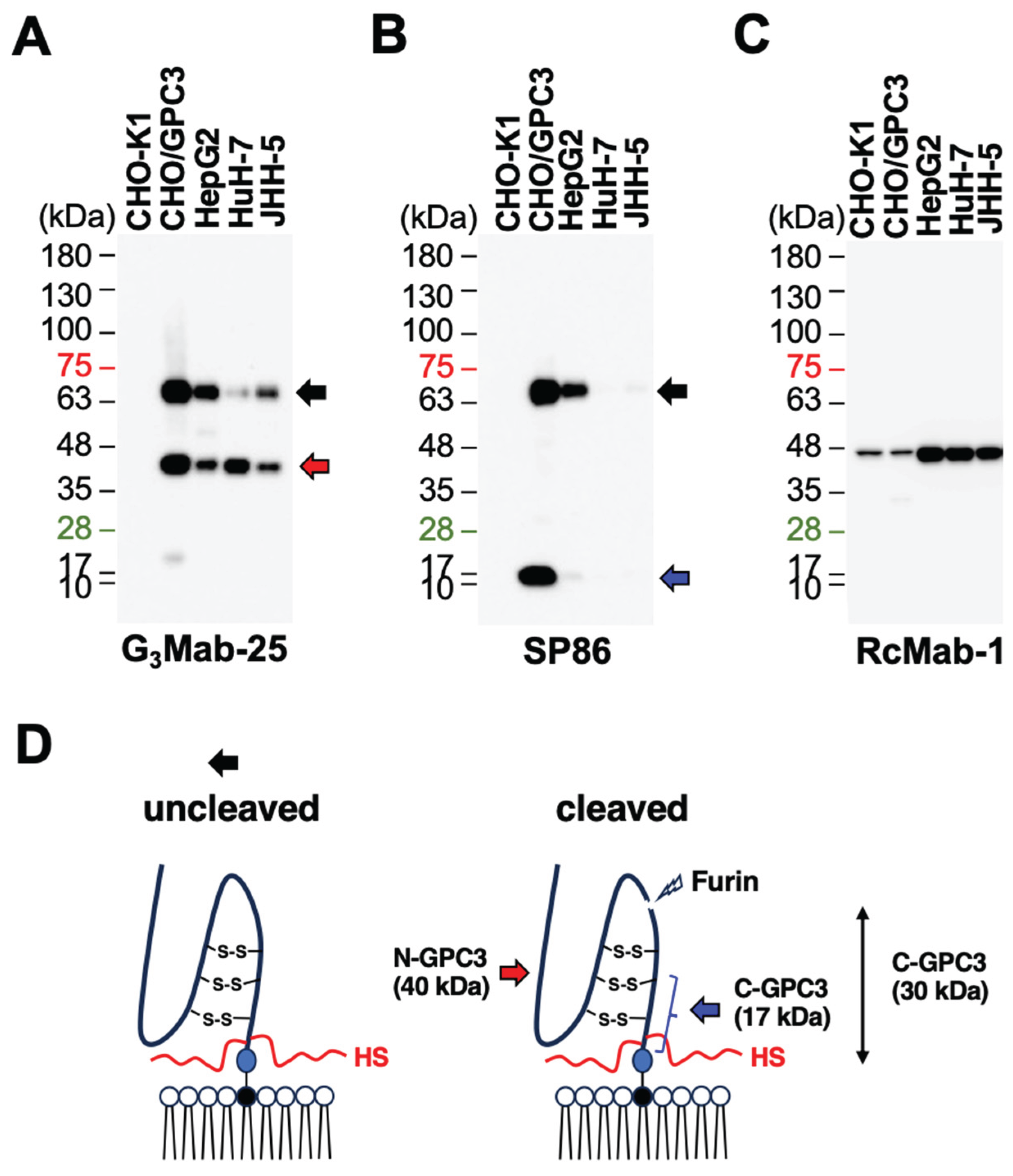

3.5. Western Blotting Using Anti-GPC3 mAbs

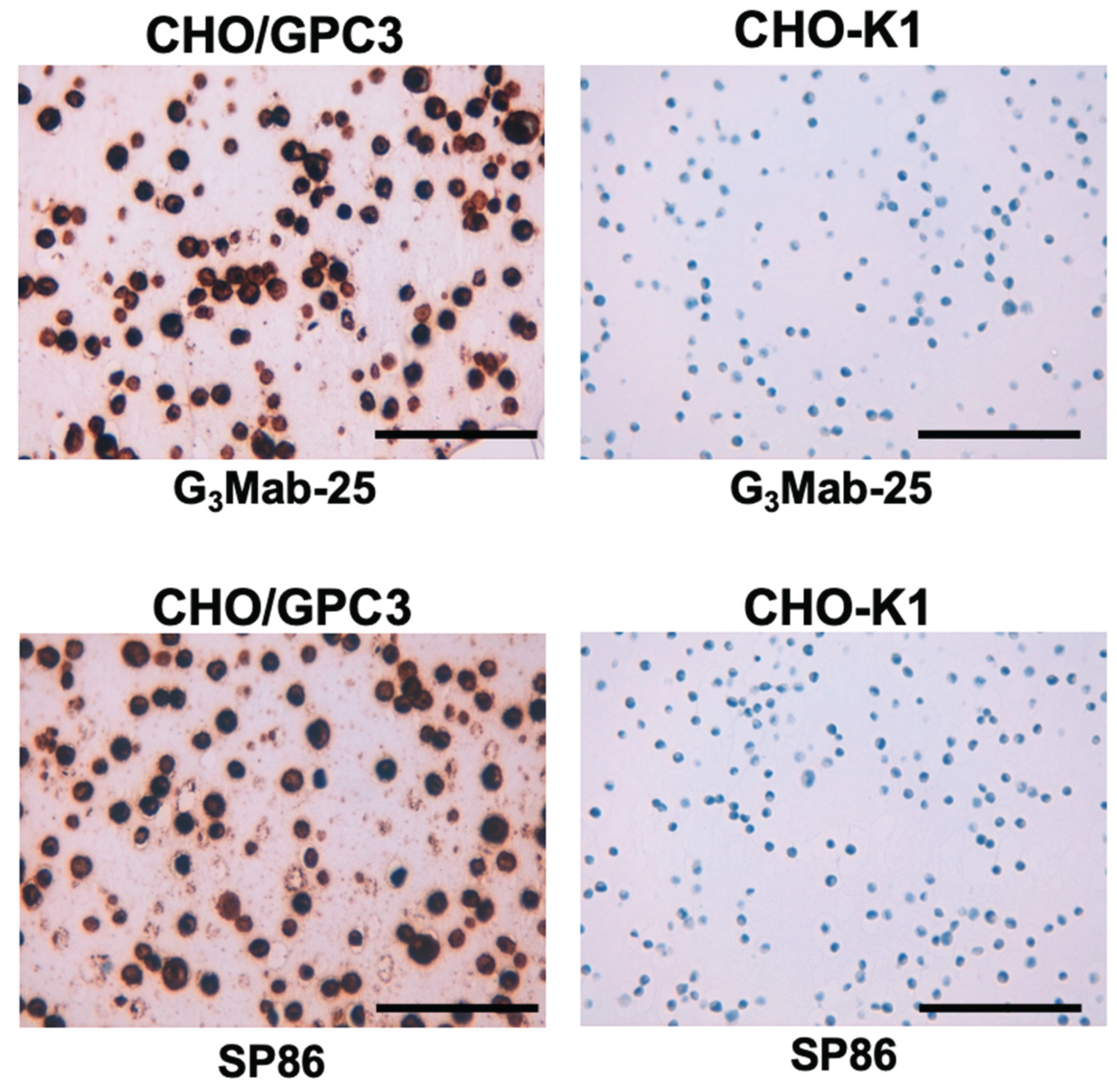

3.6. Immunohistochemistry Using Cell Blocks

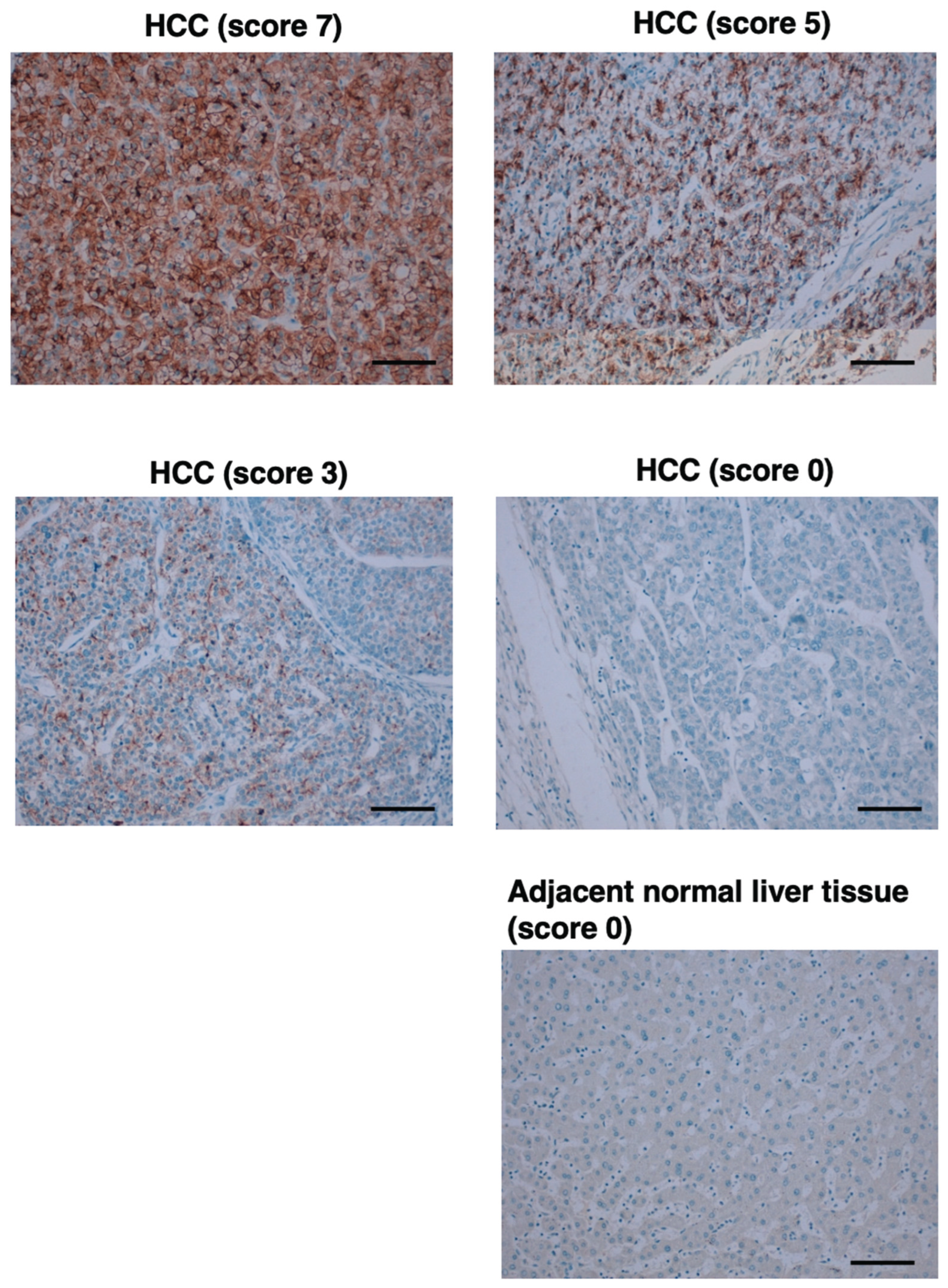

3.7. Immunohistochemistry Using Cell Blocks

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Credit: authorship contribution statement

Funding Information

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fico, A.; Maina, F.; Dono, R. Fine-tuning of cell signaling by glypicans. Cell Mol Life Sci 2011, 68, 923–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filmus, J.; Capurro, M. The role of glypicans in Hedgehog signaling. Matrix Biol 2014, 35, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolluri, A.; Ho, M. The Role of Glypican-3 in Regulating Wnt, YAP, and Hedgehog in Liver Cancer. Front Oncol 2019, 9, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cat, B.; Muyldermans, S.Y.; Coomans, C.; et al. Processing by proprotein convertases is required for glypican-3 modulation of cell survival, Wnt signaling, and gastrulation movements. J Cell Biol 2003, 163, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, Q.; Bian, X.; Zhao, Q.; Sun, L. Unraveling Glypican-3: From Structural to Pathophysiological Roles and Mechanisms-An Integrative Perspective. Cells 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.H.; Filmus, J. The role of glypicans in mammalian development. Biochim Biophys Acta 2002, 1573, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Yamada, H.; Yamaguchi, Y. K-glypican: a novel GPI-anchored heparan sulfate proteoglycan that is highly expressed in developing brain and kidney. J Cell Biol 1995, 130, 1207–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumhoer, D.; Tornillo, L.; Stadlmann, S.; et al. Glypican 3 expression in human nonneoplastic, preneoplastic, and neoplastic tissues: a tissue microarray analysis of 4,387 tissue samples. Am J Clin Pathol 2008, 129, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, H.H.; Shi, W.; Xiang, Y.Y.; Filmus, J. The loss of glypican-3 induces alterations in Wnt signaling. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, 2116–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capurro, M.I.; Xu, P.; Shi, W.; et al. Glypican-3 inhibits Hedgehog signaling during development by competing with patched for Hedgehog binding. Dev Cell 2008, 14, 700–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lum, L.; Yao, S.; Mozer, B.; et al. Identification of Hedgehog pathway components by RNAi in Drosophila cultured cells. Science 2003, 299, 2039–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topczewski, J.; Sepich, D.S.; Myers, D.C.; et al. The zebrafish glypican knypek controls cell polarity during gastrulation movements of convergent extension. Dev Cell 2001, 1, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrimon, N.; Bernfield, M. Specificities of heparan sulphate proteoglycans in developmental processes. Nature 2000, 404, 725–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baeg, G.H.; Perrimon, N. Functional binding of secreted molecules to heparan sulfate proteoglycans in Drosophila. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2000, 12, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhave, V.S.; Mars, W.; Donthamsetty, S.; et al. Regulation of liver growth by glypican 3, CD81, hedgehog, and Hhex. Am J Pathol 2013, 183, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, B.; Syn, W.K.; Delgado, I.; et al. Hedgehog signaling is critical for normal liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in mice. Hepatology 2010, 51, 1712–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepers, E.J.; Glaser, K.; Zwolshen, H.M.; Hartman, S.J.; Bondoc, A.J. Structural and Functional Impact of Posttranslational Modification of Glypican-3 on Liver Carcinogenesis. Cancer Res 2023, 83, 1933–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hippo, Y.; Watanabe, K.; Watanabe, A.; et al. Identification of soluble NH2-terminal fragment of glypican-3 as a serological marker for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 2004, 64, 2418–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakatsura, T.; Yoshitake, Y.; Senju, S.; et al. Glypican-3, overexpressed specifically in human hepatocellular carcinoma, is a novel tumor marker. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2003, 306, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capurro, M.; Wanless, I.R.; Sherman, M.; et al. Glypican-3: a novel serum and histochemical marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2003, 125, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Ma, Y.; Chen, Y.; et al. Diagnostic and prognostic performance of serum GPC3 and PIVKA-II in AFP-negative hepatocellular carcinoma and establishment of nomogram prediction models. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devan, A.R.; Nair, B.; Pradeep, G.K.; et al. The role of glypican-3 in hepatocellular carcinoma: Insights into diagnosis and therapeutic potential. Eur J Med Res 2024, 29, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, K.; Orita, T.; Nezu, J.; et al. Anti-glypican 3 antibodies cause ADCC against human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2009, 378, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Ho, M. Glypican-3 antibodies: a new therapeutic target for liver cancer. FEBS Lett 2014, 588, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiguro, T.; Sugimoto, M.; Kinoshita, Y.; et al. Anti-glypican 3 antibody as a potential antitumor agent for human liver cancer. Cancer Res 2008, 68, 9832–9838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abou-Alfa, G.K.; Puig, O.; Daniele, B.; et al. Randomized phase II placebo controlled study of codrituzumab in previously treated patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2016, 65, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, A.X.; Gold, P.J.; El-Khoueiry, A.B.; et al. First-in-man phase I study of GC33, a novel recombinant humanized antibody against glypican-3, in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2013, 19, 920–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, N.; Hosono, A.; Yoshikawa, T.; et al. Phase I study of glypican-3-derived peptide vaccine therapy for patients with refractory pediatric solid tumors. Oncoimmunology 2017, 7, e1377872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, R.; Tan, X.; Wang, C. Targeting Glypican-3 for Liver Cancer Therapy: Clinical Applications and Detection Methods. J Clin Transl Hepatol 2025, 13, 665–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippi, L.; Frantellizzi, V.; Urso, L.; De Vincentis, G.; Urbano, N. Targeting Glypican-3 in Liver Cancer: Groundbreaking Preclinical and Clinical Insights. Biomedicines 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasquillo, J.A.; O'Donoghue, J.A.; Beylergil, V.; et al. I-124 codrituzumab imaging and biodistribution in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. EJNMMI Res 2018, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, M.M.; Gutsche, N.T.; King, A.P.; et al. Glypican-3-Targeted Alpha Particle Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Molecules 2020, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wei, S.; Xu, M.; et al. CAR-T cell therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: current trends and challenges. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1489649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, C.; Zhang, P.; Shen, L.; Qi, C. Optimizing CAR T cell therapy for solid tumours: a clinical perspective. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, C.S.M.; Dardalhon, V.; Devaud, C.; et al. CAR T-cell therapy of solid tumors. Immunol Cell Biol 2017, 95, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffin, D.; Ghatwai, N.; Montalbano, A.; et al. Interleukin-15-armoured GPC3 CAR T cells for patients with solid cancers. Nature 2025, 637, 940–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ubukata, R.; Ohishi, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Suzuki, H.; Kato, Y. EphB2-Targeting Monoclonal Antibodies Exerted Antitumor Activities in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer and Lung Mesothelioma Xenograft Models. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satofuka, H.; Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; et al. Development of an anti-human EphA2 monoclonal antibody EaMab-7 for multiple applications. Biochem Biophys Rep 2025, 42, 101998. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; Li, G.; et al. Development of a Sensitive Anti-Mouse CCR5 Monoclonal Antibody for Flow Cytometry. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2024, 43, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanamiya, R.; Takei, J.; Asano, T.; et al. Development of Anti-Human CC Chemokine Receptor 9 Monoclonal Antibodies for Flow Cytometry. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2021, 40, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y.; Kaneko, M.; Neyazaki, M.; et al. PA tag: a versatile protein tagging system using a super high affinity antibody against a dodecapeptide derived from human podoplanin. Protein Expr Purif 2014, 95, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikota, H.; Nobusawa, S.; Arai, H.; et al. Evaluation of IDH1 status in diffusely infiltrating gliomas by immunohistochemistry using anti-mutant and wild type IDH1 antibodies. Brain Tumor Pathol 2015, 32, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehrich, B.M.; Monga, S.P. WNT-β-catenin signalling in hepatocellular carcinoma: from bench to clinical trials. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.; Xu, Y.; Liu, J.; Ho, M. Epitope mapping by a Wnt-blocking antibody: evidence of the Wnt binding domain in heparan sulfate. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 26245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Wei, L.; Liu, X.; et al. A Frizzled-Like Cysteine-Rich Domain in Glypican-3 Mediates Wnt Binding and Regulates Hepatocellular Carcinoma Tumor Growth in Mice. Hepatology 2019, 70, 1231–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, N.; Watanabe, A.; Hishinuma, M.; et al. The glypican 3 oncofetal protein is a promising diagnostic marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Mod Pathol 2005, 18, 1591–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, C.J.; Bates, K.M.; Rimm, D.L. HER2 testing: evolution and update for a companion diagnostic assay. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2025, 22, 408–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, F.; Paluch-Shimon, S.; Senkus, E.; et al. 5th ESO-ESMO international consensus guidelines for advanced breast cancer (ABC 5). Ann Oncol 2020, 31, 1623–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Huang, L.; Huang, J.; Li, J. An Update of Immunohistochemistry in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Diagnostics (Basel) 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.H.; Wang, Y.N.; Xia, W.; et al. Removal of N-Linked Glycosylation Enhances PD-L1 Detection and Predicts Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 Therapeutic Efficacy. Cancer Cell 2019, 36, 168–178.e164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Ho, P.; Staudt, S.; et al. Fine tuning towards the next generation of engineered T cells. Nat Biomed Eng 2025, 9, 1610–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Valid, O.; Shouval, R. Predictors of response to CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in large B-cell lymphoma: a consolidated review. Curr Opin Oncol 2025, 37, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).