Submitted:

27 October 2025

Posted:

28 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

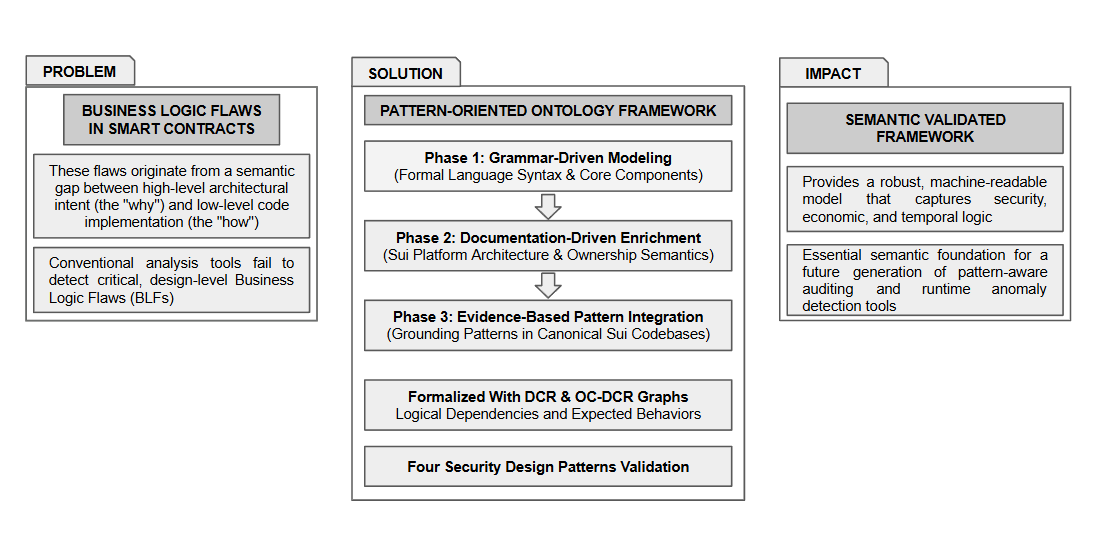

1. Introduction

- A formal ontology for the Sui Move language that systematically models its key components, including packages, modules, structs, functions, and access control mechanisms.

- A curated collection of secure design patterns, including Access Control, Circuit Breaker, Time Incentivization, and Escapability, formally defined as classes within the ontology.

- The mapping of each design pattern to a corresponding OC-DCR graph, which captures its expected dynamic behavior and logical dependencies in an executable format.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Blockchain Networks

- Account-based model: Ethereum and similar networks use this type of model, where balances are directly stored and updated with each transaction. The concept of accounts is used in the Ethereum network, in which the externally owned accounts (EOAs) are controlled by private keys, and the contract accounts, which are controlled by their associated code.

- Object-based model: In this model, everything on-chain is represented as an object carrying properties, ownership rights, and transfer capabilities. These objects are stored inside the Sui ledger, recognized by their globally unique identifier they carry.

2.2. Smart Contracts

2.3. The Sui Blockchain and Sui Move Language

2.4. Design Patterns in Account-Based vs. Object-Centric Models

2.5. The Rise of Business Logic Flaws

2.6. Ontologies for Formalizing Smart Contracts

2.7. Declarative Process Modeling

3. Constructing the Ontological Framework

3.1. Structural Foundation via Grammar-Driven Modeling

- Knowledge Source: We began building our ontology base with a systematic analysis of the official Sui Move formal grammar, which provides the ground truth for the language’s structure.

- Process: The syntactic rules and non-terminals from the grammar were systematically translated into a corresponding hierarchy of OWL classes, with their relationships being modeled as part of a taxonomy of object and datatype properties. All the recent updates from the Move 2024 edition were also included, including Enum types and their variants.

- Outcome: The structural layer of the ontology was the result of this phase, and specifically, the architectural modeling of the language’s components and their relationships.

3.2. Architectural Enrichment via Documentation Analysis

- Process: We identified and formalized key architectural concepts that go beyond pure syntax (including the modeling of the Sui Object Model) by creating a specialized sui:Object class and formalizing its relationship with ownership types.

- Outcome: This phase produced the architectural layer, adding formal axioms to enforce rules of the Sui platform that cannot be violated or neglected (e.g., any sui:Object must have the key ability).

3.3. Behavioral Modeling via a Two-Phase, Evidence-Based Approach

- Pattern Curation from Literature: The process began with a systematic curation of high-level, language-agnostic security and business logic patterns from the academic literature and official language documentation. The objective was to identify a set of well-established patterns that represent the abstract security goals of decentralized applications. Thus, the ontology includes a library of four critical design patterns, adapting them to address the unique architectural characteristics of Sui’s object-centric data model: two of these (the Access Control and Circuit Breaker), are well-established design patterns, previously documented across the academic literature [7,45,51,85,86]. The other two patterns (the Time Incentivization and Escapability) were selected based on their formal introduction in recent research as design patterns worthy of systematic analysis [51,74] combined with their demonstrated prevalence in real-world smart contracts and empirical security taxonomies.

- Grounding in the Sui Framework: Once a conceptual pattern was identified, the next step was to analyze the official Sui Framework and established developer resources, in order to locate its idiomatic implementation within the Sui Move language (a direct, evidence-based mapping from literature to implementation). Our decision to rely on the above resources was a deliberate methodological choice, driven by the documented lack of transparency in the wider Move ecosystem, and as research has shown, it is difficult to acquire or trust the source code for most of the deployed Sui contracts (until September 2024, over 75% of the top Sui Move projects had not provided their source code) [19,20]. After a pattern was identified and its implementation validated, it was then formally modeled as a DCR graph and integrated into the ontology.

3.4. Design Patterns and Framework

- Access Control: Only authorized entities, typically the owner of a specific capability object, are allowed by this pattern to perform specific function executions, addressing the security concern of authorization, a topic frequently discussed across literature.

- Circuit Breaker: In response to an emergency or detected threat, this pattern provides a fail-safe mechanism, allowing the temporary suspension of critical contract functions.

- Time Incentivization: A mechanism that uses temporal constraints to reward or penalize actions, commonly found in vesting contracts and other DeFi protocols.

- Escapability: This pattern moves beyond traditional security by modelling the complex, stateful business logic of a smart contract and how it behaves over time, addressing the primary source of modern business logic flaws and vulnerabilities.

4. The Sui Move Ontology: A Detailed Model

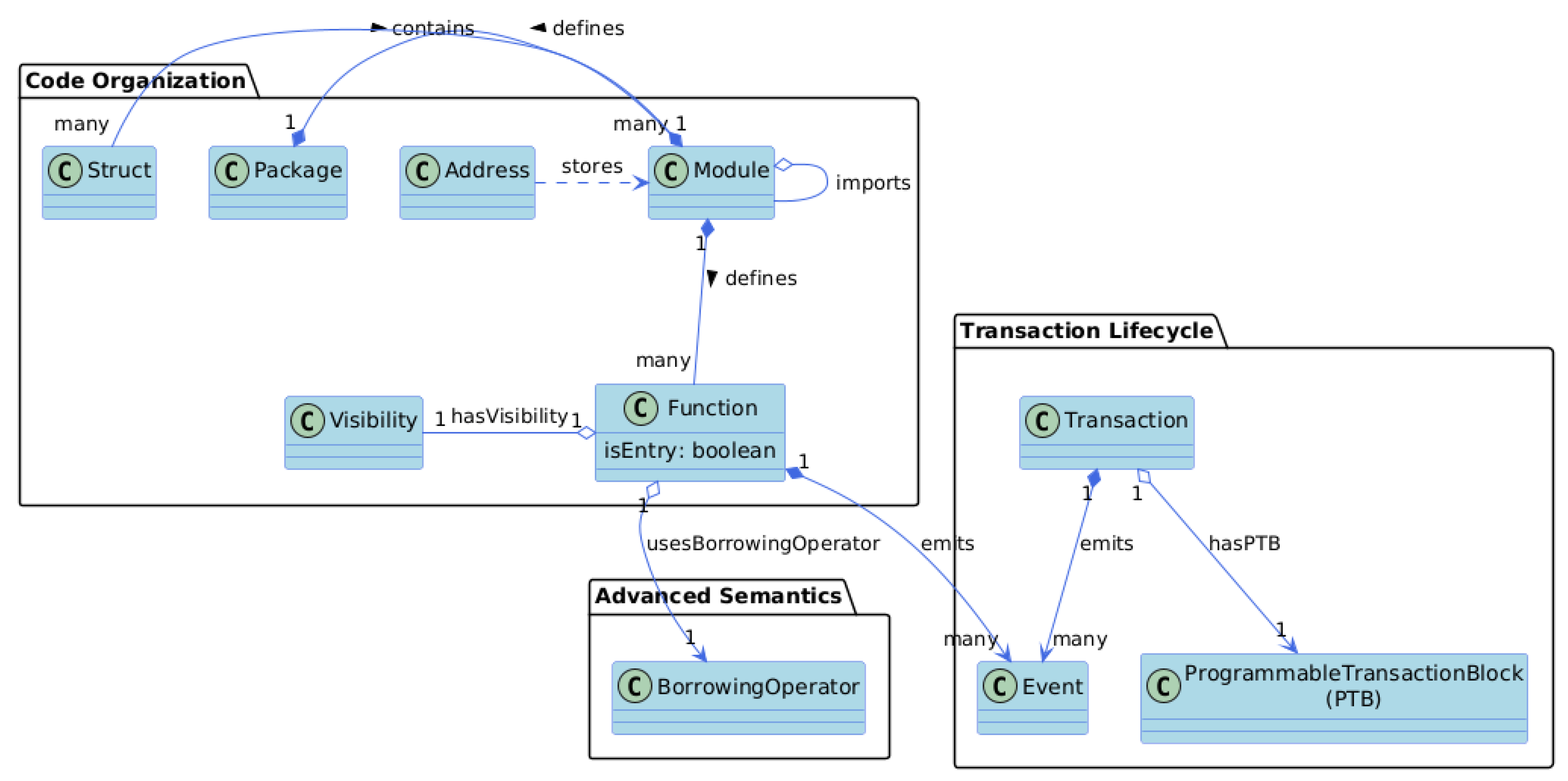

4.1. The Structural and Architectural Layer

4.1.1. Code Organization and Deployment Hierarchy

4.1.2. Modeling Core Language Constructs and Advanced Semantics

- The sui:Function class is annotated with properties that capture its behavior and accessibility.

- The isEntry: boolean datatype property differentiates functions directly invoked in a transaction (where access control must be enforced) from internal helper functions, a safety measure as entry functions are the primary point of entry an attacker could try to exploit.

- Function visibility is modeled via the sui:hasVisibility object property, which links a sui:Function to an individual of the sui:Visibility class. The :public, :publicPackage, and :private instances are included inside the sui:Visibility class and correspond to the language’s specific visibility modifiers.

4.1.3. The Transaction Lifecycle Model

- A sui:Transaction is the unit of an execution, submitted by a user.

- The sui:ProgrammableTransactionBlock, which is a composable sequence of commands (e.g., function calls, object transfers), is modeled inside the ontology through the sui:hasPTB property, explicitly specifying that a sui:Transaction has exactly one sui:ProgrammableTransactionBlock.

- Finally, the sui:emits property is used for modeling the emission of events (the outcome of a transaction), linking a transaction to the sui:Event instances that form this outcome and is broadcasted to the blockchain network.

- Micro-verification: Does the sequence of events emitted by the individual sui:Function calls match to the low-level process model, specified for that contract?

- Macro-verification: Does the final set of events emitted by the sui:Transaction match the high-level business process rules?

4.2. Modeling Modules: Contracts vs. Libraries

- Statelessness: Since a module does not define any sui:Object types (an ontological representation of a struct with the key ability), this condition recognizes those modules that do not introduce a new, on-chain, addressable state.

- Reusability: Other modules can target a module through numerous sui:imports relationships, suggesting that these particular module’s functions are intended for shared, reusable logic.

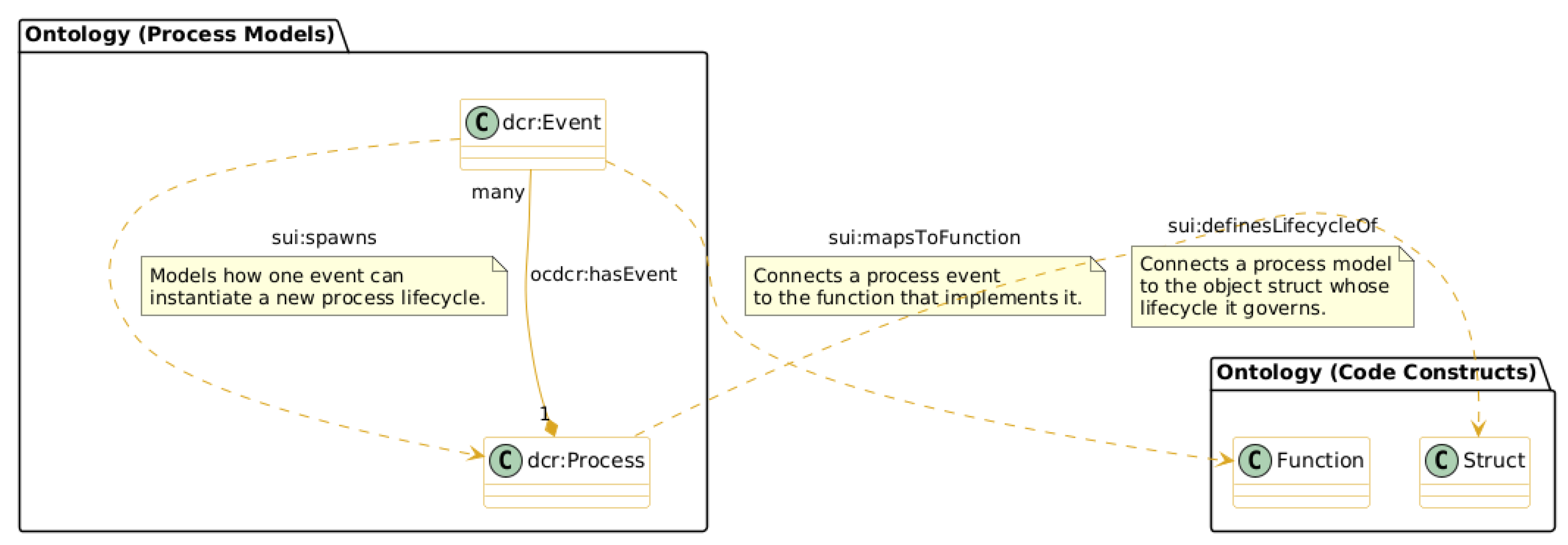

4.3. The Behavioral Layer: Formalizing Processes with OC-DCR Graphs

- sui:mapsToFunction: This property creates a direct link between an event in the process model (dcr:Event) and the specific sui:Function in the code that is responsible for implementing its logic.

- sui:definesLifecycleOf: This property connects an entire process model (dcr:Process) to the sui:Struct. This is the core element of our ontological model regarding its object-centric design, with the DCR graphs representing the entire set of valid state transitions an object can have.

- sui:spawns: The dynamic process instantiation is modeled through this property, in which the execution of one dcr:Event leads to the creation of a new instance of a dcr:Process (e.g., a new object with its own lifecycle).

4.3.1. Modeling Object Lifecycles

- sui:OwnershipType: This class (the "what") is created from the Sui Move language’s type system, fundamental for ensuring resource safety. Four primary instances are included (:AddressOwned, :Shared, :Immutable, and :Wrapped).

- sui:ObjectLifecycleState: This class (the "how") is a process-oriented representation of the state, including instances that model an object’s status within a specific business process, such as :Created, :Owned, :Transferred, and :Deleted.

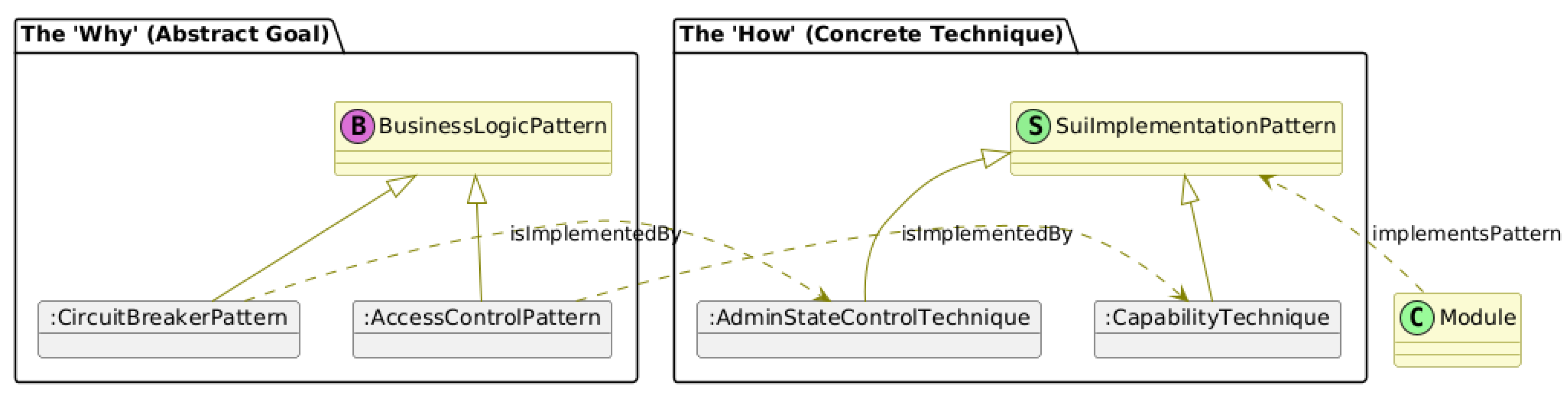

4.4. The Semantic Layer: The Dual-Layer Pattern Library

- sui:BusinessLogicPattern: This class represents the high-level, language-agnostic concept (the "why"). Instances of this class (e.g. :AccessControlPattern) represents established security design patterns.

- sui:SuiImplementationPattern: his class represents the low-level, idiomatic Sui Move technique used to realize an abstract goal (the "how"). Instances, such as the :CapabilityTechnique, are identified by analyzing authoritative codebases like the Sui Framework [81].

- First, the sui:isImplementedBy property links high-level patterns to the technique that is used for implementation. For example, to connect a high-level pattern to its low-level technique, the statement :CircuitBreakerPattern, sui:isImplementedBy, :AdminStateControlTechnique is used.

- Second, the sui:implementsPattern property links a specific code module to the implementation technique. The statement validator_module, sui:implementsPattern, :AdminStateControlTechnique for example, creates a direct link between the code and the pattern.

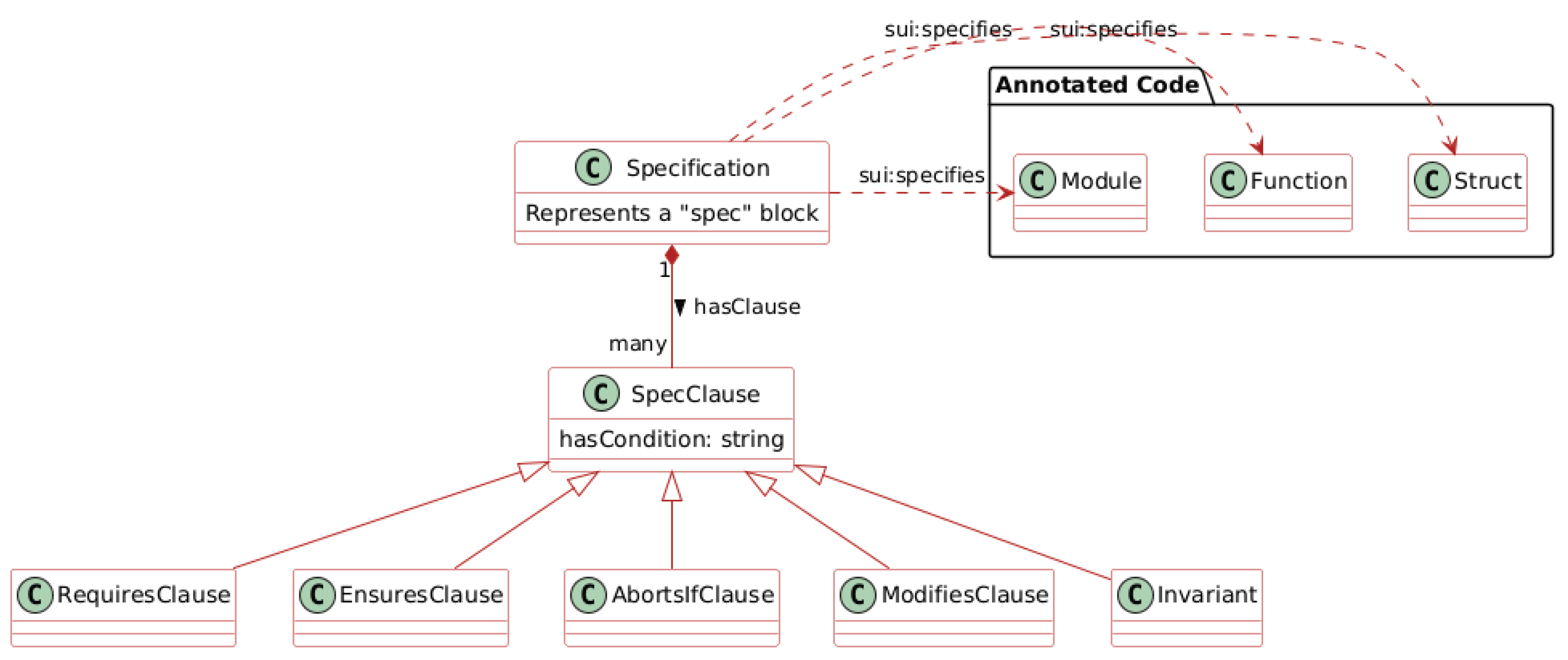

4.5. The Verification Layer

- sui:RequiresClause for function preconditions,

- sui:EnsuresClause for postconditions,

- sui:AbortsIfClause for defining failure conditions,

- sui:ModifiesClause for specifying which memory locations a function is allowed to change,

- sui:Invariant for defining state properties that must hold true across all operations.

5. Validating the Framework

5.1. Foundational Ontology Validation

5.2. DCR Pattern Model Validation

-

Selection of a Canonical Implementation: The identification of an implementation for each pattern was made from the Sui ecosystem, a critical methodological choice for ensuring our models are based on a verified codebase that works as the ground truth. The used codebases are the exact versions used at the time of evaluation and stored within our Github project repo:

- The Official Sui Framework: We used the transfer_policy.move (Access Control), coin.move (Circuit Breaker), and package.move (Escapability patterns) modules, representing core codebases that define the network’s foundational logic.

- The Official Sui Developer Documentation: For the Time Incentivization pattern, we used the linear.move example, representing community-accepted best practices.

- Mapping to the Ontology: We manually mapped the selected Sui Move code to the corresponding classes and properties in our ontological model, by creating instances that represent the specific code elements and defining the relationships between them (e.g., the transfer policy module implements the Access Control Technique).

- Process Analysis: We analyzed the control flow and logic of the implementation to verify that the real-world code’s behavior aligns with the behavioral rules defined in the corresponding OC-DCR model.

- Executable Model Validation: The ontology utilizes four primary DCR relations, with each DCR relation being mapped to a unique and consistent visual symbol (e.g., color and style of an arrow) provided from the online tool 2 that was found in the literature [53,73,74,89], and their semantics are defined as follows (Table 2):

- Graphs Testing: The final step of the validation involves using an online simulation-assisted tool in order to test the created visual DCR graphs. By executing both the valid ("happy path") and invalid ("attack path") scenarios, we verify that the behavior of the executable visual model corresponds to the rules defined by the ontology.

5.3. Internal Validation

-

Access Control Pattern: The simulation confirmed that access is dependent on a revocable capability.

- Happy Path: Executing AC_GrantRole enabled AC_ProtectedCall, validating the dcr:condition rule.

- Attack Path: After executing AC_GrantRole, executing AC_RevokeRole disabled AC_ProtectedCall, validating the dcr:exclusion rule. The three-event model (AC_GrantRole, AC_ProtectedCall, AC_RevokeRole) was validated to ensure the revocation capability correctly disables protected operations, confirming the dcr:exclusion semantics.

-

Circuit Breaker Pattern: The simulation validated the model’s ability to halt and resume key operations based on all specified rules.

- Happy Path: Executing CB_Pause disabled CB_OperationalCall and CB_Pause itself, while enabling CB_Unpause, validating the dcr:exclusion and dcr:inclusion rules.

- Attack Path: With the process in the "paused" state, any attempt to execute CB_OperationalCall was blocked by the simulator.

-

Time Incentivization Pattern: The simulation confirmed the time-dependent logic central to the pattern.

- Happy Path: Executing TI_Start enabled TI_Proceed and flagged it as a pending response, validating the dcr:response rule.

- Attack Path: An attempt to execute TI_Proceed before TI_Start was blocked, validating the dcr:condition rule.

-

Escapability Pattern: The simulation validated the one-way authorization flow required for an escape hatch mechanism.

- Happy Path: Executing ES_Authorize enabled ES_Escape, validating the dcr:condition rule.

- Attack Path: An attempt to execute ES_Escape from the initial state was blocked, validating the dcr:condition.

5.4. Qualitative External Validation

-

Access Control Pattern

- Canonical Implementation: The pattern has been found to be implemented into the transfer_policy.move Sui Framework’s codebase, allowing the creation of rules that restrict how certain assets can be transferred.

-

Ontological Mapping: The TransferPolicy struct is mapped to the StateObject class, and the TransferPolicyCap struct (the one that grants administrative rights) is mapped to CapabilityObject. The pattern’s functions are then mapped to specific access control events:

- –

- The new() function maps to the AC_GrantRole event.

- –

- The protected withdraw() function maps to the AC_ProtectedCall event.

- –

- The destroy_and_withdraw() function maps to the AC_RevokeRole event.

-

Process Analysis: The implementation’s logic aligns with our DCR graph:

- –

- The AC_ProtectedCall (withdraw) requires the TransferPolicyCap to be created by AC_GrantRole (new), satisfying the dcr:condition.

- –

- The feature to destroy the capability via calling the destroy_and_withdraw() function (AC_RevokeRole), satisfies the dcr:exclusion rule and ensures that access, once granted, is also verifiably revocable.

-

Circuit Breaker Pattern

- Canonical Implementation: The pattern has been found to be implemented into the coin.move Sui Framework’s codebase, implementing the DenyCapV2 mechanism for providing built-in circuit breaker capabilities.

-

Ontological Mapping: This pattern’s capabilities inside the above codebase are defined by several key structs and functions:

- –

- The TreasuryCap<T> struct (for minting/burning) is mapped to CapabilityObject.

- –

- The DenyCapV2<T> struct (for pause operations) is mapped to the CircuitBreakerTechnique class.

- –

- The deny_list_v2_enable_global_pause() function maps to the CB_Pause event, while the deny_list_v2_disable_global_pause() maps to CB_Unpause.

- –

- Protected operations like mint() and burn() map to the CB_OperationalCall event.

-

Process Analysis:The implementation is a dual-layer control mechanism, aligning with our DCR graph. Initially, the CB_OperationalCall event is permitted, but with the execution of deny_list_v2_enable_global_pause() function (CB_Pause in our ontological mapping), the system transit to a paused state, thus satisfying two key conditions:

- –

- Implementing the dcr:exclusion rule disables the CB_OperationalCall.

- –

- The CB_Pause event enables the CB_Unpause event (similar to our dcr:inclusion), allowing the system to be restored.

-

Time Incentivization Pattern

- Canonical Implementation: The pattern has been found to be implemented into the linear.move codebase from the Sui Vesting Framework, which defines a linear token vesting schedule to incentivize long-term holding.

-

Ontological Mapping: The key components of the Time Incentivization pattern are mapped to our ontology as detailed below:

- –

- The state of the pattern that includes the vesting schedule is held in the Wallet struct, and mapped to the StateObject class.

- –

- The claimable() function, which calculates available tokens, is mapped to the TI_Start event.

- –

- The claim() function, which allows withdrawal, is mapped to the TI_Proceed event.

- –

- The vesting completion state is mapped to the TI_Timeout event.

-

Process Analysis:

- –

- The TI_Proceed (claim) event enforces the dcr:condition by yielding tokens proportional to the time elapsed since TI_Start.

- –

- The linear formula (self.balance.value() * elapsed) / self.duration) calculates a yield proportional to the holding period, thus rewarding long-term holding.

-

Escapability Pattern

- Canonical Implementation: The pattern has been found to be implemented into the package.move Sui Framework’s codebase.

- Ontological Mapping: The UpgradeCap struct, which grants upgrade authority, is the CapabilityObject. The authorize_upgrade() function maps to the ES_Authorize event, and the commit_upgrade() function maps to the ES_Escape event.

- Process Analysis: The control flow follows our DCR graph’s rules. The ES_Escape action (commit_upgrade) requires the prior completion of the ES_Authorize function call (authorize_upgrade). Thereby, the dcr:condition relationship is satisfied, ensuring that contract upgrades are deliberate and authorized.

6. Limitations and Future Work

- A promising future research direction is the formalization of "pattern compositions" as first-class concepts, allowing tools to reason about how patterns interfere with, or reinforce one another, within a single module-contract.

- The ontological framework could provide developers with real-time, semantically-aware feedback through its integration into Integrated Development Environments (IDEs). For instance, an IDE could recognize when a developer is implementing a vesting schedule and guide them to ensure that its logic correctly matches the Time Incentivization pattern.

- The ontology’s Verification layer could be used and leveraged for building tools that i) could perform an analysis of a project’s verification structure (e.g. automatic identification of functions that lack certain blocks) thus pinpoint unverified components or ii) by upgrading it in order to create an automated procedure of auditing the formal specifications themselves, and not just checking the presence of a spec clause (moving from describing code and its specifications to analyzing and validating the relationship between them).

7. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adisa, O.; Ilugbusi, B.S.; Obi, O.C.; Awonuga, K.F.; Adelekan, O.A.; Asuzu, O.F.; Ndubuisi, N.L. Decentralized Finance (DEFI) in the US economy: A review: Assessing the rise, challenges, and implications of blockchain-driven financial systems. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews 2024, 21, 2313–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez Melendez, E.I.; Bergey, P.; Smith, B. Blockchain technology for supply chain provenance: increasing supply chain efficiency and consumer trust. Supply chain management: An international journal 2024, 29, 706–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; He, D.; An, H.; Luo, M.; Peng, C. The governance technology for blockchain systems: a survey. Frontiers of Computer Science 2024, 18, 182813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, N. Formalizing and securing relationships on public networks.

- Eshghie, M.; Artho, C.; Stammler, H.; Ahrendt, W.; Hildebrandt, T.; Schneider, G. Highguard: Cross-chain business logic monitoring of smart contracts. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 39th IEEE/ACM International Conference on Automated Software Engineering, 2024, pp. 2378–2381.

- Metin, B.; Wynn, M.; Tunalı, A.; Kepir, Y. Business Logic Vulnerabilities in the Digital Era: A Detection Framework Using Artificial Intelligence. Information 2025, 16, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannengiesser, N.; Lins, S.; Sander, C.; Winter, K.; Frey, H.; Sunyaev, A. Challenges and common solutions in smart contract development. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering 2021, 48, 4291–4318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, S.S.; Joshi, S.; Singh, D.; Kaur, M.; Lee, H.N. Systematic review of security vulnerabilities in ethereum blockchain smart contract. Ieee Access 2022, 10, 6605–6621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.; Phansalkar, S. Blockchain Security in Focus: A Comprehensive Investigation into Threats, Smart Contract Security, Cross-Chain Bridges, Vulnerabilities Detection Tools & Techniques. IEEE Access 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Alazab, M.; Alhyari, S.; Awajan, A.; Abdallah, A.B. Blockchain technology in supply chain management: an empirical study of the factors affecting user adoption/acceptance. Cluster Computing 2021, 24, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Li, Y. An empirical study on the adoption of blockchain-based games from users’ perspectives. The Electronic Library 2021, 39, 596–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Yin, X.; Ying, C.; Ni, C.; Luo, Y. A Preference-Driven Methodology for High-Quality Solidity Code Generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.03006 2025.

- Ghaleb, A.; Pattabiraman, K. How effective are smart contract analysis tools? evaluating smart contract static analysis tools using bug injection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 29th ACM SIGSOFT international symposium on software testing and analysis, 2020, pp. 415–427.

- Durieux, T.; Ferreira, J.F.; Abreu, R.; Cruz, P. Empirical review of automated analysis tools on 47,587 ethereum smart contracts. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE 42nd International conference on software engineering, 2020, pp. 530–541.

- Piantadosi, V.; Rosa, G.; Placella, D.; Scalabrino, S.; Oliveto, R. Detecting functional and security-related issues in smart contracts: A systematic literature review. Software: Practice and Experience 2023, 53, 465–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaliasos, S.; Charalambous, M.A.; Zhou, L.; Galanopoulou, R.; Gervais, A.; Mitropoulos, D.; Livshits, B. Smart contract and defi security tools: Do they meet the needs of practitioners? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 46th IEEE/ACM International Conference on Software Engineering, 2024, pp. 1–13.

- Mysten Labs. The Sui Smart Contracts Platform. https://docs.sui.io/paper/sui.pdf, 2022. Accessed: 2025-09-19.

- Welc, A.; Blackshear, S. Sui move: Modern blockchain programming with objects. In Proceedings of the Companion Proceedings of the 2023 ACM SIGPLAN International Conference on Systems, Programming, Languages, and Applications: Software for Humanity, 2023, pp. 53–55.

- Van Tonder, R. Verifying and displaying move smart contract source code for the sui blockchain. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/ACM 46th International Conference on Software Engineering: Companion Proceedings, 2024, pp. 26–29.

- Chen, E.; Tang, X.; Xiao, Z.; Li, C.; Li, S.; Wu, T.; Wang, S.; Chalkias, K.K. SuiGPT MAD: Move AI Decompiler to Improve Transparency and Auditability on Non-Open-Source Blockchain Smart Contract. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ACM on Web Conference 2025, 2025, pp. 1567–1576.

- Wenhua, Z.; Qamar, F.; Abdali, T.A.N.; Hassan, R.; Jafri, S.T.A.; Nguyen, Q.N. Blockchain technology: security issues, healthcare applications, challenges and future trends. Electronics 2023, 12, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesekara, P.A.D.S.N.; Gunawardena, S. A review of blockchain technology in knowledge-defined networking, its application, benefits, and challenges. Network 2023, 3, 343–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavita, S.; Shinde, S. A comprehensive survey of consensus protocols, challenges, and attacks of blockchain network. In Proceedings of the 2024 Fourth International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Computing, Communication and Sustainable Technologies (ICAECT). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–6.

- Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhou, X.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Wu, J. An empirical study of solidity language features. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 21st International Conference on Software Quality, Reliability and Security Companion (QRS-C). IEEE, 2021, pp. 698–707.

- Patrignani, M.; Blackshear, S. Robust safety for move. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 36th Computer Security Foundations Symposium (CSF). IEEE, 2023, pp. 308–323.

- Garfatta, I.; Klai, K.; Gaaloul, W.; Graiet, M. A survey on formal verification for solidity smart contracts. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Australasian Computer Science Week Multiconference, 2021, pp. 1–10.

- Tolmach, P.; Li, Y.; Lin, S.W.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z. A survey of smart contract formal specification and verification. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2021, 54, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Luo, J.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Li, P.; Zhao, J. The Formal Verification of Aptos Coin. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Security. Springer, 2024, pp. 3–22.

- Zhu, H.; Yang, L.; Wang, L.; Sheng, V.S. A survey on security analysis methods of smart contracts. IEEE Transactions on Services Computing 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoletti, M.; Crafa, S.; Lipparini, E. Formal verification in Solidity and Move: insights from a comparative analysis. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.13929 2025.

- Perez, D.; Livshits, B. Smart contract vulnerabilities: Does anyone care. arXiv preprint arXiv:1902.06710 2019, pp. 1–15.

- Tang, X.; Zhou, K.; Cheng, J.; Li, H.; Yuan, Y. The vulnerabilities in smart contracts: A survey. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Security. Springer, 2021, pp. 177–190.

- Zhou, H.; Milani Fard, A.; Makanju, A. The state of ethereum smart contracts security: Vulnerabilities, countermeasures, and tool support. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy 2022, 2, 358–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Wu, R.; Li, X.; Chan, S.; Guizani, M. Detection of vulnerabilities of blockchain smart contracts. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2023, 10, 12178–12185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejazi, N.; Lashkari, A.H. A comprehensive survey of smart contracts vulnerability detection tools: Techniques and methodologies. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2025, p. 104142.

- Tan, T.M.; Saraniemi, S. Trust in blockchain-enabled exchanges: Future directions in blockchain marketing. Journal of the Academy of marketing Science 2023, 51, 914–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babel, K.; Chursin, A.; Danezis, G.; Kichidis, A.; Kokoris-Kogias, L.; Koshy, A.; Sonnino, A.; Tian, M. Mysticeti: Reaching the limits of latency with uncertified dags. arXiv 2023. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.14821.

- Danezis, G.; Kokoris-Kogias, L.; Sonnino, A.; Spiegelman, A. Narwhal and tusk: a dag-based mempool and efficient bft consensus. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Seventeenth European Conference on Computer Systems, 2022, pp. 34–50.

- Giatzis, A.; Papangelou, S.; Georgiadis, C.K. A Comparative Study of Solidity and Sui Move: Advancing Smart Contract Development. IEEE Access 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.E.; Cheang, K.; Qadeer, S.; Grieskamp, W.; Blackshear, S.; Park, J.; Zohar, Y.; Barrett, C.; Dill, D.L. The move prover. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Aided Verification. Springer, 2020, pp. 137–150.

- Wedyan, F.; Abufakher, S. Impact of design patterns on software quality: a systematic literature review. IET Software 2020, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Yin, J.; Lu, R.; Lin, X. A comprehensive survey on smart contract construction and execution: paradigms, tools, and systems. Patterns 2021, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Sorbo, A.; Laudanna, S.; Vacca, A.; Visaggio, C.A.; Canfora, G. Profiling gas consumption in solidity smart contracts. Journal of Systems and Software 2022, 186, 111193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Chen, J.; Jiang, Z.; Zheng, Z. Revealing hidden threats: An empirical study of library misuse in smart contracts. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 46th IEEE/ACM International Conference on Software Engineering, 2024, pp. 1–12.

- Azimi, S.; Golzari, A.; Ivaki, N.; Laranjeiro, N. A systematic review on smart contracts security design patterns. Empirical Software Engineering 2025, 30, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, A.M.; Adams, B.; Oliva, G.A.; Hassan, A.E. A large-scale exploratory study on the proxy pattern in ethereum. Empirical Software Engineering 2024, 29, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Lo, D.; Kochhar, P.S.; Le, X.B.D.; Xia, X.; Feng, Y.; Chen, Z.; Xu, B. Smart contract development: Challenges and opportunities. IEEE transactions on software engineering 2019, 47, 2084–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivieri, L.; Arceri, V.; Chachar, B.; Negrini, L.; Tagliaferro, F.; Spoto, F.; Ferrara, P.; Cortesi, A. General-purpose Languages for Blockchain Smart Contracts Development: A Comprenhensive Study. IEEE Access 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzano, F.; Marchesi, L.; Antenucci, C.K.; Scalabrino, S.; Tonelli, R.; Oliveto, R.; Pareschi, R. Bridging the Gap: A Comparative Study of Academic and Developer Approaches to Smart Contract Vulnerabilities. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.12443 2025.

- Liao, Z.; Hao, S.; Nan, Y.; Zheng, Z. Smartstate: Detecting state-reverting vulnerabilities in smart contracts via fine-grained state-dependency analysis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 32nd ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis, 2023, pp. 980–991.

- Ghaleb, A.; Rubin, J.; Pattabiraman, K. Achecker: Statically detecting smart contract access control vulnerabilities. In 2023 IEEE/ACM 45th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE), 2023.

- Majd, N.E.; Hinojosa, A.; Fisher, C.; Landeros, F.; Baldimtsi, F. An Analytical Performance Evaluation on Sui Move Object-Centric Models. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Blockchain and Cryptocurrency (ICBC). IEEE, 2025, pp. 1–3.

- Xu, Y.; Slaats, T.; Düdder, B.; Troels Hildebrandt, T.; Van Cutsem, T. Safe design and evolution of smart contracts using dynamic condition response graphs to model generic role-based behaviors. Journal of Software: Evolution and Process 2025, 37, e2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, S.; Salim, S.; Ullah, A.; Vaccargiu, M. A Move Sui library for secure, certified and trusted supply chain ownership management. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/ACM 7th International Workshop on Emerging Trends in Software Engineering for Blockchain (WETSEB). IEEE, 2025, pp. 50–56.

- Singh, A.; Parizi, R.M.; Zhang, Q.; Choo, K.K.R.; Dehghantanha, A. Blockchain smart contracts formalization: Approaches and challenges to address vulnerabilities. Computers & Security 2020, 88, 101654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wu, D.; Xue, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Xu, Z.; Xie, X.; Liu, Y. Gptscan: Detecting logic vulnerabilities in smart contracts by combining gpt with program analysis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/ACM 46th International Conference on Software Engineering, 2024, pp. 1–13.

- Lin, X.; Xie, Q.; Zhao, B.; Tian, Y.; Zonouz, S.; Ruan, N.; Li, J.; Beyah, R.; Ji, S. PROMFUZZ: Leveraging LLM-Driven and Bug-Oriented Composite Analysis for Detecting Functional Bugs in Smart Contracts. arXiv e-prints 2025, pp. arXiv–2503.

- Rameder, H.; Di Angelo, M.; Salzer, G. Review of automated vulnerability analysis of smart contracts on ethereum. Frontiers in Blockchain 2022, 5, 814977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soud, M.; Nuutinen, W.; Liebel, G. Soley: Identification and automated detection of logic vulnerabilities in ethereum smart contracts using large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.16244 2024.

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Xu, W.; Lin, Z. Demystifying exploitable bugs in smart contracts. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/ACM 45th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE). IEEE, 2023, pp. 615–627.

- Zhou, L.; Xiong, X.; Ernstberger, J.; Chaliasos, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Qin, K.; Wattenhofer, R.; Song, D.; Gervais, A. Sok: Decentralized finance (defi) attacks. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP). IEEE, 2023, pp. 2444–2461.

- Carpentier-Desjardins, C.; Paquet-Clouston, M.; Kitzler, S.; Haslhofer, B. Mapping the DeFi crime landscape: an evidence-based picture. Journal of Cybersecurity 2025, 11, tyae029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studer, R.; Benjamins, V.R.; Fensel, D. Knowledge engineering: Principles and methods. Data & knowledge engineering 1998, 25, 161–197. [Google Scholar]

- Van Heijst, G.; Schreiber, A.T.; Wielinga, B.J. Using explicit ontologies in KBS development. International journal of human-computer studies 1997, 46, 183–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noy, N.F.; McGuinness, D.L.; et al. Ontology development 101: A guide to creating your first ontology, 2001.

- Strmečki, D.; Magdalenić, I.; Kermek, D. An Overview on the use of Ontologies in Software Engineering. Journal of computer science 2016, 12, 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diatta, B.; Basse, A.; Ouya, S. PasOnto: Ontology for learning Pascal programming language. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON). IEEE, 2019, pp. 749–754.

- Nongkhai, L.N.; Wang, J.; Mendori, T. Developing an Ontology of Multiple Programming Languages from the Perspective of Computational Thinking Education. International Association for Development of the Information Society 2022.

- Bella, G.; Cantone, D.; Longo, C.; Nicolosi Asmundo, M.; Santamaria, D.F. Blockchains through ontologies: the case study of the Ethereum ERC721 standard in OASIS. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Intelligent and Distributed Computing. Springer, 2021, pp. 249–259.

- Cano-Benito, J.; Cimmino, A.; García-Castro, R. Toward the ontological modeling of smart contracts: a solidity use case. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 140156–140172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Woensel, W.; Seneviratne, O. Semantic Interoperability on Blockchain by Generating Smart Contracts Based on Knowledge Graphs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.12171 2024. Accessed: 2025-10-19.

- Dominguez, J.A.; Gonnet, S.; Vegetti, M. The role of ontologies in smart contracts: A systematic literature review. Journal of Industrial Information Integration 2024, 40, 100630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, A.; Awaysheh, F.; López, H.A. BEST: A Unified Business Process Enactment via Streams and Tables for Service Computing. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.14848 2025.

- Eshghie, M.; Ahrendt, W.; Artho, C.; Hildebrandt, T.T.; Schneider, G. Capturing smart contract design with dcr graphs. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Software Engineering and Formal Methods. Springer, 2023, pp. 106–125.

- Xu, Y.; Slaats, T.; Dudder, B.; Hildebrandt, T.T. Adding generic role-and process-based behaviors to smart contracts using dynamic condition response graphs. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Software and System Processes (ICSSP). IEEE Computer Society, 2023, pp. 70–80.

- Christfort, A.K.; Rivkin, A.; Fahland, D.; Hildebrandt, T.T.; Slaats, T. Discovery of object-centric declarative models. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th International Conference on Process Mining (ICPM). IEEE, 2024, pp. 121–128.

- Garfatta, I.; Klai, K.; Gaaloul, W. Integrating Business Process Context into Solidity-to-CPN Formal Verification. In Proceedings of the 2024 32nd International Conference on Enabling Technologies: Infrastructure for Collaborative Enterprises (WETICE). IEEE, 2024, pp. 68–73.

- Bartoletti, M.; Lipparini, E.; Pompianu, L. LLMs as verification oracles for Solidity. arXiv preprint arXiv:2509.19153 2025.

- Poveda-Villalón, M.; Fernández-Izquierdo, A.; Fernández-López, M.; García-Castro, R. LOT: An industrial oriented ontology engineering framework. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2022, 111, 104755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labs, M. Move Language Tree-sitter Grammar. https://github.com/MystenLabs/sui/blob/main/external-crates/move/tooling/tree-sitter/src/grammar.json, 2025. Accessed: 2025-07-11.

- Labs, M. Sui: A Next-Generation Smart Contract Platform. https://github.com/MystenLabs/sui. Accessed: 2025-07-19.

- Move Book Contributors. The Move Book: A Guide to the Move Programming Language and Sui Blockchain. https://move-book.com/. Accessed: 2025-07-19.

- Labs, M. Sui Documentation. https://docs.sui.io/. Accessed: 2025-07-19.

- Labs, M. Introduction to the Sui Book. https://intro.sui-book.com/. Accessed: 2025-07-19.

- Six, N.; Herbaut, N.; Salinesi, C. Blockchain software patterns for the design of decentralized applications: A systematic literature review. Blockchain: Research and Applications 2022, 3, 100061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seneviratne, O. The Feasibility of a Smart Contract" Kill Switch". In Proceedings of the 2024 6th International Conference on Blockchain Computing and Applications (BCCA). IEEE, 2024, pp. 473–480.

- Guarino, N.; Sales, T.P.; Guizzardi, G. Reification and truthmaking patterns. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Conceptual Modeling. Springer, 2018, pp. 151–165.

- Guizzardi, G.; Guarino, N. Explanation, semantics, and ontology. Data & Knowledge Engineering 2024, 153, 102325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debois, S.; Hildebrandt, T.T.; Marquard, M.; Slaats, T. The DCR Graphs Process Portal. In Proceedings of the BPM (Demos), 2016, pp. 7–11.

| 1 | |

| 2 |

| Aspect | sui:OwnershipType | sui:ObjectLifecycleState |

| Models | Resource safety and memory management. | Object’s status within a business process |

| Scope | High-level | Aplication-specific |

| Examples | :AddressOwned, :Shared | :Created, :Transferred |

| Enforced By | Sui Move Compiler and Runtime | OC-DCR Process Model and Application Logic |

| Expression | Events Relations | Arrows Colors |

|---|---|---|

| B dcr:condition A | A must happen before B | Orange |

| A dcr:response B | If A happens, B becomes a required future action | Blue |

| A dcr:exclusion B | If A happens, B is permanently disabled | Red |

| A dcr:inclusion B | If A happens, it enables B and is available to happen | Green |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).