1. Introduction

Radiology occupies a central role in contemporary healthcare, serving as a fundamental tool in the diagnosis, treatment planning, and monitoring of a myriad of diseases [

1]. Despite its importance, the field is facing an imbalance between the demand for imaging diagnosis and the supply of radiologists. The number of diagnostic studies has exploded exponentially over the past decade while the radiologist workforce remains nearly stagnant, resulting in substantially increased workload per radiologist [

2]. Furthermore, technological advances in medical imaging have led to examinations that generate hundreds of images per study, compounding the interpretation burden beyond what simple case numbers suggest [

3]. Such heavy caseloads can translate into significant delays in report turnaround times with overburdened specialists struggling to keep pace with ever-expanding worklists [

4]. Moreover, interpretation variability is an inherent challenge as different radiologists may provide differing descriptions or even miss findings under stress, leading to inconsistencies in diagnostic reports [

5]. These workflow bottlenecks and potential discrepancies in reporting highlight a pressing need for automated tools that can generate preliminary image captions or draft reports, helping to reduce turnaround time and standardize diagnostic descriptions across practitioners [

6]. In this context, automated radiology image captioning has emerged as an important research direction, aiming to have Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems produce clinically relevant descriptions of medical images that can assist radiologists and mitigate delays in care [

7,

8].

Recent advances in AI offer promising avenues to address these challenges. In particular, VLMs have shown remarkable capabilities in translating images into text by combining visual processing with natural language generation [

9]. By integrating vision and language modalities, VLMs achieve a more holistic understanding of complex data and can perform sophisticated image captioning task. General-purpose VLMs like Large Language and Vision Assistants (LLaVA) [

10], DeepMind’s Flamingo [

11], and Contrastive Language–Image Pre-training (CLIP) [

12] have demonstrated high performance on broad image–text benchmarks. Building on these successes, specialized medical VLMs are now emerging. For example, BioViL [

13], Med-Flamingo [

14], and RadFM [

15] adapt multimodal pretraining to clinical data and have been shown to better capture the nuanced visual–textual patterns of medical imagery. Using knowledge from large-scale multimodal pre-training, VLMs can assist in detecting subtle abnormalities on imaging that might be difficult for the human eye to spot [

16]. The appeal of VLM-based captioning in radiology is thus twofold: it could expedite the reporting process by automatically generating draft descriptions of findings, and it could provide more consistent, standardized captions that reduce subjective variability [

17].

Importantly, VLMs today span a wide spectrum of model sizes and complexities [

18]. On one end are large-scale VLMs with many billions of parameters (for instance, while the original IDEFICS model contains 80B parameters and represents the upper extreme, more practical variants like IDEFICS-9B offer a balance of capability and deployability) [

19]. These larger models often achieve state-of-the-art (SOTA) accuracy and can produce very detailed, fluent image descriptions. However, their size comes with substantial drawbacks. They require enormous computing resources for training and inference, typically needing multiple high-memory GPUs or specialized hardware accelerators. Integrating such a model into a clinical pipeline can be computationally prohibitive, as these systems tend to be resource-intensive and difficult to deploy on standard workstations. On the other end are lightweight VLMs with on the order of a few hundred million to a few billion parameters [

20]. These compact models are designed for efficiency and easier deployment. They can often run on a single commodity GPU, making them attractive for smaller hospitals or research labs without access to extensive computing infrastructure. The trade-off, however, is that smaller models may exhibit lower raw performance. They may miss finer details or produce less fluent captions compared to their larger counterparts. This dichotomy between large and small VLMs raises an important challenge for the field, namely the need to balance model accuracy and descriptive detail with considerations of computational efficiency and resource availability [

21]. Resolving this trade-off will be critical for facilitating the practical integration of AI-based image captioning systems into clinical workflows.

A key limitation of the LVLMs is the difficulty of fine-tuning and deploying them in typical clinical research settings [

22]. Fully fine-tuning a multi-billion-parameter model for a specific task (such as radiology captioning) is computationally expensive and memory-intensive, often to the point of impracticality [

23]. For many clinical settings, it is not feasible to dedicate the necessary GPU clusters or prolonged training time required for traditional fine-tuning of a giant model on local data [

24]. Furthermore, even after training, inference with an LVLM can be slow and require significant GPU memory, impeding real-time use [

25]. These factors have motivated a shift toward methods that favor deployability on standard hardware over brute-force model training [

26]. In practice, it is often more desirable to take a strong pre-trained VLM and adapt it in a lightweight manner that can run on an everyday workstation, rather than to re-train or heavily fine-tune it requiring specialized hardware [

27].

In response, researchers have developed parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) techniques that significantly reduce the resources needed to adapt large models [

24]. PEFT approaches adjust only a small fraction of the model’s parameters while keeping most weights of the pre-trained model frozen. This drastically lowers the computational and memory overhead of training, making it possible to fine-tune large models on modest hardware [

28]. Among these methods, Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) [

29] has gained particular prominence for vision–language applications. LoRA inserts a pair of low-rank trainable weight matrices into each layer of the model, which are learned during fine-tuning instead of modifying the full weight matrices [

30]. This approach effectively injects task-specific knowledge into the model with only a few million additional parameters, all while preserving the original model’s weights. Our experiments demonstrate that PEFT with LoRA can surpass fully fine-tuned traditional architectures, validating the effectiveness of this approach. The growing use of PEFT means that even LVLMs containing tens of billions of parameters can be adapted to niche tasks like medical image captioning using standard GPU, without needing to retrain the entire network from scratch [

24]. This is a crucial step toward making advanced multimodal AI accessible in clinical settings.

Despite rapid progress in VLM development, there are gaps in understanding how model scale and tuning strategies impact performance in medical image captioning [

31]. First, there is a lack of unified, head-to-head comparisons of different sized models on the same clinical imaging dataset [

7]. Much of the prior work evaluates models in isolation or on differing data, which makes it difficult to objectively determine how a 500-million-parameter model stacks up against a 9-billion-parameter model under similar conditions [

32]. As a result, the field has had an unclear picture of the true trade-offs between clinical utility (caption quality) across the spectrum of model sizes. Second, existing image captioning studies in radiology have rarely assessed how well models generalize across multiple imaging modalities. Many works focus on a single modality (e.g., chest X-rays); far fewer have tested models on diverse modalities (e.g., X-rays, MRI, CT, etc.) to ensure the captioning approach is broadly applicable [

7]. Indeed, models trained on one modality often struggle to interpret others without additional training. This modality-specific focus leaves open the question of how a given model’s performance might change when confronted with different image types or anatomies, an important consideration for real-world deployment. Third, to our knowledge, the published literature lacks a systematic comparison of parameter-efficient adaptation strategies for VLMs that empirically identifies optimal configurations for radiology captioning performance [

32]. Additionally, inference-time augmentations, which are simple strategies applied at the time of caption generation to guide the model, have not been thoroughly investigated in this domain. For example, explicitly telling a model the modality of the image such as prepending the phrase “Radiograph:” or “CT:” to the input could, in theory, provide helpful context to a VLM [

33]. Intuitively, this modality-aware prompting might remind the low performing SVLMs of relevant domain knowledge and improve caption accuracy. Our investigation explores whether such interventions can compensate for reduced model capacity, potentially enabling smaller models to achieve competitive performance.

To address these gaps, we evaluate a spectrum of VLMs on a unified radiology image captioning task using LoRA. The evaluation spans models ranging from large, SOTA multimodal systems to smaller alternatives, all tested on the ROCOv2 dataset. On the larger end, we assess LVLMs such as LLaVA variants with Mistral-7B and Vicuna-7B backbones, LLaVA-1.5, as well as IDEFICS-9B. On the smaller end, we include MoonDream2, Qwen 2-VL, Qwen-2.5, and SmolVLM. By evaluating models spanning nearly a 19-fold range in parameter count, we quantify how model scale influences performance in radiology captioning. To provide additional context we also benchmark these parameter-efficient fine-tuned VLMs against two baseline image captioning architectures from prior research [

34]. The first is a fully fine-tuned CNN–Transformer model that uses a CNN network encoder similar to CheXNet paired with a Transformer-based decoder for language. This approach reflects traditional image captioning pipelines developed before the emergence of large multimodal models. The second is a fully fine-tuned custom VisionGPT2 model that employs a pre-trained GPT-2 language model conditioned on visual features–previously compared against a LoRA-adapted LLaVA-1.6-Mistral-7B in our preliminary investigation [

21]. Including these baselines allows us to directly assess the performance gains of recent VLMs relative to earlier techniques.

We also investigate the effectiveness of modality-aware prompting as an inference-time intervention for the underperforming SVLMs [

33]. In these experiments, the model is prepended with a text prompt indicating the image type (for instance, supplying “MRI:” or “ultrasound:” before the image is processed) to provide additional context. Our results show that this leads to only minor improvements in the fluency of captions generated by a few SVLMs, and does not meaningfully close the performance gap relative to the larger models. In other words, while adding modality cues can make a caption slightly more coherent or tailored for some models, it is not a substitute for the richer internal knowledge that LVLMs bring. The larger models consistently produce more detailed and clinically accurate captions, highlighting that model scale (and the breadth of training data it entails) remains a dominant factor in captioning quality.

Overall, this study provides a comparative benchmark of VLMs fine-tuned with LoRA for radiology captioning. By systematically evaluating models across scales from LVLMs to SVLMs, and reporting both parameter counts and adaptation targets, we clarify how model size and tuning strategies affect performance. In doing so, our work addresses gaps in prior studies by offering a comparison across model scales and establishing a reference point for future research. The following sections outline our methodology, present experimental results, and discuss their implications for advancing medical image captioning.

3. Experimental Results

3.1. Optimal Adaptation Strategy Selection

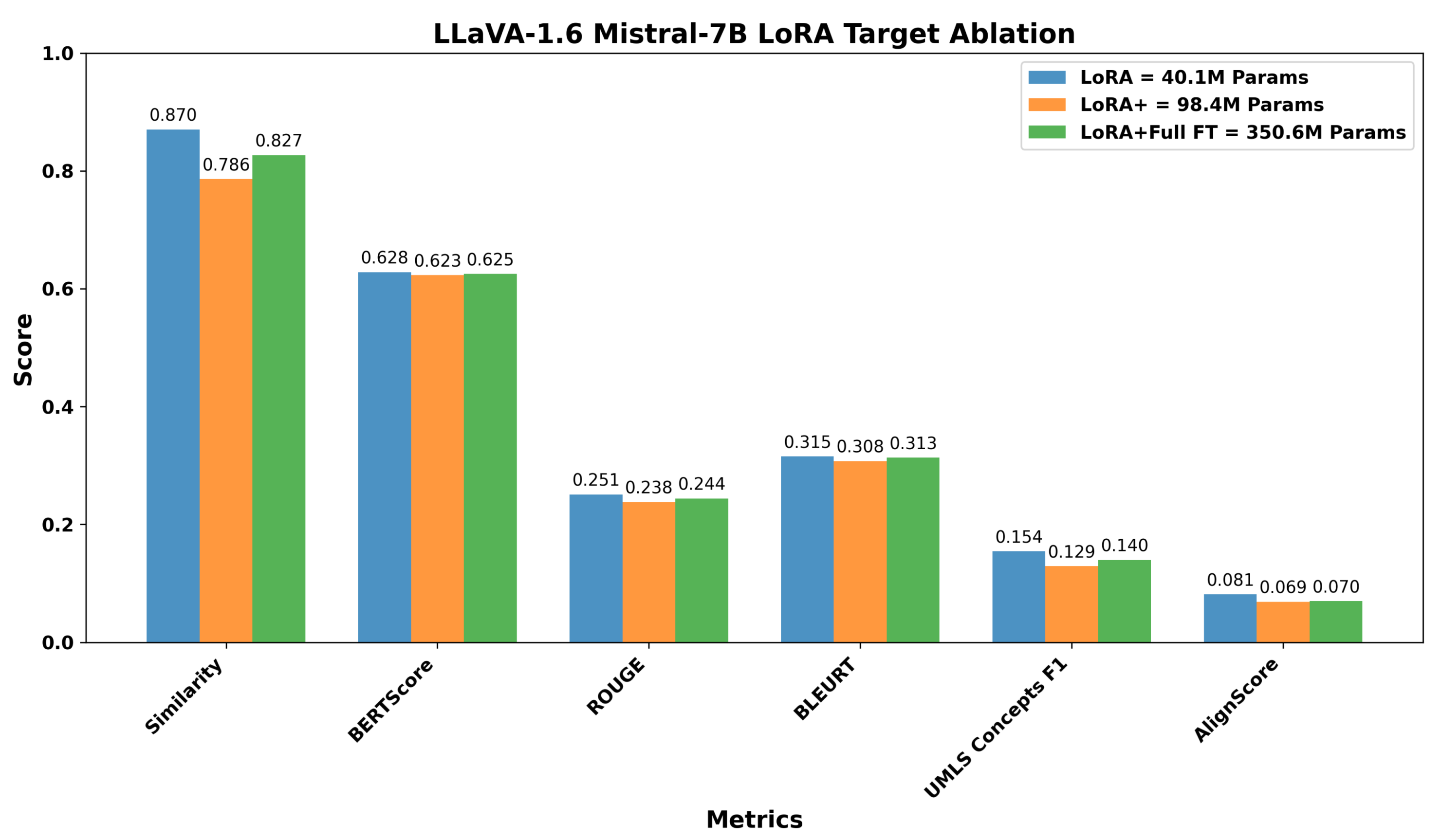

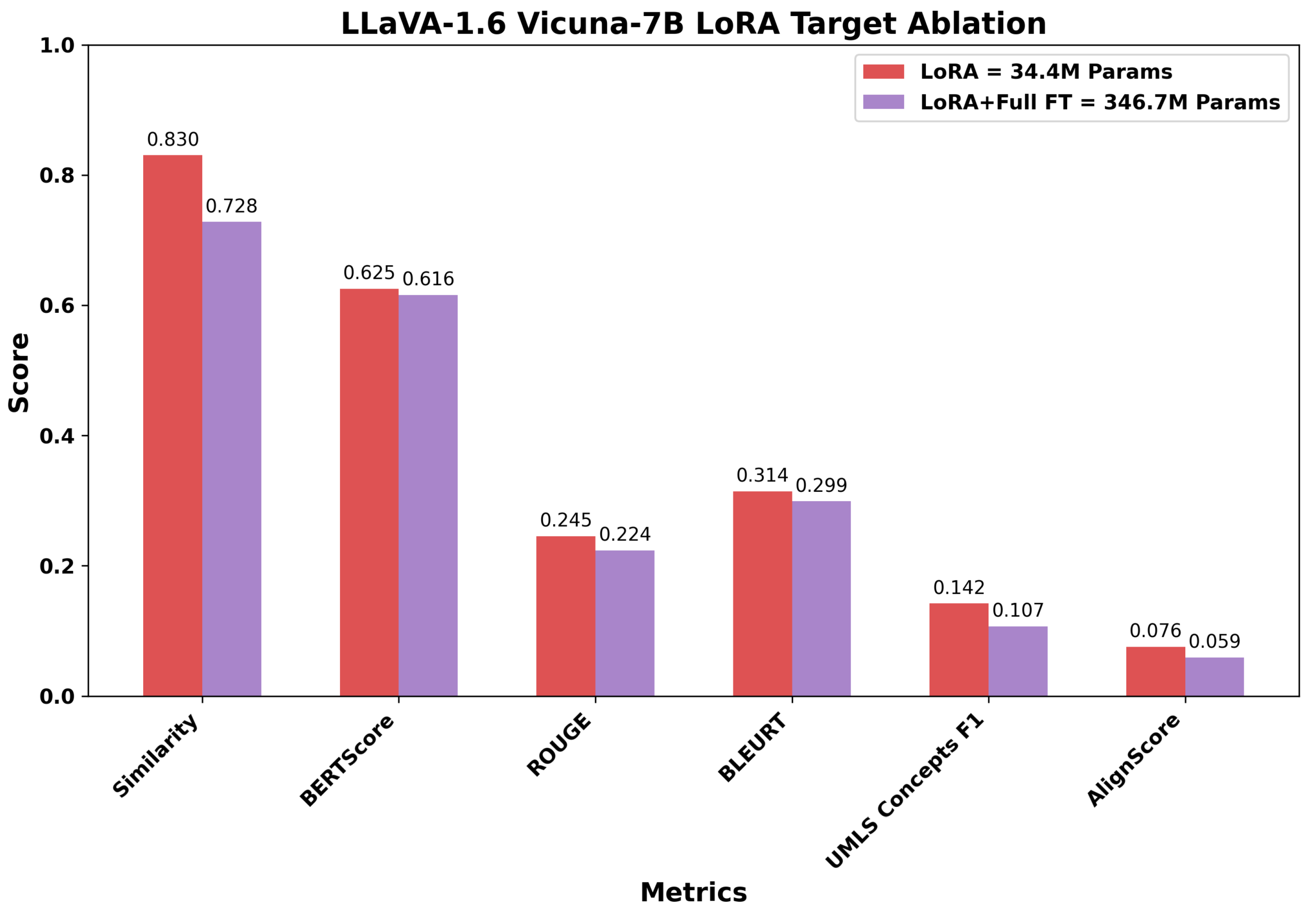

Before conducting cross-model comparisons, we evaluated LoRA strategies to identify optimal configurations for parameter-efficient fine-tuning. Using the LLaVA architecture with two different language model backbones (Mistral-7B and Vicuna-7B) as representative examples, we compared adaptation approaches varying in complexity and parameter count. For LLaVA Mistral-7B, we evaluated: (1) LoRA selectively applied to attention mechanisms and MLP blocks (40.1M parameters, 0.53% of model), (2) extended LoRA including output projections and multimodal connector layers (98.4M parameters, 1.28%), and (3) a hybrid approach combining LoRA with full fine-tuning of language head and embeddings (350.6M parameters, 4.58%). For LLaVA Vicuna-7B, we compared targeted LoRA (34.4M parameters, 0.48%), inclduing multimodal projections, against the hybrid approach (346.7M parameters, 4.85%). The layer targets for each configuration are provided in the methodology.

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 show the results across six evaluation metrics. For LLaVA Mistral-7B, the targeted LoRA achieved the highest Image Caption Similarity score of 0.870, compared to 0.786 for extended LoRA and 0.827 for the hybrid approach, corresponding to relative drops of 9.7% and 5.0%, respectively. A similar trend was observed across relevance-oriented metrics, with BERTScore showing minimal variation (0.628, 0.623, 0.625) but ROUGE and BLEURT exhibiting clearer advantages for targeted adaptation. ROUGE scores decreased from 0.251 (targeted) to 0.238 (extended) and 0.244 (hybrid), while BLEURT scores followed a similar declining pattern from 0.315 to 0.308 to 0.313.

The performance differences were more pronounced in factuality metrics. UMLS Concepts F1, which measures the preservation of medical terminology, decreased from 0.154 (targeted) to 0.129 (extended) and 0.140 (hybrid), representing 16.2% and 9.1% reductions. Similarly, AlignScore dropped from 0.081 to 0.069 (14.8% reduction) and 0.070 (13.6% reduction), respectively. These metrics are clinically salient because they reflect preservation of medical terminology and factual consistency.

The LLaVA Vicuna-7B results reinforced this pattern. The LoRA configuration (34.4M parameters) outperformed the hybrid approach (346.7M parameters) despite using one-tenth of the trainable parameters. Image Caption Similarity decreased from 0.830 to 0.728 (12.3% reduction), while UMLS Concepts F1 dropped from 0.142 to 0.107 (24.6% reduction) and AlignScore fell from 0.076 to 0.059 (22.4% reduction). The substantial degradation in factuality metrics with expanded adaptation complexity further suggests that modifying larger parameter sets can disrupt the model’s learned medical knowledge representations rather than enhancing them.

Overall, increasing the number of trainable parameters does not necessarily improve performance across relevance and factuality dimensions. The targeted LoRA approach, which modifies only a small and selective subset of the pre-trained model’s parameters, achieved comparable or superior task-specific adaptation. This suggests that modest and targeted intervention in the model’s parameter space is sufficient to retain general pre-trained representations while enabling effective incorporation of domain-specific knowledge. Consequently, all subsequent cross-model comparisons report results for the targeted adaptation variant of each VLM, favoring configurations that balance performance with computational efficiency.

3.2. Cross-Model Performance Comparison

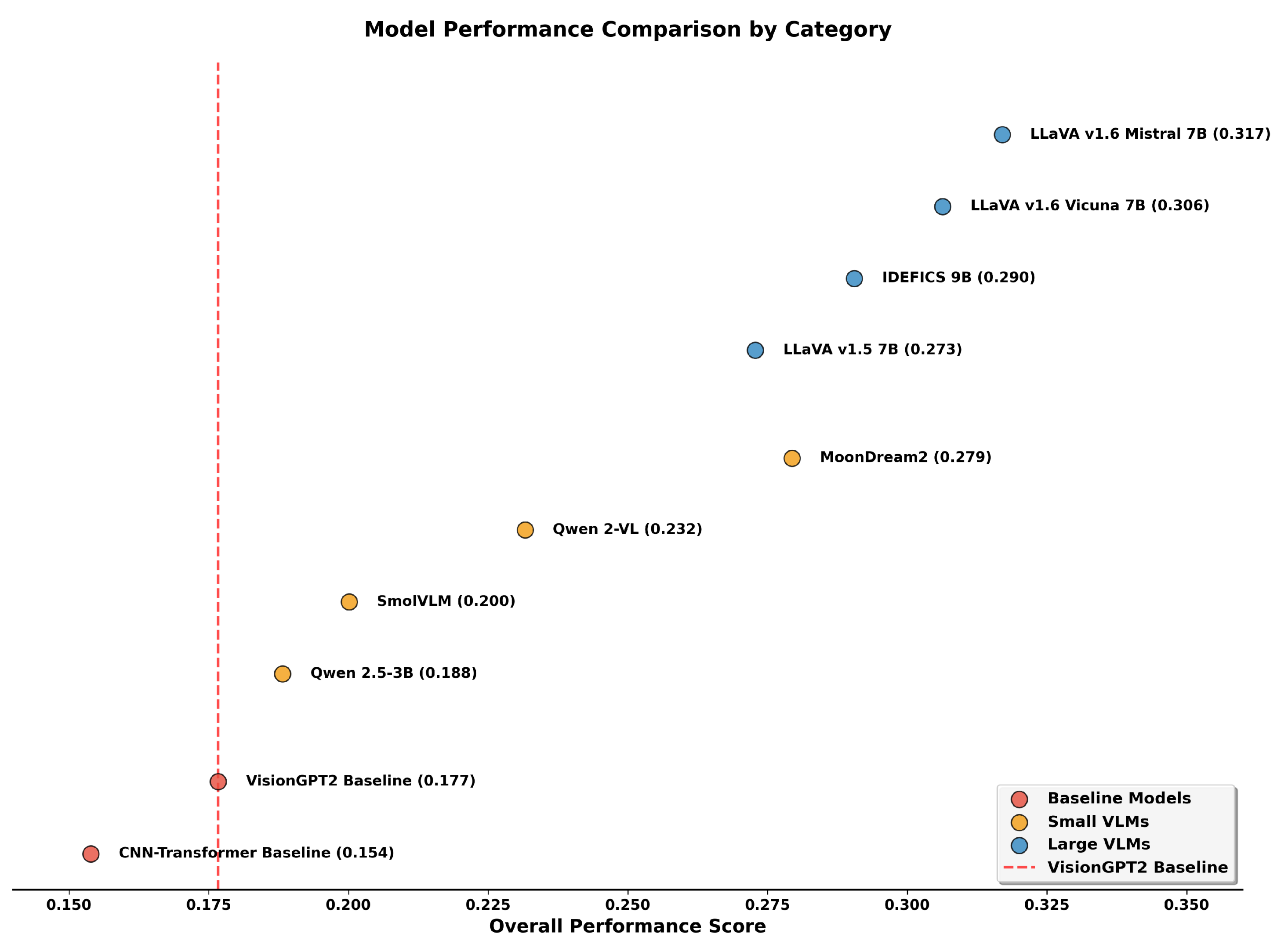

Having established that targeted LoRA provides optimal performance-efficiency trade-offs, we evaluated eight vision-language models and two baseline architectures on the radiology image captioning task. All models employed their best configurations as determined by preliminary experiments.

Table 4 presents comprehensive performance metrics across all evaluated systems.

The results reveal a clear performance hierarchy across model categories. Among LVLMs, LLaVA Mistral-7B achieved the highest overall average (0.317), with particularly strong performance in Image Caption Similarity (0.870) and relevance metrics (0.516 average). This corresponds to a 79.1% gain in Overall Average relative to the strongest baseline (VisionGPT2), despite using only 0.53% trainable parameters compared to the baseline’s full fine-tuning approach. LLaVA Vicuna-7B followed closely with an overall average of 0.306, showing comparable performance with even fewer trainable parameters (0.48%). IDEFICS-9B, achieved intermediate performance (0.290 overall), while LLaVA-1.5 showed lower scores (0.273), likely reflecting its older architecture and training setup.

Among SVLMs, MoonDream2 emerged as the strongest performer with an overall average of 0.279, attaining performance comparable to LLaVA-1.5 (0.273) while using approximately 74% fewer total parameters. Notably, MoonDream2’s relevance average (0.466) approached that of some LVLMs, with its Image Caption Similarity (0.757) and BLEURT scores (0.303) demonstrating competitive semantic alignment. Moreover, MoonDream2’s factuality metrics (0.093) also outperformed LLaVA-1.5 (0.083), suggesting that architectural innovations and training strategies can partially compensate for reduced model size. However, the top-performing LLaVA Mistral-7B maintains clear advantages with factuality scores of 0.118, indicating that while efficient architectures narrow the gap, fundamental capacity differences remain for the most demanding clinical applications. Qwen 2-VL, SmolVLM, and Qwen-2.5 showed progressively lower performance with 0.232, 0.200, and 0.188 average overall scores respectively. Interestingly, Qwen-2.5 achieved the lowest overall average (0.188) among SVLMs, even underperforming SmolVLM (0.200) which has fewer total parameters (0.5B vs 3.1B). This counterintuitive result suggests that model architecture and pre-training quality may be more determinative than raw parameter count for smaller models. Qwen 2-VL presents another anomaly, achieving the highest AlignScore (0.109) among all models including LVLMs, while having relatively weaker overall performance (0.232). This unusually strong factual claim consistency despite weak relevance metrics (0.372) suggests that Qwen 2-VL may have been pre-trained on data distributions that emphasize factual alignment over semantic similarity, though this comes at the cost of overall caption quality.

The baseline models performed substantially below all LoRA-adapted VLMs. VisionGPT2, the stronger baseline with an overall average of 0.177, was outperformed by even the lowest performing SVLM (Qwen-2.5 at 0.188). The CNN-Transformer baseline showed the weakest performance (0.154 overall), with particularly poor ROUGE scores (0.044) indicating limited n-gram overlap with reference captions. These results demonstrate that parameter-efficient adaptation of pre-trained VLMs consistently outperforms traditional fine-tuned baselines, even when the LVLMs and SVLMs use less than 1% and 9% of the total trainable parameters, respectively.

Figure 8 illustrates the performance distribution across model categories by overall average. There is a distinctive separation between LVLMs (0.273–0.317 range), SVLMs (0.188–0.279 range), and baselines (0.154–0.177 range). Notably, MoonDream2 bridges the gap between small and large models, achieving performance comparable to LLaVA-1.5 despite its significantly smaller size.

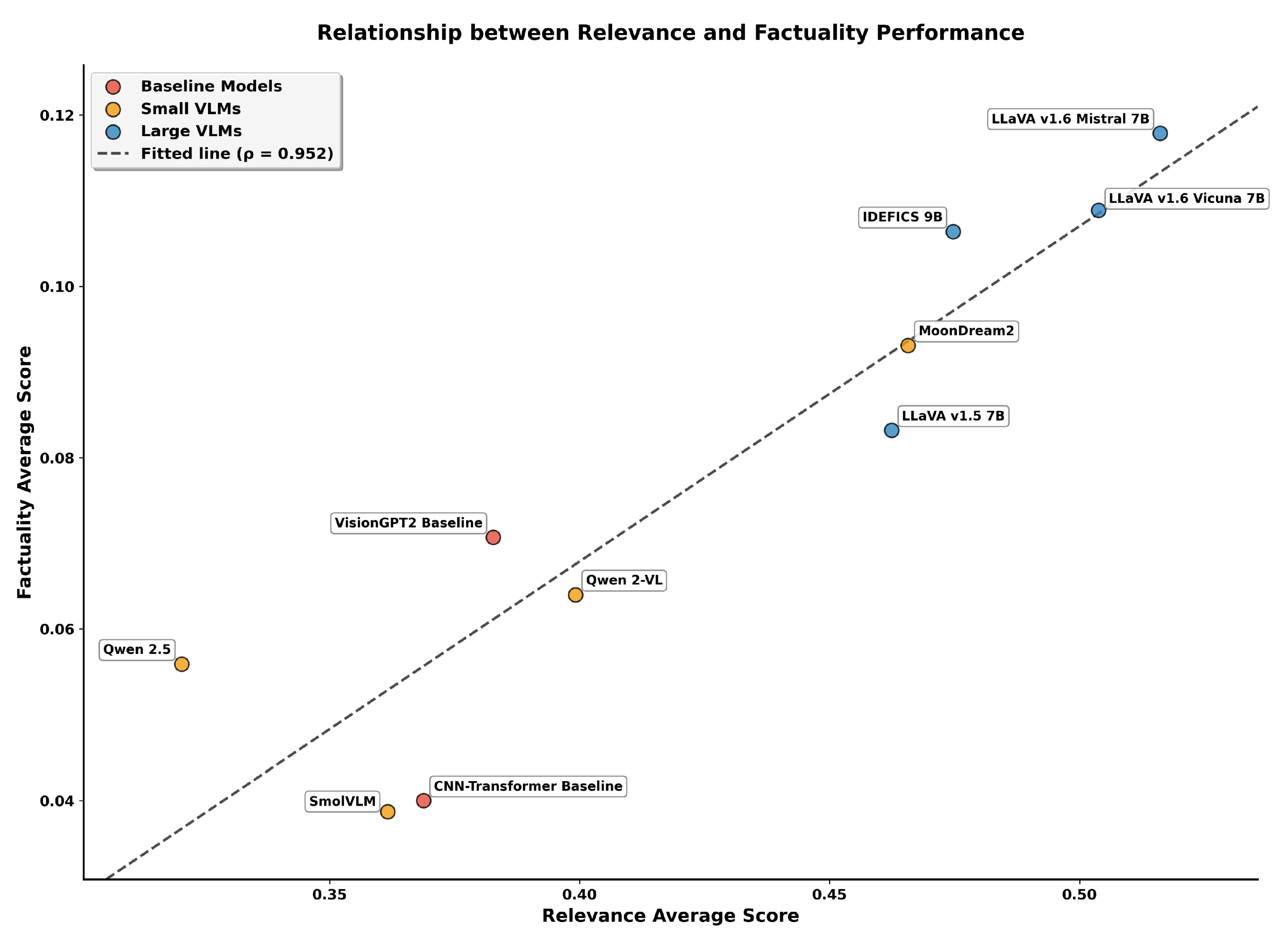

To further examine how linguistic relevance relates to clinical factuality, we analyzed the relationship between the two aggregated metrics across all evaluated models.

Figure 9 presents a scatter plot of Relevance Average against Factuality Average with an overlaid regression line. We computed Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (

) [

74] to measure the strength of the monotonic association between the two metrics. This non-parametric measure was selected given our sample size (n = 10) as it makes no distributional assumptions and is more robust to outliers than parametric alternatives [

75]. The coefficient was obtained by ranking models separately on their relevance and factuality scores, then calculating the correlation between these ranks using the

scipy.stats.spearmanr function. The high correlation value indicates that models achieving stronger semantic alignment consistently demonstrate better preservation of medical concepts, with the rank ordering being nearly perfectly preserved across both dimensions. The fitted regression line shown in the figure provides additional visual insight into the linear trend. The regression analysis, performed using ordinary least squares, demonstrates that the relationship between relevance and factuality is not only monotonic but also approximately linear across the range of observed values. This strong association validates the multi-metric evaluation approach, suggesting that improvements in linguistic similarity could be associated with accurate preservation of clinical information.

The scatter plot reveals distinct clustering patterns. LVLMs occupy the upper-right quadrant (relevance 0.462–0.516, factuality 0.083–0.118), while baselines cluster in the lower-left region (relevance 0.284–0.325, factuality 0.024–0.028). SVLMs show greater variability between these extremes. MoonDream2 represents a particularly interesting case, achieving relevance comparable to IDEFICS-9B (0.466 vs. 0.482) while maintaining factuality (0.093) that exceeds LLaVA-1.5 (0.083). This performance profile, where a 1.86B parameter MoonDream2 matches or exceeds certain 7B+ models on both dimensions, demonstrates that model efficiency can be achieved without proportional sacrifices in caption quality. These findings establish distinct performance tiers for clinical deployment consideration. The top performing LVLMs (LLaVA Mistral-7B and Vicuna-7B) are suitable for diagnostic applications requiring high accuracy. MoonDream2 occupies a unique position, offering performance that rivals some LVLMs while maintaining computational efficiency suitable for resource-constrained screening applications. The remaining SVLMs show mixed capabilities, with Qwen 2-VL’s strong factual alignment but weak relevance suggesting specialized use cases where claim consistency is prioritized over semantic fluency. Baseline models, with overall averages below 0.18, demonstrate the clear advantages of modern VLM architectures over traditional approaches.

3.3. Modality-Aware Prompting for Performance Enhancement in SVLMs

Given the performance gap between SVLMs and LVLMs, we investigated whether providing explicit modality information at inference time could enhance SVLM performance. In clinical practice, radiologists always know the imaging modality before interpretation, suggesting this contextual information could help models generate more appropriate captions. To test this hypothesis, we trained a ResNet-50 classifier on our dataset to predict image modality (CT, MRI, Radiograph, Ultrasound, Other), and then prepended these predicted labels to the input during inference for three low-performing SVLMs: SmolVLM, Qwen 2-VL, and Qwen-2.5-Instruct.

Table 5 shows that modality-aware prompting produced mixed results. SmolVLM improved slightly, with the overall score rising from 0.200 to 0.207, which is an increase of 3.5%. The largest changes were in factuality metrics: UMLS F1 rose from 0.016 to 0.031, an increase of 93.8%, and AlignScore increased from 0.060 to 0.096, a gain of 60.0%. Although these percentages are large, the absolute scores remain very low, which limits their clinical significance. Qwen-2.5 also showed modest improvement, with the overall score increasing from 0.188 to 0.200, equivalent to a 6.4% gain. This improvement was primarily in relevance, where the average increased from 0.320 to 0.351 (9.7%), supported by gains in Image Caption Similarity from 0.449 to 0.502 (11.8%). However, factuality declined from 0.056 to 0.049, a reduction of 12.5%.

In contrast, Qwen 2-VL experienced relative declination in performance. Its overall score decreased from 0.232 to 0.182, a reduction of 21.6%. Both relevance and factuality dropped sharply: Image Caption Similarity fell from 0.570 to 0.364, representing a 36.1% decrease, while UMLS F1 fell from 0.074 to 0.017, a reduction of 77.0%. This suggests that the addition of modality labels might have conflicted with the model’s pre-trained representations or that it already encoded modality implicitly, making the explicit label distracting.

Taken together, these results show that modality-aware prompting cannot bridge the gap between SVLMs and LVLMs. At best, SmolVLM and Qwen-2.5 gained modest improvements, but their absolute scores remain well below those of even the weakest LVLM. The performance decline of Qwen 2-VL further illustrates the risks of inference-time interventions without model-specific validation. Overall, providing image modality during caption prediction at inference time may offer small benefits in certain cases. However, it cannot substitute for the architectural advantages of LVLMs and does not represent a reliable strategy for enhancing SVLMs in clinical applications.

4. Discussion

VLMs offer potential as automated interpretation tools to accelerate report generation through clinically meaningful image captions. In this study, we compared LVLMs and SVLMs fine-tuned on the ROCOv2 dataset to assess their clinical utility. The comprehensive evaluation of VLMs for radiology image captioning reveals findings that merit closer examination on model scaling and adaptation strategies. Performance varied by model scale, with larger architectures generally outperforming smaller ones. However, lightweight adaptation using LoRA proved effective across the models.

Additionally, our investigation of inference-time interventions revealed that modality-aware prompting cannot compensate for fundamental architectural limitations in small models. While marginal improvements were observed for SmolVLM and Qwen-2.5, the absolute performance gains remained clinically insignificant. Moreover, simple radiologic findings were accurately captured by most models, while complex cases requiring multiple abnormality detection revealed clear performance stratification. These observations inform deployment strategies, with different model categories suitable for distinct clinical tasks ranging from initial abnormality detection to comprehensive diagnostic reporting. Overall, the study findings guide the selection of VLMs for resource-constrained medical imaging applications.

4.1. The Parameter Efficiency Paradox

Contrary to intuitive expectations, targeted LoRA using 0.48-0.53% of model parameters outperformed hybrid approaches that modified up to 4.85% of parameters. The results become clearer when examining the specific components targeted by each approach. Targeted adaptation focused on attention mechanisms and MLP layers while preserving output projections and embedding layers intact. Hybrid approaches additionally performed full fine-tuning on language heads and embeddings, which appears to disrupt pre-trained knowledge representations.

The preservation of medical terminology, evidenced by higher UMLS Concept F1 scores in selective adaptation for LLaVA Mistral-7B and LLaVA Vicuna-7B, suggests that targeted parameter modification maintains semantic understanding essential for clinical applications. Recent work in medical NLP has similarly demonstrated that extensive parameter modification increases catastrophic forgetting, particularly when target domains diverge substantially from pre-training distributions [

76]. In medical imaging, where both visual patterns and terminology differ markedly from natural images, preserving foundational knowledge while introducing focused adaptations appears superior to aggressive fine-tuning strategies.

4.2. Performance Patterns Across Caption Complexity

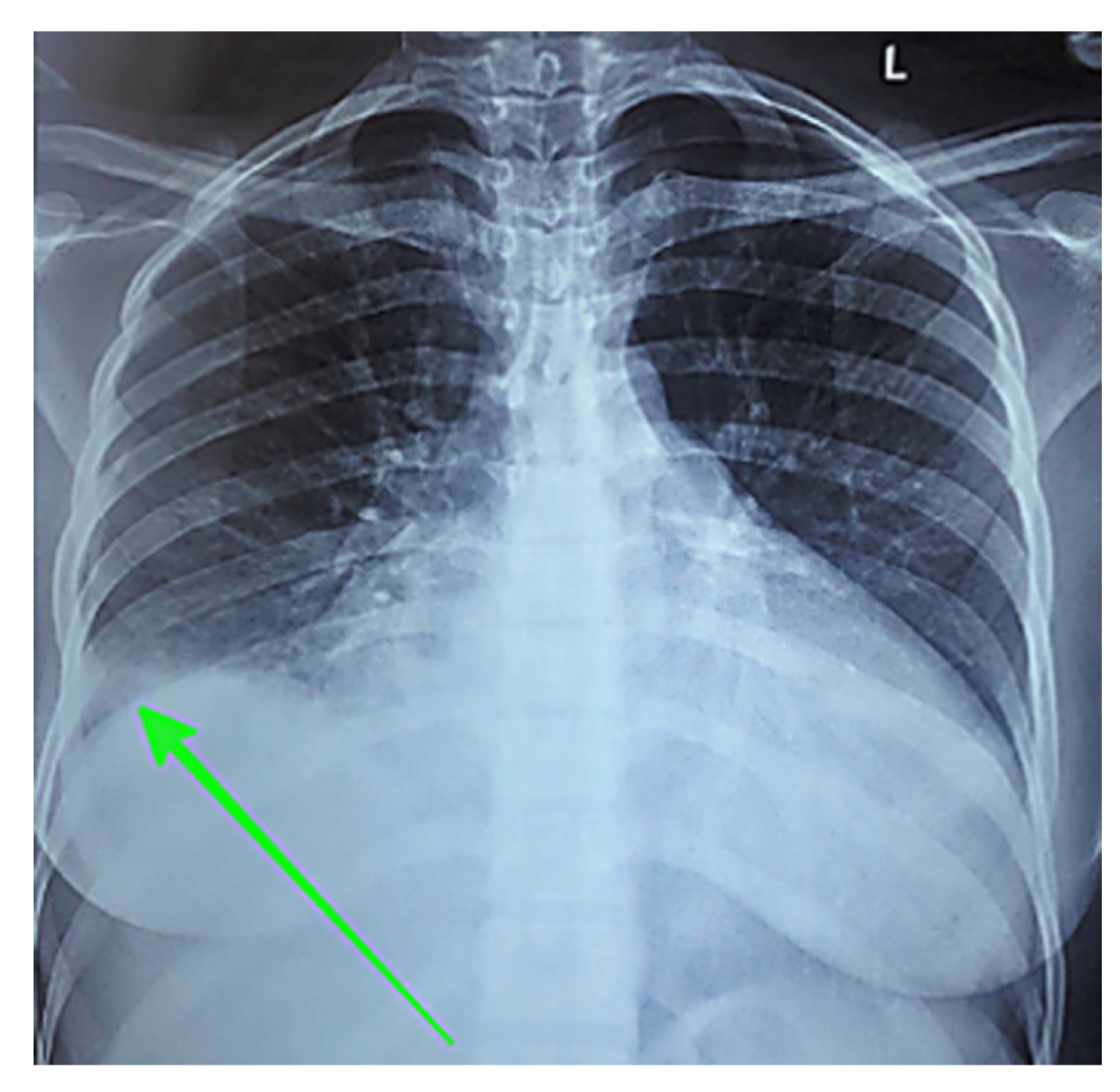

Two representative test cases from the dataset’s most prevalent modalities (i.e.,

CT scan and

X-ray scan) demonstrate how model capabilities translate to real-world performance. The chest X-ray case (

Figure 10) illustrates an example of the nature of model performance.

Table 6 presents detailed component analysis for this example. LVLMs generally identified core components such as image modality, anatomical location, and pathological findings with high fidelity for simple cases [

16]. However, multiple LVLMs also introduced the descriptor

large, which was absent from the ground truth. Additionally, most models correctly identified laterality (right-sided) and reproduced visual markers (parenthetical arrow descriptions), though these elements aid clinical interpretation but are not represented as UMLS concepts. This pattern appeared in other test cases as well, indicating a tendency of these models to amplify the perceived prominence of findings. Among SVLMs, performance varied considerably. MoonDream2 retained most components accurately despite the simplified visual marker. In contrast, Qwen 2.5 failed entirely by misidentifying both modality (

CT instead of

X-ray) and anatomy (

kidney instead of

chest), despite having a greater parameter count than Qwen 2-VL and SmolVLM.

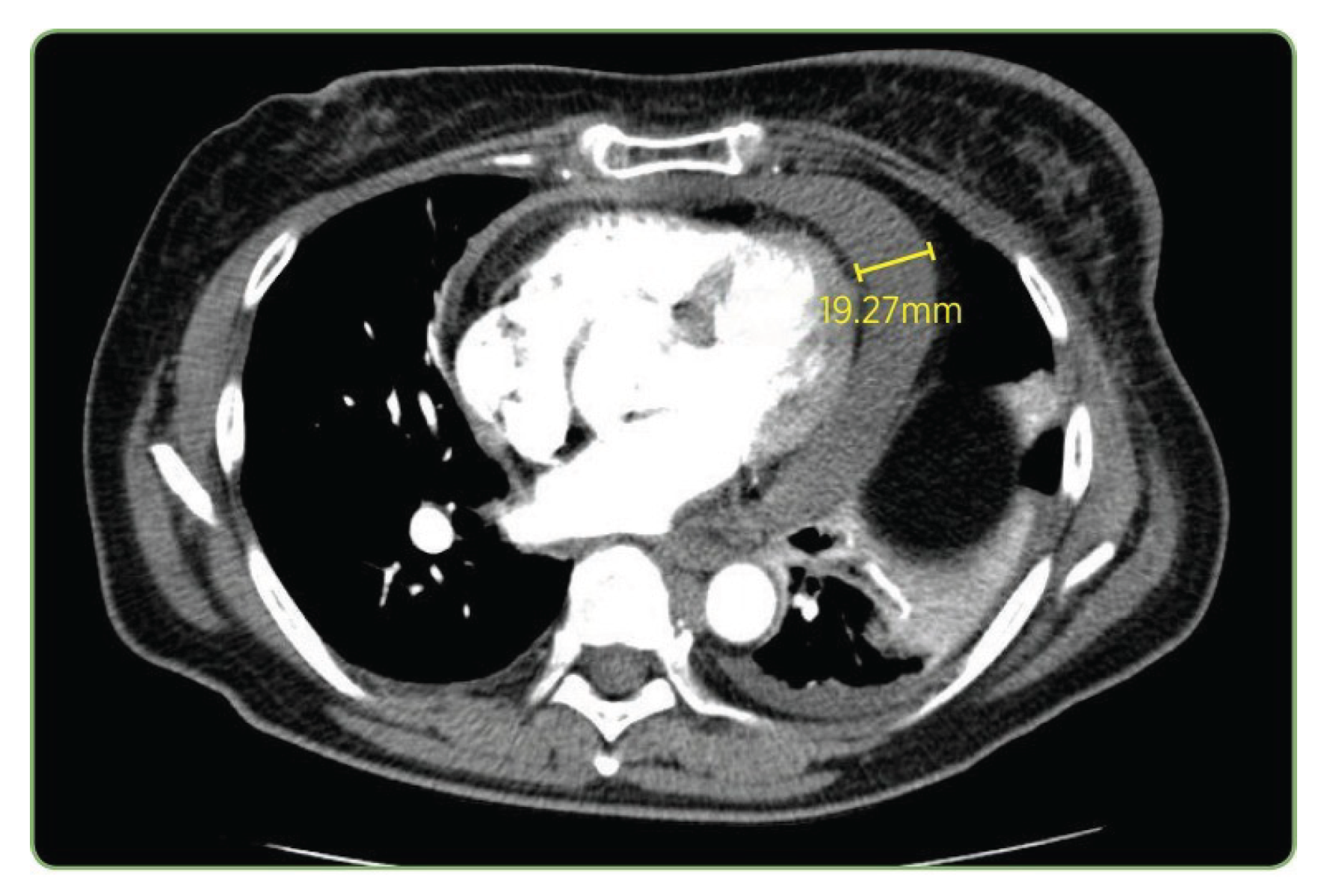

The CT case in

Figure 11 and

Table 7 exposed more pronounced performance stratification. Only LLaVA-Mistral-7B reproduced all components including the exact measurement

(19.27 mm). LLaVA-Vicuna-7B also captured the pathological finding and measurement correctly, although it substituted

pulmonary angiogram for

pulmonary embolus study, which is a variation in clinical terminology. LLaVA-1.5 and IDEFICS-9B correctly identified both the modality and the pulmonary context, matching the study type, though neither detected the actual pathological finding of

pericardial effusion. LLaVA-1.5 incorrectly described a

pulmonary embolism in the right lower lobe as the primary finding, while IDEFICS-9B produced a truncated and incomplete description.

Among SVLMs, MoonDream2 correctly identified the modality and general anatomical region (chest) but misinterpreted the finding as a large mass in the right upper lobe. Qwen 2-VL correctly identified the modality but described a vague right-sided mass without proper anatomical context. Both failed to identify the pericardial effusion. Qwen 2.5 failed completely by mislabeling the study as an axial T2 MRI. SmolVLM demonstrated partial success by correctly identifying the modality, chest anatomy, and extracting the precise measurement 19.27 mm, though it completely misattributed the measurement’s clinical context, suggesting surface-level pattern matching without semantic understanding. Thus, the performance degradation in Qwen 2-VL when modality prompting was applied underscores the need for careful validation before implementing augmentation strategies in clinical workflows. Analysis of caption generation across varying complexity levels exposed consistent patterns in model behavior.

The baseline models showed mixed performance. VisionGPT2 partially identified the modality (CT component of PET/CT) but misidentified the anatomy as hepatic. CNN-Transformer correctly identified the modality but described an incorrect finding (liver lesion). These fundamental errors in pathological finding identification underscore the limitations of traditional architectures even with full fine-tuning.

Overall, the LVLMs outperform SVLMs, which in turn exceed the fully fine-tuned baseline models. This performance stratification was evident in both component-level accuracy and overall caption coherence, as demonstrated in the two representative cases. The pattern holds across both simple and complex cases, with LVLMs achieving Overall Average scores of 0.273-0.317, SVLMs scoring 0.188-0.279, and baselines at 0.154-0.177. However, within each model family, performance comparisons become more nuanced. Among LVLMs, LLaVA-Mistral-7B outperformed IDEFICS-9B despite being smaller, while in the SVLM category, MoonDream2 exceeded Qwen 2.5 by a substantial margin. These intra-family variations indicate that when comparing models of similar scale, architectural design choices and pre-training quality become more determinative of performance than parameter count alone.

4.3. MoonDream2: Bridging the Efficiency Gap

In addition, MoonDream2’s performance profile demonstrates that efficient architectures can bridge the gap between model size and capability. It achieved relevance scores (0.466) comparable to IDEFICS-9B (0.482) and exceeded LLaVA-1.5 (0.462), despite being approximately 74% smaller than LLaVA-1.5. This efficiency likely stems from architectural optimizations in its SigLIP vision encoder and Phi-1.5 language backbone. Although MoonDream2 failed on complex multi-component captions, its reasonable performance on simpler cases positions it as a viable option for screening applications prioritizing basic abnormality detection over detailed characterization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H., M.M.R., and F.K.; methodology, M.H. and M.M.R.; software, M.H., R.N.C., and M.R.H.; validation, M.H., R.N.C., M.R.H., and O.O.E.P.; formal analysis, M.H.; investigation, M.H. and R.N.C.; resources, M.M.R.; data curation, R.N.C., M.R.H., M.H., and O.O.E.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.H.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, M.R.H., M.H., and O.O.E.P.; supervision, M.M.R. and F.K.; project administration, M.M.R.; funding acquisition, M.M.R. and F.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

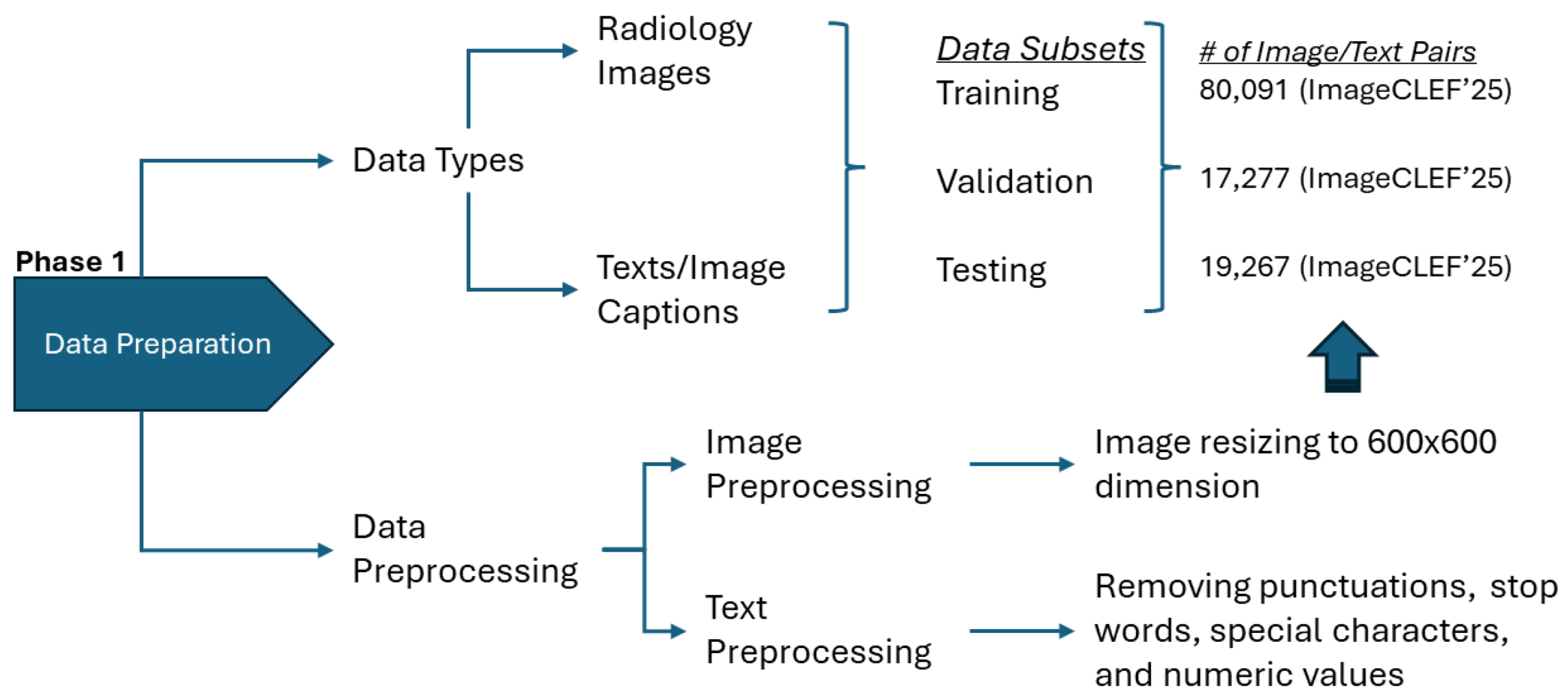

Figure 1.

Data preparation pipeline showing image standardization and text normalization procedures.

Figure 1.

Data preparation pipeline showing image standardization and text normalization procedures.

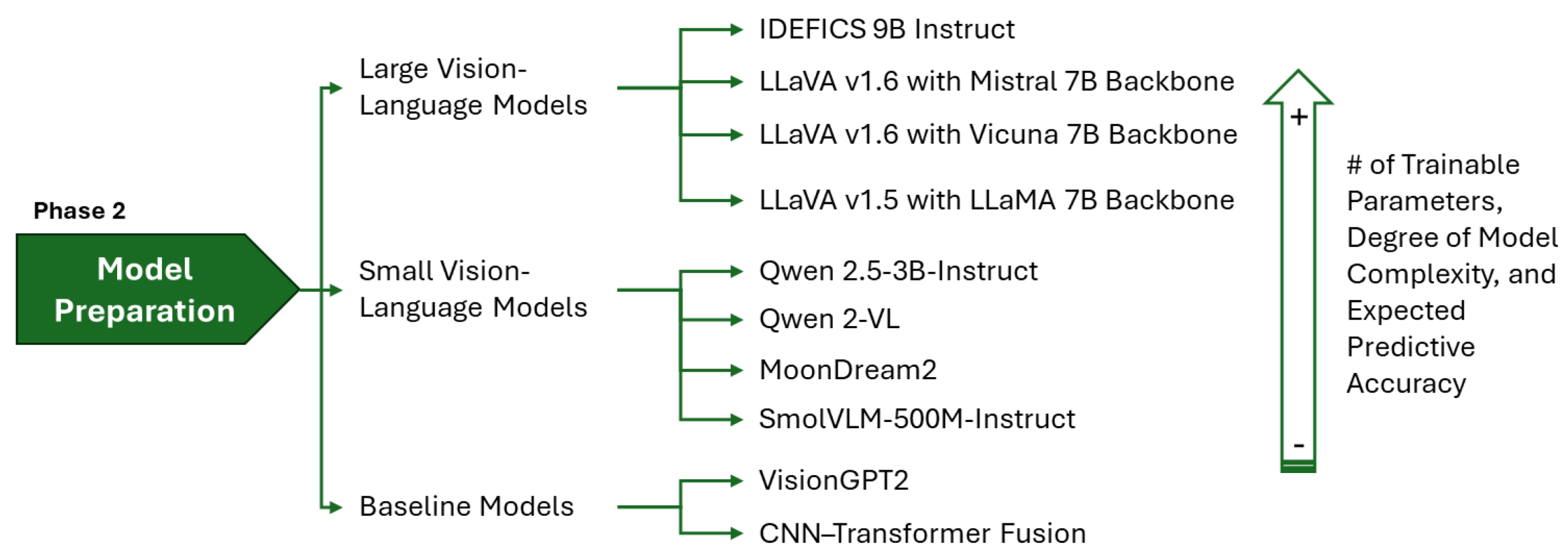

Figure 2.

Model preparation taxonomy: categorization of LVLMs, SVLMs, and baseline architectures evaluated.

Figure 2.

Model preparation taxonomy: categorization of LVLMs, SVLMs, and baseline architectures evaluated.

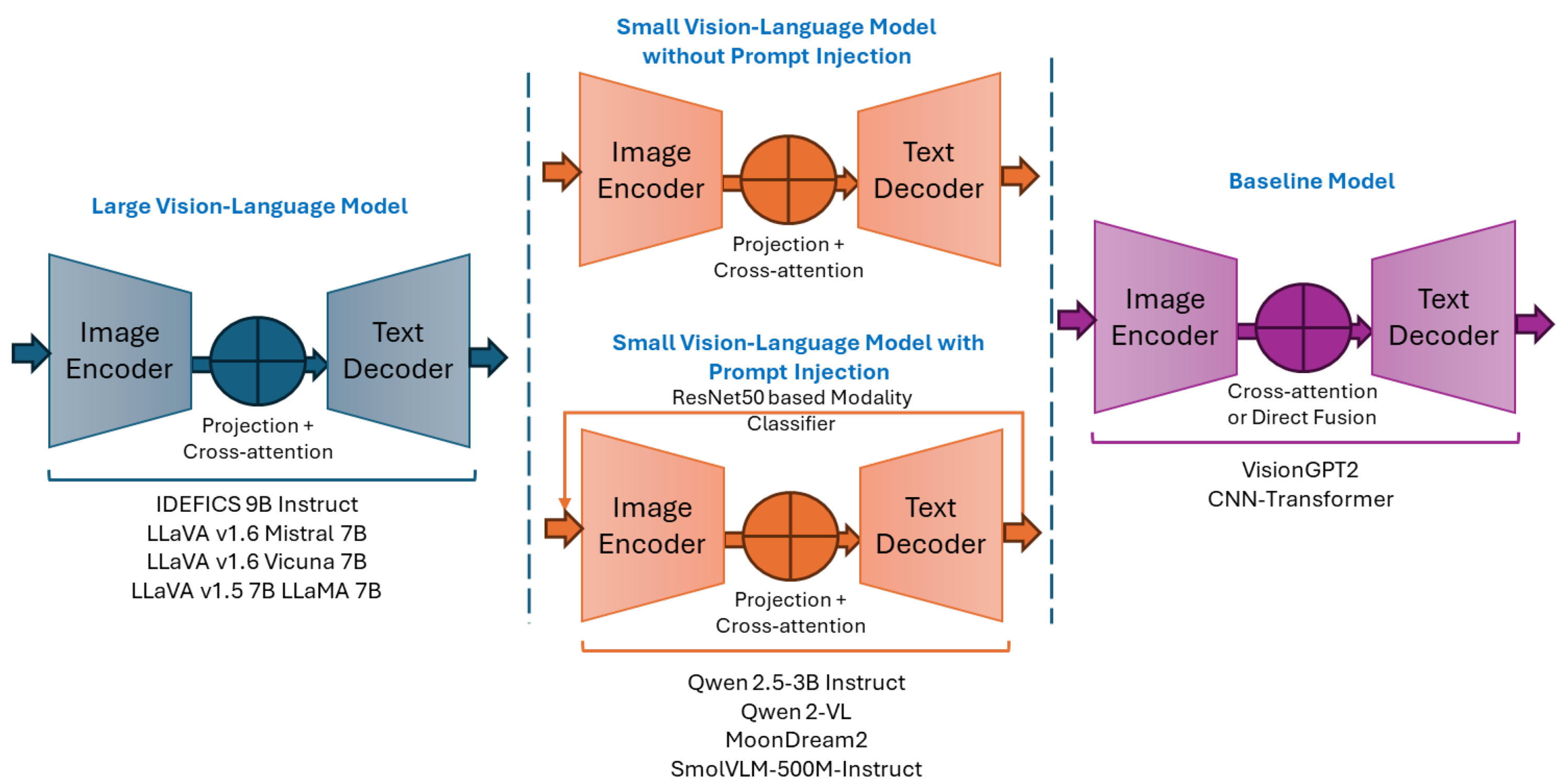

Figure 3.

Conceptual frameworks of the corresponding LVLMs, SVLMs, and baseline architectures.

Figure 3.

Conceptual frameworks of the corresponding LVLMs, SVLMs, and baseline architectures.

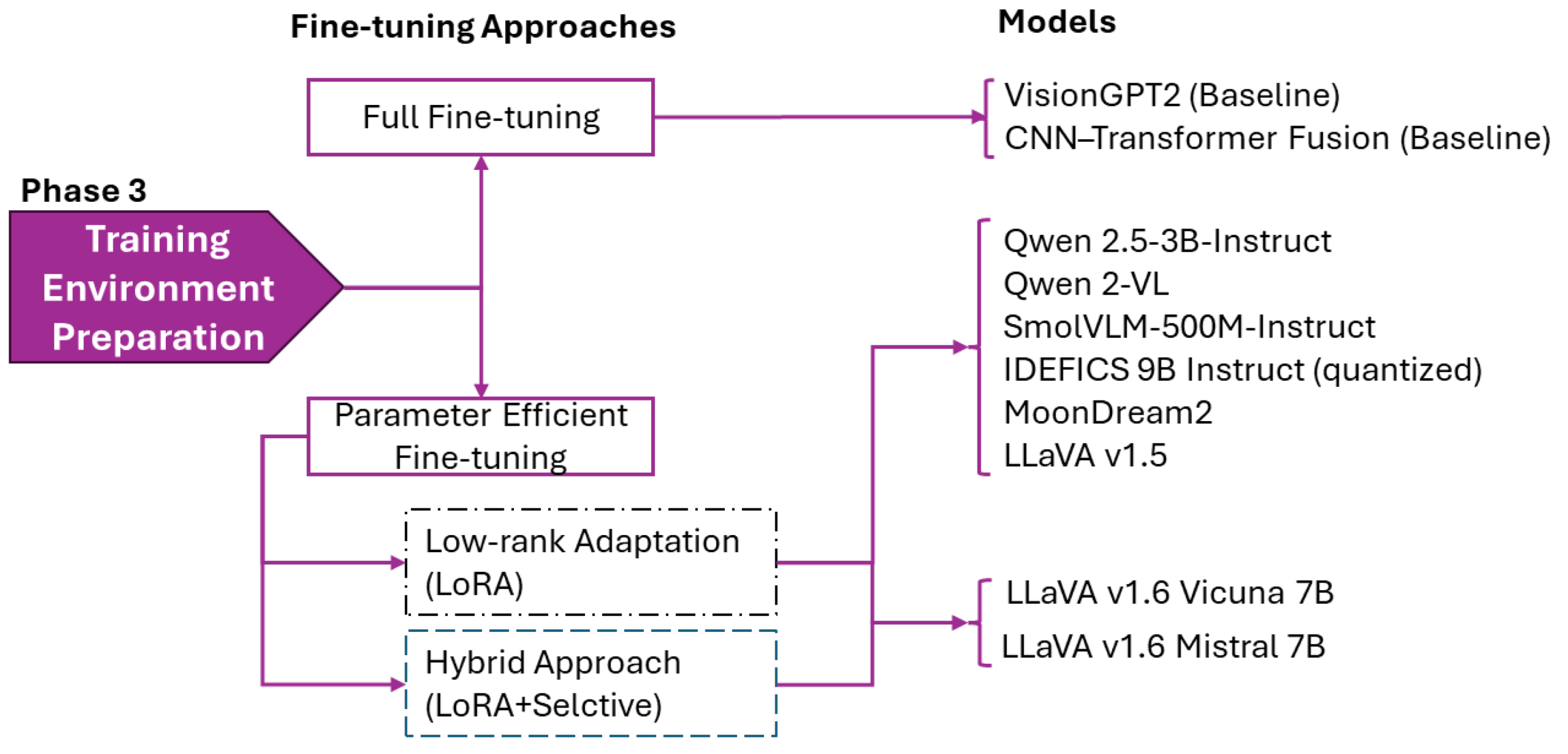

Figure 4.

Training strategy allocation for baselines models and VLMs.

Figure 4.

Training strategy allocation for baselines models and VLMs.

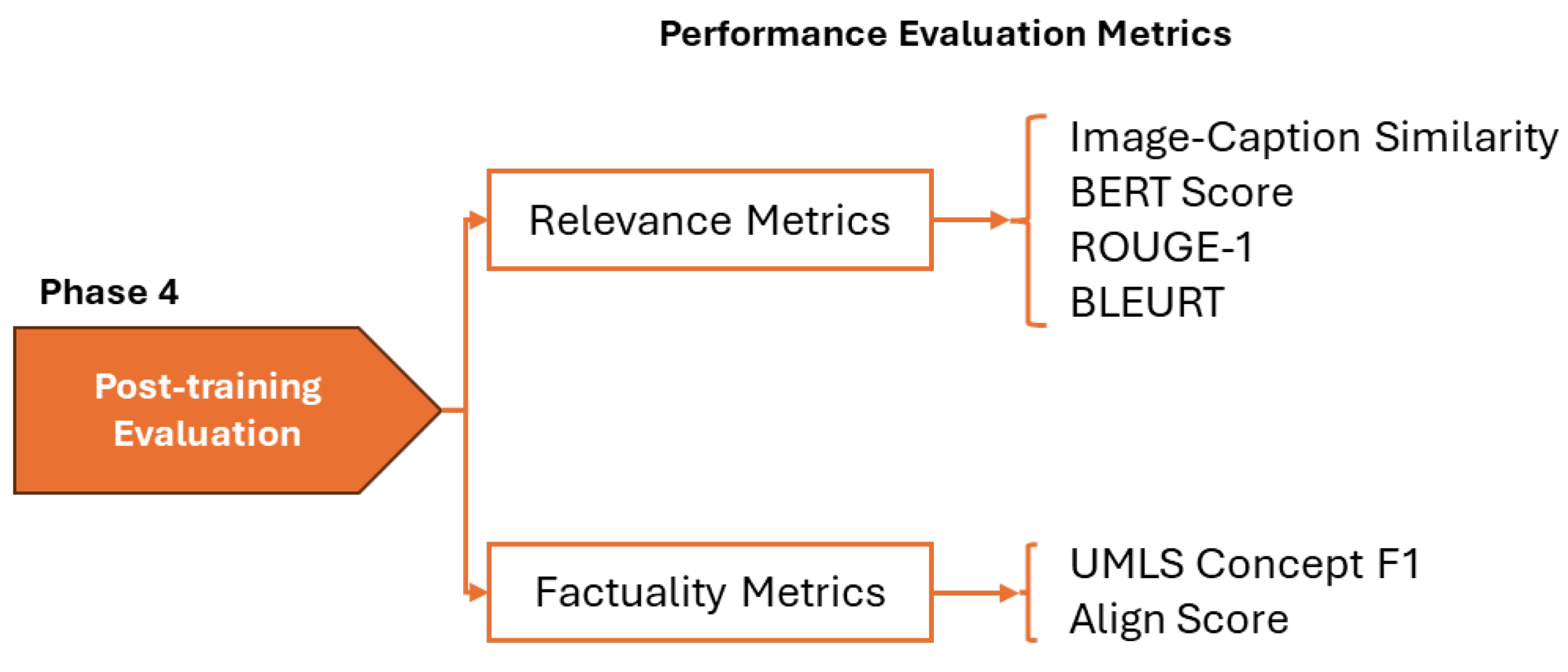

Figure 5.

Evaluation framework with relevance metrics used to assess caption quality.

Figure 5.

Evaluation framework with relevance metrics used to assess caption quality.

Figure 6.

Comparison of targeted, extended, and hybrid adaptation strategies for LLaVA-1.6 Mistral-7B across six evaluation metrics. The targeted approach, with 40.1M trainable parameters (0.53%), achieves the highest image-caption similarity and shows competitive performance on BERTScore, ROUGE, BLEURT, and the factuality metrics (UMLS Concepts F1 and AlignScore).

Figure 6.

Comparison of targeted, extended, and hybrid adaptation strategies for LLaVA-1.6 Mistral-7B across six evaluation metrics. The targeted approach, with 40.1M trainable parameters (0.53%), achieves the highest image-caption similarity and shows competitive performance on BERTScore, ROUGE, BLEURT, and the factuality metrics (UMLS Concepts F1 and AlignScore).

Figure 7.

Comparison of targeted and hybrid adaptation strategies for LLaVA-1.6 Vicuna-7B across six evaluation metrics. The targeted LoRA, with 34.4M trainable parameters (0.48%), consistently achieves stronger image-caption similarity and higher scores in BERTScore, ROUGE, BLEURT, as well as improved factuality (UMLS Concepts F1 and AlignScore), compared to the hybrid strategy that trains ten times more parameters.

Figure 7.

Comparison of targeted and hybrid adaptation strategies for LLaVA-1.6 Vicuna-7B across six evaluation metrics. The targeted LoRA, with 34.4M trainable parameters (0.48%), consistently achieves stronger image-caption similarity and higher scores in BERTScore, ROUGE, BLEURT, as well as improved factuality (UMLS Concepts F1 and AlignScore), compared to the hybrid strategy that trains ten times more parameters.

Figure 8.

Overall performance scores across model categories. LVLMs (blue) and SVLMs (orange) consistently outperform baseline models (red). The dashed line indicates the VisionGPT2 baseline performance (0.177), showing all LoRA-adapted models exceed this threshold. While LVLMs generally achieve higher performance than SVLMs, MoonDream2 represents a notable exception, achieving performance comparable to LLaVA-1.5 despite having approximately 74% fewer parameters.

Figure 8.

Overall performance scores across model categories. LVLMs (blue) and SVLMs (orange) consistently outperform baseline models (red). The dashed line indicates the VisionGPT2 baseline performance (0.177), showing all LoRA-adapted models exceed this threshold. While LVLMs generally achieve higher performance than SVLMs, MoonDream2 represents a notable exception, achieving performance comparable to LLaVA-1.5 despite having approximately 74% fewer parameters.

Figure 9.

Relationship between relevance and factuality performance across models. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient () indicates a strong monotonic relationship between the two dimensions. The fitted regression line explains approximately 85% of the variance (). Large VLMs (blue) cluster in the upper-right quadrant, demonstrating superior performance on both dimensions, while baseline models (red) occupy the lower-left region.

Figure 9.

Relationship between relevance and factuality performance across models. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient () indicates a strong monotonic relationship between the two dimensions. The fitted regression line explains approximately 85% of the variance (). Large VLMs (blue) cluster in the upper-right quadrant, demonstrating superior performance on both dimensions, while baseline models (red) occupy the lower-left region.

Figure 10.

Representative chest X-ray example from the test set with green arrow indicating a right-sided pleural effusion.

Figure 10.

Representative chest X-ray example from the test set with green arrow indicating a right-sided pleural effusion.

Figure 11.

Representative CT pulmonary embolus study from the test set showing pericardial effusion measuring 19.27 mm.

Figure 11.

Representative CT pulmonary embolus study from the test set showing pericardial effusion measuring 19.27 mm.

Table 1.

Distribution of imaging modalities in the ROCOv2 dataset.

Table 1.

Distribution of imaging modalities in the ROCOv2 dataset.

| Primary Modalities |

Count |

Percentage |

| CT |

40,913 |

35.1% |

| X-ray |

31,827 |

27.3% |

| MRI |

18,570 |

15.9% |

| Ultrasound |

17,147 |

14.7% |

| Other* |

8,178 |

7.0% |

Table 2.

Comparison of VLMs: encoders, decoders, connectors, and parameters.

Table 2.

Comparison of VLMs: encoders, decoders, connectors, and parameters.

| Model |

Image Encoder |

Text Decoder |

Connector / Fusion |

# Params (approx.) |

| IDEFICS 9B Instruct |

CLIP ViT-H/14 ( 1.3B) |

LLaMA-7B ( 7.0B) |

Perceiver + gated cross-attn ( 0.75B) |

9.0B |

| LLaVA v1.6 Mistral 7B |

CLIP ViT-L/14 (∼0.43B) |

Mistral-7B (∼7.0B) |

Projection + cross-attn (∼20–50M) |

7.6B |

| LLaVA v1.6 Vicuna 7B |

CLIP ViT-L/14 (∼0.43B) |

Vicuna-7B (∼6.7B) |

Projection + cross-attn (∼20–50M) |

7.1B |

| LLaVA v1.5 with LLaMA 7B |

CLIP ViT-L/14 (∼0.43B) |

LLaMA-7B (∼6.7B) |

Projection + cross-attn (∼20–50M) |

7.1B |

| Qwen 2.5-3B-Instruct |

Custom ViT (∼0.3B) |

Qwen LM (∼2.8B) |

Projection + cross-attn (∼50M) |

3.1B |

| Qwen 2-VL |

Custom ViT (∼0.3B) |

Qwen LM (∼1.9B) |

Projection + cross-attn (∼20M) |

2.2B |

| MoonDream2 |

SigLIP-base (∼0.15B) |

Phi-1.5 (∼1.7B) |

Projection + cross-attn (∼10M) |

1.86B |

| SmolVLM-500M-Instruct |

SigLIP-base (∼0.15B) |

Tiny LM (∼0.35B) |

Projection + cross-attn (∼10M) |

0.5B |

| VisionGPT2 |

ViT (∼0.05B) |

GPT2 small (∼0.12–0.15B) |

Cross-attention (∼5–10M) |

0.21B |

| CNN–Transformer Fusion |

Tiny CNN (∼10M) |

Tiny Transformer (∼30–35M) |

Direct feature fusion (∼3M) |

0.048B |

Table 3.

LoRA configuration parameters of the models.

Table 3.

LoRA configuration parameters of the models.

| Model |

Params Trained |

% of Total |

Adapter Scaling |

Target Modules |

| LVLMs |

| LLaVA-Mistral-7B |

40.1M |

0.53 |

2.0 |

q,k,v + MLP |

| LLaVA-Vicuna-7B |

34.4M |

0.48 |

1.0 |

q,k,v + MLP + mm_proj |

| LLaVA-1.5 |

84.6M |

1.18 |

1.0 |

q,k,v,o + MLP + mm_proj |

| IDEFICS-9B |

22.0M |

0.24 |

2.0 |

q,k,v only |

| SVLMs |

| Qwen-2.5-3B |

57.0M |

1.87 |

0.5 |

All attention + MLP |

| Qwen-2-VL |

54.0M |

2.46 |

1.0 |

All attention + MLP |

| MoonDream2 |

74.4M |

3.85 |

0.25 |

All linear + proj |

| SmolVLM-500M |

41.7M |

8.34 |

2.0 |

All linear |

| Baselines |

| VisionGPT2 |

210M |

100 |

– |

Progressive full FT |

| CNN-Transformer |

48M |

100 |

– |

Progressive full FT |

Table 4.

Performance comparison of vision-language models and baseline architectures.

Table 4.

Performance comparison of vision-language models and baseline architectures.

| Model |

Parameters Trained (%) |

Similarity |

BERTScore |

ROUGE |

BLEURT |

UMLS Concept F1 |

AlignScore |

Relevance |

Factuality |

Overall |

| Large VLMs (LoRA Adapter) |

| LLaVA Mistral-7B |

0.53 |

0.870 |

0.628 |

0.251 |

0.315 |

0.154 |

0.081 |

0.516 |

0.118 |

0.317 |

| LLaVA Vicuna-7B |

0.48 |

0.830 |

0.625 |

0.245 |

0.314 |

0.142 |

0.076 |

0.504 |

0.109 |

0.306 |

| IDEFICS-9B |

0.24 |

0.781 |

0.621 |

0.229 |

0.296 |

0.128 |

0.070 |

0.482 |

0.099 |

0.290 |

| LLaVA-1.5 |

1.18 |

0.720 |

0.617 |

0.218 |

0.295 |

0.108 |

0.059 |

0.462 |

0.083 |

0.273 |

| Small VLMs (LoRA Adapter) |

| MoonDream2 |

3.85 |

0.757 |

0.586 |

0.216 |

0.303 |

0.120 |

0.066 |

0.466 |

0.093 |

0.279 |

| Qwen 2-VL |

2.46 |

0.570 |

0.518 |

0.160 |

0.238 |

0.074 |

0.109 |

0.372 |

0.091 |

0.232 |

| SmolVLM |

8.34 |

0.414 |

0.536 |

0.136 |

0.252 |

0.016 |

0.060 |

0.362 |

0.038 |

0.200 |

| Qwen-2.5 |

1.87 |

0.449 |

0.453 |

0.124 |

0.256 |

0.048 |

0.064 |

0.320 |

0.056 |

0.188 |

| Baselines (Full Finetune) |

| VisionGPT2 |

All |

0.389 |

0.546 |

0.118 |

0.247 |

0.022 |

0.035 |

0.325 |

0.028 |

0.177 |

| CNN-Transformer |

All |

0.399 |

0.414 |

0.044 |

0.277 |

0.018 |

0.030 |

0.284 |

0.024 |

0.154 |

Table 5.

Impact of modality-aware prompting on SVLM performance. Modality labels were predicted by a ResNet-50 classifier and added at inference time.

Table 5.

Impact of modality-aware prompting on SVLM performance. Modality labels were predicted by a ResNet-50 classifier and added at inference time.

| Model |

Configuration |

Similarity |

BERTScore |

ROUGE |

BLEURT |

UMLS F1 |

AlignScore |

Relevance Avg |

Factuality Avg |

Overall |

| SmolVLM |

Base |

0.414 |

0.536 |

0.136 |

0.252 |

0.016 |

0.060 |

0.362 |

0.038 |

0.200 |

| SmolVLM |

+Modality |

0.418 |

0.532 |

0.144 |

0.266 |

0.031 |

0.096 |

0.365 |

0.048 |

0.207 |

| |

Change |

+1.0% |

-0.7% |

+5.9% |

+5.6% |

+93.8% |

+60.0% |

+0.8% |

+26.3% |

+3.5% |

| Qwen 2-VL |

Base |

0.570 |

0.518 |

0.160 |

0.238 |

0.074 |

0.109 |

0.372 |

0.091 |

0.232 |

| Qwen 2-VL |

+Modality |

0.364 |

0.456 |

0.121 |

0.311 |

0.017 |

0.086 |

0.313 |

0.052 |

0.182 |

| |

Change |

-36.1% |

-12.0% |

-24.4% |

+30.7% |

-77.0% |

-21.1% |

-15.9% |

-42.9% |

-21.6% |

| Qwen-2.5 |

Base |

0.449 |

0.453 |

0.124 |

0.256 |

0.048 |

0.064 |

0.320 |

0.056 |

0.188 |

| Qwen-2.5 |

+Modality |

0.502 |

0.461 |

0.122 |

0.268 |

0.032 |

0.065 |

0.351 |

0.049 |

0.200 |

| |

Change |

+11.8% |

+1.8% |

-1.6% |

+4.7% |

-33.3% |

+1.6% |

+9.7% |

-12.5% |

+6.4% |

Table 6.

Caption component analysis for the chest X-ray. Components are highlighted as: Image Modality, Pathological Finding, Anatomical Location, Laterality, Visual marker. Laterality and visual markers are caption elements that aid clinical interpretation but are not UMLS concepts.

Table 6.

Caption component analysis for the chest X-ray. Components are highlighted as: Image Modality, Pathological Finding, Anatomical Location, Laterality, Visual marker. Laterality and visual markers are caption elements that aid clinical interpretation but are not UMLS concepts.

| Ground Truth |

chestX-ray showing a right pleural effusion (green arrow) |

| LLaVA-Mistral-7B |

ChestX-ray showing a right-sided pleural effusion (green arrow) |

| LLaVA-Vicuna-7B |

ChestX-ray showing a large right-sided pleural effusion (green arrow) |

| LLaVA-1.5 |

ChestX-ray showing a large right-sided pleural effusion |

| IDEFICS-9B |

ChestX-ray showing a large right-sided pleural effusion (green arrow) |

| MoonDream2 |

ChestX-ray showing a right-sided pleural effusion (arrow) |

| Qwen 2-VL |

ChestX-ray of the patient shows an enlarged right-sided infiltrate in the right lower lobe (arrow) |

| SmolVLM |

An arrow pointing to a mass in the patient’s chest on a chest x-ray |

| Qwen 2.5 |

CT scan of the left kidney showing a renal cystic lesion (arrow) |

| VisionGPT2 |

A chest X-ray showing a large right-sided pneumothorax |

| CNN-Transformer |

Chestx ray in sagittal |

Table 7.

Caption component analysis for the CT scan. Components are highlighted as: Image Modality, Pathological Finding, Anatomical Location, Clinical Measurement. Clinical measurements are caption elements that aid clinical interpretation but are not UMLS concepts.

Table 7.

Caption component analysis for the CT scan. Components are highlighted as: Image Modality, Pathological Finding, Anatomical Location, Clinical Measurement. Clinical measurements are caption elements that aid clinical interpretation but are not UMLS concepts.

| Ground Truth |

CTpulmonary embolus study showing pericardial effusion measuring 19.27 mm in this plane |

| LLaVA-Mistral-7B |

CTpulmonary embolus study showing pericardial effusion measuring 19.27 mm in this plane |

| LLaVA-Vicuna-7B |

CTpulmonary angiogram showing pericardial effusion measuring 19.27 mm in this plane |

| LLaVA-1.5 |

CTpulmonary embolism showing a large right lower lobe pulmonary embolism |

| IDEFICS-9B |

CTpulmonary embolism study showing [truncated/incomplete] |

| MoonDream2 |

CT scan of the chest showing a large mass in the right upper lobe |

| Qwen 2-VL |

Computed tomography scan showed a large right-sided mass in the right side |

| SmolVLM |

A cross-section of a CT scan of the chest and abdomen, with a yellow square pointing to the 19.27 mm measurement |

| Qwen 2.5 |

Axial T2 magnetic resonance imaging of patient |

| VisionGPT2 |

PET-CT scan showing a large right hepatic cyst in the right hepatic lobe |

| CNN-Transformer |

CT scan showing enlargement in liver lesion |