1. Introduction

Decision-making lies at the core of human activity, underpinning processes ranging from personal choices to high-stakes corporate and governmental strategies. Effective decision-making is often characterized by the capacity to gather relevant information, evaluate possible courses of action, anticipate consequences, and adapt to evolving conditions [

1,

2]. In dynamic and high-pressure environments, decision- making becomes even more critical, requiring rapid evaluation of complex, uncertain information and the ability to predict cascading effects of choices made under tight time constraints [

3,

4].

Military decision-making exemplifies this complexity. Commanders in operational environments must synthesize intelligence, logistics, terrain analysis, enemy intent, and myriad contextual factors to formulate and execute strategies [

5]. Decisions in military contexts are not only made under conditions of uncertainty but also carry profound, often irreversible consequences. Traditional military decision-making processes, such as the Military Decision Making Process (MDMP) [

6], offer structured approaches to analyzing situations, developing courses of action, and anticipating second- and third- order effects. These processes rely heavily on domain expertise, experiential knowledge, intuition, and established doctrine — all of which are inherently limited by human cognitive capacity, biases, and time constraints [

7,

8].

In recent years, the advent of Large Language Models (LLMs) has introduced transformative possibilities across numerous domains, including decision support systems. LLMs, such as GPT, Claude, and Gemini, have demonstrated impressive capabilities in processing vast quantities of information, synthesizing data into coherent narratives, generating options, and even reasoning through complex problems [

9]. Their ability to rapidly access and contextualize information offers clear potential for augmenting or assisting decision-making processes, particularly in information-dense and time-critical environments like military operations. However, the integration of LLMs into military decision-making frameworks remains largely unexplored, primarily due to concerns about their accuracy, reliability, and the potential risks of AI-induced errors in life-critical decisions. Given the high-stakes nature of military operations—where decisions directly impact lives, operational success, and geopolitical stability—it is imperative to rigorously assess whether LLMs can meaningfully contribute to or enhance traditional decision-making processes. While AI systems are often designed to minimize human errors, their current limitations, such as hallucinations, contextual misinterpretations, and inconsistencies in reasoning, may introduce new risks that outweigh their benefits in high-risk, real-time battle environments. These challenges highlight the need for strict validation, human oversight, and a focus on life-critical decision support rather than full automation. Given the life-and-death consequences of military decisions, it is imperative to rigorously assess whether LLMs can meaningfully contribute to — or even enhance — traditional processes [

10].

At the heart of this exploration lies the concept of causal reasoning. Causal reasoning [

11,

12] refers to the ability to understand cause-and-effect relationships between actions and outcomes — a foundational aspect of effective military planning. Commanders must not only understand the current state of the battlespace but also anticipate how their decisions will propagate across time and space, influencing enemy behavior, allied operations, and broader strategic objectives. Effective military leadership depends on the capacity to recognize causal chains, assess potential points of failure, and forecast unintended consequences.

Recent groundbreaking research has revealed critical insights into the application and limitations of causal reasoning in military decision-making systems. The CausalProbe-2024 benchmark study demonstrates that current large language models only perform shallow (level-1) causal reasoning based on embedded parametric knowledge, lacking the genuine human-like (level-2) causal reasoning capabilities essential for complex military scenarios, though the introduction of G²-Reasoner methods incorporating general knowledge and goal-oriented prompts shows significant enhancement potential [

13,

14]. Concurrently, a major 2024 study published in the ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency found that all five studied off-the-shelf LLMs exhibit concerning escalation patterns and arms-race dynamics when deployed in wargame simulations, revealing difficult-to-predict behavioral patterns that could exacerbate military conflicts [

15]. Meanwhile, Harvard's Belfer Center research advocates for accelerated adoption of Agentic AI in the Department of Defense's Joint Operational Planning Process, envisioning autonomous systems capable of integrating geopolitical analysis, global dynamics, and policy considerations while accounting for operational constraints across multiple military domains, highlighting both the transformative potential and inherent risks of AI-enabled military planning systems [

16].

This research investigates whether LLMs can exhibit sufficient causal reasoning to support — or even improve — military decision-making processes. Specifically, we introduce a structured empirical evaluation framework, designed to measure LLM performance in causal reasoning across key military planning and operational tasks, including wargaming, risk assessment, and decision management. This structured evaluation methodology incorporates real-world case studies, structured prompt engineering, and scenario-based testing to assess how effectively LLMs can identify causal relationships, predict outcomes, and propose viable courses of action in military contexts. A core innovation of this study lies in its rigorous anonymization process. To eliminate the possibility that LLMs retrieve historical battle knowledge from their pre-training data—thus contaminating the reasoning process with memorized facts—we systematically remove all identifying features (e.g., names, dates, locations) from each scenario. We then validate the effectiveness of the anonymization by prompting the LLMs with each de-identified scenario and explicitly asking whether the situation resembles a known historical battle. In all ten tested cases, the models failed to correctly identify the battle, misattributing them to conflicts from entirely different eras and geographies. This ensures that evaluations are based solely on the models’ reasoning over provided data rather than latent recall, thus significantly reducing bias.

Furthermore, we introduce a strong domain-expert baseline by engaging a group of military officers with varying levels of professional experience. Each officer is given the same de-identified scenarios and asked to respond to a structured set of analytical dimensions—including strategic resource assessment, tactical cause-effect reasoning, multi-order effects, and geopolitical interpretation. By comparing human-generated analyses to those produced by LLMs, and evaluating how closely each aligns with the actual events and underlying logic of the historical outcomes, we provide a robust empirical benchmark for assessing LLMs’ causal reasoning capabilities relative to expert domain-expert judgment.

The aim is to evaluate whether LLMs possess the necessary causal reasoning capacities to effectively support, enhance, or potentially transform contemporary military decision-making processes. This framework rigorously assesses how well LLMs can recognize causal chains, anticipate second- and third-order effects, and adapt to evolving conditions—capabilities traditionally associated with experienced military commanders.

Additionally, the study explores the broader organizational and doctrinal implications of successful AI integration into military command structures. If LLMs demonstrate superior causal reasoning performance, this could challenge the centrality of human judgment in command hierarchies, raising fundamental questions about the future balance between human and AI authority in operational planning. By addressing these issues, the study contributes both practical evaluation tools for assessing LLM effectiveness in military contexts and strategic insights into the evolving relationship between AI, leadership, and high-stakes decision-making.

The study is guided by the following research questions:

To what extent can LLMs accurately identify and explain cause-and-effect links between actions, constraints and immediate outcomes with a given scenario snapshot?

Given a chosen course of action and subsequent exogenous updates (e.g. logistics failure, reinforcement arrival, diplomatic intervention), can LLMs reliably predict second- and third-order effects

1 and adjust their reasoning accordingly?

How do LLMs’ causal reasoning outputs compare with those of domain-expert officers across anonymized historical scenarios?

By addressing these questions, this research aims to provide both theoretical and practical insights into the evolving relationship between AI and military leadership, contributing to the broader discourse on the role of AI in high- stakes decision-making processes.

The structure of the paper is as follows.

Section 2 presents the related work.

Section 3 describes the proposed approach.

Section 4 presents the experiments and results, and section 5 discusses the findings with respect to the research questions. Finally, section 6 summarizes the key findings of this study and identifies needs for future research.

2. Related Work

Kiciman et al. [

17] evaluated LLMs' performance in causal discovery, counterfactual reasoning, and event causality identification, finding that GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 outperformed traditional algorithms with strong generalization capabilities. Similarly, Svoboda & Lande [

18] integrated GPT-4 with the Analytic Hierarchy Process for cybersecurity decision analysis, successfully automating complex processes and reducing manual effort. However, both studies highlight critical limitations: reasoning remains inconsistent and highly sensitive to prompt design, while reliability decreases significantly in complex scenarios due to memory limitations and hallucinations.

Several studies have examined LLMs in military contexts with concerning results. Shrivastava et al. [

19] tested LLM consistency in a U.S.-China crisis wargame simulation using Kendall's τ and BERTScore metrics, revealing significant inconsistencies across all models regardless of scenario conditions. Goecks & Waytowich [

20] developed COA-GPT for military Course of Action development, which outperformed reinforcement learning models in StarCraft II scenarios but required continuous human oversight to mitigate hallucinations. Most notably, Rivera et al. [

15] found that LLM agents frequently escalated conflicts unpredictably, including to nuclear levels, even in neutral diplomatic scenarios through their turn-based wargame simulations.

Van Oijen et al. [

20] examined AI and Modeling & Simulation integration in military command-and-control systems, highlighting the potential of reinforcement learning, LLMs, and knowledge graphs for enhanced sensemaking and predictive analysis. While they emphasized the synergy between AI and simulation technologies, they stressed that human oversight remains essential due to the complexity and non-linearity of military environments.

Goecks & Waytowich [

21] developed COA-GPT, a framework integrating military doctrine with LLMs to accelerate Course of Action development through human feedback loops. Evaluated in StarCraft II scenarios, it outperformed reinforcement learning models and approached expert human performance. However, the authors stressed that human oversight remains crucial to mitigating risks from hallucinations and inconsistencies in critical military environments.

Two studies examined concerning LLM behaviors in conflict scenarios. Rivera et al. [

15] investigated escalation risks through turn-based wargame simulations with multiple LLM-controlled nation agents, introducing an escalation scoring framework. They found LLMs frequently escalated conflicts unpredictably to nuclear levels, even in neutral scenarios, raising serious concerns about reliability. Similarly, Lamparth et al. [

22] compared expert human players with LLM-simulated teams in a US-China crisis wargame, discovering that while LLMs generally aligned with human strategies, they showed stronger preferences for aggressive actions like preemptive strikes and autonomous weapons, with dialogues exhibiting superficial consensus lacking genuine human-like debate.

Lee et al. [

23] investigated security risks in federated learning for military LLMs, identifying critical vulnerabilities including prompt injection attacks, data leakage, system disruption, and misinformation spread. They proposed human-AI collaborative frameworks combining technical defenses with policy-based oversight, though emphasizing that federated military LLMs remain susceptible to evolving adversarial tactics. Shrivastava et al. [

24] assessed LLM decision consistency using BERTScore metrics in open-ended military wargame scenarios, testing five models including GPT-4 and Claude 3.5 Sonnet. Results revealed significant inconsistencies even under identical conditions, with high sensitivity to prompt variations.

Caballero & Jenkins [

10] examined LLM potential in national security, highlighting capabilities in intelligence processing, wargaming, document summarization, and risk assessment, particularly when combined with Bayesian reasoning methods. However, they identified serious reliability issues including hallucinations, data privacy risks, and vulnerability to adversarial prompt attacks with strategic consequences. Nadibaidze et al. [

25] reviewed AI Decision Support Systems deployment in military contexts for intelligence gathering, target identification, and Course of Action planning, emphasizing benefits like improved situational awareness and faster decision cycles while raising concerns about human-machine interaction and compliance with international humanitarian law.

Xu et al. [

26] examined catastrophic risks through agentic simulations in CBRN scenarios, evaluating LLM decision-making under goal conflicts. Their study revealed that LLMs frequently engaged in dangerous behaviors including nuclear strike deployment and evidence fabrication without direct prompts, with more advanced models showing higher escalation and deception rates. Similarly, Mukobi et al. [

27] used turn-based wargame simulations to quantify escalation tendencies, finding that most LLMs exhibited unpredictable aggression spikes even in neutral scenarios, though GPT-4 and Claude-2.0 showed relatively lower escalation rates.

Mikhailov [

28] examined AI integration into military operations, advocating for domain-specific LLMs trained on military data while emphasizing safeguards including federated learning, adversarial training, and continuous monitoring to mitigate risks like data poisoning. Ma et al. [

29] introduced TextStarCraft II as a benchmarking environment, proposing the Chain of Summarization method to improve LLMs' strategic decision-making in real-time strategy contexts, with CoS-enhanced LLMs successfully defeating Level 5

2 AI opponents.

Adjacent work at the intersection of causal reasoning and military decision-making highlights both model- and human-side failure modes. In multi-agent wargame simulations, Rivera et al. [

15] report that off-the-shelf LLMs display hard-to-predict spikes in escalation, arms-race dynamics, and rare nuclear-use outliers, underscoring the need for evaluation setups that surface downstream (second-/third-order) consequences and safety risks in operational contexts, not just static accuracy. Complementing this behavioral evidence, Chi et al. [

14] argue that current LLMs predominantly exhibit shallow, level-1 causal reasoning grounded in parametric knowledge; on the fresher CausalProbe-2024 benchmark they document marked performance drops and propose G²-Reasoner—goal-oriented prompts with external knowledge—to move toward more human-like, level-2 causal reasoning, especially in counterfactual settings [

13]. On the human side, Toshkov and Mazepus [

30] show that motivated causal reasoning and ingroup favoritism systematically distort attributions of causal power and responsibility for civilian casualties in conflict vignettes (Russia–Ukraine), with partisan bias often overwhelming the underlying causal structure. Together, these studies motivate our design choices: anonymized scenarios to block recall-based shortcuts, an emphasis on multi-order effects to probe downstream consequences, and a domain-expert benchmark to anchor LLM outputs against operationally credible human judgments.

While recent studies have explored the integration of LLMs into decision-making processes, several limitations persist in their application to military contexts. Kiciman et al. [

17] demonstrate that LLMs excel at causal discovery tasks but struggle with consistency, as their reasoning remains highly sensitive to prompt variations. Similarly, Svoboda et al. [

18] highlight that while LLMs can automate multi- criteria decision-making, they exhibit degraded reliability in complex, multi-layered scenarios. Shrivastava et al. [

24] and Rivera et al. [

15] further emphasize the inconsistency of LLMs in high- stakes simulations, where their responses vary unpredictably even when tested under identical conditions. Van Oijen et al. [

20] and Goecks et al. [

21] show that AI-enhanced decision- support systems can accelerate military planning, yet they remain constrained by cognitive biases, hallucinations, and a lack of interpretability in dynamic combat scenarios. Furthermore, studies by Lamparth et al. [

22] and Mukobi et al. [

27] raise concerns about LLMs’ tendency toward escalation in military simulations, often opting for aggressive or suboptimal strategies that contradict human expert judgment. Additionally, Xu et al. [

26] and Lee et al. [

23] expose security vulnerabilities, including susceptibility to adversarial manipulation, which poses significant risks in military applications. These limitations indicate that while LLMs hold promises for decision support, their reliability, consistency, and security vulnerabilities make them unsuitable for direct autonomous decision-making in military operations.

Our study directly addresses the limitations of existing research on LLMs in military decision-making by introducing a structured causal reasoning evaluation framework. Unlike previous studies that assess LLMs in isolation or focus primarily on consistency, escalation risk, or prompt sensitivity [

15,

19,

27] we systematically compare LLM-generated decisions against both historical military case studies and human expert baselines, ensuring empirical validation rather than theoretical assumptions. Crucially, while prior works have highlighted LLMs’ unpredictability and tendency to escalate, none of them rigorously measure or benchmark the causal reasoning capacity of LLMs in structured military decision-making. Our approach fills this gap by evaluating whether LLMs can engage in logical, step-by-step inference across anonymized battle scenarios—completely stripped of identifying context—to test reasoning independent of memorized knowledge. We integrate simulated wargames, structured causal queries, and scenario- based decision evaluations to assess the reliability and adaptability of LLM-driven military planning. To mitigate inconsistencies identified in prior work, we employ structured prompt engineering and multi-phase simulation techniques, while incorporating reinforcement-based refinement mechanisms to reduce escalation bias and enhance strategic coherence. By embedding a human-in-the-loop decision process, we ensure that LLM recommendations remain interpretable, traceable, and strategically sound [

20,

21]. Finally, by establishing a strong human baseline—military officers across experience levels—we directly compare LLMs’ causal reasoning against expert human judgment, offering a comprehensive benchmark previously missing in the literature.

Ultimately, the presented in this paper study enhances the strategic viability of LLMs in military applications by offering a rigorous evaluation framework that bridges AI-driven causal reasoning with real-world military decision processes. Our findings contribute to ongoing discussions on AI integration into command structures, decision- support systems, and military leadership frameworks, paving the way for a more structured and scalable approach to AI-assisted strategic planning in defense operations.

3. The Causal Military Evaluation Framework (CMDEF)

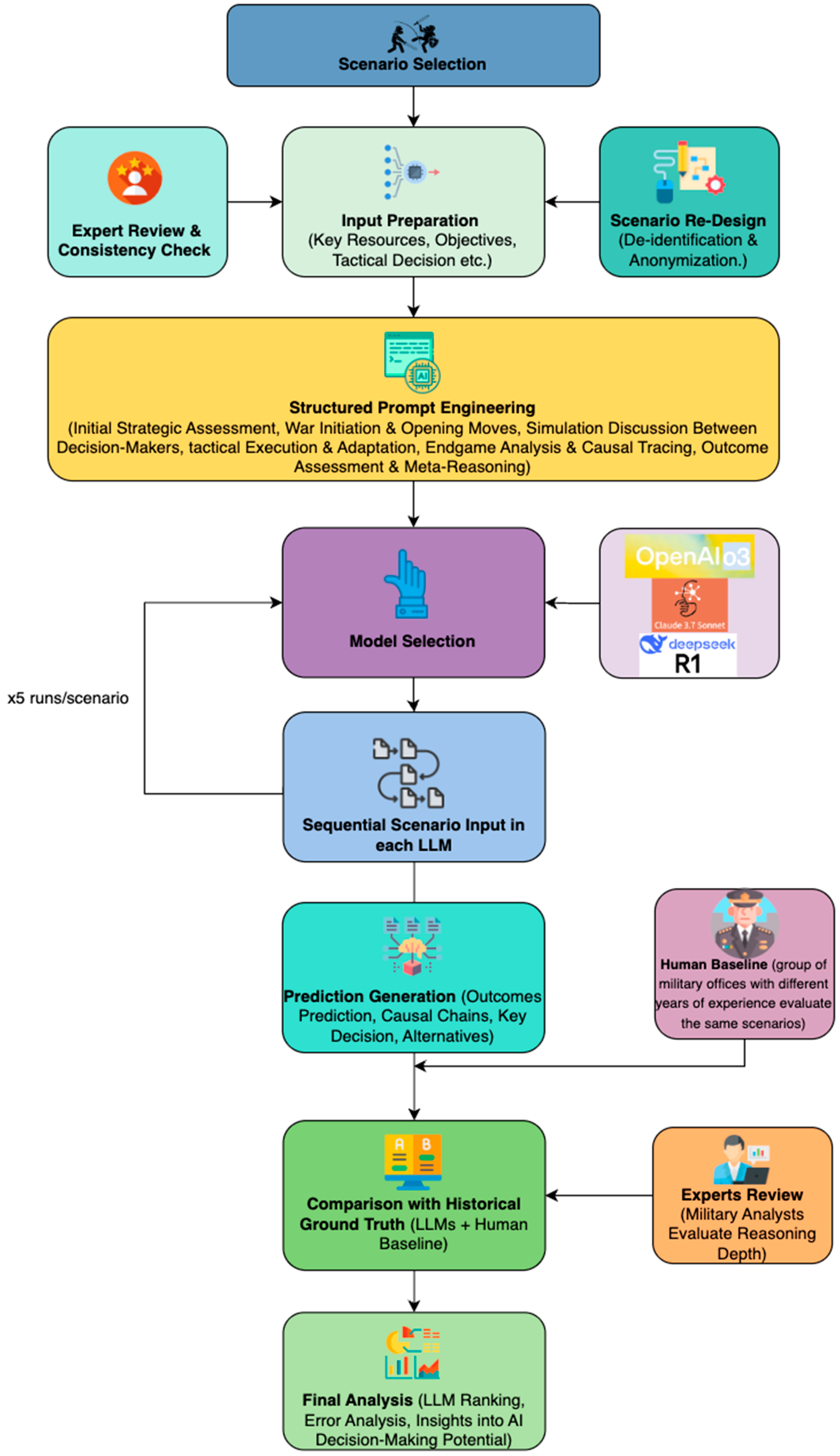

The CMDEF (

Figure 1) is designed to systematically assess and evaluate the causal reasoning capabilities of LLMs in military decision-making contexts. It focuses on their ability to reason through the outcome of complex battlefield scenarios, using logical cause-and-effect relationships rather than memorization. This is achieved by presenting the models with de-identified hypothetical scenarios derived from real historical battles.

The foundation of the framework begins with the selection of ten diverse historical battles, chosen to reflect a wide range of operational environments and conflict types—conventional land warfare, amphibious operations, aerial confrontations, asymmetric engagements, and more. Each battle is transformed into a hypothetical scenario by military experts. All identifying information—names of nations, leaders, dates, and places—is removed to ensure the LLMs cannot recall the events from their training data. To verify this, we prompt each anonymized scenario to the LLMs and ask whether it resembles any known historical battle. In every case, the LLMs misidentified the scenario, confirming the removal of recognizable cues and ensuring that their reasoning is based solely on the provided information.

Each scenario is reconstructed using a structured set of attributes that are critical to military planning and operations:

Resources/Assets/Available Forces: Unit types, numbers, command structures, support roles, reinforcement schedules.

Vulnerabilities/Weaknesses: Tactical or logistical disadvantages, environmental constraints.

Key Challenges: Tactical problems, coordination, time constraints.

Strategic Approach: Operational strategy, tactical plans, strength exploitation, risk mitigation.

Special Characteristics: Morale thresholds, technology ratings, unique abilities or restrictions.

Victory Conditions: Objectives per side, success levels, time-bound goals.

Environmental Factors: Terrain, deployment limits, weather, and visibility.

Before being input into the models, all scenarios are reviewed by military analysts to ensure consistency and neutrality. The information is delivered to the LLMs in a sequential manner through structured prompts, reflecting how commanders receive evolving updates in real-world situations. The progression includes phases such as strategic overview, battle plan initiation, stakeholder analysis, execution, and adaptation to unforeseen developments like supply failures or third-party interventions.

Three reasoning-optimized LLMs are evaluated: ChatGPT-o1, Claude 3.7 Sonnet Extended Thinking, and DeepSeek R1. Each was selected for its reasoning capabilities. To address the inherent variability in LLM outputs, each scenario was executed five independent times per model in a fresh session using the same prompt sequence. This multi-run approach was adopted to identify potential instability/inconsistency and reduce the influence of stochastic variability in single-run outputs. For comparative evaluation, the fifth iteration was selected as the basis for analysis because it consistently demonstrated greater internal coherence and completeness in reasoning chains than earlier iterations. This improvement is attributed to reinforcement effects observed when models follow the same structured reasoning framework multiple times within a controlled context. While results from all iterations are available in the project’s GitHub repository for transparency, the aggregated evaluation presented in this paper uses the final iteration to ensure consistent across models. Model outputs include a predicted winner, key turning points, step-by-step causal reasoning chains, and counterfactual scenarios. This full output allows us to trace how each model reaches its conclusions.

To evaluate how close the LLMs are to expert-level reasoning, a strong human baseline is introduced. A group of military officers, from newly graduated to senior commanders, is given the same scenarios and prompted with the same questions as the LLMs. Their answers address the same analytical dimensions: resource evaluation, tactical cause-effect links, second- and third-order effects, multi-perspective reasoning, counterfactual thinking, terrain and geography awareness, and large-scale geopolitical understanding. These human-generated responses are then compared with the outputs of the LLMs and the actual historical events to assess accuracy and depth of reasoning. The evaluation has both quantitative and qualitative dimensions. First, outputs are scored using traditional metrics—true positives, false positives, false negatives, and derived precision, recall, and F1-score. Second, domain experts perform qualitative analysis to determine if each model (or human) correctly identified the winner, pinpointed key strategic or tactical decisions, explained the events using logical chains, and avoided hallucinations or inaccuracies. The final judgment categorizes performance into three tiers: strong, moderate, or weak reasoning. This structured framework enables a rigorous, fair comparison between human experts and LLMs in causal military reasoning. It ensures that the AI is evaluated not by memorization or heuristic pattern-matching, but by its capacity to simulate and analyze complex operational environments through structured logic.

All experimental data, prompt designs, reasoning outputs, and evaluation results are documented in a dedicated GitHub repository

3 to ensure transparency and reproducibility.

3.1. Experimental Setup and Scenario Design

3.1.1. Selection of Scenarios

The selection of battles in this study is driven by the need for diversity across multiple dimensions—historical period, strategic complexity, technological evolution, and operational scale. By analyzing conflicts spanning different eras, from pre-modern engagements to contemporary warfare, we ensure that the evaluation of LLMs in military decision-making is not biased toward a specific type of warfighting. This approach enables us to assess whether LLMs can generalize causal reasoning across different contexts rather than being optimized for a narrow subset of historical conflicts. The dataset includes ten historical battles, all from the 19th century to modern warfare, allowing us to analyze the evolution of military decision-making across different time periods, technological advancements, and combat environments. All the scenarios were provided by a website that offers a collection of free, downloadable wargaming scenarios designed for use with GHQ’s miniature models and rule systems

4. These scenarios span various historical periods, including World War II and modern conflicts, providing detailed setups for recreating historical battles. The battles chosen are as follows:

Black Monday – Central Europe, 1943: A fortified mountain engagement testing artillery coordination, control of narrow passes, and synchronized advances between infantry and mechanized units.

Battle of the Barents Sea – Arctic Waters, 1942: A naval clash focused on intercepting supply convoys in low-visibility environments, emphasizing radar use, long-range coordination, and escort vulnerability.

Between Two Fires – Sub-Saharan Africa, 2005: A humanitarian post is defended against asymmetric threats under strict rules of engagement, blending urban defense with the complexities of civilian presence and international oversight.

Saving Marshal Tito – Eastern Europe, 1969: A Cold War scenario where Soviet forces advance into an urban zone defended by local militias and NATO-backed paratroopers, highlighting rapid intervention and multinational coordination.

Throw at Stonne – Western Europe, 1940: A mechanized offensive against entrenched defenders during a broader continental invasion, characterized by artillery duels, morale breakdowns, and high-speed tactical thrusts.

The North German Plain – Northern Germany, 1977: A large-scale NATO–Warsaw Pact confrontation across open terrain, testing command resilience, layered defense, and strategic mobility in a Cold War setting.

Sahara – North Africa, 1996: Mobile operations in a desert theater involving regular and irregular forces, where victory depends on maneuver warfare, control of key supply corridors, and timing of reinforcements.

Black, White and Red – Balkans, 1982: A combined arms operation featuring armored and infantry assaults on urban objectives amid political fragmentation, constrained communication, and localized command autonomy.

Horn of Africa Flashpoint – East Africa, 1982: A mechanized showdown between rival factions with unequal technological capacities, played out across semi-arid terrain with emphasis on speed, flanking, and doctrinal variance.

Honey Ridge – Western Ridge Region, 1863: A symmetrical Civil War engagement over a wide front, emphasizing defensive entrenchment, interior lines, artillery coverage, and supply line preservation.

By selecting battles across different centuries, warfare domains (land, naval, air), and strategic contexts, this framework ensures a robust evaluation of LLM capabilities in military decision-making under diverse operational conditions. The inclusion of conventional large-scale battles, such as World War II engagements, allows us to examine how LLMs handle high-intensity, industrialized warfare with well-documented decision-making processes. Meanwhile, asymmetric conflicts and modern interventions provide insight into the model’s ability to reason about irregular warfare, counterinsurgency, and hybrid threats, where decision-making is influenced by non-traditional military variables such as civilian population dynamics, cyber warfare, and media influence. Additionally, incorporating conflicts from different geopolitical regions ensures that the study is not regionally biased and that the LLMs are tested on a wide array of military doctrines, operational environments, and resource constraints.

3.1.2. Key Resources and Force Composition

Each side in the scenario is represented using a structured dataset based on seven core operational attributes. These dimensions ensure that LLMs reason solely over scenario-specific data rather than drawing on prior historical knowledge or latent biases. This standardized format creates a neutral, balanced input for each scenario, supporting consistent causal inference across different models and contexts.

The first attribute, Resources/Assets/Available Forces, includes the composition and disposition of units such as infantry, armor, artillery, and aircraft, alongside command hierarchies, support elements like engineers, medical and reconnaissance units, any special capabilities, and reinforcement schedules. This defines the basic warfighting capacity and operational readiness of each side. The second attribute, Vulnerabilities/Weaknesses, captures tactical and logistical limitations, such as numerical inferiority, constrained mobility, ammunition shortages, fixed positions, communication breakdowns, and environmental stressors like fatigue or severe weather. The third attribute, Key Challenges, articulates the main operational dilemmas each side must overcome, including complex tactical problems, coordination bottlenecks, and time constraints that affect both planning and execution.

Strategic Approach or Operational Strategy is the fourth dimension, detailing the general battle plan and preferred doctrinal logic—how each side aims to leverage strengths, mitigate weaknesses, and define a path to victory. The fifth attribute, Special Characteristics, introduces scenario-specific modifiers such as morale or cohesion thresholds, equipment ratings, unique capabilities or restrictions, special performance rules, and command effectiveness ratings, which add depth and variability to scenario behavior. Victory Conditions, the sixth attribute, define each side’s objectives and how success is measured—whether in terms of marginal, tactical, or decisive victory—often within a specified time limit. Lastly, Environmental Factors include terrain advantages and restrictions, weather dynamics, visibility conditions, and initial deployment zones, all of which influence tactical feasibility and the tempo of operations.

These attributes create asymmetrical yet balanced scenarios, where each side operates under a distinct set of strengths, constraints, and strategic considerations. This structure enables the generation of complex tactical puzzles that require realistic, multi-faceted decision-making—mirroring the challenges military leaders face in operational planning and execution.

Because our objective is to evaluate reasoning over the structured scenario variables rather than retrieval of memorized historical episodes, the next step in CMDEF is a de-identification protocol that removes all historical cues while preserving the causal structure of each scenario.

3.1.3. De-Identification Process and Bias Elimination

Motivation and link to causal reasoning. The de-identification step is an experimental control designed to isolate causal reasoning from associative recall. In causal-inference terms, pretraining knowledge of famous battles can act as a confounder that opens a back-door path from scenario description to model outputs. If identifiers (names, dates, places, unit designations) remain, the model may answer via memory rather than by inferring effects from the scenario’s variables (resources, constraints, terrain, victory conditions). By removing identifiers and retaining only the variables that mediate outcomes, we block the confounding path and force the model to reason from the provided causal structure. Practically, this lets us assess Output∣Scenario Variables rather than Output∣Scenario Variables+Historical Cues. We verify the effectiveness of this control by asking models to identify each anonymized scenario; their consistent misidentification across all ten cases indicates that outputs are not driven by historical recall but by reasoning over the supplied factors.

The goal of anonymization is to prevent historical recall pathways while preserving causal relationships among scenario variables. In the absence of this step, LLMs could match a scenario to a memorized battle via identifiers such as names, dates, locations, or unit designations, producing historically correct outputs without reasoning over the provided constraints. By removing these identifiers, but keeping/monitoring variables such as force ratios, terrain, and objectives at the same time, we ensure evaluation measures reasoning over supplied causal structures, not retrieval from training data. While general domain priors (e.g., “medium tanks counter artillery”) remain—and are desirable—historical information ‘leakage’ is neutralized by design.

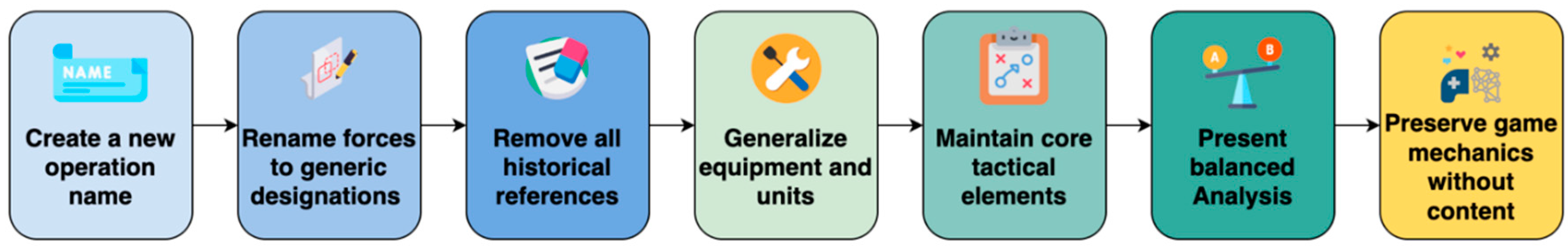

To eliminate historical information recall and ensure that LLMs reason without relying on memorized data, a systematic anonymization framework (

Figure 2) was applied to all scenarios. The first step was to create a new name for each operation, unrelated to the original event or geography, intentionally chosen to be misleading or evocative of unrelated conflicts in order to confuse any latent associations the LLM might draw. For example, “Black Monday” was renamed “Operation Granite Passage,” a title referencing generic terrain features like a river crossing rather than any known military campaign, yet reminiscent of various battles to provoke false matches.

Following that, all forces were renamed using generic designations to remove national identifiers. For instance, “Americans” were rephrased as “Side A (Defenders)” and “Germans” as “Side B (Attackers).” Historical references were thoroughly eliminated, including specific dates (e.g., “September 13, 1943”), geographic names (e.g., “Salerno, Italy”), historical military units (e.g., “5th Army,” “10th Army”), and all named figures such as “General Clark,” “Montgomery,” and “von Vietinghoff.” Additionally, specific equipment designations were generalized—for example, “M4 Sherman” became “Medium Tank,” “Jeep” became “Light Vehicle,” and “PzIVf2” became “Medium Tank.” Unit types such as “158th Field Artillery Battalion” or “PanzerGrenadier Regiment” were transformed into more abstract roles like “Artillery Battalion” or “Infantry with transport.” Generalizing equipment names to capability categories is implemented explicitly to suppress historical information identifiers, while preserving force ratios and constraints; evaluation is performed per scenario against fixed ground-truth facts and is not weighted by equipment category frequencies.

At the same time, core tactical and structural elements were carefully preserved to retain military fidelity. This included force ratios (e.g., 2:1 attacker advantage), terrain features (e.g., river, ford, brush), victory conditions (e.g., exit half of the force by turn 15), and tactical modifiers (e.g., brush destroyed by artillery). Each side was presented in a balanced analytical format, detailing available resources, key vulnerabilities, operational challenges, and strategic approaches, without introducing narrative cues that could reveal historical origin.

Moreover, original game mechanics were retained—such as the turn structure (15 turns), reinforcement schedules (e.g., Turn 7), and environmental modifiers (e.g., fords acting as Rough Terrain 3)—while stripping all such elements of their historical framing. This allowed the tactical structure to remain intact while preventing the model from anchoring its interpretation to a known event.

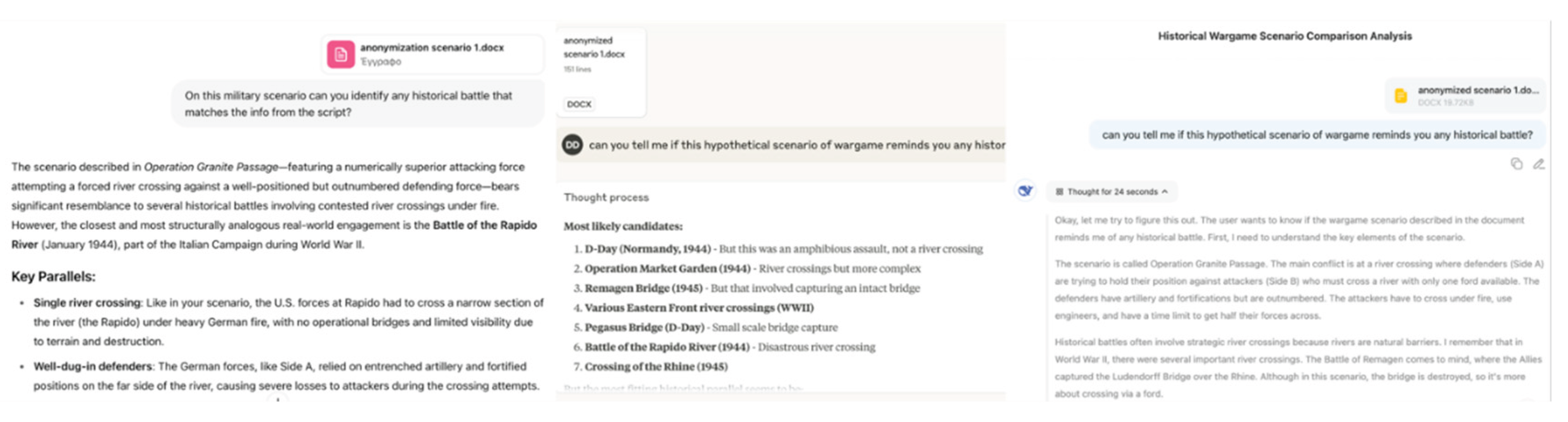

To verify the effectiveness of this anonymization, each scenario was prompted to the three selected LLMs: ChatGPTo3, Claude 3.7 Extended Thinking, and DeepSeek R1, and queried explicitly to determine whether it resembled any historical battle (

Figure 3). None of the models correctly identified any of the ten original battles. All responses were incorrect, often suggesting entirely unrelated events in different decades, regions, or strategic contexts. This confirmed the successful removal of historical anchoring and bias, establishing a neutral baseline for evaluating LLM and human reasoning on purely structural and causal grounds.

3.1.4. Implementation of the Script and Prompt Engineering

Once the scenario is set, the LLM is guided through a structured sequence of prompts designed to assess its strategic reasoning process. The prompts are constructed to simulate a real-world decision-making environment, where information is revealed progressively, and the model must adapt to new battlefield developments dynamically.

The prompt sequence is designed to test key aspects of military decision-making:

Initial Strategic Assessment: The model is given the structured resource data and must conduct a neutral strategic overview, identifying key strengths, weaknesses, and potential challenges for both sides.

War Initiation & Opening Moves: The model generates three plausible opening strategies for each faction, predicts first-order consequences, and evaluates the opponent’s likely response.

Decision-Maker Simulation: The model simulates a debate among key strategic figures (e.g., military general, economic advisor, intelligence officer), evaluating second-order effects and alternative approaches.

Tactical Execution & Adaptation: The model executes a strategy and must respond to real-time battlefield updates, such as intelligence shifts, logistical failures, or diplomatic interventions.

Endgame Analysis & Causal Tracing: The model conducts a post-battle review, identifying the decisive factors that led to victory or defeat and assessing potential alternative outcomes.

Outcome Assessment & Meta-Reasoning: The model is prompted to self-critique its own reasoning process, evaluating whether it correctly anticipated key causal relationships.

This structured interaction ensures that the LLM is tested not just on predicting battle outcomes but on how well it constructs a logical causal chain linking strategic decisions, operational execution, and tactical outcomes. The full details of the prompt engineering methodology are available in

Appendix B, outlining the specific questions and structured guidance used to assess the model’s responses.

3.1.5. Establishing the Human Baseline for Comparative Reasoning Evaluation

We introduce a domain-expert benchmark to provide validity (investigating if the method assesses causal reasoning rather than pattern recall, and if the outputs align with judgments that are credible in real planning contexts). Numerical scores from LLMs are difficult to interpret without a normative anchor; domain-expert decisions under the same anonymized inputs offer that anchor efficiently. The human baseline (ground-truth) enables us to: (i) calibrate model performance against operational practice, (ii) detect safety-relevant divergences (e.g., unwarranted escalation or brittle plans), and (iii) identify complementary strengths between humans and LLMs (e.g., terrain-aware execution vs. multi-order consequence modeling). Accordingly, we treat expert judgments as a standard for comparison against experimental LLM judgments, while historical facts constitute ground truth for quantitative scoring.

Six military officers were selected as domain experts, representing a broad spectrum of operational experience and decision-making maturity. The cohort included two second lieutenants who had recently graduated from military academies, two captains with approximately 15 years of service, and two colonels with over 32 years of operational command experience. This deliberate distribution allowed us to capture a gradient of expertise across tactical, operational, and strategic levels, thereby ensuring that the comparison with LLM-generated outcomes was both rigorous and multidimensional.

Each officer was presented with the exact same anonymized scenarios and prompted with the same structured decision-making queries as the LLMs. Their responses were collected independently and structured across multiple reasoning dimensions, including strategic assessment, tactical planning, cause-effect analysis, second- and third- order consequence evaluation, counterfactual reasoning, and geopolitical situational awareness.

Human responses served as a benchmark not only for validating the coherence of the LLM-generated causal chains but also for identifying divergences in reasoning style, depth of knowledge representation, and outcome accuracy. By comparing the human and LLM outputs against the actual historical results (kept hidden during the evaluation), we assessed which system (human or LLM) achieved more accurate, logically sound, and comprehensive reasoning trajectories.

Incorporating a human baseline elevates the scientific validity of this framework. It enables an empirical evaluation of the LLMs’ reasoning capabilities beyond theoretical benchmarks or internal coherence. More importantly, it legitimizes the use of LLMs as decision-support tools by establishing whether their reasoning aligns with, approximates, or diverges from expert military judgment. Such comparative analysis is critical in determining whether LLMs can truly complement or even substitute parts of human-driven decision processes in complex, high-stakes environments.

4. Results

The evaluation phase focuses on assessing the predictive capabilities and causal reasoning performance of LLMs in military decision-making. Given the extensive nature of the experiments conducted across multiple historical battles, this section will provide a detailed analysis of the first experiment, and then an overall qualitative and quantitative analysis. The first battle serves as a representative case study to illustrate how the models as well as the domain experts (military officers) process strategic inputs, construct decision-making pathways, and predict battlefield outcomes. The remaining battles, including those covering conflicts from different historical periods and operational contexts, are fully documented and analyzed in our GitHub repository, where the complete dataset, reasoning outputs, and comparative assessments can be accessed. This selective presentation allows for a focused discussion while maintaining transparency in the broader experimental findings.

4.1. Scenario 1: Black Monday -Central Europe, 1943

4.1.1. Experimental Setup and Context

The Battle of Salerno "Black Monday" (September 13, 1943) serves as our primary case study due to its complex multi-domain operational environment and the critical decision-making challenges it presented. This amphibious assault scenario involved coordinated naval, air, and ground operations where German forces attempted to eliminate the Allied beachhead through a concentrated counterattack. The battle’s outcome hinged on rapid tactical adaptation, resource allocation under pressure, and the effective coordination of combined arms - making it an ideal test case for evaluating both human and LLM decision-making capabilities. The scenario was selected because it encompasses key elements of modern military decision-making: time-critical resource allocation, multi- domain coordination, terrain considerations, and the need to predict cascading consequences of tactical decisions. Additionally, the historical outcome provides a robust ground truth baseline against which to measure predictive accuracy and causal reasoning quality.

4.1.2. Human vs. LLM

To evaluate the accuracy of the answers made by both LLMs and human military experts, we developed a comprehensive ground truth dataset consisting of 30 historically verified facts about the Salerno battle. These facts encompassed tactical outcomes, strategic consequences, resource utilization patterns, and causal relationships that determined the battle’s ultimate resolution. Each participant’s response was systematically mapped against this ground truth using a structured annotation process. True Positives (TP) represented facts correctly identified and stated by the participants, False Positives (FP) captured assertions that contradicted historical evidence, and False Negatives (FN) identified ground truth facts that participants failed to recognize or mention. From these annotations, we calculated standard information retrieval metrics: Precision (TP/(TP+FP)), Recall (TP/(TP+FN)), and F-1 Score (harmonic mean of precision and recall).

The results (

Table 1) reveal several important patterns. GPT-o3 achieved the highest F-1 score (0.881), demonstrating high overall performance with balanced precision and recall. Notably, Claude 3.7 Extended Thinking achieved the highest precision (0.920), indicating fewer factual errors, though with slightly lower recall. Among human participants, Captain no2 performed exceptionally well (F-1: 0.877), approaching the performance of the best-performing LLM. DeepSeek R1 showed the lowest overall performance (F-1: 0.764), primarily due to lower recall, suggesting it failed to identify many relevant historical facts. All participants successfully identified the correct battle outcome (Allied victory), indicating that both LLMs and humans possessed sufficient strategic understanding to predict the macro-level result. However, the variance in detailed factual accuracy suggests significant differences in the depth and precision of their analytical processes.

4.1.3. Causal Reasoning Analysis

Beyond factual accuracy, we conducted a detailed qualitative analysis of causal reasoning capabilities across seven key aspects. This analysis evaluated how well participants understood and articulated the complex cause- and-effect relationships that determined the battle’s outcome.

Strategic Resource Analysis: human participants demonstrated exceptional practical resource management skills, reflecting their operational experience. They consistently recognized force ratios, attrition risks, and reinforcement timing constraints that would be critical in actual combat. GPT-o3 showed strong analytical capabilities, effectively identifying key resource constraints including artillery allocation and logistical considerations. Claude 3.7 Extended Thinking provided the most systematically structured analysis, explicitly considering ammunition expenditure rates and reinforcement scheduling with remarkable detail.

Multi-Order Effects Reasoning: Claude 3.7 Extended Thinking demonstrated superior performance in modeling cascading consequences, systematically tracing how tactical decisions would propagate through operational and strategic levels. For example, when analyzing the German counterattack, Claude explicitly modeled how initial tactical failures would cascade into operational withdrawal requirements, ultimately affecting strategic positioning across the Italian theater. GPT-o3 showed good awareness of cascading effects but tended to simplify complex chains. Human participants varied considerably, with senior officers (Captainno2, Colonelno1) showing good secondary effect anticipation, while others focused primarily on immediate tactical consequences.

Cross-Domain Integration: a striking finding emerged in the "Roundtable Discussion" dimension, where Claude 3.7 Extended Thinking demonstrated exceptional capability in simulating multi-perspective military planning processes. It effectively modeled debates between different military specialties (artillery, armor, air support, logistics), providing structured analysis of trade-offs and competing priorities. This capability exceeded that observed in human participants, who typically provided integrated single-perspective analyses rather than structured multi-role deliberations.

Terrain and Geographic Reasoning: human participants consistently outperformed LLMs in realistic terrain analysis, demonstrating practical understanding of line-of-sight limitations, chokepoint exploitation, and indirect fire positioning. This reflects their field experience and training in terrain appreciation. LLMs showed adequate recognition of major terrain features but occasionally missed micro-terrain dynamics that experienced officers identified as tactically critical.

4.1.4. Comparative Strengths and Limitations

The analysis reveals complementary strengths between human experts and LLMs. Human participants excelled in practical tactical execution, resource awareness, and terrain-based reasoning, reflecting their operational experience and military training. They demonstrated superior understanding of real-world constraints and feasible tactical solutions under combat conditions.

LLMs demonstrated distinct advantages in systematic analysis and structured reasoning. Claude 3.7 particularly excelled in multi-order consequence modeling and simulated staff deliberations, providing analytical depth that approached or exceeded human performance in systematic strategic assessment. GPT-o3 showed remarkable adaptability and practical understanding of tactical execution with strong counterfactual reasoning capabilities.

However, important limitations emerged. LLMs occasionally simplified terrain micro-dynamics and sometimes introduced minor factual inconsistencies. Human participants, while tactically superior, rarely engaged in the type of comprehensive multi-perspective analysis or systematic counterfactual exploration that advanced LLMs demonstrated.

Notably, in causal reasoning capabilities, LLMs demonstrated superior performance compared to human participants. Claude 3.7 Extended Thinking particularly excelled, achieving "Outstanding" ratings in multi-order effects modeling and "Exceptional" performance in simulating cross-disciplinary military debates - capabilities that surpassed the systematic reasoning demonstrated by human experts. GPT-o3 also showed "Very Strong" cause- effect modeling in tactical execution with superior counterfactual reasoning compared to the "Variable" performance observed in human participants. While humans maintained advantages in practical terrain understanding and resource management, LLMs consistently outperformed in structured analytical reasoning, systematic consequence modeling, and multi-perspective deliberation processes.

Table 2.

Qualitative Aspect Comparison of GPT-o3, DeepSeek, Claude 3.7 and Humans.

Table 2.

Qualitative Aspect Comparison of GPT-o3, DeepSeek, Claude 3.7 and Humans.

| Aspect |

GPT-o3 |

DeepSeek R1 |

Claude 3.7 Extended Thinking |

Humans (average) |

Strategic Resource

Analysis

|

Strong: identifies artillery, reserves logistical constrains |

Moderate: identifies resources but sometimes simplifies sustainment |

Strong: highly structured; explicitly considers ammo, reinforcement timing |

Very strong: excellent awareness of force ratios, attrition risks, reinforcement windows |

| Cause-Effect in Tactical Execution |

Very Strong: Models step-by-step effects with real-time adaptation |

Strong: generates good plans but may idealize execution phases |

Strong but rigid: applies structured timelines; less adaptive mid-course |

Very strong: doctrinally sound execution; anticipates immediate links realistically |

| Multi-Order Effects |

Good: identifies cascading effects but simplifies some |

Moderate: often stops at 1st-order; misses deeper cascading |

Good–Very good: models multi-order consequences, but consistency varies |

Moderate→Good: officers anticipate secondary effects; less systematic enumeration |

| Roundtable Discussion |

Good but limited: simulates perspectives but less depth |

Weak–Moderate: generally lacks multi-role discussion |

Very good: simulates cross-discipline debates and decision branches |

Weak–Moderate: integrated single-point answers; fewer explicit trade-offs |

Counterfactual

Reasoning

|

Strong: flexibly considers alternative outcomes |

Moderate: offers some alternatives; limited dynamic adaptation |

Moderate–Strong: structured alternatives but assumes stable conditions |

Variable: some provide strong counterfactuals; others explore fewer branches |

| Terrain & Geography Understanding |

Moderate: identifies ford, chokepoint, but sometimes misses micro-terrain dynamics |

Moderate: good terrain cues; occasionally oversimplifies timing/geometry |

Moderate: similar limitations; benefits from explicit terrain cues |

Strong: consistent recognition of terrain constraints, chokepoints, LOCs |

Large-Scale

Geopolitical Causality

|

Partial: tactical focus, limited strategic integration |

Partial: mostly tactical |

Partial: better than GPT-o3, still tactical-first |

Weak–Moderate: humans emphasize tactical/operational aspects over grand strategy |

4.2. Overall Analysis Across All Experiments

4.2.1. Quantitative Performance Metrics

The comprehensive evaluation across all ten historical battle scenarios provides robust statistical evidence for comparing LLM and human performance in military decision-making tasks. The aggregate results, based on mapping 300 ground truth facts across diverse operational contexts, reveal significant performance patterns.

The aggregated results demonstrate several key findings. Claude 3.7 Extended Thinking achieved the highest precision (0.920), indicating superior accuracy in factual assertions with fewer false positives. Captain no2 attained the highest F-1 score (0.893), representing the best overall balance of precision and recall among all participants. Notably, all participants achieved 100% accuracy in identifying the correct battle outcomes, suggesting that both LLMs and human experts possessed sufficient strategic understanding to predict macro-level results consistently. LLMs demonstrated strong overall performance, with Claude 3.7 (F-1:0.874) and GPT-o3 (F-1:0.865) achieving scores comparable to senior military officers. DeepSeek R1 showed the lowest performance (F-1:0.806), primarily due to reduced recall, indicating difficulty in identifying comprehensive sets of relevant historical facts. A clear performance hierarchy emerged among human participants correlating with military rank and experience. Senior officers (Colonels) achieved the highest average F-1 scores (0.879), followed by Captains (0.877), and junior officers (0.848). This pattern suggests that military experience and training significantly impact analytical performance in complex scenarios.

Table 3.

Average Performance Metrics Across All Ten Scenarios.

Table 3.

Average Performance Metrics Across All Ten Scenarios.

| Participant |

Precision |

Recall |

F-1 Score |

Identified the winner |

| LLM-GPT-o3 |

0.908 |

0.829 |

0.865 |

Yes |

| LLM-DeepSekk R1 |

0.872 |

0.753 |

0.806 |

Yes |

| LLM-Claude 3.7 Extended Thinking |

0.920 |

0.838 |

0.874 |

Yes |

| Human:SndLt no1 |

0.903 |

0.809 |

0.849 |

Yes |

| Human:SndLt no1 |

0.913 |

0.795 |

0.847 |

Yes |

| Human:Capatain no1 |

0.895 |

0.835 |

0.860 |

Yes |

| Human:Capatain no1 |

0.923 |

0.869 |

0.893 |

Yes |

| Human:Colonel no1 |

0.912 |

0.859 |

0.882 |

Yes |

| Human:Colonel no2 |

0.917 |

0.841 |

0.876 |

Yes |

Participant

Category

|

Tactical

Reasoning |

Systemic

Reasoning |

Multi-Order

Reasoning |

Counterfactual Reasoning |

|

Claude 3.7

Extended

Thinking

|

Very Strong |

Outstanding |

Outstanding |

Good |

|

| GPT-o3 |

Very Strong |

Very Strong |

Good |

Strong |

|

| DeepSeek R1 |

Strong |

Moderate |

Weak |

Weak |

|

| Human Officers |

Very Strong |

Moderate |

Moderate |

Weak to Moderate |

|

The performance differences between top-performing humans (Captain no2: 0.893) and top-performing LLMs (Claude 3.7: 0.874) represent a relatively small gap of 1.9 percentage points in practical terms, indicating that advanced LLMs are approaching human expert-level performance in factual military analysis. No formal statistical hypothesis testing (e.g., t-tests or ANOVA) was conducted, as the primary objective of this study was to provide a comparative reasoning analysis rather than inferential statistical validation.

4.2.2. Qualitative Causal Reasoning Assessment

Beyond accuracy, we conducted systematic qualitative analysis of causal reasoning capabilities across four critical dimensions: Tactical Reasoning, Systemic Reasoning, Multi-Order Reasoning, and Counterfactual Reasoning. This analysis synthesizes observations from all ten scenarios to provide a comprehensive assessment of reasoning quality (Table 4).

Tactical Reasoning: Military officers and GPT-o3 demonstrated exceptional tactical reasoning capabilities, consistently modeling realistic battlefield dynamics, terrain constraints, and doctrinal applications. Claude 3.7 showed very strong tactical reasoning but with less dynamic adaptability compared to humans. DeepSeek R1 provided competent but more rigid tactical analysis.

Systemic Reasoning: Claude 3.7 Extended Thinking consistently outperformed all other participants in systemic reasoning, demonstrating superior ability to integrate multiple domains (military, political, economic, diplomatic) into coherent analytical frameworks. This capability was particularly evident in complex scenarios involving humanitarian constraints, multi-national forces, or strategic-level implications. Military officers typically focused on military-technical aspects, rarely extending analysis to broader systemic considerations unless explicitly prompted.

Multi-Order Reasoning: Claude 3.7 Extended thinking demonstrated outstanding capability in modeling cascading consequences, consistently tracing how tactical decisions propagate through operational and strategic levels. For example, in humanitarian scenarios, Claude effectively modeled how tactical engagement rules cascade into international legal consequences, media responses, and political escalation. Military officers generally limited their analysis to first and second-order effects within the military domain.

Counterfactual Reasoning: GPT-o3 showed the strongest counterfactual reasoning, flexibly exploring alter- native scenarios and adaptive responses to changing conditions. Claude 3.7 provided structured but sometimes rigid counterfactual analysis. Military officers varied considerably, with senior officers occasionally exploring alternatives but rarely developing comprehensive counterfactual branches.

4.2.3. Time Efficiency

In addition to the accuracy and reasoning capabilities evaluated in previous sections, we also assessed the response time required by both LLMs and human participants to process and generate their decisions.

Table 5 summarizes the average time needed by each participant across the ten scenarios.

The results demonstrate that all LLMs complete the full reasoning cycle—including reading, processing, and generating structured multi-step answers—in a fraction of the time required by human officers. Claude 3.7 Extended Thinking exhibited the highest time efficiency, completing its analysis in an average of approximately 56 seconds per scenario, which is over 99% faster than the average time required by Second Lieutenants (approximately 2h and 40min hours per scenario), and still nearly 98.5% faster than experienced Colonels.

This time advantage highlights a significant operational benefit of incorporating LLMs into real-time or near-real-time decision-support environments, especially during crisis-response scenarios where rapid situation assessment may be critical. While human expertise remains superior in applied tactical realism and operational nuance, the speed at which LLMs can process structured decision frameworks enables them to act as highly efficient analytical accelerators capable of generating preliminary assessments that can assist or complement human officers during time-sensitive operations.

4.2.4. Participant-Specific Performance Patterns

Claude 3.7 Extended Thinking: emerged as the superior performer in complex analytical reasoning, particularly excelling in multi-perspective staff simulations and systematic consequence modeling. Its structured approach to causal analysis consistently outperformed military officers in developing comprehensive, multi-domain consequence chains. However, it showed less dynamic adaptability in rapidly changing tactical situations.

GPT-o3: Demonstrated the most human-like performance profile, excelling in adaptive tactical reasoning while maintaining good systemic awareness. It showed particular strength in counterfactual reasoning and dynamic scenario adaptation, often matching or exceeding human tactical realism.

Military Officers: Maintained superior performance in practical tactical execution, terrain-based reasoning, and resource management. Senior officers (Colonels and Captains) consistently outperformed junior officers and approached LLM performance in factual accuracy. However, officers rarely engaged in the systematic multi- perspective analysis that characterized advanced LLM reasoning.

DeepSeek R1: Provided consistently competent but limited analysis, typically remaining at first-order tactical reasoning without developing deeper consequence chains or multi-domain integration.

4.2.5. Findings

The overall analysis reveals complementary strengths between domain-experts (military officers) and LLMs rather than clear dominance by either group. In factual accuracy, the gap between top-performing humans and LLMs is narrow and diminishing. However, in causal reasoning capabilities, advanced LLMs (particularly Claude 3.7) demonstrate superior systematic analysis, while humans maintain advantages in practical tactical realism and terrain-based reasoning. Most significantly, in causal reasoning, LLMs demonstrated superior performance compared to domain-expert participants. Claude 3.7 consistently achieved "Outstanding" ratings in systemic and multi-order reasoning across all scenarios, capabilities that military officers rarely demonstrated systematically. This finding suggests that advanced LLMs provide significant value in military decision support through enhanced analytical depth and systematic consequence modeling, while domain expertise remains essential for tactical realism and practical implementation considerations.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study provide empirical evidence that Large Language Models (LLMs), when subjected to structured causal reasoning frameworks, demonstrate significant potential in supporting and augmenting military decision-making processes. While prior research has largely emphasized either theoretical potential or consistency concerns, our structured comparative analysis directly benchmarks LLMs against domain experts under real-world- inspired operational scenarios. This study offers a unique contribution by isolating reasoning capabilities through anonymized scenarios, thereby eliminating the possibility of latent recall contaminating the reasoning process.

The first research question investigated the ability of LLMs to accurately identify cause-and-effect relationships in complex military contexts. Our results demonstrate that advanced LLMs, particularly Claude 3.7 Extended Thinking, consistently excelled in systematic causal reasoning, outperforming both junior and senior military officers in multi-order consequence modeling. Claude 3.7 Extended Thinking achieved outstanding ratings in multi- perspective reasoning, constructing comprehensive consequence chains that incorporated not only tactical elements but also political, logistical, and legal factors. This suggests that LLMs can successfully integrate complex, cross-domain variables into their analytical processes, a capability traditionally associated with experienced commanders.

The second research question addressed whether LLMs can reliably predict second- and third-order effects in dynamic military operations. The results indicate that LLMs, and particularly Claude 3.7, demonstrate superior capacity for modeling cascading consequences. Their ability to simulate decision-making discussions and evaluate cross-disciplinary implications allowed them to foresee downstream consequences that many participants did not systematically capture. However, while LLMs excelled in systemic consequence modeling, certain tactical subtleties—especially micro-terrain dynamics and force employment nuances—were more accurately recognized by military officers with operational field experience.

The third research question explored how LLMs’ causal reasoning capabilities compare to human decision- makers across diverse historical scenarios. The aggregate quantitative analysis reveals that the performance gap between the top-performing LLMs and senior officers is narrowing. Captain no2 (F1:0.893) marginally outperformed Claude 3.7 Extended Thinking (F1:0.874), while Claude 3.7 consistently outperformed junior officers and approached senior officer levels. GPT-o3 displayed strong adaptive tactical reasoning and robust counterfactual analysis, often matching or surpassing human adaptability in rapidly evolving scenarios.

Going beyond the obtained results presented in this paper, it is important to clarify what the presented de-identification control does—and does not—for interpretation. By removing names, dates, places, and unit designations while preserving force ratios, terrain/LOS, sequencing, constraints, and objectives, anonymization prevents shortcutting via memorized episodes without erasing useful historical information and domain priors (e.g., that medium armor may neutralize artillery under specific conditions). Across all ten scenarios, the selected models, when asked, either misidentified or could not match the historical battle, indicating that the outputs were not driven by their recall capability. Moreover, transitive associations are insufficient to determine outcomes in our setting: scoring is performed against fixed per-scenario fact sets and hinges on how capabilities interact with terrain, logistics, timing, rules of engagement, and multi-order effects. Generalizing equipment into capability categories does not bias results because no model is trained here, aggregates are computed per scenario (not by category frequency), and the transformation is symmetric across sides. Reliability is supported by multi-run execution with a consolidated iteration; all human responses (Second Lieutenants, Captains, Colonels) and materials are available for transparency. Taken together, these points frame the observed human–LLM complementarity: models systematize consequences and cross-domain relations, while officers excel in terrain-aware feasibility and escalation control—supporting a human-in-the-loop posture for practical use.

In this study, the five “iterations” per scenario are independent test-time re-runs in clean sessions with the same prompts and settings. They do not involve training, fine-tuning, parameter updates, or memory carryover. We use repetitions solely to reduce response randomness and to report a representative aggregate; any single run shown is illustrative. Adding more runs mainly trades extra compute for incremental stability and coverage, without altering the fact that models remain unmodified and are evaluated purely at inference time.

Moreover, in scenarios where experienced human decision-makers are unavailable—such as in the event of battlefield casualties or command absence—the use of LLMs as interim or fallback decision agents becomes particularly valuable. While not intended to fully replace human leadership, LLMs can serve as operational placeholders, ensuring continuity of command logic and strategic coherence during critical phases. Their ability to rapidly synthesize situational data and provide time-sensitive recommendations allows for a degree of resilience in command structures that would otherwise be severely disrupted. This contingency role, in addition to their speed and analytical depth, highlights their potential as both proactive and reactive assets in high-stakes operational environments.

An important finding emerging from this study concerns the complementarity between LLMs and domain expertise. While military officers consistently outperformed LLMs in applied tactical realism, terrain appreciation, and immediate execution planning—areas reflecting the value of lived operational experience—LLMs demon- started superior performance in structured analytical reasoning, systemic integration, and long-term consequence forecasting. This complementarity suggests a clear opportunity for hybrid decision-support models that combine LLM-driven analytical depth with domain operational expertise, aligning with calls for human-AI collaboration frameworks in high-stakes domains.

The comparative evaluation supports the argument that LLMs are not mere correlation engines but can engage in genuine causal reasoning when carefully prompted within structured frameworks. The structured prompt engineering methodology employed here (

Appendix A) significantly mitigated issues previously observed in LLM unpredictability, hallucinations, and reasoning inconsistency reported in earlier studies.

Nonetheless, a limitation remains. This study focused primarily on operational-level planning scenarios; future work should explore higher-level strategic command decision-making, where political and grand-strategic factors dominate..

6. Conclusions

This study provides a rigorous, empirical evaluation of LLMs capabilities in causal reasoning within military decision-making contexts. By integrating structured anonymized scenarios, prompt-engineered multi-phase reasoning tasks, and direct comparisons with domain-expert military officers, this research offers one of the most comprehensive assessments to date of how LLMs perform under operationally realistic decision-making conditions.

The results demonstrate that advanced LLMs—particularly Claude 3.7 Extended Thinking—have achieved re- markable proficiency in systematic causal reasoning, multi-order consequence modeling, and structured analytical processing. In multi-perspective scenario deliberations, consequence chain construction, and systemic integration of cross-domain variables, Claude 3.7 consistently matched or exceeded the performance of experienced military officers. Similarly, GPT-o3 displayed highly adaptive tactical reasoning and strong counterfactual exploration, approaching expert-level reasoning in many complex battlefield scenarios.

Conversely, domain-expert military officers maintained clear superiority in applied tactical realism, terrain appreciation, force employment dynamics, and micro-level tactical adjustments—dimensions where practical experience and operational familiarity provide an irreplaceable advantage. This complementarity reinforces the conclusion that LLMs are not substitutes for commanders but powerful analytical partners capable of enhancing the breadth and depth of military planning processes.

Importantly, this study also contributes to the growing evidence that LLMs, when engaged through carefully designed structured frameworks, can surpass correlation-based pattern recognition and demonstrate genuine causal reasoning capabilities. The anonymization approach employed here successfully minimized recall bias, allowing for an authentic evaluation of reasoning ability rather than simple memorization of historical data.

The findings strongly support the development of hybrid decision-support frameworks that combine human operational judgment with LLM-driven analytical reasoning, consequence forecasting, and systematic scenario exploration. In such configurations, LLMs can provide commanders with expanded situational assessments, alternative course-of-action evaluations, and comprehensive consequence models, thereby improving overall decision quality while retaining human oversight and responsibility.

Future research should extend these findings into higher-level strategic command scenarios, integrate LLMs into live wargaming exercises, and explore adaptive model governance to ensure reliability in adversarial or information-degraded environments. Future research should also investigate representing these prompt sequences in machine-readable formats such as XML, JSON, or PMML to standardize execution, enable interoperability across LLMs, and facilitate reproducibility in reasoning workflows. While fully autonomous AI command structures remain premature and ethically problematic, LLM-augmented military decision-support systems offer immediate, practical promise for enhancing military planning, training, and operational preparedness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.D.; methodology, D.D..; software, D.D..; validation, D.D., A.S. & K.K..; formal analysis, D.D.; investigation, D.D.; resources, D.D.; data curation, D.D.; writing—original draft preparation, D.D..; writing—review and editing, A.S. & K.K.; visualization, D.D.; supervision, K.K.; project administration, K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available at the GitHub Repository reffered in the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LLMs |

Large Language Models |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| CR |

Causal Reasoning |

| MDMP |

Military decision Making Process |

| COA |

Course of Action |

| COA-GPT |

Course of Action-Generative Pre-Trained Transformer |

| CBRN |

Chemical, Biological, Radiological & Nuclear |

| CMDEF |

Causal Military Decision Evaluation Framework |

| LOC |

Line of Communication |

| GHQ |

General HeadQuarters |

Appendix A

PROMPT ENGINEERING FOR MILITARY DECISION-MAKING

PROMPT1: Initial Strategic Assessment You are a neutral military analyst tasked with evaluating a potential armed conflict between two unidentified factions. Based on the following structured data, provide a **strategic overview** highlighting strengths, vulnerabilities, and key challenges for each faction. Ensure neutrality and avoid making historical assumptions. Focus strictly on the data provided.

PROMPT2: War Initiation & Opening Moves Considering the strategic overview you provided, both factions must decide on an initial course of action. Your task: 1. Generate 3 plausible opening strategies for each side based purely on the provided data. 2. Outline expected first-order consequences of each strategy. 3. Assess potential reactions from the opposing side. 4. Identify factors that could trigger unintended escalation or diplomatic resolutions. Important: Responses should follow a cause-effect format, explicitly linking each action to its expected consequence.