1. Introduction

The integration of technology into language education has long served as a catalyst for methodological innovation and pedagogical transformation. From early audio-lingual systems to computer-assisted language learning (CALL) and mobile-assisted language learning (MALL), technological advancements have continuously reshaped how languages are taught and learned. In recent years, robot-assisted language learning (RALL) has gained increased popularity and visibility as a dynamic frontier in this evolution, leveraging physical, socially interactive agents to create immersive, responsive, and personalized learning environments. As educational robotics become increasingly sophisticated and accessible, RALL now represents a significant domain within the broader application of artificial intelligence (AI) and embodied technologies in education (Cheng et al., 2018).

Compared to traditional, often passive modes of language instruction, RALL offers real-time feedback, multimodal (verbal, gestural, visual) interaction, and adaptive scaffolding tailored to individual learners’ needs – features that have been shown to enhance language learning across diverse populations (Lee, 2022). By simulating human-like interaction, social robots can function as tutors, peers, or companions, fostering engagement and reducing anxiety, particularly among young learners and those with language difficulties. This shift toward interactive, learner-centered pedagogy positions RALL at the intersection of linguistics, cognitive science, educational psychology, and robotics.

The theoretical underpinnings of RALL are rooted in several well-established frameworks. The Sociocultural Theory (Vygotsky, 1978) emphasizes the role of social interaction in cognitive development, particularly through the concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). In this context, robots act as mediators, providing scaffolding that enables learners to achieve linguistic competence beyond what they could accomplish independently. Similarly, Constructivism (Bruner, 1996; Gogus, 2012) views language learning as an active, experiential process. Robots facilitate this by enabling hands-on, interactive language practice. The Multimodal Communication Theory (Kress & Leeuwen, 2001) further supports RALL by highlighting how meaning is constructed through multiple semiotic resources. Robots integrate speech, gesture, facial expression, and movement to enrich comprehension and expression, which can presumably enrich learners’ meaning-making resources with increased engagement and real-world relevance to support diverse learning styles. Finally, the Embodied Cognition Theory (Barsalou, 2010, 2020) suggests that language learning is not solely a mental process; rather, our understanding of language and concepts is grounded in the sensorimotor experience and interactions with the world. The physical interactions facilitated by robots would thus help learners internalize language through embodied sensorimotor experiences. These frameworks collectively demonstrate how the incorporation of social robots align with principles of interaction, personalization, multimodality and embodied cognition to support effective language acquisition.

RALL has been applied across age groups, including young children (Karakaş Kurt & Güneyli, 2023; Nasihati Gilani et al., 2018; Tong et al., 2017), K-12 students (Chen Hsieh, 2024; Sapounidis et al., 2024; Wang & Cheung, 2024), and adults (Deng et al., 2024; Iio et al., 2019), with a predominant focus on vocabulary acquisition and speaking skills in second language (L2) contexts. Studies often feature K-12 settings for English vocabulary learning involving small sample sizes and short-term interventions, and benefits appear to generalize to L2 learning in adults (Deng et al., 2024).

A variety of robots assist language learning in different dimensions. Hybrid systems combine robots to maximize functionality and address language education gaps in regions with teacher shortages (Engwall & Lopes, 2022; Sin et al., 2022). Sin et al. (2022) developed a modular multi-robot system where a NAO acted as a teacher and Zenbo Junior robots as assistants, enabling English instruction without human teachers and illustrating scalability for resource-limited settings. Moreover, empirical studies highlight that RALL enhances grammar (Herberg et al., 2015; Hyun et al., 2008), vocabulary (van den Berghe et al., 2019, 2021), speaking (Alimardani et al., 2023; Kennedy et al., 2016), with comparable benefits observed in individuals with aphasia (Linden et al., 2023). Additionally, RALL also improves learner motivation and engagement (Derakhshan et al., 2024; van den Berghe et al., 2019; Zhexenova et al., 2020), a well-established driver of Second language acquisition (SLA) success (Dörnyei, 1998, 2014). It is notable that meta-analytic findings confirm RALL’s capacity to foster the affective factors via interactive, personalized experiences that yielded measurable gains in vocabulary, reading, and grammar (van den Berghe et al., 2019). Furthermore, robots further enable sophisticated behavioral monitoring and adaptive feedback (Chiang & Chen, 2023; Najima et al., 2021). Chiang & Chen (2023) used lag sequential analysis to confirm the effectiveness of scaffolded learning.

Despite these notable benefits, RALL faces several challenges. Limitations in speech recognition and natural language processing (NLP) hinder accurate understanding of non-native, accented, or child-directed speech, often leading to interaction breakdowns (Veivo & Mutta, 2022). Additionally, robots may also fail to grasp pragmatic language use, including cultural conventions, idioms or sarcasm, and scripted interactions limit spontaneity, critical thinking, and creativity. Moreover, many implementations prioritize technological feasibility over pedagogical depth, resulting in a disconnect between innovation and theoretical grounding. Addressing these challenges requires evidence-based synthesis of existing problems and collaborative efforts to design more adaptive and context-aware robotic systems.

As the field rapidly evolves, fueled by advancements in AI, large language models (LLMs), virtual reality (VR), and the Internet of Things (IoT), there is an urgent need for a comprehensive, evidence-based synthesis of RALL research. While systematic reviews and meta-analyses have examined specific outcomes (e.g., efficacy, motivation), a bibliometric analysis offers a macro-level perspective, mapping the intellectual structure, thematic evolution, and global research landscape of the field. Such an analysis is still missing, which can reveal dominant trends, identify knowledge gaps, expose theoretical imbalances, and highlight understudied populations.

This study addresses this gap by conducting a bibliometric review and visualization analysis of RALL research from 2003 to July 12, 2025. Using data from Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, and Dimensions, we analyze publication trends, keyword co-occurrence, and thematic evolution to answer five key questions: (1) What are the growth trend and citation patterns of articles in RALL research? (2) Who are the most productive and influential (based on citation) authors? (3) Which countries, institutions, and journals dominate the field? (4) What are the core research themes and keyword clusters? (5) How has the thematic focus of RALL evolved over time? By synthesizing two decades of research, this study aims to (1) provide a state-of-the-art overview of RALL, (2) identify critical gaps and opportunities for innovation, and (3) issue a call to action for researchers to develop theory-driven, equitable, and scalable RALL systems that bridge technological potential with pedagogical rigor.

2. Methods

This bibliometric review was conducted following the systematic framework proposed by Donthu et al. (2021) and updated guidelines by Öztürk et al. (2024) to ensure methodological rigor, reproducibility, and comprehensive coverage of RALL research domain. We employed a dual approach by conducting descriptive (performance) analysis (total publications, author contribution, and citation-related indicators) and science mapping (structural) analysis (co-occurrence of keywords analysis, thematic evolution) to provide a holistic understanding of the intellectual, social, and conceptual structure of RALL research from its inception to the present stage.

2.1. Search Strategy

To ensure broad and representative coverage of the RALL literature, a systematic search was conducted across four major academic databases: Web of Science (WoS), Scopus, PubMed, and Dimensions with records published up to July 12, 2025. These platforms were selected due to their extensive indexing of peer-reviewed journals, conference proceedings, and interdisciplinary research in education, linguistics, robotics, and AI. The search used the Boolean string: (((“robot” OR “robotics”) AND (“language learning” OR “speech training” OR “language education” OR “pronunciation training”))), adapted to the syntax requirements of each database. To ensure relevance, only journal articles, conference papers, review articles, pre-access, and editorial material were included; letters, notes, books, meeting abstracts, retracted articles, and non-English publications were excluded from further analysis. Initial searches yielded 928 records from WoS and Scopus, 891 from PubMed, and 390 from Dimensions. All datasets were merged into a single master using R (version 4.4.2) for subsequent processing and de-duplication (Lim et al., 2024).

2.2. Screening and Selection Process

A multi-stage screening protocol was implemented to ensure data quality and relevance. Duplicate records were identified and removed using a three-step process. First, entries were matched by DOI, the primary unique identifier. Second, for records without DOIs, title matching and publication year comparison were performed. Third, a final manual verification was conducted in Excel to resolve ambiguous cases (Lim et al., 2024).

After deduplication, two authors (Y. Zou and X. Z.) independently screened the remaining records based on title, abstract, and full-text availability. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion with their supervisor (B.C.). The inclusion criteria were specified as follows:

Empirical or theoretical studies involving robots in language learning contexts.

Focus on second/foreign language learners or individuals with language disorders (e.g., aphasia, autism).

Document types: journal articles, conference papers, reviews, pre-access, editorials.

Published in English.

And the exclusion criteria included:

Retracted articles.

Non-research documents (e.g., letters, book chapters, corrections, meeting abstracts).

Studies where robots were used for non-linguistic purposes (e.g., math tutoring, social skills without language focus).

Insufficient information for eligibility assessment.

This process resulted in a final dataset of 439 publications included in the analysis.

Figure 1.

PRISMA-style flow diagram of study selection.

Figure 1.

PRISMA-style flow diagram of study selection.

2.3. Data Extraction

Our extraction of the bibliometric information of each article included the following details: authors, affiliations, article title, document type, journal name/conference names, abstract, authors keywords, times cited, and cited references. All data were manually verified and corrected where necessary to ensure accuracy. In cases where author keywords were missing, key terms were extracted from the title, abstract, or full text to support keyword co-occurrence analysis (Donthu et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2019).

2.4. Data Analysis

The analysis was conducted in two complementary phases: descriptive (performance) analysis and science mapping (visualization) analysis (Donthu et al., 2021). Using the Bibliometrix R package (version 4.2) (Aria & Cuccurullo, 2017), we conducted performance analysis to examine:

Annual publication trends and growth rate

Most cited and productive authors

Leading countries

Top publishing and citing journals/conferences

Average citations per document and document age

We used local citations (citations from other documents within our dataset) as an indicator of influence within the RALL research community.

To uncover the intellectual structure and thematic evolution of the field, we employed Keyword Co-occurrence Analysis using VOSviewer (version 1.6.20) (van Eck & Waltman, 2010) and Thematic Evolution Analysis using Biblioshiny.

In the co-occurrence analysis, only author-provided keywords were used. Terms appearing at least five times were included to ensure statistical robustness. A thesaurus file was created to unify synonymous or variant terms (e.g., “robot-assisted language learning” was merged under “RALL”; “robots” and “robotics” → “robot”). Clusters were generated using the modularity-based clustering algorithm in VOSviewer, with visualization based on co-occurrence strength and network density.

For thematic evolution, Biblioshiny was used to map how research topics have shifted over time. The timeline was divided into four phases based on publication volume and technological milestones: (1) 2003–2009: Foundational period, (2) 2010–2018: Expansion and diversification, (3) 2019–2022: Integration of AI and VR. And (4) 2023–2025: Specialization and learner-centered design. This allowed us to trace the emergence, decline, and transformation of key themes such as human-robot interaction, artificial intelligence, and clinical applications.

3. Results

Based on the above bibliometric analysis, we report the results in this section following the guidelines proposed by Lim & Kumar (2024). The earliest article meeting the inclusion criteria was published in 2003, and the literature search with updating from the databases extended the latest date up to July 12, 2025. The annual growth rate was 17.39%, the average age of documents was 5.01 years, and mean citations per document reached 12.49. 17.08% of the documents involved international collaboration. The performance and structural analysis results provide a comprehensive overview of the field’s growth, intellectual structure, and evolving thematic priorities.

3.1. Descriptive Results

Our study involves identifying and evaluating publications through a detailed descriptive analysis, focusing on the annual publication growth rate, mean citations per publication and collaboration. Descriptive analyses were performed using Biblioshiny to ensure robust sensitivity testing.

3.1.1. Publication Trends Over Time

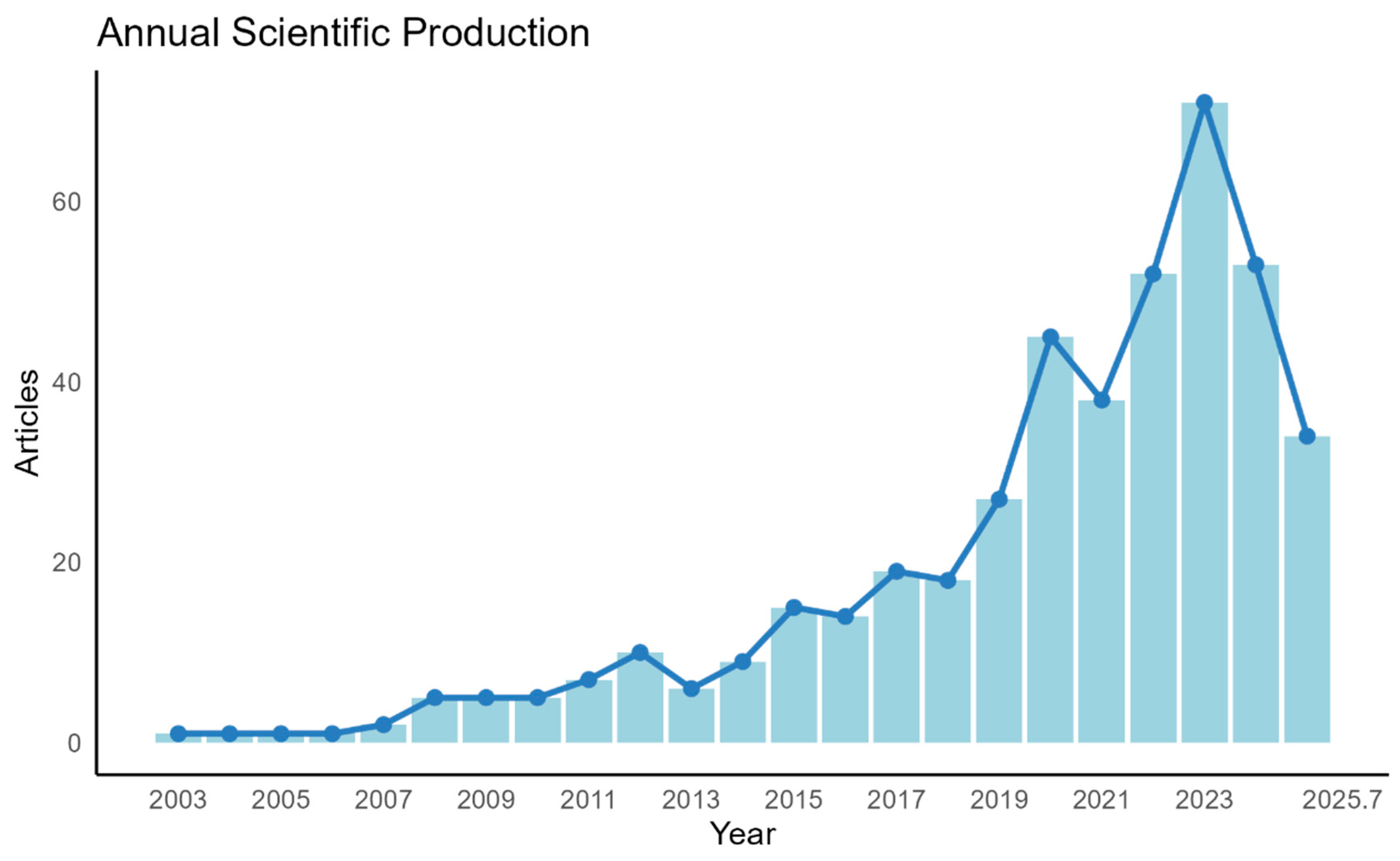

As illustrated in

Figure 2, RALL research has grown steadily since its inception in 2003, reflecting increasing scholarly interest in the intersection of robotics and language education. The number of annual publications rose gradually from 2003 to 2019, with a marked acceleration between 2020 and 2023. Output peaked in 2023 with 71 publications, representing a significant milestone in the field’s development. However, a notable decline occurred in 2024, with 53 publications, suggesting a shift from rapid expansion to a phase of consolidation and refinement.

3.1.2. Most Cited Articles

Citation analysis reveals the foundational works that have shaped the RALL field. As shown in

Table 1, the most cited article is “Social Robots for Language Learning: A Review” by Rianne van den Berghe, published in

Review of Educational Research. This article has received 75 local citations and 205 global citations, making it the most impactful work in the field. This seminal review synthesized evidence on the effectiveness of social robots in language learning across age groups and contexts, establishing a benchmark for empirical and theoretical rigor. It is followed closely by “On the effectiveness of Robot-Assisted Language Learning”, published in

ReCALL by Sungjin Lee et al. This early study reported that interactive robots enhanced elementary students’ speaking skills, motivation, confidence, and interest in language learning, despite no significant gains in listening. These two articles stand out as foundational contributions to RALL research.

3.1.3. Most Productive and Influential Authors

Among 1,119 authors, Chen N. emerges as the most productive scholar with 20 publications, followed by Sandygulova A. (16) and DE H M. (13) as shown in

Table 2. These researchers have contributed extensively to the design, implementation, and evaluation of RALL systems, particularly in K–12 and EFL contexts.

In terms of citation impact, VAN D B R is the most influential author with 120 local citations, reflecting her pivotal role in synthesizing and advancing the field. She is closely followed by Oudgenoeg-Paz O. and Verhagen J., each with 115 local citations, both of whom have focused on cognitive and developmental aspects of child-robot interaction.

3.1.4. Most Productive and Influential Countries

Table 3 presents the top 10 most productive countries in the RALL field according to the corresponding authors and most cited countries. Among these, China leads in terms of publication output (80), followed by Netherland (27), the USA (27), and Japan (24). Chinese research is often institutionally supported and focused on K–12 English education, reflecting national priorities in multilingualism and technological integration.

In terms of citation impact, China ranks first (946 local citations), followed by the Netherlands (924), and the USA (709). Despite lower output, Dutch research exerts disproportionate influence, largely due to the L2TOR project, a multi-institutional, EU-funded initiative that has produced high-impact studies on social robots in early language learning.

3.1.5. Most Productive and Influential Journals and Conferences

Table 4 presents the most productive and most cited sources. The journals,

Computer Assisted Language Learning and

Frontiers in Robotics and AI, each published 11 RALL-related articles between 2003 and 2025. In terms of citation impact, the

ACMIEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction ranks first among locally cited sources with 413 citations, followed by the

International Journal of Social Robotics (263) and

Computers & Education (220). These journals and conferences reflect the interdisciplinary nature of RALL, bridging education, linguistics, computer science, and robotics.

3.2. Scientific Mapping Analysis

Scientific mapping involves visualizing, analyzing, and modeling scientific and technical activities to uncover patterns and trends within a research domain. In this section, we examine the frequency of authors keyword usage in research articles using VOSviewer for network visualization. In addition, we conducted thematic evolution analysis through Biblioshiny to demonstrate the developmental trends.

3.2.1. Keywords Co-Occurrence Analysis

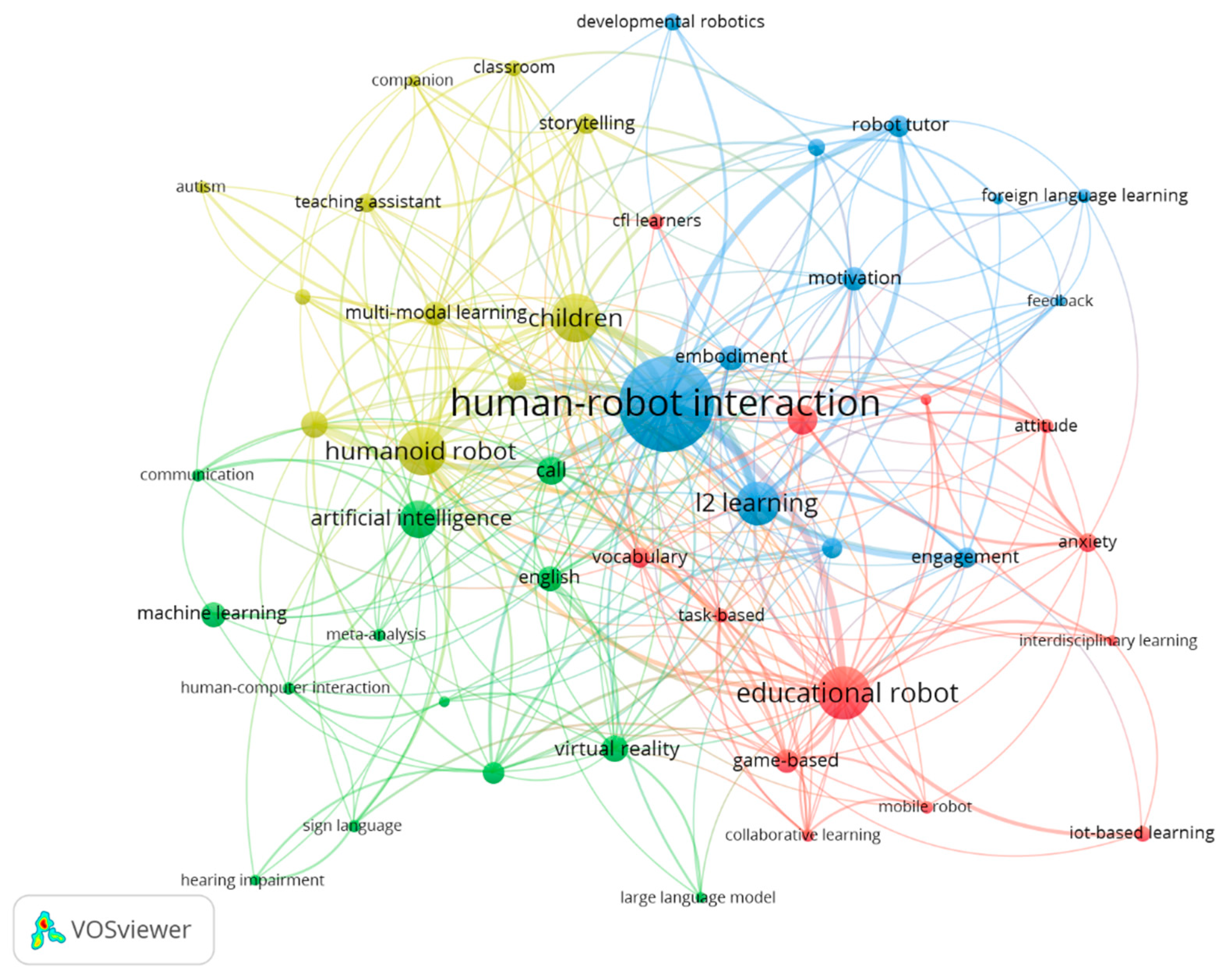

A keyword co-occurrence network was generated from author-provided keywords, filtered to include terms appearing at least 5 times. After merging synonyms, 59 keywords were analyzed, resulting in a network of 49 nodes after removing overly broad terms (e.g., “robot,” “language”). The analysis identified four distinct thematic clusters, visualized in

Figure 3 and summarized in

Table 5 using VOSviewer’s modularity-based clustering algorithm.

Cluster 1: Pedagogical Design and Learner Experience (Red)

Centered on “educational robot”, this cluster emphasizes instructional methodologies such as “game-based,” “task-based,” “IoT-based learning”, and “collaborative learning.” Keywords like “anxiety,” “attitude,” and “motivation” highlight the affective dimension of language learning. The presence of “EFL learners” and “CFL learners” indicates a strong focus on English and Chinese as foreign languages. This cluster reflects a learner-centered, constructivist approach to RALL.

Cluster 2: Technological Infrastructure and AI Integration (Green)

Anchored by “artificial intelligence”, this cluster includes machine learning, “virtual reality,” “CALL”, “augmented reality,” “speech training,” and “large language models.” The integration of “virtual reality” and “computational thinking” signals a shift toward immersive, data-driven, and adaptive systems. Keywords like “hearing impairment” and “sign language” point to inclusive applications in special education.

Cluster 3: Human-Robot Interaction and Cognitive Engagement (Blue)

The dominant keyword for this cluster is “human-robot interaction”. This cluster integrates “L2 learning,” “embodiment,” “engagement,” “motivation,” and “feedback.” The presence of “robot tutor,” “telepresence robot,” and “distance learning” underscores the social and relational role of robots. This cluster aligns with sociocultural and embodied cognition theories, emphasizing interaction as a driver of language acquisition.

Cluster 4: Learner Demographics and Contextual Applications (Yellow)

Cluster 4 addresses learner-centered and contextual elements of RALL. Centered on “children” and “humanoid robot”, this cluster highlights the developmental focus of RALL. Keywords such as “storytelling,” “conversation,” “classroom,” and “teaching assistant” reflect the use of robots in early childhood and K–12 education. The inclusion of “autism” and “companion” suggests growing interest in therapeutic and emotional support roles, though still limited in scope.

3.2.2. Thematic Evolution Analysis

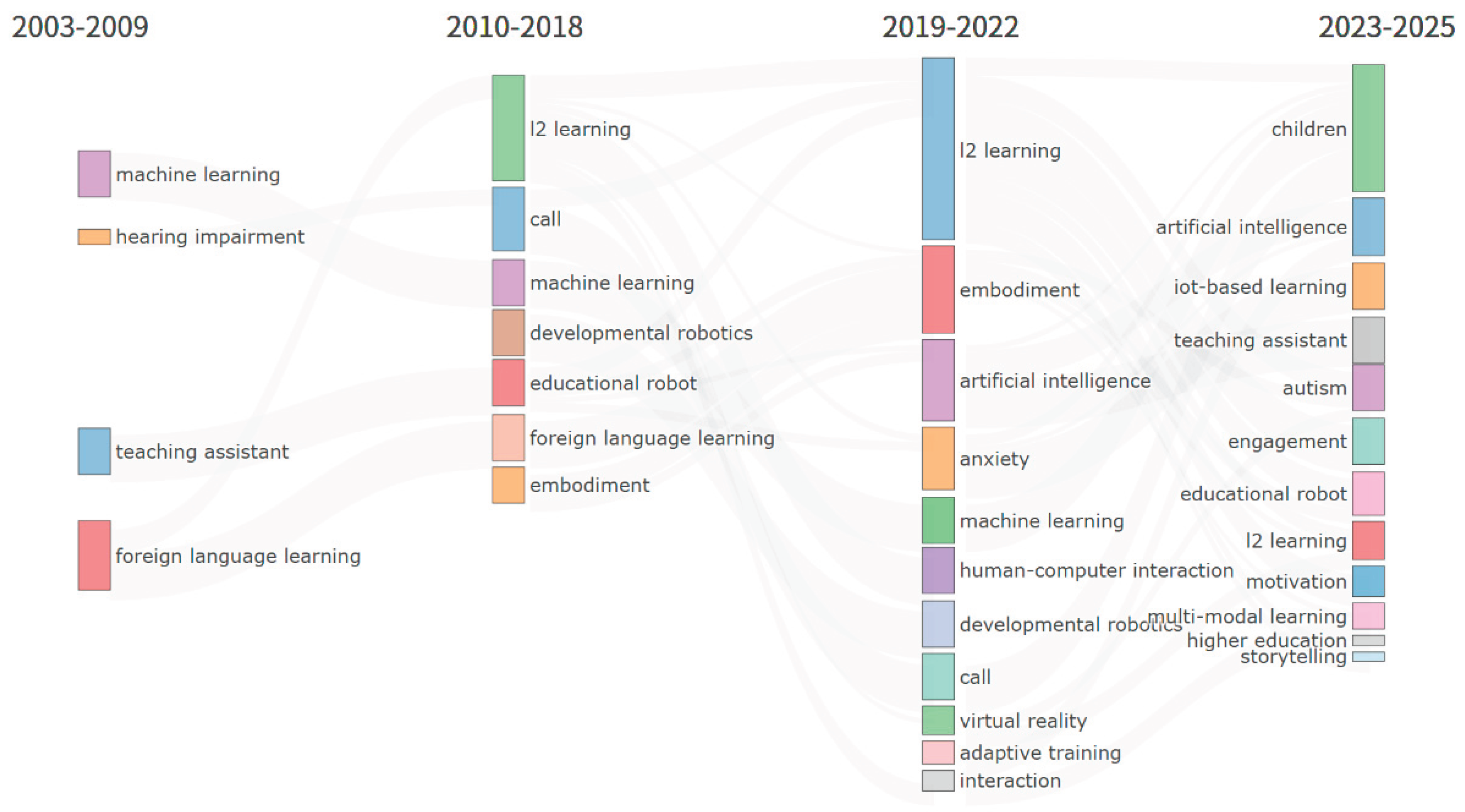

The thematic evolution of RALL over the past two decades, as depicted in

Figure 4, reveals a dynamic progression from foundational explorations to increasingly sophisticated and specialized application, driven by technological advancements and evolving educational needs. The timeline is segmented into four distinct periods: 2003–2009, 2010–2018, 2019–2022, 2022–12 July 2025.

In the initial phase, RALL focused on foundational themes such as “language learning” and “teaching assistant,” exploring robots as tools to enhance language learning. “Machine learning” emerged as a core theme, indicating an early interest in leveraging AI technique to adapt robotic system. Between 2008 and 2018, the scope broadened to emphasize “L2 learning,” with keywords like “CALL,” “developmental robotics,” “embodiment” and “educational robot” highlight the increasing attention language learning. “Machine learning” persisted as a key enabler of adaptive robotic behaviors. From 2019 to 2022, researches shifted toward AI-driven personalization and psychological engagement, integrating “artificial intelligence,” “virtual reality” and “human-computer interaction” for immersive, individualized learning. Keywords such as “anxiety” and “embodiment” signaled attention to affective and cognitive dimensions. The last phase (2023-2025.07) reflects diversification toward specialized populations (e.g. children, autism) and adoption of IoT-based and multimodal systems, along side “storytelling-based pedagogy.” This phase underscores scalability, equity and other ethical considerations in AI-driven robots and hybrid learning approaches.

4. Discussion

This bibliometric analysis provides the first comprehensive mapping of the intellectual, thematic, and institutional landscape of Robot-Assisted Language Learning (RALL) from 2003 to July 12, 2025. Drawing on 439 publications across four major databases, our study synthesizes two decades of research to trace the evolution of RALL from an experimental educational tool into a multidisciplinary field at the intersection of AI, robotics, cognitive science, and language pedagogy. The results reveal a field experiencing robust growth, marked by technological innovation and increasing learner-centered design, yet constrained by a persistent gap between technological capability and theoretical grounding. This discussion interprets the findings through three interconnected lenses: (1) publication trends and global research dynamics, (2) thematic evolution and conceptual structure, (3) challenges and future directions, culminating in a call to action for the next phase of RALL research, and (4) limitations of this study.

4.1. Global Research Dynamics: Productivity, Influence, and Collaboration

The publication trend analysis reveals a clear upward trajectory in RALL research, with a peak of 71 publications in 2023 followed by a decline to 53 in 2024. This pattern likely reflects a post-pandemic research surge, as institutions accelerated projects initiated during the shift to remote and hybrid learning. The integration of LLMs, VR, and IoT-based systems around this period created fertile ground for innovation, enabling more adaptive, immersive, and scalable robotic applications.

Geographically, China leads in publication output (80 articles), signaling strong national investment in educational technology and foreign language education. The United States is also a key player in both productivity and citation impact, reflecting its leadership in AI, robotics, and educational innovation. However, the Netherlands exerts disproportionate scholarly influence, with its research generating 924 local citations, second only to China but achieved with less than half the output. This influence is largely attributable to the L2TOR project, a landmark EU-funded initiative that established a robust framework for social robots in early second language acquisition, generating high-impact studies on interactive, engagement-driven learning environments (Belpaeme, Kennedy, et al., 2018; Kanero et al., 2018; van den Berghe et al., 2019; Vogt et al., 2019). Thus, despite the dominance of China and the USA in the quantity of publications, the scholars in the Netherlands have made a distinctive impact by producing work that significantly shapes the global research agenda on RALL, especially the discourse around the pedagogical role of robots in language acquisition.

It is worth noting that international collaboration remains limited (17.08%), suggesting fragmented research communities and missed opportunities for cross-cultural validation of RALL systems. Future efforts should prioritize global research networks to ensure that RALL solutions are culturally responsive, linguistically diverse, and equitably accessible.

4.2. Thematic Evolution: From Technological Experimentation to Learner-Centered Integration

The field of RALL has evolved from early experiments with robots as novelties to multidisciplinary domain grounded in pedagogical innovation and socio-cognitive theory. Our keyword co-occurrence and thematic evolution analyses reveal a four-cluster conceptual structure that maps the core dimensions of RALL:

Pedagogical Design and Instructional Methodologies (e.g., game-based learning, task-based, EFL/CFL learners)

AI-Driven Technological Infrastructure (e.g., artificial intelligence, VR, LLMs, machine learning)

Human-Robot Interaction and Cognitive Engagement (e.g., embodiment, motivation, feedback, L2 learning)

Learner Contexts and Developmental Applications (e.g., children, humanoid robot, storytelling, autism)

These clusters reflect a maturation of the field: from robots as “teaching assistants” to socially responsive agents embedded in complex learning ecosystems. The prominence of “human-robot interaction” and “embodiment” underscores a growing recognition of the socio-cognitive and affective factors, aligning with Sociocultural Theory (Vygotsky, 1978) and Embodied Cognition (Barsalou, 2010). However, while technological innovation has accelerated, the integration of SLA theory into robot design remains inconsistent, creating a critical gap between capability and pedagogical efficacy.

Educational Robots as Theoretically Grounded Scaffolding Agents

Educational robots’ true potential lies in their capacity to operationalize foundational SLA theories. When designed with constructivist and sociocultural principles, robots can scaffold learners through their ZPD (Vygotsky, 1978). Chen & Chang (2009) pioneered a task-based language teaching (TBLT) model integrated with robotic assistance, creating a role-playing game where students interacted with a robot to complete communicative tasks. This approach not only increased engagement but also reduced anxiety and boredom—two well-documented affective filters in language learning (Krashen, 1982). More recently, Cheng et al. (2024) advanced this model by developing an innovative R & T (Robot and Tangible objects) system combining humanoid robots with IoT-based physical objects to create immersive, game-based language environments, yielding a 16% vocabulary gain and fewer learning obstacles, consistent with Embodied Cognition Theory (Barsalou, 2010), which posits that sensorimotor experiences deepen linguistic understanding. The success of the R&T system illustrates how physical interaction with objects, mediated by a robot, can make abstract language concepts concrete and memorable.

Technological Integration: AI, VR, and the Future of Immersive Learning

The second cluster reflects technological advancements in AI education (Chen et al., 2022; Jaleniauskienė et al., 2023), CALL integration (Banaeian & Gilanlioglu, 2021; Khalifa et al., 2016), and VR implementation (Bottega et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2022), addressing long-standing challenges in language education, such as limited exposure to authentic contexts and insufficient opportunities for interactive practice. Chen et al. (2022) integrated VR with a physical robot in an English tour guide training program, where VR provided contextual immersion and the robot offered real-time conversation, improving speaking and vocabulary while managing cognitive load. These trends point toward increasingly adaptive and engaging environments, though they require AI model trained on diverse learner data (e.g., child speech, accented language) to avoid interaction breakdowns (Veivo & Mutta, 2022).

Human-Robot Interaction: Embodiment, Motivation, and Social Scaffolding

The prominence of “human-robot interaction” as the most central keyword cluster underscores language’s social nature. This aligns with Sociocultural Theory, which emphasizes learning through social mediation (Vygotsky, 1978). Projects like L2TOR, which was designed to support preschool children in learning a second language through interactions with a peer tutor social robot, responding to gaze, gesture, and speech to replicate human tutoring dynamics (Belpaeme, Vogt, et al., 2018). This project not only demonstrated the feasibility of robot tutors but also set a high standard for pedagogically informed robot design. Telepresence robots and research on distance learning (Jakonen & Jauni, 2024) further extends such benefits to remote contexts, providing physical presence and interaction opportunities where resources are scarce.

Children and Clinical Populations: Toward Inclusive and Specialized Applications

Children are the dominant demographic in RALL research, with “children” and “humanoid robot” forming a central cluster. This focus is justified by the robot’s ability to create playful, emotionally supportive environments that resonate with young learners. Chiang & Chen (2023) found multimodal scaffolding (speech, gestures, and visual cues) more effective than unimodal instruction, supporting multimodal communication theory (Kress & Leeuwen, 2001). For learners with special needs, the potential is even more profound. Alemi et al. (2015) demonstrated NAO’s effectiveness in teaching English to children with autism, offering predictability, reduced anxiety, and consistent feedback. Despite potential for therapeutic contexts such as aphasia rehabilitation (Linden et al., 2023), clinical applications remain underexplored, with minimal representation in the literature.

From Technological Affordances to Theoretically Grounded Design

RALL’s evolution toward technology-integrated, learner-centered environments, such as VR-robot hybrids (Chen et al., 2022) and IoT-based tangible systems (Cheng et al., 2024), enhances engagement and supports cognitive load management. However, much of this diversification stems from technological possibilities rather than pedagogical priorities. Foundational frameworks like Constructivism and Scaffolding theory are seldom operationalized in robot design or empirically evaluated, as reflected by the absence of “ZPD,” “scaffolding,” or “constructivism” in keywords analysis.

This gap is further evident in the short-term, small-sample nature of most RALL interventions, limiting insights into long-term language gains and real-world transfers. Advancing the field requires integrating SLA theory into robot design, developing adaptive frameworks responsive to learners’ cognitive and emotional states, and standardizing evaluation of both linguistic and social-emotional outcomes. Such systematic integration would align robotic capabilities with established pedagogical paradigms, ensuring innovation serves core educational objectives.

4.3. Challenges and Future Directions: Toward a More Equitable and Inclusive RALL

Despite its promise, RALL faces significant technical, pedagogical and ethical obstacles that constrain implementation across diverse educational contexts. First, speech recognition and NLP limitations hinder accurate understanding of child-directed speech, accented language, and developmental variations, causing interaction breakdowns and disengagement, especially among vulnerable populations. Second, over-reliance on humanoid robots and pre-programmed scripts further limits spontaneity and creativity, as robots lack sensitivity to pragmatic, cultural, and emotional nuances critical for authentic communication. Third, equity and accessibility remain major concerns due to high costs and infrastructure demands, restricting access to well-resourced institutions, leaving low-income and rural communities behind. Hybrid systems (e.g., telepresence robots) and modular designs (Sin et al., 2022) offer promising pathways to scalability, but widespread adoption requires policy support and open-source innovation.

The future trajectory of RALL research demonstrates promising developments as the educational market is expected to expand (Hardman & Co. (n.d.), 2021). First, establishing optimal integration between robotic assistance and authentic human communication represents a critical research priority. Additionally, material enrichment must be systematically assessed, and longitudinal studies are needed to evaluate the sustained benefits of robot-mediated instruction versus human-centered approach. Most strikingly, clinical applications remain underdeveloped, with limited work on language rehabilitation for aphasia (Linden et al., 2023) and support for children with autism (Alemi et al., 2015). This gap represents a missed opportunity to leverage robotics for inclusive, therapeutic education.

4.4. A Call to Action: Bridging the Gap Between Innovation and Impact

The future of RALL depends on bridging the divide between technological possibility and pedagogical purpose. To this end, we issue a five-point call to action for the research community:

- (1)

Develop Theory-Driven Robot Design: Integrate established SLA and cognitive theories (e.g., ZPD, scaffolding, multimodal learning) into the architecture of robotic systems, ensuring that interactions are not just engaging but cognitively and linguistically meaningful.

- (2)

Conduct Longitudinal and Comparative Studies: Move beyond short-term interventions to assess long-term language retention, skill transfer, and socio-emotional outcomes. Compare RALL with human instruction and other digital tools (e.g., AI chatbots, VR-only systems) to establish its unique value.

- (3)

Expand to Clinical and Special Education Contexts: Prioritize research on RALL for individuals with aphasia, autism, developmental language disorders, and hearing impairments, in collaboration with speech-language pathologists and special educators.

- (4)

Enhance Equity and Global Relevance: Design low-cost, adaptable systems for low-resource settings. Ensure multilingual and multicultural adaptability to avoid technological colonialism and promote inclusive innovation.

- (5)

Establish Ethical and Evaluation Frameworks: Develop standardized metrics for assessing RALL effectiveness, including learner autonomy, social interaction quality, and emotional well-being. Address risks of over-reliance and ensure human oversight in educational robotics.

4.5. Limitations of This Study

Our bibliometric study has several limitations that warrant further consideration. First, our search was limited to English-language peer-reviewed articles excluded dissertations, non-peer-reviewed works, and publications in other languages, limiting global coverage. Second, we did not compare RALL with other educational technologies such as AI or VR, which could clarify RALL’s unique contributions and foster cross-disciplinary collaboration. Third, interactions with broader priorities (STEM integration, multilingualism, and digital literacy) remain underexplored. Additionally, equity concerns persist regarding diversity, affordability, and accessibility, especially in less advanced regions. Finally, while large nations like China and the USA dominate output, examining smaller countries contribution and cross-border collaborations could reveal how diverse contexts, despite disparities, advance RALL innovation and promote inclusive global adoption.

5. Conclusions

This study provided a comprehensive bibliometric analysis of 439 RALL studies from WoS, Scopus, Dimension, and PubMed databases, mapping publication trends, research hotspots, and thematic evolution. Four primary themes have been identified: “educational robot,” “artificial intelligence,” “human-robot interaction,” and “children.” The RALL field has progresses from fundamental and exploratory language learning to more sophisticated and technology-integrated (e.g. VR, LLMs, and IoT etc.), and learner-centered approaches targeting diverse populations. Our study confirms that RALL has evolved from a niche technological curiosity into a vibrant, interdisciplinary field with transformative potential. However, development has been technology-driven rather than pedagogy-centers. To fulfill its promise, RALL must prioritize educational equity, cognitive depth, and human connection through theory-informed design, robust frameworks, and longitudinal research on learning outcomes and cognitive impacts.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by grants from the National Social Science Fund of China (22BYY160, 24CYY096). Zhang received additional support from the Brain Imaging Grant and Grant-in-aid, University of Minnesota.

Conflicts of Interest

We declared that there exist no potential interest conflicts in the current research.

References

- Alemi, M., Meghdari, A., Basiri, N. M., & Taheri, A. (2015). The Effect of Applying Humanoid Robots as Teacher Assistants to Help Iranian Autistic Pupils Learn English as a Foreign Language. In A. Tapus, E. André, J.-C. Martin, F. Ferland, & M. Ammi (Eds.), Social Robotics (Vol. 9388, pp. 1–10). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Alimardani, M., Duret, J., Jouen, A.-L., & Hiraki, K. (2023). Social robots as effective language tutors for children: Empirical evidence from neuroscience. Frontiers in Neurorobotics, 17, 1260999. [CrossRef]

- Aria, M., & Cuccurullo, C. (2017). bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. Journal of Informetrics, 11(4), 959–975. [CrossRef]

- Banaeian, H., & Gilanlioglu, I. (2021). Influence of the NAO robot as a teaching assistant on university students’ vocabulary learning and attitudes. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 71–87. [CrossRef]

- Barsalou, L. W. (2010). Grounded Cognition: Past, Present, and Future. Topics in Cognitive Science, 2(4), 716–724. [CrossRef]

- Barsalou, L. W. (2020). Challenges and Opportunities for Grounding Cognition. Journal of Cognition, 3(1), 31. [CrossRef]

- Belpaeme, T., Kennedy, J., Ramachandran, A., Scassellati, B., & Tanaka, F. (2018). Social robots for education: A review. Science Robotics, 3(21), eaat5954. [CrossRef]

- Belpaeme, T., Vogt, P., van den Berghe, R., Bergmann, K., Göksun, T., de Haas, M., Kanero, J., Kennedy, J., Küntay, A. C., Oudgenoeg-Paz, O., Papadopoulos, F., Schodde, T., Verhagen, J., Wallbridge, C. D., Willemsen, B., de Wit, J., Geçkin, V., Hoffmann, L., Kopp, S., … Pandey, A. K. (2018). Guidelines for Designing Social Robots as Second Language Tutors. International Journal of Social Robotics, 10(3), 325–341. [CrossRef]

- Bottega, J. A., Kich, V. A., Jesus, J. C. de, Steinmetz, R., Kolling, A. H., Grando, R. B., Guerra, R. da S., & Gamarra, D. F. T. (2023). Jubileo: An Immersive Simulation Framework for Social Robot Design. Journal of Intelligent & Robotic Systems, 109(4), 91. [CrossRef]

- Bruner, J. (1996). The Culture of Education. Harvard University Press. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.-D., & Chang, C.-W. (2009). A Task-Based Role-Playing Game with Educational Robots for Learning Language. In M. Chang, R. Kuo, Kinshuk, G.-D. Chen, & M. Hirose (Eds.), Lecture Notes in Computer Science (4 📊; pp. 483–488). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Chen Hsieh, J. (2024). Multimodal Digital Storytelling Presentations among Middle-School Learners of English as a Foreign Language: Emotions, Grit and Perceptions. RELC Journal, 55(2), 547–558. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-L., Hsu, C.-C., Lin, C.-Y., & Hsu, H.-H. (2022). Robot-Assisted Language Learning: Integrating Artificial Intelligence and Virtual Reality into English Tour Guide Practice. Education Sciences, 12(7), 437. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.-W., Sun, P.-C., & Chen, N.-S. (2018). The essential applications of educational robot: Requirement analysis from the perspectives of experts, researchers and instructors. Computers & Education, 126, 399–416. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.-W., Wang, Y., Cheng, Y.-J., & Chen, N.-S. (2024). The impact of learning support facilitated by a robot and IoT-based tangible objects on children’s game-based language learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 37(7), 2142–2173. [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y. V., & Chen, N.-S. (2023). A Learner Behavioral Anslysis on the Effectiveness of Scaffoldings for Language Learning with Educational Robots and IoT-Based Tangible Objects. 2023 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT), 152–154. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q., Fu, C., Ban, M., & Iio, T. (2024). A systematic review on robot-assisted language learning for adults. Frontiers in Psychology, 15. [CrossRef]

- Derakhshan, A., Teo, T., Saeedy Robat, E., Janebi Enayat, M., & Jahanbakhsh, A. A. (2024). Robot-Assisted Language Learning: A Meta-Analysis. Review of Educational Research, 00346543241247227. [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N., Kumar, S., Mukherjee, D., Pandey, N., & Lim, W. M. (2021). How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 133, 285–296. [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Z. (1998). Motivation in second and foreign language learning. Language Teaching, 31(3), 117–135. [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Z. (2014). The Psychology of the Language Learner: Individual Differences in Second Language Acquisition. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Engwall, O., & Lopes, J. (2022). Interaction and collaboration in robot-assisted language learning for adults. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(5–6), 1273–1309. [CrossRef]

- Gogus, A. (2012). Constructivist Learning. In N. M. Seel (Ed.), Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning (pp. 783–786). Springer US. [CrossRef]

- Hardman & Co. (n.d.). (2021). Educational Robot Market with COVID-19 Impact Analysis by Type (Humano. HARDMAN AND WELL MANAGEMENT CONSULTANCIES L.L.C. https://www.hardmanwell.com/products/educational-robot-market-with-covid-19-impact-analysis-by-type-humanoid-robots-collaborative-industrial-robots-component-sensors-end-effectors-actuators-education-level-higher-education-special-education-and-region-global-forecast-to-2026.

- Herberg, J. S., Feller, S., Yengin, I., & Saerbeck, M. (2015). Robot watchfulness hinders learning performance. 2015 24th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN), 153–160. [CrossRef]

- Hyun, E., Kim, S., Jang, S., & Park, S. (2008). Comparative study of effects of language instruction program using intelligence robot and multimedia on linguistic ability of young children. RO-MAN 2008 - The 17th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication, 187–192. [CrossRef]

- Iio, T., Maeda, R., Ogawa, K., Yoshikawa, Y., Ishiguro, H., Suzuki, K., Aoki, T., Maesaki, M., & Hama, M. (2019). Improvement of Japanese adults’ English speaking skills via experiences speaking to a robot. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 35(2), 228–245. [CrossRef]

- Jakonen, T., & Jauni, H. (2024). Managing activity transitions in robot-mediated hybrid language classrooms. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 37(4), 872–895. [CrossRef]

- Jaleniauskienė, E., Lisaitė, D., & Daniusevičiūtė-Brazaitė, L. (2023). Artificial Intelligence in Language Education: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainable Multilingualism, 23(1), 159–194. [CrossRef]

- Kanero, J., Geçkin, V., Oranç, C., Mamus, E., Küntay, A. C., & Göksun, T. (2018). Social Robots for Early Language Learning: Current Evidence and Future Directions. Child Development Perspectives, 12(3), 146–151. [CrossRef]

- Karakaş Kurt, E., & Güneyli, A. (2023). Teaching the Turkish language to foreigners at higher education level in Northern Cyprus: An evaluation based on self-perceived dominant intelligence types, twenty-first-century skills and learning technologies. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1120701. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J., Baxter, P., Senft, E., & Belpaeme, T. (2016). Social robot tutoring for child second language learning. 2016 11th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI), 231–238. [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, A., Kato, T., & Yamamoto, S. (2016, May 1). Joining-in-type Humanoid Robot Assisted Language Learning System. International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Joining-in-type-Humanoid-Robot-Assisted-Language-Khalifa-Kato/879e9c59d4f0a4baa2efb34f1e7c1cf30887fecb.

- Krashen, S. D. (1982). Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition. Elsevier Science & Technology.

- Kress, G. R., & Leeuwen, T. van. (2001). Multimodal discourse: The modes and media of contemporary communication. Arnold.

- Lee, H., & Lee, J. H. (2022). The effects of robot-assisted language learning: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 35, 100425. [CrossRef]

- Liao, J., Lu, X., Masters, K. A., Dudek, J., & Zhou, Z. (2022). Telepresence-place-based foreign language learning and its design principles. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(3), 319–344. [CrossRef]

- Lim, W. M., & Kumar, S. (2024). Guidelines for interpreting the results of bibliometric analysis: A sensemaking approach. Global Business and Organizational Excellence, 43(2), 17–26. [CrossRef]

- Lim, W. M., Kumar, S., & Donthu, N. (2024). How to combine and clean bibliometric data and use bibliometric tools synergistically: Guidelines using metaverse research. Journal of Business Research, 182, 114760. [CrossRef]

- Linden, K., Arndt, J., Neef, C., & Richert, A. (2023). A Companion for Aphasia Training: Development and Early Stakeholder Evaluation of a Robot-Assisted Speech Training App*. 2023 32nd IEEE International Conference on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN), 2585–2590. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Mai, F., & MacDonald, C. (2019). A Big-Data Approach to Understanding the Thematic Landscape of the Field of Business Ethics, 1982–2016. Journal of Business Ethics, 160(1), 127–150. [CrossRef]

- Murnane, M., Breitmeyer, M., Matuszek, C., & EnQel, D. (2019). Virtual Reality and Photogrammetry for Improved Reproducibility of Human-Robot Interaction Studies. 2019 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces (VR), 1092–1093. [CrossRef]

- Najima, T., Kato, T., Tamura, A., & Yamamoto, S. (2021). Remote Learning of Speaking in Syntactic Forms with Robot-Avatar-Assisted Language Learning System. In K. Ekštein, F. Pártl, & M. Konopík (Eds.), Lecture Notes in Computer Science (3 📊; Vol. 12848, pp. 558–566). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Nasihati Gilani, S., Traum, D., Merla, A., Hee, E., Walker, Z., Manini, B., Gallagher, G., & Petitto, L.-A. (2018). Multimodal Dialogue Management for Multiparty Interaction with Infants. Proceedings of the 20th ACM International Conference on Multimodal Interaction, 5–13. [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, O., Kocaman, R., & Kanbach, D. K. (2024). How to design bibliometric research: An overview and a framework proposal. Review of Managerial Science, 18(11), 3333–3361. [CrossRef]

- Sapounidis, T., Tselegkaridis, S., & Stamovlasis, D. (2024). Educational robotics and STEM in primary education: A review and a meta-analysis. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 56(4), 462–476. [CrossRef]

- Sin, P. F., Hong, Z.-W., Tsai, M.-H. M., Cheng, W. K., Wang, H.-C., & Lin, J.-M. (2022). METMRS: A Modular Multi-Robot System for English Class. In Y.-M. Huang, S.-C. Cheng, J. Barroso, & F. E. Sandnes (Eds.), Innovative Technologies and Learning (Vol. 13449, pp. 157–166). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Sungjin Lee, Hyungjong Noh, Jonghoon Lee, Kyusong Lee, & Gary Geunbae Lee. (2012). Foreign Language Tutoring in Oral Conversations Using Spoken Dialog Systems. IEICE Transactions on Information and Systems, E95.D(5), 1216–1228. [CrossRef]

- Tong, R., Chen, N. F., & Ma, B. (2017). Multi-Task Learning for Mispronunciation Detection on Singapore Children’s Mandarin Speech. Interspeech 2017, 2193–2197. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, R., Asghar, I., & Griffiths, M. G. (2022). An Integrated Methodology for Bibliometric Analysis: A Case Study of Internet of Things in Healthcare Applications. Sensors, 23(1), 67. [CrossRef]

- van den Berghe, R., Oudgenoeg-Paz, O., Verhagen, J., Brouwer, S., de Haas, M., de Wit, J., Willemsen, B., Vogt, P., Krahmer, E., & Leseman, P. (2021). Individual Differences in Children’s (Language) Learning Skills Moderate Effects of Robot-Assisted Second Language Learning. Frontiers in Robotics and AI, 8, 676248. [CrossRef]

- van den Berghe, R., Verhagen, J., Oudgenoeg-Paz, O., van der Ven, S., & Leseman, P. (2019). Social Robots for Language Learning: A Review. Review of Educational Research, 89(2), 259–295. [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2010). Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics, 84(2), 523–538. [CrossRef]

- Veivo, O., & Mutta, M. (2022). Dialogue breakdowns in robot-assisted L2 learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Vogt, P., van den Berghe, R., de Haas, M., Hoffman, L., Kanero, J., Mamus, E., Montanier, J.-M., Oranc, C., Oudgenoeg-Paz, O., Garcia, D. H., Papadopoulos, F., Schodde, T., Verhagen, J., Wallbridgell, C. D., Willemsen, B., de Wit, J., Belpaeme, T., Goksun, T., Kopp, S., … Pandey, A. K. (2019). Second Language Tutoring Using Social Robots: A Large-Scale Study. 2019 14th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI), 497–505. [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: Development of Higher Psychological Processes (M. Cole, V. Jolm-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, Eds.). Harvard University Press. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F., & Cheung, A. C. K. (2024). Robots’ Social Behaviors for Language Learning: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Review of Educational Research, 00346543231216437. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J., Wang, Y., Murnane, M., Higgins, P., Saraf, M., Ferraro, F., Matuszek, C., & Engel, D. (2021). A Simulator for Human-Robot Interaction in Virtual Reality. 2021 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces Abstracts and Workshops (VRW), 470–471. [CrossRef]

- Zhexenova, Z., Amirova, A., Abdikarimova, M., Kudaibergenov, K., Baimakhan, N., Tleubayev, B., Asselborn, T., Johal, W., Dillenbourg, P., CohenMiller, A., & Sandygulova, A. (2020). A Comparison of Social Robot to Tablet and Teacher in a New Script Learning Context. Frontiers in Robotics and AI, 7, 99. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).