1. Introduction

The Jabal Sayid-Mahd Adhab region is important mining sites that serve as sources of rare metals and radioactive elements [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. The geological structure of this region reflects the broad composition of the Arabian Shield (AS), which is made up of igneous and metamorphic rocks that originated from ancient sedimentary and volcanic formations dating back to the Precambrian era. Since their formation, these rocks have undergone significant geological changes and formative processes, including uplift, subsidence, folding, large fractures, volcanic activity, and the intrusion of molten magma under extreme pressure and temperature. These processes have transformed these rocks, altered their chemical composition and changed many of their original properties.

Felsic igneous rocks, such as granite, rhyolite, and pegmatite, are important sources of uranium. The oxidation of U(IV) to U(VI) is crucial for leaching, as U(VI) compounds are more soluble [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Uranium solubility allows its migration from these rocks and reprecipitation in nearby fracture planes and cavities [

17,

18]. The mobility of uranium is associated with the fractionation of its isotopes, particularly

238U and

234U, leading to a notable excess of

234U in hydrospheric environments [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. In closed systems older than one million years, a state of uranium-series equilibrium occurs, where the activities of daughter and parent nuclei are equal. However, uranium-series disequilibrium can arise when daughter isotopes are more mobile than their parents due mostly to alpha-recoil and influenced by processes like water-rock interactions, with meteoric and groundwaters playing a significant role. Additionally, factors like rock age, type, and climate also affect uranium isotope ratios [

25], making these insights valuable for geological tracing and understanding geochemical processes.

Groundwater and surface waters show varying activity ratios between daughter and parent nuclides (

234U/

238U), generally displaying enrichment in the daughter

234U. Ref. [

26] compiled results from studies on uranium isotopes across different types of groundwaters. They found that in most instances, the activity ratio (AR) (

234U/

238U) exceeded 1.0, with some areas exhibiting ratios greater than 10 in groundwater. Conversely, ratios less than 1 have been observed, though they are less common. Less than unity activity ratios is a significant indicator of uranium accumulation from groundwater. These ratios can help identify the water type and its mixing degree. Rocks generally have low

234U activity, while various water sources show higher levels, with an average global

234U/

238U ratio around 1.15 [

27].

No previous studies have been conducted in the selected regions concerning the uranium isotopic composition of groundwater, so this research is considered the first contribution in this regard. Examining the activity ratio in groundwater can offer important insights into redox conditions and the sources of uranium, so the main goal of this study is to assess uranium concentration and the 234U/238U activity ratio in several wells within the study area and utilize this data to gain insights into the characteristics of groundwater.

The results will be helpful in: 1) investigating the differences of 234U/238U ratios in groundwater samples from the Jabal Sayid-Mahd Adhab area; 2) utilizing the data to gain insights into groundwater characteristics; 3) assessing the safety and suitability of groundwater for drinking and irrigation, and detect any natural radioactive pollution; and provide a basis for further research on groundwater quality and assist local authorities in making informed water management decisions.

2. Geology of the Study Area

The Jabal Sayid-Mahd Adhab area is situated in the western region of Saudi Arabia (

Figure 1a) and is part of the larger geological framework of the AS (

Figure 1b). It is a part of the Jeddah and Hijaz terranes and lies close to the Bir Umq suture zone. This suture zone serves as a boundary between two distinct terranes: the Hijaz and Jeddah terranes. The Jeddah terrane is positioned in the western region of the AS, bordered by several tectonic units: the Hijaz terrane to the north, the Afif terrane to the east, the Asir terrane to the south, and the Red Sea coastal plain to the west. The oldest rock unit in the study area is the Sumayir Formation (831±47 Ma, [

28]). This formation consists of basalt, chert, tuffite, and siltstone, as well as minor mafic-ultramafic intrusive rocks, and it is locally interbedded with serpentinite. These stratified rocks have experienced regional metamorphism due to significant geological events, including various mountain-building tectonic movements, uplift and subsidence, extensive faulting, folding, volcanic activity, and plutonic intrusion at very high pressure and temperature. These processes caused deformation, altered their chemical composition, changed their original properties, and transformed most into greenschist facies.

The Dhukhr tonalitic complex, with a crystallization age of 811±4 Ma [

29], intruded into the Sumayir Formation. These rocks have a geological connection to the Mahd Group and the Ghamr Group, separated by an unconformity surface. The Mahd Group rocks are the most extensive in the study area and comprise sedimentary and volcanic metamorphic formations, featuring alternating basaltic and andesitic lavas along with sedimentary rocks such as chert, limestone, sandstone, and conglomerates. They are considered economically significant due to the presence of large volcanic sulfide deposits at Jabal Sayid. Additionally, the injected tonalites of Hufayriyah and the Ram Ram complex are interbedded within the Mahd rocks. The ages of the Mahd rocks range from 775 to 785 million years [

29]. The Ram Ram complex consists of small rock masses, including red granite, granodiorite, diorite, and gabbro. These rocks intrude into the Mahd Group and are dated to be between 750 and 770 million years old [

29]. The Hufayriyah complex features minor tonalitic outcrops that penetrate the Mahd Group. These tonalitic rocks are subsequently overlain by low-grade volcanic and sedimentary formations of the Ghamr Group.

Rocks of the Ghamr Group are prevalent in the central and southern parts of the study area (

Figure 1b). This group is composed of volcanic and sedimentary rocks with low metamorphism, unconformably deposited on the Hufayriyah Tonalite. Their ages are estimated at 748 ± 22 million years [

30]. The group includes conglomerates with volcanic clasts from the Mahd Group and granitic clasts from the Ram Ram Complex, as well as sandstone, rhyolite, dacite, volcanic breccia, and minor occurrences of basalt and andesite. The rocks of the Furayh Group are widely distributed throughout the study area, comprising mafic and felsic volcanic rocks alongside sedimentary rocks, including mudstone, siltstone, sandstone, greywacke, and, to a lesser extent, limestone and conglomerates, all exhibiting a low degree of metamorphism.

The Hadb ash Sharar suite comprises semi-circular bodies of undeformed granite, granodiorite, and gabbro, which are interbedded within the Mahd, Ghamr, and Hufayriyah groups. These rocks are dated at 584 ± 26 million years using the rubidium-strontium dating method [

30]. The igneous bodies of the Hadb ash Sharar suite include monzogranites, alkali-feldspar granites, alkali-rich granites, and smaller bodies of granodiorite and gabbro. The pegmatites found in the Jabal Sayid area are part of the Hadb ash Sharar suite rocks, noted for their high radioactivity and richness in titanium, tin, uranium, and rare earth elements. The latest volcanic activities in the study area are represented by the basaltic and andesitic rocks of Harrat Rahat, which date back to the Tertiary and Quaternary periods. Recent sediments consist of detrital materials from ancient igneous and metamorphic rocks, primarily including sandstone and clayey substances deposited in valleys and low-lying areas.

3. Uranyl Mineralization

The study area features late alkaline to per-alkaline granites that intersect with the volcanic and volcano-sedimentary rocks of the Mahd Group, alongside various outcrops of granodiorite and quartz-diorite. It is notable for several mineral-rich regions, including the gold and copper deposits at the Mahd adh Dhahab prospect, as well as uranium, copper, and REE deposits in the Jabal Sayid area. The Al-Dahayeen Plateau, which is located to the south of Jabal Sayid is also rich in uranium and REEs. These regions contribute significantly to groundwater uranium contents and its isotopic composition.

The Jabal Sayid outcrop features pegmatites located in the northern section of an alkaline granite block. These granites are classified as unique AS granites and are part of the Hadb ash Sharar pluton. This pluton includes a core of pink granites surrounded by a broad band of hornblende, biotite, and granodiorite-rich monzogranites.

Ref. [

31] identified the primary mineralogy of these pegmatites as quartz and microcline, with varying amounts of aegirine, arfvedsonite, plagioclase, and hematite. Additionally, [

4] reported several ore minerals in the aplite-pegmatite rocks of Jabal Sayid, such as synchysite, bastnaesite, pyrochlore, zircon, thorite, monazite, fluorite, sphalerite, and sphene. Fluorite is the most abundant mineral, primarily found in weathering zones. Yellow uranyl mineralization is also present as gap fillers and crusts in the quartz veins and along the fractures of the host rock. Additionally, minerals such as galena, malachite, sphalerite and calcite are observed. The research conducted by [

5] identified kasolite, a Pb-U silicate mineral, commonly found alongside iron oxides, malachite, calcite, and galena. To the south of Jabal Sayid, the alkaline Hadb Ash Sharar granite has reserves of 23 million tons containing 0.13% Nb, 0.13% Ce, over 1.7% Zr, and 134 ppm U [

32].

Ref. [

9] conducted in situ gamma-ray spectrometry measurements in the aplite-pegmatite of Jabal Sayid, identifying radioactive zones with a maximum eU content of 1550 ppm and eTh of 7974 ppm. In comparison, alkali granite has average eU and eTh levels of 12 ppm and 34 ppm, while felsite shows similar values at 11 ppm for eU and 32 ppm for eTh. Pegmatite veins intersecting alkali granite exhibit higher averages of 34 ppm for eU and 101 ppm for eTh. The metamorphosed volcanic rocks of the Mahd Group display the lowest radioactivity, with average eU at 0.8 ppm and eTh at 1.6 ppm, and show signs of post-magmatic alterations like silicification and oxidation. Excluding the metavolcanics, a strong positive correlation between eU and eTh across various rock types suggests geochemical coherence during magma crystallization, indicating these elements are mainly incorporated into accessory minerals and unaffected by alteration processes.

Granitic rocks, which have high eU and eTh, do not show elevated values for eU/eTh ratio (less than 1). In contrast, the volcanic metamorphic rocks of the Mahd Group exhibit the highest values for eU/eTh ratio, reaching up to 7. Ref. [

5] proposed that hydrothermal solutions related to granitic magma played a key role in the formation of uranyl minerals in the Jabal Sayid region. Some limited redistribution of uranium may have occurred, as suggested by the presence of heterogeneous processes such as kaolinitization and oxidation. Conversely, the high thorium content in the granitic rocks indicates syngenetic formation, with the most differentiated pegmatites exhibiting the highest values of eU and eU/eTh. The formation of kasolite was significantly influenced by fluoride complexes. High-temperature hydrothermal solutions reacted with existing uranium-bearing metamict accessory minerals, such as zircon, uranium-rich thorite and pyrochlore, resulting in the development of uranous fluoride complexes [

5].

4. Materials and Methods

Nineteen groundwater samples were collected and analyzed to assess their major anions and uranium isotopic composition. The investigated wells, with depths ranging from 10 to 34 meters, are classified as shallow groundwater wells tapping unconfined aquifers.

Figure 2 displays a map of the valleys in the Sayid and Mahd Adh Dhahab area, highlighting the locations of the chosen wells. The samples were selected from wells near uranium mineralizations in this region to investigate the transport of uranium and its possible precipitation from groundwater.

4.1. Anions Analyses

In order to investigate the possible uranium speciation in groundwater, various laboratory techniques and instruments were used to measure the anion concentrations and physicochemical parameters in the water samples. pH was measured by Mettler DL25 and the TDS/conductivity by Mettler Toledo. Silicate, nitrate and phosphate were measured by spectrophotometry; bicarbonate and sulfates by potentiometry; chloride by DPD colorimetry and fluoride by fluoride ion-selective electrode (ISE).

4.2. Alpha Spectrometry Technique

The determination of uranium isotopes (238U and 234U) was carried out using alpha spectrometry, following their chemical separation via ion exchange. 0.03 Bq of 232U were added as a tracer to 200 mL of water samples. The samples were left for three days to reach isotopic equilibrium. Uranium was first isolated from water samples using AG 1-8X anion-exchange resin in 9 M HCl, then precipitated as uranium fluoride on a 0.1 µm plastic membrane. The prepared sources were analyzed using an ORTEC Octete Plus alpha spectrometer equipped with eight high-resolution silicon detectors (efficiency 20–21.5%). Detector calibration and quality assurance were verified using IAEA reference materials. The obtained spectra allowed accurate quantification of uranium concentration and isotopic ratios with a detection limit below 0.01 BqL⁻¹.

5. Results and Discussions

5.1. Physicochemical Parameters and Anion Concentrations of the Groundwater

The measured physicochemical parameters of the groundwater samples provide important indications about the hydrogeochemical environment, water quality, and processes influencing groundwater composition. The pH values vary from 7.14 to 8.43, with an average of 7.9, indicating that the groundwater is neutral to slightly alkaline. This alkalinity implies carbonate buffering, likely resulting from the dissolution of carbonate minerals like calcite or dolomite. The near-neutral pH also favors the stability of bicarbonate ions in groundwater. The temperature of the samples varies between 23.7°C and 31.2°C, with average of 28.9°C, reflecting ambient environmental conditions typical of shallow aquifers in semi-arid to arid regions. Slight variations in temperature among samples may indicate differences in depth, recharge timing, or local geothermal gradients.

The total dissolved solids (TDS) values show a wide range (447–22,400 ppm; average 7,141 ppm), indicating significant spatial variability in salinity. According to standard water quality classifications, most samples fall into the brackish to saline category. The elevated TDS values suggest intense evaporation, dissolution of evaporitic minerals, and/or mixing with saline water sources. The electrical conductivity (EC) varies from 691 to 34,700 µS/cm (average 11,026 µS/cm), showing a strong positive correlation with TDS, as both parameters reflect the ionic concentration of dissolved constituents. High EC values confirm salinity enrichment, possibly caused by evaporative concentration and mineral dissolution. Generally, the physicochemical characteristics suggest that the groundwater is moderately to highly saline, controlled by water–rock interactions, evaporative processes, and anthropogenic inputs, with limited buffering capacity in some locations.

The variations in anion concentrations help distinguish between natural geochemical evolution and human-induced contamination, as well as infer the hydrological connectivity and recharge characteristics of the shallow groundwater system. The chemical composition of the groundwater shows significant variations in anion concentrations, reflecting natural geochemical processes in this arid region (

Table 1). The chloride concentration (63–9051 ppm; avg. 2230 ppm) indicates considerable spatial variability. Such elevated values, especially those exceeding 1000 ppm, suggest strong effects of evaporation and contamination from domestic sources. The bicarbonate levels (85–844 ppm; avg. 300 ppm) are moderate, implying that carbonate mineral dissolution and CO₂ from soil respiration are important contributors to groundwater chemistry. This also suggests an active recharge from areas where infiltration interacts with carbonate-rich sediments. The nitrate content (23–422 ppm; avg. 139 ppm) is well above the natural background level (typically <10 ppm), pointing to a clear anthropogenic impact and surface contamination due to the shallow depth of the aquifer. The sulfate concentration (51–18,375 ppm; avg. 2918 ppm) dominates the anionic composition, which may be attributed to oxidation of sulfide minerals which occur in the nearby Precambrian rocks and mining areas, dissolution of gypsum or anhydrite and industrial inputs. Extremely high sulfate values could also indicate evaporative concentration in arid and semi-arid conditions. The fluoride concentration (0.24–4.02 ppm; avg. 2.13 ppm) exceeds the recommended limit for drinking water (1.5 ppm) in several samples, suggesting fluoride-bearing mineral dissolution (e.g., fluorite, biotite) or evaporation effects enhancing ion accumulation. The silicate concentration (11.48–43.97 ppm; avg. 29.3 ppm) reflects silicate mineral weathering (such as feldspars and clays), contributing to the overall ionic balance but remaining within normal ranges for groundwater interacting with silicate formations. As expected in such an arid area, the low or undetectable phosphate, ammonium, and nitrite concentrations in most samples indicate limited organic or nutrient pollution, except at a few localized sites (

Table 1).

5.2. Uranium Behavior and Speciation in Groundwater

The examined wells, which have depths between 10 and 34 meters, access the upper unconfined aquifer. This aquifer is directly affected by surface processes like rainfall infiltration, evapotranspiration, and potential human activities. Groundwater at this depth reflects recent recharge and is more sensitive to variations in physicochemical conditions compared to deeper confined aquifers. In such shallow groundwater systems, uranium behavior is strongly affected by near-surface geochemical interactions. The observed correlations indicate that uranium behavior in this groundwater system is mainly controlled by the degree of groundwater salinity and the prevailing geochemical conditions rather than by temperature or pH alone. The weak negative relationship between uranium and pH (r = - 0.3) suggests limited influence of alkalinity within the studied range (7.14 – 8.43) possibly due to limited adsorption or precipitation of uranyl species, while the very low correlation with temperature (r = 0.19) confirms that temperature variations have a little effect on uranium solubility. In contrast, the moderate positive correlations with EC and TDS (r = 0.48) imply that uranium enrichment is associated with higher ionic strength waters (

Figure 3).

The geochemical data reveal significant correlations between uranium and certain anions, indicating main geochemical controls on uranium mobility and speciation in the studied groundwater. The area is characterized by an arid climate and the presence of nearby uranium and sulfide-bearing rocks, which together influence groundwater chemistry. In neutral to alkaline and oxidizing conditions, common in arid and semi-arid terrains, uranium mobility is strongly influenced by complexation with carbonate, fluoride, and other oxyanions. The strong positive correlation between uranium content and fluoride (r = 0.72), as well as between

238U and

234U activities with fluoride (r = 0.71 and 0.72, respectively), suggests that fluoride complexation plays a dominant role in uranium mobilization and stability in solution (

Figure 4).

In alkaline to slightly alkaline groundwater, typical of arid regions, uranium predominantly occurs as uranyl–fluoride complexes (e.g., [UO₂F₃]⁻, [UO₂F₂]⁰), which are relatively soluble and stable under oxidizing conditions [

33]. This implies that the high fluoride content enhances uranium solubility and transport in the groundwater system. Recent field and experimental studies support the idea that fluoride plays a critical role in uranium mobilization in groundwater, especially in arid to semi-arid areas. For example, [

34] demonstrated in the southern Punjab alluvial aquifers that competitive ion exchange between sediments and groundwater can co-mobilize fluoride and uranium, with the process being influenced by ionic strength and bicarbonate dynamics. This finding reinforces the observed strong correlation between uranium concentration and fluoride, suggesting that uranyl-fluoride complexes significantly enhance uranium solubility and transport in oxidizing, fluoride-rich settings. In such environments, fluoride is one of the key ligands that covaries with uranium, particularly in settings with high total dissolved solids and evaporation [

35]. According to [

5], fluoride speciation was proposed as one of the primary forms influencing the migration of uranium and REE in the Jabal Sayid area, based on the pH of the fluids.

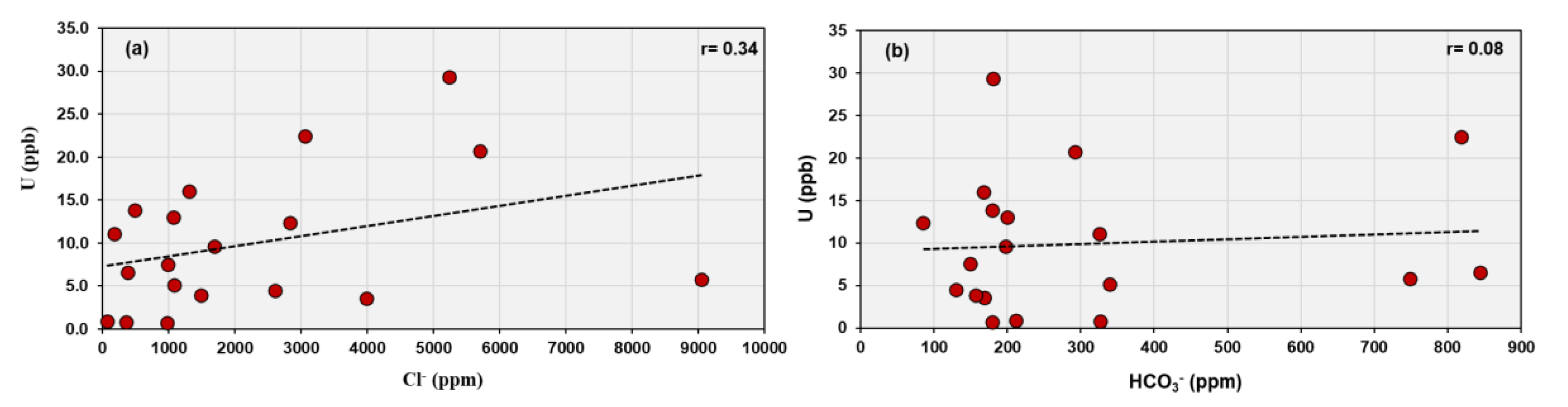

Weak correlations with chloride (r = 0.34) and bicarbonate (r = 0.08) suggest a minor role of chloride or carbonate complexation (

Figure 5). Although bicarbonate commonly forms soluble uranyl–carbonate complexes (e.g., [UO₂(CO₃)₂]²⁻, [UO₂(CO₃)₃]⁴⁻), the low correlation implies that carbonate activity is limited. Ref. [

35] noted that under oxidizing, alkaline conditions, uranyl–carbonate complexes are typically important to uranium mobility. They also pointed out that uranium often covaries with fluoride and other oxyanions under these conditions, implying that the speciation and transport of uranium depend on the relative abundance of competing ligands such as carbonate, fluoride, and sulfate. They emphasized that pH, redox state, and solute chemistry are essential controls on uranium distribution and speciation.

The hypothesis of competitive ion exchange driving co-mobilization of fluoride and uranium is supported by [

34]. They found that fluoride and uranium become exchangeable in sediments, and that increases in ionic strength, as well as variations in bicarbonate, influence their mobilization into groundwater. This study provides field evidence that fluoride plays a significant role in controlling uranium mobility in certain sedimentary systems. In shallow aquifers in arid and semi-arid conditions, it is suggested that carbonate and fluoride processes interact, and that fluoride release (and thus speciation) can be enhanced when carbonate minerals precipitate [

36].

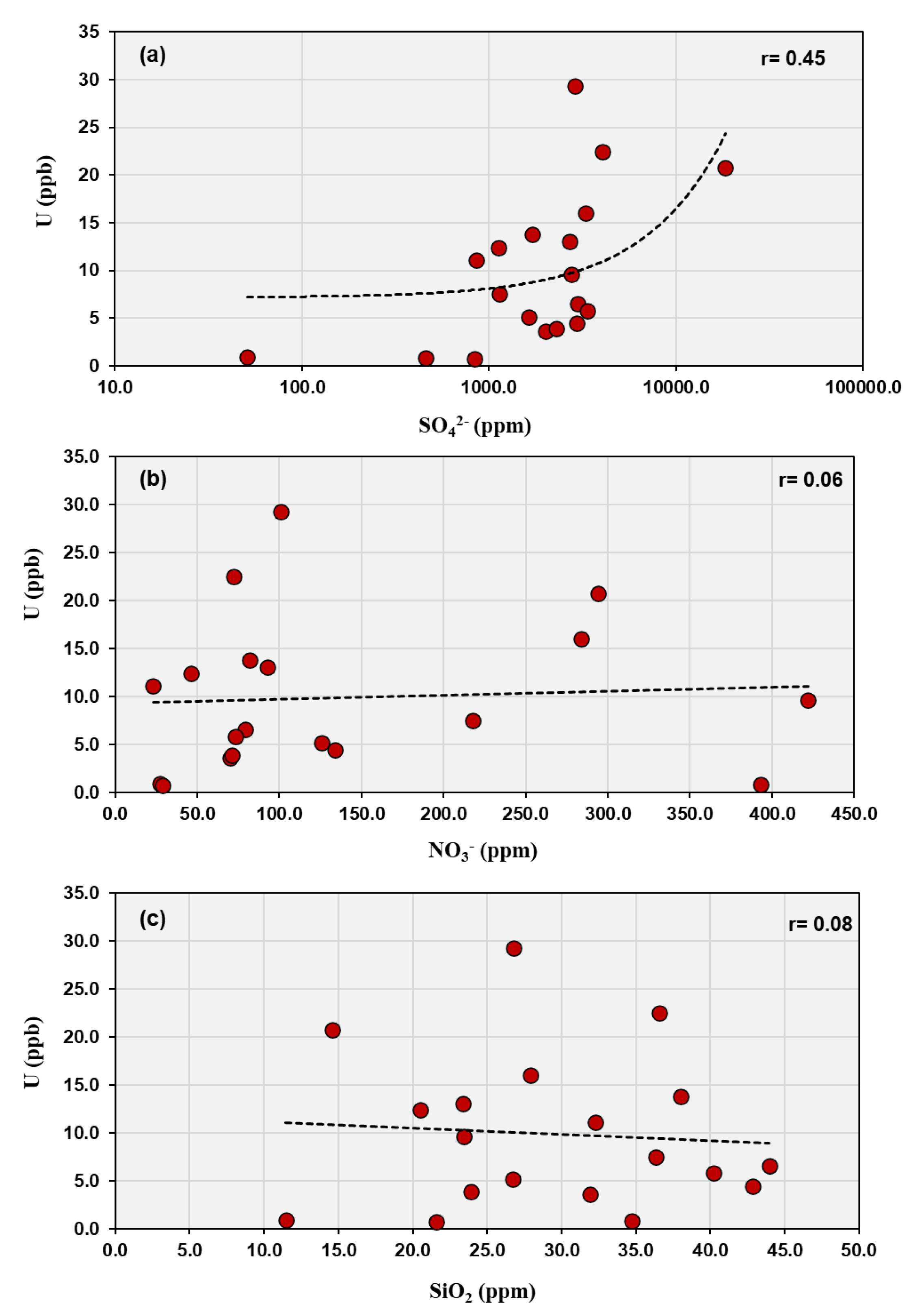

Moderate correlations between uranium and sulfate (r = 0.45) and between uranium and total dissolved solids (r = 0.48) indicate that evaporitic conditions and sulfate mineral dissolution (possibly from gypsum or oxidation of sulfide minerals) also contribute to uranium mobility (

Figure 6a). Ref. [

35] noted that areas with high sulfate concentration tend to maintain oxidizing groundwater conditions, which favor uranium in its hexavalent form (U(VI)). Uranium in oxidized form is more likely to remain soluble, and in the presence of high sulfate, the redox environment is less likely to reduce U to the less soluble U(IV). This is consistent with the moderate correlation observed between uranium and sulfate, indicating that sulfate is not only a marker of geochemical environment but an indirect factor enhancing uranium mobilization. The very low or negative correlations with nitrate (r = 0.06) and silicate (r = –0.08) indicate that these species have little influence on uranium behavior, reflecting their minor abundances and weak complexation tendencies with uranium (

Figure 6b,c). The overall geochemical pattern, where SO₄²⁻ > Cl⁻ > HCO₃⁻ > NO₃⁻ > SiO₃²⁻ > F⁻, characterizes a sulfate–chloride water type typical of arid-zone groundwater affected by evaporitic and surface contamination processes. In such an environment, uranium speciation is primarily governed by oxidizing conditions and complexation with fluoride and sulfate ions, with limited buffering by carbonate equilibria.

5.3. Uranium Isotopic Composition of Groundwater

The

234U/

238U activity ratio is a valuable tool for interpreting groundwater flow and the potential mixing of groundwater from different aquifers [

20,

37]. While

238U can be dissolved from rocks through chemical processes like oxidation and dissolution,

234U can be dissolved via both chemical and physical processes. These include the physical effects of alpha particle emissions and radiation damage in the mineral crystal structure.

The relationship between the activity ratio and uranium concentration in groundwater provides valuable insights into the geochemical processes controlling uranium mobility and sources. Typically, uranium in groundwater exists primarily as the isotopes 238U and 234U, and their activity ratio (234U/238U) often deviates from unity due to alpha recoil and preferential leaching. Low uranium concentrations accompanied by high activity ratios usually indicate prolonged water-rock interaction or leaching from old aquifer materials, where recoil processes enhance daughter enrichment. Conversely, high uranium concentrations associated with low activity ratios indicate recent uranium input. Understanding these ratios is crucial for assessing uranium mobility in groundwater systems, which has implications for water quality, environmental monitoring, and the management of uranium resources.

The activity of

238U and

234U in the studied groundwater samples vary significantly among the wells (

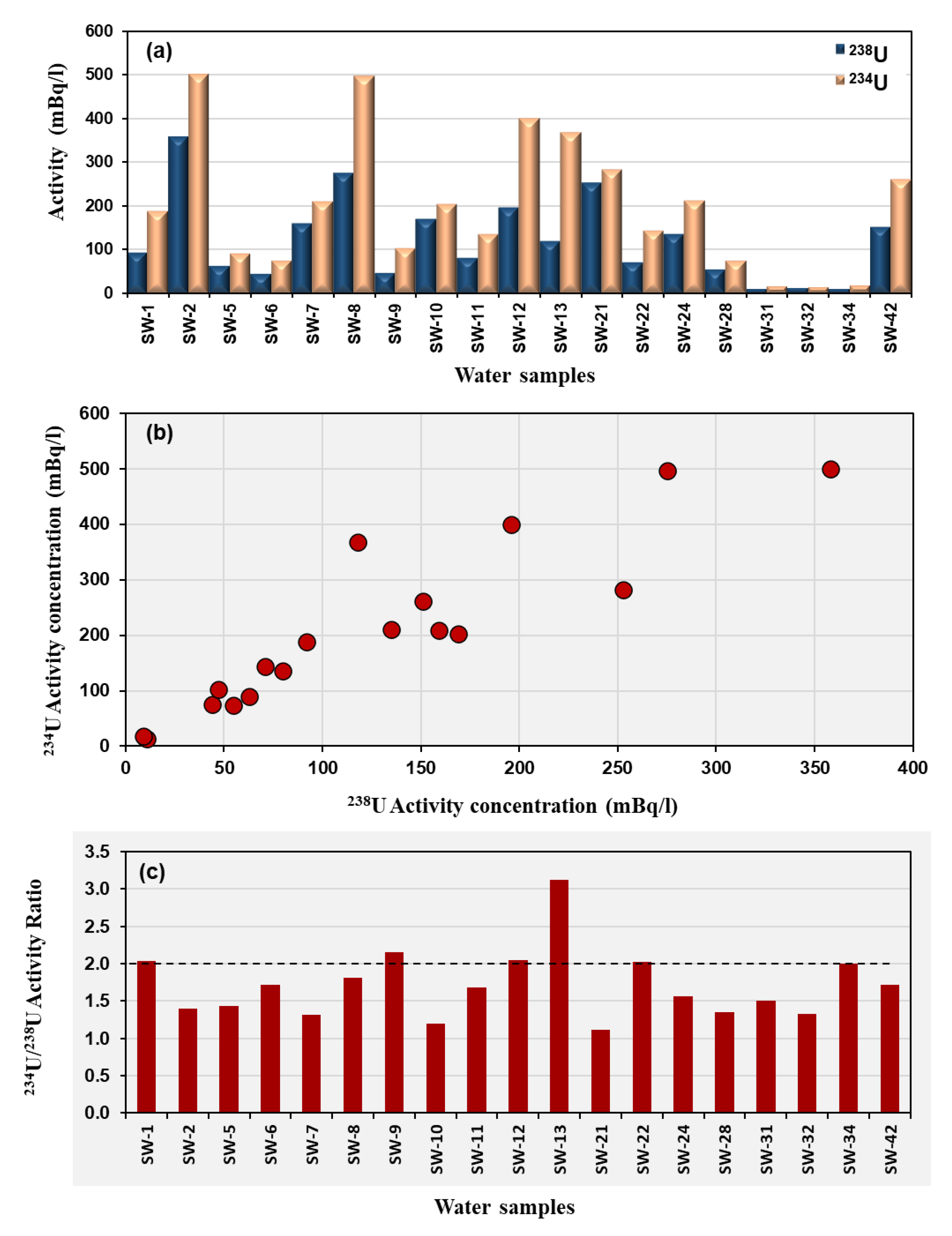

Table 2).

238U ranges from 0.009 to 0.358 Bq/L with a mean value around 0.12 Bq/L.

234U ranges from 0.014 to 0.500 Bq/L, averaging about 0.20 Bq/L. The total uranium concentration varies from 0.75 to 29.3 ppb, showing large spatial variability. The activity concentrations of

234U and

238U in the studied region are illustrated in

Figure 7a. A positive correlation is noted between the activity concentration values of

234U and

238U in the analyzed samples (

Figure 7b). This correlation is associated with the leaching of both uranium isotopes into the groundwater as it flows through the faults and fissures within the reservoir rocks [

38,

39]. The activity ratio

234U/

238U ranges from 1.11 to 3.11, with an overall average of about 1.71 (

Figure 7c).

The highest total uranium concentration is observed in sample SW-2 (29.3 ppb), which also shows one of the highest

238U activity (0.358 Bq/L) but a comparatively lower activity ratio (1.39). This indicates less isotopic fractionation, possibly reflecting recent uranium mobilization from host minerals without strong preferential leaching of

234U. In contrast, samples with lower uranium contents but higher

234U/

238U ratios (e.g., SW-13 = 3.11) suggest older groundwater-rock interaction and enhanced alpha-recoil effects, which enrich

234U in solution relative to

238U (

Table 2).

The range of the

234U/

238U ratio confirms that the groundwater is typical and aligns with global values between 1 and 2. The groundwater from these wells exhibits normal

234U/

238U isotopic ratios, which indicates that the waters are relatively young and contain low amounts of uranium. These findings suggest that uranium is not largely dissolving in the study area, even under oxidizing conditions. This is likely due to its concentration in refractory minerals such as zircon, monazite, and xenotime [

4], which are resistant to weathering, especially in low-temperature environments. In addition, the low weathering rate limits the migration of uranium in the study area [

9]. Consequently, only minimal redistribution of labile uranium has occurred occasionally forming uranyl precipitation associated with alteration process. This interpretation is reinforced by the presence of kasolite along fractured zones in the aplite-pegmatite of the Jabal Sayid area [

5]. Uranyl mineralization in the Sayid-Mahd Adhab region is likely originated from the precipitation of minerals near the surface due to circulating oxic groundwater. The ongoing preferential leaching of

234U from uranyl mineralization, driven by recoil processes, suggests the existence of weakly circulating groundwater. This type of groundwater encourages the preferential mobilization of

234U, resulting in mineralization that is low in

234U [

7].

The variability in uranium concentration and isotopic ratios reflects the influence of both geochemical environment and hydrochemical composition. In groundwater where fluoride concentrations are elevated, uranium tends to form stable uranyl-fluoride complexes that enhance uranium solubility even under slightly alkaline and oxidizing conditions [

34,

36]. This explains why samples such as SW-2, SW-8 and SW-21 which likely occur in areas of higher TDS and fluoride, show elevated uranium contents (

Table 1 and

Table 2). These samples show lower

234U/

238U activity ratios (~1.1–1.4) which indicate recent mobilization of uranium from mineral surfaces or adsorption–desorption processes driven by high fluoride and salinity. On the other hand, Higher ratios (>2) suggest prolonged contact with aquifer rock and alpha-recoil effects.

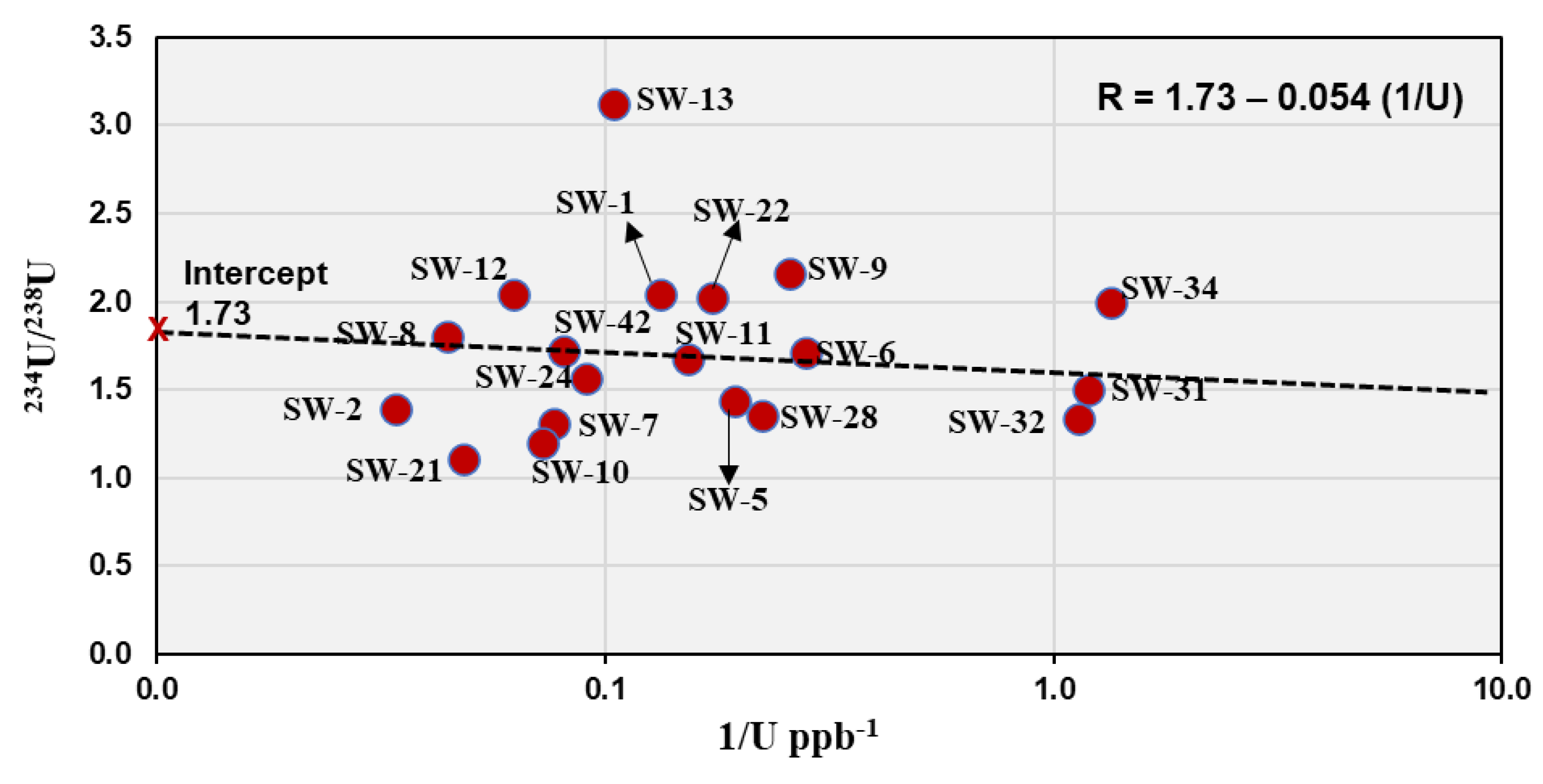

The relationship between the

234U/

238U AR and the reciprocal of total uranium concentration (1/U) was evaluated to assess whether uranium isotopic variations are governed by open-system α-recoil addition or by water mixing processes (

Figure 8). In the analyzed groundwater samples, the regression analysis yielded the equation:

R = 1.73 - 0.054 (1/U)

The scatter of data points supports the open-system recoil-addition model. The samples with low total U (< 5 ppb) such as SW-9 and SW-34 exhibit high activity ratios (> 2), whereas samples with high uranium (> 20 ppb) such as SW-2 and SW-21 display lower ratios (1.1–1.8). Correlation with the hydrochemical data shows that samples with higher fluoride and TDS contents tend to have lower activity ratios (

Table 1 and

Table 2), while low-salinity waters exhibit higher ratios due to longer residence times and cumulative

234U enrichment by recoil.

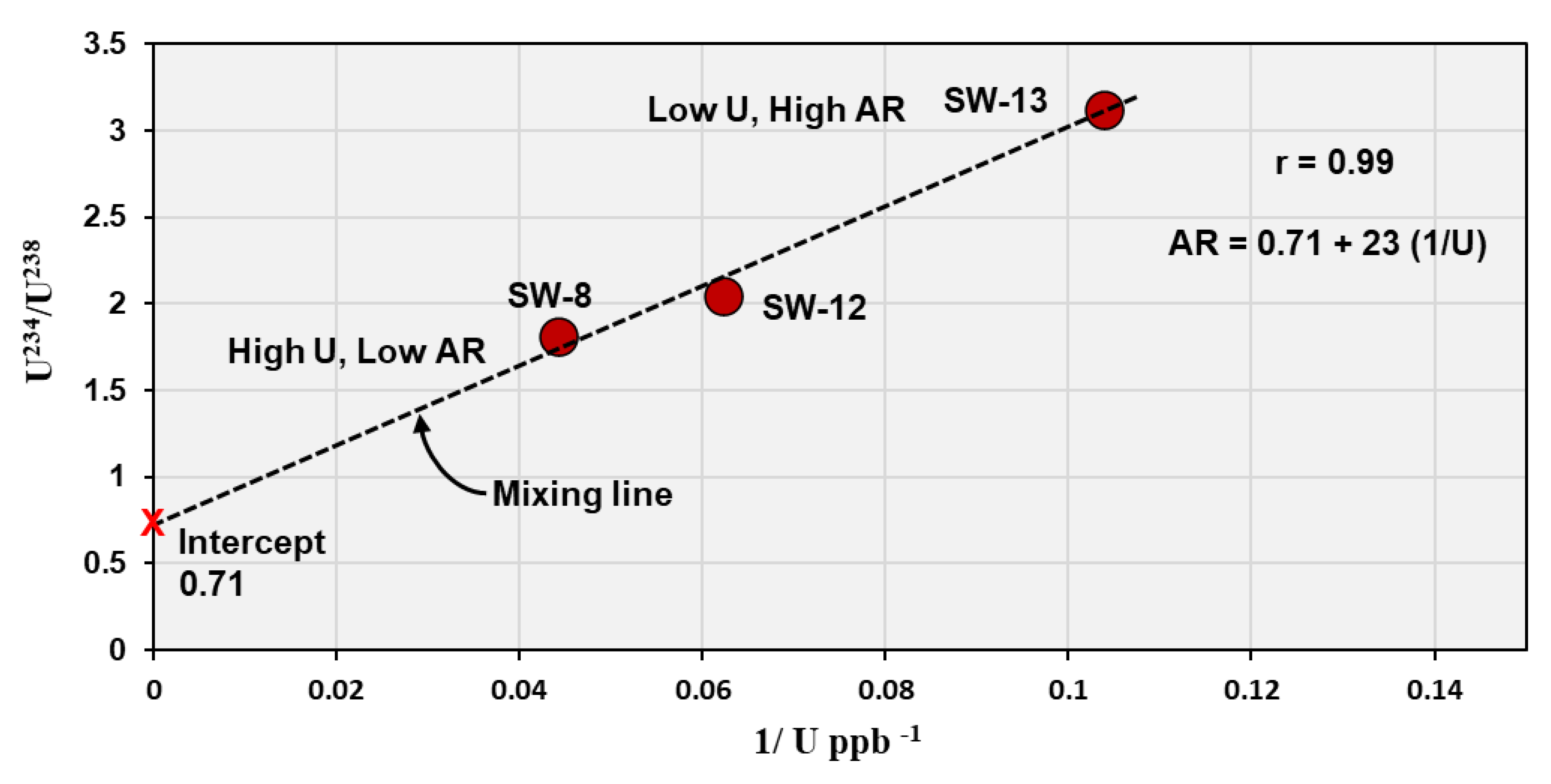

Minor deviations from the trend, particularly for samples such as SW-8 and SW-13, may reflect partial mixing between two water components: (1) a fluoride-rich, high-U / low-AR water (SW-8 type), and (2) a low-U / high-AR water (SW-13 type). These samples are located northern of Jabal Sayid area close to sample SW-12 which have intermediate composition (

Figure 2 and

Figure 8). A distinct linear relationship is observed between the activity ratio and the reciprocal of uranium concentration in these three groundwater samples (

Figure 9), expressed by the regression equation:

AR = 0.71 + 23 (1/U)

This strong positive correlation indicates a binary mixing trend between two contrasting endmembers. The intercept value (~0.71) represents the uranium-rich endmember, which likely corresponds to groundwater in contact with uranium mineralization zones present in Jabal Sayed. This source shows high uranium concentrations and an activity ratio close to equilibrium. With increasing distance from these mineralized zones, uranium concentrations decrease while the activity ratio increases, reflecting progressive mixing with uranium-poor water enriched in 234U due to preferential leaching and recoil effects. It is noteworthy that this linear trend was only observed in these three closely spaced samples, whereas other samples from the wider region did not show similar behavior. This suggests that the mixing process is localized, possibly controlled by small-scale hydrological or geochemical interactions around the uranium-bearing rocks. These findings highlight the significance of uranium isotopic composition as a sensitive tracer for detecting localized groundwater mixing and for assessing the hydrogeochemical influence of nearby mineralized zones on the aquifer system.

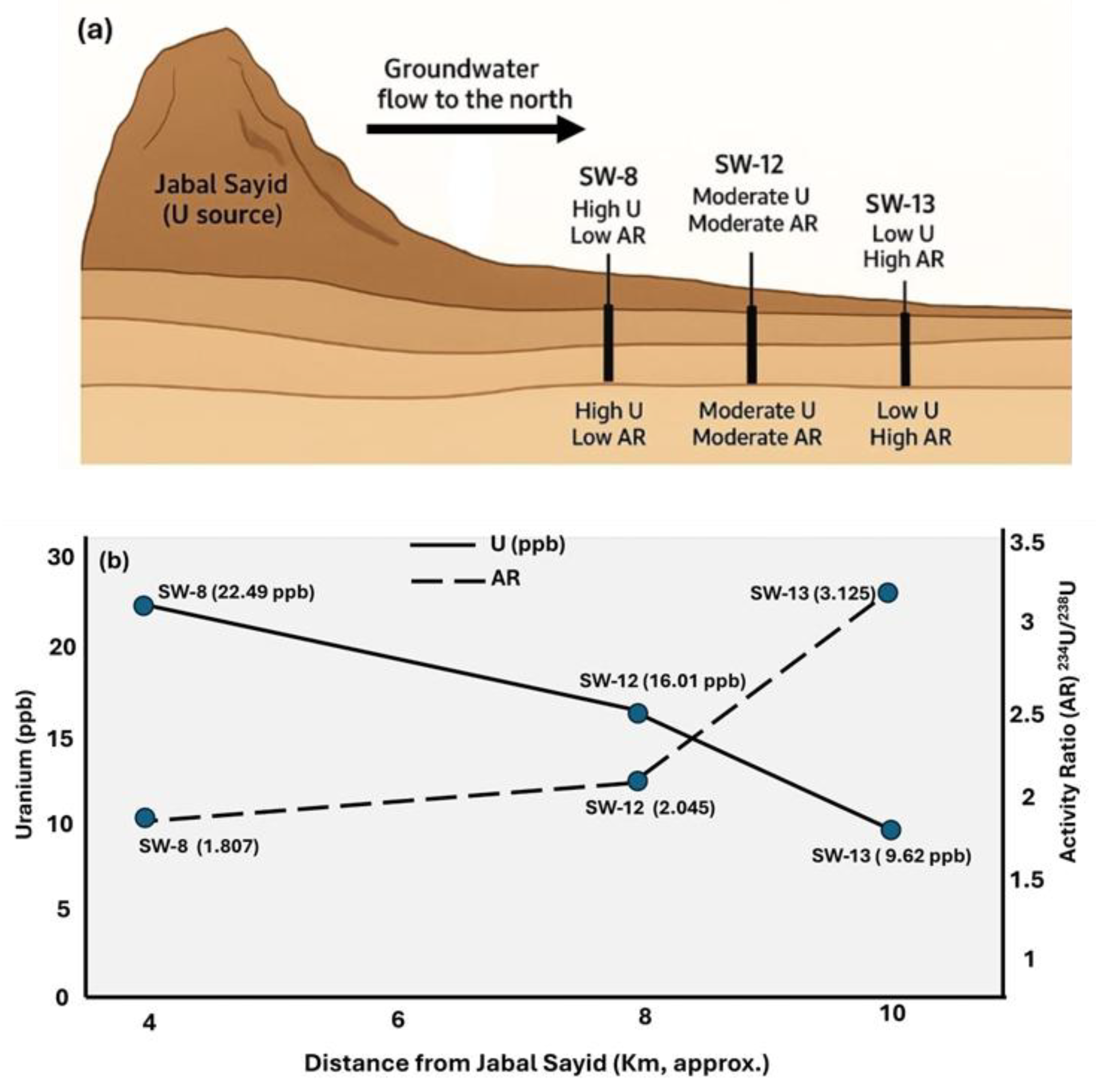

A Conceptual illustration (

Figure 10) shows groundwater flows northward from the uranium mineralization zone through the shallow aquifer system. The three wells (SW-8, SW-12, and SW-13) are located approximately 4, 8, and 10 km north of the source, respectively. The schematic plot shows uranium concentration gradually decreases, while the activity ratio (²³⁴U/²³⁸U) increases with distance from Jabal Sayid, indicating progressive uranium leaching and isotopic fractionation along the groundwater flow path.

5.4. Environmental Implications

The observed enrichment of uranium in fluoride-rich groundwater has important environmental and health implications. In the studied area, most samples exhibit uranium concentrations approaching the World Health Organization [

40] guideline value of 30 µg/L (≈0.37 Bq/L for

238U), particularly in wells characterized by elevated fluoride and salinity. The coexistence of high fluoride and uranium levels suggests a common geochemical control, where both elements are released from U-F-bearing minerals and stabilized in solution by fluoride complexation. Such conditions can lead to chronic exposure risks when groundwater is used for drinking or irrigation. From a management perspective, these results emphasize the need for regular monitoring of uranium and fluoride in shallow groundwater, especially in zones with high EC and TDS values that indicate intensive mineral dissolution. Implementation of defluoridation and uranium removal techniques, such as adsorption on activated alumina or reverse osmosis, may be required to maintain water quality within safe limits. Monitoring of uranium and fluoride in the site of sample SW-2 should take special consideration, since this sample is located remote from the uranium occurrence in Sayid area and at the same time shows the highest uranium content in the study area.

6. Conclusions

The present study investigates the chemical controls on uranium activity in the shallow groundwater of Jabal Sayid-Mahd Adhab region, Saudi Arabia. The study focuses on anion chemical composition, pH, TDS, EC, and temperature. The physicochemical characteristics suggest that the studied shallow groundwater is moderately to highly saline, controlled by water-rock interactions, evaporative processes, and anthropogenic inputs. The combined isotopic and hydrochemical evidence indicates that uranium mobility in the studied shallow groundwater is governed primarily by highly soluble uranyl–fluoride species. This is indicated by the strong positive correlations between fluoride ion and the activities of 238U, 234U and total uranium content and the stronger relationships between uranium and salinity-related parameters (EC and TDS) than with pH or temperature. The relatively short residence time and contact with the oxidizing zone promote the formation of this uranyl–fluoride speciation.

In the Sayid-Mahd Adhab region, the average activity concentrations of 234U and 238U in water samples were found to be 0.2 Bq/L and 0.12 Bq/L, respectively, with a calculated 234U/238U ratio averaging 1.71. The 234U/238U ratios varied from 1.11 to 3.11, aligning with global values, and suggest the presence of younger waters with minimal contributions from water-rock interactions, likely due to uranium being concentrated in resistant minerals. Uranium concentrations ranged from 0.75 to 29.3 ppb, typical for oxidizing groundwater. Anomalous ratios in some wells stem from mechanisms like alpha recoil and isotopic fractionation, which enhance 234U solubility.

The positive correlation between uranium and salinity parameters (EC and TDS), together with the weak AR–1/U correlation, confirms that uranium enrichment occurs mainly in fluoride-rich, high-salinity zones, whereas elevated activity ratios mark older, low-salinity recharge waters. The obtained isotopic data supports the open-system recoil-addition model. Minor deviations from this model may reflect partial mixing between two water components: (1) a fluoride-rich, high-U/low-AR water, and (2) a low-U/high-AR water. The localized mixing occurs in some wells in the northern of Jabal Sayid area. Overall, the 234U/238U (AR) vs. 1/U relationship in the studied samples indicates that uranium behavior in the shallow aquifer is dominated by open-system leaching and fluoride-induced solubility, with local binary mixing superimposed in a few sites. The coexistence of elevated uranium and fluoride levels highlights potential health and environmental risks, necessitating regular monitoring and water-treatment measures to ensure safe groundwater use.

Author Contributions

Methodology, H.A., Y.D. and A.S.; Formal analysis, H.A. and Y.D.; Investigation, H.A., Y.D. and A.S.; Resources, H.A., Y.D. and A.S..; Data curation, Y.D.; Writing—original draft, H.A., Y.D. and A.S.; Writing—review and editing, H.A., Y.D. and A.S.; Visualization, H.A. and Y.D.; Supervision, H.A.; Project administration, S.A.; Funding acquisition, H.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research work was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia under grant no. (IPP:1151-145-2025).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

This research work was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia under grant no. (IPP:1151-145-2025). The authors, therefore, acknowledge with thanks DSR for technical and financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ahmed, M.I. Report on the reconnaissance survey in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabian Directorate General of Mineral Resources. Open-File Report DGMR-69, 1957.

- Turkistany, A.R.; Ramsay, C.R. Mineralized apogranite associated with alkali granite at Jabal Sa’id, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Deputy Minstry Miner. Resour., 1982, 78–88.

- Hackett, D. Jabel Sayid rare earth prospect: drilling results and resource evaluation. Saudi Arabian Deputy Ministry for Mineral Resources Open-File Report DGMR-OF-04-26, 1984.

- Hackett, D. Mineralized aplite-pegmatite at Jabel Sayid, Hijaz region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Afr. Earth Sc. 1986, 4, 257–267. [Google Scholar]

- Dawood, H.Y.; Harbi, H.M.; Abd El-Naby, H.H. Genesis of kasolite associated with aplite-pegmatite at Jabel Sayid, Hijaz region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2010, 37, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, K.A.; Jeon, H.; Andresen, A.; Li, S.Q.; Harbi, H.M.; Hegner, E. U-Pb zircon geochronology and Nd-Hf-O isotopic systematics of the Neoproterozoic Hadb adh Dayheen ring complex, Central Arabian Shield, Saudi Arabia. Lithos 2014, 206–207, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, Y.H.; Abd El-Naby, H.H.; Ghaleb, B. U-series isotopic composition of kasolite associated with aplite-pegmatite at Jabal Sayid, Hijaz region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Arab. J. Geosci. 2014, 7, 2881–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghazi, A.K.M.; Iaccheri, L.M.; Bakhsh, R.A.; Kotov, A.B.; Ali, K.A. Sources of rare-metal-bearing A-type granites from Jabel Sayed complex, northern Arabian shield, Saudi Arabia. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2015, 107, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Naby, H.H.; Dawood, Y.H.; Sabtan, A.; Al Yamani, M. Significance of radioelements distribution in the Precambrian rocks of Jabel Sayid, western Saudi Arabia, using spectrometric and geochemical data. Resour. Geol. 2021, 71, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aseri, A.A. Rare-metal Alkaline Granite from The Arabian Shield, Saudi Arabia. Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 6822, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dawood, Y.H.; Abd El-Naby, H.H. Genesis of uranyl mineralization in the Arabian Nubian Shield: A review. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2022, 225, 105047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Naby, H.H.; Dawood, Y.H. The Geochemistry, Petrogenesis, and Rare-Metal Mineralization of the Peralkaline Granites and Related Pegmatites in the Arabian Shield: A Case Study of the Jabal Sayid and Dayheen Ring Complexes, Central Saudi Arabia. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skwarzec, B.; Boryło, A.; Strumin´ska, D. 234U and 238U isotopes in water and sediments of the southern Baltic. J Environ Radioact 2002, 61, 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plater, A.J.; Ivanovich, M.; Dugdale, R.E. Uranium series disequilibrium in river sediments and waters: the significance of anomalous activity ratios. Appl Geochem 1992, 7, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischer, R.L. Isotopic disequilibrium of uranium: alpharecoil damage and preferential solution effects. Science 1980, 207, 979–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrzak-Flis, Z.; Kamin´ska, I.; Chrzanowski, E. Uranium isotopes in waters and bottom sediments of rivers and lakes in Poland. Nukleonika 2004, 49(2), 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Dawood, Y.H.; Abd El-Naby, H.H. Mineralogy and genesis of secondary uranium mineralization, Um Ara area, South Eastern Desert, Egypt. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2001, 32/2, 317–323. [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Naby, H.H. The genesis of the supergene REE-fluorocarbonate and uranyl mineralization in the Abu Rusheid area of the South Eastern Desert of Egypt. Geosci. J. 2025, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosholt, J.N. Isotopic composition of uranium and thorium in crystalline rocks. J Geophys Res 1983, 88, 7315–7330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmond, J.K.; Cowart, J.B. Groundwater. In: Uranium-series disequilibrium. Applications to earth, marine and environmental sciences, 2nd ed.; Ivanovich, M., Harmon, R.S. Eds; Oxford Science Publications, Oxford., 1992.

- Dosseto, A.; Bourdon, B.; Turner, S.P. Uranium-series isotopes in river materials: insights into the timescales of erosion and sediment transport. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2008; 265, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Boryło, A.; Skwarzec, B. Activity disequilibrium between 234U and 238U isotopes in natural environment. J Radioanal Nucl Chem. 2014, 300(2), 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonotto, D.M. The dissolved uranium concentration and 234U/238U activity ratio in groundwaters from spas of southeastern Brazil. J. Environ. Radioact. 2017, 166, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuribayashi, C.; Miyakawa, K.; Ito, A.; Tanimizu, M. Large disequilibrium of 234U/238U isotope ratios in deep groundwater and its potential application as a groundwater mixing indicator. Geochem. J. 2025, 59, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, A.; Devesa, R.; Valles, I.; Serrano, I.; Soler, J.; Blazquez, S.; Ortega, X.; Matia, L. Distribution of uranium isotopes in surface water of the Llobregat river basin (Northeast Spain). J Environ Radioact 2010, 101, 1048–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmond, J.K.; Cowart, J.B. The theory and uses of natural uranium isotopic variations in hydrology. At Energ Rev 1976, 14, 621–679. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanovich, M.; Harmon, R. Uranium series disequilibrium: applications to environmental problems. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1992.

- Dunlop, H.M.; Kemp, J.; Calvez, J.Y. Geochronology and isotope geochemistry of the Bi’r Umq mafic-ultramafic complex and Arj group volcanic rocks, Mahd adh Dhahab quadrangle, central Arabian shield: Saudi Arabian. Deputy Ministry for Mineral Resources Open-File Report BRGMOF-07-7, 1986, 38 p.

- Hargrove, U.S. Crustal evolution of the Neoproterozoic Bi’r Umq suture zone, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: geochronological, isotopic, and geochemical constraints. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Texas at Dallas, 2006; 343p.

- Calvez, J.Y.; Alsac, C.; Delfour, J.; Kemp, J.; Pellaton, C. Geologic evolution of western, central and eastern parts of the northern Precambrian shield: Saudi Arabian. Deputy Ministry for Mineral Resources Open-file Report BRGM-OF-03-17, 1983, 57 p.

- Turkistany, A.R.A.; Koyama, K. An X-ray study of minerals in the radioactive pegmatite zone at Jabal Sayid, Saudi Arabia. In: Evolution and Mineralization of the Arabian-Nubian Shield; Al Shanti, A.M., Bull. Inst. Appl. Geol. King Abdulaziz Univ. (Jiddah), Pergamon Press, Oxford, 1980; 3, 99–104.

- Elliott, J.E. Peralkaline and peraluminous granites and related mineral occurrences of the Arabian Shield, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Saudi Arabian Deputy Ministry for Mineral Resources Open-File Report USGS-OF-03-56, 1983, 37 p.

- Langmuir, D. Uranium solution–mineral equilibria at low temperatures with applications to sedimentary ore deposits. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1978, 42(6), 547–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, N.; Kumar, A.; Singh, D.K.; Kumar, S.; Husain, M.A.; Neidhardt, H.; Elisabeth, E.; Marks, M.; Biswas, A. Testing the hypothesis of fluoride and uranium co-mobilization into groundwater by competitive ion exchange in alluvial aquifers of Southern Punjab, India. J Hazard Mater. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smedley, P.L.; Kinniburgh, D.G. Uranium in natural waters and the environment: Distribution, speciation and impact. Appl. Geochem. 2023, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, A.K.; Sujathan, S.; Ekamparam, A.S.S.; Singh, A. The Role of Manganese Carbonate Precipitation in Controlling Fluoride and Uranium Mobilization in Groundwater. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2021, 5, 270–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabous, A.A.; Osmond, J.K. Uranium isotopic study of artesian and pluvial contributions to the Nubian aquifer, Western desert, Egypt. J Hydrol 2001, 243, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinelli, E.; Lima, A.; De Vivo, B.; Albanese, S.; Cicchella, D.; Valera, P. hydrogeochemical analysis on Italian bottled mineral waters: effects of geology. J Geochem Explor 2010, 107, 317–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidou, A.; Samaropoulos, I.; Efstathiou, M.; Pashalidis, I. Uranium in ground water samples of Northern Greece. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 2011, 289, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, W.H.O. Guidelines for drinking-water quality: Fourth edition incorporating the first and second addenda, 2022.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).