Submitted:

22 October 2025

Posted:

24 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundations and Empirical Evidence Base

2.1. Foundational Theories in Innovation Adoption

2.2. Emerging Perspectives: Business Models and Financial Enablers

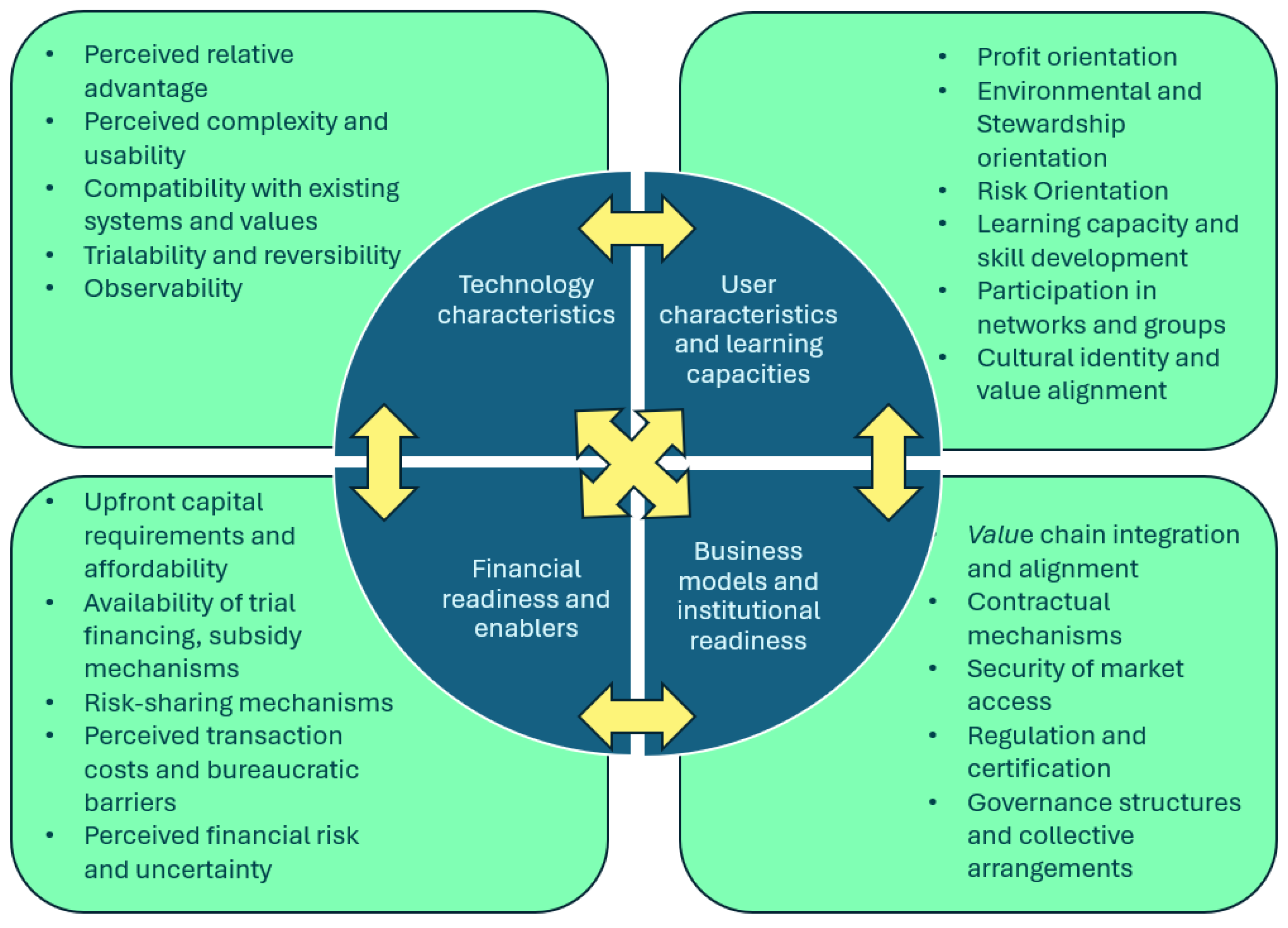

3. The Extended Integrated Adoption Model Framework

3.1. Empirical Support for Individual Quadrants: Strengths and Limitations

3.1.1. Technology Characteristics: Robust but Evolving Empirical Base

3.1.2. User Characteristics and Learning Capacities: Well-Explored but Context-Specific Nuances

3.1.3. Financial Readiness and Enablers: Increasingly Recognized but Under-Quantified

3.1.4. Business Models and Institutional Readiness: Emerging but Complex Empirical Landscape

3.2. Lack of a Systemic View of Adoption

3.3. Exploring Inter-Quadrant Relationships with the EIAMF

- How can you link variables from different quadrants to understand how they interact, compound, and cascade to create either enabling conditions or barriers?

- Can adoption practitioners use the EIAMF as a diagnosis tool to see interlinked aspects that could hinder adoption of a technology, earlier in the technology development process?

- Can adoption practitioners identify where strategic interventions can address multiple barriers simultaneously?

3.4. The EIAMF as a Structured Diagnosis Tool

3.5. Examples of EIAMF in the Primary Sector

3.5.1. Agriculture: Precision Agriculture Technologies

3.5.2. Forestry: Sustainable Forest Management Certification

3.5.3. Aquaculture: Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS)

3.5.4. Horticulture: Precision Irrigation and Fertigation Systems

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Contributions

4.2. Implications for Practitioners

4.3. Implications for Policy and Intervention Designers

5. Conclusions

6. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EIAMF | Extended Integrated Adoption Model Framework |

| DOI | Diffusion of Innovations |

| TRA | Theory of Reasoned Action |

| TAM | Technology Acceptance Model |

| CBAM | Concerns-Based Adoption Model |

| TiMO | Timber Investment Management Organizations |

| PEFC | Program for the Endorsement of Forest Certification |

| RAS | Recirculating Aquaculture Systems |

Appendix A. Proposed Variables

| Variable | Description/Example | Example Measure | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Advantage | Perceived improvement over current practice, including economic, social, or environmental benefits. | “Compared to current practices, this innovation will improve productivity/profitability/sustainability”; Return on Investment (ROI); Payback Period; Carbon footprint reduction (%); Yield increase. | Crucial for initial interest and sustained adoption. Can be quantitative (e.g., yield increase) or qualitative (e.g., improved quality of life). Measured in terms that matter to the specific users. |

| Compatibility | Perceived consistency with existing values, needs, prior experiences, infrastructure, and operational practices. | “This innovation fits well with my existing equipment and values/farm management system”; Degree of change required in current practices (qualitative assessment); Integration cost with existing systems. | High compatibility reduces perceived disruption and facilitates easier integration. Innovations incompatible with existing values or practices will not be adopted as rapidly. |

| Complexity | Perceived difficulty of understanding, learning, and using the innovation. | “This innovation is difficult to understand and use”; Training hours required; Number of steps in implementation process; Perceived ease of use. | High complexity can be a significant barrier, especially for resource-constrained adopters. |

| Trialability | Ease of experimenting with the innovation on a limited basis before full adoption. | Percentage of users able to test innovation at small scale; Availability of pilot programs or demonstration sites; Cost of trial. | Reduces perceived risk and allows adopters to gain direct experience. |

| Observability | Visibility of the results and benefits of the innovation to others. | “I can easily see the results of this innovation on other farms/forests/aquaculture sites”; Number of demonstration farms; Peer-to-peer learning opportunities. | Facilitates social learning and reduces uncertainty for potential adopters. |

| Reversibility | Ease of switching back to prior practices if the innovation proves unsatisfactory. | “I could easily revert to prior practices if needed”; Cost of dis-adoption; Time required to revert. | Low reversibility increases perceived risk and can deter adoption. |

| Cost (Upfront & Ongoing) | Initial investment costs, operational costs, maintenance costs, and potential hidden costs. | Upfront and ongoing financial cost; Total Cost of Ownership (TCO); Cost per unit of output. | A critical financial barrier, especially in capital-intensive primary sectors. |

| Security | Concerns over data privacy, cybersecurity risks, and physical security implications of the innovation. | “Using this innovation exposes me to data/security risks”; Number of reported security breaches (if applicable); Compliance with data protection regulations. | Increasingly important for digital technologies and data-driven innovations. |

| Uncertainty/Risk (Technical) | Perceived operational risk, reliability, and consistency of the innovation’s performance. | “I am uncertain about the consistent performance of this innovation”; Variance in performance metrics; Frequency of technical failures. | High uncertainty can deter risk-averse adopters. |

| Technical Performance | Objective measures of the innovation’s efficiency, reliability, quality of results, and output. | Objective measures of performance reliability (e.g., uptime, yield increase, disease reduction); Error rate; Throughput. | Directly impacts the perceived benefits and effectiveness of the innovation. |

| Environmental and Social Impact | Perceived positive or negative impacts on the environment and community. | “This innovation has positive impacts on the environment/community”; Reduction in greenhouse gas emissions (%); Water usage reduction (%); Job creation/displacement. | Growing importance due to sustainability concerns and corporate social responsibility. |

| Technical Fit/Interoperability | Compatibility and seamless integration with existing technical systems, equipment, and software. | “This innovation integrates seamlessly with my current systems”; Number of interfaces required; Compatibility standards met. | Essential for avoiding system fragmentation and ensuring smooth operations. |

| Adaptability/Scalability | Ease with which the innovation can be modified, expanded, or adapted to different scales of operation or changing conditions. | Ease of customization (qualitative); Scalability potential (e.g., small farm to large enterprise); Modularity of components. | Important for long-term relevance and broader applicability across diverse primary sector operations. |

| Variable | Description/Example | Example Measure | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Profit Orientation | The degree to which an adopter prioritizes financial gains and economic efficiency in decision-making. | Focus on financial outcomes; Investment in profit-maximizing technologies; Use of financial planning tools. | Highly influential in capital-intensive primary sectors. |

| Environmental Orientation | The degree to which an adopter prioritizes environmental sustainability and ecological stewardship. | Focus on sustainability outcomes; Adoption of eco-friendly practices; Certification in environmental standards. | Growing importance due to climate change and consumer demand for sustainable products. |

| Risk Aversion | Tendency to avoid or minimize exposure to uncertainty and potential losses. | “I prefer practices with guaranteed outcomes over potentially higher but uncertain returns”; Insurance uptake; Diversification of activities. | High risk aversion can deter adoption of novel, unproven innovations. |

| Openness to Change | General receptiveness to new ideas, practices, and technologies. | “I am generally open to trying new practices and technologies”; History of early adoption; Participation in innovation workshops. | A key psychological trait influencing willingness to innovate. |

| Prior Knowledge/Experience | Familiarity with similar innovations, technologies, or management practices. | Years of experience with related technologies; Scores on knowledge tests; Participation in training programs. | Reduces perceived complexity and uncertainty, facilitating adoption. |

| Learning Orientation | Willingness and capacity to invest time and effort in acquiring new knowledge and skills. | “I am willing to invest in learning new skills for this innovation”; Participation in extension services; Engagement in peer learning groups. | Crucial for adapting to complex innovations and continuous improvement. |

| Cultural Identity/Value Alignment | The extent to which the innovation aligns with the adopter’s cultural values, beliefs, and social norms. | Alignment with cultural practices (e.g., Māori governance, traditional practices); Perceived impact on community values. | Particularly relevant in diverse cultural contexts within the primary sector. |

| Social Identity/Peer Group Influence | The influence of belonging to specific social or professional groups on adoption decisions. | Alignment with identity groups (e.g., industry peer groups, farmer associations); Perceived adoption by opinion leaders. | Strong influence of social networks and demonstration effects. |

| Peer Network Embeddedness | The degree of participation and integration within informal and formal peer networks. | Number of active memberships in farmer groups; Frequency of interaction with peers; Role as an opinion leader. | Facilitates knowledge exchange, social learning, and trust building. |

| Social Norms | Perceived expectations and behaviors of important others (e.g., family, neighbors, industry leaders). | “Most farmers in my area are adopting this innovation”; Perceived social pressure to adopt. | Can significantly drive or hinder adoption through conformity. |

| Subjective Norms | The perceived social pressure to perform or not perform a behaviors, influenced by specific individuals or groups. | Influence from key opinion leaders; Recommendations from trusted advisors. | Similar to social norms but focuses on specific influential figures. |

| Attitudes toward Innovation | General positive or negative predisposition towards innovations in general or a specific innovation. | “I have a positive attitude towards new technologies in farming”; Affective (emotional) and cognitive (belief) components. | Directly impacts adoption intention and behaviors. |

| Trust in Technology/Providers | Degree of trust in the innovation’s reliability, the provider’s credibility, and the information sources. | “I trust the information provided about this innovation”; Reputation of technology provider; Perceived transparency. | Reduces perceived risk and uncertainty. |

| Self-Efficacy | Perceived ability to successfully perform the actions required to use the innovation. | “I am confident in my ability to use this innovation successfully”; Prior success with similar tasks; Access to training and support. | A strong predictor of adoption and sustained use. |

| Access to Information | The availability and accessibility of relevant, timely, and trustworthy information about the innovation. | Number of information sources accessed; Perceived quality of information; Participation in extension programs. | Crucial for reducing uncertainty and building knowledge. |

| Decision-making power | Accountability level for the decision | “I am accountable for decisions made within my family/ company” | Perceived behavioral control and perceived accountability |

| Variable | Description/Example | Example Measure | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upfront Capital Requirements | The amount of initial investment needed to acquire and implement the innovation. | Initial investment cost; Percentage of total farm assets required. | A major barrier, especially for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the primary sector. |

| Availability of Subsidies/Incentives | Presence and accessibility of financial supports from government, industry, or other organizations. | Amount of grant/subsidy available; Eligibility criteria met; Ease of application process. | Can significantly de-risk and incentivize adoption. |

| Trial Financing/Pilot Funding | Availability of specific financial support for testing or piloting the innovation on a limited scale. | Availability of dedicated trial funds; Success rate of pilot projects. | Reduces the financial risk associated with initial experimentation. |

| Cost Structure Fit | Whether the innovation’s cost structure aligns with the adopter’s existing cash flow, revenue cycles, and financial planning. | Alignment with seasonal cash flow (qualitative); Impact on working capital; Need for external financing. | Mismatch can lead to liquidity issues, even if the innovation is profitable long-term. |

| Revenue Model Fit/Value Capture | How the innovation generates revenue or cost savings for the adopter, and how well this aligns with their existing business model. | New revenue streams generated; Cost savings achieved; Impact on existing revenue streams. | Ensures the innovation is not just technically viable but also economically sustainable. |

| Risk Sharing Mechanisms | Availability of mechanisms to mitigate financial risks associated with the innovation (e.g., insurance, guarantees, joint ventures). | Availability of crop insurance, price insurance; Participation in risk-sharing cooperatives; Public-private partnerships (PPPs). | Crucial for reducing perceived financial risk, especially for novel or climate-sensitive innovations. |

| Perceived Financial Risk | The adopter’s subjective assessment of the financial uncertainty and potential losses associated with the innovation. | “I am uncertain about the financial returns of this innovation”; Perceived variability of returns; Likelihood of financial loss. | Influenced by objective risk but also by individual risk aversion. |

| Transaction Costs (Financial) | Costs associated with accessing finance, such as application fees, legal costs, and time spent on administrative processes. | Time spent on loan applications; Fees for financial services; Complexity of financial agreements. | Can be a hidden barrier, especially for small-scale producers. |

| Affordability/Budget Constraints | The perceived ability of the adopter to bear the financial burden of the innovation within their current budget. | Perceived affordability; Debt-to-equity ratio; Available discretionary income. | Even if profitable, an innovation might be unaffordable if capital is constrained. |

| Payback Time/Return on Investment (ROI) | The expected period to recoup the initial investment, or the financial return generated relative to the investment. | Payback period (years); ROI (%); Net Present Value (NPV); Internal Rate of Return (IRR). | Key metrics for evaluating the financial attractiveness and viability of an investment. |

| Access to Credit/Capital | The availability of and ability to secure loans, equity, or other forms of capital for innovation adoption. | Loan approval rates; Interest rates; Collateral requirements; Relationship with financial institutions. | Direct access to funding is fundamental for capital-intensive innovations. |

| Government Financial Support | Direct financial assistance or tax incentives provided by government bodies to encourage specific innovation adoption. | Tax credits for innovation; Subsidies for sustainable practices; Grants for R&D. | Policy instruments that directly influence the financial landscape for adopters. |

| Variable | Description/Example | Example Measure | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Value Proposition Strength | The clarity, attractiveness, and distinctiveness of the value offered by the innovation to various stakeholders in the value chain. | Perceived value by customers/partners; Market demand for the innovation’s output; Differentiation from alternatives. | A strong value proposition is essential for market acceptance and business model viability. |

| Portfolio alignment | The fit with current strategic direction and portfolio | Relatedness to current objectives and product stable | A strong portfolio alignment reduces risk and effort required to reposition in order to adopt |

| Channels/Distribution | How effectively the innovation is promoted, delivered, and made available to target adopters and markets. | Number and effectiveness of distribution channels; Accessibility of the innovation; Marketing reach. | Efficient channels reduce friction in adoption and market penetration. |

| Customer Relationships | The nature and quality of interactions between the innovation provider/adopter and their customers/stakeholders. | Level of customer support and engagement; Customer satisfaction scores; Repeat business. | Strong relationships build trust and facilitate feedback for innovation refinement. |

| Key Partnerships | The presence and effectiveness of collaborations with aligned partners across the value chain (e.g., suppliers, processors, retailers, research institutions). | Number and quality of strategic partnerships; Joint ventures; Collaborative agreements. | Crucial for sharing resources, knowledge, and risks in complex value chains. |

| Governance Structures | The formal and informal rules, decision-making processes, and power dynamics within organizations and networks that influence innovation adoption. | Role of cooperatives, industry associations, iwi trusts, catchment groups; Centralized vs. decentralized decision-making. | Can facilitate or hinder collective action and resource allocation for innovation. |

| Contractual Security/Legal Framework | The existence of clear, enforceable contracts and a supportive legal framework that secures market access, intellectual property, and investment. | Presence of formal contracts; Legal protection for new practices; Regulatory clarity. | Reduces uncertainty and encourages investment in new business models. |

| Certification & Standards Barriers | Requirements, certifications, or standards that may restrict market access or increase the cost/complexity of adoption. | Number of certifications required; Cost of compliance; Time to achieve certification. | Can act as significant non-tariff barriers or enablers depending on alignment. |

| Actor Network Dynamism/Flexibility | How open, flexible, and adaptive the network of actors (e.g., farmers, researchers, policymakers) is to new ideas and collaborations. | Degree of network openness; Speed of information flow; Adaptability to change. | Dynamic networks foster innovation and rapid diffusion. |

| Institutional Alignment/Policy Support | Whether public agencies, policies, and regulatory frameworks actively support and enable the adoption of the innovation. | Presence of supportive policies (e.g., R&D funding, extension services, land use regulations); Policy coherence; Regulatory burden. | Government and institutional support can significantly de-risk and accelerate adoption. |

| Trust in Partners & Institutions | The level of trust among actors within the value chain and in the governing institutions. | Perceived trustworthiness of suppliers, buyers, government agencies; Reputation of industry bodies. | High trust reduces transaction costs and facilitates collaboration. |

| Market Infrastructure Readiness | The availability and quality of physical and digital infrastructure necessary to support the innovation (e.g., broadband, processing facilities, transport). | Access to high-speed internet; Availability of specialized processing plants; Logistics efficiency. | Essential for scaling up and integrating innovations into the broader economy. |

| Social License to Operate | The ongoing acceptance of an innovation or project by local communities and stakeholders. | Community acceptance (qualitative); Public perception surveys; Absence of social opposition. | Crucial for long-term sustainability and avoiding social conflicts. |

References

- Pretty, J.; Sutherland, W.J.; Ashby, J.; Auburn, J.; Baulcombe, D.; Bell, M.; Bentley, J.; Bickersteth, S.; Brown, K.; Burke, J.; et al. The Top 100 Questions of Importance to the Future of Global Agriculture. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2010, 8, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doss, C.R. Analyzing Technology Adoption Using Microstudies: Limitations, Challenges, and Opportunities for Improvement. Agric. Econ. 2006, 34, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes de Oca Munguia, O.; Llewellyn, R. The Adopters versus the Technology: Which Matters More When Predicting or Explaining Adoption? Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2020, 42, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wauters, E.; Mathijs, E. The Adoption of Farm Level Soil Conservation Practices in Developed Countries: A Meta-Analytic Review. Int. J. Agric. Resour. Gov. Ecol. 2014, 10, 78–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes de Oca Munguia, O.; Pannell, D.J.; Llewellyn, R. Understanding the Adoption of Innovations in Agriculture: A Review of Selected Conceptual Models. Agronomy 2021, 11, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oorschot, J.A.W.H.; Hofman, E.; Halman, J.I.M. A Bibliometric Review of the Innovation Adoption Literature. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 134, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations.; The Free Press: New York, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Sahin, I. Detailed Review of Rogers DOI and Educational Technology - Related Studied Based on Rogers Theory. Turkish Online J. Educ. Technol. 2006, 5, 1303–6521. [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor, K.K.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Williams, M.D. Rogers’ Innovation Adoption Attributes: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of Existing Research. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2014, 31, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornatzky, L.; Klein, K. Innovation Characteristics and Innovation Adoption-Implementation: A Meta-Analysis of Findings. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 1982, 29, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, T.; McKemey, K.; Garforth, C.; Huggins, R.; Yates, C.M.; Cook, R.J.; Tranter, R.B.; Park, J.R.; Dorward, P.T. Theory of Reasoned Action and Its Integration with Economic Modelling in Linking Farmers’ Attitudes and Adoption Behavior - An Illustration from the Analysis of the Uptake of Livestock Technologies in the South West of England. In International Farm Management Congress 2003; 2003; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F. A Theoretical Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four Longitudinal Field Studies. Manage. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, G.E.; Loucks, S.F.; Rutherford, W.L.; Newlove, B.W. Levels of Use of the Innovation: A Framework for Analyzing Innovation Adoption. J. Teach. Educ. 1975, 26, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, A.; Gardner, J. Aligning Technology and Institutional Readiness: The Adoption of Innovation. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2019, 31, 1229–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. Business Model Innovation: Opportunities and Barriers. Long Range Plann. 2010, 43, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baden-Fuller, C.; Haefliger, S. Business Models and Technological Innovation. Long Range Plann. 2013, 46, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, T.B.; Blok, V.; Poldner, K. Business Models for Maximising the Diffusion of Technological Innovations for Climate-Smart Agriculture. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2017, 20, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajol, K.; Singh, R.; Paul, J. Adoption of Digital Financial Transactions: A Review of Literature and Future Research Agenda. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 184, 121991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, F.; Gale, D. Innovations in Financial Services, Relationships, and Risk Sharing. Manage. Sci. 1999, 45, 1239–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.; Giné, X.; Vickery, J. How Does Risk Management Influence Production Decisions? Evidence from a Field Experiment. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2017, 30, 1935–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Key, N.; Roberts, M.J. Government Payments and Farm Business Survival. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2006, 88, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birner, R.; Davis, K.; Pender, J.; Nkonya, E.; Anandajayasekeram, P.; Ekboir, J.; Mbabu, A.; Spielman, D.J.; Horna, D.; Benin, S.; Cohen, M. From Best Practice to Best Fit: A Framework for Designing and Analyzing Pluralistic Agricultural Advisory Services Worldwide. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2009, 15, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokopy, L.S.; Floress, K.; Arbuckle, J.G.; Church, S.P.; Eanes, F.R.; Gao, Y.; Gramig, B.M.; Ranjan, P.; Singh, A.S. Adoption of Agricultural Conservation Practices in the United States: Evidence from 35 Years of Quantitative Literature. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2019, 74, 520–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oturakci, M.; Yuregir, O.H. New Approach to Rogers’ Innovation Characteristics and Comparative Implementation Study. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. - JET-M 2018, 47, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feder, G.; Just, R.E.; Zilberman, D. Adoption of Agricultural Innovations in Developing Countries: A Survey. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 1985, 33, 255–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feder, G.; Umali, D.L. The Adoption of Agricultural Innovations. A Review; 1993; Vol. 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountas, S.; Wulfsohn, D.; Blackmore, B.S.; Jacobsen, H.L.; Pedersen, S.M. A Model of Decision-Making and Information Flows for Information-Intensive Agriculture. Agric. Syst. 2006, 87, 192–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesina, A.; Baidu-Forson, J. Farmers’ Perceptions and Adoption of New Agricultural Technology. Agircultural Econ. 1995, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, M.; Pannell, D.J.; Abadi Ghadim, A. The Economics of Risk, Uncertainty and Learning in the Adoption of New Agricultural Technologies: Where Are We on the Learning Curve? Agric. Syst. 2003, 75, (2–3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgart-Getz, A.; Prokopy, L.S.; Floress, K. Why Farmers Adopt Best Management Practice in the United States: A Meta-Analysis of the Adoption Literature. J. Environ. Manage. 2012, 96, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.; Jones, L. Innovations - Agricultural Value Chain Finance; 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haftor, D.M.; Climent Costa, R. Five Dimensions of Business Model Innovation: A Multi-Case Exploration of Industrial Incumbent Firm’s Business Model Transformations. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 154, 113352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, C.B.; Bachke, M.E.; Bellemare, M.F.; Michelson, H.C.; Narayanan, S.; Walker, T.F. Smallholder Participation in Contract Farming: Comparative Evidence from Five Countries. World Dev. 2012, 40, 715–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuehne, G.; Llewellyn, R.; Pannell, D.J.; Wilkinson, R.; Dolling, P.; Ouzman, J.; Ewing, M. Predicting Farmer Uptake of New Agricultural Practices: A Tool for Research, Extension and Policy. Agric. Syst. 2017, 156, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M.; LeBel, L.; Lindroos, O. The Effect of Customer-Contractor Alignment in Forest Harvesting Services on Contractor Profitability and the Risk for Relationship Breakdown. Forests 2017, 8, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jylhä, P.; Rikkonen, P.; Hamunen, K. Size Matters – an Analysis of Business Models and the Financial Performance of Finnish Wood-Harvesting Companies. Silva Fenn. 2020, 54, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisdom, J.P.; Chor, K.H.B.; Hoagwood, K.E.; Horwitz, S.M. Innovation Adoption: A Review of Theories and Constructs. Adm. Policy Ment. Heal. Ment. Heal. Serv. Res. 2014, 41, 480–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes de Oca Munguia, O.; Pannell, D.J.; Llewellyn, R.; Stahlmann-brown, P. Adoption Pathway Analysis: Representing the Dynamics and Diversity of Adoption for Agricultural Practices. Agric. Syst. 2021, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, J.C.; Lambert, D.M.; Roberts, R.K.; Larson, J.A.; English, B.; Larkin, S.L.; Martin, S.W.; Marra, M.C.; Paxton; Kenneth, W.; Reeves, J.M. Adoption and Abandonment of Precision Soil Sampling in Cotton Production. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2008, 33, 428–448. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, E.; Nybakk, E.; Panwar, R. Innovation Insights from North American Forest Sector Research: A Literature Review. Forests 2014, 5, 1341–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, E.; Korhonen, S.; Rametsteiner, E.; Shook, S. Current State-of-Knowledge: Innovation Research in the Global Forest Sector. J. For. Prod. Bus. Res. 2006, 3, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kronholm, T.; Larsson, I.; Erlandsson, E. Characterization of Forestry Contractors’ Business Models and Profitability in Northern Sweden. Scand. J. For. Res. 2021, 36, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štěrbová, M.; Kovalčík, M. Typology of Contractors for Forestry Services: Insights from Slovakia. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, N.; Ince, P.; Skog, K.; Plantinga, A. Understanding the Adoption of New Technology in the Forest Products Industry. Explor. Black Box 2009, 40, 232–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, R.J.; Liu, P.; Shao, Y. Financial Innovation and Aggregate Risk Sharing. Theor. Econ. Lett. 2018, 08, 2182–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enstrom, J. Qualitative Aspects of Communication and Relations between the Actors in a Supply Chain for Forest Fuel. In IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management; 2020; Vol. 2020-Dec, pp 842–846. [CrossRef]

- Benjaminsson, F.; Kronholm, T.; Erlandsson, E. A Framework for Characterizing Business Models Applied by Forestry Service Contractors. Scand. J. For. Res. 2019, 34, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downes, L.; Nunes, P. Finding Your Company’s Second Act: How to Survive the Success. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2018, No. February, 98–108. [Google Scholar]

- Khanna, M. Sequential Adoption of Site-Specific Technologies and Its Implications for Nitrogen Productivity: A Double Selectivity Model. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2001, 83, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, A.; Lindström, M.; Heuts, L.; Hylander, N.; Lind, E.; Nielsen, C. Innovation Diffusion of New Wood-Based Materials - Reducing the “Time to Market. ” Scand. J. For. Res. 2014, 29, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isgin, T.; Bilgic, A.; Forster, D.L.; Batte, M.T. Using Count Data Models to Determine the Factors Affecting Farmers’ Quantity Decisions of Precision Farming Technology Adoption. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2008, 62, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paxton, K.W.; Mishra, A.K.; Chintawar, S.; Roberts, R.K.; Larson, J.A.; English, B.C.; Lambert, D.M.; Marra, M.C.; Larkin, S.L.; Reeves, J.M.; Martin, S.W. Intensity of Precision Agriculture Technology Adoption by Cotton Producers. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2011, 40, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batte, M.T.; Arnholt, M.W. Precision Farming Adoption and Use in Ohio: Case Studies of Six Leading-Edge Adopters. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2003, 38, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castle, M.H.; Lubben, B.D.; Luck, J.D. Factors Influencing the Adoption of Precision Agriculture Technologies by Nebraska Producers. Dep. Agric. Econ. Present. Work. Pap. Gray Lit. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bull, L.; Ferguson, I. Factors Influencing the Success of Wood Product Innovations in Australia and New Zealand. For. Policy Econ. 2006, 8, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hintz, K.S.; Pretzsch, J. Co-Creation of Business Models for Smallholder Forest Farmers’ Organizations: Lessons Learned from Rural Ethiopia and Tanzania. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2023, 94, 921–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toppinen, A.; Autio, M.; Sauru, M.; Berghäll, S. Sustainability-Driven New Business Models in Wood Construction towards 2030. World Sustain. Ser. 2018, 499–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, J.L. The Promotion of ‘Innovation’ in Forestry: A Role for Government or Others? J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2009, 6, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triplat, M.; Krajnc, N. A System for Quality Assessment of Forestry Contractors. Croat. J. For. Eng. 2021, 42, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, C.I.M.; Eding, E.H.; Verdegem, M.C.J.; Heinsbroek, L.T.N.; Schneider, O.; Blancheton, J.P.; d’Orbcastel, E.R.; Verreth, J.A.J. New Developments in Recirculating Aquaculture Systems in Europe: A Perspective on Environmental Sustainability. Aquac. Eng. 2010, 43, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, F.; Bostock, J.; Fletcher, D. Review of Recirculation Aquaculture System Technologies and Their Commercial Application; 2014; Vol. 44, Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1893/21109.

- Evans, R.G.; LaRue, J.; Stone, K.C.; King, B.A. Adoption of Site-Specific Variable Rate Sprinkler Irrigation Systems. Irrig. Sci. 2013, 31, 871–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.L.; Miller, W.L. The Adoption Process and Environmental Innovations: A Case Study of the Government Project. Rural Sociol. 1978, 43, 634–648. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, B.; Tanner, S.; Thornsbury, S. Behavioral Factors in the Adoption and Diffusion of USDA Innovations; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Widodo, S.; Asmorowati, S.; Dewi, A.; Wijaya, C.N.; Husniati, C. Communicating the Move towards Social Entrepreneurship: The Role of Key Partners for Women Empowerment Initiative in East Java. Masyarakat, Kebud. dan Polit. 2022, 35, 478–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byerlee, D.; Spielman, D.J.; Alemu, D.; Gautam, M. Policies to Promote Cereal Intensification in Ethiopia: A Review of Evidence and Experience. IFPRI Discuss. Pap. 2007. No. June, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Xiao, H.; Wang, Y.; Shareef, M.A.; Akram, M.S.; Goraya, M.A.S. An Integration of Antecedents and Outcomes of Business Model Innovation: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 131, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Technology Example | Technology Characteristics | User Characteristics | Financial Readiness | Business Models & Institutional Readiness | Potential mitigation solution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Agriculture: Precision Agriculture Technologies Sources: [27,51,52,53,54] |

• Relative advantage: Clear benefits • Complexity: High complexity creates adoption challenges |

• Education: Strongly correlated with adoption • Technical orientation: Critical factor • Networks: Participation increases adoption • Experience: Prior computer system experience beneficial • Risk tolerance: Risk aversion creates barriers |

• Barriers: Primary constraint: initial capital requirements • Solutions: Equipment leasing, pay-per-use models, government cost-share programs • Innovation: Service-based business models |

• Support systems: Strong dealer networks providing technical support • Partnerships: Industry partnerships integrating data • Institutional factors: Data privacy regulations, equipment standards, extension service |

Financial barriers could be addressed through innovative financing mechanisms leveraging dealer networks to create cooperative equipment leasing arrangements and subscription-based service packages that convert capital expenditures into manageable operational expenses. Extension services could develop simplified decision support tools reducing perceived complexity. Business model innovation could include data-sharing cooperatives pooling precision agriculture information for robust management recommendations, and supply chain incentives rewarding efficient resource use. |

|

Forestry: Sustainable Forest Management Certification Sources: [36,40,55,56,57,58,59] |

• Relative advantage: Moderate/neutral • Complexity: Moderate complexity with limited trialability |

• Environmental orientation: Strong environmental values increase adoption • Networks: Professional sustainability-focused networks important • Learning orientation: Critical for understanding complex standards |

• Costs: Potential significant management changes affecting operational costs • Benefits: Certified products can command price premiums • Solutions: Group certification schemes enable |

• Market demand: Strong demand from environmentally-conscious consumers and corporate buyers • Institutional support: Government agencies, environmental organisations, industry associations provide technical assistance • Trust: Essential relationships between forest owners and certification bodies |

Government agencies could facilitate multi-stakeholder partnerships that align shared sustainability values across industry, consumer, and brokerage sectors through integrated policy instruments including payment for ecosystem services, carbon credit schemes, and preferential procurement policies. Financial barriers could be addressed through expanding group certification schemes that enable cost-sharing among smaller forest owners, combined with green financing mechanisms offering preferential loan rates for certified operations. Institutional support through cooperative governance structures could facilitate collective action, knowledge exchange, and shared technical assistance, reducing individual adoption barriers. |

|

Aquacultre: Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS) Sources: [14,19,60,61,63] |

• Relative advantage: Substantial environmental advantages • Complexity: High - requires sophisticated monitoring and control systems • Observability: Excellent through demonstration facilities • Trialability: Limited |

• Technical competence: High level required • Learning orientation: Must understand complex biological and engineering systems • Risk tolerance: Essential • Networks: Peer networks important |

• Barriers: Very significant capital requirements and higher ongoing operating costs • Solutions: Public-private partnerships, equipment leasing, outcome-based financing • Innovation: Modular systems and shared infrastructure models improve accessibility |

• Partnerships: Strong partnerships needed with equipment suppliers, technical service providers • Institutional support: Research programs, regulatory frameworks recognising environmental benefits, extension services • Trust: Essential relationships among value chain participants |

Given the expense and risk of RAS systems, innovative leasing arrangements via public -private partnerships are required. The ability to overcome complexity and high capital cost for adoption introduces the potential for new business models and financing arrangements whereby “mini adoption” might occur through partial trialling of the system. This could be through partnership models allowing a wider range of business partners across the value chain able to invest in the technology, and financial arrangements that provide greater flexibility in securing a portion of an asset at a time. |

|

Horticulture: Precision irrigation and Fertigation Systems Sources: [21,27,30,33,62] |

• Relative advantage: substantial relative advantage through improved water use efficiency • Complexity: high complexity, requiring integration of multiple components • Compatibility: substantial changes required to existing irrigation infrastructure and management practices |

• Environmental orientation: Strong environmental values increase adoption • Risk tolerance: while the technology reduces production risks associated with water stress and nutrient deficiencies, it introduces new risks related to system failures and dependence on sophisticated equipment • Technical competence: High level required • Learning orientation: continuous improvement in sensor interpretation and data-driven decision making |

• Barriers: Upfront capital requirements are substantial, with ongoing costs for sensor maintenance, software subscriptions, and technical support • Solutions: innovative financing mechanisms including equipment leasing, pay-per-use models, and government cost-share programs have emerged to address barriers • Research gap: Producers generally perceive a lack of sustainable, consistent economic advantages from precision agriculture technologies |

• Value proposition: depends heavily on whether water scarcity, regulatory requirements, or market demands create compelling drivers beyond pure economic returns • Market infrastructure: coordinated equipment dealers, irrigation consultants, and technical service providers significantly facilitates adoption • Partnerships: key partnerships between growers, equipment suppliers, and water management agencies are critical |

Financial barriers could be addressed through innovative service-based business models where specialised providers install, own, and manage systems, charging growers based on water savings achieved rather than requiring upfront capital investment. Public-private partnerships could combine government cost-share programs with equipment supplier financing. Institutional support should prioritise development of regional irrigation management services providing comprehensive technical assistance. Policy coherence ensuring that water pricing, environmental regulations, and agricultural support programs align to incentivise water conservation investments is essential. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).