1. Introduction

Female reproductive aging represents a paradigm of accelerated system-specific decline, with the ovary exhibiting the earliest and most noteworthy deterioration among all relevant organs (Wang et al., 2025). This biological phenomenon has profound implications for individual fertility, population demographics, and public health, particularly as women delay childbearing to more advanced ages. The traditional paradigm of reproductive aging has focused primarily on the quantitative decline in ovarian reserve with emphasis on follicular depletion and oocyte aneuploidy as primary drivers of fertility decline (Hirano et al., 2025). However, this model fails to sufficiently explain the complex, interconnected nature of ovarian aging processes or provide a unified framework for understanding the mechanistic basis of reproductive decline. Moreover, conventional approaches have been limited in their ability to identify actionable therapeutic targets for preserving reproductive function for extended periods.

Recent advances in reproductive biology have revealed that ovarian aging involves complex interactions between reactive species byproducts, mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammation, and metabolic disruption (Ju et al., 2025). These findings align remarkably well with the core principles of the Conglomerate Theory of Aging which integrates multiple damage pathways into a unified model of biological aging. This theory proposes that aging results from the synergistic interaction of four primary, reactive species-initiated processes: metal bioaccumulation, AGE formation, ALE accumulation, and the formation of persistent metal-AGE/ALE hybrid complexes (Nelson-Goedert, 2025). Unlike traditional theories that focus on individual aging mechanisms, the Conglomerate Theory emphasizes the interconnected nature of these processes and their self-reinforcing feedback loops that amplify cellular damage.

This paper presents a comprehensive extension of the Conglomerate Theory of Aging to female reproductive aging, synthesizing evidence for each component of the theory in the context of ovarian function and reproductive decline, thus providing domain-specific verification of the Conglomerate model. We examine the mechanistic pathways by which metal accumulation, AGE formation, ALE generation, and hybrid complex formation contribute to follicular depletion, oocyte quality decline, and hormonal dysfunction. Additionally, we discuss the clinical implications of this framework and review targeted, evidence-based therapeutic approaches that may be tested in clinical trials to optimize reproductive health.

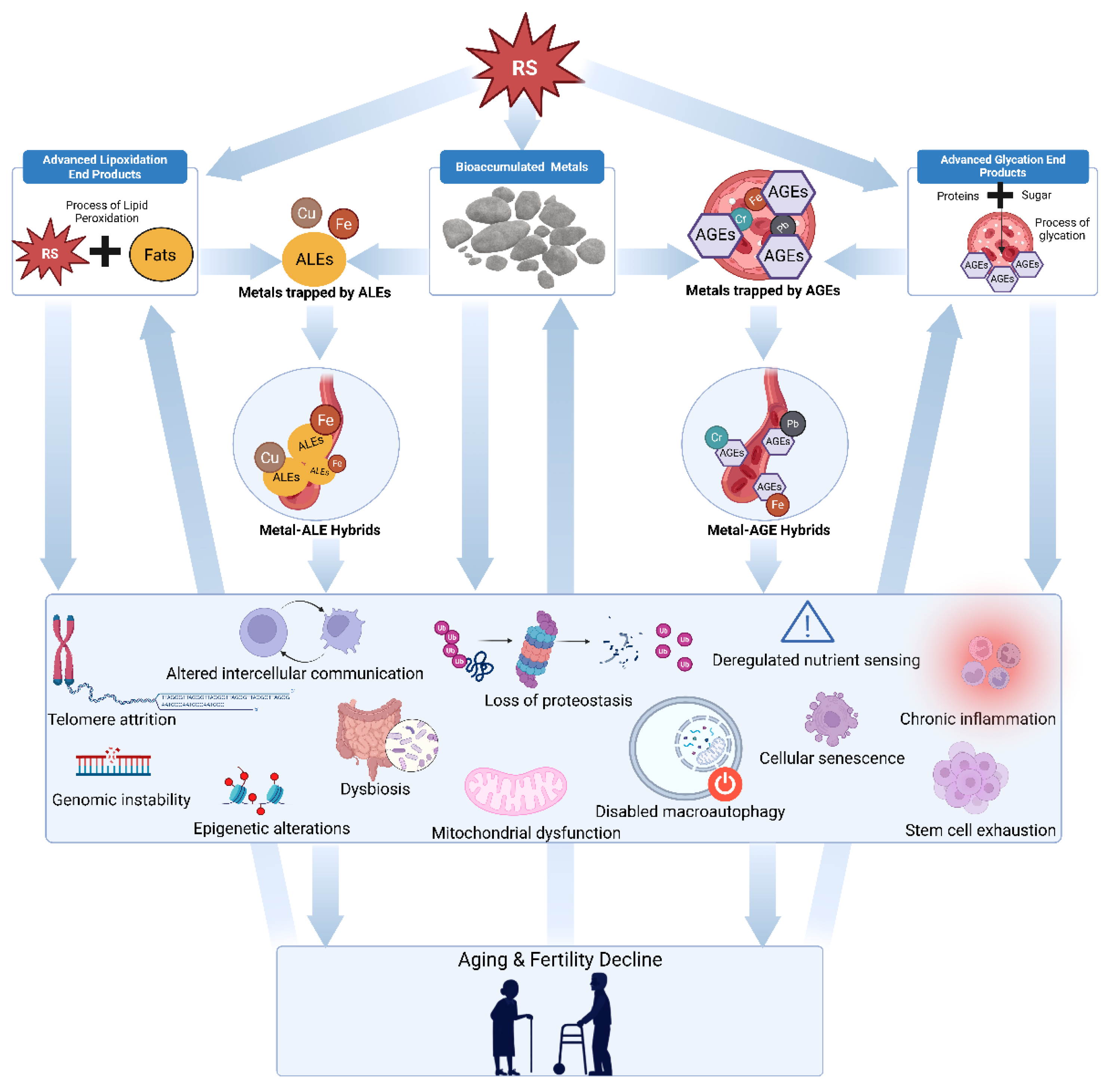

Figure 1.

Diagram illustrating the framework for the Conglomerate Theory of Female Reproductive Aging. Arrows depict proposed causal pathways, starting with damage from multiple reactive species which generate advanced glycation end products (AGEs), accumulated metals, advanced lipoxidation end products (ALEs), and metal AGE/ALE hybrid compounds. These entities collectively trigger numerous forms of cellular damage through synergistic and autocatalytic mechanisms.

Figure 1.

Diagram illustrating the framework for the Conglomerate Theory of Female Reproductive Aging. Arrows depict proposed causal pathways, starting with damage from multiple reactive species which generate advanced glycation end products (AGEs), accumulated metals, advanced lipoxidation end products (ALEs), and metal AGE/ALE hybrid compounds. These entities collectively trigger numerous forms of cellular damage through synergistic and autocatalytic mechanisms.

2. ROS, RNS, and RCS in Reproductive Aging

Oxidative and electrophilic stress emerge as the upstream mechanisms driving all components of the Conglomerate Theory of Reproductive Aging. The ovary is particularly susceptible to these insults due to its high metabolic rate, cyclical vascular remodeling, and inflammatory microenvironment (Urzúa et al., 2025; Shen et al., 2023; Shi et al., 2023). Each ovulatory event provokes transient bursts of reactive species (RS) through follicular rupture, heme release, and the recruitment of leukocytes that produce a chronically reactive environment that accelerates ovarian aging.

Researchers have traditionally emphasized reactive oxygen species (ROS), but other molecular oxidants like reactive nitrogen species (RNS) and reactive carbonyl species (RCS) play equally crucial and interconnected roles. RNS such as peroxynitrite (ONOO⁻), nitric oxide (NO), and nitrogen dioxide (NO₂) interact with ROS to form hybrid species capable of nitrating tyrosine residues, oxidizing lipids, and damaging mitochondrial DNA (Bezdíček et al., 2025; Athanasiou et al., 2025). Chronic nitrosative stress in the ovary has been implicated in impaired oocyte competence, endothelial dysfunction, and the dysregulation of steroidogenic enzymes (Bezdíček et al., 2025).

RCS such as malondialdehyde (MDA), 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), and glyoxal arise from lipid peroxidation and sugar oxidation, forming covalent adducts with nucleic acids and proteins. These reactive carbonyls contribute to the formation of advanced lipoxidation end products (ALEs) and advanced glycation end products (AGEs), which disproportionately accumulate in ovarian tissue and exacerbate mitochondrial decay, extracellular matrix stiffening, and granulosa cell senescence (Tang et al., 2025; Li et al., 2022).

Yan et al. (2022) observed that oxidative stress accelerates ovarian aging through interconnected pathways: apoptosis, inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, telomere attrition, and macromolecular damage. Each is exacerbated by the combined presence of with RNS and RCS, with concentrations rising with female age and correlate with diminished reproductive potential. Clinical observations confirm elevated oxidative and carbonyl biomarkers in follicular fluid and oocytes of women undergoing assisted reproductive technologies, with higher levels correlated with lower fertilization success (Chen et al., 2023).

Sources of these reactive species in the ovary are diverse. Physiological generation occurs during mitochondrial respiration, nitric oxide synthase activity, and steroidogenic enzyme reactions. Pathological generation is enhanced by metal-catalyzed redox cycling, chronic inflammation, and cumulative lipid peroxidation (Bezdíček et al., 2025; Xiao & Lai, 2025; Chen et al., 2024). The interplay among ROS, RNS, and RCS establishes a self-perpetuating feedback loop of oxidative, nitrosative, and carbonyl stress, driving both functional decline and structural deterioration within the ovarian microenvironment

Detoxification System Decline in Aging Ovaries

Simultaneously, the aging ovary experiences a progressive decline in its detoxification systems, rendering it increasingly vulnerable to oxidative, nitrosative, and carbonyl stress (Yang et al., 2021; Bezdíček et al., 2025; Moldogazieva et al., 2023). This deterioration occurs across multiple molecular levels, including downregulation of enzymatic antioxidants, depletion of non-enzymatic defenses, and loss of redox-regulated repair mechanisms (Ju et al., 2024; Hu et al., 2025). The imbalance among reactive oxygen (ROS), reactive nitrogen (RNS), and reactive carbonyl species (RCS) collectively produces a chronic pro-reactive environment that accelerates ovarian degeneration.

Tatone et al. (2006) demonstrated that the mRNA and protein expression of key antioxidant enzymes, superoxide dismutases (SODs) and catalase, were markedly lower in granulosa cells of older women undergoing in vitro fertilization compared with those of younger women. This reduction in antioxidant enzyme activity compromises the ovary’s capacity to detoxify superoxide radicals and hydrogen peroxide, thereby broadening oxidative vulnerability. Similar age-related declines in peroxiredoxins (PRDX3), thioredoxin 2 (TXN2), glutaredoxin 1 (GLRX1), and glutathione S-transferase mu 2 (GSTM2) have been observed in murine models, indicating global weakening of mitochondrial and cytosolic thiol-redox buffering systems.

Emerging evidence expands this vulnerability beyond oxidative stress. As mitochondrial and nitric oxide synthase regulation deteriorate with age, RNS such as nitric oxide (NO) and peroxynitrite (ONOO⁻) increase, leading to protein nitration and nitrotyrosine accumulation in granulosa and theca cells, a hallmark of nitrosative stress (Lim & Luderer, 2011; Athanasiou et al., 2025). Excess RNS disrupts mitochondrial membranes, damages steroidogenic enzymes, and contributes to decreased ATP production and telomere attrition.

The decline in detoxification capacity is pronounced in primordial follicles, which must preserve redox homeostasis over decades for reproductive function (Sasaki et al., 2019). Age-associated reductions in mitochondrial SOD1, PRDX3, and TXN2 impair defense against ROS and RNS leakage, while diminished GSH and thiol-buffer systems compromise neutralization of RCS and electrophilic aldehydes (Lim & Luderer, 2011). The resulting convergence of oxidative, nitrosative, and carbonyl stress induces apoptotic signaling and ferroptotic sensitivity, accelerating depletion of the follicular reserve (Hu et al., 2025; Sasaki et al., 2019). In toto, the simultaneous rise in ROS, RNS, and RCS establishes a self-reinforcing loop of redox and electrophilic imbalance that underpins the molecular and metabolic decline characteristic of female reproductive aging.

3. Metal Bioaccumulation in Ovarian Aging

3.1. Iron Accumulation

Iron emerges as a central antagonist in ovarian aging, with mounting evidence demonstrating accumulation in aging ovaries and detrimental effects on reproductive function. The ovary represents a unique microenvironment with relatively high iron exposure due to its cyclical activity throughout the reproductive lifespan (Chen et al., 2024). The corpus luteum, as one of the most vascularized organs in the body, undergoes extremely rapid cellular and vascular changes during luteal establishment and degeneration, creating a hemin-rich environment that predisposes follicles to iron overload conditions.

Chen et al. (2024) provided compelling mechanistic evidence that aging ovaries exhibit increased iron content along with abnormal expression of iron metabolic proteins. Their comprehensive analysis revealed dysregulation of multiple iron homeostasis factors, including heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1), ferritin heavy chain (FTH), ferritin light chain (FTL), mitochondrial ferritin (FTMT), divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1), ferroportin 1 (FPN1), iron regulatory proteins (IRP1 and IRP2), and transferrin receptor 1 (TFR1). This dysregulation creates a cascade of cellular dysfunction that directly impacts both oocyte quality and ovarian reserve.

The mechanistic consequences of iron accumulation in ovarian aging are multifaceted and interconnected. Aging oocytes counterintuitively exhibit enhanced ferritinophagy and mitophagy, processes that ironically increase cytosolic Fe2+ levels, while attempting to maintain iron homeostasis. This increase in labile iron results in elevated lipid peroxidation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and augmented lysosomal activity, creating a vicious cycle of molecular damage. Iron-mediated oxidative stress also triggers upregulation of cellular senescence markers, including p53, p21, p16, and microtubule-associated protein tau (Tau), indicating accelerated cellular aging (Chen et al., 2024).

Intervention studies have demonstrated the potential of iron chelation in mitigating ovarian aging. Deferoxamine (DFO), a potent iron chelator, improved ovarian iron metabolism and redox status in aged mice, correcting alterations in cytosolic Fe2+ levels and associated degenerative changes in oocytes. Remarkably, DFO treatment delayed the decline in ovarian reserve and significantly increased the number of superovulated oocytes while reducing fragmentation and aneuploidy rates (Chen et al., 2024). These findings suggest that iron chelation may represent a viable therapeutic strategy for preserving ovarian function for extended periods in aging women.

The clinical relevance of iron accumulation in reproductive aging extends to locations beyond the ovary. In endometriosis-related infertility, iron overload in follicular fluid has been shown to trigger granulosa cell ferroptosis and oocyte dysmaturity, with iron chelation providing amelioration in animal models (Ni et al., 2022). Moreover, transferrin insufficiency and iron overload in follicular fluid contribute to oocyte dysmaturity in women with advanced endometriosis, highlighting the broader clinical implications of iron dysregulation in reproductive disorders.

3.2. Copper and Zinc Dysregulation

Copper and zinc also undergo significant dysregulation during ovarian aging. These metals participate in numerous enzymatic processes critical for ovarian function, including antioxidant defense, hormone synthesis, and cellular signaling. However, their excess accumulation or deficiency can contribute to reproductive dysfunction.

Copper levels increase with aging, while zinc levels tend to decrease, creating an imbalanced copper-to-zinc ratio that promotes oxidative stress and cellular dysfunction (Mezzetti et al., 1998). Research has associated this imbalance with various age-related pathologies that may contribute specifically to ovarian aging through multiple mechanisms. For instance, elevated copper levels can catalyze the formation of ROS through Fenton-like reactions, while zinc deficiency impairs antioxidant enzyme function and cellular repair mechanisms (Liu et al., 2024; Xiao & Lai, 2024).

From a broader vantage point, zinc maintains a particularly complex and multifaceted role in reproductive biology. It is critical for numerous aspects of female reproduction, from oocyte maturation to fertilization and early embryonic development. During follicular development, sufficient intracellular zinc concentration in the oocyte maintains meiotic arrest at prophase I until the germ cell is ready to undergo maturation within mammals (Kong et al., 2012). Zinc deficiency or dysregulation can disrupt this process, leading to premature oocyte aging and reduced fertility potential (Liu et al., 2024).

The "zinc spark" phenomenon, a rapid release of zinc that occurs upon fertilization, represents a critical checkpoint in reproductive success (Duncan et al., 2016). This zinc release induces egg activation and facilitates zona pellucida hardening while reducing sperm motility to prevent polyspermy (Que et al., 2017). Dysregulation of zinc homeostasis can therefore have profound implications for fertilization success and early embryonic development (Garner et al., 2021).

Clinical evidence suggests that optimizing copper and zinc balance may represent a therapeutic target for preserving reproductive function (Liu et al., 2025). However, the complex interactions between these metals and their roles in reproductive biology require intentional consideration in developing therapeutic approaches, with the challenge of maintaining optimal levels while preventing pathological accumulation.

3.3. Heavy Metal Exposure

Beyond transition metals, epidemiological evidence strongly supports the role of heavy metal exposure in premature ovarian aging, with implications for both individual reproductive health and population-level fertility trends. Ding et al. (2024) conducted a comprehensive analysis of 549 middle-aged women from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN), demonstrating that women with elevated urinary levels of arsenic, cadmium, mercury, and lead were significantly more likely to have lower anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels, indicating diminished ovarian reserve. The magnitude of these associations was particularly striking, with the effects being stronger than the known relationship between smoking and ovarian reserve, suggesting that heavy metal exposure may be an overlooked yet significant contributor to reproductive aging.

The mechanistic basis for heavy metal-induced ovarian aging encompasses multiple interconnected pathways. Heavy metals can directly damage cellular structures via the generation of ROS, leading to oxidative stress and subsequent cellular dysfunction. Additionally, these metals can interfere with hormonal signaling pathways by binding to receptor sites or disrupting enzymatic processes essential for steroidogenesis. Pollack et al. (2011) demonstrated that cadmium, lead, and mercury exposure in premenopausal women was associated with diminished reproductive hormone profiles, including decreased follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and increased progesterone levels, suggesting disruption of normal hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis function.

4. Advanced Glycation End Products in Reproductive Aging

Mounting evidence indicates that advanced glycation end product (AGE) accumulation in ovarian tissue interferes with normal follicular function. AGEs form through non-enzymatic reactions between reducing sugars and amino groups in proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. In concert, these components create reactive, cross-linked compounds that universally and inexorably accumulate with age. The ovarian microenvironment is notably susceptible to AGE accumulation due to its high metabolic activity and cyclical nature. Pertynska-Marczewska and Diamanti-Kandarakis (2017) provided comprehensive evidence that AGEs accumulate within ovarian follicles and may trigger ovarian aging by reducing glucose uptake by granulosa cells, potentially altering follicular growth patterns. This accumulation appears to be an active contributor to the acceleration of ovarian aging in particular, alongside systemic aging.

Of note, the spatial distribution of AGEs within ovarian tissue reveals their preferential accumulation in areas critical for reproductive function. Histological studies have demonstrated AGE deposition in granulosa cells, theca cells, and the extracellular matrix surrounding follicles, suggesting that these compounds may interfere with multiple aspects of follicular development and function (Pennarossa et al., 2022; Garg & Merhi, 2016; Diamanti-Kandarakis et al., 2007). The accumulation is particularly pronounced in atretic follicles, indicating that AGEs may substantively contribute to follicular death and the progressive depletion of ovarian reserve (Liew et al., 2017).

4.1. The AGE-RAGE Axis in Ovarian Pathophysiology

The biological effects of AGEs are substantively mediated through their interaction with the receptor for AGEs (RAGE), a pattern recognition receptor that binds ligands and initiates inflammatory signaling cascades. The AGE-RAGE axis plays an important role in ovarian pathophysiology, contributing to the chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and cellular dysfunction that characterize ovarian aging.

Diamanti-Kandarakis et al. (2007) demonstrated that RAGE and AGE-modified proteins with activated nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) are expressed in human ovarian tissue, suggesting active inflammatory responses to AGE accumulation. This inflammatory cascade involves the activation of multiple downstream signaling pathways, including the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules that contribute to tissue damage and dysfunction.

The chronic activation of the AGE-RAGE axis in ovarian tissue creates a state of persistent low-grade inflammation, a regional expression of inflammaging, which that accelerates follicular dysfunction (Merhi, 2014; Li et al., 2021). This inflammatory environment can impair granulosa cell function, disrupt hormonal signaling, and create conditions conducive to follicular atresia (Huang et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2025). The self-perpetuating nature of this inflammatory response, where AGE-induced inflammation promotes further AGE formation, creates a vicious cycle that accelerates ovarian aging (Rungratanawanich et al., 2021).

4.2. AGE-Mediated Disruption of Ovarian Function

The mechanistic damage of AGEs on ovarian function extends to encompass fundamental disruption of cellular processes essential for reproductive success, including hormone synthesis, glucose metabolism, and cellular signaling pathways that regulate follicular development and ovulation.

Kandakari et al. (2018) demonstrated that AGEs reduce luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)-induced ERK1/2 activation in human granulosa cells, which is critical for granulosa cell mitogenesis and proliferation. This interference with gonadotropin signaling pathways represents a fundamental disruption of the hormonal regulation essential for ovarian function. The impairment of granulosa cell proliferation and function has cascading effects on follicular development, steroid hormone production, and oocyte maturation.

The metabolic effects of AGEs on ovarian function are equally noteworthy. AGEs have been shown to impair insulin signaling in granulosa cells, preventing glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) membrane translocation and disrupting glucose metabolism (Diamanti-Kandarakis et al., 2016). This metabolic dysfunction can contribute to the pathophysiology of conditions characterized by anovulation and insulin resistance, such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), while also impairing the energy supply necessary for normal oocyte development and maturation.

4.3. Dietary AGEs and Reproductive Health

The consumption of dietary AGEs has recently gained attention as a modifiable risk factor for ovarian dysfunction. Dietary AGEs are formed during food processing under high-temperature conditions such as frying, baking, and grilling. These exogenous AGEs can be absorbed and contribute to the body’s total AGE burden, potentially accelerating ovarian aging and impairing reproductive function (Merhi et al., 2025; Tong et al., 2025). Thornton et al. (2020) demonstrated that consumption of high-AGE diets can disrupt folliculogenesis and steroidogenesis, leading to abnormal estrous cyclicity and altered reproductive hormone profiles in animal models These findings suggest that dietary modulation to reduce AGE intake may preserve reproductive function and delay ovarian aging.

5. Advanced Lipoxidation End Products in Ovarian Aging

Advanced lipoxidation end products (ALEs) represent an additional critical yet overlooked component of ovarian aging. They are formed through the reactions of lipid peroxidation products with amino groups in proteins and other biomolecules. The oocyte is particularly vulnerable to lipid peroxidation and subsequent ALE formation due to its extensive membrane systems and high lipid configuration (Pamplona, 2008; Smits et al., 2023). This vulnerability is compounded by the extended lifespan of oocytes, which may remain arrested in meiosis I for decades before ovulation (Mikwar et al., 2020).

Lord et al. (2015) provided compelling evidence that electrophilic aldehydes, including 4-hydroxynonenal (4HNE), malondialdehyde, and acrolein, accumulate in aging oocytes and form covalent adducts with multiple cellular proteins. These ALEs are byproducts of nonenzymatic lipid peroxidation that increase with extended periods of time post-ovulation aging processes. The accumulation of these highly reactive compounds strongly correlates with postovulatory oocyte aging and reduced fertility potential (Lord, 2025).

The mechanistic impact of ALEs on oocyte function is multifaceted. Mihalas et al. (2017) demonstrated that aged oocytes are particularly vulnerable to damage by 4HNE resulting from increased cytosolic ROS production within the oocyte itself. Exposure to 4HNE resulted in decreased meiotic completion, increased spindle abnormalities, chromosome misalignments, and aneuploidy. Such findings directly link ALE accumulation to the increased rates of chromosomal abnormalities observed in oocytes from older women, providing an additional, independent explanation for the age-related decline in oocyte quality.

5.1. ALE Targeted Proteins

The proteins targeted by ALEs in oocytes include many that are essential for normal meiotic progression and oocyte health. Mihalas et al. (2017) identified that proteins essential for oocyte health and meiotic development, including α-, β-, and γ-tubulin, are particularly vulnerable to adduction via 4HNE. These cytoskeletal proteins are crucial for proper spindle formation and chromosome segregation during meiosis, and their modification by ALEs can lead to meiotic errors and aneuploidy.

The mitochondrial protein succinate dehydrogenase (SDHA) has been identified as a primary target for 4HNE adduction in aging oocytes (Lord et al., 2015). This modification has particularly insidious ramifications because SDHA is a key component of the electron transport chain, and its dysfunction can lead to mitochondrial dysfunction, increased ROS production, and ultimately apoptosis. The preferential targeting of mitochondrial proteins by ALEs creates a vicious cycle where lipid peroxidation leads to mitochondrial dysfunction, which in turn generates more ROS and promotes further lipid peroxidation and ALE propagation.

The consequences of protein modification by ALEs additionally encompass the disruption of protein degradation pathways, as ALEs can interfere with normal protein turnover by creating cross-links that resist degradation by cellular proteases. This resistance to degradation leads to the accumulation of damaged proteins and contributes to the overall decline in cellular function observed in aging oocytes.

5.2. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and ALE Formation

Mitochondria are substantive sources of ROS, while they are simultaneously primary targets of oxidative damage. This renders them particularly vulnerable to lipid peroxidation and ALE formation in aging oocytes with reduced mitochondrial DNA content, altered mitochondrial morphology, and impaired oxidative phosphorylation capacity (Kushnir et al., 2012; Smits et al., 2023). These mitochondrial changes are associated with increased ROS production and enhanced lipid peroxidation, creating conditions conducive to ALE formation. The accumulated ALEs then further impair mitochondrial function by modifying key mitochondrial proteins, creating a pernicious damage cycle (Lord et al., 2015).

The clinical implications of mitochondrial dysfunction in reproductive aging are significant. The process is associated with decreased oocyte quality, increased aneuploidy rates, and reduced fertility potential in women of advanced maternal age (Smits et al., 2023). Understanding the causal role of ALEs in mitochondrial dysfunction provides new insights into the mechanisms underlying these clinical observations and suggests potential therapeutic targets for preserving youthful function.

5.3. Membrane Lipid Deterioration in Aging Oocytes

Recent granular lipidomic analyses in humans have confirmed the relevance of lipid peroxidation to ovarian aging. Smits et al. (2023) used comprehensive lipidomics to demonstrate that all phospholipid classes decreased in abundance with increasing female age in both germinal vesicle and metaphase II oocytes. This phospholipid depletion was accompanied by evidence of increased oxidative stress, including shifts in the glutathione-to-oxidized glutathione ratio and accumulation of ALEs.

The loss of membrane phospholipids in aging oocytes has significant functional implications. Phospholipids are essential components of cellular membranes and play crucial roles in membrane integrity, fluidity, and function. The depletion of phospholipids can impair membrane-dependent processes, including organelle function, signal transduction, and cellular metabolism.

6. Hormonal Dysfunction and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Ovarian Axis Changes

Effects of the biophysical accumulations delineated by the Conglomerate Theory of Aging culminate in hormonal instability via progressive disruption of the HPO axis. Transition metals such as iron and copper, along with heavy metals including cadmium, mercury, lead, and arsenic, bioaccumulate in both neuronal and ovarian tissues over the lifespan. Their redox-active nature catalyzes the continuous generation of reactive oxygen, nitrogen, and carbonyl species through Fenton and Haber–Weiss chemistry. Studies in aging mice demonstrate that iron accumulation in the ovary perturbs local iron metabolism, enhances ferritinophagy, and drives ferrous iron excess, leading to lipid peroxidation and mitochondrial degeneration in oocytes (Chen et al., 2024; Ding et al., 2024). Similarly, longitudinal analyses of midlife women reveal that urinary cadmium and mercury levels correlate with accelerated decline in anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), indicating premature follicular depletion and diminished ovarian reserve (Ding et al., 2024).

Bioaccumulated metals serve as both initiators of the oxidative and carbonyl stress that promote AGE and ALE formation, as well as independent model inputs alongside these two end products. Such reactive biomolecular adducts accumulate in granulosa cells, pituitary tissue, and hypothalamic neurons, altering protein folding, receptor configuration, and intracellular signaling (Miler et al., 2010; Pamphlett et al., 2019; Merhi et al., 2025). Binding of AGEs and ALEs to the RAGE receptor activates chronic NF-κB signaling and sustains low-grade inflammation that disrupts gonadotropin feedback sensitivity (Tóbon-Velasco et al., 2014). This oxidative-inflammatory feedback loop initiates a progressive loss of endocrine control before overt menopause (Kobayashi et al, 2009).

Within the ovary, AGEs and ALEs impair steroidogenesis by damaging mitochondrial steroidogenic enzymes and crosslinking membrane receptors involved in FSH and LH signaling (Colella et al., 2021). Concurrently, transition metals reduce the efficiency of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase, further amplifying oxidative load (van der Reest et al., 2021). The result is a biochemical environment dominated by redox imbalance, hormonal desensitization, and follicular apoptosis.

In terms of the central nervous system, metal accumulation within the hypothalamus distorts GnRH neuron function by impairing calcium signaling and increasing microglial oxidative activation (Wang et al., 2023; Gyengesi et al., 2012; Krsmanović et al., 1992). This drives irregular GnRH pulsatility and erratic pituitary gonadotropin release. With feedback inhibition from inhibin and estradiol weakening under the joint influence of ALE-induced receptor dysfunction and granulosa attrition, FSH hypersecretion ensues, initially compensatory, but ultimately self-defeating, accelerating follicular exhaustion (Broekmans et al., 2009; Terasaka et al., 2017; Hall, 2007).

As these upstream toxicants compound, the endocrine network enters a state of Conglomerate collapse, in which hormonal feedback regulation deteriorates despite rising gonadotropin drive. The result is the classical perimenopausal presentation of hypergonadotropism, anovulation, and erratic estradiol secretion as the visible end stage of decades of molecular damage initiated by metals, AGEs, and ALEs (Wang et al., 2021). The convergence of these toxic and metabolic stressors thus represents a foundational biochemical mechanism underlying the breakdown of the HPO axis and the onset of reproductive senescence.

6.1. Steroid Hormone Production and Metabolism

The production and metabolism of steroid hormones undergo simultaneous alterations during ovarian aging. Shifts in estradiol, progesterone, testosterone, androstenedione, and dehydroepiandrosterone metabolism also contribute to the complex hormonal profile of reproductive senescence.

Increasing evidence implicates the gradual accumulation of bioinorganic and carbonyl-derived toxins, which comprise the Conglomerate Theory, as primary molecular initiators of steroidogenic decline (Xiao & Lai, 2025; Ju et al., 2024). These agents accumulate within the ovarian stroma, granulosa, and theca cells, where they disrupt mitochondrial and enzymatic functions essential for steroid hormone biosynthesis (Yan et al., 2025; Smits et al., 2023).

At the enzymatic level, metals such as iron and copper catalyze uncontrolled redox cycling, producing reactive oxygen and nitrogen species that oxidatively modify key steroidogenic enzymes, including cytochrome P450 aromatase (CYP19A1), 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD3B2), and steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) (Lou et al., 2025; Yiqin et al., 2022; Korytowski et al., 2013; Gantt et al., 2009). These modifications impair cholesterol transfer, pregnenolone conversion, and estradiol biosynthesis. Concurrently, cadmium and mercury mimic zinc and selenium cofactors, displacing them in metalloenzymes critical for steroid hydroxylation and sulfation reactions, leading to endocrine disruption and lowered steroid output.

In parallel, AGEs and ALEs accumulate within ovarian cells as irreversible carbonyl adducts on steroidogenic and chaperone proteins, further reducing enzymatic turnover and receptor sensitivity (Derakhshan et al., 2024; Mouanness & Merhi, 2022; Garg & Merhi, 2016; Liu et al., 2023). Binding of AGEs and ALEs to RAGE triggers chronic inflammatory and oxidative signaling cascades, increasing NF-κB activation and amplifying redox damage to the steroidogenic organelles (Dong et al., 2022; Lu et al., 2004). These processes coalesce into a toxic biochemical network that compromises estradiol synthesis while also perturbing the androgen-to-estrogen balance and progesterone metabolism. This yields the uneven hormonal milieu characteristic of the perimenopausal transition.

The downstream consequences extend to global hormone handling and clearance. Oxidative and carbonyl stress alter hepatic conjugation pathways and sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) regulation, reducing steroid bioavailability. Epidemiologic evidence from midlife cohorts shows that metal exposure correlates with perturbed FSH, estradiol, and SHBG levels, reinforcing that toxicant bioaccumulation and carbonyl adduct formation mechanistically align with the endocrine signatures of ovarian aging (Wang et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023; Mei et al., 2025; Bourebaba et al., 2023; Kornicka-Garbowska et al., 2021). Thus, the age-related diminishment in steroid hormone production and metabolism originates from a multi-toxicant nexus of bioaccumulated metals, AGEs, and ALEs that disable the redox and enzymatic infrastructure of steroidogenesis.

6.2. Hypothalamic-Pituitary Network Degeneration and Feedback Failure

The hypothalamus and pituitary act as the coordination centers of neuroendocrine communication, modulating gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) pulsatility and luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) secretion. With aging, the central feedback mechanisms that normally synchronize ovarian signals with systemic hormonal rhythms become increasingly unstable.

Recent findings reveal that this instability is driven in part by bioaccumulated transition and heavy metals, advanced glycation end products (AGEs), and advanced lipoxidation end products (ALEs) within neural tissues. These reactive entities accumulate in the hypothalamic microvasculature, glial cells, and pituitary parenchyma, where they catalyze chronic oxidative and carbonyl stress. Transition metals such as iron and copper promote Fenton-type reactions in the hypothalamus, leading to peroxidation of neuronal membranes and loss of estrogen receptor β expression in critical GnRH-regulating regions (Jomova et al., 2012; Walker & Gore, 2017; Lizcano, 2022). Concurrently, AGEs and ALEs cross the blood-brain barrier, bind to RAGE on astrocytes and microglia, and trigger NF-κB–driven neuroinflammatory cascades that desynchronize GnRH pulse generation (Lu et al., 2004; Dong et al., 2022).

This toxicant-induced redox imbalance diminishes hypothalamic sensitivity to estrogen feedback, a process historically identified as “central unresponsiveness” in perimenopausal women. As the negative feedback loop between estradiol and pituitary gonadotropin secretion weakens, basal levels of LH and FSH rise, precipitating a hypergonadotropic but functionally hypoestrogenic state (Brinton et al., 2015; Weiss et al., 2004). Over time, this central dysregulation amplifies ovarian metabolic stress by overstimulating partially senescent follicles.

Chronic exposure to circulating metals, AGEs, and ALEs also compromises pituitary integrity. Cadmium and lead interfere with metalloproteins controlling hormone vesicle release, while oxidative modifications of gonadotroph receptors impair GnRH responsiveness, compounding dysrhythmic secretion (Santiago-Andres et al., 2025; Lafuente, 2013). These cumulative insults transform the feedback architecture of the HPO axis into a self-sustaining loop of oxidative excitation and endocrine inefficiency, where both hypothalamic neurons and ovarian follicles are reciprocally degraded by the same Conglomerate toxic milieu (Rijal et al., 2022; Terasaka et al., 2017). The eventual outcome is a coordinated central-peripheral decline characterized by erratic GnRH firing, elevated pituitary output, impaired ovarian steroidogenesis, and systemic consequences ranging from vasomotor instability to mood and cognitive symptoms (Rance, 2009; Klein & Soules, 1998).

7. Clinical Trial Compounds to Delay Female Reproductive Aging

The complexity of ovarian aging suggests that comprehensive interventions targeting multiple pathways simultaneously may be more effective than single-target approaches. This concept aligns with the Conglomerate Theory's emphasis on the interconnected nature of aging processes and the importance of addressing multiple damage pathways simultaneously to achieve meaningful therapeutic benefits.

Combinatorial therapies that target different aspects of molecular damage may provide synergistic benefits for preserving ovarian function. The combination of different compounds with complementary mechanisms of action, such as lipophilic and hydrophilic substances, may provide more comprehensive protection than individual compounds alone. Additionally, the combination of these compounds with other interventions may provide additive or synergistic benefits.

7.1. Reactive Species Therapy

Glutathione is the body’s primary intracellular antioxidant and detoxifier, essential for maintaining mitochondrial integrity, detoxifying transition and heavy metals, and preventing the oxidative and carbonyl stress that undermine ovarian function (Calabrese et al., 2017). Its decline with age or metabolic stress contributes to reduced oocyte viability, impaired steroidogenesis, and altered endometrial receptivity (Hu et al, 2025). N-acetylcysteine (NAC) replenishes glutathione by supplying cysteine, the rate-limiting substrate for its synthesis, restoring redox capacity within granulosa and theca cells and mitigating AGE/ALE-mediated and metal-catalyzed toxicity (Ji et al., 2022). Clinical studies using up to 1800 mg daily show that NAC improves oocyte quality, follicular development, and IVF outcomes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome and age-related fertility decline by enhancing glutathione levels in follicular fluid and stabilizing mitochondrial DNA integrity (Cheraghi et al., 2016). Glycine, another precursor in glutathione synthesis, complements NAC’s activity as part of the GlyNAC combination (typically 1-1.5g glycine + 600 mg NAC twice daily), which restores glutathione more effectively than either alone, improving mitochondrial function, reducing oxidative and carbonyl stress, and normalizing reproductive hormone signaling in aging models (Kumar et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2023). Together, glycine and NAC fortify the ovarian microenvironment, safeguard oocyte competence, and support endocrine balance, offering a redox-centric therapeutic approach to preserving female fertility.

Selenium is equally indispensable for sustaining glutathione activity, serving as a structural component of the glutathione peroxidase family that detoxifies lipid peroxides and preserves cellular redox balance (Brigelius-Flohé & Flohé, 2020). Selenium plays a targeted role in delaying female reproductive aging by sustaining the antioxidant enzyme network essential for ovarian health (Yang et al., 2019; Lava Kumar et al., 2024). Through its incorporation into glutathione peroxidase and selenoproteins such as GPX1 and GPX4, selenium preserves mitochondrial membrane potential, prevents apoptotic signaling within granulosa and oocyte cells, and supports normal folliculogenesis (Cheng et al., 2023; Hummitzsch et al., 2024). Animal studies show that maintaining optimal selenium levels prevents loss of primordial follicles and improves embryo development rates, while human data link higher follicular fluid selenium concentrations to better oocyte maturation and fertilization outcomes (Yang et al., 2019; Mahsa Poormoosavi et al., 2021; Lava Kumar et al., 2024). The NIH recommends consumption of 55 mcg of selenium per day for adult women (Office of Dietary Supplements, 2025).

Lycopene, typically administered at 10–20 mg daily, is a powerful carotenoid antioxidant that quenches singlet oxygen, activates the Nrf2/HO-1 cytoprotective pathway, and reduces lipid peroxidation and mitochondrial oxidative load (Yang et al., 2017). Both animal and human studies demonstrate that lycopene supplementation improves oocyte morphology, preserves follicular integrity, and reduces follicular atresia by mitigating ROS-mediated and metal-catalyzed damage within ovarian tissue (Liu et al., 2018). In murine models, lycopene has been shown to lower malondialdehyde levels and restore superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase activity, thereby preserving spindle organization and meiotic competence of oocytes (Rakha et al, 2022). Human trials associate higher circulating lycopene with improved anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels and reduced oxidative biomarkers in women undergoing assisted reproduction (Maldonado-Cárceles, 2025).

Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10), at 200–300 mg daily for at least three months, supports mitochondrial bioenergetics and serves as a potent lipid-phase antioxidant within oocytes and granulosa cells (Ben-Meir et al., 2015). As a cofactor in the electron transport chain, CoQ10 enhances ATP production—critical for chromosomal segregation and early embryonic development—and protects mitochondrial DNA from oxidative and carbonyl stress (Niu et al., 2020). Clinical and animal studies show that CoQ10 supplementation increases antral follicle counts, improves ovarian reserve indices, and yields higher numbers of mature oocytes and quality embryos in women of advanced reproductive age or diminished ovarian reserve (Xu et al., 2018). Meta-analyses confirm that pre-treatment with CoQ10 prior to IVF enhances fertilization and clinical pregnancy rates, effects closely linked to restoration of mitochondrial efficiency, reduction of ROS, and decreased formation of AGEs and ALEs within the ovarian microenvironment (Jiang et al., 2025; Lin et al.,2024).

7.2. Metal Chelation Therapy

Alpha-lipoic acid (ALA), typically taken at 400–600 mg daily, is a dual-function antioxidant and metal chelator that regenerates other antioxidants such as vitamins C and E and glutathione (Anjos et al., 2025). It improves mitochondrial energy metabolism and counters redox imbalance within oocytes and granulosa cells, thereby preserving cytoplasmic integrity, spindle structure, and overall oocyte quality (Zhang et al., 2022). Human and animal studies show that ALA supplementation enhances meiotic competence, fertilization rates, and endometrial receptivity, especially under oxidative or metabolic strain as seen in PCOS or age-related decline (Anjos et al., 2025, Di Nicuolo et al., 2019; Guarano et al., 2023). By binding redox-active metals (iron, copper), ALA reduces the catalytic generation of reactive oxygen and carbonyl species, preventing the formation of AGEs and ALEs within ovarian tissue and improving implantation potential (Mokhtari et al., 2024).

Beyond its peripheral antioxidant role, ALA’s amphipathic solubility allows it to cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB), accessing neuroendocrine centers such as the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, which are known to bioaccumulate transition metals and lipid peroxidation products over time (Anjos et al., 2025). Within these tissues, ALA has been shown to chelate iron and copper, suppress neuroinflammation, lower IL-1β and TNF-α, and restore mitochondrial coupling efficiency. All of such effects that may protect gonadotropin and steroidogenic signaling from metal-driven oxidative injury (Mokhtari et al., 2024). This dual systemic and central action positions ALA as a unique reproductive protectant, simultaneously improving local ovarian redox status and mitigating hypothalamic–pituitary dysfunction to support hormonal equilibrium and fertility (Zhang et al., 2022; Anjos et al., 2025).

7.3. Advanced Glycation End Product Prevention Therapy

Benfotiamine is a lipid-soluble derivative of thiamine that enhances transketolase activity, diverting excess glycolytic intermediates away from the polyol, hexosamine, and AGE-forming pathways associated with oxidative and carbonyl stress (Bozic & Lavrnja, 2023). Clinical and biochemical studies show that benfotiamine (150–300 mg daily) suppresses AGE accumulation, lowers malondialdehyde (MDA) and other oxidative stress markers, and restores endothelial and mitochondrial function in high-glycation environments (Alkhalaf et al., 2012; Schmid et al., 2008; Gholami et al., 2025; Xu et al., 2018; Bönhof et al., 2022). While direct reproductive data are still limited, benfotiamine’s protection of vascular and metabolic integrity implies potential benefits for ovarian perfusion and protection from AGE/ALE-related inflammation implicated in PCOS and metabolic infertility (Szczuko et al., 2021).

L-carnosine, generally taken at 500–1000 mg twice daily, is a naturally occurring β-alanine–L-histidine dipeptide with potent antiglycation and metal-chelating properties that extend meaningfully into reproductive contexts (Prokopieva et al, 2016). In animal reproductive models, carnosine supplementation improved ovarian antioxidant enzyme activity (notably SOD and glutathione peroxidase), lowered malondialdehyde and reactive carbonyl species, and preserved healthy follicular structures under oxidative or metabolic stress (Arslan et al., 2022). Studies in cultured granulosa cells exposed to glycoxidative or metal-induced injury show that carnosine restores mitochondrial potential, limits apoptosis, and maintains FSH receptor expression—effects that collectively stabilize the follicular microenvironment and support steroidogenic function (Prokopieva et al, 2016). These findings suggest that carnosine’s antiglycation and redox-modulating activity may help preserve ovarian reserve, oocyte competence, and endometrial health, complementing other interventions that target AGE/ALE accumulation and metal-driven oxidative stress (Boldyrev et al., 2013).

7.4. Advanced Lipoxidation End Product Prevention Therapy

The gamma-tocopherol form of vitamin E, administered at 200-400 IU daily, targets lipid peroxidation products that compromise membrane integrity. As a lipid-soluble compound, gamma-tocopherol scavenges reactive nitrogen and carbonyl intermediates more effectively than alpha-tocopherol, lowering oxidative stress markers in serum and follicular fluid (Es-sai et al., 2025; Luddi et al., 2016). Supplementation has been associated with improved ovarian blood flow, progesterone production, oocyte maturation, and luteal function (Md Amin et al., 2022; Cicek et al., 2012). Together, ALA and gamma-tocopherol support mitochondrial efficiency, reduce ALE formation, and protect against membrane and DNA oxidation, key mechanisms underpinning enhanced oocyte quality, endometrial health, and overall female fertility.

Magnesium has been shown in both human and animal studies to improve female fertility by reducing nitrosative, oxidative, and carbonyl stress, thus limiting ALE and AGE formation, and mitigating toxic metal accumulation that interferes with ovarian and hormonal function (Fujita et al., 2023; Agarwal et al., 2012; Kapper et al., 2024; Cosme et al., 2022; Noviyana et al., 2025). In premenopausal women, magnesium supplementation (500 mg/day for 4 weeks) significantly increased anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels, improving follicle recruitment and fertility potential (Sundas et al., 2024). This reflects magnesium’s ability to stabilize redox balance, inhibit Fenton-type metal catalysis (iron, copper), and suppress glycoxidative byproduct generation, processes that otherwise degrade oocyte quality.

Magnesium also functions as a physiological antagonist to heavy metals and transition metals, preventing their intestinal absorption and interfering with their replacement of essential cofactors in steroidogenic enzymes, thereby indirectly protecting against the formation of AGEs and ALEs (Sissi & Palumbo, 2009; NIDDK, 2024; Tran et al., 2025). Clinical guidance from the NIH and other expert sources generally recommends 310–320 mg/day for adult women, though supplementation up to 500 mg/day has been used safely to optimize reproductive hormone balance and ovarian reserve markers (Kapper et al., 2024).

7.5. Hormone Therapy

Vitamin D₃ supports female fertility by improving ovulatory function, enhancing ovarian redox balance, and counteracting reproductive damage from transition and heavy metals, as well as advanced glycation and lipoxidation end products (AGEs and ALEs) (Li et al., 2024; Avelino & de Araújo, 2024). It acts through vitamin D receptors expressed in granulosa and theca cells, where adequate serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels (≥ 30 ng/mL or 75 nmol/L) optimize folliculogenesis and reduce oxidative and carbonyl stress that impair oocyte quality (Yao et al., 2017). Meta-analyses of randomized trials report markedly higher clinical pregnancy rates in women receiving vitamin D supplementation (1000–10,000 IU daily for 30–60 days, or 50 000 IU weekly for 8 weeks) compared with deficient controls, correlating with improved antioxidant activity and suppression of inflammatory, metal-catalyzed pathways (Yang et al., 2023; Meng et al., 2023). Most endocrinology guidelines recommend maintaining daily intakes of 1 500–2 000 IU of vitamin D₃ to achieve optimal reproductive and metabolic outcomes in women of fertility age (Demay et al., 2024).

7.6. Trace Element Therapy

Zinc maintains redox homeostasis, protects against transition-metal-catalyzed oxidative damage, and suppresses the formation of AGEs and ALEs that degrade oocyte and granulosa cell function in female reproductive aging (Mocchegiani, 2007; Shao et al., 2024). Sufficient zinc availability prevents the displacement of essential cofactors by toxic metals such as cadmium or lead and stabilizes antioxidant and DNA-repair enzymes (Zhai et al., 2014; Eddie-Amadi et al., 2022). This reduces ROS-driven injury and maintains mitochondrial integrity within ovarian tissue (Liu et al., 2024). Experimental models show that zinc deficiency provokes mitochondrial dysfunction, follicular apoptosis, and meiotic arrest, while supplementation with zinc salts (zinc glycinate or ZnSO₄ at 15-50 mg per day in humans or 4-10 mg Zn/kg feed in mammals) restores AMH levels, promotes germinal vesicle breakdown, and improves oocyte quality (Yao et al., 2023; Lai et al., 2023). Clinical and nutritional reviews recommend maintaining elemental zinc intake near 8 mg/day for women and 11 mg/day for those with imminent fertility goals or heavy-metal exposure, as higher physiological zinc status correlates with lower oxidative stress markers and improved ovulatory efficiency (Mashahadi et al., 2025).

These recommended doses reflect levels shown to be effective in published studies and are intended to guide both clinical practice and future research, ensuring that interventions are appropriately powered to test the Conglomerate Theory’s predictions in female reproductive aging.

8. Clinical Translation and Future Directions

Biomarker Development and Clinical Assessment

The translation of the Conglomerate Theory to clinical practice requires the development of robust biomarkers that can assess each component of the theory and guide therapeutic interventions. Current biomarkers of ovarian aging, such as AMH and antral follicle count, provide valuable information about ovarian reserve but do not assess the underlying mechanisms of aging or predict intervention responses.

The development of specific biomarkers for metal accumulation and AGE/ALE formation would provide more comprehensive assessment of reproductive aging and guide targeted therapeutic interventions. These biomarkers might include measures of stress markers in serum fluid, assessment of metal levels in biological samples, and evaluation of AGE/ALE accumulation in accessible tissues. Consequently, integrating multiple biomarkers into comprehensive assessment panels may provide more accurate prediction of reproductive outcomes. Machine learning approaches that integrate them to assess in both linear and non-linear modalities may provide powerful tools for personalized treatment of reproductive aging.

Future Research Directions

While the Conglomerate Theory provides a compelling framework for understanding reproductive aging, several aspects of the theory require further validation and mechanistic understanding. More specifically, the formation and characterization of metal-AGE/ALE hybrids require additional elucidation, as most mechanistic studies have been conducted in animal models or in vitro. Advanced analytical techniques such as mass spectrometry may be needed to characterize these complex molecular interactions.

The temporal dynamics of damage accumulation and the relative importance of different aging mechanisms at different stages of reproductive aging also require further investigation. Understanding when and how these different processes contribute to ovarian aging may help optimize the timing of therapeutic interventions.

9. Conclusion

The Conglomerate Theory of Aging offers a unified framework for understanding female reproductive aging as a multifactorial process driven by the interplay of metal bioaccumulation, advanced glycation and lipoxidation end-product (AGE/ALE) formation, and hybrid metal complex generation. These processes, each supported by empirical evidence, converge to accelerate ovarian reserve depletion, deteriorate oocyte quality, and disrupt hormonal and cellular homeostasis. By integrating oxidative, glycoxidative, and inflammatory mechanisms, the theory captures the inherently interconnected nature of reproductive aging, emphasizing how feedback between metabolic dysregulation and metal-catalyzed oxidative stress propagates cumulative cellular injury throughout the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian network.

Therapeutically, the theory provides a rationale for multi-targeted interventions aimed at delaying ovarian aging and extending reproductive vitality. Evidence supporting antioxidant supplementation, particularly with N-acetylcysteine (NAC) and GlyNAC, points toward restoration of redox balance and mitigation of AGE/ALE-driven damage. Parallel strategies such as metal chelation and inhibition of carbonyl stress hold additional promise for reducing biomolecular cross-linking and toxic metal retention. Translation of the theory to clinical practice requires precise biomarker development, longitudinal validation of mechanistic pathways, and controlled trials integrating systems biology with personalized interventions. Collectively, the Conglomerate Theory establishes a coherent mechanistic basis for female reproductive aging while guiding the design of next-generation therapies to preserve ovarian function and extend healthy reproductive lifespan. With clinical validation, this endeavor will empower women by limiting potential conflict between early career success and typical fertility windows, while simultaneously enabling couples to reach desired family sizes with longer periods to plan and delegate resources.

Author Contributions

The author is solely responsible for all aspects of this work, including theory development, manuscript preparation, and analysis.

Funding

No funding was received to support this work.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Dr. Chidi Nwekwo, Near East University, for his expert contributions as a biomedical illustrator in creating the schematic diagram used to demonstrate our theory of aging. Dr. Nwekwo's skillful visual interpretation of the major concepts presented in this work greatly enhanced the clarity and accessibility of our theoretical framework.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest related to this work.

References

- Agarwal, A., Aponte-Mellado, A., Premkumar, B. J., Shaman, A., & Gupta, S. (2012). The effects of oxidative stress on female reproduction: a review. Reproductive biology and endocrinology : RB&E, 10, 49. [CrossRef]

- Alkhalaf, A., Kleefstra, N., Groenier, K. H., Bilo, H. J., Gans, R. O., Heeringa, P., Scheijen, J. L., Schalkwijk, C. G., Navis, G. J., & Bakker, S. J. (2012). Effect of benfotiamine on advanced glycation endproducts and markers of endothelial dysfunction and inflammation in diabetic nephropathy. PloS one, 7(7), e40427. [CrossRef]

- Anjos, M. M. D., de Paula, G. R., Yokomizo, D. N., Costa, C. B., Bertozzi, M. M., Verri, W. A., Jr, Alfieri, A. A., Morotti, F., & Seneda, M. M. (2025). Effect of Alpha-Lipoic Acid on the Development, Oxidative Stress, and Cryotolerance of Bovine Embryos Produced In Vitro. Veterinary sciences, 12(2), 120. [CrossRef]

- Arslan, A., Balcioğlu, E., Nisari, M., Yalçin, B., Ülger, M., Güler, E., Uzun, G. B., & Acer, N. (2022). Effect of carnosine on ovarian follicle in rats exposed to electromagnetic field. European Journal of Anatomy, 26(6), 659–668. [CrossRef]

- Athanasiou, D., Voros, C., Soyhan, N., Panagou, G., Sakellariou, M., Mavrogianni, D., Bikouvaraki, E. S., Daskalakis, G., & Pappa, K. (2025). The Molecular Landscape of Nitric Oxide in Ovarian Function and IVF Success: Bridging Redox Biology and Reproductive Outcomes. Biomedicines, 13(7), 1748. [CrossRef]

- Avelino, C. M. S. F., & de Araújo, R. F. F. (2024). Effects of vitamin D supplementation on oxidative stress biomarkers of Iranian women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a meta-analysis study. Revista brasileira de ginecologia e obstetricia : revista da Federacao Brasileira das Sociedades de Ginecologia e Obstetricia, 46, e-rbgo37. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Meir, A., Burstein, E., Borrego-Alvarez, A., Chong, J., Wong, E., Yavorska, T., Naranian, T., Chi, M., Wang, Y., Bentov, Y., Alexis, J., Meriano, J., Sung, H. K., Gasser, D. L., Moley, K. H., Hekimi, S., Casper, R. F., & Jurisicova, A. (2015). Coenzyme Q10 restores oocyte mitochondrial function and fertility during reproductive aging. Aging cell, 14(5), 887–895. [CrossRef]

- Bezdíček, J., Sekaninová, J., Janků, M., Makarevič, A., Luhová, L., Dujíčková, L., & Petřivalský, M. (2025). Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species: multifaceted regulators of ovarian activity†. Biology of reproduction, 112(5), 789–806. [CrossRef]

- Bochynska, S., García-Pérez, M. Á., Tarín, J. J., Szeliga, A., Meczekalski, B., & Cano, A. (2025). The Final Phases of Ovarian Aging: A Tale of Diverging Functional Trajectories. Journal of clinical medicine, 14(16), 5834. [CrossRef]

- Boldyrev, A. A., Aldini, G., & Derave, W. (2013). Physiology and pathophysiology of carnosine. Physiological reviews, 93(4), 1803–1845. [CrossRef]

- Bönhof, G. J., Sipola, G., Strom, A., Herder, C., Strassburger, K., Knebel, B., Reule, C., Wollmann, J. C., Icks, A., Al-Hasani, H., Roden, M., Kuss, O., & Ziegler, D. (2022). BOND study: a randomised double-blind, placebo-controlled trial over 12 months to assess the effects of benfotiamine on morphometric, neurophysiological and clinical measures in patients with type 2 diabetes with symptomatic polyneuropathy. BMJ open, 12(2), e057142. [CrossRef]

- Bourebaba, N., Sikora, M., Qasem, B., Bourebaba, L., & Marycz, K. (2023). Sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) mitigates ER stress and improves viability and insulin sensitivity in adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ASC) of equine metabolic syndrome (EMS)-affected horses. Cell communication and signaling : CCS, 21(1), 230. [CrossRef]

- Bozic, I., & Lavrnja, I. (2023). Thiamine and benfotiamine: Focus on their therapeutic potential. Heliyon, 9(11), e21839. [CrossRef]

- Brigelius-Flohé, R., & Flohé, L. (2020). Regulatory phenomena in the glutathione peroxidase superfamily. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling, *33*(7), 498–516. [CrossRef]

- Brinton, R. D., Yao, J., Yin, F., Mack, W. J., & Cadenas, E. (2015). Perimenopause as a neurological transition state. Nature reviews. Endocrinology, 11(7), 393–405. [CrossRef]

- Broekmans, F. J., Soules, M. R., & Fauser, B. C. (2009). Ovarian aging: mechanisms and clinical consequences. Endocrine reviews, 30(5), 465–493. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, G., Morgan, B., & Riemer, J. (2017). Mitochondrial Glutathione: Regulation and Functions. Antioxidants & redox signaling, 27(15), 1162–1177. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Yang, J., & Zhang, L. (2023). The Impact of Follicular Fluid Oxidative Stress Levels on the Outcomes of Assisted Reproductive Therapy. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland), 12(12), 2117. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Zhang, J., Tian, Y., Xu, X., Wang, B., Huang, Z., Lou, S., Kang, J., Zhang, N., Weng, J., Liang, Y., & Ma, W. (2024). Iron accumulation in ovarian microenvironment damages the local redox balance and oocyte quality in aging mice. Redox biology, 73, 103195. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B., Shi, Y., Wu, Q., Wang, Y., & Ma, Y. (2023). Selenium Protects Follicular Granulosa Cells from Apoptosis Induced by Mercury Through Inhibition of ATF6/CHOP Pathway in Laying Hens. Biological trace element research, 201(11), 5368–5378. [CrossRef]

- Cheraghi, E., Mehranjani, M. S., Shariatzadeh, M. A., Esfahani, M. H., & Ebrahimi, Z. (2016). N-Acetylcysteine improves oocyte and embryo quality in polycystic ovary syndrome patients undergoing intracytoplasmic sperm injection: an alternative to metformin. Reproduction, fertility, and development, 28(6), 723–731. [CrossRef]

- Cicek, N., Eryilmaz, O. G., Sarikaya, E., Gulerman, C., & Genc, Y. (2012). Vitamin E effect on controlled ovarian stimulation of unexplained infertile women. Journal of assisted reproduction and genetics, 29(4), 325–328. [CrossRef]

- Colella, M., Cuomo, D., Peluso, T., Falanga, I., Mallardo, M., De Felice, M., & Ambrosino, C. (2021). Ovarian Aging: Role of Pituitary-Ovarian Axis Hormones and ncRNAs in Regulating Ovarian Mitochondrial Activity. Frontiers in endocrinology, 12, 791071. [CrossRef]

- Cosme, P., Rodríguez, A. B., Garrido, M., & Espino, J. (2022). Coping with Oxidative Stress in Reproductive Pathophysiology and Assisted Reproduction: Melatonin as an Emerging Therapeutical Tool. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland), 12(1), 86. [CrossRef]

- Demay, M. B., Pittas, A. G., Bikle, D. D., Diab, D. L., Kiely, M. E., Lazaretti-Castro, M., Lips, P., Mitchell, D. M., Murad, M. H., Powers, S., Rao, S. D., Scragg, R., Tayek, J. A., Valent, A. M., Walsh, J. M. E., & McCartney, C. R. (2024). Vitamin D for the prevention of disease: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

- Derakhshan, Z., Bahmanpour, S., Nasr-Esfahani, M. H., Masjedi, F., Mirani, M., Dara, M., & Tabei, S. M. B. (2024). Alpha-Lipoic Acid Ameliorates Impaired Steroidogenesis in Human Granulosa Cells Induced by Advanced Glycation End-Products. Iranian journal of medical sciences, 49(8), 515–527. [CrossRef]

- Diamanti-Kandarakis, E., Piperi, C., Patsouris, E., Korkolopoulou, P., Panidis, D., Pawelczyk, L., Papavassiliou, A. G., & Duleba, A. J. (2007). Immunohistochemical localization of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) and their receptor (RAGE) in polycystic and normal ovaries. Histochemistry and cell biology, 127(6), 581–589. [CrossRef]

- Diamanti-Kandarakis, E., Chatzigeorgiou, A., Papageorgiou, E., Koundouras, D., & Koutsilieris, M. (2016). Advanced glycation end-products and insulin signaling in granulosa cells. Experimental biology and medicine (Maywood, N.J.), 241(13), 1438–1445. [CrossRef]

- Ding, N., Wang, X., Harlow, S. D., Randolph, J. F., Jr, Gold, E. B., & Park, S. K. (2024). Heavy Metals and Trajectories of Anti-Müllerian Hormone During the Menopausal Transition. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism, 109(11), e2057–e2064. [CrossRef]

- Di Nicuolo, F., D'Ippolito, S., Castellani, R., Rossi, E. D., Masciullo, V., Specchia, M., Mariani, M., Pontecorvi, A., Scambia, G., & Di Simone, N. (2019). Effect of alpha-lipoic acid and myoinositol on endometrial inflammasome from recurrent pregnancy loss women. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology, 82(4), Article e13153. [CrossRef]

- Dong, H., Zhang, Y., Huang, Y., & Deng, H. (2022). Pathophysiology of RAGE in inflammatory diseases. Frontiers in immunology, 13, 931473. [CrossRef]

- Duncan, F. E., Que, E. L., Zhang, N., Feinberg, E. C., O'Halloran, T. V., & Woodruff, T. K. (2016). The zinc spark is an inorganic signature of human egg activation. Scientific reports, 6, 24737. [CrossRef]

- Eddie-Amadi, B. F., Ezejiofor, A. N., Orish, C. N., & Orisakwe, O. E. (2022). Zn and Se abrogate heavy metal mixture induced ovarian and thyroid oxido-inflammatory effects mediated by activation of NRF2-HMOX-1 in female albino rats. Current research in toxicology, 4, 100098. [CrossRef]

- Es-Sai, B., Wahnou, H., Benayad, S., Rabbaa, S., Laaziouez, Y., El Kebbaj, R., Limami, Y., & Duval, R. E. (2025). Gamma-Tocopherol: A Comprehensive Review of Its Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Anticancer Properties. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 30(3), 653. [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K., Shindo, Y., Katsuta, Y., Goto, M., Hotta, K., & Oka, K. (2023). Intracellular Mg2+ protects mitochondria from oxidative stress in human keratinocytes. Communications biology, 6(1), 868. [CrossRef]

- Gantt, S. L., Denisov, I. G., Grinkova, Y. V., & Sligar, S. G. (2009). The critical iron-oxygen intermediate in human aromatase. Biochemical and biophysical research communications, 387(1), 169–173. [CrossRef]

- Garg, D., & Merhi, Z. (2016). Relationship between Advanced Glycation End Products and Steroidogenesis in PCOS. Reproductive biology and endocrinology : RB&E, 14(1), 71. [CrossRef]

- Garner, T. B., Hester, J. M., Carothers, A., & Diaz, F. J. (2021). Role of zinc in female reproduction. Biology of Reproduction, 104(5), 976–994. [CrossRef]

- Gholami, M., Samaei, S. E., Shaki, F., Etemadinezhad, S., & Sayyad, M. S. (2025). Evaluation of the protective effect of Benfotiamine against neurotoxic effects, depression and oxidative stress induced by noise exposure. Scientific reports, 15(1), 31336. [CrossRef]

- Guarano, A., Capozzi, A., Cristodoro, M., Di Simone, N., & Lello, S. (2023). Alpha Lipoic Acid Efficacy in PCOS Treatment: What Is the Truth?. Nutrients, 15(14), 3209. [CrossRef]

- Gyengesi, E., Paxinos, G., & Andrews, Z. B. (2012). Oxidative stress in the hypothalamus: the importance of calcium signaling and mitochondrial ROS in body weight regulation. Current Neuropharmacology, 10(4), 344 - 353. [CrossRef]

- Hall J. E. (2007). Neuroendocrine changes with reproductive aging in women. Seminars in reproductive medicine, 25(5), 344–351. [CrossRef]

- Hirano, M., Onodera, T., Takasaki, K., Takahashi, Y., Ichinose, T., Nishida, H., Hiraike, H., & Nagasaka, K. (2025). Ovarian aging: pathophysiology and recent developments in maintaining ovarian reserve. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 16, 1619516. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J., Wang, H., Fang, J., Jiang, R., Kong, Y., Zhang, T., Yang, G., Jin, H., Shi, S., Song, N., Qi, L., Huang, X., Wu, Z., & Yao, G. (2025). Ovarian aging-associated downregulation of GPX4 expression regulates ovarian follicular development by affecting granulosa cell functions and oocyte quality. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, 39(6), e70469. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., Hu, C., Ye, H., Luo, R., Fu, X., Li, X., Huang, J., Chen, W., & Zheng, Y. (2019). Inflamm-Aging: A New Mechanism Affecting Premature Ovarian Insufficiency. Journal of immunology research, 2019, 8069898. [CrossRef]

- Hummitzsch, K., Kelly, J. E., Hatzirodos, N., Bonner, W. M., Tang, F., Harris, H. H., & Rodgers, R. J. (2024). Expression levels of the selenium-uptake receptor LRP8, the antioxidant selenoprotein GPX1 and steroidogenic enzymes correlate in granulosa cells. Reproduction & fertility, 5(3), e230074. [CrossRef]

- Ji, T., Chen, X., Zhang, Y., Fu, K., Zou, Y., Wang, W., & Zhao, J. (2022). Effects of N-Acetylcysteine on the Proliferation, Hormone Secretion Level, and Gene Expression Profiles of Goat Ovarian Granulosa Cells. Genes, 13(12), 2306. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y., Han, Y., Qiao, P., & Ren, F. (2025). Exploring the protective effects of coenzyme Q10 on female fertility. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology, 13, 1633166. [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K., Baros, S., & Valko, M. (2012). Redox active metal-induced oxidative stress in biological systems. Transition Metal Chemistry, 37, 127–134. [CrossRef]

- Ju, W., Zhao, Y., Yu, Y., Zhao, S., Xiang, S., & Lian, F. (2024). Mechanisms of mitochondrial dysfunction in ovarian aging and potential interventions. Frontiers in endocrinology, 15, 1361289. [CrossRef]

- Ju, W., Yan, B., Li, D., Lian, F., & Xiang, S. (2025). Mitochondria-driven inflammation: a new frontier in ovarian ageing. Journal of translational medicine, 23(1), 1005. [CrossRef]

- Kandaraki, E. A., Chatzigeorgiou, A., Papageorgiou, E., Piperi, C., Adamopoulos, C., Papavassiliou, A. G., Koutsilieris, M., & Diamanti-Kandarakis, E. (2018). Advanced glycation end products interfere in luteinizing hormone and follicle stimulating hormone signaling in human granulosa KGN cells. Experimental biology and medicine (Maywood, N.J.), 243(1), 29–33. [CrossRef]

- Kapper, C., Oppelt, P., Ganhör, C., Gyunesh, A. A., Arbeithuber, B., Stelzl, P., & Rezk-Füreder, M. (2024). Minerals and the Menstrual Cycle: Impacts on Ovulation and Endometrial Health. Nutrients, 16(7), 1008. [CrossRef]

- Klein, N. A., & Soules, M. R. (1998). Endocrine changes of the perimenopause. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology, 41(4), 912–920. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, N., Machida, T., Takahashi, T., Takatsu, H., Shinkai, T., Abe, K., & Urano, S. (2009). Elevation by oxidative stress and aging of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal activity in rats and its prevention by vitamin e. Journal of clinical biochemistry and nutrition, 45(2), 207–213. [CrossRef]

- Kong, B. Y., Bernhardt, M. L., Kim, A. M., O'Halloran, T. V., & Woodruff, T. K. (2012). Zinc maintains prophase I arrest in mouse oocytes through regulation of the MOS-MAPK pathway. Biology of reproduction, 87(1), 11–12. [CrossRef]

- Korytowski, W., Pilat, A., Schmitt, J. C., & Girotti, A. W. (2013). Deleterious cholesterol hydroperoxide trafficking in steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein-expressing MA-10 Leydig cells: implications for oxidative stress-impaired steroidogenesis. The Journal of biological chemistry, 288(16), 11509–11519. [CrossRef]

- Kornicka-Garbowska, K., Bourebaba, L., Röcken, M., & Marycz, K. (2021). Sex Hormone Binding Globulin (SHBG) Mitigates ER Stress in Hepatocytes In Vitro and Ex Vivo. Cells, 10(4), 755. [CrossRef]

- Krsmanović, L. Z., Stojilković, S. S., Merelli, F., Dufour, S. M., Virmani, M. A., & Catt, K. J. (1992). Calcium signaling and episodic secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone in hypothalamic neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 89(18), 8462–8466. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P., Liu, C., Hsu, J. W., Chacko, S., Minard, C., Jahoor, F., & Sekhar, R. V. (2021). Glycine and N-acetylcysteine (GlyNAC) supplementation in older adults improves glutathione deficiency, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammation, insulin resistance, endothelial dysfunction, genotoxicity, muscle strength, and cognition: Results of a pilot clinical trial. Clinical and translational medicine, 11(3), e372. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P., Liu, C., Suliburk, J., Hsu, J. W., Muthupillai, R., Jahoor, F., Minard, C. G., Taffet, G. E., & Sekhar, R. V. (2023). Supplementing Glycine and N-Acetylcysteine (GlyNAC) in Older Adults Improves Glutathione Deficiency, Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Inflammation, Physical Function, and Aging Hallmarks: A Randomized Clinical Trial. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences, 78(1), 75–89. [CrossRef]

- Kushnir, V. A., Ludaway, T., Russ, R. B., Fields, E. J., Koczor, C., & Lewis, W. (2012). Reproductive aging is associated with decreased mitochondrial abundance and altered structure in murine oocytes. Journal of assisted reproduction and genetics, 29(7), 637–642. [CrossRef]

- Lafuente A. (2013). The hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis is target of cadmium toxicity. An update of recent studies and potential therapeutic approaches. Food and chemical toxicology : an international journal published for the British Industrial Biological Research Association, 59, 395–404. [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.-L., Xiong, W.-J., Li, L.-S., Lan, M.-F., Zhang, J.-X., Zhou, Y.-T., Niu, D., & Duan, X. (2023). Zinc deficiency compromises the maturational competence of porcine oocyte by inducing mitophagy and apoptosis. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 252, Article 114593. [CrossRef]

- Lava Kumar, S., Kushawaha, B., Mohanty, A., Kumari, A., Kumar, A., Beniwal, R., Kiran Kumar, P., Athar, M., Krishna Rao, D., & Rao, H. B. D. P. (2024). Glutathione peroxidase (GPX1) - Selenocysteine metabolism preserves the follicular fluid's (FF) redox homeostasis via IGF-1- NMD cascade in follicular ovarian cysts (FOCs). Biochimica et biophysica acta. Molecular basis of disease, 1870(6), 167235. [CrossRef]

- Li, C. J., Lin, L. T., Tsai, H. W., Chern, C. U., Wen, Z. H., Wang, P. H., & Tsui, K. H. (2021). The Molecular Regulation in the Pathophysiology in Ovarian Aging. Aging and disease, 12(3), 934–949. [CrossRef]

- Li, M., Hu, S., Sun, J., & Zhang, Y. (2024). The role of vitamin D3 in follicle development. Journal of ovarian research, 17(1), 148. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Zhao, T., Li, J., Xia, M., Li, Y., Wang, X., Liu, C., Zheng, T., Chen, R., Kan, D., Xie, Y., Song, J., Feng, Y., Yu, T., & Sun, P. (2022). Oxidative Stress and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE): Implications in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Aging-related Diseases. Journal of immunology research, 2022, 2233906. [CrossRef]

- Liew, S. H., Nguyen, Q. N., Strasser, A., Findlay, J. K., & Hutt, K. J. (2017). The ovarian reserve is depleted during puberty in a hormonally driven process dependent on the pro-apoptotic protein BMF. Cell death & disease, 8(8), e2971. [CrossRef]

- Lim, J., & Luderer, U. (2011). Oxidative damage increases and antioxidant gene expression decreases with aging in the mouse ovary. Biology of reproduction, 84(4), 775–782. [CrossRef]

- Lin, G., Li, X., Jin Yie, S. L., & Xu, L. (2024). Clinical evidence of coenzyme Q10 pretreatment for women with diminished ovarian reserve undergoing IVF/ICSI: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of medicine, 56(1), 2389469. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., Jia, Y., Meng, S., Luo, Y., Yang, Q., & Pan, Z. (2023). Mechanisms of and Potential Medications for Oxidative Stress in Ovarian Granulosa Cells: A Review. International journal of molecular sciences, 24(11), 9205. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W. J., Li, L. S., Lan, M. F., Shang, J. Z., Zhang, J. X., Xiong, W. J., Lai, X. L., & Duan, X. (2024). Zinc deficiency deteriorates ovarian follicle development and function by inhibiting mitochondrial function. Journal of ovarian research, 17(1), 115. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Cheng, G., Li, H., & Meng, Q. (2025). Serum copper to zinc ratio and risk of endometriosis: Insights from a case-control study in infertile patients. Reproductive medicine and biology, 24(1), e12644. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Lin, X., Zhang, S., Guo, C., Li, J., Mi, Y., & Zhang, C. (2018). Lycopene ameliorates oxidative stress in the aging chicken ovary via activation of Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. Aging, 10(8), 2016–2036. [CrossRef]

- Lizcano F. (2022). Roles of estrogens, estrogen-like compounds, and endocrine disruptors in adipocytes. Frontiers in endocrinology, 13, 921504. [CrossRef]

- Lord, T., Martin, J. H., & Aitken, R. J. (2015). Accumulation of electrophilic aldehydes during postovulatory aging of mouse oocytes causes reduced fertility, oxidative stress, and apoptosis. Biology of reproduction, 92(2), 33. [CrossRef]

- Lord, T. (2025). The role of reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress in post-ovulatory ageing and apoptosis of the mammalian oocyte [Doctoral dissertation, University of Newcastle]. Open Research Newcastle. https://hdl.handle.net/1959.13/1310421.

- Lou, Y., Yang, T., Xia, C., Yang, S., Deng, H., Zhu, Y., Fang, J., Zuo, Z., & Guo, H. (2025). Effects of Copper on Steroid Hormone Secretion, Steroidogenic Enzyme Expression, and Transcriptomic Profiles in Yak Ovarian Granulosa Cells. Veterinary sciences, 12(5), 428. [CrossRef]

- Lu, C., He, J. C., Cai, W., Liu, H., Zhu, L., & Vlassara, H. (2004). Advanced glycation endproduct (AGE) receptor 1 is a negative regulator of the inflammatory response to AGE in mesangial cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101(32), 11767–11772. [CrossRef]

- Luddi, A., Capaldo, A., Focarelli, R., Gori, M., Morgante, G., Piomboni, P., & De Leo, V. (2016). Antioxidants reduce oxidative stress in follicular fluid of aged women undergoing IVF. Reproductive biology and endocrinology : RB&E, 14(1), 57. [CrossRef]

- Mahsa Poormoosavi, S., Behmanesh, M. A., Varzi, H. N., Mansouri, S., & Janati, S. (2021). The effect of follicular fluid selenium concentration on oocyte maturation in women with polycystic ovary syndrome undergoing in vitro fertilization/Intracytoplasmic sperm injection: A cross-sectional study. International journal of reproductive biomedicine, 19(8), 689–698. [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Cárceles, A. B., Souter, I., Li, M. C., Mitsunami, M., Dimitriadis, I., Ford, J. B., Mínguez-Alarcón, L., Chavarro, J. E., & EARTH Study Team (2025). Antioxidant Intake and Ovarian Reserve in Women Attending a Fertility Center. Nutrients, 17(3), 554. [CrossRef]

- Mashhadi, F., Sedghi, Z., Hemmat, A., Rivaz, R., & Roudi, F. (2025). Nutritional interventions for enhancing female fertility: A comprehensive review of micronutrients and their impact. Nursing Research and Practice, 2137328. [CrossRef]