1. Introduction

The use of advanced high-strength steels (AHSS) in vehicle structures, chassis and suspension components have significantly increased in recent decades from an average 2% to >15%, driven by enhanced manufacturability, crashworthiness and weight reduction potential. Typical automotive components manufactured with AHSS include: A-pillars, B-pillars, floor and roof cross members, front and back crush box, battery packages, suspensions arms and many others [

1,

2,

3,

4].

Conventional Dual-Phase AHSS are widely used in safety cage components, outer body and floor panels [

5]. Its microstructure comprises an array of second-phase martensite embedded in a ferrite matrix with strength levels typically increasing up to 1000 MPa, as martensite and bainite volume fraction increases [

6,

7]. In more recent years, a new generation of AHSS have been developed with improved hole expansion and fracture toughness characteristics. These new AHSS have a fine-grained microstructure with nominally 100% ferrite. Within this ferrite matrix are precipitated carbides and carbonitrides of Nb, Ti, V, and Mo. Whilst some of these micro-alloyed precipitate promote grain refinement, a substantial amount of strength from precipitation strengthening is gained from these carbonitrides.

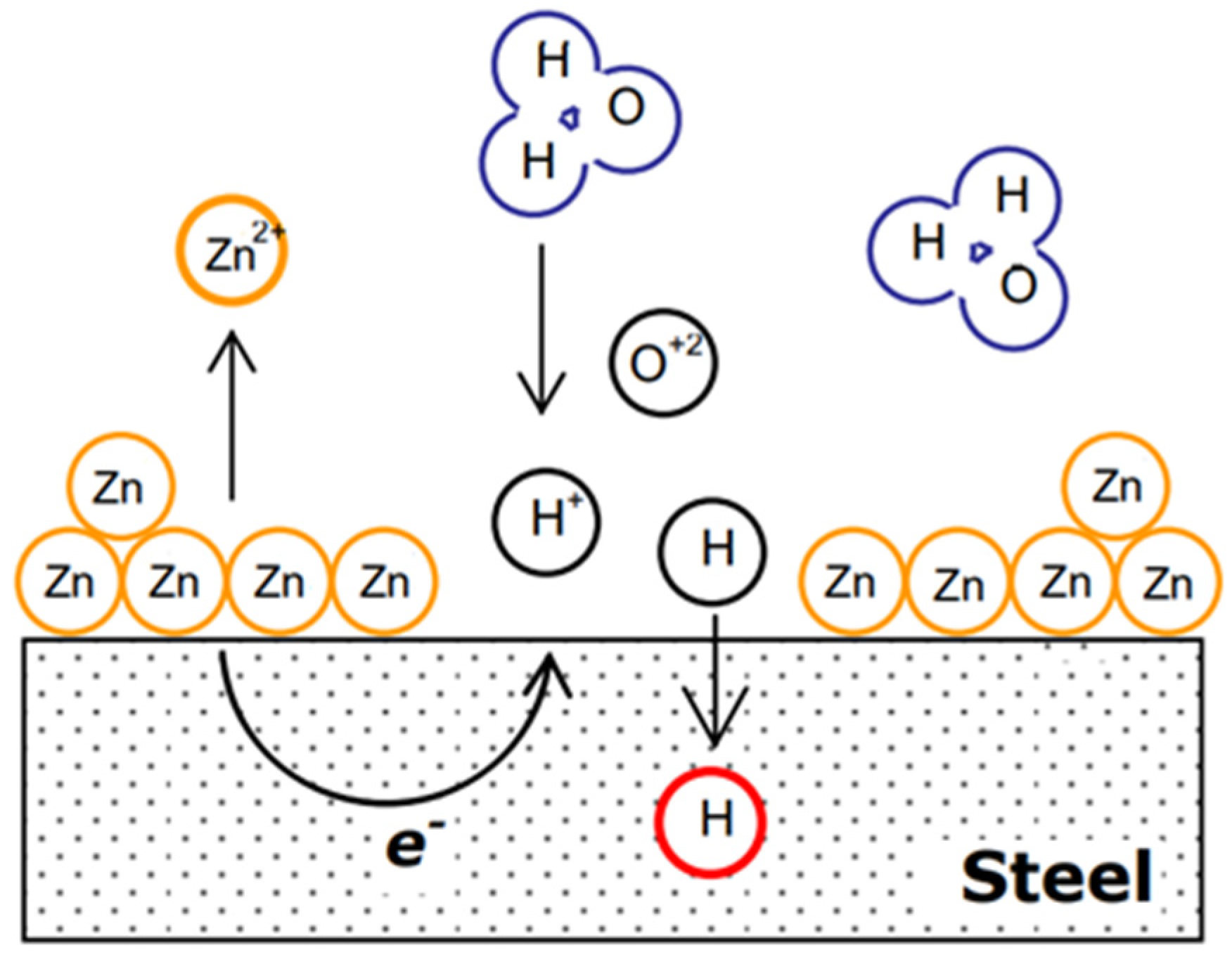

Sacrificial galvanic coatings are commonly applied to these steel components to protect them from rust and corrosion. Zn-based galvanised coatings are the most accepted in the automotive industry [

8]. However, should these coatings become damaged during service, a galvanic cell could be generated in the presence of an electrolyte such as salty water, as depicted in

Figure 1. Whilst anodic reactions arise in the sacrificial zinc coating (Equation 1) the steel substrate becomes the cathode, where hydrogen evolution takes place (Equation 2). Other cathodic reactions could take place (Equations 3 and 4), depending on local pH levels.

At the cathodic surface atomic hydrogen can be absorbed directly beneath the steel substrate following the coupled discharge-recombination mechanism [

9,

10]. Over time hydrogen diffuses within the steel microstructure in sufficient quantities, increasing the risk to hydrogen embrittlement (HE) and its associated deterioration of mechanical properties.

Automotive steel grades considered in the present study are also regularly used in the galvanised condition, and it is therefore important to understand how hydrogen evolution and uptake take place when the sacrificial coating becomes damaged in service. The Scanning Vibrating Electrode Technique, SVET, has been shown to be an effective technique to quantify galvanic corrosion on hot-dipped galvanised steels [

11,

12].

Ingress of atomic hydrogen into the steel greatly lowers its strength, ductility and toughness, causing it to fail under loads well below those expected during service. Proposed HE mechanisms for steels are either based on lattice decohesion, where diffusing hydrogen weakens lattice bonds, or hydrogen induced plasticity, where diffusing hydrogen reduces the stress required for formation and motion of crystal imperfections associated with plastic deformation, such as dislocations [

13,

14,

15]. It is also recognised that hydrogen embrittlement susceptibility increases with strength levels. Nonetheless hydrogen diffusivity within the steel microstructure plays a key role [

16]. In the present study the hydrogen embrittlement susceptibility of the latest generation ferritic nano-precipitate (FNP) is compared to that of more conventional dual-phase ferritic-martensitic (FM) AHSS at equivalent strength levels via use of slow strain-rate (tensile) tests (SSRT), with hydrogen diffusion coefficients measured using the well-established potentiostatic permeation technique [

17].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

AHSS considered in the current work include conventional ferrite-martensite dual-phase steels with strength levels of 800 and 1000 MPa, identified as FM800 and FM1000. The new generation ferritic nanoprecipitate AHSS at equivalent strength levels, were identified as FNP800 and FNP1000, respectively. Chemical compositions for these steels are displayed in

Table 1, with baseline mechanical properties assessed via conventional tensile tests shown in

Table 2. Microstructural characterisation was carried out using a Zeiss Evo scanning electron microscope operating at 20 kV accelerating voltage, 100-150 pA probe current. Grain size analysis was performed via the linear intercept method using Matlab software [

6,

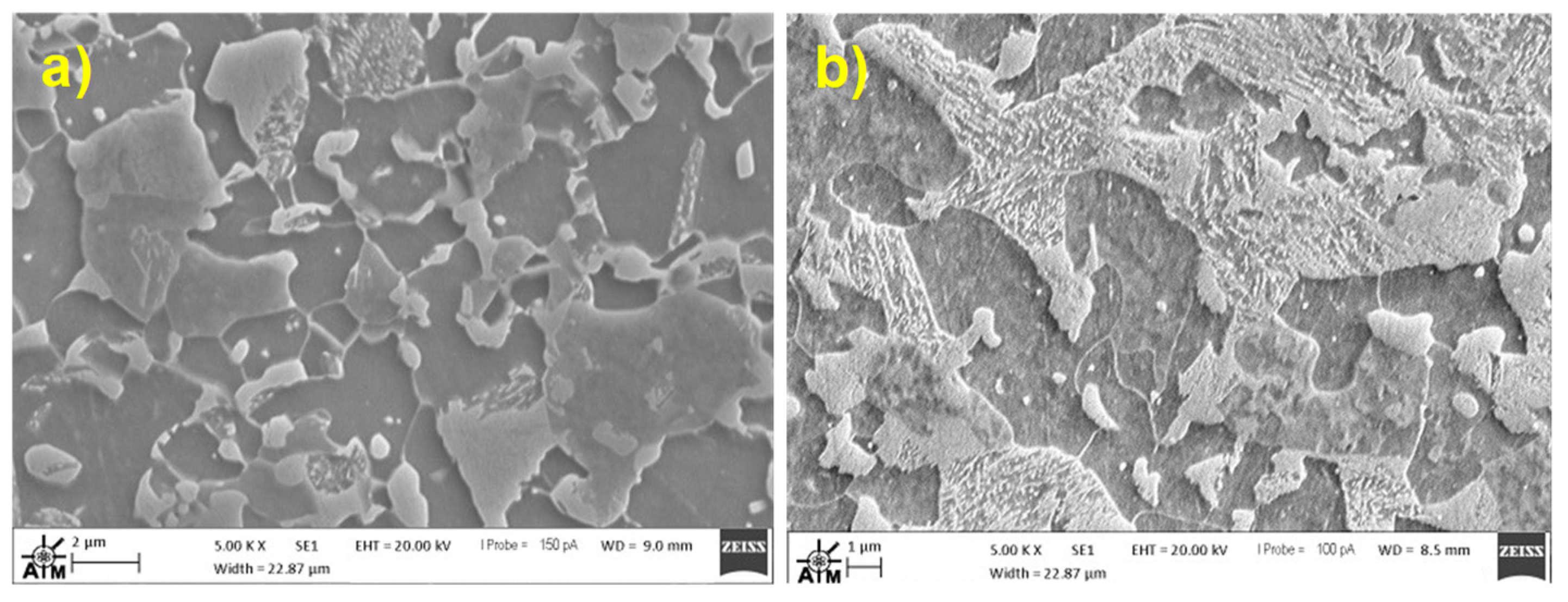

18]. The typical microstructure of the FM steels can be seen in

Figure 2, with the darker regions showing the ferrite (α) phase, and the lighter regions the martensite (α’) phase. Relative volume fractions of each phase were estimated using segmentation technique in ImageJ software [

19]. Martensite volume fractions were 40% and 55% for FM800 and FM1000, respectively. These values were comparable with the figures obtained from the literature [

20,

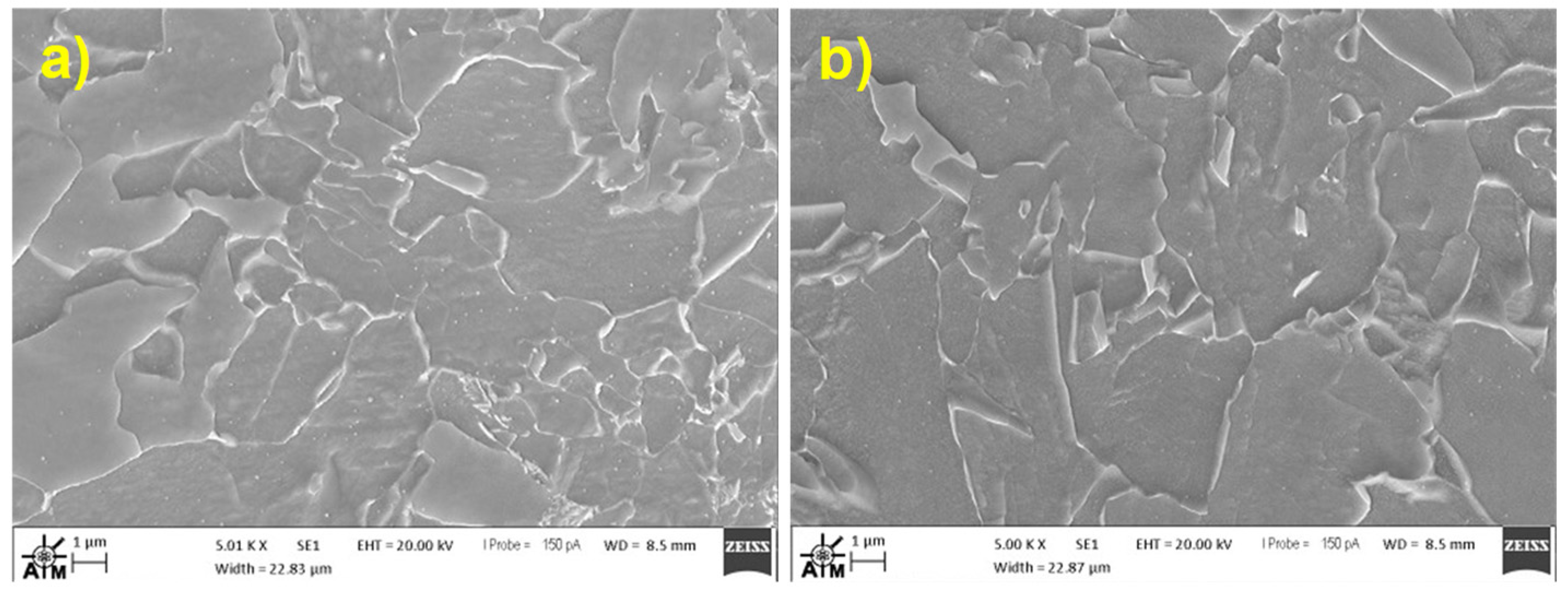

21]. The FNP steels appear to have a 100% ferrite microstructure and an average grain size of 2.3 µm (diameter). There is little evidence of any Fe

3C formations, either lamellar or globular, as shown in

Figure 3.

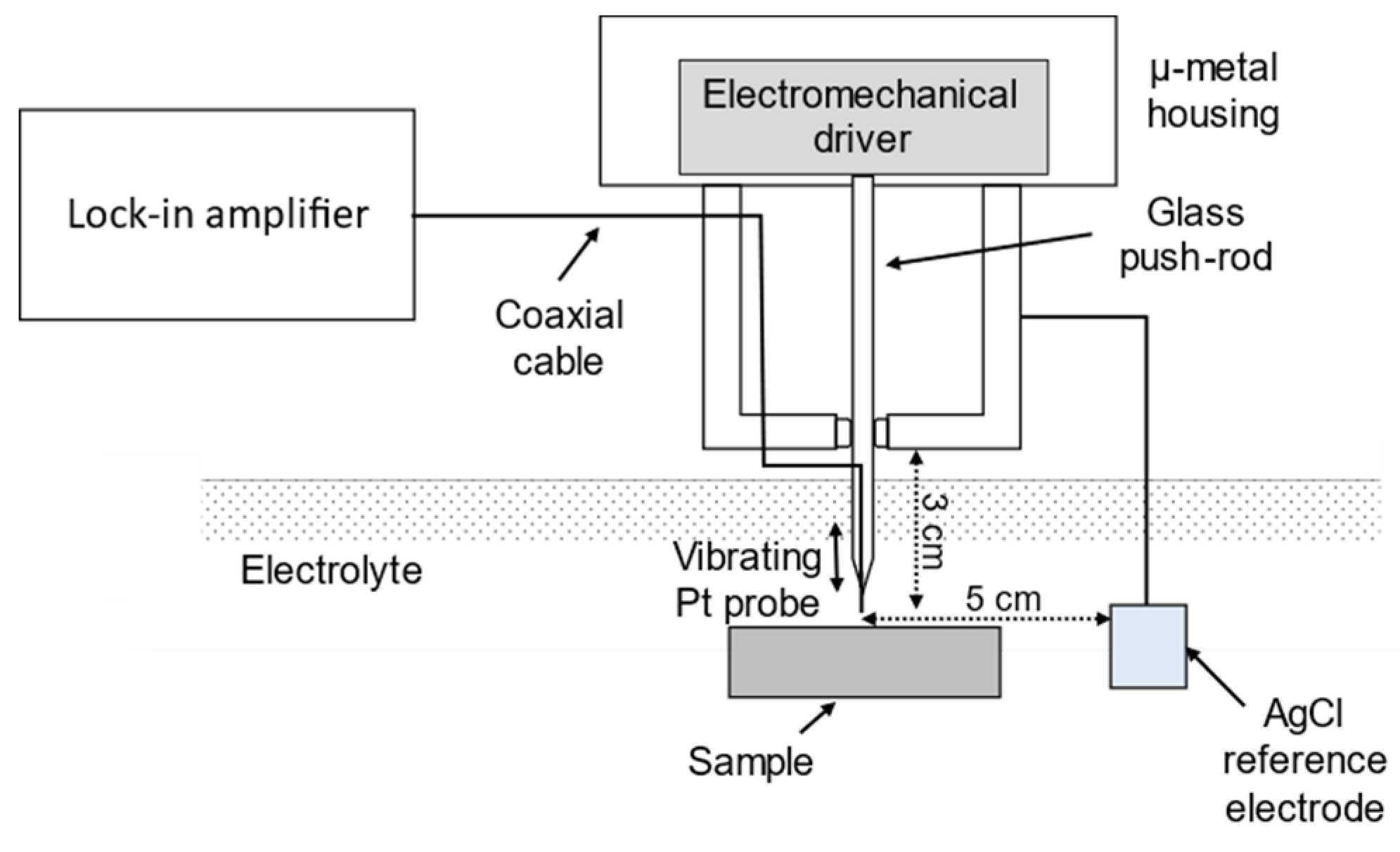

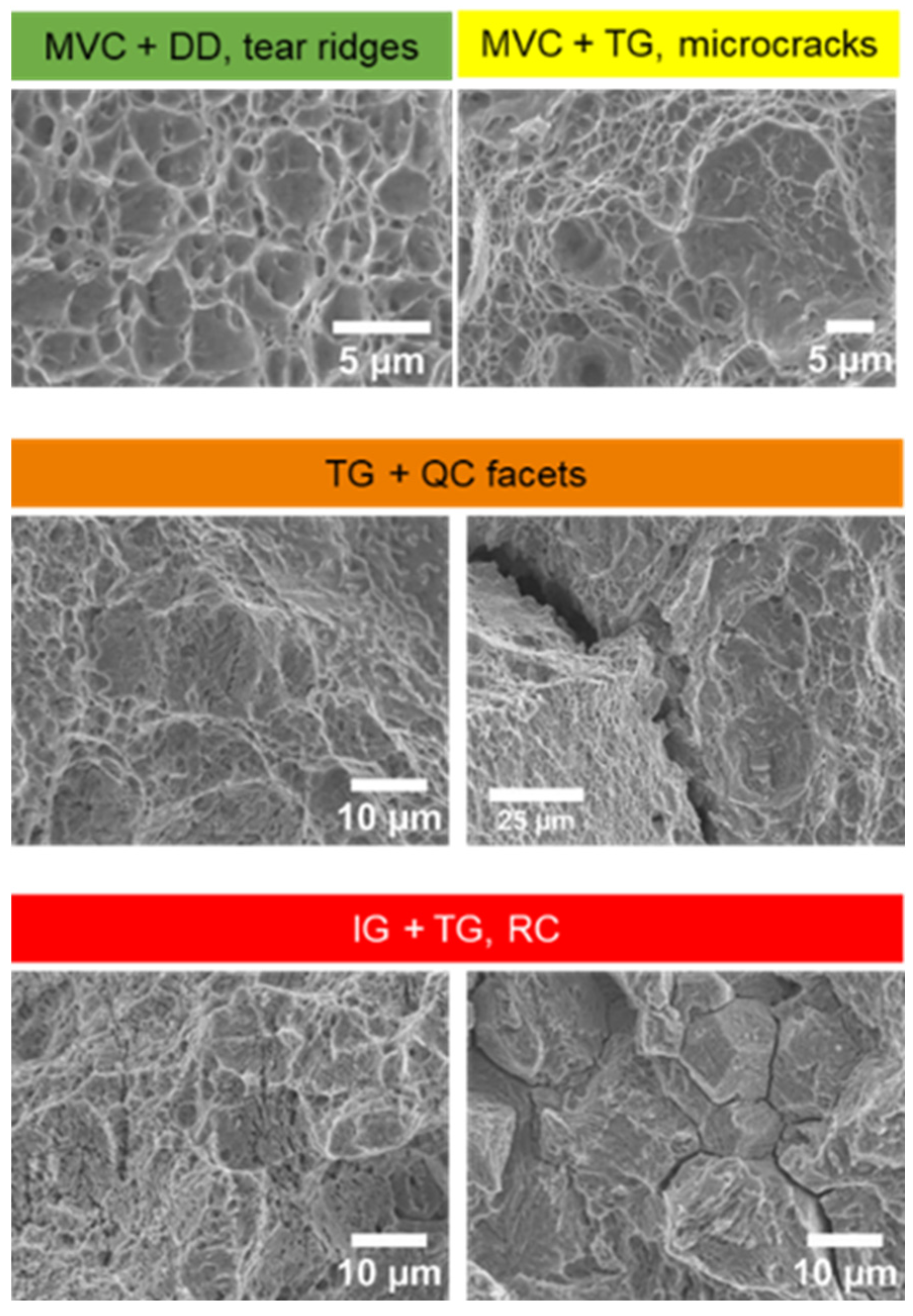

2.2. Effect of Galvanic Corrosion Upon Hydrogen Evolution

To examine the impact of galvanic corrosion on hydrogen evolution, the local anodic and cathodic current densities during immersion in 0.1 M NaCl solutions were quantified using a scanning vibrating electrode technique (SVET). One half of the surface of a 30 × 30 mm zinc-coated coupon was ground with P1200-grit silicon carbide grinding paper to expose the steel substrate (using ethanol as lubricant to avoid inducing corrosion prior to immersion). SVET measurements were undertaken using a probe tip 250 µm in diameter, mounted on a moving coil electromagnetic driver connected to a 140 Hz vibrating probe [

11,

12,

22].

Figure 4 shows a schematic of the SVET tip and housing. Scans were undertaken every 30 minutes over the course of 24 hours to provide a series of spatial and time-resolved current density measurements along the axis of measurement, J

z, across the surface. Data post-processing was done using Golden Surfer10 and Matlab software.

2.3. Hydrogen Diffusion

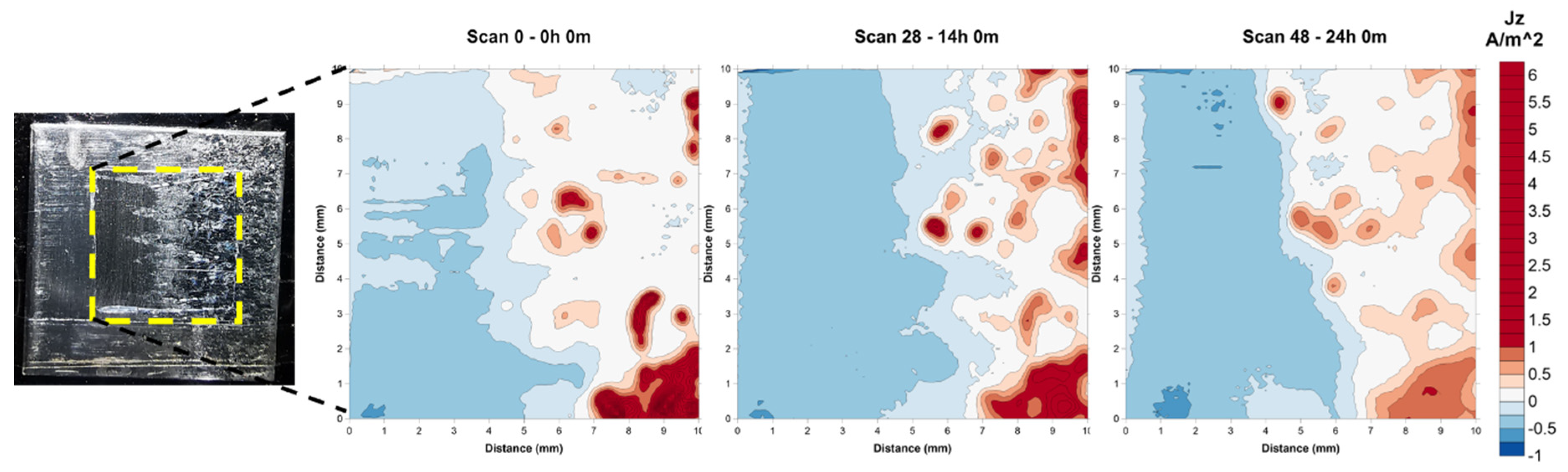

Hydrogen diffusion coefficients were measured using a Devanathan-Stachurski cell [

17] as depicted schematically in

Figure 5.

Permeation samples had nominal thickness of 0.8 mm with charging surface area of 2.011 cm

2. The charging cell contained a 3.5% NaCl + 3 g/L NH

4SCN, pH 4.56, while the oxidation cell contained 0.1 M NaOH solution, pH 13. A charging potential of -1050 mV vs saturated calomel electrode (SCE) was applied after preliminary desorption cycles were completed, typically after 14 hours. As diffusing hydrogen is oxidised it generates a corresponding measurable current until it reaches steady-state, generating a characteristic permeation curve. The current I

t, at time t, is converted to a hydrogen permeation flux, J

t, with the following equation [

23]:

where A is the surface area exposed to the electrolyte in the oxidation cell, and F is the Faraday constant (96,485 coulombs/mol). The lag time, t

lag, described as the time taken when

Jt/

J∞ = 0.63, was used to calculate the effective diffusion coefficient, D

eff, according to the following equation:

where L is the membrane thickness in cm. The surface concentration of hydrogen at the charging side was calculated according to the following equation:

These parameters were used to simulate the perfect ‘Fickian’ curve, and compered to that obtained from the experimental data. For potentiostatic charging the transient of the permeation flux according to Fick’s diffusion is recreated by the following equation.

2.4. Embrittlement Indices, EI, and Slow Strain Rate Test, SSRT

Mechanical property degradation due to hydrogen was assessed using slow strain-rate tensile tests, SSRT. Sample nominal thickness was 0.8 mm and the total length 64 mm. SSRT were carried out at a nominal strain-rate of 8.33 × 10

-6 /s. For SSRT involving hydrogen charging, a bespoke cell was placed around the sample gauge length with approximately 30 mL of 3.5% NaCl + 3g/L NH

4SCN. Samples were potentiostatically polarised at -1050 mV versus a saturated calomel reference electrode, SCE, with a platinum foil counter electrode. Hydrogen pre-charging was undertaken for 2 hours. The hydrogen embrittlement index, EI, was assessed according to the decrease in time-to-failure, TTF, calculated according to the following equation:

Student’s t-test was used to determine whether there were statistically significant differences between test populations. Comparing the means of the two data populations enables calculation of a test statistic, t, through the equation:

where m

1 and m

2 represent the means of the two data sets, and n

1 and n

2 the number of measurements in each set. s is calculated from the standard deviations of the two populations:

where s

1 and s

2 represent the standard deviations of the two data sets. The test statistic, t, is then compared with tabulated values for a 95% confidence level with ((n

1 -1) + (n

2 -1)) degrees of freedom. If the test statistic < t-distribution, with a 95% confidence level the datasets belong to the same population, i.e. acceptance of the null hypothesis [

24].

Weibull distributions were used to show the probability of survival of a group of specimens before failure through hydrogen embrittlement. The time-to-failure data for each set of product-test condition pairs was compared with a mean time-to-failure of the un-charged condition for each of the steels. The Weibull model was adapted for analysis through brittle failure, in showing that the probability of a specimen not failing within a specified time, t, is calculated according to the following equation [

24]:

where

P(s) is the probability of survival, P

(f) the probability of failure and

x the shape parameter known as the Weibull slope.

x is the probability per unit time, t, that a crack forms of sufficient severity to cause failure of the specimen and is deduced from the negative gradient of a plot of ln

P(s) versus t. As there is a minimum time for a critical crack to initiate, t

i, the graph is displaced along the time axis by this amount, i.e. when P

(s) = 1, ln P

(s) = 0 and t=t

i, modifying equation (12) to become [

25]:

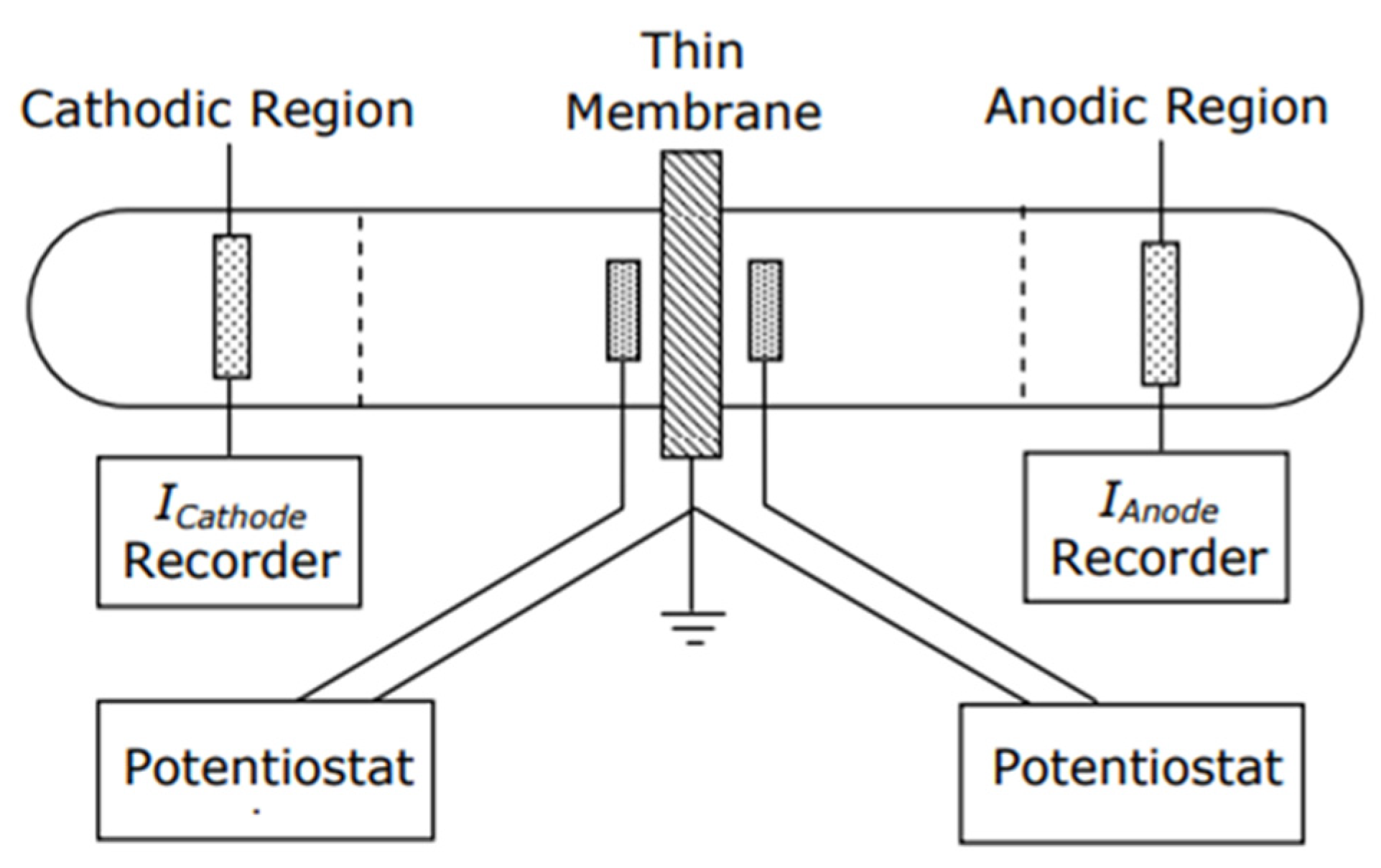

2.5. Fractography

Fracture surface analysis was undertaken by SEM. Images were then analysed using ImageJ software. Regions of the fracture surface were assigned a colour depending on the dominant features observed in a particular location. Quasi-cleavage (QC) facets and regions of intergranular (IG) fracture represented a more brittle fracture mode, whereas micro void coalescence (MVC), shear voids, and tear ridges (TR) occurred in more ductile failures. Trans granular (TG) cracks can be found in both ductile and brittle regions, and typically occur where both mechanisms are present, as shown in

Figure 6. Fractographic quantitative assessment was carried out using Matlab software.

3. Results and Discussion

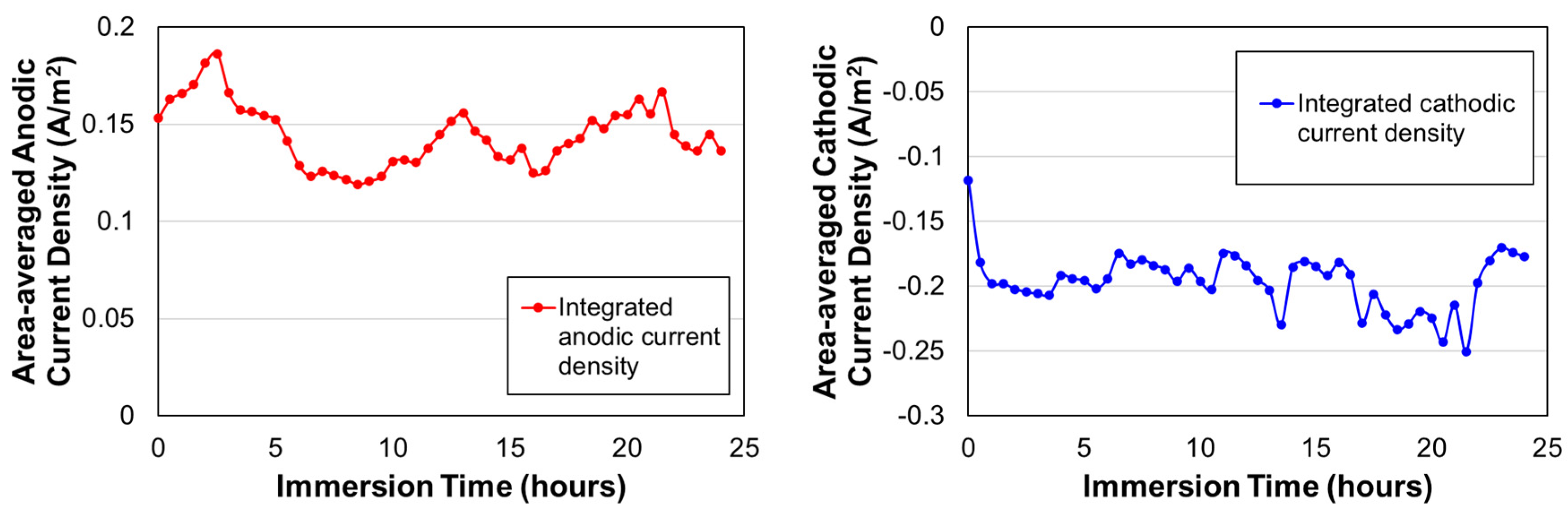

3.1. Effect of Galvanic Corrosion Upon Hydrogen Evolution

Figure 7 shows a selection of contour plots of SVET scan data displaying regions of cathodic (blue) and anodic (red) activity as galvanic corrosion process in the relatively weak 0.1 M NaCl solution. Regions with relatively high localised anodic activity, current density up to 6.01 A/m

2, take place as the Zn sacrificial coating is corroded in a localised manner. At the exposed steel substrate a wide region with cathodic current densities (blue) is shown with a maximum cathodic current density of -0.53 A/m

2. This current density is indicative of cathodic polarisation at the steel surface that promotes hydrogen evolution, albeit in competition with a diffusion-limited oxygen reduction reaction [

26]. After 2.5 hours, the anodic regions (red) begin to expand, but with lower intensity, indicating that localised pitting has ceased and corrosion of the zinc has become more general. The cathodic regions periodically develop some localised regions of increased cathodic current density, particularly after about 14 hours, peaking around 20 hours. After 24 hours, both anodic and cathodic activity had reduced intensity from peak current densities in these localised, previously high-intensity regions.

Figure 8 shows the averaged anodic and cathodic current densities, I

a and I

c, respectively, calculated according to Equation (14) (the equivalent for anodic current density with respect to time, J

at, calculated using J

z(x,y) > 0)

The measured total anodic current density shows greater stability over the 24 hour duration of the test than the maximum current density plot indicating there is significant sacrificial corrosion of the zinc coating as the immediate pitting behaviour subsides and continuing throughout. Cathodic current density measurements show a degree of fluctuation but measure consistently higher than the anodic current density, as illustrated in

Figure 9. The most strongly cathodic areas showed current density below -0.3 A/m

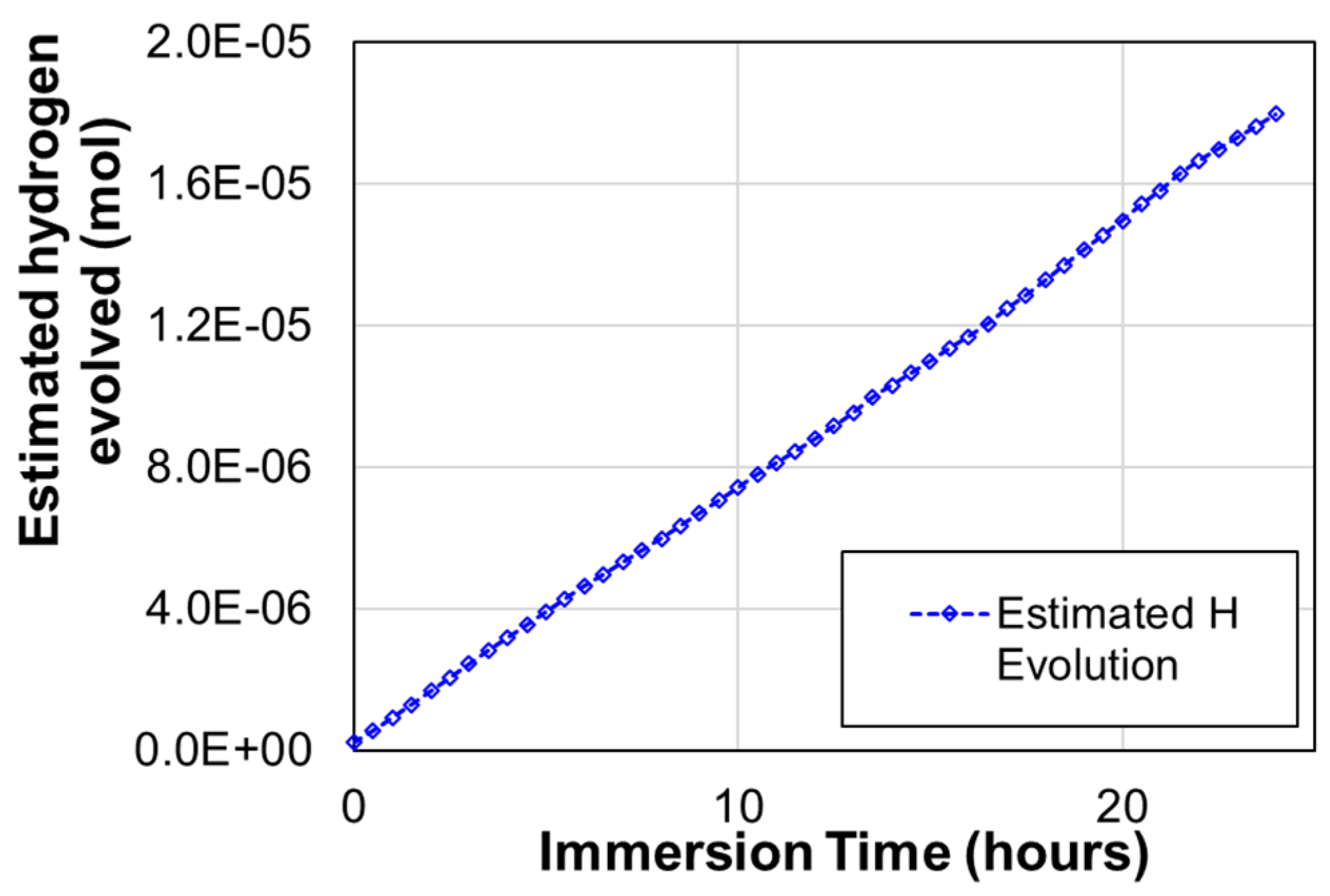

2, of a similar order to cathodic current densities seen during potentiostatic hydrogen charging (at -1050 mV SCE in 3.5% NaCl) for both permeation and slow strain-rate tests. By applying Faraday’s Law, it is possible to calculate an estimate for the total hydrogen evolved at the exposed steel surface according to equation:

where Q is the total charge in C/m

2 and tm the scan time in seconds, with integration performed numerically and assuming that J

ct is constant between scans.

Figure 10 shows calculated values for hydrogen evolved at the exposed steel surface over the duration of the experiment. The total hydrogen evolved over 24 hours was > 1.6 × 10

-6 mols.H.

3.2. Hydrogen Diffusion

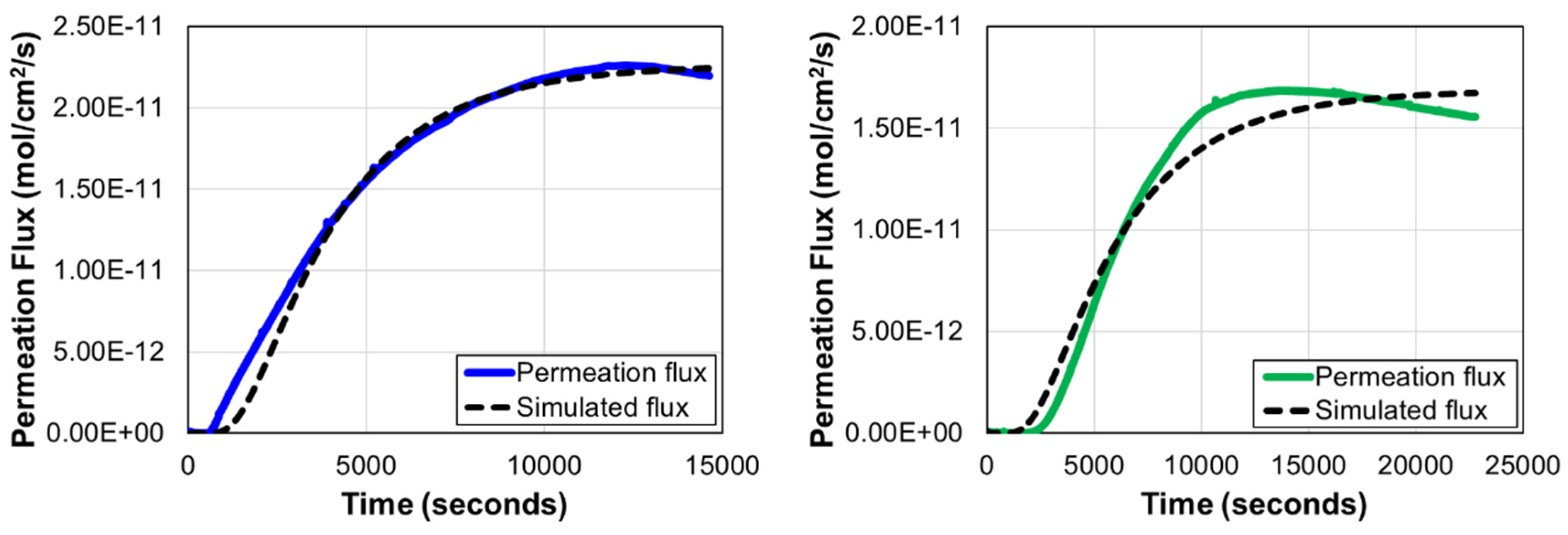

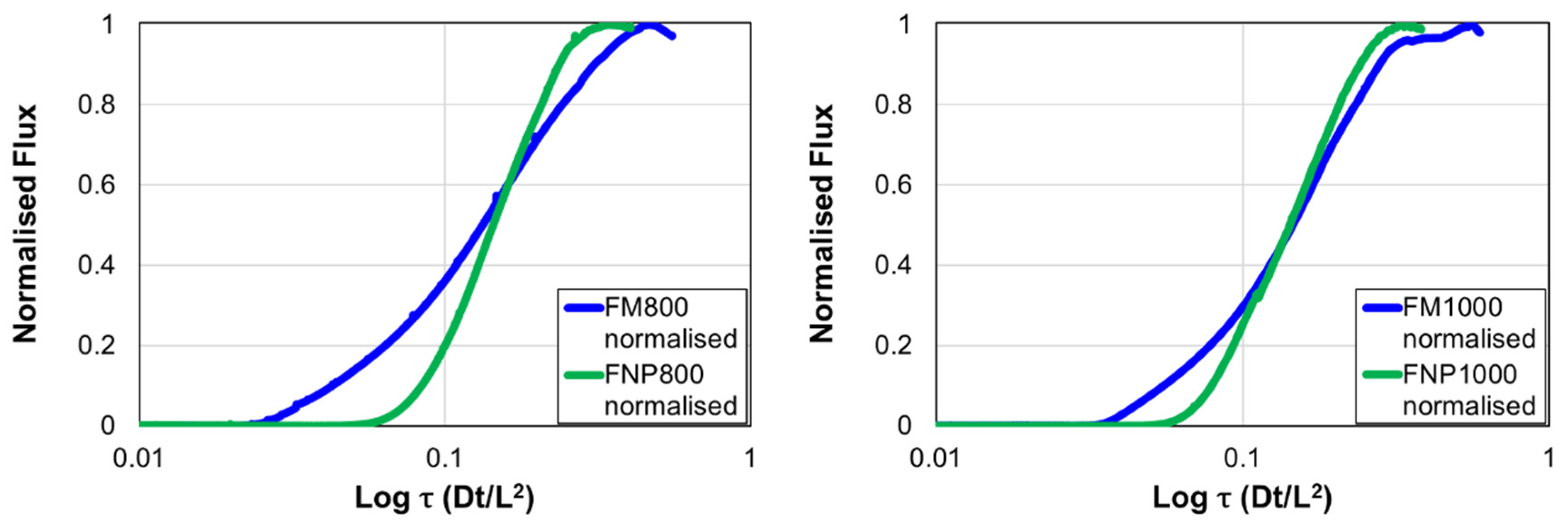

Permeation curves for FM800 and FNP800 AHSS are shown in

Figure 10. For FM800 the breakthrough time, t

b, was 1,033 seconds, the lag time, t

lag, was 4,397 seconds and the maximum flux, J

∞, was 2.2 ×10

-11 mol/cm

2/s. The calculated mean effective diffusion coefficient, D

eff, was 1.87×10

-7 cm

2/s, and the maximum hydrogen concentration at the charging surface, C

0, was 8.51×10

-6 mol/cm

2. The FNP800 steel showed a t

b value of 3,373 seconds, a t

lag of 6,682 seconds and J

∞ of 1.68×10

-11 mol/cm

2/s. The calculated mean effective diffusion coefficient, D

eff, was 1.68×10

-7 cm

2/s, and the maximum hydrogen concentration at the charging surface, C

0 was 8.21×10

-6 mol/cm

2.

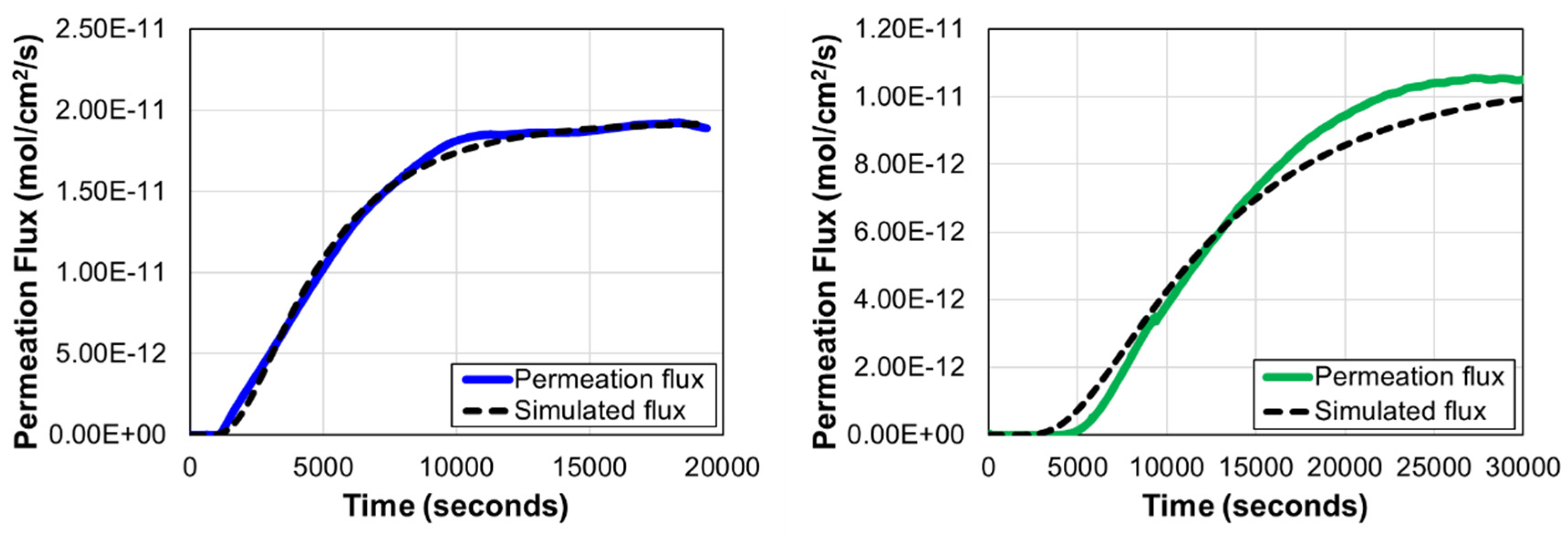

For AHSS at 1000 MPa strength, permeation curves in

Figure 11 show that the FM1000 steel had t

b of 1,481 seconds, a t

lag of 5,445 seconds and a J

∞ of 1.93×10

-11 mol/cm

2/s. The calculated mean effective diffusion coefficient, D

eff was 1.45×10

-7 cm

2/s, and the maximum hydrogen concentration at the charging surface, C

0, was 9.14×10

-6 mol/cm

2 . The FNP1000 AHSS had t

b of 6,628 seconds, a t

lag of 13,944 seconds, J

∞ of 1.20×10

-11 mol/cm

2/s, D

eff of 7.45×10

-8 cm

2/s, and C

0 of 1.54×10

-5 mol/cm

2.

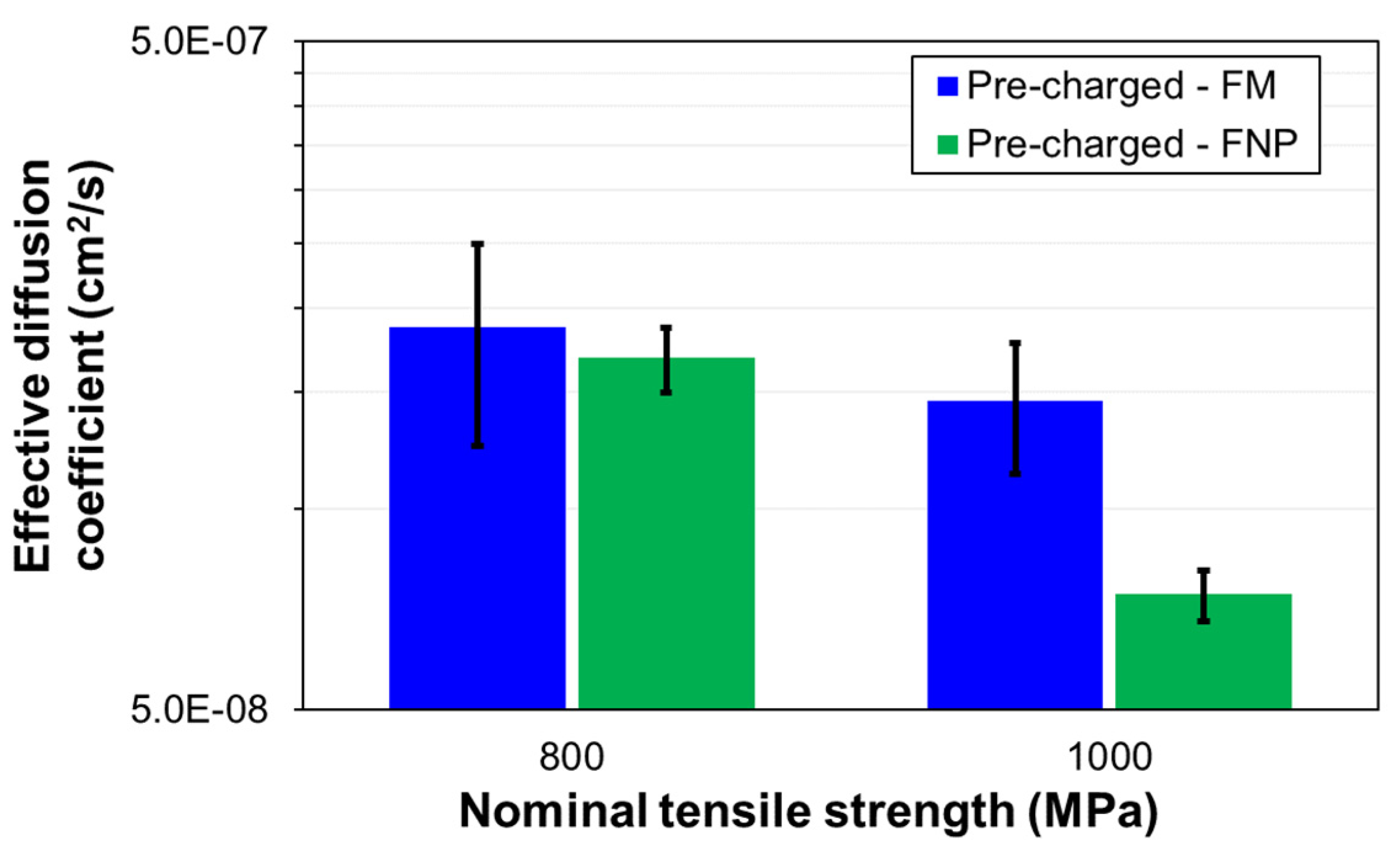

Figure 12 shows the differences between effective diffusion coefficient calculated from data obtained in permeation tests.

The fully-ferritic FNP steels have shown to have much lower effective diffusivities than the equivalent ferrite-martensite FM steels at same strength levels. FNP steels exhibit clear differences between the permeation curves simulated according to Fick’s laws and the measured permeation flux, as shown in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11. The initial rising transient is displaced to a longer (delayed) breakthrough time, t

b, before rising more steeply than the simulated Fick’s curves. This increase in t

b has been previously reported to be caused by a higher overall hydrogen trap density [

27,

28]. Permeation curves for FM steels at equivalent strength levels did not show a delay in t

b. Indicating that the FNP steels contain a greater trap density than the equivalent strength FM steels.

As diffusible hydrogen saturates the irreversible traps before filling reversible traps or diffusing through the lattice, the overall hydrogen diffusivity is impacted to a greater degree by the presence of irreversible traps compared to reversible ones [

29]. The overall shape of the permeation curve between t

b and J

∞, however, is unlikely to be influenced by the presence of strong traps [

30]. FNP steels might contain a relatively high density of irreversible trap sites, not necessarily high densities of reversible trap sites.

FNP steels are alloyed with Nb, V and Mo resulting in the formation of nano precipitates including NbV, NbVMo, and carbide/carbo-nitride. These precipitates suppress the formation of second phase Fe

3C maintaining a fine-grained, fully-ferritic microstructure [

31]. It has been reported that such precipitates could act as irreversible traps, particularly if precipitates are very fine [

13]. Depover [

32,

33,

34] showed that Ti, V, Mo carbides are able to trap a significant amount of hydrogen in steels containing 0.1 – 0.3 wt.% C [

35]. The lower relative diffusivity of the FNP steels could be associated to the presence of these nanoprecipitates in the microstructure.

FM steels with shallower permeation transients indicate the presence of low irreversible trap densities and higher density of reversible traps, more clearly illustrated in “normalised” permeation curves seen in

Figure 13. FM steels contain substantial volume fractions of martensite, formed via a displacive transformation, resulting in high dislocation densities. Numerous studies have shown that dislocations represent reversible hydrogen traps, decreasing the gradient of the rising transient, but not impacting the overall effective diffusivity, D

eff, to the same degree as irreversible traps [

36,

37,

38,

39].

3.3. Slow Strain Rate Tests & Fractography

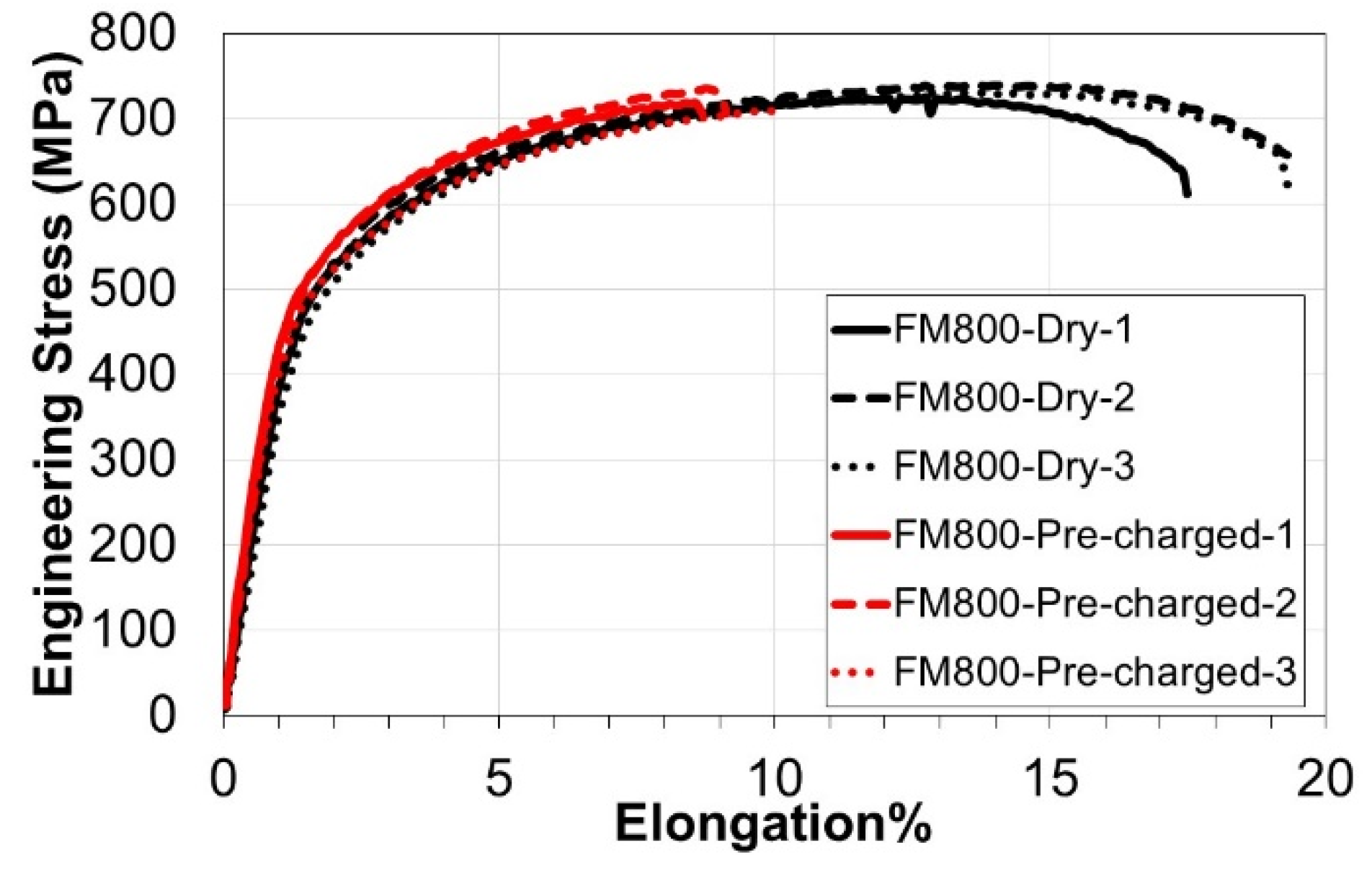

A considerable reduction in ductility for FM800 steel due to hydrogen charging can be seen in

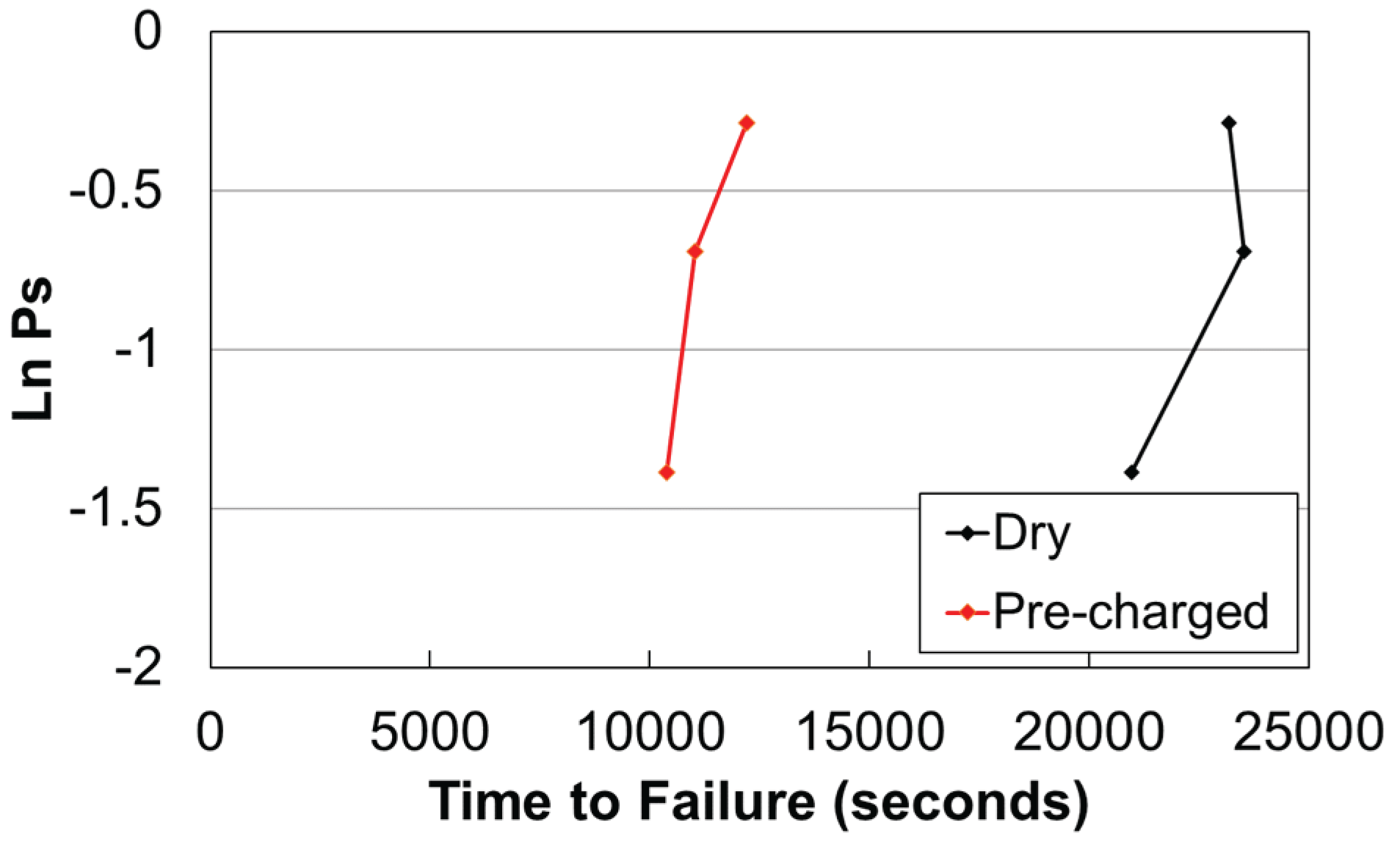

Figure 14. The mean total elongation dropped from 18.9%, in the dry condition, to 9.4% in the hydrogen charged condition. The mean TTF value for the dry condition was 6.3 hours, reducing to 3.1 hours for the dry and hydrogen charged condition, respectively. Weibull plots in

Figure 15 showed that TTF values were consistent for each test condition. Student’s t-test results showed with a 95% confidence that there is a statistically significant difference between the two populations, dry and hydrogen charged conditions.

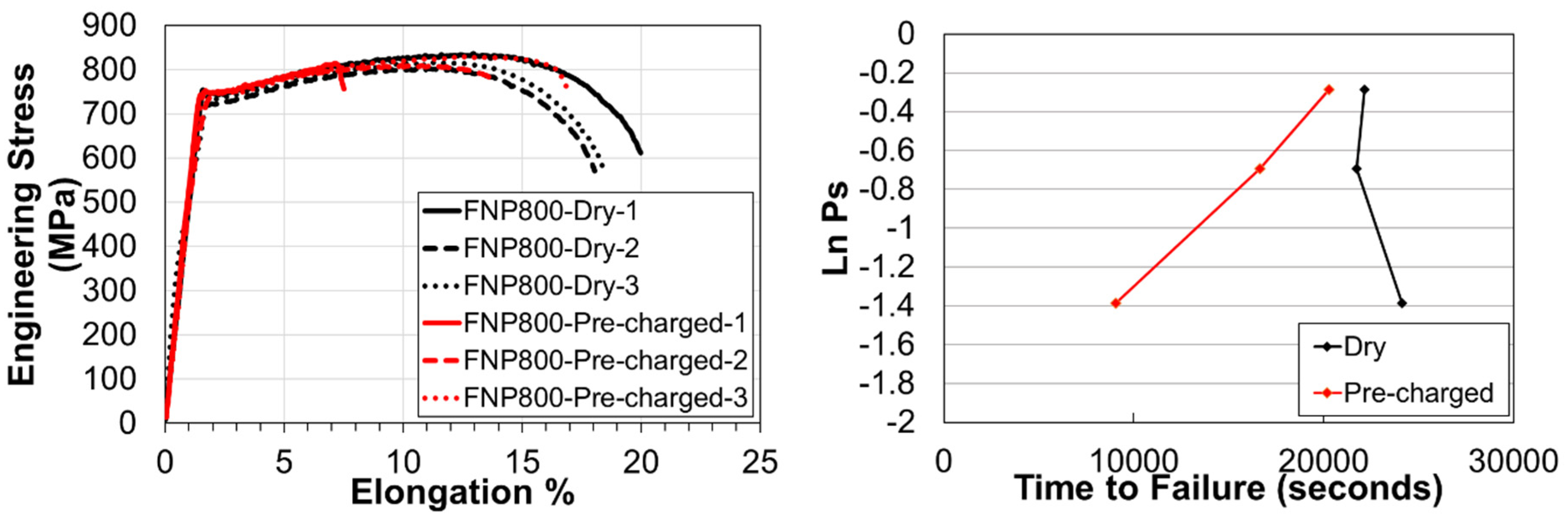

Figure 16 shows FNP800 mean total elongation dropped from 18.9%, in the dry condition to 12.8%, in the hydrogen pre-charged condition, although one of the tests (pre-charged test 3) appears to have persisted to a significantly higher elongation than the others for the same conditions. It could be argued that the reduction in ductility during the pre-charged tests on FNP800 is within the scatter of the dry test condition, showing substantially less obvious reduction in elongation than for the equivalent strength FM steel. Student t-test results showed with a 95% confidence that there was no statistically significant difference between the conditions tested, although the Weibull suggests two distinct populations when compared according to TTF.

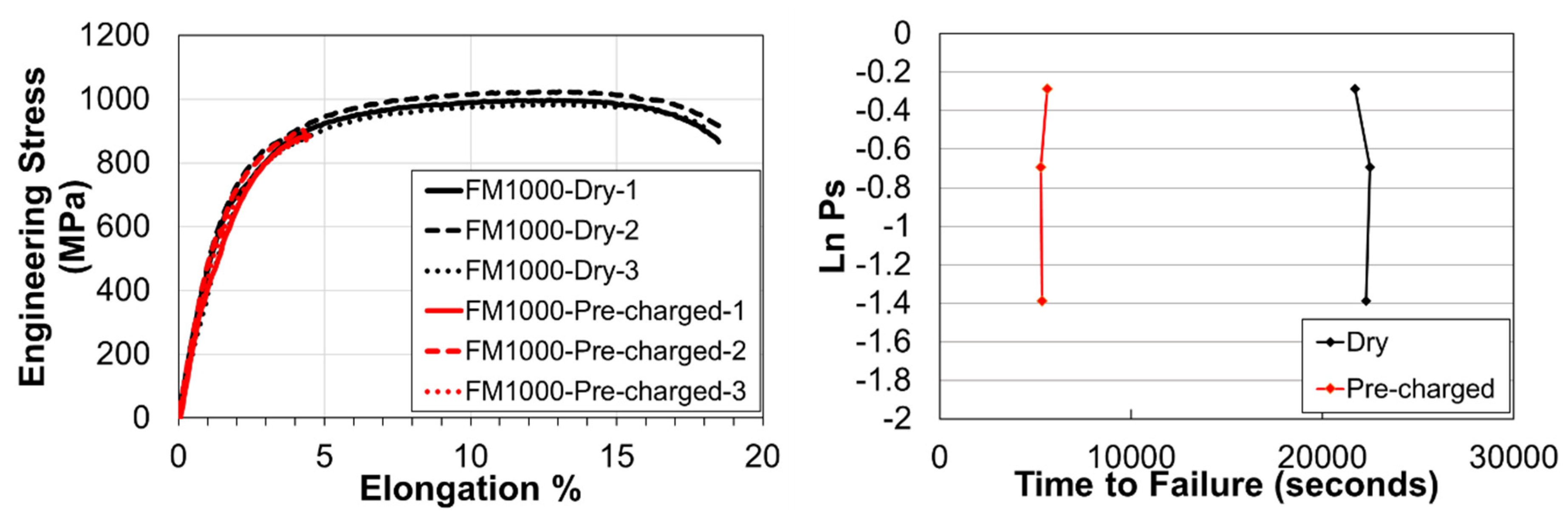

SSRT curves for FM1000 are shown in

Figure 17. A severe loss of ductility is shown for the hydrogen charged condition, with mean total elongation dropping from 18.5%, in dry tests, to just 4.6% for hydrogen charged tests. The mean TTF was reduced from 22,158 seconds to 5,418 seconds. FM1000 experienced a large drop in performance in the presence of hydrogen, and this is validated in the output of the t-tests. FNP1000 SSRT curves are shown in

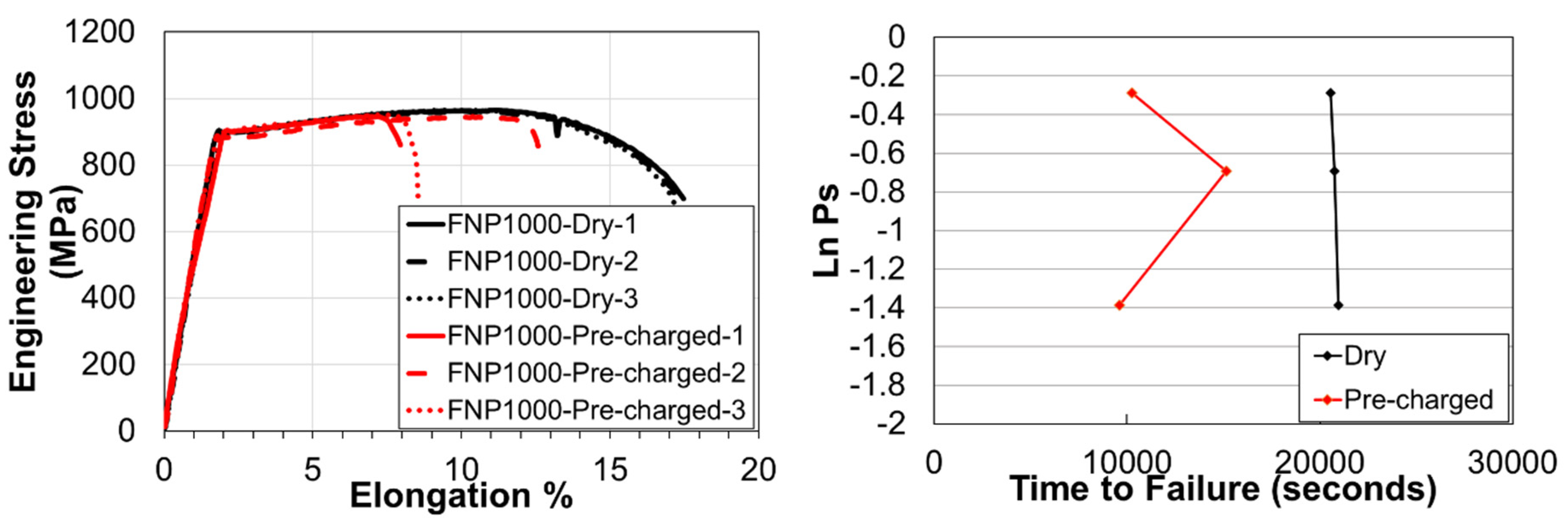

Figure 18. The mean total elongation was reduced from 17.4% to 10.0%, for the dry and hydrogen charged conditions respectively. TTF mean values decreased from 20,762 seconds in the dry condition, to 11,633 seconds for the hydrogen charged condition.

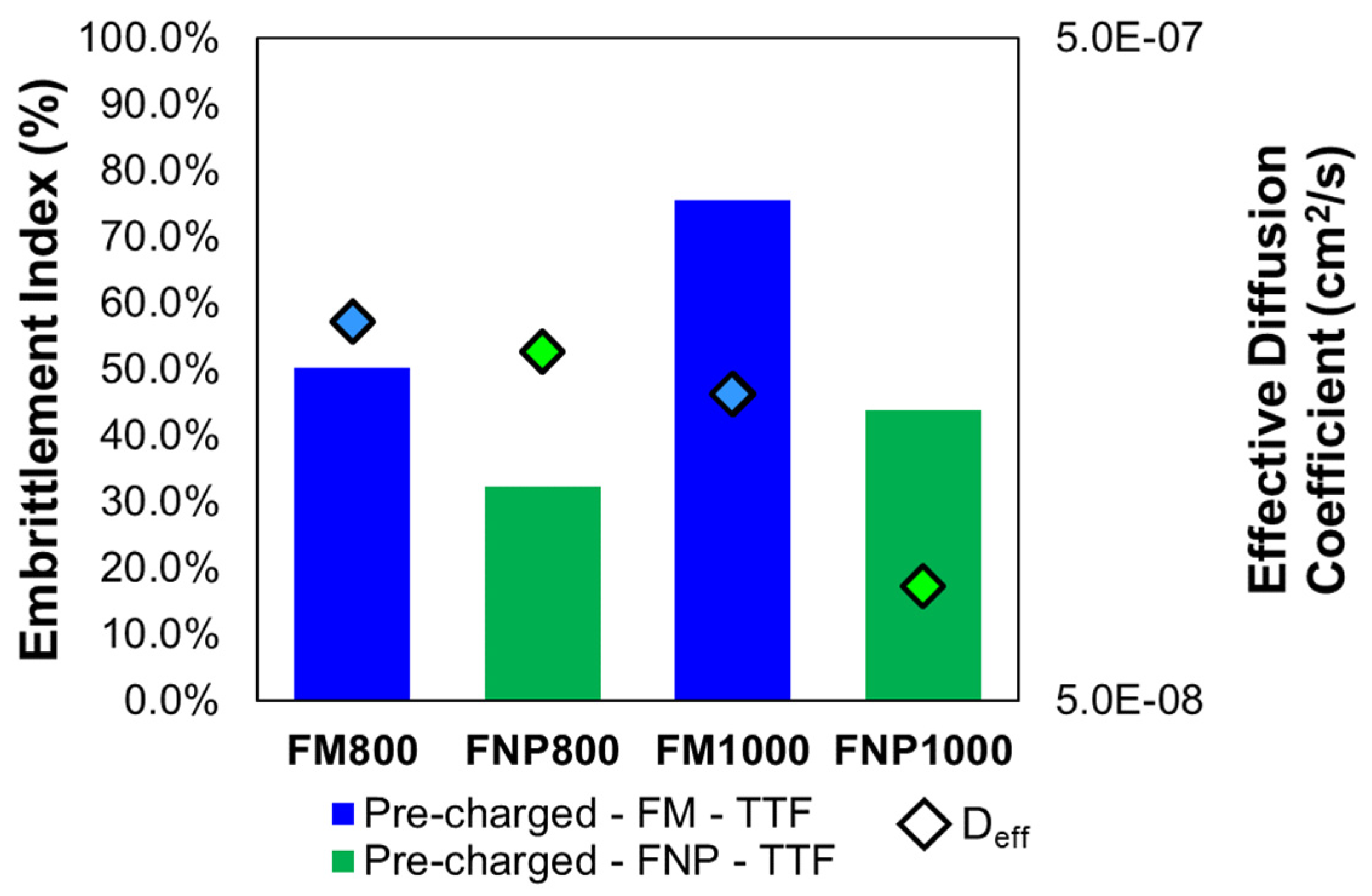

Embrittlement indices for all AHSS considered are summarised in

Table 3. It is clear that at a given strength level, the fully-ferritic FNP AHSS showed significantly lower hydrogen embrittlement susceptibility than the conventional ferritic-martensitic FM AHSS. It is notable that within strength levels this shows a more clear correlation with the relative effective diffusivity as shown in

Figure 19. Differences in hydrogen embrittlement susceptibility between FNP and FM steels at equivalent strength levels are due to the distinctive microstructures.

Several studies on dual-phase steels have shown that the ferrite-martensite microstructure may be inherently susceptible to hydrogen embrittlement. Koyama [

40] found that hydrogen charging facilitates the nucleation of cracks in the martensite phase by decreasing the critical strain required for such an initiation (via the mechanism known as hydrogen-enhanced decohesion (HEDE)), promoting cracking at the ferrite/martensite boundaries, and trans-granular failure. Takashima [

41] also found that where stress is sufficiently high, cracks will propagate through the martensite, avoiding the ferrite phase and causing a unique fracture surface with irregular roughness. Trans-granular cracking in the ferrite phase and cracking at ferrite/martensite boundaries are mechanisms more commonly associated with hydrogen-enhanced localised plasticity (HELP).

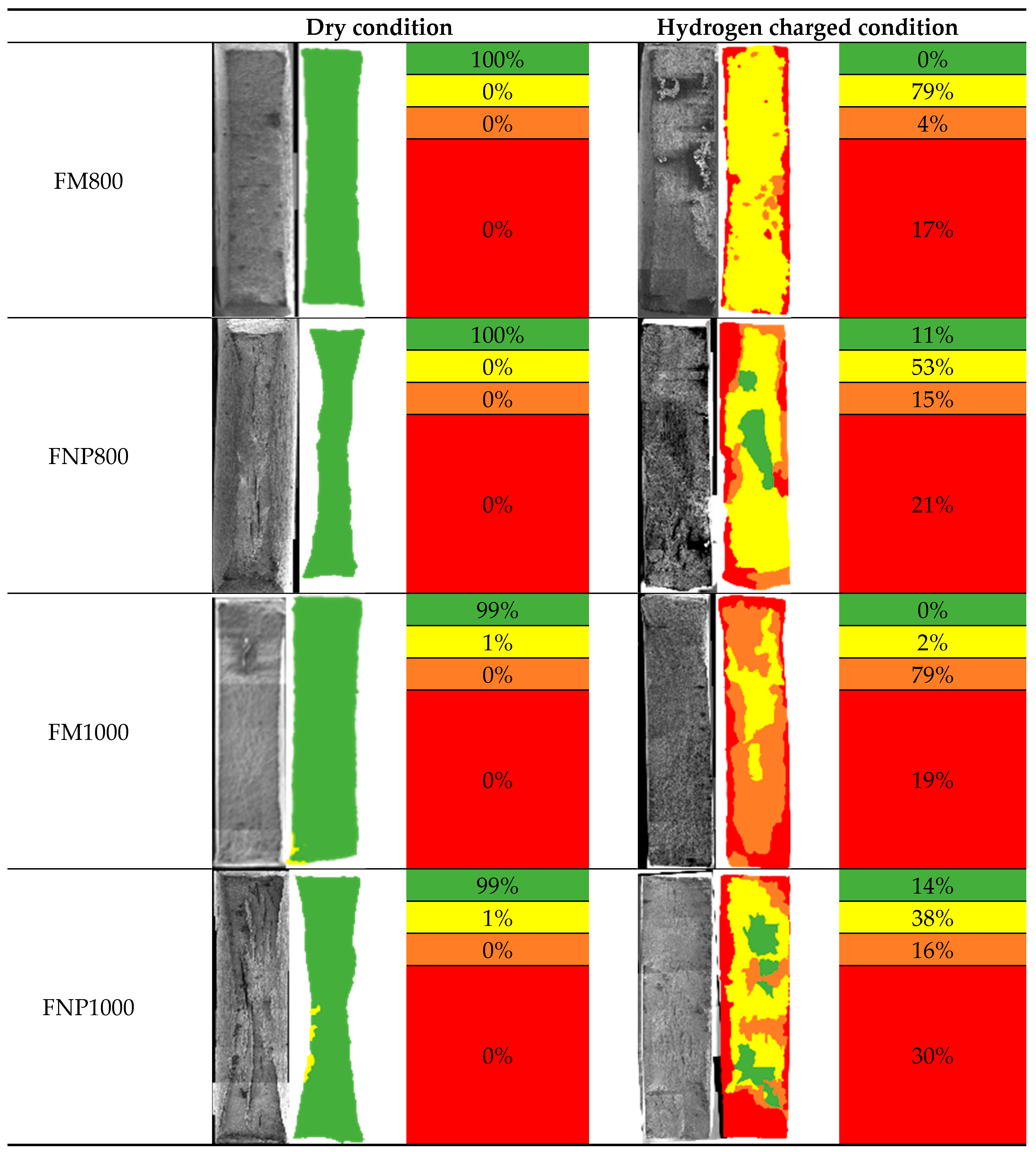

Evidence for these mechanisms in the FM AHSS can be found in the fractographic analysis. Fracture surface features, categorised and assigned colours according to the logic described in

Figure 6, are summarised in

Table 4. For all specimens tested in the dry condition, virtually the entire surface shows the presence of micro-void coalescence (MVC), considered to be typical of plastic deformation. In contrast, regions with the highest hydrogen concentrations closest to the charging surfaces, widespread quasi-cleavage (QC) and intergranular cracking (IG), both indicative of a decohesion initiation and propagation. Regions further from the charging surfaces there is still the presence of (MVC), but with widespread trans-granular (TG) cracks.

Brittle fracture features are more prevalent in the FM steel than the FNP steels of equivalent strength levels, with increased visible damage near the charging surfaces. There is a greater prevalence of visible damage towards the specimen centres and comparatively more widespread transverse cracks, contributing to FM1000 showing nearly 100% prevalence of brittle features. In the most severely embrittled FM1000, QC facets are still apparent even at the very centre of the specimen. However, the presence of TG cracks and MVC in regions also containing QC might suggest that hydrogen may be lowering the critical stress for dislocation motion, proposed in the HELP mechanism [

40].

Mixed modes of fracture are also observed in the single-phase FNP steels, but not to the extent observed in the FM steels. With EI of 32% and 44% for FNP800 and FNP1000 respectively, typically brittle fracture features covered up to 36% and 46% respectively. However, only at the regions adjacent to the charging surfaces where hydrogen concentrations are at a maximum, are features such as QC and IG prevalent, in stark contrast to the equivalent FM specimens. Differences in embrittlement index and fracture features observed between FNPs and FMs steels are a clear indication of the inherently better performance of the FNP microstructure in presence of hydrogen. These differences in resistance to degradation do not result exclusively from lower effective diffusivity per se, but from a combination of lower local diffusivity through presence of strong traps and the fully-ferritic microstructure being inherently more resilient than the dual-phase microstructure containing martensite. In other words, there are differences in critical hydrogen concentration between the two microstructures.

4. Conclusions

SVET scans carried out have shown that hydrogen evolution due to galvanic corrosion takes place on the steel substrate when the Zn sacrificial coating becomes damage in 0.1 M NaCl solution. The measured current density at the most strongly cathodic regions was equivalent to that for potentiostatic charging at -1050 mV (SCE) in a 3.5% NaCl + 3g/L NH4SCN solution used for both the hydrogen permeation and slow strain-rate tests.

Hydrogen permeation test have shown that FNP AHSS have lower effective diffusion coefficients, Deff, than FM AHSS of equivalent strength level. At 800 MPa strength level The mean Deff were 1.68×10-7 cm2/s for the FNP800, and 1.87×10-7 cm2/s for the FM800. At higher strength levels, 1000 MPa, Deff was 7.45×10-8 cm2/s for the FNP1000 and 1.45×10-7 cm2/s for the FM1000, respectively. FNP1000 lower Deff values are attributed to the high density of micro-alloyed carbide nanoprecipitates that behave like irreversible hydrogen traps. This was shown in the permeation curves deviations from simulated lattice diffusion curves where the breakthrough time, tb, were much longer that those for the modelled Fick’s equation.

For a given strength level, FNP AHSS were substantially more resistant to hydrogen embrittlement than conventional FM AHSS. The FNP800 and FNP1000 showed embrittlement indices of 32% and 44%, respectively. Whereas, FM800 and FM1000 had embrittlement indices of 50% and 76%, respectively, under the same conditions. These differences in susceptibility are attributed to the lower diffusivity found in FNP steels. For higher diffusivity there is increased susceptibility to hydrogen embrittlement for both FNP and FM AHSS.

Author Contributions

James Lelliott: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Project administration; Elizabeth Sackett: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition; H.N. McMurray: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision; D. Figueroa-Gordon: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in FigShare at DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.30305026.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support provided by Swansea University’s M2A that has been made possible through funding from the European Social Fund via the Welsh Government.

The authors would also like to acknowledge the support of Tata Steel Europe.

Finally, we would like to acknowledge the assistance provided by the Swansea University AIM Facility, which was funded in part by the EPSRC (EP/M028267/1), the European Regional Development Fund through the Welsh Government (80708), and the Ser Solar project via the Welsh Government.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

Where abbreviations are utilized in this manuscript, they are defined within the text upon first use.

References

- J.A. Lelliott, Hydrogen Embrittlement of Automotive Ultra-High-Strength Steels: Mechanism and Minimisation, Doctor of Engineering, Swansea University, Swansea, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Kuziak, R. Kawalla, S. Waengler, Advanced high strength steels for automotive industry, Archives of Civil and Mechanical Engineering. 2008, 8, 103–117. [CrossRef]

- C.T. Broek, FutureSteelVehicle: leading edge innovation for steel body structures, Ironmaking & Steelmaking. 2013, 39, 477–492. [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EU) No 333/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 March 2014 Amending Regulation (EC) No 443/2009 to Define the Modalities for Reaching the 2020 Target to Reduce CO2 Emissions from New Passenger Cars, Official Journal of the European Union 2014.

- C.M. Tamarelli, AHSS 101: the evolving use of advanced high strength steels for automotive applications, 2011, Autosteel, 2011.

- R.L. Higginson, C.M. R.L. Higginson, C.M. Sellars, Worked examples in quantitative metallography, Maney Pub, 2003.

- A. Kumar, S.B. Singh, K.K. Ray, Influence of bainite/martensite-content on the tensile properties of low carbon dual-phase steels, Materials Science and Engineering: A. 2008, 474, 270–282. [CrossRef]

- D. Katundi, A. Tosun-Bayraktar, E. Bayraktar, D. Toueix, Corrosion behaviour of the welded steel sheets used in automotive industry, Journal of Achievements in Materials and Manufacturing Engineering. 2010, 38, www.journalamme.org.

- G. Chalaftris, M.J. Robinson, Hydrogen re-embrittlement of high strength steel by corrosion of cadmium and aluminium based sacrificial coatings, Corrosion Engineering Science and Technology. 2005, 40, 28–32. [CrossRef]

- J. Bockris, J. McBreen, L. Nanis, The Hydrogen Evolution Kinetics and Hydrogen Entry into α-Iron, J Electrochem Soc. 1965, 112, 1025–1031.

- G. Williams, H.N. McMurray, Localized corrosion of magnesium in chloride-containing electrolyte studied by a scanning vibrating electrode technique, J Electrochem Soc. 2008, 155, C340–C349.

- H.N. Mcmurray, D. Williams, D.A. Worsley, Artifacts Induced by Large-Amplitude Probe Vibrations in Localized Corrosion Measured by SVET, J Electrochem Soc. 2003, 150, 12–567. [CrossRef]

- H.K.D.H. Bhadeshia, Prevention of Hydrogen Embrittlement in Steels, ISIJ International. 2016, 56, 24–36. [CrossRef]

- C.D. Beachem, A new model for hydrogen-assisted cracking (hydrogen “embrittlement”), Metallurgical Transactions. 1972, 3, 441–455.

- I.M. Robertson, P. Sofronis, A. Nagao, M.L. Martin, S. Wang, D.W. Gross, K.E. Nygren, Hydrogen Embrittlement Understood, Metallurgical and Materials Transactions B. 2015, 46, 1085–1103. [CrossRef]

- W.H. Johnson, On some remarkable changes produced in iron and steel by the action of hydrogen and acids, Nature. 1875, 11, 393. [CrossRef]

- M.A. V Devanathan, Z. Stachurski, The adsorption and diffusion of electrolytic hydrogen in palladium, Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A. 1962, 270, 90–102.

- S. Meister, Grain and particle analysis with line intersection method, Software, 2012, https://uk.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/35203-grain-and-particle-analysis-with-line-intersection-method.

- E. Frank, M.A. Hall, I.H. Witten, The WEKA Workbench, Online Appendix for “Data Mining: Practical Machine Learning Tools and Techniques”, 4th Edn. Morgan Kaufman, Burlington 2009.

- A. Saai, O.S. Hopperstad, Y. Granbom, O.G. Lademo, Influence of Volume Fraction and Distribution of Martensite Phase on the Strain Localization in Dual Phase Steels, Procedia Materials Science. 2014, 3, 900–905. [CrossRef]

- Y. Bergström, Y. Granbom, D. Sterkenburg, A Dislocation-Based Theory for the Deformation Hardening Behavior of DP Steels: Impact of Martensite Content and Ferrite Grain Size, Journal of Metallurgy 2010, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- J. Sullivan, N. Cooze, C. Gallagher, T. Lewis, T. Prosek, D. Thierry, In-situ monitoring of corrosion mechanisms and phosphate inhibitor surface deposition during corrosion of Zinc Magnesium Aluminium (ZMA) alloys using novel time-lapse microscopy, Faraday Discuss 180 2015, 361–379. http://rsc.li/fd-upcoming-meetings (accessed July 14, 2020).

- B.S. Institute, BS EN ISO 17081:2014. Method of measurement of hydrogen permeation and determination of hydrogen uptake and transport in metals by an electrochemical technique, 2014.

- D. Figueroa, M.J. Robinson, Hydrogen transport and embrittlement in 300 M and AerMet100 ultra high strength steels, Corros Sci. 2010, 52, 1593–1602. [CrossRef]

- M.J. Robinson, R.M. Sharp, The Effect of Post-Exposure Heat Treatment on the Hydrogen Embrittlement of High Carbon Steel, Corrosion. 1985, 41, 582–586. [CrossRef]

- E. Akiyama, S. Li, Electrochemical hydrogen permeation tests under galvanostatic hydrogen charging conditions conventionally used for hydrogen embrittlement study, Corrosion Reviews. 2016, 34, 103–112.

- L. Lan, X. Kong, Z. Hu, C. Qiu, D. Zhao, L. Du, Hydrogen permeation behavior in relation to microstructural evolution of low carbon bainitic steel weldments, Corros Sci. 2016, 112, 180–193. [CrossRef]

- E. Van den Eeckhout, T. Depover, K. Verbeken, The Effect of Microstructural Characteristics on the Hydrogen Permeation Transient in Quenched and Tempered Martensitic Alloys, Metals (Basel). 2018, 8. [CrossRef]

- M. Dadfarnia, P. Sofronis, T. Neeraj, Hydrogen interaction with multiple traps: Can it be used to mitigate embrittlement?, Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2011, 36, 10141–10148. [CrossRef]

- [M. Iino, Trapping of hydrogen by sulfur-associated defects in steel, Metallurgical Transactions A. 1985, 16, 401–409.

- A. Rijkenberg, A. Blowey, P. Bellina, C. Wooffindin, Advanced High Stretch-Flange Formability Steels for Chassis & Suspension Applications, in: Conf. on Steels in Cars and Trucks, 2014: pp. 426–433.

- T. Depover, K. Verbeken, The effect of TiC on the hydrogen induced ductility loss and trapping behavior of Fe-C-Ti alloys, Corros Sci. 2016, 112, 308–326. [CrossRef]

- T. Depover, O. Monbaliu, E. Wallaert, K. Verbeken, Effect of Ti, Mo and Cr based precipitates on the hydrogen trapping and embrittlement of Fe–C–X Q&T alloys, Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2015, 40, 16977–16984. [CrossRef]

- T. Depover, A. Laureys, D. Perez Escobar, E. Van den Eeckhout, E. Wallaert, K. Verbeken, Understanding the Interaction between a Steel Microstructure and Hydrogen, Materials (Basel). 2018, 11. [CrossRef]

- J. Lee, T. Lee, Y.J. Kwon, D.-J. Mun, J.-Y. Yoo, C.S. Lee, Effects of vanadium carbides on hydrogen embrittlement of tempered martensitic steel, Metals and Materials International. 2016, 22, 364–372. [CrossRef]

- T. Maki, 2 - Morphology and substructure of martensite in steels, in: E. Pereloma, D. V Edmonds (Eds.), Phase Transformations in Steels, Woodhead Publishing, 2012: pp. 34–58. [CrossRef]

- K. Takai, J. Seki, Y. Homma, Observation of Trapping Sites of Hydrogen and Deuterium in High-Strength Steels by Using Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry, Materials Transactions, JIM. 1995, 36, 1134–1139. [CrossRef]

- H. Hagi, Diffusion Coefficient of Hydrogen in Iron without Trapping by Dislocations and Impurities, Materials Transactions, JIM. 1994, 35, 112–117. [CrossRef]

- H. Hagi, Y. Hayashi, Effect of Dislocation Trapping on Hydrogen and Deuterium Diffusion in Iron., Transactions of the Japan Institute of Metals. 1987, 28, 368–374. [CrossRef]

- M. Koyama, C.C. Tasan, E. Akiyama, K. Tsuzaki, D. Raabe, Hydrogen-assisted decohesion and localized plasticity in dual-phase steel, Acta Mater. 2014, 70, 174–187. [CrossRef]

- K. Takashima, T. Nishimura, K. Yokoyama, Y. Funakawa, Role of Interface between Ferrite and Martensite in Hydrogen Embrittlement Behavior of Ultra-high Strength Dual-phase Steel Sheets, ISIJ International. 2019, 59, 1676–1682. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of hydrogen embrittlement of steels due to corrosion of a zinc sacrificial coating.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of hydrogen embrittlement of steels due to corrosion of a zinc sacrificial coating.

Figure 2.

SEM micrographs of a) FM800; b) FM1000, at 5000× magnification.

Figure 2.

SEM micrographs of a) FM800; b) FM1000, at 5000× magnification.

Figure 3.

SEM micrographs of a) FNP800; b) FNP1000, at 5000x magnification.

Figure 3.

SEM micrographs of a) FNP800; b) FNP1000, at 5000x magnification.

Figure 4.

Schematics of the Scanning Vibrating Electrode Technique, SVET (adapted from [

11]).

Figure 4.

Schematics of the Scanning Vibrating Electrode Technique, SVET (adapted from [

11]).

Figure 5.

Schematic of Devanathan-Stachurski permeation cell setup.

Figure 5.

Schematic of Devanathan-Stachurski permeation cell setup.

Figure 6.

Classification of fracture surface features.

Figure 6.

Classification of fracture surface features.

Figure 7.

SVET contour plot of a galvanised steel sample with coating partially damaged to expose the steel substrate, with the corresponding optical image. Contour plot shows scan taken at time = 0, 14, and 24 hours immersion in 0.1 M NaCl solutions. Contour lines displayed every ±0.25 A/m2 current density.

Figure 7.

SVET contour plot of a galvanised steel sample with coating partially damaged to expose the steel substrate, with the corresponding optical image. Contour plot shows scan taken at time = 0, 14, and 24 hours immersion in 0.1 M NaCl solutions. Contour lines displayed every ±0.25 A/m2 current density.

Figure 8.

The area-averaged anodic and cathodic current densities, Ia and Ic, respectively. Left - Area-averaged anodic current density over 24 hours; Right - area-averaged cathodic current density over 24 hours.

Figure 8.

The area-averaged anodic and cathodic current densities, Ia and Ic, respectively. Left - Area-averaged anodic current density over 24 hours; Right - area-averaged cathodic current density over 24 hours.

Figure 9.

Estimated hydrogen evolution over the duration of the experiment.

Figure 9.

Estimated hydrogen evolution over the duration of the experiment.

Figure 10.

Hydrogen permeation flux (solid line) for left: FM800 and right: FNP800 membranes with 0.8 mm nominal thickness, charged at -1050 mV (SCE) in 3.5% NaCl + 3 g/L NH4SCN.

Figure 10.

Hydrogen permeation flux (solid line) for left: FM800 and right: FNP800 membranes with 0.8 mm nominal thickness, charged at -1050 mV (SCE) in 3.5% NaCl + 3 g/L NH4SCN.

Figure 11.

Hydrogen permeation flux (solid line) for left: FM1000 and right: FNP1000 membranes with 0.8 mm nominal thickness, charged at -1050 mV (SCE) in 3.5% NaCl + 3 g/L NH4SCN.

Figure 11.

Hydrogen permeation flux (solid line) for left: FM1000 and right: FNP1000 membranes with 0.8 mm nominal thickness, charged at -1050 mV (SCE) in 3.5% NaCl + 3 g/L NH4SCN.

Figure 12.

Calculated effective diffusion coefficient, Deff, compared to nominal tensile strength for the different microstructures.

Figure 12.

Calculated effective diffusion coefficient, Deff, compared to nominal tensile strength for the different microstructures.

Figure 13.

Normalised hydrogen permeation curves for left: 800 MPa, and right: 1000 MPa tensile strength steels, respectively.

Figure 13.

Normalised hydrogen permeation curves for left: 800 MPa, and right: 1000 MPa tensile strength steels, respectively.

Figure 14.

Engineering stress-elongation curves for slow strain-rate tests for FM800 under each condition.

Figure 14.

Engineering stress-elongation curves for slow strain-rate tests for FM800 under each condition.

Figure 15.

Simplified Weibull plots for FM800 slow strain-rate tests, showing differences in ‘survival’ times for the test specimens. Changes in gradient reflect the range of times that a FM800 specimen could be expected to ‘survive’ under the specified test conditions.

Figure 15.

Simplified Weibull plots for FM800 slow strain-rate tests, showing differences in ‘survival’ times for the test specimens. Changes in gradient reflect the range of times that a FM800 specimen could be expected to ‘survive’ under the specified test conditions.

Figure 16.

Left: SSRT stress-elongation curves for FNP800 for the different charging conditions; right: simplified Weibull plots showing differences in survival times for FNP800.

Figure 16.

Left: SSRT stress-elongation curves for FNP800 for the different charging conditions; right: simplified Weibull plots showing differences in survival times for FNP800.

Figure 17.

Left: SSRT stress-elongation curves for FM1000 for the different charging conditions; right: simplified Weibull plots showing differences in survival times for FM1000.

Figure 17.

Left: SSRT stress-elongation curves for FM1000 for the different charging conditions; right: simplified Weibull plots showing differences in survival times for FM1000.

Figure 18.

Left: SSRT stress-elongation curves for FNP1000 for the different charging conditions; right: simplified Weibull plots showing differences in survival times for FNP1000.

Figure 18.

Left: SSRT stress-elongation curves for FNP1000 for the different charging conditions; right: simplified Weibull plots showing differences in survival times for FNP1000.

Figure 19.

Embrittlement indices (bars, left y-axis) with overlaid effective diffusion coefficients (diamonds, right y-axis) of the steels in this study.

Figure 19.

Embrittlement indices (bars, left y-axis) with overlaid effective diffusion coefficients (diamonds, right y-axis) of the steels in this study.

Table 1.

Alloy chemistry for the steels studied in this work (figures in mass-percent).

Table 1.

Alloy chemistry for the steels studied in this work (figures in mass-percent).

| Steel |

C |

Si |

Mn |

Cr |

Mo |

Nb |

Ti |

V |

B |

| FM800 |

0.136 |

0.236 |

1.692 |

0.553 |

0.003 |

0.024 |

0.021 |

0.003 |

0.0002 |

| FNP800 |

0.0611 |

0.189 |

1.373 |

0.016 |

0.141 |

0.061 |

0.002 |

0.212 |

0.0002 |

| FM1000 |

0.149 |

0.041 |

2.222 |

0.548 |

0.005 |

0.014 |

0.026 |

0.006 |

0.0001 |

| FNP1000 |

0.1037 |

0.201 |

1.396 |

0.023 |

0.292 |

0.05 |

0.003 |

0.286 |

0.0002 |

Table 2.

Baseline average mechanical properties of the studied steels.

Table 2.

Baseline average mechanical properties of the studied steels.

| Product |

Rp0.2

[MPa] |

Rm

[MPa] |

Ag

[%] |

A50

[%] |

| FM800 |

488 (± 2) |

782 (± 4) |

12.5 (± 0.1) |

19.7 (± 0.3) |

| FNP800 |

747 (±12) |

826 (± 5) |

9.3 (± 0.3) |

17.2 (± 1.5) |

| FM1000 |

700 (± 5) |

1027 (± 9) |

7.8 (± 0.3) |

13.5 (± 0.4) |

| FNP1000 |

862 (± 8) |

982 (± 3) |

8.2 (± 0.1) |

16.7 (± 0.3) |

Table 3.

Mean embrittlement indices and output from Student's t-test for SSRTs. All t-tests based on time-to-failure in the pre-charged versus dry conditions.

Table 3.

Mean embrittlement indices and output from Student's t-test for SSRTs. All t-tests based on time-to-failure in the pre-charged versus dry conditions.

| Product |

Mean Embrittlement Index % |

t-statistic |

p-value |

Power |

|

| FM800 |

50.30% (± 3.5%) |

11.773 |

2.98×10-4

|

1 |

|

| FNP800 |

32.40% ( ±16.7%) |

2.168 |

0.096 |

0.38 |

|

| FM1000 |

75.60% (± 0.6%) |

66.706 |

3.03×10-7

|

1 |

|

| FNP1000 |

43.80% (± 11.5%) |

5.186 |

6.58×10-3

|

0.97 |

|

Table 4.

Surface feature classification within fractured SSRT specimens.

Table 4.

Surface feature classification within fractured SSRT specimens.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).