Submitted:

24 October 2025

Posted:

27 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Techno-Functional Properties of the Protein Extract

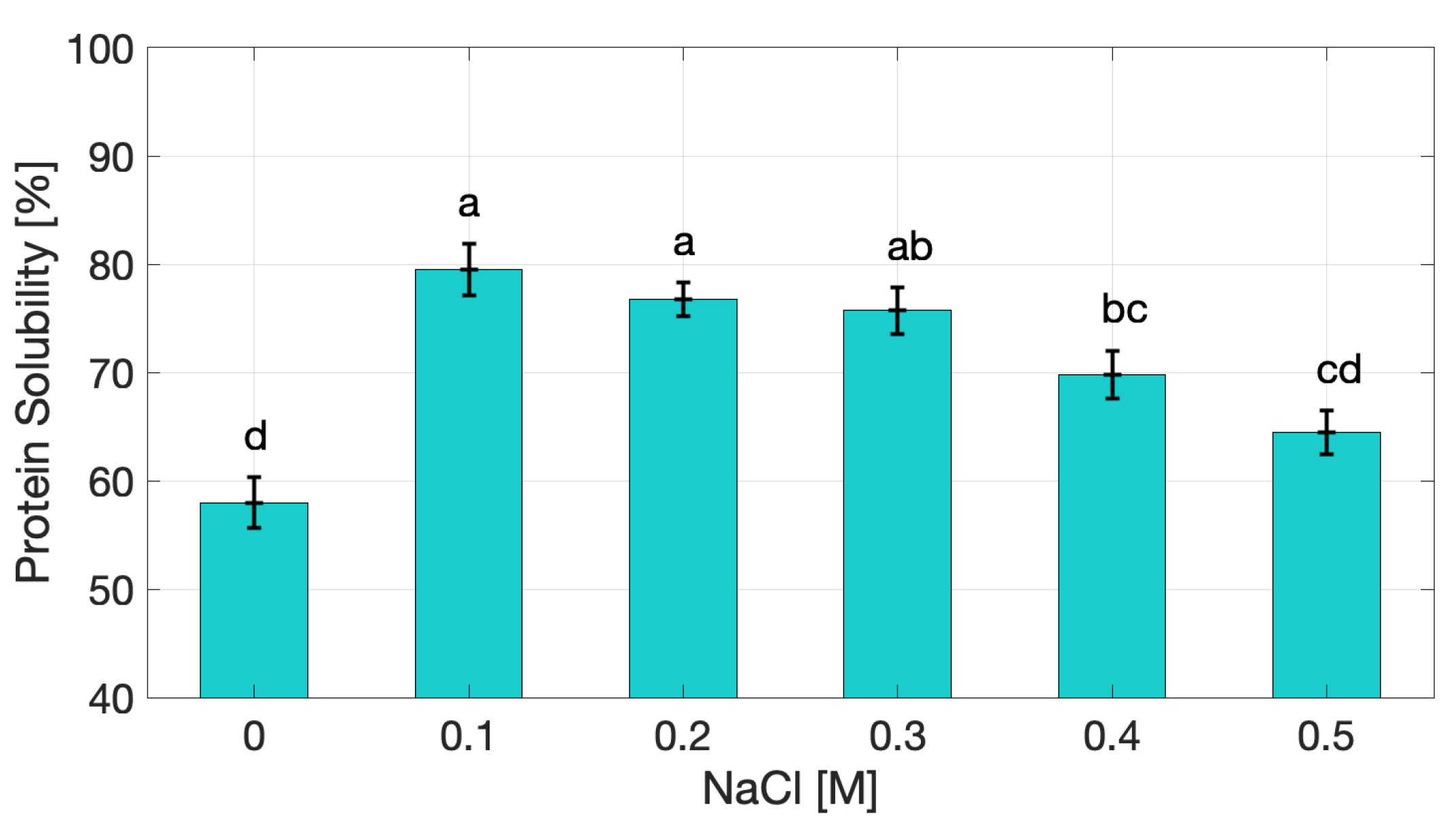

2.1.1. Protein Solubility

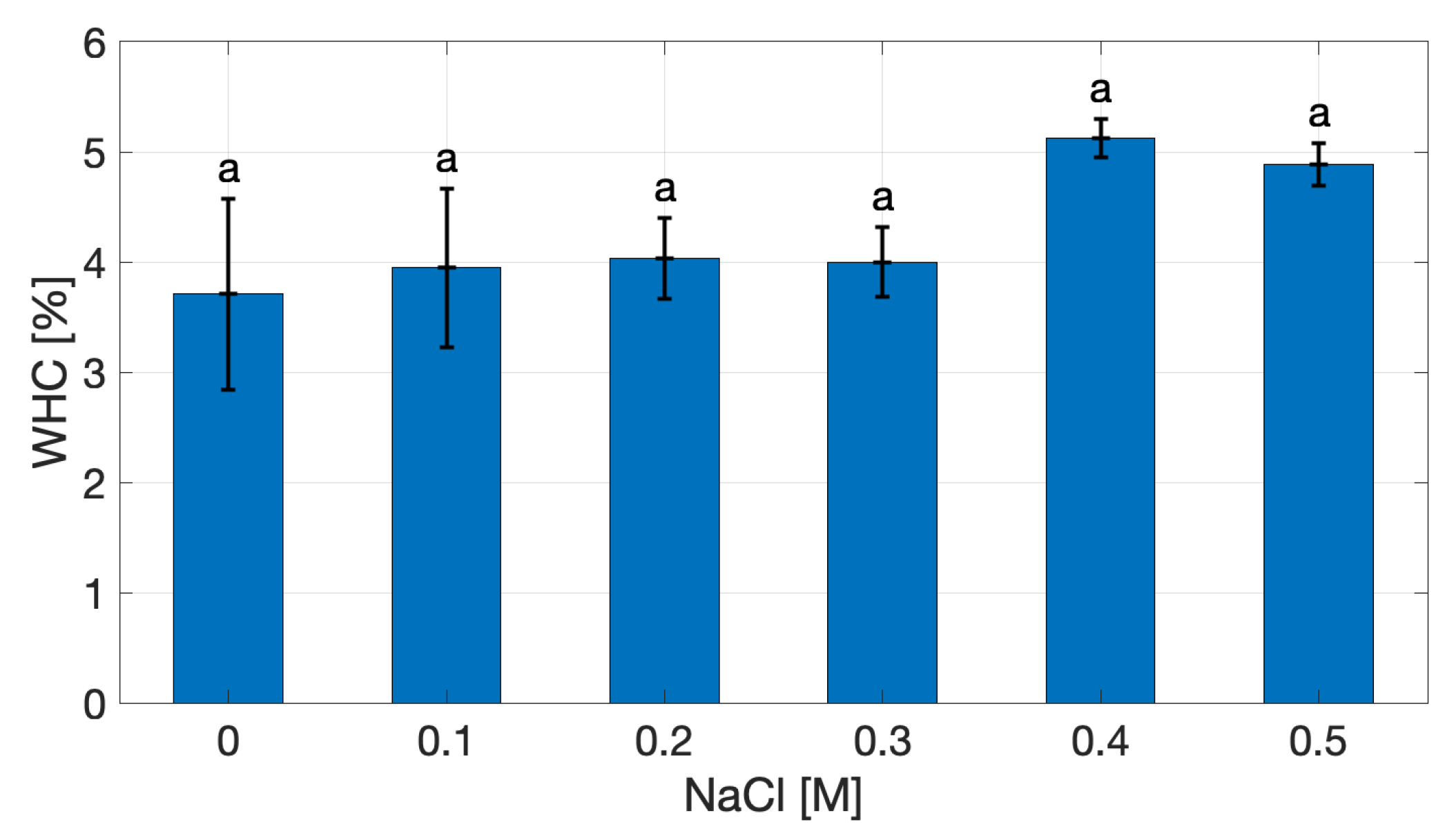

2.1.2. Water-Holding Capacity and Oil-Holding Capacity

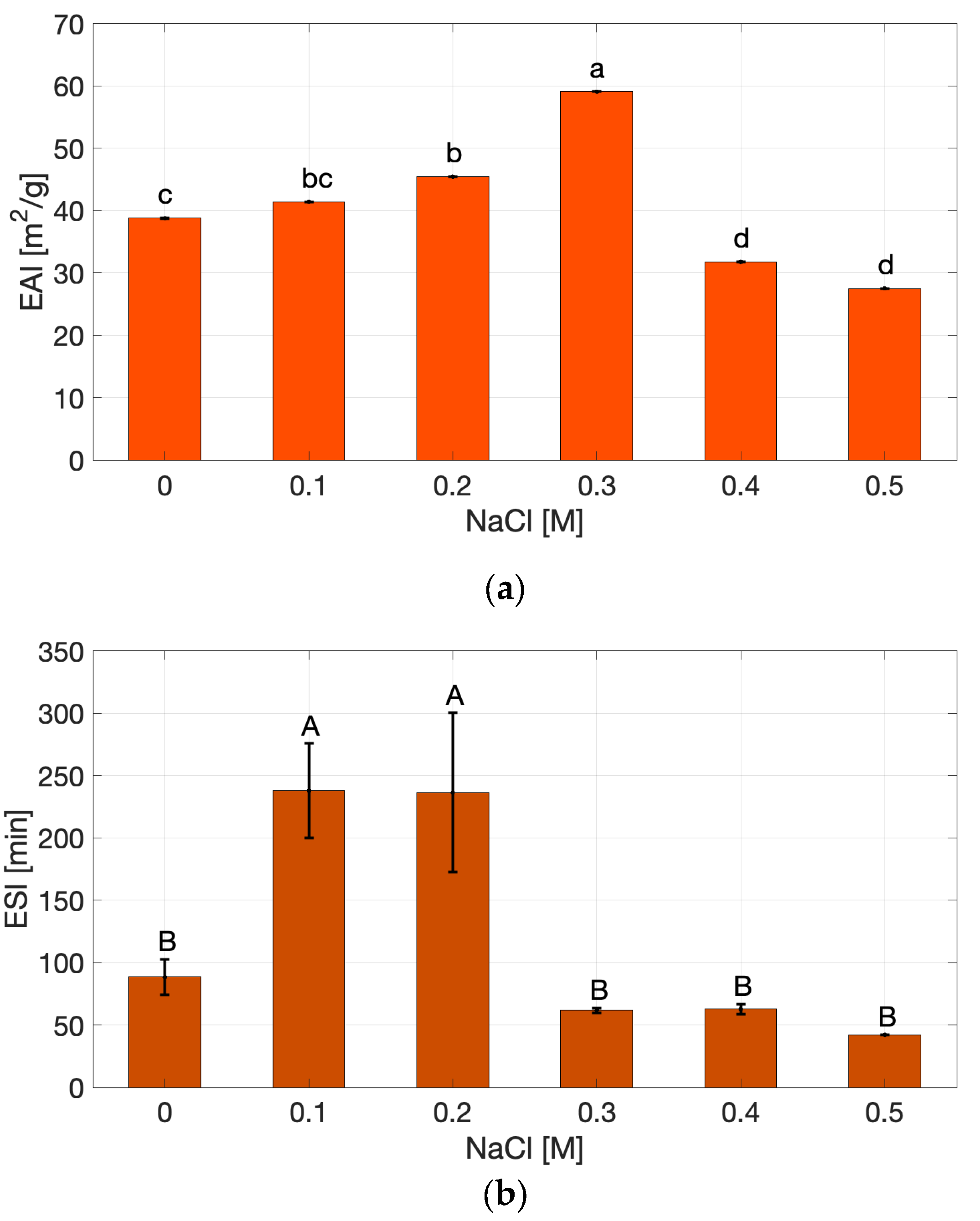

2.1.3. Emulsifying Properties

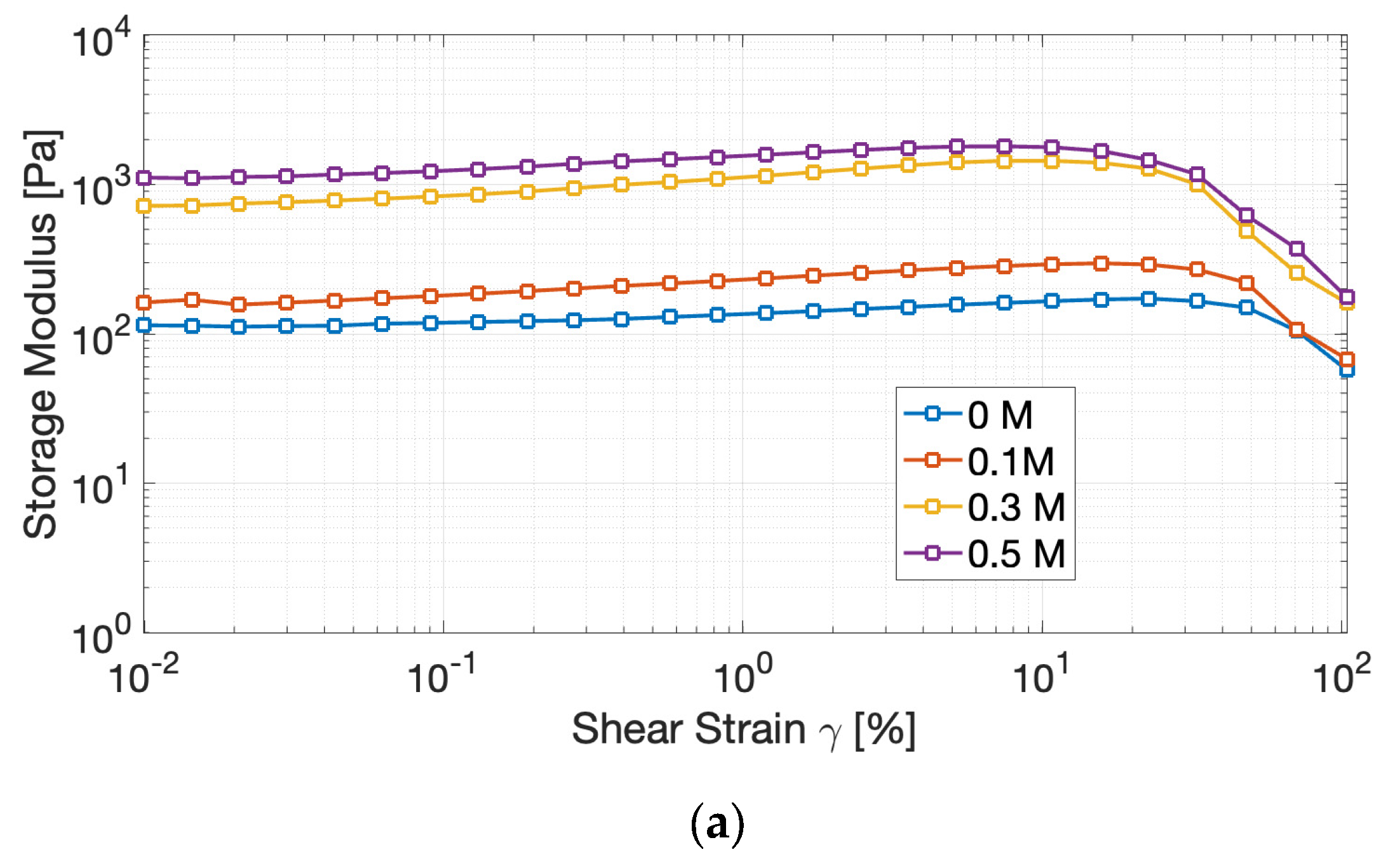

2.2. Rheological Properties of Protein Gels

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Protein Extraction

4.3. Protein Solubility

4.4. Water-Holding Capacity and Oil-Holding Capacity

4.5. Emulsifying Properties

4.6. Gel Preparation

4.7. Rheological Characterization

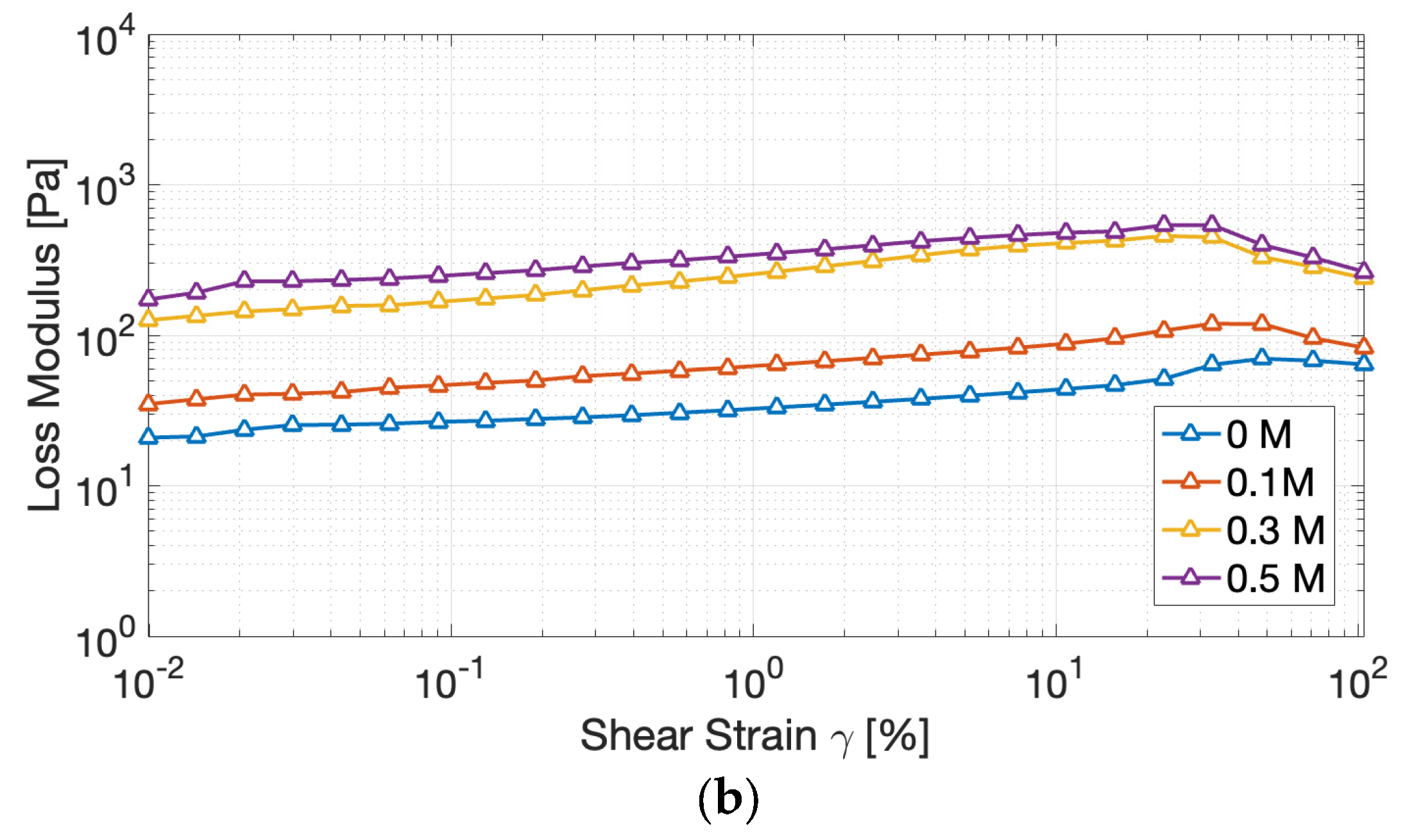

4.7.1. Amplitude Sweep

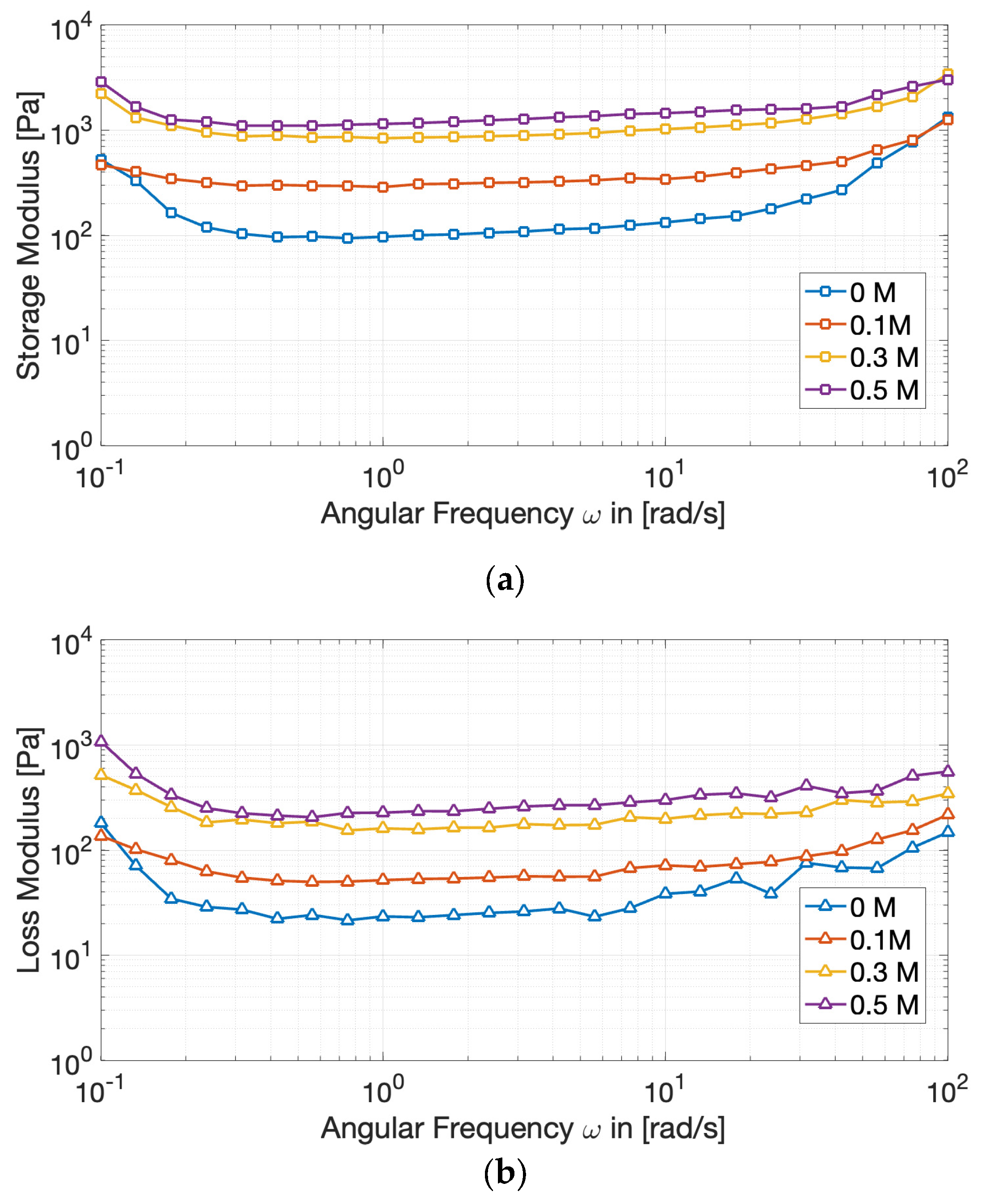

4.7.1. Frequency Sweep

4.8. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- van Huis, A. Potential of insects as food and feed in assuring food security. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2013, 58, 563–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, C.L.R.; Scarborough, P.; Rayner, M.; Nonaka, K. A systematic review of nutrient composition data available for twelve commercially available edible insects, and comparison with reference values. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 47, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumpold, B.A.; Schlüter, O.K. Nutritional composition and safety aspects of edible insects. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2013, 57, 802–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Lakemond, C.M.; Sagis, L.M.; Eisner-Schadler, V.; van Huis, A.; van Boekel, M.A. Extraction and characterisation of protein fractions from five insect species. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 3341–3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishyna, M.; Chen, J.; Benjamin, O. Sensory attributes of edible insects and insect-based foods—Future outlooks for enhancing consumer appeal. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 95, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, E.; Karaś, M.; Jakubczyk, A. Antioxidant activity of predigested protein obtained from a range of farmed edible insects. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 52, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.H.; Ross-Murphy, S.B. Structural and mechanical properties of biopolymer gels. Adv. Polym. Sci. 1983, 83, 57–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekkers, B.L.; Boom, R.M.; van der Goot, A.J. Structuring processes for meat analogues. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 81, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foegeding, E.A.; Davis, J.P. Food protein functionality: A comprehensive approach. Food Hydrocoll. 2011, 25, 1853–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermansson, A.M. Water- and fat-holding. In Functional Properties of Food Macromolecules; 1st ed. Elsevier Applied Science; London, UK, 1986; pp. 273–314.

- Bryant, C.M.; McClements, D.J. Molecular basis of protein functionality with special consideration of cold-set gels derived from heat-denatured whey. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 1998, 9, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renkema, J.M.S.; Gruppen, H.; van Vliet, T. Influence of pH and ionic strength on heat-induced formation and rheological properties of soy protein gels in relation to denaturation and their protein compositions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 6064–6071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanger, C.; Müller, M.; Andlinger, D.; Kulozik, U. Influence of pH and ionic strength on the thermal gelation behaviour of pea protein. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 123, 106903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Z.Y.; Kilara, A. Gelation of pH-aggregated whey protein isolate solution induced by heat, protease, calcium salt, and acidulant. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 1830–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, F.G.; Jones, O.G.; O’Haire, M.E.; Liceaga, A.M. Functional properties of tropical banded cricket (Gryllodes sigillatus) protein hydrolysates. Food Chem. 2017, 224, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishyna, M.; Martinez, J.J.I.; Chen, J.; Benjamin, O. Extraction, characterization and functional properties of soluble proteins from edible grasshopper (Schistocerca gregaria) and honey bee (Apis mellifera). Food Res. Int. 2019, 116, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, R.F.; Muccio, E.; Malvano, F.; Marra, F.; Albanese, D. Exploring the Potential of Acheta domesticus Protein Extracts for the Future of Meat Analogues. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2025, 118, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, A.K.; Karalash, A.; Tyler, R.T.; Warkentin, T.D.; Nickerson, M.T. Functional attributes of pea protein isolates prepared using different extraction methods and cultivars. Food Res. Int. 2015, 76, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Chen, J.; Xiong, Y.L. Structural and emulsifying properties of soy protein isolate subjected to acid and alkaline pH-shifting processes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 7576–7583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sager, V.F.; de la Hera, E.; Gomez, M. Formulation of Heat-Induced Whey Protein Gels for Extrusion-Based 3D Printing. Foods 2021, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, E. Flocculation of protein-stabilized oil-in-water emulsions. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2010, 81, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langton, M.; Hermansson, A.M. Fine-stranded and particulate gels of β-lactoglobulin and whey protein at varying ionic strength. Food Hydrocoll. 1992, 5, 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J. Protein-stabilized emulsions. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2004, 9, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Purohit, P.K. Rheology of fibrous gels under compression. Extreme Mech. Lett. 2022, 54, 101757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klost, M.; Drusch, S. Structure formation and rheological properties of pea protein-based gels. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 94, 622–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaboorani, A.; Blanchet, P. Determining the linear viscoelastic region of sugar maple wood by dynamic mechanical analysis. BioResources 2014, 9, 4392–4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Hernández, L.; Chavarría-Hernández, N.; Tecante, A.; López-Ortega, M.A.; López Cuellar, M.R.; Rodríguez-Hernández, A.I. Mixed gels based on low acyl gellan and citrus pectin: A linear viscoelastic analysis. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 137, 108353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewoldt, R.H.; Hosoi, A.E.; McKinley, G.H. New measures for characterizing nonlinear viscoelasticity in large amplitude oscillatory shear. J. Rheol. 2008, 52, 1427–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, K.; Shu, X.Z.; Mou, R.; Lombardi, J.; Prestwich, G.D.; Rafailovich, M.H.; Clark, R.A.F. Rheological characterization of in situ cross-linkable hyaluronan hydrogels. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6, 2857–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, H.H.; Chambon, F. Analysis of linear viscoelasticity of a crosslinking polymer at the gel point. J. Rheol. 1986, 30, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezger, T.G. The Rheology Handbook, 4th ed.; Vincentz Network: Hannover, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ross-Murphy, S.B. Rheological characterization of gels. J. Texture Stud. 1995, 26, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.D.; Wong, N.A.K.; Auh, J.-H. Defatting and sonication enhances protein extraction from edible insects. Korean J. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2017, 37, 955–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Vázquez-Gutiérrez, J.L.; Johansson, D.P.; Landberg, R.; Langton, M. Yellow mealworm protein for food purposes—Extraction and functional properties. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thermo Fisher Scientific. Slide-A-Lyzer™ Dialysis Cassettes and Flasks. 2019. Available online: https://www.thermofisher.com/it/en/home/life-science/protein-biology/protein-purification-isolation/protein-dialysis-desalting-concentration/dialysis-products/slide-a-lyzer-dialysis-cassettes.html (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Zhang, Z.; Holden, G.; Wang, B.; Adhikari, B. Maillard reaction-based conjugation of Spirulina protein with maltodextrin using wet-heating route and characterisation of conjugates. Food Chem. 2023, 406, 134931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC International. AOAC International. AOAC Official Method 2001.11 Protein (Crude) in Animal Feed, Forage (Plant Tissue), Grain, and Oilseeds. In Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Wang, S. Functional properties and structural characteristics of phosphorylated pea protein isolate. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 2002–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdi, T.S.; Setiowati, A.D.; Ningrum, A. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of Spirulina platensis protein: Physicochemical characteristic and techno-functional properties. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2023, 17, 5474–5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, M.D.; Canet, W. Dynamic Viscoelastic Behavior of Vegetable-Based Infant Purees. J. Texture Stud. 2013, 44, 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NaCl [M] |

tan δ [-] |

| 0 | 0.31 ± 0.14A |

| 0.1 | 0.28 ± 0.06AB |

| 0.3 | 0.19 ± 0.04C |

| 0.5 | 0.24 ± 0.08BC |

| NaCl [M] |

k’ [Pa⋅sn] |

k” [Pa⋅sn] |

n’ [-] |

n” [-] |

| 0 | 145.54 | 35.43 | 0.15 | 0.1 |

| 0.1 | 343.43 | 66.91 | 0.11 | 0.08 |

| 0.3 | 1042.90 | 214.50 | 0.07 | 0.01 |

| 0.5 | 1372.10 | 305.61 | 0.06 | 0.03 |

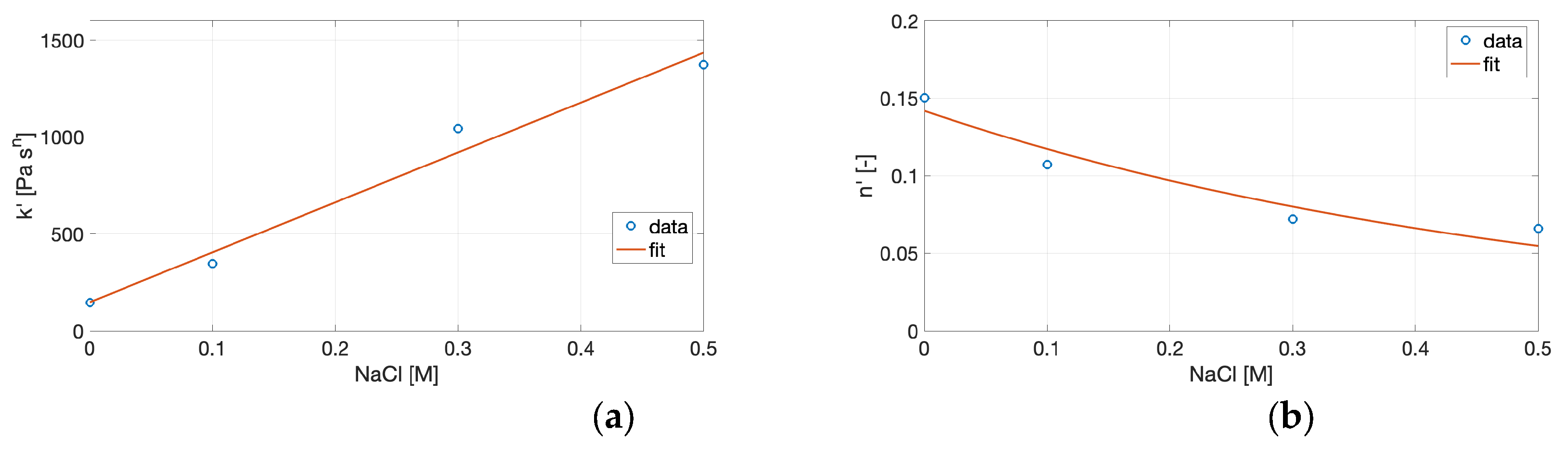

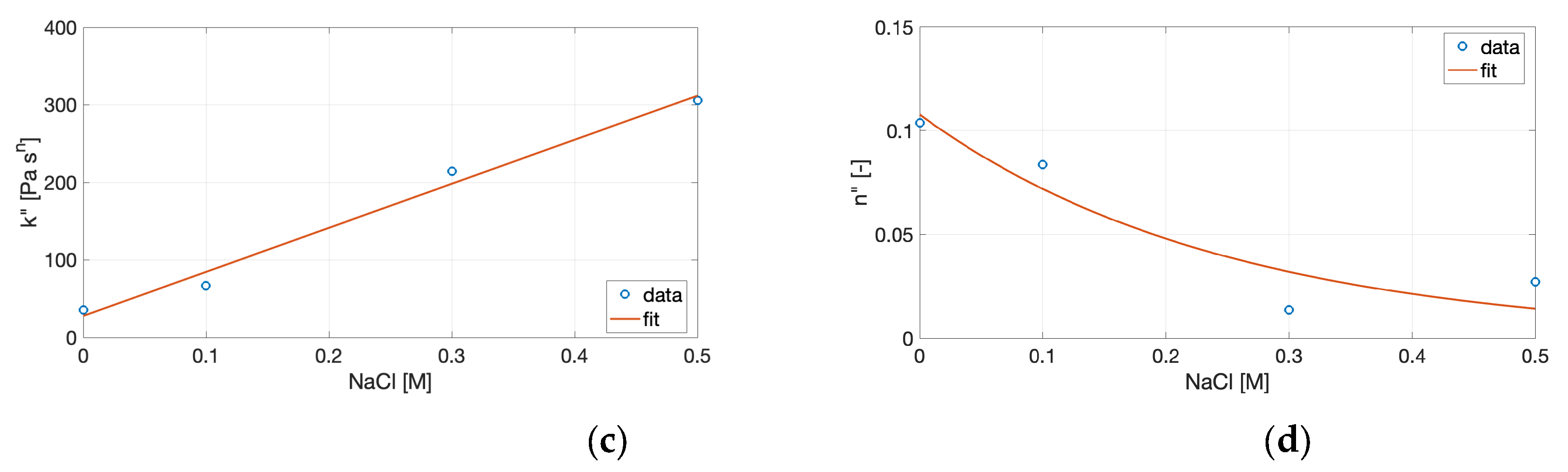

| Parameter | a | b | R2 | c | d | R2 |

| k’ | 2577.60 | 146.64 | 0.977 | - | - | - |

| k” | 568.12 | 27.78 | 0.986 | - | - | - |

| n’ | - | - | - | 0.14 | -1.91 | 0.826 |

| n” | - | - | - | 0.11 | -4.05 | 0.775 |

| Nutrient (per 100 g) |

Value [g] |

| Fat | 11.60 |

| Carbohydrates | 4.60 |

| Fiber | 8.80 |

| Protein | 74.60 |

| Salt | 0.395 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).