1. Introduction

Environmental auditing has become a pivotal instrument in advancing sustainable development, linking corporate governance with ecological accountability. In response to increasing stakeholder demands for demonstrable sustainability practices, such audits offer a systematic framework for assessing compliance, reducing environmental risks, and improving transparency. Beyond ensuring conformity with legal standards, environmental audits function as a strategic mechanism for building confidence among investors, consumers, and society at large (IAASB, 2024; INTOSAI WGEA, 2025).

Bulgaria and Moldova, two nations with distinct socio-economic landscapes and environmental challenges, offer unique perspectives on the role of environmental auditing in strengthening sustainability within corporate governance frameworks. Bulgaria’s integration of climate adaptation priorities into national planning highlights its commitment to sustainable practices (MoEW, 2019; UNFCCC, 2025). Meanwhile, Moldova’s efforts to modernize its environmental compliance assurance system underscore the importance of institutional capacity and stakeholder engagement in achieving ecological goals (OECD & EU4Environment, 2022).

Despite extensive research on environmental audits and management systems, several gaps remain. For example, there is a lack of empirical studies that establish a direct link between specific implementation methods and measurable improvements in environmental performance. In addition, inconsistencies in definitions and measurement scales across studies hinder comparative analyses. Future research should focus on developing standardized metrics and on digital, machine-readable disclosures that can improve comparability and auditability under the EU sustainability reporting framework (Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2023/2772, 2023; EFRAG, 2024; IAASB, 2024).

This paper aims to explore the comparative dynamics of environmental auditing in Bulgaria and Moldova, focusing on its impact on corporate governance and sustainability. By analyzing the regulatory frameworks, institutional mechanisms, and practical outcomes in these countries, this study seeks to provide valuable insights into how environmental audits can drive sustainable development while enhancing corporate accountability. The findings will contribute to the broader discourse on Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) practices, offering actionable recommendations for policymakers and businesses alike. The key results obtained show that the regulations implemented in Bulgaria and Moldova are promising. In other words, although the legal regulations of the countries are subject to different legislative provisions, their implementation methods are similar. However, it shows that Bulgaria has advanced control mechanisms in environmental control practices, while Moldova is successful in terms of regulations and policies.

Overall, the comparative focus on Bulgaria and Moldova illustrates how environmental auditing serves both as a compliance instrument and a transformative governance mechanism, bridging regulation, accountability, and sustainability innovation.

2. Literature Review

The conceptual framework and literature research prepared for corporate governance, sustainability and environmental auditing, based on the purpose of the research, have been explained above. When the literature studies are examined, it has been concluded that the studies that bring an integrated perspective on the subject are shallow. In addition, it has been determined that a significant portion of the studies are at the national level. Comparing Bulgaria and Moldova in this research will bring a different perspective to the literature. Especially, the bridge to be established between the sustainable corporate governance approach and environmental auditing will create an international awareness on the subject. In this respect, this research can be an important guide for researchers to make rich analyses in theory and practice. Based on the explanations made, the method of the research, the findings reached and the results obtained are explained in detail in the following headings.

Environmental auditing is increasingly positioned as a core instrument of sustainability governance that links corporate decision-making with transparent environmental performance and stakeholder accountability. Recent open-access syntheses show a marked shift from narrow compliance checks toward evidence-based assurance that supports investor decision usefulness and public trust (Pizzi et al., 2024). Within organizations, Environmental Management Systems (EMS) and the EU’s Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS) routinize audits and verified environmental statements; empirical EU evidence finds EMAS can deliver benefits beyond ISO 14001 by hard-wiring disclosure, legal compliance reviews, and continuous improvement loops (Matuszak-Flejszman & Paliwoda, 2022). At the field level, bibliometric reviews map a rapid expansion of ESG and environmental audit scholarship around themes of governance accountability, disclosure quality, and market outcomes, but also flag fragmentation across frameworks and methods—underscoring the need for convergence in assurance practice (Au et al., 2023; Bosi et al., 2022).

On the public-sector side, Government Environmental Auditing (GEA) has been theorized as a lever that tightens the policy cycle—linking design, enforcement, and outcomes. Open-access studies associate GEA with greener development trajectories and pollutant reductions, albeit with context-specific and sometimes lagged effects (Chai et al., 2022; Li et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023). These findings are highly relevant to transition economies like Bulgaria and Moldova, where audit capacity, digital data infrastructures, and multilevel coordination mediate whether audit insights translate into regulatory refinement and investment signals.

Standard-setting has moved decisively to strengthen credibility and comparability. In 2024 the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board issued ISSA 5000, a principles-based global benchmark for sustainability assurance designed to interoperate with jurisdictional regimes (IAASB, 2024). In Europe, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) mandates assurance of sustainability information, while the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) specify granular climate, pollution, and biodiversity disclosures (Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2023/2772, 2023). ESRS XBRL digital taxonomies operationalize machine-readable reporting and facilitate “audit-ready” data flows (EFRAG, 2024). Together, these developments signal an ecosystem shift: policy creates demand for reliable environmental information; assurance standards and digital taxonomies supply the tools for credible verification—conditions that favor the maturation of environmental auditing in both corporate and public domains.

Despite this progress, methodological hurdles remain. The most persistent is Scope 3 greenhouse-gas accounting: open-access evidence highlights data scarcity, supplier heterogeneity, double counting risks, and reliance on model-based estimates across value chains (Nguyen et al., 2023). These issues complicate assurance and often limit it to “limited” (rather than “reasonable”) conclusions. Beyond climate metrics, auditors frequently face uneven criteria for biodiversity or circularity claims, forward-looking statements, and qualitative assertions—areas where ESRS/ISSA guidance is still being operationalized in practice. Reviews therefore call for sector-specific protocols, primary-data pipelines, and digital traceability (e.g., tagged disclosures, provenance and audit trails) to lift assurance quality (EFRAG, 2024; IAASB, 2024; Pizzi et al., 2024).

For Bulgaria, EU membership has anchored environmental auditing in a dense regime of directives, inspectorate practices, and performance audits by public bodies, while policy work on climate adaptation has intensified since 2019 (Atanasova & Naydenov, 2025). Corporate-side audits (EMS/EMAS, compliance audits under the Industrial Emissions Directive) benefit from shared EU methods and benchmarks; public-sector audits (including Supreme Audit Institution work and EU oversight) add a second line of accountability. Remaining gaps flagged in open-access assessments include uneven sub-national implementation capacity and the need to embed audit findings systematically into policy iteration (Atanasova & Naydenov, 2025). For Moldova, an OECD/EU4Environment diagnostic documents progress in modernizing the environmental compliance-assurance system—risk-based planning, coordination, transparency—while noting constraints in inspection resources, monitoring fragmentation, and limited use of ex-post audits beyond permitting (OECD & EU4Environment, 2022). International cooperative audits and UNECE reviews have catalyzed reforms, but sustained capacity-building and digitization are still pivotal for scaling audit coverage and impact.

The literature also clarifies how audits influence corporate governance. External assurance and verified environmental statements strengthen board oversight, internal control over sustainability reporting, and stakeholder trust (Pizzi et al., 2024), particularly when aligned with enterprise risk management and strategy (ISSA 5000; ESRS governance disclosures). For transition economies, alignment with CSRD/ESRS and ISSA 5000 offers a practical bridge: (i) common concepts of materiality and metrics; (ii) explicit internal-control requirements; (iii) digital tagging that eases supervisory analytics. Empirical work on GEA suggests that when public audit institutions publish clear criteria and follow-up procedures, audit recommendations are more likely to trigger enforcement and programmatic change (Chai et al., 2022; Li et al., 2023).

Bringing these strands together, the comparative implications for Bulgaria and Moldova are threefold. First, standard convergence (ISSA 5000 with ESRS/CSRD) can compress variance in audit quality and enable cross-country benchmarking—useful for investors and regulators. Second, methodological upgrades are most urgent in hard-to-audit areas (Scope 3, biodiversity, circularity), where sector guidance, supplier engagement, and data technologies can unlock reasonable-assurance pathways. Third, capacity and digitization—risk-based planning, interoperable registries, XBRL-tagged reports, and open data—are decisive in converting audit evidence into governance improvements, with EU anchoring (Bulgaria) and EU-supported reforms (Moldova) representing different but complementary routes to impact.

To provide a concise foundation for the comparative analysis,

Table 1 summarizes open-access studies by theme, distilling key findings and unresolved issues that frame our research questions.

Taken together, the evidence map indicates three cross-cutting priorities for the comparative setting: (i) convergence of standards and digital auditability (ISSA 5000; ESRS/XBRL); (ii) methodological depth for hard-to-assure domains—especially Scope 3 and biodiversity—via sector guidance, primary-data pipelines, and traceability; and (iii) institutional capacity—risk-based planning, interoperable data systems, and systematic follow-up—to turn audit findings into policy and managerial change. These priorities frame the subsequent Bulgaria–Moldova analysis: EU anchoring enables faster implementation and benchmarking in Bulgaria, while capacity-building and digitalization are pivotal levers for convergence in Moldova.

3. Methodology

Building upon prior conceptual explorations of environmental control and auditing methods in Bulgaria and Moldova (EEA, 2024; UNECE, 2011, 2017), the present study advances the analysis by adopting a structured, comparative qualitative design. Earlier approaches have emphasized the role of environmental audits as control mechanisms verifying compliance with ecological and economic plans, including examination of financial documentation, authorizations, and operational procedures. While such frameworks provided valuable descriptive insights, this research extends them through a systematic methodological architecture grounded in qualitative content analysis and digital coding.

3.1. Research Design and Objectives

The study adopts a qualitative, comparative research design based on descriptive content analysis to explore how environmental auditing contributes to sustainability governance in Bulgaria and Moldova during the period 2020–2025. The design is guided by well-established methodological foundations (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005; Krippendorff, 2004; Weber, 1990; Zhang & Wildemuth, 2009) and seeks to identify the regulatory, thematic, and procedural dimensions of environmental auditing in the two national contexts.

Corporate governance refers to the structures and processes through which organizations create long-term value while protecting the interests of stakeholders. Within this logic, sustainable governance requires the integration of environmental considerations alongside economic and social goals. Environmental auditing plays a pivotal role in this integration: it supplies transparent, systematic assessments of policies and practices, links performance indicators to decision-making, and supports accountability and learning. In Europe, the rise of ESG and the SDGs has sharpened the role of audits as both compliance checks and strategic planning tools. Against this backdrop, Bulgaria and Moldova offer instructive contrasts. Bulgaria—embedded in the EU governance ecosystem—illustrates how audits inform program updates (waste, water, climate) and feed into broader reporting architectures. Moldova—operating with tighter capacity constraints—uses audits more diagnostically to surface infrastructure and enforcement gaps and to steer incremental reforms. This framing motivates our comparative analysis and underpins the S-B-P coding used in the study: Structural (legal-institutional and digital foundations), Substantive (priority themes and outcomes), and Procedural (methods, evidence, transparency, follow-up).

The research pursues three central questions:

RQ1: What are the structural features of the regulatory and institutional frameworks for environmental auditing in the two countries?

RQ2: What substantive themes and audit topics dominate reported practice?

RQ3: What procedural mechanisms (methods, follow-up, transparency) are used, and how do they differ across contexts?

These questions allow the study to move beyond descriptive comparison toward an interpretative understanding of how environmental audits shape and reflect governance quality in sustainability domains.

3.2. Scope and Data Sources

The scope of the study encompasses national regulations, audit reports, strategies, and professional guidelines addressing environmental auditing, sustainability assurance, or environmental management systems (EMS/EMAS) in Bulgaria and Moldova. The temporal boundary (2020–2025) was selected to capture the post-COVID-19 regulatory evolution and the period of active harmonization with European Union environmental policies.

The data consist exclusively of secondary sources drawn from official and publicly accessible repositories:

national legal databases;

ministerial and agency portals (environment, finance, energy);

websites of the Supreme Audit Institutions; and

professional or academic publications.

Documents outside the defined period or lacking explicit relevance to environmental auditing were excluded following a two-step screening of titles and full texts. The unit of analysis is the document (law, strategy, audit report, guideline, or policy paper).

3.3. Coding Framework and Analytical Dimensions

To structure the qualitative analysis, a codebook was iteratively developed and organized around three analytical dimensions corresponding to the research questions:

Structural Dimension – encompassing legal frameworks, institutional mandates, and digital infrastructures supporting environmental auditing;

Substantive Dimension – capturing audit objectives, topics, and findings related to sustainability outcomes;

Procedural Dimension – addressing audit methods, data collection, transparency, follow-up mechanisms, and reporting practices.

All coding and data management were performed in QDAcity, enabling systematic tagging, visualization, and cross-referencing of analytic categories. We used a three-family codebook aligned with the S–B–P scheme—S (Structural), B (Substantive), and P (Procedural)—and color-coded the families for consistency (blue, orange, green). The coding strategy combined deductive codes derived from prior literature and audit frameworks with inductive themes emerging from country-specific documents. As coding progressed, we refined code definitions to maintain conceptual coherence across both national datasets. Individual codes are numbered sequentially (e.g., S1–S5, B1–B5, P1–P5). “Representative codes” in the tables denote the most frequent and/or salient codes per theme identified in QDAcity. Following the completion of the coding process, all coded data were exported from QDAcity and subsequently processed and visualized using RStudio (version 4.4). This step enabled the creation of comparative heatmaps and descriptive frequency matrices to illustrate the relative intensity and maturity of themes across the supranational, Bulgarian, and Moldovan document corpora. Document IDs (e.g., SU01–SU14) correspond to the supra-level sources listed in the Document Inventory (

Appendix B,

Table A2); full code definitions appear in the Codebook (

Appendix A,

Table A1).

3.4. Reliability and Validity

To enhance reliability and transparency, all coded documents were subjected to multiple review cycles. Cross-checks between codes and original texts ensured internal consistency and minimized subjectivity. Coding decisions, revisions, and analytical memos were documented within QDAcity, forming a complete audit trail of the research process.

Methodological triangulation was achieved by integrating legal, strategic, and audit-based sources, thereby reinforcing interpretative validity. The approach aligns with recommendations by Krippendorff (2004) and Zhang & Wildemuth (2009) for maintaining analytic rigor in qualitative content analysis (Krippendorff, 2004; Zhang & Wildemuth, 2009).

3.5. Analytical Procedure

The coded data were synthesized into comparative country profiles and tabular summaries illustrating the three analytical dimensions. This synthesis enabled the identification of key similarities and divergences in audit scope, institutional design, and methodological practices between Bulgaria and Moldova.

Findings were interpreted in light of existing frameworks for environmental governance and sustainability auditing, linking national audit practices to broader international standards such as the EU Green Deal and the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). To ensure analytical transparency and reproducibility, the coded data were processed through RStudio using a customized script that transformed QDAcity exports into normalized code matrices. These matrices supported both tabular summaries and graphical visualizations (heatmaps), which are presented in

Section 4. The integration of RStudio as a visualization tool complements the qualitative interpretation by offering an additional layer of pattern recognition and comparative depth.

3.6. Ethical Considerations and Limitations

Ethical approval was not required, as the study relies exclusively on publicly available documents and does not involve human participants.

The main limitation concerns the dependence on reported rather than raw data. Differences in reporting depth and document consistency across sources may constrain direct comparability. These limitations were mitigated through transparent coding, cross-validation of sources, and reliance on clearly defined analytical categories.

3.7. Contribution of the Methodological Approach

By integrating the traditional understanding of environmental auditing as a state control mechanism with a modern, comparative content-analytic methodology, this research bridges descriptive and analytical paradigms. The incorporation of QDAcity software ensured methodological traceability and replicability, while the focus on structural, substantive, and procedural dimensions allows for a nuanced assessment of how environmental auditing supports sustainability governance in Bulgaria and Moldova. The finalized coding framework thus provides a solid foundation for the subsequent analysis of results and thematic patterns. The combined use of QDAcity for qualitative data management and RStudio for quantitative visualization enhances the methodological novelty of the study by linking transparent coding workflows with replicable, data-driven representation of environmental auditing patterns.

4. Environmental Auditing and Corporate Governance: A Comparative Analysis of Moldova and Bulgaria in Strengthening Sustainability

Corporate governance encompasses the structures and processes through which organizations create long-term value and protect the interests of stakeholders. Within this logic, sustainable governance integrates environmental objectives alongside economic and social ones, supported by international standards and good practices (OECD, 2023). The expansion of ESG has strengthened the role of verifiable environmental and sustainability information as a bridge between policy intentions and measurable outcomes—both in capital markets and in the public sector (Friede et al., 2015; Kotsantonis et al., 2016). In Europe, this agenda is framed by the EU Green Deal and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which require transparency, comparable indicators, and evidence-based policy adjustment (European Commission, 2019; United Nations, 2015).

Against this backdrop, environmental auditing functions both as a compliance mechanism and as a tool for strategic learning: it verifies legal obligations, identifies implementation gaps, and channels insights into program updates and investment prioritization. Bulgaria—embedded in the EU’s regulatory and reporting architectures—demonstrates more institutionalized audit cycles that feed sectoral strategies and digital disclosure. Moldova—working with more limited resources—uses audits more diagnostically to address enforcement and infrastructure gaps and to steer incremental reforms. The remainder of

Section 4 presents results at three levels—SUPRA (EU/Europe), Moldova, and Bulgaria—across structural, substantive, and procedural dimensions to enable transparent comparison.

4.1. Results (SUPRA Level): European Framework for Environmental Auditing and Assurance

As a result of the qualitative content analysis in QDAcity and the application of the S–B–P scheme (Structural–Substantive–Procedural), the three analytical dimensions and the scope of the document corpus at the supranational (SUPRA) level were delineated.

Table 2 presents the coding framework and illustrative sources.

Based on this framework,

Table 3 lists the leading themes and their representative, together with the distributed at the SUPRA level documents in which they are most prominently observed.

The supra-level analysis integrates fourteen documents (SU01–SU14) spanning EU regulations, EFRAG guidance, IAASB assurance standards, and EEA reports. Structural: EU instruments such as Regulation (EU) 2023/2772 (SU01) and EFRAG’s XBRL taxonomy (SU02–SU03) embed sustainability assurance within the corporate reporting ecosystem, defining mandatory disclosure principles and a digital infrastructure interoperable with ESMA’s Single Electronic Format; water-resilience guidance (SU13) further links environmental and financial datasets. Substantive: EEA thematic and country reports (SU08–SU12) prioritize domains like air, water, and waste prevention, emphasizing indicators, comparability, and longitudinal progress (e.g., Tracking Waste Prevention Progress, SU11), signalling a move from pure compliance checks toward effectiveness evaluation. Procedural: IAASB ISSA 5000 (SU04) and its implementation guide (SU05), together with INTOSAI WGEA materials (SU06–SU07) and the EEA EMAS statement (SU14), codify planning, evidence collection, stakeholder engagement, and follow-up. Overall, the coding shows convergence toward a harmonized European assurance landscape where legal frameworks (Structural), thematic content (Substantive), and assurance methodologies (Procedural) interact to strengthen environmental governance. These results serve as a benchmark for the national-level comparisons of Bulgaria and Moldova.

4.2. Results (Moldova Level): National Architecture of Environmental Auditing and Assurance

As a result of the qualitative content analysis in QDAcity and the application of the S–B–P scheme (Structural–Substantive–Procedural), the analytical dimensions and the scope of the Moldova-level corpus (MD01–MD10) were delineated.

Table 4 presents the coding framework and illustrative sources.

Based on this framework,

Table 5 summarizes the leading themes, their representative codes, and the Moldova documents in which these themes are most prominent.

The Moldova set (MD01–MD10) evidences a consolidating governance architecture. Structurally, the Environmental Protection Law, the “Moldova 2030” strategy, and the Low-Emission Development Programme to 2030 establish the policy backbone, while newer tools (e.g., Environmental Certificates 2026) aim to hard-wire responsibility and improve compliance transparency. Substantively, national assessments and sector studies prioritize measurable indicators in waste, water, and environmental health; feasibility analyses highlight infrastructure and capacity gaps that shape implementation pathways. Procedurally, the Court of Accounts’ INTOSAI-aligned methodology, applied audits in water/sanitation, and UNFCCC BTR1 reporting mark progress toward evidence-based assurance and international transparency. Overall, Moldova’s ecosystem is evolving from a predominantly diagnostic, capacity-building focus toward more standardized follow-up and reporting—mirroring European practice while adapting to domestic resource constraints.

4.3. Results (Bulgaria Level): National Architecture of Environmental Auditing and Assurance

As a result of the qualitative content analysis in QDAcity and the application of the S–B–P scheme (Structural–Substantive–Procedural), the analytical dimensions and the scope of the Bulgaria corpus (BG01–BG10) were delineated.

Table 6 presents the coding framework and illustrative sources.

Based on this framework,

Table 7 summarizes the leading themes, their representative codes, and the Bulgaria documents in which these themes are most prominent.

The Bulgaria set (BG01–BG10) points to a mature, EU-anchored governance architecture. Structurally, the Accounting Act and Public Enterprises Act establish the link between financial and non-financial accountability, while the OP “Environment” Annual Implementation Report and the Aarhus Convention Implementation Report operationalize transparency and acquis alignment—though coordination frictions across implementing bodies persist. Substantively, sector strategies and audits span waste, water, air, biodiversity, and climate: the National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy 2023–2030 operationalizes resilience planning; the EUROSAI Cooperative Audit on Plastic Waste surfaces circular-economy challenges; and EMAS/ISO adoption signals enterprise-level environmental management with verifiable outputs. Procedurally, NAO manuals and the performance audit on water resources management evidence risk-based planning, structured evidence collection, and documented follow-up, while the EMAS registry provides verification, traceability, and EU-level data interoperability. Overall, Bulgaria’s ecosystem is transitioning from compliance-centered controls to performance-oriented assurance and integrated reporting—largely aligned with European practice, with ongoing work on cross-sector harmonization and fuller linkage to core financial accountability systems.

4.4. Cross-Country Synthesis (BG vs. MD)

The cross-country synthesis highlights both convergence and divergence in how Bulgaria and Moldova deploy environmental auditing to strengthen sustainability governance. Structurally, Bulgaria operates within an EU-anchored legal–institutional framework that couples environmental and non-financial reporting and enables multi-level oversight; Moldova’s architecture is consolidating, sequencing approximation to EU standards while piloting tools that hard-wire accountability. Substantively, both prioritize waste, water and air, but Bulgaria reports more outcome-oriented objectives (e.g., adaptation, resource efficiency), whereas Moldova’s outputs remain diagnostic, targeting enforcement and infrastructure gaps. Procedurally, Bulgaria’s SAI and inspectorates document standardized planning, follow-up and public disclosure, complemented by EMAS/ISO practices; Moldova records progress via INTOSAI-aligned methods and UNFCCC BTR1 transparency, with capacity building still pivotal.

A brief temporal scan (2020–2025) confirms these trajectories: in Bulgaria, audit insights steadily informed waste and water program updates, supported wider EMS/EMAS uptake, and underpinned climate-policy roll-out—yielding measurable gains in compliance and reporting by 2025. In Moldova, audits sequenced reforms from water/waste bottlenecks to pilot climate actions and stronger follow-up under sustained international support. Across both countries, three conditions consistently raise impact: continuity of audit cycles, integrated/high-quality data, and formal tracking of recommendations. Overall, environmental auditing acts as compliance-plus in Bulgaria and a diagnostic-to-standardization pathway in Moldova, with digital auditability and stakeholder engagement as shared levers for future gains.

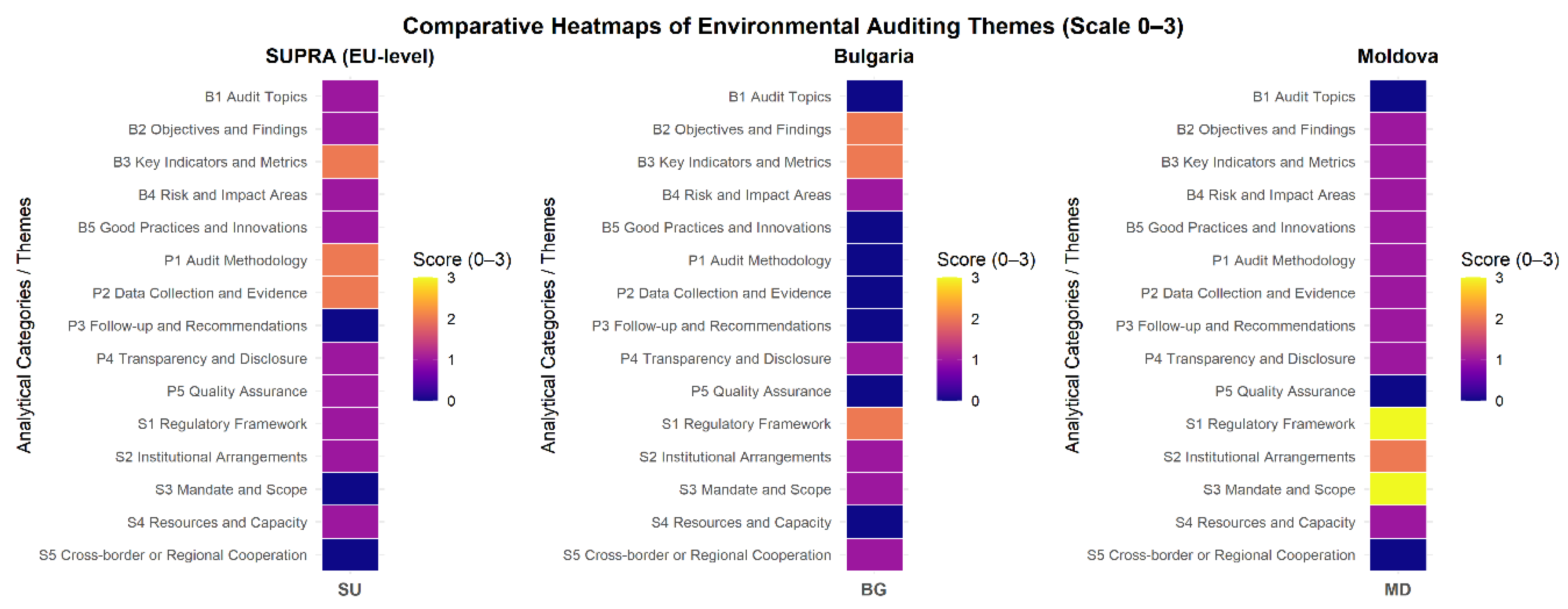

Figure 3 contents visual comparison with R of structural, substantive, and procedural audit themes across the supranational (EU-level), Bulgaria, and Moldova contexts, based on QDAcity-coded data (Scale 0–3).

Figure 1 presents a comparative visualization that consolidates the results of the QDAcity-coded corpus (SU01–SU14; BG01–BG10; MD01–MD10) across the three analytical dimensions—Structural (S1–S5), Substantive (B1–B5), and Procedural (P1–P5). The heatmaps were generated in R (version 4.4) using processed QDAcity export files, which enabled systematic comparison of coding frequencies and thematic intensities across countries. Scores ranging from 0 to 3 reflect the relative prominence and maturity of each theme within the supranational and national frameworks. The supranational (EU-level) layer illustrates regulatory convergence and methodological standardization, integrating ISSA 5000, ESRS, and INTOSAI WGEA guidance. Bulgaria demonstrates strong procedural alignment, well-developed follow-up mechanisms, and performance-oriented assurance practices, positioning it close to the European compliance benchmark. Moldova, in contrast, shows structural innovation and ongoing legislative modernization, though implementation maturity remains limited. The visual contrast thus highlights differentiated yet converging trajectories toward integrated, digitalized, and evidence-based environmental governance.

5. Discussion: Audit-Driven Governance in Bulgaria and Moldova

5.1. Audit-Driven Governance Pathways: Bulgaria, Moldova, and Cross-Cutting Implications

Bulgaria’s EU membership hard-wires environmental auditing into a multi-level governance system where directives, funding programmes, and reporting duties reinforce one another. Audit cycles run by the Supreme Audit Institution and the environmental inspectorates feed directly into programme adjustments (waste, water) and into the rollout of climate policy (e.g., the 2024–2030 mitigation and adaptation instruments). EMAS/ISO practices in enterprises add a verified management layer that improves data quality and auditability. In practice, this has produced: (i) clearer performance targets and indicators; (ii) stronger follow-up with time-bound recommendations; and (iii) more systematic disclosure (Aarhus/SEA/EIA channels), inviting stakeholder scrutiny and improving policy coherence across ministries and the EU level. Net effect: auditing functions as compliance-plus—a proactive steering tool aligning regulatory refinement, investment prioritisation, and measurable outcomes.

Moldova follows a more incremental trajectory typical of a transition administration with constrained resources. Audits—by line agencies and the Court of Accounts—have exposed gaps in waste infrastructure, water governance, and enforcement, progressively informing the National Environmental Action Programme (2020–2025), subsequent sector plans, and the Environmental Strategy 2024–2030. INTOSAI-aligned methodologies and UNFCCC BTR1 reporting add credibility and connect domestic assurance to international transparency regimes. UNECE- and EU-supported initiatives provide methodological guidance, benchmarking, and access to finance, translating findings into pilot actions (e.g., circular-economy measures, risk-based inspections) and legal approximation. Impact pattern: diagnostic-to-standardisation—audits catalyse capacity building, the sequencing of reforms, and the gradual tightening of follow-up and disclosure.

Across both countries, three conditions consistently magnify audit impact: (1) continuity of audit cycles with formal tracking of recommendations; (2) integrated, digital data systems enabling comparable indicators and machine-readable reporting (EMAS/ISO linkages; readiness for EU-style XBRL/ESRS in BG; PRTR and e-register upgrades in MD); and (3) stakeholder participation and transparency that convert findings into social accountability. Where these are mature (Bulgaria), audits inform strategy updates, EU programme management, and targeted spending. Where they are emerging (Moldova), audits remain the key lever for institutional learning, international cooperation, and convergence with European standards.

Building on these findings, we distil targeted recommendations for each country and cross-cutting actions (

Section 5.2).

5.2. Policy Recommendations

5.2.1. Bulgaria: Targeted Actions for “Compliance-Plus” Policy Steering

To translate the Bulgarian diagnosis into concrete governance gains, we outline pragmatic actions that embed audit findings into day-to-day management, strengthen risk targeting, and make data and coordination work for outcomes.

Institutionalise follow-up tracking. Establish a public, regularly updated dashboard that lists every audit recommendation with the responsible institution, a clear deadline, current implementation status, and an explicit link to the relevant budget programme or project so that citizens and decision-makers can track delivery end-to-end;

Deepen risk-based oversight. Align annual inspection plans with national climate- and water-risk maps and prioritise facilities using combined criteria—such as reported emissions, incident history, citizen complaints, and past non-compliance—so that supervisory resources are concentrated where environmental and health risks are greatest;

Tighten data pipelines. Interlink electronic permitting systems, the national Pollutant Release and Transfer Register, and water/waste registries with enterprise data from the Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS) and the International Organization for Standardization environmental management standard (ISO 14001), and require machine-readable exports to enable analysis, comparison, and reuse across agencies;

Address hard-to-assure areas. Develop sector-specific protocols for value-chain (Scope 3) emissions, circular-economy performance, and biodiversity impacts, and pilot external “reasonable assurance” engagements on a small set of priority indicators to build methods, confidence, and replicable practice;

Close coordination gaps. Create an interministerial “Audit-to-Policy” forum—bringing together the Ministry of Environment, the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Regional Development, and the Supreme Audit Institution—that meets annually to convert audit findings into updated programmes, targeted investment choices, and concrete milestones aligned with European Union and cohesion-funding requirements.

5.2.2. Moldova: From Diagnostic Audits to Standardised Assurance

To convert Moldova’s audit-driven diagnostics into durable governance improvements, the actions below focus on locking in a full audit cycle, strengthening digital evidence, building technical capacity, leveraging international transparency regimes, and linking recommendations to finance so that findings translate into measurable results.

Codify the audit cycle. Establish in secondary legislation a minimum, repeatable sequence—planning, audit execution, issuance of recommendations, and formal follow-up—and require a single, consolidated annual implementation report that lists each recommendation, its responsible authority, milestones, and completion status to ensure continuity and accountability;

Upgrade digital auditability. Accelerate the development of the national Pollutant Release and Transfer Register and integrate electronic permitting systems, inspection protocols, and citizen alerts submitted via the EcoAlert application into one unified, regularly updated risk index that prioritises inspections and enforcement where potential impacts and non-compliance risks are highest;

Build capacity where it counts. Direct technical assistance toward (i) instruments of the waste economy such as extended producer responsibility and the roll-out of regional landfills and sorting facilities, (ii) continuous and quality-controlled surface and groundwater monitoring, and (iii) standardised sampling procedures and laboratory quality assurance/quality control so that audit evidence is robust and defensible;

Leverage international transparency. Use the first Biennial Transparency Report under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change as a template for methods, verification steps, and public disclosure in adjacent themes such as waste management and air quality, and embed relevant guidance from the International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions into the Court of Accounts’ performance-audit methodology;

Move from pilots to scale through financing. Link priority audit recommendations to concrete project pipelines supported by initiatives such as EU4Environment and international financial institutions, and define a small set of “audit indicators” that function as disbursement or phase-gate conditions so that funding is explicitly tied to the closure of audit findings.

5.2.3. Cross-Cutting: Turning Audit Evidence into Outcomes

Including a short, shared set of actions helps the paper move from country-specific diagnostics to implementable steps that apply across institutional contexts. The points below translate the empirical findings into practical levers that Bulgaria and Moldova can deploy in parallel—irrespective of different starting capacities.

Ensure continuity of the audit cycle. Establish multi-year audit programmes with scheduled re-checks every 12–18 months for the most critical recommendations, assign a single responsible authority for each item, and publish timelines and completion statuses so that follow-up is predictable and accountable;

Make data usable across systems. Require machine-readable, open formats and common identifiers for facilities and permits, and expose open application programming interfaces that interlink electronic permitting, the Pollutant Release and Transfer Register (PRTR), water and waste registries, and enterprise environmental management data from the Eco-Management and Audit Scheme and ISO 14001, so that indicators are comparable and evidence is verifiable;

Engage stakeholders in follow-up. Standardise public releases to include a plain-language executive summary and a technical annex, define participation windows for comments, and invite non-governmental organisations and academic experts to periodic review sessions focused on the status of implementing audit recommendations;

Link recommendations to budgets. Map every major audit recommendation to an explicit budget line at the level of programme, measure, or project, and use results-based conditions in domestic and external financing so that funds are disbursed when implementation milestones are met;

Share what works and scale it. Organise Bulgaria–Moldova peer-learning sprints on themes such as risk-based inspections, roll-out of the Eco-Management and Audit Scheme, and operation of the Pollutant Release and Transfer Register, and produce short, replicable “how-to” protocols with responsible owners and timelines that are published on ministry portals and revisited annually.

6. Limitations and Future Research

This study relies exclusively on secondary, document-based evidence; as such, findings reflect the depth, coverage, and consistency of publicly available sources rather than raw administrative data. Differences in reporting practices across Bulgaria and Moldova may limit perfect comparability, and some policy changes initiated in 2025 may not yet be observable in outcomes. While the S–B–P coding scheme and QDAcity audit trail enhance transparency and reliability, qualitative judgments remain inherent to content analysis. Future research should (i) triangulate these results with primary data from inspectorates, permit registries, and facility-level monitoring; (ii) incorporate enterprise-level surveys on EMAS/ISO adoption and audit follow-up; (iii) test causal pathways by linking audit recommendations to budget execution and performance indicators; and (iv) extend the comparison to peer countries in the region to assess transferability and scalability of the proposed “compliance-plus” model.

7. Conclusions

Environmental auditing in Bulgaria and Moldova converges on method portfolios but diverges in institutional depth and digital auditability. Within the EU-anchored system, Bulgaria uses audits as a compliance-plus steering tool that informs program design, budget targeting, and transparent disclosure. Moldova follows a diagnostic-to-standardisation pathway in which audits catalyse capacity building, legal approximation, and incremental tightening of follow-up. Across both contexts, three levers consistently raise impact—continuous audit cycles with tracked recommendations, interoperable digital data systems, and structured stakeholder engagement. By organising results under a Structural–Substantive–Procedural lens and maintaining a QDAcity audit trail, the paper offers a replicable template for assessing how audits translate into governance outcomes and where policy investments should be prioritised.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.D..; methodology, L.D. and R.K.-H.; software, R.K.-H..; validation, L.D., B.K. and E.G.; formal analysis, L.D.; investigation, B.K.; resources, E.G.; data curation, R.K.-H.; writing—original draft preparation, L.D., B.K., E.G., and R. K.-H.; writing—review and editing, B.K. and E.G.; visualization, R.K.-H.; supervision, L.D.; project administration, L.D.; funding acquisition B.K.,E.G. and R.K.-H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are publicly available. All documents analyzed were retrieved from official online repositories of the European Union, national governmental portals of Bulgaria and Moldova, and institutional websites such as EEA, EFRAG, INTOSAI WGEA, and national audit authorities. The processed datasets used for qualitative coding and visualization (exported from QDAcity and analyzed in RStudio) are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

S–B–P Codebook (Categories, Codes, and Definitions).

Table A1.

S–B–P Codebook (Categories, Codes, and Definitions).

| Category |

Code |

Name |

Definition |

| Structural |

S1 |

Regulatory Framework |

Covers all binding or semi-binding regulatory instruments — laws, directives, regulations, and policy decisions — that establish the mandate, scope, and institutional responsibilities of environmental auditing and reporting. It reflects the structural governance layer underpinning sustainability assurance systems. |

| S2 |

Institutional Arrangements |

Covers organizational arrangements and governance mechanisms that define roles, mandates, and cooperation models between institutions responsible for environmental auditing, sustainability assurance, and reporting supervision. |

| S3 |

Mandate and Scope |

Covers provisions that establish the authority, scope, and subject matter of environmental audits, including who conducts them, what domains are examined, and the degree of autonomy granted to auditors or assurance providers. |

| S4 |

Resources and Capacity |

Refers to the availability and quality of institutional resources — financial, human, and technological — required to conduct and sustain environmental auditing, monitoring, and assurance activities. |

| S5 |

Cross-border or Regional Cooperation |

Refers to institutionalized cooperation, partnerships, and joint audit initiatives across borders or within regional frameworks. |

| Substantive |

B1 |

Audit Topics |

Focuses on the environmental themes and issues addressed by audit institutions or sustainability assurance bodies. |

| B2 |

Objectives and Findings |

Refers to the purpose, evaluation criteria, and key results or conclusions of environmental audit activities. |

| B3 |

Key Indicators and Metrics |

Focuses on the metrics, indicators, and data tools applied to monitor environmental or sustainability outcomes within audit processes. |

| B4 |

Risk and Impact Areas |

Covers environmental and sustainability risks, as well as the actual or potential impacts identified through audits, inspections, or reporting mechanisms. |

| B5 |

Good Practices and Innovations |

Focuses on identified good practices, innovative approaches, and lessons learned that enhance the effectiveness and impact of environmental audits and sustainability policies. |

| Procedural |

P1 |

Audit Methodology |

Refers to the design, techniques, and analytical tools used in conducting environmental audits and sustainability assurance engagements. |

| P2 |

Data Collection and Evidence |

Refers to methods of obtaining, validating, and managing information and empirical evidence used in environmental or sustainability audits. |

| P3 |

Follow-up and Recommendations |

Refers to actions taken after audit completion to ensure that recommendations are addressed and improvements are achieved. |

| P4 |

Transparency and Disclosure |

Refers to the disclosure and communication of audit results and related information to external audiences. |

| P5 |

Quality Assurance |

Refers to procedures and institutional mechanisms that safeguard the reliability, validity, and professional integrity of environmental audits. |

Appendix B

Table A2.

SUPRA (EU/Europe) Document Inventory (SU01–SU14).

Table A2.

SUPRA (EU/Europe) Document Inventory (SU01–SU14).

| ID |

Description |

Type |

Tags |

| SU01 |

Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2023/2772 of 31 July 2023 supplementing Directive (EU) 2013/34 as regards sustainability reporting standards (ESRS) |

EU Law / Legal Framework |

S1 Regulatory Framework |

| SU02 |

EFRAG ESRS Set 1 XBRL Taxonomy (Press/Package PDF), 30 August 2024 |

Taxonomy / Digital Reporting Framework |

S4 Resources and Capacity

P2 Data Collection and Evidence |

| SU03 |

EFRAG ESRS XBRL Taxonomy – Project page (Concluded), 2024 |

Web Summary / EU Project |

S2 Institutional Arrangements |

| SU04 |

International Standard on Sustainability Assurance (ISSA) 5000 — General Requirements for Sustainability Assurance Engagements |

Assurance Standard |

P1 Audit Methodology |

| SU05 |

ISSA 5000 Implementation Guide, IAASB, 2025 |

Guidance / Implementation Manual |

P2 Data Collection and Evidence |

| SU06 |

INTOSAI WGEA — Guidance on Environmental and Climate Auditing, 2025 |

Guidance / Audit Manual |

P1 Audit Methodology |

| SU07 |

INTOSAI WGEA — Publications: Studies & Guidelines Portal, 2025 |

Web Portal / Reference Source |

P4 Transparency and Disclosure |

| SU08 |

ETC/HE Report 2024-5: Status Report of Air Quality in Europe for Year 2023 (EEA/ETC-HE), 2024 |

EEA/ETC Report |

B3 Key Indicators and Metrics |

| SU09 |

EEA Briefing: Europe’s Air Quality Status 2023 |

Briefing / Policy Summary |

B4 Risk and Impact Areas |

| SU10 |

EEA Bathing Water Country Fact Sheets 2024 |

Country Factsheets / Data Publication |

B1 Audit Topics |

| SU11 |

EEA Report 02/2023 — Tracking Waste Prevention Progress |

EEA Report / Circular Economy |

B2 Objectives and Findings |

| SU12 |

EEA Waste Prevention Country Fact Sheets 2023 |

Country Factsheets |

B3 Key Indicators and Metrics |

| SU13 |

EEA Briefing: Water Savings for a Water-Resilient Europe, 2025 |

Briefing / Policy |

B5 Good Practices and Innovations |

| SU14 |

EEA Environmental Statement 2023 (EMAS) |

EMAS Statement / Verified Disclosure |

P5 Quality Assurance |

Table A3.

Moldova Document Inventory (MD01–MD10).

Table A3.

Moldova Document Inventory (MD01–MD10).

| ID |

Description |

Type |

Tags |

| MD01 |

Law on Environmental Protection No. 1515-XII (1993, consolidated 2014, amended 2023) |

National Law / Legal Framework |

S1 Regulatory Framework |

| MD02 |

Court of Accounts of the Republic of Moldova – Environmental Audit Methodology (2022) |

Methodological Guideline |

S2 Institutional Arrangements

P1 Audit Methodology

P3 Follow-up and Recommendations |

| MD03 |

National Development Strategy “Moldova Europeană 2030” (2022) |

Policy / Strategy |

S3 Mandate and Scope |

| MD04 |

National Assessment Report for Moldova (2023) |

National Environmental Assessment Report |

B4 Risk and Impact Areas |

| MD05 |

Project Feasibility Assessment – Moldova Solid Waste Project (Final Report) of the Ministry of Environment of the Republic of Moldova / Consultant COWI A/S (2022) |

Feasibility Study / Project Report |

S2 Institutional Arrangements

B3 Key Indicators and Metrics |

| MD06 |

Low-Emission Development Programme of the Republic of Moldova until 2030 (2023) |

Government Decision / Climate Programme |

S1 Regulatory Framework

S3 Mandate and Scope |

| MD07 |

The Environmental Compliance Assurance System in the Republic of Moldova: Current Situation and Recommendations (2022) |

Assessment Report / Compliance Assurance Study |

S1 Regulatory Framework

P2 Data Collection and Evidence |

| MD08 |

National Water Supply and Sanitation Strategy 2014–2030 (2022) |

National Strategy / Policy Framework |

S3 Mandate and Scope |

| MD09 |

Republic of Moldova’s First Biennial Transparency Report (BTR1) under the Paris Agreement (2024) |

Climate Transparency Report / National Submission |

B2 Objectives and Findings

P4 Transparency and Disclosure |

| MD10 |

What Are Environmental Certificates in Moldova and Why Moldovan Environmental Regulations 2026 Demand Them? (2025) |

Media / Analytical Article |

S4 Resources and Capacity

B5 Good Practices and Innovations |

Table A4.

Bulgaria Document Inventory (BG01–BG10).

Table A4.

Bulgaria Document Inventory (BG01–BG10).

| ID |

Description |

Type |

Tags |

| BG01 |

Accounting Act (Закoн за счетoвoдствoтo, пoсл. изм. ДВ 2025) |

National Law / Legal Framework |

S1 Regulatory Framework |

| BG02 |

Environmental Protection Act (Закoн за oпазване на oкoлната среда, ДВ 2024) |

National Law / Legal Framework |

S1 Regulatory Framework |

| BG03 |

Public Enterprises Act and its Implementation Rules (2019–2020) |

National Law / Corporate Governance Framework |

S2 Institutional Arrangements |

| BG04 |

National Strategy for the Environment 2020–2030 |

Policy / Strategy |

B2 Objectives and Findings |

| BG05 |

Operational Programme “Environment” – Annual Implementation Report 2023 |

Programme Report |

B3 Key Indicators and Metrics |

| BG06 |

Implementation Report Format for the Aarhus Convention 2021 (MoEW) |

Implementation Report |

S3 Mandate and Scope |

| BG07 |

National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy and Action Plan 2023–2030 |

Climate Strategy / Policy Plan |

B2 Objectives and Findings |

| BG08 |

Supreme Audit Institution (NAO) – Joint Report on Plastic Waste Management (2022) |

Performance Audit / Thematic Audit |

S5 Cross-border or Regional Cooperation

B3 Key Indicators and Metrics |

| BG09 |

Audit “Protection, Restoration and Sustainable Management of Forests” (2021–2023) |

Performance Audit |

B4 Risk and Impact Areas |

| BG10 |

Executive Environment Agency – EMAS Register 2024 |

Registry / Database |

P4 Transparency and Disclosure |

References

-

2023 waste prevention country fact sheets. (n.d.). [Folder]. European Environment Agency. Retrieved October 19, 2025, from https://www.eea.europa.eu/themes/waste/waste-prevention/countries/2023-waste-prevention-country-fact-sheets.

- Atanasova, A., & Naydenov, K. (2025). Perceptions of the Barriers to the Implementation of a Successful Climate Change Policy in Bulgaria. Climate, 13(2), 40. [CrossRef]

- Au, A. K. M., Yang, Y.-F., Wang, H., Chen, R.-H., & Zheng, L. J. (2023). Mapping the Landscape of ESG Strategies: A Bibliometric Review and Recommendations for Future Research. Sustainability, 15(24), 16592. [CrossRef]

-

Bathing water country fact sheets 2024. (2025, June 20). https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/topics/in-depth/bathing-water/state-of-bathing-water/bathing-water-country-factsheets-2024.

- Bosi, M. K., Lajuni, N., Wellfren, A. C., & Lim, T. S. (2022). Sustainability Reporting through Environmental, Social, and Governance: A Bibliometric Review. Sustainability, 14(19), 12071. [CrossRef]

- Chai, K.-C., Zhu, J., Lan, H.-R., Lu, Y., Liu, R.-Y., & Liu, P. (2022). Effectiveness of government environmental auditing in the industrial manufacturing structure upgradation. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 10, 995310. [CrossRef]

- Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2023/2772 on European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS), European Commission (2023). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg_del/2023/2772/2023-12-22/eng.

- Court of Accounts of the Republic of Moldova and the Swedish National Audit Office for the period of 2018-2022. (2019, April 2). INTOSAI-Donor Cooperation. https://intosaidonor.org/project/court-of-accounts-of-the-republic-of-moldova-and-the-swedish-national-audit-office-for-the-period-of-2018-2020/.

- EEA. (2024). Consolidated Annual Activity Report 2023 (CAAR). Copenhagen: European Environment Agency (EEA). https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/about/working-practices/docs-register/consolidated-annual-activity-report-2023-caar.

- EFRAG. (2024, August 30). ESRS Digital Taxonomy (XBRL): Exposure Draft and Implementation Guidance. https://www.efrag.org/en/news-and-calendar/news/efrag-publishes-the-esrs-set-1-xbrl-taxonomy.

-

Environmental statement 2023. (2024, October 17). https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/environmental-statement-2023.

-

ESRS XBRL Taxonomy, Concluded EFRAG. (n.d.-a). Retrieved October 19, 2025, from https://www.efrag.org/en/projects/esrs-xbrl-taxonomy/concluded.

-

ESRS XBRL Taxonomy, Concluded EFRAG. (n.d.-b). Retrieved October 19, 2025, from https://www.efrag.org/en/projects/esrs-xbrl-taxonomy/concluded.

-

EUR-Lex—02023R2772-20231222—EN - EUR-Lex. (n.d.). Retrieved October 19, 2025, from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg_del/2023/2772/2023-12-22/eng.

- European Commission. (2019). The European Green Deal (COM/2019/640 final). Brussels: European Commission. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52019DC0640.

-

Europe’s air quality status 2023. (2023, April 24). https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/europes-air-quality-status-2023.

- Friede, G., Busch, T., & Bassen, A. (2015). ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 5(4), 210–233.

-

HG659/2023. (n.d.). Retrieved October 19, 2025, from https://www.legis.md/cautare/getResults?doc_id=139980&lang=ro.

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. [CrossRef]

- IAASB. (2024). International Standard on Sustainability Assurance (ISSA) 5000: General Requirements for Sustainability Assurance Engagements [Standard]. IAASB. https://www.iaasb.org/publications/international-standard-sustainability-assurance-5000-general-requirements-sustainability-assurance.

- INTOSAI WGEA. (2025). Guidance on Environmental Auditing. INTOSAI Working Group on Environmental Auditing. https://www.environmental-auditing.org/media/e1ch5sbm/intosai-wgea-guidance-environmental-auditing.pdf.

-

ISSA 5000 Implementation Guide IAASB. (2025, January 27). https://www.iaasb.org/publications/issa-5000-implementation-guide.

- Kotsantonis, S., Pinney, C., & Serafeim, G. (2016). ESG Integration in Investment Management: Myths and Realities. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 28(2), 10–16. [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

-

Law of the Republic of Moldova “About environmental protection.” (n.d.). Retrieved October 19, 2025, from https://cis-legislation.com/document.fwx?rgn=3317.

- Li, X., Tang, J., Feng, C., & Chen, Y. (2023). Can Government Environmental Auditing Help to Improve Environmental Quality? Evidence from China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 2770. [CrossRef]

- Matuszak-Flejszman, A., & Paliwoda, B. (2022). Effectiveness and Benefits of the Eco-Management and Audit Scheme: Evidence from Polish Organisations. Energies, 15(2), 434. [CrossRef]

- MoEW. (2019). National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy and Action Plan 2019–2030. MoEW. https://www.moew.government.bg/static/media/ups/categories/attachments/Strategy%20and%20Action%20Plan%20-%20Full%20Report%20-%20%20ENd3b215dfec16a8be016bfa529bcb6936.pdf.

- Nguyen, Q., Diaz-Rainey, I., Kitto, A., McNeil, B. I., & Pittman, N. A. (2023). Scope 3 emissions: Data quality and machine learning prediction accuracy. PLOS Climate, 2(11), e0000208. [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2023). G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance 2023. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2023/09/g20-oecd-principles-of-corporate-governance-2023_60836fcb/ed750b30-en.pdf.

- OECD & EU4Environment. (2022). Environmental Compliance Assurance System in the Republic of Moldova: Current Situation and Recommendations. OECD Publishing. https://www.eu4environment.org/app/uploads/2022/03/Environmental-compliance-assurance-system-in-the-Republic-of-Moldova.pdf.

- Pizzi, S., Venturelli, A., & Caputo, F. (2024). Restoring trust in sustainability reporting: The enabling role of the external assurance. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 68, 101437. [CrossRef]

- Power, M. (1997). The Audit Society: Rituals of Verification. Oxford University Press.

- Thompson, A., Floroiu, R. M., Ambrosi, P., Milova, E. P., & Bakx, R. (n.d.). Country Manager: Practice Manager: (Co-)Task Team Leaders: Project Coordinator:.

-

Tracking waste prevention progress. (2023, May 17). https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/tracking-waste-prevention-progress.

- UNECE. (2011). Environmental Performance Review: Republic of Moldova (ECE/CEP/171) – full report. Geneva: UNECE. https://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/env/epr/epr_studies/ECE_CEP_171_En.pdf.

- UNECE. (2017). Environmental Performance Review: Bulgaria (ECE/CEP/181) – Synopsis. Geneva: UNECE. https://unece.org/DAM/env/epr/epr_studies/Synopsis/ECE_CEP_181_Bulgaria_Synopsis.pdf.

- UNFCCC. (2025). Bulgaria—2024 Biennial Transparency Report (BTR1). United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. https://unfccc.int/documents/645300.

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/70/1). New York: United Nations. https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda.

- Wang, W., Wang, Z., & Mei, Y. (2023). Have government environmental auditing contributed to the green transformation of Chinese cities? Heliyon, 9(12), e22709. [CrossRef]

-

Water savings for a water-resilient Europe. (2025, June 4). https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/water-savings-for-a-water-resilient-europe.

- Weber, R. P. (1990). Basic content analysis (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- WGS.co.id. (n.d.). INTOSAI Working Group on Environmental Auditing (WGEA). Retrieved October 19, 2025, from https://www.wgea.org/publications/studies-guidelines/.

-

What Are Environmental Certificates in Moldova and Why Moldovan Environmental Regulations 2026 Demand Them? (n.d.). Retrieved October 19, 2025, from https://aboutmoldova.md/en/view_articles_post.php?id=396.

- Zhang, Y., & Wildemuth, B. M. (2009). Qualitative Analysis of Content. In Applications of Social Research Methods to Questions in Information and Library Science (pp. 308–319). Libraries Unlimited.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).