3.1. 3D Modeling

Commonly used AM technologies require use of a computer, a 3D modeling software, machine equipment and the layering material. The object first needs to be digitally modeled, as a CAD file, before it is translated into a code understandable by the machine. [

20] Using computer to reduce three-dimensional volume to a series of 2D layers is a fundamental principle of 3D printing. [

22] 3D modeling and preparation of computer model is important element of 3D printing technology. 3D modeling in the case of 3DP is different from conventional 3D modeling for games, renders, animations for which commonly available software is used. When designing a 3D model boundary surface of the model must be watertight, with all faces connected with consisted orientation of surface normal. [

32] Design of full-scale 3D printable prototype of Nematox façade node required 120 hours of CAD 3D modeling including 10 hours of converting the 3D model geometry data into the appropriate AM file format. [

26] The delicacy of the printing process requires careful design and export of the object geometry from the 3D software such as Blender, Rhinoceros3D + Grasshopper, etc. Most of the time when transferring the 3D model between different software, extra steps need to be undertaken in order to clean the model and readjust the parameters.

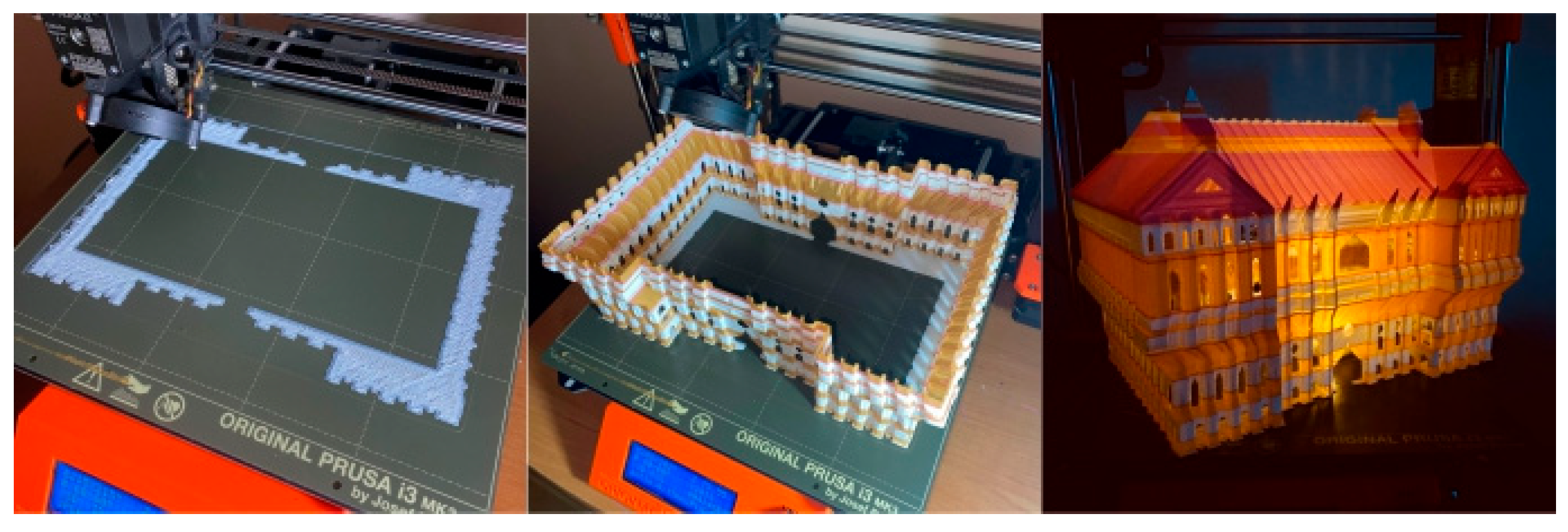

Figure 7 shows the 3D model drawn in Blender and in its 3D printed form. The process of transferring the 3D model to the machine requires translation of 3D model geometry into a machine code, usually done in specially designed software which slices the model into layers of linear toolpaths.

Conventional, 3D digital modeling by drawing of geometry is also being transformed by the use of different optimization and AI software. Variety of digital tools offer architects and designer possibility to reduce the consumption of material, printing times, increase structural properties by letting software calculate specific dimensions, adjust or generate shapes according to predetermined computer algorithms. The use of these tools is becoming rapidly significant since they offer a unique opportunity to empirically optimize and generate designs which can fit structural, functional and other requirements and constraints. [

16,

21,

29] Topology optimization is a methodology which removes the materials from places in the model where there are no forces while only keeping geometry which plays structural role in transition of load forces. Topology of the object can also be optimized according to printer properties such as speed and acceleration. [

15] Optimization can be done manually by dimensioning and shaping the object according calculation of structural forces and using intuition or it can be done computationally based on preprogramed form generation and finding software. Design methodology, 3D modeling, machine features, as stages of 3D printing are interconnected and changes in one of the stages directly influences the performance in other stages of the process. Therefore, for a successful integration of 3D printing technology, a designer, architect, engineer should master the whole process from idea until printable object in order to use the 3D printing technology in an optimized and sustainable way.

Design and 3D modeling should be done in accordance of 3D printing process and its limitations taking into consideration printer speed, nozzle dimensions, layer thickness, material behavior and the extrusion capacity of the printer. [

20] Different materials require different representations in digital space of 3D modeling software and suitable design and representation tools must be developed which will enable maximal control over the inputs, the process and the outputs. Voxel-based modeling seems to be useful in the design of 3D printable foam forms. [

35] Different materials, fabrication methods, designs may be suitable for some of the software and not suitable for other ones, while there are many cases where teams of expert develop their own tools that match the needs of the project.

Small scale 3D printable models provide possibility to practice, learn and eventually utilize the 3D modeling skills which are in the same manner required in large-scale 3D printing. On the level of 3D modeling and printing it is also possible to explore different options that can then be further applied on bigger scales. Required continuity of the 3D printing process from start to end requires that there is no single error in terms of geometry because fragility of the fabrication process. Even if the most of the printing process is successful, a minor mistake in terms of geometry means that the printing process need to start from beginning which in the case of large-scale printing would be quite a setback. In this sense small-scale 3D printing and modeling methods are crucial before prototypes are further developed and scaled.

3D printing is being continuously explored in different ways because it became globally accessible and available to a rapidly growing community. There are growing online platforms for trade, exchange and download of 3D printable models. Even though the plastic material is most commonly used for small scale 3D printable models there is a significant number of examples of functional, useable, non-fragile 3D objects printed in plastics. Structural properties of plastics can also be increased (or decreased) with the overall form of the object but also with parameters such as thickness of the wall. The geometry of the object itself as well as the material properties both influence the overall structural capacities of a 3D printed object. In combination with computational tools it is possible to print structurally stable and strong objects such as helmets, machine parts and other objects which require structural durability. Materials used for small scale 3D printing can be further researched and developed.

Figure 9 shows bird houses printed in PLA plastic left outdoors to observe the performance of printed plastics throughout the years of weather conditions changes.

Another geometrical challenge is design of object with interlocking parts which can’t be separated from each other and this topic is an inspiration for numerous creative solutions and products such as chains or flexible platforms. On the other hand, design of objects which can be assembled and dissembled is a design challenge which can also be computationally solved in a way to define pieces which will retain structural strength when combined together [

36]. Such challenges require higher skills in understanding the geometry and CAD in order to successfully manage different constraints in terms of dimensions and production process.

3.2. 3D Printing Without Supports

Optimization of building form within the constraints of the 3D printer and the materials is a large field with lot of potential for exploration and development. Designing printable objects without infills, offsets or supports with continuous spiral paths, using an extruder attached to a robotic arm while the object remains static is presented in [

14]. Infills, offsets, supports are additional parts of the printed object and serve to provide stability and enable printing of bridges, cantilevers and complex geometrical shapes. Supports and offsets are usually removed from the object after the printing is done, while infill constitutes the interior structure of the printed object and it is an important topic for many aspects of the quality of printed object.

FDM based printers can print shapes with or without having the supports. When printing objects which require supports, printer parallelly prints both the object and the supports from the first layer so that the supports can hold the critical overhangs of the object until the print is done and object becomes a whole. At the end of the process the printed support is easily removed from the printed object.

Figure 6 shows the miniature of a bar chair printed with supports and after the removal of support part. On the other hand, SLA and SLS printer technologies can only print the object with the supporting material – each layer is firstly completely covered with powder-based material and then the section which belongs to the object is cured whilst the part which is supposed to be support remains in powder state. This technology always involves removal of the powder which acts as support after the object is printed and becomes a whole.

The limitation of inability to print flat, horizontal surfaces without supports is expressed in three common approaches to constructing roofs of 3D printed housing prototypes. One way is to construct a wooden or steel frames above 3D printed walls and then install roof panels – in the same way it is done in traditional construction. Second approach includes placement of prefabricated concrete slabs and then print or install parapets. Third one includes manual placement of the formwork and binding of rebars of the roof then casting or spraying of the concrete on them. [

6] Even though these approaches seem most feasible now, explorations within the domain of design of printable structures which do not require supports or additional manual labor can be very important in further development of automation in construction. Reliability, cost reduction, reduction of need for expert workforce and other advantages of 3D printing are significantly reduced if the automation is strongly intertwined with the manual labor. Exploration of practical and applicable geometry of small-scale models within the constraints of 3D printing presents a huge field for further exploration which can highly benefit the process of printing of larger structures.

In this sense FDM printers provide the possibility to design architectural forms which do not require supports but still can answer to the requirements of their purpose. Design and print of architectural shapes which do not require supports significantly reduce the amount of consumed material and time it takes for print to finish.

Figure 7 shows examples of forms which do not require supports in order to be 3D printed. For example, instead of printing a flat roof which immediately requires supports – the dome like shaped house would be more optimal and would not require any supports to be printed. Supports are important (similar to scaffoldings) because they increase the material consumption, time for printing, additional resources and labor, and building forms which do not require supports seems to be more optimal solutions for the 3D printing of buildings on massive scale. Small scale 3D printing technology provides possibilities to explore and experiment with forms which can be then implemented on a larger scale while avoiding unnecessary costs and waste. 3D printing in construction is considered as technology which removes need for formwork and scaffoldings therefore print of designs which require print of support may be paradoxical. That is why research in design, shape and form finding of 3D printable designs may be a very important development for the progress of the 3D printing industry as a whole.

3.3. 3D Printers as Research Tools in Construction

Different categorizations of 3D printing systems can be done according to available literature but based on the criteria of scale of 3D printing systems there are large-scale systems and small-scale systems. [

12] Next to making the division based on the size of the machine 3D printing technology it is also possible to divide the possible application of small scale and large-scale 3D printable models. In this paper the small-scale 3D printing is considered as a regular 3D printing concept while large-scale 3D printing is emphasized because of significant differences in dimensions, materials, machines, software, etc.

The tool path of the machine which describes the geometry of the object and the consequent points of material disposure is extremely important topic and small-scale 3D printing can be used for research in this field. The tool path determines the feasibility, cost, machining time, aesthetics and structural properties of a 3D printed object [

14]. In this sense the toolpath both determines the micro-structural features such as the interior structure of the wall and the wall profile but also the macro-structural features of the object as a whole. The relationship between the shapes of the building elements and the building as a whole – in the context of continuous 3D printing – is rarely researched or presented. In the large-scale 3D printing, most of the buildings have orthogonal shapes, many of them rounded corners, several use curved walls, few of them spherical. [

13]. The same 3D CAD model can produce different results based on AM technology, machine parameters, orientation of the model within the machine boundaries, parameters of translation from geometry to machine code. Assembly, production, geometric freedom needs to be considered for taking full advantage of AM technology which require highly skilled and computer literate engineers. [

26]

There is a qualitative difference between the print of large-scale and small-scale 3D models represented through tool paths (lines of motion of 3D printer head as it moves and extrudes the material from the attached nozzle). Large-scale paths spread more and their interruption becomes more challenging as the material deposition rates increase and it has been shown that printing large structures require as few interruptions as possible and with smoother changes in path orientations [

14] With scaling also comes the problem of object remaining static during the print process because printing of small-scale models is usually done on a predefined flat platform. Large-scale printing would require possibility to print on terrain surfaces that are not flat and there are already researches which are addressing this issue. [

34] With the increase in scale, material properties become increasingly more important while small-scale 3D printed models do not need to have the structural properties of a full-scale structure. [

12]

For now, small-scale 3D printed models have a narrow field of application in AEC industry. Very common use of 3D printers is to print miniatures of building designs for exploration or representation purposes. [

11,

22,

28] Important feature of printing small scale objects is that it is commonly available but there are significant structural challenges for its use in full-scale buildings [

12]. Even so, 3d printer can be used to print small scale models to study the geometric aspects of the design paths and in one of the cases small scale prototypes with heights ranging from 10 to 40 cm are printed. [

14]

There are many common points shared between the large- and small-scale 3D printing. The core concepts of the technology are the same and, in this context, small scale 3D printing systems can be used to conceptually explore large scale 3D printing systems before building them in their actual size. Small scale 3D printers can serve as a miniatures of large-scale 3D printing systems to explore different configurations and relations between the machine movements, the overall geometry of the building, logistical challenges and other scalable issues that can be observed on a small scale and implemented on a large-scale system.

Due to similarities between the machine concepts (extruder motion, extrusion, layering) small-scale 3D printing represents an important tool in developing concepts for 3D printing of large structures. Even though it is hard to simulate the very properties of materials such as concrete, steel or cob, plastics provide close enough quality for small-scale printing to produce similar errors and fails due to gravity, machine parameters, and geometrical features of the printed object. Essentially, most fails which would happen if the concrete or cob was used, would happen with plastic material. In this sense the domain of the machine design and the design geometry can be extensively explored with small 3D printers. [

12] In one of the examples of exploration of real-size 3D printable parabolic concrete column small-scale models of concrete molds were printed. Besides the general development of 3D printing process, experimentation with small-scale printed models provided practical experiences with handling and hardening of the material, pouring of the concrete and removal of the formwork. [

11]

Printing fails are specific research subject and studies differ based on different materials, equipment and building being printed. Some of the failures such as global instability of the object concerns mainly the geometry of the object, whilst plastic collapse and elastic buckling are linked to material properties. [

16] In an example of printing 3D shapes made of hollow cells, three different fail modes are reported: cell collapse, partial cell collapse, and the too dense error -each corresponding to different parameters that are identified to participate in guiding towards the collapse. In the research forms such as Diamond and Gyroid are reported to be less prone to the problem of collapse due to the specific geometrical properties. [

3] Print speed, filament extrusion rate, nozzle dimensions, printing path (related to 3D model and translation of 3D data into a tool path), filament height and print height are parameters responsible for the quality of final printed product. Small-scale printable models can play significant role in overseeing the potential fails arousing from geometrical properties when printing large, real size components.

Small-scale printable models are extremely useful in cases where series of prototypes is being made to fine tune different parameters on the level of machine, material and design in order to achieve seamless printing process from the start till the end. Small scale 3D printing has potential to significantly reduce cost of development and operation of large-scale 3D printers. On a smaller scale it is possible to test and experiment with different parameter settings with much lower costs but with output that can be used to improve the large-scale 3D printing process. If it can’t be printed on a small scale – it can’t be printed on a large scale too.

3D printing technology at the same time imposes limitations and constraints but open many new possibilities for construction of architectural forms. Creativity is also required to come up with new ways to use the given technology to fabricate buildings. Due to effects of gravity, elements such as flat lintels or floors cannot be printed without supports or without arched tops. To overcome this issue it is proposed to print lintels and floor beams with the first layers of printing process and then place them when the printing process arrives at the specific height for their placement. Such concept could involve human labor to place the pre-printed (as of pre-fabricated) elements or eventually a robotic arm could be pre-programed and integrated with the printer to place the elements accordingly. [

17]

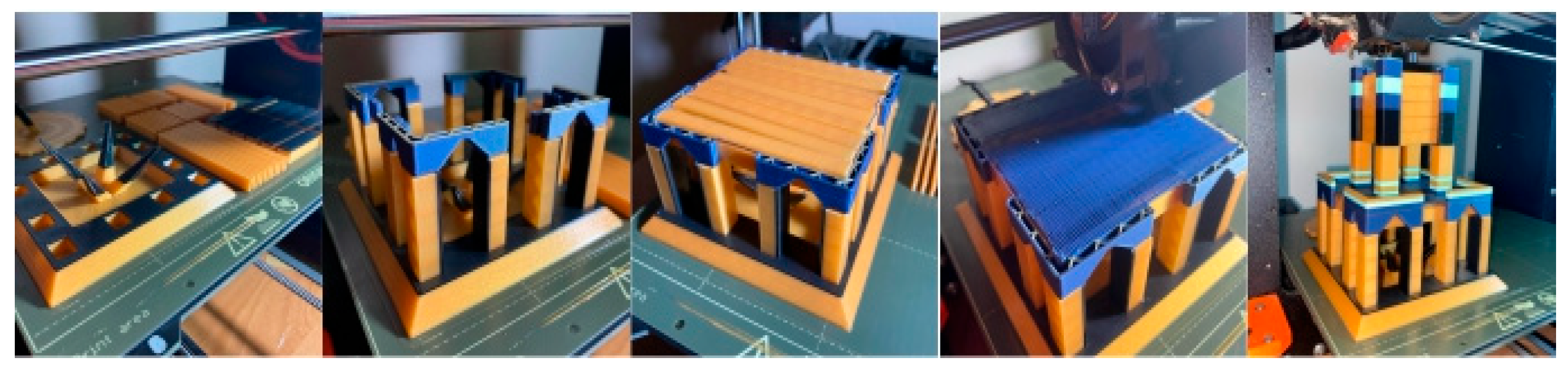

In the same manner the author of the paper had designed and printed small-scale experiments where the columns, beams, slab supports, roof coverings are printed together with the base of the building. The printing process was prepared to stop at specific layer heights to allow for the placement of the elements. Even if it is a small scale print such a process requires very delicate design, planning and machine operation together with the placements of the building elements during the print. (See

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.) Presented examples have a purpose to visualize the complexity of the challenge present in printing of flat slabs, beams and lintels but also to emphasize the importance of using small scale 3D printers to perform tests and go through the process on a small scale before using or constructing large scale 3D printers. Use of large-scale 3D printing equipment needs to be justified in terms of costs and performing small scale tests can help to optimize the process in terms of possible fails due to geometry, symmetry issues or machine operation parameters.

Experimenting and testing the process of 3D printable buildings on small scale can help to prevent failures on larger scale but also can serve to invent new approaches to 3D printing in AEC. Before significant investment in the research of large-scale 3D printing it would be more beneficial to use the possibilities given by small scale 3D printing to come up with more optimal solutions before actually applying them on the construction site. 3D printing of buildings is a complex process and optimization is possible on many levels and throughout all the phases, especially while the development of 3D printing technology for construction is still in its infancy and there is space for exploration and experimentation with different methods. In such a context, small scale 3D printers are essential tools to explore the possibilities of construction given with the technologies of 4th Industrial Revolution.

One of the problems of 3D concrete 3D printing is poor surface finishes. [

8,

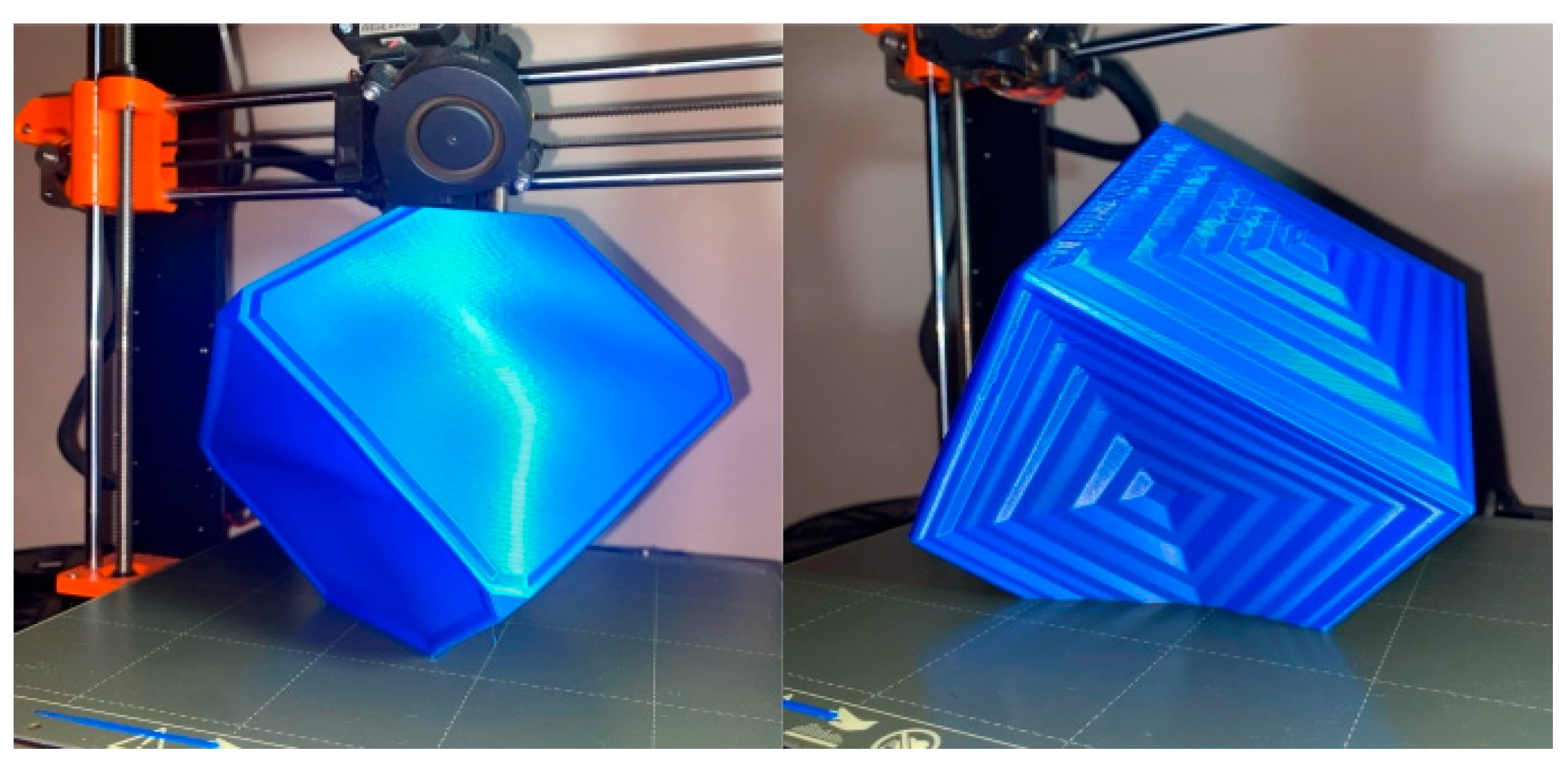

27] Using small printable models it is possible to examine different micro geometries of the toolpaths in order to both increase the aesthetic and structural values of printed object. With the use of small-scale 3D printing, it is possible to experiment with structural capabilities of printed forms and in this case, the scale is not much of a limitation as loads and material properties can be also scaled to be proportional with the dimensions of the object. Special textures, geometrical shapes can be explored that are able to provide sufficient strength with least consumption of the material. (See

Figure 4 and

Figure 5.) Design and modeling of a 3D object intentioned for printing is very important for the whole process of 3D printing since a bad model can cause fails, machine issues, and in essence compromise the whole fabrication process. 3D model which is not adequately design and prepared for printing can never give satisfactory results regardless of the material or machine features. On the other hand, design and 3D modeling can extensively optimize the whole process by reducing waste, machine work-time, protection of printing equipment.

Figure 2.

Architectural prototype miniature 3D modelled in Blender, prepared for printing in Prusa slicer software and 3D printed. Design and print by the author of the paper.

Figure 2.

Architectural prototype miniature 3D modelled in Blender, prepared for printing in Prusa slicer software and 3D printed. Design and print by the author of the paper.

Figure 3.

Visible erosion of birdhouses printed in PLA plastic after spending 3 years outside. Designed and printed by the author of the paper.

Figure 3.

Visible erosion of birdhouses printed in PLA plastic after spending 3 years outside. Designed and printed by the author of the paper.

Figure 4.

Chair miniature printed in a specific position which requires supports that are removed after the printing is finished. Designed and printed by the author of the paper.

Figure 4.

Chair miniature printed in a specific position which requires supports that are removed after the printing is finished. Designed and printed by the author of the paper.

Figure 5.

3D printable shapes which do not require supports. Designed and printed by the author of the paper.

Figure 5.

3D printable shapes which do not require supports. Designed and printed by the author of the paper.

Figure 6.

Printing process showing the printing of building elements in the first layers which are then placed to serve as support for the flat floor slab to be printed on top. In the same manner stairs, roof coverings and wall infill are also printed and mounted. Designed and printed by the author of the paper.

Figure 6.

Printing process showing the printing of building elements in the first layers which are then placed to serve as support for the flat floor slab to be printed on top. In the same manner stairs, roof coverings and wall infill are also printed and mounted. Designed and printed by the author of the paper.

Figure 7.

In this example the columns were also printed and placed in the consequent places at the bottom of the base and then the beams connecting them were printed on top. Slab supports, wall infills were also printed and mounted while printing process was consequently paused and resumed. Designed and printed by the author of the paper.

Figure 7.

In this example the columns were also printed and placed in the consequent places at the bottom of the base and then the beams connecting them were printed on top. Slab supports, wall infills were also printed and mounted while printing process was consequently paused and resumed. Designed and printed by the author of the paper.

Figure 8.

Three-dimensional structure of the wall enables stability of the object during the print. Hollow structure creates architectural space without the need for supports or scaffoldings. Roof is printed by adjusting the slope so the layers can be dispositioned in a way to close the gap. Openings are designed to have different shapes of arches so that they can be eventually bridged with corbelling of consecutive layers. Designed and printed by the author of the paper.

Figure 8.

Three-dimensional structure of the wall enables stability of the object during the print. Hollow structure creates architectural space without the need for supports or scaffoldings. Roof is printed by adjusting the slope so the layers can be dispositioned in a way to close the gap. Openings are designed to have different shapes of arches so that they can be eventually bridged with corbelling of consecutive layers. Designed and printed by the author of the paper.

Figure 9.

Printing of a flat surfaces of the cube may be quite a challenging task because the cube does not have structural capabilities as a whole while it is being printed. Adding texture to the surfaces of the cube increases the stability of the shape before it reaches maximum strength after the printing process is done. Designed and printed by the author of the paper.

Figure 9.

Printing of a flat surfaces of the cube may be quite a challenging task because the cube does not have structural capabilities as a whole while it is being printed. Adding texture to the surfaces of the cube increases the stability of the shape before it reaches maximum strength after the printing process is done. Designed and printed by the author of the paper.

3.4. Production of Real-Size Construction Components

Small-scale 3D printable models can be used as parts that are then assembled into larger structures or they can be used as components together with conventional building materials. This format of planning for design of 3D printable structure has a lot of advantages in terms of reusability, recyclability, modularity, versatility, adaptability, and sustainability and in this way 3DP can be used for printing of larger structures. [

31]

FDM (Fused Deposition Modeling) 3D printing technology is used by general public, hobbyists, SMEs to produce parts or whole products, individual designers, but it can also be used in architecture and construction to create façade panels, bespoke floors, molds for concrete casting, full scale pavilions. [

14] It can be used to print smaller things such as benches, entrances and art features - both in scale and scaled. [

37]

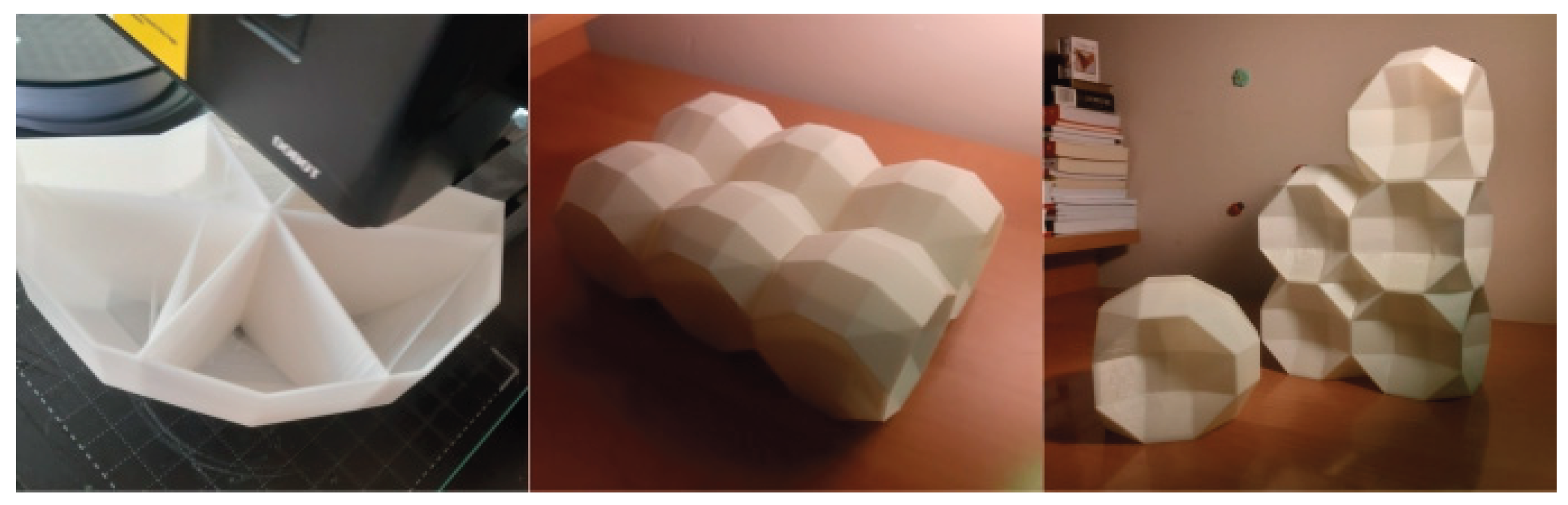

Small scale 3D printing technology has also proven as a great method for fabrication of different building elements prototypes or finished products. Project SPONG3D represents a full-scale façade element printable using FDM technology with PETG plastics [

38] On another level there are experiments with 3D printable bricks which can be used in construction. 3D printing of clay bricks involves research focused on the properties of the clay as printable material and the overall brick geometry and structural capabilities of a single brick and when connected with other bricks in a wall surface. Depending on the function of the building elements bricks can be printed for nonstructural walls and divisions, as a component for sunshades and cladding and non-structural brick vaults. Within the field of 3D printing of bricks with clay materials, geometry of the brick – its internal structure, pattern design – is another huge field for possible explorations on the level of design and computational shape optimization and generation. [

3] Nematox façade node is another yet 3D printable product where additive manufacturing is leveraged to produce intricate designs of façade nodes which require series of performance demands. Conventionally designed lighting node comprised from up to seven unique machined plates welded to a central tube was redesigned by Arup to take advantage of additive manufacturing technology. [

26] Although these examples are printed in metal, similar possibilities exist within the domain of FDM plastic based 3D printer. In this context there are examples of 3D printable joints which are then use to combine existing wooden or metal beams and sticks.

As an experimentation in the same field, the author of the paper designed a concept of 3D printable tool that could be used in conventional construction industry, at the construction site. (

Figure 10.) Even though 3D printing technology creates new paths for the construction industry, small-scale 3D printable models could be used to assist and optimize existing construction methods.

On the other hand, small-scale 3D printing can be used to print real-size animal shelters, bird houses (

Figure 11) but also decorative and construction elements for interior design (

Figure 12). Endless possibilities of design and 3D printing allows for high customization and also provides excellent way to replace broken parts.

Many architects are already utilizing 3D printing technology in interior design to produce objects which exactly match the specific needs of the interior space. 3D printing allows architects to execute literally any interior design idea. Instead of relying on what is available on the market, the architect has opportunity to design and produce almost any interior architectural component. [

20]