1. Introduction

Cold work tool steels represent a cornerstone of modern manufacturing, prized for their exceptional hardness and wear resistance that make them indispensable for high-stress applications such as cutting, stamping, and forming [

1,

2,

3]. The performance and service life of these critical tools, however, are not dictated by their bulk properties alone, but are fundamentally limited by the integrity of their surface. Despite their inherent strength, these steels are often plagued by surface-related failure mechanisms—including abrasion, fatigue, and corrosion—which can severely curtail their operational efficiency and lead to premature, costly tool failure [

2,

4,

5].

To overcome these surface limitations, a variety of surface engineering techniques have been developed to forge a hard, resilient surface layer while preserving the tough inner core [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Among these, thermochemical treatments like nitriding are paramount. However, conventional methods applied to high-performance steels like DC53 present significant challenges. High-temperature gas nitriding can induce dimensional distortion, while salt bath nitriding, though efficient, relies on toxic cyanide salts, posing environmental and safety concerns. This has spurred the drive for cleaner, more precise, and highly controllable surface modification technologies.

Plasma nitriding has emerged as a superior, environmentally friendly alternative, utilizing ionized gas to diffuse nitrogen into the steel surface with unparalleled control. Yet, harnessing its full potential requires navigating a delicate balance of process parameters. A primary challenge is managing the process temperature to avoid compromising the core hardness of the steel. Furthermore, the formation of the "white layer"—a hard but potentially brittle compound layer—must be meticulously controlled. An excessively thick white layer can lead to spalling and a catastrophic loss of toughness [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. The key to success lies in the precise manipulation of the plasma chemistry, where the ratio of hydrogen to nitrogen in the gas mixture stands out as one of the most critical, yet complex, variables.

This study, therefore, aims to systematically investigate the influence of the hydrogen-to-nitrogen ratio on the evolution of surface properties in DC53 tool steel during a low-temperature plasma nitriding process. By varying the H2 flow rate while keeping other parameters constant, we seek to establish a clear processing-structure-property relationship. This work provides a comprehensive analysis of the resulting microstructure, hardness, and tribological behavior, offering crucial insights for optimizing the plasma nitriding process to significantly enhance the durability and reliability of modern cold work tooling.

2. Materials and Methods

The substrate material used in this study was DC53 cold work tool steel, machined into specimens with a diameter of 24 mm and a thickness of 6.4 mm. The nominal chemical composition of the steel was approximately 1.0% C, 8.0% Cr, 2.0% Mo, 1.0% Si, 0.40% Mn, and trace amounts of V. Prior to surface treatment, the specimens were prepared by mechanical polishing. The surfaces were sequentially ground using silicon carbide (SiC) abrasive papers with grit sizes of 600, 800, 1000, 1200, and 1500. Subsequently, they were polished with 3 µm and 1 µm aluminum oxide powders to achieve a mirror-like finish. Immediately after polishing, the samples underwent a two-step ultrasonic cleaning process, first in acetone and then in methanol, for 10 minutes each. Finally, the cleaned specimens were dried with nitrogen gas before being promptly loaded into the plasma nitriding system.

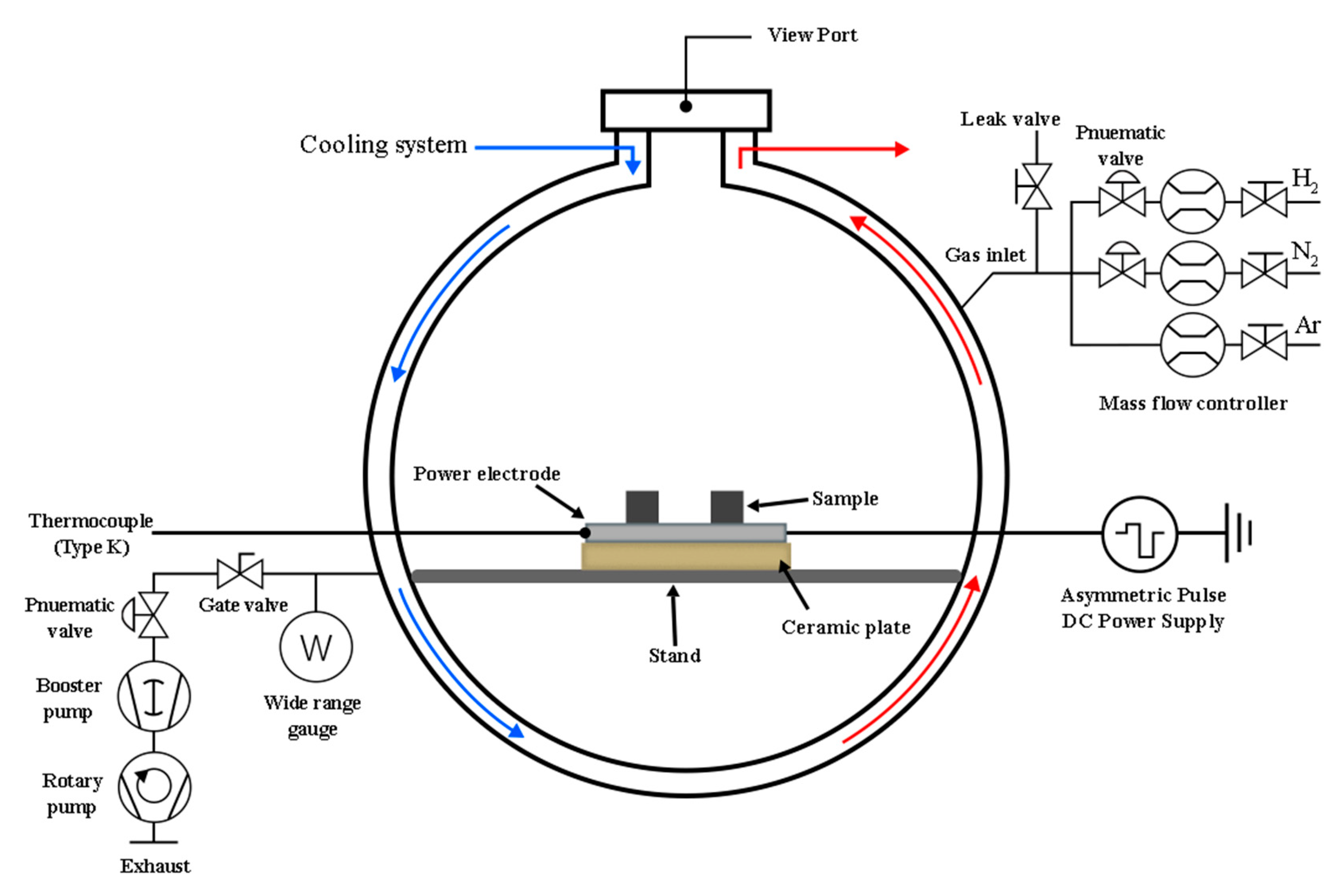

The experiments were conducted in a custom-built plasma nitriding system, depicted schematically in

Figure 1. The system comprised a vacuum chamber, an evacuation system, a cooling system, and a gas supply unit for high-purity argon (Ar, 99.995%), nitrogen (N

2, 99.995%), and hydrogen (H

2, 99.995%). An asymmetric bipolar pulse DC power supply (Advanced Energy Pinnacle® Plus+) operating at a frequency of 50 kHz and a duty cycle of 20% was used to generate and sustain the plasma. The substrate holder functioned as the powered electrode and was instrumented with a thermocouple for in-situ temperature monitoring. The surface treatment was performed in three sequential stages: plasma cleaning, preheating, and plasma nitriding. The initial plasma cleaning stage was conducted for 20 minutes to remove surface impurities and the native oxide layer. This was achieved using a mixture of Ar and H

2 introduced at a flow rate of 500 sccm. Argon plasma promoted the physical removal of contaminants through ion bombardment (sputtering), while hydrogen plasma facilitated the chemical reduction of surface oxides. During this process, the working pressure was maintained at 0.25 Torr, resulting in a negative bias voltage of 625–800 V, a discharge current of 0.5–0.8 A, and a power of approximately 400 W. This concurrently raised the substrate temperature to 200 ± 10 °C in preparation for the next stage.

Following the cleaning stage, the system was prepared for the main treatment. The preheating process was initiated by increasing the operating pressure to approximately 2.0 Torr. This allowed the plasma current to be raised to 1.2 ± 0.1 A, enhancing the ion flux bombarding the substrate. To prevent thermal shock, the substrate temperature was ramped gradually to the final treatment temperature over a period of 20 minutes. The plasma nitriding process was then conducted for 4 hours at a constant temperature of 400 °C using a reactive nitrogen-hydrogen (N

2-H

2) gas mixture. Throughout this stage, the working pressure was maintained at 2.5 Torr. To investigate the effects of hydrogen concentration, the H

2 gas flow rate was systematically varied, with values set at 100, 200, 300, and 400 sccm for different samples. Upon completion of the treatment, the nitrided specimens were cooled to room temperature under vacuum within the chamber. A summary of all key process parameters is presented in

Table 1.

The crystallographic phase composition of the nitrided specimens was analyzed using an X-ray diffractometer (XRD; BRUKER, D8 Advance) with a Cu Kα radiation source (λ = 1.5406 Å). Scans were performed over a 2θ angular range of 10° to 90°, with data collected at a step size of 0.03° and an integration time of 0.2 seconds per step. The thickness of the nitrided layer was examined on cross-sectioned samples using an optical microscope (OM). To correlate the observed microstructure with elemental distribution, nitrogen concentration depth profiles were measured using glow discharge optical emission spectroscopy (GD-OES).

Surface microhardness was measured using a Digital Display Low Load Vickers Hardness Tester (200HVS-5). A standard Vickers diamond indenter was used to apply a load of 0.2 kgf (2 N) for a dwell time of 20 seconds. The final hardness value for each sample was reported as the average of five measurements taken at different locations. The friction and wear behavior was investigated using a ball-on-disk tribometer (CSEM, Japan) under dry sliding conditions. An uncoated 6.00 mm SUS440C stainless steel ball was used as the counter body, sliding against the prepared DC53 disk surfaces. Prior to testing, both surfaces were cleaned with acetone. The experiment was performed with a normal load of 2.00 N at a constant linear speed of 10.00 cm/s along a circular track with a radius of 5.00 mm. The test ran for a total of 10,000 laps, with data recorded at an acquisition rate of 3.0 Hz. All procedures were carried out in ambient air at a controlled temperature of 27.0 °C and a relative humidity of 15.00%. Following the wear tests, the morphology and dimensions of the wear tracks on the nitrided and non-nitrided samples were analyzed using a 3D optical surface scanner (KEYENCE VK-X3000 Series) to determine the wear volume and mechanisms.

3. Results and Discussion

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.1. X-Ray Diffraction

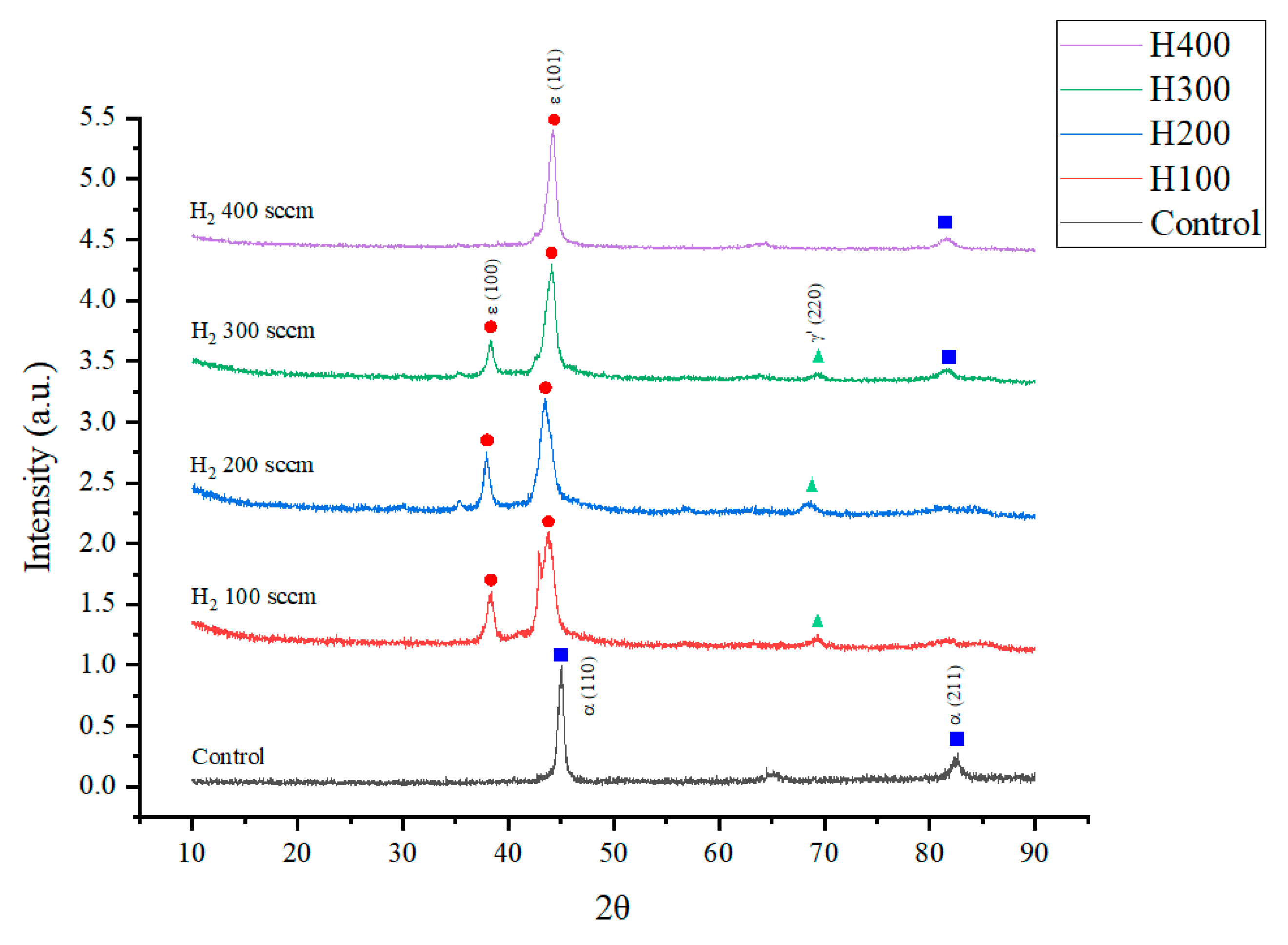

Figure 2 displays the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the DC53 steel samples before and after plasma nitriding at various hydrogen flow rates. As expected, the untreated control sample exhibits diffraction peaks corresponding solely to the body-centered cubic (BCC) α-Fe phase at 2θ angles of 45.2° and 82.6°, which is characteristic of the steel substrate [

10,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Following plasma nitriding, a profound transformation of the surface metallurgy is observed. A key trend emerges where the H

2:N

2 ratio critically governs the resulting phase composition. At lower hydrogen flow rates (H100 and H200), the patterns reveal the formation of a dual-phase compound layer consisting of both epsilon (ε-Fe

2-3N) and gamma-prime (γ’-Fe

4N) iron nitrides. The characteristic peaks for the ε phase were identified at approximately 38.0° and 43.9°, while the γ’ phase was detected near 69.4°. The dramatic reduction in the intensity of the underlying α-Fe peaks across all nitrided samples confirms the successful conversion of the surface into a nitride layer. Most notably, as the hydrogen flow rate increases, the relative intensity of the γ’-Fe

4N phase diminishes. This trend culminates in the H400 sample, where the γ’ phase peaks are completely suppressed. The resulting diffractogram is dominated by a highly intense and sharp peak corresponding to the (101) plane of the ε-Fe

2-3N phase. These results unequivocally demonstrate that the hydrogen flow rate is a powerful control parameter for selectively engineering the phase constituents of the nitrided layer, enabling a transition from a dual-phase (ε + γ’) structure to a predominantly single-phase ε-nitride surface.

3.2. Vicker Microhardness

Figure 3 illustrates the profound effect of hydrogen flow rate on the surface and bulk microhardness of the DC53 tool steel. The untreated control sample serves as a baseline, exhibiting a nominal hardness of 564.5 ± 28 HV

0.2, with no significant variation between the surface and the bulk. Upon plasma nitriding, a substantial increase in surface hardness is achieved. The relationship between hydrogen flow rate and hardness follows a distinct parabolic trend, peaking at an optimal condition. A hydrogen flow rate of 100 sccm yielded a significant hardness of 968.5 ± 17.8 HV

0.2. However, the maximum surface hardness, an impressive 1121.5 ± 69.2 HV

0.2 —nearly double that of the untreated steel—was achieved at a hydrogen flow rate of 200 sccm. This peak in hardness is directly attributed to the formation of a dense, well-developed compound layer rich in the hard ε-Fe

2-3N phase, as was suggested by the XRD analysis.

Beyond this optimum point, increasing the hydrogen flow rate to 300 and 400 sccm resulted in a progressive decrease in surface hardness to 714.4 ± 7.9 HV

0.2 and 663.0 ± 19.4 HV

0.2, respectively. This decline can be explained by two competing mechanisms. While hydrogen is essential for surface activation, an excessive amount can lead to a dilution effect, where a higher concentration of hydrogen in the plasma increases the probability of N + H recombination in the gas phase [

22,

23]. This reduces the flux of active nitrogen species available for diffusion into the steel surface, resulting in a thinner or less dense nitride layer and, consequently, lower hardness. These findings confirm that precise control over the hydrogen content is critical to maximizing the strengthening effect of the plasma nitriding process.

3.3. OM Image and GD-OES

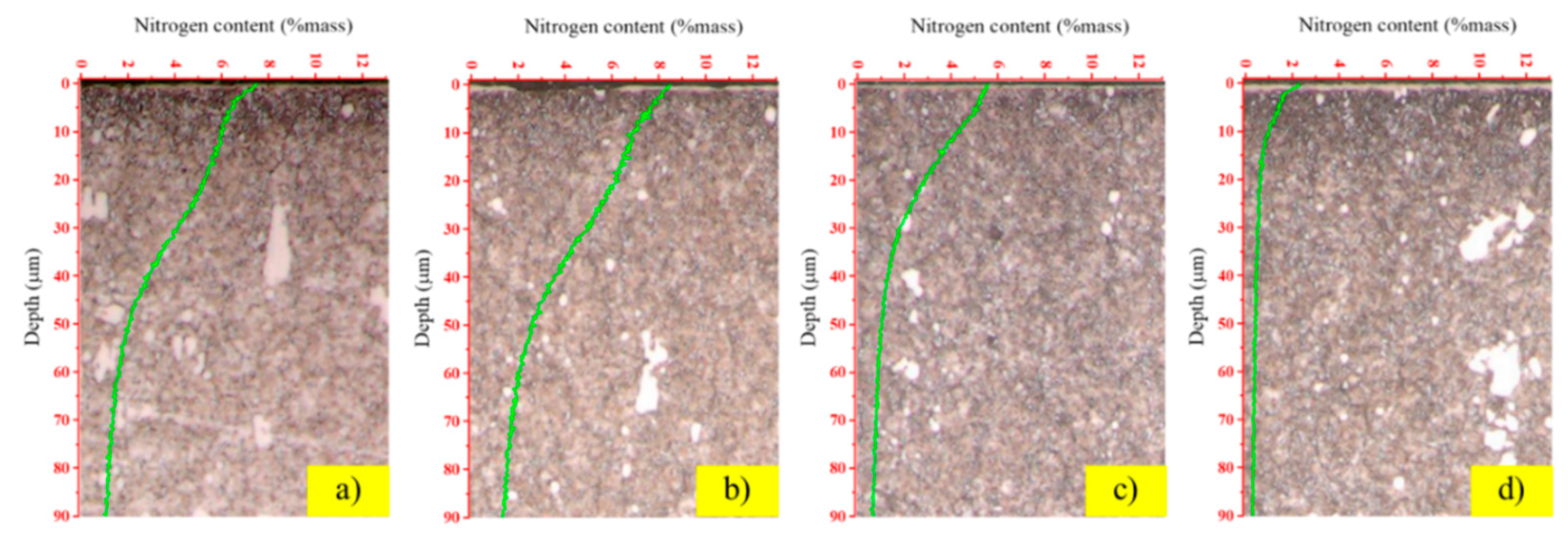

To quantify the depth and concentration of nitrogen penetration, the nitrided layers were analyzed using GD-OES, with the results presented in

Figure 4. The depth profiles clearly show that the hydrogen flow rate is a determining factor in the efficiency of nitrogen diffusion. The optimal case was observed at a hydrogen flow rate of 200 sccm (

Figure 4b), which yielded the most desirable profile: a high surface nitrogen concentration of approximately 8% mass and the deepest effective case depth, with nitrogen penetrating well beyond 90 µm. This rich and deep nitrogen profile provides a direct explanation for the peak surface hardness observed in the same sample. Conversely, increasing the hydrogen flow rate to 400 sccm (

Figure 4d) proved to be counterproductive. This condition resulted in the lowest nitrogen diffusion, with a shallow penetration depth of less than 10 µm and a surface concentration of only 2% mass. These results highlight the dual role of hydrogen in the plasma nitriding process. At an optimal concentration, hydrogen ions are beneficial, effectively removing the native oxide layer from the steel surface and opening pathways for nitrogen diffusion. However, an excessive hydrogen concentration leads to a detrimental side-reaction in the plasma. The increased availability of hydrogen atoms promotes the formation of ammonia (NH

3) through chemical reactions with active nitrogen species [

24,

25]. This newly formed ammonia gas is subsequently removed from the vacuum chamber by the pumping system, effectively depleting the plasma of the atomic nitrogen required for the nitriding process. Therefore, precise control of the hydrogen ratio is essential to prevent this parasitic reaction and ensure maximum nitrogen diffusion into the substrate.

3.4. Wear Test

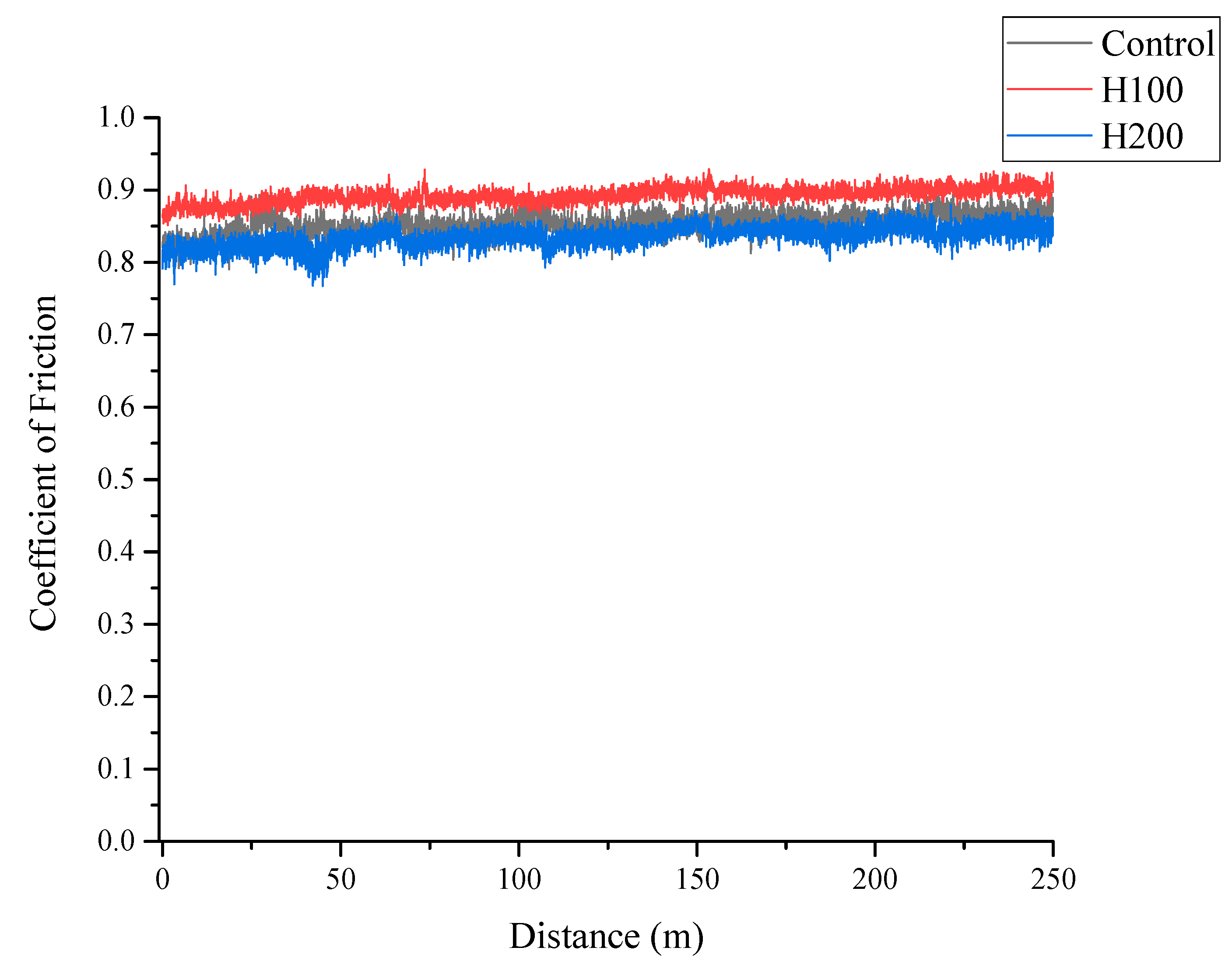

The tribological performance of the nitrided surfaces was evaluated to determine their resistance to friction and wear.

Figure 5 presents the evolution of the coefficient of friction (CoF) as a function of sliding distance for the control, H100, and H200 samples. All specimens exhibited a short initial running-in period, after which the CoF stabilized for the remainder of the test. The control and H100 samples displayed very similar frictional behavior, with a steady-state CoF averaging around 0.88. Notably, the H200 sample, which previously demonstrated the highest surface hardness and optimal nitrogen diffusion, exhibited a consistently lower and more stable CoF, averaging approximately 0.82. While the overall reduction in friction is modest, this enhanced stability is significant. It suggests that the superior mechanical properties of the H200 surface promote the formation of a more consistent and robust tribo-layer during sliding contact, a key indicator of improved wear resistance.

To quantify the extent of wear damage, the wear tracks were analyzed using 3D optical profilometry, as shown in

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8. The untreated control sample (

Figure 6) exhibited signs of severe wear. The wear track is wide (525.84 µm) and deep (0.78 µm), with a substantial cross-sectional wear area of 163.14 µm

2. Notably, the edges of the track show significant material pile-up, rising about 0.6 µm above the original surface. This feature is clear evidence of extensive plastic deformation, indicating that the dominant wear mechanisms are severe adhesion and abrasion, which are characteristic of a softer metallic surface. In contrast, the protective effect of the nitrided layer is immediately apparent. The sample treated with 100 sccm of hydrogen (

Figure 7) shows a marked improvement in wear resistance. The wear track is narrower and shallower, resulting in a cross-sectional wear area of 99.77 µm

2—a 39% reduction compared to the control. The most outstanding performance was achieved by the sample nitrided with 200 sccm of hydrogen (

Figure 8). The wear damage is minimal, with an exceptionally shallow track depth of only 0.09 µm and a cross-sectional wear area of just 13.13 µm

2. This represents a remarkable 92% reduction in material loss compared to the untreated steel. The absence of significant plastic deformation or material pile-up indicates a fundamental shift in the wear mechanism to one of very mild abrasive or polishing wear. These results unequivocally demonstrate that the optimized plasma nitriding process transforms the tribological behavior of DC53 steel. The superior wear resistance of the H200 sample is a direct consequence of its exceptionally high surface hardness and the robust, dense compound layer formed during the treatment, which effectively resists mechanical degradation under sliding contact.

4. Conclusions

This study successfully investigated and demonstrated the critical influence of the hydrogen flow rate on the microstructure, hardness, and tribological properties of DC53 tool steel during the plasma nitriding process. The key findings can be summarized as follows. The hydrogen-to-nitrogen ratio is a decisive parameter in controlling the phase composition of the nitride layer. An optimal hydrogen flow rate of 200 sccm was found to be most effective in promoting the formation of a dense, uniform compound layer rich in the hard ε-Fe2-3N phase. Conversely, excessive hydrogen (400 sccm) was detrimental, hindering nitrogen diffusion likely due to the parasitic formation of ammonia in the plasma. Consequently, the surface microhardness was significantly enhanced. The optimal condition of 200 sccm H2 yielded a peak surface hardness of 1121.5 HV0.2, which is approximately double that of the untreated DC53 steel. This peak in hardness directly correlates with the formation of the superior nitride layer observed in the microstructural analysis. The tribological performance of the steel was dramatically improved. The optimized nitrided layer on the H200 sample exhibited outstanding wear resistance, resulting in a remarkable 92% reduction in wear area compared to the untreated control sample. This improvement is attributed to the high surface hardness and the fundamental shift in the wear mechanism from severe adhesive and abrasive wear to a much milder polishing mechanism. In conclusion, this work establishes a clear processing-structure-property relationship, confirming that the precise control of hydrogen content is a key strategy for engineering superior, high-performance surfaces on DC53 tool steel via plasma nitriding.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially funded by Mahasarakham University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

-.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CoF |

Coefficient of friction |

| OM |

Optical image |

| GD-OES |

Glow discharge optical emission spectroscopy |

References

- Theisen, W.; Vollertsen, F. Tool steels for forging and die casting. In Metal Forming: Technology and Process Modeling; Chen, J.L., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 145–172. [Google Scholar]

- Habibollah, T.; Moslemi, N. A review on properties, production, and applications of tool steels. Int. J. Mod. Eng. Res. 2015, 5, 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Krauss, G. Steels: Processing, Structure, and Performance; ASM International: Materials Park, OH, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Marini, G.; et al. Failure analysis of two cold-working cutting tools. Case studies. Ann. ’Dunarea de Jos’ Univ. Galati, Fascicle V, Technol. Mach. Build. 2017, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Vollertsen, F. Tool wear and life span variations in cold forming operations and their implications in microforming. In Proceedings of the Advances in Abrasive Technology V; 2012; pp. 551–558. [Google Scholar]

- Mittemeijer, E.J.; Somers, M.A.J. Thermodynamics and kinetics of plasma nitriding. Mater. Sci. Forum 1997, 245–246, 127–140. [Google Scholar]

- Suresh Gyan Vihar University. QPQ salt bath nitriding and its effect on steels: Review. J. Adv. Res. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023.

- Saha, S.K.; Datta, S.K. Effect of gas composition on plasma nitriding of AISI H13 hot work tool steel using a pulsed DC glow discharge. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2012, 206, 4165–4171. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, D.C. Erosion and wear behavior of nitrocarburized DC53 tool steel. Wear 2010, 268, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuer, C.J.; Zanetti, F.I.; Cardoso, R.P.; Brunatto, S.F. Influence of process temperature on phase formation in plasma nitrided AISI 420 steel. Mater. Sci. Forum 2016, 869, 816–821. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.J.; et al. Effect of DC plasma nitriding temperature on microstructure and dry-sliding wear properties of 316L stainless steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2008, 202, 2749–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizawa, T.; Kuwahara, H. Plasma nitriding as an environmentally benign surface structuring process. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2003, 174–175, 700–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, C.P.; Aghajani, H. Plasma Nitriding of Steels; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Donkó, Z.; Zajičková, L.; Sugimoto, S.; Harumningtyas, A.A.; Hamaguchi, S. Modeling characterisation of a bipolar pulsed discharge. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2020, 29, 105001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewnisai, S.; Chingsungnoen, A. Surface hardening of SKD61 steel using low-temperature plasma nitriding. J. Appl. Sci. (Thailand) 2021, 20, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Zhao, P.; Hu, R. Influence of bipolar-pulsed plasma nitriding on microstructure and properties of high-speed steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2018, 227, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Cullity, B.D.; Stock, S.R. Elements of X-Ray Diffraction, 3rd ed.; Pearson Education Limited: Harlow, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Waseda, Y.; Matsubara, E.; Shinoda, K. X-Ray Diffraction Crystallography: Introduction, Examples and Solved Problems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, P.F.; Li, H.B.; Lin, J.B. Microstructure and properties of DC53 tool steel after plasma nitriding. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2010, 527, 3209–3214. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, D.C. Influence of layer microstructure on the corrosion behavior of plasma nitrided cold work tool steel. J. Mater. Sci. 2010, 45, 1540–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duh, J.G.; Wu, J.K.; Chen, C.Y. Effects of nitriding temperature on the properties of plasma nitrided DC53 tool steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2008, 202, 2969–2975. [Google Scholar]

- Alim, A.D.M. Microstructural characterization and mechanical properties of plasma nitrided DC53 tool steel. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2011, 20, 835–842. [Google Scholar]

- Maliska, S.; et al. Effect of the gas mixture and nitriding temperature on the properties of plasma nitrided AISI 316L stainless steel. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2012, 34, 317–325. [Google Scholar]

- Dalke, L.S.; et al. Influence of hydrogen content on the plasma nitriding of AISI 4140 steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 718, 191–200. [Google Scholar]

- Ricard, A.; et al. Role of hydrogen in the nitriding process of steels. Vacuum 1998, 50, 267–270. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).