Submitted:

23 October 2025

Posted:

24 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

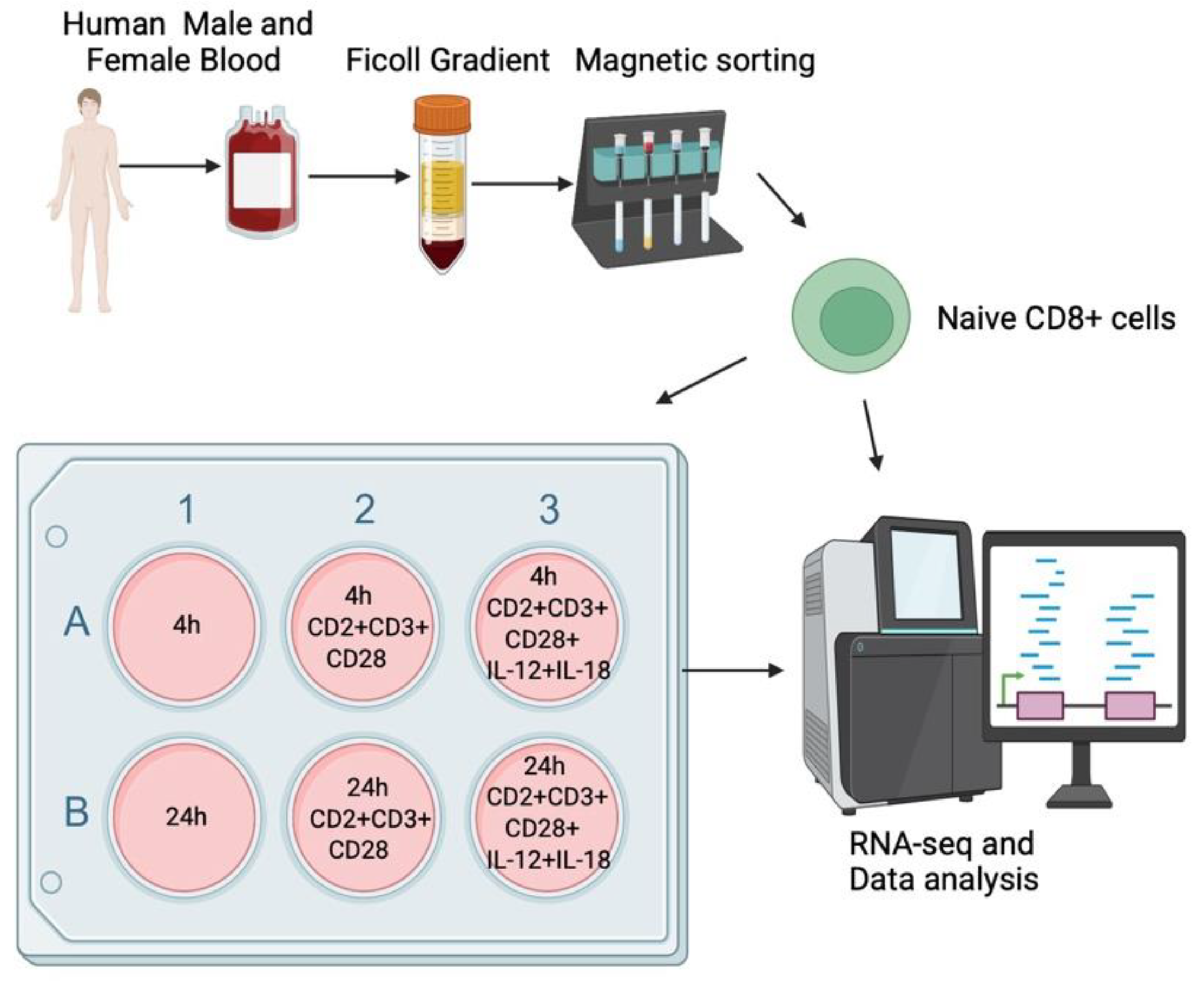

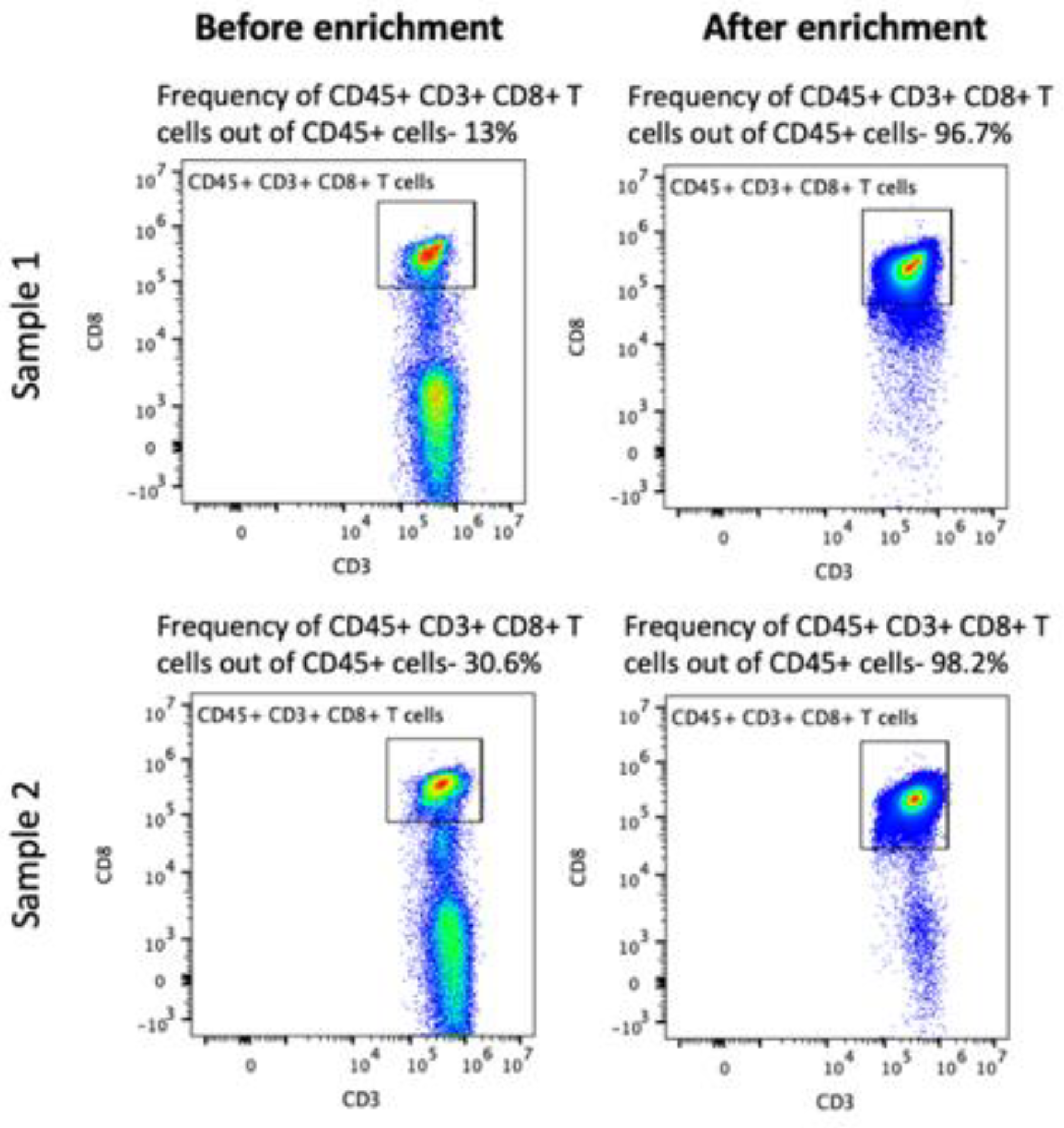

2.1. Isolation of Human Peripheral Blood CD8+ T Cells

2.2. Activation of CD8+ T Cells

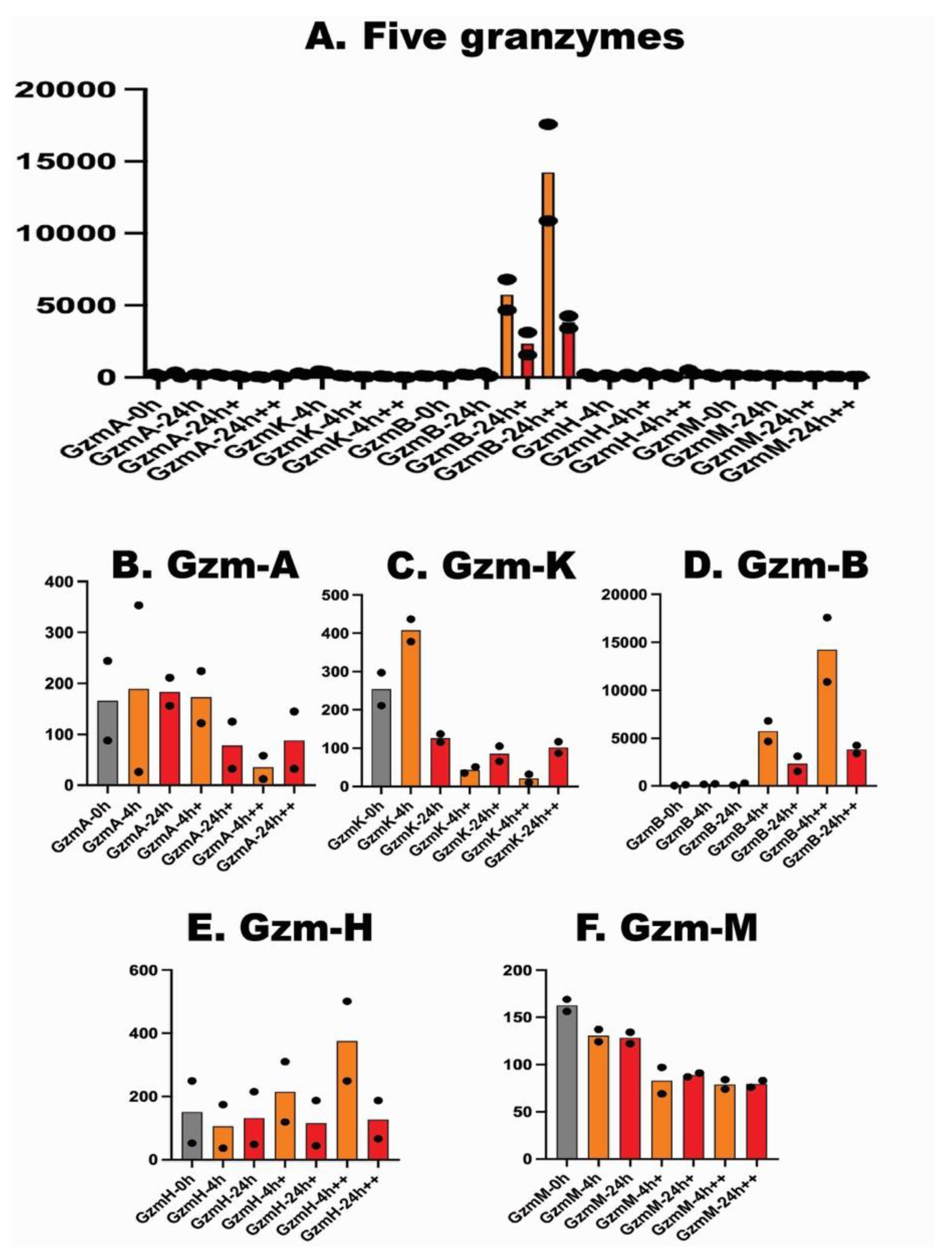

2.3. Effect on Granule-Stored Proteins by Activation of CD8+ T Cells

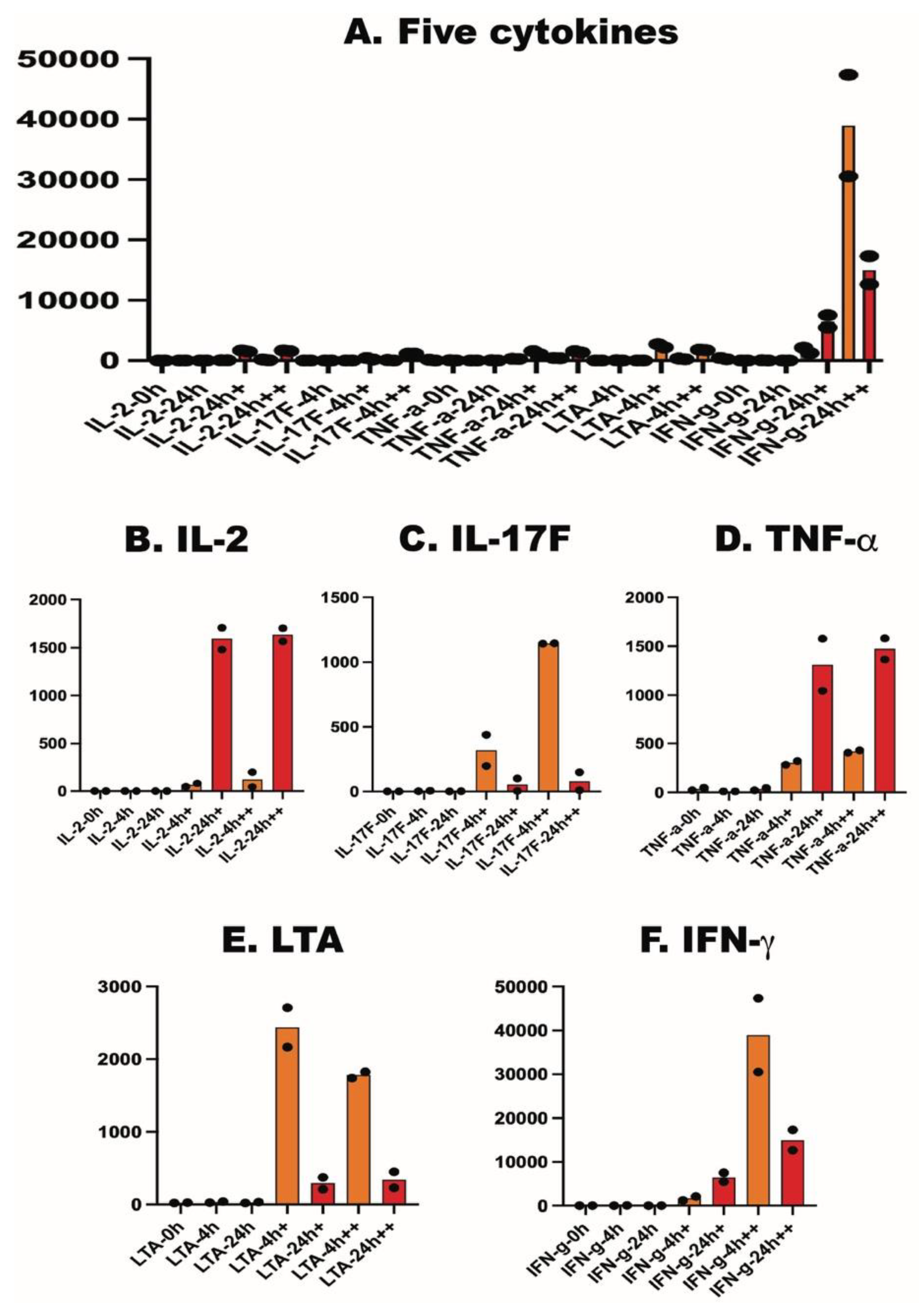

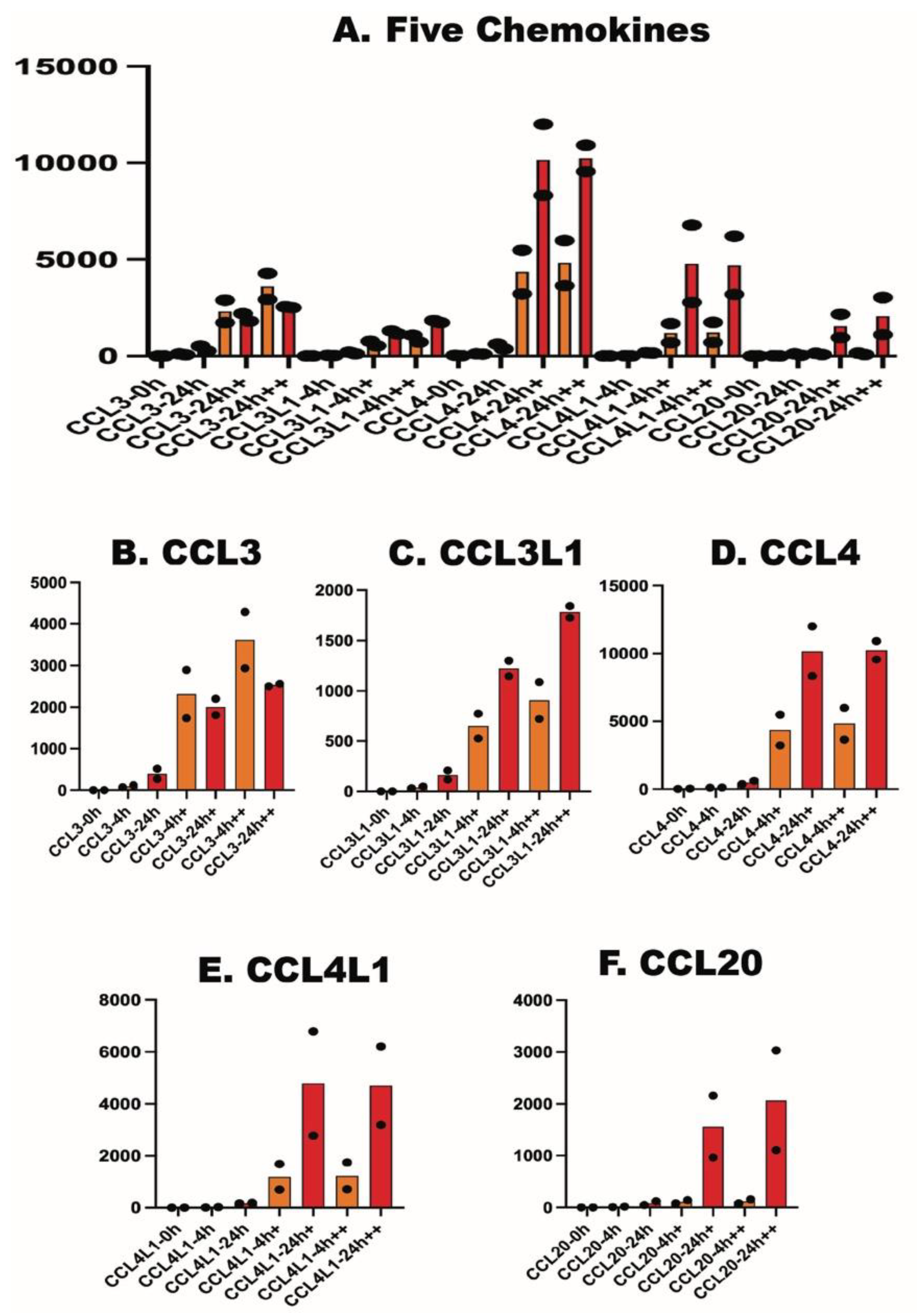

2.4. Effect on Cytokines, Chemokines and Cytokine Receptors

2.5. Effect on Two TNF Receptor Superfamily Members

2.6. Effect on Micro RNAs and Transcription Factors

2.7. Effect on House-Keeping Genes Used as Reference Genes in Northern Blots and q-PCR.

2.8. Effect on Solute Carriers.

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Isolation of Human Peripheral Blood CD8+ T Cells

4.2. Activation of the CD8+ T Cells

4.3. RNA-seq Analysis of the Total Transcriptome

Supplementary data

Abbreviations:

References

- Akula S, Thorpe M, Boinapally V, Hellman L. Granule Associated Serine Proteases of Hematopoietic Cells - An Analysis of Their Appearance and Diversification during Vertebrate Evolution. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0143091.

- Akula S, Alvarado-Vazquez A, Haide Mendez Enriquez E, Bal G, Franke K, Wernersson S, et al. Characterization of Freshly Isolated Human Peripheral Blood B Cells, Monocytes, CD4+ and CD8+ T Cells, and Skin Mast Cells by Quantitative Transcriptomics. International journal of molecular sciences. 2024;25(23).

- Hellman L, Thorpe M. Granule proteases of hematopoietic cells, a family of versatile inflammatory mediators - an update on their cleavage specificity, in vivo substrates, and evolution. Biol Chem. 2014;395(1):15-49.

- Hunig T, Tiefenthaler G, Meyer zum Buschenfelde KH, Meuer SC. Alternative pathway activation of T cells by binding of CD2 to its cell-surface ligand. Nature. 1987;326(6110):298-301.

- Li Y, Kurlander RJ. Comparison of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28-coated beads with soluble anti-CD3 for expanding human T cells: differing impact on CD8 T cell phenotype and responsiveness to restimulation. J Transl Med. 2010;8:104.

- Lustig A, Manor T, Shi G, Li J, Wang YT, An Y, et al. Lipid Microbubble-Conjugated Anti-CD3 and Anti-CD28 Antibodies (Microbubble-Based Human T Cell Activator) Offer Superior Long-Term Expansion of Human Naive T Cells In Vitro. Immunohorizons. 2020;4(8):475-84.

- Henry CJ, Ornelles DA, Mitchell LM, Brzoza-Lewis KL, Hiltbold EM. IL-12 produced by dendritic cells augments CD8+ T cell activation through the production of the chemokines CCL1 and CCL17. J Immunol. 2008;181(12):8576-84.

- Landy E, Carol H, Ring A, Canna S. Biological and clinical roles of IL-18 in inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2024;20(1):33-47.

- Alvarado-Vazquez PA, Mendez-Enriquez E, Salomonsson M, Waern I, Janson C, Wernersson S, et al. Circulating mast cell progenitors increase during natural birch pollen exposure in allergic asthma patients. Allergy. 2023;78(11):2959-68.

- Dotiwala F, Mulik S, Polidoro RB, Ansara JA, Burleigh BA, Walch M, et al. Killer lymphocytes use granulysin, perforin and granzymes to kill intracellular parasites. Nature medicine. 2016;22(2):210-6.

- Voskoboinik I, Dunstone MA, Baran K, Whisstock JC, Trapani JA. Perforin: structure, function, and role in human immunopathology. Immunol Rev. 2010;235(1):35-54.

- Ronnberg E, Pejler G. Serglycin: the master of the mast cell. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;836:201-17.

- Walch M, Dotiwala F, Mulik S, Thiery J, Kirchhausen T, Clayberger C, et al. Cytotoxic cells kill intracellular bacteria through granulysin-mediated delivery of granzymes. Cell. 2014;157(6):1309-23.

- Wolpe SD, Davatelis G, Sherry B, Beutler B, Hesse DG, Nguyen HT, et al. Macrophages secrete a novel heparin-binding protein with inflammatory and neutrophil chemokinetic properties. J Exp Med. 1988;167(2):570-81.

- Kouno J, Nagai H, Nagahata T, Onda M, Yamaguchi H, Adachi K, et al. Up-regulation of CC chemokine, CCL3L1, and receptors, CCR3, CCR5 in human glioblastoma that promotes cell growth. J Neurooncol. 2004;70(3):301-7.

- Menten P, Wuyts A, Van Damme J. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1. Cytokine & growth factor reviews. 2002;13(6):455-81.

- Guan E, Wang J, Norcross MA. Identification of human macrophage inflammatory proteins 1alpha and 1beta as a native secreted heterodimer. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(15):12404-9.

- Howard OM, Turpin JA, Goldman R, Modi WS. Functional redundancy of the human CCL4 and CCL4L1 chemokine genes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;320(3):927-31.

- Hieshima K, Imai T, Opdenakker G, Van Damme J, Kusuda J, Tei H, et al. Molecular cloning of a novel human CC chemokine liver and activation-regulated chemokine (LARC) expressed in liver. Chemotactic activity for lymphocytes and gene localization on chromosome 2. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(9):5846-53.

- Croft M. Co-stimulatory members of the TNFR family: keys to effective T-cell immunity? Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3(8):609-20.

- Dostert C, Grusdat M, Letellier E, Brenner D. The TNF Family of Ligands and Receptors: Communication Modules in the Immune System and Beyond. Physiol Rev. 2019;99(1):115-60.

- Neidemire-Colley L, Khanal S, Braunreiter KM, Gao Y, Kumar R, Snyder KJ, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 deletion of MIR155HG in human T cells reduces incidence and severity of acute GVHD in a xenogeneic model. Blood Adv. 2024;8(4):947-58.

- Peng SL. The T-box transcription factor T-bet in immunity and autoimmunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2006;3(2):87-95.

- Oh S, Hwang ES. The role of protein modifications of T-bet in cytokine production and differentiation of T helper cells. J Immunol Res. 2014;2014:589672.

- Somerville TDD, Xu Y, Wu XS, Maia-Silva D, Hur SK, de Almeida LMN, et al. ZBED2 is an antagonist of interferon regulatory factor 1 and modifies cell identity in pancreatic cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(21):11471-82.

- Hayward A, Ghazal A, Andersson G, Andersson L, Jern P. ZBED evolution: repeated utilization of DNA transposons as regulators of diverse host functions. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e59940.

- Scalise M, Pochini L, Console L, Losso MA, Indiveri C. The Human SLC1A5 (ASCT2) Amino Acid Transporter: From Function to Structure and Role in Cell Biology. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2018;6:96.

- Halestrap AP. The SLC16 gene family - structure, role and regulation in health and disease. Mol Aspects Med. 2013;34(2-3):337-49.

- Clemencon B, Babot M, Trezeguet V. The mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier (SLC25 family): pathological implications of its dysfunction. Mol Aspects Med. 2013;34(2-3):485-93.

- Lash LH. Mitochondrial glutathione transport: physiological, pathological and toxicological implications. Chem Biol Interact. 2006;163(1-2):54-67.

- Pastor-Anglada M, Mata-Ventosa A, Perez-Torras S. Inborn Errors of Nucleoside Transporter (NT)-Encoding Genes (SLC28 and SLC29). International journal of molecular sciences. 2022;23(15).

- Akula S, Fu Z, Wernersson S, Hellman L. The Evolutionary History of the Chymase Locus -a Locus Encoding Several of the Major Hematopoietic Serine Proteases. International journal of molecular sciences. 2021;22(20).

- Ryu J, Fu Z, Akula S, Olsson AK, Hellman L. Extended cleavage specificity of a Chinese alligator granzyme B homologue, a strict Glu-ase in contrast to the mammalian Asp-ases. Developmental and comparative immunology. 2021;128:104324.

- Thorpe M, Akula S, Hellman L. Channel catfish granzyme-like I is a highly specific serine protease with metase activity that is expressed by fish NK-like cells. Developmental and comparative immunology. 2016;63:84-95.

- Lieberman J. Granzyme A activates another way to die. Immunol Rev. 2010;235(1):93-104.

- Metkar SS, Menaa C, Pardo J, Wang B, Wallich R, Freudenberg M, et al. Human and mouse granzyme A induce a proinflammatory cytokine response. Immunity. 2008;29(5):720-33.

- Aybay E, Ryu J, Fu Z, Akula S, Enriquez EM, Hallgren J, et al. Extended cleavage specificities of human granzymes A and K, two closely related enzymes with conserved but still poorly defined functions in T and NK cell-mediated immunity. Frontiers in immunology. 2023;14:1211295.

- Nicola NA, Babon JJ. Leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF). Cytokine & growth factor reviews. 2015;26(5):533-44.

- Lara S, Akula S, Fu Z, Olsson AK, Kleinau S, Hellman L. The Human Monocyte-A Circulating Sensor of Infection and a Potent and Rapid Inducer of Inflammation. International journal of molecular sciences. 2022;23(7).

- Paolini R, Bernardini G, Molfetta R, Santoni A. NK cells and interferons. Cytokine & growth factor reviews. 2015;26(2):113-20.

- Morris G, Bortolasci CC, Puri BK, Marx W, O'Neil A, Athan E, et al. The cytokine storms of COVID-19, H1N1 influenza, CRS and MAS compared. Can one sized treatment fit all? Cytokine. 2021;144:155593.

| Sample 1 (female donor) | Sample 2 (male donor) | |||||||||||||

| Genes | 0 | 4h | 24h | 4h+ | 24h+ | 4h++ | 24h++ | 0 | 4h | 24h | 4h+ | 24h+ | 4h++ | 24h++ |

| GZMA | 88 | 26 | 156 | 122 | 32 | 12 | 34 | 156 | 327 | 55 | 102 | 93 | 46 | 113 |

| GZMK | 211 | 378 | 115 | 35 | 65 | 10 | 87 | 297 | 437 | 137 | 51 | 105 | 32 | 117 |

| GZMB | 43 | 173 | 86 | 6816 | 1552 | 17579 | 3411 | 131 | 231 | 302 | 4671 | 3130 | 10881 | 4262 |

| GZMH | 52 | 36 | 48 | 119 | 44 | 249 | 66 | 249 | 174 | 215 | 310 | 187 | 501 | 187 |

| GZMM | 156 | 124 | 122 | 69 | 87 | 74 | 76 | 169 | 137 | 134 | 97 | 91 | 84 | 83 |

| Perforin | 166 | 334 | 222 | 201 | 413 | 204 | 462 | 143 | 389 | 363 | 315 | 685 | 316 | 729 |

| GNLY | 374 | 324 | 304 | 93 | 281 | 44 | 259 | 1111 | 1070 | 1114 | 373 | 1024 | 276 | 1019 |

| SRGN | 673 | 363 | 856 | 645 | 2020 | 592 | 1771 | 646 | 325 | 792 | 756 | 1771 | 671 | 1492 |

| Sample 1 (female donor) | Sample 2 (male donor) | |||||||||||||

| Genes | 0 | 4h | 24h | 4h+ | 24h+ | 4h++ | 24h++ | 0 | 4h | 24h | 4h+ | 24h+ | 4h++ | 24h++ |

| IL-2 | 0.3 | 0 | 1 | 82 | 1480 | 201 | 1566 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 49 | 1707 | 46 | 1702 |

| IL2RA | 1 | 3 | 9 | 1042 | 454 | 1149 | 608 | 0.3 | 3 | 5 | 972 | 309 | 1117 | 382 |

| IL2RB | 165 | 154 | 432 | 388 | 547 | 330 | 610 | 168 | 195 | 466 | 365 | 509 | 370 | 542 |

| IL2RG | 362 | 1268 | 1484 | 793 | 1769 | 686 | 1623 | 335 | 951 | 1261 | 946 | 1486 | 894 | 1436 |

| IL-3 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 33 | 79 | 21 | 66 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 70 | 334 | 47 | 256 |

| IL-4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 15 | 1 | 14 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0 | 6 | 23 | 3 | 23 |

| IL-5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 8 |

| IL-10 | 0.5 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 13 | 10 | 13 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 23 | 10 | 17 |

| IL-13 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.1 | 20 | 42 | 7 | 38 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 37 | 52 | 12 | 55 |

| IL-17F | 0.1 | 6 | 0 | 199 | 4 | 1145 | 11 | 0.2 | 2 | 2 | 439 | 103 | 1143 | 151 |

| TNF-a | 49 | 10 | 46 | 282 | 1044 | 406 | 1364 | 22 | 10 | 22 | 320 | 1578 | 430 | 1581 |

| LTA | 25 | 42 | 33 | 2709 | 374 | 1827 | 452 | 20 | 26 | 22 | 2167 | 212 | 1741 | 232 |

| TNFSF14 | 3 | 28 | 24 | 116 | 553 | 79 | 494 | 2 | 26 | 20 | 139 | 334 | 85 | 277 |

| IFN-g | 6 | 44 | 6 | 2139 | 5477 | 47367 | 17308 | 12 | 12 | 2 | 1209 | 7516 | 30517 | 12639 |

| LIF | 0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 143 | 26 | 455 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 79 | 17 | 230 | 18 |

| IL-1a | 0 | 10 | 62 | 1 | 58 | 0.5 | 45 | 0 | 5 | 34 | 0.6 | 7 | 0.3 | 5 |

| IL-1b | 3 | 331 | 749 | 7 | 746 | 8 | 609 | 0.3 | 159 | 379 | 1 | 87 | 0.8 | 74 |

| IL-6 | 0.3 | 23 | 152 | 3 | 148 | 10 | 115 | 0.1 | 9 | 82 | 2 | 17 | 9 | 16 |

| IL-8 | 3 | 355 | 670 | 10 | 714 | 9 | 575 | 0.3 | 182 | 290 | 2 | 82 | 2 | 65 |

| CCL3 | 4 | 124 | 516 | 1736 | 1809 | 2935 | 2561 | 4 | 72 | 271 | 2895 | 2202 | 4283 | 2504 |

| CCL3L1 | 3 | 49 | 207 | 525 | 1145 | 724 | 1840 | 3 | 32 | 118 | 774 | 1300 | 1087 | 1726 |

| CCL4 | 19 | 100 | 620 | 3220 | 8314 | 3646 | 9560 | 43 | 119 | 373 | 5487 | 12002 | 5984 | 10922 |

| CCL4L1 | 0.3 | 12 | 184 | 692 | 2779 | 701 | 3188 | 2 | 21 | 162 | 1684 | 6786 | 1746 | 6209 |

| CCL20 | 2 | 18 | 120 | 143 | 2163 | 158 | 3031 | 0.4 | 9 | 48 | 83 | 960 | 82 | 1105 |

| Sample 1 (female donor) | Sample 2 (male donor) | |||||||||||||

| Genes | 0 | 4h | 24h | 4h+ | 24h+ | 4h++ | 24h++ | 0 | 4h | 24h | 4h+ | 24h+ | 4h++ | 24h++ |

|

TNFRSF4 OX40 |

2 | 2 | 5 | 150 | 63 | 109 | 72 | 1 | 0.7 | 6 | 171 | 52 | 100 | 58 |

|

TNFRSF18 GITR |

4 | 9 | 15 | 127 | 95 | 115 | 131 | 1 | 3 | 10 | 123 | 42 | 88 | 59 |

| Sample 1 (female donor) | Sample 2 (male donor) | |||||||||||||

| Genes | 0 | 4h | 24h | 4h+ | 24h+ | 4h++ | 24h++ | 0 | 4h | 24h | 4h+ | 24h+ | 4h++ | 24h++ |

| MIR155HG | 2 | 7 | 24 | 625 | 833 | 597 | 880 | 1 | 6 | 13 | 649 | 771 | 796 | 759 |

| TBX21 | 54 | 25 | 23 | 155 | 240 | 206 | 231 | 79 | 51 | 44 | 135 | 121 | 215 | 116 |

| ZBED2 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 382 | 77 | 335 | 63 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 399 | 90 | 352 | 72 |

| Sample 1 (female donor) | Sample 2 (male donor) | |||||||||||||

| Genes | 0 | 4h | 24h | 4h+ | 24h+ | 4h++ | 24h++ | 0 | 4h | 24h | 4h+ | 24h+ | 4h++ | 24h++ |

| ACTB | 2401 | 3356 | 1950 | 9080 | 3493 | 7386 | 3557 | 2437 | 3577 | 2066 | 9855 | 3268 | 8597 | 3553 |

| GAPDH | 776 | 726 | 849 | 6806 | 1793 | 6284 | 1520 | 997 | 1355 | 1141 | 6214 | 1674 | 6341 | 1455 |

| RPL10 | 1823 | 1224 | 1499 | 850 | 1141 | 808 | 1164 | 2310 | 1592 | 1793 | 1025 | 1349 | 1003 | 1437 |

| RPL15 | 1314 | 971 | 1008 | 1024 | 877 | 927 | 899 | 1495 | 1156 | 1071 | 1058 | 937 | 1026 | 947 |

| B2M | 17666 | 23446 | 16733 | 16757 | 20824 | 15869 | 19112 | 17382 | 25027 | 15980 | 18800 | 18743 | 17546 | 17220 |

| Sample 1 (female donor) | Sample 2 (male donor) | |||||||||||||

| Genes | 0 | 4h | 24h | 4h+ | 24h+ | 4h++ | 24h++ | 0 | 4h | 24h | 4h+ | 24h+ | 4h++ | 24h++ |

| SLC1A5 | 6 | 20 | 22 | 409 | 323 | 422 | 316 | 6 | 18 | 15 | 464 | 246 | 430 | 227 |

| SLC16A1 | 11 | 14 | 18 | 65 | 103 | 68 | 98 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 56 | 68 | 55 | 58 |

| SLC25A5 | 202 | 141 | 172 | 675 | 299 | 640 | 274 | 224 | 162 | 164 | 613 | 265 | 553 | 227 |

| SLC25A10 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 50 | 4 | 41 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 43 | 3 | 33 | 4 |

| SLC29A1 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 143 | 69 | 135 | 65 | 0.6 | 7 | 1 | 118 | 39 | 106 | 33 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).