Submitted:

23 October 2025

Posted:

27 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Indolent Intestinal Lymphoma and LPD

2.1. Indolent Intestinal T-cell Lymphoma

2.1.1. Involved Sites and Gross Presentation

2.1.2. Histology

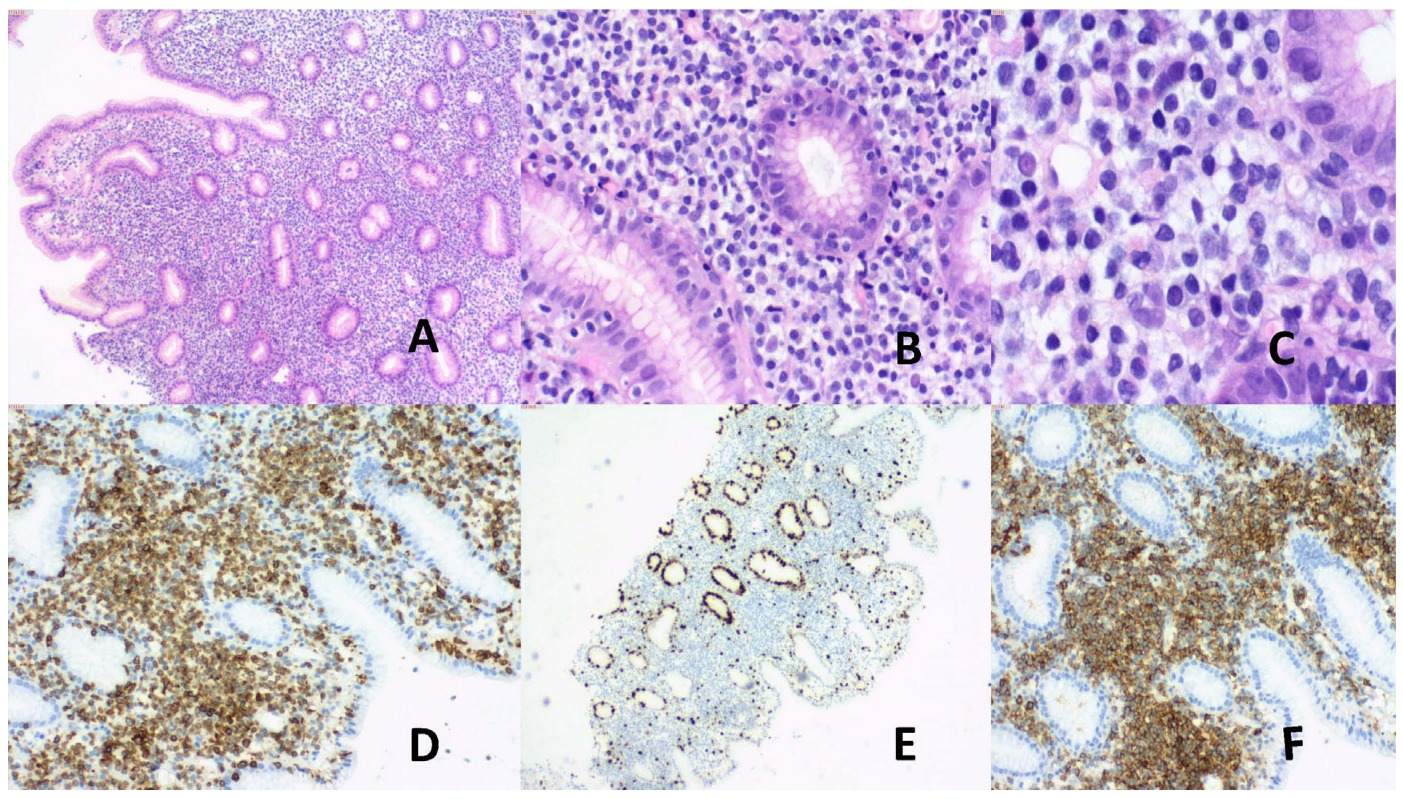

2.1.3. Immunophenotype

2.1.4. Genetic Alterations

2.1.6. Treatment

2.2. Indolent Intestinal NK-cell Lymphoproliferative Disease (iINKLPD)

2.2.1. Sites of Involvement and Gross Findings

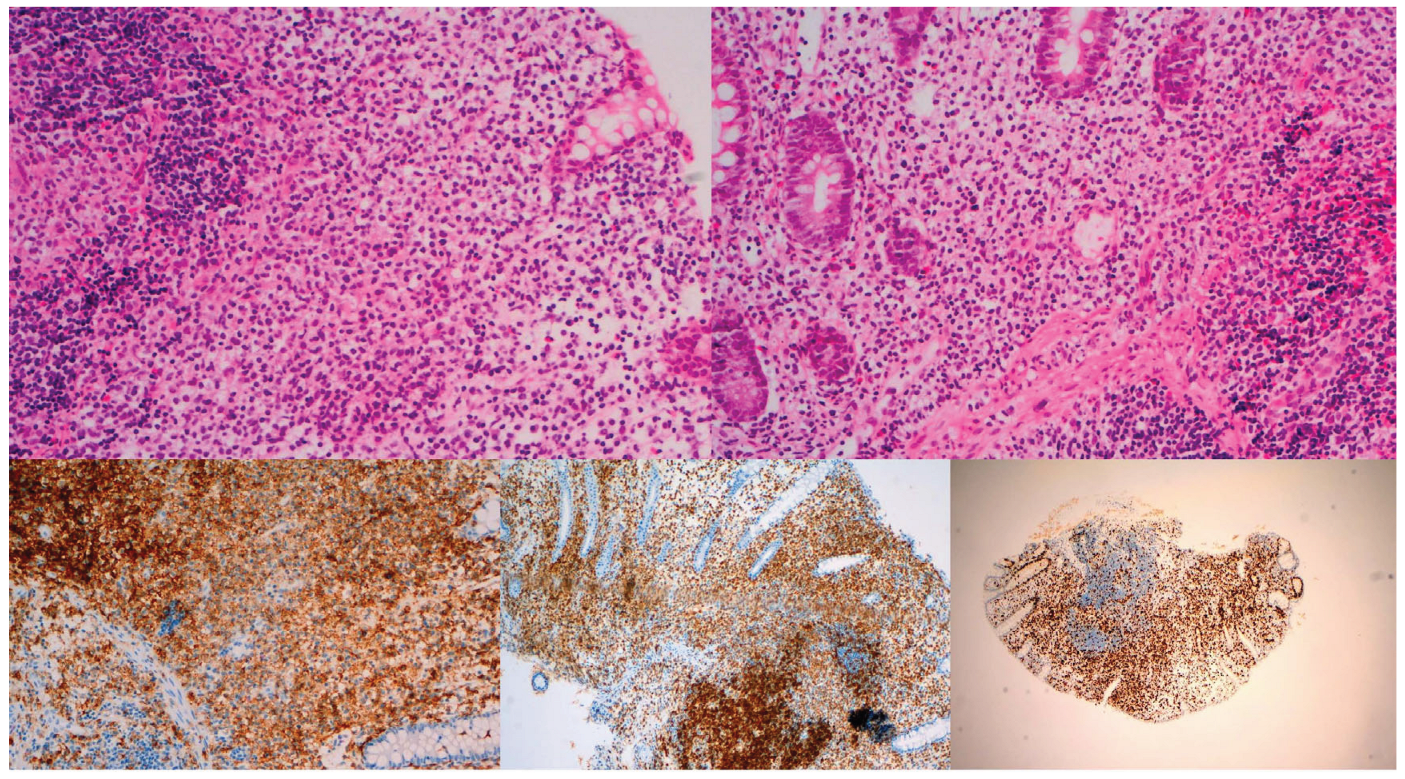

2.2.2. Histology

2.2.3. Immunophenotype

2.2.4. Etiology and EBV Status

2.2.5. Neoplastic or Non-Neoplastic?

2.2.6. Treatment

2.3. Differential Diagnoses of iITCL and iINKLPD from Other Intestinal NK- or T-Cell Lymphomas

| iITCL | iINKLPD | ENNKTL | MEITL | EATL | |

| Age (years) | CD4+: Median 51 CD8+: Median 45 |

30-90 | 35-58 | Median 54-67 | Median 61 |

| Sex | M>F | M>F | M>F | M>F | M>F |

| Predominant sites involved |

Small intestine, colon | Stomach, small intestine, colon, gall bladder | GI tract | Small intestine | Small intestine (mostly jejunum) |

| Multifocality | Common | Yes | 27% | 20-35% | 32-54% |

| Enteropathy association | No | No | No | No | 80% |

| Metastasis | BM, PB, tonsil, mesenteric LN | Rarely mesenteric LN | Multiple extraintestinal sites, frequently Stage IV | LN, lung, liver, brain, skin | LN, BM, lung, liver |

| Transformation | Reported | NR | NA | NA | NA |

| Depth involved | Mucosa, sometimes also MM and SM | Mucosa | Full thickness | Full thickness | Often full thgickness |

| Histology | Small /medium atypical cells, non-destructive dense infiltrate, no/rare epithelial invasion, no angioinvasion | Medium atypical cells, small nucleoli, pale granular cytoplasm, circumscribed confluent infiltrate, glands displaced, epithelial invasion +/-, necrosis +/- | Range of atypical cells, geographic necrosis, epithelial invasion, angiocentricity, angioinvasion, angiodestruction | Monotonous atypical cell infiltrates, necrosis, epithelial invasion, severe inflammatory backdrop, “starry sky” appearance | Range of atypical cells, epithelial invasion, angioinvasion, angiodestruction, features of CD |

| Molecular/genetic alterations | STAT3, JAK2,, JAK2::STAT3 fusion, STAT5, SOCS1, KMT2D, TET2, DNMT3A, EZH2, TNFAIP3, IL2, RHOH, TNIP3, TCR | JAK3, RUNX1T1, CIC, ERB4, SETD5 | PRDM1, PTPRK, HACE1, FOXO3, STAT3, JAK3, STAT5B, BCOR, KMT2D, ARID1A, EP300, TCR (in T-cell type) | Myc, SETD2, STAT3, STAT5, JAK1, KAK3, TCR | JAK1, STAT3, TET2, KMT2D, DOX3X, TNFA1P3, TNIP3, POT1, TP53, CD58, FAS, B2M, TCR |

| Immunophenotype | CD3+, CD4+CD8-, CD4-CD8+,CD4+CD8+, CD4-CD8-, TCR+, KI67 low* | CD56+, CD2+, cCD3+, CD7+, TIA1+, GZB+, TCR-, Ki67 high | CD56+ (NK-cell type), cCD3+, sCD3+ (T-cell type), CD2+, TIA1+, GZB+, perforin+, TCR- (in NK-cell type), TCR+ (in T-cell type), Ki 67 high | CD2+, sCD3+, CD7+, CD8+, CD56+/-, TIA1+, TCR+, Ki67 high | CD3+, CD7+, TIA1+, GZB+, perforin+, Ki67>50%, CD30+/EMA+ (in anaplastic cases) |

| EBV | Negative@ | Negative | Positive | Negative | Negative |

3. Indolent Non-Intestinal NK- or T-Cell LPD

4. Indolent T-Lymphoblastic Proliferation (iTLBP)

5. Indolent Cutaneous LPD

5.1. PcutCD4+TLPD

5.2. PcutacCD8+TLPD

6. Conclusions

Ethics Committee Approval

Funding

Acknowledgment

References

- Chan J; Alaggio, R. Intestinal T-cell and NK-cell lymphoid proliferations and lymphomas. Introduction. In: WHO Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours, 5th ed. IARC: Lyons, France, 2025. Available online: https://tumourclassification.iarc.who.int/chapters/63 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Bhagat, G; Takeuchi, K; Naresh, KN; Dave, SS. tract. In WHO Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours, 5th ed; Chan, J, Washington, MK, Eds.; de Jong, D, Eds. IARC: Lyons, France, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, W; Takeuchi, K; Ferry, JA; Chang, CL. tract. In WHO Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours, 5th ed; Chan, J, Ed.; Lee Wood, B, Eds. IARC: Lyons, france, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonnel, F; Lavergne, A; Messing, B; Tsapis, A; Berger, R; Galian, A; Nemeth, J; Brouet, JC; Rambaud, JC. Extensive Small Intestinal T-Cell Lymphoma of Low-Grade Malignancy Associated with a New Chromosomal Translocation. Cancer, 1994, 73, 1286–1291.

- Egawa, N; Fukayama, N; Kawaguchi, K; Hishima, Y; Funata, N; Ibuka, T; Koike, M; Miyashita, H; Tajima, T. Relapsing Oral and Colonic Ulcers with Monoclonal T-cell Infiltration. Caner, 1995, 75, 1728–1733. [CrossRef]

- Tsutsumi, Y; Inada, K; Morita, K; Suzuki, T. T-cell Lymphomas Diffusely Involving the Intestine: Report of Two Rare Cases. Jpn J Clin Oncol 1996, 26, 264–272. [CrossRef]

- Hirakawa, K; Fuchigam, T; Nakamura, S; Daimaru, Y; Ohshima, K; Sakai, Y; Ichimaru, T. Primary Gastrointestinal T-cell Lymphoma Resembling Multiple Lymphomatous Polyposis. Gastroenterol 1996,778-782. [CrossRef]

- Carbonnel, F; d’Almagne, H; Lavergne, A; Matuchansky, C; Brouet, JC; Sigaux, F; Beaugerie, L; Nemeth, J; Coffin, B; Cosnes, J etal. The Clinicopathological Features of Extensive Small Intestinal CD4 T Cell Infiltration. Gut 1999, 45, 662–667.

- Zivny, J; Banner, BF; Agrawal, S; Pihan, G; Barnard, G. CD4+ T-cell Lymphoproliferative Disorder of the Gut Clinically Mimicking Coeliac Sprue. Dig Ds Sci 2004, 49, 551–555.

- Svrcek, M; Garderet, L; Sebbagh, V; Rosenzwajg, M; Parc, Y; Lagrange, M; Bennis, M; Lavergne-Slove, A; Flejou, J; Fabiani, B. Small Intestinal CD4+ T-cell Lymphoma: A Rare Distinctive Clinicopathological Entity Associated with Prolonged Survival. Virchows Arch 2007, 451, 1091–1093. [CrossRef]

- Perry, AM; Warnke, RA; Hu, Q; Gaulard, P; Copie-Bergman, C; Alkan, S; Wang, H; Cheng, JX; Bacon, CM; Delabie, J etal. Indolent T-cell Lymphoproliferative Disease of the Gastrointestinal Tract. Blood 2013, 122, 3599–2606. [CrossRef]

- Ranheim, EA; Jones, C; Zehnder, JL; Warnke, RA; Yuen, A. Spontaneously Relapsing Clonal, Mucosal Cytotoxic T-cell Lymphoproliferative Disorder: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Am J Surg Pathol 2000, 24, 296–301.

- Margolskee, E; Jobanputra, V; Lewis, SK; Alobeid, B; Green, PHR; Bhagat, G. Indolent Small Intestinal CD4+ T-cell Lymphoma is a Distinct Entity with Unique Biologic and Clinical Features. Plos One 2013, 8, e68343. [CrossRef]

- Leventaki, V; Manning, JT Jr; Luthra, R; Mehta, P; Oki, Y; Romaguera, J; Medeiros, LJ; Vega, F. Indolent Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma Involving the Gastrointestinal Tract. Hum Pathol 2014, 45, 421–426. [CrossRef]

- Malamut, G; Meresse, B; Kaltenbach, S; Derrieux, C; Verkarre, V; Macintyre, E; Ruskone-Fourmestraux, A; Fabiani, B; Radford-Weiss, I;Brousse, N; Hermine, O etal. Small Intestinal CD4+ T-cell Lymphoma is a Heterogeneous Entity with Common pathology features. Clin gastroenterol Hepatol 2014, 12, 599–608. [CrossRef]

- Mendes, LST; Attygalle, AD; Cunningham, D; Benson, M; Andreyev, J; Gonzales-de-Castro, D; Wootherspoon, A. CD4-positive Small T-cell Lymphoma of the Intestine Presenting with Severe Bile-acid Malabsorption: A Supportive Symptom Approach. Br J Haematol 2014, 167, 265–269. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X; Ng, CS; Chen C; Yu, G, Yin, W. An Unusual Case Report of Indolent T-cell Lymphoproliferative Disorder with Aberrant CD20 Expression Involving the Gastrointestinal Tract and Bone Marrow. Diagn Pathol 2018, 13, 82.

- Nagaishi, T; Yamada, D; Suzuki, K; Fukuyo, R; Saito, E; mFukuda, M; Watanabe, T; Tsugawa, N; Takeuchi, K; Yamaoto, K. Indolent T Cell Lymphoproliferativ Disorder with Villous Atrophy in Small Intestine Diagnosed by Single-Balloon Enteroscopy. Clin J Gastroenterol 2019, 12, 434–440. [CrossRef]

- Perry, AM; Bailey, NG; Bonnett, M; Jaffe, ES; Chan, WC. Disease Progression in a Patient with Indolent T-cell Lymphoproliferative Disease of the Gastrointestinal Tract. Int J Surg Pathol 2019, 27, 102–107.

- Sharma, A; Oishi, N; Boddicker, RL; Hu, G; Benson, HK; Ketterling, RP; Greipp, PT; Knutson, DL; Kloft-Nelson, SM; Eckloff, BW etal. Recurrent STAT3-JAK2 Fusions in Indolent T-cell Lymphoproliferative Disorder of the Gastrointestinal Tract. Blood 2018, 131, 2262–2266.

- Guo, L; Wen, Z; Su, X; Xiao, S; Wang, Y. Indolent T-cell Lymphoproliferative Disease with Synchronous Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma. A Case Report. Medicine 2019, 98, e15323.

- Wu, J; Li, LG; Zhang, XY; Wang, LL; Zhang, L; Xiao, YJ; Xing, XM; Lin, DL. Indolent T-cell Lymphoproliferative Disorder of the Gastrointestinal Tract: An Uncommon Case with Lymph Node Involvement and the Classic Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. J Gastroenterol Oncol 2020, 11, 812–819.

- Soderquist, CR; Patel, N; Murty, VV; Betman, S; Aggarwai, N; Young, KH; Xerri, L; Leeman-Neill, R; Lewis, SK; Green, PH etal. Genetic and Phenotypic Characterization of Indolent T-cell Lymphoproliferative Disorder of the Gastrointestinal Tract. Haematologica 2020, 105, 1895–1906. [CrossRef]

- Zanelli, M; Zizzo, M; Sanguedolce, F; Martino, G; Soriano, A; Ricci, S; Ruiz, CC; Anessi, V; Ascani, S. Indolent T-cell Lymphoproliferative Disorder of the Gastrointestinal Tract: A Tricky Diagnosis of a Gastric Case. Gastroenterol 2020, 20, 336.

- Takahashi, N; Tsukasaki, K; Kohri, M; Akuzawa, Y; Saeki, T; Okamura, D; Ishikawa, M; Maeda, T; Kawai, N; Matsuda, A etal. Indolent T-cell Lymphoproliferative Disorder of the Stomach Successfully Treated by Radiotherapy. J Clin Exp Hematopathol 202o,60,7-10. [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, MF; Nishimura, Y; Nishikori, A; Yoshino, T; Sato, Y. Primary Gastrointestinal T-cell Lymphoma and Indolent Lymphoproliferative Disorders: Practical Diagnostic and Treatment Approaches. Caners 2021, 13, 5774.

- Montes-Moreno, S; King, RL; Oschlies, I; Ponzoni,M; Goodlad, JR; Dotlic, S; Traverse-Glehen, A; Ott, G; Ferry, JA; Calaminici, M. Update on Lymphoproliferative Disorders of the Gastrointestinal Tract: Disease Spectrum from Indolent lymphoproliferations to Aggressive Lymphomas. Virchows Archiv 2020, 476, 667–681.

- Miranda, RN; Amador, C; Chan, JKC; Guitart, J; Rech, KL; Medeiros, LJ; Naresh, KN. Fifth Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues: Mature T-cell, NK-cell, and Stroma-Derived Neoplasms of Lymphoid Tissues. Mod Pathol 2024, 37, 100512.

- Wang, X; Yin, W; Wang, H. Indolent T-cell/Natural Killer-Cell Lymphomas/Lymphoproliferative Disorders of the Gastrointestinal Tract – What Have We Learned in the Last Decade? Lab Invest 2024, 104, 102028.

- Chuang, S; Tzioni, M; Chen, Z; Feng, Y; Shih, C; Casa, C; Du, M. Indolent EBV-positive T-cell Lymphoma of the Gastrointestinal with Metachronous Lesions Involved by Different Neoplastic Clones. Pathology 2024, 56, 431–434. [CrossRef]

- Attygalle, AD; Karube, K; Jeon, YK; Cheuk, W; Bhagat, G; Chan, JKC; Naresh, KN. The Fifth Edition of the WHO Classification of Mature T Cell, NK Cell and Stroma-Derived Neoplasms. J Clin Pathol 2025, 78, 217–232. [CrossRef]

- Quintanilla-Martinez, L; Bosch-Schips, J; Gasljevic, G; van den Brand, M; Balague, O; Anagnostopoulos, I; Ponzoni, M; Cook, JR; Dirnhofer, S; Sander, B etal. Exploring the Boundaries between Neoplastic and Reactive Lymphoproliferations: Lymphoid Neoplasms with Indolent Behavior and Clonal Lymphoproliferations – A Report of the 2024 EA4HP/SH Lymphoma Workshop. Virchows Archiv 2025, 487, 327–347.

- Vega, F; Chang, C; Schwartz, MR; Preti, HA; Younes, M; Ewton, A; Verm, R, Jaffe, ES. Atypical NK-cell Proliferation of the Gastrointestinal Tract in a Patient with Antigliadin Antibodies but not Coeliac Disease. Am J Surg Pathol 2006, 30, 539–544.

- Takeuchi, K; Yokoyama, M; Ischizawa, S; Terui, Y; Nomura, K; Marutsuka, K; Nunomura, M; Fukushima, N; Yagyuu, T; Nakamine, H et al. Lymphomatoid Gastropathy: A Distinct Clinicopathologic Entity of Self-limited Pseudomalignant NK-cell Proliferation. Blood 2010, 116, 5631–5637.

- Mansoor, A; Pittaluga, S; Beck, PL; Wilson, WH; Ferry, JA; Jaffe, ES. NK-cell Enteropathy: A Benign NK-cell Lymphoproliferative Disease Mimicking IntestinaL Lymphoma: Clinicopathologic Features and Follow-up in a Unique Case Series. Blood, 117, 1447-1452. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T; Megahed, N; Takata, K; Asano, N; Niwa, Y; Hirooka, Y; Goto, H. A Case of Lymphomatoid Gastropathy: An Indolent CD56-positive Atypical Gastric Lymphoid Proliferation, Mimicking Aggressive NK/T Cell Lymphomas. Pathol Res Pract 2011, 207, 786–789. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, J; Fujishima, F; Ichinohasama, R; Imatani, A; Asano, N; Harigae, H. A Case of Benign Natural Killer Cell Proliferative Disorder of the Stomach (Gastric Manifestation of Natural Killer Cell Lymphomatoid Gastropathy) Mimicking Extranodal Natural Killer/T-cell Lymphoma. Lek Lymphoma 2011, 52, 1803–1805. [CrossRef]

- McElroy, MK; Read, WL; Harmon, GS; Weidner, N. A Unique Case of an Indolent CD56-positive T-cell Lymphoproliferative Disorder of the Gastrointestinal Tract: A Lesion Potentially Misdiagnosed As Natural Killer/T-cell Lymphoma. Ann Diagn Pathol 2011, 15, 370–375. [CrossRef]

- Terai, T; Sugimoto, M; Uozaki, H; Kitagawa, T; Kinoshita, M; Baba, S; Yamada, T; Osawa, S; Sugimoto, K. Lymphomatoid Gastropathy Mimicking Extranodal NK/T Cell Lymphoma, Nasal Type: A case Report. World J Gastroenterol 2102, 18, 2140–2144.

- Ishibashi, Y; Matsuzono, E; Yokoyama, F; Ohara, Y; Sugai, N; Seki, H; Miura, A; Fujita, J; Suzuki, J; Fujisawa, T etal. A Case of Lymphomatoid Gastropathy: A Self-limited Pseudomalignant Natural Killer (NK)-Cell Proliferative Disease Mimicking NK/T-Cell Lymphomas. Clin J Gastroenterol 2013, 6, 287–290. [CrossRef]

- Koh, J; Go, H; Lee, WA; Jeon, YK. Benign Indolent CD56-positive NK-cell Lymphoproliferative Lesion Involving Gastrointestinal Tract in an Adolescent. Korean J Pathol 2014, 48, 73–76.

- Hong, M; Kim, WS; Ko, YH. Indolent CD56-positive Clonal T-cell Lymphproliferative Disease of the Stomach Mimicking Lymphomatoid Gastropathy. Korean J Pathol 2014, 48, 430–433.

- Takata, K; Noujima-Harada, M; Miyata-Takata, T; Ichimura, K; Sato, Y; Miyata, T; Naruse, K; Iwamoto, T; Tari, A; Masunari, T etal. Clinicopathologic Analysis of 6 Ly,phomatoid Gastropathy Cases. Expanding the Disease Spectrum to CD4-CD8- Cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2015, 39, 1259–1266.

- Hwang, SH; Park, JS; Jeong, SH; Yim, H. Indolent NK Cell Proliferative Lesion mimicking NK/T Cell Lymphoma in the Gallbladder. Hum Pathol Case Rep 2016, 5, 39–42. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R; Kariappa,S; Toon, C; Varikatt, W. NK-cell Enteropathy, a Potential Diagnostic Pitfall of Intestinal Lymphoproliferative Disease. Pathology 2019, 51, 338–340. [CrossRef]

- Xia, D; Morgan, EA; Berger, D; Pinkus, GS; Ferry, JA; Zukerberg, LR. NK-cell Enteropathy and Similar Indolent Lymphoproliferative Disorders. A Case Series with Literature Review. Am J Clin Pathol 2019, 151, 75–85. [CrossRef]

- Panigraphi, MK; Patra, S; Kumar, C; Kumar Nayak, H; Ayyanar, P; Bhat, SJ; Chouhan, MI; Samal, SC. Natural Killer Cell Enteropathy with Extraaintestinal Involvement: Presenting as Symptomatic Anemia. ACG Case Rep J 2021, 8, e00599. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W; Gupta, GK; Yao, J; Yang, YJ; Xi, L; Baik, J; Sigler, A; Kumar, A; Moskowitz, AJ; Arcila, ME et al. recurrent Somatic JAK3 mutations in NK-cell Enteropathy. Blood 2019, 134, 986–991. [CrossRef]

- Yi, H; Li, A; Ouyang, B; Da, Q; Dong, L; Liu, Y; Xu, H; Zhang, X; Zhang, W; Jin X etal. Clinicopathological and Molecular Features of Indolent Naturall Killer-Cell Lymphoproliferative Disorder of the Gastrointestinal Tract. Histopathology 2023, 82, 567–575. [CrossRef]

- Chuang, SS; Li, GD; Cheng, CL; Ng, SB; Huang, Y; Zhao, S; Yamaguchi, M; Zhao, WL; Kwong, YL. Lymphoma. In WHO Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours, 5th ed; Chan, J, Ed.; Lee Wood, B, Eds. IARC: Lyons, France, 2025; Available online: https://tumourclassification.iarc.who.int/chapters/63 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Bhagat, G; Naresh, KN; Dave, SS; Cerf-Benussan, N. Lymphoma. In WHO Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours, 5th ed; Chan, J, Washington, NK, Eds.; de Jong, D, Eds. IARC: Lyons, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, J; Bhagat, G; Chuang, SS; Naresh, KN; Dave, SS; Nakamura, N; Kato, S; Tan, SY. Lymphoma. In WHO Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours, 5th ed; de Jong, D, Ed.; Washington, NK, Eds. IARC: Lyons, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, CS. From the Midfacial Destructive Drama to the Unfolding EBV Story: A Short History of EBV-positive NK-cell and T-cell Lymphoproliferative Diseases. Pathology 2024, 56, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahemtullah, A; Longtine, JA; Harris, NL; Dorn, M; Zembowicz, A; Quintanilla-Fend, L; Preffer, FI; Ferry, JA. CD20+ T-cell Lymphoma. Clinicopathologic Analysis of 9 Cases and a Review of the Literature. Am J Surg Pathol 2008, 32, 1593–1607.

- Watabe, D; Kanno, H; Inoue-Narita, T; Onodera, H; Izumida, W; Kowata, S; Sawai, T; Akasaka, T. A Case of primary Cutaneous Natural Killer/T-cell Lymphoma, Nasal Type, with Indolent Clinical Course: Monoclonal Expansion of Epstein-Barr Virus Genome Correlating with the Terminal Aggressive Behaviour. Br J Haematol 2009, 160, 197–228. [CrossRef]

- Seishima, M; Yuge, M; Kosugi, H; Nagasaka, T. Extranodal NK/T-Cell lymphoma, Nasal Type, Possibly arising from Chronic Epstein-Barr Virus Infection. Acta Derm Venerol 2010, 90, 102–103. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q; Liu, S; Yang, Y; Tan,X; Peng, J; Xiong, Z; Li, Z. CD20-positive NK/T-cell Lymphoma with Indolent Clinical Course: Report of Case and Review of Literature. Diagn Pathol 2012, 7, 133. [CrossRef]

- Zuriel, D; Fink-Puches, R; Cerroni, L. A Case of Primary Cutaneous Extranodal Natural Killer/T-cell Lymphoma, Nasal Type, with a 22-Year Indolent Clinical Course. Am J Dermatopathol 2012, 34, 194–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabanelli, V; Valli, R; Zanelli, M; Righi, S; Gazzola, A; Mannu, C; Pileri, S; Sabattini, E. A Case of Sinonasal Extranodal NK/T-cell Lymphoma with Indolent Behaviour and Low-Grade Morphology. Case Rep Clin Med 2014, 3, 596–600.

- Zhang, QF; Hau, YN; Sun, LM; Tian, Y; Qiu, XS. Nasal Extranodal NK/T-cell Lymphoma Mimicking Inflammatory Polyps: a Case with Indolent Clinical Behavior. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2016, 9, 336–340.

- Devins, K; Schuster, SJ; Caponetti, GC; Bogusz, M. Rare Case of Low-Grade Extranodal NK/T-cell Lymphoma, Nasal Type, Arising in the Setting of Chronic Rhinosinusitis and Harboring a Novel N-Terminal KIT Mutation. Diagn Pathol 2018, 13, 92.

- Wang, Z; Gong, Q; Zhao, Y; Xu, H; Hu, S; Zhang, Z. Indolent EBV-positive T-cell Lymphoproliferative Disorder Arising in a Chronic Pericardial Hematoma: the T-cell Counterpart of Fibrin-associated Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma? Haematologica 2020, 105, e437. [CrossRef]

- Krishman, R; Ring, K; Williams, E; Portell, C; Jaffe, ES; Gru, AA. An Enteropathy-like Indolent NK-cell proliferation Presenting in the Female Genital Tract. Am J Surg Pathol 2020, 44, 561–565.

- Saglam, A; Singh, K; Gollapudi, S; Kumar, J; Brar, N; Butzmann, A; Warnke, R; Ohgami, RS. Indolent T-lymphoblastic Proliferation: A Systemic Review of the Literature Analyzing the Epidemiologic, Clinical, and Pathologic Features of 45 Cases. Int J Lab Hematol 2022, 44, 700=711.

- Ohgami, RS; Arber, DA; Zehnder, JL; Nathunam, Y; Warnke, R. Indolent T-lymphoblastic Proliferation (iT-LBP): a Review of Clinical and Pathologic Features and Distinction from Malignant T-lymphoblastic Lymphoma. Adv Anat Pathol 2013, 20, 137–140.

- Pizzi, M; Brignola, S; Righi, S; Algostinelli, C; Bertuzzi, C; Pillon, M; Semenzato, G; Rugge, M; Sabattini, E. Benign Tdt-positive Cells in Pediatric and Adult Lymph Nodes: a Potential Diagnostic Pitfall. Hum Pathol 2018, 81, 131–137.

- Goodlad, JR; Cerroni, L; Swerdlow, SH. Recent Advances in Cutaneous Lymphoma – Implications for Current and Future Classifications. Virchows Archiv 2023, 482, 281–298.

- Beltzung, F; Ortonne, N; Pelletier, L; Beylot-Berry, M; Ingen-Housz-Oro, S; Franck, F; Pereira, B; Godfraind, C; Delfau, M; D’Incan, M etal. Primary Cutaneous CD4+ Small/Medium T-cell Lymphoproliferative Disorders: a Clinical, Pathologic, and Molecular Study of 60 Cases Presenting with a Single Lesion: a Multicenter Study Group. Am J Surg Pathol 2020, 44, 862–872.

- Greenblatt, D; Ally, M; Child, F; Scarisbrick, L; Whittaker, S; Morris, S; Calonje, E; Petrella, T; Robson, A. Indolent CD8(+) Lymphoid Proliferation of Acral Sites: a Clinicopathologic Study of Six Patients with Some Atypical Features. J Cutan Pathol 2013, 40, 248–258.

- Vergier,B; Jansen, PM; Ortonne, N; Pulitzar, M; Williemze, T; Mitteldorf, C. Disorders. In WHO Classificarion of Haematolymphoid Tumours, 5th ed; Lazar, AJ, Coupland, SE, Eds.; Akkari, Y, Eds. IARC: Lyons, France, 2025; Available online: https://tumourclassification.iarc.who.int/chapters/63 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Kemp, W; Pulitzer, M; Robson, A; Mitteldorf, C. Primary Cutaneous Acral CD8-positive T-cell Lymphoproliferative Disorders. In: WHO Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours, 5th ed; Lazar, AJ; Coupland, SE; Akkar, Y, Eds. IARC, Lyons. France, 2025. Available online: https://tumourclassification.iarc.who.int/chapters/63 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Tamehiro, N; Nishida, K; Sugita, Y; Hayakawa, K; Oda, H; Nitta, T; Nakano, M; Nishioka, A; Yanobu-Takanashi, R; Goto, M etal. Ras Homolog Gene Family H (RhoH) Deficiency Induces Psoriasis-like Chronic Fermatitis by Promoting TH17 Cell Polarization. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019, 143, 1878–1891. [CrossRef]

- Crequer, A; Troeger, A; Patin, E; Ma, CS; Picard, C; Pederana, V; Fieschi, C; Lim, A; Abhyankar, A; Gineau, L etal. Human RHOH Deficiency Causes T Cell Defects and Susceptibility to EV-HPV Infection. J Clin Invest 2012, 122, 3239–3247. [CrossRef]

- Edison, N; Belhanes-Peled, H; Eitan, Y; Gutthmann, Y; Yeremenko, Y; Raffeld, M; Elmalah, I; Troughuboff, P. Indolent T-cell Lymphoproliferative Disease of the Gastrointestinal Tract after a Treatment with adaloimumab in Resistant Crohn’s Colitis. Hum Pathol 2016, 5, 45–50. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K; Wang, M; Zhang, R; Li, J. Detection of Epstein-Barr Virus Encoded RNA in Fixed Cells and Tissues using CRISPR/Cas-mediated R Cas FISH. Anal Biochem 2021, 625, 114211.

- Qi, Z; Han, X; Hu, J; Wang, G; Gao, J; Wang, X; Liang, D. Comparison of Three Methods for Detection of Epstein-Barr Virus in Hodgkin’s Lymphoma in Paraffin-Embedded Tissues. Mol Med Rep 2013, 7, 89–92. [CrossRef]

- Leenman, EE; Panzer-Grumayer, RE; Fischer, S; Leitch, HA; Horsman, DE; Lion, T; Gadner, H; Ambros, PF; Leston, VS. Rapid Determination of Epstein-Barr Virus Latent or Lytic Infection in Single Human Cells Using In situ Hybridization. Mod Pathol 2 0024, 17, 1564–1572. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y; Ling, S; Tang, D; yang, M; Shen, C. Advances in Epstein-Barr Virus Detection: From Traditional Methods to Modern Technologies. Viruses 2005, 17, 1026.

- Naresh, KN; Ferry, JA; Du, M. Introduction to B-cell Lymphproliferative Disorders and Neoplasms. In: WHO Classfication of Haematolymphoid Tumours, 5th ed. IARC: Lyons, France, 2025. Available online: https://tumourclassification.iarc.who.int/chapters/63 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

|

Series (reference, year) |

Sex | Age |

LPD Duration (years) |

Site(s) |

Disease progression |

Px of progressed disease |

Clinical outcome |

Histology of LPD |

Immunophenotype |

Geneotype | Lineage |

EBV/EBER of LPD |

Ki67 |

| Rahemtullah et al[54] (2008) |

M | 71 | 4 | neck LN |

EBV+ BCL with plasmacytic differentiation | CT | DOD (66 m) |

LG | CD2+, CD3+, CD5+, CD7+, CD4+, CD20+, CD30+(dim), CD56+(dim) |

TCR: GL Ig: polyclonal |

T | + (EBV clonal) |

NR |

| Watabe et al[55] (2009) |

F | 39 | 10 | skin (legs) |

ENNKTL, nasal type (skin) |

CT | DOD (128 m) |

LG* | CD3+, CD56+, GZB+, CD8+/-, perforin +/- |

TCR:GL | NK | + (LMP+) (EBV biclonal) |

NR |

| Seishima FM et al[56] (2010) |

F | 60 | 11.5 | skin (lip and cheek) |

EBV+ ENNKTL, nasal type (nose & multiple skin sites) |

CT | DOD (146m) |

LG* | CD56-, CD4+/-, CD8+/-, cytotoxic (ND) |

NR | NK (CD56 turned + on progression) |

NR | NR |

| Jiang QP et al [157] (2012) |

F | 78 | 10 | nose | NP | NA | AWD | LG | CD3+, CD56+, Cytotoxic+, CD20+ |

TCR:GL Ig : GL |

NK | + (EBV genome) |

60% |

| Zuriel D et al[58] (2012) |

F | 55 | 22 | skin (recurrent, right upper arm) |

NP | NA | AWD (recurrence 192 m & 264 m, skin right upper arm) | LG | CD2+, CD3+, cytotoxic+, CD56+ (at 264 m) Ki67 >90% |

TCR: GL | NK | + | 90% |

| Tabeanelli V et al[59] (2014) |

F | 52 | 13 | nose | NP | NA | AWD at 156 m |

LG | CD2+, CD3+, CD5+, CD7+, CD56+, βF1+, TCR α/δ+, cytotoxic+, Ki67 (moderately high) |

TCR: clonal | T | + | Moderate high |

| Zhang QF et al[60] (2016) |

M | 53 | 20 | nose | NR | NA | AWD at 242 m |

LG | CD3+, CD56+, cytotoxic+, Ki67(80%) |

NR | NK | + | 80% |

| Devins K et al[61] (2018) |

F | 71 | long standing | nose | NR | NA | AWD (many years) |

LG | CD2+, CD3+, CD3+/-, CD5+/-, CD7+/-, CD56- cytotoxic+, Ki67 (<1%) |

TCR: clonal KIT mutation+ |

T | + | <1% |

| Wang Z et al [62] (2020) | M | 64 | 19 | Pericardium | NP | NA | AW | LG | CD3+,CD30+,CD43+, TIA1+, MUM1+, BCL2+ |

TCR:clonal | T | + | >90% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).