1. Introduction

According to the “Vocabulary in Metrology” (VIM), the term “measurement traceability” is a “property of a measurement result whereby the result can be related to a reference through a documented unbroken chain of calibrations, each contributing to the measurement uncertainty” [

1]. Thus, traceability requires calibration (as defined in the VIM) as well as documentation about each calibration in a chain from the measuring instrument to a reference. The ultimate reference for measurement results are realizations of the international system of units of measurement – the SI. A traceable measurement in metrology is relatable to the SI via the unbroken chain of calibrations. This is important to ensure comparability and reliability of measurement results. By following their traces, different measurements of the same quantity can be compared to each other, and their quality can be assessed. This is of particular importance in cases where data from different sources is aggregated; and in the quality infrastructure where conformity with regulatory requirements needs to be approved.

In digital infrastructures, the term “traceability” usually refers to a digital trace to the origin and the provenance of data. This traceability allows users to track changes made to the data, e.g., content or location. This is an important property of data to assess reliability of their content. For instance, in a product specification, the provenance of conformity statements is important metadata for end-users and regulators.

The realization of communicating metrological and digital traceability has certain similarities. In both cases, information relevant to the statement of traceability is gathered and provided to customers and end-users. In both cases, digital anchors of trust are considered to ensure trustworthiness and immutability of this information. In both cases, an established technical solution for a digital anchor of trust is an electronic signature based on a Public Key Infrastructure (PKI). And in both cases, distributed ledger technologies are considered an alternative technical solution [

2].

In data spaces, the digital traceability of a data set is realized using a number of different technologies. Examples are digital identities linked to data sets; digital verifiable credentials; and clearing houses based on distributed ledger technologies. In this contribution, we discuss the use of technologies for the implementation of metrological traceability.

With the digital transformation of the quality infrastructure, in particular in metrology, the transition from paper-based processes to digital processes is becoming the default method. Therefore, a commonly applied and internationally harmonized technical implementation of metrological traceability becomes increasingly important. Moreover, activities within the German initiative “QI-Digital” [

3,

4] demonstrated that the interconnection of metrological traceability with other digital solutions in the QI enables more efficient processes. For instance, the combination of an electronic signature based on a digital trust anchor provided by the national accreditation body, and a digital calibration certificate [

5] enables an automated digital verification that the calibration of a given measuring device has been carried out by an accredited laboratory.

Overall, the scope of this paper is to discuss the opportunities of an interoperable digital metrological infrastructure based on emerging technologies and international standards of the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). The paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 introduces the relevant background and foundations for this work, such as terminology and existing technologies.

Section 3 outlines the potential use of data spaces as technical implementation for traceability in metrology and the wider QI. In

Section 4, we discuss the concepts of the DPP as use case for digital metrological traceability. Finally, in Section 5 we draw some conclusions and provide an outlook.

2. Background and Foundations

Digital transformation in metrology is aiming for more efficient processes, gaining more insight into measurement results, and improving reusability of measurement data. This comprises transformational processes within organizations and for the provision of services. The Digital Calibration Certificate (DCC) is an international example for this transformation [

5]. Initiated by the Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt, the German National Metrology Institute, the DCC development has become an international effort, including a dedicated task group in the Forum “Metrology and Digitalization”, established by the committee of the meter convention (CIPM).

The DCC is a data model with an XML schema as reference implementation [

5]. The XML structure enables software to find and access content of the certificate in a very granular way. In the same way, software can create an XML DCC and fill in content from other sources. This is a prerequisite for automated digital processes. As an example, we consider the intra-organizational process for a calibration service:

Receiving an order of a calibration request

Administrative processing of the order

Carrying out the calibrations

Creating the certificate

Drawing up an invoice

Providing the certificate and related material to the customer

Each step, after the initial placement of the order by the customer, utilizes some information from earlier process steps [

6]. Automation of the whole process thus requires making available the information elements from previous steps, e.g., by application programmable interfaces (APIs). Step 4, the creation of the certificate, puts all information elements related to the service together in the XML file. This can be signed electronically, to secure the content against manipulation, and to provide digital traceability to the issuing organization [

5]. An established technology for electronic signatures is the use of a public key infrastructure (PKI). A PKI provides a form of digital traceability from an electronic signature through several steps up to a root certificate provided by an acknowledged anchor of trust.

For decades, the quality infrastructure has relied on the traceability of information from a single asset or statement to non-digital anchors of trust like a national body, and internationally recognized authority. Digital transformation of the quality infrastructure consequently comprises the transfer of the established trust chains from the analogue to the digital world. A recent example is the German accreditation body (DAkkS,

www.dakks.de), which developed a PKI-based digital anchor of trust for specific electronic signatures. These signatures allow verifying the identity of the issuer, but additionally include the confirmation from DAkkS that the issuer has a valid accreditation. In this way, the human-oriented printing of the DAkkS logo on a certificate can be transformed into a software-oriented digital statement which can be verified automatically by a machine [

7].

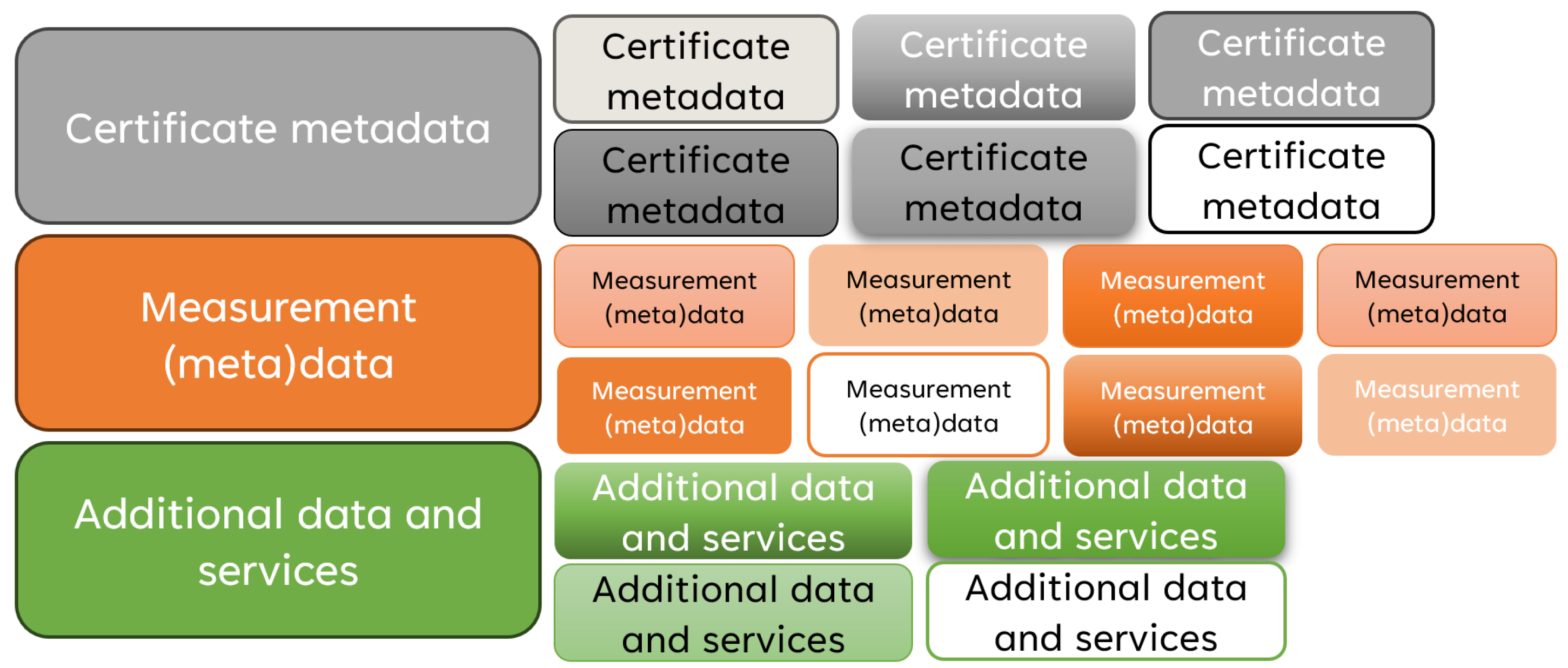

For the automation of digital process to be most efficient, the to-be-processed information must be available in structural, self-contained elements – ideally expressed in a machine-readable way. For a digital certificate, this can be achieved by considering the certificate as a database rather than a document. That is, elements of the certificate are considered as information modules organized in a hierarchical structure. For instance, the DCC holds information such as data and time of calibration, issuing organization, serial number of the device, and number of calibration points. If the certificate is treated like a database, all information modules can be accessed directly and independently from the rest of the certificate, see

Figure 1.

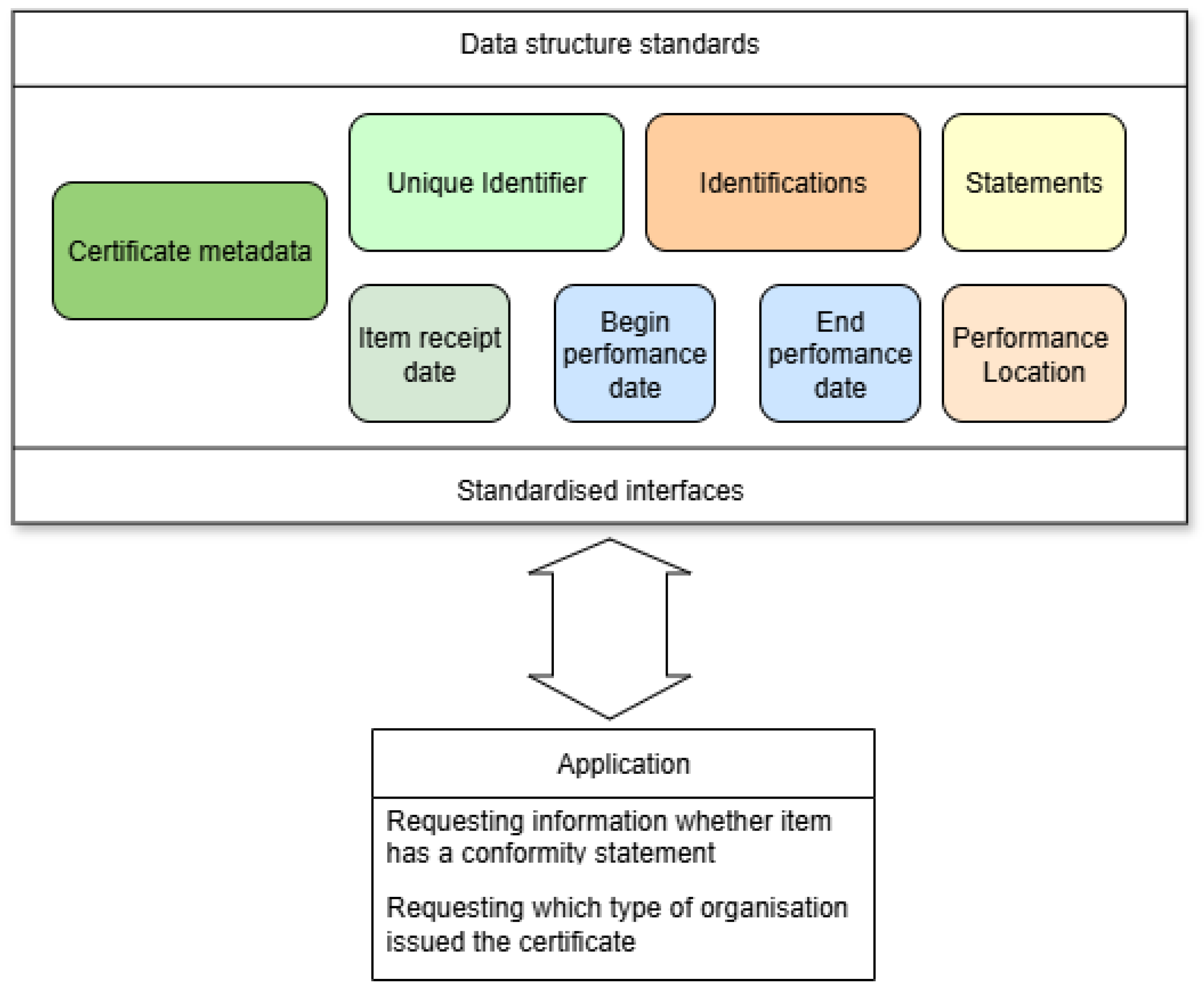

The corresponding processes, for instance for workflows within the quality infrastructure, can then be designed to take advantage of the accessibility of such information modules. That is, the processes are not designed based on the circulation of documents but instead rely on APIs or other means to obtain exactly the information needed for a certain process step, see

Figure 2 for a visualization of a simplified example.

In the quality infrastructure, processes are usually product focused. For instance, assessing the conformity of a measuring instrument with regulatory requirements requires calibration, conformity assessment, accreditation and standards. Calibrated measuring instruments provide metrological traceability for the measurements undertaken to assess conformity. The certificate of conformity proves that attests the conformity of the instrument is issued by an accredited organization that performs the conformity assessment based on standards and regulations. Consequently, processes in the quality infrastructure should put the product in the center of consideration and may thus differ from intra-organizational processes where focus on a certain product or asset may not always be equally relevant. This also leads to differences in the digitalization of such processes.

Paper-based processes limit the effectiveness of digital transformation in organizations and cause additional burdens and risks. Today, most organizations use digital workflows and infrastructures for their data and information management. Documentation is stored digitally using databases or file systems. Data processing is carried out using software tools. Moreover, many companies are pursuing the implementation of data-driven tools, such as artificial intelligence, to improve internal processes and to cope with the lack of skilled personnel. Paper-based quality infrastructure services thus cause media discontinuities for these organizations. The transfer of data and information from paper to digital infrastructures is laborious, error-prone, and time-consuming. For this reason, many organizations within the quality infrastructure have started their digital transformation in recent years. In this development, it has been identified early on that interoperability is a key issue. National initiatives such as QI-Digital in Germany, and the “Joint Statement of Intent” signed by all major international QI organizations, seek interoperability and harmonization of digital transformation developments [

3].

Interoperability can, for instance, be achieved through the following three basic approaches:

In a monolithic software solution, interfaces and data models are all part of the same software development. Thus, they can be designed specifically for the software to enable very high performance and reliability. This is important for use cases where APIs are not to be shared openly and where processes are very stable [

8]. However, monolithic software can become very complex and inflexible when extensions and additional features are added over time. Maintenance and handling of the monolithic software then become a critical risk for operations.

Domain-specific standards are, for instance, used in data spaces. In these cases, a group of organizations with common interest in data sharing and digital services defines rules and operational specifications. Only approved interfaces and data models are integrated into the data space. At the same time, changes or extensions to the software solutions can be handled in a more flexible way based on the standards set for the data space compared to a monolithic software stack. The International Data Spaces Association (IDSA) specifies general elements and a reference architecture model for data spaces [

9]. This supports the creation of a domain-specific data space. However, the initial task of agreeing on operational procedures and standards remains. Moreover, changes to these standards as well as maintenance of the overall data space must be organized.

The use of general standards, such as W3C specifications, may reduce the design space compared to domain-specific and therefore tailor-made interfaces and software solutions. However, they offer the advantage that more software tools are available and sharing data between domains becomes easier. Moreover, general standards can also be specific for a larger domain. For instance, the UN Transparency Protocol (UNTP) considers procedures based on verifiable credentials (VC) and decentralized identities (DID) for verifiable conformity statements. This requires domain-specific authority repositories, implementing roles and responsibilities from the domain of conformity assessment. However, the underlying technology of VC and DID is based on general W3C standards.

In practice, there is usually no strict implementation of only one of these three approaches. For instance, the concept of the European Metrology Cloud comprises monolithic nodes to build a data space for legal metrology. However, the nodes themselves use separate modules communicating based on web-based technologies similar to elements of a data space as specified by the IDSA [

8,

9]. Thus, the concept of data spaces and their role in digital traceability for metrology is of great interest for digital transformation.

3. Digital Traceability in Data Spaces

Processes in the quality infrastructure rely on the mutual sharing of information and data, technological and regulatory trust frameworks, and common vocabularies. For instance, the conformity assessment for a product requires information from the manufacturer, access to standards, and – for the certificate of conformity – a mutually accepted framework for authenticating the certificate. Traceability of statements in such a scenario comprises access to all relevant information for an auditor, a customer, or other interested parties in order to assess the statements’ validity. In an analogue world this is realized mostly on a mutual recognition of regulatory frameworks, e.g., based on the rules for CE markings for products sold in the European Union. That is, relevant information about the product is usually made available as paper handed out together with the product.

Federated data spaces provide a technological framework to accomplish the digital transformation of processes in the quality infrastructure. A data space is basically a governance framework for handling metadata about data provenance, identities, interfaces, vocabulary, data policies, etc. One particular example is the GAIA-X framework. It defines a set of modules which can be used as building blocks for governing resources, managing identities, granting access and setting up rules through data attributes. Credentials and labels are assigned to assets and participates according to previously agreed rules, access rights and other data properties. A so-called “clearing house” manages handling of credentials and can be used to enforce data policies. An important aspect of such a data space framework is the federated provision of data and services. That is, instead of centralized resources, multiple actors can provide modules and services within the data space. A registry, a set of compliance rules, and a corresponding certification provider ensure interoperability and accessibility. A more general reference architecture for data spaces is defined by the International Data Spaces Association (IDSA). It defines fundamental elements for functional, technical, operational, legal, and commercial aspects of a data space. The common fundamental feature of all such developments is to ensure data sovereignty. That is, instead of providing data in an open way accessible to everyone, sharing of data is organized based on predefined rules and procedures. The data space modules are the technical realizations of such rules and procedures.

An important aspect of any data space providing data or services for quality infrastructure purposes is the definition of role-based access rights. For instance, an official representative of a market surveillance body should be able to identify with that very role to the data space in order to gain access to all documents and information required for their specific tasks, e.g., verification. Therefore, the data space rules and procedures must contain suitable access rights for that role. The European Digital Identity Wallet (EUDI) developments go in that direction by considering organizational wallets that enable an organization to digitally identify itself to other organizations and platforms, share specific data and documents from their wallet to others, and create electronic signatures and seals with their wallet identity. It can thus be expected that future data space standards will include EUDI Wallets and similar developments as accepted identity providers. Thus, such wallet solutions should contain rules related to quality infrastructure roles. This would allow for the specification of role-based access rights to data spaces being applicable cross-sectoral and independent from the other, domain-specific, data space roles and access rights.

4. The Digital Product Passport

In very simple terms, a Digital Product Passport (DPP) is a structured collection of properties and data related to an individual product, or a product batch or type. The first DPP in Europe will be the battery passport for which the EU Regulation 2023/1542 sets requirements and procedures. This regulation defines the properties that must be provided in the battery’s DPP as well as the requirement for the underlying DPP system to consider role-based access. Organizations with a legitimate interest and authorities should gain access to a much richer set of information than the general public. However, the actual technical specification of such a DPP system is still under development at the level of CEN/CENELEC.

Nevertheless, digital and metrological traceability concepts can be outlined properly based on the existing information from Regulation EU2023/1542 and the Battery Passport Project. Digital traceability is indeed one of the main drivers behind the EU activities for the DPP. Similar to the motivation behind the UNTP, the EU aims to address the need for tracing claims about product properties along the product lifecycle and across the supply chain. The DPP serves as central element which points to all digital traces required for this purpose. For instance, the material from which the battery is built must not only be named in the DPP, but actual information about the source and supplier must be provided. EU2023/1542 foresees a distributed data infrastructure for this, instead of a central database or singular platform.

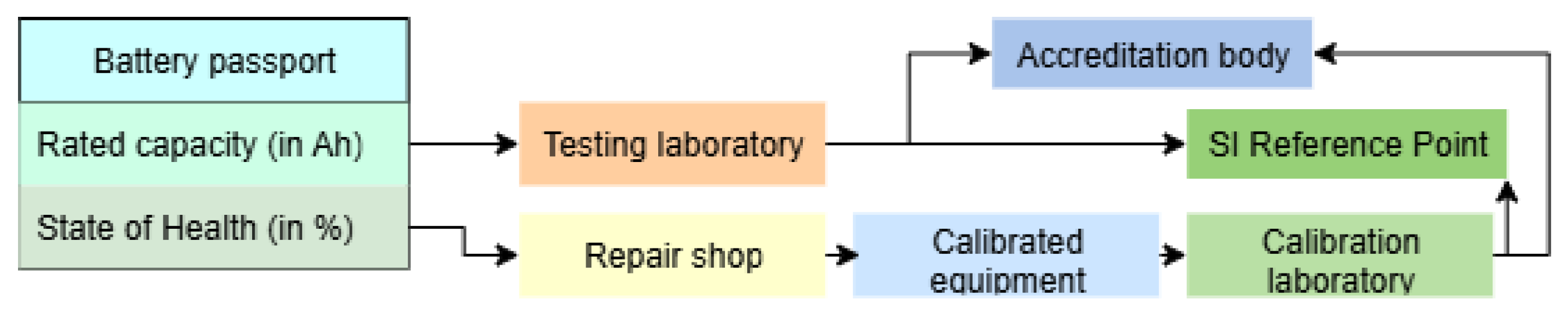

For metrological traceability for the battery passport, consider the use case of an organization buying a set of used batteries. This organization requires information about rated capacity and state of health for deciding about the batteries’ value and potential further use.

Figure 3 shows a potential scenario outline for this use case. The rated capacity may have been tested by an accredited laboratory to validate the manufacturer’s claim. The DPP property would then be linked by reference to the testing laboratory which itself provides the proof of being accredited for this service at the time of measurement. Moreover, the testing laboratory in the test report may link to the SI reference point as a means for digital interoperability of encoding units digitally. Similarly, the state of health may have been evaluated by a car repair shop based on some standardized routines and calibrated equipment. The property in the DPP would then be linked to the repair shop, which provides proof about the calibration of their equipment at the time of measurement. Based on these digital traces, the organization that bought the batteries can assess the batteries in a comparable way due to all measurements being traceable to the SI. For the accredited laboratory, the traceability is implicitly provided by proof of being accredited. For the repair shop’s equipment, parts of the traceability chain are provided via the calibration proofs.

The fundamental technical aspect in this and other use cases based on DPP and data spaces is that all data is held in a distributed infrastructure where each datum can remain at the data infrastructure of the respective datum owner. This is different to approaches such as, for instance, the recently published QR-code service offered by the Austrian metrology body BEV [

11]. In the BEV concept, a QR-code refers to a web-based service provided by BEV that holds all relevant data and information about the product. Nevertheless, the resource referred to via such a QR-code could be used for a property within a DPP to link to the BEV resources backing up the statement of product conformity.

6. Conclusions and Outlook

Concepts and technologies for digital traceability can be applied to implement metrological traceability. This holds true in particular for the upcoming Digital Product Passport (DPP), whenever it contains properties based on metrological services.

Existing technologies such as verifiable credentials, data spaces, and distributed ledger (blockchain) offer a ready-to-use basis for implementing metrological traceability. Developments such as the Digital Calibration Certificated (DCC) and similar developments, e.g., the Digital Certificate of Conformity (D-CoC) [

12], provide modular data structures. These can serve as basis for granular traceability chains in the future. For instance, the D-CoC for a product can contain reference to the DPPs of the measuring devices used in the metrological part of the conformity assessment. Each of these DPPs can provide digital references to DPPs about the measuring devices used in their calibration. In this way, the traceability chain becomes transparent and accessible to algorithms for addressing metrological questions in traceability, such as identification of common sources of uncertainty and correlations due to the same measurement standards applied.

An important prerequisite for the successful implementation of metrological traceability chains is the semantic harmonization of data structures in certificates and reports, as well as in the semantic specification of role-based access rights.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, S.E. and J.N.; methodology, S.E. and J.N.; investigation, S.E. and J.N.; writing—original draft preparation, S.E.; writing—review and editing, S.E. and J.N.; visualization, S.E.; supervision, S.E.; project administration, J.N.; funding acquisition, J.N.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very thankful for the support provided by the German Federal Ministry of Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWE) for the initiative “QI-Digital”, which has been the basis for this work. During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used Google Gemini 2.5 for the purposes of analyzing EU Regulation 2023/1542 in relation to the rich documentation provided by the Battery Passport Project. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- BIPM JCGM WG2. JCGM 200:2012 International Vocabulary of Metrology – Basic and General Concepts and Associated Terms (VIM). Third Edition. 20212.

- Takegawa N., Furuichi N. Traceability Management System Using Blockchain Technology and Cost Estimation in the Metrology Field. Sensors. 2023; 23(3):1673. [CrossRef]

- Eichstädt S, Hutzschenreuter D, Niederhausen J, Neumann J. The quality infrastructure in the digital age: beyond machine-readable documents. Proceedings of IMEKO M4DConf 2022.

- Niederhausen J., Hansen H., Eichstädt S. Towards a structural foundation of a quality infrastructure in the digital world. Proceedings of SMSI 2023 . [CrossRef]

- Schönhals S. et al. Harmonisation processes and practical implementation of machine-interpretable digital calibration certificates. Measurement: Sensors: 38 (2025), Suppl., e1 - e4 . [CrossRef]

- Keidel A., Kulka-Peschke C., Oppermann A., Eickelberg S., Meiborg M. Digital transformation of processing metrological services. Proceedings of the SMSI 2023 . [CrossRef]

- Niederhausen, J. The digital transformation of the quality infrastructure supports the energy transition. tm - Technisches Messen, vol. 92, no. 9-10, 2025, pp. 424-430 . [CrossRef]

- Nordholz J., Dohlus M., Gräflich J., Kammeyer A., Nischwitz M., Wetzlich J., Yurchenko A., Thiel F. Evolution of the European Metrology Cloud. OIML Bulletin: LXII (2021), 3, 27 – 34.

- International Data Spaces Reference Architecture. Release 4.2.0. 2023. https://github.com/International-Data-Spaces-Association/IDS-RAM_4_0/releases/tag/v4.2.0.

- Battery Passport Project.

- Wonaschütz A., Santos da Costa J. P., Milota P. Digital transparency in legal metrology: Enhancing accessibility and trust through QR codes and digital solutions. 2025 OIML Bulletin LXVI(2) 20250204.

- Sheveleva T., Foyer G., Knopf D. Interoperability challenges between the Digital Conformity Credential data model (UNTP-DCC) and the data structures for the Digital Calibration Certificate (DCC) and Digital Certificate of Conformity (D-CoC). Measurement: 257 (2026), C, 1 – 12 . [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).