Submitted:

23 October 2025

Posted:

23 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

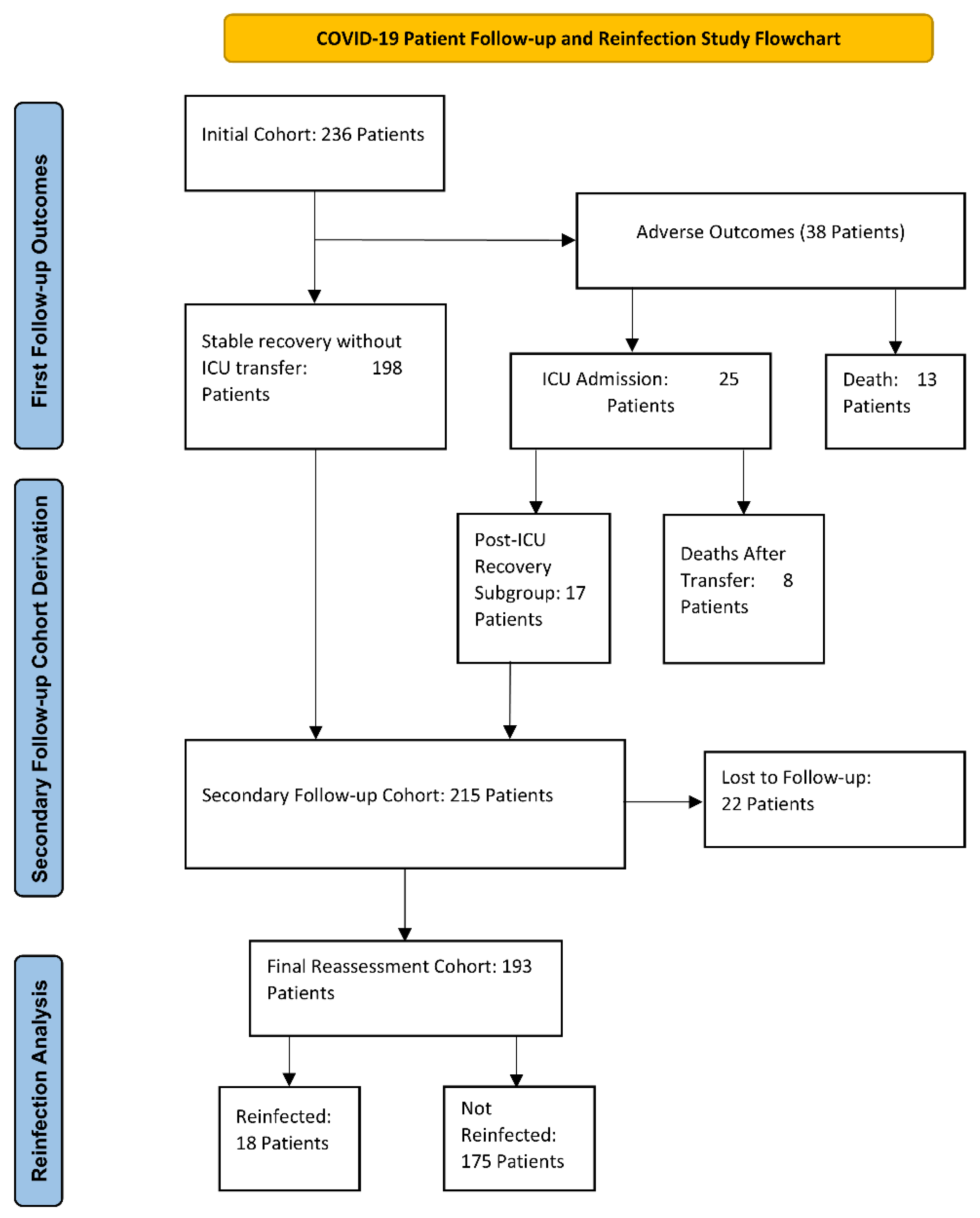

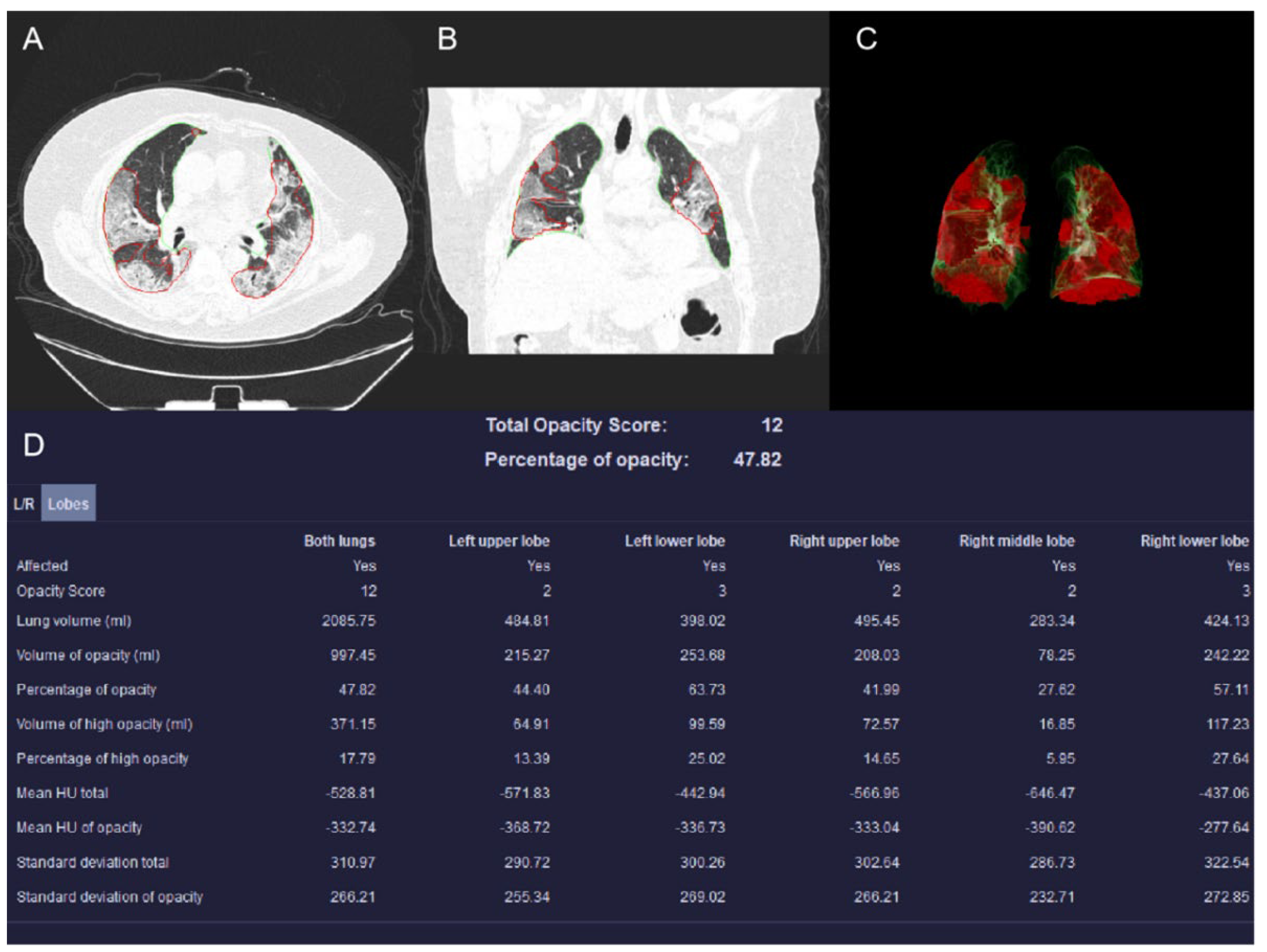

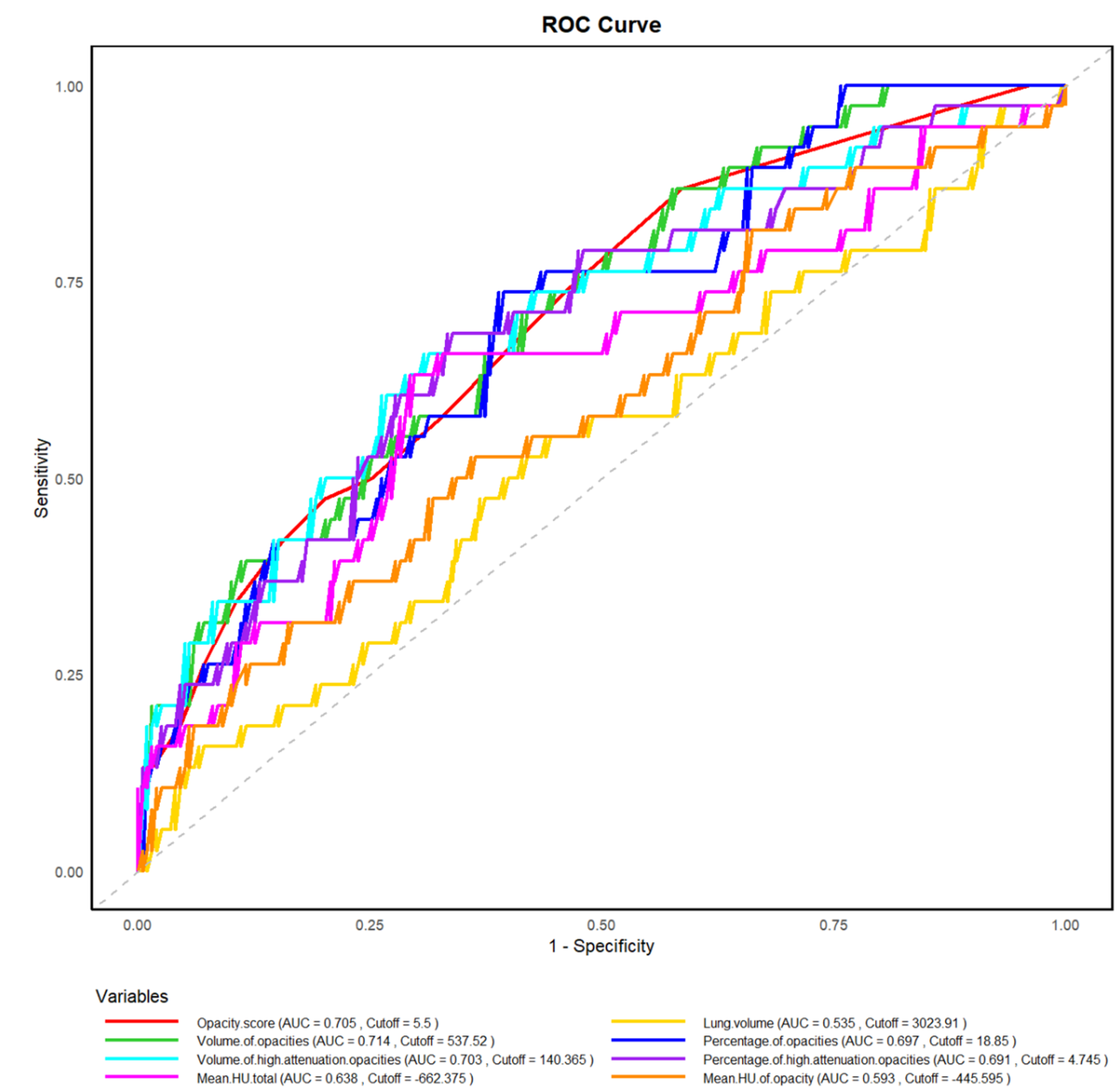

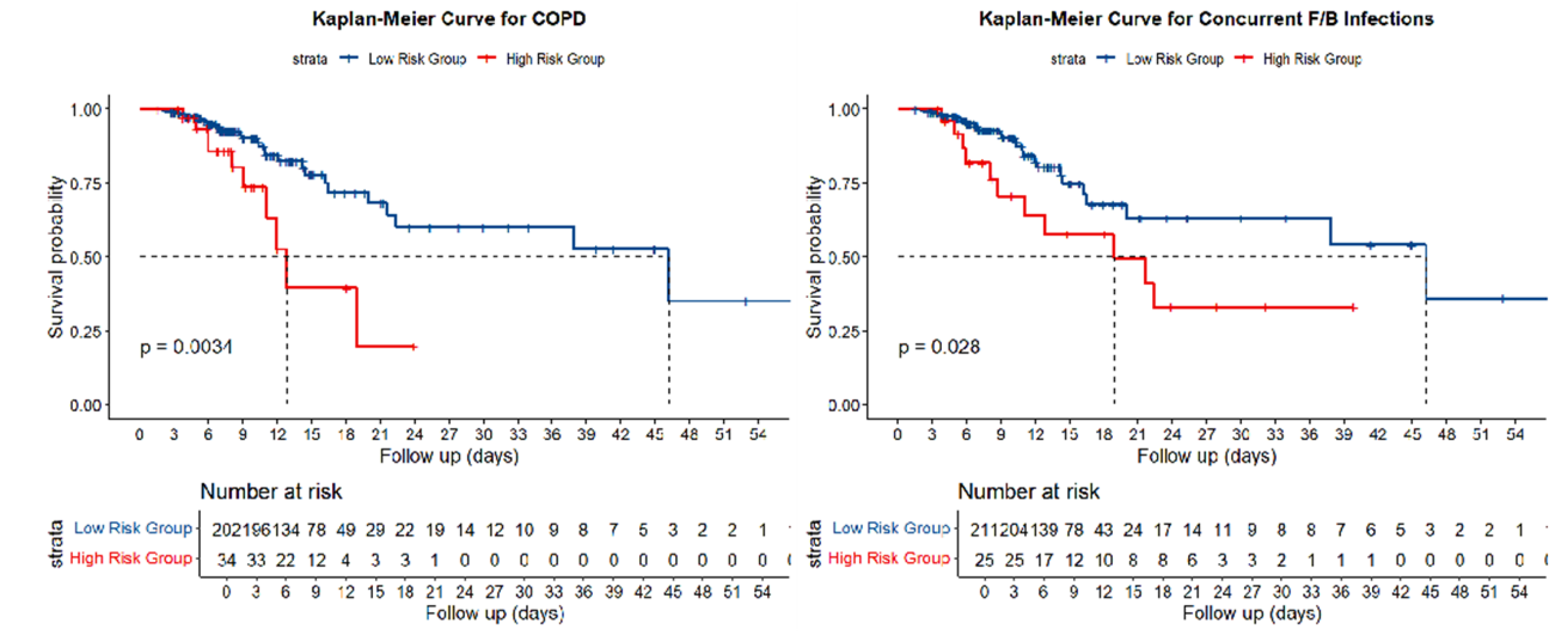

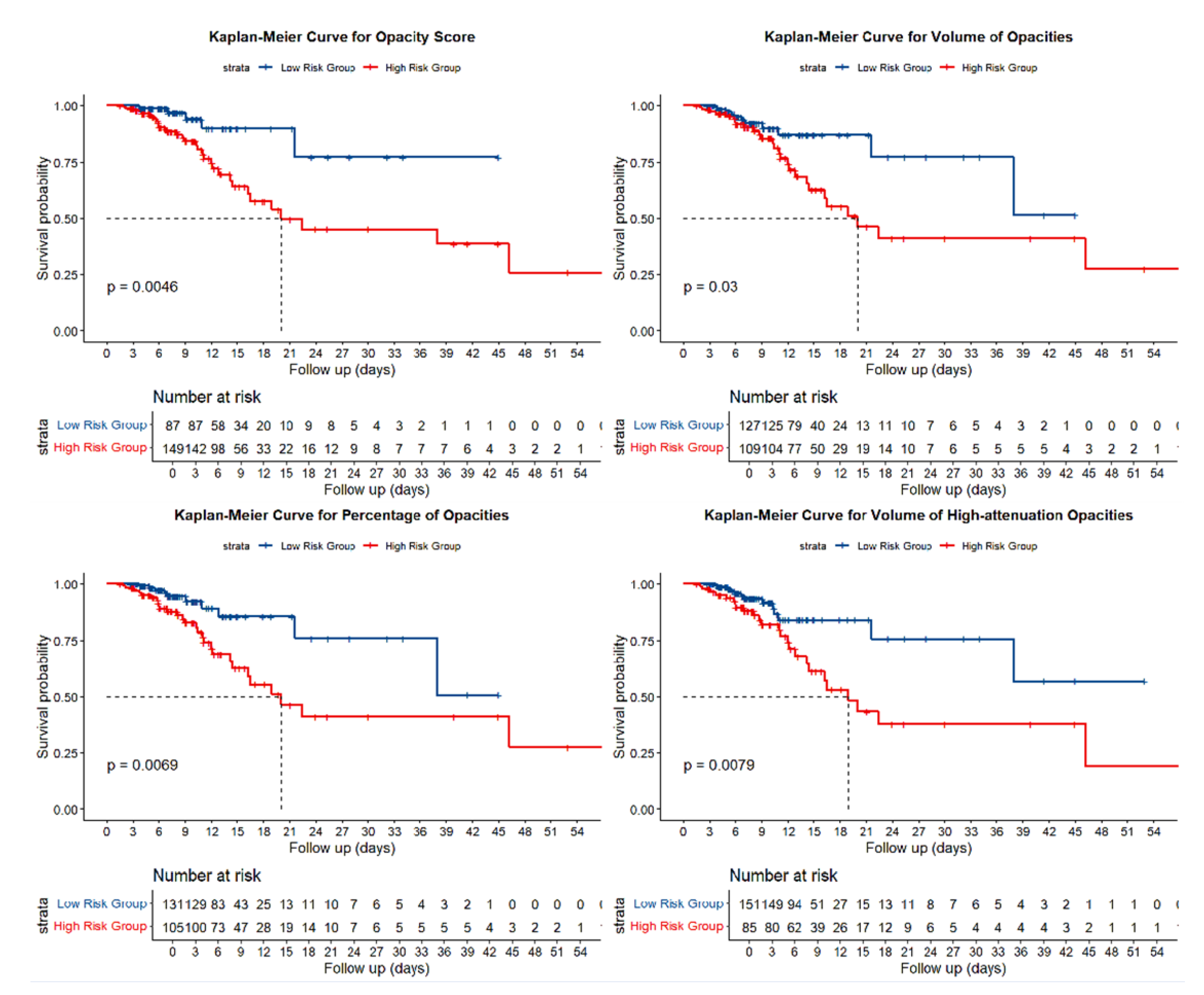

Objective: To determine whether deep-learning–derived quantitative HRCT parameters, combined with clinical characteristics, can predict in-hospital adverse outcomes and long-term reinfection in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Methods: We retrospectively analyzed 236 RT-PCR–confirmed patients who underwent HRCT between November 2022 and January 2023 at the Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan Medical College. Pulmonary inflammatory regions were automatically segmented, and quantitative metrics—including opacity score, lesion volume and percentage, high-attenuation lesion volume and percentage, and mean total-lung attenuation—were extracted using an artificial-intelligence pneumonia analysis prototype (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany). Optimal thresholds derived from receiver-operating-characteristic curves for the composite endpoint of intensive-care-unit admission or all-cause death were applied to stratify patients. Cox proportional-hazards models were used to identify independent predictors of adverse outcomes and subsequent SARS-CoV-2 reinfection. Results: Adverse outcomes occurred in 16.1% of patients. Higher opacity scores, larger lesion burdens, greater proportions of high-attenuation opacities, and higher mean lung attenuation were all associated with poorer outcomes (all P < 0.05). After adjusting for age and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, an opacity score ≥ 5.5 (HR = 3.02), lesion percentage ≥ 18.85% (HR = 2.33), and mean attenuation ≥ −662.4 HU (HR = 2.20) remained independent predictors. During a median follow-up of 603 days, opacity score ≥ 5.5 (HR = 5.32), high-attenuation volume ≥ 140.37 ml (HR = 3.81), and high-attenuation percentage ≥ 4.94% (HR = 3.39) independently predicted reinfection (all P ≤ 0.027). Conclusions: Deep-learning–based quantitative HRCT metrics provide incremental prognostic information for risk stratification of both acute adverse outcomes and long-term reinfection among COVID-19 patient.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Characteristics

2.2. Follow-Up

2.3. CT Examinations and Imaging Evaluation

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patients Characteristics

3.2. Association Between HRCT Parameters and Adverse Outcomes

3.3. Association Between HRCT Parameters and SARS-CoV-2 Reinfection

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard [EB/OL]. https://covid19.who.int/.

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 epidemiological update – [EB/OL]. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covid-19-epidemiological-update-edition-177. 12 March.

- Fontanet A, Autran B, Lina B, et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants and ending the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet, 2021, 397(10278): 952-4.

- Lundberg A L, Soetikno A G, Wu S A, et al. Updated Surveillance Metrics and History of the COVID-19 Pandemic (2020-2023) in East Asia and the Pacific Region: Longitudinal Trend Analysis. JMIR Public Health Surveill, 2025, 11: e53214.

- Ai T, Yang Z, Hou H, et al. Correlation of Chest CT and RT-PCR Testing for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: A Report of 1014 Cases. Radiology, 2020, 296(2): E32-e40.

- Li L, Qin L, Xu Z, et al. Using Artificial Intelligence to Detect COVID-19 and Community-acquired Pneumonia Based on Pulmonary CT: Evaluation of the Diagnostic Accuracy. Radiology, 2020, 296(2): E65-e71.

- Ardali Duzgun S, Durhan G, Basaran Demirkazik F, et al. AI-Based Quantitative CT Analysis of Temporal Changes According to Disease Severity in COVID-19 Pneumonia. J Comput Assist Tomogr, 2021, 45(6): 970-8.

- Wang S, Zha Y, Li W, et al. A fully automatic deep learning system for COVID-19 diagnostic and prognostic analysis. Eur Respir J, 2020, 56(2).

- Markmann A J, Giallourou N, Bhowmik D R, et al. Sex Disparities and Neutralizing-Antibody Durability to SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Convalescent Individuals. mSphere, 2021, 6(4): e0027521.

- Swartz M D, DeSantis S M, Yaseen A, et al. Antibody Duration After Infection From SARS-CoV-2 in the Texas Coronavirus Antibody Response Survey. J Infect Dis, 2023, 227(2): 193-201.

- Danzetta M L, Amato L, Cito F, et al. SARS-CoV-2 RNA Persistence in Naso-Pharyngeal Swabs. Microorganisms, 2020, 8(8).

- Kellam P, Barclay W. The dynamics of humoral immune responses following SARS-CoV-2 infection and the potential for reinfection. J Gen Virol, 2020, 101(8): 791-7.

- Sharma R, Sardar S, Mohammad Arshad A, et al. A Patient with Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection Who Presented 86 Days Later with COVID-19 Pneumonia Possibly Due to Reinfection with SARS-CoV-2. Am J Case Rep, 2020, 21: e927154.

- Kim A Y, Gandhi R T. Reinfection With Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2: What Goes Around May Come Back Around. Clin Infect Dis, 2021, 73(9): e3009-e12.

- Ugurel O M, Ata O, Turgut-Balik D. An updated analysis of variations in SARS-CoV-2 genome. Turk J Biol, 2020, 44(3): 157-67.

- Arru C, Ebrahimian S, Falaschi Z, et al. Comparison of deep learning, radiomics and subjective assessment of chest CT findings in SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia. Clin Imaging, 2021, 80: 58-66.

- Homayounieh F, Bezerra Cavalcanti Rockenbach M A, Ebrahimian S, et al. Multicenter Assessment of CT Pneumonia Analysis Prototype for Predicting Disease Severity and Patient Outcome. J Digit Imaging, 2021, 34(2): 320-9.

- Veiga V C, Cavalcanti A B. Age, host response, and mortality in COVID-19. Eur Respir J, 2023, 62(1).

- Wark P A B, Pathinayake P S, Eapen M S, et al. Asthma, COPD and SARS-CoV-2 infection (COVID-19): potential mechanistic insights. Eur Respir J, 2021, 58(2).

- McManus D, Davis M W, Ortiz A, et al. Immunomodulatory Agents for Coronavirus Disease-2019 Pneumonia. Clin Chest Med, 2023, 44(2): 299-319.

- Kurt A F, Mete B, Urkmez S, et al. Incidence, Risk Factors, and Prognosis of Bloodstream Infections in COVID-19 Patients in Intensive Care: A Single-Center Observational Study. J Intensive Care Med, 2022, 37(10): 1353-62.

- Schweiger A, Trevino S, Marschall J. Nosocomial infections in dialysis access. Contrib Nephrol, 2015, 184: 205-21.

- Xu H G, Tian M, Pan S Y. Clinical utility of procalcitonin and its association with pathogenic microorganisms. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci, 2022, 59(2): 93-111.

- Aon M, Alsaeedi A, Alzafiri A, et al. The Association between Admission Procalcitonin Level and The Severity of COVID-19 Pneumonia: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Medicina (Kaunas), 2022, 58(10).

- Linscheid P, Seboek D, Nylen E S, et al. In vitro and in vivo calcitonin I gene expression in parenchymal cells: a novel product of human adipose tissue. Endocrinology, 2003, 144(12): 5578-84.

- Schuetz P, Wirz Y, Sager R, et al. Procalcitonin to initiate or discontinue antibiotics in acute respiratory tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2017, 10(10): Cd007498.

- Casartelli C, Perrone F, Balbi M, et al. Review on radiological evolution of COVID-19 pneumonia using computed tomography. World J Radiol, 2021, 13(9): 294-306.

- Liu Y, Zhou X, Liu X, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the CT imaging characteristics of infectious pneumonia. Ann Palliat Med, 2021, 10(10): 10414-24.

- Zhou Y, Ren H, Wang S, et al. The evolution of chest CT findings from admission to follow-up in 30 moderate to severe adult patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Chin J Acad Radiol, 2021, 4(1): 71-7.

- Balasubramaniam S, Raju B P, Perumpallipatty Kumarasamy S, et al. Lung Involvement Patterns in COVID-19: CT Scan Insights and Prognostic Implications From a Tertiary Care Center in Southern India. Cureus, 2024, 16(1): e53335.

- Savoia P, Valente Yamada Sawamura M, de Almeida Monteiro R A, et al. Postmortem chest computed tomography in COVID-19: A minimally invasive autopsy method. Eur J Radiol Open, 2024, 12: 100546.

- Ackermann M, Verleden S E, Kuehnel M, et al. Pulmonary Vascular Endothelialitis, Thrombosis, and Angiogenesis in Covid-19. N Engl J Med, 2020, 383(2): 120-8.

- Liu D, Zhang W, Pan F, et al. The pulmonary sequalae in discharged patients with COVID-19: a short-term observational study. Respir Res, 2020, 21(1): 125.

- Pan F, Yang L, Liang B, et al. Chest CT Patterns from Diagnosis to 1 Year of Follow-up in Patients with COVID-19. Radiology, 2022, 302(3): 709-19.

- Zhao W, Zhong Z, Xie X, et al. Relation Between Chest CT Findings and Clinical Conditions of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pneumonia: A Multicenter Study. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 2020, 214(5): 1072-7.

- Nishiyama A, Kawata N, Yokota H, et al. A predictive factor for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: CT lung volumetry of the well-aerated region as an automated method. Eur J Radiol, 2020, 122: 108748.

- Lanza E, Muglia R, Bolengo I, et al. Quantitative chest CT analysis in COVID-19 to predict the need for oxygenation support and intubation. Eur Radiol, 2020, 30(12): 6770-8.

- Shen C, Yu N, Cai S, et al. Quantitative computed tomography analysis for stratifying the severity of Coronavirus Disease 2019. J Pharm Anal, 2020, 10(2): 123-9.

- Wang Y C, Luo H, Liu S, et al. Dynamic evolution of COVID-19 on chest computed tomography: experience from Jiangsu Province of China. Eur Radiol, 2020, 30(11): 6194-203.

- Lyu P, Liu X, Zhang R, et al. The Performance of Chest CT in Evaluating the Clinical Severity of COVID-19 Pneumonia: Identifying Critical Cases Based on CT Characteristics. Invest Radiol, 2020, 55(7): 412-21.

- Li Y, Hu H, Liu J, et al. Crucial role played by CK8(+) cells in mediating alveolar injury remodeling for patients with COVID-19. Virol Sin, 2024, 39(3): 390-402.

- Meyerholz D K, Reznikov L R. Influence of SARS-CoV-2 on airway mucus production: A review and proposed model. Vet Pathol, 2022, 59(4): 578-85.

- Vijaykumar K, Leung H M, Barrios A, et al. COVID-19 Causes Ciliary Dysfunction as Demonstrated by Human Intranasal Micro-Optical Coherence Tomography Imaging. bioRxiv, 2022.

- Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med, 2021, 27(4): 601-15.

| Parameter | Non-Adverse Outcomes Group (n=198) | Adverse Outcomes Group (n=38) | z/χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Age, year | 73.00(59.00,81.00) | 78.00(71.50,84.25) | -2.66 | 0.01 |

| Male | 120(60.61) | 28(73.68) | 2.33 | 0.13 |

| Smoke | 35(17.68) | 9(23.68) | 0.76 | 0.38 |

| Hypertension | 96(48.49) | 17(44.74) | 0.18 | 0.67 |

| Diabetes | 94(47.48) | 23(60.53) | 2.17 | 0.14 |

| Cardiac insufficiency | 31(15.66) | 14(36.84) | 9.27 | 0.00 |

| CHD | 92(46.47) | 25(65.79) | 4.76 | 0.03 |

| Cerebral infarction | 31(15.66) | 6(15.79) | 0 | 0.98 |

| Bronchiectasis | 11(5.56) | 1(2.63) | 0.57 | 0.45 |

| COPD | 24(12.12) | 10(26.32) | 5.21 | 0.02 |

| Emphysema | 48(24.24) | 13(34.21) | 1.65 | 0.20 |

| Asthma | 2(1.01) | 0(0.00) | 0.39 | 0.53 |

| Concurrent with F/B | 14(7.07) | 11(28.95) | 16.11 | 0.00 |

| Laboratory parameters | ||||

| WBC, ×10^9/L | 6.69(5.23,9.19) | 9.63(5.34,13.57) | -2.42 | 0.02 |

| LYM% | 14.30(9.25,20.60) | 6.35(3.60,10.03) | -4.83 | 0.00 |

| IL-6, ng/L | 27.38(8.13, 109.68) | 109.68(49.56, 274.00) | -5.37 | 0.00 |

| D-dimer, mg/L | 1.77(1.15,4.78) | 5.07(2.18,15.54) | -4.86 | 0.00 |

| CRP, mg/L | 63.78(15.68,81.33) | 84.61(44.07, 154.70) | -3.48 | 0.00 |

| PCT, mg/mL | 0.09(0.05,0.75) | 0.78(0.17,1.46) | -4.61 | 0.00 |

| ESR, mm/h | 58.92(48.00,60.50) | 58.92(42.75,65.25) | -0.18 | 0.86 |

| CT-based lung parameters | ||||

| Opacity score | 6.00(5.00,10.00) | 9.50(6.00,14.00) | -4.04 | 0.00 |

| Lung volume | 2936.33(2523.18,3541.56) | 3107.06(2555.71,3670.27) | -0.69 | 0.49 |

| Volume of opacities | 426.30(164.62,906.45) | 925.03(452.09,1571.74) | -4.18 | 0.00 |

| Percentage of opacities | 13.33(5.03,34.33) | 32.78(14.53,55.98) | -3.85 | 0.00 |

| Volume of high-attenuation opacities | 63.48(22.50,214.23) | 236.28(67.10,469.82) | -3.97 | 0.00 |

| Percentage of high-attenuation opacities | 2.04(0.70,7.31) | 7.67(2.53,14.84) | -3.73 | 0.00 |

| Mean HU total | -714.53(-763.02, -639.27) | -649.66(-742.91, -572.64) | -2.70 | 0.01 |

| Mean HU of opacity | -471.04(-530.67, -421.24) | -443.12(-502.80, -367.68) | -1.81 | 0.07 |

| Parameter | Non-Reinfection Group (n=175) | Reinfection Group (n=15) | z/χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Age, year | 72.00(59.00, 81.00) | 78.50(63.50, 84.00) | -1.06 | 0.28 |

| Male | 105 (60.00) | 12(66.67) | 0.30 | 0.58 |

| Smoke | 31 (17.71) | 5(27.78) | 1.09 | 0.34 |

| Hypertension | 86(49.14) | 6(33.33) | 1.64 | 0.20 |

| Diabetes | 83(47.43) | 7(38.89) | 0.48 | 0.49 |

| Cardiac insufficiency | 28(16.00) | 2(11.11) | 0.30 | 0.74 |

| CHD | 80(45.71) | 9(50.00) | 0.12 | 0.73 |

| Cerebral infarction | 25(14.29) | 4(22.22) | 0.81 | 0.48 |

| Bronchiectasis | 7(4.00) | 2(11.11) | 1.86 | 0.20 |

| COPD | 22(12.57) | 2(11.11) | 0.03 | 1.00 |

| Emphysema | 41(23.429) | 5(27.78) | 0.17 | 0.77 |

| Asthma | 2(1.14) | 0(0.00) | 0.21 | 1.00 |

| Concurrent with F/B | 12(6.86) | 2(11.11) | 0.44 | 0.63 |

| Laboratory parameters | ||||

| WBC, ×10^9/L | 6.69(5.30, 9.19) | 7.01(4.66, 9.16) | -0.27 | 0.79 |

| LYM% | 14.40 (9.40, 21.30) | 13.10 (7.95, 18.40) | -0.92 | 0.36 |

| IL-6, ng/L | 24.26 (7.33, 109.68) | 58.23 (17.77, 109.68) | -1.34 | 0.18 |

| D-dimer, mg/L | 1.75 (1.06, 5.01) | 2.02 (1.36, 4.48) | -0.80 | 0.43 |

| CRP, mg/L | 62.75 (13.91, 81.70) | 71.43 (49.81, 81.14) | -1.23 | 0.22 |

| PCT, mg/mL | 0.08 (0.05,0.59) | 0.60 (0.05, 8.27) | -1.94 | 0.05 |

| ESR, mm/h | 58.92 (48.00, 59.00) | 58.92 (58.92, 74.00) | -1.43 | 0.15 |

| CT-based lung parameters | ||||

| Opacity score | 6.00 (5.00,9.00) | 10.50(6.75, 12.25) | -3.12 | 0.00 |

| Lung volume | 2943.86 (2513.01, 3552.76) | 3024.37 (2716.19, 3825.59) | -0.50 | 0.62 |

| Volume of opacities | 365.03(165.00,875.37) | 829.10 (437.09, 1478.28) | -2.57 | 0.01 |

| Percentage of opacities | 13.00 (4.71,32.34) | 30.38 (11.97, 51.28) | -2.47 | 0.01 |

| Volume of high-attenuation opacities | 55.46 (22.20,182.03) | 204.79 (105.81, 371.80) | -2.93 | 0.00 |

| Percentage of high-attenuation opacities | 1.91 (0.68, 6.39) | 6.31 (3.01, 13.15) | -2.63 | 0.01 |

| Mean HU total | -715.37 (-764.83, -640.42) | -669.24 (-757.24, -560.53) | -1.44 | 0.15 |

| Mean HU of opacity | -474.12 (-530.57, -423.33) | -440.94 (-491.70, -371.55) | -1.66 | 0.10 |

| Adverse Outcomes | Reinfection | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||||||

| Parameter | HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P |

| Opacity score | 3.59 | 1.40-9.22 | 0.01 | 3.02 | 1.17-7.81 | 0.02 | 6.06 | 1.39-26.36 | 0.02 | 5.32 | 1.21-23.46 | 0.03 |

| Lung volume | 0.83 | 0.44-1.58 | 0.57 | 1.21 | 0.48-3.04 | 0.69 | ||||||

| Volume of opacities | 2.15 | 1.06-4.36 | 0.03 | 2.18 | 0.85-5.62 | 0.11 | ||||||

| Percentage of opacities | 2.63 | 1.27-5.45 | 0.01 | 2.33 | 1.12-4.84 | 0.02 | 1.92 | 0.76-4.86 | 0.17 | |||

| Volume of high-attenuation opacities | 2.43 | 1.24-4.77 | 0.01 | 3.68 | 1.43-9.49 | 0.01 | 3.81 | 1.46-9.97 | 0.01 | |||

| Percentage of high-attenuation opacities | 1.84 | 0.94-3.59 | 0.08 | 3.24 | 1.26-8.37 | 0.02 | 3.39 | 1.29-8.90 | 0.01 | |||

| Mean HU total | 2.48 | 1.28-4.82 | 0.01 | 2.20 | 1.12-4.30 | 0.02 | 2.41 | 0.96-6.07 | 0.06 | |||

| Mean HU of opacity | 1.58 | 0.83-2.99 | 0.16 | 2.25 | 0.89-5.69 | 0.09 | ||||||

| Multivariate analysis for adverse outcomes was adjusted for age and COPD, while the analysis for reinfection was adjusted for PCT. | ||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).