1. Introduction

Physics explains matter and energy with extraordinary precision, yet remains silent on phenomena central to life and intelligence: knowledge and mind—the apparent goal-directedness of living systems. Why is there such an explanatory gap between our fundamental theories’ success in predicting planetary orbits and their failure to explain the adaptive, goal-directed behavior of organisms or intelligent machines?

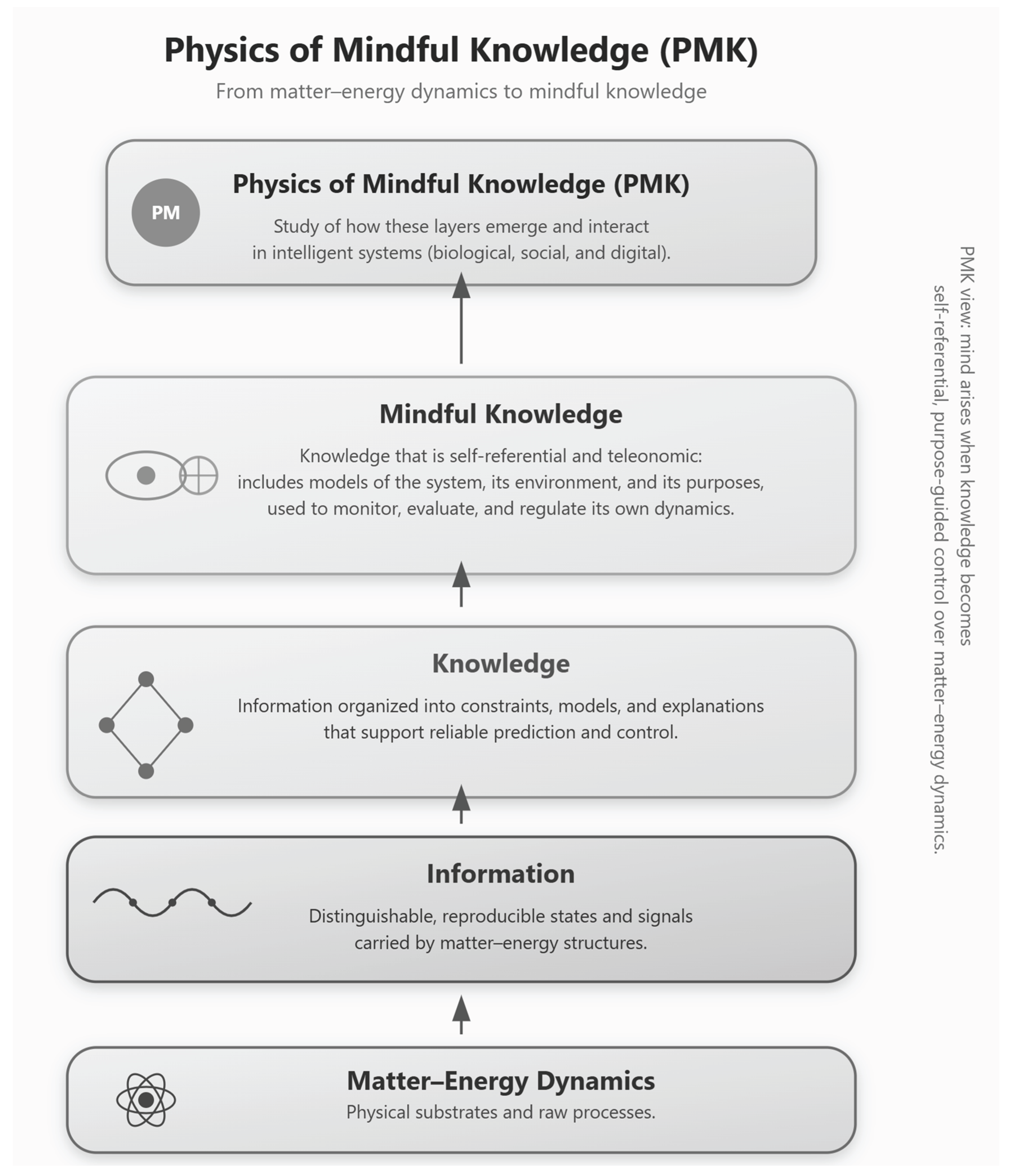

This gap is not trivial. Without a physics of knowledge and mind, we lack a principled foundation for explaining and engineering systems that maintain coherence, adapt to change, and act with purpose. Teleonomy—the ability to pursue goals and preserve metastability—is essential for understanding resilience in biology and for designing trustworthy AI. Existing approaches fall short: microphysical theories seek exotic substrates, metaphysical proposals abandon empirical testability, and process philosophies, while conceptually rich, lack a formal, computable language to operationalize their insights. We define PMK as the study of how physical systems embody, monitor, and regulate knowledge in ways that preserve coherence, purpose, and teleonomic integrity.

More precisely, the problem we target is this: current physical theory provides no general account of how knowledge-bearing structures can have causal efficacy. Given a complete microphysical description of a system and its environment, there is no principled way to derive when and how encoded knowledge will constrain trajectories, stabilize metastable states, or generate teleonomic behavior. The Physics of Mindful Knowledge (PMK) is proposed as a candidate framework to fill this gap, by treating instantiated knowledge structures as constraint-bearing organization within physical law.

Our contribution is not to rediscover this problem but to propose a formal, testable, and engineerable bridge: the Physics of Mindful Knowledge (PMK). PMK treats knowledge—not as an epiphenomenon—but as a causal constraint embedded in physical systems. Building on Burgin’s General Theory of Information (GTI), the Burgin–Mikkilineni Thesis (BMT), and Deutsch’s epistemology we show how epistemic structures stabilize metastability and enable teleonomy.

In earlier work in this journal, Burgin and Mikkilineni [

1] analyzed Landauer’s slogan “information is physical” within the General Theory of Information and argued that, strictly speaking, information and knowledge belong to the world of structures, while their concrete physical and mental carriers obey the usual laws of matter and energy. On that view, what is “physical” about information is the representation and the carrier, not information as such. Knowledge, in the strict GTI sense, is a network of knowledge structures that is always realized in such carriers (books, brains, digital memories, and so on). In this paper, when we speak informally of “knowledge being physical,” we therefore mean that knowledge is always instantiated as constraint-bearing organization in physical and/or mental substrates, and it is this instantiated organization that we treat as a causal resource.

We must clarify our terms. When we speak of "mind" in this context, we are not, for the purposes of this paper, addressing the "hard problem" of subjective experience or consciousness. We define "mind" in a functional, naturalistic sense: it is the process of modeling and anticipation that enables a system to act with apparent purpose to maintain its own coherence and achieve goals.

In asking this question, we are keenly aware that we are not the first. As physicists and engineers, we are, in many respects, "late-comers to the party." A vast and deep literature on this exact subject exists in fields outside of physics [

2], most notably in process philosophy [

3,

4,

5], complex systems theory [

6,

7,

8,

9], and biosemiotics and generative causation [

10,

11,

12].” These thinkers have long and rigorously argued for the need to incorporate information, meaning, and process into our fundamental theories of the natural world.

The central challenge, we argue, has not been a lack of philosophical insight but the absence of a computable, physical language to operationalize these concepts. Our intended contribution is to offer this formal, testable, and engineerable bridge. The PMK framework is designed to connect the deep insights of these process and semiotic traditions to the practical fields of modern physics and artificial intelligence, providing a language where "knowledge" is no longer just a concept, but a causal, physical, and engineerable constraint.

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows:

Section 2 surveys existing work in physics, information theory, and theoretical biology; this section is primarily expository, summarizing established or widely discussed positions.

Section 3 then introduces the Physics of Mindful Knowledge (PMK) as a conceptual synthesis and proposal, not as an already established theory.

Section 4 compares PMK with alternative explanations of the “missing physics” problem, and

Section 5 outlines an engineering roadmap and testable signatures, using concrete Mindful Machine prototypes to suggest how the PMK hypothesis could be empirically constrained.

2. The Existing Debate in Physics

The explanatory gap we identified—the causal efficacy of knowledge and teleonomy—is not unaddressed. The problem has, in fact, been approached from several powerful, yet often non-interacting, perspectives. A successful framework must synthesize these disparate lines of inquiry.

2.1. The Microphysical / Substrate-Dependent Approach

Based on Gödel’s incompleteness theorems, Roger Penrose ruled out computational sufficiency: human mathematical insight, he claimed, cannot be reduced to formal rule-following [

13]. To ground this non-computability in physics, Penrose introduced the concept of Objective Reduction (OR)—a hypothesized collapse of the quantum state driven by gravitational effects at the Planck scale. Together with Stuart Hameroff, [

14] he developed the Orch-OR model, which proposes that neuronal microtubules act as orchestrators of such non-computable collapses. Conscious experience, in this view, arises from orchestrated episodes of quantum gravitational collapse inside neurons.

While Orch-OR boldly asserts that consciousness depends on new physics, the theory remains speculative. Critics have noted that decoherence times in warm, wet brains are too short to preserve quantum coherence [

15]. Empirical evidence for microtubule-level quantum computation remains limited, and the link to consciousness is untested. Nevertheless, Orch-OR illustrates a broader theme: that physics as currently formulated may be missing a layer critical to explaining the mind.

However, the search for a specific, non-computable substrate continues. Recent research has proposed other candidates. Work by Adamatzky [

16], Schumann [

17,

18], and others, for instance, suggests that actin filaments and even fungal networks could act as "Turing automata with oracles," capable of solving non-computable functions. This line of inquiry is promising. However, it remains focused on what substrate mind is made of. We argue this focus may be misplaced. The problem may not be the substrate, but the architecture. A theory of knowledge should be substrate-independent, capable of explaining a "mindful" process whether it runs on neurons, actin filaments, or silicon.

2.2. Rickles and the Ontological Limits of Physics

A second line of work, represented by Dean Rickles [

19], approaches these issues as a philosopher of physics who examines how our best physical theories, especially in quantum gravity and related domains, strain naive ontological categories. His focus is not to propose a mind-first metaphysics, but to show that the formal content of physics already challenges simple pictures of space, time, and matter. In that sense, Rickles is diagnosing an ontological gap between what our theories say and the conceptual resources we have for understanding phenomena such as mind, information, and organization. This resonates with earlier proposals such as Wheeler’s “It from Bit” [

20] which reframe matter as emergent from deeper informational or implicate processes.

The strength of this line of work lies not in a rejection of physics, but in its willingness to question simple materialism and to take seriously the way physical theories themselves point beyond a picture of reality as “local objects in empty space.” For our purposes, we read Rickles as exposing an “ontological gap” between the formal content of physics and the categories we use to describe mind, information, and organization. The Physics of Mindful Knowledge can be seen as one possible response to that gap: rather than appeal to non-physical substances, we propose to make knowledge-bearing constraints explicit components of the physical ontology.

2.3. The Process & Semiotic Foundation

The entire discussion of information and meaning in nature has a deep, rich history outside of 20th-century physics. Process philosophy, championed by thinkers like Bergson [

3], Whitehead [

5], and more recently Kauffman [

4], argues that reality is not composed of static "things" but of dynamic "processes." In this view, constraints and relations are just as fundamental as matter and energy.

Complementing this is the field of biosemiotics, founded on the work of Charles Sanders Peirce [

2]. Peirce argued that all processes of meaning (semiosis) are fundamentally triadic: a relation between a Sign (or representamen), an Object, and an Interpretant (the effect or "meaning" produced). This tradition, we believe, has the correct philosophical orientation. It understands that mind is a process and that meaning is relational. Its primary historical limitation, however, has been the lack of a formal, computable, and engineerable language to connect these profound philosophical insights to the mathematics of physics and the architecture of computation.

2.4. The Informational-Biological Validation

Finally, a body of work in theoretical biology and cognitive science, especially Terrence Deacon’s Incomplete Nature [

21], treats life and mind as emerging from thermodynamic and informational constraints rather than from any new substance. Deacon, a biological anthropologist and cognitive scientist, argues that so-called “absential” phenomena—information, value, purpose—can be understood in purely naturalistic terms as higher-order constraints on physical processes, organized into nested teleodynamic hierarchies. This provides an explicitly constraint-based account of how purposive behaviour and mindedness can arise within physics, without invoking dualism.

Even more strikingly, Michael Levin's work on "scale-invariant cognition" demonstrates this process in action. Levin has shown that bioelectric fields in living tissues function as an informational layer, a "knowledge-bearing constraint" that stores the "memory" of a correct body plan [

22]. This informational layer governs the behavior of the underlying cells, enabling stunning displays of teleonomy, such as the regeneration of a planarian's head on a different part of its body.

2.5. A Fragmented Landscape

It is important to distinguish PMK from both Rickles’ stance and more radical mind-first proposals such as Hoffman’s [

23]. Rickles diagnoses an ontological gap created by our best physical theories, but does not commit to a positive mind-first metaphysics. Hoffman, by contrast, argues that conscious agents and their experiences are ontologically primary, and that the physical world is a kind of interface constructed by those agents. PMK adopts a more conservative position. It remains naturalistic and broadly physicalist, but extends the ontology of physics to include knowledge-bearing constraints as real, testable components of physical organization. In this sense we treat Rickles’ work as identifying the problem, Hoffman’s work as one radical metaphysical response, and PMK as a naturalistic, engineerable attempt to resolve the gap without abandoning empirical testability.

This survey reveals a fragmented landscape. We have:

Substrate-Hunters (Penrose, Adamatzky) looking for a "magic" material.

Metaphysical revisions and interpretations of physics — ranging from mind-first or radically modified ontologies (e.g., Hoffman) to careful analyses of the ontological implications of existing physical theories (e.g., Rickles).

Process Philosophers & Semioticians (Peirce, Whitehead) with the right relational philosophy but lacking a formal, computable framework.

Constraint-based and bioelectric theorists in biology and cognitive science (Deacon [

21], Levin [

22]) who emphasize information, constraints, and multi-scale control as central to life and teleonomy, but who do not yet provide a universal, engineerable architecture.

A synthesis is urgently needed. The Physics of Mindful Knowledge (PMK), which we introduce in the next section, is proposed as this synthesis. It is a naturalistic framework that is philosophically grounded in the semiotic and process traditions, biologically validated by work like Levin's, and—critically—made formally computable and engineerable through the tools of GTI and BMT.

3. The Physics of Mindful Knowledge: A Formal Framework

The gap between microphysical laws and teleonomic organization concerns a missing level of description—a physics of organization—rather than an undiscovered microphysical interaction. Microphysics supplies the lawful substrate; organizational physics specifies how constraints (structures, knowledge) select and stabilize macro-dynamics within thermodynamic limits [

8].

The fragmented landscape described in

Section 2 reveals the need for a framework that is naturalistic (not metaphysical), substrate-independent (not microphysical), formally rigorous (unlike process philosophy alone), and empirically validated (like the phenomena in informational biology). The Physics of Mindful Knowledge (PMK), is proposed as this synthesis. PMK is a naturalistic framework where knowledge—defined as explanatory, predictive, and causal constraints—is a fundamental part of physical reality. This framework is built on two core components: Burgin's General Theory of Information (GTI) as its ontology and the Burgin-Mikkilineni Thesis (BMT) as its dynamics.

In PMK we use three existing strands of work as scaffolding rather than as completed foundations. General Theory of Information (GTI) supplies a formal ontology that treats information and knowledge as triadic carrier–content–recipient structures, which helps avoid the reification of abstract “information.” The structural machines of the Burgin–Mikkilineni thesis (BMT) provide a computational dynamic in which knowledge resides in evolving structure rather than in state alone. Deutsch’s constructor-theoretic and epistemological work motivates the idea that knowledge is a physical resource with characteristic causal roles, and that good explanations act as constraints on possible transformations. PMK does not depend on accepting these frameworks wholesale, but uses them to articulate what it means for knowledge-bearing constraints to be physically real.

The Physics of Mindful Knowledge (PMK) builds directly on GTI. Information and knowledge are structural, but they always have representations and carriers; PMK focuses on those physically instantiated knowledge structures that act as constraints on system dynamics. When we say that “knowledge is physical” in the PMK framework, we do not introduce a new substance beyond matter and energy; rather, we claim that knowledge, when instantiated, appears as counterfactual-supporting constraint structures that narrow a system’s accessible state space, stabilize certain trajectories, and enable teleonomic, survival-relevant behavior. In this sense, knowledge has a physical mode of existence without ceasing to be structural in the GTI sense.

Physics of Mindful Knowledge (PMK) studies how knowledge-bearing structures—in biological, social, or digital systems—are physically realized in matter–energy substrates and how they constrain system dynamics.

By mindful, we mean that these knowledge processes are not merely reactive mappings but self-referential and purpose-laden: the system maintains models of itself and its environment, evaluates its own performance against goals and norms, and modifies its behavior accordingly.

Thus, PMK treats mind as a particular regime of organization within physical systems: a regime in which knowledge structures include models of the system’s own state, capabilities, and purposes, and are used to regulate ongoing processes. This links epistemic and ontological structures, reframing knowledge and mind as general physical phenomena—not human-exclusive attributes.

3.1. GTI as Formal Semiotics: A Solution to Reification

The most difficult challenge, as noted by critics, is the "reification of constraints." How can information be causal without becoming a "third substance" alongside matter and energy? The solution has existed for over a century, first in biosemiotics and now in information theory. Charles Sanders Peirce defined a "sign" (the carrier of meaning) as an irreducible triadic relation between an Object, a Representamen (the sign itself), and an Interpretant (the effect or meaning) [

2].

Generations later, Mark Burgin’s General Theory of Information (GTI) covered in four books [

24,

25,

26,

27] provides the formal, mathematical, and computable specification of this same semiotic process. GTI defines information not as a thing, but as a triadic relation between:

The Carrier: The physical substrate or structure (matter/energy).

The Content: The "knowledge" or constraint (the form or absence that makes a difference, as in Deacon's work [

21]).

The Recipient: The system that "reads" or is affected by the content, generating the "Interpretant."

This triadic model is our core defense against reification. Information has no existence apart from its embedding in organizational structures. The "knowledge-bearing constraint" (the content) is not an independent entity. It is immanent in its physical carrier and only exerts causal force by being interpreted by a recipient. A simple funnel's shape is a constraint that is causal, but it is not a "third substance" alongside the plastic (carrier) and the water (recipient). GTI is the formal language for this immanent, relational causation. It is the physical instantiation of biosemiotics.

In this paper we use Physics of Mindful Knowledge (PMK) to name a program that studies how knowledge-bearing structures are physically realized and how they constrain system dynamics. By knowledge we mean structures that encode models, explanations, or rules with predictive and control power. By mind we mean the process of modeling and anticipation that enables a system to act with apparent purpose, maintain its own coherence, and pursue goals. We call a regime mindful when these knowledge processes are self-referential and purpose-laden: the system maintains models of itself and its environment, evaluates its performance against goals and norms, and modifies its own behavior accordingly

The central claim of PMK is therefore not that knowledge is a new primitive alongside mass or energy, but that knowledge-bearing structures, when instantiated in physical and mental substrates, act as constraint-bearing organization that systematically shapes system trajectories. In line with the General Theory of Information, we treat knowledge as a structural resource with physical and mental carriers; PMK adds the claim that these instantiated constraint structures play a distinctive, engineerable role in complementing mass–energy in the dynamics of living and artificial systems.

3.2. Structural Machines and the Burgin–Mikkilineni Thesis

If GTI provides the ontology of knowledge, how does it act? How does it compute and evolve? The "substrate-dependent" approaches (Penrose, Adamatzky) are correct that the answer must be "non-computable" in the classical sense [

13,

16]. Their search for exotic physics, however, misses the formal point made by Alan Turing himself.

In 1939, Turing proposed "Systems of Logic Based on Ordinals" [

28], which introduced the "oracle machine." An oracle machine is a standard Turing machine augmented with a "black box"—an oracle—that can solve a non-computable problem (like the Halting Problem) in a single step. Turing introduced the oracle to define the very limit of algorithmic computation. Later, there were many extensions of the oracles to extend the original idea [

29,

30].

Here, we propose that the Burgin-Mikkilineni Thesis (BMT) [

31,

32] provides the architectural basis for a physical oracle. The BMT redefines computation:

In a "structural machine" [

31,

32,

33] built on the BMT, the "knowledge" is not a static program in the machine; it is the machine's architecture. The computation is the continuous, self-organizing evolution of that architecture. This structural process acts as a physical oracle. It does not "compute" an answer algorithmically; its self-organizing dynamics embody the answer as a stable, structural state. This provides a naturalistic, engineerable path to the "non-computable" functions that Penrose, Schumann, and others seek in exotic substrates [

13,

17]. It is a new computational paradigm.

3.3. Deutsch’s Epistemology: Knowledge as a Physical Constructor

While GTI provides the ontology for information and BMT provides the computational dynamics, the epistemology of David Deutsch provides the physical and philosophical justification for our central claim: that knowledge is a real and potent causal force. Deutsch, in The Beginning of Infinity and his work on Constructor Theory, argues that the laws of physics are not just about what happens (dynamics) but about what can be made to happen (which transformations are possible vs. impossible) [

34]. The entities that cause these transformations are "constructors.”

3.3.1. Knowledge as "Hard-to-Vary Explanations"

Deutsch redefines knowledge. It is not "justified true belief," but rather "hard-to-vary explanations." A good explanation (a good theory) is one whose parts are so interconnected and constrained by evidence that you cannot easily change one part without destroying the whole. This directly parallels our framework:

A Mindful Machine's "schema" or "digital genome" is a hard-to-vary explanation of its purpose and its environment, encoded in a physical structure.

3.3.2. Knowledge as the Ultimate Constructor

For Deutsch, knowledge is not abstract; it is a type of constructor. A simple constructor, like a catalyst, can facilitate a transformation, but it doesn't know anything. A system with knowledge (like a 3D printer with a blueprint, or a human) is a universal constructor. It can cause an indefinitely wide range of transformations. Deutsch argues that knowledge is, in fact, the most significant causal force in the universe [

34]. It is the only thing that can bend the physical world to its will, creating structures and processes (like computers or cities) that would be statistically impossible to arise by "chance and necessity" alone [

36].

3.3.3. The BMT as an Engineered Constructor

This is where Deutsch's epistemology provides profound support for our paper's engineering thesis:

The system's ability to self-repair and maintain its coherence—as we propose to test with the Recovery Energy metric—is the very definition of a true constructor: a system that persists in its function (its knowledge) while causing transformations in its environment.

3.4. Folds as Coherence Structures (After Hill’s Fold Theory)

Fold Theory [

35], in its current form, is a speculative but promising proposal that treats certain coherence-bearing attractors in state space as “folds” that concentrate and protect structure. For the purposes of this paper we do not rely on its technical development and do not assume its conjectured connections to quantum gravity. We use only its intuitive notion of folds as dynamic coherence structures that can carry and stabilize knowledge. None of the experimental scenarios in

Section 5 depends on Fold Theory, and PMK can be developed without it. We include it here as a heuristic way to talk about the emergence and maintenance of organized regimes in complex dynamics.

A key challenge is to specify the dynamic process by which epistemic structures (knowledge) emerge from and subsequently "fold back" to govern their ontological (physical) substrate. This is the problem of emergence, organizational closure, and top-down causation.

If the General Theory of Information (GTI) provides the ontology (defining information as a triadic relation of Carrier/ontological and Content/epistemic), and the Structural Machine Architecture (SMA) is the engineered system, then Fold Theory [

35] provides the physics or formal language to describe what this information does. Fold Theory is a mathematical framework designed to model how systems "fold" to create coherence. We can use the analogy of a whirlpool:

Ontological Substrate (Carrier): The flow of water (the physical dynamics).

Epistemic Structure (Content): A stable whirlpool pattern that emerges from the water's own dynamics. This "fold" is not a new substance but a coherent, self-maintaining pattern.

Causal Efficacy: This emergent "fold" (the whirlpool) now exerts top-down causal power, governing the behavior of the individual water molecules and pulling them into its stable pattern.

Formally, in dynamical-systems terms we can think of a “fold” as a self-maintaining, coherence-bearing subset of a system’s state space together with its basin of attraction: trajectories entering that basin are drawn into a structured, low-entropy pattern that then constrains subsequent flows. This is the sense in which folds serve as carriers of organization and top-down causal influence.

Rather than claiming to have a completed formalism, we take Fold Theory as an exploratory program that aims to provide categorical and geometric tools for describing such “whirlpools of coherence.” In this paper we do not rely on those technical details; we use only the intuitive notion of folds as dynamically sustained coherence structures that might eventually be given a precise Fold-Theoretic treatment, and we show how such structures could integrate the ontological substrate of GTI with the dynamic, teleonomic function of the Burgin–Mikkilineni Thesis.

In summary, Deutsch's epistemology provides the physical and philosophical argument why we must treat knowledge as a causal, structural entity. It shifts physics from a "physics of dynamics" to a "physics of constraints and possibility." Our PMK framework, with its synthesis of GTI, BMT, and Fold Theory, provides the formal language and the engineerable architecture to build these knowledge-based constructors.

3.5. Metastability and Teleonomy

A unifying concept across GTI, BMT and Fold Theory is that of metastability. Knowledge-bearing systems remain poised between equilibrium and chaos, able to flexibly adapt without disintegration. Teleonomy—the apparent goal-directedness of living systems—can be reframed in this context as the causal efficacy of knowledge constraints. This reframing has profound implications: teleonomy is not a mystical property of life, nor reducible to blind statistical regularities, but a manifestation of physics extended to include knowledge as an organizing principle. The Physics of Mindful Knowledge therefore provides a naturalistic account of mind and purpose without recourse to exotic microphysics or metaphysical rupture.

When you combine GTI (knowledge as a triadic relation) with BMT (computation as structural evolution), you get the function of PMK: to stabilize metastable coherence and enable teleonomy. A living system, like those described by Deacon and Levin [

21,

22], is a far-from-equilibrium system. It is "metastable"—it could collapse into thermodynamic equilibrium (death) at any moment. What prevents this collapse? The Answer: A nested set of knowledge-bearing constraints (encoded via GTI) that compute (via BMT) to actively maintain the system's coherence.

Figure 1 shows a Formal Bridge from Foundational Insights to Testable Engineering. The layered figure of the Structural Machine (Mindful Machine Architecture) presents the three tiers—Physical Substrate, Knowledge Constraints, and Teleonomy & Mindful Systems.

Figure 1.

Layered Mindful Machine Architecture.

Figure 1.

Layered Mindful Machine Architecture.

3.6. Summary: What PMK Suggests

For clarity, we summarize the core commitments of PMK.

C1. Physical realization. Information and knowledge are structural, but in practice they always have material or mental carriers. PMK focuses on those instantiated constraint structures that narrow a system’s accessible state space and stabilize its trajectories.

C2. Mindful regime. A system is mindful in the PMK sense if and only if it (i) encodes prior knowledge in its structure, (ii) maintains models of itself and its environment, and (iii) uses these models to monitor and regulate its own dynamics in order to preserve a characteristic identity and purpose.

C3. Causal role. Knowledge-bearing constraints have measurable causal signatures, such as reduced recovery effort and increased coherence under perturbations, that cannot be matched by functionally equivalent but purely algorithmic systems.

C4. Testability. PMK is not an additional substance, but a hypothesis about organization. It is therefore testable by comparative experiments between systems that differ only in whether they implement PMK-style knowledge structures

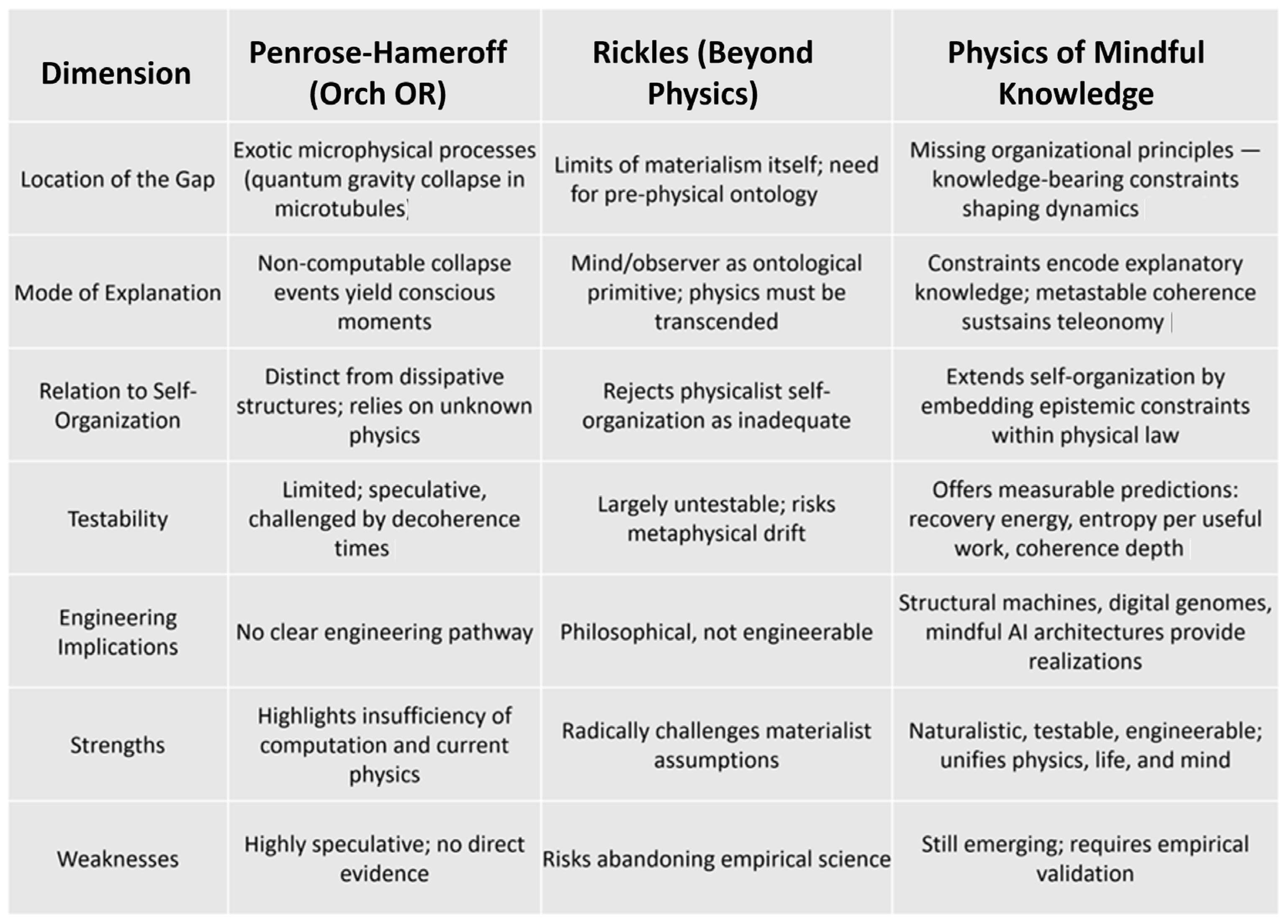

4. Comparative Framework

The debate over “missing physics” reveals three distinct loci of explanation: microphysics (Penrose–Hameroff), metaphysics (Rickles), and knowledge constraints (Physics of Mindful Knowledge). Each identifies a real gap, but their solutions diverge in explanatory scope, testability, and engineering implications. The comparative framework developed in this section should therefore be read as an engineering and conceptual roadmap for future work, not as a set of already validated empirical results.

Table 1.

Three explanations for the gap in physics, using eight dimensions.

Table 1.

Three explanations for the gap in physics, using eight dimensions.

5. From Theory to Testability

A central claim of this paper is that the Physics of Mindful Knowledge (PMK), unlike metaphysical or purely substrate-dependent approaches, is "empirically testable and engineerable." This section provides a detailed elaboration. The "dynamical reciprocity between structure, model, and process" is specified by the Burgin-Mikkilineni Thesis (BMT) and its embodiment in structural machines [

30,

31,

32]. The metrics are not pre-supposed; they are the direct, measurable consequences of comparing this BMT model against the reigning algorithmic (Turing) paradigm. To demonstrate this, we will "work out" our proposed testable signature using concrete implementations [

31,

32]. Metaphysical revisions and interpretations of physics — ranging from mind-first or radically modified ontologies (e.g., Hoffman) to careful analyses of the ontological implications of existing physical theories (e.g., Rickles).

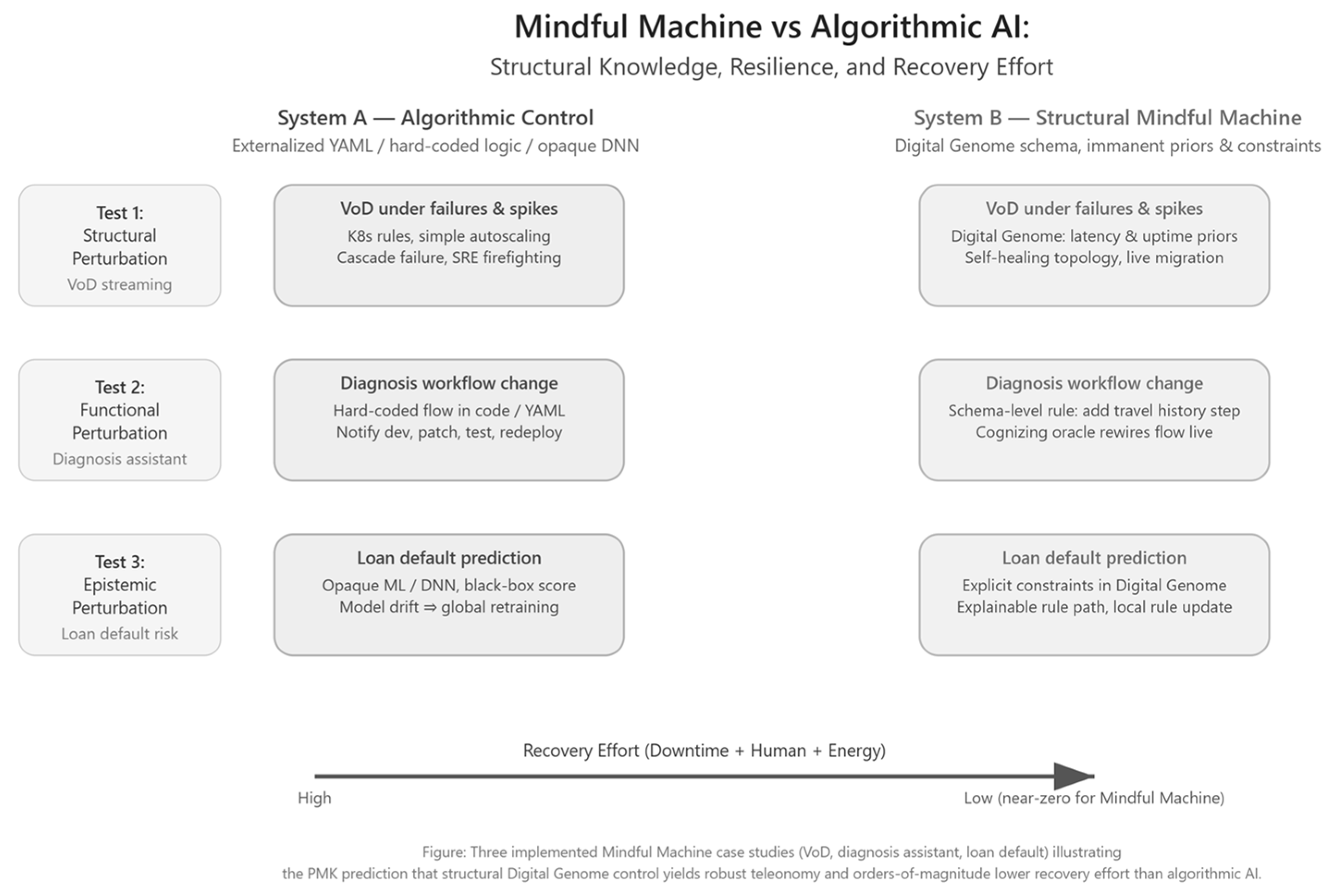

PMK perspective: Mind arises when knowledge becomes self-referential and teleonomic—regulating matter–energy dynamics through explanatory, purpose-guided constraints.

Figure 2.

Testing Models.

Figure 2.

Testing Models.

5.1. A Concrete Testable Metric: Resilience and Recovery Effort

In prior implementations of structural machines, we have observed that controllers which embed explicit knowledge-bearing constraints can recover from disruptions with less operator intervention and lower reconfiguration cost than comparable purely algorithmic controllers. The experiments we propose are designed to quantify this difference as a measure of Recovery Effort, in terms of energy, compute, and human operator time. PMK predicts that, under matched structural, functional, and epistemic perturbations, a PMK-style structural controller will exhibit systematically lower Recovery Effort and more stable teleonomic behavior than a controller that relies only on fixed algorithms and parameter updates. If such an advantage is not observed in carefully controlled comparisons, the central engineering claim of PMK would be falsified.

5.2. Experimental Protocol & Comparative Tasks

We define our two systems and test them against real-world implementation challenges.

System A (Algorithmic Control): A state-of-the-art implementation, typically using cloud-native microservices (managed by Kubernetes or other software structures) for application logic and a Deep Neural Network (DNN) for predictive logic. Its "knowledge" is brittle, existing externally in static YAML files, hard-coded workflows, or the opaque, static weights of a trained model.

System B (Structural Control): A structural machine (the "Mindful Machine") built on the BMT. Its "knowledge" is an immanent, machine-readable "Digital Genome" that defines the intent, priors, and constraints of the system. The machine is its own architecture, which it evolves dynamically.

Test Case 1: Video on Demand (VoD) — Structural Perturbation

Task: Both systems are instantiated to deliver a VoD streaming service.

Perturbation (Structural Damage): The system is subjected to sudden, unpredictable hardware failures and massive, simultaneous user demand spikes, testing auto-failover, self-scaling, and live migration.

-

Falsifiable Prediction 1 (Resilience & Effort):

- ○

System A (Algorithmic) will react based on pre-programmed rules (e.g., Kubernetes Horizontal Pod Autoscaler). These rules are simple, reactive, and slow. A cascade failure or a novel scaling pattern will overwhelm the rules, causing service failure (high downtime) and requiring high-effort human SRE (Site Reliability Engineer) intervention to diagnose and repair.

- ○

System B (Structural), in contrast, is its knowledge. The "Digital Genome" defines the intent (e.g., "maintain 5ms latency and 99.999% uptime"). It will autonomously and proactively self-organize and repair, dynamically re-routing workflows and re-instantiating processes on healthy nodes. Its Recovery Effort (in downtime and human intervention) will be near zero, while its "energy" cost is simply the minimal computational overhead of its own self-organization.

Test Case 2: Digital Assistant for Diagnosis — Functional Perturbation

Task: Both systems execute a digital assistant workflow for early medical diagnosis.

Perturbation (Functional Damage): A new healthcare regulation or medical best-practice is introduced, changing the required workflow (e.g., "a 'Travel History' check must now be added before the 'Symptom Check'").

-

Falsifiable Prediction 2 (Teleonomy & Adaptation):

- ○

System A (Algorithmic) will exhibit extreme brittleness. The workflow is hard-coded by a developer. To adapt, a human must be notified, re-write the application code, run tests, and manage a complex redeployment. The system is "ignorant" and cannot adapt.

- ○

System B (Structural) will exhibit robust teleonomy. The "Digital Genome" (the schema) is simply updated with the new constraint. The machine itself, acting as a "cognizing oracle," instantly dynamically changes its own workflow structure to comply with the new rule, with zero downtime. This is directly analogous to the hexapod "discovering" a new limping gait; System B solves the non-algorithmic problem of "what is the correct workflow now?"

Test Case 3: Loan Default Prediction — Epistemic Perturbation (ML vs. PMK)

Task: Both systems are used to approve or deny loan applications based on default risk.

Perturbation (The "Damage" of Opacity): This tests the fundamental difference between ML-based knowledge and structural knowledge. The systems are evaluated on explainability and adaptability to model drift.

-

Falsifiable Prediction 3 (Explainability & Coherence):

- ○

System A (ML/DNN), upon being "damaged" (i.e., making a bad or biased decision), is functionally "ignorant" and "brittle." It is a "black box" and cannot provide a "hard-to-vary explanation" (per Deutsch [

34]) for its decision. If its model drifts due to new market conditions, it must initiate a massive, high-energy, global retraining process, essentially re-learning "from scratch."

- ○

System B (Structural) is its knowledge. It makes a decision by following the explicit constraints in its "Digital Genome" (e.g., "debt-to-income ratio," "credit history," "regulatory rules"). It can explain its decision perfectly by providing the exact structural path it took. If a rule changes, it adapts dynamically (as in Test Case 2) without a high-energy "retraining."

5.3. Summary of Predictions

This single, unified framework demonstrates that the PMK is not a "stub" or an "opinion piece." It is a testable engineering paradigm. The implementations [

33] show that a structural machine (System B) exhibits robust, teleonomic behavior and near-zero recovery effort, while the current algorithmic paradigm (System A) remains brittle, ignorant, and requires massive external (human or energy) effort to adapt or repair. The other metrics we proposed, such as Entropy per Useful Work and Coherence Depth, can be similarly mapped to these real-world applications.

6. Implications

The Physics of Mindful Knowledge carries implications across three domains: physics, AI, and philosophy. For physics, it extends physics with constraint-based ontology. For engineering and AI, it provides a roadmap for mindful machines and structural machines that embody explanatory knowledge. For philosophy, it offers a naturalist alternative to dualism and eliminativism, grounding teleonomy in causal constraints. This framework suggests a research program that bridges physics, AI, and philosophy, and opens pathways to testable science of knowledge.

In AI, the current drive toward a ‘world model’ aligns naturally with the emerging view of knowledge as a causal, structural constraint rather than an ethereal epiphenomenon. In LeCun’s architecture [

37], mind is an autonomous learning system with a world model; the model is a learned, internal predictive structure that captures the regularities and causal dynamics of the environment. Its purpose is not passive representation but active constraint: it restricts the space of plausible futures, guides action selection, and enables planning without exhaustive trial-and-error. In this sense, the world model functions like a computational riverbank, shaping behavior by embedding learned structure within the system itself. Intelligent behavior emerges from the system’s ability to simulate, anticipate, and optimize actions under these internal constraints.

PMK generalizes this idea beyond computation, reframing knowledge as a physically instantiated constraint that channels the flow of matter, energy, and processes, much like a topological structure that governs far-from-equilibrium dynamics. Building on General Theory of Information, Fold Theory, and Deutsch’s epistemology, this framework treats knowledge as a causally efficacious substrate capable of stabilizing metastable states and generating teleonomic behavior. LeCun’s world model can thus be seen as a specific instantiation of this broader ontology: an engineered informational constraint that acquires causal power through predictive coherence. We extend the concept further by introducing measurable physical signatures—such as coherence depth and recovery energy—and by emphasizing metacognition, self-maintenance, and structural evolution. In this synthesis, world models provide the computational skeleton, while the Physics of Mindful Knowledge supplies the ontological and dynamical grounding for machines capable not merely of prediction, but of genuine resilience, self-correction, and mindful adaptation.

PMK provides the theoretical backdrop for the Mindful Machine Architecture (MMA). In PMK, a system is mindful when it (i) encodes prior knowledge in its structure, (ii) continuously senses and evaluates its state and context, and (iii) uses that knowledge to adaptively preserve its identity and purpose. The MMA instantiates this regime: the

Digital Genome encodes priors and constraints,

AMOS [

32] governs self-maintenance, and

Cognizing Oracles or large language models update contextual knowledge to steer control.

7. Conclusions

This paper began by identifying a specific explanatory gap in current physical theories: the causal efficacy of knowledge and teleonomy. In addressing this gap, we attempted to prove that our proposal is not merely a "brief draft" or "opinion piece," but a substantive, testable, and rigorously-grounded scientific framework.

We have framed our argument, not as a new "discovery," but as a necessary formal and engineerable bridge to a deep body of existing thought. We demonstrated that the philosophical foundations of our work lie in fields like biosemiotics [

10,

11] and process philosophy [

3,

4,

5], which had correctly identified the relational, process-based nature of reality.

We then proposed the Physics of Mindful Knowledge (PMK) as the missing formal synthesis, built on three interconnected pillars that provide the scaffolding for the BMT:

A Formal Ontology (GTI): We showed that Burgin's General Theory of Information [

24,

25,

26,

27] is a formal, computable instantiation of Peirce's triadic semiotics [

2]. This solves the ontological problem of "reification" by defining knowledge as an immanent, relational constraint—a "content" (epistemic) that cannot exist apart from its "carrier" (ontological).

A Physical Justification (Deutsch): We grounded our framework in Deutsch's epistemology [

34], which defines knowledge as a physical "constructor" in the form of "hard-to-vary explanations." This provides the physical justification for treating our "knowledge-bearing constraints" as real, causal entities.

A Computable Architecture (BMT): We argued that the Burgin-Mikkilineni Thesis (BMT) [

30,

31] provides the naturalistic and engineerable architecture for Turing's "Oracle Machine" [

27]. This "structural machine" (the implementations are called Mindful Machines [

33]) is the physical embodiment of a Deutsch-ian constructor, one that computes by evolving its own hard-to-vary structure, offering a substrate-independent solution to non-algorithmic computation.

A Formal Dynamic (Fold Theory): We identified Fold Theory [

35]—currently a self-archived preprint rather than a completed, peer-reviewed theory—as a promising candidate for a formal language of recursive coherence. In this paper, however, we use only its central intuition: that self-maintaining coherence structures can be treated as dynamically realized “folds” that carry organization and mediate top-down causal influence.

We further showed that this framework is not a mere abstraction. It is empirically validated by the "absential causation" described by Deacon [

21] and, most strikingly, by the "scale-invariant cognition" and robust teleonomy demonstrated in Levin's biological experiments [

22].

This 'physics of organization' is not without precedent. Karl Friston’s Free Energy Principle formalizes this by defining the organism as a statistical model that minimizes 'surprisal' to resist entropic decay, effectively treating the organism's structure as a physical prediction of its environment [

38]. Complementing this, Tom Froese and the enactive tradition argue that these constraints are not merely statistical but autopoietic, where the system’s goal-directedness arises from the precarious, self-generating nature of its own boundaries [

39]. Our PMK framework integrates these views: Friston provides the minimization calculus, Froese provides the autonomous dynamics, and the Burgin-Mikkilineni Thesis (BMT) provides the engineerable architecture to realize them in non-biological substrates.

Finally, we have demonstrated that the PMK is not a metaphysical proposal but a falsifiable engineering paradigm. By expanding our testable signatures into a detailed experimental protocol—Recovery Energy—we have provided a concrete, measurable, and falsifiable method for testing a structural, BMT-based controller against a traditional algorithmic one.

The implications are profound. The PMK framework suggests that matter, energy, and knowledge-bearing constraints (information) are an irreducible triad. It offers a new, non-binary, non-algorithmic model of computation—structural machines—that may be the key to building truly "mindful" artificial intelligence. By embedding epistemic constraints into physical law, the Physics of Mindful Knowledge unifies physics, life, and mind, offering a new, naturalistic, and powerfully predictive path forward.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, R.M; methodology, R.M, M.M..; “All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“Not applicable”

Informed Consent Statement

“Not applicable.”

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

One of the authors. R.M acknowledge Dr. Judith Lee, Director of the Center for Business Innovation for many discussions and support.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”.

References

- Burgin, M., & Mikkilineni, R. (2022). Is information physical and does it have mass? Information, 13(11), 540.

- Peirce, C. S. (1931–1958). Collected papers of Charles Sanders Peirce (Vols. 1–8; C. Hartshorne, P. Weiss, & A. W. Burks, Eds.). Harvard University Press.

- Bergson, H. (1998). Creative evolution (A. Mitchell, Trans.). Dover Publications. (Original work published 1907).

- Kauffman, S. A. (1993). The origins of order: Self-organization and selection in evolution. Oxford University Press.

- Whitehead, A. N. (1978). Process and reality: An essay in cosmology (D. R. Griffin & D. W. Sherburne, Eds.). The Free Press. (Original work published 1929).

- Holland, J. H. (1998). Emergence: From chaos to order. Oxford University Press.

- Maturana, H. R., & Varela, F. J. (1980). Autopoiesis and cognition: The realization of the living. D. Reidel Publishing Co.

- Nicolis, G., & Prigogine, I. (1977). Self-organization in nonequilibrium systems: From dissipative structures to order through fluctuations. Wiley.

- Prigogine, I., & Stengers, I. (1984). Order out of chaos: Man's new dialogue with nature. Bantam Books.

- Hoffmeyer, J. (2008). Biosemiotics: An examination into the signs of life and the life of signs. Scranton: University of Scranton Press.

- Bateson, G. (1972). Steps to an ecology of mind. University of Chicago Press.

- Blossfeld, HP. (2009). Causation as a Generative Process. The Elaboration of an Idea for the Social Sciences and an Application to an Analysis of an Interdependent Dynamic Social System. In: Engelhardt, H., Kohler, HP., Fürnkranz-Prskawetz, A. (eds) Causal Analysis in Population Studies. The Springer Series on Demographic Methods and Population Analysis, vol 23. Springer, Dordrecht. [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. (1989). The emperor’s new mind. Oxford University Press.

- Hameroff, S., & Penrose, R. (2014). Consciousness in the universe: A review of the ‘Orch OR’ theory. Physics of Life Reviews, 11(1), 39–78. [CrossRef]

- Tegmark, M. (2000). The importance of quantum decoherence in brain processes. Physical Review E, 61(4), 4194–4206.

- Adamatzky, A., & Gandia, A. (2022). Fungi anaesthesia. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 340. [CrossRef]

- Schumann, A. (2018). Decidable and undecidable arithmetic functions in actin filament networks. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics, 51(3), 034005. [CrossRef]

- Schumann, A., Adamatzky, A., Król, J., & Goles, E. (2024). Fungi as Turing automata with oracles. Royal Society Open Science, 11(10), 240768. [CrossRef]

- Rickles, D. (2016). The philosophy of physics. Polity.

- Wheeler, J. A. (1990). Information, physics, quantum: The search for links. In W. H. Zurek (Ed.), Complexity, entropy, and the physics of information (pp. 3–28). Addison-Wesley.

- Deacon, T. W. (2012). Incomplete nature: How mind emerged from matter. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Levin, M. (2021). Bioelectric signaling: Reprogrammable circuits underlying embryogenesis, regeneration, and cancer. Cell, 184(8), 1971–1989. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, D. D. (2019). The Case Against Reality: Why Evolution Hid the Truth from Our Eyes. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Burgin, M. (2010). Theory of information: Fundamentality, diversity and unification. World Scientific.

- Burgin, M. (2012). Structural reality. Nova Science Publishers.

- Burgin, M. (2011). Theory of named sets. Nova Science Publishers.

- Burgin, M. (2016). Theory of knowledge: Structures and processes. World Scientific.

- Turing, A. M. (1939). Systems of logic based on ordinals. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, s2-45(1), 161–228.

- Mikkilineni, R., Morana, G., & Burgin, M. (2015). Oracles in software networks: A new scientific and technological approach to designing self-managing distributed computing processes. In Proceedings of the 2015 European Conference on Software Architecture Workshops (ECSAW '15) (Article 11, pp. 1–8). Association for Computing Machinery. [CrossRef]

- Mikkilineni, R., Comparini, A., & Morana, G. (2012, June). The Turing O-Machine and the DIME Network Architecture: Injecting the architectural resiliency into distributed computing. In Turing-100 (pp. 239-251).

- Burgin, M., & Mikkilineni, R. (2021). On the autopoietic and cognitive behavior. EasyChair Preprint No. 6261, Version https://easychair.org/publications/preprint/tkjk.

- Mikkilineni, R. (2022b). Infusing autopoietic and cognitive behaviors into digital automata to improve their sentience, resilience, and intelligence. Big Data and Cognitive Computing, 6(1), 7. [CrossRef]

- Mikkilineni, R., Kelly, W. P., & Crawley, G. (2024). Digital genome and self-regulating distributed software applications with associative memory and event-driven history. Computers, 13(9), 220. [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, D. (2011). The beginning of infinity: Explanations that transform the world. Viking.

- Hill, S. L. (2025a). Fold Theory: A categorical framework for emergent spacetime and coherence [Preprint]. Academia.edu. https://www.academia.edu/130062788.

- Monod, J. (1971). Chance and necessity. Knopf.

- LeCun, Y. A Path Towards Autonomous Machine Intelligence; OpenReview Preprint, 2022.

- Friston, K. (2013). Life as we know it. Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 10(86), 20130475.

- Froese, T. (2023). Irruption theory: A novel conceptualization of the enactive account of motivated activity. Entropy, 25(5), 748.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).