1. Introduction

1.1. The Metaverse Paradigm: Conceptual Foundations

The Metaverse represents an evolutionary leap in digital ecosystems, integrating virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and mixed reality (MR) technologies to create persistent, shared environments where physical and digital realities converge [

1,

2]. Originally conceptualized in speculative fiction, this technological paradigm has rapidly matured into a multidisciplinary research domain with profound implications for human-computer interaction, digital economies, and social structures [

20,

25].

The fundamental innovation of the Metaverse lies in its capacity to facilitate immersive, embodied experiences through avatars and digital representations, enabling unprecedented forms of social interaction, economic activity, and creative expression [

24,

28]. Unlike conventional digital platforms, the Metaverse offers persistent virtual worlds that evolve autonomously of individual user participation, creating complex ecosystems of user-generated content and decentralized governance [

4,

5].

1.2. Societal Transformation and Economic Implications

The accelerating adoption of Metaverse technologies raises critical sociological questions concerning digital identity formation, community dynamics, and cultural transformation [

3,

32]. As corporate and governmental investments in Metaverse infrastructure intensify, concerns regarding platform monopolization, digital divides, and algorithmic governance demand urgent scholarly attention [

19,

27].

Current research predominantly focuses on technical implementation challenges, including real-time rendering, network latency, and scalable architecture [

22,

23]. However, comprehensive frameworks addressing socio-technical dimensions—privacy, ethics, accessibility, and long-term psychological impacts—remain underdeveloped [

17,

36]. This survey bridges this critical gap by providing a holistic analysis that integrates technical capabilities with societal considerations.

1.3. Research Contributions and Organizational Framework

Our contributions are fivefold: (1) We introduce a comprehensive taxonomy for categorizing Metaverse technologies and their societal implications; (2) We conduct a systematic analysis of current applications, challenges, and research gaps across multiple domains; (3) We provide an in-depth examination of the historical evolution and development trajectory; (4) We analyze emerging economic models and their societal implications; (5) We propose a comprehensive research agenda addressing critical issues in interoperability, ethics, and sustainable development.

Section 2 presents our conceptual framework, which structures the comparative analysis and research synthesis throughout this paper.

2. Taxonomy and Conceptual Framework

2.1. Multi-Dimensional Organizational Structure

We propose a novel multi-dimensional taxonomy that organizes the Metaverse ecosystem along orthogonal axes: the

technical stack and

socio-technical layers. The technical dimension comprises four foundational pillars: Interfaces (XR technologies), Intelligence (AI/ML systems), Trust & Identity (blockchain/DID frameworks), and Infrastructure (cloud/edge/5G networks). The socio-technical dimension encompasses Governance & Standards, Safety & Ethics, and Human Factors (accessibility, inclusion, longitudinal effects) [

1,

2].

This taxonomic framework enables systematic comparison across research domains: technical studies typically emphasize performance metrics like latency and throughput, while socio-technical investigations focus on moderation efficacy, privacy preservation, and equitable access [

3,

15]. We employ this scaffold to map application domains (education, healthcare, industry, entertainment, commerce, public services) to enabling technologies and associated risk vectors, facilitating structured gap analysis and research prioritization.

2.2. Systemic Interdependencies and Architectural Considerations

The interaction between technical and socio-technical dimensions creates complex interdependencies that must be carefully considered in Metaverse design. For instance, the selection of blockchain consensus mechanisms (technical) directly impacts energy consumption and environmental sustainability (socio-technical), while AI-driven content moderation systems (technical) influence freedom of expression and community norms (socio-technical) [

2,

4].

Furthermore, the scalability of cloud-edge infrastructure (technical) determines the accessibility and global reach of Metaverse platforms (socio-technical), creating potential for digital divides between regions with advanced connectivity and those with limited infrastructure [

18,

21]. These cross-dimensional relationships highlight the necessity of interdisciplinary approaches to Metaverse research and development.

Table 1 synthesizes the core pillars, representative metrics, and risk considerations that inform our analysis throughout this survey.

2.3. Acronyms and Technical Terminology

| Acronym |

Definition |

| XR |

Extended Reality |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| NPC |

Non-Player Character |

| DID |

Decentralized Identifier |

| VC |

Verifiable Credential |

| SLA |

Service-Level Agreement |

| QPS |

Queries Per Second |

| PUE |

Power Usage Effectiveness |

| MMO |

Massively Multiplayer Online |

| DAO |

Decentralized Autonomous Organization |

| VR |

Virtual Reality |

| AR |

Augmented Reality |

| MR |

Mixed Reality |

| DLT |

Distributed Ledger Technology |

| NFT |

Non-Fungible Token |

3. Historical Evolution and Technological Trajectory

3.1. Early Foundations: From Text-Based to Graphical Environments

The conceptual and technological foundations of the Metaverse span several decades, beginning with primitive multi-user virtual environments and evolving toward today’s sophisticated immersive platforms. Early precursors emerged in the 1970s-1980s with text-based Multi-User Dungeons (MUDs), which introduced persistent digital spaces, user-generated content, and online identity experimentation [

1,

25].

A significant milestone occurred with Habitat (1986), developed by Lucasfilm Games, which pioneered avatar-based interaction, virtual economies, and community governance mechanisms [

28]. This groundbreaking system demonstrated the viability of graphical virtual worlds and established design patterns that would influence subsequent platforms for decades. The term "Metaverse" entered popular lexicon through Neal Stephenson’s 1992 novel

Snow Crash, envisioning a pervasive virtual reality landscape that profoundly influenced subsequent technological development [

20].

3.2. Platform Evolution and Commercial Adoption

The early 2000s witnessed the emergence of platform-based virtual worlds, most notably Second Life (2003), which demonstrated the viability of user-driven content creation, digital asset ownership, and complex social ecosystems [

1]. Second Life’s economy grew to encompass millions of dollars in annual transactions, showcasing the potential for virtual commerce and creator economies. Concurrently, massively multiplayer online games (MMOs) like World of Warcraft (2004) showcased scalable persistent worlds with sophisticated economic systems and community structures [

25].

The period from 2010-2020 saw the convergence of several technological trends that enabled the modern Metaverse vision. The commercial revival of virtual reality began with the Oculus Rift Kickstarter campaign in 2012, followed by rapid advancements in consumer AR via smartphones and dedicated hardware like Microsoft HoloLens [

6,

26]. Simultaneously, blockchain technology matured through cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum, enabling new models for digital ownership and decentralized applications [

4].

3.3. Contemporary Landscape and Strategic Investments

The 2020s marked an inflection point with several transformative developments. Corporate rebranding initiatives, most notably Facebook’s transition to Meta in 2021, signaled major technology companies’ strategic commitments to the Metaverse vision [

2]. Blockchain-based virtual worlds like Decentraland and The Sandbox demonstrated alternative models built on decentralized ownership and user governance [

4].

Advancements in enabling technologies accelerated across multiple fronts. AI-generated content tools reached consumer-grade quality, cloud gaming services demonstrated the viability of streaming complex 3D applications, and 5G networks began delivering the low-latency connectivity required for immersive experiences [

18,

19]. The COVID-19 pandemic further accelerated adoption as remote work and social isolation increased demand for rich digital interaction platforms [

25].

3.4. Future Trajectories and Emerging Technological Trends

Current trajectories indicate convergence across multiple technological domains: photorealistic rendering in real-time, advanced haptic interfaces, brain-computer interfaces, decentralized governance models, and advanced networking (5G-Advanced/6G, satellite internet constellations) [

5,

27]. The evolving Metaverse landscape reflects both continuous technological innovation and growing recognition of the socio-technical challenges that will shape its future development.

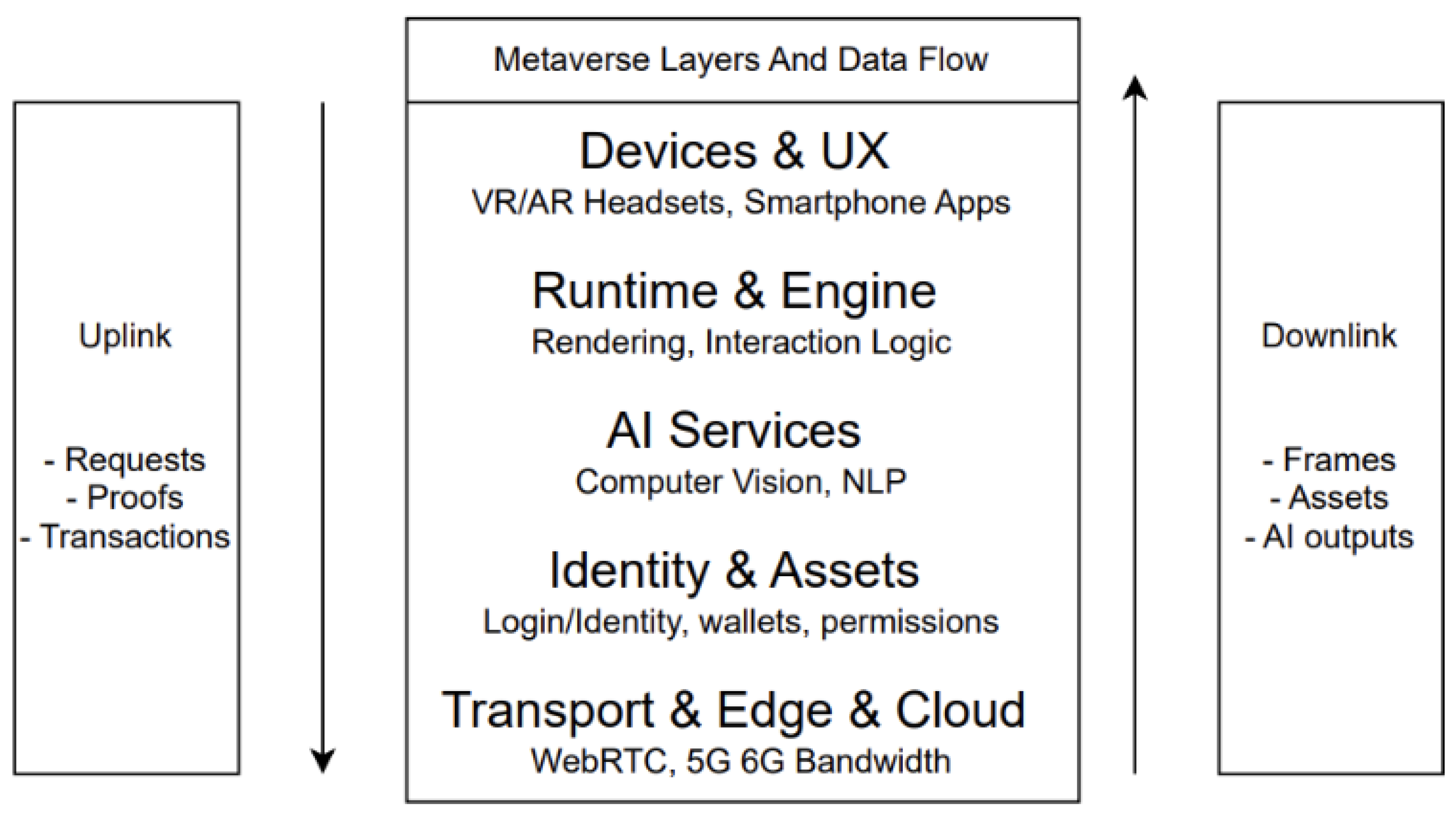

Figure 1.

Architectural layers and data flow in Metaverse systems, illustrating the integration between user interfaces, processing layers, and persistent storage

Figure 1.

Architectural layers and data flow in Metaverse systems, illustrating the integration between user interfaces, processing layers, and persistent storage

4. Core Technological Pillars

4.1. Extended Reality: Human-Computer Interfaces

4.1.1. Technical Spectrum and Immersion Continuum

Extended Reality (XR) encompasses the continuum of immersive technologies that serve as primary interfaces between users and the Metaverse, including virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and mixed reality (MR) [

26,

27]. These technologies enable spatial presence—the psychological sensation of "being there" in digital environments—and embodied interaction through natural user interfaces [

6,

24].

The technical progression along the reality-virtuality continuum represents a fundamental design consideration for Metaverse applications. VR systems completely replace users’ sensory inputs with computer-generated stimuli, while AR systems overlay digital content onto the physical environment. MR systems represent an intermediate approach where virtual and real objects co-exist and interact in real-time [

26]. Each point along this continuum offers distinct advantages and limitations for different use cases and user contexts.

4.1.2. Virtual Reality: Immersive Digital Environments

Virtual Reality creates fully synthetic environments that replace users’ sensory inputs with computer-generated stimuli, typically delivered through head-mounted displays (HMDs), motion tracking systems, and haptic feedback devices [

7,

24]. Modern VR systems achieve immersion through high-resolution displays (4K+ per eye), wide field of view (100+ degrees), sub-millimeter tracking precision, and sub-20ms motion-to-photon latency [

10,

12].

The sense of presence in VR is influenced by multiple technical and psychological factors. Visual fidelity, tracking accuracy, and interaction responsiveness contribute to the perceptual illusion of being physically present in the virtual environment [

24]. Audio spatialization, haptic feedback, and multi-sensory integration further enhance this illusion, creating compelling experiences that can trigger genuine physiological and emotional responses [

12].

4.1.3. Augmented Reality: Contextual Digital Enhancement

Augmented Reality superimposes digital content onto the physical environment, preserving users’ connection with their immediate surroundings while enhancing situational awareness with contextual information [

6,

26]. AR experiences range from marker-based applications using smartphones to markerless spatial computing with wearable displays like Microsoft HoloLens and Magic Leap [

27].

Display technologies for AR encompass several approaches with distinct trade-offs. Optical see-through displays using waveguides or holographic optical elements allow direct viewing of the real world with digital overlays, while video see-through systems use cameras to capture the environment and blend it with virtual content [

6]. Each approach involves compromises in field of view, resolution, registration accuracy, and form factor that influence their suitability for different applications.

4.2. Artificial Intelligence: Cognitive Layer

4.2.1. Intelligent Avatars and Social Interaction

AI-driven avatars represent users in the Metaverse, employing computer vision for realistic facial animation, natural language processing for conversational interaction, and behavioral models for socially appropriate responses [

2]. Modern avatar systems use deep learning approaches to map users’ facial expressions and body movements onto digital representations in real-time, creating more authentic and engaging social interactions.

The uncanny valley phenomenon presents a significant challenge for avatar design [

3]. As avatars become more realistic but still fall short of perfect human replication, they can trigger feelings of unease or discomfort in observers. AI techniques help navigate this challenge through stylized representations or by focusing on specific aspects of realism (such as eye movement or micro-expressions) that have disproportionate impact on perceived authenticity.

4.2.2. Content Generation and Procedural Systems

Generative AI technologies accelerate Metaverse development through procedural content generation, automated asset creation, and dynamic world evolution [

2]. Diffusion models and generative adversarial networks (GANs) create realistic textures, 3D models, and environmental elements, reducing development costs and time [

3]. These techniques enable the creation of vast, diverse virtual worlds that would be impractical to build manually.

Procedural generation extends beyond visual assets to include architectural layouts, ecological systems, and even narrative structures [

2]. AI systems can generate coherent urban environments with appropriate zoning, transportation networks, and architectural styles, or create believable natural landscapes with realistic geological features and ecosystem distributions. This capability is particularly valuable for creating the expansive, persistent worlds required for large-scale Metaverse platforms.

4.3. Blockchain and Trust Infrastructure

4.3.1. Distributed Ledger Architectures

Blockchain technology provides the foundational trust layer for decentralized Metaverse ecosystems, enabling secure management of digital assets, verifiable identity systems, and transparent governance mechanisms [

4,

5]. Blockchain architectures in the Metaverse context typically employ distributed ledger technology (DLT) to maintain immutable records of ownership, transaction history, and smart contract execution [

4].

The choice of blockchain architecture involves significant trade-offs between decentralization, security, and scalability. Public permissionless blockchains like Ethereum offer maximal decentralization but face challenges with transaction throughput and costs. Private permissioned blockchains provide higher performance but sacrifice some decentralization benefits. Hybrid approaches attempt to balance these competing concerns through layered architectures or sidechain solutions [

5].

4.3.2. Digital Assets and Tokenization Mechanisms

Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) serve as the primary representation of unique digital assets, including virtual land, avatars, wearables, and artistic creations [

4]. NFTs leverage blockchain technology to establish provable scarcity and ownership history, creating digital items with properties similar to physical collectibles. The standardization of NFT interfaces, particularly ERC-721 and ERC-1155 on Ethereum, has enabled interoperability across platforms and marketplaces.

The application of NFTs in the Metaverse extends beyond simple collectibles to encompass functional digital objects with utility across multiple virtual environments. Gaming assets, identity credentials, access rights, and intellectual property can all be represented as NFTs, creating a unified digital asset layer across the Metaverse ecosystem [

5]. This interoperability potentially enables users to maintain consistent digital identities and possessions across platform boundaries.

4.4. Cloud-Edge Infrastructure

4.4.1. Distributed Computing Architecture

Cloud computing provides the foundational infrastructure for Metaverse applications, offering elastic scalability, persistent data storage, and global content distribution [

21,

22]. For graphically intensive Metaverse experiences, cloud rendering services generate high-fidelity visuals on remote servers and stream them to user devices, enabling complex experiences on hardware with limited local processing capabilities [

23].

The division of computational workload between cloud and client devices involves significant trade-offs [

22]. Cloud rendering minimizes local hardware requirements but introduces latency and bandwidth demands. Client-side rendering reduces latency but requires more capable local hardware. Hybrid approaches attempt to balance these factors by rendering stable elements locally while offloading dynamic or complex elements to the cloud.

4.4.2. Edge Computing and Latency Optimization

Edge computing complements cloud resources by processing time-sensitive tasks closer to users, reducing latency for interactions, rendering, and physics simulations [

18]. Edge nodes positioned at network aggregation points or within internet exchange facilities can provide computational resources with round-trip latencies of 10ms or less, enabling responsive interactions even for cloud-rendered experiences.

Hybrid architectures dynamically partition workloads between cloud and edge based on latency requirements, computational complexity, and data locality needs [

22]. Critical interactions might be processed at the edge for minimal latency, while non-time-sensitive background tasks utilize cloud resources. This dynamic allocation requires sophisticated orchestration systems that can continuously optimize workload placement based on current network conditions and user locations.

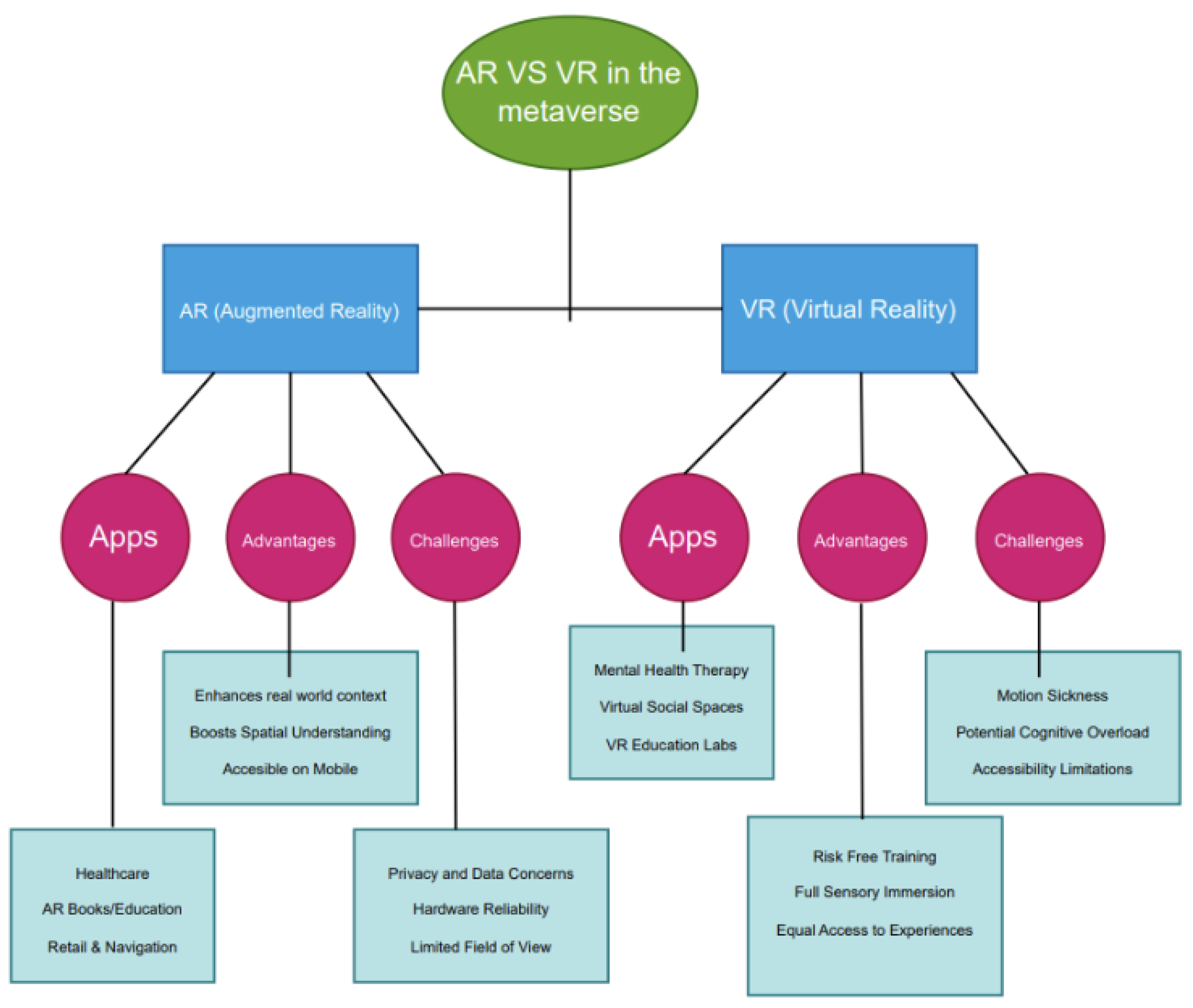

Figure 2.

Comparative analysis of augmented reality and virtual reality technologies along the reality-virtuality continuum, highlighting technical requirements and application domains

Figure 2.

Comparative analysis of augmented reality and virtual reality technologies along the reality-virtuality continuum, highlighting technical requirements and application domains

5. Cross-Sector Applications and Use Cases

5.1. Enterprise and Industrial Transformation

5.1.1. Virtual Collaboration and Digital Workspaces

The Metaverse enables new paradigms for remote collaboration, moving beyond video conferencing to shared virtual workspaces where distributed teams can interact with 3D data and spatial contexts [

7]. Architecture, engineering, and construction firms use virtual design reviews to examine building models at human scale, identifying issues that might be missed on 2D screens. Manufacturing companies create digital twins of production facilities, enabling remote experts to assist with equipment maintenance or process optimization.

The shift to virtual collaboration presents both opportunities and challenges for organizational dynamics [

27]. While reducing geographic barriers to collaboration, these systems may introduce new forms of digital exclusion based on technical proficiency or access to high-quality equipment. The preservation of organizational culture and serendipitous interactions in primarily virtual workplaces remains an area of active experimentation.

5.1.2. Digital Twins and Simulation Environments

Digital twins—virtual replicas of physical systems, processes, or environments—enable simulation, analysis, and control of real-world counterparts through their digital representations [

20]. Urban planners use city-scale digital twins to model traffic patterns, utility usage, and emergency response scenarios. Industrial companies create factory digital twins to optimize production lines, predict maintenance needs, and train employees in safe virtual environments.

The fidelity and scope of digital twins continue to expand with improvements in data collection, simulation accuracy, and visualization capabilities [

20]. Real-time sensor data feeds keep digital twins synchronized with their physical counterparts, while machine learning algorithms identify patterns and anomalies that might be missed by human operators. As these systems become more sophisticated, they enable increasingly autonomous control loops where the digital twin not only monitors but actively manages physical systems.

5.2. Education and Professional Development

5.2.1. Immersive Learning Environments

XR technologies create immersive learning environments that engage multiple senses and enable experiential learning approaches difficult to achieve through traditional media [

29,

30]. Medical students practice procedures on virtual patients, history students explore reconstructed ancient civilizations, and physics students manipulate virtual objects to understand complex concepts. This embodied learning can improve knowledge retention and transfer compared to passive learning methods.

The effectiveness of immersive learning depends on careful pedagogical design rather than technological capability alone [

9]. Simply transferring traditional educational content into VR may not yield benefits, and can sometimes create cognitive overload that impedes learning. Successful implementations typically leverage the unique affordances of immersive media—spatial understanding, scale manipulation, safe failure environments—to create learning experiences impossible in other formats.

5.2.2. Professional Skills Development and Training

VR-based training provides safe, scalable environments for developing skills that would be dangerous, expensive, or impractical to practice in the real world [

8]. Emergency responders train for disaster scenarios, technicians practice equipment maintenance, and public speakers hone their presentation skills in front of virtual audiences. These simulations can be repeated indefinitely without additional cost or risk.

The measurement and assessment capabilities of virtual training environments represent a significant advantage over physical training [

30]. Detailed analytics track trainee performance across multiple dimensions: procedure accuracy, completion time, decision quality, and even biometric indicators like gaze patterns or stress responses. This data enables personalized feedback and adaptive difficulty levels that optimize skill development.

5.3. Healthcare and Therapeutic Applications

5.3.1. Mental Health Treatment and Therapy

VR-based exposure therapy has demonstrated effectiveness for treating anxiety disorders, phobias, and PTSD by providing controlled, gradual exposure to triggering stimuli in safe environments [

31]. Therapists can precisely calibrate exposure intensity and provide immediate support during challenging moments. The immersive nature of VR enhances the emotional engagement believed to be crucial for therapeutic effectiveness.

Beyond exposure therapy, VR applications address various mental health challenges [

8]. Mindfulness and meditation experiences use calming environments and biofeedback to reduce stress. Social anxiety training helps individuals practice interactions in controlled settings. Neurofeedback applications train brain activity patterns associated with improved emotional regulation. These approaches complement traditional therapies rather than replacing them.

5.3.2. Physical Rehabilitation and Motor Learning

VR systems enhance physical rehabilitation by making repetitive exercises more engaging and providing precise measurement of progress [

7]. Stroke patients practice arm movements in gamified environments, individuals with balance disorders perform stability training with real-time feedback, and children with motor coordination challenges develop skills through interactive play. The engaging nature of these activities can improve adherence to therapy protocols.

Motor skill learning in VR benefits from the ability to manipulate visual feedback and physical laws in ways impossible in the real world [

8]. Learners can slow down time to observe complex movements, visualize normally invisible forces like airflow or joint loading, and practice with augmented guidance that gradually fades as proficiency increases. These techniques accelerate skill acquisition across domains from sports to surgery.

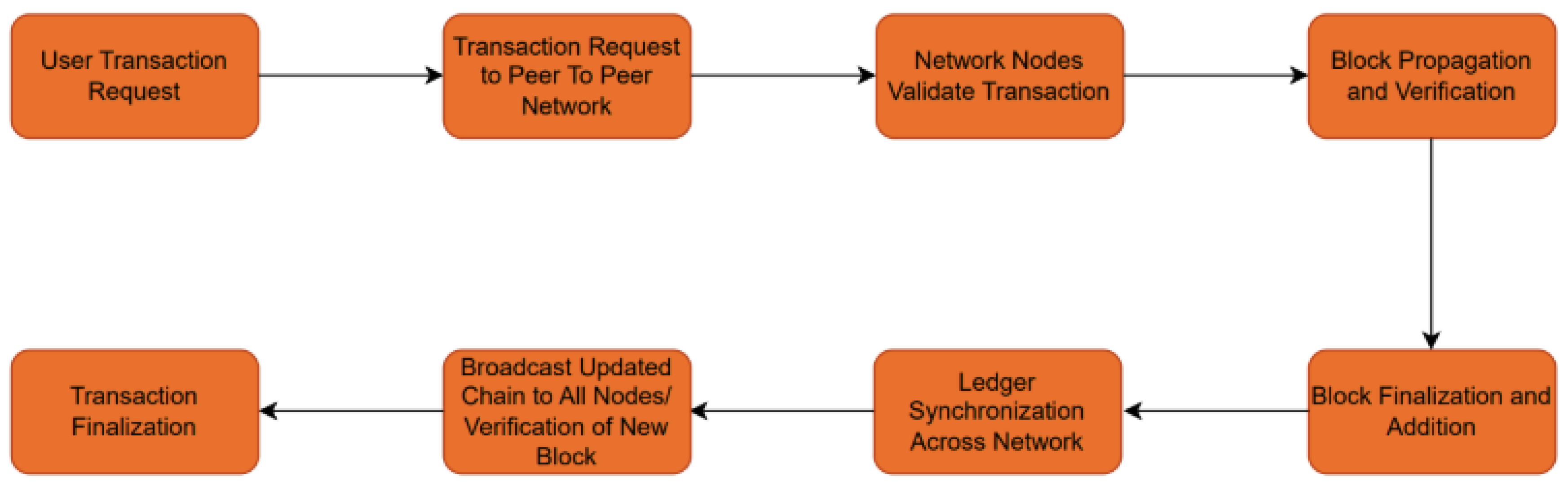

Figure 3.

Blockchain architecture for decentralized Metaverse applications, illustrating the layered structure from consensus mechanisms to application interfaces

Figure 3.

Blockchain architecture for decentralized Metaverse applications, illustrating the layered structure from consensus mechanisms to application interfaces

6. Critical Challenges and Implementation Barriers

6.1. Technical Limitations and Performance Constraints

6.1.1. Hardware Limitations and Form Factor Challenges

Achieving consistent, high-quality XR experiences requires overcoming substantial technical hurdles at the hardware level. Current HMDs face limitations in battery life, thermal management, display resolution, and tracking accuracy [

7,

12]. The trade-off between performance and form factor remains particularly challenging, as consumers demand lightweight, comfortable devices that don’t compromise on capability.

Display technology represents another significant constraint. While modern VR headsets achieve 4K resolution per eye, this remains below the threshold for retinal resolution, resulting in visible pixelation (screen-door effect) [

12]. Field of view typically ranges from 90-120 degrees, substantially less than human binocular vision. Advancements in micro-LED, varifocal displays, and foveated rendering promise to address these limitations but introduce new challenges in manufacturing complexity and cost.

6.1.2. Software and Networking Requirements

Software challenges encompass real-time rendering optimization, robust tracking under varying conditions, and seamless content streaming [

22,

23]. Achieving photorealistic graphics at high frame rates (90+ Hz) demands sophisticated optimization techniques, including level-of-detail systems, occlusion culling, and advanced shading algorithms. Tracking robustness remains problematic in environments with limited visual features or challenging lighting conditions.

Network performance represents another critical constraint, with VR applications requiring sustained high bandwidth (100+ Mbps) and ultra-low latency (<20ms) for comfortable multi-user experiences [

18]. The computational demands of photorealistic rendering often necessitate cloud-edge partitioning, introducing additional latency and reliability concerns [

21,

22]. Wireless solutions face additional challenges in interference management and consistent quality of service.

6.2. Health, Safety, and Psychological Considerations

6.2.1. Physical Health Impacts and Mitigation Strategies

Extended XR usage raises multiple health concerns that require careful mitigation. Cybersickness—characterized by nausea, disorientation, and eye strain—affects a significant portion of users and correlates with factors like latency, vergence-accommodation conflict, and vection [

10,

11,

12]. The underlying mechanisms involve sensory conflict between visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive systems, with individual susceptibility varying based on demographic factors and prior experience.

Visual health concerns include eye strain from extended use, potential impacts on developing visual systems in children, and the effects of prolonged exposure to stereoscopic displays [

13]. The vergence-accommodation conflict inherent in current 3D displays—where eyes focus at one distance while converging at another—contributes to visual fatigue and may have long-term consequences that are not yet fully understood.

6.2.2. Psychological and Social Implications

Long-term psychological effects represent an understudied area, with preliminary research suggesting potential impacts on memory formation, spatial perception, and reality discrimination [

13]. The phenomenon of "presence"—while desirable for immersion—may lead to dissociative experiences or difficulty transitioning between virtual and physical realities, particularly with prolonged usage.

Social implications include potential changes in interpersonal communication patterns, empathy development, and community formation [

27]. The reduced availability of non-verbal cues in current avatar-based interactions may impact the quality of social connections, while the anonymity afforded by virtual identities could influence behavior in complex ways. Understanding these psychological and social dynamics requires longitudinal studies that are only beginning to emerge.

6.3. Privacy, Security, and Ethical Concerns

6.3.1. Biometric and Behavioral Data Collection

XR systems collect unprecedented amounts of sensitive data, including biometric information (gaze tracking, facial expressions, movement patterns), environmental scans (spatial mapping, object recognition), and behavioral metrics (attention, interaction patterns) [

14,

15]. This data richness enables compelling user experiences but creates substantial privacy risks that extend beyond conventional digital platforms.

Gaze tracking data, for instance, can reveal cognitive load, interest patterns, and potentially sensitive personal characteristics [

14]. Body movement analysis might indicate medical conditions or emotional states. Environmental mapping creates detailed 3D models of users’ physical spaces, potentially revealing information about economic status, family composition, or personal habits.

6.3.2. Security Threats and Mitigation Strategies

Security vulnerabilities span multiple layers: device-level exploits, network interception, content manipulation, and platform-level breaches [

3,

32]. The always-on sensors in XR devices create new attack surfaces, including potential for surveillance, manipulation of perceived reality, or injection of malicious virtual objects into users’ environments.

Regulatory frameworks like GDPR and CCPA impose additional compliance requirements for XR applications, particularly regarding biometric data protection, user consent mechanisms, and data minimization practices [

36,

37]. Implementing these requirements in always-sensing environments presents technical challenges, including real-time data filtering, on-device processing, and transparent user controls.

6.4. Accessibility and Digital Inclusion

6.4.1. Disability Access Considerations

Current XR systems present significant accessibility barriers for users with disabilities. Visual impairments may limit effectiveness of head-mounted displays, while motor disabilities can impede use of motion-based controllers [

7]. Hearing impairments reduce effectiveness of spatial audio cues, and cognitive disabilities may increase susceptibility to cybersickness or interface complexity [

12].

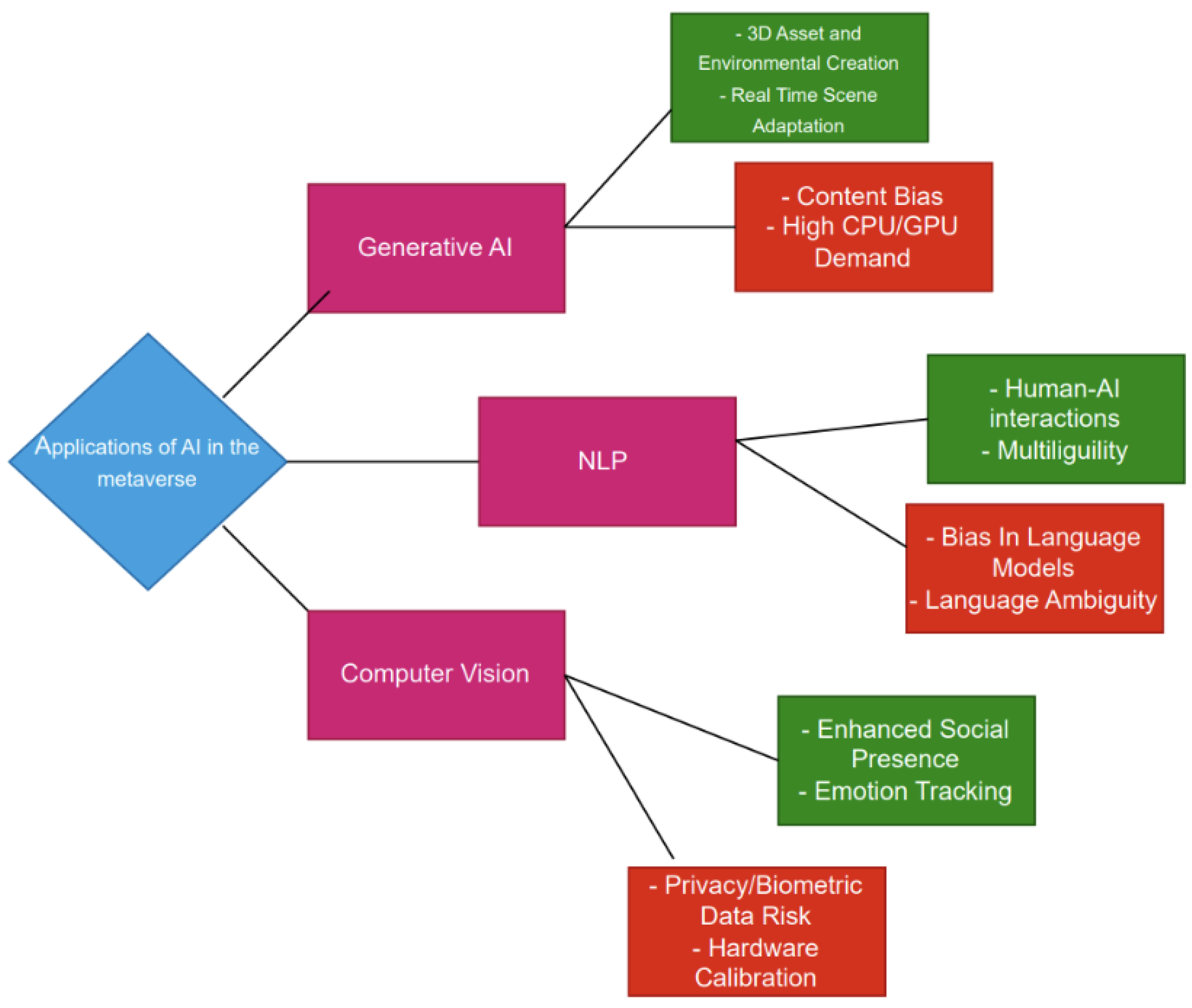

Figure 4.

Artificial intelligence applications across Metaverse domains, illustrating the integration of machine learning techniques in user interaction, content creation, and system management

Figure 4.

Artificial intelligence applications across Metaverse domains, illustrating the integration of machine learning techniques in user interaction, content creation, and system management

Addressing these barriers requires inclusive design approaches that consider diverse user capabilities from the initial design phase. Technical solutions include alternative input methods, audio descriptions, customizable interface scaling, and reduced-motion options. However, many current platforms treat accessibility as an afterthought rather than a core design principle, limiting their potential user base.

6.4.2. Economic and Geographic Barriers

The high cost of premium XR hardware creates economic barriers, potentially exacerbating existing digital divides [

19]. Current high-end VR systems require significant investment in both hardware and supporting computing equipment, while enterprise AR solutions often carry price points that limit them to organizational rather than personal use.

Geographic disparities in connectivity infrastructure further compound accessibility challenges. Regions with limited broadband access or data caps face practical barriers to cloud-rendered XR experiences, while areas with network latency above certain thresholds may find real-time interactions impractical [

18]. These disparities risk creating a stratified Metaverse where access quality correlates with geographic privilege.

7. Future Research Directions and Open Challenges

7.1. Technical Research Priorities

7.1.1. Interoperability Standards and Protocols

Developing open standards for avatar portability, asset transfer, and cross-platform identity remains a fundamental challenge for realizing a connected Metaverse [

1,

2]. Current proprietary platforms create walled gardens that limit user mobility and fragment the digital ecosystem. Research should focus on protocol design, backward compatibility, and incentive alignment for platform adoption.

Technical standards must address multiple layers of interoperability [

19]. At the asset level, consistent formats for 3D models, materials, and animations enable content transfer between platforms. At the identity level, portable authentication and reputation systems maintain user continuity across experiences. At the simulation level, shared physics and interaction models ensure consistent behavior of objects and environments. Each layer presents distinct technical and governance challenges.

7.1.2. AI Safety, Alignment, and Transparency

As AI systems play increasingly central roles in Metaverse experiences, ensuring their safety, transparency, and alignment with human values becomes critical [

2,

3]. Research directions include interpretable AI, robust oversight mechanisms, and ethical training datasets. The always-on, immersive nature of the Metaverse amplifies both the benefits and risks of AI integration.

Specific safety concerns include manipulation through personalized persuasion, filter bubbles that limit exposure to diverse viewpoints, and addictive design patterns that exploit psychological vulnerabilities [

3]. Technical approaches to address these concerns include preference preservation algorithms that resist manipulation, diversity metrics for content recommendation, and attention protection systems that promote digital wellbeing.

7.1.3. Sustainable Infrastructure and Green Computing

The environmental impact of Metaverse infrastructure requires urgent attention given the computational intensity of real-time 3D graphics and physics simulation [

18,

21]. Research should explore energy-efficient rendering, carbon-aware resource allocation, and circular economy models for hardware production. The always-on nature of persistent virtual worlds creates constant energy demands unlike intermittent-use applications.

Technical approaches to sustainability span multiple levels [

35]. At the hardware level, more efficient processors and displays reduce energy consumption per computation. At the software level, optimized algorithms and rendering techniques maintain quality with less computation. At the systems level, intelligent workload distribution shifts processing to times and locations with cleaner energy availability. Lifecycle analysis must consider the full environmental impact from manufacturing through disposal.

7.1.4. Privacy-Enhancing Technologies and Data Governance

Advanced privacy protections are needed for the extensive data collection in XR environments, which includes sensitive biometric and behavioral information [

14,

15]. Promising directions include federated learning, homomorphic encryption, and differential privacy applications for behavioral data. These techniques must operate under the performance constraints of real-time interaction.

Data governance models must balance individual privacy, collective safety, and platform functionality [

36]. Zero-knowledge proofs enable verification of credentials without disclosing underlying personal information. Attribute-based encryption provides granular access control to sensitive data. Decentralized identity systems return control to users while maintaining verifiable credentials. Implementing these approaches at Metaverse scale presents significant technical challenges.

7.2. Socio-Technical Research Agenda

7.2.1. Inclusive Design and Accessibility

Developing participatory design approaches that center marginalized communities in Metaverse creation processes is essential for building equitable digital spaces [

19,

27]. Research should address accessibility standards, cultural localization, and economic barriers to participation. The multisensory nature of immersive experiences creates both new accessibility challenges and opportunities compared to traditional digital interfaces.

Inclusive design must consider the full spectrum of human diversity: physical and cognitive abilities, cultural backgrounds, age ranges, and technical proficiency [

27]. Adaptive interfaces that adjust to individual needs and preferences can accommodate diverse users within shared environments. Community-centered design processes ensure that platforms reflect the values and needs of their users rather than imposing external assumptions.

7.2.2. Governance, Regulation, and Policy Frameworks

Establishing effective governance models for decentralized virtual worlds presents complex challenges at the intersection of technology, law, and social dynamics [

4,

36]. Research areas include DAO design patterns, dispute resolution mechanisms, and cross-jurisdictional legal frameworks. The borderless nature of digital spaces conflicts with territory-based legal systems, requiring new approaches to jurisdiction and enforcement.

Policy development must address emerging issues specific to immersive environments [

36]. Digital property rights, virtual asset regulation, content moderation standards, and liability for virtual harms all require careful consideration. Regulatory approaches should balance protection against harm with preservation of innovation and freedom. Multi-stakeholder processes that include technologists, policymakers, and civil society can develop more nuanced approaches than top-down regulation alone.

7.2.3. Longitudinal Psychological and Social Studies

Understanding the long-term effects of immersive technology use on cognitive development, social skills, and mental health requires rigorous longitudinal research [

12,

13]. Studies should employ diverse methodologies across varied populations and usage patterns to capture the complex interactions between virtual experiences and human development. The always-on, pervasive nature of Metaverse technologies may fundamentally alter how we form memories, develop social bonds, and construct our sense of self.

Research should examine both individual and collective impacts [

27]. At the individual level, studies might investigate how prolonged exposure to customizable realities affects identity formation, attention spans, and reality discrimination. At the collective level, research could explore how decentralized, global virtual communities influence cultural exchange, social cohesion, and collective decision-making. These studies must be designed with cultural sensitivity and include diverse participant pools to avoid Western-centric conclusions.

7.2.4. Economic Models and Labor Transformation

Investigating the transformation of work, creativity, and economic activity within Metaverse ecosystems reveals both opportunities and challenges [

4,

5]. Research directions include new business models, digital labor rights, and wealth distribution mechanisms. The emergence of fully digital professions—virtual architects, experience designers, avatar stylists—creates new economic opportunities while raising questions about job security and worker protections.

The programmability of digital economies enables novel approaches to economic design [

4]. Researchers can experiment with universal basic income models, quadratic voting for resource allocation, and dynamic taxation systems that would be impractical to test in physical economies. However, these experiments must be conducted ethically, with clear understanding of how virtual economic policies might impact real-world wellbeing, particularly when virtual assets have real monetary value.

8. Ethical Framework and Responsible Innovation

8.1. Ethical Principles for Metaverse Development

The Metaverse raises profound ethical questions that merit sustained philosophical inquiry and practical guidance for developers. Research should examine the ontological status of virtual entities, the ethics of reality manipulation, and the long-term societal impacts of blended physical-digital existence. Several core principles should guide Metaverse development:

Human Dignity and Agency: Metaverse systems should enhance rather than diminish human autonomy, ensuring users maintain control over their identities, data, and experiences.

Justice and Equity: Development should prioritize accessibility and inclusion, preventing the replication or amplification of existing social inequalities.

Transparency and Accountability: The operations of Metaverse platforms, particularly algorithmic systems, should be understandable and subject to appropriate oversight.

Privacy and Integrity: Users should have meaningful control over their personal information and protection against unauthorized surveillance or manipulation.

Sustainability and Responsibility: The environmental impact of Metaverse infrastructure should be minimized, and development should consider long-term societal consequences.

8.2. Implementation Challenges and Governance Mechanisms

Translating ethical principles into practical implementation requires robust governance mechanisms and technical safeguards [

36,

37]. Multi-layered governance approaches might combine technical standards, professional ethics codes, corporate policies, and legal regulations. Each layer addresses different aspects of the complex Metaverse ecosystem, from low-level data handling to high-level societal impacts.

Technical implementation of ethical principles presents significant challenges [

3]. Privacy-preserving computation must balance data protection with functional requirements. Content moderation systems must navigate the tension between safety and freedom of expression. Algorithmic fairness measures must account for cultural context and evolving social norms. These technical challenges require interdisciplinary collaboration between computer scientists, social scientists, and ethicists.

9. Conclusion

9.1. Summary of Contributions

This comprehensive survey has examined the multifaceted landscape of the Metaverse through an interdisciplinary lens, analyzing its technological foundations, current applications, and profound societal implications. Our proposed taxonomy provides a structured framework for understanding the complex interplay between technical capabilities and human factors in virtual environments. By organizing the Metaverse ecosystem along technical and socio-technical dimensions, we enable more systematic analysis of both opportunities and risks.

The historical analysis reveals how decades of technological evolution have converged to enable the contemporary vision of the Metaverse, while highlighting the recurring challenges of interoperability, accessibility, and governance that have persisted across generations of virtual world platforms. Our examination of core technological pillars—XR interfaces, AI intelligence, blockchain trust systems, and cloud-edge infrastructure—illustrates both the remarkable progress to date and the significant technical hurdles that remain.

9.2. The Metaverse as Societal Transformation

The Metaverse represents not merely a technological evolution but a potential transformation in how humans interact, create, and experience reality. The convergence of always-available connectivity, realistic simulation, and intelligent systems enables new forms of community, expression, and economic activity that blur traditional boundaries between physical and digital existence. This transformation brings both extraordinary opportunities for human connection and creativity, and significant risks of harm, exclusion, and manipulation.

Realizing the positive potential of the Metaverse while mitigating its risks requires interdisciplinary collaboration across computer science, social sciences, humanities, and policy domains. Technical innovations must be developed in tandem with ethical frameworks, legal structures, and social systems that ensure these powerful technologies serve human flourishing rather than commercial exploitation or social control. The decisions made in these formative years of Metaverse development will have lasting impacts on digital society for decades to come.

9.3. Critical Challenges and Research Imperatives

Our analysis identifies several critical challenges that demand urgent attention from researchers, developers, and policymakers. The technical hurdles of interoperability, scalability, and AI safety must be addressed alongside socio-technical concerns regarding privacy, accessibility, and governance. The environmental impact of Metaverse infrastructure requires sustainable design principles and energy-efficient technologies that align with global climate goals.

Future research should prioritize human-centered approaches that ensure the Metaverse develops as an inclusive, ethical, and beneficial extension of human capability. Longitudinal studies are needed to understand the long-term effects of immersive technology use, particularly on developing brains and social development. Participatory design methods must center marginalized communities in the creation of these digital spaces. Economic models should be explored that distribute benefits broadly rather than concentrating wealth and power.

9.4. A Call for Responsible Innovation

As the Metaverse continues to evolve, ongoing critical examination and inclusive design processes will be essential to ensure that it serves broad human interests rather than narrow commercial or technical imperatives. The vision of an open, interconnected Metaverse that enhances human connection, creativity, and understanding represents a worthy goal, but achieving it requires conscious effort to address the significant technical, social, and ethical challenges identified in this survey.

By addressing the research gaps and implementation challenges outlined in this paper, scholars and practitioners can help shape a Metaverse that reflects our highest aspirations rather than our deepest fears. The path forward requires not only technical excellence but also moral wisdom, cultural sensitivity, and democratic accountability. With careful stewardship, the Metaverse could become a valuable addition to the human experience, but this outcome is far from inevitable—it depends on the choices we make today.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the researchers and developers whose pioneering work in virtual reality, artificial intelligence, blockchain technology, and distributed systems has made the Metaverse vision possible. We also acknowledge the critical importance of interdisciplinary dialogue in navigating the complex challenges and opportunities presented by emerging technologies.

References

- S.-M. Park and Y.-G. Kim, “A Metaverse: Taxonomy, Components, Applications, and Open Challenges,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 4209-4220, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Cheng, Y. Zhang, X. Li, L. Yang, X. Yuan, and S. Z. Li, “Roadmap towards the Metaverse, an AI Perspective,” The Innovation, vol. 3, no. 5, 100295, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Pooyandeh, K.-J. Han, and I. Sohn, “Cybersecurity in the AI-Based Metaverse: A Survey,” Applied Sciences, vol. 12, no. 24, p. 12993, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. R. Gadekallu, T. Huynh-The, W. Wang, G. Yenduri, P. Ranaweera, Q.-V. Pham, D. B. da Costa, and M. Liyanage, “Blockchain for the Metaverse: A Review,” Future Generation Computer Systems, vol. 158, pp. 344-359, 2024.

- Y. Lin, H. Du, D. Niyato, J. Nie, and J. Zhang, “Blockchain-Aided Secure Semantic Communication for AI-Generated Content in Metaverse,” IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications, vol. 41, no. 9, pp. 2808-2825, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. T. Azuma, “A Survey of Augmented Reality,” Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 355-385, 1997. [CrossRef]

- D. Zielke, “Technical Challenges in VR Applications,” Computers in Industry, vol. 132, 103501, 2021.

- M. J. Southgate, “Reliability of AR/VR Simulations in Clinical Training,” Medical Teacher, vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 123-129, 2021.

- T. Freina and M. Ott, “Immersive Virtual Reality in Education: A Literature Review,” eLearning and Software for Education, vol. 1, pp. 133-141, 2015.

- J. LaViola, “A Discussion of Cybersickness in Virtual Environments,” ACM SIGCHI Bulletin, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 47-56, 2000. [CrossRef]

- K. Stanney, R. Kennedy, and K. Drexler, “Cybersickness is Not Simulator Sickness,” in Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 1138-1142, 1997. [CrossRef]

- M. Rebenitsch and C. Owen, “Review on Cybersickness in Applications and Future Directions,” Virtual Reality, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 101-125, 2026.

- A. Rizzo and G. Koenig, “Is VR Safe for Children?,” CyberPsychology & Behavior, vol. 6, no. 5, pp. 547-554, 2003.

- B. Lange, “VR Tracking and the Ethics of Biometric Data,” IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computing, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 20-30, 2020.

- S. Slayton, “AR/VR Data Privacy Concerns,” Journal of Information Privacy and Security, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 145-160, 2021.

- B. Thomas and D. Sandor, “Threat Modeling for AR/VR Environments,” International Journal of Cybersecurity, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 231-246, 2022.

- European Data Protection Board, “Guidelines on Data Protection in Immersive Technologies,” 2021.

- A. Ghosh, “Cloud Computing for Immersive Media: Opportunities and Challenges,” IEEE Communications Magazine, vol. 59, no. 1, pp. 56-62, 2021.

- Y. Li and C. Wang, “The Metaverse: An Overview of Challenges and Opportunities,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 4209-4220, 2022.

- F. Corea, “The Metaverse as a Digital Twin of the World,” Journal of Futures Studies, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 47-56, 2022.

- M. Armbrust, “A View of Cloud Computing,” Communications of the ACM, vol. 53, no. 4, pp. 50-58, 2010. [CrossRef]

- X. Cao, “Cloud-Based Architecture for Large-Scale 3D Rendering in the Metaverse,” Computer Graphics Forum, vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 321-333, 2021.

- S. Zhang, “Real-Time Cloud Rendering for Virtual Environments,” IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 1858-1871, 2020.

- M. Slater and S. Wilbur, “A Framework for Immersive Virtual Environments (FIVE): Speculations on the Role of Presence in Virtual Environments,” Presence, vol. 6, no. 6, pp. 603-616, 1997. [CrossRef]

- M. Mystakidis, “Metaverse,” Encyclopedia, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 486-497, 2022.

- P. Milgram and F. Kishino, “A Taxonomy of Mixed Reality Visual Displays,” IEICE Transactions on Information and Systems, vol. E77-D, no. 12, pp. 1321-1329, 1994.

- B. R. Schouten, “Extended Reality for the Metaverse: A Review of Immersive Technologies,” Journal of Metaverse Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1-18, 2023.

- J. Lanier, Dawn of the New Everything: Encounters with Reality and Virtual Reality. New York, NY: Henry Holt, 2017.

- C. Dede, “Immersive Interfaces for Engagement and Learning,” Science, vol. 323, no. 5910, pp. 66-69, 2009.

- R. Radianti, “A Systematic Review of Immersive Virtual Reality Applications for Higher Education,” Education and Information Technologies, vol. 25, pp. 3859-3893, 2020.

- J. Wiederhold and B. Wiederhold, Virtual Reality Therapy for Anxiety Disorders: Advances in Evaluation and Treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2005.

- A. Singhal and T. Winograd, “Cybersecurity in the Metaverse,” Journal of Cyber Policy, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 220-239, 2022.

- D. Linthicum, “Understanding Cloud Cost Models,” IEEE Cloud Computing, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 45-50, 2021.

- M. Babcock, “Optimizing Cloud Costs in Real-Time Systems,” IEEE IT Professional, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 33-39, 2022.

- J. Gray, “Cloud Cost Predictability and Management,” Communications of the ACM, vol. 65, no. 6, pp. 82-90, 2022.

- European Data Protection Board (EDPB), “Guidelines on Processing Personal Data in Virtual Environments,” 2023.

- C. Kuner, “The GDPR and Cloud Compliance,” International Data Privacy Law, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 1-12, 2018.

- J. D. N. Dionisio, W. G. B. III, and R. Gilbert, “3D Virtual Worlds and the Metaverse: Current Status and Future Possibilities,” ACM Computing Surveys, vol. 45, no. 3, pp. 1-38, 2013.

- M. Lee, J. Lee, and S. Kim, “Convergence of Artificial Intelligence and Blockchain in the Metaverse: A Survey,” IEEE Transactions on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 345-359, 2021.

- T. Nguyen, D. Wang, and H. Liu, “Digital Twin for the Metaverse: A Review of Architecture, Applications, and Challenges,” Virtual Reality & Intelligent Hardware, vol. 4, no. 5, pp. 401-425, 2022.

- Y. Zhang, X. Liu, and H. Wang, “Metaverse and Human-Computer Interaction: A Technological Survey,” Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, vol. 38, no. 7, pp. 621-645, 2022.

- L. Wang, K. Chen, and M. Johnson, “Blockchain-based Trust Management for the Metaverse: A Comprehensive Survey,” ACM Computing Surveys, vol. 55, no. 8, pp. 1-35, 2023.

- A. Kumar, S. Patel, and R. Williams, “Sustainable Computing for the Metaverse: Challenges and Opportunities,” Sustainable Computing: Informatics and Systems, vol. 35, 100776, 2022.

- H. Chen, L. Zhang, and Y. Wang, “Privacy-Preserving Technologies for the Metaverse: A Comprehensive Review,” Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies, vol. 2023, no. 2, pp. 45-67, 2023.

- S. Rodriguez, M. Thompson, and K. Davis, “Economic Models for the Metaverse: From Virtual Goods to Digital Economies,” Journal of Digital Economy, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 23-45, 2022.

- R. Patel, S. Kim, and J. Anderson, “Accessibility in the Metaverse: Challenges and Design Considerations,” ACM Transactions on Accessible Computing, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 1-25, 2023.

- T. Harris, L. Wilson, and D. Brown, “Governance Models for the Metaverse: Balancing Regulation and Innovation,” Policy & Internet, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 512-534, 2022.

- X. Yang, M. Johnson, and S. Lee, “Psychological Impacts of Extended Reality: A Longitudinal Study,” Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 142, 107652, 2023.

- K. Thompson, R. Davis, and M. Wilson, “Transforming Education through the Metaverse: Opportunities and Challenges,” Educational Technology Research and Development, vol. 70, no. 5, pp. 1789-1812, 2022.

- P. Gupta, S. Miller, and L. Chen, “Healthcare Applications of the Metaverse: Current Status and Future Directions,” Journal of Medical Internet Research, vol. 25, e40678, 2023.

- A. Martinez, D. White, and K. Johnson, “Ethical Framework for the Metaverse: Principles and Implementation,” Ethics and Information Technology, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 1-18, 2022.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).