Submitted:

26 October 2025

Posted:

28 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction: A New Paradigm for Food Security

2. The Fragility of Incumbent Systems

2.1. Livestock Production: A Precarious House of Cards

2.2. Crop Production’s Vulnerabilities

2.3. Marine Fisheries: A Faltering Pillar

| System | Dependency on External Inputs | Vulnerability to Disease | Climate Sensitivity | Energy/Logistics Dependence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Livestock (Beef) | Very High (Feed, Vet) | Very High (CAFOs) | High (Drought) | High (Feed transport, housing) |

| Grain Crops | High (Fertilizer, Pesticides) | Medium (Monocultures) | Very High (Drought, Flood) | Medium (Harvesting, processing) |

| Marine Fisheries | Medium (Fuel, Vessels) | Low (Wild stocks) | High (Ocean warming) | Very High (Fuel, cold chain) |

| Lake Aquaculture | Low (Natural food) | Medium (Controlled) | Medium (Buffered) | Very Low (Static asset) |

3. The Resilient Superiority of Lake Aquaculture

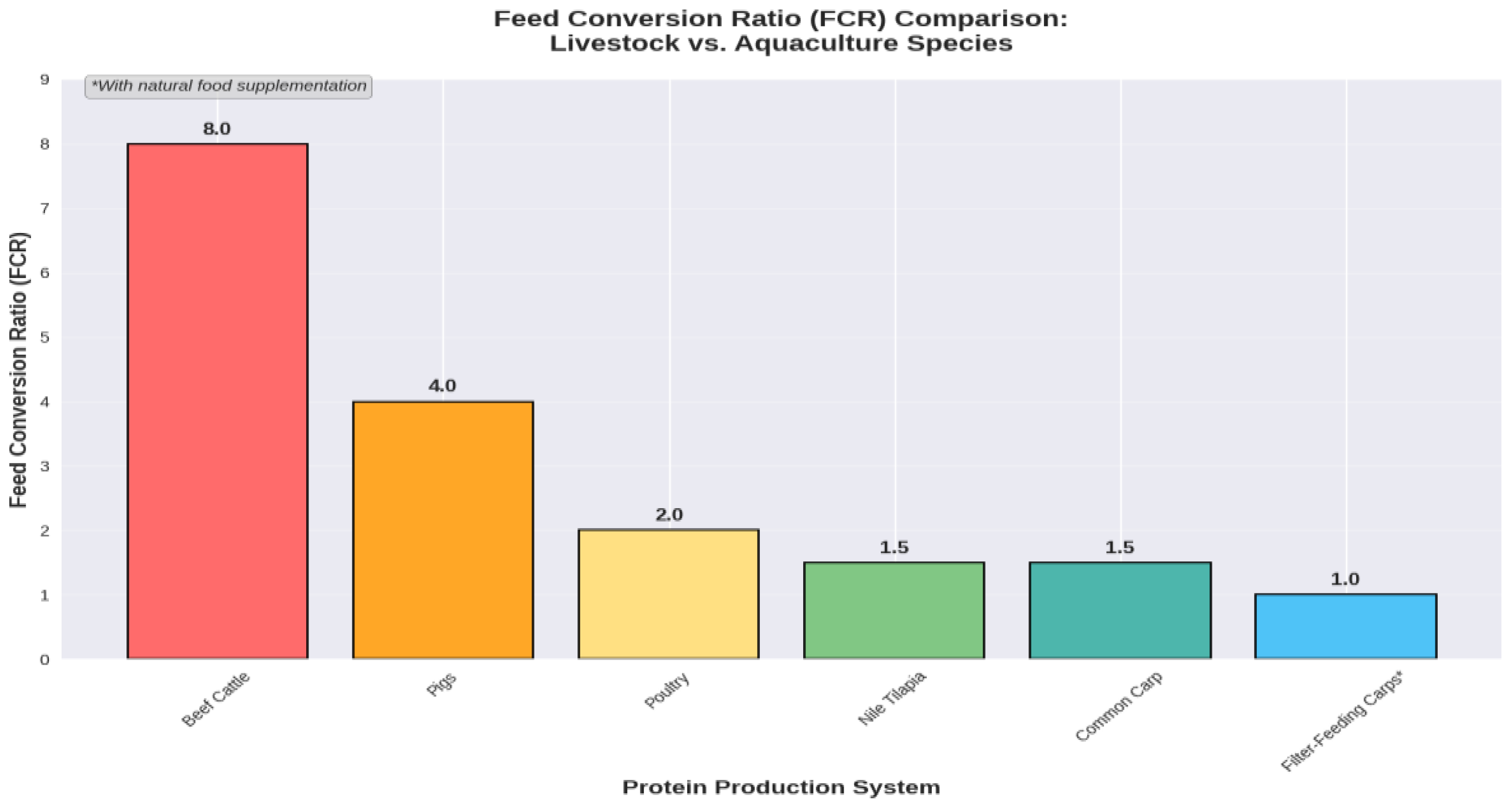

3.1. Unmatched Resource Efficiency

3.2. Logistical Simplicity and “Live Storage”

3.3. Ecological Buffering Capacity

3.4. Non-Competitive Land Use

4. Implementation: Species and Management for a Post-Catastrophe World

4.1. Species Selection: The Principle of Hardiness

- Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio): Extremely hardy, bottom-feeding omnivore (Rakus et al., 2017).

- Silver & Bighead Carp: Filter-feeders that harvest plankton directly, requiring no processed feed (Liu et al., 2018).

- Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus): Fast-growing, prolific, and disease-resistant omnivore (El-Sayed, 2019).

- Grass Carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella): Dedicated herbivore for weed control.

- African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus): Tolerant of poor water quality and can consume waste products (Hossain et al., 2021).

| Species | Trophic Niche | Key Resilient Traits | Potential Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common Carp | Benthic Omnivore | Tolerance to low O2, poor water quality | Can stir sediments |

| Silver Carp | Phytoplankton Filter Feeder | Harvests base of food web; no feed needed | Sensitive to low plankton |

| Bighead Carp | Zooplankton Filter Feeder | Harvests secondary production; no feed needed | Sensitive to low plankton |

| Nile Tilapia | Omnivore | Fast growth, high fecundity, disease resistance | Sensitive to cold water |

| Grass Carp | Herbivore | Aquatic weed control | Requires plant biomass |

| African Catfish | Omnivore/Carnivore | Extreme tolerance to hypoxia, consumes waste | Higher trophic level |

4.2. Management Models: Extensivity and Polyculture

- Extensive/Semi-Intensive Models: Rely on natural productivity supplemented with agricultural wastes, eliminating dependency on commercial feeds (Edwards, 2015).

-

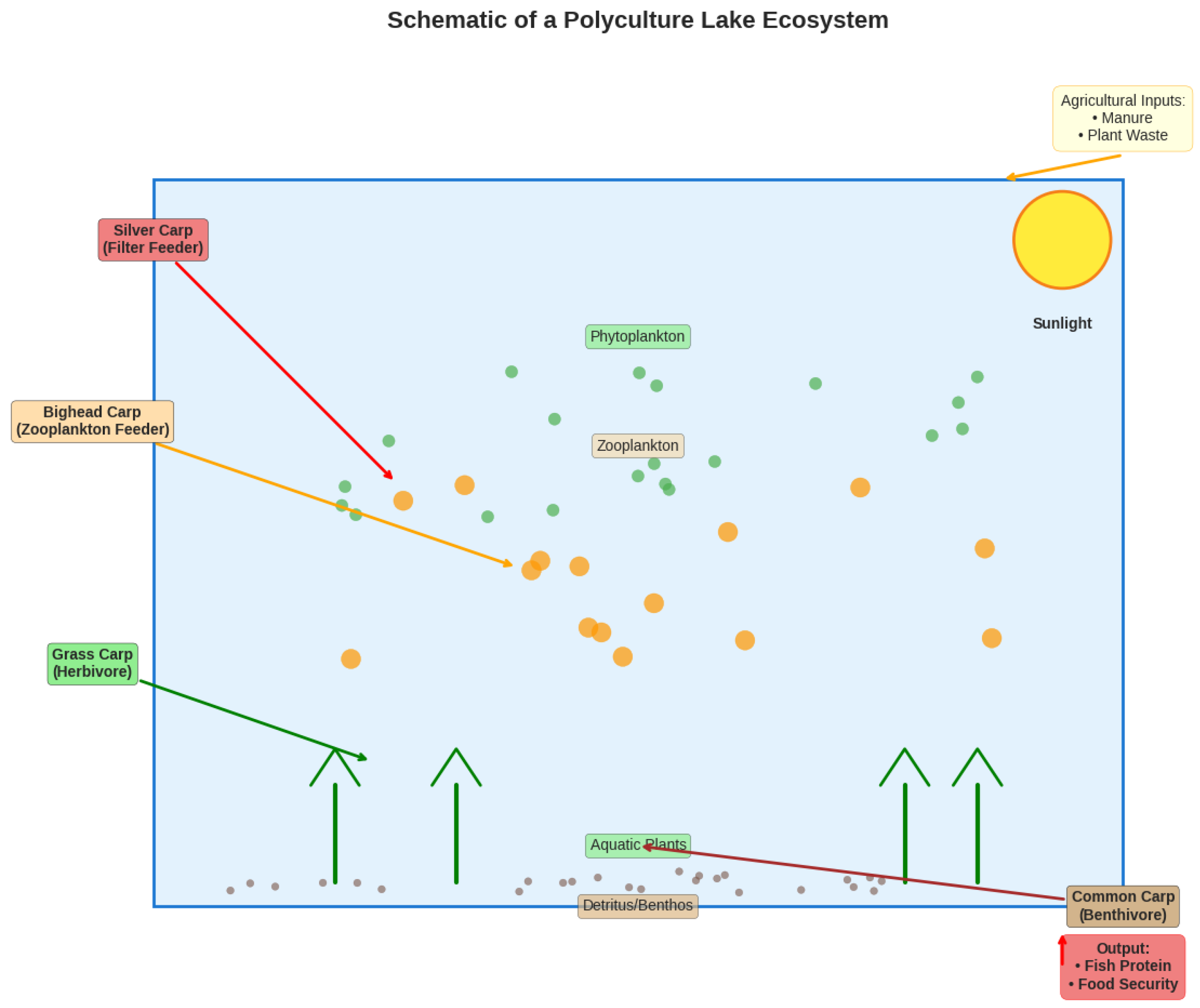

Polyculture: The synergistic cultivation of complementary species maximizes the use of the lake’s trophic niches, increasing total productivity and stability without increasing inputs (Milstein, 2019). A classic polyculture includes:

- Silver Carp (phytoplankton)

- Bighead Carp (zooplankton)

- Grass Carp (aquatic vegetation)

- Common Carp (benthic organisms/detritus)

4.3. Creating a Closed-Loop System: Integration with Agriculture

5. Overcoming Risks: A Proactive Strategy

5.1. Epidemiological Control

5.2. Germplasm Security

5.3. Preventing Ecological Degradation

5.4. Low-Energy Preservation

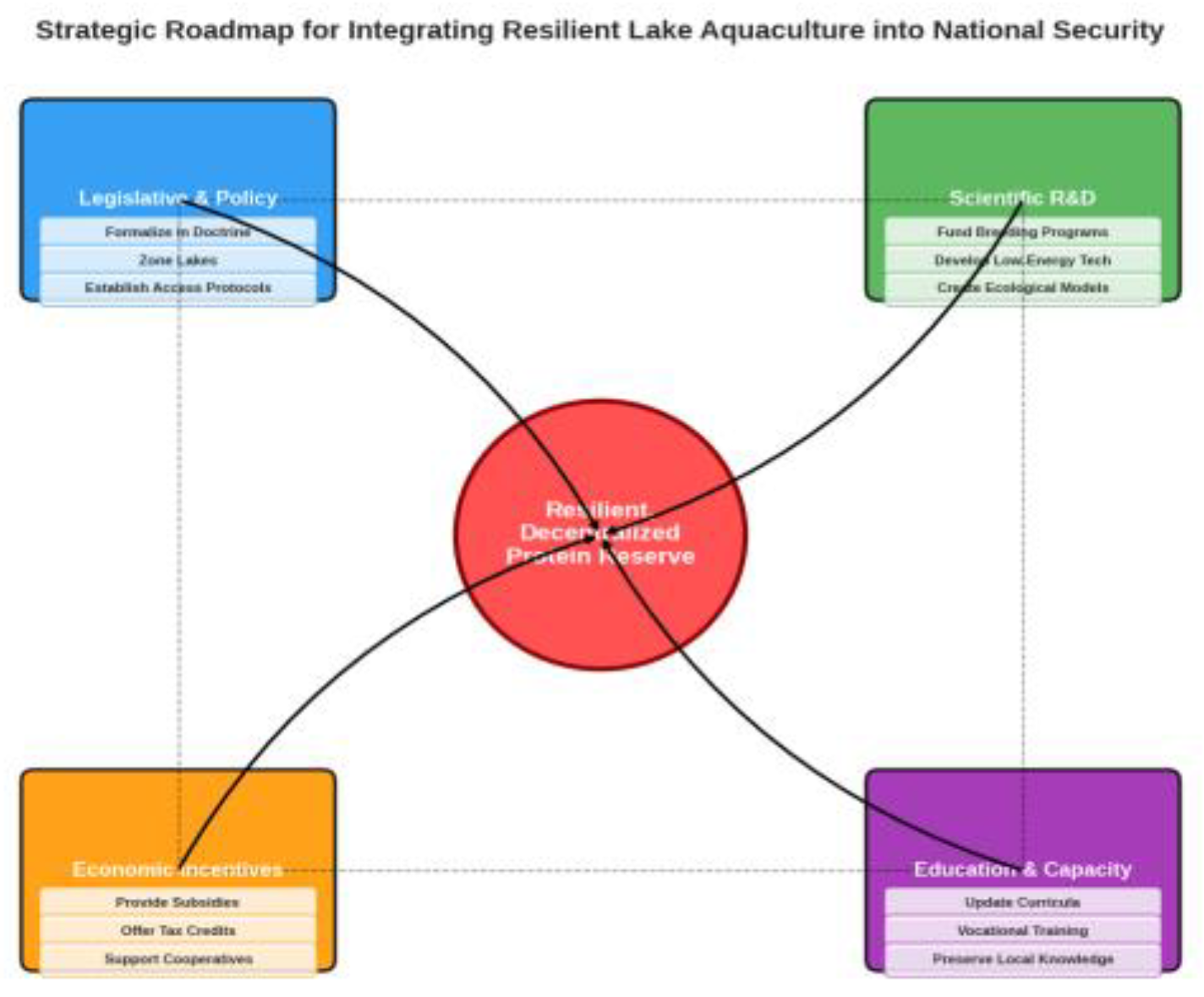

6. A Strategic Roadmap for National Integration

6.1. Legislative Action

6.2. Scientific R&D

6.3. Economic Incentives

6.4. Educational Capacity

- Legislative & Policy: “Formalize in Doctrine” -> “Zone Lakes” -> “Establish Access Protocols”

- Scientific R&D: “Fund Breeding Programs” -> “Develop Low-Energy Tech” -> “Create Ecological Models”

- Economic Incentives: “Provide Subsidies” -> “Offer Tax Credits” -> “Support Cooperatives”

- Education & Capacity: “Update Curricula” -> “Vocational Training” -> “Preserve Local Knowledge”Arrows connect the pillars to a central outcome: “Resilient, Decentralized Protein Reserve”.)

7. Conclusion

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allison, E.H.; Horemans, B. Putting the principles of the Sustainable Livelihoods Approach into fisheries development policy and practice. Marine Policy 2006, 30, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béné, C.; Arthur, R.; Norbury, H.; Allison, E.H.; Beveridge, M.; Bush, S.; Williams, M. Contribution of fisheries and aquaculture to food security and poverty reduction: Assessing the current evidence. World Development 2016, 79, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogard, J.R.; Farook, S.; Marks, G.C.; Waid, J.; Belton, B.; Ali, M.; Thilsted, S.H. Higher fish but lower micronutrient intakes: Temporal changes in fish consumption from capture fisheries and aquaculture in Bangladesh. PloS One 2017, 12, e0175098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, C.E.; Tucker, C.S. (2014). Handbook for Aquaculture Water Quality. Pond Aquaculture Research and Development Foundation.

- Boyd, C.E.; D’Abramo, L.R.; Glencross, B.D.; Huyben, D.C.; Juarez, L.M.; Lockwood, G.S.; Valenti, W.C. Achieving sustainable aquaculture: Historical and current perspectives and future needs and challenges. Journal of the World Aquaculture Society 2020, 51, 578–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugère, C.; Troell, M.; Beveridge, M. Aquaculture and the future of food. Nature Food 2019, 1, 330–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doe, P.E. (2022). Fish drying. In Seafood Processing: Technology, Quality and Safety (pp. 61–80). Wiley-Blackwell. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, P. Aquaculture environment interactions: Past, present and likely future trends. Aquaculture 2015, 447, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, A.F.M. (2019). Tilapia culture. Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- FAO (2020). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020. Sustainability in action. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. [CrossRef]

- FAO (2021). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021. Transforming food systems for food security, improved nutrition and affordable healthy diets for all. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. [CrossRef]

- Ficke, A.D.; Myrick, C.A.; Hansen, L.J. Potential impacts of global climate change on freshwater fisheries. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries 2007, 17, 581–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Free, C.M.; Thorson, J.T.; Pinsky, M.L.; Oken, K.L.; Wiedenmann, J.; Jensen, O.P. Impacts of historical warming on marine fisheries production. Science 2019, 363, 979–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaly, A.E.; Dave, D.; Budge, S.; Brooks, M.S. Fish spoilage mechanisms and preservation techniques: A review. American Journal of Applied Sciences 2010, 7, 859–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, M.J.; Greko, C.; Wallinga, D.B.; Beran, G.W.; Riley, D.G.; Thorne, P.S. The potential role of concentrated animal feeding operations in infectious disease epidemics and antibiotic resistance. Environmental Health Perspectives 2007, 115, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfray, H.C. J., Beddington, J.R., Crute, I.R., Haddad, L., Lawrence, D., Muir, J.F., Toulmin, C. Food security: The challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science 2010, 327, 812–818. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.A.R.; Das, I.; Genevier, L.; Hazra, S.; Rahman, M. Biology and aquaculture of African catfish (Clarias gariepinus) and Asian catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus). Reviews in Aquaculture 2021, 13, 1973–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, K.; Bureau, D.P. Exploring the possibility of quantifying the effects of using alternative ingredients in fish feeds on the environmental performance of aquaculture systems. Aquaculture 2012, 356, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaba, T. Dasatinib and quercetin: short-term simultaneous administration yields senolytic effect in humans. Issues and Developments in Medicine and Medical Research 2022, 2, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, B.A.; Grace, D.; Kock, R.; Alonso, S.; Rushton, J.; Said, M.Y.; Pfeiffer, D.U. Zoonosis emergence linked to agricultural intensification and environmental change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2013, 110, 8399–8404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laborde, D.; Martin, W.; Swinnen, J.; Vos, R. COVID-19 risks to global food security. Science 2020, 369, 500–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesk, C.; Rowhani, P.; Ramankutty, N. Influence of extreme weather disasters on global crop production. Nature 2016, 529, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, G.; Sun, G.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Y. The synergistic effects of polyculture on the ecosystem services of aquaculture ponds. Aquaculture Research 2018, 49, 3044–3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.E.; Neira, R.; Yáñez, J.M. Applications of genome-wide selection in aquaculture breeding programs. Aquaculture Reports 2021, 21, 100869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, M.M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. A global assessment of the water footprint of farm animal products. Ecosystems 2012, 15, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milstein, A. (2019). Polyculture in aquaculture. In Animal Agriculture (pp. 343–355). Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Nhan, D.K.; Phong, L.T.; Verdegem, M.J.C.; Duong, L.T.; Bosma, R.H.; Little, D.C. Integrated aquaculture-agriculture systems: A sustainable approach to rural development in the Mekong Delta. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakus, K.L.; Vanderplasschen, A.; Boutier, M. Cyprinid herpesvirus 3: an interesting virus for applied and fundamental research. Veterinary Research 2017, 48, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, K.; Brierley, A.; St-Hilaire, S. A review of biosecurity in aquaculture: The key to sustainable production. Reviews in Aquaculture 2023, 15, 516–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkemaladze, J. Reduction, proliferation, and differentiation defects of stem cells over time: a consequence of selective accumulation of old centrioles in the stem cells? Molecular Biology Reports 2023, 50, 2751–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tkemaladze, J. (2024). Editorial: Molecular mechanism of ageing and therapeutic advances through targeting glycative and oxidative stress. Front Pharmacol. 2024, 14, 1324446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tkemaladze, J. Through In Vitro Gametogenesis—Young Stem Cells. Longevity Horizon 2025, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Berge, H.F. M. , Hijbeek, R., van Loon, M.P., Rurinda, J., Tesfaye, K., Zingore, S., van Ittersum, M.K. Maize crop nutrient input requirements for food security in sub-Saharan Africa. Global Food Security 2019, 23, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez, J.M.; Houston, R.D.; Newman, S. Genetics and genomics of disease resistance in salmonid species. Frontiers in Genetics 2021, 12, 773–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Yi, Y.; Yakupitiyage, A.; Fitzsimmons, K. Comparison of nitrogen utilization efficiency in milkfish (Chanos chanos) and Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) in laboratory conditions. Aquaculture Reports 2020, 18, 100428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).