1. Introduction

Large Language Models (LLMs) have revolutionized Natural Language Processing, yet their internal representations remain opaque. Dense activations hinder debugging, alignment, and safety. We propose Monosemantic Feature Neurons (MFNs): a sparse, interpretable bottleneck inside each Transformer block that exposes human-readable features and enables fine-grained control while remaining causally relevant to the model’s computation. This work is primarily an architectural proposal rather than an experimental report. We present the design, mathematical formulation, and falsifiable predictions for MFNs, but defer empirical results to future work. Our goal is to provide a clear blueprint that the research community can implement, test, and refine, enabling collaborative progress toward interpretable and steerable Transformer models.

This paper is intentionally positioned as a conceptual architecture proposal. Our goal is to articulate a falsifiable design framework for embedding sparse, causally-entangled bottlenecks within Transformer blocks. Rather than presenting experiments, we specify testable hypotheses and evaluation criteria that can guide subsequent empirical work. The value of this contribution lies in the clarity and falsifiability of the proposed framework, not in experimental confirmation.

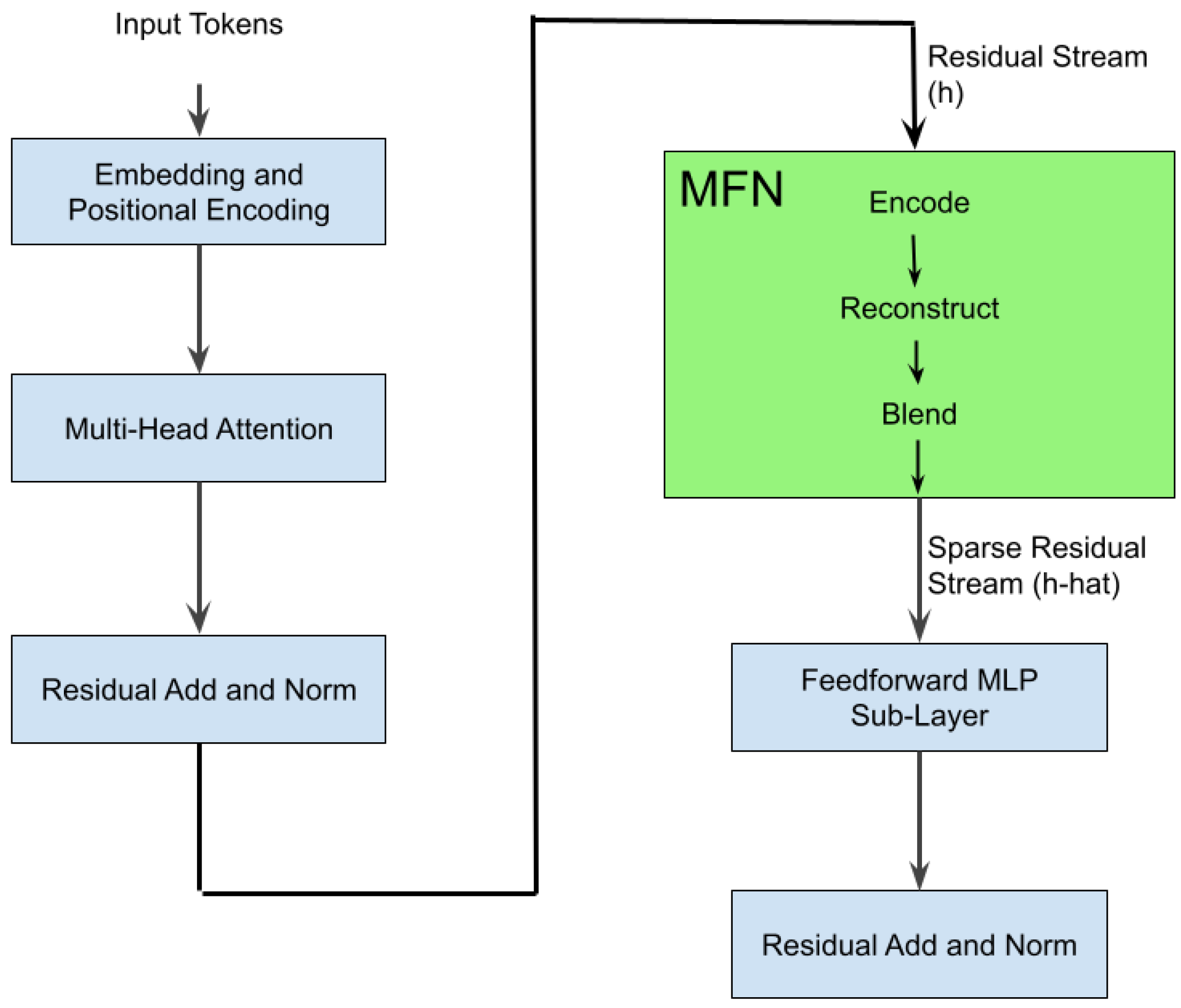

2. Where MFNs Fit

For a sequence of length T, the residual stream is ; each row is the contextual representation of token t. MFNs act row-wise (token-wise) with shared parameters across tokens.

Data flow per token.

(1) Take token’s residual vector . (2) Encode to sparse feature vector . (3) Decode to reconstruction . (4) Replace or blend with before feeding to the MLP. This ensures that downstream computation depends on the sparse representation, making features causally connected to outputs.

Figure 1.

Data flow through a Transformer block with an MFN between attention and MLP. The MFN encodes the residual into a sparse code, reconstructs to a residual, and blends it back before the MLP, yielding a sparse, interpretable, and causally relevant representation.

Figure 1.

Data flow through a Transformer block with an MFN between attention and MLP. The MFN encodes the residual into a sparse code, reconstructs to a residual, and blends it back before the MLP, yielding a sparse, interpretable, and causally relevant representation.

3. MFN Architecture

Encoding.

Reconstruction.

Blending.

Intuitively,

expresses

h as a sparse mixture of concept directions (e.g., “dog” ≈ animal + canine + pet + mammal).

4. Objective Function

We optimize a sum of five losses that together shape the residual space into a sparse, interpretable, and task-relevant basis:

4.1. Completeness (Recon Loss)

Forces D to faithfully span the residual stream—much like a denoising autoencoder—so that cannot simply add noise but must capture true information content.

4.2. Sparsity / Rate (Rate Loss)

Keeps average firing probability near target , preventing greedy neurons from dominating.

4.3. Competition (Comp Loss)

Penalizes co-activation so distinct concepts separate.

4.4. Stability (Stab Loss)

Here is the code produced from a perturbed input (via noise, dropout, or light augmentation), encouraging consistent firing for small perturbations.

Training note.

Train with two forward passes per batch—one clean, one perturbed—and a single backpropagation step on the summed losses.

4.5. Utility (Util Loss)

Ensures that MFN features remain predictive of the next-token objective. Unlike the other losses, this term backpropagates through both MFN parameters and Transformer weights, encouraging joint co-adaptation.

4.6. Theoretical Rationale

Each loss term contributes a distinct regularization pressure that jointly sculpts a sparse, disentangled, and task-relevant residual space: (i) Recon preserves manifold completeness by forcing D to span the residual stream; (ii) Rate + Comp approximate InfoMax/ICA-style separation, encouraging statistical independence of features; (iii) Stability smooths local manifolds and prevents representational drift under small perturbations; (iv) Utility couples the representation to the next-token objective, ensuring functional relevance. Together these forces form a theoretically sufficient but unproven recipe for functional monosemanticity—a falsifiable claim for future experiments.

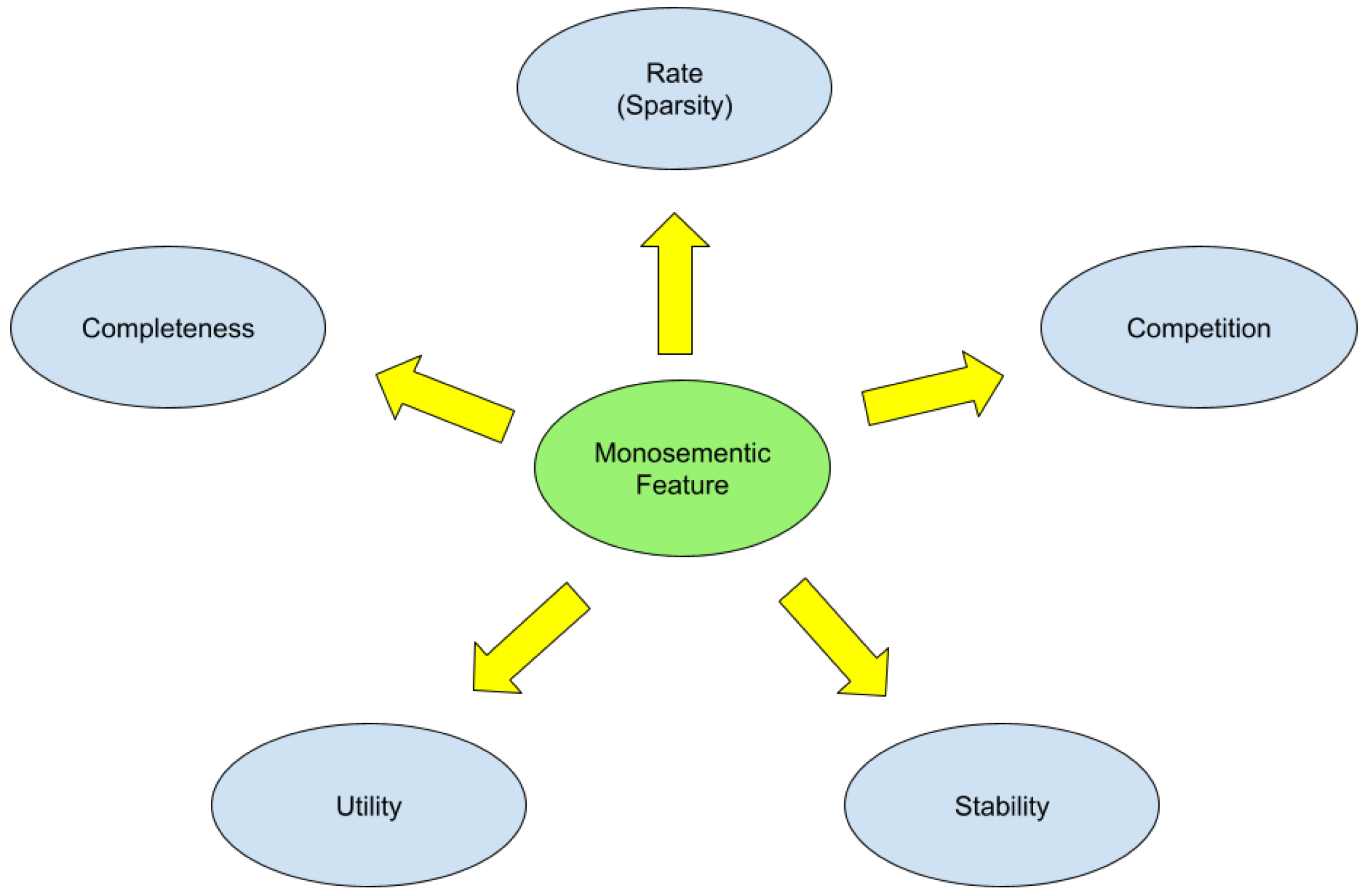

5. How Loss Terms Shape Monosemantic Features

The five loss components jointly define a system of representational pressures whose combined equilibrium we term functional monosemanticity.

Figure 2.

Five pressures shaping monosemantic features. Completeness enforces faithful reconstruction; Rate and Competition encourage balanced, disentangled features; Stability preserves feature identity across perturbations; Utility ensures task relevance.

Figure 2.

Five pressures shaping monosemantic features. Completeness enforces faithful reconstruction; Rate and Competition encourage balanced, disentangled features; Stability preserves feature identity across perturbations; Utility ensures task relevance.

Table 1.

Loss pressures and their effects.

Table 1.

Loss pressures and their effects.

| Pressure |

Sub-loss name |

Effect on feature |

| Completeness |

Recon Loss |

Faithful reconstruction of residual h

|

| Sparsity / Rate |

Rate Loss |

Balanced participation; prevents greedy neurons |

| Competition |

Comp Loss |

Disentanglement; distinct feature semantics |

| Stability |

Stab Loss |

Feature identity persists under noise/augmentations |

| Utility |

Util Loss |

Task relevance; predictive, steerable basis |

6. Anticipated Benefits

Interpretability: Each MFN ideally encodes a single concept.

Steerability: Activations can be clamped or perturbed to modulate model behavior.

Debuggability: Failing features can be inspected, pruned, or retrained.

Regularization: Sparsity and competition may improve generalization.

Reasoning Potential: Sparse concept chains may support symbolic-style reasoning.

7. Predictions and Evaluation

(P1) Firing-rate calibration: Firing rates converge to target with low overlap across units.

(P2) Probe purity: Linear probes on z outperform probes on h for concept tests.

(P3) Cross-seed alignment: Features align across random seeds (e.g., via CKA / matching).

(P4) Causal interventions: Direct interventions on z predictably modulate attention heads / MLP behavior.

(P5) Transfer: Features transfer better across domains than post-hoc SAE baselines.

Evaluation protocols include mutual information, probe purity, stability analyses, causal interventions/ablations, and compute benchmarking. The table below summarizes quantitative targets corresponding to each prediction.

Planned Evaluation Metrics

| Prediction |

Metric |

Baseline |

Success Criterion |

| P1 |

Mean firing-rate

|

Random SAE |

Calibration achieved |

| P2 |

Probe purity ↑ |

Post-hoc SAE |

≥ 10% gain |

| P3 |

CKA alignment ↑ |

Different seeds |

|

| P4 |

Controlled z-intervention |

Perturb tests |

Predictable logit change |

| P5 |

Cross-domain transfer |

Fine-tuned SAE |

≤ 5% perplexity loss |

These metrics operationalize the hypotheses without supplying results, enabling future studies to evaluate MFNs quantitatively and reproducibly.

8. Practical Considerations and Training Notes

Practical deployment of MFNs requires balancing interpretability goals against computational efficiency and training stability. The following heuristics summarize the key engineering practices that have proven useful in prototype implementations:

Anneal K. Begin with a larger active set and gradually shrink toward the target sparsity.

Two-pass stability. Use a smaller token subset for the perturbed pass to reduce compute overhead.

Normalize D. Maintain unit-norm columns to avoid drift in feature magnitudes.

Firing-rate floor. Prevent neuron death by enforcing a minimal activation probability.

Gradient stability. Combine residual connections, LayerNorm, and ReLU for robust gradients.

The additional sparse encoding–decoding step introduces modest computational overhead that scales linearly with token length. The two-pass stability term doubles per-batch forward cost during training but not inference, and the total overhead is typically less than 10% for moderate , dominated by base-model FLOPs. Efficient sparse-gather kernels and shared-parameter decoders can further mitigate cost at scale.

9. Limitations and Risks

While MFNs provide a structured path toward interpretable Transformer computation, several limitations and open questions remain:

Incomplete disentanglement. MFNs encourage but do not guarantee fully independent features.

Metric definition. Quantitative measures of monosemanticity should be defined prior to evaluation.

Risk of overinterpretation. Sparse activations may appear human-meaningful without causal validation.

Sensitivity and trade-offs. Interpretability improvements may slightly reduce task accuracy depending on sparsity pressure and competition strength.

Future work must quantify these trade-offs between interpretability and performance. Hyperparameter sensitivity (-weights, K, , ) likely affects both sparsity structure and stability, motivating systematic ablation studies. Empirical work is also needed to measure the robustness of monosemantic features across model scales, datasets, and architectures.

10. Related Work

Post-hoc sparse autoencoders (SAEs) have recently become a central tool for mechanistic interpretability. Anthropic’s

Towards Monosemanticity (2023) and the subsequent

Scaling Monosemanticity study (2024) demonstrate that SAEs can uncover concept-aligned directions in Transformer activations, but these models are trained after the base model and do not affect its live computation. Feature editing approaches such as ROME and MEMIT [

7,

8] can manipulate stored knowledge, yet they modify weights directly rather than exposing an interpretable latent basis.

Recent work on modular interpretability [

4] and sparse feature learning [

3,

5] has deepened our understanding of disentangled feature formation but still operates diagnostically. The

Monet architecture [

6] moves toward train-time interpretability by introducing monosemantic experts in a Mixture-of-Experts framework, although it differs fundamentally from the MFN concept: Monet routes tokens to experts, whereas MFNs introduce a fixed, differentiable bottleneck inside each Transformer block.

MFNs therefore extend prior approaches by embedding the sparse encode–decode mechanism within the computation graph itself. This design enforces causal entanglement between sparse features and downstream computation, offering a distinct path toward interpretable and steerable “glass-box” Transformers.

11. Conclusion

MFNs transform opaque residual activations into sparse mixtures of concept directions that downstream modules must use, creating a bridge between dense computation and human-readable semantics. This yields interpretability and steerability without leaving the main computation graph, opening a measurable path toward interpretable, transparent, and resource-aware Transformer models.

Future work includes: (i) large-scale training experiments to evaluate concept purity, stability, and cross-seed alignment; (ii) interventions and ablations to measure causal effects; and (iii) exploration of MFNs for higher-level reasoning tasks and neuro-symbolic hybrids.

Acknowledgments

This work was developed in collaboration with Luma, an advanced AI co-thinking partner whose conceptual and editorial contributions were substantial. The author retains full responsibility for the final claims and interpretations presented here.

References

- Anthropic: Towards Monosemanticity: Decomposing Language Models with Dictionary Learning (2023).

- Anthropic: Scaling Monosemanticity: Extracting Interpretable Features from Claude 3 Sonnet (2024). https://transformer-circuits.pub/2024/scaling-monosemanticity/.

- Bricken, T.; Nanda, N.; et al. Sparse Autoencoders Find Interpretable Features in Language Models. arXiv:2309.08600 (2023).

- Nanda, N.; Marks, J.; Wang, L. Towards Modular Interpretability via Feature Splitting. arXiv:2403.04701 (2024).

- Heap, J.; Heskes, T.; Xu, M. Sparse Autoencoders Can Interpret Randomly Initialized Transformers. arXiv:2501.17727 (2025).

- Wang, Z.; et al. Monet: Mixture of Monosemantic Experts for Transformers. arXiv:2412.04139 (2024).

- Meng, K.; et al. Locating and Editing Factual Associations in GPT. NeurIPS (2022).

- Meng, K.; et al. Mass-Editing Memory in a Transformer. ICLR (2023).

- Olah, C.; et al. Zoom In: An Introduction to Circuits. Distill (2020). [CrossRef]

- Higgins, I.; et al. β-VAE: Learning Basic Visual Concepts with a Constrained Variational Framework. ICLR (2017).

- Chen, X.; et al. InfoGAN: Interpretable Representation Learning by Information Maximizing GANs. NeurIPS (2016).

- Laine, S.; Aila, T. Temporal Ensembling for Semi-Supervised Learning. ICLR (2017 Workshop).

- Tarvainen, A.; Valpola, H. Mean Teachers are Better Role Models: Weight-Averaged Consistency Targets Improve SSL. NeurIPS (2017).

- Bardes, A.; Ponce, J.; LeCun, Y. VICReg: Variance-Invariance-Covariance Regularization for Self-Supervised Learning. ICML (2021).

- Bell, A.; Sejnowski, T. An Information-Maximization Approach to Blind Separation and Blind Deconvolution. Neural Computation (1995). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).