Submitted:

27 October 2025

Posted:

28 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related works

2.1. Motion Models

2.2. Cost Matrix

2.3. Trajectories Management

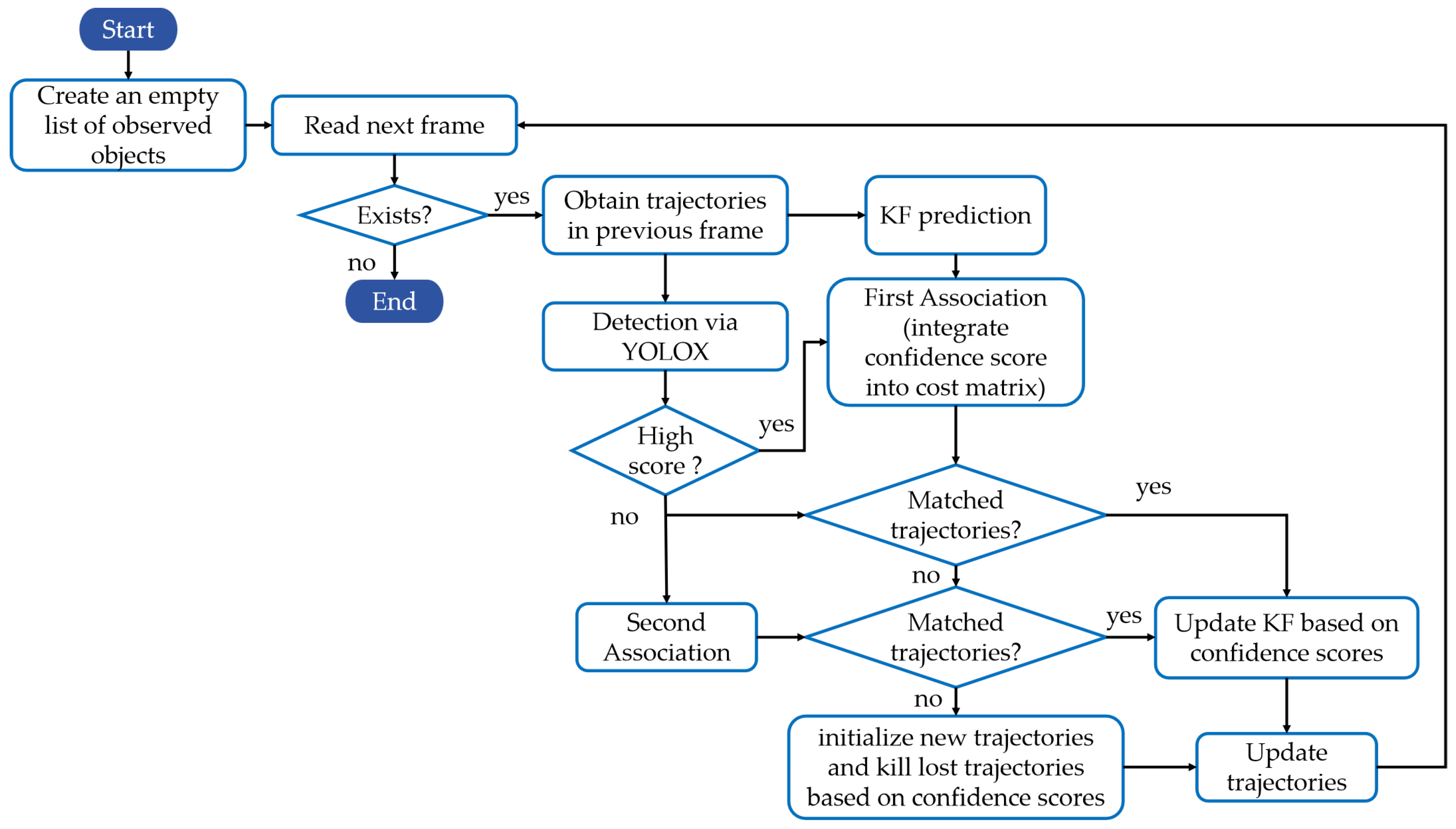

3. Method

3.1. Confidence-Based Adaptive KF

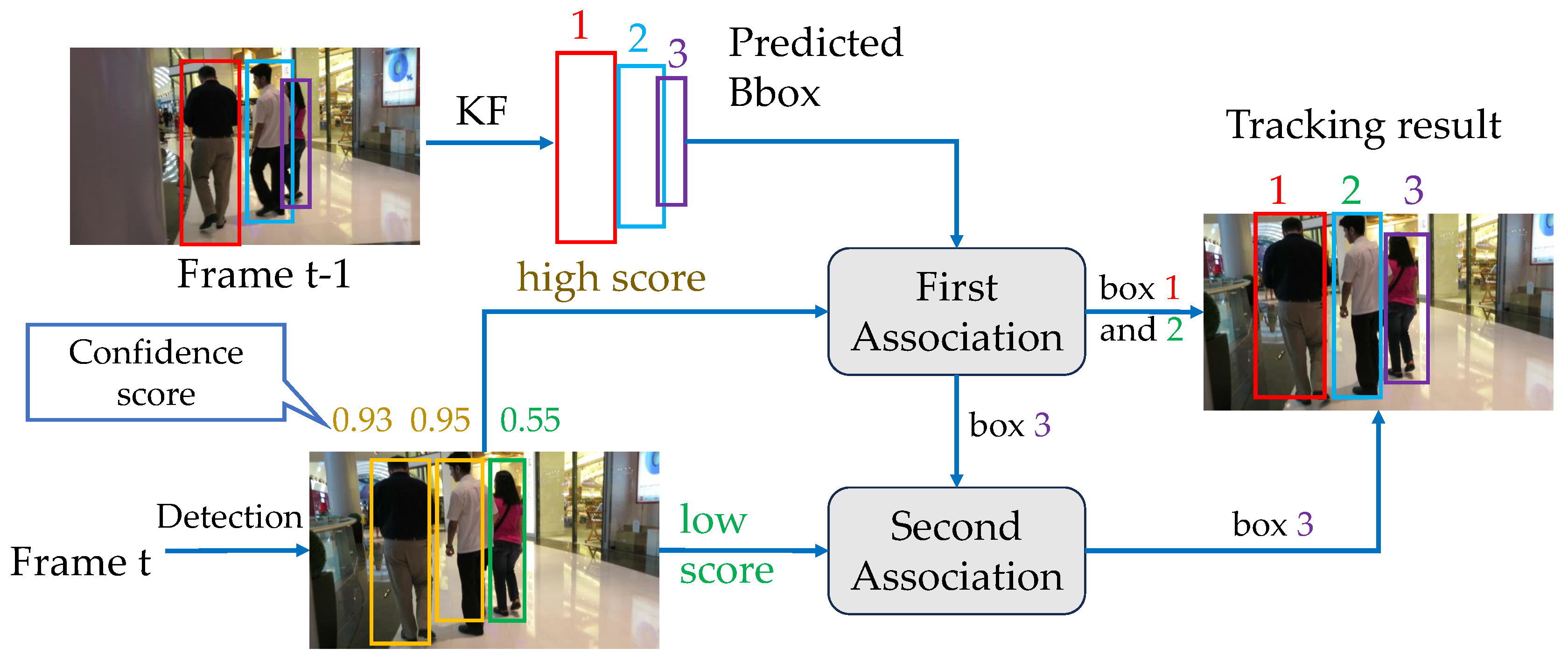

3.2. Data Association

3.3. Deletion Strategy

3.4. Tracking Procedure

4. Experiment

4.1. Datasets

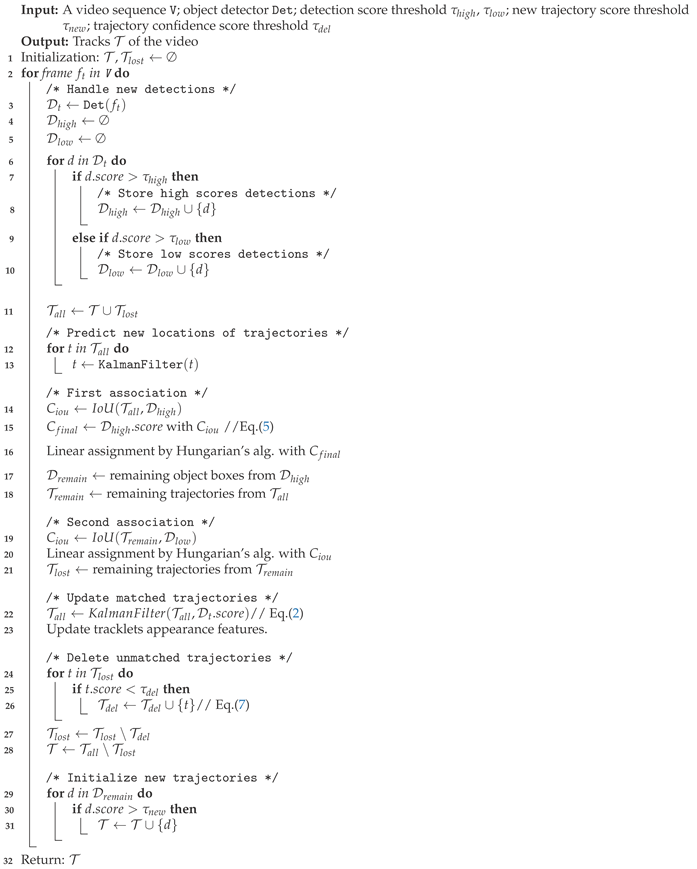

| Algorithm 1: Pseudo-code of tracking |

|

| Note: Trajectory recovery process is included in the matching process of lost trajectories. |

4.2. Metrics

4.3. Implementation Details

4.4. Experimental Results

4.4.1. Resutls on MOT17

4.4.2. Results on MOT20

4.4.3. Comprehensive Analysis

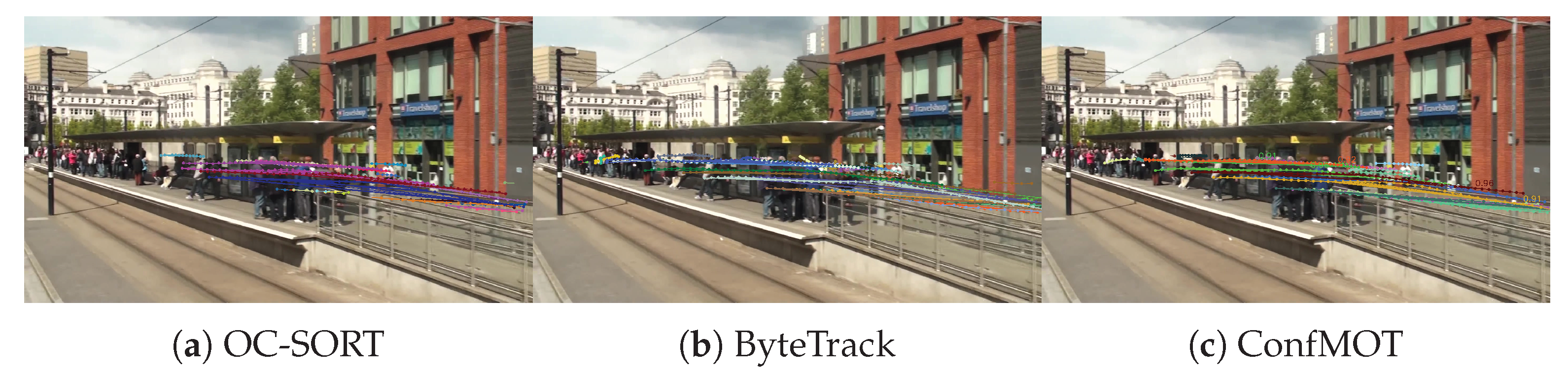

4.4.4. Visualization of Trajectories

4.5. Ablation Studies

4.5.1. KF Based on the Confidence Score

4.5.2. Deletion Strategy based on the confidence score

4.5.3. Cost matrix based on the confidence score

5. Conclusion

Funding

References

- N. Wojke, A. Bewley, D. Paulus, Simple online and realtime tracking with a deep association metric, in: 2017 IEEE international conference on image processing (ICIP), IEEE, 2017, pp. 3645–3649. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, P. Sun, Y. Jiang, D. Yu, F. Weng, Z. Yuan, P. Luo, W. Liu, X. Wang, Bytetrack: Multi-object tracking by associating every detection box, in: Computer Vision–ECCV 2022: 17th European Conference, Tel Aviv, Israel, October 23–27, 2022, Proceedings, Part XXII, Springer, 2022, pp. 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, T. Wang, X. Zhang, Motrv2: Bootstrapping end-to-end multi-object tracking by pretrained object detectors, in: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2023, pp. 22056–22065. [CrossRef]

- A. Bewley, Z. Ge, L. Ott, F. Ramos, B. Upcroft, Simple online and realtime tracking, in: 2016 IEEE international conference on image processing (ICIP), IEEE, 2016, pp. 3464–3468. [CrossRef]

- Lifan Sun, Jiayi Zhang, Dan Gao, Bo Fan, Zhumu Fu. Occlusion-aware visual object tracking based on multi-template updating Siamese network. Digital Signal Processing. 148 (2024) 104440. [CrossRef]

- H. Li, Y. Liu, X. Liang, Y. Yuan, Y. Cheng, G. Zhang, S. Tamura, Multi-object tracking via deep feature fusion and association analysis, Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 124 (2023) 106527.

- Y. Xu, Y. Ban, G. Delorme, C. Gan, D. Rus, X. Alameda-Pineda, Transcenter: Transformers with dense representations for multiple-object tracking, IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence (2022). [CrossRef]

- Z. Liu, X. Huang, J. Sun, X. Zhang, AMtrack: Anti-occlusion multi-object tracking algorithm, Signal, Image and Video Processing, vol. 18, no. 12, pp. 9305–9318, 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Fu, X. Wang, H. Yu, K. Niu, B. Li, X. Xue, Denoising-mot: Towards multiple object tracking with severe occlusions, in: Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, 2023, pp. 2734–2743. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang, L. Zheng, Y. Liu, Y. Li, S. Wang, Towards real-time multi-object tracking, in: Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, August 23–28, 2020, Proceedings, Part XI 16, Springer, 2020, pp. 107–122.

- Z. Ge, S. Liu, F. Wang, Z. Li, J. Sun, Yolox: Exceeding yolo series in 2021, arXiv preprint arXiv:2107.08430 (2021). [CrossRef]

- A. Milan, L. Leal-Taixé, I. Reid, S. Roth, K. Schindler, Mot16: A benchmark for multi-object tracking, arXiv preprint arXiv:1603.00831 (2016). [CrossRef]

- P. Dendorfer, H. Rezatofighi, A. Milan, J. Shi, D. Cremers, I. Reid, S. Roth, K. Schindler, L. Leal-Taixé, Mot20: A benchmark for multi object tracking in crowded scenes, arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.09003 (2020). [CrossRef]

- J. Cao, J. Pang, X. Weng, R. Khirodkar, K. Kitani, Observation-centric sort: Rethinking sort for robust multi-object tracking, in: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2023, pp. 9686–9696. [CrossRef]

- S. You, H. Yao, C. Xu, Multi-object tracking with spatial-temporal topology-based detector, IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 32 (5) (2021) 3023–3035. [CrossRef]

- Y. Du, J. Wan, Y. Zhao, B. Zhang, Z. Tong, J. Dong, Giaotracker: A comprehensive framework for mcmot with global information and optimizing strategies in visdrone 2021, in: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2021, pp. 2809–2819. [CrossRef]

- T. Khurana, A. Dave, D. Ramanan, Detecting invisible people, in: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021, pp. 3174–3184. [CrossRef]

- G. Wang, R. Gu, Z. Liu, W. Hu, M. Song, J.-N. Hwang, Track without appearance: Learn box and tracklet embedding with local and global motion patterns for vehicle tracking, in: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2021, pp. 9876–9886. [CrossRef]

- P. Bergmann, T. Meinhardt, L. Leal-Taixe, Tracking without bells and whistles, in: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2019, pp. 941–951. [CrossRef]

- L. Chen, H. Ai, Z. Zhuang, C. Shang, Real-time multiple people tracking with deeply learned candidate selection and person re-identification, in: 2018 IEEE international conference on multimedia and expo (ICME), IEEE, 2018, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, C. Wang, X. Wang, W. Zeng, W. Liu, Fairmot: On the fairness of detection and re-identification in multiple object tracking, International Journal of Computer Vision 129 (2021) 3069–3087. [CrossRef]

- S. Shao, Z. Zhao, B. Li, T. Xiao, G. Yu, X. Zhang, J. Sun, Crowdhuman: A benchmark for detecting human in a crowd, arXiv preprint arXiv:1805.00123 (2018). [CrossRef]

- S. Zhang, R. Benenson, B. Schiele, Citypersons: A diverse dataset for pedestrian detection, in: Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 3213–3221. [CrossRef]

- A. Ess, B. Leibe, K. Schindler, L. Van Gool, A mobile vision system for robust multi-person tracking, in: 2008 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, IEEE, 2008, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- T.-Y. Lin, M. Maire, S. Belongie, J. Hays, P. Perona, D. Ramanan, P. Dollár, C. L. Zitnick, Microsoft coco: Common objects in context, in: Computer Vision–ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, September 6-12, 2014, Proceedings, Part V 13, Springer, 2014, pp. 740–755. [CrossRef]

- P. Sun, J. Cao, Y. Jiang, R. Zhang, E. Xie, Z. Yuan, C. Wang, P. Luo, Transtrack: Multiple object tracking with transformer, arXiv preprint arXiv:2012.15460 (2020).

- J. Cai, M. Xu, W. Li, Y. Xiong, W. Xia, Z. Tu, S. Soatto, Memot: multi-object tracking with memory, in: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2022, pp. 8090–8100. [CrossRef]

- J. Kong, E. Mo, M. Jiang, T. Liu, Motfr: Multiple object tracking based on feature recoding, IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 32 (11) (2022) 7746–7757. [CrossRef]

- P. Sun, J. Cao, Y. Jiang, R. Zhang, E. Xie, Z. Yuan, C. Wang, P. Luo, Transtrack: Multiple object tracking with transformer, arXiv preprint arXiv:2012.15460 (2020).

- S. Yan, Z. Wang, Y. Huang, Y. Liu, Z. Liu, F. Yang, W. Lu, D. Li, GGSTrack: Geometric graph with spatio-temporal convolution for multi-object tracking, Neurocomputing, 2025, p. 131234. [CrossRef]

- R. Gao, L. Wang, Memotr: Long-term memory-augmented transformer for multi-object tracking, in: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 9901–9910. [CrossRef]

- R. Luo, Z. Song, L. Ma, J. Wei, W. Yang, M. Yang, Diffusiontrack: Diffusion model for multi-object tracking, in: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 38, 2024, pp. 3991–3999. [CrossRef]

- M. Hu, X. Zhu, H. Wang, S. Cao, C. Liu, Q. Song, Stdformer: Spatial-temporal motion transformer for multiple object tracking, IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 33 (11) (2023) 6571–6594. [CrossRef]

- E. Yu, Z. Li, S. Han, H. Wang, Relationtrack: Relation-aware multiple object tracking with decoupled representation, IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 25 (2022) 2686–2697. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, J. Wu, Y. Fu, Collaborative tracking learning for frame-rate-insensitive multi-object tracking, in: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 9964–9973. [CrossRef]

- D. Chen, H. Shen, Y. Shen, Jdt-nas: Designing efficient multi-object tracking architectures for non-gpu computers, IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 33 (12) (2023) 7541–7553. [CrossRef]

- K. Deng, C. Zhang, Z. Chen, W. Hu, B. Li, F. Lu, Jointing recurrent across-channel and spatial attention for multi-object tracking with block-erasing data augmentation, IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 33 (8) (2023) 4054–4069. [CrossRef]

- Q. Wang, Y. Zheng, P. Pan, Y. Xu, Multiple object tracking with correlation learning, in: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2021, pp. 3876–3886. [CrossRef]

- P. Chu, J. Wang, Q. You, H. Ling, Z. Liu, Transmot: Spatial-temporal graph transformer for multiple object tracking, in: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on applications of computer vision, 2023, pp. 4870–4880. [CrossRef]

- W. Lv, N. Zhang, J. Zhang, D. Zeng, One-shot multiple object tracking with robust id preservation, IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology (2023). [CrossRef]

- J. Seidenschwarz, G. Brasó, V. C. Serrano, I. Elezi, L. Leal-Taixé, Simple cues lead to a strong multi-object tracker, in: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2023, pp. 13813–13823. [CrossRef]

- T. Zhao, G. Yang, Y. Li, M. Lu, and H. Sun, “Multi-object tracking using score-driven hierarchical association strategy between predicted tracklets and objects,” Image and Vision Computing, vol. 152, p. 105303, 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Li, S. Qin, S. Li, Y. Gao, and Y. Wu, “Synergistic-aware cascaded association and trajectory refinement for multi-object tracking,” Image and Vision Computing, p. 105695, 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Psalta, V. Tsironis, and K. Karantzalos, “Transformer-based assignment decision network for multiple object tracking,” Computer Vision and Image Understanding, vol. 241, p. 103957, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y.-F. Li, H.-B. Ji, W.-B. Zhang, and Y.-K. Lai, “Learning discriminative motion models for multiple object tracking,” IEEE Transactions on Multimedia, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Zhou, M. Jiang, and J. Kong, “Bgtracker: cross-task bidirectional guidance strategy for multiple object tracking,” IEEE Transactions on Multimedia, vol. 25, pp. 8132–8144, 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. Kim, G. Jung, and S.-W. Lee, “AM-SORT: adaptable motion predictor with historical trajectory embedding for multi-object tracking,” in Proc. Int. Conf. Pattern Recognition and Artificial Intelligence, pp. 92–107, 2024. [CrossRef]

| Methods | MOT17 | MOT20 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HOTA↑ | MOTA↑ | IDF1↑ | IDS↓ | FPS↑ | HOTA↑ | MOTA↑ | IDF1↑ | IDS↓ | FPS↑ | |

| TADN[44] | - | 69.0% | 60.8% | - | - | - | 68.7% | 61.0% | - | - |

| DMMTracker[45] | 52.1% | 67.1% | 64.3% | 3135 | 16.1 | 48.7% | 62.5% | 60.5% | 2043 | 9.7 |

| TransTrack[26] | 54.1% | 75.2% | 63.5% | 3603 | 10.0 | 48.5% | 65.0% | 59.4% | 3608 | 7.2 |

| TransCenter[7] | 54.5% | 73.2% | 62.2% | 4614 | 1.0 | 43.5% | 61.9% | 50.4% | 4653 | 1.0 |

| MeMOT[27] | 56.9% | 72.5% | 69.0% | 2724 | - | 54.1% | 63.7% | 66.1% | 1938 | - |

| AMtrack[8] | 58.6% | 74.4% | 71.5% | 4740 | - | 56.8% | 73.2% | 69.2% | 1870 | - |

| DNMOT[9] | 58.0% | 75.6% | 68.1% | 2529 | - | 58.6% | 70.5% | 73.2% | 987 | - |

| MeMOTR[31] | 58.8% | 72.8% | 71.5% | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| FairMOT[21] | 59.3% | 73.7% | 72.3% | 3303 | 25.9 | 54.6% | 61.8% | 67.3% | 5243 | 13.2 |

| DiffusionTrack[32] | 60.8% | 77.9% | 73.8% | 3819 | - | 55.3% | 72.8% | 66.3% | 4117 | - |

| STDFormer-LMPH[33] | 60.9% | 78.4% | 73.1% | 5091 | - | 60.2% | 76.2% | 72.1% | 5245 | - |

| RelationTrack[34] | 61.0% | 73.8% | 74.4% | 1374 | 7.4 | 56.5% | 67.2% | 70.5% | 4243 | 2.7 |

| BGTracker[46] | 61.0% | 75.6% | 73.8% | 3735 | 20.7 | 57.5% | 71.6% | 71.8% | 2471 | 12.8 |

| ColTrack[35] | 61.0% | 78.8% | 73.9% | 1881 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| JDT-NAS-T1[36] | - | 74.3% | 72.0% | 2818 | 13.3 | - | - | - | - | - |

| DcMOT[37] | 61.3% | 74.5% | 75.2% | 2682 | 20.4 | 53.8% | 59.7% | 67.4% | 5636 | 10.6 |

| MOTFR[28] | 61.8% | 74.4% | 76.3% | 2652 | 22.2 | 57.2% | 69.0% | 71.7% | 3648 | 13.3 |

| CorrTracker[38] | - | 76.5% | 73.6% | 3369 | 14.8 | - | 65.2% | 69.1% | 5183 | 8.5 |

| TransMOT[39] | - | 76.7% | 75.1% | 2346 | - | - | 77.5% | 75.2% | 1615 | - |

| MAA[29] | 62.0% | 79.4% | 75.9% | 1452 | 189.1 | 57.3% | 73.9% | 71.2% | 1331 | 14.7 |

| MOTRv2[3] | 62.0% | 78.6% | 75.0% | - | - | 61.0% | 76.2% | 73.1% | - | - |

| PID-MOT[40] | 62.1% | 74.7% | 76.3% | 1563 | 19.7 | 57.0% | 67.5% | 71.3% | 1015 | 8.7 |

| GHOST[41] | 62.8% | 78.7% | 77.1% | 2325 | - | 61.2% | 73.7% | 75.2% | 1264 | - |

| GGSTrack[30] | 62.8% | 80.2% | - | 1689 | 58.0 | 61.8% | 75.1% | - | 1498 | 15.3 |

| ScoreMOT[42] | 63.0% | 79.8% | 76.7% | 4007 | 25.6 | 62.3% | 77.7% | 75.6% | 1440 | 16.2 |

| ByteTrack[2] | 63.1% | 80.3% | 77.3% | 2196 | 29.6 | 61.3% | 77.8% | 75.2% | 1223 | 17.5 |

| OC-SORT[14] | 63.2% | 78.0% | 77.5% | 1950 | 29.0 | 62.1% | 75.5% | 75.9% | 913 | 18.7 |

| AM-SORT[47] | 63.3% | 78.0% | 77.8% | - | - | 62.0% | 75.5% | 76.1% | - | - |

| SCTrack[43] | 63.5% | 79.4% | 77.7% | 2022 | - | 61.4% | 75.6% | 76.1% | 837 | - |

| ConfMOT | 64.5% | 80.5% | 79.3% | 1980 | 26.1 | 62.9% | 78.3% | 76.1% | 1359 | 15.2 |

| Tracker | AssA (%)↑ | AssPr (%)↑ | AssRe (%)↑ | DetA (%)↑ | LocA (%)↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ByteTrack [2] | 62.0 | 76.0 | 68.2 | 64.5 | 83.0 |

| OC-SORT [14] | 63.4 | 80.8 | 67.5 | 63.2 | 83.4 |

| ConfMOT (Ours) | 63.8 | 77.9 | 70.0 | 64.9 | 83.4 |

| Tracker | AssA↑ | AssPr↑ | AssRe↑ | DetA↑ | LocA↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ByteTrack[2] | 59.6% | 74.6% | 66.2% | 63.4% | 83.6% |

| OC-SORT[14] | 60.5% | 75.1% | 67.1% | 64.2% | 83.9% |

| ConfMOT | 61.4% | 77.1% | 67.8% | 64.6% | 84.7% |

| KF | DS | CM+CS | HOTA↑ | MOTA↑ | IDF1↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 67.8% | 77.9% | 79.6% | |||

| ✓ | 68.1% | 77.9% | 79.8% | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | 68.3% | 78.0% | 80.2% | |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 68.7% | 78.4% | 80.5% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).