Submitted:

27 October 2025

Posted:

28 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2.1. Anti-Mitochondrial Antibodies (AMA)

2.1.1. Historical Background and Diagnostic Significance

2.1.2. Target Antigens of AMA

2.1.3. Evolution of AMA Detection Methods

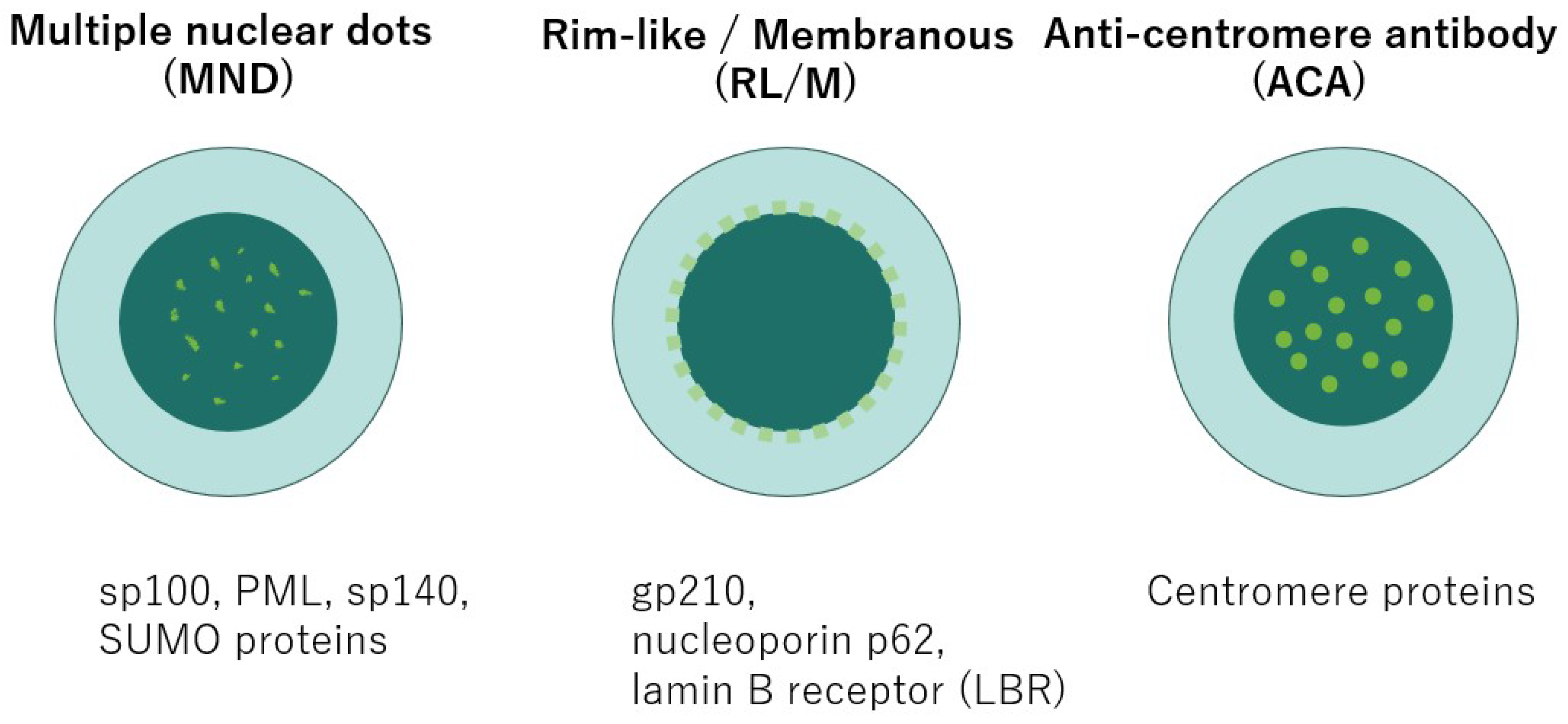

3. Antinuclear Antibodies (ANA) in Primary Biliary Cholangitis

3.1. Basis of ANA Testing

3.2. Frequency and Characteristic ANA Patterns in PBC

3.3. Additional High-Specificity Antibodies

4. Emerging Autoantibodies

4.1. Anti-Kelch-like 12(KLHL12) Antibody

4.2. Anti-RPL30 Antibody

4.3. Anti-HK1 Antibody

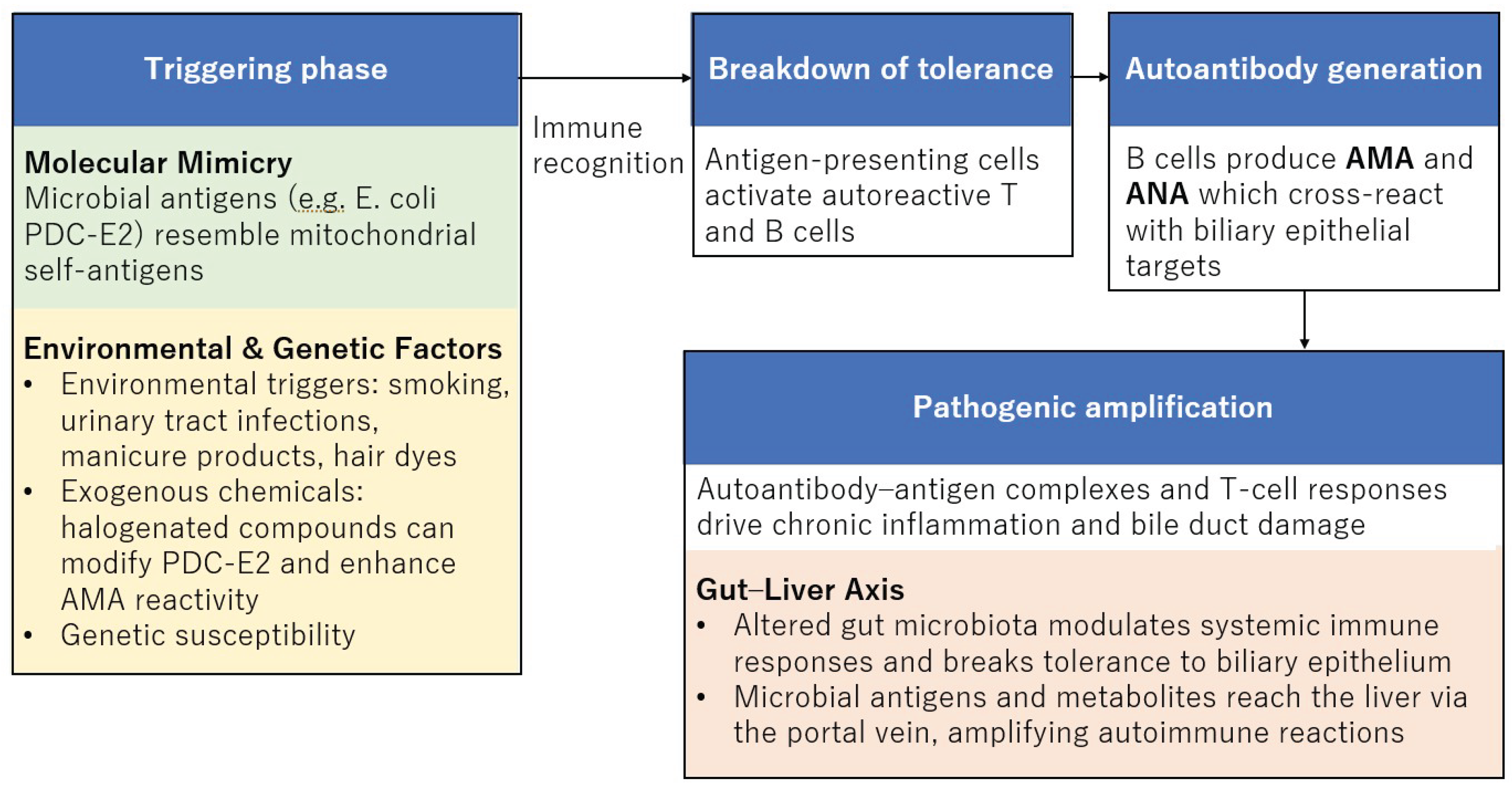

5. Microbial Factors in the Pathogenesis of PBC

5.1. Molecular Mimicry as a Central Hypothesis

5.2. Gut Microbiota and Autoimmune Activation

5.3. Specific Bacterial Antigens and Autoantibody Generation

6. Environmental and Epidemiological Risk Factors

6.1. Exogenous Chemical Modifications of Autoantigens

6.2. Epidemiological Evidence for Environmental and Genetic Susceptibility

7. Autoantigen-Specific Immune Responses in Primary Biliary Cholangitis

7.1. Breakdown of Immune Tolerance and T-Cell Responses

7.2. Link Between Innate Immunity and Autoantibody Induction

7.3. Apoptosis, Antigen Supply, and Disease Progression

8. Diagnostic and Prognostic Significance of Autoantibodies

9. Autoantibodies and Therapeutic Response in Primary Biliary Cholangitis

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hirschfield, G.M.; Beuers, U.; Corpechot, C.; Invernizzi, P.; Jones, D.; Marzioni, M.; Schramm, C. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: The Diagnosis and Management of Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis. J Hepatol 2017, 67, 145–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, T.; Chen, S.; Li, M.; Zhang, D.; Kong, Y.; Jia, J. Regional Variation and Temporal Trend of Primary Biliary Cholangitis Epidemiology: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology (Australia) 2021, 36, 1423–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Zhou, Y.; Haller, I. V.; Romanelli, R.J.; VanWormer, J.J.; Rodriguez, C. V.; Anderson, H.; Boscarino, J.A.; Schmidt, M.A.; Daida, Y.G.; et al. Increasing Prevalence of Primary Biliary Cholangitis and Reduced Mortality With Treatment. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2018, 16, 1342–1350.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murillo Perez, C.F.; Goet, J.C.; Lammers, W.J.; Gulamhusein, A.; van Buuren, H.R.; Ponsioen, C.Y.; Carbone, M.; Mason, A.; Corpechot, C.; Invernizzi, P.; et al. Milder Disease Stage in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis over a 44-Year Period: A Changing Natural History. Hepatology 2018, 67, 1920–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of Cholestatic Liver Diseases. J Hepatol 2009, 51, 237–267. [CrossRef]

- Lindor, K.D.; Bowlus, C.L.; Boyer, J.; Levy, C.; Mayo, M. Primary Biliary Cholangitis: 2018 Practice Guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2019, 69, 394–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, I.R. Primary Biliary Cirrhosis Showing a High Titer of Autoantibody; Report of a Case. N Engl J Med 1958, 258, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.G.; Doniach, D.; Roitt, I.M.; Sherlock, S. SEROLOGICAL TESTS IN DIAGNOSIS OF PRIMARY BILIARY CIRRHOSIS. The Lancet 1965, 285, 827–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, J.; Hough, D.; Maddison, P.J.; McHugh, N.J. The Association of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis and Systemic Sclerosis Is Not Accounted for by Cross Reactivity Between Mitochondrial and Centromere Antigens. J Autoimmun 1994, 7, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergani, D.; Alvarez, F.; Bianchi, F.B.; Cançado, E.L.R.; MacKay, I.R.; Manns, M.P.; Nishioka, M.; Penner, E. Liver Autoimmune Serology: A Consensus Statement from the Committee for Autoimmune Serology of the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group. J Hepatol 2004, 41, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, E.Y.; Liu, M.; Ke, P.F.; Han, G.; Zhang, C.; Deng, L.; Wang, Y.X.; Huang, H.; Huang, W.J.; Liu, R.P.; et al. A Population-Based Characterization Study of Anti-Mitochondrial M2 Antibodies and Its Consistency with Anti-Mitochondrial Antibodies. Lab Med 2023, 54, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, M.; Onji, M. Natural History of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Hepatology Research 2008, 38, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchison, H.C.; Bassendine, M.F.; Hendrick, A.; Bennett, M.K.; Bird, G.; Watson, A.J.; James, O.F.W. Positive Antimitochondrial Antibody but Normal Alkaline Phosphatase: Is This Primary Biliary Cirrhosis? Hepatology 1986, 6, 1279–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Chen, S.; Li, S.; Lv, T.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Ma, H.; Ou, X.; et al. The Future Risk of Primary Biliary Cholangitis (PBC) Is Low among Patients with Incidental Anti-mitochondrial Antibodies but without Baseline PBC. Hepatol Commun 2022, 6, 3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, P.A.; Klein, R. Mitochondrial Antigens and Autoantibodies: From Anti-M1 to Anti-M9. Klin Wochenschr 1986, 64, 897–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.J.; Zhang, F.C.; Li, Y.Z.; Zhang, X. Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: What Do Autoantibodies Tell Us? World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG 2010, 16, 3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gershwin, M.E.; Ansari, A.A.; Mackay, I.R.; Nakanuma, Y.; Nishio, A.; Rowley, M.J.; Coppel, R.L. Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: An Orchestrated Immune Response against Epithelial Cells. Immunol Rev 2000, 174, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynoso-Paz, S.; Leung, P.S.C.; Van De Water, J.; Tanaka, A.; Munoz, S.; Bass, N.; Lindor, K.; Donald, P.J.; Coppel, R.L.; Ansari, A.A.; et al. Evidence for a Locally Driven Mucosal Response and the Presence of Mitochondrial Antigens in Saliva in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Hepatology 2000, 31, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lleo, A.; Maroni, L.; Glaser, S.; Alpini, G.; Marzioni, M. Role of Cholangiocytes in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Semin Liver Dis 2014, 34, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, A.; Leung, P.S.C.; Gershwin, M.E. Evolution of Our Understanding of PBC. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol, 35. [CrossRef]

- Hirschfield, G.M.; Dyson, J.K.; Alexander, G.J.M.; Chapman, M.H.; Collier, J.; Hübscher, S.; Patanwala, I.; Pereira, S.P.; Thain, C.; Thorburn, D.; et al. The British Society of Gastroenterology/UK-PBC Primary Biliary Cholangitis Treatment and Management Guidelines. Gut 2018, 67, 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanos, D.P.; Invernizzi, P.; Mackay, I.R.; Vergani, D. Autoimmune Liver Serology: Current Diagnostic and Clinical Challenges. World J Gastroenterol 2008, 14, 3374–3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ZHANG, L.; WEETMAN, A.P.; JAYNE, D.R.W.; TURNER, I.; YEAMAN, S.J.; BASSENDINE, M.F.; OLIVEIRA, D.B.G. Anti-mitochondrial Antibody IgG Subclass Distribution and Affinity in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Clin Exp Immunol 1992, 88, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dähnrich, C.; Pares, A.; Caballeria, L.; Rosemann, A.; Schlumberger, W.; Probst, C.; Mytilinaiou, M.; Bogdanos, D.; Vergani, D.; Stöcker, W.; et al. New ELISA for Detecting Primary Biliary Cirrhosis-Specific Antimitochondrial Antibodies. Clin Chem 2009, 55, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabeta, S.; Norman, G.L.; Liaskos, C.; Papamichalis, P.A.; Zografos, T.; Garagounis, A.; Rigopoulou, E.I.; Dalekos, G.N. Diagnostic Relevance and Clinical Significance of the New Enhanced Performance M2 (MIT3) ELISA for the Detection of IgA and IgG Antimitochondrial Antibodies in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. J Clin Immunol 2007, 27, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadokawa, Y.; Omagari, K.; Hazama, H.; Ohba, K.; Masuda, J.I.; Kinoshita, H.; Hayashida, K.; Isomoto, H.; Mizuta, Y.; Murase, K.; et al. Evaluation of Newly Developed ELISA Using “MESACUP-2 Test Mitochondrial M2” Kit for the Diagnosis of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Clin Biochem 2003, 36, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogdanos, D.P.; Komorowski, L. Disease-Specific Autoantibodies in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Clinica Chimica Acta 2011, 412, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moteki, S.; Leung, P.S.C.; Coppel, R.L.; Dickson, E.R.; Kaplan, M.M.; Munoz, S.; Gershwin, M.E. Use of a Designer Triple Expression Hybrid Clone for Three Different Lipoyl Domains for the Detection of Antimitochondrial Autoantibodies. Hepatology 1996, 24, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muratori, P.; Muratori, L.; Gershwin, M.E.; Czaja, A.J.; Pappas, G.; Maccariello, S.; Granito, A.; Cassani, F.; Loria, P.; Lenzi, M.; et al. “True” Antimitochondrial Antibody-Negative Primary Biliary Cirrhosis, Low Sensitivity of the Routine Assays, or Both? Clin Exp Immunol 2004, 135, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oertelt, S.; Rieger, R.; Selmi, C.; Invernizzi, P.; Ansari, A.A.; Coppel, R.L.; Podda, M.; Leung, P.S.C.; Gershwin, M.E. A Sensitive Bead Assay for Antimitochondrial Antibodies: Chipping Away at AMA-Negative Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Hepatology 2007, 45, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, M.; Chan, E.K.L.; Sobel, E.S.; Kimpel, D.L.; Yamasaki, Y.; Narain, S.; Mansoor, R.; Reeves, W.H. Clinical Implication of Autoantibodies in Patients with Systemic Rheumatic Diseases. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2007, 3, 721–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.K.L.; Damoiseaux, J.; Carballo, O.G.; Conrad, K.; de Melo Cruvinel, W.; Francescantonio, P.L.C.; Fritzler, M.J.; Garcia-De La Torre, I.; Herold, M.; Mimori, T.; et al. Report of the First International Consensus on Standardized Nomenclature of Antinuclear Antibody HEp-2 Cell Patterns (ICAP) 2014-2015. Front Immunol 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Lv, T.; Li, S.; Chen, S.; Li, B.; Lu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ou, X.; Zhao, X.; You, H.; et al. Patients with AMA/Anti-Sp100/Anti-Gp210 Positivity and Cholestasis Can Manifest Conditions Beyond Primary Biliary Cholangitis. J Clin Transl Hepatol 2025, 13, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigopoulou, E.I.; Dalekos, G.N. Molecular Diagnostics of Primary Billary Cirrhosis. Expert Opin Med Diagn 2008, 2, 621–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granito, A.; Muratori, P.; Quarneti, C.; Pappas, G.; Cicola, R.; Muratori, L. Antinuclear Antibodies as Ancillary Markers in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2012, 12, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Invernizzi, P.; Selmi, C.; Ranftler, C.; Podda, M.; Wesierska-Gadek, J. Antinuclear Antibodies in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Semin Liver Dis 2005, 25, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigopoulou, E.I.; Bogdanos, D.P. Role of Autoantibodies in the Clinical Management of Primary Biliary Cholangitis. World J Gastroenterol 2023, 29, 1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Wang, Q.; Liu, H.; Xu, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Sun, L.; Chen, D.; Huang, C.; Jin, R. Gastroesophageal Varices in Primary Biliary Cholangitis with Anti-Centromere Antibody Positivity: Early Onset? Open Life Sci 2024, 19, 20220979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favoino, E.; Grapsi, E.; Barbuti, G.; Liakouli, V.; Ruscitti, P.; Foti, C.; Giacomelli, R.; Perosa, F. Systemic Sclerosis and Primary Biliary Cholangitis Share an Antibody Population with Identical Specificity. Clin Exp Immunol 2023, 212, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschfield, G.M.; Heathcote, E.J. Antimitochondrial Antibody-Negative Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Clin Liver Dis 2008, 12, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, A.; Habior, A. Detection of Autoantibodies Against Nucleoporin P62 in Sera of Patients With Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Ann Lab Med 2019, 39, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A.; Habior, A.; Gawel, D. Diagnostic and Clinical Value of Specific Autoantibodies against Kelch-like 12 Peptide and Nuclear Envelope Proteins in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, G.L.; Yang, C.Y.; Ostendorff, H.P.; Shums, Z.; Lim, M.J.; Wang, J.; Awad, A.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Milkiewicz, P.; Bloch, D.B.; et al. Anti-Kelch-like 12 and Anti-Hexokinase 1: Novel Autoantibodies in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Liver Int 2014, 35, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Pahuja, K.B.; Wickliffe, K.E.; Gorur, A.; Baumgärtel, C.; Schekman, R.; Rape, M. Ubiquitin-Dependent Regulation of COPII Coat Size and Function. Nature 2012, 482, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondou, P.; Haegeman, G.; Vanhoenacker, P.; Van Craenenbroeck, K. BTB Protein KLHL12 Targets the Dopamine D4 Receptor for Ubiquitination by a Cul3-Based E3 Ligase. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2008, 283, 11083–11096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.A.; Beggs, A.H. Kelch Proteins: Emerging Roles in Skeletal Muscle Development and Diseases. Skelet Muscle 2014, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.J.; Song, G.; Huang, W.; Liu, G.Z.; Deng, C.W.; Zeng, H.P.; Wang, L.; Zhang, F.C.; Zhang, X.; Jeong, J.S.; et al. Identification of New Autoantigens for Primary Biliary Cirrhosis Using Human Proteome Microarrays. Molecular and Cellular Proteomics 2012, 11, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Z.Y.; Huang, Z.X.; Wang, Y.R.; Xie, L.K.; Lin, Y.P.; Liang, Y.; Liu, Z.Y.; Li, D.L.; Zhang, X.Y. Anti-RPL30 as a Novel Biomarker for Enhanced Diagnosis of Autoantibody-Negative Primary Biliary Cholangitis. World J Gastroenterol 2025, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, L.M.; Seixas da Silva, G.S.; Galina, A.; da-Silva, W.S.; Klein, W.L.; Ferreira, S.T.; de Felice, F.G. Amyloid-β Triggers the Release of Neuronal Hexokinase 1 from Mitochondria. PLoS One 2010, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robey, R.B.; Hay, N. Mitochondrial Hexokinases: Guardians of the Mitochondria. Cell Cycle 2005, 4, 654–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, H.; Penner, T.; Mason, A.L. Linking Human Betaretrovirus with Autoimmunity and Liver Disease in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Viruses 2022, 14, 1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selmi, C.; Gershwin, M.E. Bacteria and Human Autoimmunity: The Case of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2004, 16, 406–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, T.; Ebringer, A. Autoimmunity in Rheumatic Diseases Is Induced by Microbial Infections via Crossreactivity or Molecular Mimicry. Autoimmune Dis 2012, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Wei, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, W.; Chen, H.; Wang, Q.; Yang, F.; Miao, Q.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, H.; et al. Gut Microbial Profile Is Altered in Primary Biliary Cholangitis and Partially Restored after UDCA Therapy. Gut 2018, 67, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stemerowicz, R.; Möller, B.; Rodloff, A.; Freudenberg, M.; Hopf, U.; Wittenbrink, C.; Reinhardt, R.; Galanos, C. ARE ANTIMITOCHONDRIAL ANTIBODIES IN PRIMARY BILIARY CIRRHOSIS INDUCED BY R(ROUGH)-MUTANTS OF ENTEROBACTERIACEAE? The Lancet 1988, 332, 1166–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, M.; Kondo, H.; Mori, T.; Komori, A.; Matsuyama, M.; Ito, M.; Takii, Y.; Koyabu, M.; Yokoyama, T.; Migita, K.; et al. Anti-Gp210 and Anti-Centromere Antibodies Are Different Risk Factors for the Progression of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Hepatology 2007, 45, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.J.; Yang, G.X.; Zhang, W.C.; Lu, L.; Tsuneyama, K.; Kronenberg, M.; Véla, J.L.; Lopez-Hoyos, M.; He, X.S.; Ridgway, W.M.; et al. Escherichia Coli Infection Induces Autoimmune Cholangitis and Anti-Mitochondrial Antibodies in Non-Obese Diabetic (NOD).B6 (Idd10/Idd18) Mice. Clin Exp Immunol 2014, 175, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Miao, Q.; Xiao, X.; Wei, Y.; Bian, Z.; Sheng, L.; Chen, X.; et al. The Risk Predictive Values of UK-PBC and GLOBE Scoring System in Chinese Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis: The Additional Effect of Anti-Gp210. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017, 45, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickowitz, R.E.; Worman, H.J. Autoantibodies from Patients with Primary Biliary Cirrhosis Recognize a Restricted Region within the Cytoplasmic Tail of Nuclear Pore Membrane Glycoprotein Gp210. J Exp Med 1993, 178, 2237–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, M.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, L.; Tian, W.; Gong, Y.; Chen, S.; Yang, C.; Xu, P.; et al. Autoantibodes to GP210 Are a Metric for UDCA Responses in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. J Transl Autoimmun 2024, 8, 100239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, M.M.; Gershwin, M.E. Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 2005, 353, 1261–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, K.; Ohfuji, S.; Abe, M.; Komori, A.; Takahashi, A.; Fujii, H.; Kawata, K.; Noritake, H.; Tadokoro, T.; Honda, A.; et al. Environmental Factors, Medical and Family History, and Comorbidities Associated with Primary Biliary Cholangitis in Japan: A Multicenter Case–Control Study. J Gastroenterol 2022, 57, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selmi, C.; Balkwill, D.L.; Invernizzi, P.; Ansari, A.A.; Coppel, R.L.; Podda, M.; Leung, P.S.; Kenny, T.P.; Van De Water, J.; Nantz, M.H.; et al. Patients With Primary Biliary Cirrhosis React Against a Ubiquitous Xenobiotic-Metabolizing Bacterium. Hepatology 2003, 38, 1250–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, S.A.; Quan, C.; Van de Water, J.; Nantz, M.H.; Kurth, M.J.; Barsky, D.; Colvin, M.E.; Lam, K.S.; Coppel, R.L.; Ansari, A.; et al. Immunoreactivity of Organic Mimeotopes of the E2 Component of Pyruvate Dehydrogenase: Connecting Xenobiotics with Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. The Journal of Immunology 2001, 167, 2956–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howel, D.; Fischbacher, C.M.; Bhopal, R.S.; Gray, J.; Metcalf, J. V.; James, O.F.W. An Exploratory Population-Based Case-Control Study of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Hepatology 2000, 31, 1055–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prince, M.I.; Ducker, S.J.; James, O.F.W. Case-Control Studies of Risk Factors for Primary Biliary Cirrhosis in Two United Kingdom Populations. Gut 2010, 59, 508–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaridis, K.N.; Juran, B.D.; Boe, G.M.; Slusser, J.P.; De Andrade, M.; Homburger, H.A.; Ghosh, K.; Dickson, E.R.; Lindor, K.D.; Petersen, G.M. Increased Prevalence of Antimitochondrial Antibodies in First-Degree Relatives of Patients with Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Hepatology 2007, 46, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, K.M.; Nelson, J.L. Microchimerism: An Investigative Frontier in Autoimmunity and Transplantation. JAMA 2004, 291, 1127–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wei, S.; Chen, L.; Zhou, X.; Ma, X. Primary Biliary Cholangitis: Molecular Pathogenesis Perspectives and Therapeutic Potential of Natural Products. Front Immunol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assassi, S.; Fritzler, M.J.; Arnett, F.C.; Norman, G.L.; Shah, K.R.; Gourh, P.; Manek, N.; Perry, M.; Ganesh, D.; Rahbar, M.H.; et al. Primary Biliary Cirrhosis (PBC), PBC Autoantibodies, and Hepatic Parameter Abnormalities in a Large Population of Systemic Sclerosis Patients. J Rheumatol 2009, 36, 2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimoto, S.; Ishikawa, O.; Muro, Y.; Takagi, H.; Tamura, T.; Miyachi, Y. Clinical and Immunological Characterization of Patients with Systemic Sclerosis Overlapping Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: A Comparison with Patients with Systemic Sclerosis Alone. Journal of Dermatology 1999, 26, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kita, H.; Matsumura, S.; He, X.S.; Ansari, A.A.; Lian, Z.X.; Van de Water, J.; Coppel, R.L.; Kaplan, M.M.; Gershwin, M.E. Analysis of TCR Antagonism and Molecular Mimicry of an HLA-A*0201-Restricted CTL Epitope in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Hepatology 2002, 36, 918–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavazzana, I.; Ceribelli, A.; Taraborelli, M.; Fredi, M.; Norman, G.; Tincani, A.; Satoh, M.; Franceschini, F. Primary Biliary Cirrhosis-Related Autoantibodies in a Large Cohort of Italian Patients with Systemic Sclerosis. Journal of Rheumatology 2011, 38, 2180–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumagi, T.; Heathcote, E.J. Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2008, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, A.; Nezu, S.; Uegaki, S.; Mikami, M.; Okuyama, S.; Kawamura, N.; Aiso, M.; Gershwin, M.E.; Takahashi, S.I.; Selmi, C.; et al. The Clinical Significance of IgA Antimitochondrial Antibodies in Sera and Saliva in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2007, 1107, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, S.; Van De Water, J.; Leung, P.; Odin, J.A.; Yamamoto, K.; Gores, G.J.; Mostov, K.; Ansari, A.A.; Coppel, R.L.; Shiratori, Y.; et al. Caspase Induction by IgA Antimitochondrial Antibody: IgA-Mediated Biliary Injury in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Hepatology 2004, 39, 1415–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joplin, R.; Wallace, L.L.; Johnson, G.D.; Lindsay, J.G.; Yeaman, S.J.; Palmer, J.M.; Strain, A.J.; Neuberger, J.M. Subcellular Localization of Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Dihydrolipoamide Acetyltransferase in Human Intrahepatic Biliary Epithelial Cells. J Pathol 1995, 176, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, G.; Zhong, R.; Lleo, A.; Leung, P.S.C.; Bowlus, C.L.; Yang, G.-X.; Yang, C.-Y.; Coppel, R.L.; Ansari, A.A.; Cuebas, D.A.; et al. AUTOIMMUNE, CHOLESTATIC AND BILIARY DISEASE Epithelial Cell Specificity and Apotope Recognition by Serum Autoantibodies in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odin, J.A.; Huebert, R.C.; Casciola-Rosen, L.; LaRusso, N.F.; Rosen, A. Bcl-2-Dependent Oxidation of Pyruvate Dehydrogenase-E2, a Primary Biliary Cirrhosis Autoantigen, during Apoptosis. J Clin Invest 2001, 108, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allina, J.; Stanca, C.M.; Garber, J.; Hu, B.; Sautes-Fridman, C.; Bach, N.; Odin, J.A. Anti-CD16 Autoantibodies and Delayed Phagocytosis of Apoptotic Cells in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. J Autoimmun 2008, 30, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, C.P.; Stein, G.M.; Keppeler, H.; Gregor, M.; Wesselborg, S.; Lauber, K. Apoptosis-Associated Antigens Recognized by Autoantibodies in Patients with the Autoimmune Liver Disease Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Apoptosis 2008, 13, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimoda, S.; Miyakawa, H.; Nakamura, M.; Ishibashi, H.; Kikuchi, K.; Kita, H.; Niiro, H.; Arinobu, Y.; Ono, N.; Mackay, I.R.; et al. CD4 T-Cell Autoreactivity to the Mitochondrial Autoantigen PDC-E2 in AMA-Negative Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. J Autoimmun 2008, 31, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, M.; Takii, Y.; Ito, M.; Komori, A.; Yokoyama, T.; Shimizu-Yoshida, Y.; Koyabu, M.; Matsuyama, M.; Mori, T.; Kamihira, T.; et al. Increased Expression of Nuclear Envelope Gp210 Antigen in Small Bile Ducts in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. J Autoimmun 2006, 26, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, M.; Miyakoshi, M.; Sato, Y.; Nakanuma, Y. Increased Expression of Mitochondrial Proteins Associated with Autophagy in Biliary Epithelial Lesions in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Liver International 2013, 33, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesierska-Gadek, J.; Penner, E.; Battezzati, P.M.; Selmi, C.; Zuin, M.; Hitchman, E.; Worman, H.J.; Gershwin, M.E.; Podda, M.; Invernizzi, P. Correlation of Initial Autoantibody Profile and Clinical Outcome in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Hepatology 2006, 43, 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Ren, L.; Li, Y.; Xu, T.; Li, W.; Gao, W.; Sun, G.; Liu, M. Clinical Performance of AMA-M2, Anti-gp210 and Anti-sp100 Antibody Levels in Primary Biliary Cholangitis: When Detected by Multiplex Bead-based Flow Fluorescent Immunoassay. Immun Inflamm Dis 2024, 12, e1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Han, W.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Duan, Z. Early Prognostic Utility of Gp210 Antibody-Positive Rate in Primary Biliary Cholangitis: A Meta-Analysis. Dis Markers 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, D.; Janmohamed, A.; Plant, T.; Davidson, M.; Norman, H.; Russell, E.; Serevina, O.; Chung, K.; Qamar, K.; Gunson, B.; et al. Antibodies to Gp210 and Understanding Risk in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Liver International 2021, 41, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, M.; Shimizu-Yoshida, Y.; Takii, Y.; Komori, A.; Yokoyama, T.; Ueki, T.; Daikoku, M.; Yano, K.; Matsumoto, T.; Migita, K.; et al. Antibody Titer to Gp210-C Terminal Peptide as a Clinical Parameter for Monitoring Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2005, 42, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muratori, P.; Muratori, L.; Ferrari, R.; Cassani, F.; Bianchi, G.; Lenzi, M.; Rodrigo, L.; Linares, A.; Fuentes, D.; Bianchi, F.B. Characterization and Clinical Impact of Antinuclear Antibodies in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2003, 98, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muratori, P.; Muratori, L.; Cassani, F.; Terlizzi, P.; Lenzi, M.; Rodrigo, L.; Bianchi, F.B. Anti-Multiple Nuclear Dots (Anti-MND) and Anti-SP100 Antibodies in Hepatic and Rheumatological Disorders. Clin Exp Immunol 2002, 127, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Züchner, D.; Sternsdorf, T.; Szostecki, C.; Heathcote, E.J.; Cauch-Dudek, K.; Will, H. Prevalence, Kinetics, and Therapeutic Modulation of Autoantibodies against Sp100 and Promyelocytic Leukemia Protein in a Large Cohort of Patients with Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Hepatology 1997, 26, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Himoto, T.; Yamamoto, S.; Morimoto, K.; Tada, S.; Mimura, S.; Fujita, K.; Tani, J.; Morishita, A.; Masaki, T. Clinical Impact of Antibodies to Sp100 on a Bacterial Infection in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis. J Clin Lab Anal 2021, 35, e24040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Norstrand, M.D.; Malinchoc, M.; Lindor, K.D.; Therneau, T.M.; Gershwin, M.E.; Leung, P.S.C.; Dickson, E.R.; Homburger, H.A. Quantitative Measurement of Autoantibodies to Recombinant Mitochondrial Antigens in Patients with Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: Relationship of Levels of Autoantibodies to Disease Progression. Hepatology 1997, 25, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.A.; Jeong, S.H. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Korean J Hepatol 2011, 17, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuschner, U. Primary Biliary Cirrhosis—Presentation and Diagnosis. Clin Liver Dis 2003, 7, 741–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigopoulou, E.I.; Davies, E.T.; Bogdanos, D.P.; Liaskos, C.; Mytilinaiou, M.; Koukoulis, G.K.; Dalekos, G.N.; Vergani, D. Antimitochondrial Antibodies of Immunoglobulin G3 Subclass Are Associated with a More Severe Disease Course in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Liver International 2007, 27, 1226–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Invernizzi, P.; Crosignani, A.; Battezzati, P.M.; Covini, G.; De Valle, G.; Larchi, A.; Zuin, M.; Podda, M. Comparison of the Clinical Features and Clinical Course of Antimitochondrial Antibody-Positive and -Negative Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Hepatology 1997, 25, 1090–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliusson, G.; Imam, M.; Björnsson, E.S.; Talwalkar, J.A.; Lindor, K.D. Long-Term Outcomes in Antimitochondrial Antibody Negative Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Scand J Gastroenterol 2016, 51, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Zhong, R.; He, X.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Hou, J. Evidence for the Association between IgG-Antimitochondrial Antibody and Biochemical Response to Ursodeoxycholic Acid Treatment in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017, 32, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kisand, K.E.; Karvonen, A.L.; Vuoristo, M.; Färkkilä, M.; Lehtola, J.; Inkovaara, J.; Miettinen, T.; Krohn, K.; Uibo, R. Ursodeoxycholic Acid Treatment Lowers the Serum Level of Antibodies against Pyruvate Dehydrogenase and Influences Their Inhibitory Capacity for the Enzyme Complex in Patients with Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. J Mol Med 1996, 74, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, G.D.; Kikuchi, K.; Miyakawa, H.; Tanaka, A.; Watnik, M.R.; Gershwin, M.E. Serial Analysis of Antimitochondrial Antibody in Patients with Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Clin Dev Immunol 2004, 11, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikuchi, K.; Hsu, W.; Hosoya, N.; Moritoki, Y.; Kajiyama, Y.; Kawai, T.; Takai, A.; Hayami, E.; Selmi, C.; Gershwin, M.E.; et al. Ursodeoxycholic Acid Reduces CpG-Induced IgM Production in Patients with Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Hepatology Research 2009, 39, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tana, M.M.; Shums, Z.; Milo, J.; Norman, G.L.; Leung, P.S.; Gershwin, M.E.; Noureddin, M.; Kleiner, D.E.; Zhao, X.; Heller, T.; et al. The Significance of Autoantibody Changes Over Time in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Am J Clin Pathol 2015, 144, 601–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, M.; Kondo, H.; Tanaka, A.; Komori, A.; Ito, M.; Yamamoto, K.; Ohira, H.; Zeniya, M.; Hashimoto, E.; Honda, M.; et al. Autoantibody Status and Histological Variables Influence Biochemical Response to Treatment and Long-Term Outcomes in Japanese Patients with Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Hepatol Res 2015, 45, 846–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatselis, N.K.; Zachou, K.; Norman, G.L.; Gabeta, S.; Papamichalis, P.; Koukoulis, G.K.; Dalekos, G.N. Clinical Significance of the Fluctuation of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis-Related Autoantibodies during the Course of the Disease. Autoimmunity 2013, 46, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kugiyama, Y.; Abe, M.; Namisaki, T.; Yoshiji, H.; Abe, K.; Ohira, H.; Shirahashi, R.; Yokoyama, K.; Fukunaga, A.; Kawata, K.; et al. Clinical Characteristics and Long-Term Prognosis of Primary Biliary Cholangitis in Japan: Results of the 2nd-Generation Nationwide Survey. Hepatol Res 2025. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Autoantibody | Prevalence in PBC | Key prognostic / disease progression associations | References |

| AMA | 90-95% [1,9,10] | Diagnostic hallmark | [8] |

| Present years before symptoms/biochemical abnormalities | [12] | ||

| Titer not clearly predictive of prognosis | [94] | ||

| IgG3 AMA associated with advanced histology and higher cirrhosis frequency; correlates with Mayo risk score | [97] | ||

| Anti-gp210 (ANA, RL/M pattern) | 30-50% [28,29] | Strong predictor of poor prognosis: higher risk of cirrhosis, severe cholestasis, hepatic failure, and mortality | [85,86,87,88] |

| 20% of anti-gp210–positive patients lose their seroreactivity under UDCA therapy | [56,60,105] | ||

| Persistence of anti-gp210 or high gp210 expression in bile ducts associated with end-stage liver failure | [83,89] | ||

| Anti-sp100 (ANA, MND pattern) | 8.7-40.0% [90,91,92] |

No significant difference in the frequency of anti-sp100 was observed between AMA-positive and AMA-negative PBC patients | [90,91,92,93] |

| Anti-centromere antibody (ACA) | 10–30% [38] | Not PBC-specific; associated with Raynaud’s phenomenon, sicca symptoms, and overlap with systemic sclerosis | [38,39] |

| Correlated with improvement of the Mayo risk score (p = 0.025) and with a favorable response to UDCA | [106] | ||

| Anti-p62 (ANA, RL/M subtype) | detected infrequently [41] | Highly specific; useful in AMA-negative PBC; diagnostic adjunct; prognostic role not yet fully established | [41] |

| Anti-LBR (ANA) | 15% [41,42] | Highly specific for PBC; associated with liver fibrosis but not with overall survival | [41] |

| Anti-KLHL12 | 40% [43] | Associated with higher bilirubin, fibrosis; suggested as a risk factor for poor prognosis | [42,43] |

| Anti-RPL30 | Correlates with INR and MELD score; potential marker of disease severity | [33,48] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).