1. Introduction

As of early 2025, over 5 billion people were active social media users, representing roughly 62.3% of the world’s population [

1]. These social media platforms are dominated by highly curated visual content, which is now recognized as a key driver of appearance-related pressures [

1]. Frequent exposure to appearance-focused images tends to widen the perceived discrepancies between one’s own appearance and societal beauty ideals, thereby undermining body satisfaction. Empirical studies support this effect. For instance, on Instagram (a visually-driven platform), idealized celebrity and peer images have been linked to lower body satisfaction and negative mood among young women[

2]. Similarly, experimental exposure to “fitspiration” videos on TikTok increases negative mood and, through heightened appearance comparison, leads to greater body dissatisfaction[

3].

However, the social media landscape in China differs significantly from that of Western countries. In China, western social media platforms such as Instagram and Pinterest are inaccessible due to government restrictions, which has created opportunities for domestic alternatives like Xiaohongshu to gain popularity and flourish[

4]. Xiaohongshu blends features of Instagram and Pinterest, focusing on image-centric posts and aspirational lifestyle content. It now boasts around 300 million monthly active users, with young women forming the majority of its user base[

5]. However, despite its popularity and aspirational content, Xiaohongshu has faced criticism for saturating young users with idealized images, raising concerns that these portrayals promote unrealistic beauty ideals and distort young women’s body-image perceptions. An emerging body of research indicates that repeated exposure to idealized body images on Xiaohongshu prompts automatic upward comparisons with highly curated influencers, which contributes to negative self-evaluations, diminished body satisfaction, and heightened appearance-related anxiety among female users[

5,

6]. Given that Xiaohongshu’s user demographic is predominantly female and that many of these users actively aspire to attain a ‘perfect' face and figure, they are at heightened risk of these adverse psychological effects. In other words, young women who regularly compare themselves to the platform’s unattainable beauty ideals may experience deeper dissatisfaction with their own looks and even long-term mental health consequences. In this context, it becomes crucial to explore accessible, evidence-based interventions to lessen social media’s adverse effects on the body image of Chinese young women.

As a psychological intervention, mindfulness meditation effectively targets body-image difficulties while fostering emotional well-being[

7,

8]. Mindfulness involves intentionally regulating one’s attention on present-moment experiences with a nonjudgmental, accepting attitude[

9,

10]. In the context of body image, mindfulness appears to operate through three distinct pathways. First, it encourages a nonjudgmental awareness of oneself and cultivates self-compassion. These qualities directly counter the negative self-evaluations central to body image concerns[

11]. Second, mindfulness enables psychological distance from distressing body-related thoughts and emotions. This decentering process promotes cognitive flexibility and can reduce automatic, maladaptive reactions (e.g., rumination, anxiety, depressed mood, or unhealthy weight-control behaviors)[

12,

13]. Third, mindfulness fosters continuous observation and acceptance of distressing experiences, as opposed to avoidance. Over time, this stance can decrease overall distress through mechanisms such as extinction of fear responses and adaptive learning[

14]. A growing body of literature suggests that mindfulness meditation may serve as a protective factor against negative body image. For example, Delinsky and Wilson[

15] found that combining mindfulness training with mirror exposure significantly decreased participants’ emotional reactivity related to their body image after only three training sessions. Similarly, another study found that women who practiced mindfulness during a swimsuit try-on session reported lower negative affect and reduced body dissatisfaction[

16].

In recent years, mindfulness-based interventions aimed at improving body image have received increasing attention in the literature. However, relatively few studies have examined whether mindfulness can function as a protective factor by buffering the detrimental impact of appearance-focused social media platforms. This underexplored topic indicates a notable gap in existing research, underscoring the novelty and importance of further investigation. Additionally, most existing studies prioritize multi-session mindfulness interventions to address women’s body image[

17,

18], whereas brief, one-off sessions remain relatively neglected. To date, only one study has specifically examined the efficacy of a brief, single-session mindfulness intervention. In that study, Atkinson and Diedrichs [

19] found that a 15-minute video incorporating practical mindfulness techniques (e.g., thought decentering and mindful breathing) significantly enhanced positive internalization of appearance ideals, reduced sociocultural pressures related to appearance, and alleviated negative affect among female university students. These preliminary findings highlight the promise of brief mindfulness interventions, given that their short duration makes them relatively easy to integrate into daily routines. They can offer rapid, in-the-moment relief during challenging situations. Accordingly, additional empirical work is warranted to evaluate the effectiveness of brief mindfulness interventions for body-image concerns.

As previously reviewed, evidence suggests that a brief, single-session mindfulness meditation can serve as an accessible, effective tool to lessen body-image distress triggered by upward comparisons to idealized Xiaohongshu images. However, no research to date has directly tested whether engaging in such mindfulness exercises can truly mitigate or prevent body-image distress prompted by these social media triggers. Therefore, the present study examined whether administering a ten-minute mindfulness meditation before young Chinese women engage with Xiaohongshu would diminish the body dissatisfaction and negative mood typically induced by exposure to idealized images on that platform. Specifically, we hypothesized that women who completed the mindfulness intervention would report lower immediate body dissatisfaction and a less negative mood than those in a control group. Furthermore, we hypothesized that the intervention group would maintain these improvements even after being exposed to idealized body images on Xiaohongshu and instructed to compare themselves to those images, whereas the control group was expected to exhibit the typical increase in body dissatisfaction and negative mood in response to that exposure.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design

We conducted an online randomized controlled experiment in which participants were randomly assigned to either the mindfulness intervention or a control group. Those in the intervention group listened to a ten-minute mindfulness audio, and those in the control group listened to a matched ten-minute natural-history recording. After completing their respective audio sessions, participants viewed idealized body images from a researcher-curated Xiaohongshu profile and subsequently compared themselves to these images. Outcome variables were measured at baseline, post-intervention, and post exposure to images. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by Ethics Committee of School of Language and Communication, Beijing Jiaotong University (approval code: BJTU2025060501). This trial was registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (registration no. ChiCTR2500104893) on 25 June 2025. The randomized trial was reported in line with the CONSORT guidelines[

20].

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

We performed an a priori power analysis using G*Power 3.1 to determine the required sample size. This analysis assumed a medium effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.5), a two-tailed test with α=0.05, and a statistical power of 85%. This analysis indicated that a minimum of 73 participants per group was required. We then used purposive sampling to recruit individuals who met the inclusion criteria: (a) female, (b) 18–35 years of age, (c) stable internet access, and (d) normal or corrected-to-normal vision without color-vision deficits (including color blindness or weakness); Participants were excluded if they: (a) had engaged in any cognitive or mindfulness training within the past year (including structured programs or self-guided practice); (b) had any diagnosed psychiatric disorder (past or present) or any chronic physical illness.

Participant recruitment began in early July 2025 via volunteer recruitment advertisements posted on the first author’s personal Xiaohongshu social media account. Each advertisement provided a brief overview of the study, including its objectives, the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the requirements for participation. Interested individuals contacted the researcher via Xiaohongshu or WeChat to obtain additional details and undergo an initial eligibility screen. Participants deemed eligible ( having met all inclusion criteria) were then provided an online informed consent form. After reviewing the details of the form, participants gave their informed consent electronically prior to study commencement. By providing informed consent, participants indicated that they understood the study’s aims and affirmed their right to withdraw at any point without any impact on their employment status.

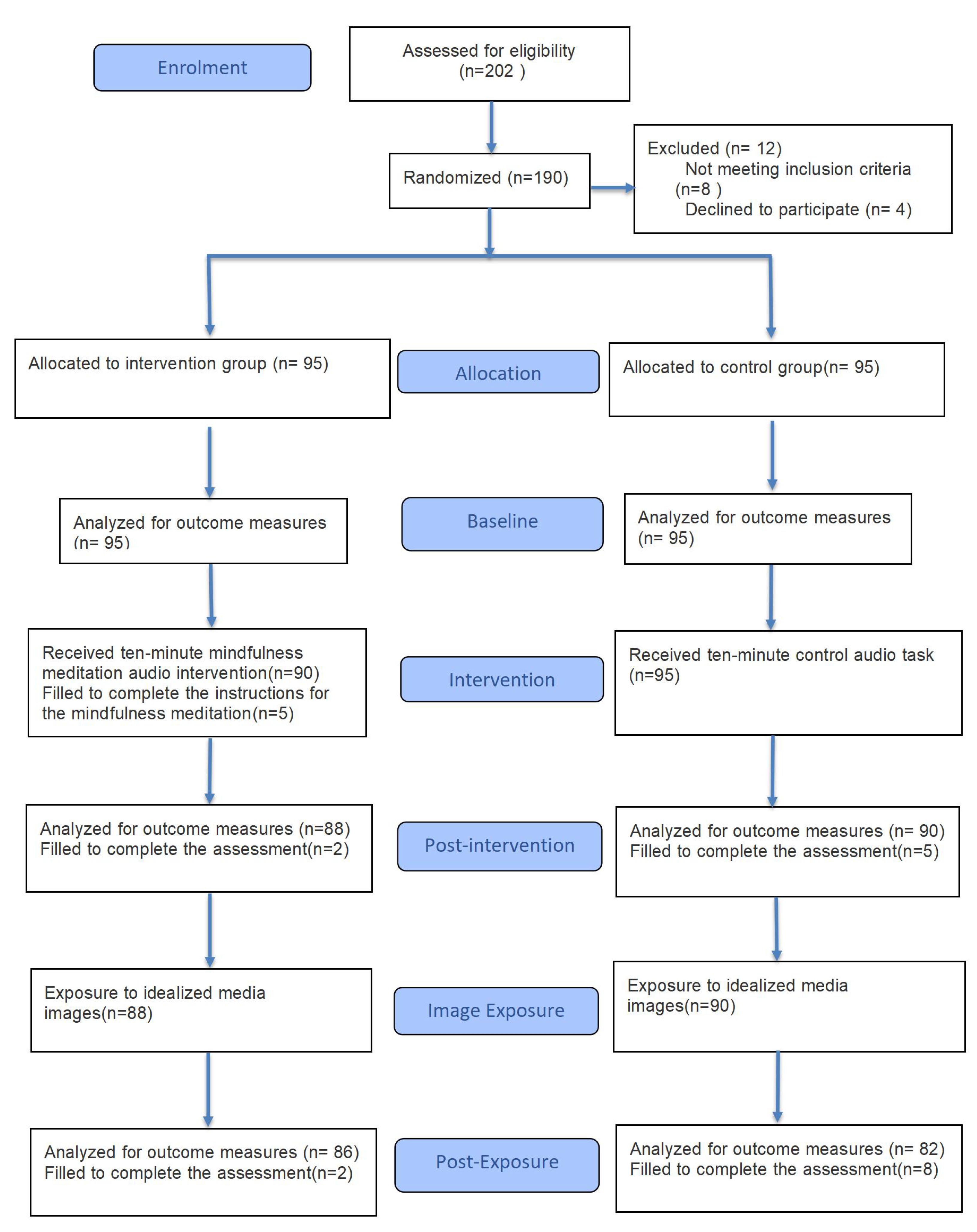

A total of 202 individuals were initially enrolled. Twelve did not proceed to the trial: eight did not meet the inclusion criteria and four declined participation. This left 190 participants who were randomized to the intervention or control group. During the intervention phase, five participants in the intervention group did not complete the ten-minute mindfulness session. At the immediate post-intervention assessment, an additional two participants in the intervention group and five in the control group did not complete the outcome measures. At the final post-exposure assessment, a further two participants in the intervention group and eight in the control group were missing. Consequently, the post-exposure analyses included 86 participants in the intervention group and 82 in the control group. Participant flow through the study is illustrated in the CONSORT flow diagram (

Figure 1 ).

Participants were allocated in a 1:1 ratio to the intervention or control group. To preserve balance, block randomization with blocks of four was implemented. The allocation sequence was produced by an independent researcher using a computer-based random number generator. To maintain allocation concealment, the researcher responsible for generating the randomization sequence did not participate in recruitment or enrollment. To maintain blinding, the researchers remained unaware of the randomization sequence and group assignments, and participants were not informed of their assigned group throughout the trial.

2.3. Procedure

All participants provided informed consent and volunteered to enroll. They received the online questionnaire via WeChat, which was designed and administered using the Credamo online survey platform (

www.credamo.com21). Eligible participants first completed baseline visual analog scale (VAS) assessments measuring state body dissatisfaction and negative mood. Following these baseline assessments, each participant listened to a ten-minute audio recording via the Credamo platform according to their assigned condition: those in the control group listened to a ten-minute audio recording of a natural history text, whereas those in the intervention group engaged in a ten-minute guided mindfulness meditation. Upon finishing the audio task, participants immediately completed a second set of post-intervention VAS assessments to reassess state body dissatisfaction and negative mood. Subsequently, participants viewed a set of idealized images (see Image Selection for details) and completed a forced appearance-comparison task intended to induce body dissatisfaction and negative mood. For each image, participants were instructed to compare specific body parts of the woman depicted with the corresponding parts of their own bodies. Participants indicated whether each of nine body areas (thighs, arms, buttocks, waist, hips, biceps, breasts, legs, and stomach) was “much smaller,” “smaller,” “about the same size,” “larger,” or “much larger” than the corresponding area on the woman in the image. In addition, participants evaluated the attractiveness of their own face and their overall physical appearance in comparison to the woman in the image. They indicated whether they perceived themselves to be “much more attractive,” “slightly more attractive,” “about as attractive,” “less attractive,” or “much less attractive” than the woman. Such forced social comparison tasks were widely employed in prior research investigating body image responses to idealized media images[

22,

23,

24,

25]. In the present study, this approach enabled us to examine whether the mindfulness intervention could mitigate any body distress stemming from young women’s exposure to appearance-focused social media content. Finally, after viewing the idealized images, participants completed a third set of VAS assessments and provided their demographic information.

2.4. Interventions

We replicated the mindfulness meditation and control task scripts from Fraser et al.,[

26].The script for the audio recording was provided by the original study’s authors. It was then adapted for use in the current study. Specifically, two independent bilingual experts were engaged to carry out the translations.The script was back-translated into English by a separate set of bilingual researchers to ensure accurate capture of the original meanings. Subsequently, two experts in mindfulness meditation reviewed the translated text. Their goal was to ensure that Chinese participants could fully understand all content and details in both audio recordings. Any discrepancies identified were addressed by the researchers. This procedure ensured semantic equivalence and cultural suitability of the final versions for the Chinese context[

27]. Both audio recordings were made by the same individual (an instructor certified in the Mindfulness Intervention for Emotional Distress [MIED] program, Peking University Continuing Education, 2024[

28]) and were of equal task length (i.e., ten minutes).

2.4.1. Intervention Group

Participants assigned to the intervention group completed a ten-minute guided meditation designed to enhance present-moment awareness. During the session, they were encouraged to focus on their breath and other bodily sensations, such as sounds, sights, and touch. The meditation encouraged an attitude of acceptance and nonjudgment toward these sensations. Participants were specifically guided to observe their thoughts and physical sensations without evaluation throughout the session. Notably, this exercise was not centered on body image. Previous research has demonstrated that listening to this mindfulness recording significantly enhances state mindfulness levels in participants, as compared to a control group[

26].

2.4.2. Control Group

Participants assigned to the control group listened to a ten-minute audio recording of a passage from a natural history text, which was described as neutral yet relaxing[

26].

2.5. Image Selection

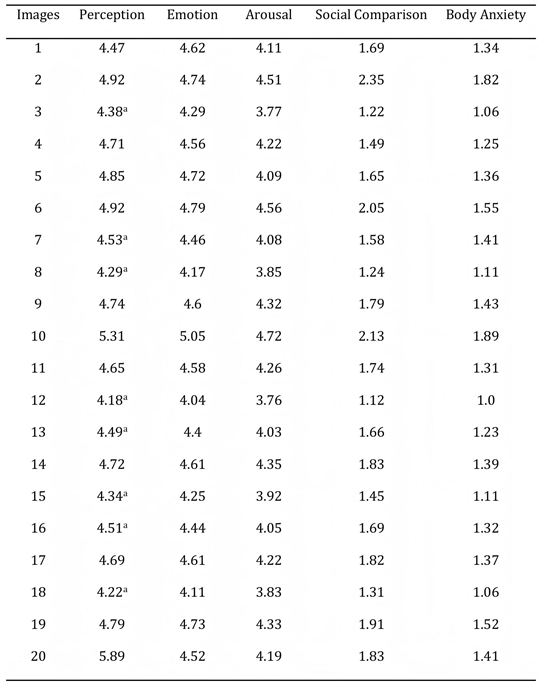

After completing one of the interventions outlined above, participants viewed 12 idealized body images sourced from public Xiaohongshu accounts. Image selection followed a structured two-stage procedure informed by prior research[

29,

30]. In the first phase, 30 images were identified using the hashtags#PerfectBody, #BodyChallenge, #AppearanceIcon, #FitnessGoddess, and #FullBodyShot. These hashtags were purposefully selected to capture portrayals of women consistent with dominant beauty ideals in China. In the second phase, after consulting with three expert researchers in body-image research, the initial set of 30 images was refined to 20. The selection was made according to key criteria: each image needed to have clearly visible facial features, a recognizable body type, and a full-body presentation. Subsequently, twenty young women aged 18–35 were recruited through the Xiaohongshu account of the first researcher to pretest the 20 images. They rated the images based on five dimensions using 5-point Likert scales (see

Table 1): (1) Emotion (5 = Very good, 1 = Very bad), (2) Perception (5 = Very good, 1 = Very bad), (3) Arousal (5 = Very excited, 1 = Not excited at all), (4) Body Anxiety (5 = Always, 1 = Not at all), and (5) Social Comparison (5 = Always, 1 = Not at all). This method was previously employed by Li et al.[

31]to assess the idealization of female images from social media, demonstrating strong evaluation efficacy, which is why we adopted it for the current study. The mean score for each dimension was calculated for every image. A hierarchical ranking was then applied to derive the final set of 12 images, giving primary weight to Body Anxiety and Social Comparison, followed by Perception, Emotion, and Arousal, to maximize stimulus engagement and relevance. These images were then presented to participants through a curated, simulated Xiaohongshu profile specifically created for this study. All visible social feedback (e.g., 'like' counts and comments) was concealed to ensure that each image was viewed in a realistic context without extraneous social cues.

2.6. Outcome Measures

The questionnaire used in this study consisted of two main sections. The first section collected demographic characteristics (age, educational level ) along with self-reported height and weight to calculate body mass index (BMI; kg/m²). The second section assessed participants' state body dissatisfaction and mood using Visual Analogue Scales (VAS)[

32]. These assessments were conducted at three specific time points: baseline, post-intervention, and post-exposure to images. Participants indicated their current feelings by marking a point along a horizontal line anchored from 0 (not at all) to 100 (very much). Body dissatisfaction was evaluated using the averaged responses to three items: "fat," "physically attractive" (reverse-coded), and "satisfied with your body size" (reverse-coded). Higher scores indicated greater dissatisfaction with one’s body at that moment. Mood was assessed by averaging responses to five items: "depressed," "happy" (reverse-coded), "anxious," "angry," and "confident" (reverse-coded). Higher scores reflected a more negative mood state. Prior studies indicate that VAS provides reliable and sensitive measure of changes in body satisfaction and mood in young women, making it well suited to pre–post experimental designs[

8,

33,

34]. The VAS has also demonstrated good convergent validity and internal consistency, specifically among young adult women in China[

5]. In the present study, both mood and body dissatisfaction scales exhibited high internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.86, 0.89, and 0.88 for mood, and 0.90, 0.92, and 0.91 for body dissatisfaction at baseline, post-intervention, and post-exposure, respectively.

3. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 25). Descriptive statistics summarized participant characteristics and assessed state body dissatisfaction as well as negative mood. Continuous data were presented as Mean ± SD, while categorical data were reported as frequencies (N, %). An independent-sample t-test was performed to compare group differences in continuous variables. For categorical variables, the Pearson chi-square test was used to examine group differences.

Consistent with the study's hypotheses, linear mixed-effects models were employed to determine whether the intervention condition (compared to the control condition) influenced state body dissatisfaction and negative mood over time. Two separate models were specified to examine the effects on each of these two dependent variables. To measure differences in the rate of change from post-intervention to post-exposure, time was coded into two dummy variables. The first dummy variable captured the contrast between baseline and post-intervention (baseline coded as 1, post-intervention as 0); the second dummy variable captured the contrast between post-intervention and post-exposure (post-intervention coded as 0, post-exposure as 1). Condition (Intervention group vs. Control group) and its interaction with time were included as predictors in each model. This analytical approach enabled the examination of the rate of change in the dependent variables over time, as well as differences in this rate between groups. To further investigate the interaction between condition and time, simple effects of time within each condition were examined. The condition variable was re-coded in two ways (first coding the control group as 0 and the intervention group as 1, then reversing the coding), so each group served as the reference category in one of the analyses. This design enabled a separate evaluation of within-group changes in both the intervention and control groups. Effect sizes for these changes were calculated as Cohen’s d. Estimates of the fixed effects from these models were reported below.

4. Results

4.1. Demographics and Baseline Information of Participants

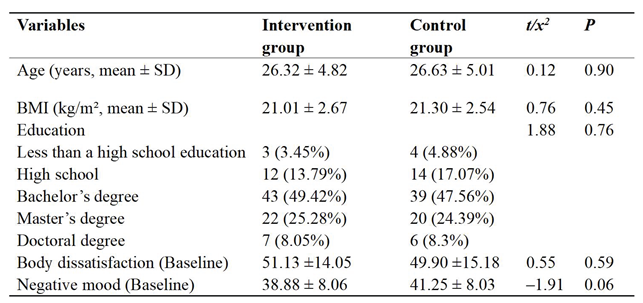

As shown in

Table 2, participants were young adults (age range: 17–35 years), with mean ages of 26.32 years (SD = 4.82) in the intervention group and 26.63 years (SD = 5.01) in the control group. BMI values ranged from 18.32 to 24.54 kg/m², indicating a healthy weight range on average (M = 21.01, SD = 2.67 for intervention; M = 21.30, SD = 2.54 for control). In terms of education, most participants held a bachelor’s degree's degree (intervention group: 43 participants, 48.83%; control group: 39 participants, 47.56%), followed by smaller proportions holding master's degrees (intervention group: 25.58%; control group: 24.39%) and doctoral degrees (intervention group: 8.13%; control group: 8.3%).

Baseline measurements indicated average body dissatisfaction scores of 51.13 (SD = 14.05) for the intervention group and 49.90 (SD = 15.18) for the control group. Additionally, average negative mood scores were 38.88 (SD = 8.06) and 41.25 (SD = 8.03), respectively. Statistical analyses showed that the intervention and control groups did not differ significantly in age (t = 0.12, p = 0.90), BMI (t = 0.76, p = 0.45), or education level (χ² = 1.88, p = 0.76). Similarly, baseline body dissatisfaction (t = 0.55, p = 0.59) and negative mood scores (t = -1.91, p = 0.06) showed no statistically significant group differences.

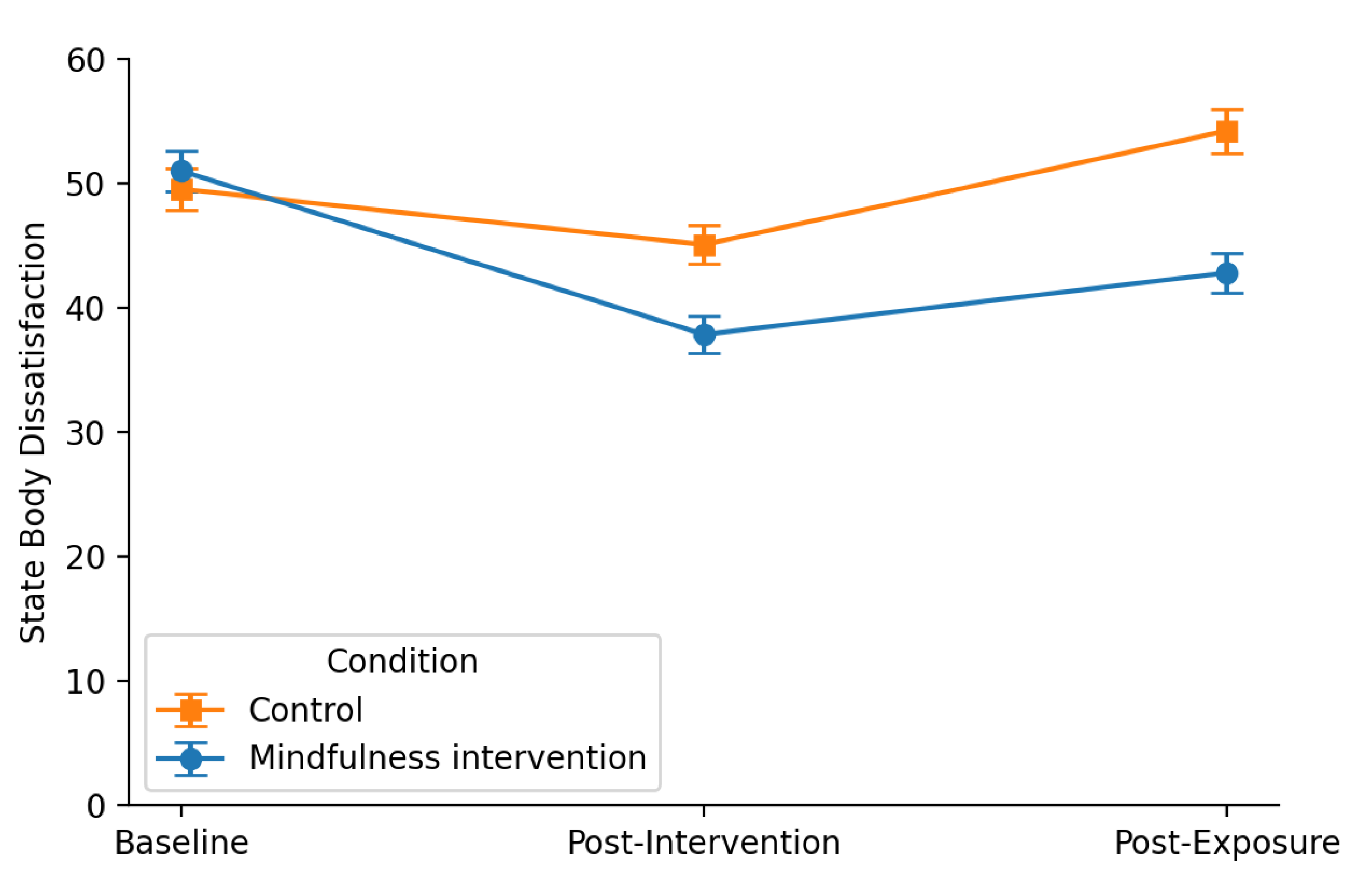

4.2. State Body Dissatisfaction

For state body dissatisfaction, the linear mixed-effects model (with random intercepts for participants) showed no significant Condition×Time interaction in the initial phase (baseline to post-intervention) (b = 4.42, p = 0.158, Cohen’s d = 0.14). By contrast, the Condition × Time interaction in the later phase (post-intervention to post-exposure) only approached significance (b = −5.01, p = 0.091, Cohen’s d = 0.39). Within the intervention condition, state body dissatisfaction decreased significantly from baseline to post-intervention (b = 3.95, SE = 1.22, p = 0.002, Cohen’s d = 0.49), with no significant change from post-intervention to post-exposure (b = 0.40, SE = 1.22, p = 0.742, Cohen’s d = 0.05). The control condition showed a similar initial improvement, with a significant decrease from baseline to post-intervention (b = 4.76, SE = 1.22, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.60). However, unlike the intervention condition, it exhibited a significant rebound in body dissatisfaction from post-intervention to post-exposure (b = 6.63, SE = 1.22, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.76). See

Figure 2.

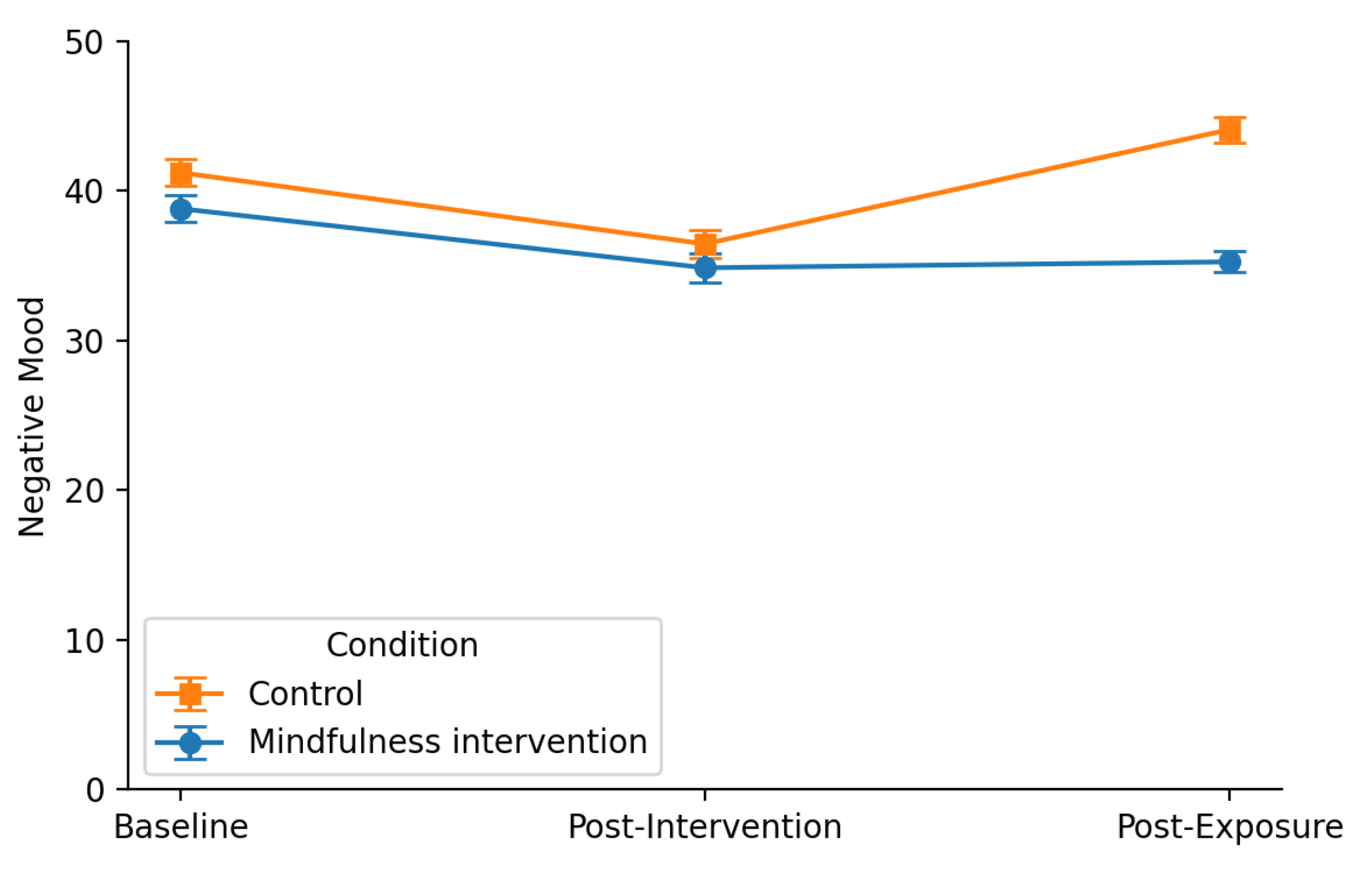

4.3. Negative Mood

For negative mood, the linear mixed-effects model revealed no significant Condition × Time interaction during the initial period (baseline to post-intervention: b = 0.45, SE = 1.12, p = .689, Cohen’s d = 0.05). However, a significant Condition × Time interaction was observed in the subsequent period (post-intervention to post-exposure)(b = -6.95, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = -0.79). In the intervention condition, negative mood decreased significantly from baseline to post-intervention (b = 4.67, SE = 0.79, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.53). This reduction in negative mood was maintained, with no significant change observed from post-intervention to post-exposure (b = 1.10, SE = 0.79, p = 0.164, Cohen’s d = 0.12). Similarly, the control condition showed a significant decrease in negative mood from baseline to post-intervention (b = 5.12, SE = 0.79, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.58). In the control group, this decrease was followed by a significant rebound in negative mood from post-intervention to post-exposure (b = 8.05, SE = 0.79, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.91). See

Figure 3.

5. Discussion

Appearance-focused social media platforms, such as Xiaohongshu, perpetuate unrealistic beauty standards within Chinese society. Because idealized social media images exert substantial influence on beauty norms among young Chinese women, there is an urgent need for effective psychological interventions to ameliorate the associated physical and mental health risks. To address this critical need, the present study investigated whether a brief audio-based mindfulness meditation, administered immediately before exposure to idealized body images on Xiaohongshu, could attenuate subsequent increases in body dissatisfaction and negative mood. Significantly, this is the first study to test a mindfulness-based intervention specifically addressing social media–related body-image concerns in young Chinese women.

We hypothesized that a mindfulness meditation session would lead to significantly lower levels of state body dissatisfaction and negative mood after the intervention, compared to the control task. However, the results only partially supported this hypothesis. As anticipated and consistent with previous research[

8,

35,

36], participants in the mindfulness group showed significant reductions in state body dissatisfaction and negative mood following the intervention. However, participants in the control group, who listened to a ten-minute audio recording of a natural history-text, also showed significant short-term reductions in these outcomes. Notably, both the mindfulness and control conditions led to comparable immediate improvements in body dissatisfaction and negative mood after their respective audio tasks. This finding contrasts with some prior research that reported minimal or no improvement in neutral control tasks[

37,

38], yet aligns with the findings of Gobin, McComb, and Mills (2022)[

30]. In their study, Gobin et al. found no significant between-group differences in weight and appearance dissatisfaction when comparing a self-compassion writing task to a neutral word-sorting exercise. They attributed these null findings to nonspecific factors, such as habituation, which may also explain the results of the current study. Specifically, repeated exposure to the experimental procedures may reduce participants' self-consciousness over time, thereby potentially lowering reported body dissatisfaction as participants become more comfortable with or less sensitive to the experimental context.

Our second hypothesis, which proposed that mindfulness meditation would act as a protective factor against body image distress triggered by exposure to idealized body images on Xiaohongshu, was supported by the results. Participants in the intervention group maintained lower levels of state body dissatisfaction and negative mood even after completing a forced appearance-comparison task with idealized body images on Xiaohongshu. In contrast, this protective effect was entirely absent in the active control group. Participants in this group listened to a ten-minute audio recording of a natural history text and experienced a significant increase in both outcomes.This finding contributes to a growing body of evidence that brief mindfulness exercises can alleviate media-induced harm to self-perception[

8,

19]. Critically, however, our study extends the existing literature by demonstrating the robustness of these protective effects under a direct and forced appearance-comparison condition, a scenario in which the efficacy of similar brief interventions has been shown to falter. For instance, some research has found that the initial benefits of a brief mindfulness intervention are nullified following subsequent exposure to thin-ideal images[

26].The success of our intervention in this more psychologically challenging paradigm constitutes a novel contribution, suggesting that mindfulness confers a resilient buffering effect precisely when the threat of social comparison is most salient. A plausible explanation for this robust effect is that mindfulness cultivates decentering,a metacognitive stance in which one observes thoughts and emotions as transient mental events rather than as accurate reflections of self-worth[

39].By creating this psychological distance, mindfulness likely interrupts the automatic cognitive routines of upward social comparison and the internalization of unattainable beauty ideals, thereby mitigating the potent emotional and cognitive disturbances that a direct comparison task is designed to elicit.

Our findings provide valuable empirical evidence for the growing field of micro-interventions, demonstrating that even a brief, single-session mindfulness exercise can serve as an immediate and accessible tool for mitigating social-media-related harm to body image [

20,

31,

40]. However, it is important to note that the efficacy of short-term mindfulness interventions remains inconsistent. Some studies suggest that its benefits depend on moderators such as one’s motivation to practice, the length of the session, and the frequency of practice[

41]. For example, greater practice frequency has been linked to higher positive affect and sustained well-being[

42]. Indeed, regular mindfulness practice cultivates a present-moment focus that improves attentional regulation and emotional awareness. This, in turn, reduces maladaptive automatic responses[

43,

44]. Given that our intervention was a brief, one-off session, it is unlikely to generate long-term buffering effects against appearance-focused social media content.

6. Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

This study addresses a significant gap in the field by providing the first randomized controlled trial evidence for the efficacy of a brief mindfulness intervention on social media-induced body dissatisfaction among young Chinese women. Research to date has largely been conducted with Western samples, leaving the dynamics of these psychological processes in non-Western populations underexplored. Our findings provide crucial Chinese data, demonstrating that the protective mechanisms of mindfulness are robust and transferable to a distinct sociocultural context. This is particularly significant given the high prevalence of body image concerns among young women in China, which are often driven by intense media pressure to conform to the unattainable beauty ideals found on appearance-focused social media platforms.

6.2. Practical Implications

The most significant practical implication of this study is the validation of a highly accessible, low-cost, and scalable mental health tool. As a brief, audio-guided online exercise, the intervention can be easily disseminated and self-administered by young women as a form of "psychological inoculation" or "digital first aid" immediately before or during social media use, empowering them with an in-the-moment strategy to self-regulate their emotional responses to potentially distressing content. From a public health perspective, this scalability makes the intervention a promising preventative strategy that can be deployed at a population level. For instance, educational institutions could integrate such brief mindfulness exercises into health and wellness curricula to equip students with proactive coping skills for navigating the digital world. Finally, this research has direct implications for the social media industry itself, as technology companies have a growing responsibility to foster healthier online environments. Platforms like Xiaohongshu could integrate features such as optional "mindful break" prompts that link to short, guided audio exercises like the one tested in this study, thereby playing a proactive role in mitigating the very harms their content may sometimes perpetuate and aligning their operations with user well-being.

7. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations that warrant attention. First, although the visual stimuli were designed to resemble typical Xiaohongshu posts and were presented remotely, the fixed 20-second viewing time for each image may not reflect participants' natural viewing behavior. This limitation, in turn, could diminish the ecological validity of the results. Second, the intervention involved only one brief mindfulness session, which prevented the assessment of the durability of any immediate benefits and the intervention’s potential to mitigate the long-term effects of exposure to idealized social media content. Furthermore, the absence of follow-up assessments limits understanding of whether the observed effects endure over time. Subsequent studies should include multiple follow-ups (e.g., at several weeks or months) to assess maintenance or amplification of protection and to evaluate whether repeated brief mindfulness sessions produce longer-lasting outcomes. Third, the sample consisted exclusively of female participants. Although women typically report higher levels of body dissatisfaction, men also experience significant body image concerns[

45,

46]. Future studies should evaluate brief mindfulness interventions in male samples, taking into account gender-specific manifestations of body dissatisfaction[

47].

8. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that, compared to a control condition, a brief ten-minute mindfulness meditation effectively mitigated the subsequent increases in state body dissatisfaction and negative mood induced by exposure to appearance-focused social media. Given the pervasive nature of idealized imagery on Xiaohongshu and similar social platforms, encouraging young women to engage in a brief mindfulness exercise before exposure could offer immediate protective benefits. It may also help improve resilience against appearance-related distress. Future research should explore how ongoing mindfulness practice can counteract the long-term negative impacts of repeated exposure to such content.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.X. ; methodology, Z.X.; software, Z.X.; validation, Z.X., Z.X; formal analysis, Z.X.; investigation, Z.X.; resources, Z.X.; data curation, Z.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.X.; writing—review and editing, Z.X., ZZ; visualization, Z.X., ZZ; supervision, X.X.,ZZ; funding acquisition, Z.X, ZZ. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by by the Talent Program of Beijing Jiaotong University (Grant No. 2023XKRCW013).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of School of Language and Communication Studies, Beijing Jiaotong University (reference number:BJTU2025060501); the date of this approval: 5 June 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author. The data presented in this study are available on request from the first author due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The researchers thank the participants who participated in this study

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jiménez-García, A.M.; Arias, N.; Hontanaya, E.P.; Sanz, A.; García-Velasco, O. Impact of body-positive social media content on body image perception. Journal of Eating Disorders 2025, 13, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleemans, M.; Daalmans, S.; Carbaat, I.; Anschütz, D. Picture perfect: The direct effect of manipulated Instagram photos on body image in adolescent girls. Media Psychology 2018, 21, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryde, S.; Prichard, I. TikTok on the clock but the #fitspo don’t stop: The impact of TikTok fitspiration videos on women’s body image concerns. Body Image 2022, 43, 244–252. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, W.; Sun, S.; Chen, J. Does influencers’ popularity actually matter? An experimental investigation of the effect of influencers on body satisfaction and mood among young Chinese females: The case of RED (Xiaohongshu). Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 12, 756010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forristal, L.; Xiaohongshu (RedNote), China’s answer to Instagram, hits No. 1 on the App Store as TikTok faces US shutdown. TechCrunch 2025, 13 January. Available online: https://techcrunch.com/2025/01/13/xiaohongshu-rednote-chinas-answer-to-instagram-hits-no-1-on-the-app-store-as-tiktok-faces-us-shutdown/ (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Zhong, Y. The influence of social media on body image disturbance induced by appearance anxiety in female college students. Psychiatria Danubina 2022, 34 (Suppl 2), 638–643. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, R.; Guest, E.; Ramsey-Wade, C.; Slater, A. A brief mindfulness meditation can ameliorate the effects of exposure to idealised social media images on self-esteem, mood, and body appreciation in young women: An online randomised controlled experiment. Body Image 2024, 49, 101702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upchurch, D.M.; Chyu, L. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among American women. Women’s Health Issues 2005, 15, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, S.R.; Lau, M.; Shapiro, S.; Carlson, L.; Anderson, N.D.; Carmody, J.; Segal, Z.V.; Abbey, S.; Speca, M.; Velting, D.; Devins, G. Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 2004, 11, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness. Mindfulness 2015, 6, 1481–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacalhau, S.P.; Orange, L.G.; Correia Junior, M.A.; Nunes, J.V.; Almeida, C.L.; Coriolano-Marinus, M.W. Mindfulness-based interventions and their relationships with body image and eating behavior in adolescents: A scoping review. Journal of Eating Disorders 2025, 13, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.; Malinowski, P. Meditation, mindfulness and cognitive flexibility. Consciousness and Cognition 2009, 18, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keng, S.-L.; Smoski, M.J.; Robins, C.J. Effects of mindfulness on psychological health: A review of empirical studies. Clinical Psychology Review 2011, 31, 1041–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, M.J.; Wade, T.D. Mindfulness training to facilitate positive body image and embodiment. In Handbook of Positive Body Image and Embodiment: Constructs, Protective Factors, and Interventions; Niva Piran; 2019; pp. 312–324.

- Delinsky, S.S.; Wilson, G.T. Mirror exposure for the treatment of body image disturbance. International Journal of Eating Disorders 2006, 39, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, C.E.; Benitez, L.; Kinsaul, J.; Apperson McVay, M.; Barbry, A.; Thibodeaux, A.; Copeland, A.L. Effects of brief mindfulness instructions on reactions to body image stimuli among female smokers: An experimental study. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 2013, 15, 376–384. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, M.J.; Wade, T.D. Mindfulness-based prevention for eating disorders: A school-based cluster randomized controlled study. International Journal of Eating Disorders 2015, 48, 1024–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M.; Richardson, B.; Lewis, V.; Linardon, J.; Mills, J.; Juknaitis, K.; Lewis, C.; Coulson, K.; O’Donnell, R.; Arulkadacham, L.; Ware, A. A randomized trial exploring mindfulness and gratitude exercises as eHealth-based micro-interventions for improving body satisfaction. Computers in Human Behavior 2019, 95, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, M.J.; Diedrichs, P.C. Examining the efficacy of video-based microinterventions for improving risk and protective factors for disordered eating among young adult women. International Journal of Eating Disorders 2021, 54, 708–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, S.M.; Chan, C.L.; Campbell, M.J.; Bond, C.M.; Hopewell, S.; Thabane, L.; Lancaster, G.A. CONSORT 2010 statement: Extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ 2016, 355, i5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.credamo.cc/#/.

- McComb, S.E.; Mills, J.S. Young women’s body image following upwards comparison to Instagram models: The role of physical appearance perfectionism and cognitive emotion regulation. Body Image 2021, 38, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, J.S.; Polivy, J.; Herman, C.P.; Tiggemann, M. Effects of exposure to thin media images: Evidence of self-enhancement among restrained eaters. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 2002, 28, 1687–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiggemann, M.; Polivy, J. Upward and downward: Social comparison processing of thin idealized media images. Psychology of Women Quarterly 2010, 34, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiggemann, M.; Slater, A. Thin ideals in music television: A source of social comparison and body dissatisfaction. International Journal of Eating Disorders 2004, 35, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, E.; Misener, K.; Libben, M. Exploring the impact of a gratitude-focused meditation on body dissatisfaction: Can a brief auditory gratitude intervention protect young women against exposure to the thin ideal? Body Image 2022, 41, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Vijver, F.J.; Leung, K. Methods and Data Analysis for Cross-Cultural Research; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Peking University Continuing Education. Mindfulness Intervention for Emotional Distress (MIED) Training Program [正念干预情绪困扰(MIED)培训项目]. 2024. Available online: https://peixun.pku.edu.cn/cms/recruit/index.htm?projectId=5728c70993b3446294c73fde90be4c3a (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Moffitt, R.L.; Neumann, D.L.; Williamson, S.P. Comparing the efficacy of a brief self-esteem and self-compassion intervention for state body dissatisfaction and self-improvement motivation. Body Image 2018, 27, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobin, K.C.; McComb, S.E.; Mills, J.S. Testing a self-compassion micro-intervention before appearance-focused social media use: Implications for body image. Body Image 2022, 40, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E.; Cheng, W.; Yuan, H.; Gao, X. Protecting young women’s body image from appearance-based social media exposure: A comparative study of self-compassion writing and mindful breathing interventions. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2025, 192, 112121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinberg, L.J.; Thompson, J.K. Body image and televised images of thinness and attractiveness: A controlled laboratory investigation. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 1995, 14, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardouly, J.; Diedrichs, P.C.; Vartanian, L.R.; Halliwell, E. Social comparisons on social media: The impact of Facebook on young women’s body image concerns and mood. Body Image 2015, 13, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinberg, L.J.; Thompson, J.K.; Stormer, S. Development and validation of the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire. International Journal of Eating Disorders 1995, 17, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopan, H.; Rajkumar, E.; Gopi, A.; Romate, J. Mindfulness-based interventions for body image dissatisfaction among clinical population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Health Psychology 2024, 29, 488–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keng, S.-L.; Ang, Q. Effects of mindfulness on negative affect, body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating urges. Mindfulness 2019, 10, 1779–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunaev, J. , Markey, C. H., & Brochu, P. M. (2018). An attitude of gratitude: The effects of body-focused gratitude on weight bias internalization and body image. Body Image, 25, 9–13.

- Wolfe, W.L.; Patterson, K. Comparison of a gratitude-based and cognitive restructuring intervention for body dissatisfaction and dysfunctional eating behavior in college women. Eating Disorders 2017, 25, 330–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, E.L.; Atkinson, M.J. Effects of decentering and non-judgement on body dissatisfaction and negative affect among young adult women. Mindfulness 2022, 13, 615–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiggemann, M.; Zaccardo, M. “Exercise to be fit, not skinny”: The effect of fitspiration imagery on women’s body image. Body Image 2015, 15, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, J.W.; Carson, K.M.; Gil, K.M.; Baucom, D.H. Mindfulness-based relationship enhancement. Behavior Therapy 2004, 35, 471–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beveren, L.; Roets, G.; Buysse, A.; Rutten, K. We all reflect, but why? A systematic review of the purposes of reflection in higher education in social and behavioral sciences. Educational Research Review 2018, 24, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, D.; Watanabe, A.; Osawa, K. Mindful attention awareness and cognitive defusion are indirectly associated with less PTSD-like symptoms via reduced maladaptive posttraumatic cognitions and avoidance coping. Current Psychology 2023, 42, 1182–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Antoni, F.; Feruglio, S.; Matiz, A.; Cantone, D.; Crescentini, C. Mindfulness meditation leads to increased dispositional mindfulness and interoceptive awareness linked to a reduced dissociative tendency. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation 2022, 23, 8–23. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, G.; Turner, H.; Bucks, R. The experience of body dissatisfaction in men. Body Image 2005, 2, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frederick, D.A.; Forbes, G.B.; Grigorian, K.E.; Jarcho, J.M. The UCLA Body Project I: Gender and ethnic differences in self-objectification and body satisfaction among 2,206 undergraduates. Sex Roles 2007, 57, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, D.; Mahlberg, J. Exploration of height dissatisfaction, muscle dissatisfaction, body ideals, and eating disorder symptoms in men. Journal of American College Health 2023, 71, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).