Submitted:

24 October 2025

Posted:

27 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results and Discussion

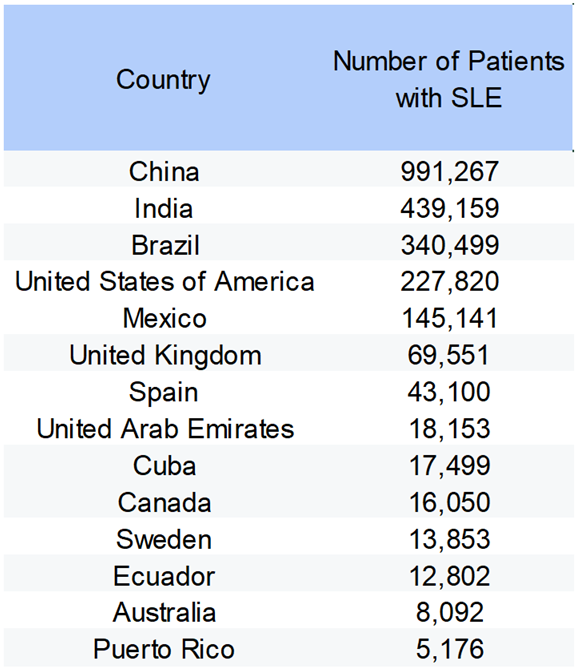

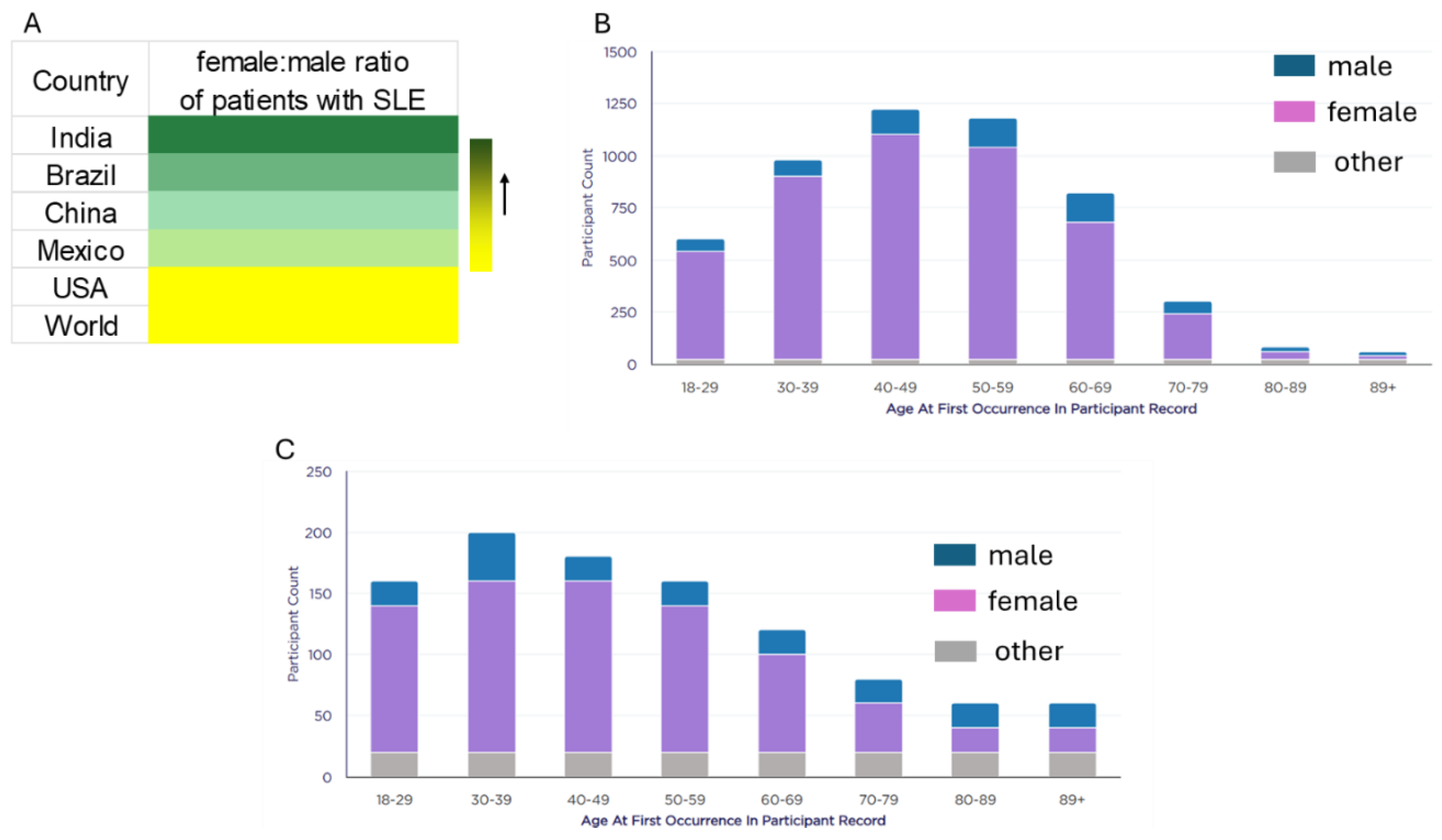

3.1. Demographics and SLE

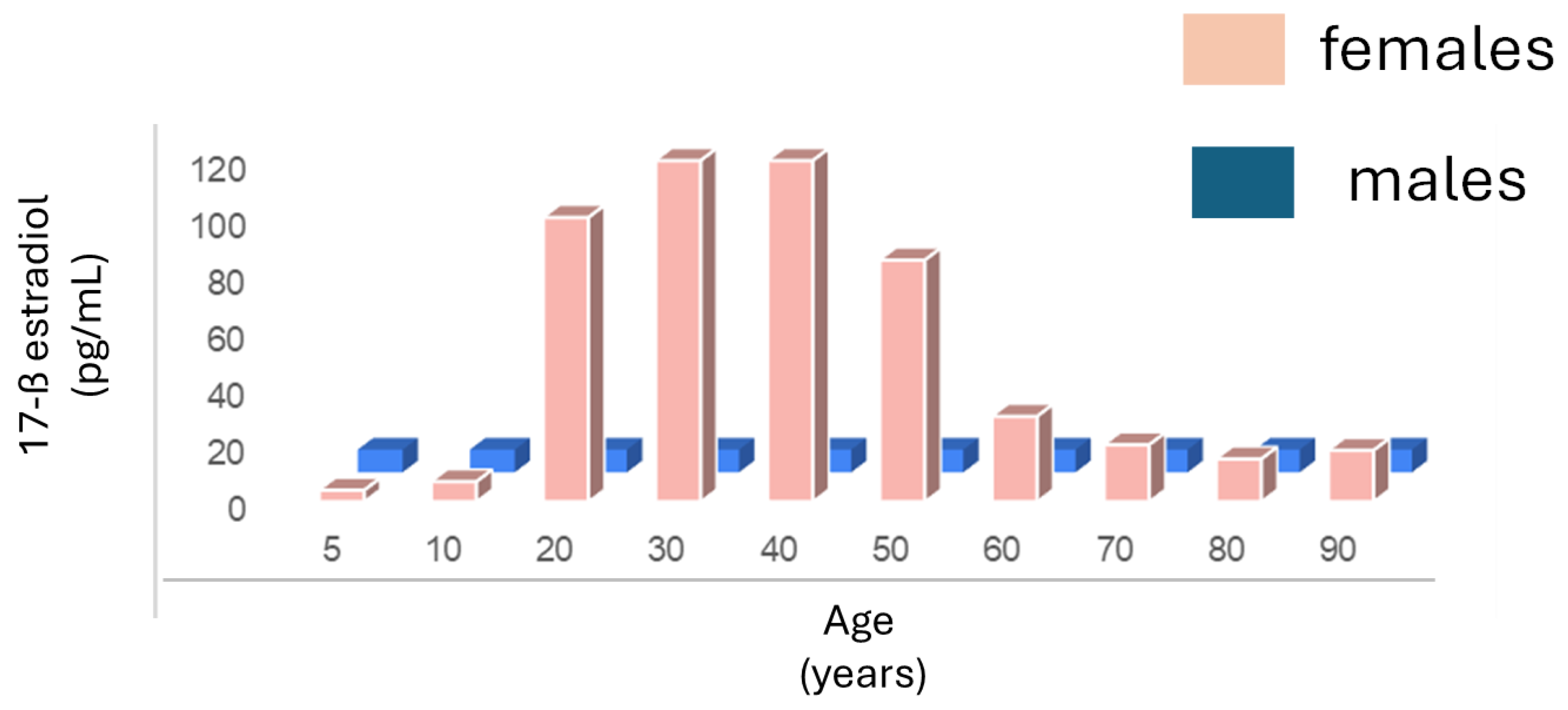

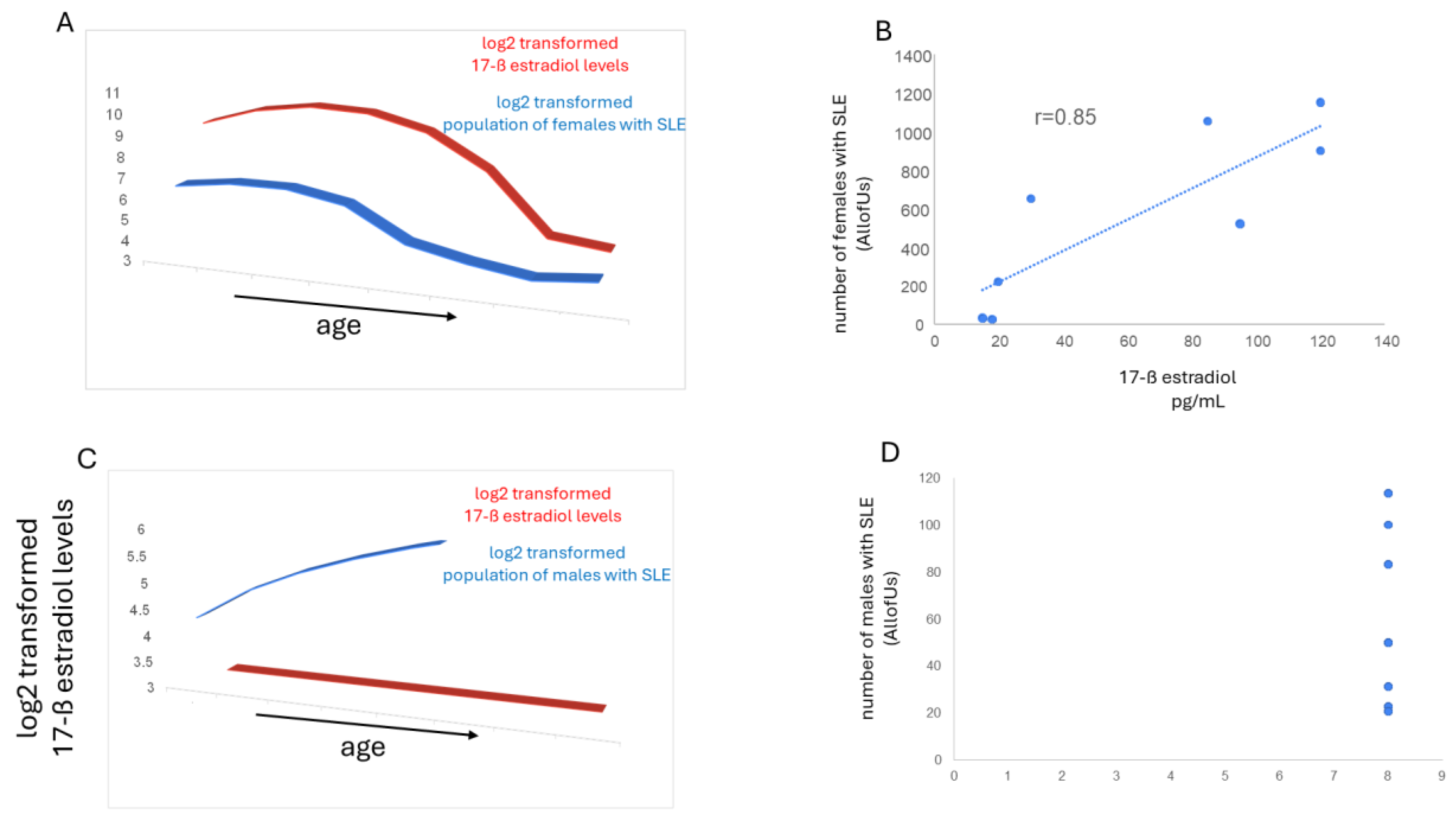

3.2. Estrogen and SLE

3.3. Diagnosis Delays and Demographics

3.4. Diagnosis Delays and Outcomes in SLE

4. Conclusion

References

- European Lupus Society. Global epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus: a comprehensive systematic analysis and modelling study. SLEuro. Last accessed April 4, 2025.

- The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. People with Lupus. May 15, 2024. Last accessed April 4, 2025.

- Lupus Foundation of America; last accessed April 4, 2025.

- Lao C, et al. Mortality and causes of death in systemic lupus erythematosus in New Zealand: a population-based study. Rheumatology 63:1560-1567, 2024.

- Zen M, et al. Mortality and causes of death in systemic lupus erythematosus over the last decade: Data from a large population-based study. Eur J Intern Med 112:45-5, 2023.

- Buie J, et al. Disparities in Lupus and the Role of Social Determinants of Health: Current State of Knowledge and Directions for Future Research. ACR Open Rheumatol 5:454–464, 2023.

- Nikolopoulos D, et al. Evolving phenotype of systemic lupus erythematosus in Caucasians: low incidence of lupus nephritis, high burden of neuropsychiatric disease and increased rates of late-onset lupus in the ‘Attikon’ cohort. Lupus 29:514–52, 2020.

- Sun TY, et al. Large-scale characterization of gender differences in diagnosis prevalence and time to diagnosis. MedRxiv [Preprint]. 2023.10.12.23296976, 2023.

- Westergaard D, et al. Population-wide analysis of differences in disease progression patterns in men and women. Nat Commun 10, 666, 2019.

- AllofUs; last accessed October 23, 2025.

- Population by Country (2025) - Worldometer; last accessed, October 23, 2025.

- Tian J, et al. Global epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus: a comprehensive systematic analysis and modelling study. Ann Rheum Dis 82:351–356, 2023.

- Mok CC, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcome of southern Chinese males with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 8:188-96, 1999.

- Mathur R, et al. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in India: A Clinico-Serological Correlation. Cureus 14:e25763, 2022.

- Martyres A, et al. Mapping the spatial and temporal frequency of systemic lupus erythematosus in Brazil Rev Bras Epidemiol 28:e250030, 2025.

- Fajardo Hermosillo LD. AB0588 Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in Men from a Mexican Cohort. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 74, Supplement 2, 1096-1097, 2015.

- Veser CA, et al. Embracing Sex-specific Differences in Engineered Kidney Models for Enhanced Biological Understanding. 10.48550/arXiv.2308.15264; 2023.

- Abdolahpur S, et al. The Effect of Estradiol and Testosterone Levels Alone or in Combination with Their Receptors in Predicting the Severity of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Cohort Study. Iran J Med Sci 50:69-76, 2025.

- Constatin AM, Bicus C. Estradiol in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Acta Endocrinol (Buchar) 19:274–276, 2023.

- Marsh EE, et al. Estrogen Levels Are Higher across the Menstrual Cycle in African-American Women Compared with Caucasian Women. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 96:1, 2011.

- Ramirez-Flores MF, et al. Factors associated with delay in the diagnosis and treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus in adult patients: a systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford), keaf384, 2025.

- Morgan C, et al. Individuals living with lupus: findings from the LUPUS UK Members Survey 2014. Lupus 27:681–687, 2018.

- Jeleniewicz R, et al. Clinical picture of late-onset systemic lupus erythematosus in a group of Polish patients. POLSKIE ARCHIWUM MEDYCYNY WEWNĘTRZNEJ 125 (7-8), 2015.

- Not so inactive X chromosome | Whitehead Institute; last accessed, October 23, 2025.

- Manik R, et al. Racial Disparities and Strategies for Improving Equity in Diagnostic Follow-Up for Abnormal Screening Mammograms. JCO Oncol Pract 20:1367-1375, 2024.

- George P, et al. Diagnosis and Surgical Delays in African American and White Women with Early-Stage Breast Cancer. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 68:419–422, 2019.

- Zhang, W.; et al. Time to Diagnosis for Endometriosis by Race. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology 28, Supplement, Page S150, 2021.

- Akinsanya J, et al. The Impact of Race and Ethnicity on Time to Diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis: Preliminary Results Neurology 98:756, 2022.

- Buie, J. Factors Influencing Time to Diagnosis in U.S. Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 75 (suppl 9), 2023.

- African-American Ethnicity Associated with Longer Time to Lupus Low Disease Activity State • Johns Hopkins Rheumatology; last accessed, 10/24/2025.

- Maningding E, et al. Racial and Ethnic Differences in the Prevalence and Time to Onset of Manifestations of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: The California Lupus Surveillance Project. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 72:622-629, 2020.

- Kernder A, et al. Delayed diagnosis adversely affects outcome in systemic lupus erythematosus: Cross sectional analysis of the LuLa cohort. Lupus 30:431–438, 2021.

- Nieto, R; et al. DELAYED DIAGNOSIS IN SYSTEMIC LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS. The Journal of Rheumatology 52 (Suppl 1) 14-15, 2025.

- Mitchell, JL. Understanding the impact of delayed diagnosis and misdiagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). J Family Med Prim Care 13:4819–4823, 2024.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).