Submitted:

24 October 2025

Posted:

27 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

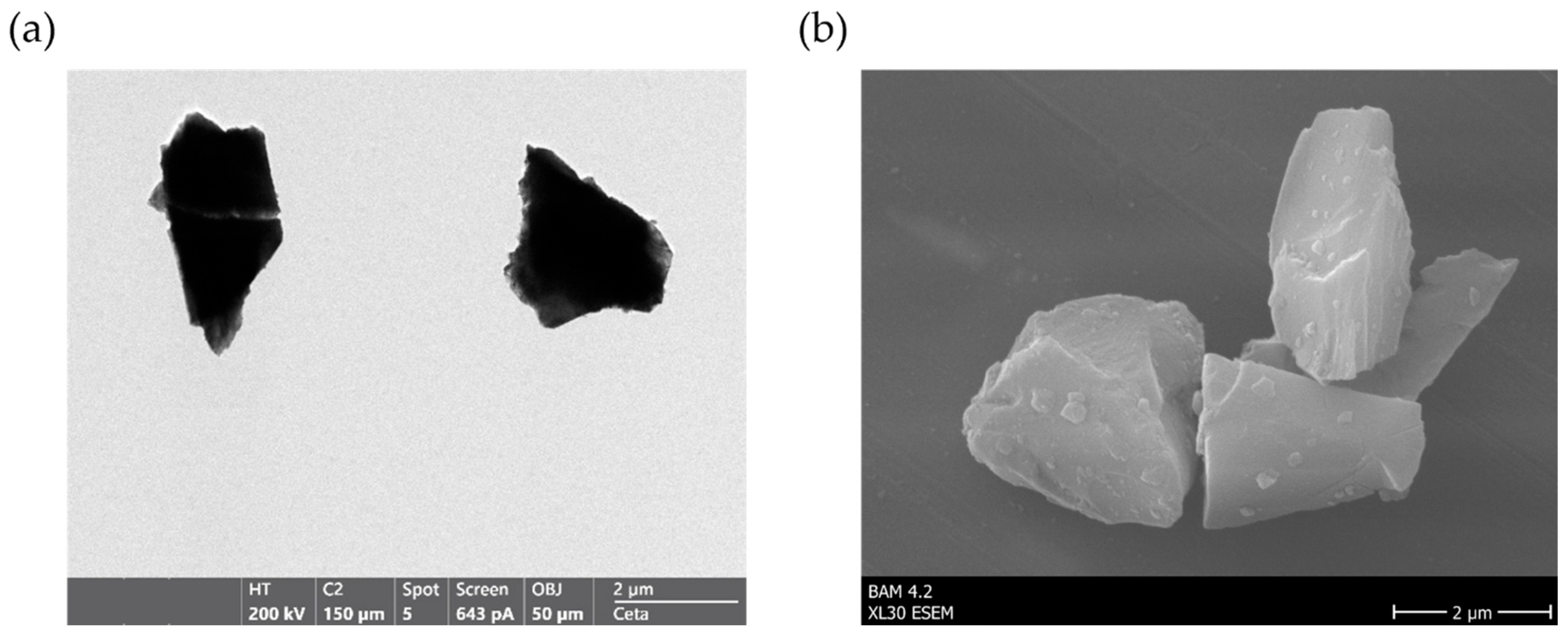

2.2. Particle Characterization via TEM, ESEM and Particle Size Distribution

2.3. Recombinant Production of Porcine Trypsin

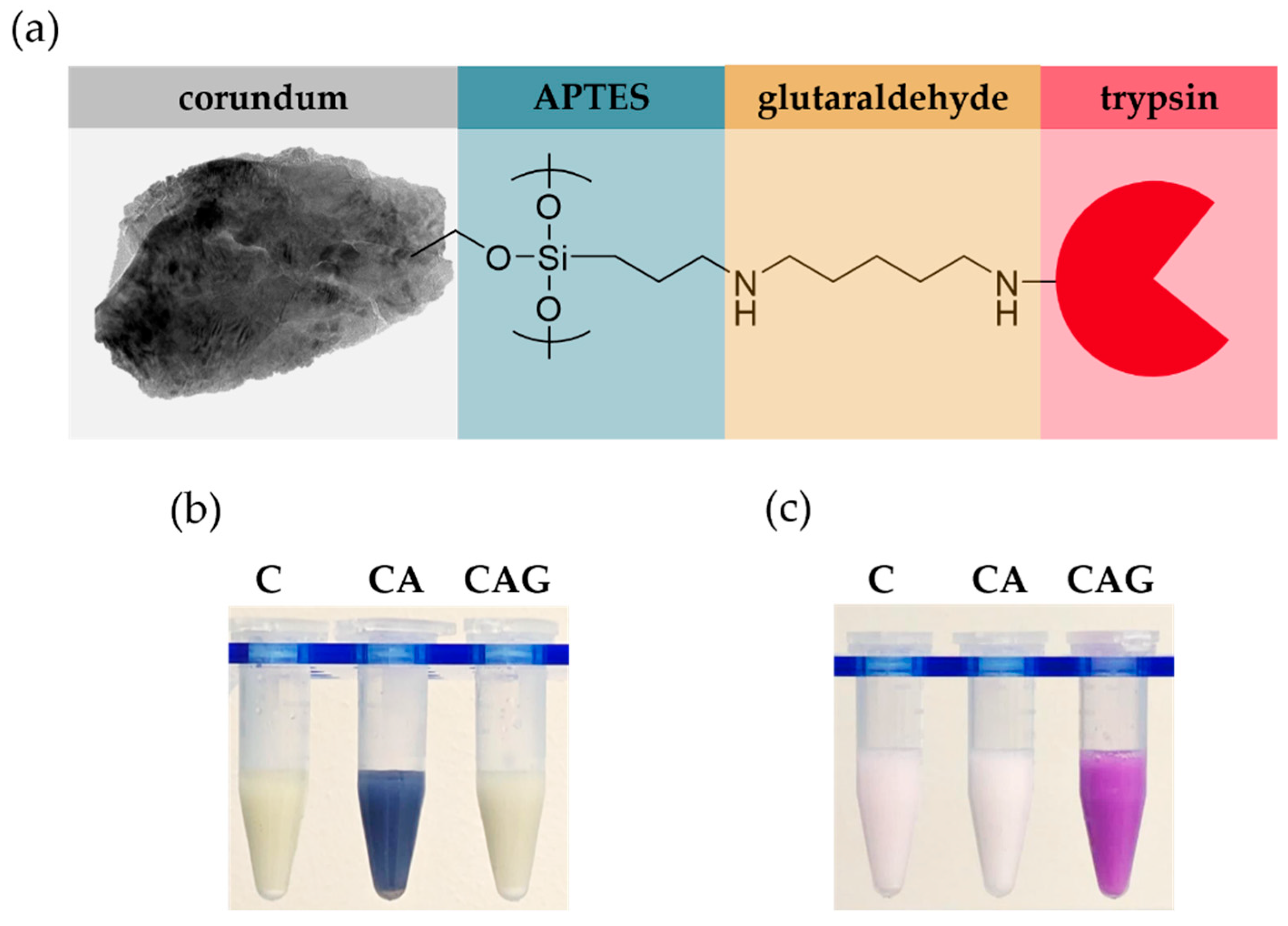

2.4. Surface Modification and Trypsin-Immobilization of Corundum

2.5. Colorimetric Verification of Surface Functionalization

2.5.1. Kaiser Test

2.5.2. Schiff Test

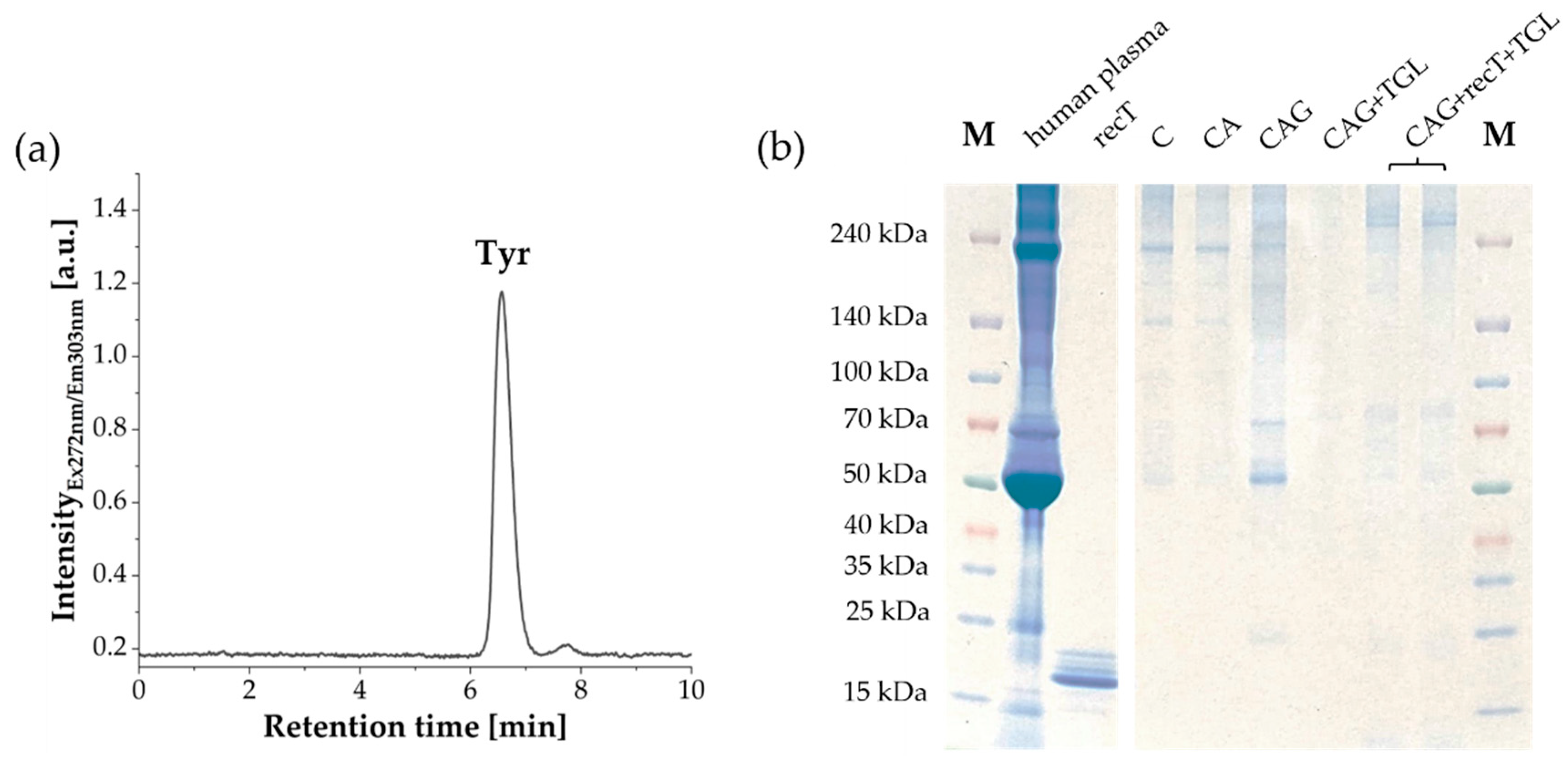

2.6. Aromatic Amino Acid Analysis (AAAA)

2.7. Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

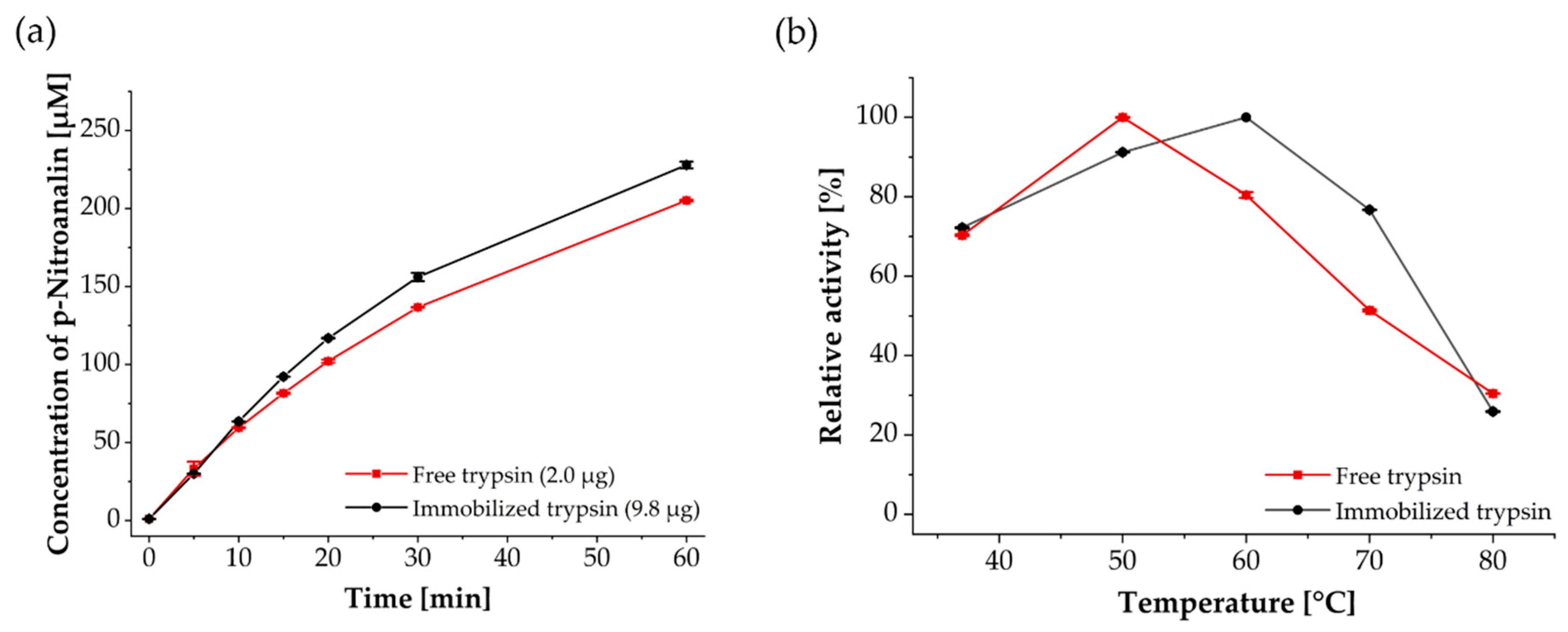

2.8. Trypsin Activity Assay Using Benzoyl-DL-Arginine-p-Nitroanilide (BAPNA)

2.9. Antibody Digestion and LC-MS/MS-Based Quantitative NISTmAb Analysis

2.10. MALDI-TOF MS-Based Antibody Fingerprinting and Identification of Herceptin

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of Raw and Surface-Modified Corundum Particles

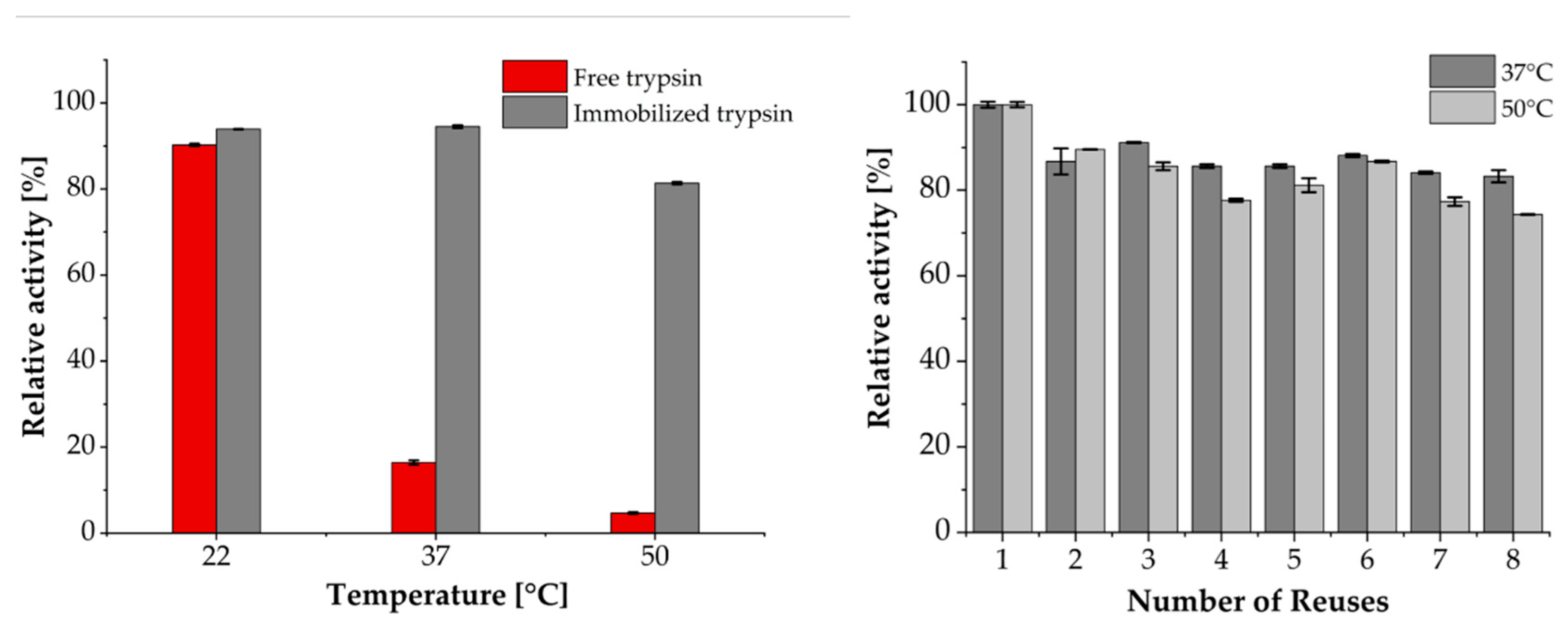

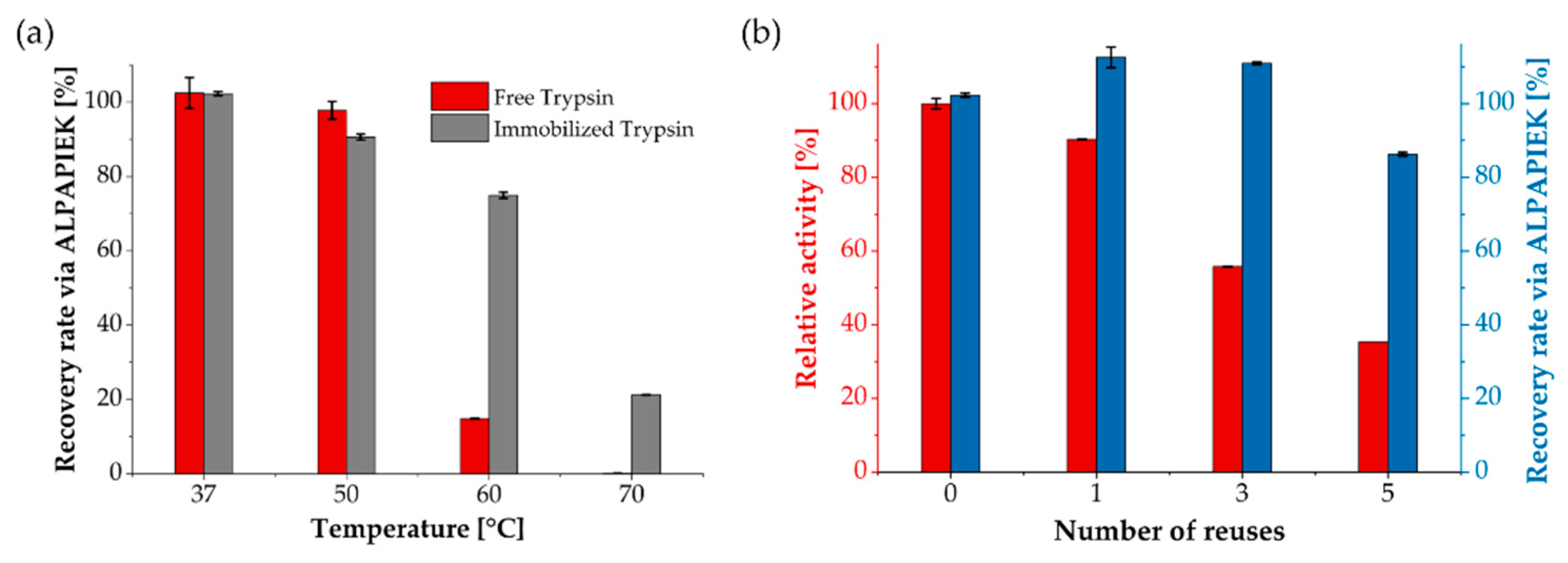

3.2. Enzymatic, Temperature-Dependent Activity and Reusability

3.3. Application for LC-MS/MS-Based Quantification of NISTmAb

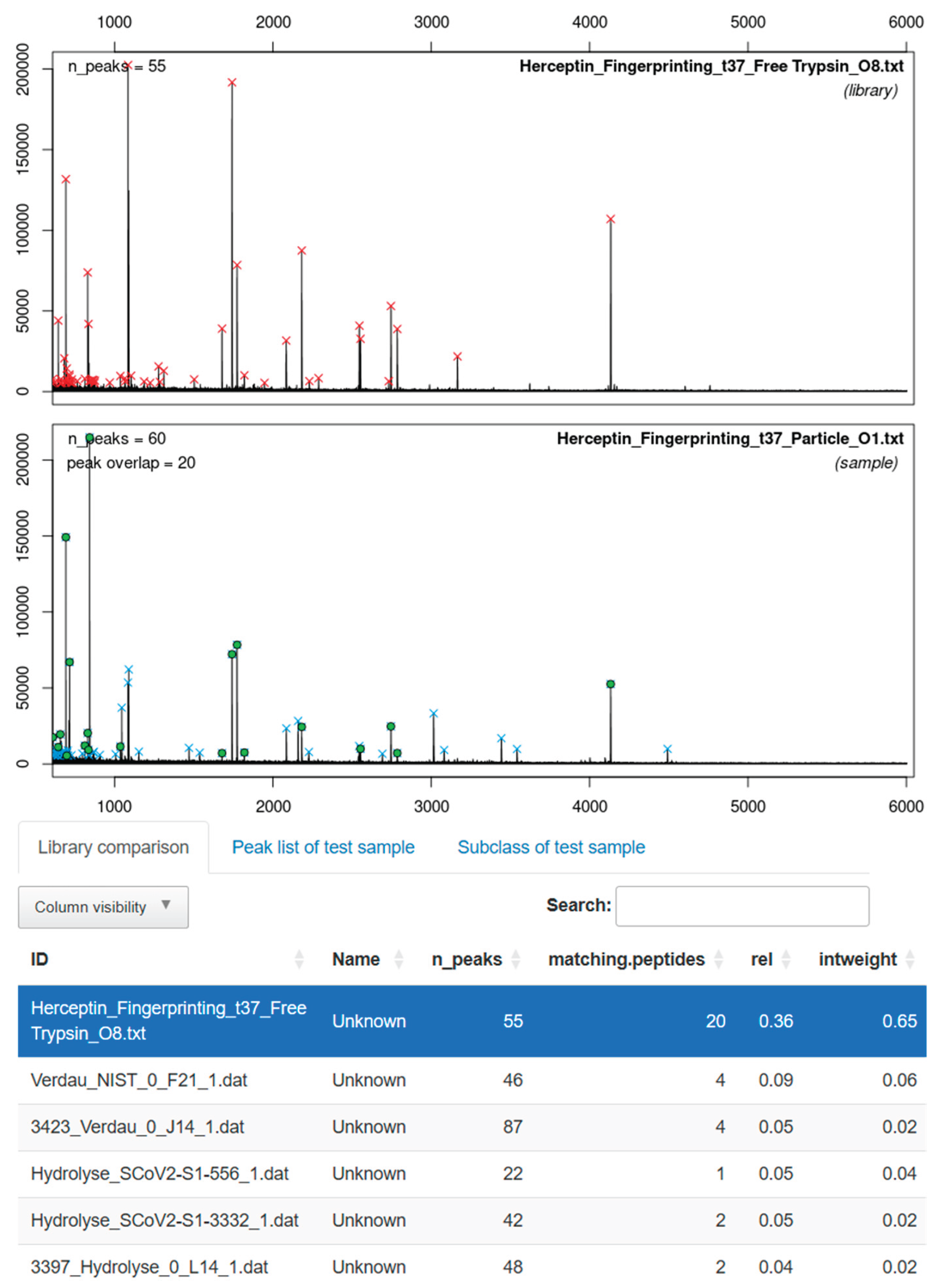

3.4. Application for MALDI-TOF MS-Based Identification of Herceptin

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cavalcante, F.T.; Cavalcante, A.L.; de Sousa, I.G.; Neto, F.S.; dos Santos, J.C. Current status and future perspectives of supports and protocols for enzyme immobilization. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bié, J.; Sepodes, B.; Fernandes, P.C.; Ribeiro, M.H. Enzyme immobilization and co-immobilization: main framework, advances and some applications. Processes 2022, 10, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guisan, J.M.; Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Rocha-Martin, J.; Moreno-Gamero, D. Enzyme immobilization strategies for the design of robust and efficient biocatalysts. Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistry 2022, 35, 100593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghraby, Y.R.; El-Shabasy, R.M.; Ibrahim, A.H.; Azzazy, H.M.E.-S. Enzyme immobilization technologies and industrial applications. ACS omega 2023, 8, 5184–5196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homaei, A.A.; Sariri, R.; Vianello, F.; Stevanato, R. Enzyme immobilization: an update. Journal of chemical biology 2013, 6, 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budžaki, S.; Miljić, G.; Sundaram, S.; Tišma, M.; Hessel, V. Cost analysis of enzymatic biodiesel production in small-scaled packed-bed reactors. Applied energy 2018, 210, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federsel, H.-J.; Moody, T.S.; Taylor, S.J. Recent trends in enzyme immobilization—Concepts for expanding the biocatalysis toolbox. Molecules 2021, 26, 2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asanomi, Y.; Yamaguchi, H.; Miyazaki, M.; Maeda, H. Enzyme-immobilized microfluidic process reactors. Molecules 2011, 16, 6041–6059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiCosimo, R.; McAuliffe, J.; Poulose, A.J.; Bohlmann, G. Industrial use of immobilized enzymes. Chemical Society Reviews 2013, 42, 6437–6474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liese, A.; Hilterhaus, L. Evaluation of immobilized enzymes for industrial applications. Chemical Society Reviews 2013, 42, 6236–6249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Hong, Y.J.; Baik, S.; Hyeon, T.; Kim, D.H. Enzyme-based glucose sensor: from invasive to wearable device. Advanced healthcare materials 2018, 7, 1701150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.H.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, U.J.; Fermin, C.D.; Kim, M. Immobilized enzymes in biosensor applications. Materials 2019, 12, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naldi, M.; Tramarin, A.; Bartolini, M. Immobilized enzyme-based analytical tools in the-omics era: Recent advances. Journal of pharmaceutical and biomedical analysis 2018, 160, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, C.; Szabo, R.; Gaspar, A. Microfluidic immobilized enzymatic reactors for proteomic analyses—Recent developments and trends (2017–2021). Micromachines 2022, 13, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Li, Y.; Xu, W. Micro-immobilized enzyme reactors for mass spectrometry proteomics. Analyst 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basso, A.; Froment, L.; Hesseler, M.; Serban, S. New highly robust divinyl benzene/acrylate polymer for immobilization of lipase CALB. European journal of lipid science and technology 2013, 115, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucca, P.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Sanjust, E. Agarose and its derivatives as supports for enzyme immobilization. Molecules 2016, 21, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavlinskaya, M.S.; Sorokin, A.V.; Holyavka, M.G.; Zuev, Y.F.; Artyukhov, V.G. Cellulose and cellulose-based materials for enzyme immobilization: a review. Biophysical Reviews 2025, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, M.; Kostrov, X. Immobilization of enzymes on porous silicas–benefits and challenges. Chemical Society Reviews 2013, 42, 6277–6289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yu, C. Silica-based nanoparticles for enzyme immobilization and delivery. Chemistry–An Asian Journal 2022, 17, e202200573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ertesvåg, H. Alginate-modifying enzymes: biological roles and biotechnological uses. Frontiers in microbiology 2015, 6, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Völzke, J.L.; Shamami, P.H.; Gawlitza, K.; Feldmann, I.; Zimathies, A.; Meyer, K.; Weller, M.G. High-purity corundum as support for affinity extractions from complex samples. Separations 2022, 9, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Völzke, J.L.; Smatty, S.; Döring, S.; Ewald, S.; Oelze, M.; Fratzke, F.; Flemig, S.; Konthur, Z.; Weller, M.G. Efficient Purification of Polyhistidine-Tagged Recombinant Proteins Using Functionalized Corundum Particles. BioTech 2023, 12, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashist, S.K.; Lam, E.; Hrapovic, S.; Male, K.B.; Luong, J.H. Immobilization of antibodies and enzymes on 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane-functionalized bioanalytical platforms for biosensors and diagnostics. Chemical reviews 2014, 114, 11083–11130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sypabekova, M.; Hagemann, A.; Rho, D.; Kim, S. 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) deposition methods on oxide surfaces in solution and vapor phases for biosensing applications. Biosensors 2022, 13, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migneault, I.; Dartiguenave, C.; Bertrand, M.J.; Waldron, K.C. Glutaraldehyde: behavior in aqueous solution, reaction with proteins, and application to enzyme crosslinking. Biotechniques 2004, 37, 790–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, O.; Ortiz, C.; Berenguer-Murcia, Á.; Torres, R.; Rodrigues, R.C.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Glutaraldehyde in bio-catalysts design: A useful crosslinker and a versatile tool in enzyme immobilization. Rsc Advances 2014, 4, 1583–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinton, F. Sodium cyanoborohydride—a highly selective reducing agent for organic functional groups. Synthesis 1975, 3, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germain, P.; Slagmolen, T.; Crichton, R. Relation between stabilization and rigidification of the three-dimensional structure of an enzyme. Biotechnology and bioengineering 1989, 33, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aebersold, R.; Mann, M. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Nature 2003, 422, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevchenko, A.; Tomas, H.; Havli, J.; Olsen, J.V.; Mann, M. In-gel digestion for mass spectrometric characterization of proteins and proteomes. Nature protocols 2006, 1, 2856–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiatsiani, L.; Heck, A.J. Proteomics beyond trypsin. The FEBS journal 2015, 282, 2612–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.; Mann, M. A beginner’s guide to mass spectrometry–based proteomics. The Biochemist 2020, 42, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, Z.; Ahn, S.B.; Baker, M.S.; Ranganathan, S.; Mohamedali, A. Mass spectrometry–based protein identification in proteomics—a review. Briefings in bioinformatics 2021, 22, 1620–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döring, S.; Weller, M.G.; Reinders, Y.; Konthur, Z.; Jaeger, C. Challenges and insights in absolute quantification of recombinant therapeutic antibodies by mass spectrometry: an introductory review. Antibodies 2025, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlong, M.T.; Ouyang, Z.; Wu, S.; Tamura, J.; Olah, T.; Tymiak, A.; Jemal, M. A universal surrogate peptide to enable LC-MS/MS bioanalysis of a diversity of human monoclonal antibody and human Fc-fusion protein drug candidates in pre-clinical animal studies. Biomedical Chromatography 2012, 26, 1024–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Jian, W. Recent advances in absolute quantification of peptides and proteins using LC-MS. Reviews in Analytical Chemistry 2014, 33, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappin, D.J.; Hojrup, P.; Bleasby, A.J. Rapid identification of proteins by peptide-mass fingerprinting. Current biology 1993, 3, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappin, D.J. Peptide mass fingerprinting using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. In Protein Sequencing Protocols; Springer: 2003; pp. 211–219.

- Wu, F.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, Y.; Su, N.; Xiong, Z.; Xu, P. Recombinant acetylated trypsin demonstrates superior stability and higher activity than commercial products in quantitative proteomics studies. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 2016, 30, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muriithi, B.; Ippoliti, S.; Finny, A.; Addepalli, B.; Lauber, M. Clean and complete protein digestion with an autolysis resistant trypsin for peptide mapping. Journal of Proteome Research 2024, 23, 5221–5228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menneteau, T.; Saveliev, S.; Butré, C.I.; Rivera, A.K.G.; Urh, M.; Delobel, A. Addressing common challenges of biotherapeutic protein peptide mapping using recombinant trypsin. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 2024, 243, 116124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, N.; Light, A. Refolding of reduced, denatured trypsinogen and trypsin immobilized on Agarose beads. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1975, 250, 8624–8629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Cai, X.; Wang, R.-Q.; Xiao, J. Immobilized trypsin on hydrophobic cellulose decorated nanoparticles shows good stability and reusability for protein digestion. Analytical biochemistry 2015, 477, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahin, S.; Ozmen, I. Covalent immobilization of trypsin on polyvinyl alcohol-coated magnetic nanoparticles activated with glutaraldehyde. Journal of pharmaceutical and biomedical analysis 2020, 184, 113195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aversa, I.F.; Cavalcanti, M.H.; Pereira, T.M. ; A. de Castro, A.; Tavano, O.L.; Coelho, Y.L.; da Silva, L.H.; Gorup, L.F.; Ramalho, T.C.; Virtuoso, L.S. Immobilization of Porcine Trypsin in Superparamagnetic Nanoparticles: Enzyme Activity and Stability. ACS omega. [CrossRef]

- Aslani, E.; Abri, A.; Pazhang, M. Immobilization of trypsin onto Fe3O4@ SiO2–NH2 and study of its activity and stability. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2018, 170, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Lee, S. Immobilization of trypsin from porcine pancreas onto chitosan nonwoven by covalent bonding. Polymers 2019, 11, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguez, J.P.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Tavano, O.L.; Mendes, A.A. The immobilization and stabilization of trypsin from the porcine pancreas on chitosan and its catalytic performance in protein hydrolysis. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massolini, G.; Calleri, E. Immobilized trypsin systems coupled on-line to separation methods: Recent developments and analytical applications. Journal of separation science 2005, 28, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnier, F.E.; Kim, J. Accelerating trypsin digestion: the immobilized enzyme reactor. Bioanalysis 2014, 6, 2685–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naldi, M.; Černigoj, U.; Štrancar, A.; Bartolini, M. Towards automation in protein digestion: Development of a monolithic trypsin immobilized reactor for highly efficient on-line digestion and analysis. Talanta 2017, 167, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinders, L.M.; Klassen, M.D.; Teutenberg, T.; Jaeger, M.; Schmidt, T.C. Development of a multidimensional online method for the characterization and quantification of monoclonal antibodies using immobilized flow-through enzyme reactors. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2021, 413, 7119–7128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Chu, Z.; Zhu, M.; Song, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Meng, B.; Gong, X.; Zhang, D.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, L. Precise control of trypsin immobilization by a programmable DNA tetrahedron designed for ultrafast proteome digestion and accurate protein quantification. Analytical Chemistry 2023, 95, 15875–15883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tscheuschner, G.; Schwaar, T.; Weller, M.G. Fast confirmation of antibody identity by MALDI-TOF MS fingerprints. Antibodies 2020, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tscheuschner, G.; Kaiser, M.N.; Lisec, J.; Beslic, D.; Muth, T.; Krüger, M.; Mages, H.W.; Dorner, B.G.; Knospe, J.; Schenk, J.A. MALDI-TOF-MS-based identification of monoclonal murine anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies within one hour. Antibodies 2022, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiel, J.E.; Turner, A. The NISTmAb Reference Material 8671 lifecycle management and quality plan. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry 2018, 410, 2067–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, E.; Colescott, R.L.; Bossinger, C.D.; Cook, P. Color test for detection of free terminal amino groups in the solid-phase synthesis of peptides. Analytical biochemistry 1970, 34, 595–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarin, V.K.; Kent, S.B.; Tam, J.P.; Merrifield, R.B. Quantitative monitoring of solid-phase peptide synthesis by the ninhydrin reaction. Analytical biochemistry 1981, 117, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stauß, A.C.; Fuchs, C.; Jansen, P.; Repert, S.; Alcock, K.; Ludewig, S.; Rozhon, W. The ninhydrin reaction revisited: optimisation and application for quantification of free amino acids. Molecules 2024, 29, 3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinmuth-Selzle, K.; Tchipilov, T.; Backes, A.T.; Tscheuschner, G.; Tang, K.; Ziegler, K.; Lucas, K.; Pöschl, U.; Fröhlich-Nowoisky, J.; Weller, M.G. Determination of the protein content of complex samples by aromatic amino acid analysis, liquid chromatography-UV absorbance, and colorimetry. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2022, 414, 4457–4470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlanger, B.F.; Kokowsky, N.; Cohen, W. The preparation and properties of two new chromogenic substrates of trypsin. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics 1961, 95, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsugawa, H.; Cajka, T.; Kind, T.; Ma, Y.; Higgins, B.; Ikeda, K.; Kanazawa, M.; VanderGheynst, J.; Fiehn, O.; Arita, M. MS-DIAL: data-independent MS/MS deconvolution for comprehensive metabolome analysis. Nature methods 2015, 12, 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Q.; Liang, Y.; Yan, X.; Markey, S.P.; Mirokhin, Y.A.; Tchekhovskoi, D.V.; Bukhari, T.H.; Stein, S.E. The NISTmAb tryptic peptide spectral library for monoclonal antibody characterization. MAbs 2018, 10, 354–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisec, J. ABID. Available online: https://github.com/BAMresearch/ABID. (accessed on 06.10.2025).

- Schiff, H. Eine neue reihe organischer diamine. Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie 1866, 140, 92–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieland, H.; Scheuing, G. Die Fuchsin-schweflige Säure und ihre Farbreaktion mit Aldehyden. Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft (A and B Series) 1921, 54, 2527–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesse, A.; Weller, M.G. Protein quantification by derivatization-free high-performance liquid chromatography of aromatic amino acids. Journal of amino acids 2016, 2016, 7374316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronsema, K.J.; Bischoff, R.; Pijnappel, W.P.; van der Ploeg, A.T.; Van De Merbel, N.C. Absolute quantification of the total and antidrug antibody-bound concentrations of recombinant human α-glucosidase in human plasma using protein G extraction and LC-MS/MS. Analytical Chemistry 2015, 87, 4394–4401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mi, W.; Josephs, R.; Melanson, J.; Dai, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhai, R.; Chu, Z.; Fang, X.; Thibeault, M.; Stocks, B. PAWG pilot study on quantification of SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibody-part 1. Metrologia 2022, 59, 08001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martos, G.; Bedu, M.; Josephs, R.; Westwood, S.; Wielgosz, R. Quantification of SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal IgG mass fraction by isotope dilution mass spectrometry. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2024, 416, 2423–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harries, M.; Smith, I. The development and clinical use of trastuzumab (Herceptin). Endocrine-related cancer 2002, 9, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubb, W.A.; Berthon, H.A.; Kuchel, P.W. Tris buffer reactivity with low-molecular-weight aldehydes: NMR characterization of the reactions of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate. Bioorganic Chemistry 1995, 23, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.S.; Lee, Y.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, S.S.; Chung, J.M.; Jung, H.S. Optimizing protein crosslinking control: Synergistic quenching effects of glycine, histidine, and lysine on glutaraldehyde reactions. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2024, 702, 149567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, D.; Sezer, S.; Ulu, A.; Köytepe, S.; Ateş, B. Preparation and characterization of amino-functionalized zeolite/SiO2 materials for trypsin–chymotrypsin co-immobilization. Catalysis Letters 2021, 151, 2463–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, A.; Cruz, J.; Rueda, N.; dos Santos, J.C.; Torres, R.; Ortiz, C.; Villalonga, R.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Inactivation of immobilized trypsin under dissimilar conditions produces trypsin molecules with different structures. RSC advances 2016, 6, 27329–27334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zhu, G.; Yan, X.; Mou, S.; Dovichi, N.J. Uncovering immobilized trypsin digestion features from large-scale proteome data generated by high-resolution mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography A 2014, 1337, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y. Preparation of high efficiency and low carry-over immobilized enzymatic reactor with methacrylic acid–silica hybrid monolith as matrix for on-line protein digestion. Journal of Chromatography A 2014, 1371, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Anderson, K.W. Rapid removal of IgG1 carryover on protease column using protease-safe wash solutions delivered with LC pump for HDX-MS systems. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry 2024, 36, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Tao, D.; Ma, J.; Sun, L.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y. Hydrophilic monolith based immobilized enzyme reactors in capillary and on microchip for high-throughput proteomic analysis. Journal of Chromatography A 2011, 1218, 2898–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.C.; Lopez-Ferrer, D.; Lee, S.M.; Ahn, H.K.; Nair, S.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, B.S.; Petritis, K.; Camp, D.G.; Grate, J.W. Highly stable trypsin-aggregate coatings on polymer nanofibers for repeated protein digestion. Proteomics 2009, 9, 1893–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camperi, J.; Grunert, I.; Heinrich, K.; Winter, M.; Özipek, S.; Hoelterhoff, S.; Weindl, T.; Mayr, K.; Bulau, P.; Meier, M. Inter-laboratory study to evaluate the performance of automated online characterization of antibody charge variants by multi-dimensional LC-MS/MS. Talanta 2021, 234, 122628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaeek, M.; Khoury, L.R. Bovine Serum Albumin–Trypsin Sponges for Enhanced Enzymatic Stability and Protein Digestion Efficiency. ACS Applied Bio Materials 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oezipek, S.; Hoelterhoff, S.; Breuer, S.; Bell, C.; Bathke, A. mD-UPLC-MS/MS: Next generation of mAb characterization by multidimensional ultraperformance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry and parallel on-column lysC and trypsin digestion. Analytical Chemistry 2022, 94, 8136–8145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, F.-F.; Wang, P.; Han, X.-J.; Qin, T.-T.; Lu, X.; Bai, H.-J. Efficient and rapid digestion of proteins with a dual-enzyme microreactor featuring 3-D pores formed by dopamine/polyethyleneimine/acrylamide-coated KIT-6 molecular sieve. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 15667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilke, M.; Röder, B.; Paul, M.; Weller, M.G. Sintered glass monoliths as supports for affinity columns. Separations 2021, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainer, T.; Egger, A.-S.; Zeindl, R.; Tollinger, M.; Kwiatkowski, M.; Müller, T. 3D-printed high-pressure-resistant immobilized enzyme microreactor (ΜIMER) for protein analysis. Analytical Chemistry 2022, 94, 8580–8587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).