1. Introduction

Over two years, from 2021 to 2022, electric motor vehicle usage in Indonesia increased 15-fold. The electric motor opportunity in Indonesia is estimated to reach USD 19.2 billion or around IDR 294 trillion from both a manufacturer and energy distribution point of view. The Indonesian government targets 13.5 million electric motorbikes out of 15.7 by 2030. The shift to electric motor vehicle mobility addresses urban mobility challenges and contributes to environmental sustainability [

1]. The number of electric motor vehicle Brand Holder Agents in Indonesia proliferates based on data from the Indonesian Electric Motorbike Industry Association. The growth also aligns with the country's increasing number of electric motor vehicle sales. Until 2023, there are 52 Brand Holder Agents in Indonesia from 2019. The electric motor vehicle Selis brand occupied the first position as the respondent's choice of electric motor vehicle at 22.33 percent. In second place is the Gesits brand, with a percentage reaching 17.83 percent. They were then followed by Uwinfly and Volta with 15.62 percent and 14.69 percent, respectively. At the bottom were the Gogoro brand with 3.97 percent, NIU with 6.09 percent, and ECGO with 7.20 percent. The Alva One electric bike recorded a share of 12.27 percent. All parties must contribute to reducing carbon emissions, which has been discussed globally. Therefore, transitioning to electric motor vehicles is one of the solutions to improve environmental conditions [

2].

The urgency of this research is that despite the variety of electric motor vehicle brands, Indonesian consumers still lack the decision to purchase electric motor vehicles. The shift to electric motor vehicle mobility addresses urban mobility challenges and contributes to environmental sustainability. This is also supported by the Government of Indonesia's roadmap for developing Battery Electric Motorised Vehicles, which aims to achieve electric motor vehicle adoption targets and support Sustainable Development Goal 7.

This research aims to analyze the driving factors that influence consumers to make purchasing decisions for EMV products. Analyzing these driving factors will provide a broad understanding of the theories that can explain the phenomenon of EMV purchases. In addition, the practical implications will strengthen business actors in making the right strategic decisions to support EMV sales performance optimally. Previous research has analyzed EMV products using several theoretical approaches and research models. Research related to the analysis of design values and hedonism, security attributes, and safety values affects the purchase intention of electric vehicles [

3,

4] Other research also analyses self-image congruence and attitude-willingness towards electric car products as environmentally friendly products [

5]; millennial green consumers in India and China [

6]; the role of government and social pressure on green product purchase [

7]; private car [

8]; the evolution of EMVs over time [

9]; and religious and ethical consideration [

10].

In addition to several studies on environment-based product selection, previous studies have also attempted to use theoretical approaches to analyze product selection. The Value Belief Norm theory in the context of Pakistani culture and eco-socially conscious consumer behavior, namely using vehicles with alternative fuel was analyzed [

11]. Another study examined Generation Z's decision-making by applying the Theory of Planned Behavior to understand consumer behavior. These findings can help practitioners determine effective marketing strategies to persuade Generation Z to act ethically [

12]. Another study analyzed the issue of diverse consumer emotions toward products by modifying the Theory of Planned Behavior [

13]. The model analyzes the environment of concern, attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control that are perceived to shape consumer intentions. Another study also analyzed the theoretical framework based on the theory of planned behavior (TPB), the technology acceptance model (TAM), and the theory of diffusion of innovation [

14].

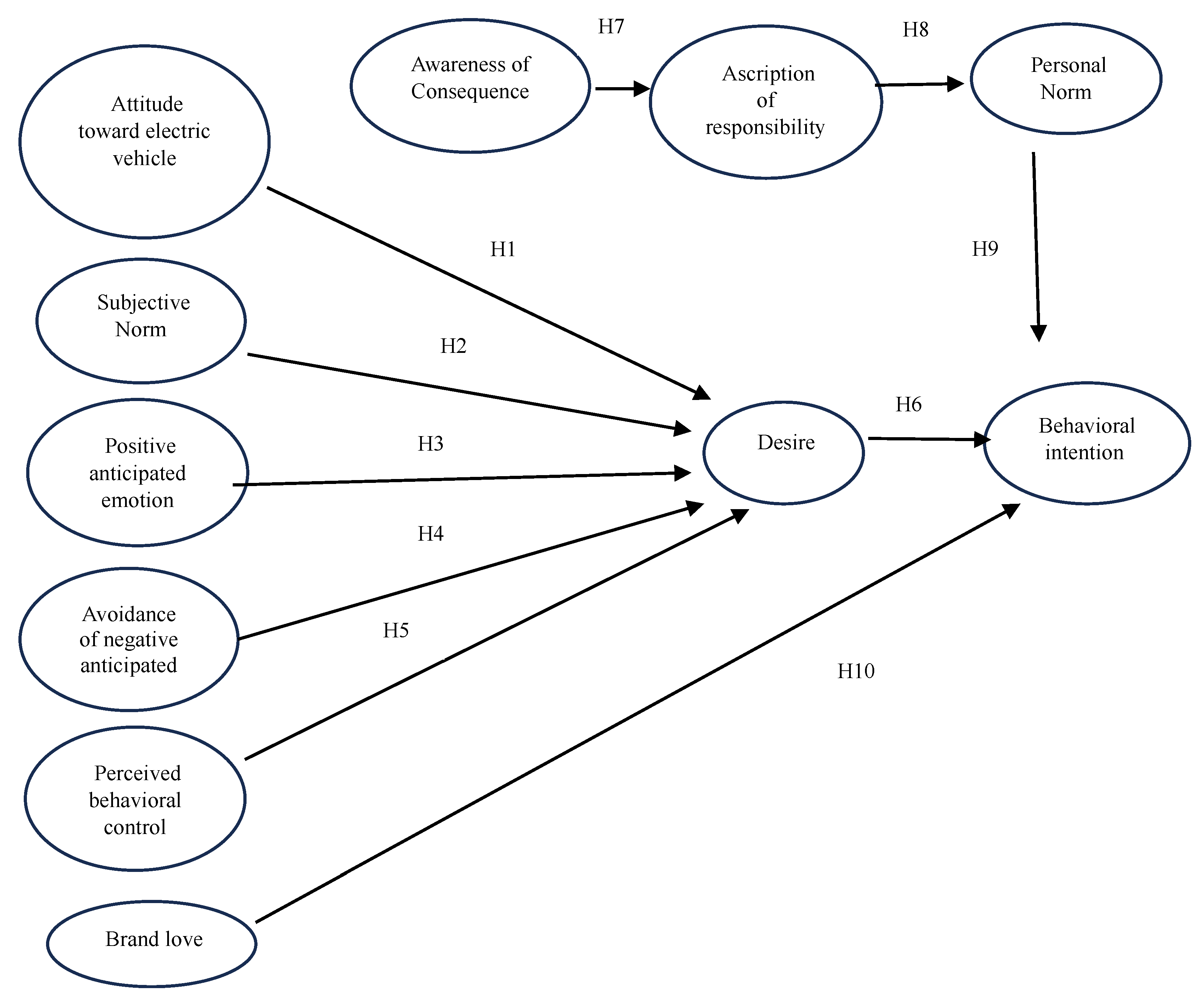

This research analyses EMV with an eclectic approach through Goal-Directed Behaviour Theory (GDB) and Norm Activation Theory (NAT) as the newness of the research. This research uses an eclectic approach through Goal-Directed Behaviour Theory (GDB) and Norm Activation Theory (NAT) as a novelty in EMV decision-making. It could fill the theoretical aspect of consumer behavior. EMV purchase decisions are considered social behavior and are complex decisions. GDB theory extends the TPB model by considering emotional factors while modifying behavioral influences. It can identify the cognitive and affective factors that motivate EMV purchase desire, intention, and behavior. Associated with NAT, which includes personal norms, moral obligations, and emotional responses, can explain EMV purchases.

Firstly, this research analyses GDB and NAT as goal-directed behavior models on complex social behaviors, including EMV purchase decision-making. GDB model extends the planned behavior model to include emotional factors [

15] while modifying behavioral influences. The contribution of this model lies in its ability to identify cognitive and affective factors that motivate desires, intentions, and subsequent behavior. GDB deepens the Theory of Planned Behaviour by stating that intentions are driven by desires and goals that transform the content of attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavior control into intentions to act. Anticipated emotions - positive and negative extend the theory by introducing new decision criteria that determine a person's goals as expressed by their desires. The frequency of past behavior incorporates the automatic aspect of directed behavior. The model has been applied to several studies on social marketing [

16]; mobile device usage [

17]; online sport [

18]; health behavior [

19]; crowdfunding [

20]; mutual investment [

21]; volunteer traveling [

22]; climate change [

23]; and sustainable behavior [

24]; and counterfeit consumption [

25].

Secondly, this research model uses NAT by considering environmental behavior related to EMV purchases influenced by ethical considerations, personal values, and practical considerations, namely the costs and benefits of specific actions. EMV purchase decision-making does not only pay attention to aspects of the subjective norms as a social norm but also the personal norms. NAT was initially developed to understand various types of prosocial or altruistic behavior. This theory describes the relationship between activators, personal norms, and behavior. Research has shown that factors related to the personal norm, moral obligation, and emotional response - which are the main components of NAT - can play a role in influencing behaviors related to environmental protection [

26]; environmental complaints [

27]; electric vehicle in China [

28]; social networking site [

29]; shopping bag [

30]; environmentally sustainable behavior [

31].

Thirdly, this study also aims to integrate the GDB and NAT theories and place brand love as a moderating variable between behavioral intention and behavior. Brand love becomes its power to strengthen decision-making. Brand love can be a moderating variable between mutually reinforcing or weakening [

32]. A brand connection matrix was developed that explains the relationship between feelings for the brand and the strength of the brand relationship. Brand love explains a strong brand relationship and strong emotional feelings for the brand. Brand love can strengthen the relationship between behavioral intention and behavior in EMV decision-making [

33].

Analyzing these factors will provide a broad understanding of theories that can explain the EMV purchase phenomenon more comprehensively. In addition, the practical implications will strengthen businesses' ability to formulate strategies. Based on the problem formulation above, the research objectives are:

RQ1. How is the implementation of GDB theory in the decision-making of EMVs?

RQ2. How is the implementation of NAT in the decision-making of EMVs?

RQ3. What is the role of brand love EMV in the model by combining GDB and NAT?

Literature Review

A person weighs the reasons for action, which results in the intention to achieve goals, and this is the thought process they go through. Goal setting is the deliberative processes one goes through in weighing reasons for acting, which culminates in a goal intention. Goal intentions connect the stages of goal-setting and goal-achievement. Customers must transform their goal intention into action [

34]. Goal-directed behavior posits that desire provides the direct impetus for intentions and transforms the motivational content to act embedded in attitudes towards the act, positive anticipated emotions, and avoidance of positive anticipated emotions, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Desire is a core psychological component influencing corresponding and decision-related intentions [

35].

In addition, attitudes towards the act based on positive beliefs about an object or product can influence a person's desire. If a person believes a product offers significant advantages, they may want to own it. Attitude toward the behavior is assumed to be a function of readily accessible beliefs regarding the behavior's likely consequences, termed behavioral beliefs as the person's subjective probability that performing a behavior of interest will lead to a certain outcome [

36]. A positive attitude towards an object or product can create a desire to own it [

5,

15,

16]. Feelings of pleasure or satisfaction associated with the object can generate a desire to get more or keep the positive experience of the selection.

H1: Attitude toward electric motor vehicle influences desire positively.

Subjective norms include societal pressure to act or not act and the profound impact of significant individuals and groups in an individual's life. A person's social pressure to engage in or refrain from particular activities is called a subjective norm [

15]. It describes how influential individuals or organizations affect people and the pressure they feel from society to behave or not act [

16]. Subjective norms are based on solid normative beliefs about consumers' desire to have electric motor vehicles and take these actions.

H2: Subjective norm influences desire positively.

Another component of Goal-Directed Behavior is positive anticipated emotions and negative anticipated emotion . Positive anticipated emotions and negative anticipated emotion can explain intentions [

37]. When an individual succeeds in achieving their goal, positive anticipated emotions is triggered, while negative anticipated emotion arises when a failure occurs. Behavioral intention is the willingness to perform a specific behavior, so positive anticipated emotions and negative anticipated emotions significantly influence the desire to perform or not to perform the behavior. In the environment of sustainable activities, empirical studies reveal the critical role of emotions in sustainable behavior [

23]. This study explains that positive anticipated emotions in electric motor vehicles will strengthen consumer desire. Consumers perceive that the presence of positive anticipated emotions will strengthen their desire to own electric motor vehicles. Regarding negative anticipated emotion, this shows the affective response in making electric motor vehicle purchase decisions that consumers avoid making the wrong decision. Consumers try to avoid negative anticipated emotions, which in turn will strengthen the desire to purchase electric motor vehicle.

H3: Positive anticipated emotion influences desire positively.

H4: The avoidance of negative anticipated emotion influences desire positively.

Perceived behavioral control leads to intentions to act and is a product of control beliefs, control over resources, ability, and confidence in action. Perceived behavioral control can influence behavior directly and indirectly through intention [

21]. Perceived behavioral control is related to one's perception of how much power and ability consumers have when making electric motor vehicle transactions. A person's desire for an electric motor vehicle buy may grow if they believe they can complete the action or fulfill their desire [

38]. The individuals’ intention (behavioral intention-BI) to perform a particular behavior is primarily motivated by how they want to perform the behavior (i.e. desire), and attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and positive and negative anticipated emotions determine their desire. Moreover, past behavior or habits are assumed to be a significant predictor of desire, intention, and actual behaviors.

H5: Perceived behavioral control influences desire positively.

A model that overcomes the shortcomings of the Theory of Planned Behavior, frequently employed in consumer behavior studies, is called Norm Activation Theory. Norm Activation Theory is composed of three parts. Personal norm comes first. This study uses norm activation theory, which examines subjective norms as societal and individual norms, or personal norms, to predict behavioral intentions in electric motor vehicles. It was during a study on environmental friendliness that Schwartz first suggested Norm Activation Theory. When someone behaves ecologically unfriendly toward others or in specific circumstances, personal norm directly affects how others perceive unfavorable outcomes. Personal norm also alludes to the moral duty to engage in or abstain from particular activities [

39].

Second, awareness of consequences or taking responsibility for the unfavorable effects of not engaging in a way that promotes prosocial behavior is examined by Norm Activation Theory in addition to personal norms [

40]. Awareness of consequences shows that a person is conscious of the potential harm that could result from acting in a non-pro-social manner toward others. Thirdly, ascription of responsibility within the context of Norm Activation Theory also denotes a person's acceptance of personal accountability for the consequences of their non-environmental actions. Norm Activation Theory reveals an individual's expectations for particular actions. Ascription of responsibility is admitting accountability for the consequences of acting pro-socially.

Awareness of consequences and assigning blame may be the causes of personal norms [

26,

31]. Selecting electric motor vehicle products is a way to be conscious of the implications of the ascription of responsibility, which, in the end, promotes personal norms. Customers understand that using electric motor vehicle products is a personal norm and an obligation. People will take note while making decisions that benefit the environment. Customers who are conscious of the negative effects avoid purchasing environmentally harmful products. That is, norms are more likely to be robust and impact the creation of constructive behavior through product purchases when consumers pay attention to environmental needs and know that their actions can support environmental protection [

29,

30,

41]. A person will acquire a solid moral commitment to acting pro-socially if they feel responsible for their actions.

H6: Desire influences behavioral intention positively.

H7: Awareness of consequence influences the ascription of responsibility.

H8: Ascription of responsibility influences personal norms.

H9: Personal norm influences behavioral intention

Brand love is the critical aspect for explaining the behavioral intention of certain decisions. Brand love as the degree of passionate, emotional attachment a satisfied consumer has for a particular trade name, including passion for the brand, attachment to the brand, positive evaluation of the brand, positive emotions in response to the brand, and declarations of love for the brand [

42]. Consumers' favorable attitudes toward a brand are explained by brand love, which leads to pro-brand behavior and ultimately motivates them to spread the information through WOM [

43,

44]. Additionally, this requirement develops brand loyalty in customers and assists them in avoiding unfavorable information about the company. Customers will try to determine whether the favored brand's marketing plan contains any errors. Consumers' intention to drive electric motor vehicles depends on their brand love, and their desire to buy electric motor vehicle products influences their behavioral intention. In this case, brand love amplifies its impact on behavioral intention.

H10: Brand love influences behavioral intention.

2. Methodology

This research applied a deductive reasoning-based design for theory testing. It aims to test theory-based hypotheses from various literature sources [

45]. The procedures of the research were as follows. Firstly, the study determined the participants that were young consumers who had experience purchasing motor vehicles and became respondents to this study through convenience sampling in Jakarta, Indonesia. Secondly, The study determined DKI Jakarta as the main location to conduct the study. According to Databoks, Jakarta is one of the cities with a large population of electric motorbike users [

46]. The majority of electric motorized vehicles are motorbikes. In DKI Jakarta, the number reached 1,092 vehicles recorded at Polda Metro Jaya. The intention to drive electric motor vehicle products is an effort to support SDG 7, "Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all." There are critical dimensions that need to be understood comprehensively. The concepts include energy affordability, reliability, sustainability, and modernity.

Thirdly, the researcher coordinated with the research assistant. The research used a questionnaire delivered in a Google Form with two research assistants who had received an explanation regarding assistance filling out the research survey. The research collected 354 samples, and 340 were eligible for the analysis. The city was Jakarta. The respondents were young customers, commonly classified as Millennials (born roughly between 1981 and 1996) and Generation Z (born approximately between 1997 and 2012), who constitute a sizable and unique market niche for electric motor vehicle and have a preference for trying electric motor vehicle based on the screening list in the questionnaire. They were especially open to sustainability and innovation since their views, values, and behaviors were formed by particular experiences and worldwide trends.

Fourthly, the research analyzed the data from respondents. Based on the distribution of data related to gender, they are divided as many as 73.5% female and 26.5% male. Regarding the level of education, the latest education level of Strata-1, as much as 83%, followed by respondents with an education level below Strata-1, as much as 10%; respondents with the latest education level of Strata-2 as much as 5%; the level of Strata-3 as much as 4%. Based on occupation, the dominance is professions 80%, teachers and lecturers 10%, entrepreneurs 6%, civil servants as much as 1%, and the remaining respondents answered others as much as 1.2%. The distribution based on age is known to be 18-30 years old, as much as 98%.

All instruments related to Goal-Directed Behavior were adopted from previous research [

47]. The measurement scale of attitudes towards the act (four indicators), subjective norms (four indicators), perceived behavioral control (four indicators), positive anticipated emotions (four indicators), negative anticipated emotion (three indicators), desire (three indicators), and behavioral intention (four indicators). The translation and reverse translation process is used in this investigation. Related to variable instruments, awareness of consequences has three indicators [

48]. AR has four indicators [

49], and personal norm has three indicators [

50]. The study used a seven-point Likert-based scale response (1=strongly disagree and 5=strongly agree).

This research employed a self-report study, so the common method bias was tested. When data for independent and dependent variables are collected using the same method, often simultaneously, it can artificially inflate or deflate the estimated relationships between variables using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) [

51]. This metric aims to quantitatively determine the degree to which the inflation of variance in coefficient estimates is attributable to correlations among predictor variables. All VIF values were below 5. SmartPLS 3.2.8 was utilized in this study to evaluate the hypotheses. The study's analysis has two parts: the measurement and structural models.

3. Results

This study developed a measurement model assessment. Researchers use the loading factor and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values to test convergent validity.

Table 2 shows two invalid indicators based on loading factor value: the PB 1 indicator of perceived behavioral control and the PN1 indicator of the personal norm. The AVE value of all constructs is ≥ 0.5. Cronbach's alpha value and Composite reliability value have values greater than 0.7. The test results can be summarised in

Table 2. Discriminant validity is tested using the Fornell - Larcker criterion [

52]. Based on the findings of Fornell-Larcker, every construct has a higher value than the others.

This study's investigation tested and validated a conceptual hypothesis through statistical analysis. Hypothesis testing is done to evaluate the statistical significance or interpretation of the observed influence. All findings presented in

Table 3 of this research are found to be supported through the examination of the collected data. H1 testing shows that attitudes towards the act influences desire positively (β = 0.287, t = 4.692, ρ < 0.001). H2 testing shows that subjective norms does not influence desire positively (β = 0.098, t = 1.330, ρ < 0.001), so H2 is rejected. H3 testing shows that positive anticipated emotions influences desire positively (β = 0.320, t = 3.549, ρ < 0.001). H3 testing shows that negative anticipated emotion influences desire positively (β = -0.117, t = 3.399, ρ < 0.001). H5 testing shows that perceived behavioral control does not influence desire positively (β = 0.141, t = 1.944, ρ < 0.001), so H5 is rejected. H6 testing shows that desire influences behavioral intention positively (β = 0.609, t = 9.704, ρ < 0.001). H7 testing shows that awareness of consequences influences ascription of responsibility positively (β = 0.573, t = 12.259, ρ < 0.001). H8 testing shows that ascription of responsibility influences personal norm positively (β = 0.474, t = 7.148, ρ < 0.001). H9 testing shows that personal norm influences behavioral intention positively (β = 0.105, t = 1.836, ρ < 0.001). H 10 testing shows that brand love influences behavioral intention positively (β = 0.636, t = 2.373, ρ < 0.001). The coefficient of determination (R

2) also assessed the structural model. Attitudes towards the act, subjective norms, positive anticipated emotions, avoidance of negative anticipated emotion, and perceived behavioral control explain 38.1 percent of the variation in desire brand love, desire, personal norm, and FRE explain 59.1 percent of the variation in behavioral intention. Awareness of consequences explains 32.8 percent of the variation in the ascription of responsibility, while ascription of responsibility explains 22.5 percent in personal norm.

4. Discussion

Previous research has analyzed electric motor vehicle purchase decisions using several theoretical approaches and research models. Previous research analyzed the design and hedonism values, safety attributes, and safety values influencing electric vehicle purchase intentions [

4] and religion [

10]. Several other studies used the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) to understand consumer decision-making in electric motor vehicle decisions [

13]. Other studies have used TAM and Innovation and diffusion theory to explore the key factors influencing electric motor vehicle purchases [

14,

47]. A key idea in psychology is goal-directed behavior theory, which emphasizes establishing and working toward particular goals to impact and drive behavior. Recognizing the significance of this theory can provide insightful information in electric motor vehicle decision-making. This theory can also guide decision-making processes by providing criteria for evaluating options and making choices that align with individuals' long-term objectives.

This study has found that attitudes towards the act of purchasing electric motor vehicle positively influences desire. Pleasure or satisfaction derived from the item may lead to a drive to obtain more or hold onto the good feeling from the purchase [

16]. Consumers who value sustainability and innovation will likely consider electric motor vehicle s worth the investment. Subjective norms did not positively influence desire. Interestingly, the authors' research defies accepted wisdom by showing that subjective norms have little effect on people's inclination to utilize electric motor vehicle. Individual norms might influence desire and behavioral intention of electric motor vehicle. This study also showed that positive anticipated emotions will bolster their desire for an electric motor vehicle. In terms of avoiding negative anticipated emotion, this illustrates the affective reaction that emerges when consumers make electric motor vehicle buying decisions to prevent them from choosing incorrectly. The authors' findings illustrate that positive anticipated emotions and the avoidance of negative anticipated emotions contribute positively to the desire to engage with electric motor vehicles. This aligns with the study of the adoption of streaming applications as a new technology [

37].

Perceived behavioral control did not influence desire. It addresses perceived barriers and enhances consumers' confidence in adopting electric motor vehicle by providing information and support. If a person feels capable of performing an action or fulfilling an electric motor vehicle purchase desire, this may increase their desire [

38]. This study also found that individuals with a stronger desire to purchase an electric vehicle are more likely to make such a purchase. behavioral intention was impacted by recurrent prior behavior.

This study also showed that each Norm Activation Theory variable influences the dependent variable. First, awareness of consequences influences the ascription of responsibility, which influences personal norms [

26,

47]. Awareness of consequences is a powerful driver of ascription of responsibility, influencing individuals to adopt behaviors that align with their moral and ethical standards. In marketing electric motor vehicles, leveraging this relationship can motivate consumers to switch to more sustainable transportation options. By raising awareness of traditional vehicles' environmental and social impacts and enhancing individuals' sense of responsibility, marketers can drive the adoption of electric motor vehicles, contributing to a more sustainable future.

Second, personal norm influences behavioral intention. The ascription of responsibility plays a pivotal role in influencing personal norms, which in turn guide behavior [

26,

47]. In marketing electric motor vehicles, leveraging this relationship can effectively motivate consumers to adopt more sustainable transportation options. By enhancing responsibility through personalized messaging, moral and ethical appeals, and empowerment initiatives, marketers can activate personal norms and drive the adoption of electric motor vehicles. This strategy supports more general environmental sustainability goals and is consistent with the beliefs of environmentally conscientious consumers. Related to brand love, it can influence behavioral intention [

53]. Brand love greatly influences the intention to purchase since it forges solid emotional bonds, encourages loyalty, and establishes credibility. Consumers who love a brand of electric motor vehicles are more emotionally engaged, significantly impacting their decision-making process.

5. Conclusions

The study aimed to analyze the implementation of Norm Activation Theory and Goal-Directed Behavior in the consumer's choice of an electric motor vehicle. This could close the theoretical gap in consumer behavior. Purchasing decisions for electric vehicles are seen as complicated social behaviors. The Goal-Directed Behavior hypothesis modifies behavioral influences while considering emotional aspects, extending the TPB paradigm. It can pinpoint the emotional and cognitive elements that drive electric motor vehicle buyers' intentions, desires, and actions. Norm Activation Theory, which encompasses moral commitments, emotional reactions, and personal conventions, is thought to be able to explain electric motor vehicle purchases.

This research is an initial contribution to analyzing electric motor vehicle decision-making that tends to be complex, with an eclectic approach to Goal-Directed Behavior and Norm Activation Theory reinforced by brand love. Based on research from previous researchers, the role of brand love becomes important when consumers face complex decision-making. Electric motor vehicle products are considered complex, so attention to diverse electric motor vehicle brands reinforces the critical role of brand love in making it easier for consumers to make decisions. The research is expected to support government policies and be part of the effort to reduce carbon emissions from transport. Goal-Directed Behavior theory explains the considerations that a person goes through to act. Behavior in Goal-Directed Behavior theory is motivated by behavioral intention and desire. Attitudes towards the act affect desire, which in turn affects behavioral intention. On the other hand, Norm Activation Theory explains the presence of ethical considerations and personal values in electric motor vehicle purchases. Norm Activation Theory consists of personal norm, awareness of consequences, and ascription of responsibility. Regarding brand love, this study confirms that the research model related to electric motor vehicles shows aspects of rationality when choosing a brand. Consumers also consider brand aspects as a basis for decision-making.

The decision to purchase electric motor vehicles is still limited among consumers in Indonesia despite the number of electric motor vehicle brands. The shift to electric motor vehicle mobility addresses urban mobility challenges and contributes to environmental sustainability. This is also supported by the Government of Indonesia's roadmap for developing Battery-Based Electric Vehicles, which aims to achieve electric motor vehicle adoption targets. An electric motor vehicle ecosystem is needed to reduce these pollutant conditions. The role of the government as a vital institution is needed to suppress the increase in air pollution [

7]. The Indonesian government has various decarbonization programs. This program aims to encourage the driving of electric motors and electric cars as a substitute for conventional vehicles that produce pollution.

Norm Activation Theory describes how personal norms are triggered and impact pro-social and pro-environmental conduct. Norm Activation Theory can be an effective marketing strategy for electric motor vehicle as goods with social or environmental impacts, as it can shape consumer behavior. A marketer of electric motor vehicle can inform consumers about the environmental and social impacts of their choices of electric motor vehicle. Highlighting the negative consequences of not adopting eco-friendly behaviors can increase awareness of the importance of electric motor vehicle. Driving electric motor vehicle goods is a step toward achieving SDG 7, which calls for universal access to modern, affordable, dependable, and sustainable energy.

The limitations of the methodology employed in this study allow for future research directions to be explored. The study's sample of young customers aged 18- 30 had distinct purchase considerations compared to other age groups, limiting the study's applicability to other age groups. A bigger sample size for cross-national investigation may help extrapolate the findings. Although the scales used in this study were taken from different sources, researchers can still employ qualitative techniques to identify the underlying factors impacting the environment and consumption, specifically designed to gauge the intention of electric motor vehicles.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Discriminant validity.

Table A1.

Discriminant validity.

| |

AC |

AR |

AT |

BI |

BL |

DS |

FB |

NA |

PA |

PB |

PN |

SN |

| AC |

0.825 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| AR |

0.573 |

0.840 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| AT |

0.555 |

0.507 |

0.861 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| BI |

0.491 |

0.537 |

0.500 |

0.875 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| BL |

0.521 |

0.488 |

0.519 |

0.459 |

0.810 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DS |

0.448 |

0.335 |

0.485 |

0.727 |

0.472 |

0.922 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FB |

0.258 |

0.332 |

0.278 |

0.505 |

0.265 |

0.407 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

| NA |

0.357 |

0.454 |

0.346 |

0.335 |

0.415 |

0.246 |

0.253 |

0.911 |

|

|

|

|

| PA |

0.454 |

0.484 |

0.560 |

0.571 |

0.608 |

0.529 |

0.280 |

0.500 |

0.886 |

|

|

|

| PB |

0.311 |

0.345 |

0.236 |

0.334 |

0.358 |

0.307 |

0.255 |

0.366 |

0.246 |

0.884 |

|

|

| PN |

0.361 |

0.474 |

0.456 |

0.313 |

0.354 |

0.236 |

0.280 |

0.296 |

0.391 |

0.258 |

0.956 |

|

| SN |

0.414 |

0.420 |

0.534 |

0.427 |

0.413 |

0,419 |

0.208 |

0.299 |

0.442 |

0.373 |

0.310 |

0.899 |

References

- Pristiandaru, D. L. (2023). Berkembang pesat, pengguna motor listrik meningkat 15 kali lipat dalam 2 tahun. Accessed https://lestari.kompas.com/read/2023/09/13/120000086/berkembang-pesat-pengguna-motor-listrik-meningkat-15-kali-lipat-dalam-2?page=all.

- Putri, A.A. (2023). Merek motor listrik yang paling banyak dimiliki masyarakat Indonesia. Goodstats.

- Morton, C., Anable, J. & Nelson, J.D. (2016). Assessing the importance of car meanings and attitudes in consumer EMValuations of electric vehicles. Energy Efficiency, 9 (2), 495–509. [CrossRef]

- Pimenta, M.L. & Piato, É.L. (2016). Cognitive relationships between automobile attributes and personal values, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 28 (5), 841–861. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R. & Vijaygopal, R. (2018). Consumer attitudes towards electric vehicles: Effects of product user stereotypes and self-image congruence. European Journal of Marketing, 52 (3/4), 499–527. [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, S. & Xue, F. (2016). Personal networks as a precursor to a green future: a study of “green” consumer socialization among young millennials from India and China. Young Consumers, 17 (3), 226–242. [CrossRef]

- Sreen, N., Yadav, R., Kumar, S. & Gleim, M. (2021). The impact of the institutional environment on green consumption in India. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 38 (1), 47–57. [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.A., Eagle, L. & Low, D. (2021). Determinants of eco-socially conscious consumer behavior toward alternative fuel vehicles, Journal of Consumer Marketing, 38 (2), 211–228. [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, F. (2023). Electric vehicles: benefits, challenges, and potential solutions for widespread adaptation. Applied Science, 13, 6016. [CrossRef]

- Klabi, F. & Binzafrah, F. (2023). Exploring the relationships between Islam, some personal values, environmental concern, and electric vehicle purchase intention: the case of Saudi Arabi. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 14, Iss. 2, 366-393. [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.A., Eagle, L., Yaseen, A. & Low, D. (2018). The power of spirituality: Exploring the effects of environmental values on eco-socially conscious consumer behaviour. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 30 (4), 867–888. [CrossRef]

- Djafarova, E. & Foots, S. (2022). Exploring ethical consumption of generation Z: theory of planned behaviour. Young Consumers, 23 (3), 413–431. [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, F., Parthiban, E.S., Rajkumari, Y., Adil, M., Nasir, M., & Dogra, N. (2024). From thinking green to riding green: A study on influencing factors in electric vehicle adoption. Sustainability, 16 (1), 194. [CrossRef]

- Tu, J.C. & Yang, C. (2019). Key factors influencing consumers’ purchase of electric vehicles. Sustainability, 11, 3863; [CrossRef]

- Perugini, M. & Bagozzi, R.P. (2001). The role of desires and anticipated emotions in goal-directed behaviours: broadening and deepening the theory of planned behaviour. British Journal of Social Psychology, Wiley Online Library, 40 (1), 79–98. [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, J., Russell-Bennett, R. & Previte, J. (2018). Challenging the planned behavior approach in social marketing: emotion and experience matter, European Journal of Marketing, 52 (3/4), 837–865. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J. & Preis, M.W. (2016). Why seniors use mobile devices: applying an extended model of goal-directed behavior. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, Taylor & Francis, 33 (3), 404–423. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, W., Kim, T. & Won, D. (2018). Predicting consumers’ intention to purchase sporting goods online: An application of the model of goal-directed behavior. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 30 (2), 333–351. [CrossRef]

- Esposito, G., van Bavel, R., Baranowski, T. & Duch-Brown, N. (2016). Applying the model of goal-directed behavior, including descriptive norms, to physical activity intentions: a contribution to improving the theory of planned behavior.Psychological Reports, 119 (1), 5–26. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J. & Hall, M. (2019). Co-creation and crowdfunding types predict funder behavior. An extended model of goal-directed behavior. Sustainability, 11 (24), 7061. [CrossRef]

- Sourirajan, S. & Perumandla, S. (2022). Do emotions, desires, and habits influence mutual fund investing? A study using the model of goal-directed behavior. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 40 (7), 1452–1476. [CrossRef]

- Meng, B., Chua, B.L., Ryu, H.B. & Han, H. (2020). Volunteer tourism (VT) traveler behavior: merging norm activation model and theory of planned behavior. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28 (12), 1947-1969. [CrossRef]

- Odou, P. & Schill, M. (2020). How anticipated emotions shape behavioral intentions to fight climate change, Journal of Business Research, 121, 243–253. [CrossRef]

- Han, H., Hwang, J. & Lee, S. (2017). Cognitive, affective, normative, and moral triggers of sustainable intentions among convention-goers. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 51, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Wu , G.J., Bagozzi, R.P., Anaza, N. & Yang, Z. (2019). A goal-directed interactionist perspective of counterfeit consumption: The role of perceived detection probability. European Journal of Marketing, 53 (7), 1311–1332. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Dai, J., Gao, W., Yao, X., Dewancker, B.J., Gao, J., Wang, Y., & Zeng, J. (2024). Achieving sustainable tourism: analysis of the impact of environmental education on tourists’ responsible behavior, Sustainability, 16, 552. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Liu, J. & Zhao, K. (2018). Antecedents of citizens’ environmental complaint intention in China: an empirical study based on norm activation model. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 134, July, 121–128. [CrossRef]

- He, X. & Zhan, W. (2018).How to activate moral norm to adopt electric vehicles in China? An empirical study based on extended norm activation theory. Journal of Cleaner Production, 172, January, 3546-3556. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-Y., & Fang, Y.-H. (2022). Go green, go social: exploring the antecedents of pro-environmental behaviors in social networking sites beyond norm activation theory. International Journal Environment Responsibility Public Health, 19 (21). [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.P.L. (2022). Intention and behavior toward bringing your own shopping bags in Vietnam: integrating theory of planned behavior and norm activation model. Journal of Social Marketing, 12 (4), 395–419. [CrossRef]

- Paswan, A., Guzmán, F. & Lewin, J. (2017). Attitudinal determinants of environmentally sustainable behavior. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 34 (5), 414–426. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Zhang, J. & Sakulsinlapakorn, K. (2020). Love becomes hate? or love is blind? Moderating effects of brand love upon consumers’ retaliation towards brand failure. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 30 (3), 415–432. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, T. & Moreira, M. (2019). Consumer brand engagement, satisfaction and brand loyalty: a comparative study between functional and emotional brand relationships., Journal of Product & Brand Management, 28 (2), 274–286. [CrossRef]

- Wu, G. J., Leung, A., Brown, J.U. & Park, P. (2016). A goal–setting and goal–striving model to better understand and control the weight of US ethnic group members. Journal of Research for Consumers, 29 (14).

- Vishwakarma, P. & Mohapatra, M.R. (2023). Unveiling consumer behavior in marketing: a meta-analytic structural equation modeling (Meta-SEM) of the model of goal-directed behavior (MGB). Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 41 (8), 1057–1092. [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (2020). The theory of planned behavior: frequently asked questions. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2 (4), 314–324. [CrossRef]

- Sahu, G., Singh, G., Singh, G. & Gaur, L. (2024). Exploring new dimensions in OTT consumption: an empirical study on perceived risks, descriptive norms and goal-directed behaviour. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics. [CrossRef]

- Liao Y-W, Su Z-Y, Huang C-W & Shadi R. 2019The Influence of environmental, social, and personal factors on the usage of the app “Environment Info Push”. Sustainability, 11 (21), 6059. [CrossRef]

- Abutaleb, S., El-Bassiouny, N.M. & Hamed, S. (2021). A conceptualization of the role of religiosity in online collaborative consumption behavior. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 12 (1), 180–198. [CrossRef]

- Jaini, A., Quoquab, F., Mohammad, J. & Hussin, N. (2020). I buy green products, do you…?”: The moderating effect of eWOM on green purchase behavior in Malaysian cosmetics industry. International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Healthcare Marketing, 14 (1), 89–112. [CrossRef]

- Esfahani, D.M., Ramayah, T. & Rahman, A.A. (2017). Moderating role of personal values on managers’ intention to adopt green is: Examining norm activation theory. Industrial Management and Data Systems, 117 (3), 582–604. [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B. A. & Ahuvia, A. C. (2006), Some antecedents and outcomes of brand Love, Marketing Letters, 17, 79–89. [CrossRef]

- Batra, R., Ahuvia, A. & Bagozzi, R.P. (2012). Brand love. Journal of Marketing, 76 (2), 1-16.

- Wallace, E., Buil, I. & de Chernatony, L. (2014). Consumer engagement with self-expressive brands: brand love and WOM outcome. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 23 (1), 33–42. [CrossRef]

- Akman, H., Plewa, C. & Conduit, J. (2018). Co-creating value in online innovation communities”, European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 53 No. 6. [CrossRef]

- Yoshio, A. (2021), Jumlah kendaraan bermotor listrik di Jadetabek. Accessed in https://databoks.katadata.co.id/datapublish/2021/05/19/ribuan-kendaraan-listrik-beredar-di-jalanan-ibu-kota.

- Meng, B. & Han, H. (2016). Effect of environmental perceptions on bicycle travelers’ decision-making process: developing an extended model of goal-directed behavior. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 21 (11), 1184–1197. [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.Y., Wong, Y.H. & Leung, T.K. (2008). Applying ethical concepts to the study of ‘green’ consumer behavior: an analysis of Chinese consumers’ intentions to bring their own shopping bags, Journal of Business Ethics, 79 (4), 469-481. [CrossRef]

- Ari, E. & Yilmaz, V. (2017), Consumer attitudes on the use of plastic and cloth bags, Environment, Development and Sustainability, 19 (4), 1219–1234. [CrossRef]

- Lam, S. & Chen, J. (2006). What makes consumers? Bring their bags or buy bags from the shop? A survey of consumers at a Taiwan hypermarket. Environment and Behavior, 38 (3), 318–332. [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M., MacKenzie, S.B., Lee, J.Y. & Podsakoff, N.P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88 (5), 879–903. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., Black, W. C., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate Data Analysis. 8th edition. Cengage Learning, United Kingdom.

- Meng, B., Lee, M.J., Chua, B.-L. & Han, H. (2022). An integrated framework of behavioral reasoning theory, theory of planned behavior, moral norm and emotions for fostering hospitality/tourism employees’ sustainable behaviors, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34 (12), 4516-4538. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).