1. Introduction

Contemporary physics offers unparalleled explanatory reach, from the unification of forces at high energies to the statistical mechanics of complex systems. Yet it struggles to accommodate phenomena central to human existence: mind, knowledge, and teleonomy. These domains, though rooted in the physical, seem to require explanatory resources not found in present formulations of physics. As Roger Penrose has argued, “consciousness is not algorithmic” and thus not capturable by any known computational or physical model (Penrose 1989; 1994).

Other thinkers, however, suggest that the problem is not one of exotic microphysics but of physics itself as a paradigm. Philosopher Dean Rickles has argued that the persistent failure to unify quantum mechanics and relativity points to a deeper “crisis of materialism,” requiring us to go beyond the physical to a pre-materialist ontology (Rickles 2025).

Between these poles lies a developing alternative: a Physics of Knowledge. This view, building on Mark Burgin’s General Theory of Information (Burgin 2010), David Deutsch’s epistemology of knowledge as “hard-to-vary explanations” (Deutsch 2011), and structural machine architectures proposed by Burgin and Mikkilineni (Burgin & Mikkilineni 2021), argues that what is missing in physics is not particles or metaphysics but constraints that encode and preserve knowledge. Knowledge-bearing structures, rather than being epiphenomenal, play a causal role in sustaining metastable, goal-directed organization far from equilibrium — a position foreshadowed in the work of Prigogine on dissipative structures (Prigogine 1977) and Haken’s Synergetics (Haken 1977), but extended here to explicitly epistemic dynamics.

This paper situates the Physics of Knowledge in relation to Penrose and Rickles, contrasting three visions of “missing physics”: microphysics, metaphysics, and knowledge constraints. We argue that the Physics of Knowledge offers a viable path forward because it remains naturalistic while also being empirically testable and engineerable..

2. The Existing Debate

Physics unifies phenomena across scales, yet mind, knowledge, and purpose like behavior remain poorly integrated within its explanatory scope. Competing responses attribute the gap to (i) exotic microphysics (e.g., Orch OR), (ii) beyond physical ontologies, or (iii) missing organizational principles. We advance the third option: knowledge bearing constraints are causal resources—alongside matter and energy—that shape trajectories of far from equilibrium systems and sustain metastable, goal consistent organization.

2.1. Penrose–Hameroff and the Microphysical Hypothesis

Roger Penrose’s argument against computational sufficiency rests on Gödel’s incompleteness theorems: human mathematical insight, he claims, cannot be reduced to formal rule-following (Penrose 1989). To ground this non-computability in physics, Penrose introduced the concept of Objective Reduction (OR) — a hypothesized collapse of the quantum state driven by gravitational effects at the Planck scale (Penrose 1994). Together with Stuart Hameroff, he developed the Orch-OR model, which proposes that neuronal microtubules act as orchestrators of such non-computable collapses (Hameroff & Penrose 1996). Conscious experience, on this view, arises from orchestrated episodes of quantum gravitational collapse inside neurons.

While Orch-OR boldly asserts that consciousness depends on new physics, the theory remains speculative. Critics have noted that decoherence times in warm, wet brains are too short to preserve quantum coherence (Tegmark 2000). Empirical evidence for microtubule-level quantum computation remains limited, and the link to consciousness is untested. Nevertheless, Orch-OR illustrates a broader theme: that physics as currently formulated may be missing a layer critical to explaining the mind.

2.2. Rickles and the Beyond-Physical Ontology

In a more radical vein, Dean Rickles argues that the failure of quantum gravity research reveals not just a technical gap but an ontological one. Physics, he claims, is bounded by the assumptions of materialism — assumptions that cannot accommodate mind or meaning (Rickles 2025). Rickles suggests that the next paradigm must go beyond the physical, re-centering the observer and mind as foundational rather than derivative. This resonates with earlier proposals such as Wheeler’s “It from Bit” (Wheeler 1990) and Bohm’s implicate order (Bohm 1980), both of which reframe matter as emergent from deeper informational or implicate processes.

The strength of this view lies in its willingness to question entrenched commitments. Yet its weakness is evident: it offers little in the way of testable hypotheses, risking a slide into metaphysics rather than extending physics. In contrast to Penrose’s microphysical exoticism, Rickles demands an ontological rupture — a move that risks abandoning the empirical anchor of physics..

2.3. Self-Organization and Its Limits

Between Penrose’s exotic microphysics and Rickles’s metaphysical reorientation lies a rich tradition of self-organization theory. Pioneered by Prigogine’s theory of dissipative structures (Prigogine 1977) and Haken’s Synergetics (Haken 1977), this literature shows how order can emerge spontaneously in far-from-equilibrium systems. Biological autopoiesis (Maturana & Varela 1980) extended this insight to living systems.

However, these approaches typically treat organization as an emergent statistical phenomenon, rather than explicitly grounding the causal role of knowledge. They demonstrate how order arises, but not how knowledge-bearing constraints stabilize metastable coherence or drive teleonomy. It is precisely here that the Physics of Knowledge seeks to intervene.

3. Physics of Knowledge: Core Premises

The gap between microphysical laws and teleonomic organization concerns a missing level of description—a physics of organization—rather than an undiscovered microphysical interaction. Microphysics supplies the lawful substrate; organizational physics specifies how constraints (structures, knowledge) select and stabilize macro-dynamics within thermodynamic limits (Haken, 1983; Friston, 2010; Moreno & Mossio, 2015).

3.1. Knowledge as Constraint

Traditional verification methods test correctness with respect to fixed inputs and expected outputs. Such methods break down in adaptive systems where goals, environments, and internal policies evolve. What is needed is a generalized notion of correctness—not syntactic equivalence but coherence: the preservation of logical, semantic, and ethical consistency across time. This leads to the General Theory of Epistemic Computation (GTEC), which defines computation as the continuous process of coherence maintenance among three domains:

The central claim of a Physics of Knowledge is that knowledge-bearing structures are not epiphenomenal but causal constraints within physical systems. In Mark Burgin’s General Theory of Information (GTI), information is defined not as an abstract quantity but as a triadic relation between a carrier, content, and recipient (Burgin 2010). This relational view implies that information has no existence apart from its embedding in organizational structures. Extending this logic, knowledge — understood as explanatory, hard-to-vary models in David Deutsch’s terms (Deutsch 2011) — can be seen as a higher-order constraint on system dynamics. Knowledge restricts the space of possible transformations, channeling processes toward goal-directed outcomes.

Unlike mere Shannon information, which is statistical, knowledge is counterfactual: it encodes not only what is, but what could or could not be otherwise. This property makes knowledge uniquely suited to stabilize metastable coherence in far-from-equilibrium systems, preventing collapse into entropy-driven attractors. Thus, knowledge-bearing constraints can be treated as a new kind of physical resource, shaping system trajectories in a way that complements energy and matter.

3.3. Structural Machines and the Burgin–Mikkilineni Thesis

A further elaboration is found in the Burgin–Mikkilineni Thesis (BMT) (Burgin & Mikkilineni 2021), which argues that the Turing paradigm of algorithmic computation is insufficient for modeling knowledge-centric systems. Instead, BMT proposes structural machines, in which computation is not merely symbol manipulation but the evolution and interaction of structures across multiple layers of organization.

Structural machines enable the operationalization of digital genomes, self-repairing architectures, and teleonomic systems that can adaptively sustain coherence under shifting conditions. This represents an engineering instantiation of the Physics of Knowledge: showing not just that knowledge-bearing constraints exist, but that they can be designed, measured, and tested.

3.4. Metastability and Teleonomy

A unifying concept across GTI, Fold Theory, and BMT is that of metastability. Knowledge-bearing systems remain poised between equilibrium and chaos, able to flexibly adapt without disintegration. Teleonomy — the apparent goal-directedness of living systems (Monod 1971) — can be reframed in this context as the causal efficacy of knowledge constraints.

This reframing has profound implications: teleonomy is not a mystical property of life, nor reducible to blind statistical regularities, but a manifestation of physics extended to include knowledge as an organizing principle. The Physics of Knowledge therefore provides a naturalistic account of mind and purpose without recourse to exotic microphysics (Penrose) or metaphysical rupture (Rickles)..

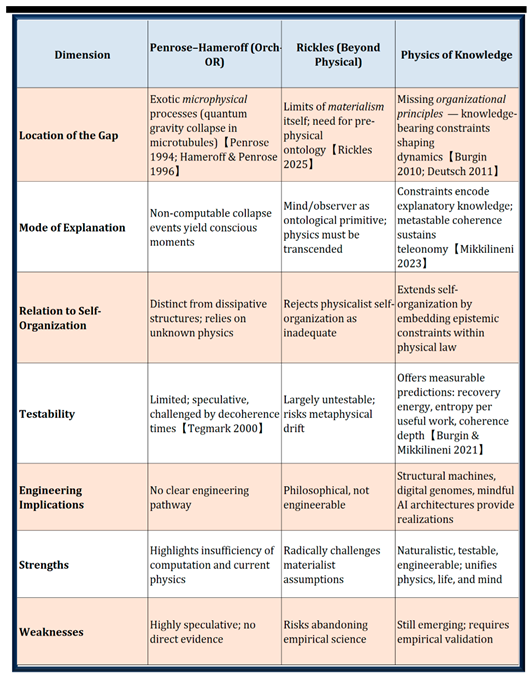

4. Comparative Framework

The debate over “missing physics” reveals three distinct loci of explanation: microphysics (Penrose–Hameroff), metaphysics (Rickles), and knowledge constraints (Physics of Knowledge). Each identifies a real gap, but their solutions diverge in explanatory scope, testability, and engineering implications.

Table 1 summarizes the three theories using eight dimensions.

5. From Theory to Testability

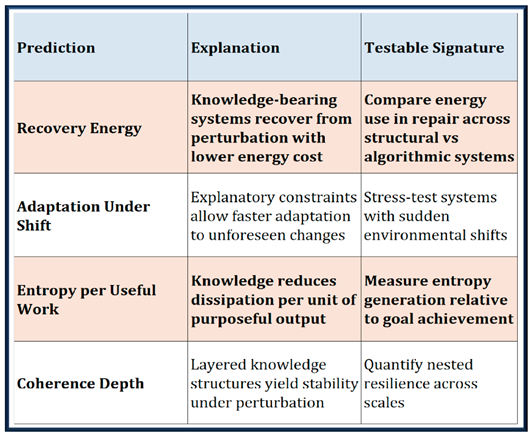

Traditional systems compute outputs; post-Turing systems compute understanding. The strength of the Physics of Knowledge framework lies not only in its conceptual coherence but also in its capacity to generate testable predictions. Unlike Penrose’s Orch-OR, which hinges on speculative microphysics, or Rickles’s call to transcend materialism, the Physics of Knowledge offers measurable pathways. By reframing knowledge as a causal constraint, embedded in GTI’s triadic structures and operationalized through Fold Theory and structural machines, the framework points to clear empirical signatures.

Recovery Energy: Knowledge-bearing systems will require less energy to recover from perturbations than systems without such constraints.

Adaptation Under Shift: Systems with explanatory knowledge constraints should adapt more rapidly and with fewer failures when exposed to unforeseen shifts.

Entropy per Useful Work: Knowledge-bearing systems should exhibit lower entropy production per unit of useful work achieved.

Coherence Depth: Systems with deeper coherence should display greater resilience and stability across scales. This offers a way to empirically distinguish systems with shallow, emergent organization from those governed by embedded knowledge constraints.

Table 1 shows three theories analyzed in eight dimensions.

6. Implications

The Physics of Knowledge carries implications across three domains: physics, engineering, and philosophy. For physics, it extends physics with constraint-based ontology. For engineering and AI, it provides a roadmap for mindful machines and structural machines that embody explanatory knowledge. For philosophy, it offers a naturalist alternative to dualism and eliminativism, grounding teleonomy in causal constraints.

This framework suggests a research program that bridges physics, AI, and philosophy, and opens pathways to testable science of knowledge.

7. Conclusions

The transition from the Turing paradigm to the Mindful Machine Architecture rep-resents more than a technological evolution—it is a redefinition of what it means to compute. By integrating semantic and episodic memory, non-Markovian reasoning, autopoi-etic feedback, and zero-knowledge verifiability, Mindful Machines turn computation into a living process of knowledge creation and justification. The resulting General Theory of Epistemic Computation (GTEC) provides a unifying framework for building systems that are not only intelligent but self-knowing, self-regulating, and self-proving. As information technologies enter this epistemic era, the guiding principle will no longer be efficiency of execution but integrity of understanding—ensuring that every computational act contributes to the coherence, resilience, and trust of the whole.

Table 2.

Predictions, explanations, and testable signatures.

Table 2.

Predictions, explanations, and testable signatures.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, R.M; methodology, R.M, M.M..; “All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

Please add: “This research received no external funding”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“Not applicable”

Informed Consent Statement

“Not applicable.”

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

One of the authors. R.M acknowledge Dr. Judith Lee, Director of the Center for Business Innovation for many discussions and support.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”.

References

- Foxman, D.; Bateson, G. Steps to an Ecology of Mind. West. Politi- Q. 1973, 26, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, D. (1980). Wholeness and the Implicate Order. Routledge.

- Burgin, M. (2010). Theory of Information: Fundamentality, Diversity and Unification. World Scientific.

- Mikkilineni, R. Infusing Autopoietic and Cognitive Behaviors into Digital Automata to Improve Their Sentience, Resilience, and Intelligence. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2022, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, D. (2011). The beginning of infinity: Explanations that transform the world. Viking.

- Hameroff, S.; Penrose, R. Consciousness in the universe. Phys. Life Rev. 2014, 11, 39–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haken, H. (1977). Synergetics: An Introduction. Springer.

- Maturana, H. & Varela, F. (1980). Autopoiesis and Cognition. Reidel. [CrossRef]

- Hill, S. L. (2025a, June). Fold Theory: A categorical framework for emergent spacetime and coherence (preprint). Academia.edu. https://www.academia. 1300. [Google Scholar]

- Monod, J. (1971). Chance and Necessity. Knopf.

- Penrose, R. (1989). The Emperor’s New Mind. Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. (1994). Shadows of the Mind. Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Prigogine, I. (1977). Self-Organization in Nonequilibrium Systems. Wiley.

- Rickles, D. (2025). To Solve Quantum Gravity We Must Go Beyond the Physical. IAI News.

- Tegmark, M. Importance of quantum decoherence in brain processes. Phys. Rev. E 2000, 61, 4194–4206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, J.A. (1990). Information, physics, quantum: The search for links. In Complexity, Entropy, and the Physics of Information (Zurek, ed.).

Table 1.

Three theories in eight dimensions.

Table 1.

Three theories in eight dimensions.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).