1. The Necessity of Regenerative Medicine

Since the discovery of the germ theory in the 19th century, infectious diseases have been pushed back in large parts of the world through hygiene, vaccination, and antibiotics. However, infectious diseases have now been replaced by non-communicable diseases (NCDs) — such as diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases, cancer, chronic inflammatory conditions, and neurodegenerative disorders.[

1] These chronic diseases no longer affect people only in old age but are increasingly appearing earlier in life.[

2] We are standing at a societal tipping point: NCDs have contributed to the fact that, after decades of continuous increase, life expectancy in highly developed countries is now stagnating or even declining.[

3] At the same time, data show that factors such as cognitive performance are also decreasing — a phenomenon described as the reverse Flynn effect.[

4]

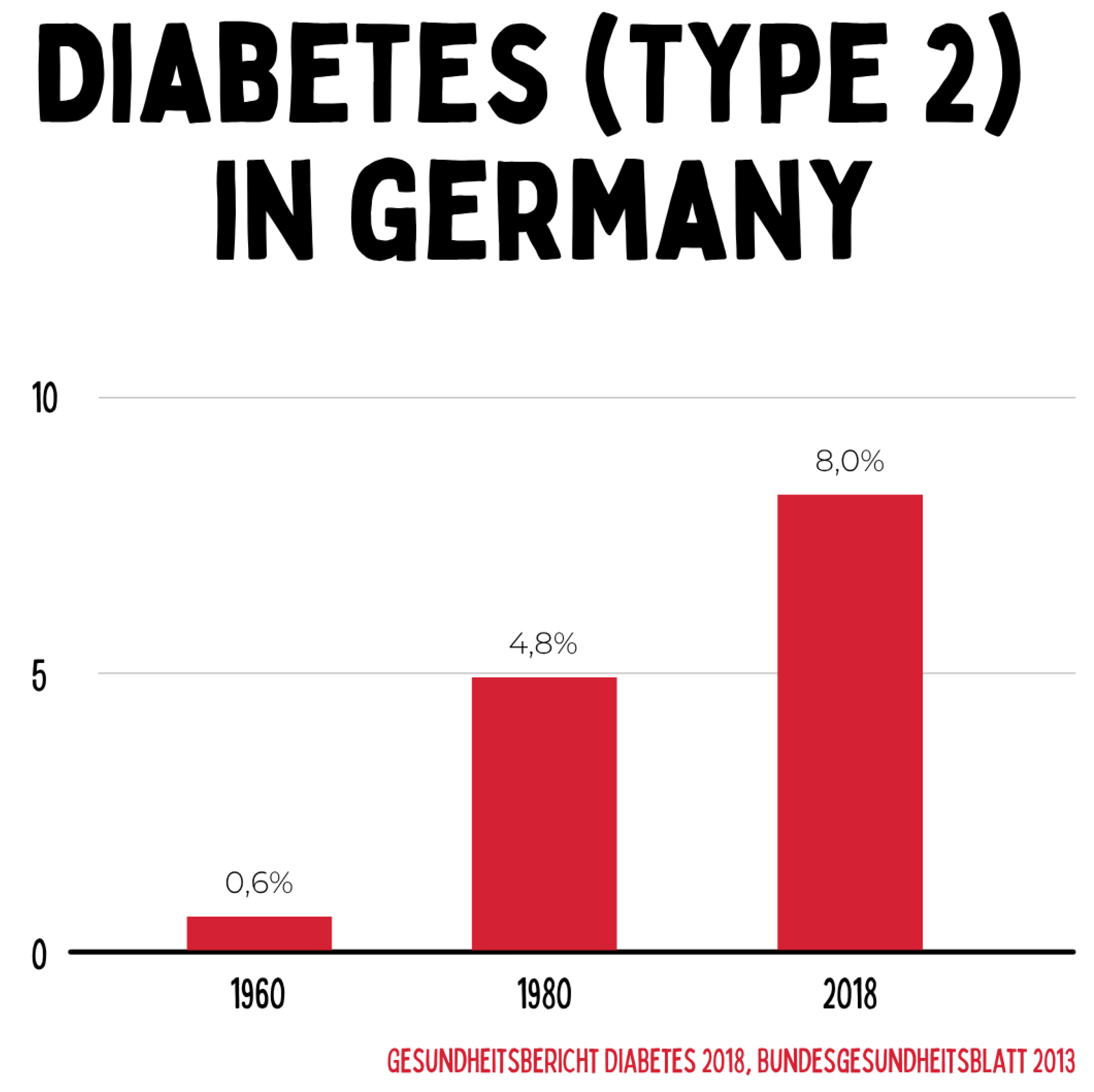

Figure 1.

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes in Germany rose from 0.6 % in 1960 to 8.0 % in 2018. This increase reflects profound changes in diet, physical activity, and metabolic health, documenting the transition to a chronic widespread disease with a high socioeconomic burden. The data clearly demonstrate that conventional acute medicine is insufficient to sustainably address this dynamic.

Figure 1.

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes in Germany rose from 0.6 % in 1960 to 8.0 % in 2018. This increase reflects profound changes in diet, physical activity, and metabolic health, documenting the transition to a chronic widespread disease with a high socioeconomic burden. The data clearly demonstrate that conventional acute medicine is insufficient to sustainably address this dynamic.

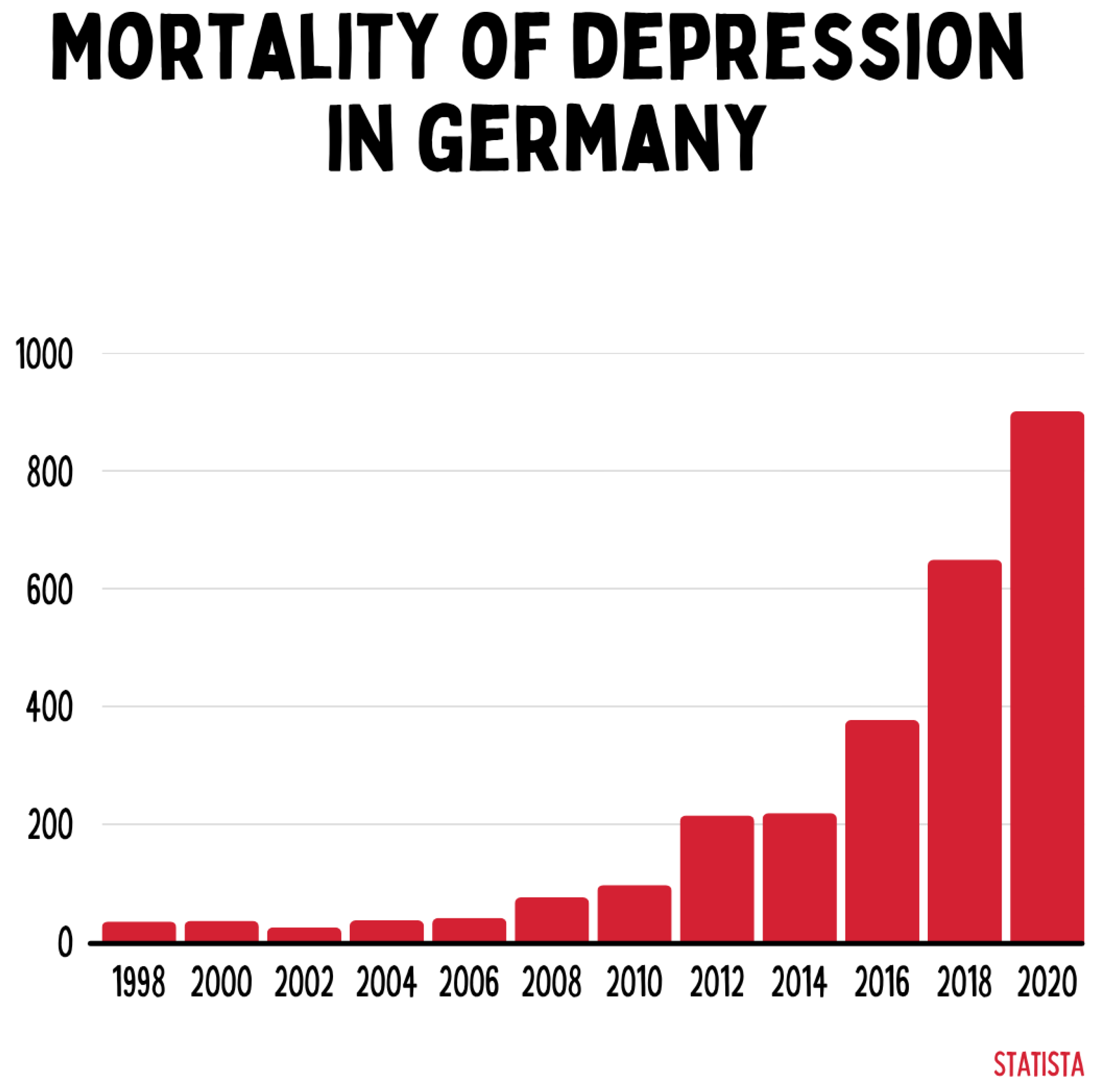

Figure 2.

Mortality associated with depressive disorders has increased exponentially in Germany since 1998, reaching over 900 cases in 2020. This highlights the growing importance of mental illness as a determinant of public health and simultaneously exposes deficits in existing healthcare systems, which are primarily oriented toward acute interventions rather than chronic processes.

Figure 2.

Mortality associated with depressive disorders has increased exponentially in Germany since 1998, reaching over 900 cases in 2020. This highlights the growing importance of mental illness as a determinant of public health and simultaneously exposes deficits in existing healthcare systems, which are primarily oriented toward acute interventions rather than chronic processes.

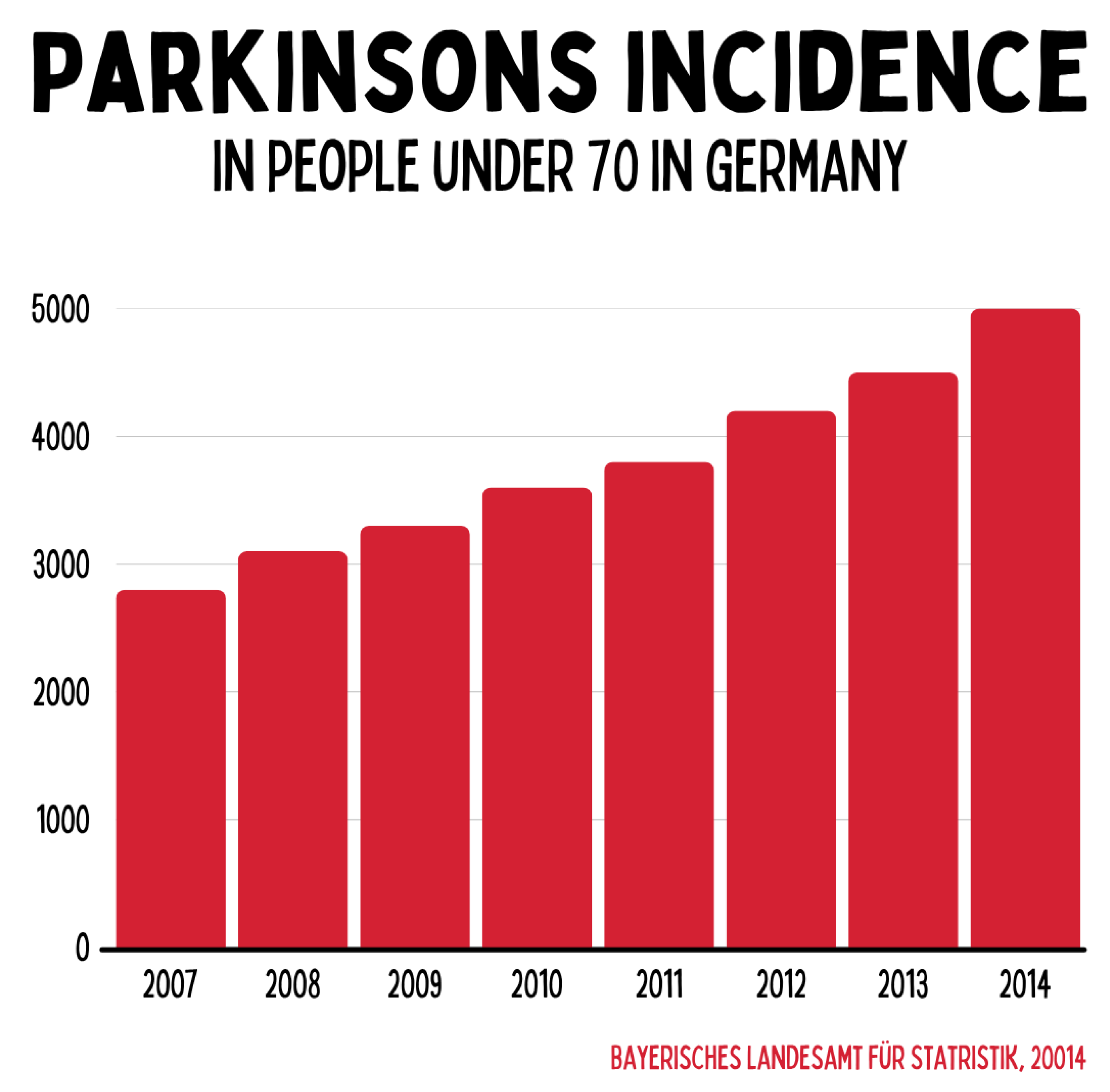

Figure 3.

Between 2007 and 2014, the number of Parkinson’s diagnoses among people under the age of 70 in Germany increased from around 2,800 to approximately 5,000. This underscores that neurodegenerative diseases do not occur exclusively in old age but increasingly affect younger populations. The trend illustrates the growing need for early preventive and regenerative therapeutic strategies.

Figure 3.

Between 2007 and 2014, the number of Parkinson’s diagnoses among people under the age of 70 in Germany increased from around 2,800 to approximately 5,000. This underscores that neurodegenerative diseases do not occur exclusively in old age but increasingly affect younger populations. The trend illustrates the growing need for early preventive and regenerative therapeutic strategies.

Contemporary medicine has not yet found adequate answers to this pandemic of chronic disease.[

5] However, this is not because medicine fails to address illness — on the contrary, acute medicine is highly effective in treating infectious and acute conditions. Rather, it is philosophically, conceptually, and methodologically not designed to capture and treat the distinctive nature of chronic disease.[

6,

7,

8] The old genetic paradigm of chronic disease is outdated, as 80–90% of the etiology of chronic illness is attributable to non-genetic factors.[

9]

Chronic disease processes do not arise from a single pathogen, a monogenetic cause, or a single defect, but from long-term biological adaptation processes that evolve over years or even decades. For this kind of health and disease, acute medicine lacks satisfactory approaches that truly lead to lasting chronic health.[

10,

11,

12]

4. The Core Theses of Regenerative Medicine

Regenerative medicine begins precisely at this point. It integrates germ theory and terrain theory in an evidence-based manner, yet goes beyond both by focusing specifically on chronic processes. Its subject is the science of biological adaptation, mitohormesis, epigenetic memory formation (chronicity), resilience, and antifragility,[

21,

22,

23,

24,

25] as well as their practical translation into therapeutic application. In this paradigm, health is no longer understood mechanistically as the mere absence of disease but as the dynamic ability of an organism to continuously adapt and grow through challenge (“health is adaptability”).[

26,

27]

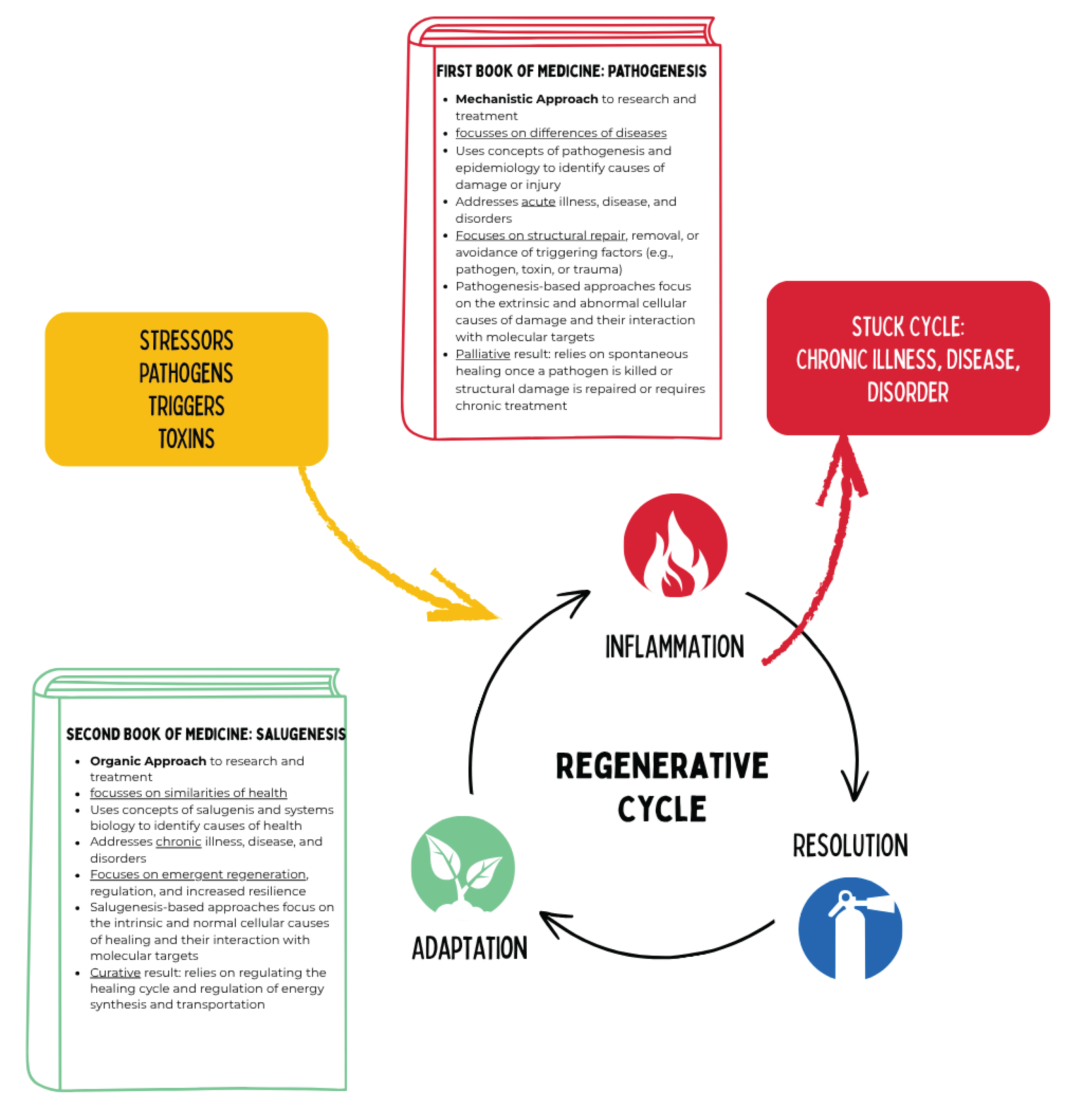

Thus, regenerative medicine consciously and deliberately steps out of the footsteps of René Descartes and the mechanistic paradigm of acute medicine, opening a new, organic paradigm of medicine — the “second book of medicine” — as a complementary approach alongside the still valued and necessary acute medicine. Regenerative medicine does not view the body primarily as a machine that must be repaired but as a living, adaptive system that can be guided into chronic health through targeted regulation within a network of stress and regeneration.[

28]

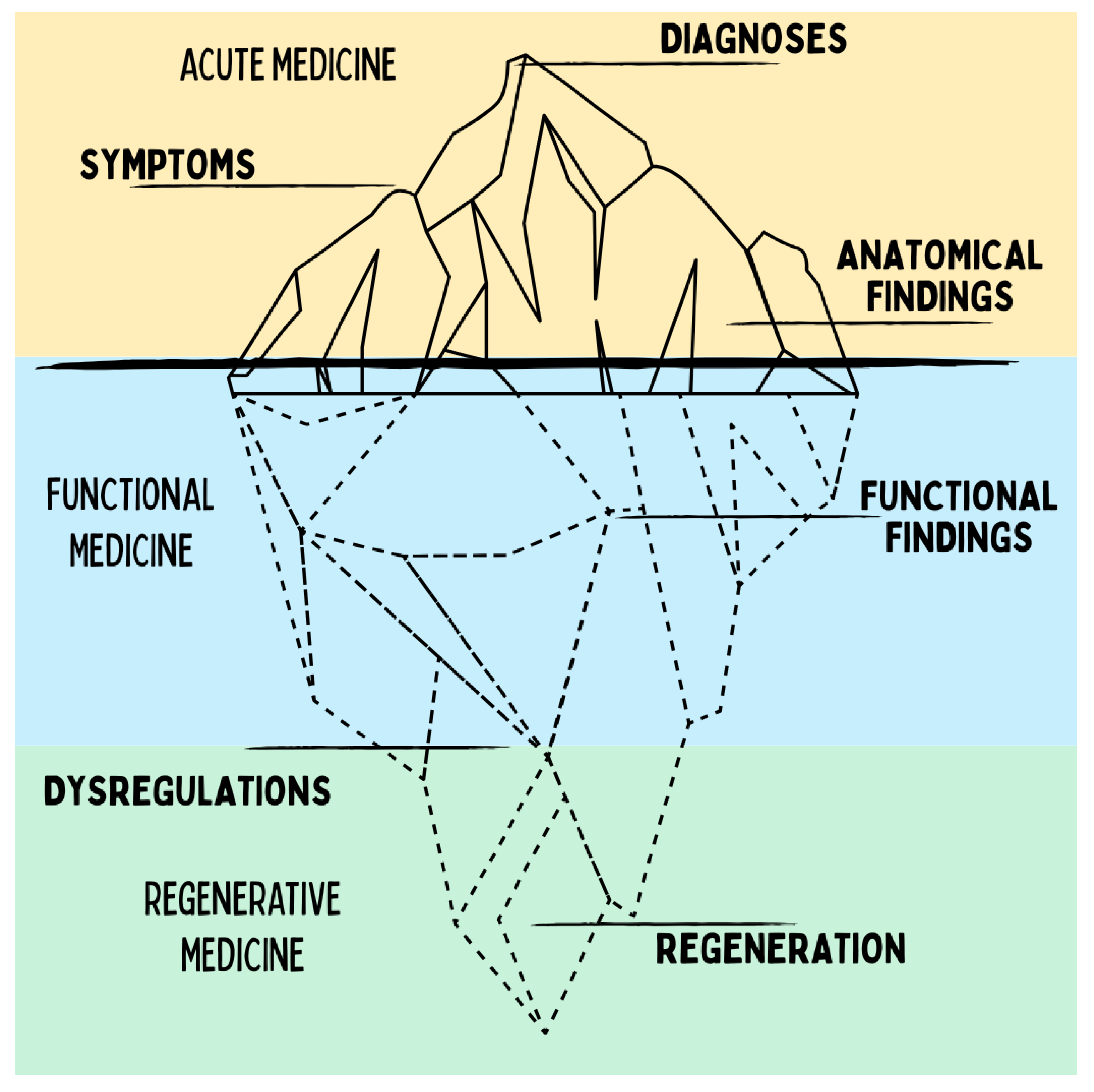

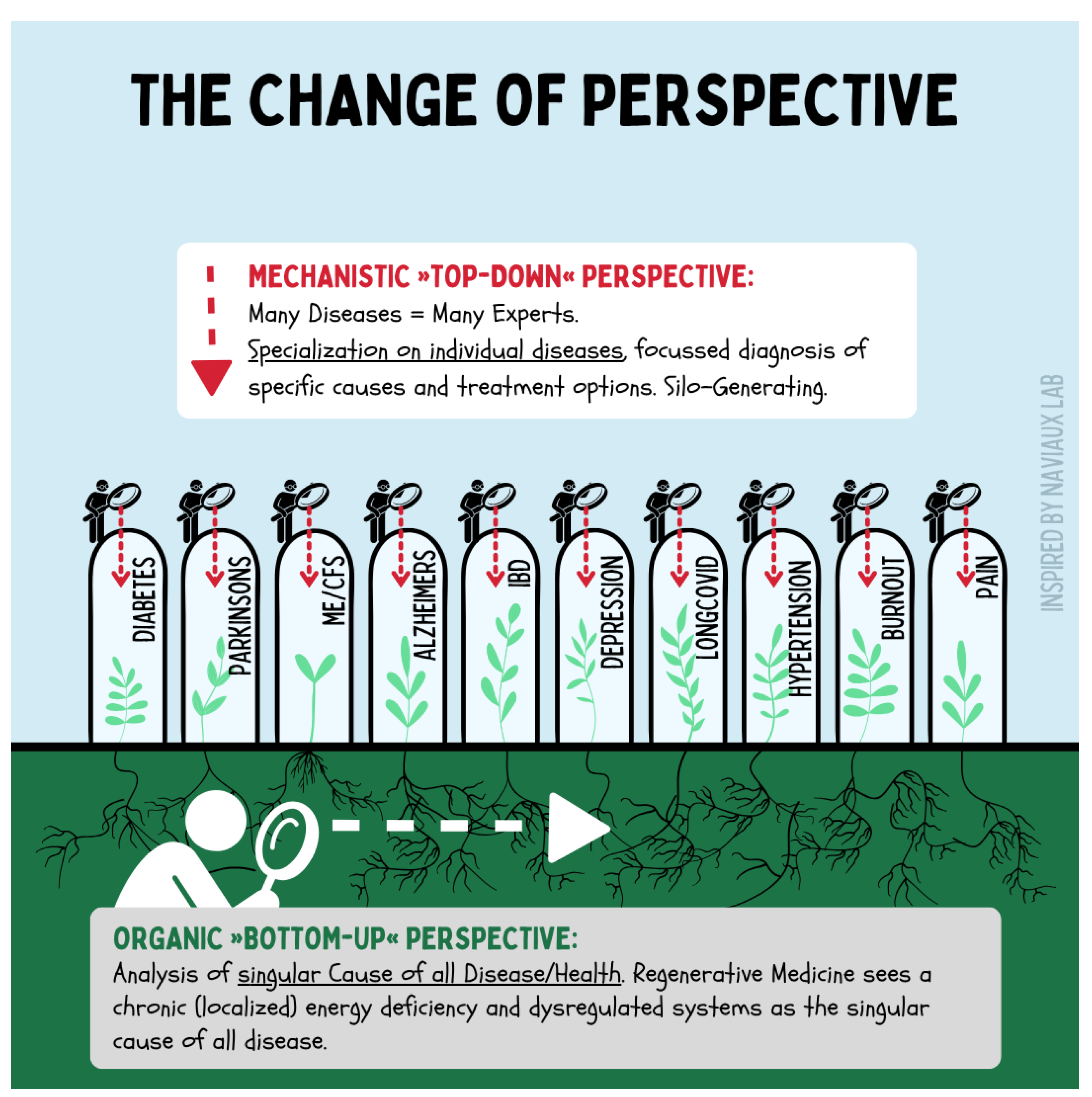

Figure 5.

The diagram illustrates the paradigm shift from a classical top-down perspective of medicine, which views diseases in isolation and treats them within specialized silos, toward a bottom-up perspective. Regenerative medicine does not primarily investigate individual diagnoses but rather the common roots of chronic diseases: dysfunctional regulatory systems and disrupted regenerative cycles. This shifts the focus toward understanding systemic interconnections, enabling new integrative therapeutic approaches.

Figure 5.

The diagram illustrates the paradigm shift from a classical top-down perspective of medicine, which views diseases in isolation and treats them within specialized silos, toward a bottom-up perspective. Regenerative medicine does not primarily investigate individual diagnoses but rather the common roots of chronic diseases: dysfunctional regulatory systems and disrupted regenerative cycles. This shifts the focus toward understanding systemic interconnections, enabling new integrative therapeutic approaches.

This foundational paper formulates fourteen core theses outlining the scientific principles of regenerative medicine. Central to these is the understanding that the organism’s regenerative capacity is primarily determined by mitochondrial energy availability, which can be modulated through adaptive mitohormesis. A dynamic balance between challenge and resources directs cellular metabolism toward regeneration, whereas imbalance leads to degeneration. In the sense of a decentralized bottom-up process, both degenerative and regenerative changes propagate from the mitochondrial level through the cellular, tissue, organ, organ system, and organismal levels. What begins as a mitochondrial degeneration/regeneration switch manifests physiologically, epigenetically, and anatomically as processes of degeneration or regeneration.[

29,

30,

31,

32]

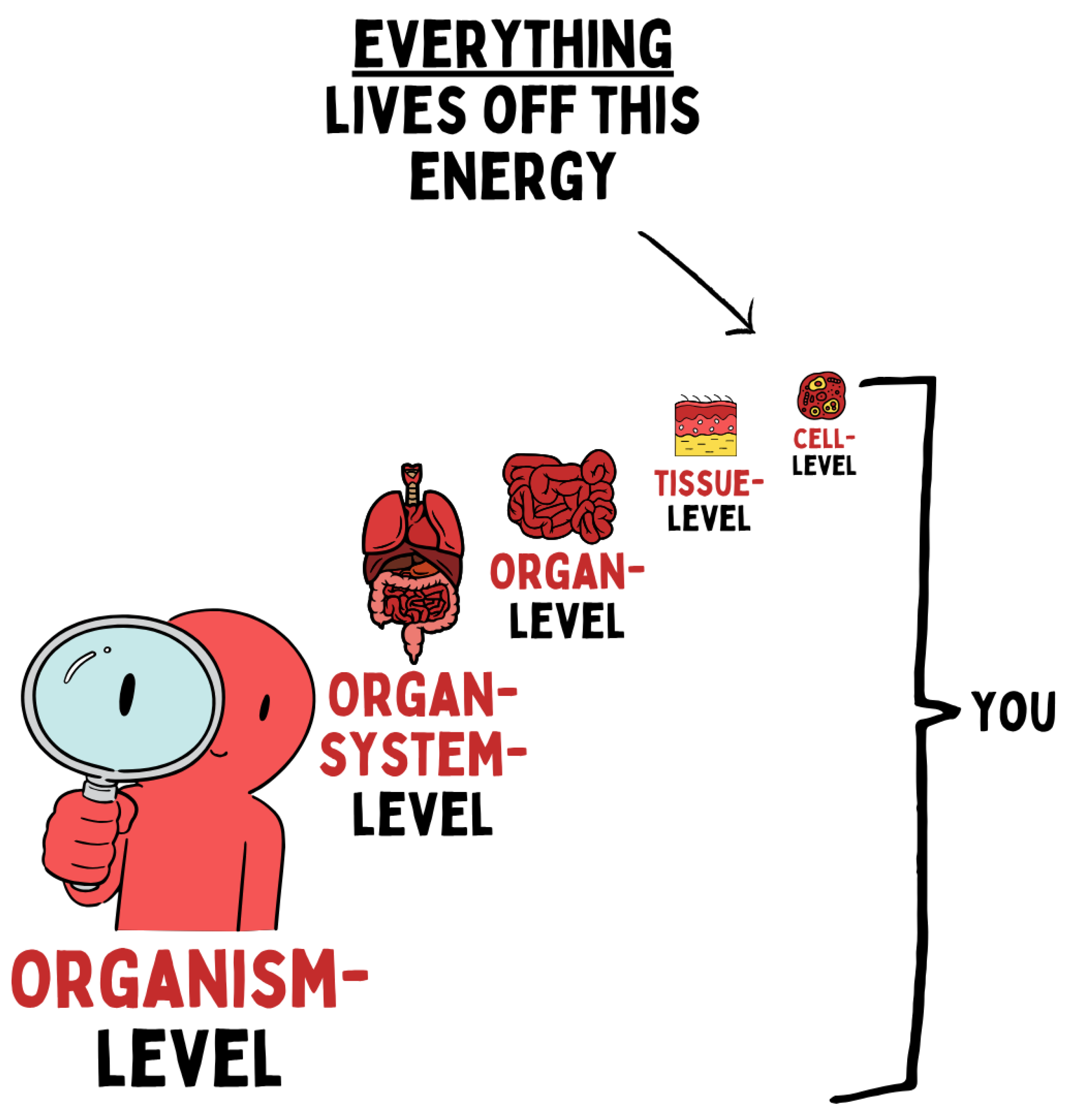

Figure 6.

Biological energy supply forms the fundamental basis of all life processes. It determines function at every level of organization — from the cell to tissues and organs up to organ systems and the entire organism. Disturbances in cellular energy metabolism therefore have systemic effects and shape both health and disease.

Figure 6.

Biological energy supply forms the fundamental basis of all life processes. It determines function at every level of organization — from the cell to tissues and organs up to organ systems and the entire organism. Disturbances in cellular energy metabolism therefore have systemic effects and shape both health and disease.

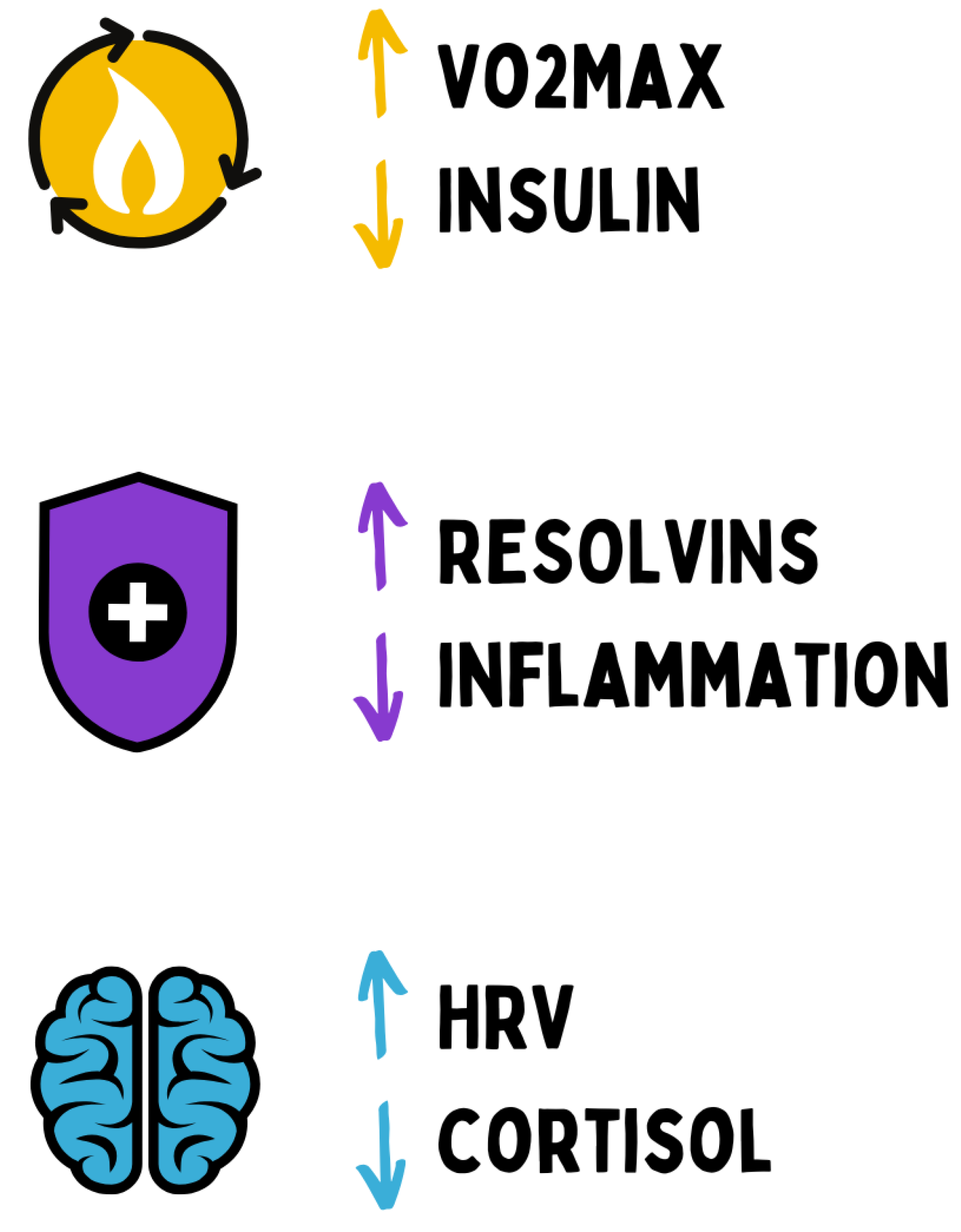

The nervous, immune, and metabolic systems act as interconnected regulators of energy allocation, and allostasis — the ability to maintain stability through change — emerges as a hallmark of health and adaptability. Objective markers such as VO

2max, insulin sensitivity, inflammatory and resolution mediators (e.g., hsCRP and resolvins), heart rate variability, and cortisol diurnal rhythm reflect the state of adaptive equilibrium. Long-term regulatory patterns are also “stored” via epigenetic imprinting at the cellular level and can thereby consolidate chronically health-promoting or disease-prone profiles.[

33,

34,

35,

36]

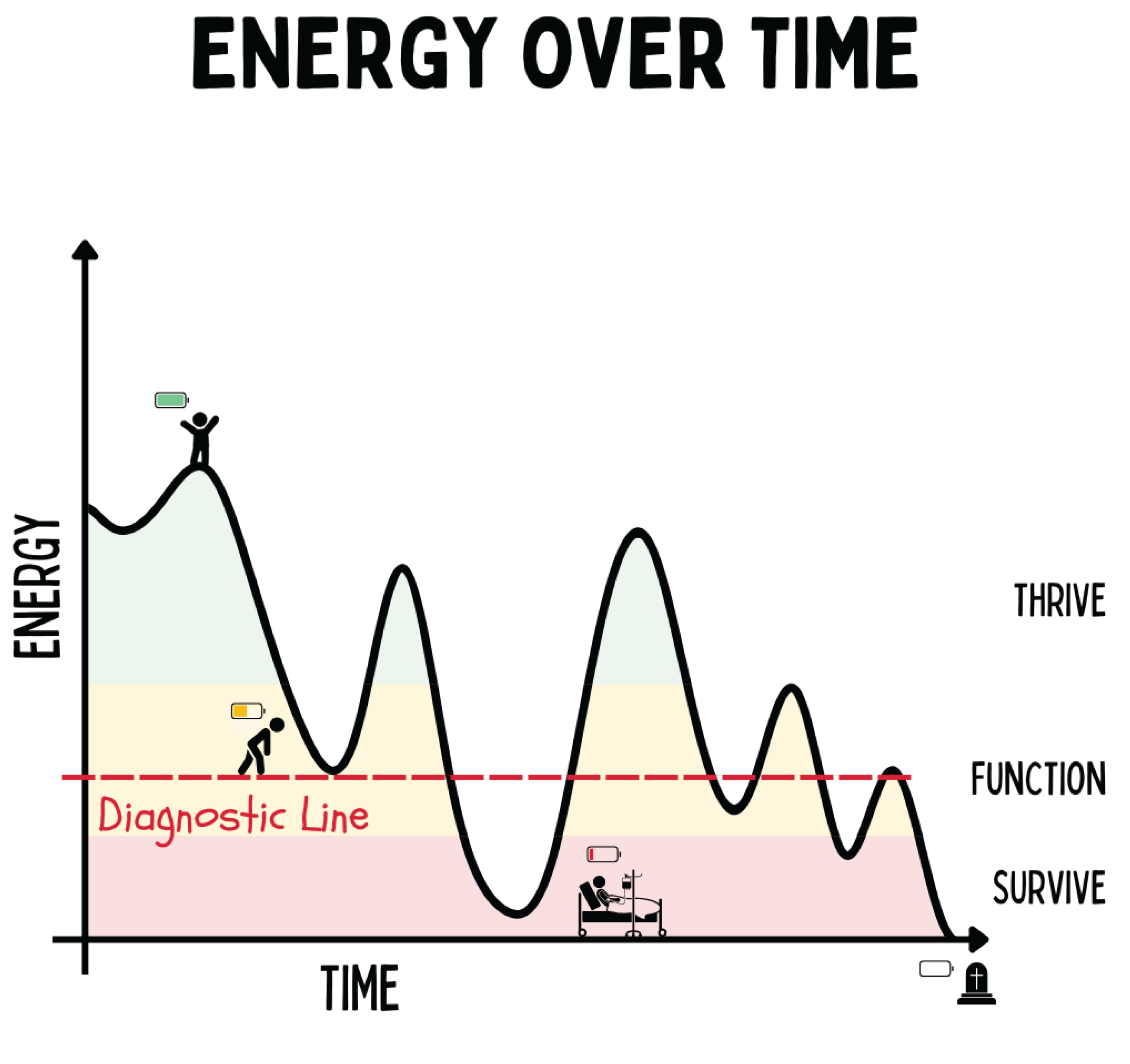

Figure 7.

The figure illustrates the trajectory of human energy over time and distinguishes three states of being: Living (high energy, vitality), Functioning (adapted performance capacity), and Existing (reduced energy, illness). Transitions between these states are determined by the capacity for regeneration and adaptation. Falling below the threshold of “functioning” leads to decompensation and disease, whereas repeated regenerative impulses enable a shift upward into the realm of “living.” Which symptoms and/or diseases emerge under energy deficiency depends on individual (epi)genetic factors.

Figure 7.

The figure illustrates the trajectory of human energy over time and distinguishes three states of being: Living (high energy, vitality), Functioning (adapted performance capacity), and Existing (reduced energy, illness). Transitions between these states are determined by the capacity for regeneration and adaptation. Falling below the threshold of “functioning” leads to decompensation and disease, whereas repeated regenerative impulses enable a shift upward into the realm of “living.” Which symptoms and/or diseases emerge under energy deficiency depends on individual (epi)genetic factors.

4.1. Health and Disease Are States of Energy Allocation

The human organism’s ability to provide and utilize energy is primarily limited by its mitochondrial reservoir — that is, the number, network connectivity, and functional capacity of mitochondria within the cells. Mitochondria are the “powerhouses” of the cell and generate approximately 90 % of cellular energy in the form of ATP.[

37] They therefore largely determine the upper limit of what can be transformed as total energy expenditure (TEE) per unit of time. Put simply: even if energy in the form of substrates (e.g., glucose, fats) is abundantly available, the body can only process as much energy as the mitochondria can produce through oxidative phosphorylation.

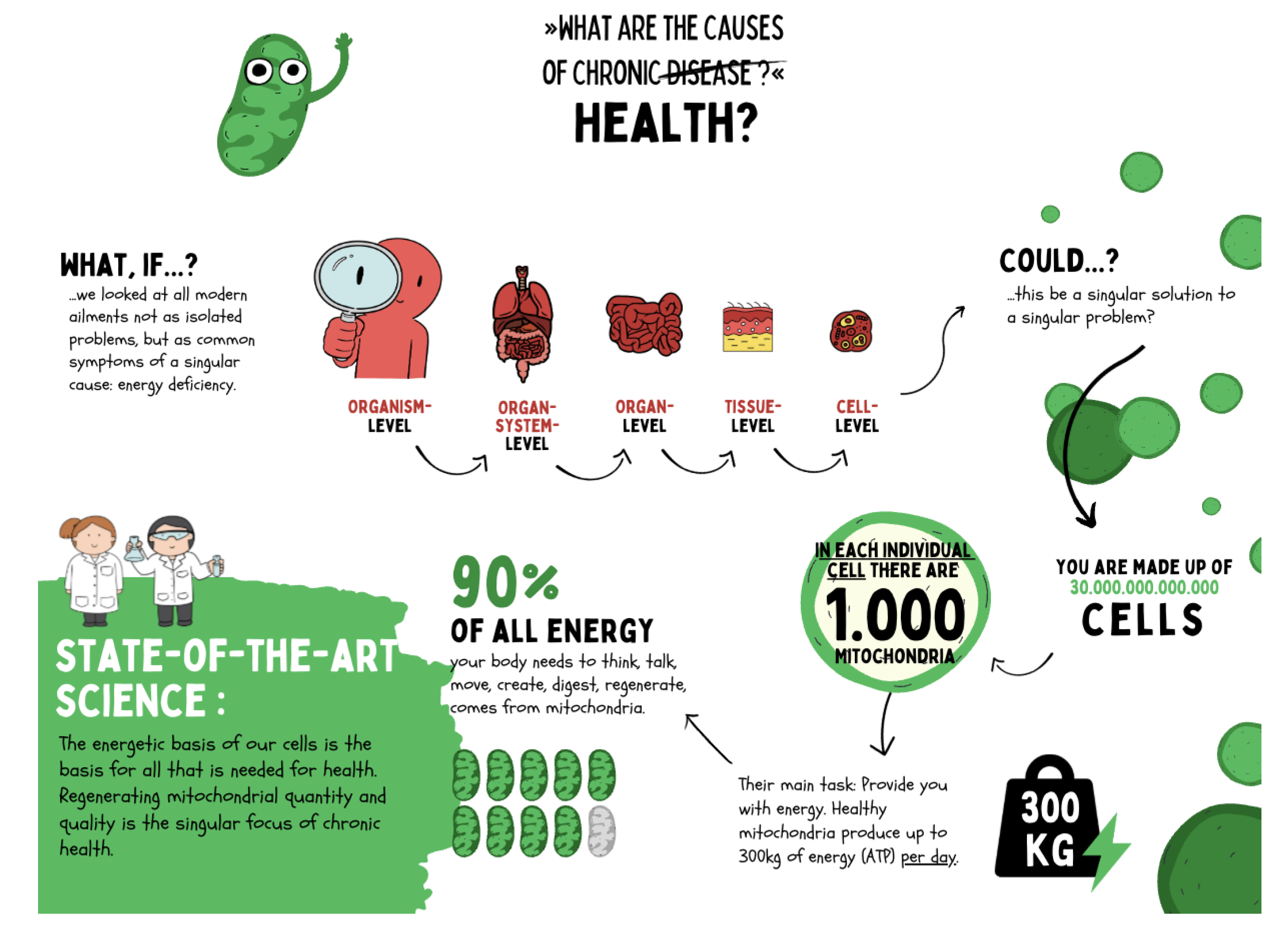

Figure 8.

Chronic diseases are not merely expressions of organ- or system-specific dysfunctions but originate from shared causes at the cellular level. Current research shows that mitochondria are responsible for over 90 % of cellular energy production and thus form the foundation of regeneration, adaptation, and health. Each cell contains on average about 1,000 mitochondria, producing up to 300 kg of ATP per day. Impairments in mitochondrial function lead to systemic energy deficits that manifest at the organ and organism levels as chronic disease. Regenerative medicine therefore focuses on restoring mitochondrial integrity to sustainably promote health.

Figure 8.

Chronic diseases are not merely expressions of organ- or system-specific dysfunctions but originate from shared causes at the cellular level. Current research shows that mitochondria are responsible for over 90 % of cellular energy production and thus form the foundation of regeneration, adaptation, and health. Each cell contains on average about 1,000 mitochondria, producing up to 300 kg of ATP per day. Impairments in mitochondrial function lead to systemic energy deficits that manifest at the organ and organism levels as chronic disease. Regenerative medicine therefore focuses on restoring mitochondrial integrity to sustainably promote health.

Once oxidative capacity is exhausted, it acts as a ceiling for overall metabolism — Herman Pontzer refers to this as Constrained Total Energy Expenditure (CTEE), an evolutionarily determined plateau of total energy turnover. Empirical studies, for example, show that maximal oxygen uptake (VO

2max) — a measure of aerobically achievable energy turnover — depends substantially on mitochondrial capacity and declines as mitochondrial function diminishes.[

38]

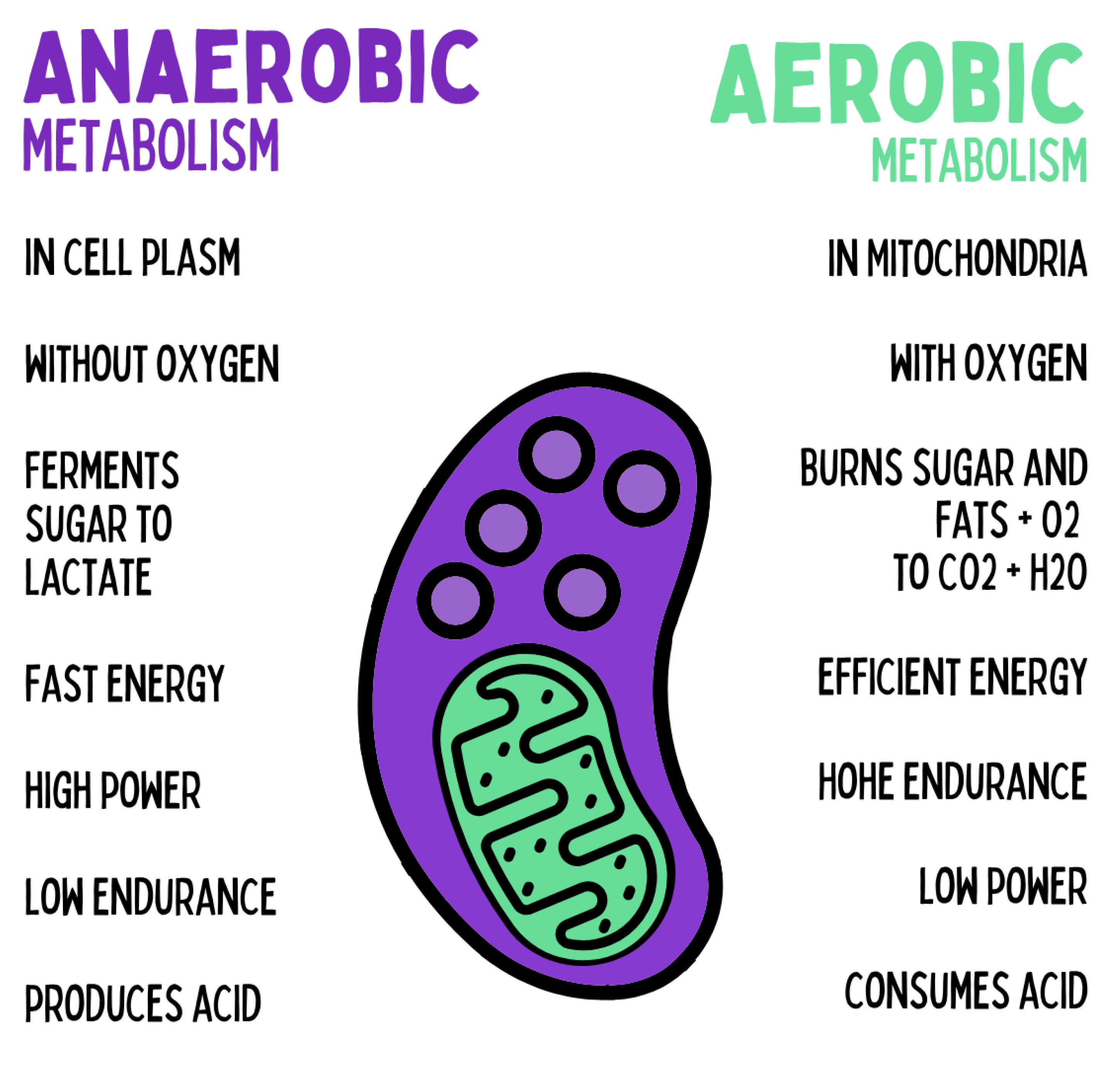

The cell possesses two complementary energy systems: the primary oxidative metabolism within mitochondria and the evolutionarily older anaerobic glucose metabolism in the cytoplasm. While mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) accounts for the majority of ATP production at rest and during moderate activity, anaerobic glycolysis serves as an emergency system during acute metabolic, immunological, or neuronal stress situations. This rapid energy release (“stress metabolism”) enables short-term ATP generation independent of oxygen availability but entails characteristic side effects: lactate accumulation leads to intracellular acidification, and a chronically reduced NAD

+/NADH ratio impairs redox-dependent enzymes and epigenetic regulation.[

39,

40]

Figure 9.

The cell possesses two complementary energy systems: anaerobic metabolism in the cytoplasm, which rapidly ferments glucose to lactate without oxygen and provides large amounts of energy in the short term — but causes acidification and limited endurance — and aerobic metabolism in the mitochondria, which oxidizes glucose and fats with oxygen to CO₂ and H₂O, thereby enabling sustainable, efficient energy production with high endurance.

Figure 9.

The cell possesses two complementary energy systems: anaerobic metabolism in the cytoplasm, which rapidly ferments glucose to lactate without oxygen and provides large amounts of energy in the short term — but causes acidification and limited endurance — and aerobic metabolism in the mitochondria, which oxidizes glucose and fats with oxygen to CO₂ and H₂O, thereby enabling sustainable, efficient energy production with high endurance.

Immunologically, a chronically glycolytic metabolism results in a pro-inflammatory state. Effector cells such as macrophages and T cells exhibit a predominant M1 or Th17 polarization under sustained glycolysis, releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1

, TNF-

) while inhibiting resolution signals. In contrast, regulatory T cells and M2 macrophages — which are essential for immune tolerance and tissue repair — depend on mitochondrial OXPHOS and fatty acid oxidation.[

41,

42]

Neuronal systems respond similarly: a chronically glycolysis-dominated energy supply leads to reduced mitochondrial ATP availability at synapses, thereby impairing the maintenance of synaptic transmission and glutamate homeostasis. The resulting excitotoxic imbalance is exacerbated by impaired neurotransmitter reuptake and disturbed calcium homeostasis.[

43,

44]

Furthermore, a persistently low NAD

+/NADH ratio has been shown to inhibit sirtuin-dependent regulation of mitophagy and DNA repair, causing neuronal networks to lose their capacity for regeneration and plasticity.[

45]

Recent findings demonstrate that sustained suppression of mitochondrial activity by chronic glycolysis directly inhibits neuronal mitophagy, thereby preventing the renewal of dysfunctional mitochondria — leading to the accumulation of oxidatively damaged organelles and long-term neurodegenerative vulnerability.[

43]

In contrast, mitochondrial oxidative metabolism offers a regenerative countermodel: OXPHOS-dominant states allow efficient ATP production, promote sirtuin and PARP activity through NAD

+ regeneration, and activate mechanisms of mitohormesis via ROS signaling at hormetic doses. These mechanisms stimulate mitophagy, biogenesis, and epigenetic stability, enabling both the immune system and neuronal networks to develop greater resilience against stress and degeneration.[

43,

46]

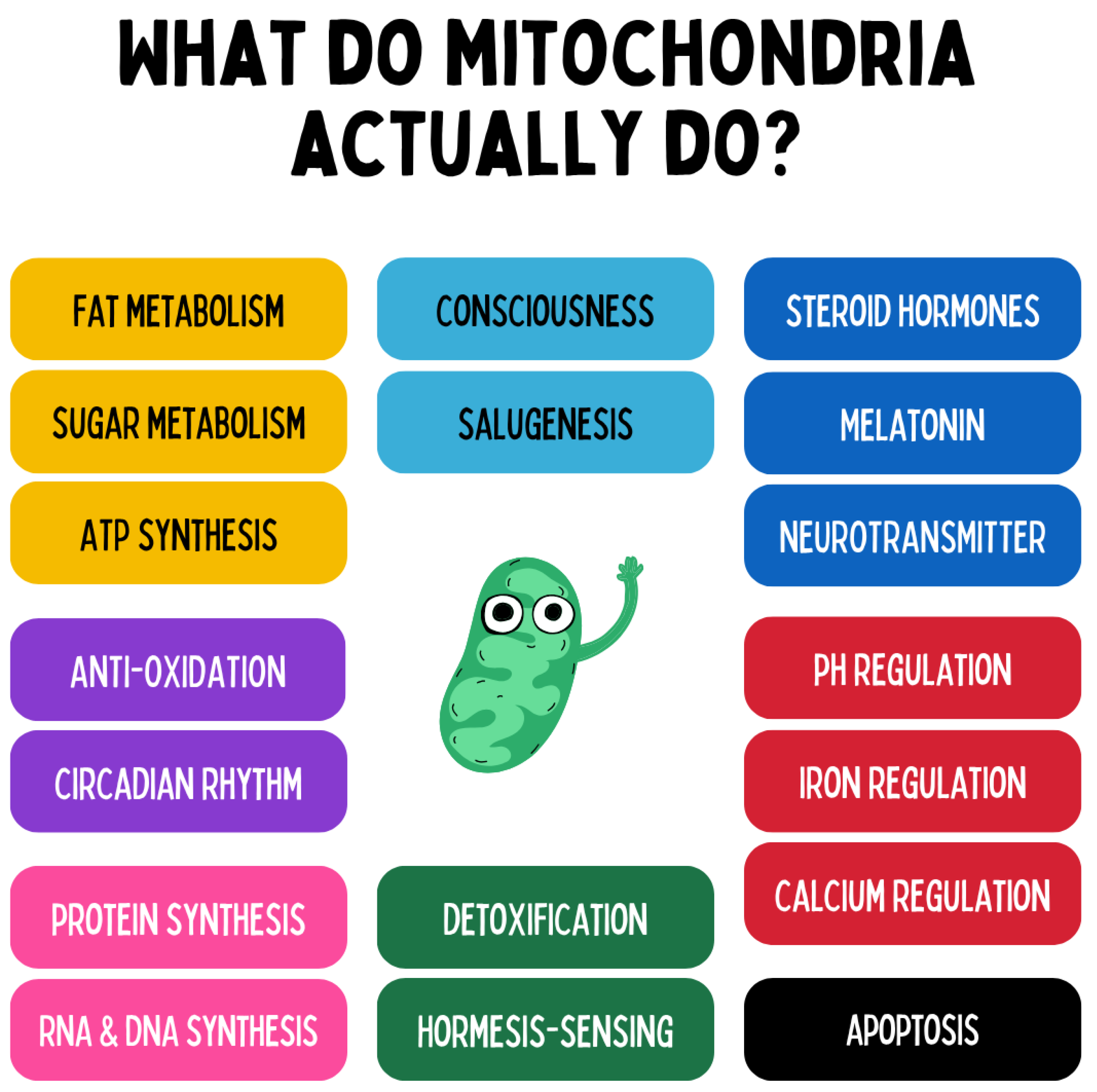

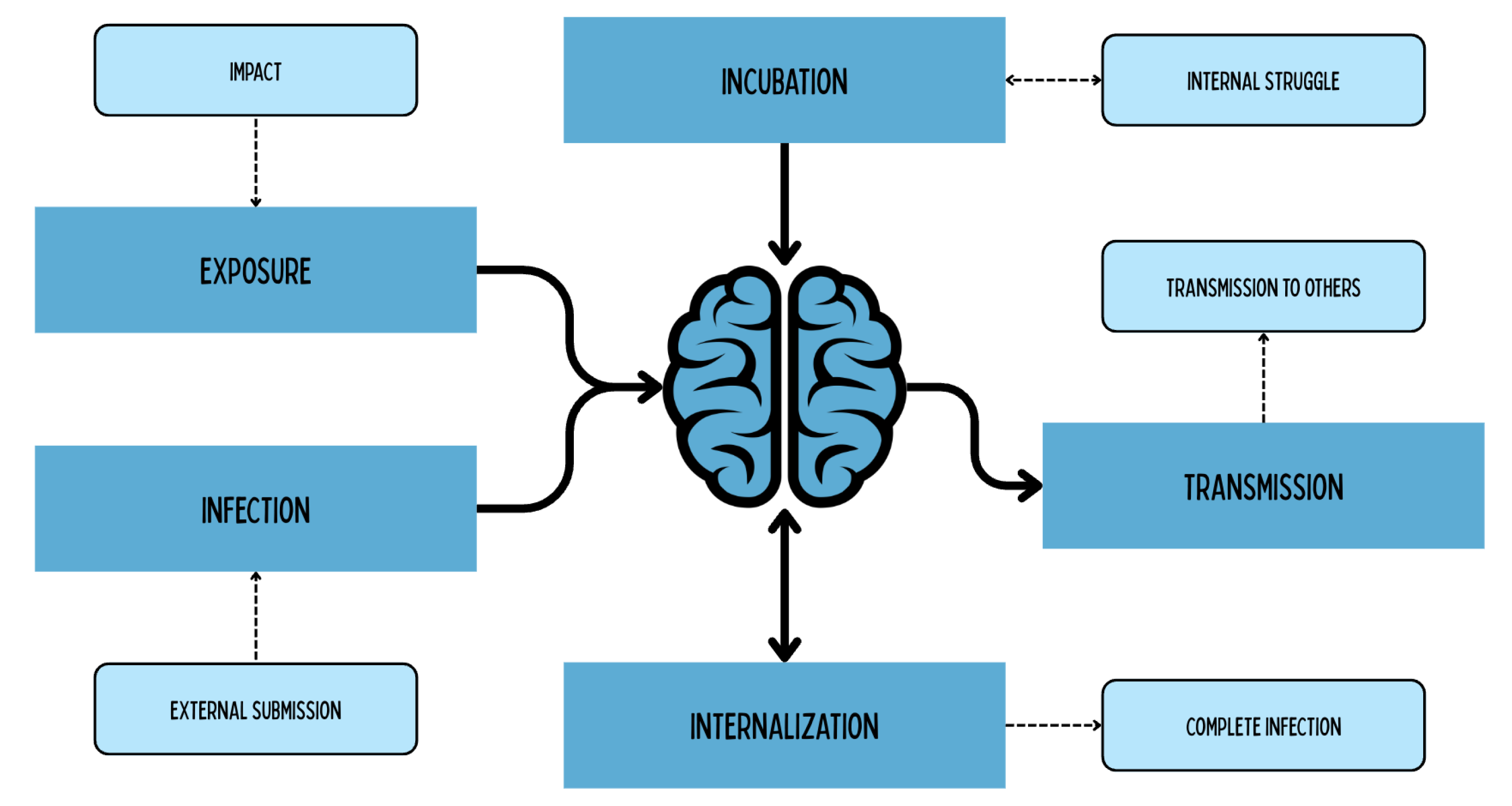

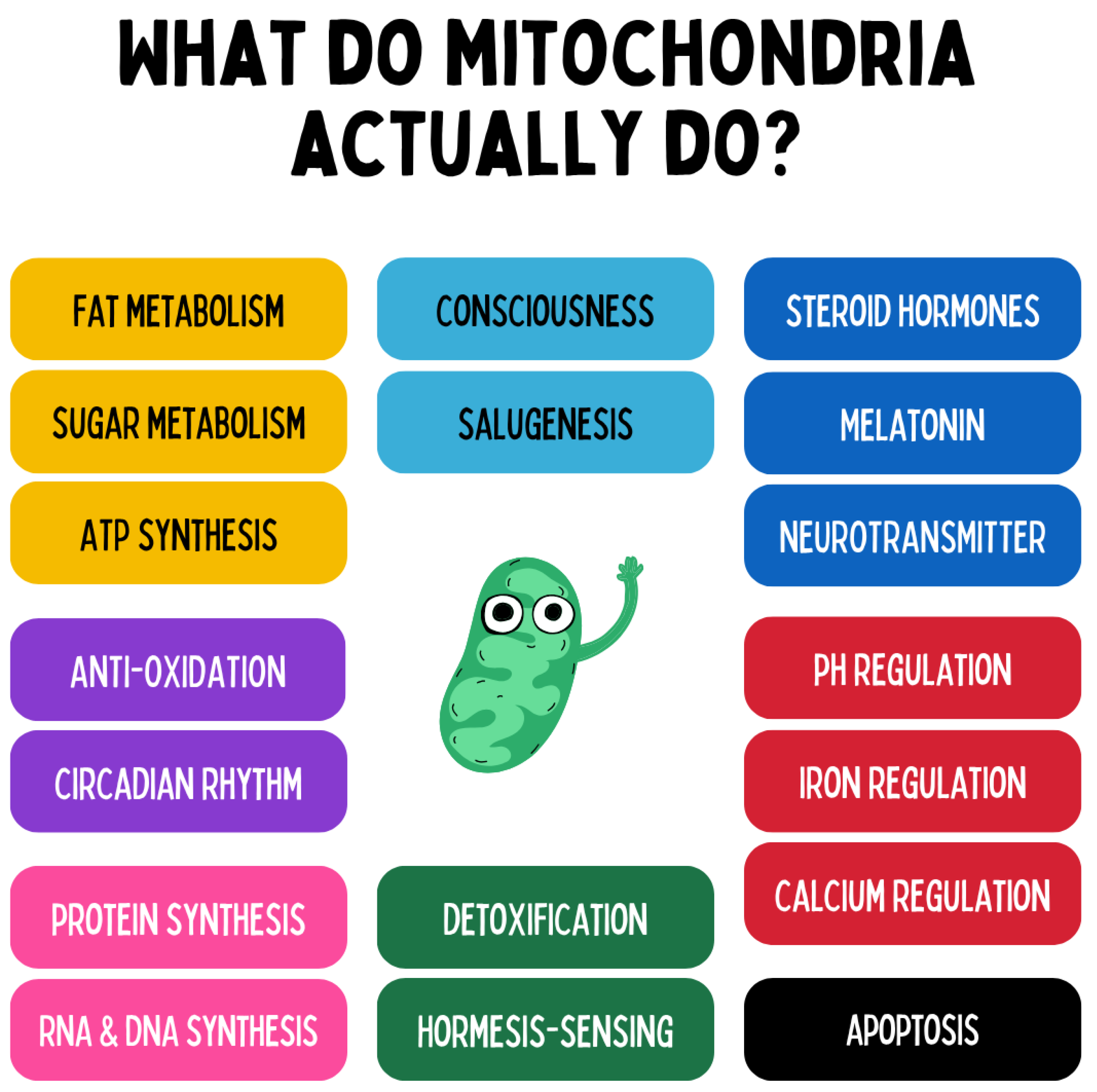

Figure 10.

Mitochondria perform far more functions than classical ATP production. They are central

metabolic control hubs that regulate fat and glucose metabolism and provide the organism’s main energy source through oxidative phosphorylation. In addition, they act as

redox and hormesis sensors that respond to stress signals, control oxidative status, and activate adaptive programs. On a molecular level, mitochondria are involved in the

regulation of protein synthesis, RNA/DNA production, and cellular calcium and iron homeostasis. They also modulate the

internal clock (circadian rhythms), participate in the

synthesis of steroid hormones, neurotransmitters, and melatonin, and orchestrate processes such as

apoptosis (programmed cell death). Moreover, mitochondria are integral components of

cellular detoxification, immune responses, and salutogenesis, as they regulate gene expression, cell regeneration, and intercellular communication via metabolites and signaling molecules. Thus, they function as a

central informational and regulatory organelle that extends far beyond bioenergetic processes, deeply embedded in the control of health, disease, and adaptation.[

46]

Figure 10.

Mitochondria perform far more functions than classical ATP production. They are central

metabolic control hubs that regulate fat and glucose metabolism and provide the organism’s main energy source through oxidative phosphorylation. In addition, they act as

redox and hormesis sensors that respond to stress signals, control oxidative status, and activate adaptive programs. On a molecular level, mitochondria are involved in the

regulation of protein synthesis, RNA/DNA production, and cellular calcium and iron homeostasis. They also modulate the

internal clock (circadian rhythms), participate in the

synthesis of steroid hormones, neurotransmitters, and melatonin, and orchestrate processes such as

apoptosis (programmed cell death). Moreover, mitochondria are integral components of

cellular detoxification, immune responses, and salutogenesis, as they regulate gene expression, cell regeneration, and intercellular communication via metabolites and signaling molecules. Thus, they function as a

central informational and regulatory organelle that extends far beyond bioenergetic processes, deeply embedded in the control of health, disease, and adaptation.[

46]

A unifying model that links mitochondrial function, energy metabolism, and the emergence of chronic disease is the recently proposed

Energy Resistance Principle (ERP).[

47] This framework posits that life is fundamentally defined by the continuous flow of energy through resistive biological structures. Just as electrical current requires resistance to be converted into useful work, biological energy—flowing as electrons from nutrients to oxygen—requires resistive biological networks to be transformed into structure, information, and function. Resistance in this context (

) is not a flaw but a feature: it enables the controlled conversion of energy into cellular work, adaptation, and signaling.

Formally, the ERP can be expressed as:

where

energy potential (

) captures the system’s drive to perform work (e.g., substrate availability, hormonal and inflammatory loads),

f denotes electron flux from nutrients to oxygen (a proxy for mitochondrial throughput), and

is the emergent

energy resistance. Health exists within a narrow range of

, where energy flow is neither excessively restricted nor unregulated. If

is too low (e.g., in hyperproliferative states), energy dissipates into uncontrolled transformation; if

is too high (e.g., due to mitochondrial dysfunction, hypoxia, or nutrient overload), electron flow congests, yielding reductive/oxidative stress, electron leak, and impaired cellular function.[

47]

Chronically elevated

slows electron flux and raises the NADH/NAD

+ ratio (

reductive stress), fostering secondary reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, inflammatory signaling, and metabolic inflexibility [

48,

49]. Cells respond by activating integrated stress responses and releasing metabolic distress signals. Among these,

growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15) has emerged as a robust, mitochondria-linked cytokine that tracks energetic overload and mitochondrial stress [

50]. GDF15 is induced by impediments to the electron transport chain, nutrient oversupply, and mitochondrial proteostatic stress, and its circulating levels correlate with multimorbidity, cardiometabolic disease, neurodegeneration, and biological aging [

50,

51].

Viewed through the ERP, rising GDF15 reflects a systemic attempt to mitigate excessive

by lowering

— for example, via appetite suppression, sickness behavior, and activity reduction — while the underlying bioenergetic bottleneck (low

f) remains unresolved [

47,

50]. This framing recasts common chronic conditions (e.g., type 2 diabetes, atherosclerosis, neurodegeneration) as organism-level manifestations of persistently elevated

: their shared hallmarks — inflammation, oxidative stress, anabolic suppression, and fatigue — represent downstream consequences of congested electron flow and impaired mitochondrial throughput.

The ERP suggests two broad therapeutic levers: (i)

decrease and (ii)

increase f. Interventions that reduce

include caloric restriction/fasting, sleep optimization, and stress-reduction practices that lower neuroendocrine drive and resting energy demand [

39,

52]. Interventions that increase

f include endurance exercise and mitochondrial biogenesis, improved tissue oxygenation/vascularization, and metabolic support (e.g., NAD

+ repletion, enhancing OXPHOS efficiency), each expanding oxidative capacity and lowering

nonlinearly because

f enters the denominator as

[

53,

54,

55].

Within this paradigm,

GDF15 functions as an actionable biomarker of . Declines in circulating GDF15 with training, sleep restoration, or metabolic reconditioning indicate relief of energetic congestion and restoration of mitochondrial homeostasis; conversely, persistent or rising GDF15 may flag unresolved bioenergetic bottlenecks despite symptom-focused care [

47,

50]. Practically, an

energy-based medicine approach would (1) quantify drivers of high

(hyperglycemia, lipids, catecholamines, inflammation), (2) assess flux capacity (

f) via aerobic fitness and mitochondrial/vascular indices, and (3) track

-linked markers (GDF15, lactate/pyruvate, alanine, redox ratios) to titrate lifestyle and pharmacologic interventions toward an individualized

Goldilocks zone of energy resistance that supports regeneration, resilience, and healthy longevity [

47,

50].

Viewed positively, , the mitochondrial reservoir is plastic: through training, adaptation, and regenerative processes, the number of mitochondria can be increased and their networks optimized; conversely, inactivity, aging, or damage lead to depletion of this reservoir. The central thesis, therefore, is that the available mitochondrial reservoir limits maximal energy turnover but is regenerable through targeted interventions.[

46,

56]

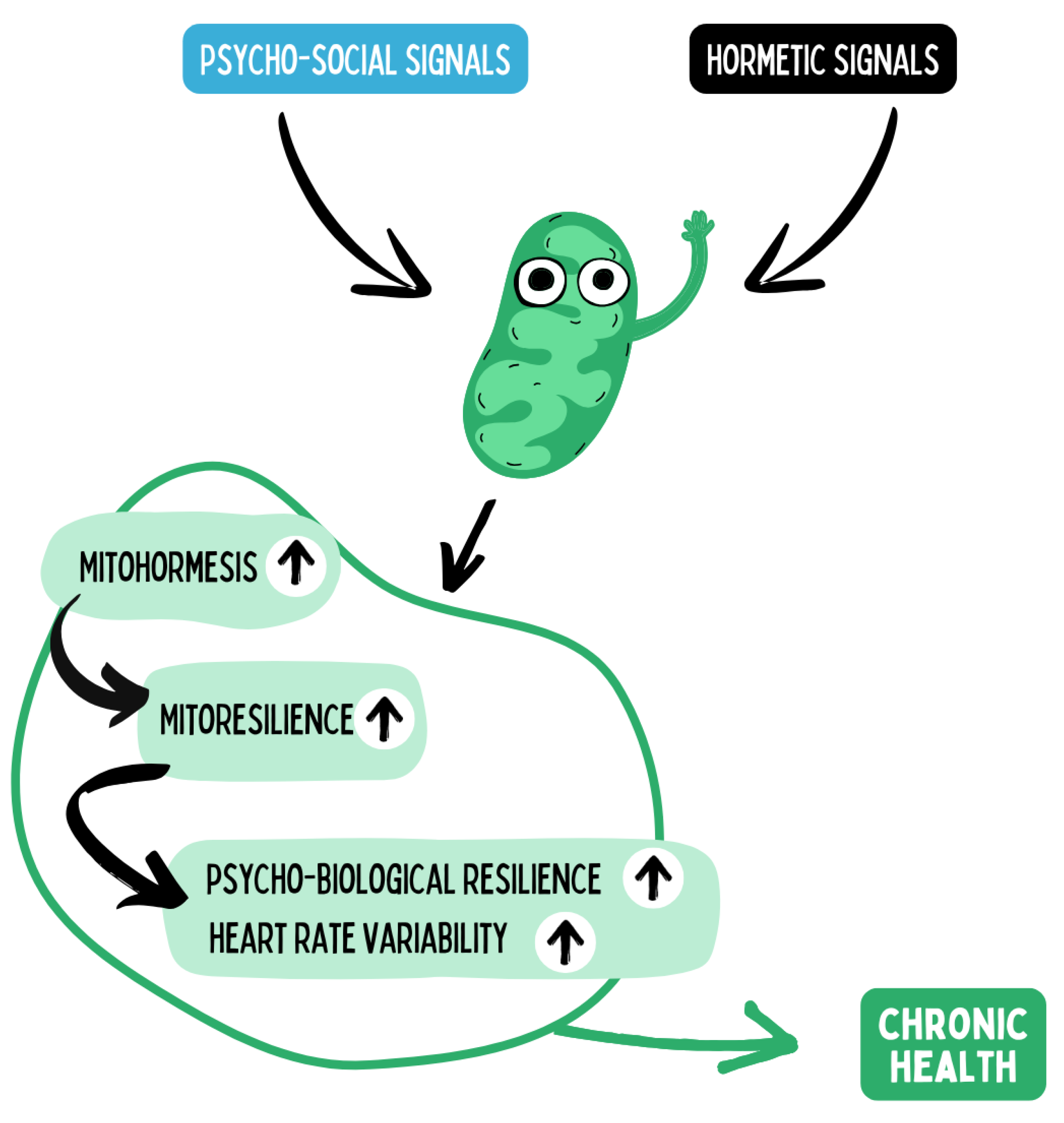

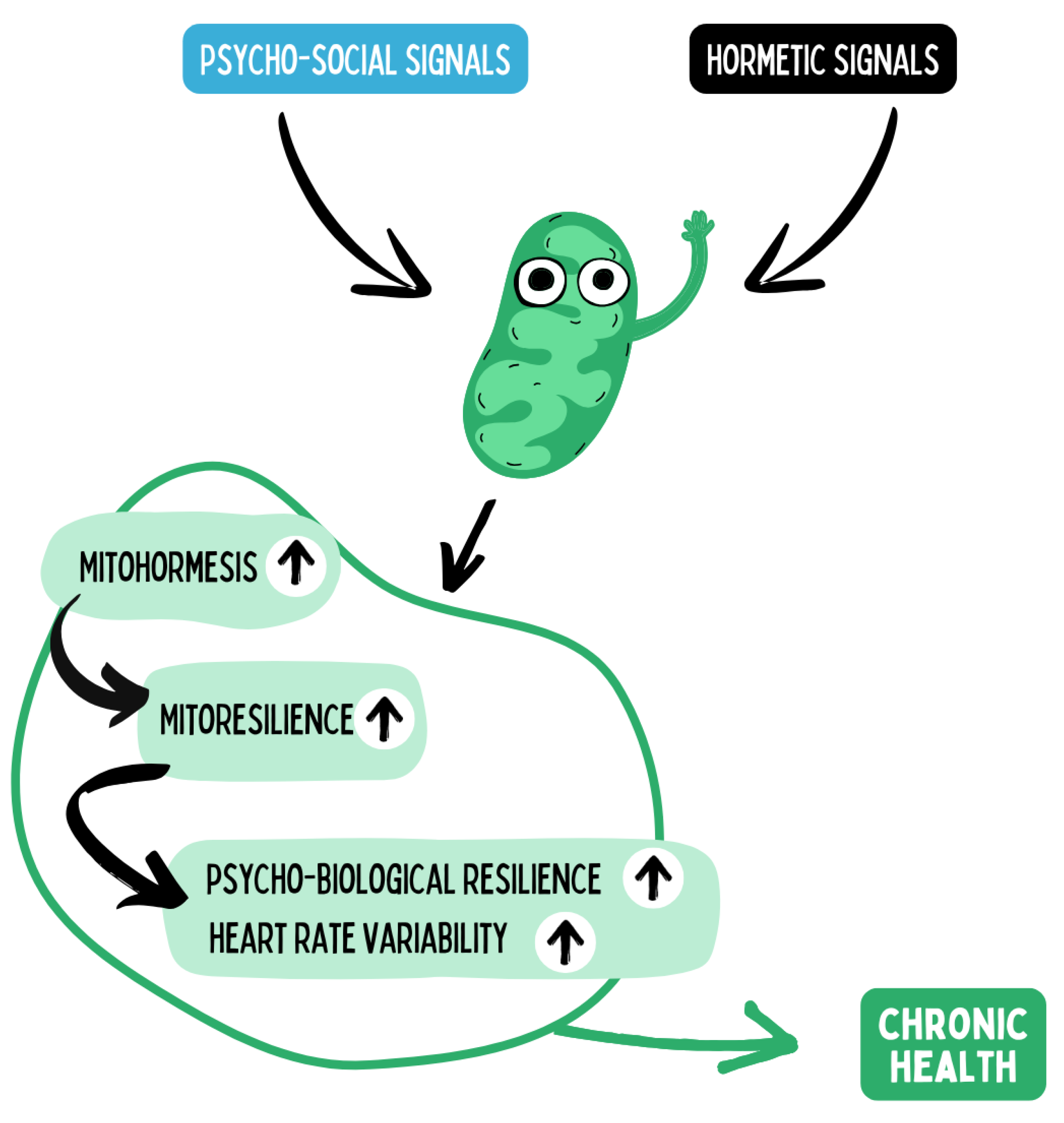

Figure 11.

Mitochondria function as central sensors for both hormetic stimuli (e.g., physical activity, fasting, hypoxia, temperature stress) and psychosocial influences (e.g., stress, social support, sense of coherence). These signals modulate mitohormesis — the adaptive mitochondrial response to intermittent stress — activating processes such as biogenesis, fusion/fission, and mitophagy. Repeated mitohormesis leads to enhanced mitochondrial resilience, defined as an increased capacity to maintain energy production and redox homeostasis under stress conditions. This mitochondrial plasticity translates at the systemic level into improved psychobiological resilience, measurable for instance through heart rate variability (HRV) as a marker of autonomic flexibility. Over the long term, these processes promote chronic health by stabilizing the balance of energy allocation, neuro-immuno-metabolic regulation, and stress adaptation. Hence, mitochondrial mechanisms represent the biological interface through which lifestyle and psychosocial factors are translated into salutogenic effects.

Figure 11.

Mitochondria function as central sensors for both hormetic stimuli (e.g., physical activity, fasting, hypoxia, temperature stress) and psychosocial influences (e.g., stress, social support, sense of coherence). These signals modulate mitohormesis — the adaptive mitochondrial response to intermittent stress — activating processes such as biogenesis, fusion/fission, and mitophagy. Repeated mitohormesis leads to enhanced mitochondrial resilience, defined as an increased capacity to maintain energy production and redox homeostasis under stress conditions. This mitochondrial plasticity translates at the systemic level into improved psychobiological resilience, measurable for instance through heart rate variability (HRV) as a marker of autonomic flexibility. Over the long term, these processes promote chronic health by stabilizing the balance of energy allocation, neuro-immuno-metabolic regulation, and stress adaptation. Hence, mitochondrial mechanisms represent the biological interface through which lifestyle and psychosocial factors are translated into salutogenic effects.

4.2. Mitohormesis Regulates the Mitochondrial Reservoir

How can the mitochondrial reservoir be increased or decreased? This is where the principle of mitohormesis comes into play. It refers to the adaptive, compensatory responses of the cell to the right combination of moderate stress stimuli (challenges) and resources in the form of orthomolecular nutrients, sleep, and psychosocial resonance. Intermittent, acute stressors — such as physical exercise, short-term hypoxia, cold exposure, or fasting — lead to a transient increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) and other mitochondrial signals. In low doses and under conditions of sufficient resources, these signaling molecules are not primarily harmful but act as triggers for adaptive processes: they induce the expression of genes for mitochondrial biogenesis, promote the formation of mitochondrial networks (fusion), and activate repair and recycling mechanisms (mitophagy). In this way, mitohormesis improves oxidative capacity and increases the mitochondrial reservoir in the long term.[

46] Ristow and Schmeisser describe that small amounts of ROS act as signaling molecules that activate defense mechanisms and thereby promote health rather than causing damage, whereas high and sustained ROS exposure remains detrimental.[

21]

Mitohormetic effects are mediated at the molecular level through conserved stress response pathways — for example, via redox sensors, the energy-status sensor AMPK, the growth regulator mTOR, the mitochondrial coactivator PGC-1, as well as sirtuins and other signaling axes. These factors interact within complex networks to promote anabolic (building) or catabolic (degrading) programs depending on the pattern of stimulation. Chronic underload (e.g., prolonged physical inactivity) or overload (e.g., sustained oxidative stress without recovery phases or antioxidant resources) reduces mitohormetic adaptation: mitochondrial number and function decline, the network becomes fragmented, and the maximal rate of energy turnover decreases. The mitohormesis hypothesis therefore emphasizes that a certain degree of short-term cellular stress is necessary to increase mitochondrial resilience — and thus health — over the long term.

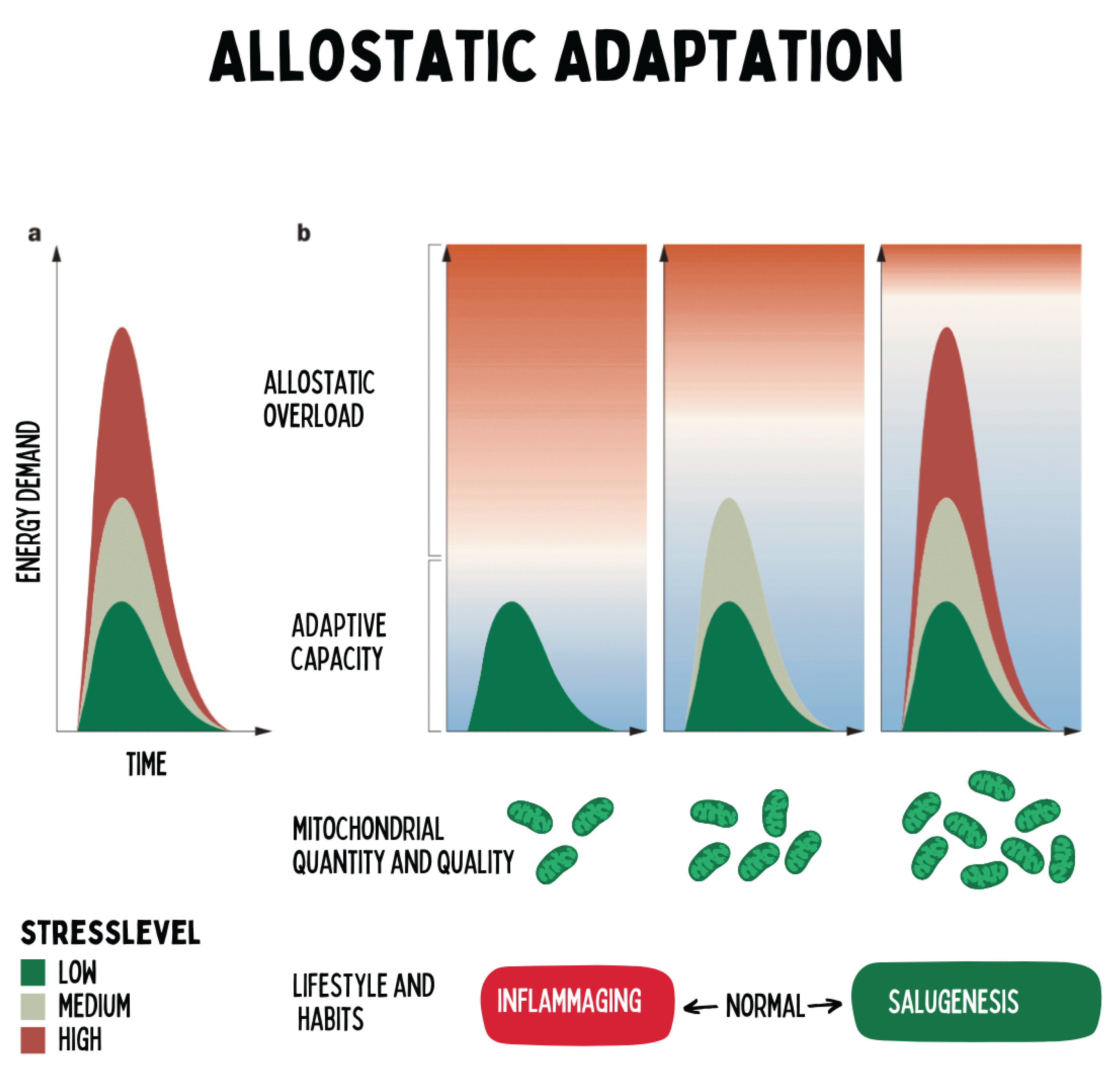

Figure 12.

The figure illustrates the concept of allostatic adaptation: the energy demand of an organism rises with the intensity and duration of stress stimuli. The ability to meet this demand depends on the adaptive capacity, which is largely determined by the number and functionality of mitochondria. When mitochondrial performance is reduced — for example, due to physical inactivity or aging — the stress threshold shifts downward, meaning that even moderate stressors can cause allostatic overload. In contrast, regular physical activity increases mitochondrial biogenesis and functional reserve, thereby enhancing stress resilience. The model shows that chronic health arises not primarily from the absence of stress, but from the optimization of mitochondrial adaptive capacity. Regenerative medicine therefore focuses on promoting this capacity through hormetic stimuli, lifestyle interventions, and the restoration of energetic flexibility.

Figure 12.

The figure illustrates the concept of allostatic adaptation: the energy demand of an organism rises with the intensity and duration of stress stimuli. The ability to meet this demand depends on the adaptive capacity, which is largely determined by the number and functionality of mitochondria. When mitochondrial performance is reduced — for example, due to physical inactivity or aging — the stress threshold shifts downward, meaning that even moderate stressors can cause allostatic overload. In contrast, regular physical activity increases mitochondrial biogenesis and functional reserve, thereby enhancing stress resilience. The model shows that chronic health arises not primarily from the absence of stress, but from the optimization of mitochondrial adaptive capacity. Regenerative medicine therefore focuses on promoting this capacity through hormetic stimuli, lifestyle interventions, and the restoration of energetic flexibility.

4.3. Balance Between Challenge and Resources Regulates Mitohormesis

The effects of mitohormesis demonstrate that the correct dosage and balance of stressors are crucial. For optimal regenerative adaptation, an equilibrium must exist between challenges (stressors) and resources (recovery and protective factors). Challenges include physical exercise, temporary food restriction, cold exposure, but also immunological stimuli (e.g., vaccination, infection) or psychological challenges. Resources, on the other hand, include high-quality nutrition, sufficient sleep, warmth, psychosocial support, and relaxation.[

57]

Only a dynamic equilibrium — the interplay of strain and recovery — triggers a net positive adaptation of the organism. This idea aligns with the concept of allostasis: allostatic adaptation means that the body flexibly responds to changing conditions to achieve stability at a higher level. Bruce McEwen and colleagues described that health is ultimately the ability to adapt — a stable equilibrium is not a static resting state but a resilient oscillation within a tolerable range. Chronic imbalance, however — whether from persistent overload (e.g., prolonged biopsychosocial stress without recovery) or chronic deficiency (e.g., sustained underload or nutrient deprivation) — shifts the system toward degeneration. The body then loses its reserve capacities; the result includes persistent inflammation, chronic stress, metabolic dysregulation, and, ultimately, structural and functional tissue damage.[

35,

58]

The concept of allostasis highlights that health is dynamic. An organism that can flexibly respond to stress remains healthy; those who lose this flexibility become ill. Regenerative medicine therefore aims to individually optimize the balance between targeted challenge and adequate recovery in order to achieve a net gain in health reserves.[

33]

4.4. Mitochondrial Metabolism Is the Central Regeneration Switch

Depending on whether an organism is in this state of equilibrium or not, mitochondrial metabolism follows different pathways. In the regenerative mode — that is, when sufficient resources and mild, intermittent challenges are present — processes such as mitochondrial fusion (network formation), biogenesis (creation of new mitochondria), and efficient mitophagy (removal of damaged mitochondria) predominate. These processes ensure high energy efficiency and quality control. In the degenerative mode, by contrast — for example, under chronic stress or lack of recovery — mitochondria increasingly fragment, produce excessive amounts of free radicals (ROS excess), and, in the worst case, initiate cell death programs (apoptosis).[

24,

59]

This metabolic switch within the mitochondria affects the entire organism. Mitochondria not only act as energy providers but also as signaling hubs connecting metabolism, the immune system, and neural function. In situations of threat or stress, mitochondria alter their function: they downregulate ATP production in favor of an “alarm broadcast.” Robert Naviaux describes this as the Cell Danger Response (CDR): mitochondria prioritize safety over efficiency by releasing pro-inflammatory signals and pausing anti-inflammatory routines during perceived danger. In this way, they help alert immune cells and isolate affected tissues. Only once the threat has passed do mitochondria return to their normal mode, enabling the resolving healing phase (“resolution”), for instance by switching to anti-inflammatory mediators and supporting tissue reconstruction.[

32,

60]

Figure 13.

Mechanistic acute medicine addresses acute diseases by focusing on extrinsic causes such as pathogens or structural damage, aiming for their elimination or repair. In contrast, the regenerative medical perspective is based on organic systems biology and describes the ontogenetic sequence of intrinsic healing processes (inflammation, proliferation, differentiation) and their effects on human function and structure (“form follows function”). If a functional state persists, chronicity results.

Figure 13.

Mechanistic acute medicine addresses acute diseases by focusing on extrinsic causes such as pathogens or structural damage, aiming for their elimination or repair. In contrast, the regenerative medical perspective is based on organic systems biology and describes the ontogenetic sequence of intrinsic healing processes (inflammation, proliferation, differentiation) and their effects on human function and structure (“form follows function”). If a functional state persists, chronicity results.

According to the concept of salutogenesis, health arises precisely when the transition from alarm mode to healing mode functions smoothly. Mitochondria act as the central pacemakers of the healing cascade: they not only provide the energy required for repair processes but also determine when healing can begin. Chronic diseases can therefore be understood as blocked healing phases, in which mitochondria remain trapped in a state of persistent alarm. Regenerative medicine aims to restore mitochondrial signal balance so that cells can shift from defense mode to regeneration mode. This underscores the dual role of mitochondria: they transduce signals between energy metabolism, immune surveillance, and neuroendocrinology, thus forming the connecting element in salutogenesis.

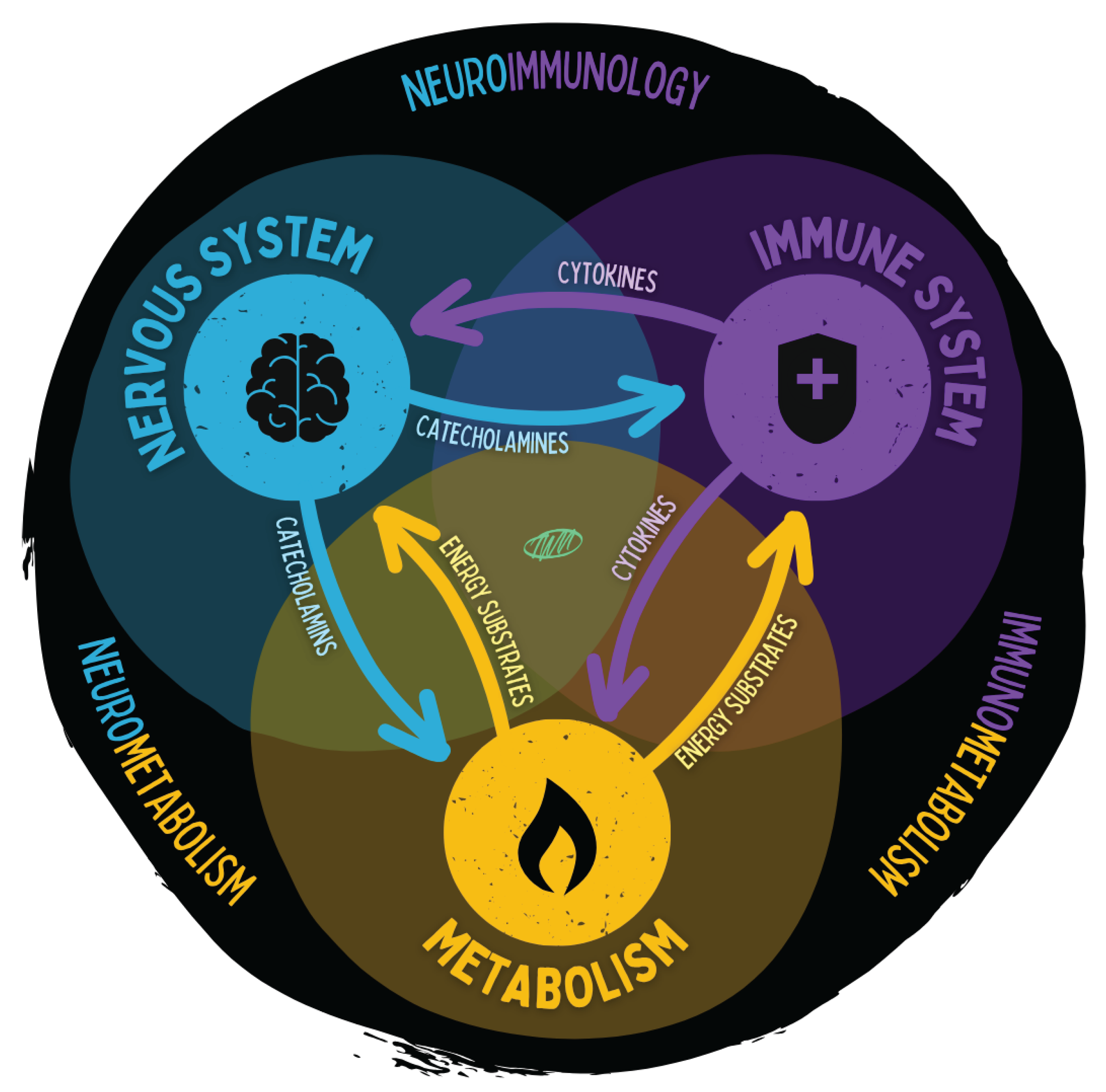

4.5. Three “Selfish” Regulatory Systems as Sensors and Bottom-Up Effectors of Energy Allocation

No organism operates solely at the cellular level — rather, there are overarching regulatory systems that govern energy flow. Three systems are central to this process: the nervous system, the immune system, and metabolism (the endocrine–metabolic system). These act upstream as sensors (detecting danger, needs, and environmental changes) and downstream as effectors (implementing responses by allocating resources accordingly).[

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66]

The communication axes between these systems are diverse:

The nervous system transmits signals via neurotransmitters and catecholaminergic stress hormones (e.g., adrenaline, noradrenaline). Through sympathetic and parasympathetic tone, it directly influences heart rate, vascular tone, and immunological activity.

The immune system communicates primarily through cytokines — messenger molecules that mediate or suppress inflammatory responses, thereby signaling immune stress to the brain and endocrine organs.

Metabolism (particularly endocrine organs such as the pancreas, adipose tissue, and liver) releases metabolic hormones and energy carriers — such as insulin, glucagon, leptin, cortisol, as well as glucose, triglycerides, and lipoproteins — which regulate the nutrient flow to tissues.

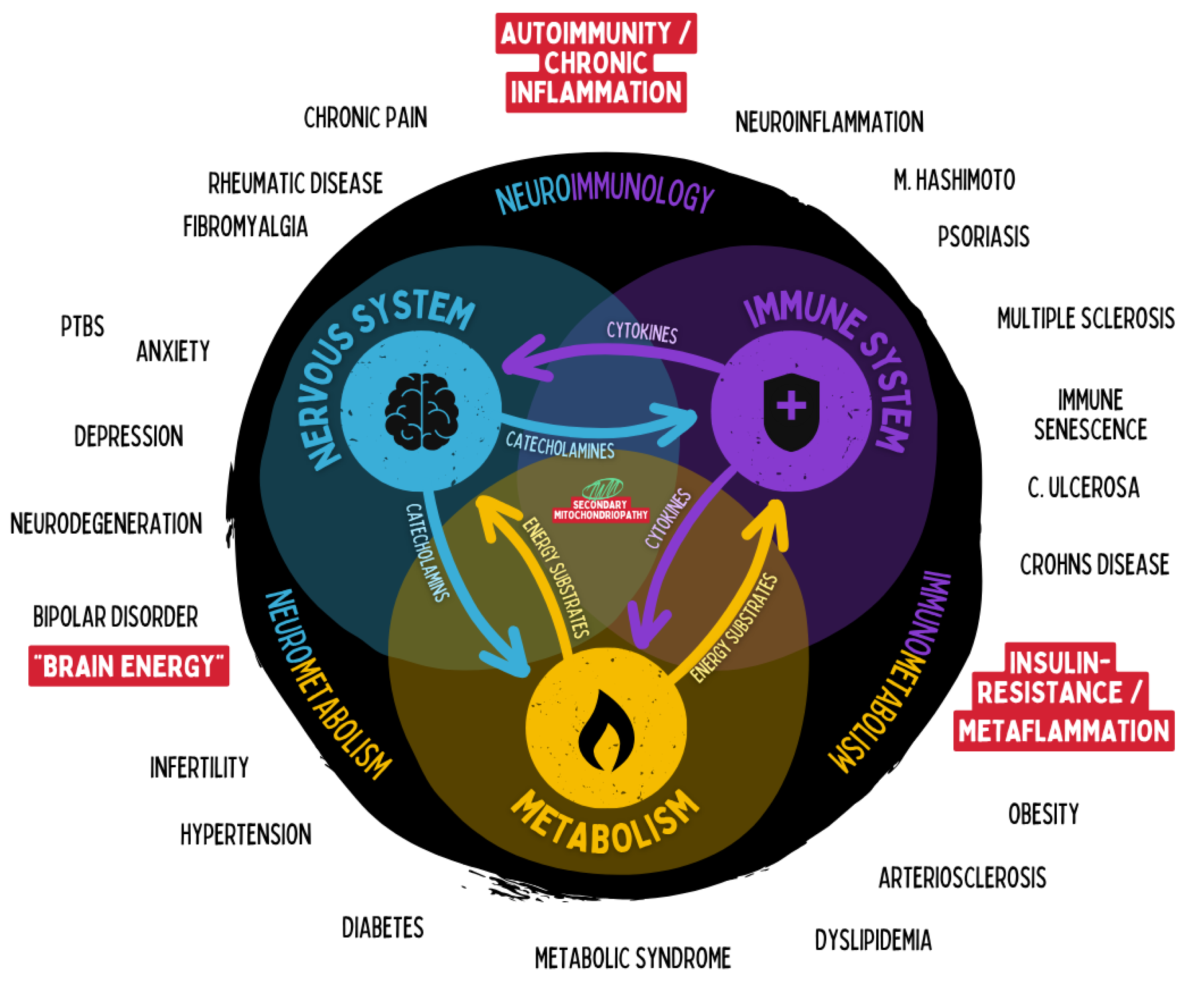

Figure 14.

The figure illustrates the close functional interconnection of the nervous system, immune system, and energy metabolism. Stress hormones, inflammatory mediators, and metabolic energy carriers act as bidirectional messengers coordinating regulation, adaptation, and energy allocation. These axes form the foundation of neuroimmunology, immunometabolism, and neurometabolism. Dysregulation in one system propagates to the others and can give rise to chronic disease states.

Figure 14.

The figure illustrates the close functional interconnection of the nervous system, immune system, and energy metabolism. Stress hormones, inflammatory mediators, and metabolic energy carriers act as bidirectional messengers coordinating regulation, adaptation, and energy allocation. These axes form the foundation of neuroimmunology, immunometabolism, and neurometabolism. Dysregulation in one system propagates to the others and can give rise to chronic disease states.

These three systems are tightly interwoven. For example, the brain responds to pro-inflammatory cytokines with behavioral adjustments (e.g., “sickness behavior” such as fatigue and rest) and with changes in the neuroendocrine axis (activation of the HPA axis and modulation of the autonomic nervous system). Conversely, neuronal signals modulate immune responses — for instance, noradrenaline and cortisol can influence cytokine production. Such feedback loops ultimately serve to adjust energy distribution contextually: during infection, more energy is allocated to the immune system; during a fight-or-flight reaction, to the muscles; and during rest phases, to regenerative processes.

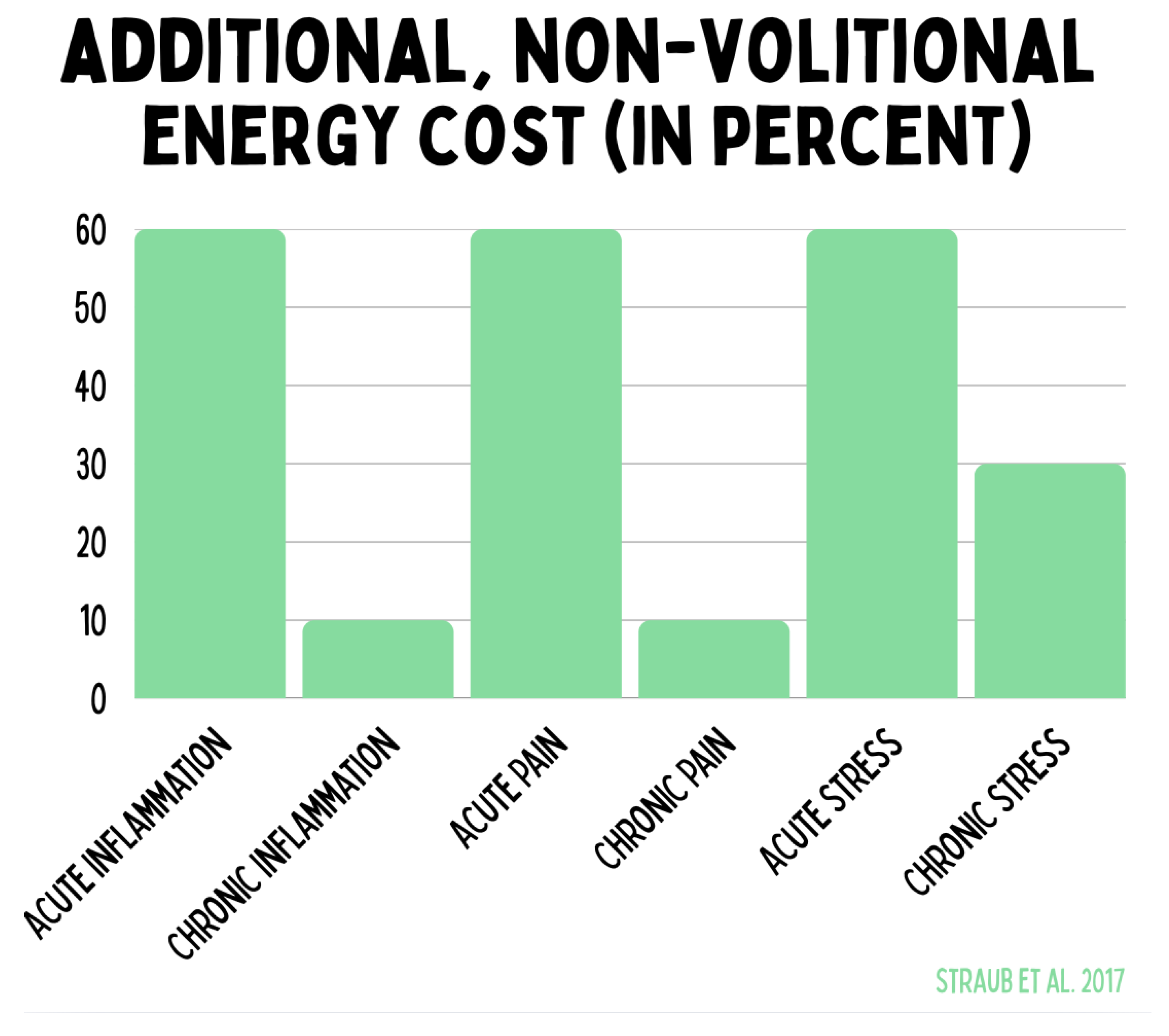

Figure 15.

The graphic quantifies the additional, involuntary energy expenditure caused by acute and chronic stress conditions. Acute inflammation, acute pain, and acute stress increase energy demand by up to 60 %. Chronic inflammation and chronic pain are significantly lower but represent a persistent burden. Chronic stress causes a sustained additional energy consumption of approximately 30 %. These data illustrate that misallocations of energy in the context of stress and inflammatory processes bind substantial energetic resources and thereby contribute to the pathogenesis of chronic diseases.

Figure 15.

The graphic quantifies the additional, involuntary energy expenditure caused by acute and chronic stress conditions. Acute inflammation, acute pain, and acute stress increase energy demand by up to 60 %. Chronic inflammation and chronic pain are significantly lower but represent a persistent burden. Chronic stress causes a sustained additional energy consumption of approximately 30 %. These data illustrate that misallocations of energy in the context of stress and inflammatory processes bind substantial energetic resources and thereby contribute to the pathogenesis of chronic diseases.

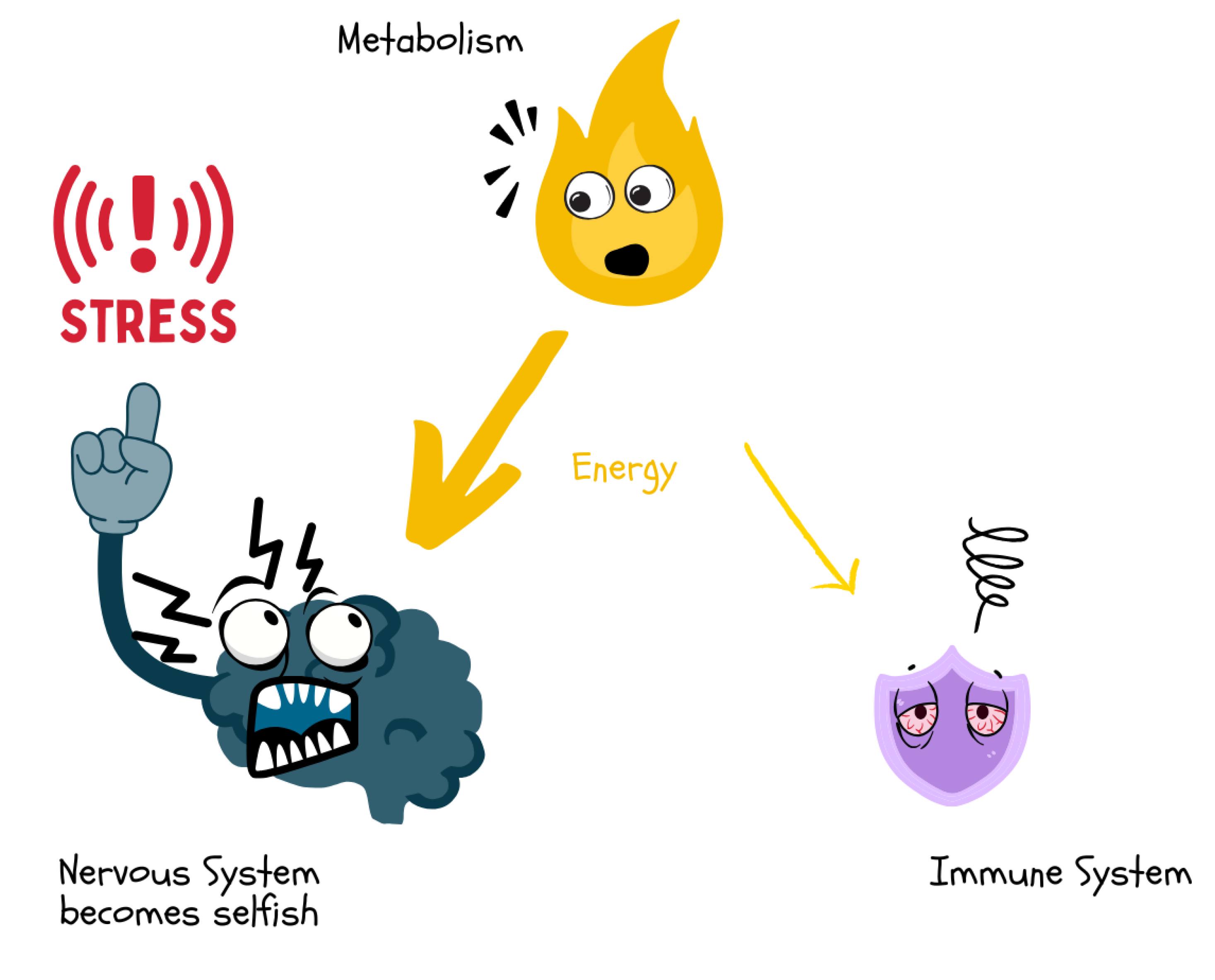

Furthermore, these regulatory systems are in constant energetic interaction. According to the theory of “selfish systems,” the nervous system, immune system, and metabolism do not act purely in harmonious cooperation but also pursue their own short-term energy optimization. Without central top-down control, they can “selfishly” withdraw energy from the others: for instance, when activated during infection, the immune system claims glucose and amino acids for the immune response via cytokine-mediated and metabolic signaling pathways — even at the expense of cognitive performance or anabolic processes.[

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66]

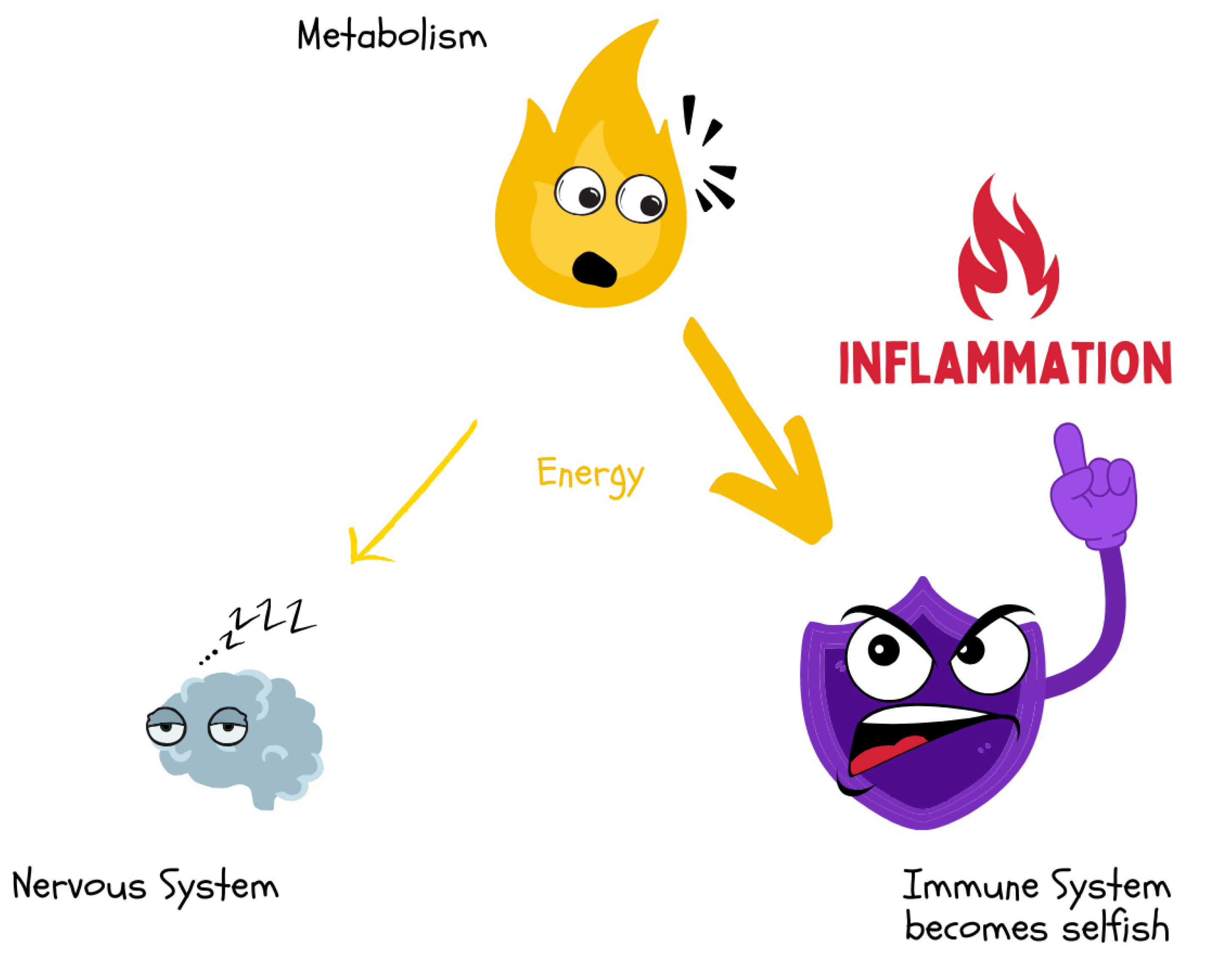

Figure 16.

Acute or chronic inflammatory processes lead to a “selfish” energy demand of the immune system. Through cytokine-mediated signaling pathways, energy is diverted from metabolism that would otherwise be available to the brain or other organs. This results in cognitive fatigue and reduced central nervous system function.

Figure 16.

Acute or chronic inflammatory processes lead to a “selfish” energy demand of the immune system. Through cytokine-mediated signaling pathways, energy is diverted from metabolism that would otherwise be available to the brain or other organs. This results in cognitive fatigue and reduced central nervous system function.

Analogously, under stress conditions, the nervous system mobilizes energy reserves via catecholamines and the HPA axis, thereby suppressing metabolism and immune responses. This bottom-up dynamic explains why chronic overactivation of individual systems (e.g., persistent stress response or inflammatory activity) can, over time, lead to systemic imbalance and energy depletion.[

17]

Figure 17.

Under stress, the brain demands a disproportionately high share of energy via sympathetic activation and glucocorticoids. This “selfish” prioritization of the central nervous system withdraws resources from the immune system, which can lead to reduced immune defense and increased susceptibility to infections.

Figure 17.

Under stress, the brain demands a disproportionately high share of energy via sympathetic activation and glucocorticoids. This “selfish” prioritization of the central nervous system withdraws resources from the immune system, which can lead to reduced immune defense and increased susceptibility to infections.

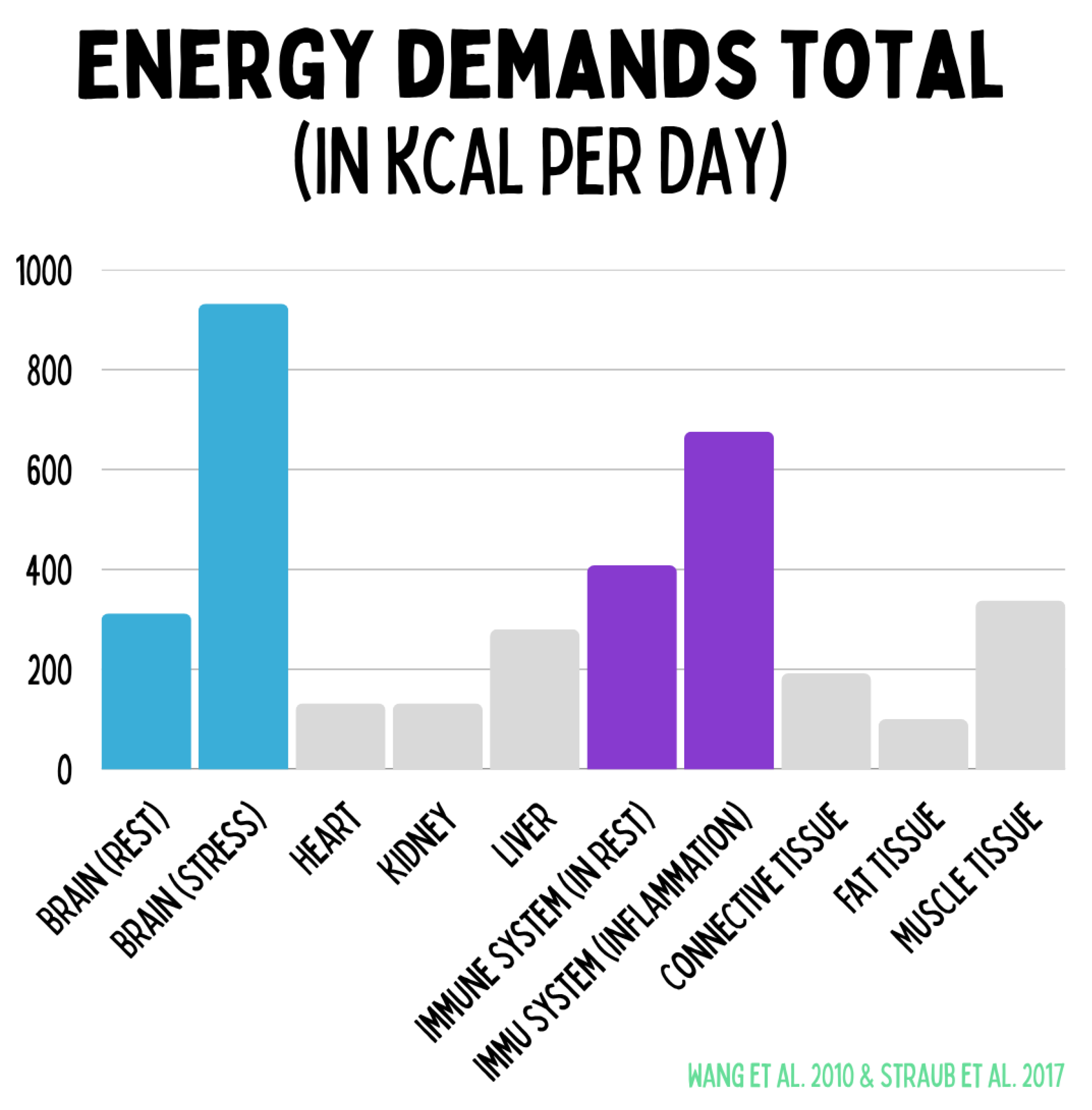

Rainer Straub et al. estimate, for example, that an activated immune system — as in chronic inflammation — can require up to 2000 kJ (∼ 480 kcal) of additional energy per day. This is accompanied by neuronal and metabolic shifts: pro-inflammatory cytokines and afferent nerve fibers signal an “energy alarm” to the brain, prompting the body to initiate an “energy appeal reaction” — a coordinated mobilization of additional energy carriers from storage depots. In this process, the sympathetic nervous system and HPA axis are activated to release glucose and fat reserves. Persistent misallocation (e.g., ongoing immune activation) can lead to pathological states: Straub lists conditions such as anorexia, insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, muscle wasting, and osteoporosis as consequences of an excessive, chronic redistribution of energy toward the immune system.[

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66]

Figure 18.

The figure illustrates the relative energy costs of key organ systems in resting metabolism. The brain consumes approximately 300 kcal/day at rest but up to 900 kcal/day under stress. The immune system requires roughly 400 kcal/day basally, rising to about 650 kcal/day during inflammation. The heart, kidneys, liver, and skeletal muscle contribute relatively constant shares, while adipose tissue accounts for only a minor portion. These data make clear that stress and immune activation represent the most variable energy consumers and decisively influence health, regeneration, and chronic disease progression.

Figure 18.

The figure illustrates the relative energy costs of key organ systems in resting metabolism. The brain consumes approximately 300 kcal/day at rest but up to 900 kcal/day under stress. The immune system requires roughly 400 kcal/day basally, rising to about 650 kcal/day during inflammation. The heart, kidneys, liver, and skeletal muscle contribute relatively constant shares, while adipose tissue accounts for only a minor portion. These data make clear that stress and immune activation represent the most variable energy consumers and decisively influence health, regeneration, and chronic disease progression.

\textit{From an allostatic perspective, the brain itself should not be viewed primarily as an organ for thinking but as the central regulator of the body’s energetic economy. Its foremost task is to anticipate, allocate, and coordinate energy flow across systems to maintain metabolic stability. Thought and cognition are thus not the brain’s purpose but one of its strategies to achieve energetic balance. In this sense, cognitive activity—including rumination or repetitive negative thinking—can be interpreted as an attempt, albeit often maladaptive, to regain allostatic equilibrium under conditions of energetic dysregulation. Persistent or pathological thought patterns therefore indicate a disturbance in the underlying neuroenergetic regulation rather than purely psychological malfunction. This view is supported by recent models of allostatic control, which describe mental activity as a secondary phenomenon emerging from the brain’s continuous efforts to regulate internal energy needs.}[

33,

67]

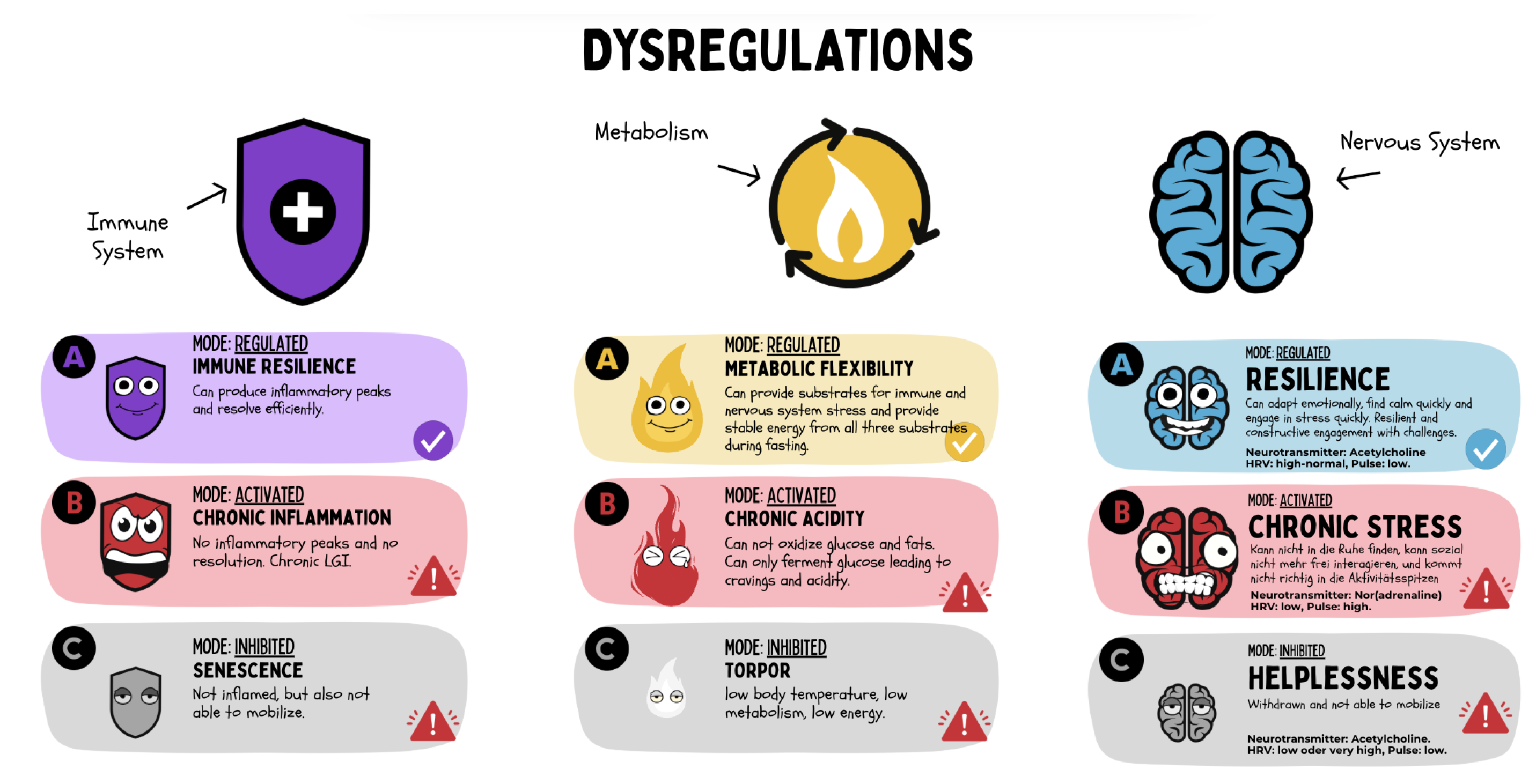

Regenerative medicine therefore views these three major systems as an integrative

bottom-up network of three selfish systems. Research in psychoneuroimmunology, immunometabolism, and neurometabolism confirms this close interconnection: stress (nervous system) affects inflammation (immune system) and metabolic processes, while inflammatory signals, in turn, modulate neuronal circuits and metabolic pathways. Mitochondria often lie at the center of these interactions, as they can alter their activity in response to stress hormones or have their efficiency impaired by cytokines. All three systems can operate in one of three functional states: (A) regulated/resilient, (B) activated/pathologically overdriven, or (C) inhibited/exhausted. Clinical symptoms, physiological markers, and molecular signals can be used to identify which of these states a patient’s subsystems are in. In this way, a functional regulatory signature emerges that describes an individual’s health status more precisely than classical diagnoses. Analogous to the polyvagal theory, which differentiates the autonomic nervous system into three regulatory modes, comparable three-stage patterns also appear in the immune system (e.g., resilience, chronic inflammation, senescence) and in metabolism (e.g., metabolic flexibility, acidosis, torpor).[

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77]

From this individual regulatory signature, regenerative medical diagnoses can be derived and targeted therapeutic pathways can be guided.

Figure 19.

The three central regulatory systems — the immune system, energy metabolism, and nervous system — can each operate in three functional states: regulated (A), activated/pathologically overdriven (B), or inhibited/exhausted (C). These dysregulations determine the interaction between systems and can be summarized through symptoms and markers into an individual functional regulatory signature, which forms the basis for regenerative medical diagnostics and therapy.

Figure 19.

The three central regulatory systems — the immune system, energy metabolism, and nervous system — can each operate in three functional states: regulated (A), activated/pathologically overdriven (B), or inhibited/exhausted (C). These dysregulations determine the interaction between systems and can be summarized through symptoms and markers into an individual functional regulatory signature, which forms the basis for regenerative medical diagnostics and therapy.

In summary, the nervous system, immune system, and metabolism work cooperatively as sensors and effectors of energy distribution. A disturbance in any of these areas can lead to global maladaptations — such as chronic inflammatory syndromes, metabolic diseases, or stress-related disorders. Regenerative medicine aims to restore balance within this network.

4.6. Health Is Adaptability

A guiding principle of regenerative medicine is that health is synonymous with adaptability. Health is not merely the absence of disease but the ability of an organism to flexibly respond to changing internal and external demands while maintaining equilibrium. This concept is supported by the theory of allostasis. Allostasis means “stability through change” — the active maintenance of balance through the dynamic adjustment of physiological parameters. In contrast to the static homeostasis model (which aims for fixed set points), allostasis emphasizes dynamism: organisms continuously adjust blood pressure, hormone levels, and metabolism in response to circadian rhythm, activity, and environment.

Bruce McEwen and John Wingfield described as early as 2003 that allostatic load represents the cumulative strain caused by chronic adaptive responses.[

58] When the allostatic load exceeds a critical threshold, allostatic overload occurs — a state in which the regulatory systems become exhausted and pathological consequences arise. Examples include persistently elevated cortisol under chronic stress, which over time leads to hypertension, immunosuppression, and other forms of damage — a sign that the system has lost its flexible adaptability and is trapped in a dysregulated “pseudo-equilibrium.”

A similar paradigm shift is taking place in the very definition of health. In 2011, Machteld Huber and colleagues proposed defining health as “the ability to adapt and self-manage,” replacing the static WHO definition.[

26] This “positive” health definition gained broad acceptance in health sciences. It illustrates that people can experience a high level of health despite chronic burdens or illnesses if they possess the flexibility and resilience to adapt — biologically, psychologically, physically, and socially — and to manage their situation effectively.

Figure 20.

Interconnection of the nervous, immune, and metabolic systems and their roles in chronic disease. The diagram illustrates the bidirectional communication between the three regulatory networks—nervous system, immune system, and metabolism—through cytokines, catecholamines, and energy substrates. Dysregulation within or between these systems can lead to distinct chronic pathologies, including neuroinflammation, autoimmunity, and metaflammation. The red field with question marks represents the emerging domain of neuroenergetic dysregulation, linking disturbances in neuronal energy metabolism to affective and neuropsychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder.

Figure 20.

Interconnection of the nervous, immune, and metabolic systems and their roles in chronic disease. The diagram illustrates the bidirectional communication between the three regulatory networks—nervous system, immune system, and metabolism—through cytokines, catecholamines, and energy substrates. Dysregulation within or between these systems can lead to distinct chronic pathologies, including neuroinflammation, autoimmunity, and metaflammation. The red field with question marks represents the emerging domain of neuroenergetic dysregulation, linking disturbances in neuronal energy metabolism to affective and neuropsychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder.

For clinical practice, this means that the measures of regenerative medicine aim to enhance adaptive capacity. These include increasing mitochondrial resilience (see Theses 1–3), promoting metabolic flexibility (smooth energy supply across anaerobic, aerobic, and ketogenic pathways), autonomic flexibility (e.g., dynamic balance of sympathetic and parasympathetic activity), and supporting immunological resilience (the ability to respond appropriately to antigens without falling into chronic inflammatory loops). A healthy system is characterized by variability and complexity of responses — for instance, a high heart rate variability at rest, indicating that the cardiovascular system can flexibly respond to breathing rhythm and other stimuli. Indeed, research shows that a higher degree of physiological variability (in heart rate, respiration, or neuroendocrine cycles) correlates with better health outcomes, whereas the loss of variability is a predictor of mortality. In short: rigidity is the enemy of vitality.[

78] Regenerative medicine therefore aims to strengthen the body’s allostatic systems so that they remain — or regain — flexibility and resilience. It should be noted here that flexibility represents the mere capacity for change, while resilience implies the existence of an adaptive reservoir that enables adaptive processes, which in turn allow the attainment of a higher level of energetic efficiency.

In this paradigm, stability is not understood as rigid persistence but as dynamic robustness — the ability to function in an orderly manner despite change and to repeatedly return to a healthy equilibrium after disturbances.

4.7. Health Is a Measurable Spectrum

Health and regenerative capacity can be assessed not only subjectively but also through objective markers. In regenerative medicine, metrics are used that correspond to the functional domains discussed above.

Figure 21.

Chronic health can be operationalized through objective biomarkers. In metabolism, elevated VO2max and reduced insulin concentrations indicate optimal metabolic flexibility. In the immune system, increased levels of pro-resolving mediators (resolvins) and low inflammatory markers characterize a balanced immune homeostasis. In the nervous system, increased heart rate variability (HRV) and a physiological cortisol rhythm reflect intact stress and regeneration capacity. Together, these parameters define the functional signature of sustainable resilience.

Figure 21.

Chronic health can be operationalized through objective biomarkers. In metabolism, elevated VO2max and reduced insulin concentrations indicate optimal metabolic flexibility. In the immune system, increased levels of pro-resolving mediators (resolvins) and low inflammatory markers characterize a balanced immune homeostasis. In the nervous system, increased heart rate variability (HRV) and a physiological cortisol rhythm reflect intact stress and regeneration capacity. Together, these parameters define the functional signature of sustainable resilience.

Here are some central markers of chronic health and their significance:

4.7.1. Cardiopulmonary and Mitochondrial Fitness (e.g., VO₂max):

Maximal oxygen uptake capacity during exertion is considered one of the best single predictors of cardiovascular health and overall mortality. A high VO₂max value reflects high mitochondrial capacity in muscle tissue and an efficient heart-lung system. It results from regular physical challenge (hormesis) combined with adequate recovery. In regenerative medicine, VO₂max is used both as a diagnostic indicator (the patient’s aerobic fitness level) and as a success criterion for interventions (e.g., regeneration programs).[

79,

80]

4.7.2. Insulin Sensitivity and Area Under the Chronic Insulin Curve (e.g., TyG, HOMA, Kraft Test):

These markers of glucose metabolism indicate how efficiently cells can absorb nutrients and how well energy metabolism is regulated. High insulin sensitivity (associated with low basal insulin levels) reflects metabolic health, whereas insulin resistance is frequently associated with chronic inflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction (e.g., in the context of metabolic syndrome). Regenerative approaches such as exercise, fasting, or anti-inflammatory nutrition aim to improve insulin sensitivity.[

81,

82,

83,

84]

4.7.3. Inflammation (e.g., hsCRP, TNF-):

High-sensitivity C-reactive protein is an established marker for systemic low-grade inflammation. Chronically elevated hsCRP levels indicate underlying inflammatory processes associated with numerous degenerative diseases (atherosclerosis, diabetes, depression, etc.). In regenerative medicine, lifestyle changes and targeted therapies aim to reduce this inflammatory milieu. Declining hsCRP and TNF-

levels indicate a successful shift toward an anti-inflammatory, regenerative internal state.[

82,

85,

86,

87]

4.7.4. Resolvins (Protectins, Maresins, etc.):

While classical markers such as CRP indicate inflammatory activity, pro-resolving mediators provide insight into the body’s capacity for active regulation of inflammation. Resolvins, protectins, and maresins are lipid mediators derived from omega-3 fatty acids that actively support tissue regeneration. They “resolve” inflammatory reactions, protect organs, and stimulate tissue repair. High levels of these mediators, or a strong endogenous capacity to produce them, are considered hallmarks of an effective healing process. Promoting endogenous resolvin production (e.g., through omega-3-rich nutrition) can therefore be used therapeutically.[

88,

89]

4.7.5. Heart Rate Variability (e.g., RMSSD, SDNN):

HRV — the beat-to-beat variability of heart rate — is a sensitive indicator of the activity and balance of the autonomic nervous system and vagal tone. A high, complex HRV at rest signals a high degree of parasympathetic tone and general physiological flexibility. Studies show that virtually every form of disease is associated with reduced HRV and that a stronger reduction in HRV correlates with higher mortality. Conversely, improvements in HRV (e.g., through breath training, stress reduction, or endurance exercise) are often accompanied by improvements in health status. In regenerative medicine, HRV therefore serves as an important longitudinal parameter to track the effects of interventions on autonomic balance.[

90,

91]

4.7.6. Area Under the Chronic Cortisol Curve (e.g., Cortisol Daily Rhythm):

A healthy cortisol rhythm is characterized by high levels in the morning (awakening response) and low levels in the evening, with an overall moderate cortisol output. Chronic stress or dysregulation of the HPA axis can flatten this rhythm (either persistently elevated or depleted cortisol). Restoring a normal cortisol curve is a key goal, as it is associated with better sleep, more stable mood, and stronger immune defense.[

92,

93]

Taken together, these markers represent a functional signature of successful energy allocation and mitohormesis. They make it possible to quantify the abstract concept of “health status” beyond the definition of “health is the absence of disease.” Importantly, these markers are not only monitoring parameters but also targets of intervention. Regenerative medicine always asks: How does this measure affect objective health markers? — and adjusts therapies accordingly.

4.8. Chronic Illness and Chronic Health Are Epigenetic Memories

Every short-term adaptive response of the body — whether to stress, nutrition, behavior, or environment — leaves traces in the regulatory memory of our cells. These traces manifest primarily in epigenetic markings: chemical modifications of DNA and histone proteins that regulate gene activity over the long term without altering the genetic sequence itself. Examples include DNA methylation or histone acetylation, which can turn genes on or off depending on their pattern.

Through epigenetic mechanisms, acute environmental influences can be “translated” into lasting changes in gene expression. It has been shown, for example, that learning situations or traumatic experiences can permanently reprogram the gene expression profile in brain cells — a kind of molecular memory that influences later behavior. Iva Zovkic and David Sweatt (2012) demonstrated that DNA methylation in the brain is crucial for the formation and stabilization of fear memory. Conversely, this means that repeated stimuli — whether positive (e.g., regular physical activity) or negative (e.g., chronic stress) — imprint cells in such a way that they become accustomed to a certain state and fix it epigenetically.[

94,

95]

Chronicity processes are not only epigenetically fixed but are also anchored through specific storage mechanisms within metabolism and the immune system. On the metabolic level, studies by Rainer Straub show that long-term adaptations manifest in the composition and incorporation of fatty acid sequences in membrane phospholipids and lipid stores. These changes act as an “energetic memory” that determines the availability of signaling lipids (e.g., arachidonic acid, omega-3 fatty acids) and thus shapes inflammatory and regenerative capacity over the long term. In parallel, the immune system establishes immunological memory through adaptive mechanisms: memory T and B cells encode past immune responses and influence whether inflammatory processes are efficiently resolved or become chronic. Finally, the nervous system complements this interplay through a cognitive-affective memory that reorganizes neuronal networks in response to stress and threat experiences, thereby conditioning the stress response.[

96,

97,

98,

99,

100] The concept of the

three memories — metabolic, immunological, and neuronal — formulated by Straub, thus describes the integrative foundation by which chronic disease states are maintained and reinforced. Regenerative medicine addresses precisely this point: through targeted interventions in all three memory systems, maladaptive storage can be released, enabling a return to dynamic resilience.

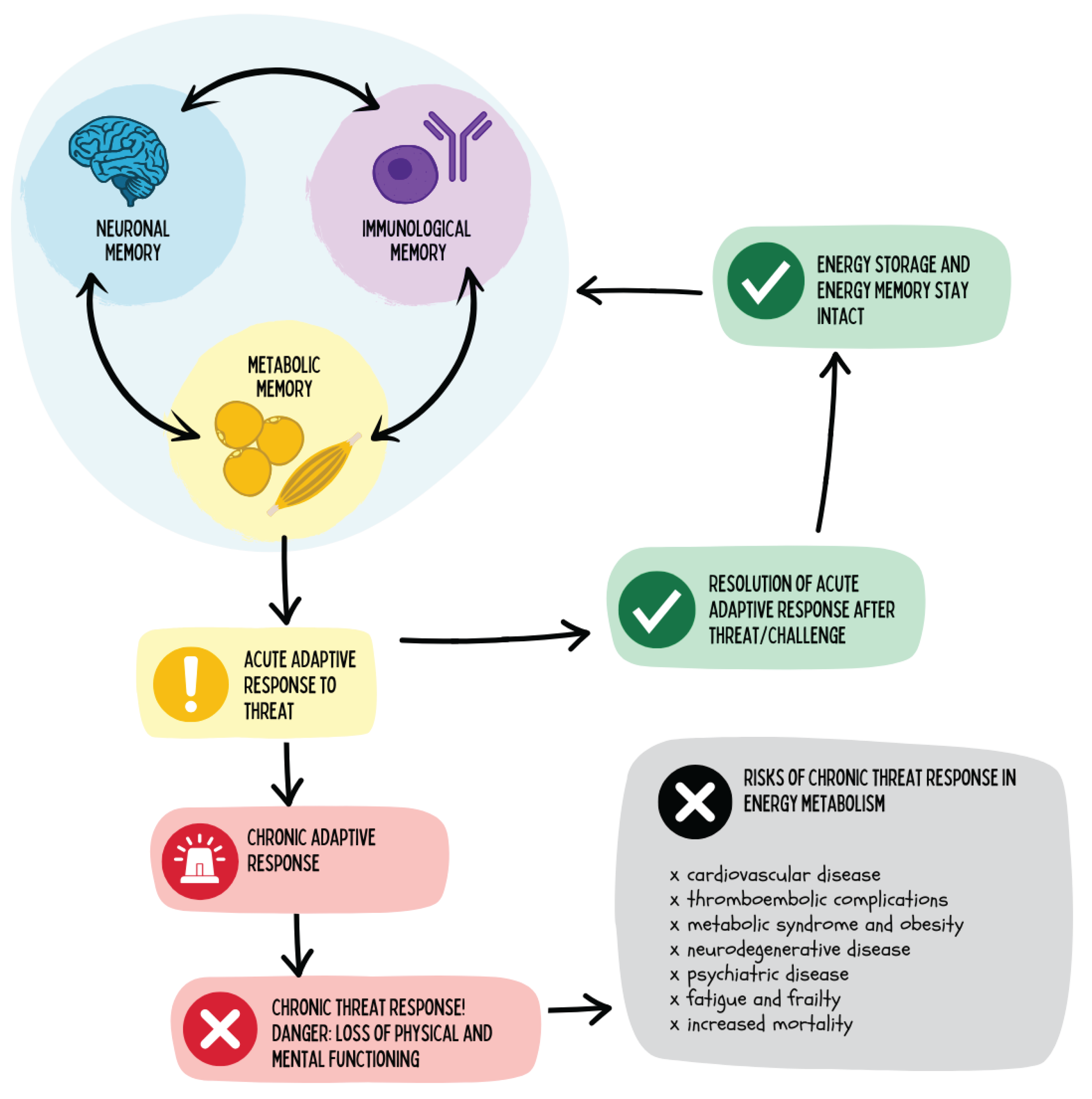

Figure 22.

The figure illustrates the role of mental and immunological memory in energy metabolism. Acute adaptive responses to threats are physiologically meaningful as long as they remain time-limited and cease once the stressor is removed. However, when these reactions become chronically activated, an energetic state of emergency arises, leading to a loss of physical and cognitive performance. This increases the risk for cardiovascular, metabolic, neurodegenerative, and psychiatric diseases as well as for frailty and premature mortality.

Figure 22.

The figure illustrates the role of mental and immunological memory in energy metabolism. Acute adaptive responses to threats are physiologically meaningful as long as they remain time-limited and cease once the stressor is removed. However, when these reactions become chronically activated, an energetic state of emergency arises, leading to a loss of physical and cognitive performance. This increases the risk for cardiovascular, metabolic, neurodegenerative, and psychiatric diseases as well as for frailty and premature mortality.

Applied to chronic health, this means that every repeated decision in daily life — whether it reinforces a healthy or unhealthy behavior — leaves traces in the biological system. Such habitual decisions generate recurring physiological signals that are relayed to the nucleus via mitochondrial communication (e.g., redox status, ROS signaling, ATP/ADP ratio). In this way, a molecular “impression” is formed: mitochondria translate experienced lifestyle patterns into epigenetic modifications that shape gene activity over the long term.

When the organism is regularly stimulated by salutogenic cues — such as movement, cold exposure, silence, or social connectedness — these signals stabilize as

epigenetic memories of resilience. The system “learns” to allocate energy efficiently and regeneratively. Conversely, chronically destructive choices — such as persistent stress activation, overnutrition, sleep deprivation, or social withdrawal — imprint an epigenetic signature of dysregulation. Mitochondria then emit danger signals (e.g., mitochondrial DAMPs) that amplify proinflammatory programs and shift entire gene networks into a defensive operating mode.[

46,

101,

102,

103,

104]

In Waddington’s metaphor of the

epigenetic landscape, this means that habits shape the valleys into which cells roll. Healthy decisions deepen resilient energetic pathways; unhealthy ones solidify pathological trajectories. Thus, “chronically ill” and “chronically healthy” become learned, energetically stored, and anatomically embedded states of lifestyle —

memories of our decisions.[

105]

This underscores the necessity of establishing early counterbalances before acute physiological reactions evolve into chronic, epigenetically consolidated states.

At the same time, recent evidence shows that chronicity is partially reversible: through targeted counter-conditioning — such as changes in lifestyle, behavior, and metabolic stimuli — as well as epigenetic interventions, the cellular memory can be rewritten toward regeneration.

Health and disease thus do not appear as static conditions but as dynamic learning processes at the cellular level, modulated by experience, metabolism, and mitochondrial communication. Regenerative medicine aims to actively influence these processes through interventions that activate regenerative gene programs (e.g., PGC-1\alpha, SIRT, Nrf2, and FOXO signaling pathways) and downregulate dysfunctional programs (e.g., NF-\kappaB or mTOR overactivation).

A deeper understanding of epigenetic code storage — that is, how DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs “translate” experiences — opens up future therapeutic perspectives targeting chronic diseases at their root: in the regulatory memory of the cells. After all, 80–90% of the etiology of chronic diseases is attributable to non-genetic factors.[

9]

Increasing evidence from small case series demonstrates that targeted lifestyle modification — and thereby alteration of the epigenetic and metabolic cellular environment — is not only preventive but can

functionally reverse manifest chronic diseases. This has been shown most impressively in the field of neurodegenerative diseases: In Dale Bredesen’s (UCLA) programs, which combine nutrition, exercise, sleep, fasting, stress regulation, and social interaction, patients with early Alzheimer’s disease were able to partially normalize their cognitive function. In the

ReCODE and

Apollo studies, up to 80% of participants showed objective improvements in cognitive scores — accompanied by epigenetic and metabolic normalization.[

106]

Similar findings have emerged in metabolic disorders. In the large-scale, prospective

Virta Health study, 60% of participants with type 2 diabetes achieved medication-free remission after two years — through a ketogenic diet, continuous coaching, and data feedback. Metabolomic and epigenetic analyses revealed significant changes in DNA methylation patterns, gene expression, and mitochondrial function, consistent with a “reprogramming” of energy metabolism.[

107]

In oncology as well, metabolic and epigenetic interventions are gaining attention. Dean Ornish and colleagues (2008) demonstrated in men with low-risk prostate cancer that a comprehensive lifestyle program significantly regulated over 500 genes in the tumor microenvironment within three months — downregulating oncogenic pathways and upregulating tumor-suppressive ones.[

108]

In multiple sclerosis, interventions such as the

Wahls Protocol indicate that a high-fat, nutrient-dense, inflammation-modulating diet combined with exercise and meditation may lead to improvements in fatigue, mobility, and quality of life. Recent work suggests that these effects may be mediated through changes in the epigenome and microbiome.[

109]

Similarly, in autoimmune and inflammation-associated diseases, clinical centers such as Paleomedicina (Budapest) report initial remissions — for example, in Crohn’s disease, type 1 diabetes, or epilepsy — through a strict ketogenic, anti-inflammatory diet that stabilizes mitochondrial signaling cascades and downregulates systemic inflammation.[

110,

111]

These examples demonstrate that habitual, systemic lifestyle changes can — via mitochondrial, metabolic, and epigenetic signaling pathways — intervene in profound disease processes and reverse their trajectory. Chronic disease is therefore not fate but the expression of a modifiable, learning biological system.

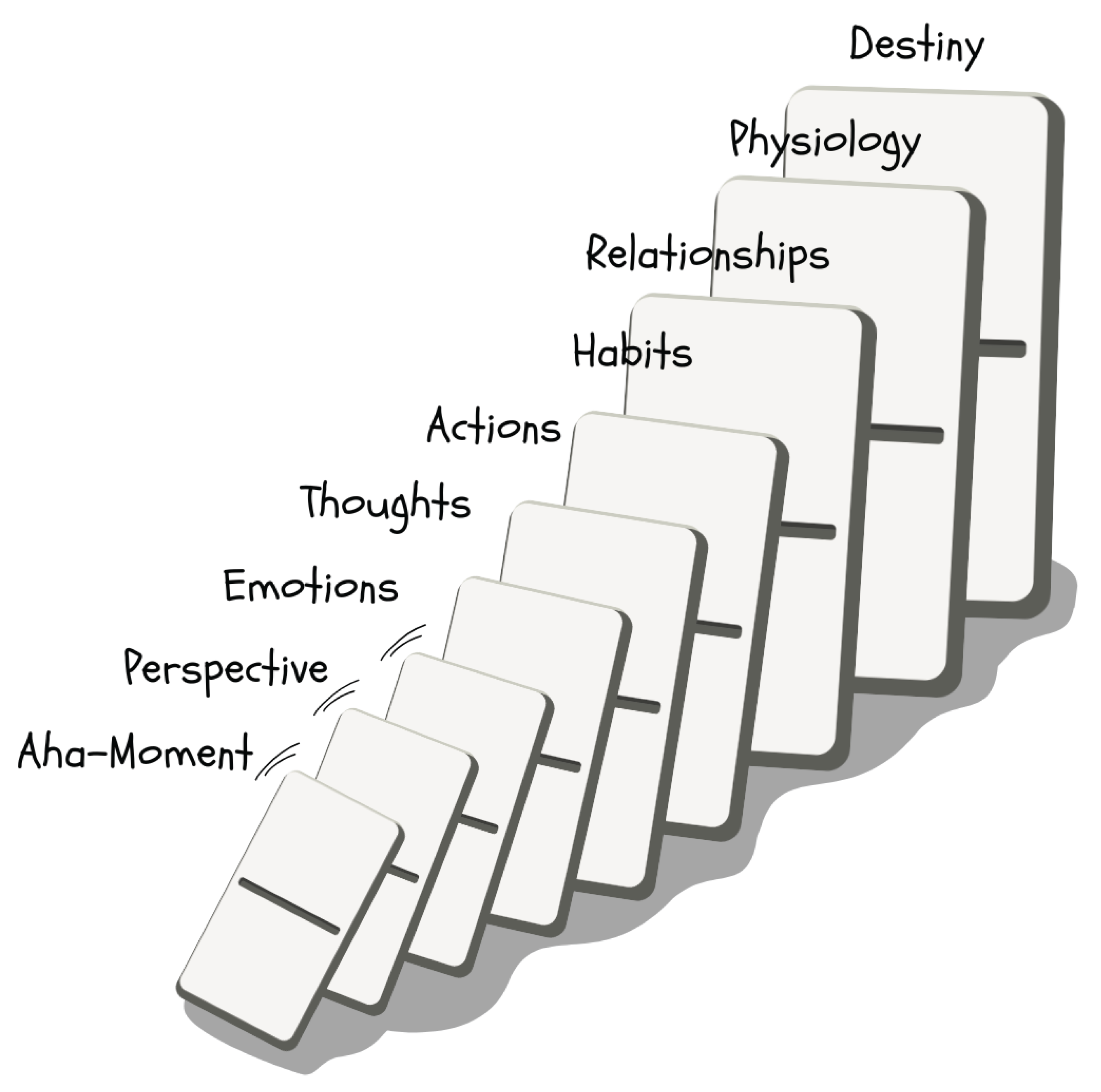

4.9. Habitual Decisions as Endogenous Pharmacology

A central field of application in regenerative medicine is lifestyle and behavioral intervention, based on the understanding that everyday habits exert cumulative biochemical and epigenetic effects. Nutrition, physical activity, sleep, cognitive engagement, and social interaction act not only through psychological or macroscopic mechanisms but also penetrate deeply into cellular regulatory networks — including mitochondrial signal transduction, hormonal axes, neuroimmunological communication, and epigenetic modification.

In this sense, habitual decisions must be understood as a form of endogenous pharmacology: they modulate signaling pathways, transcriptional profiles, and metabolite levels in ways that are pharmacologically equivalent in direction and target structure — yet more systemically integrated. The key difference lies in the fact that this “medication” is self-administered — consciously or unconsciously, day after day, through behavioral patterns that lead to stable physiological states.

Regenerative medicine deliberately harnesses this principle: it understands lifestyle as a modifiable therapeutic variable and empowers patients to use salutogenic habits as regulatory interventions — with the goal of reactivating the body’s endogenous self-healing programs and restoring chronically dysregulated systems to a state of adaptive resilience.

For didactic illustration, one often refers to the “seven doctors” available to us every day, each acting on different levels of healing:

Dr. Pharma – wisely used synthetic medications or supplements. In regenerative medicine, these are not rejected but seen as one building block among many — ideally applied synergistically with the other “doctors,” not as a sole solution, and always adapted to the temporal priorities of therapy.

Dr. Connection (Body–Mind) – nurturing the psychosomatic link through mindfulness, meditation, and positive emotions. This reduces stress, improves neuroendocrine regeneration, and enhances resilience.

Dr. Story (Cognition) – the inner narrative, our mindset, and sense-making. A constructive, meaningful life story fosters mental health and motivates healthy behavior.

Dr. Nutrition – a whole-food, anti-inflammatory diet. Micronutrients, fibers, and phytochemicals act like drugs at the molecular level (e.g., activation of AMPK by polyphenols, inhibition of NF-B by omega-3 fatty acids).

Dr. Breath – conscious breathing techniques and adequate exposure to fresh air. Breathing exercises can modulate the autonomic nervous system, increase HRV, and lower inflammation.

Dr. Nature – environmental stimuli such as cold, heat, infrared frequencies, magnetic fields, sunlight, and grounding. Moderate cold exposure activates brown fat and mitochondria (hormesis); near-infrared and sunlight promote mitohormesis, vitamin D synthesis, and circadian rhythm; grounding reduces electropositive stress.

Dr. Movement – physical activity as universal medicine. Regular endurance and strength training improve nearly every health marker (VO₂max, insulin sensitivity, HRV, mood) and reduce the risk of almost all chronic diseases.

Figure 23.

The figure illustrates the central lifestyle dimensions as the “doctors” of regenerative medicine. Through breathing, nutrition, movement, natural forces, connection, and story, targeted stimuli act on mitochondrial signaling pathways and modulate gene expression, hormesis, and energy allocation. Each dimension addresses specific biological pathways — from metabolic flexibility to stress regulation and psychosocial resilience — and thus functions as an integrative, epigenetically active “medication” for promoting chronic health.

Figure 23.

The figure illustrates the central lifestyle dimensions as the “doctors” of regenerative medicine. Through breathing, nutrition, movement, natural forces, connection, and story, targeted stimuli act on mitochondrial signaling pathways and modulate gene expression, hormesis, and energy allocation. Each dimension addresses specific biological pathways — from metabolic flexibility to stress regulation and psychosocial resilience — and thus functions as an integrative, epigenetically active “medication” for promoting chronic health.

Each of these doctors addresses specific epigenetic channels and regulatory circuits with their “medications.” The concept of the “seven doctors” serves as a reminder to medical professionals to look beyond the narrow scope of pharmacological monotherapies and to recognize the patient’s everyday life as a decisive therapeutic lever.

Each of these dimensions targets distinct biological pathways — from metabolic flexibility and stress regulation to psychosocial resilience — thereby functioning as an integrative, epigenetically active “medication” for promoting chronic health.

This underscores that complex natural stimuli are, in many cases, more advantageous than isolated pharmacological interventions. Every daily decision acts within the body like its own pharmacy. Regenerative medicine aims to shape these decisions consciously and salutogenically — to align epigenetic and physiological trajectories toward health.

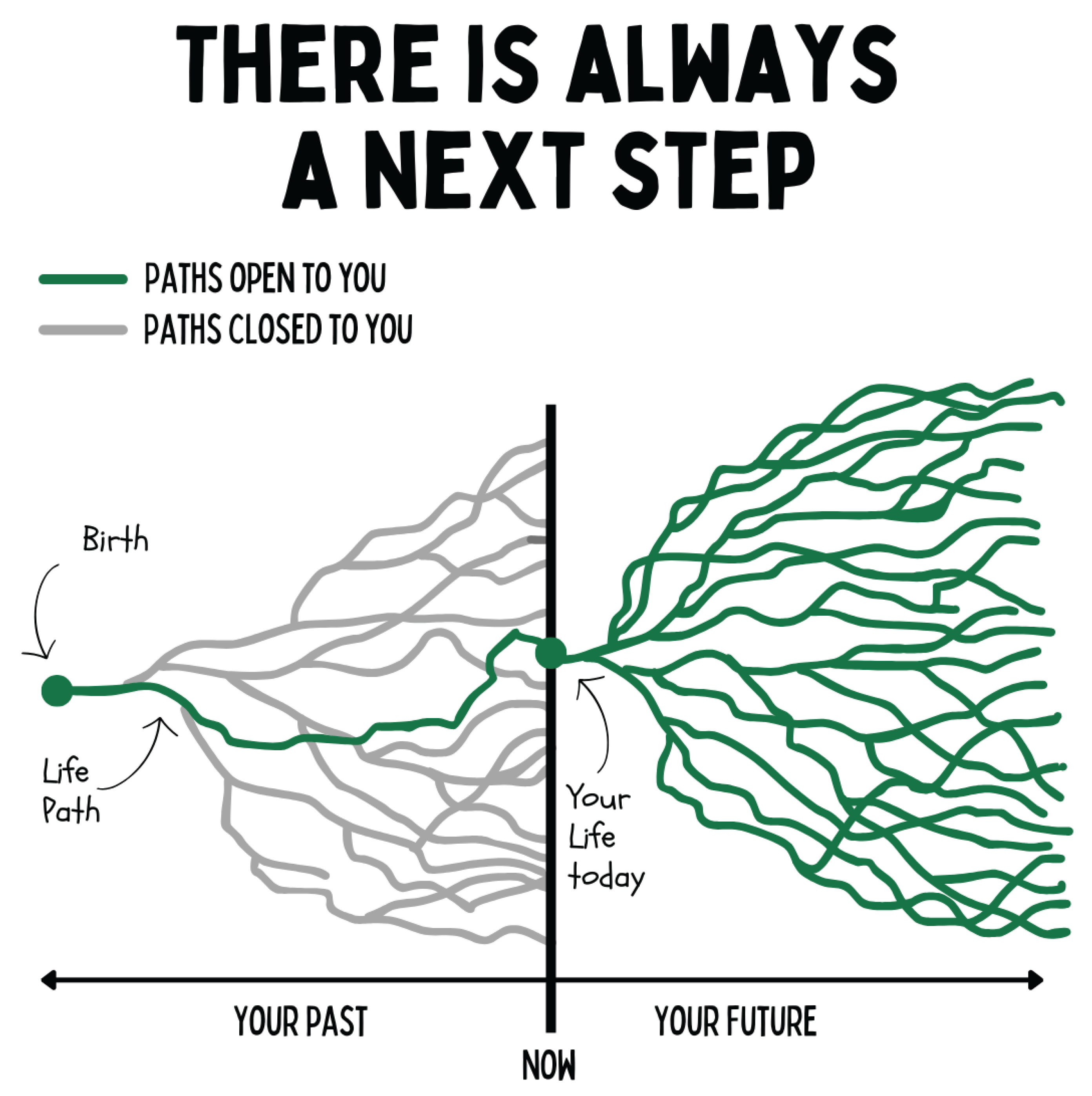

Figure 24.

The figure illustrates the dynamics of life paths as a bifurcating system. Each present moment opens multiple future developmental trajectories, while past options are irreversibly closed. In this model, health and disease do not emerge as static states but as the consequence of cumulative decisions that epigenetically shape biological, psychological, and social systems. Regenerative medicine focuses on maximizing the number of open, salutogenic pathways and expanding the scope for self-efficacy.

Figure 24.

The figure illustrates the dynamics of life paths as a bifurcating system. Each present moment opens multiple future developmental trajectories, while past options are irreversibly closed. In this model, health and disease do not emerge as static states but as the consequence of cumulative decisions that epigenetically shape biological, psychological, and social systems. Regenerative medicine focuses on maximizing the number of open, salutogenic pathways and expanding the scope for self-efficacy.

4.10. Regeneration as a Hero’s Journey

Modern regenerative medicine has recognized that the scientific foundations of health are already well known. Numerous studies have demonstrated which epigenetic and metabolic pathways are activated by nutrition, movement, sleep, light, cold exposure, mindfulness, or social connectedness — and how these promote cellular resilience, resolution of inflammation, and neuroendocrine balance.

The biological mechanisms of healing are understood better today than ever before — the real challenge lies in translating this knowledge effectively into sustainable practice and lifestyle.

Thus, the focus shifts from biomedical discovery to behavioral integration. The core problem of the modern healthcare system is no longer the lack of knowledge, but the lack of transfer competence: How can scientifically validated mechanisms be translated into people’s daily lives — effectively, economically, and at scale?

This is precisely where the field of regenerative medicine lies: it understands itself as a translational discipline between the laboratory and everyday life. The decisive factor in this model is the medical mentor — the “missing piece” between research and behavior.

The mentor bridges biomedical knowledge with behavioral psychology and guides individuals in activating their physiological self-healing systems. They translate complex molecular relationships into tangible, actionable steps, thus creating the foundation for genuine compliance and sustainable transformation.

Regenerative medicine integrates insights from Salutogenesis (Antonovsky), Motivational Interviewing (Miller & Rollnick), Behavioral Design, and Neuropsychology. It recognizes that long-term behavioral change succeeds only when a person:

understands why a measure works (comprehensibility),

experiences that it is manageable (manageability),

and finds personal meaning in it (meaningfulness).

The mentor acts as a bridge between systems — between biomedical evidence and individual experience, between theoretical knowledge and lived practice. They create coherence, motivate through relationship and context, and translate scientific principles into narrative and physiological effectiveness.

From this perspective, regeneration becomes the hero’s journey of self-efficacy: the patient is not the object of treatment but the subject of a learning and developmental process occurring simultaneously on biological, psychological, and social levels.

The mentor’s role is to structure, mirror, and stabilize this process — as an integrative catalyst connecting science, behavior, and system economics.

Understood in this way, regenerative medicine is not merely a medical specialty but a new organizational model for health: evidence-based in biology, behaviorally oriented in application, and economically viable in scale.

4.10.1. Recovered Individuals as Heroes of Regenerative Medicine