1. Introduction

Over the past decade, artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a transformative force in healthcare systems worldwide [

1]. Beyond its clinical applications, AI is increasingly reshaping public health responses to the cascading effects of climate change by enhancing diagnostic precision, environmental surveillance, and social equity. AI-driven diagnostic platforms such as robot-assisted microscopy for malaria detection illustrate how low-cost automation can strengthen disease surveillance in regions where rising temperatures are expanding the geographic range of vector-borne infections [

2].

In critical care, researchers are developing translation tools powered by language models to bridge linguistic barriers during climate-driven health emergencies, thereby improving coordination and data sharing in intensive care units (ICUs) [

3].

At the environmental level, machine learning models are now predicting urban air quality with fine spatial granularity by coupling atmospheric physics with computational intelligence, enabling earlier interventions against pollution-related cardiopulmonary risks that are magnified by increasing heat [

4]. Besides, comparative analyses of support vector machines and neural networks in municipal solid waste management illustrate AI’s capacity to optimize recycling and waste reduction systems, key components for climate mitigation and healthier urban ecosystems [

5].

Moreover, equity-focused analyses of occupational safety emphasize how AI might both mitigate and exacerbate health disparities in a green transition, reminding us that technological innovation must be guided by justice [

6]. Validation studies comparing machine learning with traditional regression approaches confirm AI’s superior ability to capture nonlinear interactions between pollution, heat, and morbidity, offering a more adaptive framework for climate-health policymaking [

7].

In high-income countries (HIC), recent advances in large-scale, multimodal biomedical AI models have shown the potential to improve diagnosis, personalize treatment, and streamline clinical workflows across diverse domains, from oncology to cardiology and mental health [

8]. These technologies often leverage vast datasets that include medical imaging, genomic profiles, electronic health records, and patient-reported outcomes [

9]. The Transformer model architecture, self-supervised learning, and multimodal data inputs require massive Graphic Processing Unit (GPU) and computational power [

10].

These advances are particularly relevant for high-burden, climate-sensitive diseases such as cardiovascular conditions, where early detection and tailored intervention can dramatically alter outcomes. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), for example, illustrate our argument; they remain the leading cause of mortality worldwide [

11], and their burden is increasingly shaped by climate-related stressors, such as air pollution [

12], extreme heat [

13], and rising food insecurity [

14].

In this evolving epidemiological landscape, artificial intelligence offers powerful tools for risk prediction, early diagnosis, and personalized management of CVDs. Recent breakthroughs in large language models (LLMs) and multimodal AI systems have demonstrated a remarkable capacity to integrate clinical, genomic, imaging, biosensor, and environmental data to stratify cardiovascular risk and guide interventions with precision. These models can, for example, predict arrhythmic events from single-lead ECGs, assess heart failure risk through automated echocardiography, and potentially improve allocation of high-cost treatments such as implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) [

15].

AI foundation models developed in leading academic and corporate research centers now integrate diverse data streams to provide real-time decision support and prognostic insight in high-income countries [

16]. In contrast, their implementation in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) exposes a landscape of both opportunity and vulnerability, where innovation meets the persistent constraints of infrastructure, equity, and governance [

17].

In the context of the climate emergency, nations that dominate AI development will also possess the most advanced diagnostic and preventive capabilities [

18]. In this regard, López et al. [

19] warn that technological dependency on foreign vendors risks reproducing existing global inequities. They advocate for a transition toward AI sovereignty grounded in the use of locally curated datasets and context-sensitive algorithmic. This may strengthen national autonomy and resilience in digital health.

In this regard, certain methodological advances in AI offer promise for reducing dependency on large datasets and high-cost infrastructure. Transfer Learning (TL), a machine learning paradigm that allows models trained on one dataset or domain to transfer acquired knowledge to a different but related context. Instead of requiring models to be trained from scratch, TL leverages pre-trained representations to reduce computational burden, training time, and data dependency [

20,

21].

In healthcare, transfer learning (TL) has proven effective for enhancing diagnostic and prognostic modeling in resource-constrained settings, allowing researchers in low- and middle-income settings to adapt models originally developed in high-income countries to their own clinical conditions [

22,

23]. For instance, de Araújo et al. [

25] proposed a TL framework for early sepsis detection in intensive care units. Their model integrated genetic algorithms with ensemble classifiers and was trained on sparse, heterogeneous ICU datasets to achieve high predictive accuracy (AUC = 0.77). More importantly, it enabled clinicians to anticipate systemic deterioration several hours before standard clinical signs appeared, demonstrating the life-saving potential of TL when coupled with advanced computational optimization.

Researchers categorize TL methods according to the relationships between source and target domains, learning goals, and model strategies. The most widely used taxonomy distinguishes three main types: inductive, transductive, and unsupervised TL [

20]. Inductive transfer applies when tasks differ but labeled data are available in the target domain, a configuration commonly used in disease classification. Transductive transfer, also known as domain adaptation, becomes useful when tasks are similar but data distributions vary, such as across hospitals or countries. Unsupervised transfer learning operates in settings where no labeled data exist in either domain, which makes it particularly suitable for public health surveillance and large-scale epidemiological modeling. Together, these categories highlight the versatility of TL in addressing both clinical and population-level challenges.

In parallel, federated learning (FL) has become a key strategy for protecting data privacy while enabling collaborative model development. Instead of pooling data in a single repository, institutions train models locally and share only the resulting parameters and updates. This process allows each site to contribute to the model's collective improvement while keeping sensitive patient information securely within its own environment [

25,

26].

Decentralized architectures suit healthcare in LMICs, where data are scattered across systems with strict privacy rules. FL enables secure, scalable AI by reducing data sharing and keeping control local. Recent approaches, such as FedNCA, have tailored FL for low-resource settings, optimizing for edge devices and limited connectivity [

27].

Brazil's involvement in global federated learning has demonstrated that privacy-preserving models are practical for cardiovascular and cancer research, even with data kept locally [

26,

28]. These experiences demonstrate that FL models can integrate seamlessly with public health systems like the Brazilian Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde, SUS), fostering distributed innovation and ensuring that locally generated data strengthen globally relevant AI development.

In 2024, Brazil committed BRL 2.3 billion over four years to boost its AI capabilities, funding a sovereign supercomputer and public sector projects in health, education, and social inclusion. At the core of this initiative lies the principle of “IA para o bem de todos” (AI for the common good), which positions technological progress to foster equity, autonomy, and sustainable development [

29]. This vision is being operationalized in healthcare through the consolidation of the SUS Digital Program, which emerged from two decades of regulatory maturation in telehealth [

30].

As Haddad et al. [

30] explain, Brazil’s digital health transformation began with early teleconsultation programs under Telessaúde Brasil Redes (Brazil’s Telehealth Network in English). It advanced to a new phase in 2023 with the creation of the Secretaria de Informação e Saúde Digital (SEIDIGI), a vice-ministerial body dedicated to information and digital health. In 2024, the Ministry of Health launched the Meu SUS Digital (My Digital SUS in English) through ministerial ordinances. The program seeks to expand infrastructure, promote data interoperability, and ensure the ethical use of AI across all levels of the health system.

Given Brazil’s recent digital health transformations, this study examines how artificial intelligence is being applied in Brazilian healthcare through a structured narrative review, with a focus on TL and FL, that we believe addresses resource constraints and technological dependency. As a middle-income country with a complex and universal health system, Brazil offers a critical example of how adaptive AI approaches such as TL and FL can operate under resource constraints while advancing methodological and data sovereignty.

2. Methods

Search Strategy

We conducted a structured narrative review to synthesize how AI is being applied across healthcare domains in Brazil. Although our search followed systematic procedures, the heterogeneity of study designs and outcomes led us to adopt a narrative thematic synthesis rather than a meta-analytical approach. In the methods, we sought to prioritize transparency, scalability, and relevance for researchers working in low-resource settings.

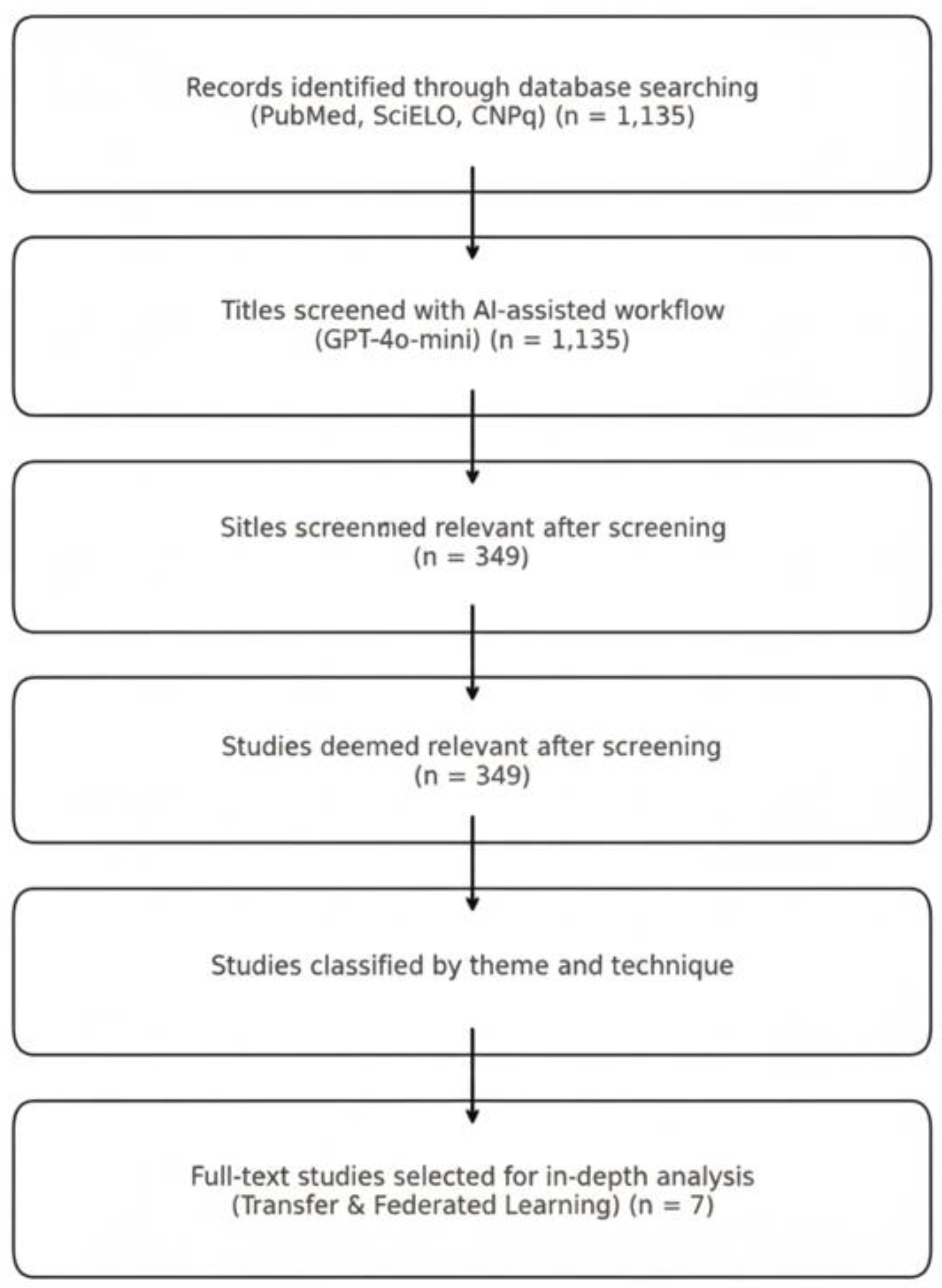

We searched for studies on AI in Brazilian healthcare using three sources: PubMed, SciELO, and the CNPq Theses and Dissertations Repository. Each search string combined controlled vocabulary and free-text terms, including “artificial intelligence,” “health,” and “Brazil.” We adapted each query to the syntax of its respective database.

Appendix A provides the complete search strategies. We completed the search in July 2025 and retrieved 1,135 (see supplement S1) records. The search strategy was conducted by the coauthor Machado GM.

To avoid losing unique studies from heterogeneous sources, we retained all entries without deduplication. Because many CNPq records lacked abstracts, we screened them solely by title. We exported all titles into a structured spreadsheet that included metadata such as year and source.

AI-Assisted Screening Workflow

We used the GPT-4o-mini language model via the OpenAI API to streamline the screening process and assess feasibility in low-resource environments.

The instruction prompt provided to the model was:

“You are a researcher participating in a systematic review. Your job is to screen studies and decide upon the inclusion and exclusion criteria below, if they should be included in the review. Make your decision only based on the given criteria, title and abstract. Answer it with ‘Include’ if the study should be included, and ‘Exclude’ otherwise.

Eligibility criteria: You want to map Artificial Intelligence projects, studies, and research done in Brazil.”

A zero-shot classification prompt in Portuguese instructed the model to label each title as “Include,” “Maybe,” or “Exclude,” based on a single criterion: whether the study discussed artificial intelligence applied to healthcare in Brazil. We submitted titles in batches of 10 using Google Colab on a standard CPU laptop, without GPU acceleration or fine-tuning.

Appendix B describes the full implementation. To maximize sensitivity, we treated all “Maybe” responses as “Include.” This conservative approach ensured that we did not overlook borderline cases during the AI-assisted screening phase.

Human Validation and Consensus

After the model classified the titles, human reviewers (coauthors Borges FT and Sancho KA) independently validated a subset without access to the model’s decisions. They resolved any disagreements through discussion. This hybrid strategy allowed us to scale the screening process efficiently while maintaining methodological rigor. It also demonstrated the potential of large language models (LLMs) to support research workflows in resource-constrained settings, a critical need in low- and middle-income countries.

Study Selection and Thematic Classification

We screened 1,135 titles and identified 349 studies (see supplement S2) that met our inclusion criteria by addressing artificial intelligence applications in Brazilian healthcare. We manually classified these studies by their primary themes, including Telehealth, Diagnostic AI, Public Health Surveillance, TL, FL, and Low-Resource Model Optimization (which also included TL and FL).

We charted all included studies in a standardized spreadsheet to support synthesis. From this pool, we selected seven studies for full-text review and in-depth analysis. These focused specifically on TL and FL and served as representative cases for our qualitative synthesis.

3. Results

We analyzed seven academic studies on TL and FL. Six of these studies draw their data from South America, specifically from Dayan et al. [

25], Lorenzer et al. [

28], Sheller et al. [

26], and Araújo Moura et al. [

31]. The seventh study integrates U.S. data presented by Stanford et al. [

32] and includes research contributions from a Brazilian academic institution within a consortium. This selection offers a balanced view across different regions while highlighting collaborative approaches in investigating TL and FL. As shown in

Table 1, these initiatives range from single-institution experiments in TL [

33,

34] to complex, multi-institutional and FL consortia involving partners across three continents [

26].

As shown in

Figure 1, we began with a broad and inclusive search strategy to capture the full spectrum of artificial intelligence applications in Brazilian healthcare. Our goal was to understand the overall landscape before identifying specific methodological patterns. We did not set transfer learning (TL) or federated learning (FL) as inclusion criteria; rather, they emerged from the analysis as central approaches addressing Brazil’s resource and infrastructure constraints. This exploratory design allowed us to compare national adoption patterns with those observed in high-income countries and to identify areas of convergence and persistent gaps in computational feasibility and scalability. By subsequently focusing on TL and FL, we were able to highlight AI innovations that respond to local healthcare needs rather than merely replicate global trends.

Of the 349 studies screened and validated by ChatGPT and humans, the most common topics were pattern recognition, health research, and applications in the Brazilian SUS. Other prominent themes included public policies and the use of TL or FL techniques. Several studies spanned multiple categories, reflecting the interdisciplinary nature of AI research in healthcare. This thematic distribution underscores both the diversity of AI applications in Brazil and the growing importance of approaches tailored to resource-constrained contexts.

Although pattern recognition and diagnostic support dominated the Brazilian AI landscape, our review reveals a critical underrepresentation of approaches explicitly designed for low-resource environments.

Table 2 presents a qualitative synthesis of the seven studies selected for full-text analysis, each of which applied either TL, FL, or other model optimization strategies suitable for low-resource settings. Only a small fraction of the 349 studies focused on strategies to reduce computational cost or enhance model generalizability using limited data.

The study by Dayan et al. [

25] implemented a FL framework across 20 international hospitals to predict clinical outcomes for COVID-19 patients, including in-hospital mortality. By training decentralized models across diverse institutions without transferring patient data, the authors demonstrated that FL achieved performance comparable to or superior to that of centralized models, with AUC scores exceeding 0.80 across multiple sites. This approach preserved data privacy while enabling cross-institutional learning, a significant advantage in contexts with fragmented health systems and privacy constraints, such as Brazil’s SUS.

However, the authors also noted challenges, including data heterogeneity, inconsistent clinical coding, and coordination overhead. Those barriers that would need to be addressed for successful implementation in resource-limited environments.

The study by Lorenzer et al. [

28] focused on the foundational challenges of applying FL across international hospital networks by harmonizing electronic medical record (EMR) data from Austria, Germany, and Brazil. Their objective was to prepare a unified dataset for training models to predict major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). Brazil’s contribution came from the Ribeirão Preto Medical School at the University of São Paulo (USP). Despite differences in coding systems and data granularity, the researchers successfully standardized features using international terminologies, such as the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10), Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC), and Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System (ATC). Nevertheless, this process was labor-intensive and revealed deep structural challenges, especially in mapping medication and laboratory data, which required extensive manual work and clinical expertise. Their work provides a valuable blueprint for how institutions in Brazil and elsewhere might participate in federated modeling without compromising data privacy, but it also underscores the need for national-level infrastructure and semantic standardization for broader scalability.

In one of the earliest large-scale FL implementations in medical imaging, Sheller et al. [

26] trained a tumor boundary segmentation model for glioblastoma using data from 17 institutions across North and South America, including the USP. The study aimed to address the challenge of rare cancer detection, where data scarcity is a persistent barrier to effective model training. By employing a federated architecture, the authors enabled collaborative learning without centralized data aggregation, achieving a mean Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) of 0.78, which was comparable to fully centralized training. The study also highlighted several limitations, including communication overhead, variability in data quality, and the complexity of model versioning. Despite that, the findings underscore the feasibility of privacy-preserving big data analytics for rare diseases, which often lack sufficient local data in middle-income countries like Brazil.

The study led by Ramos et al. [

33] explores the use of TL to automate malaria diagnosis by detecting Plasmodium vivax in microscopic blood smear images using a dataset of 6,222 Regions of Interest (ROIs). They primarily sourced from the Broad Bioimage Benchmark Collection (BBBC) and supplemented by locally collected images from the Brazilian Amazon. Then trained and evaluated six deep neural networks. Among them, DenseNet201 consistently outperformed others, achieving an AUC of 99.41% and demonstrating statistically superior performance across most classification metrics. Notably, the study incorporated rough circular segmentation and did not rely on manual feature engineering or complex preprocessing, enabling an efficient pipeline suitable for low-resource environments. By validating results through 100-fold cross-validation and including leukocyte images, a common source of diagnostic error, the study highlighted both robustness and generalizability. This work exemplifies how TL, when carefully tailored to local epidemiological and infrastructural conditions, can yield high-accuracy diagnostic tools with minimal computational cost.

Sanford et al. [

32] investigated how to improve the generalizability of automated prostate segmentation models using TL and advanced data augmentation techniques. The study trained a deep learning model on 648 prostate MRI exams from a single center and tested it on five external datasets. A hybrid 2D-3D convolutional neural network (CNN), incorporating pre-trained ResNet-50 layers, was used for segmentation. The authors applied “deep stacked transformation” (DST) as a domain-specific data augmentation strategy and also fine-tuned the model using samples from the target institutions. These combined approaches improved the Dice similarity coefficient (DSC) by up to 2–3% for both whole-prostate and transition-zone segmentations, with final mean DSCs reaching 91.5 and 89.7, respectively. Notably, the model demonstrated resilience across diverse MRI vendors, scanning protocols, and institutional settings, highlighting TL as a key enabler of robust AI tools in heterogeneous, and resource-diverse healthcare systems.

Araujo-Moura et al. [

31] applied TL to enhance hypertension prediction among South American children and adolescents using multicenter data from the SAYCARE study. Initially, models trained on a children's dataset achieved high accuracy (>0.90), but showed poor generalizability to the adolescent sample due to limited and more variable data. By transferring knowledge from the well-performing child model to adolescent predictions using CatBoost, Random Forest, and other tree-based algorithms, researchers significantly improved model performance, achieving an AUC-ROC of 0.82 for CatBoost. The study further employed SHAP analysis to interpret the contribution of individual variables, revealing that lifestyle factors such as soft drinks, chips, and filled cookies consumption were strong predictors of elevated blood pressure. This work highlights how TL not only improves model accuracy in data-scarce settings but also helps reveal context-sensitive risk factors that may support public health interventions across multiple countries, including LMICs.

In her master’s thesis, Dias [

34] developed a machine learning model to predict systemic arterial hypertension using data from the 2013 Brazilian National Health Survey (Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde – PNS, in Portuguese). The study applied the J48 decision tree algorithm due to its simplicity, transparency, and low computational demand. Those characteristics are well-suited to public health contexts such as the Brazilian SUS. The final model reached an accuracy of 74.5%, with a sensitivity of 83.4% and a specificity of 63.3%. Among the most important predictive variables were age, BMI, diabetes diagnosis, and reported cardiovascular issues. The study emphasized interpretability and ease of deployment, suggesting the model could be integrated into basic health surveillance systems to support early diagnosis and resource prioritization. While not positioned within the deep learning field, the thesis aligns with the goals of low-resource model optimization and demonstrates how straightforward machine learning pipelines can meet pressing public health needs in resource-constrained settings.

4. Discussion

The studies reviewed ranged from malaria diagnosis in the Brazilian Amazon to cardiovascular prediction in multinational consortia. The seven studies reviewed converge on a common purpose: to develop AI models that respond to contextual constraints rather than replicate solutions conceived for high-resource settings. Across transfer learning applications [

31,

32,

33,

34] and federated learning initiatives [

25,

26,

28], each study acknowledges data scarcity, heterogeneity, and limited computational infrastructure as structural realities shaping the practice of AI in health. Collectively, they embody an emerging paradigm of context-aware innovation, in which methodological adaptability becomes a strategy for overcoming the systemic inequities that have historically limited technological autonomy in LMIC.

Ramos et al.’s [

33] work at Fiocruz Rondônia demonstrates how locally acquired image data from the Amazon can be integrated with international datasets (BBBC) to develop malaria detection models through TL. The approach, anchored in methodological simplicity and computational frugality, achieved state-of-the-art accuracy (AUC = 99.4%) using lightweight convolutional architectures. By employing rough segmentation and texture-based classification, the study demonstrated that low-resource optimization can coexist with high diagnostic performance. Its strength lies precisely in its minimalism: a model trained under constrained infrastructure that remains statistically robust.

Similarly, the ML extended these principles to population health, using primary care data from the SUS [

34]. By predicting hypertension risk from structured administrative records, it confronted not only technical but also infrastructural asymmetries, such as fragmented information systems, inconsistent clinical coding, and incomplete datasets. Dias [

34] underscored that data preprocessing and standardization outweighed algorithmic sophistication in shaping model performance. In both studies of Ramos et al. [

33] and Dias [

34], the central insight is straightforward: contextually adapted models that respect data scarcity and heterogeneity can yield scalable and equitable solutions, provided they align with the organizational realities of public health systems.

At a larger scale, FL enables collective model development without centralizing sensitive health data. The Federated Tumor Segmentation (FeTS) initiative [

26] operationalized this principle across 71 institutions worldwide, including Brazil’s USP. By training a tumor boundary detection model for glioblastoma on distributed MRI data, the study achieved near-centralized performance (Dice ≈ 0.78) while maintaining data privacy. Its findings show that data diversity, not centralization, drives model generalization. Yet, the study also exposed the significant coordination overhead inherent in federated architectures: software versioning, communication latency, and governance asymmetry. These barriers reflect, in miniature, the broader institutional fragmentation of systems like the SUS. The promise of FL is inseparable from questions of infrastructure, funding, and interoperability governance.

The EXAM Model for COVID-19 outcome prediction [

25] further advanced this paradigm. Involving 20 institutions across four continents, including São Paulo, Brazil, the consortium demonstrated that federated training could yield predictive accuracy (AUC ≈ 0.92) comparable to centralized models while preserving full data sovereignty. By predicting oxygen therapy needs using multimodal EMR and chest X-rays, the study delivered an ethical, rapid-response model during the pandemic’s peak, according to the authors. Importantly, it employed differential privacy and partial weight-sharing, ensuring that computation traveled while data stayed. This principle redefines the power dynamics of global AI collaboration. Instead of exporting data for algorithmic enrichment abroad, institutions participate in a distributed intelligence network that respects legal, ethical, and contextual boundaries.

Both the FeTS and EXAM studies demonstrate that FL is not only a technical framework but also a governance model, which ideally could reconcile collaboration with autonomy. In LMIC, where infrastructural limitations and data sovereignty concerns coexist, such architectures can transform participation from dependency into co-production.

The most recent PRE-CARE ML project [

28] extends these insights to the domain of semantic interoperability. By harmonizing EMR data from Austria, Germany, and Brazil to predict major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), the consortium revealed that the most profound obstacles to FL are not computational but semantic. Harmonization required the manual alignment of ICD-10, LOINC, and ATC codes across languages, institutions, and data architectures. The Brazilian node at Ribeirão Preto Medical School of the USP had to translate clinical terminologies into standardized taxonomies, creating bilingual mapping tables collaboratively with European partners. Emerging consensus that semantic openness is a prerequisite for ethical federation

Sanford et al. [

32] demonstrate that TL, when coupled with structured augmentation, creates a bridge between single-center research and multi-center applicability. This resonates with your broader claim that Brazil’s path to AI autonomy depends on mobilizing TL and FL to translate global architectures into local health contexts. In practical terms, this study’s combination of DST augmentation + fine-tuning can be viewed as a proto-federated strategy/ Stanford (2020) anticipated the governance mechanisms later realized in the FeTS, EXAM, and PRE-CARE ML consortia.

As shown in

Table 2, most studies applying federated and transfer learning were conducted through institutional consortia that brought together partners from high-, upper-middle-, and lower-middle-income countries. These collaborations proved that scalable AI innovation can emerge from shared infrastructures that distribute both knowledge and computational capacity across diverse settings. Although federated and transfer learning remain far from mainstream techniques, their successful use within these consortia demonstrates the feasibility of cross-income cooperation in developing context-aware, privacy-preserving, and generalizable models. This experience shows that building scalable AI capacity does not depend solely on high-resource environments but on cooperative frameworks that pool expertise, align governance standards, and enable equitable participation in advanced AI research.

Methodological Limits of Transfer Learning and Federated Learning

TL enables researchers to reuse pre-trained models to improve performance in data-scarce biomedical settings, reducing computational demands and accelerating clinical AI development.¹ However, its adoption exposes key vulnerabilities. Negative transfer remains common, as poorly matched source domains can degrade performance and obscure causal reasoning [

35]. The process by which pretrained weights influence predictions often lacks interpretability, reinforcing the black-box nature of deep learning and limiting clinical trust [

36]. Privacy and governance challenges persist: fewer than 5% of studies implement TL within compliant, privacy-preserving frameworks, and most require direct access to source data, which restricts participation by low-resource institutions [

35]. Emerging “source-free” TL methods, which use shared model artifacts instead of raw data, are promising but appear in only about 2% of studies [

35,

36,

37]. Without stronger interpretability, privacy safeguards, and standardized model-sharing protocols, TL risks remaining a technically efficient but ethically fragile approach.

FL enables multi-institutional training under strict data-governance constraints and achieves performance comparable to centralized benchmarks in several biomedical applications. Clinical translation is currently limited, with approximately 5% of studies reporting real-world deployment [

38]. Persistent non-IID heterogeneity continues to cause gradient conflicts and model drift, reducing convergence and generalizability [

39]. Security also remains fragile: many implementations still transmit updates without encryption, and FL by itself guarantees governance but not true privacy, leaving systems vulnerable to inversion and reconstruction attacks [

40]. Integrating privacy-enhancing technologies such as DP-SGD, SMPC, or HE partially mitigates these risks but introduces a measurable privacy–utility trade-off [

41]. Moreover, the architecture does not eliminate the black-box opacity of deep learning models, limiting clinical interpretability and trust [

38]. Future progress depends on advancing personalized FL and governance mechanisms capable of managing heterogeneity while ensuring secure, scalable, and explainable AI [

42].

Strenghs

We designed this study for full reproducibility by conducting all analyses on standard CPU-based computing environments. This approach shows that researchers can generate meaningful bibliometric and methodological insights without relying on high-performance hardware. By using accessible infrastructure, we reproduced the real computational conditions of many research institutions in low- and middle-income countries and demonstrated that rigorous AI research remains feasible under resource constraints.

A key strength of this study lies in its broad and inclusive search strategy, which captured the full spectrum of artificial intelligence applications in Brazilian healthcare before narrowing the focus to transfer and federated learning. This approach allowed emergent identification rather than predefined selection of relevant methodologies, strengthening the validity and comprehensiveness of the analysis. By situating TL and FL within the wider national landscape, the study provides a more contextual and representative understanding of Brazil’s AI adoption patterns, avoiding the bias of topic-restricted reviews.

Limitations

We recognize several limitations in this study. We restricted our analysis to peer-reviewed academic publications, which may exclude relevant gray literature and ongoing projects within government or industry. We analyzed only studies published in English and Portuguese, which may have led to the omission of research disseminated in other languages. Although our narrative synthesis allowed us to identify key methodological and contextual trends, it did not include a quantitative meta-analysis, which limits the ability to measure effect sizes or statistical associations. Our interpretation also depends on the quality of reporting within the included studies; incomplete metadata or inconsistent terminology may have affected comparability across sources.

We used AI-assisted title screening to increase efficiency and consistency during the initial selection phase. However, automated classifiers can prioritize familiar terminology and overlook interdisciplinary or locally grounded studies that use less standardized language. The algorithm may also inherit linguistic and geographic biases from its training data, overrepresenting research from high-income settings and underrepresenting studies from LMIC contexts. Although we manually validated to correct these issues, we acknowledge that AI-based screening remains sensitive to data composition and parameter settings, which can affect inclusiveness and reproducibility.

Future research should refine these methods by integrating multilingual screening tools, transparent model documentation, and broader data sources to ensure more equitable representation of global AI research and practice.

Need for Further Studies

Future research should focus on developing resource-aware, and scalable AI strategies that perform reliably under data scarcity, computational limitations, and infrastructural diversity typical of LMIC health systems. Few existing studies address these challenges directly, and even fewer provide validated frameworks for integrating such models into public health governance. There is also a need for systematic evaluation of FL and TL in real-world clinical workflows, particularly within primary care and population surveillance programs. Future research can examine how cooperative governance models, which integrate national autonomy with international collaboration, may affect data sovereignty and innovation across health systems of varying capacities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Fabiano Tonaco Borges, Gabriela do Manco Machado, Maíra Araújo de Santana, Karla Amorim Sancho, Giovanny Vinícius Araújo de França, Wellington Pinheiro dos Santos, and Carlos Eduardo Gomes Siqueira; Methodology, Gabriela do Manco Machado, Fabiano Tonaco Borges, and Maíra Araújo de Santana; Validation, Karla Amorim Sancho and Fabiano Tonaco Borges; Formal analysis, Karla Amorim Sancho, Fabiano Tonaco Borges, and Maíra Araújo de Santana; Investigation, Fabiano Tonaco Borges and Karla Amorim Sancho; Resources, Wellington Pinheiro dos Santos; Data curation, Karla Amorim Sancho and Fabiano Tonaco Borges; Writing-original draft preparation, Fabiano Tonaco Borges; Writing—review and editing, Fabiano Tonaco Borges, Gabriela do Manco Machado, Maíra Araújo de Santana, Karla Amorim Sancho, Giovanny Vinícius Araújo de França, Wellington Pinheiro dos Santos, and Carlos Eduardo Gomes Siqueira; Visualization, Fabiano Tonaco Borges; Supervision, Wellington Pinheiro dos Santos and Carlos Eduardo Gomes Siqueira; Project administration, Maíra Araújo de Santana ; Funding acquisition, Wellington Pinheiro dos Santos.